Abstract

Background

Coronary artery aneurysms after drug eluting stents are rare. We present a case series of type II coronary aneurysms after implantation of Everolimus eluting stents including patients developing giant aneurysms with a toxic course.

Case presentation

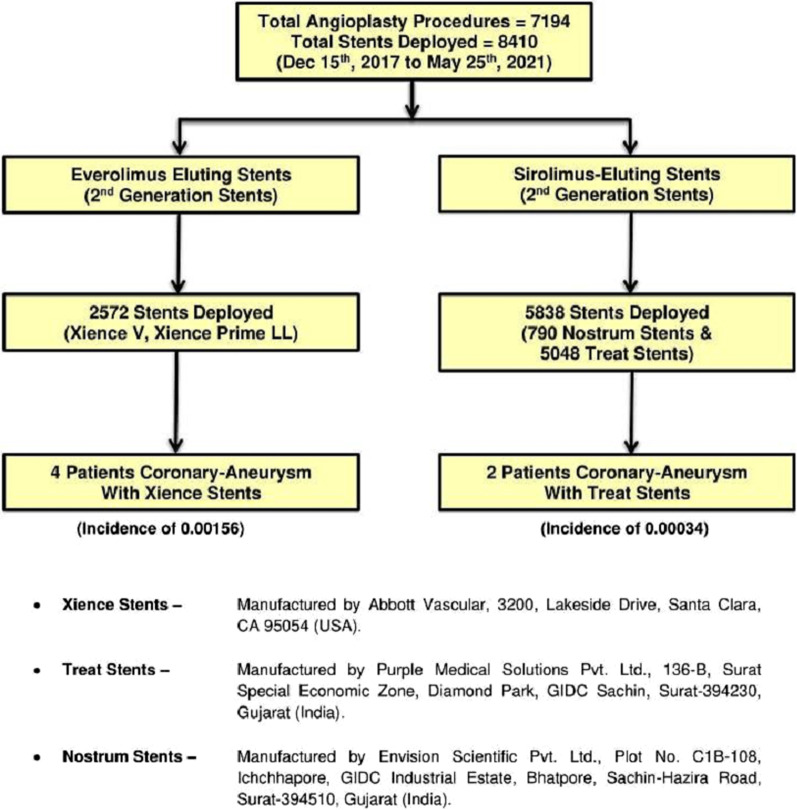

Over a span of 3.5 years at our center 2572 patients were implanted Everolimus eluting stents out of which 4 patients developed coronary type II aneurysms an incidence of 0.00156 whereas 5838 patients were implanted Sirolimus eluting 2nd generation stents out of which 2 patients developed similar aneurysms with an incidence of 0.00034. The slight increase in incidence in Everolimus stents does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.054) and is limited by single centre non randomized study. We also propose a hypothesis that the slight increase in the incidence maybe due to allergy to Methacrylate present in Everolimus eluting Xience stent’s primer which is absent in other Sirolimus eluting stents used at our center but that needs to be further investigated. We also found some patients who developed giant aneurysms including Left main aneurysms. In our series operative repair of these patients had better outcomes than covered stent deployment but larger trials maybe needed to confirm the same.

Conclusions

Coronary artery aneurysms after stent implantation are rare but occasionally giant aneurysms are formed with a toxic course. The incidence and morphology of aneurysms after Everolimus and Sirolimus eluting stent deployment do not differ much.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12872-022-02503-1.

Keywords: Coronary artery aneurysm, Xience stent, Methacrylate, Giant aneurysm, Left main aneurysm, Case report, Case series

Background

Coronary artery aneurysms are rare, found in 0.3 to 4.9% of patients undergoing coronary angiography. While Kawasaki disease is the most common cause of coronary aneurysm in children, atherosclerosis is the cause in > 90% of adults [1]. The incidence of coronary artery aneurysm after drug eluting stent (DES) deployment varies between 0.2–2.3% and is similar to bare-metal stent (BMS) [2]. Cases have been reported to occur after 3 days to 4 years post percutaneous intervention (PCI). Here we present a case series of coronary aneurysms related to Everolimus eluting second generation stents and compare it with Sirolimus eluting second generation stents at our centre.

Case presentation

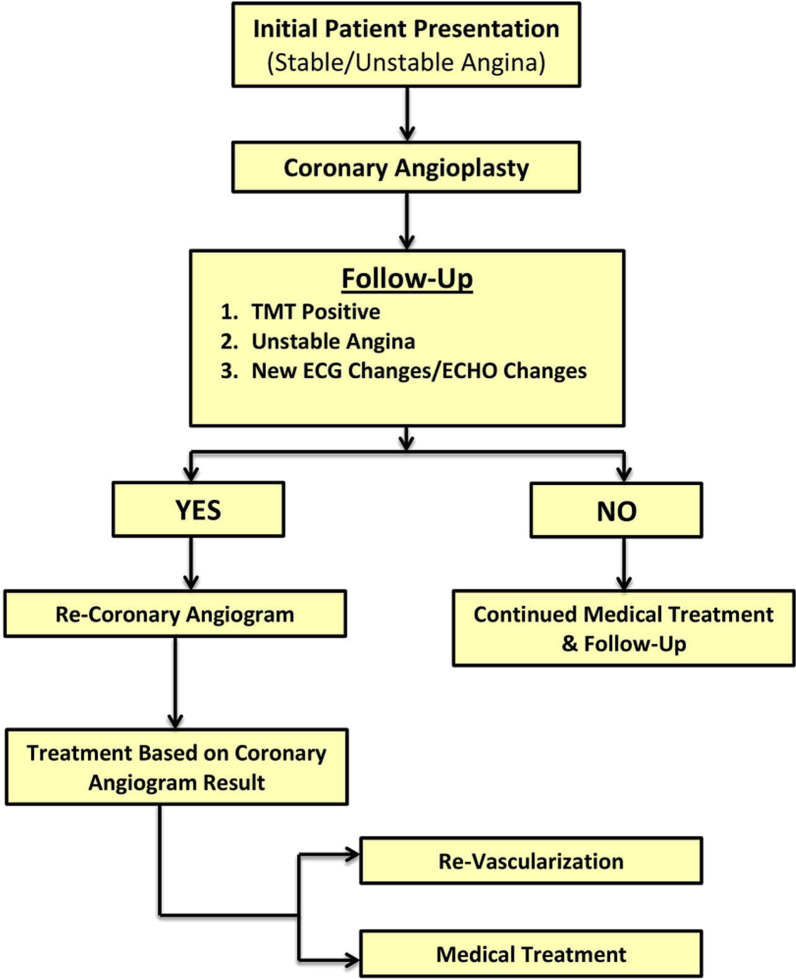

Initial scheme of treatment at our centre

See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of sequence of events at our center

Case series of aneurysms after Everolimus eluting 2nd generation stents

Case 1—patient A

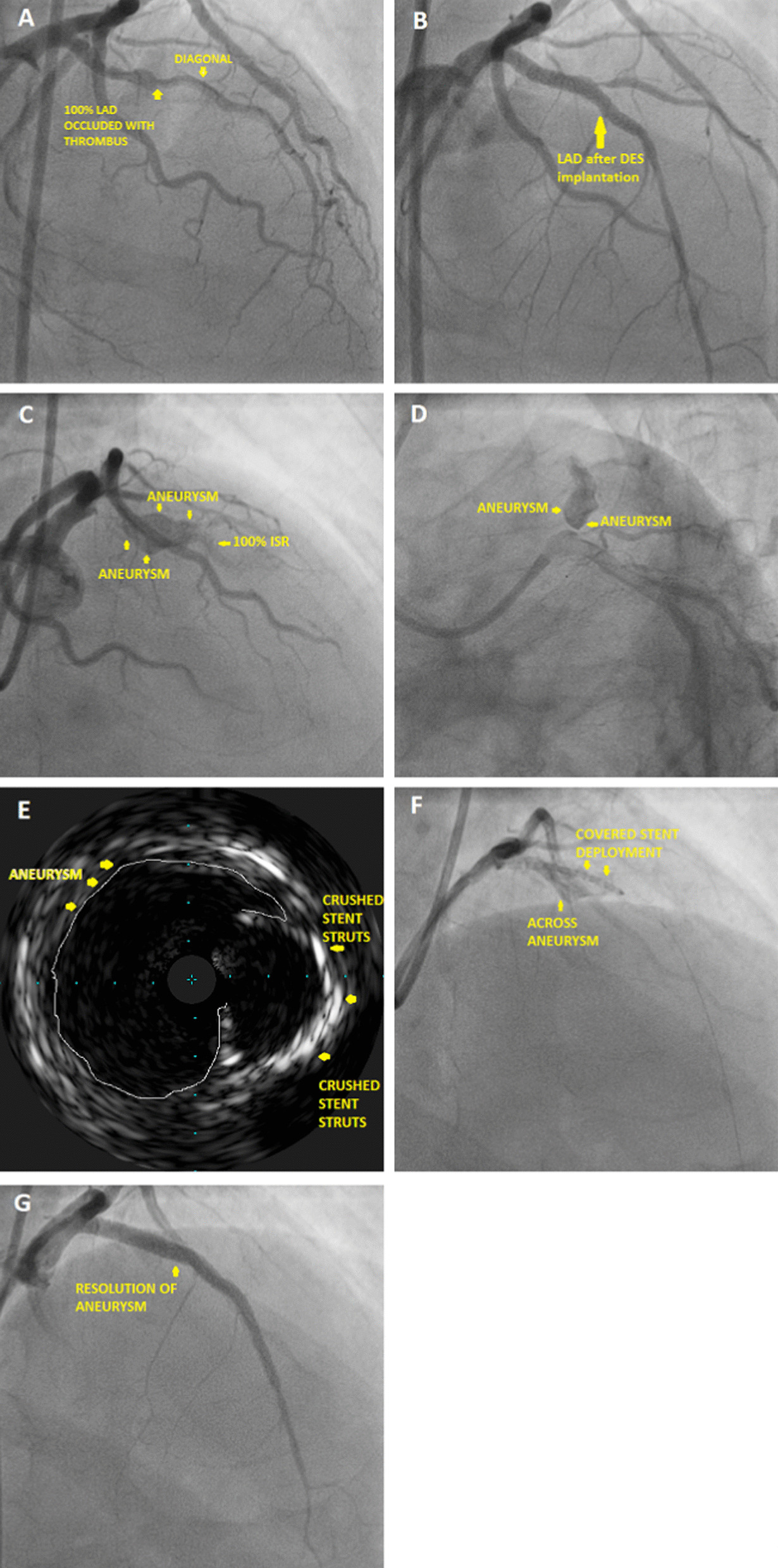

A 68 year hypertensive male presented with an anterior wall myocardial infarction and was lysed with Streptokinase on Oct 9th, 20. Coronary angiogram (CAG) done (Fig. 2A) showed mid left anterior descending (LAD) artery 100% occluded with thrombus. Subsequently PCI to mid LAD was done using Xience V-2.75 × 28 mm DES (Fig. 2B). The lesion was post dilated with a 3 mm balloon at 15 atm. Subsequently patient presented to us again after 5 months with unstable angina. There was no history of fever during the interim period and total leukocyte count (TLC) on admission was 6600/µL. Echocardiogram (Echo) showed left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of 30%. CAG with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) was done which showed a large aneurysm in mid LAD (Additional file 1: Video S1, Additional file 2: Video S2, Additional file 3: Video S3) with complete in stent occlusion (Fig. 2C–E). PCI was done with a covered stent 3.5 × 26 mm (Graft master) to ostio-proximal LAD and from proximal to mid LAD with 2.75 × 23 mm Xience V DES (Fig. 2F, G). Subsequently the patient expired after 1.5 months due to diarrhea and sepsis complicating heart failure at an outside hospital.

Fig. 2.

A Coronary angiogram showing mid LAD 100% occluded with thrombus, B post stenting of LAD with DES, C angiogram showing aneurysm in LAD with 100% ISR distally, D angiogram showing coronary aneurysm in LAD, E intravascular ultrasound showing crushed stent struts with adjoining aneurysm, F covered stent deployment across the aneurysm, G after covered stent deployment resolution of aneurysm

Case 2—patient B

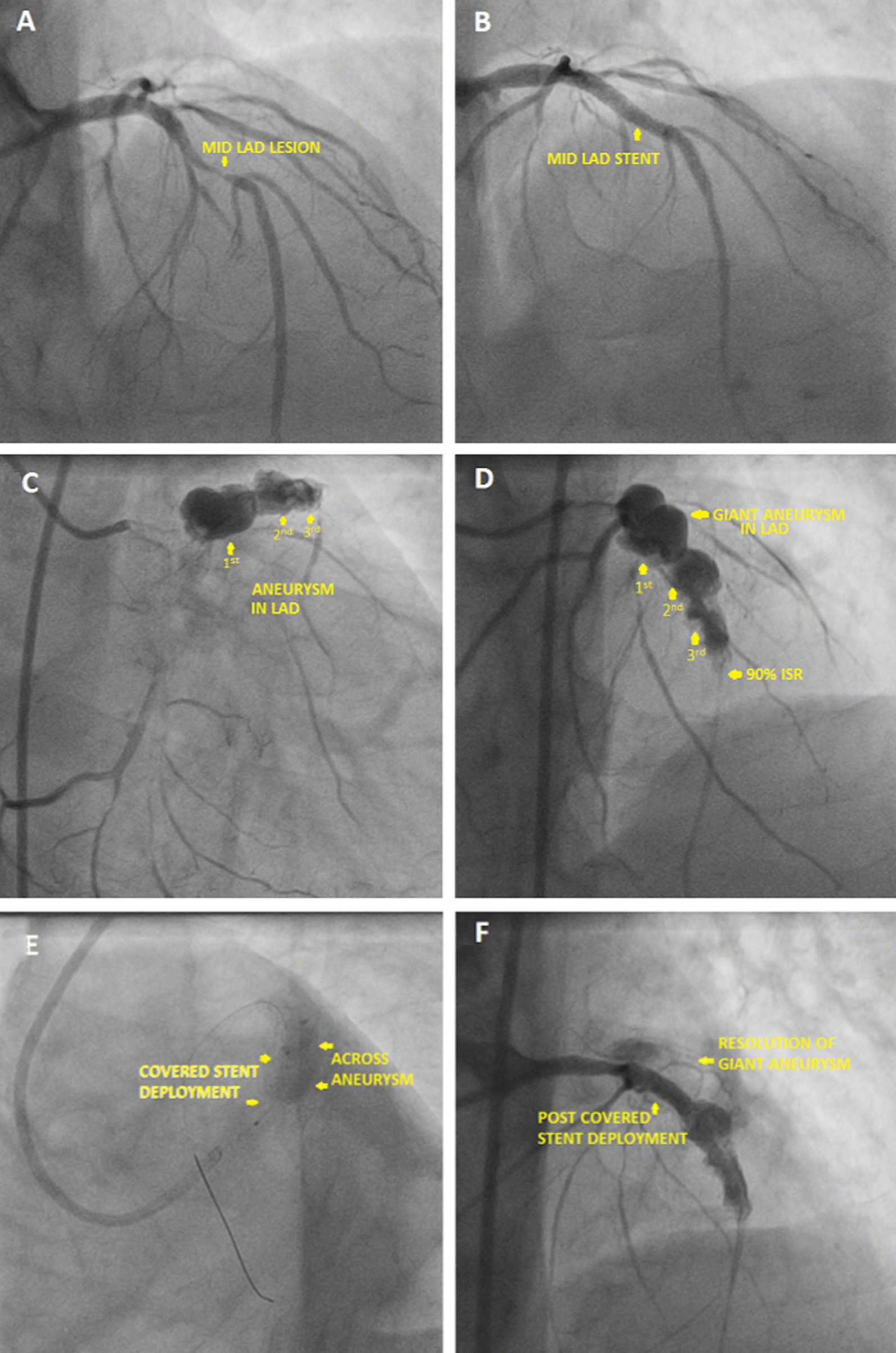

69 year male with diabetes and hypertension presented with chest pain outside where CAG was done (Fig. 3A) which showed mid LAD 90–95% stenosis, and non-critical lesions in other vessels. Echo showed LVEF 35–40%. Proximal LAD was stented with 2.75 × 33 mm Xience Prime LL deployed at 12 atm (Fig. 3B). Post dilatation was done with 3 × 12 mm NC Traveler balloon at 13 atm. Subsequently the patient presented after 3.5 months with recurrent angina. Echo showed LVEF 35% and TLC was 7900/µL. Repeat CAG showed complete occlusion of LAD stent and three large aneurysms including one giant aneurysm adjacent to the entire length of the stent segment (Fig. 3C, D, Additional file 4: Video S4, Additional file 5: Video S5). So using a covered stent 3.5 × 19 mm (Graft master) the giant aneurysm was approximately safely (Fig. 3E, F) and the patient was scheduled for a staged PCI. Subsequently the patient was lost to follow up and expired after 10 days due to heart failure at an outside hospital.

Fig. 3.

A Coronary angiogram showing lesion in mid LAD, B post stenting in mid LAD, C angiogram showing coronary aneurysm, D angiogram showing giant aneurysm in proximal LAD along-with two other saccular aneurysms in LAD, E covered stent deployment across the giant aneurysm, F post covered stent deployment resolution of giant aneurysm

Case 3—patient C

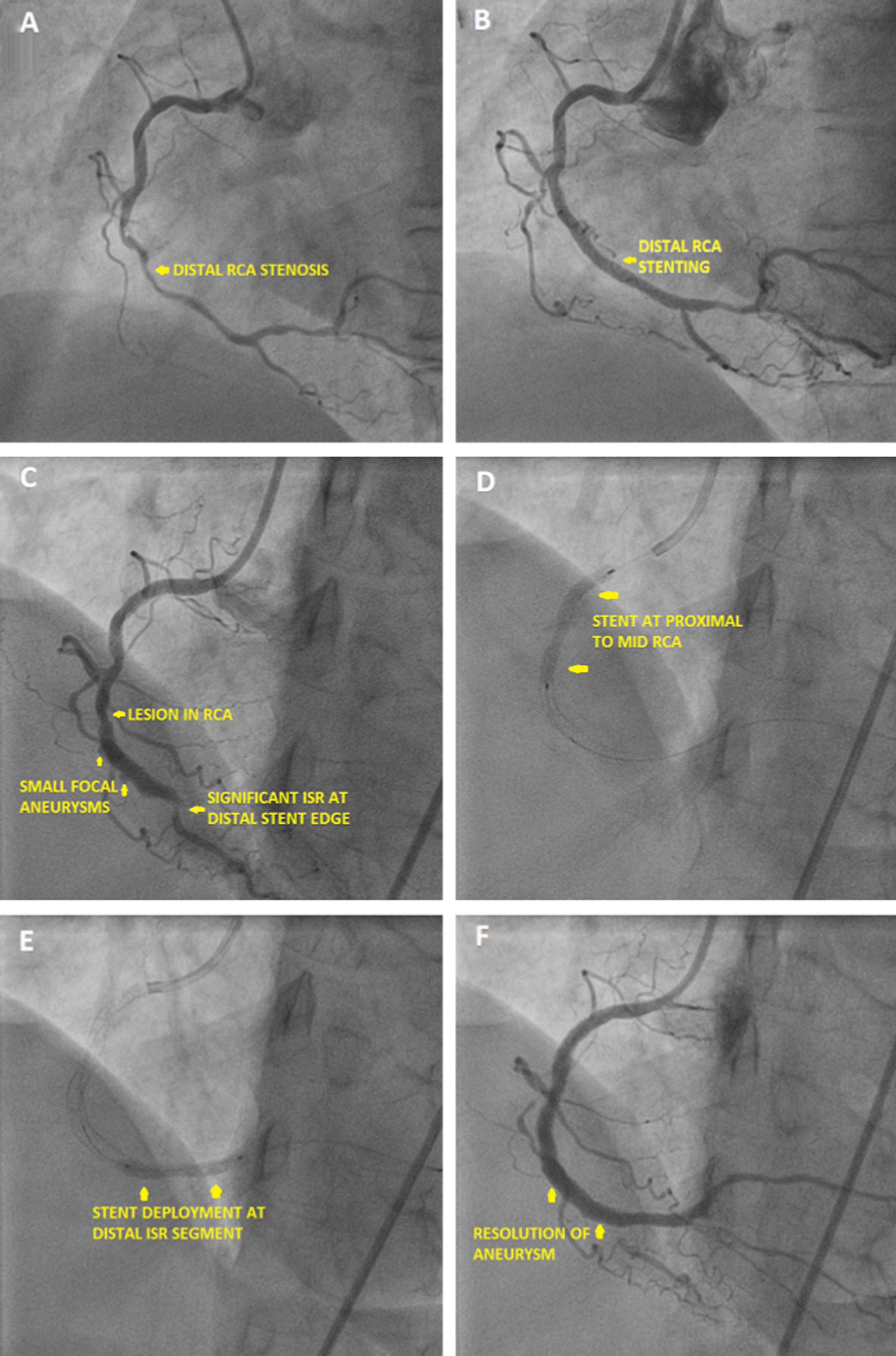

71 year hypertensive female presented to our hospital with unstable angina. CAG (Fig. 4A) showed 70–80% lesion in mid and distal RCA. PCI to mid to distal RCA was done using 2.5 × 38 mm Xience Prime DES (Fig. 4B). The lesion was post dilated using 2.75 × 12 mm NC balloon. Patient was re admitted after 3 months with unstable angina and TLC of 9700/µL. Re-CAG showed proximal RCA 70–80% lesion. The stented segment had multiple small aneurysms seen (Fig. 4C, Additional file 6: Video S6). Distal end of stent had around 98% ISR noted. The RCA proximal lesion was stented with 2.75 × 33 mm Xience Prime DES deployed at 10 atm (Fig. 4D). The distal RCA lesion including the ISR segment was stented with 2.75 × 23 mm Xience V (DES) deployed at 10 atm (Fig. 4E). Post dilatation was done with 3.5 × 12 mm NC Traveler balloon at 15 atm. The final angiogram showed complete resolution of the aneurysms (Fig. 4F). Patient is currently asymptomatic.

Fig. 4.

A Coronary angiogram showing lesion in distal RCA, B coronary angiogram image post stenting in distal RCA, C coronary angiogram showing small aneurysms across the stented segment with distal significant ISR and another lesion in proximal RCA, D coronary angiogram showing stent deployment in proximal right coronary artery), E coronary angiogram showing stent deployment near previous distal ISR, F coronary angiogram showing final result with complete resolution of aneurysm

Case 4—patient D

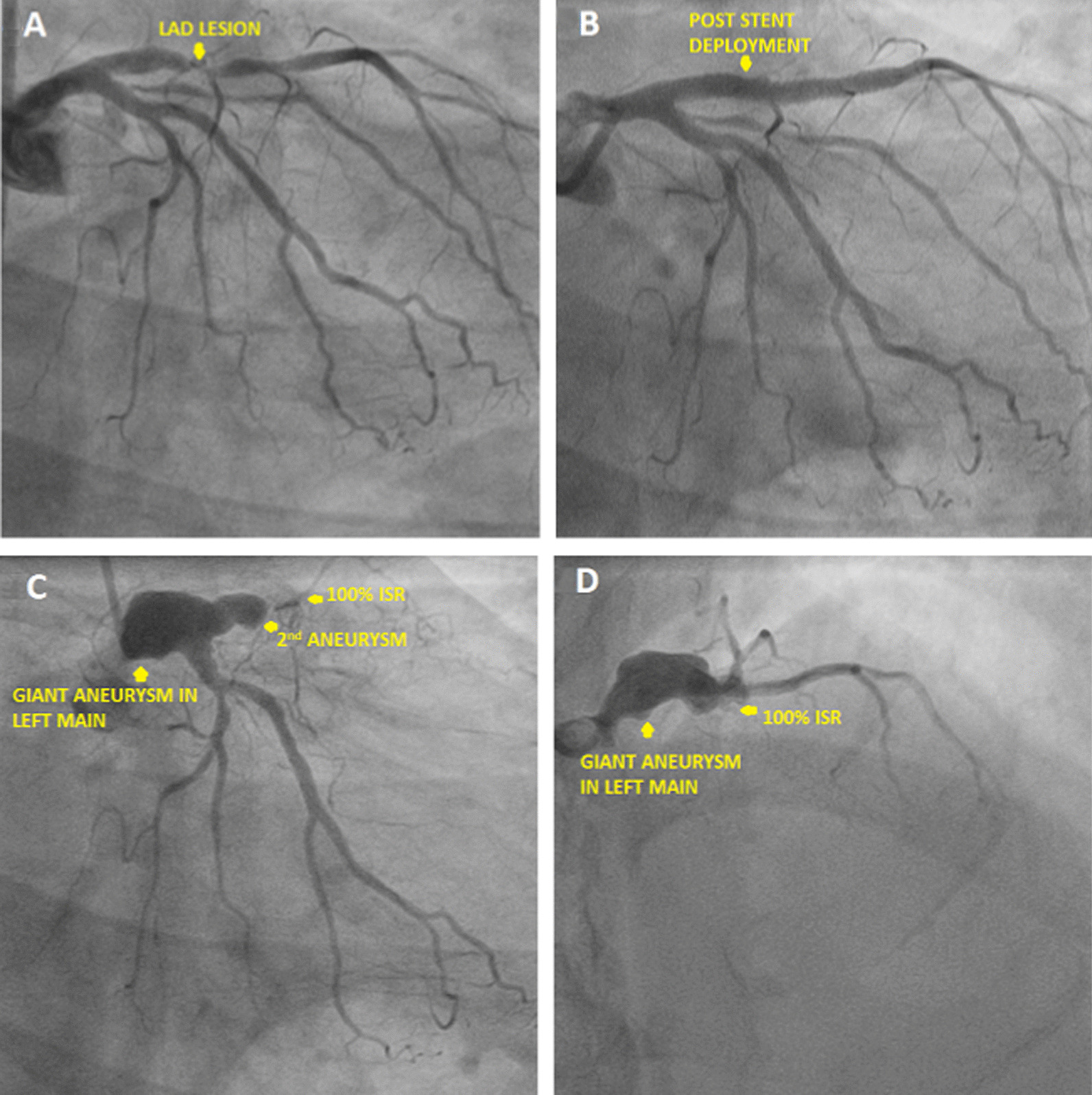

54 year diabetic hypertensive male presented to us with unstable angina. CAG done on Oct 9th, 20 showed proximal LAD 99% plaque (Fig. 5A). PCI to LAD was done using 3 × 28 mm Xience V drug eluting stent (Fig. 5B). The lesion was post dilated with 3.5 × 12 mm NC balloon at 15 atm. Patient was re admitted after 8 months with chest pain, LVEF 35% and TLC 8200/µL. CAG repeated showed proximal end of stent in LAD 100% ISR. A giant aneurysm was seen in Left main and one in proximal LAD (Fig. 5C, D, Additional file 7: Video S7). Patient was treated successfully with operative aneurysmal repair and grafting. Intra operatively there was no pus in situ and cultures from the sac were negative. Currently patient is asymptomatic.

Fig. 5.

A Coronary angiogram image showing lesion in proximal LAD artery, B Coronary angiogram image post stenting of proximal LAD, C coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm involving left main artery and 2nd aneurysm in proximal LAD, D coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm in left main artery

Discussion and conclusions

The mechanism of stent induced aneurysm has been classified by Aoki et al. into 3 types [2]. Type I Aneurysms are formed due to injury to the arterial wall during dissections or high pressure balloon dilatations. These are more often pseudo-aneurysms. IVUS in these cases may demonstrate a contained rupture with thrombus in the aneurysmal sac with only the outer tunica adventitia. These patients present within one month of the index procedure with rapidly enlarging aneurysm and sometimes pericarditis. It is seen more in chronic total occlusions (CTO) and long diffuse lesions where there is inadvertent injury to the sub intimal space.

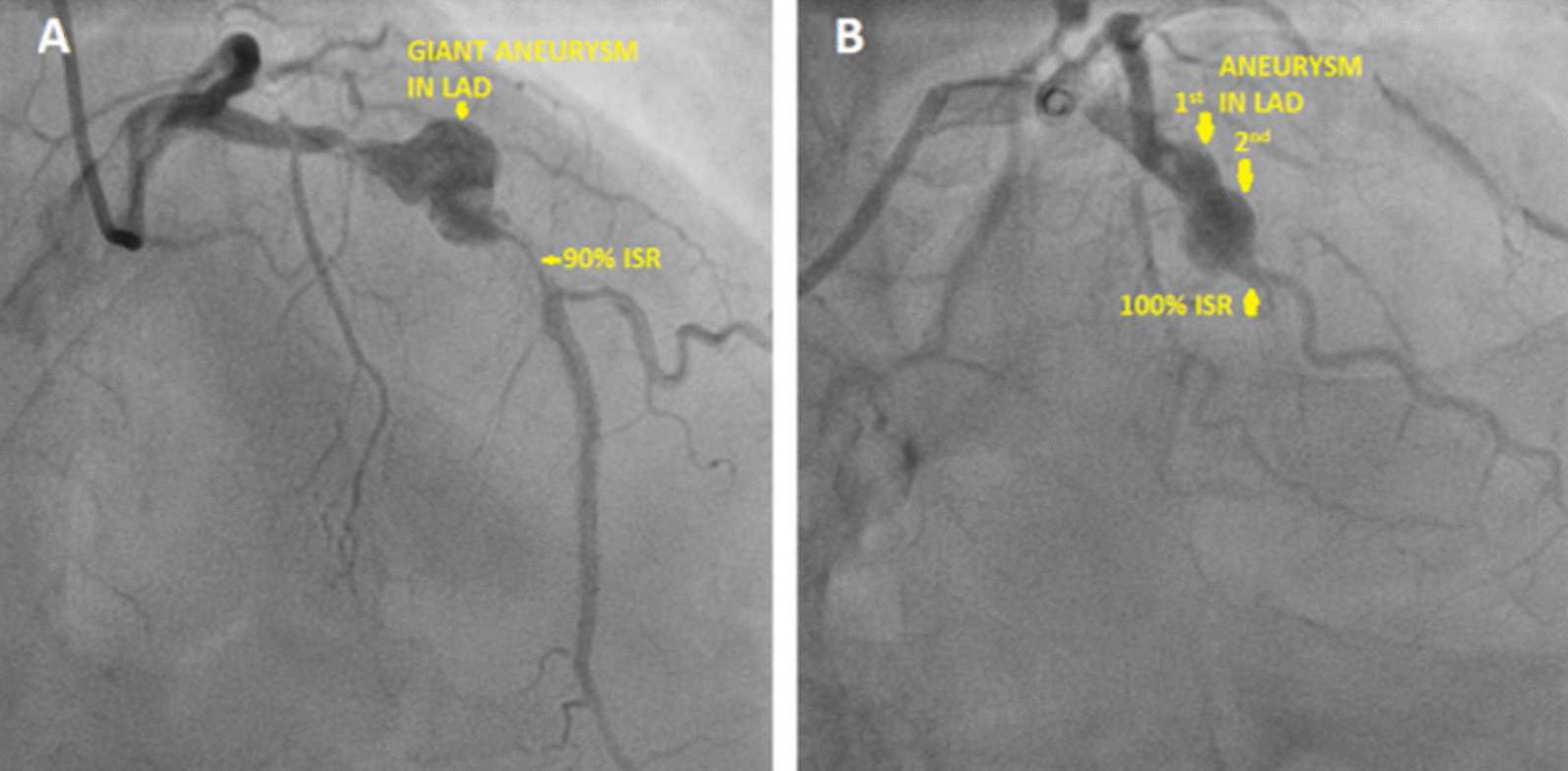

Type II stent induced aneurysms present sub acutely due to hypersensitivity reaction to either the stent metal/alloy, the drug polymer or due to the anti-proliferative action of the drug which prevents proper endothelialization. The cobalt chromium stents contain 9–11% nickel compared with stainless steel stents containing 10–14% nickel [3]. Both of them can cause allergy and ISR in patients with comparable rates (2). Here both Xience–Everolimus eluting stents and Treat-Sirolimus eluting stents were used comparably and their baseline characteristics and outcomes have been depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 7. The Xience V/Prime-LL stents used here as has a two layer coating composed of primer layer of PBMA (Poly N Butyl Methacrylate) and a drug reservoir made of poly-vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP) [3]. Fluorinated polymers are bio-compatible as they preferentially adsorb albumin to fibrinogen preventing platelet activation [3]. On the contrary the primer layer containing Methacrylate is known to cause allergic hypersensitivity [5–8]. They have been shown to induce a marked inflammatory reaction consisting primarily of eosinophils and lymphocytes. Sirolimus and Everolimus both prevent neo-intimal proliferation but also delay re endothelialization. This has been a proposing mechanism for abetting aneurysm formation. While both of them are mTORC1 inhibitors, Sirolimus is more protein bound with a longer terminal half-life. Here we also had two patients who developed stent induced aneurysm formation after implantation of 2nd generation Sirolimus eluting stents whose morphology (Fig. 6A, B) were similar to Everolimus eluting 2nd generation stents.

Table 1.

Properties of Everolimus eluting Xience stents versus Sirolimus eluting Treat stents

| Xience stent (Xience V, Xience Prime LL) [3] | Treat stent [4] | |

|---|---|---|

| Drug eluted | Everolimus eluting | Sirolimus eluting |

| Terminal half-life of drug eluted | 26–30 h | 46–72 h |

| Generation stent | 2nd generation | 2nd generation |

| Stent thickness | 81µ | 65µ |

| Stent material | L605 cobalt–chromium alloy | L605 cobalt–chromium alloy |

| Biocompatibility of stent material | Contains 9–11% nickel, chromium. Can occasionally cause metal allergy | Contains 9–11% nickel, chromium. Can occasionally cause metal allergy |

| Drug carrier/polymer | Primer layer of PBMA (Poly N Butyl Methacrylate) and a drug reservoir made of poly-vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP) | Biocompatible lactide and glycolide family of biodegradable polymer |

| Biocompatibility of drug carrier/polymer |

Primer Methacrylate known to cause hypersensitivity reaction and aneurysm formation Reservoir PVDF-HFP is bio compatible |

Biocompatible |

Fig. 7.

Total angioplasties including various stents used at our center and their incidence of aneurysm formation

Fig. 6.

A Patient E—patient with Sirolimus eluting 2nd generation stent developing aneurysm, B Patient F—patient with Sirolimus eluting 2nd generation stent developing aneurysm

Figure 7 depicts that the incidence of stent induced aneurysm formation was slightly more with Everolimus eluting Xience stents as compared to Sirolimus eluting 2nd Generation stents (Treat and Nostrum). But by using chi square analysis it does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.054).

Type III stent induced coronary aneurysm are infection related mycotic aneurysms. Patients are toxic with bacteremia and have a high blood leukocyte count. In our series none of the patients presented within 1 month of angioplasty with fever or raised TLC and most of them presented with angina. In addition patient D who had operative repair done, no pus was found in the aneurysmal sac. Hence in our series infective etiology was ruled out.

In our case series as depicted in Table 2, most patients were old (average age of 65.5 years), male (75%) and all of them were hypertensive. Possibly hypertension was associated with more arterial shear stress. The native lesions were long segment lesions with near complete occlusion predisposing to intimal injury. LAD was the most common artery involved as it is exposed to higher wall stress during systole and twice the torsion of other arteries. Second generation Everolimus eluting stents were used in this series and the morphology of aneurysms were similar to two patients with Sirolimus eluting 2nd generation stents. There was significant ISR in all of them. In an aneurysm there is slow flow of blood which predisposes to thrombus formation, but IVUS of patient A did not reveal any thrombus. The patients were followed with standard dual anti platelet drugs to minimize stent thrombosis. In patient C the small aneurysms formed were healed after opening the distal ISR segment.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics and treatment profile of all patients who developed aneurysms after Everolimus eluting Xience stents

| Patient A | Patient B | Patient C | Patient D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age | 68 years | 69 years | 71 years | 54 years |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Male |

| Hypertension | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | Yes | No | No |

| Lesion characteristic | ||||

| Long/diffuse lesion (> 20 mm) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| % Stenosis | 100% | 90–95% | 80% | 99% |

| Artery involved | LAD | LAD | RCA | LAD |

| Initial angioplasty details | ||||

| Stent size deployed | 2.75 × 28 mm | 2.75 × 33 mm | 2.5 × 38 mm | 3 × 28 mm |

| Stent type | Xience V | Xience Prime LL | Xience Prime LL | Xience V |

| Metal alloy in stent | L605 cobalt chromium | L605 cobalt chromium | L605 cobalt chromium | L605 cobalt chromium |

| Drug polymer | Acrylate primer and a fluorinated copolymer | Acrylate primer and a fluorinated copolymer | Acrylate primer and a fluorinated copolymer | Acrylate primer and a fluorinated copolymer |

| Drug eluting | Everolimus | Everolimus | Everolimus | Everolimus |

| Post dilatation | 3 mm at 15 atm | 3 mm at 13 atm | 2.75 mm at 16 atm | 3.5 mm at 15 atm |

| Dual anti-platelet drugs | Ticagrelor + ecospirin | Clopidogrel + ecospirin | Clopidogrel + ecospirin | Ticagrelor + ecospirin |

| Patient re admission presentation | ||||

| Fever | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Unstable angina | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Days after initial angioplasty | 4 months | 3.5 months | 2.5 months | 7 months |

| TLC during re-admission | 6600/µL | 7900/µL | 9700/µL | 8200/µL |

| Eosinophil count | 600/µL | 800/µL | 1500/µL | 800/µL |

| Aneurysm details | One large saccular aneurysm | Three large saccular aneurysms | Two–three small fusiform aneurysms | Two large saccular aneurysms |

| Arterial segment involved | Proximal LAD | Proximal LAD | Distal RCA | Left main and proximal LAD |

| Second admission treatment | ||||

| Angioplasty | Covered stent (3.5 × 26 mm) | Covered stent (3.5 × 19 mm) | Drug eluting stent (2.75 × 23 mm) | Operative repair and grafting |

| Outcome | Expired | Expired | Alive | Alive |

Coronary aneurysm after stent implantation is a grey area and the exact etiology is difficult to define. In our case series mycotic aneurysms are ruled out. There was no instance of dissection or high pressure balloon dilatation moreover we saw more sub-acute diffuse aneurysms including one extending to Left main artery. Therefore type I aneurysms are unlikely. Within type II aneurysm both the stent metal and more commonly the drug polymer causes hypersensitive coronary vasculitis according to various pathological studies. Also patient C had elevated IgE on follow up. While the cobalt chromium alloy can occasionally cause allergy in patients it is commoner in females [9]. In our series patients were predominantly male (75%). Moreover metal allergy predominantly presents as recurrent ISR rather than aneurysm formation [9]. The primer in Xience stents contains Methacrylate (previously used in Cypher stents and also a component of bone cement) which has been known to cause allergic reactions including coronary aneurysm formation in a number of studies [5–8] and we hypothesize that it can be an additional causal agent. Treatment of coronary aneurysms may vary [10]. Small chronic aneurysms can be followed up vigilantly. Whereas giant, enlarging, infected aneurysms presenting acutely should be emergently treated with operative repair [11, 12], covered stent [13–15] or coil. In our study operative aneurysmal repair with grafting had better results especially for giant stent induced type II aneurysms over percutaneous covered stenting.

Limitations

The major limitations of our study was an absence of histopathological examination of aneurysmal segments to clearly delineate the cause, the use of regionally available stents and limitations related to single centre non randomized study. Also patient A and B had low LVEF and died at an outside hospital so the death was due to heart failure or a possible complication of covered stent deployment cannot be ascertained.

Conclusion

Our case series highlight two valuable research areas. One is the possibility of methacrylate promoting a hypersensitivity reaction and contributing to formation of Type II stent induced coronary aneurysms. Second is identifying the right patient with giant stent induced type II aneurysm who will benefit from operative repair versus covered stent placement. Both needs to be substantiated by further studies.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Video S1. Angiogram of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 2: Video S2. Angiogram of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 3: Video S3. Intravascular ultrasound of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 4: Video S4. Patient B—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm.

Additional file 5: Video S5. Patient B—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm.

Additional file 6: Video S6. Patient C—Coronary angiogram showing small aneurysms.

Additional file 7: Video S7. Patient D—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm involving left main coronary artery.

Acknowledgements

There is no special acknowledgement regarding this article.

Abbreviations

- IVUS

Intravascular ultrasound

- LVEF

Left ventricle ejection fraction

- DES

Drug eluting stent

- BMS

Bare-metal stent

- RCA

Right coronary artery

- LAD

Left anterior descending

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- ISR

In stent restenosis

- CAG

Coronary angiogram

Authors' contributions

RS and AVR collected the data and AVR wrote the manuscript which was edited by RS. For the Angiograms and stent deployment RS was the primary operator assisted by AVR. Operative repair was done by TSM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work. The article has been formulated purely for the better advancement of medical science for patient benefit.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since this is a retrospective case series without any change in the treatment protocol of any of the patients and only involves observation therefore ethical committee clearance was not required. All data of patient identification has been hidden from the final dataset of the article and there was no involvement of any animal in this case series. The study was conducted according to the Helsinki Declarations. The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate.

Consent for publication

Written consent for submission and publication of this case series including the personal or clinical details along-with identifying images or associated movie if any has been obtained by the patients or relatives of the deceased whichever was applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Raghav Sharma, Email: drraghavsru@gmail.com, http://www.meditrinahospitals.com/ambala.html.

Aditya Vikram Ruia, Email: adityavruia@gmail.com.

Tek Singh Mahant, Email: drmahant@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Sheikh AS, Hailan A, Kinnaird T, Choudhury A, Smith D. Coronary artery aneurysm: evaluation, prognosis, and proposed treatment strategies. Heart Views Off J Gulf Heart Assoc. 2019;20(3):101–108. doi: 10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_1_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki J, Kirtane A, Leon MB, Dangas G. Coronary artery aneurysms after drug-eluting stent implantation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding N, Pacetti S, Tang F-W, Gada M, Roorda W. XIENCE VTM stent design and rationale. J Interv Cardiol. 2009;22:S18–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2009.00450.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Purple Medical Solutions. Purple Medical Solution Pvt ltd: Treat stents. 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 30]. Available from http://purplemedicalsolutions.com/Treat.html.

- 5.Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Grieco N, Motta T, et al. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus-eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004;109(6):701–705. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leggat PA, Kedjarune U. Toxicity of methyl methacrylate in dentistry. Int Dent J. 2003;53(3):126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2003.tb00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed DDF, Sobczak SC, Yunginger JW. Occupational allergies caused by latex. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2003;23(2):205–219. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8561(02)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pretorius E. Allergic reactions caused by dental restorative products. SADJ J South Afr Dent Assoc Tydskr Van Suid-Afr Tandheelkd Ver. 2002;57(9):372–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Univers J, Long C, Tonks SA, Freeman MB. Systemic hypersensitivity reaction to endovascular stainless steel stent. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(2):615–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawsara A, Núñez Gil IJ, Alqahtani F, Moreland J, Rihal CS, Alkhouli M. Management of coronary artery aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(13):1211–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyser A, Hilker MK, Husser O, Diez C, Schmid C. Giant coronary aneurysms exceeding 5 cm in size. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15(1):33–36. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivs111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawley PD, Mahlow WJ, Huntsinger DR, Afiniwala S, Wortham DC. Giant coronary artery aneurysms: review and update. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(6):603–608. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-13-3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eshtehardi P, Cook S, Moarof I, Triller H-J, Windecker S. Giant coronary artery aneurysm. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1(1):85–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.107.763656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhindi R, Testa L, Ormerod OJ, Banning AP. Rapidly evolving giant coronary aneurysm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(4):372. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okamura T, Hiro T, Fujii T, Yamada J, Fukumoto Y, Hashimoto G, et al. Late giant coronary aneurysm associated with a fracture of sirolimus eluting stent: a case report. J Cardiol. 2008;51(1):74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Video S1. Angiogram of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 2: Video S2. Angiogram of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 3: Video S3. Intravascular ultrasound of Patient A showing coronary aneurysm.

Additional file 4: Video S4. Patient B—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm.

Additional file 5: Video S5. Patient B—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm.

Additional file 6: Video S6. Patient C—Coronary angiogram showing small aneurysms.

Additional file 7: Video S7. Patient D—Coronary angiogram showing giant aneurysm involving left main coronary artery.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.