Abstract

In a search for tools to distinguish antigenic variants of Ehrlichia ruminantium, we sequenced the major antigenic protein genes (map1 genes) of 21 different isolates and found that the sequence polymorphisms were too great to permit the design of probes which could be used as markers for immunogenicity. Phylogenetic comparison of the 21 deduced MAP1 sequences plus another 9 sequences which had been previously published did not reveal any geographic clustering among the isolates. Maximum likelihood analysis of codon and amino acid changes over the phylogeny provided no statistical evidence that the gene is under positive selection pressure, suggesting that it may not be important for the evasion of host immune responses.

Ehrlichia ruminantium (6), the tick-borne causative agent of heartwater in domestic and wild ruminants, is widespread throughout sub-Saharan Africa, in Madagascar, and on some islands in the Caribbean. Mortality rates among susceptible hosts can reach 90% (18), and the design of any potential vaccine is complicated by the fact that field isolates differ in immunogenicity (10). Oligonucleotide probes based on the most variable region of the E. ruminantium 16S gene distinguish five different genotypes (2), but little genetic information is available for the distinction of immunogenic variants.

E. ruminantium has an immunodominant polymorphic gene (map1) which appears to be single copy (4, 12) and which codes for a major antigenic surface protein of about 32 kDa (19). map1 has been suggested as a useful marker for isolates from different geographical areas (14), and we wished to determine whether it might be a suitable target for the development of variant-specific probes. We therefore sequenced map1 genes from 21 new E. ruminantium isolates and compared the data with 9 previously published map1 sequences.

The closely related organisms Ehrlichia canis and Ehrlichia chaffeensis have families of immunodominant major surface antigens (28 to 30 kDa), the sequences and expression of which have been extensively studied with a view to the development of serodiagnostic reagents (12, 22). However, there is no information on whether these genes are polymorphic between different isolates of E. canis and E. chaffeensis, as is E. ruminantium map1.

DNA was extracted from the 21 E. ruminantium isolates detailed in Table 1 using a commercial kit (QIAamp DNA mini kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and was subjected to PCR using the degenerate primers Fmap1 and Rmap1 (2). Single amplicons of ∼870 bp were obtained from tissue culture-derived material, but multiple amplicons were obtained from ticks and blood stabilates. Amplicons of the appropriate size were gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T (pGEM-T Vector systems; Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Transformants containing E. ruminantium map1 inserts were identified by probing with a random prime-labeled E. ruminantium Welgevonden map1 amplicon as described previously (2) and were sequenced from both ends on an ABI 377 automated sequencer. The new map1 gene sequences were deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers indicated in Table 1. The 21 sequences were aligned with 9 previously published E. ruminantium map1 sequences (Table 1), and the sequence of the Anaplasma marginale major surface protein 4 gene (msp4) was used as an out-group to root the phylogenetic trees. Alignment was carried out using CLUSTALW (17) and manually adjusted using the SEQLAB multiple alignment program (version 10-1, GCG).

TABLE 1.

E. ruminantium isolates for which major antigenic protein gene sequences are available

| Isolatea | Source | Origin | 16S genotype | Accession no.b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antigua | Tissue culture | Caribbean | U50830 | |

| Ball3 | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Ball3 | AF355200 |

| Blaauwkrans | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | NDc | AF368000 |

| Burkina Faso | Tissue culture | Western Africa | ND | AF368001 |

| Cameroun | Tissue culture | Western Africa | ND | AF355203 |

| Crystal Springs | Tissue culture | Zimbabwe | Crystal Springs | U50831 |

| Gardel | Tissue culture | Guadeloupe | Gardel | U50832 |

| Highway | Tissue culture | Zimbabwe | U50833 | |

| Kiswani | Tissue culture | Kenya | ND | AF368003 |

| Kümm1d | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Senegal | Identical to that of Senegalf |

| Kümm2d | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Omatjenne | Identical to that of Omatjennef |

| Kwanyanga | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Crystal Springs | AF368004 |

| Lemco | Tissue culture | Zimbabwe | AF125277 | |

| Ludlow | Tick | Southern Africa | Crystal Springs | AF368005 |

| Lutale | Tissue culture | Zambia | ND | AF355201 |

| Mali | Tissue culture | Western Africa | Senegal | AF368007 |

| Mara 87/7 | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Mara 87/7 | AF368008 |

| Morgenswag 1e | Goat blood | Southern Africa | ND | AF368009 |

| Morgenswag 2e | Goat blood | Southern Africa | ND | AF368010 |

| Nonile | Sheep blood stabilate | Southern Africa | Crystal Springs | AF368011 |

| Nyatsanga | Tissue culture | Zimbabwe | U50834 | |

| Omatjenne | Sheep blood stabilate | Namibia | Omatjenne | AF368012 |

| Pokoase | Tissue culture | Ghana | Senegal | AF368013 |

| Sankat | Tissue culture | Ghana | Senegal | AF368014 |

| S. E. Botswana | Tick | Botswana | Crystal Springs | AF368015 |

| Senegal | Tissue culture | Western Africa | Senegal | X74250 |

| Um Banein | Tissue culture | Sudan | U50835 | |

| Umpala | Tissue culture | Mozambique | ND | AF355202 |

| Vosloo | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Crystal Springs | AY028378 |

| Welgevonden | Tissue culture | Southern Africa | Crystal Springs | U49843 |

New E. ruminantium isolates are in boldface type.

New accession numbers are in boldface type.

ND, not done.

Two different genotypes isolated in culture from the Kümm field isolate (E. Zweygarth, unpublished data).

Two different genotypes found in the blood of a single animal.

Sequence not submitted to GenBank.

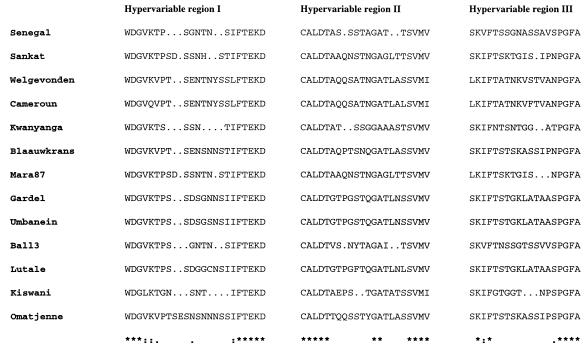

The nucleotide alignment was used to infer an amino acid alignment of 293 positions within which polymorphisms were concentrated in three hypervariable regions (Fig. 1), each about 10 to 15 amino acids long; these were located around positions 85, 160, and 260. Identical nucleotide sequences were obtained for five pairs among the 30 isolates: Mali-Sankat, Omatjenne-Kümm2, Ludlow-Kiswani, Senegal-Kümm1, and Kwanyanga-Lemco. Other workers have stated (16) that their sequence of Welgevonden map1 is the same as that of Lemco map1 (AF125277) and different from the published Welgevonden map1 sequence (U49843). Sequence U49843, however, has been obtained from three different batches of Welgevonden-infected tissue culture-derived DNA treated in three different ways; two of these (identical) sequences were obtained from clones isolated from two different genomic libraries (4, 5) constructed in a South African laboratory (OVI), and the third was obtained after PCR amplification of the gene in a laboratory on Guadeloupe (CIRAD).

FIG. 1.

All MAP1 hypervariable regions for isolates in which differences occur. At the bottom of the figure, asterisks denote identical amino acids, colons denote strong amino acid similarity, and periods denote weak amino acid similarity.

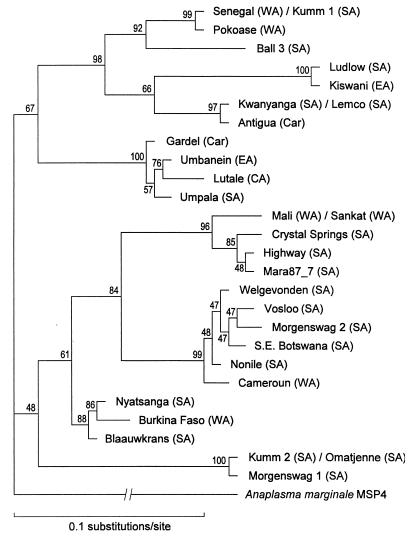

A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny of the MAP1 amino acid sequences was inferred using the MOLPHY 2.3 package (1) and the PHYLIP 3.5c package (7). Briefly, a distance matrix was calculated using “njdist” (MOLPHY) with the JTT-F model (8), and this was used to infer a Fitch tree using “fitch” (PHYLIP), with A. marginale MSP4 as the out-group. This tree was then used as the initial tree from which the ML tree was inferred by local rearrangements using “protml” (MOLPHY) with the JTT-F model, with bootstrap values calculated for each internal branch. The resulting phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2), the topology of which was identical to that of the initial Fitch tree, was drawn using “njplot” (13). Various phylogenetic analyses of the nucleotide sequences also consistently yielded trees with almost identical topology (data not shown), indicating that the inferred phylogenetic relationships are robust to different methods of tree estimation.

FIG. 2.

ML tree with bootstrap values of MAP1 sequences from 30 isolates of E. ruminantium. Two names on one branch indicate identical amino acid sequences. Notations in parentheses indicate geographical origins: WA, Western Africa; EA, Eastern Africa; SA, Southern Africa; and Car, Caribbean (French Antilles).

The phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2) indicates clearly that there is no geographical distribution specificity among the MAP1 variants: there are well-defined clusters, several of which contain isolates from widely distributed locations. Isolates within a cluster do not share a virulence phenotype or 16S genotype, and the sequence variations are too great to design cluster-specific probes. One reason for these observations could be that high levels of recombination are occurring between different lineages, and to investigate this, we performed a linkage disequilibrium analysis (3). This revealed moderately low levels of linkage disequilibrium in these data and no decline in the level of linkage disequilibrium between sites that were further apart, so there is no strong evidence for frequent map1 recombination among these lineages. Examination of levels of silent and nonsilent nucleotide substitutions along the nucleotide alignment, based on permutation tests of averaged site-by-site pairwise sequence comparisons, revealed that silent variation was evenly distributed along the gene but that nonsilent changes were significantly (P < 0.05) clustered at two locations, corresponding to the first (most 5′) hypervariable region and the third (most 3′) hypervariable region but not to the central one.

The wide sequence variation of MAP1, coupled with the fact that it is strongly serologically immunodominant (9), suggests that the protein may be involved in evading attack by the host's immune system. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the aligned data set and the inferred ML tree using the M3(n) model in the codeml program from the PAML package (20, 21). This model assumes that during sequence evolution different codons have undergone different ratios of nonsilent to silent base substitutions (dn:ds) (11) and that the dn:ds values can be assigned to n different categories. The maximum likelihood of the model is calculated with increasing values of n, and the model for that value of n where the likelihood no longer increases significantly is the accepted model. If a category of codons in this model has a dn:ds value of >1 (15), this is taken as evidence of positive selection pressure acting on the codons in that category. The results are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Results of codeml analysis of aligned map1 dataset

| n | dn:ds | % of codons | dn:ds | % of codons | dn:ds | % of codons | LLa | χ2b | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.102 | 100 | 3838.3 | ||||||

| 2 | 0.540 | 20 | 0.024 | 80 | 3709.0 | 258.6 | <0.001 | ||

| 3 | 0.860 | 9 | 0.230 | 19 | 0.014 | 72 | 3704.3 | 9.4 | <0.01 |

LL, log ML.

χ2 for 2 degrees of freedom = 2(LLn+1 − LLn).

The 3-category model, which was found to be preferred over the 2- or 4-category model, had 9% of the codons assigned to a category where dn:ds was equal to 0.86. This analysis, therefore, does not provide statistically significant support for positive selection pressure. It is possible that positive selection pressure does occur but that conformational constraints on the MAP1 molecule act to reduce the value of dn:ds below the critical threshold, but there is currently no theory which allows such an effect to be quantified. The lack of support for positive selection pressure on map1, despite the fact that MAP1 is serologically immunodominant, possibly suggests that this protein is not important in allowing the parasite to evade the host immune response, but the reason for the extensive polymorphism remains unclear. In this event, it seems unlikely that the gene will be useful as a vaccine candidate, a suggestion recently supported by other researchers (A. Nyika, S. M. Mahan, A. F. Barbet, and M. J. Burridge, unpublished data).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The gene sequences of the new map1 isolates have been deposited with GenBank and given the following accession numbers: Ball3, AF355200; Blaauwkrans, AF368000; Burkina Faso, AF368001; Cameroun, AF355203; Kiswani, AF368003; Kwanyanga, AF368004; Ludlow, AF368005; Lutale, AF355201; Mali, AF368007; Mara 87/7, AF368008; Morgenswag 1, AF368009; Morgenswag 2, AF368010; Nonile, AF368011; Omatjenne, AF368012; Pokoase, AF368013; Sankat, AF368014; S. E. Botswana, AF368015; Umpala, AF355202; and Vosloo, AY028378.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by the Agricultural Research Council of South Africa and the European Union Cowdriosis Network grant no. IC18-CT95-0008 (DG1-SNRD).

We thank Isabel Chantal for assistance with the map1 sequences of the Cameroun, Vosloo, Lutale, Burkina Faso, and Umpala isolates of E. ruminantium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi J, Hasegawa M. MOLPHY version 2.3: programs for molecular phylogenetics based on maximum likelihood Computer science monographs no. 28. Tokyo, Japan: The Institute for Statistical Mathematics; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allsopp M T, Hattingh C M, Vogel S W, Allsopp B A. Evaluation of 16S, map1 and pCS20 probes for detection of Cowdria and Ehrlichia species. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:323–328. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Awadalla P, Eyre-Walker A, Smith J M. Linkage disequilibrium and recombination in hominid mitochondrial DNA. Science. 1999;286:2524–2525. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brayton K A, Fehrsen J, de Villiers E P, van Kleef M, Allsopp B A. Construction and initial analysis of a representative lambda ZAPII expression library of the intracellular rickettsia Cowdria ruminantium: cloning of map1 and three other Cowdria genes. Vet Parasitol. 1997;72:185–199. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Villiers E P, Brayton K A, Zweygarth E, Allsopp B A. Genome size and genetic map of Cowdria ruminantium. Microbiology. 2000;146:2627–2634. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dumler, J. S., A. F. Barbet, C. Bekker, G. A. Dasch, F. Jongejan, G. H. Palmer, S. C. Ray, Y. Rikihisa, and F. R. Rurangirwa. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales; unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma and Cowdria, and some species of Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia; descriptions of five new species combinations; and designation of Ehrlichia equi and “HGE agent” as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1988;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones D T, Taylor W R, Thornton J M. The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput Appl Biosci. 1992;8:275–282. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jongejan F, Thielemans M J. Identification of an immunodominant antigenically conserved 32-kilodalton protein from Cowdria ruminantium. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3243–3246. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3243-3246.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jongejan F, Thielemans M J, Briere C, Uilenberg G. Antigenic diversity of Cowdria ruminantium isolates determined by cross-immunity. Res Vet Sci. 1991;51:24–28. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(91)90025-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen R, Yang Z. Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics. 1998;148:929–936. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohashi N, Unver A, Zhi N, Rikihisa Y. Cloning and characterization of multigenes encoding the immunodominant 30-kilodalton major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia canis and application of the recombinant protein for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2671–2680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2671-2680.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perriere G, Gouy M. WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy G R, Sulsona C R, Harrison R H, Mahan S M, Burridge M J, Barbet A F. Sequence heterogeneity of the major antigenic protein 1 genes from Cowdria ruminantium isolates from different geographical areas. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:417–422. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.4.417-422.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharp P M. In search of molecular Darwinism. Nature. 1997;385:111–112. doi: 10.1038/385111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulsona C R, Mahan S M, Barbet A F. The map1 gene of Cowdria ruminantium is a member of a multigene family containing both conserved and variable genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:300–305. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uilenberg G. Heartwater (Cowdria ruminantium infection): current status. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med. 1983;27:427–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Vliet A H, Jongejan F, van Kleef M, van der Zeijst B A. Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and expression of the gene encoding the immunodominant 32-kilodalton protein of Cowdria ruminantium. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1451–1456. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1451-1456.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z. PAML: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Nielsen R, Goldman N, Pedersen A M. Codon-substitution models for heterogeneous selection pressure at amino acid sites. Genetics. 2000;155:431–449. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu X, McBride J W, Zhang X, Walker D H. Characterization of the complete transcriptionally active Ehrlichia chaffeensis 28 kDa outer membrane protein multigene family. Gene. 2000;248:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]