Abstract

DNA samples from dogs presenting with symptoms suggestive of canine ehrlichiosis, but with no morulae detected on blood smears, frequently failed to give a positive reaction with a North American Ehrlichia canis-specific PCR assay targeting the 16S rRNA gene. We suspected the presence of a pathogen genetically different from North American E. canis, and we performed experiments to test this hypothesis. DNA from one canine blood sample was subjected to PCR with primers designed to amplify Ehrlichia (Cowdria) ruminantium ruminantium 16S and map1 genes. Amplicon sequencing yielded 16S and map1 sequences which were more closely related to other E. ruminantium sequences than to those of any other Ehrlichia species. Fifty canine DNA samples were subjected to a PCR assay, previously found to be Cowdria-specific, which targets the pCS20 gene. Thirty-seven (74%) gave a positive signal, and 16 (32%) also gave visible amplicons after gel electrophoresis, suggesting that this E. ruminantium organism is common in the Pretoria-Johannesburg area. The organism has not been isolated in culture, so we cannot definitively state that it was responsible for the canine ehrlichiosis symptoms, although the occurrence of several similar cases suggests this to be so. Most importantly, we also do not yet know whether the organism is infective for, or causes heartwater in, ruminants.

Canine ehrlichiosis is a disease syndrome common and widespread in dogs in tropical and subtropical regions. Animals infected only with Ehrlichia canis may not exhibit acute symptoms (12), but hemorrhagic forms of the disease may be fatal (14). In South Africa, dogs frequently become coinfected with both Babesia canis and E. canis. Infection with the former species is usually readily recognized by the presence of piroplasms in blood smears, but ehrlichial morulae are usually difficult to detect because of low parasite numbers (10). If there are no acute symptoms, then anorexia and generalized debility, coupled with characteristic but nonspecific hematological changes, are taken to be suggestive of ehrlichiosis. Various serological tests are available for the diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis (13), but cross-reactions with other Ehrlichia species preclude definitive diagnosis. Cell culture isolation of the parasite is both sensitive and specific (15), but it requires 1 to 4 weeks before results are obtained, so it cannot be used for routine diagnosis. A highly specific and sensitive PCR assay for E. canis, based on the 16S sequence of the Louisiana isolate of E. canis, has been developed in the United States (18). This test is used at Onderstepoort to confirm the presence of E. canis in dogs with clinical symptoms typical of ehrlichiosis but without morulae on blood smears. Very few of the samples tested yielded a positive result.

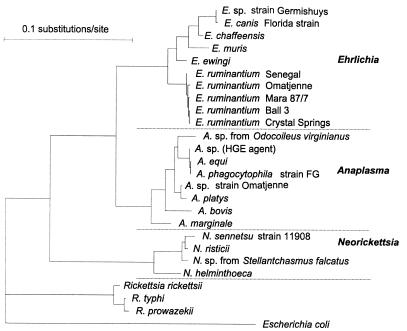

The genus Ehrlichia (Fig. 1) comprises a group of organisms of which the classification has recently been revised (11). The genus includes several recently identified organisms: the human pathogen Ehrlichia chaffeensis (24); the dog pathogen Ehrlichia ewingii (5), later found to also infect humans (7); and the mouse pathogen Ehrlichia muris (26). The genus includes Ehrlichia (Cowdria) ruminantium, which was originally thought to be a single species which causes heartwater in ruminants (8). It is now known that E. ruminantium comprises a clade (Fig. 1) of several closely related organisms (3), some of which may not cause heartwater and which may therefore need to be reclassified when more information is at hand. The growing number of new species being recognized in the genus Ehrlichia led us to propose that the dogs which presented with symptoms suggestive of canine ehrlichiosis, but which were negative for E. canis Louisiana, were carrying a previously unrecognized pathogen. To test this hypothesis, we amplified and probed for 16S genes from blood samples of 50 such dogs.

FIG. 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of some ehrlichial species based on comparison of 16S ribosomal RNA genes. The phylogenetic position of the canine E. ruminantium is not differentiated from that of E. ruminantium Mara 87/7. Abbreviations: E., Ehrlichia; A., Anaplasma; N., Neorickettsia; and R., Rickettsia.

The samples used in this study came from several sources. Many were from apparently healthy animals held in quarantine kennels, which were the subject of routine testing after importation into South Africa or which required clearance certificates for export. Other samples came from animals presenting with clinical symptoms of ehrlichiosis but with no evidence of Ehrlichia morulae, either from the University of Pretoria Veterinary Faculty's companion animal clinic or from private veterinary clinics in Pretoria. The samples from the kennels and from the companion animal clinic had been tested and found negative using the E. canis Louisiana-specific PCR test (18).

DNA was purified from canine blood using the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol and was eluted from the columns with 100 μl of the proprietary elution buffer supplied with the kit. Using primers (Table 1) which amplify the V1 hypervariable region of Ehrlichia 16S genes (3) and a protocol described elsewhere (2), a PCR (50-μl reaction volume) was carried out on 5-μl aliquots of each sample. Positive controls consisted of cloned, near full-length 16S genes of organisms of South African origin related to E. canis. These were Anaplasma sp. strain Omatjenne (previously Ehrlichia sp. strain Omatjenne), Ehrlichia sp. strain Germishuys, and the Welgevonden isolate of E. ruminantium (9). Amplification products were slot blotted onto nylon membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham International) and probed with radioactively labeled oligonucleotides (Table 2) which detect (i) any Anaplasma species, (ii) any Ehrlichia sp. other than E. ruminantium, and (iii) E. ruminantium only (3). Fifty samples were examined, and none gave a signal with the probes for any Anaplasma sp. or any Ehrlichia sp. other than E. ruminantium. Thirty six (72%) gave a positive signal with the E. ruminantium-specific 16S probe (3).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for amplificationa

| Target | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-length 16S gene of any species in the family Anaplasmataceae | fD1 | CCGAATTCGTCGCAACAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG | 25 | |

| B | CCCGGGATCCAAGCTTGATCCTTCTGCAGGTTCACCTAC | 19 | ||

| V1 loop of 16S gene of any species in the order Rickettsiales | 930 | GCTTAACACATGCAAGTC | 3 | |

| BAA5 | CCCATTGTCCAATATTCC | |||

| Full-length map1 gene of any E. ruminantium | Fmap1 | ATGAATTRCARRRAAWTKTTT | 4 | |

| Rmap1 | AYABRAAYCTTSCTCCAA | |||

| Full-length pCS20 gene of any E. ruminantium | AB128 | ACTAGTAGAAATTGCACAATCTAT | 23 | |

| AB129 | TGATAACTTGGTGCGGGAAATCCTT |

Ambiguity codes according to International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry convention.

TABLE 2.

Probes used to detect ampliconsa

| Target | Probe | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any E. ruminantium 16S (V1 loop) | BAA15 | ATTTCTAATAGCTATTCCAT | 3 |

| Any Ehrlichia 16S (V1 loop) other than E. ruminantium | BAA16 | ATTTCTAATGGCTATTCC | 3 |

| Any Anaplasma 16S (V1 loop) | BAA17 | YTTCTAGTGGCTATCCYA | 3 |

| map1 gene of any E. ruminantium | E. ruminantium Welgevonden map1 gene | U49843 (GenBank) | 6 |

| pCS20 gene of any E. ruminantium | E. ruminantium Crystal Springs pCS20 gene | X58242 (GenBank) | 23 |

Ambiguity codes according to International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry convention..

A PCR assay which targets the pCS20 gene, and which has previously been found to be Cowdria-specific (17), was performed. Visible amplicons of the expected size were obtained from 16 (32%) of the samples, indicating a relatively high level of target DNA, whereas a total of 37 (74%) samples gave positive hybridization signals with the pCS20 probe.

One DNA sample, which gave strong signals with both pCS20 and E. ruminantium 16S probes, was amplified using primers (Table 1) to obtain a near full-length 16S gene. Amplicons of the appropriate size (∼1,400 bp) were gel purified and cloned into pGEM-T according to the manufacturer's protocol (pGEM-T Vector Systems; Promega Corporation, Madison, Wis.), and transformants were screened for E. ruminantium 16S recombinants using the E. ruminantium-specific probe (Table 2). Positive recombinants were sequenced, and the sequence of the canine Ehrlichia 16S gene was deposited in GenBank.

The DNA sample noted in the previous paragraph was also amplified with degenerate primers (Table 1) which amplify the polymorphic map1 gene of any E. ruminantium strain. A band of ∼870 bp, the expected size of the coding region of the map1 gene, was excised from the gel and cloned into pGEM-T, and transformants were screened for map1 recombinants using an E. ruminantium Welgevonden map1 probe (Table 2). Positive recombinants were sequenced from both ends, and the sequence of the canine Ehrlichia map1 gene was deposited in GenBank.

Alignments of the new 16S and map1 sequences were carried out with a range of published homologues using CLUSTALW (22) and manually adjusted using the SEQLAB multiple alignment program (version 10-1; GCG). A maximum likelihood phylogeny of the MAP1 derived amino acid sequence was inferred using the PROTML program from the MOLPHY (version 2.3) package (1), and the 16S phylogeny was inferred using the FastDNAML algorithm (20). Phylogenetic trees were drawn using “njplot” (21).

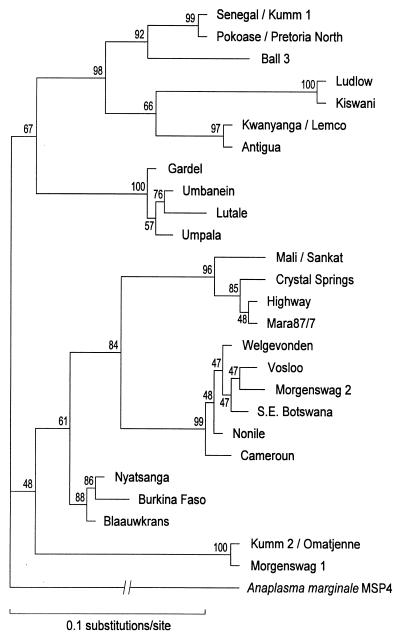

The canine Ehrlichia 16S gene sequence was identical over the hypervariable V1 loop with that of the Mara 87/7 isolate of E. ruminantium (4), but elsewhere in the sequence were single nucleotide polymorphisms which differentiated this canine isolate from E. ruminantium Mara 87/7 in the 16S phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1). These 16S sequence data, and the E. ruminantium-specific pCS20 probe hybridization information (4), show that the organism detected in 37 of the 50 dogs is phylogenetically E. ruminantium and differs from E. canis Louisiana. The map1 gene sequence differed by 1 bp from, and the deduced MAP1 sequence was identical to that of, a Ghanaian E. ruminantium isolate (Pokoase). The new canine isolate, as well as E. ruminantium Pokoase, clustered with E. ruminantium Senegal in the inferred MAP1 phylogeny (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on MAP1 deduced amino acid sequences of various E. ruminantium isolates. The canine E. ruminantium MAP1 is designated Pretoria North. The figures at the nodes indicate bootstrap confidence levels for 100 replicates.

Of 17 samples from dogs presently held in quarantine, 2 were from Ethiopia, 2 were from Mali, 3 were from Uganda, and 2 were from Kenya. Eight of these dogs were pCS20 probe positive, suggesting that they had acquired an E. ruminantium infection before their arrival in the country. Other workers have shown that dogs infected experimentally with E. ruminantium Crystal Springs did not become sick but showed visible pCS20 amplicons for up to 3 weeks after infection (16). This indicates that, although some dogs may show symptoms suggestive of ehrlichiosis, apparently healthy dogs may be asymptomatic carriers of E. ruminantium.

This E. ruminantium organism has not been isolated in culture or tested for its infectivity to dogs. Until this has been done, we cannot state definitively that E. ruminantium was the cause of the illness in the animal from which the 16S and map1 sequences were derived. It is known that several closely related organisms comprise the clade known as E. ruminantium (Fig. 1) and that some of them may not cause heartwater, even in ruminants (3). The finding of a genotype of E. ruminantium which infects dogs further emphasizes the multiplicity of organisms which molecular techniques have been able to reveal in the diverse genus Ehrlichia.

This E. ruminantium organism infecting dogs must be established in culture before its pathogenicity and host specificity can be determined, and the vector must also be identified. If it is found to be confined to canids, it cannot be described as E. ruminantium and should receive a different specific name. If, on the other hand, it is found to cause heartwater symptoms in ruminants, and/or is transmittable by Amblyomma species ticks, then dogs carrying the organism could represent a potential reservoir of heartwater.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequence of the canine Ehrlichia 16S gene was deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF325175, and the sequence of the canine Ehrlichia map1 gene was deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF325176.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. W. Vogel for dog blood samples from private veterinary clinics and A.-M. Bosman for canine DNA samples.

This research was funded by the Agricultural Research Council of South Africa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi J, Hasegawa M. MOLPHY version 2.3: programs for molecular phylogenetics based on maximum likelihood. Computer Science Monographs no. 28. Tokyo, Japan: The Institute for Statistical Mathematics; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allsopp B A, Baylis H A, Allsopp M T, Cavalier Smith T, Bishop R P, Carrington D M, Sohanpal B, Spooner P. Discrimination between six species of Theileria using oligonucleotide probes which detect small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. Parasitology. 1993;107:157–165. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000067263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allsopp M, Visser E S, du Plessis J L, Vogel S W, Allsopp B A. Different organisms associated with heartwater as shown by analysis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Vet Parasitol. 1997;71:283–300. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allsopp M T, Hattingh C M, Vogel S W, Allsopp B A. Evaluation of 16S, map1 and pCS20 probes for detection of Cowdria and Ehrlichia species. Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:323–328. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899002101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson B E, Greene C E, Jones D C, Dawson J E. Ehrlichia ewingii sp. nov., the etiologic agent of canine granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:299–302. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brayton K A, Fehrsen J, de Villiers E P, van Kleef M, Allsopp B A. Construction and initial analysis of a representative lambda ZAPII expression library of the intracellular rickettsia Cowdria ruminantium: cloning of map1 and three other Cowdria genes. Vet Parasitol. 1997;72:185–199. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buller R S, Arens M, Hmiel S P, Paddock C D, Sumner J W, Rikhisa Y, Unver A, Gaudreault-Keener M, Manian F A, Liddell A M, Schmulewitz N, Storch G A. Ehrlichia ewingii, a newly recognized agent of human ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:148–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowdry E V. Studies on the etiology of heartwater. I. Observation of a rickettsia. Rickettsia ruminantium (n. sp.), in the tissues of infected animals. J Exp Med. 1925;42:231–252. doi: 10.1084/jem.42.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du Plessis J L. A method for determining the Cowdria ruminantium infection rate of Amblyomma hebraeum: effects in mice injected with tick homogenates. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1985;52:55–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Plessis J L, Fourie N, Nel P W, Evezard D N. Concurrent babesiosis and ehrlichiosis in the dog: blood smear examination supplemented by the indirect fluorescent antibody test, using Cowdria ruminantium as antigen. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1990;57:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumler, J. S., A. F. Barbet, C. Bekker, G. A. Dasch, F. Jongejan, G. H. Palmer, S. C. Ray, Y. Rikihisa, and F. R. Rurangirwa. Reorganization of genera in the families Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae in the order Rickettsiales; unification of some species of Ehrlichia with Anaplasma and Cowdria, and some species of Ehrlichia with Neorickettsia; descriptions of five new species combinations; and designation of Ehrlichia equi and “HGE agent” as subjective synonyms of Ehrlichia phagocytophila. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ewing S A, Roberson W R, Buckner R G, Hayat C S. A new strain of Ehrlichia canis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1971;159:1771–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green C E, Harvey J W. Canine ehrlichiosis. In: Green C E, editor. Clinical microbiology and infectious diseases of the dog and cat. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 1990. pp. 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huxsoll D L, Hildebrandt P K, Nims R M, Ferguson J A, Walker J S. Ehrlichia canis—the causative agent of a haemorrhagic disease of dogs? Vet Rec. 1969;85:587. doi: 10.1136/vr.85.21.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iqbal Z, Rikihisa Y. Reisolation of Ehrlichia canis from blood and tissues of dogs after doxycycline treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1644–1649. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1644-1649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly P J, Matthewman L A, Mahan S M, Semu S, Peter T, Mason P R, Brouqui P, Raoult D. Serological evidence for antigenic relationships between Ehrlichia canis and Cowdria ruminantium. Res Vet Sci. 1994;56:170–174. doi: 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mahan S M, Waghela S D, McGuire T C, Rurangirwa F R, Wassink L A, Barbet A F. A cloned DNA probe for Cowdria ruminantium hybridizes with eight heartwater strains and detects infected sheep. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:981–986. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.981-986.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBride J W, Corstvet R E, Gaunt S D, Chinsangaram J, Akita G Y, Osburn B I. PCR detection of acute Ehrlichia canis infection in dogs. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1996;8:441–447. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medlin L, Elwood H J, Stickel S, Sogin M L. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene. 1988;71:491–499. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen G J, Matsuda H, Hagstrom R, Overbeek R. fastDNAmL: a tool for construction of phylogenetic trees of DNA sequences using maximum likelihood. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:41–48. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perriere G, Gouy M. WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waghela S D, Rurangirwa F R, Mahan S M, Yunker C E, Crawford T B, Barbet A F, Burridge M J, McGuire T C. A cloned DNA probe identifies Cowdria ruminantium in Amblyomma variegatum ticks. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2571–2577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2571-2577.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walker D H, Dumler J S. Emergence of the ehrlichioses as human health problems. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996;2:18–29. doi: 10.3201/eid0201.960102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen B, Rikihisa Y, Mott J, Fuerst P A, Kawahara M, Suto C. Ehrlichia muris sp. nov., identified on the basis of 16S rRNA base sequences and serological, morphological, and biological characteristics. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:250–254. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-2-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]