Abstract

A fungal infection of the brain of a 55-year-old male patient is reported. The lesion and involved fungus were located exclusively in the right medial temporo-parietal region. The patient was successfully treated with surgical resection of the lesion and antifungal chemotherapy. Few pathogenic dematiaceous fungi exhibit neurotropism and can cause primary infection in the central nervous system (CNS). The etiological agent is described as a Nodulisporium species. To date Nodulisporium has never been reported as an agent of CNS infection in humans.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old male patient was admitted to the neurosurgery facility of Nizam's Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS), Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India, with an admitting diagnosis of right choroidal meningioma.

Two months prior to admittance to NIMS, the patient experienced rapid deterioration of vision in the right eye along with associated numbness in the right half of the face. For 1 year prior to admittance he had also experienced difficulty in chewing food and intermittent episodes of transient loss of consciousness associated with weakness on the right side, mainly involving the limbs. The recovery time from such episodes was about 1 to 2 h. There was no history of generalized tonic or clonic seizures. He did not have a history of hypertension or diabetes and was not on any medication.

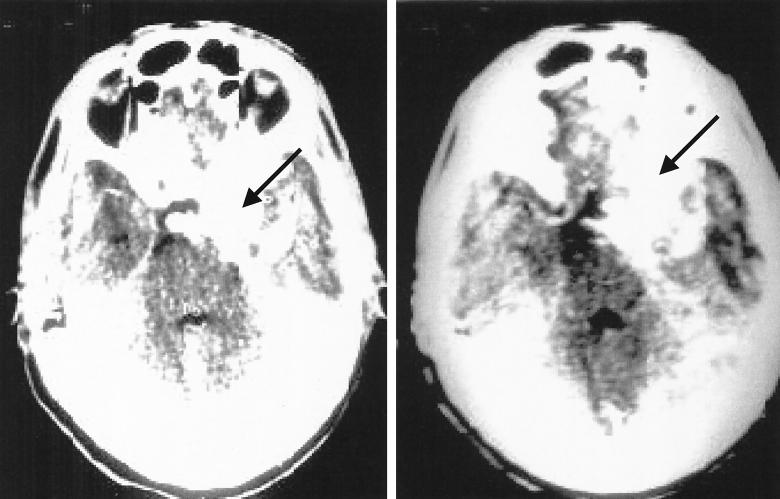

A computerized tomogram (CT) of the brain was performed by the referring hospital (Fig. 1). CT sections 5 mm thick were obtained in the posterior fossa, and CT sections 10 mm thick were obtained thereafter, both before and after administration of intravenous contrast (ionic contrast [40 ml of 76% Uro Video; Bracco]). The scan revealed a large, irregularly shaped, slightly hyperdense, densely enhancing lesion in the right medial temporo-parietal region of about 44.3 by 33.2 mm. It showed a large, irregular, hypodense white matter with surrounding edema. There was a shift in the midline structures to the left. The ventricular system and sulcal cerebrospinal fluid spaces were effaced more on the right. The overall impression was of a sphenoid meningioma in the right medial temporo-parietal region with cerebral edema. With these clinical details, the patient was referred to NIMS for further management.

FIG. 1.

(Left) CT scan of the brain showing the large, irregularly shaped, slightly hyperdense enhancing lesion in the right medial temporo-parietal region, extending to the orbit and the paranasal sinuses, with surrounding edema. (Right) CT scan of the brain at another level showing clearly the mass effect produced by the lesion, with shift of the midline structures to the left.

The patient was conscious and coherent. There were no signs of anemia, clubbing, or palpitation. His pulse and respiratory rate were within the normal range. There was no lymphadenopathy or organomegaly.

The right eye showed exophthalmos, with no pupillary light reaction and primary optic atrophy on fundus examination. The left eye was normal. Paresis of the right fifth and sixth cranial nerves was present. There was loss of motor and sensory components of the fifth cranial nerve. There were no other sensory or motor deficits.

The peripheral blood picture and biochemistry were within normal limits. Hemoglobin was 13.5 g%, packed cell volume was 39%, and total leukocyte counts and differential counts were within normal range. The test of anti-human immunodeficiency virus antibodies was nonreactive. Blood urea and serum creatinine were 45 and 0.7 mg%, respectively. The chest radiograph and two-dimensional echocardiogram of the heart were normal. With a diagnosis of right choroidal meningioma, the patient was scheduled for surgery and excision of the tumor.

The tumor was approached by a right temporal craniotomy. During the operation, a greyish white vascular lesion causing opening of the Sylvian fissure and spreading along either side of the sphenoid ridge into both the temporal and frontal areas was seen. The mass also infiltrated the ipsilateral branches of the internal cerebral artery, the middle cerebral artery, and the optic nerve. A provisional squash (cytology) performed intraoperatively from the mass showed lymphocytes, plasma cells, and foreign-body giant cells infiltrating collagenous tissue with numerous fungal filaments. These features were reported to be consistent with a fungal infection. A total excision of the mass was performed, and the mass was subjected to histological and microbiological analysis.

Histology.

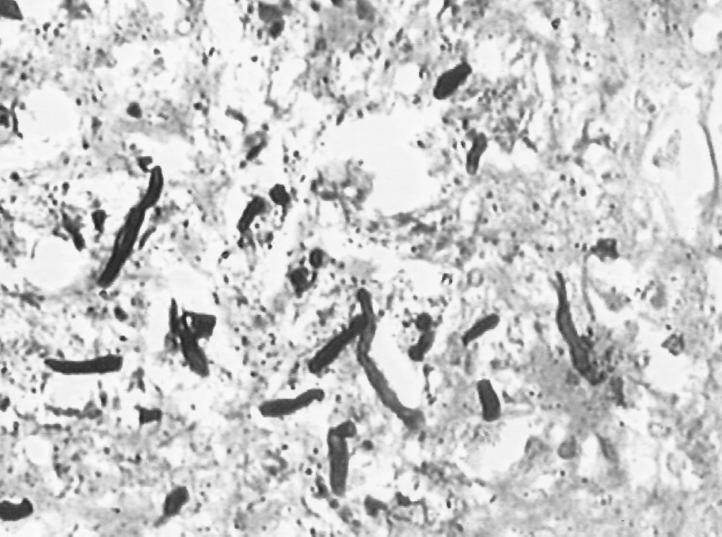

The material submitted for histology consisted of multiple grey-white firm tissue bits with areas of hemorrhages. Multiple sections from the specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed fragments of collagenous tissue infiltrated by lymphocytes and plasma cells along with numerous multinucleate giant cells. There were extensive areas of necrotic foci consisting of thin, short, and irregular fungal filaments distributed sparsely. Native tissue could not be identified. The morphology of these filamentous structures resembled those of Aspergillus hyphae on Gomori methenamine silver stain (Fig. 2). The mass was reported as being suggestive of cerebral aspergillosis. The fungal filaments did not show the presence of melanin pigment in their cell walls.

FIG. 2.

Thin, irregular, short hyphae of Nodulisporium sparsely distributed in tissue. Shown is a section of brain tissue stained with Gomori methenamine silver stain. Magnification, ×350.

Microbiology.

A direct microscopic examination and KOH mount of the tissue revealed septate, dichotomously branching hyphae, and the specimen was interpreted as probably belonging to the genus Aspergillus. The specimen was inoculated onto (i) two slopes of Sabouraud's dextrose agar (SDA) with antimicrobial agents chloramphenicol and cycloheximide; (ii) two slopes of SDA without antimicrobials; and (iii) a slope of brain heart infusion agar (BHI). The SDA slopes were incubated at 28 and 37°C, while the BHI slope was kept at 37°C. Based on the histology and direct microscopy reports, the patient began a regimen of amphotericin B injection. He tolerated the injection well. There were no postoperative complications.

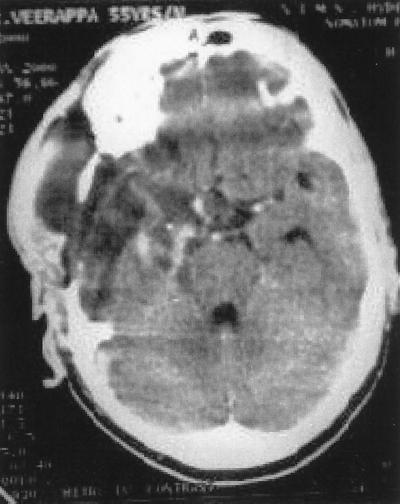

A postoperative CT scan showed only a minute residue of ring enhancement of 1.5 to 2 mm (Fig. 3). At the time of discharge, the patient was experiencing persistent nerve palsy involving the right second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth cranial nerves. The patient was requested to continue following an amphotericin infusion protocol with 50 mg (0.6 mg/kg of body weight/day) of amphotericin B, under a physician's care. A total cumulative dose of amphotericin up to 1.5 to 2.0 g was advised. The patient continues to report to the neurosurgery outpatient clinic for review every 4 weeks and has shown steady improvement in the 1.5 years of follow-up.

FIG. 3.

Postoperative CT scan showing near-total excision of the tumor.

Mycological examination.

After 3 days of incubation, growth of a brown filamentous fungus was observed on all the SDA and BHI slopes.

The morphology of the branching conidiophores with single-cell conidia with acuminate base did not correspond to the genus Aspergillus or any commonly known dematiaceous fungus. For definitive identification of the fungal isolate, we sought the expert assistance of D. Swinne, Head of the Mycology Division, Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium. The isolate was forwarded to H. Beguin at the Scientific Institute of Public Health, IHEM Culture Collection, Brussels, Belgium. After a thorough and meticulous examination, H. Beguin identified the isolate as belonging to the mitosporic genus Nodulisporium.

The fungus was determined to be dematiaceous as it was dark in color.

Cultures grew readily on any of the usual laboratory culture media. On 2% malt agar and oatmeal agar, at 25°C, the fungus covered a 9-cm-diameter plastic petri dish within 1 week. Growth at 37°C was fast, reaching a diameter of 80 mm in 7 days. Growth at 40°C was slow, reaching only 5 mm after 1 week. The culture did not grow at 45°C.

The colony was plane and velutinous, with irregular margins and mycelium subsurface. The conidiogenous areas were scattered over the entire surface of the colony and were pale brownish, near Isabelline (color code, R. 65 [reference 18]). Stromata, exudates, and soluble pigment were absent. The reverse was a deeply colored dark brown, near dark mouse grey (color code, R. 119 [reference 18]).

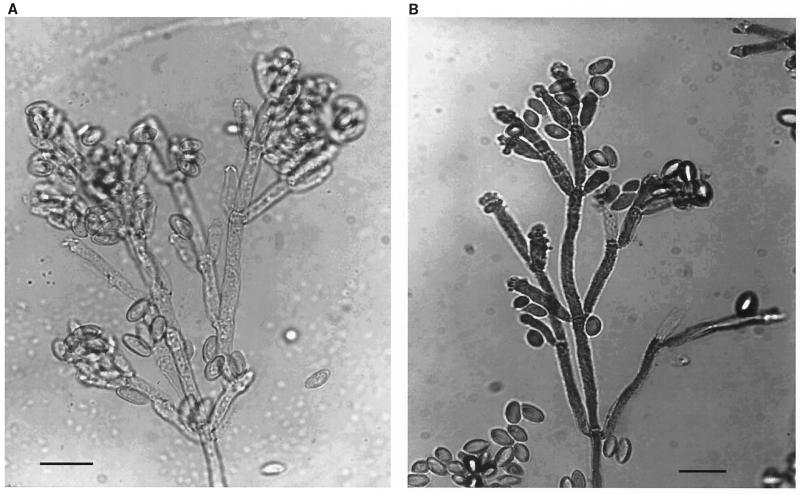

The mycelium was composed of septate hyphae, about 2 to 3 (5.5) μm (extreme value is shown in parentheses) in diameter, and slightly roughened. The conidiophores were erect, mononematous (coindiophores solitary), irregularly branched, flexuous (wavy, not rigid), septate, and becoming mid-brown in the apical part with age. In general the conidiophores were 120 to 200 μm tall, 2.2 to 3.3 μm wide, and smooth, or, like the mycelium, they were slightly roughened and often studded with dark granules. Conidiogenous cells were seen arising, singly or more often in groups, laterally or more frequently at each branch terminus. They were elongate-clavate, mostly 9.0 to 30.0 μm by 2.2 to 3.3 μm, with denticles closely crowded at the tip of the cells that became more or less slightly swollen from repeated conidial production (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Microscopic morphology of Nodulisporium. (A) Unstained wet mount showing the dematiaceous nature of the fungus; (B) Lactophenol cotton blue mount of the fungus showing slightly roughened, erect, irregularly branched conidiophores, with denticles closely crowded at the swollen tips of the conidiogenous cells and conidia. Magnification (both panels), ×300.

Conidia arose singly and successively on denticles at the tips of conidiogenous cells; the first conidium was formed apically. Subsequent conidia were formed sympodially in more or less basipetal succession, forming heads. Conidia were pale brown and smooth, 5.5 to 7.7 μm (12) by 3.3 to 4.4 (5.2) μm, dry, single celled, and ellipsoidal, with a flattened base indicating the former point of attachment to conidiogenous cell. There were no apparent morphological differences in the conidiogenous structures from colonies growing on oatmeal agar (Difco).

The conidium production on areas of the colony surface, the conidiophores, and conidiogenesis were similar to those occurring in many anamorphs of Hypoxylon Bull; more specifically they were similar to those occurring in the genus Nodulisporium.

Discussion.

Among the subdivisions of infections of the central nervous systems (CNS) the two following infections are due to dematiaceous species: (i) rhinocerebral phaeohyphomycosis, a typical secondary infection with airborne conidia which can germinate in the sinus and grow into the brain (the cerebral involvement is typically secondary), and (ii) cerebral phaeohyphomycosis, a primary infection by a fungus located exclusively in brain parenchyma, with the first symptoms being of cerebral origin (14). In the latter case lungs are supposed to be the primary site of infection, from where the fungus spreads via blood to the brain.

The main etiologic agents of infections of the CNS are Cladophialophora bantiana (Sacc) de Hoog et al., Ramichloridium mackenziei Campbell et Al-Hedaithy, Exophiala dermatitidis (Kano) de Hoog, and Ochroconis gallopava (W. B. Cooke) de Hoog (2, 8, 9, 13, 17). Rhinocladiella atrovirens Nannfeldt also has been reported as a neurotropic pathogen (7). Among these agents of phaeohyphomycosis, only the genera Rhinocladiella and Ramichloridium form single-celled conidia by sympodial growth on a pale brown rachis with crowded conidium-bearing denticles like the fungus isolated from the present case. However, the isolated fungus has erect and branched conidiophores whereas these structures are absent or little differentiated from the vegetative hyphae in Rhinocladiella. Conidiophores in Ramichloridium are unbranched. Furthermore, R. mackenziei is limited to the Middle East (14).

Among the genera with acropleurogenous conidia are also Geniculosporium Chesters et Greenhalgh, Dicyma Boulanger, Dematophora Hartig, and Nodulisporium Preuss (11). The genus Geniculosporium has conidiogenous cells, usually with a long geniculate rachis. In 1981, von Arx (23) transferred Hansfordia Hughes, Basifimbria Subramanian et Lodha, Gonytrichella Emotto et Tubaki, and Puciola de Bertoli to the genus Dicyma, which has been redescribed as having smooth branched conidiophores, often partly forming septae, whip-like hyphae or cylindrical-clavate, ampulliform cells (24). Dematophora, like Geniculosporium, has sympodulosporous conidia but forms conidia in two rows in the apical fertile parts and synnemata in nature, unlike in cultures (25). Finally, the form genus Nodulisporium that has swollen conidiogenous areas (conidiogenous cells denticulate, cylindrical to clavate) corresponds to the isolated strain. Moreover, branching patterns of conidiogenous structures, i.e., profusely branched conidiophores and the tendency to produce more than two conidiogenous cells at each branch terminus, are also referable to Nodulisporium (15).

Nodulisporium was erected on the basis of two moniliaceous species: Nodulisporium album Preuss and Nodulisporium ochraceum Preuss. Subramanian restricted Nodulisporium to pale colored species and placed the dematiaceous species in the genus Acrostaphylus Arnaud ex Subramanian (22). Greenhalgh and Chesters (12) do not accept this division, based on pigmentation. Indeed, many members of the Xylariaceae family are hyaline at first and colored later on with age. Regardless of this, Subramanian from India related two Acrostaphylus species: Acrostaphylus hyperparasiticus Subram, with globose conidia, and Acrostaphylus lignicola Subram, with conidia oval to elliptical up to 7 μm long (22). These two taxa do not correspond to the present isolate. Later, two other species, also originating from India, were described as Nodulisporium: Nodulisporium indicum Reddy et Bilgrami (only related two Acrostaphylus species represented by the type culture isolated in 1967 from Mangifera indica, but this culture shows many chlamydospores and arthroconidia, absent in the case strain) and Nodulisporium griseobrunneum Mehrotra (isolated from soil in a Piper betel orchard). The latter species only differs from the present isolate in having slightly larger (6.6 to 13 μm by 3.5 to 5.5 μm) conidia; but the ability to grow at 37°C, the growth rate, the colony color, and the conidiophore morphology closely resemble those of N. griseobrunneum.

The fact that this strain isolated from brain tissues grows very rapidly at 37°C is not a common occurrence. This characteristic should not be ignored or overlooked in the protolog of the name of a species. The literature only refers to N. cylindroconium de Hoog (4), of which the type culture had been isolated as Tritirachium species by Evans (10, 11) as a strong thermotolerant species with an optimal growing temperature at 40°C (growth to a diameter of 35 mm within 10 days on malt agar) (14). The other members of the genus Nodulisporium also differ distinctly by the size of the conidia (mostly smaller), by the branching habit, and by the appearance of the colonies (4, 5, 6, 10, 19, 20, 21, 26).

Nodulisporium is an anamorph also associated in nature with many ascomycete species of the Xylariaceae family, especially Hypoxylon. Ju and Rogers (16) even consider this anamorph as a primary criterion for recognizing a xylariaceous fungus as a member of the genus Hypoxylon. Among these ascomycetes, some produce conidia on areas of the entire surface of the colony. This feature occurs in the strain isolated in the present study and it is more characteristic in the Hypoxylon species (1). A few members of this genus are strictly host limited on various trees; others are found on dead branches or fallen trunks and logs, often accompanied or preceded by a Nodulisporium state. Following the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (article 59), the legitimate name of a holomorphic species can be typified by only its teleomorph, i.e., the morph characterized by ascospores in ascomycetous fungi (12a). This situation is particularly true in xylariaceous fungi for which dual nomenclature exists, although not used often, and species are mostly described only under the ascomycetous name. Indeed the Nodulisporium state frequently disappears early in the process of stromal development (12). This implies that most keys are based on teleomorph features only, the anamorphic state being ignored or little described—as “a Nodulisporium-like anamorph,” as “a typical Nodulisporium,” or as referable to this genus by the use of “Nodulisporium state of ….” In culture, ascigerous stromata are absent, but some of these ascomycetes produce conidia, and then the identification of a Xylariaceae anamorph should be compared with the asexual states that originated from identified teleomorphic material.

The identification of this anamorphic isolate to the species level remains problematic in spite of its unusual rapid growth at 37°C, which is an uncommon characteristic.

The brain abscess was the only conspicuous pathology in this case report. There were no sinusitis, no underlying disease prior to the infection, and no lesion outside the CNS. The portal of entry of infection has thus not been identified. Per H. Beguin, this is the first case of cerebral infection by Nodulisporium and the second case involving this fungal taxon in human disease. Also, Nodulisporium is for the first time being described here as a pathogenic agent of human infection. Cox et al. reported the first case of an allergic fungal sinusitis by the presence of a persistent Nodulisporium species in mucus in 1994 (3). However, there was no tissue invasion by the fungus in their study.

Our isolate is preserved at the BCCM/IHEM Culture Collection (IHEM 16563).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the interest and efforts taken by H. Beguin in identifying the fungal isolate and providing the relevant literature.

REFERENCES

- 1.Callan B E, Rogers J D. A synoptic key to Xylaria species from continental United States and Canada based on cultural and anamorphic features. Mycotaxon. 1993;46:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell C K, Al-Hedaithy Phaeohyphomycosis of the brain caused by Ramichloridium mackenziei sp. nov. in Middle Eastern countries. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox G M, Schell W A, Scher R L, Perfect J R. First report of involvement of Nodulisporium species in human disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2301–2304. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2301-2304.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Hoog G S. Additional notes on Tritirachium. Persoonia. 1973;7:437–441. [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Hoog G S. The genera Blastobotrys, Sporothrix, Calcarisporium and Calcarisporiella genus. Studies Mycol. 1974;7:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deighton F C. Some species of Nodulisporium. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1985;85:391–395. [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Palacio-Hernanz A, Moore M K, Campbell C K, et al. Infection of the central nervous system by Rhinocladiella atrovirens in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Med Vet Mycol. 1989;27:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon D M, Salkin I. Morphologic and physiologic studies of three dematiaceous pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:12–15. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.1.12-15.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon D M, Walsh T J, Merz W G, McGinnis M R. Infections due to Xylohypha bantiana (Cladosporium trichoides). Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:515–525. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans H C. Thermophilous fungi of coal spoil tips. I. Taxonomy. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1971;57:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans H C. Thermophilous fungi of coal spoil tips. II. Occurrence, distribution and temperature relationships. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1971;57:255–266. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh G N, Chesters C G C. Conidiophore morphology in some British members of the Xylariaceae. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1968;51:57–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Greuter W, editor. International code of botanical nomenclature (Tokyo code), adopted by the Fifteenth International Botanical Congress, Yokohama, August–September 1993. Königstein, Germany: Koeltz Scientific Books; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiruma M, Kawada A, Ohata H, Ohnishi Y, Takahashi H, Yamazaki M, Ishibashi A, Hatsuse K, Kakihare M, Yoshida M. Systemic phaeohyphomycoses caused by Exophiala dermatitidis. Mycoses. 1993;36:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1993.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horré R, de Hoog G S. Primary cerebral infections by melanized fungi: a review. Studies Mycol. 1999;43:176–193. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jong S C, Rogers J D. Illustrations and descriptions of conidial states of some Hypoxylon species. Washington State Agriculture Experiment Station bulletin 71. Agriculture Experiment Station, Pullman: Washington State; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ju Y-M, Rogers J D. A revision of the genus Hypoxylon. St. Paul, Minn: APS Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGinnis M R, Rinaldi M G, Winn R E. Emerging agents of phaeohyphomycosis: pathogenic species of Bipolaris and Exserohilum. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:250–259. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.2.250-259.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rayner R W. A mycological colour chart. Kew, United Kingdom: Commonwealth Mycological Institute and British Mycological Society; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith G. Some new species of moulds and some new British records. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1951;34:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith G. Two new combinations. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1954;37:166–167. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith G. Some new and interesting species of micro-fungi. III. Trans Br Mycol Soc. 1962;45:387–394. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian C V. Hyphomycetes. II. J Indian Bot Soc. 1956;35:446–494. [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Arx J A. The genera of fungi sporulating in pure culture. Vaduz, Liechtenstein: J. Cramer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Arx J A. The genus Dicyma, its synonyms and related fungi. Proc K Ned Akad Wet. 1982;85:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe T. Pictorial atlas of soil and seed fungi. New York, N.Y: CRC Press, Lewis Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watanabe T, Sato M. Root rot of melon caused by Nodulisporium melonis in Japan and identification. Ann Phytopathol Soc Jpn. 1995;61:330–333. [Google Scholar]