Abstract

Context

Little is known about provider specialties involved in thyroid cancer diagnosis and management.

Objective

Characterize providers involved in diagnosing and treating thyroid cancer.

Design/Setting/Participants

We surveyed patients with differentiated thyroid cancer from the Georgia and Los Angeles County Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries (N = 2632, 63% response rate). Patients identified their primary care physicians (PCPs), who were also surveyed (N = 162, 56% response rate).

Main outcome measures

(1) Patient-reported provider involvement (endocrinologist, surgeon, PCP) at diagnosis and treatment; (2) PCP-reported involvement (more vs less) and comfort (more vs less) with discussing diagnosis and treatment.

Results

Among thyroid cancer patients, 40.6% reported being informed of their diagnosis by their surgeon, 37.9% by their endocrinologist, and 13.5% by their PCP. Patients reported discussing their treatment with their surgeon (71.7%), endocrinologist (69.6%), and PCP (33.3%). Physician specialty involvement in diagnosis and treatment varied by patient race/ethnicity and age. For example, Hispanic patients (vs non-Hispanic White) were more likely to report their PCP informed them of their diagnosis (odds ratio [OR]: 1.68; 95% CI, 1.24-2.27). Patients ≥65 years (vs <45 years) were more likely to discuss treatment with their PCP (OR: 1.59; 95% CI, 1.22-2.08). Although 74% of PCPs reported discussing their patients’ diagnosis and 62% their treatment, only 66% and 48%, respectively, were comfortable doing so.

Conclusions

PCPs were involved in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment, and their involvement was greater among older patients and patients of minority race/ethnicity. This suggests an opportunity to leverage PCP involvement in thyroid cancer management to improve health and quality of care outcomes for vulnerable patients.

Keywords: thyroid neoplasms, healthcare disparities, physicians, primary care, surgeons, endocrinologists

An estimated 44 280 patients will be diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2021 (1); the majority of these new cancers will be differentiated thyroid cancer. Although in general, morbidity and mortality from differentiated thyroid cancer is low, prior research has shown that significant disparities in patterns of thyroid cancer care do exist leading to poor health and quality-of-care outcomes (2). For example, Harari et al. found that a higher percentage of Black, Hispanic, and Asian-Pacific Islander patients presented with metastatic disease compared with White patients (3). Additional studies have found that Black and Hispanic patients were more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons than White patients and that Black patients had longer mean length of hospital stay and higher in-hospital mortality than White patients (4).

Understanding the factors that can help mitigate these disparities will be critical to the development of interventions to improve outcomes. Examining the various providers involved at the time of patients’ diagnosis and treatment decision making for their thyroid cancer may present opportunity for improvement. Patients have previously noted the importance of trust in their physician and the physician’s management recommendations in their treatment decision making (5, 6). Prior work has also found that pathways to a thyroid cancer diagnosis (eg, nodule discovery with imaging vs palpation) can differ (7). However, there is little work evaluating the specialty of the provider involved in discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment. In the growing context of team-based cancer care delivery (8, 9), where national organizations are calling for cancer specialists and primary care physicians (PCPs) to provide coordinated cancer care, recognizing and understanding the role of PCPs in thyroid cancer management is increasingly important. PCP involvement in treatment decision making for other cancers such as breast and prostate has already been reported. One-third of PCPs reported involvement in the surgical treatment decisions for their patients with early-stage breast cancer (10). In a survey of men with localized prostate cancer, 38% reported their PCP helped them decide how to treat their cancer (11). Notably, non-Hispanic Black men were more likely to report receiving help from their PCP compared with White men.

Despite this evidence in other cancers, little is known about PCP involvement in the context of thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment. Yet, understanding and potentially leveraging the role of the PCP in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment may be important for improving health and quality-of-care outcomes. Therefore, we surveyed a population-based cohort of patients with thyroid cancer to identify the providers involved in their care, and then followed with a survey of their PCPs to describe complementary perspectives from the physicians on their involvement in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

Study Population

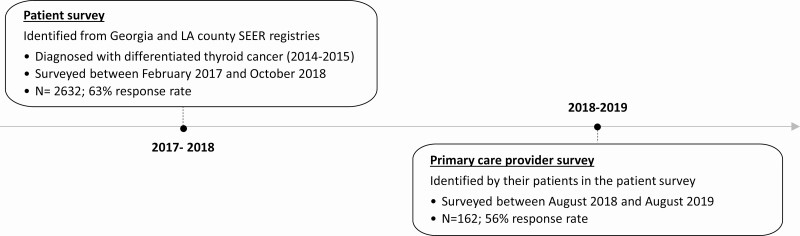

Our study population includes both patients with thyroid cancer and the PCPs involved in their care (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient and PCP cohort selection.

Patients

We used the Georgia and Los Angeles County Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results registries to identify a large, diverse cohort of patients newly diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer between January 2014 and December 2015. Patients were surveyed between February 2017 and October 2018 (N = 4317). Patients were excluded if they reported not having thyroid cancer, were incarcerated, were deceased, or did not meet study screening criteria after initial contact (N = 132).

Primary care physicians

In the patient survey, we asked patients to identify an “other doctor most involved in your thyroid cancer treatment decision making (other than your surgeon or endocrinologist).” All PCPs identified by patients were surveyed between August 2018 and August 2019 (N = 289). PCPs were excluded if they reported being retired, could not be located, were deceased, or did not meet study criteria after initial contact (N = 15).

To improve response rates for the patient and PCP surveys, we used a modified Dillman method (12). This consisted of an initial mailing of a packet including a cover letter and survey, an unconditional cash incentive ($20 for patients, $50 for PCPs), follow-up phone calls to nonresponders, and an additional mailing to nonresponders. Our final analytic sample included 2632 patients (63% response rate) and 162 PCPs (response rate 56%).

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Michigan, University of Southern California, Emory University, the California Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, the California Cancer Registry, and the Georgia Department of Public Health.

Measures

Patient and PCP surveys were developed based on a conceptual framework, research questions and hypotheses, systematic reviews of current literature, and our prior work (13-16). We used standard techniques to assess content validity including reviews by design and content experts, and piloting testing with patients and PCPs at the University of Michigan.

Patient Report of Provider Involvement in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

To determine which provider informed the patient about their thyroid cancer diagnosis, patient respondents were asked: “Thinking back to the time of diagnosis, which doctor told you that you had thyroid cancer?” Options included: PCP, obstetrician/gynecologist, surgeon, endocrinologist, oncologist, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, other, or “I don’t know.” Similarly, to determine the providers with whom patients discussed their thyroid cancer treatment, respondents were asked, “When you were diagnosed with thyroid cancer, who did you talk to about your treatment decisions?” Options included: PCP, surgeon, endocrinologist, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, nuclear medicine doctor, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, or other.

PCP Report of Involvement in Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment

To determine PCP involvement, PCP respondents were asked: “Of the patients you have with recently diagnosed thyroid cancer, how often did you: (1) discuss their thyroid cancer diagnosis and (2) discuss their thyroid cancer treatment.” Responses were on a 5-point Likert-type scale (“never” to “always”) and dichotomized to more involved (“often,” “always”) vs less involved (“never,” “rarely,” “sometimes”). PCPs were also asked how comfortable they were discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment with their newly diagnosed thyroid cancer patients. Responses were on a 5-point Likert type scale from “not at all” to “extremely” and dichotomized to more comfortable (“quite,” “extremely”) vs less comfortable (“not at all,” “a little,” “somewhat”). We chose these cutoffs given the distribution of our responses and to identify PCPs who reported being “less involved” or “less comfortable,” which can serve as potential targets for intervention.

Covariates

Patient-reported characteristics collected via survey included: age, sex, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Black, non-Hispanic White, Asian, Other), household income (≤$49 000, >$49 000), education (high school graduate or below, some college, college graduate and above), and health insurance (private, other).

PCP-reported characteristics collected via survey included: specialty (general medicine, family medicine), gender, race/ethnicity (Hispanic, Black, non-Hispanic White, Asian, Other), years in practice (<10 years, 10-19 years, 20-29 years, >30 years), practice setting (large medical group or staff-model health maintenance organization/academic medical center, private practice/community health clinic), number of patients during a typical week seen in their primary practice location (≤75 patients, 76-100 patients, >100 patients). Respondent PCPs were also asked to report which source was the most influential in their decisions on how to treat thyroid nodule and thyroid cancer patients (training in medical school/residency, recently published clinical guidelines, practice colleagues, employer-published treatment guidelines, national meetings, respected experts in my field, or journal articles) and which clinical guidelines they had read (“2015 American Thyroid Association [ATA] Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer,” National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s [NCCN] 2017 “Thyroid Carcinoma: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology,” or none; answers were combined as reading either guideline vs none).

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize patient and PCP characteristics.

Patients

First, we described patient report of which provider informed them about their thyroid cancer diagnosis and with which provider they discussed their treatment decisions. For the remainder of the analyses, we focused on the providers most reported by patients, including endocrinologist, surgeon, and PCP. Second, using bivariate (Rao-Scott χ 2 tests) followed by multivariable (logistic regression) analyses, we examined associations between patient characteristics and the type of provider (endocrinologist, surgeon, PCP) involved in informing the patient about the diagnosis. Third, we repeated these analyses with the outcome as the type of provider with whom the patient discussed treatment decisions (endocrinologist, surgeon, PCP). Models were run separately for each provider type.

PCPs

First, we described PCP reports of how often they discussed thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment with their patients and how comfortable they were doing so. Second, using bivariate (Rao-Scott χ 2 tests) followed by multivariable (logistic regression) analyses, we examined associations between PCP characteristics and extent of PCP involvement in discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis and comfort in discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis. Third, we repeated these analyses to examine PCP involvement in discussing thyroid cancer treatment and comfort with discussing thyroid cancer treatment.

We found differences in race, ethnicity, age, and stage of disease between responders and nonresponders. For example, higher nonresponse rates were seen among Other, Asian, Black, and Hispanic patients as well as younger (<45 years) patients. As such, we incorporated weights in our analyses to account for our sampling strategy and reduce potential nonresponse bias. Weights included both physician and patient nonresponse weights. All analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

Patients

Table 1 describes our respondent patient characteristics. On average, patients were 50 years old, and the majority were female (77.8%) and had private insurance (68.4%). Although the majority of patients identified as non-Hispanic White (56.7%), 20.1% identified as Hispanic, 11.2% as Black, and 9.4% as Asian. Patients reported that they were informed they had thyroid cancer by their surgeon (40.6%), endocrinologist (37.9%), and PCP (13.5%). Similarly, patients reported they discussed their treatment decisions for their thyroid cancer with their surgeon (71.7%), endocrinologist (69.6%), and PCP (33.3%). The majority of patients reported they were informed of their thyroid cancer diagnosis by only 1 provider (91%). In contrast, 73% of patients reported they discussed their treatment decisions with more than 1 provider. Most frequently, patients reported they discussed treatment with their surgeon and endocrinologist (50.0%), PCP and surgeon (27.1%), and PCP and endocrinologist (22.4%). The proportion of patients who discussed their treatment decisions with their PCP was similar in patients with localized, regional, and distant disease (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 2632)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| < 45 | 905 (37.6) |

| 45-54 | 634 (23.2) |

| 55-64 | 615 (22.0) |

| ≥ 65 | 478 (17.2) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 2038 (77.8) |

| Male | 594 (22.2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1480 (56.7%) |

| Hispanic | 525 (20.1%) |

| Black | 292 (11.2%) |

| Asian | 244 (9.4%) |

| Othera | 69 (2.6%) |

| Household income | |

| ≤ $49 000 | 786 (30.8) |

| > $49000 | 1450 (53.7) |

| Unknown | 396 (15.5) |

| Education | |

| High school and below | 640 (24.9) |

| Some college | 754 (29.4) |

| College degree and above | 1192 (45.7) |

| Health insurance | |

| Private | 1760 (68.4) |

| Other | 798 (31.6) |

a Other includes multiracial, other, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaskan native.

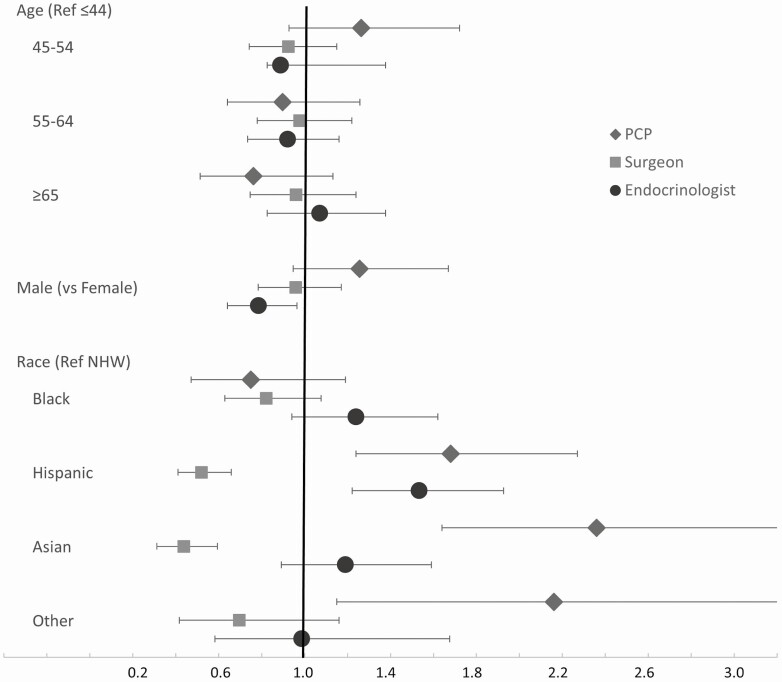

In bivariate analyses examining associations between patient characteristics and the specialty of the provider informing the patient about their diagnosis, we observed differences based on race/ethnicity and education (results not shown). Figure 2 shows results from multivariable regression models, where similar associations were observed. Compared with non-Hispanic White patients, Hispanic patients were more likely to report that their PCP (odds ratio [OR] 1.68; 95% CI, 1.24-2.27) and endocrinologist (OR 1.53; 95% CI, 1.22-1.93) informed them they had thyroid cancer and less likely to report that their surgeon informed them (OR 0.52; 95% CI, 0.41-0.66). Compared with non-Hispanic White patients, Asian and Other patients similarly were also more likely to report their PCP informed them they had thyroid cancer (OR 2.36; 95% CI, 1.64-3.42; and OR 2.16; 95% CI, 1.15-4.06, respectively). Asian patients (vs non-Hispanic White) were less likely to report their surgeon informed them they had thyroid cancer (OR 0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.60).

Figure 2.

Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs of patient characteristics associated with type of provider (primary care provider, surgeon, or endocrinologist) who informed the patient about the thyroid cancer diagnosis.

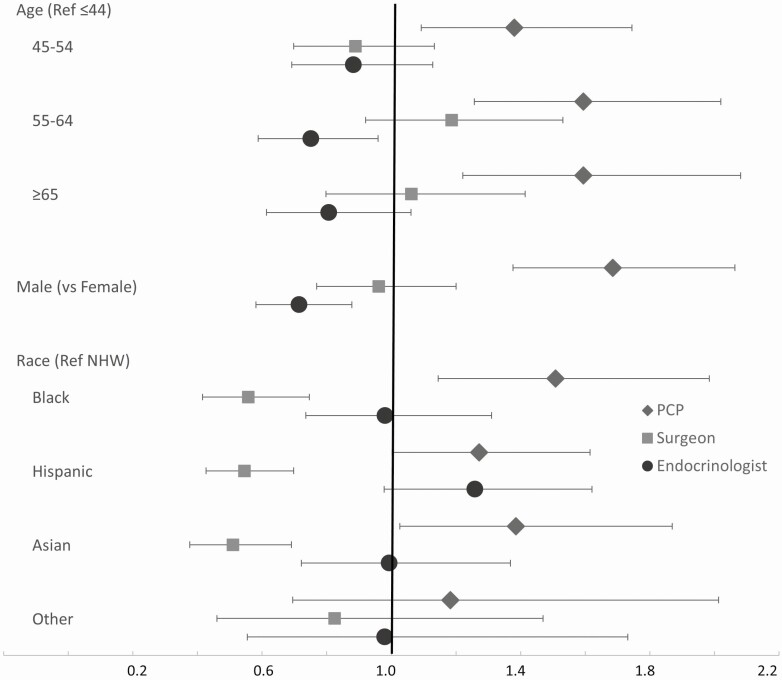

Results from bivariate analyses examining associations between patient characteristics and the type of provider with whom the patient reported discussing their treatment decisions showed differences based on age and race/ethnicity (results not shown). Figure 3 shows results from multivariable regression models, where similar associations were observed. Compared with patients <45 years, patients 45 to 54 years (OR 1.38; 95% CI, 1.09-1.75), 55 to 64 years (OR 1.59; 95% CI, 1.26-2.02), and ≥65 years (OR 1.59; 95% CI, 1.22-2.08) were all more likely to report discussing treatment with their PCP. Male (OR 1.69; 95% CI, 1.38-2.06 vs female), Black (OR 1.51; 95% CI, 1.15-1.98 vs non-Hispanic White) and Asian (OR 1.39; 95% CI, 1.03-1.87 vs non-Hispanic White) patients were also more likely to report discussing treatment with their PCP. Black (OR 0.56; 95% CI, 0.42-0.75), Hispanic (OR 0.55; 95% CI, 0.43-0.70), and Asian (OR 0.51; 95% CI, 0.38-0.69) patients (vs non-Hispanic White) were all less likely to report discussing their treatment with their surgeons.

Figure 3.

Multivariable-adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs of patient characteristics associated with type of provider (primary care provider, surgeon, or endocrinologist) with whom patient discussed treatment.

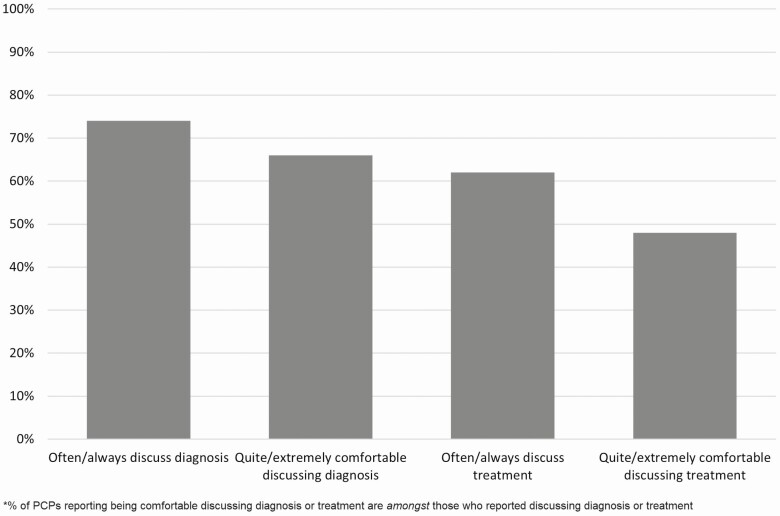

PCPs

Table 2 describes our respondent PCP characteristics. Respondents were split nearly equally between general medicine (47.4%) and family medicine (52.6%) specialties. The majority were non-Hispanic White (64.1%), in either private practice or community health clinics (69.3%), and were in clinical practice for ≥20 years (56.3%). Nearly 75% of PCPs reported discussing their patient’s thyroid cancer diagnosis, and among those, 66% reported being comfortable doing so. About 62% of PCPs reported discussing their patient’s thyroid cancer treatment, and among those, 48% reported being comfortable doing so (Fig. 4).

Table 2.

PCP characteristics (N = 162)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | |

| General medicine | 72 (47.4) |

| Family medicine | 79 (52.6) |

| Practice setting | |

| Private practice/community health clinic | 103 (69.3) |

| Large medical group or staff-model HMO/academic medical center | 47 (30.7) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 74 (47.1) |

| Male | 84 (52.9) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 100 (64.1) |

| Hispanic | 12 (7.1) |

| Black | 11 (7.1) |

| Asian | 30 (19.2) |

| Othera | 3 (1.9) |

| Years in practice | |

| 1-9 | 25 (15.8) |

| 10-19 | 44 (27.9) |

| 20-29 | 55 (35.3) |

| ≥ 30 | 34 (21.0) |

| Number of patients (typical week) | |

| ≤ 75 | 52 (32.9) |

| 76-100 | 63 (39.6) |

| > 100 | 44 (27.5) |

| Clinical guidelines read | |

| ATA and/or NCCN | 44 (27.9) |

| None | 111 (72.1) |

| Most influential in treating thyroid cancer (top 2) | |

| Clinical guidelines | 88 (54.4) |

| Colleagues in practice | 64 (39.1) |

Abbreviations: ATA, American Thyroid Association; HMO, health maintenance organization; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

a Other includes multiracial, other, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaskan native.

Figure 4.

Distribution of PCP-report of involvement in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment.

In bivariate analyses examining associations between PCP characteristics and PCP involvement in discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis and comfort in discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis, differences were seen based on specialty and clinical guidelines read (results not shown). In multivariable analyses, results remained similar (Table 3). General medicine physicians (vs family medicine) were more comfortable discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis (OR 2.70; 95% CI, 1.15-6.35), and PCPs who did not read ATA and/or NCCN guidelines (vs those who did) were less likely to be comfortable (OR 0.31; 95% CI, 0.12-0.78) discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis. Bivariate (results not shown) and multivariable analyses (Table 3) examining associations between PCP characteristics and PCP involvement in discussing thyroid cancer treatment and comfort in discussing thyroid cancer treatment showed similar patterns.

Table 3.

Multivariable associations between PCP characteristics and discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis; comfort with discussing thyroid cancer diagnosis; discussing thyroid cancer treatment; and comfort with discussing thyroid cancer treatment

| Discusses diagnosis | Comfortable discussing diagnosis | Discusses treatment | Comfortable discussing treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||||

| General medicine | 2.39 (0.74-7.78) | 2.70 (1.15-6.35) | 1.76 (0.67-4.58) | 2.54 (1.06-6.10) |

| Family medicine | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Private practice/community health clinic | 2.59 (0.98-6.86) | 1.80 (0.72-4.51) | 2.27 (0.90-5.75) | 2.47 (0.78-7.84) |

| Large medical group or staff-model HMO/academic medical center | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1.09 (0.37-3.20) | 0.52 (0.21-1.25) | 0.61 (0.23-1.66) | 0.53 (0.19-1.44) |

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Hispanic | 2.19 (0.38-12.50) | 1.50 (0.40-5.55) | 6.75 (1.24-36.88) | 1.87 (0.32-11.04) |

| Black | 1.92 (0.24-15.35) | 0.53 (0.14-1.90) | 2.54 (0.41-15.62) | 0.78 (0.20-3.09) |

| Asian | 1.12 (0.35-3.55) | 1.53 (0.58-4.06) | 1.09 (0.40-2.97) | 1.25 (0.37-4.16) |

| Other | - | 1.69 (0.08-36.08) | 0.47 (0.15-14.63) | 3.63 (0.28-47.95) |

| Years in practice | ||||

| 1-9 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 10-19 | 2.12 (0.50-9.01) | 1.14 (0.30-4.34) | 0.96 (0.25-3.62) | 1.26 (0.21-7.51) |

| 20-29 | 1.52 (0.32-7.34) | 1.12 (0.31-4.02) | 1.52 (0.41-5.63) | 3.64 (0.82-16.10) |

| ≥ 30 | 0.99 (0.18-5.56) | 1.23 (0.26-5.93) | 0.87 (0.18-4.09) | 4.34 (0.75-25.03) |

| Number of patients (typical week) | ||||

| ≤ 75 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 76-100 | 2.26 (0.75-6.79) | 2.52 (0.99-6.45) | 1.51 (0.54-4.17) | 3.39 (1.05-10.94) |

| > 100 | 1.53 (0.50-4.71) | 2.95 (1.00-8.71) | 0.89 (0.30-2.59) | 2.41 (0.64-9.07) |

| Guidelines read | ||||

| ATA and/or NCCN | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| None | 0.46 (0.13-1.63) | 0.31 (0.12-0.78) | 0.27 (0.09-0.83) | 0.19 (0.06-0.57) |

| Most influential in thyroid cancer treatments (top 2) | ||||

| Clinical guidelines | ||||

| Yes | 7.45 (2.36-23.49) | 1.46 (0.61-3.51) | 4.33 (1.69-11.13) | 2.41 (0.91-6.40) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Colleagues in practice | ||||

| Yes | 2.37 (0.71-7.86) | 0.86 (0.35-2.09) | 1.78 (0.67-4.72) | 0.81 (0.27-2.36) |

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

Bold represents statistically significant ORs at P < .05.

Abbreviations: ATA, American Thyroid Association; HMO, health maintenance organization; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Discussion

Our study presents data from a population-based cohort of patients with thyroid cancer and the PCPs who participated in their care to illustrate the current landscape of the physicians involved in the diagnosis and treatment of thyroid cancer. Although endocrinologist and surgeon involvement in thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment was most reported by patients, patients and PCPs did report PCP involvement in both informing patients of their diagnosis and in the treatment decision making for thyroid cancer. Importantly, certain vulnerable populations of patients, including those who are Hispanic, Black, Asian, Other, and older, were more likely to report PCP involvement. Leveraging the involvement of PCPs in thyroid cancer management may present an opportunity to address disparities in these groups, and ultimately improving health and quality-of-care outcomes for vulnerable patients.

Most patients reported they were told of their thyroid cancer diagnosis by their surgeon or endocrinologist, but 13.5% reported they were told by their PCP. It is notable that Hispanic and Asian patients were more likely to report that their PCP informed them of their diagnosis, and less likely to report their surgeon did so. Prior research shows that compared with White patients, non-White patients (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Asian) are more likely to present with larger tumor size at diagnosis (3, 17). Some of this is thought to be related to access to care. Lim and colleagues found that in a large public hospital (compared with the local university hospital), the majority of patients were ethnic minorities and only 2% had insurance (18). The patients at the public hospital were more likely to have advanced stage tumors. Key to informing patients of their diagnosis is to then ensure that patients are appropriately referred to specialists and receive timely treatment. In fact, the Endocrine Society, in a scientific statement, noted that access for minority patients to “high-volume surgeons” and to “centers with appropriate endocrine and surgical expertise” are needed to reduce health disparities (19). One potential solution may be the creation of standardized cancer care pathways, similar to programs in the United Kingdom (20, 21), which would allow for a PCP to refer patients with suspected thyroid cancer for timely diagnosis and treatment. Such a system could be especially beneficial for vulnerable patients, who could be appropriately referred to specialists, such as high-volume surgeons.

One-third of patients reported discussing their treatment of thyroid cancer with their PCPs, which is in line with prior research for patients with breast and prostate cancer (10, 11). This was especially the case for older, Black, and Asian patients. Prior research has shown that Black race was associated with lower overall survival rates for patients with differentiated thyroid cancer (3, 22). Several other studies have shown racial disparities in treatment outcomes, such as higher overall complication rates after thyroidectomy for Black patients, and Black patients being less likely to receive radioactive iodine (23-26). In part, these disparities may reflect patient distrust of physicians (which affects which physician the patient seeks for treatment) and poor communication between physicians and patients (which may affect patient understanding of his or her thyroid cancer and treatment recommendations). PCPs often have longstanding and trusting relationships with their patients, and help patients navigate their chronic diseases. An important aspect of PCP visits involves reviewing specialist visits and ensuring patients understand their disease. This presents an opportunity for capitalizing upon the PCP visit to improve outcomes for patients with thyroid cancer. For their patients with thyroid cancer undergoing treatment, PCPs could offer patient-directed educational materials (such as those from the ATA (27) and the Endocrine Society (28)) and review and reinforce what the endocrinologist or surgeon discussed during the patient’s visit to promote trust in the specialist’s recommendations.

Although we found the majority of PCPs in our sample reported both discussing their patient’s thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment, there remained a substantial portion who reported not being comfortable having these discussions. There were differences noted based on specialty, and whether PCPs had read the NCCN and ATA guidelines. This is similar to our prior finding of PCP role in thyroid cancer survivorship (29). Although PCPs reported being involved, fewer than one-half reported having high levels of confidence in providing survivorship care. There was also variation based on whether PCPs had read either the NCCN or ATA guidelines. As we expand team-based cancer care delivery, increasing familiarity of PCPs to thyroid cancer management, from diagnosis through treatment to survivorship, will be critical to its success. This can be accomplished in several ways. PCPs can be offered educational training, through Continuing Medical Education credits such as journal clubs or conferences such as grand rounds, which specifically discuss the PCP’s role and responsibility in managing their patients with thyroid cancer. In previous studies, PCPs have often noted the lack of communication from cancer specialists that limit their ability to be effectively involved in their patient’s care (30). Therefore, increasing outreach from endocrinologists and surgeons to PCPs (e.g., sending clinic notes where the specialist delineates treatment options and why 1 option may benefit the specific patient) will be important. Last, as has been done for cancer survivorship for other cancer types, disseminating thyroid cancer guidelines from the ATA or NCCN for PCPs specifically may be helpful. For example, the American Cancer Society’s guidelines for breast cancer survivorship care include recommendations to PCPs on surveillance (such as frequency of mammograms), genetic counseling (which patient should be referred), and endocrine treatments (encouraging adherence) (31). The ATA could similarly provide recommendations specific for PCPs.

Strengths of this study include the diverse, population-based patient cohort and the inclusion of PCPs who were identified by these patients. Additional strengths include the rigorous survey methodology and high response rates. Limitations include the possibility of recall bias. In addition, the perception of “discussed” may differ between patients and physicians. For example, most of these patients underwent surgery; therefore, the surgeons may feel they “discussed” treatment. However, because this patient-reported percentage was <100%, it is possible that patients perceive “a discussion” differently, potentially with more back-and-forth communication.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, our results are the first to characterize the provider specialties involved at the time of a patient’s thyroid cancer diagnosis and treatment decision making, and, specifically, the role of the PCP. With notable disparities in thyroid management for vulnerable patients such as racial and ethnic minorities and those who are older, it is critical to understand factors leading to these disparities and then design the appropriate interventions to improve them. Leveraging the team of providers—including the PCP—involved in the patient’s thyroid cancer care presents a promising opportunity. For vulnerable patients in particular, who are at risk of poor health and quality-of-care outcomes for their thyroid cancer, having an informed and involved PCP may be key to improving outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work is supported by R01 CA201198 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to M.R.H. M.R.H. is also supported by R01 HS024512 from AHRQ. A.R. is supported by K08 CA245237. The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under Cooperative Agreement No. 5NU58DP003862-04/DP003862; and the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract no. HHSN261201000035C awarded to the University of Southern California. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and endorsement by the State of California Department of Public Health, the NCI, and the CDC or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended nor should be inferred.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ATA

American Thyroid Association

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- OR

odds ratio

- PCP

primary care physician

Additional Information

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for thyroid cancer 2021. ProMED-mail website. Accessed April 2, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/thyroid-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- 2. Chen DW, Haymart MR. Disparities research in thyroid cancer: challenges and strategies for improvement. Thyroid. 2020;30(9):1231-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harari A, Li N, Yeh MW. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in presentation and outcomes of well-differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(1):133-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sosa JA, Mehta PJ, Wang TS, Yeo HL, Roman SA. Racial disparities in clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;246(6):1083-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. D’Agostino TA, Shuk E, Maloney EK, Zeuren R, Tuttle RM, Bylund CL. Treatment decision making in early-stage papillary thyroid cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):61-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sawka AM, Ghai S, Yoannidis T, et al. A prospective mixed-methods study of decision-making on surgery or active surveillance for low-risk papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2020;30(7):999-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Esfandiari NH, Hughes DT, Reyes-Gastelum D, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, Haymart MR. Factors associated with diagnosis and treatment of thyroid microcarcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(12):6060-6068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kosty MP, Hanley A, Chollette V, Bruinooge SS, Taplin SH. National Cancer Institute-American Society of Clinical Oncology Teams in cancer care project. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(11):955-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wallner LP, Li Y, McLeod MC, et al. Primary care provider-reported involvement in breast cancer treatment decisions. Cancer. 2019;125(11):1815-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Radhakrishnan A, Grande D, Ross M, et al. When primary care providers (PCPs) help patients choose prostate cancer treatment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(3):298-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM.. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: the Tailored Design Method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Referral patterns for patients with high-risk thyroid cancer. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(4):638-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haymart MR, Banerjee M, Yang D, et al. Variation in the management of thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):2001-2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wallner LP, Abrahamse P, Uppal JK, et al. Involvement of primary care physicians in the decision making and care of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(33):3969-3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papaleontiou M, Banerjee M, Yang D, Sisson JC, Koenig RJ, Haymart MR. Factors that influence radioactive iodine use for thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2013;23(2):219-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Weeks KS, Kahl AR, Lynch CF, Charlton ME. Racial/ethnic differences in thyroid cancer incidence in the United States, 2007-2014. Cancer. 2018;124(7):1483-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim II, Hochman T, Blumberg SN, Patel KN, Heller KS, Ogilvie JB. Disparities in the initial presentation of differentiated thyroid cancer in a large public hospital and adjoining university teaching hospital. Thyroid. 2012;22(3):269-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Golden SH, Brown A, Cauley JA, et al. Health disparities in endocrine disorders: biological, clinical, and nonclinical factors–an Endocrine Society scientific statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1579-E1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robinson D, Bell CM, Møller H, Basnett I. Effect of the UK government’s 2-week target on waiting times in women with breast cancer in southeast England. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(3):492-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Health Service. Stratified pathways of care—from concept to innovation. 2012. ProMED-mail website. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/publication/stratified-pathways-of-care-from-concept-to-innovation/

- 22. Hollenbeak CS, Wang L, Schneider P, Goldenberg D. Outcomes of thyroid cancer in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(2):210-215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaap K, Campbell R, Dove J, et al. Disparities in the care of differentiated thyroid cancer in the United States: exploring the National Cancer Database. Am Surg. 2017;83(7):739-746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Famakinwa OM, Roman SA, Wang TS, Sosa JA. ATA practice guidelines for the treatment of differentiated thyroid cancer: were they followed in the United States? Am J Surg. 2010;199(2):189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kovatch KJ, Reyes-Gastelum D, Hughes DT, Hamilton AS, Ward KC, Haymart MR. Assessment of voice outcomes following surgery for thyroid cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(9):823-829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shah SA, Adam MA, Thomas SM, et al. Racial disparities in differentiated thyroid cancer: have we bridged the gap? Thyroid. 2017;27(6):762-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. American Thyroid Association. Lo que necesitas saber sobre la tiroides! ProMED-mail website. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.thyroid.org/informacion-sobre-la-tiroides/

- 28. Hormone Health Network. Thyroid cancer. Endocrine Society. November 5, 2021. https://www.hormone.org/diseases-and-conditions/thyroid-cancer

- 29. Radhakrishnan A, Reyes-Gastelum D, Gay B, et al. Primary care provider involvement in thyroid cancer survivorship care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(9):e3300-e3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, et al. The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: a systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):156-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(6):611-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.