Abstract

Microglia, the resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), are poised to respond to neuropathology. Microglia play multiple roles in maintaining homeostasis and promoting inflammation in numerous disease states. The study of microglial innate immune programs has largely focused on exploring neurodegenerative disease states with the use of genetic targeting approaches. Our understanding of how microglia participate in immune responses against pathogens is just beginning to take shape. Here, we review existing animal models of CNS infection, with a focus on how microglial physiology and inflammatory processes control protozoan and viral infections of the brain. We further discuss how microglial participation in over-exuberant immune responses can drive immunopathology that is detrimental to CNS health and homeostasis.

Keywords: microglia, neuroimmunology, CNS infection, Toxoplasma gondii

Microglia: The Resident Immune Cells of the CNS

Microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, have commanded a plethora of research investigations in the rapidly expanding field of neuroimmunology. Microglia are tissue-resident macrophages (TRMs) – long-lived myeloid cells displaying transcriptional phenotypes shaped by their unique tissue microenvironment [1]. Unlike most TRM populations which primarily differentiate from fetal liver monocytes via definitive hematopoiesis, microglia arise solely from embryonic yolk sac macrophages through the distinct developmental pathway of primitive hematopoiesis [2–4]. Microglia are dynamic cells with complex morphology and highly motile arborizations. Microglial filopodia-like processes survey the entire brain volume every few hours, a process involving the detection of extracellular purines – notably adenosine-family molecules [5–7]. Research over the past decade has revealed roles for microglia in both developmental and homeostatic processes and as drivers of neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative models [8]. In the context of infection, however, our understanding of the roles of microglia has been far less explored.

Previous research on the role of microglia in infection has heavily relied on in vitro systems. The utility of these models, however, has been recently challenged due to the emergence of literature revealing that microglia rapidly de-differentiate when removed from their tissue microenvironment and plated on plastic [9]. This de-differentiation includes not only a loss of major transcription factors that maintain microglial homeostasis, but also the increased expression of pro-inflammatory markers not observed in vivo [10,11]. Hippocampal slice cultures allow for short-term ex vivo microglial pharmacological targeting, although this approach induces microglial activation over the course of several hours [12,13]. Over the last decade, however, innovations in microglial genetic targeting systems have advanced considerably for in vivo studies [14–18]. Importantly for CNS infection, these tools are needed to distinguish microglia from brain-infiltrating myeloid cells, which are commonly present during neuroinflammation and have historically confounded microglial-specific population analyses. Here, we will: (1) review current and emerging tools for studying microglia, (2) outline microglial innate and adaptive immune functions characterized across disease states, and (3) highlight emerging research investigating microglial roles in specific infection models, with an emphasis on parasitic CNS infection with Toxoplasma gondii and neurotropic viral models. We emphasize two key themes across these different disease states: (1) brain-resident microglia display CNS responses that are often non-redundant with that of brain-infiltrating macrophages, and (2) whether these functions are neuroprotective or detrimental to CNS health, depend on the specific context.

Microglial Physiology and Experimental Approaches

Microglia display a transcriptional signature that distinguish them from other myeloid populations in both humans and mice [19–22]. The brain is unique amongst most organs, in part, due to its limited capacity for regeneration following damage incurred by either invading pathogens or the immune system itself [23]. Microglia express transcriptional repressors, such as Sall1, Sall3, and Mef2a, which are thought to regulate their identity by restricting immune activation [18,21,24]. The microglial transcriptional signature also includes genes such as P2ry12, P2ry13, Hexb, and TMEM119 (Figure 1) [9,19–21,25]. Even when blood-derived monocytes are permitted to engraft and differentiate in the brain with the use of artificial pharmacological or irradiation systems that deplete the brain’s macrophage niche, the resulting engrafting macrophage population fails to acquire the classical microglial transcriptional signature [19–21]. Further developmental transplantation studies have revealed that neither fetal liver nor bone marrow progenitors, which arise from the process of definitive hematopoiesis and differentiate into TRM populations outside of the brain, are able to fully adopt a microglial signature within the brain [19]. These studies emphasize that microglia are shaped by their unique yolk sac ontogeny in addition to their local tissue microenvironment. Microglia are the primary hematopoietic cell population in the steady-state brain, which may poise them for rapid responses against neurotropic pathogens.

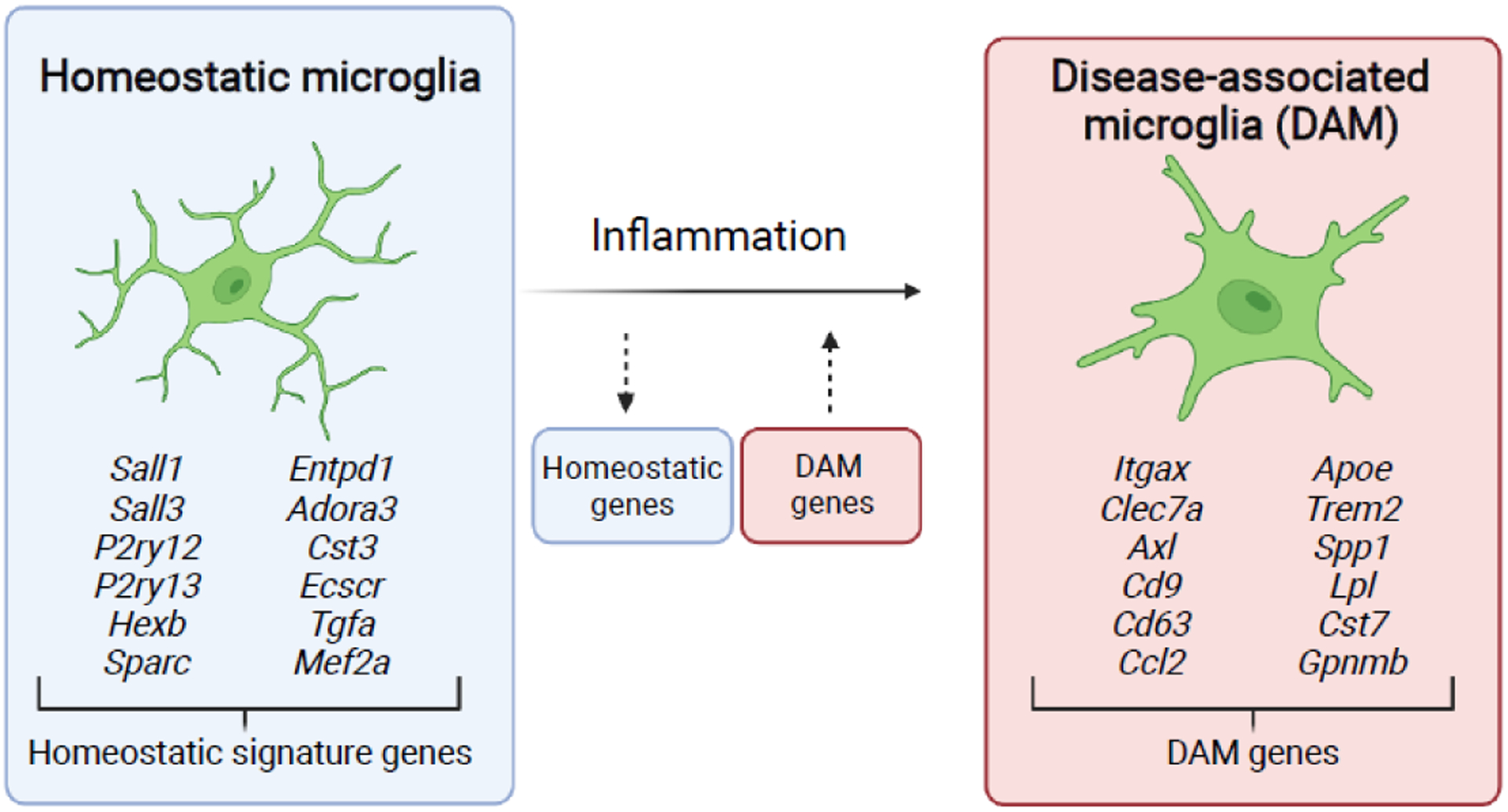

Figure 1. Transcriptional changes underlying the transition of homeostatic microglia to disease-associated microglia (DAM).

Homeostatic microglia express signature genes under steady state conditions that distinguish them from macrophage populations outside of the brain parenchyma. These homeostatic signature genes are downregulated upon neuroinflammatory challenge, with a concomitant upregulation of DAM genes that have been identified during neurodegenerative states. Large networks of transcriptional changes have been identified with the transition of homeostatic microglia to DAMs, with most common genes for each state highlighted [58,59].

Arguably, the most versatile tool currently used for manipulating microglia in vivo utilizes a tamoxifen-inducible cre recombinase (see Glossary) system. Under these systems, a targeted gene of interest is flanked by loxP sites and a cre-ERT2 recombinase is expressed, typically under the Cx3cr1 promoter [14,26]. Tamoxifen is delivered to mice harboring these transgenes, to induce cre recombinase activity that excises the target gene within a temporally restricted window of drug administration. The power of using an inducible cre system to study microglia stems from findings that microglia are long-lived and self-renew from a brain-resident CX3CR1-expressing population [27]. In contrast, CX3CR1-expressing myeloid cells that are recruited to the brain during inflammatory insults are short-lived and renew from CX3CR1-negative progenitors located in bone marrow [27]. Hence, by restricting cre activity to a defined window and subsequently permitting peripheral immune cell turnover, microglia can be genetically targeted separately from bone marrow-derived immune cells [14,26] (Figure 2A–C). This strategy is particularly valuable when studying microglia in infection or other inflammatory models in which a non-resident, monocyte-derived macrophage population infiltrates the brain [14,28]. While valuable in targeting microglia differentially to monocyte-lineage cells, the inducible CX3CR1-inducible cre system additionally targets tissue-resident macrophages along CNS interfaces, which include meningeal, perivascular, and choroid plexus macrophages (collectively referred to as CNS border-associated macrophages, or BAMs) [16,29]. As a result, alternative promoters for cre expression, including a Hexb cre, and binary cre systems that provide improved targeting specificity have been recently developed [16,17].

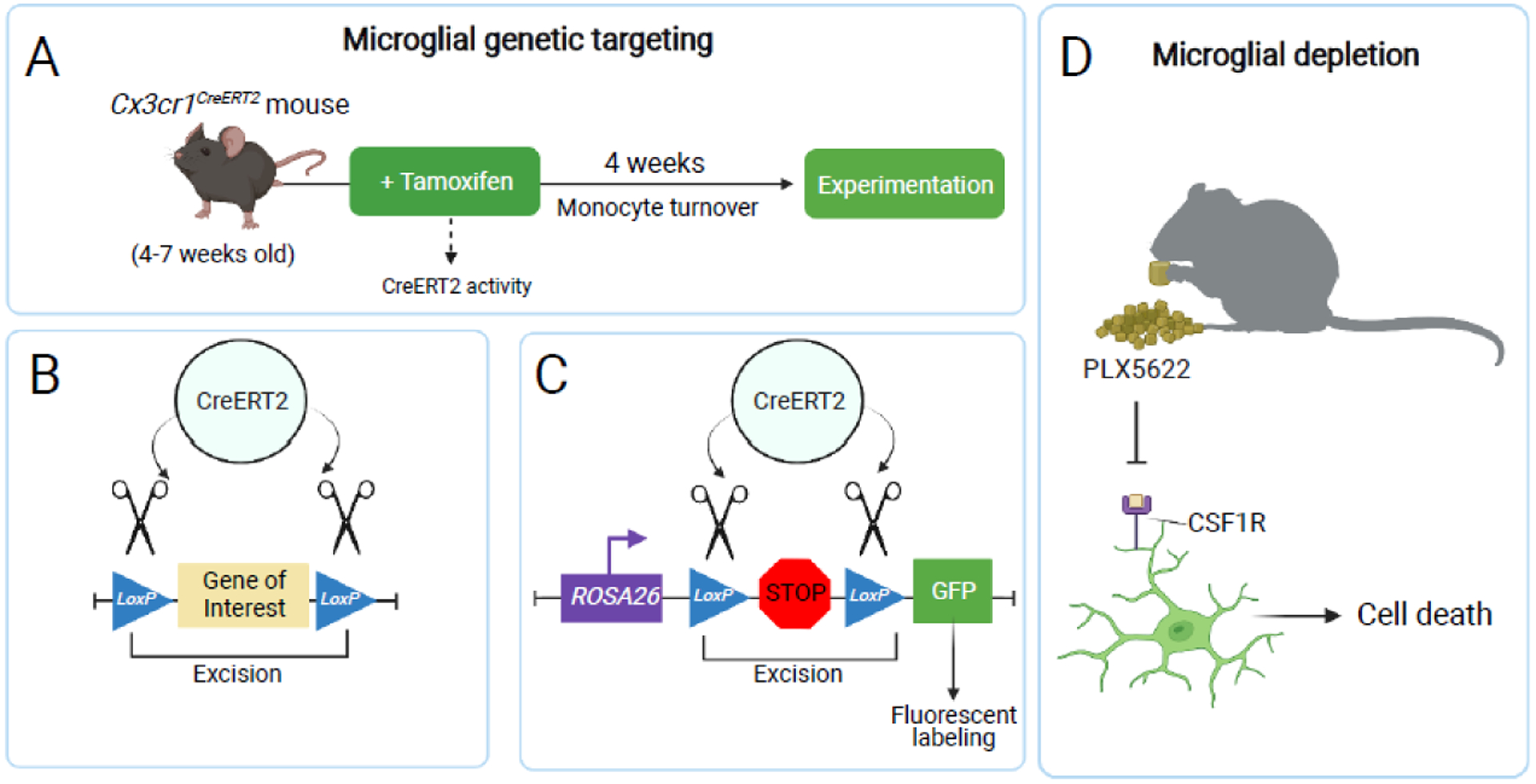

Figure 2. Experimental approaches for targeting microglia.

(A) Microglia can be genetically targeted using the CX3CR1 inducible cre system. A tamoxifen-inducible cre recombinase is expressed as a transgene under the Cx3cr1 promoter. Waiting four weeks post-tamoxifen administration restricts cre recombination largely to self-renewing CNS macrophages and their progeny, without targeting the renewed circulating myeloid compartment [14,26]. (B) Cre activity drives genetic recombination by excising an experimental gene of interest flanked by loxP sites (a “floxed” gene). (C) Cre activity can be used to excise a floxed stop codon inserted in the ROSA26 locus, permitting permanent fluorophore expression in CNS macrophages and their progeny. (D) Microglia can be pharmacologically depleted using a CSF1R antagonist, such as PLX5622. CSF1R antagonism leads to systemic macrophage cell death, due to the blockade of survival signals in macrophage populations [102,103].

Another widely-used approach for manipulating microglia in vivo includes pharmacological antagonism of CSF1R, a receptor vital for macrophage maintenance and survival [30]. The CSF1R antagonists, PLX3397 and PLX5622, lead to near-complete microglial elimination within days to weeks (depending on the formulation) when administered via chow [30] (Figure 2D). PLX5622 allows for increased microglial depletion and CSF1R specificity relative to PLX3397, as the latter additionally antagonizes KIT and FLT3, and also displays decreased brain penetrance [31]. Multiple genetic tools have similarly been used to deplete microglia, including cre-lox-mediated Csf1r deletion and mice deficient for Il34, the gene encoding the primary CSF1R ligand in the brain [20,32–34]. Multiple CNS viral infection studies have used PLX5622 to deplete microglia [35–39]. These studies, in the context of murine picornavirus, alphaherpes, and coronavirus infections, cumulatively highlight that mice lacking microglia display increased viral load and mortality, and they are unable to promote optimal T cell responses during CNS infection. However, there are multiple caveats to consider when interpreting the results from microglia depletion studies during neuroinflammation. Initial depletion studies suggested that microglial depletion does not appear to grossly impact animal behavior or general health, but more recent literature suggests that depletion may impair neurovascular vasodilation[40]. PLX5622 requires a few days for optimal microglial depletion, and rapid repopulation and return to baseline levels is similarly observed after treatment is stopped [37]. Additionally, CSF1R antagonism, even in models without inflammatory insult, results in system-wide depletion of several macrophage populations, disrupts dendritic cell proliferation, and results in increased astrogliosis and pro-inflammatory cytokine production–potentially confounding observed findings in these published works [38,41–43]. CSF1R antagonism has also been shown to deplete BAMs in some studies, although results across studies are mixed [37,44,45]. Further, CSF1R antagonism during both West Nile virus (WNV) and Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infections has been shown to decrease CD11c+ and MHC II+ antigen presenting cell (APC) numbers in blood, spleen, and lymph nodes, which may impair systemic T cell priming and activation independently of microglial roles in the brain [38,39]. Thus, caution is necessary when depleting microglia in disease models that rely on functional APC-T cell interactions.

Microglial Innate Immune Programs

Microglial spatial positioning throughout the brain and their complex “sensome” poises them to respond to several chemokines and cytokines released by other cells in response to inflammation, damage, and infection in the CNS [46–48]. RNA sequencing of microglia in homeostatic and neuroinflammatory contexts have revealed substantial differential gene expression upon activation [49,50]. One component of the activated microglial signature is the upregulation of complement system molecules, a cluster of innate immune proteins typically used in opsonizing and phagocytosing microbial pathogens or cellular debris [51,52]. In the healthy developing brain, numerous studies have shown that microglia express the complement proteins C1q and C3, and engage in the pruning of neuronal synapses via classical complement-dependent, receptor-mediated phagocytosis [53–55]. This synaptic pruning process, while required for the sculpting of functional synaptic circuits during development, has been shown to manifest aberrantly during neurodegenerative and infectious disease states, where complement activation leads to excessive synaptic pruning [33,56,57].

During neurodegenerative disease models for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Multiple Sclerosis (MS), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), microglia transition to a disease-associated microglia (DAM) phenotype [51,58]. DAMs are characterized by a downregulation of microglial homeostatic signature genes (including P2ry12, P2ry13, TMEM119, and Hexb), with a concomitant upregulation of inflammation-associated genes (Itgax, Apoe, Ccl2, Clec7a, and Spp1) (Figure 1). Transcriptomic analyses suggest that the DAM phenotype is regulated by both phagocytic clearance of cellular debris, and possibly interferon signaling [59]. Some research suggests that DAMs may be protective against neurodegeneration, but how they ultimately affect disease progression is unclear [58]. Mice that are deficient for or harbor the R47H human variant of TREM2 have microglia that are unable to acquire a full DAM phenotype, display increased neuronal dystrophy and amyloid beta plaque burden and microglial activation in the 5XFAD mouse model of early-onset AD [60–62]. However, additional studies have paradoxically shown that depleting microglia entirely in this same AD model results in amyloid plaque formation in the brain vasculature rather than the brain parenchyma, with no change in hippocampal learning and memory [31]. DAMs are poorly understood at the systems-level, but their discovery and characterization has expanded our understanding of microglial innate immune capacity on the cellular level. Indeed, a recent study highlights features of the DAM signature that are shared across infectious disease models, including LCMV and potentially a mouse model of SARS-Cov-2 infection – suggesting a conserved microglial phenotype shared between neurodegeneration and infection [63]. CNS infection models present intriguing opportunities for uncovering whether the pro-inflammatory activation signature of DAMs yields protective functional outcomes in other disease states.

Microglia as Activators of Adaptive Immunity

Given their myeloid lineage, microglia are presumed to serve as the professional antigen-presenting cells (APC) of the CNS. However, literature is both limited and mixed regarding their APC capacity. Under basal conditions and unlike most myeloid populations, only a small subpopulation (about 3%) of microglia express MHC class II, the critical antigen presentation molecules required for activating antigen-specific CD4+ T cells [64]. With inflammation, microglia upregulate MHC II across several conditions, yet its functionality in initiating and maintaining adaptive immune responses is unclear.

Different models of CNS infection, including CNS challenge with mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), can result in demyelination by self-reactive T cells following infection. During MHV infection, brain-infiltrating macrophages, but not brain-resident microglia, are the APC population capable of activating self-reactive CD4+ T cells, as evaluated by ex vivo assays [65]. In vivo approaches for investigating microglial APC capacity have also been performed during sterile experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and cuprizone-mediated demyelination. In these settings, type 2 conventional dendritic cells (cDC2s) are the potent APC population that activates encephalitogenic T cells, as microglial-specific genetic deletion of MHCII bears no impact on CD4+ T cell activation or clinical symptom development [64,66]. These studies collectively highlight intrinsic differences between microglia and other myeloid populations present in the brain during CNS infection, and their capacity to influence adaptive autoimmunity.

Whether microglial antigen presentation provides protective immunity against microbes more poorly understood. Two-photon imaging coupled with flow cytometric analysis of APCs during T. gondii infection has revealed that a large majority of microglia upregulate the traditionally dendritic cell-associated integrin, CD11c [67]. These live-imaging studies captured both transient and stable physical interactions between CD11c+ cells and antigen-specific CD8+ T cells, consistent with T cell receptor (TCR)-MHC I interactions [67]. However, given: (1) the presence of bone marrow-derived CD11c+ dendritic cells during CNS infection with T. gondii and (2) limitations associated with in vitro microglia assays, these studies are unable to determine whether these potential microglial-T cell interactions represent antigen presentation. Transient, non-apoptotic physical interactions between T cells and microglia have also been observed via intravital imaging during LCMV infection, with these studies also sharing similar caveats [68]. However, recent studies using an inducible CX3CR1-cre system was used to show that H-2Db (MHC I) in CNS-resident macrophages is required for mediating CD8+ T cell recruitment and optimal viral control during Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus (TMEV) infection [39]. In this latter study, it remains unclear whether microglia were a necessary APC population for CD8+ T cell activation, or if perivascular macrophages were instead the cell type most relevant to T cell priming and recruitment from the blood [29]. Emerging genetic tools that allow for more specific targeting of microglia independently of border-associated macrophages, such as a split cre or Hexb cre-driven systems, will be necessary to clarify the field’s understanding of microglia-specific APC capacity during CNS infection models [16,17].

Microglia Promote Neuroinflammatory Processes

Microglia serve as a key source of cytokines within the CNS at baseline and in disease contexts. Animal models of neurodegeneration and LCMV infection have been used to study activated microglia in vivo, where both microgliosis and morphological changes are observed in these cells [51,58,68–70]. During EAE, deletion of MAP3K7 (the gene encoding the NF-κB modulator, TAK1), results in the abrogation of autoimmune inflammation and clinical pathology in mice [14]. Arguably, most studies of microglial inflammatory responses are neurodegeneration-focused, where a pattern has emerged that overexuberant microglial activation results in tissue damage [10,14,33,56]. In some cases this immunopathology is indirect, as microglia may drive the formation of neurotoxic astrocytes in neurodegenerative models through the release of C1q, IL-1, and TNF-α [10]. Research in CNS infection is currently emerging that provides insights to how these pro-inflammatory processes may translate to neuroprotection during CNS infection, rather than observed neurotoxic and degenerative phenotypes in sterile contexts.

Microglia in CNS Infection Models

Current research efforts to understand the intricate interactions of microglia with the rest of the immune system suggest that microglia have many ways to respond to infection and drive innate immunity. Here, we summarize the roles of microglia in several experimental infection states, and explore their roles in cytokine release, synaptic pruning, and driving an innate immune response.

Cerebral Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasma gondii is a well-studied intracellular protozoan parasite capable of infecting nucleated cells in virtually all warm-blooded vertebrates, including 25–30% of the global human population [71,72]. As a neurotropic parasite, there are several key advantages of using T. gondii as a model to study microglia during CNS infection. Notably, T. gondii traffics to the brain following peripheral inoculation and the establishment of CNS infection does not require intracranial injection [71,72]. Peripheral inoculation spares the brain from the robust CNS injury response and resulting microglial activation and it also allows the peripheral immune system to be primed before parasites reach the brain [47,51]. T. gondii infection in both humans and mice occurs in two phases: (1) an acute infection that disseminates widely throughout host tissues, and (2) a chronic, latent infection largely restricted to the immune-privileged CNS [71,72]. While acute T. gondii infection has been most heavily studied, both phases of infection converge on a protective immune response governed by the critical T cell-derived cytokine, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) [71].

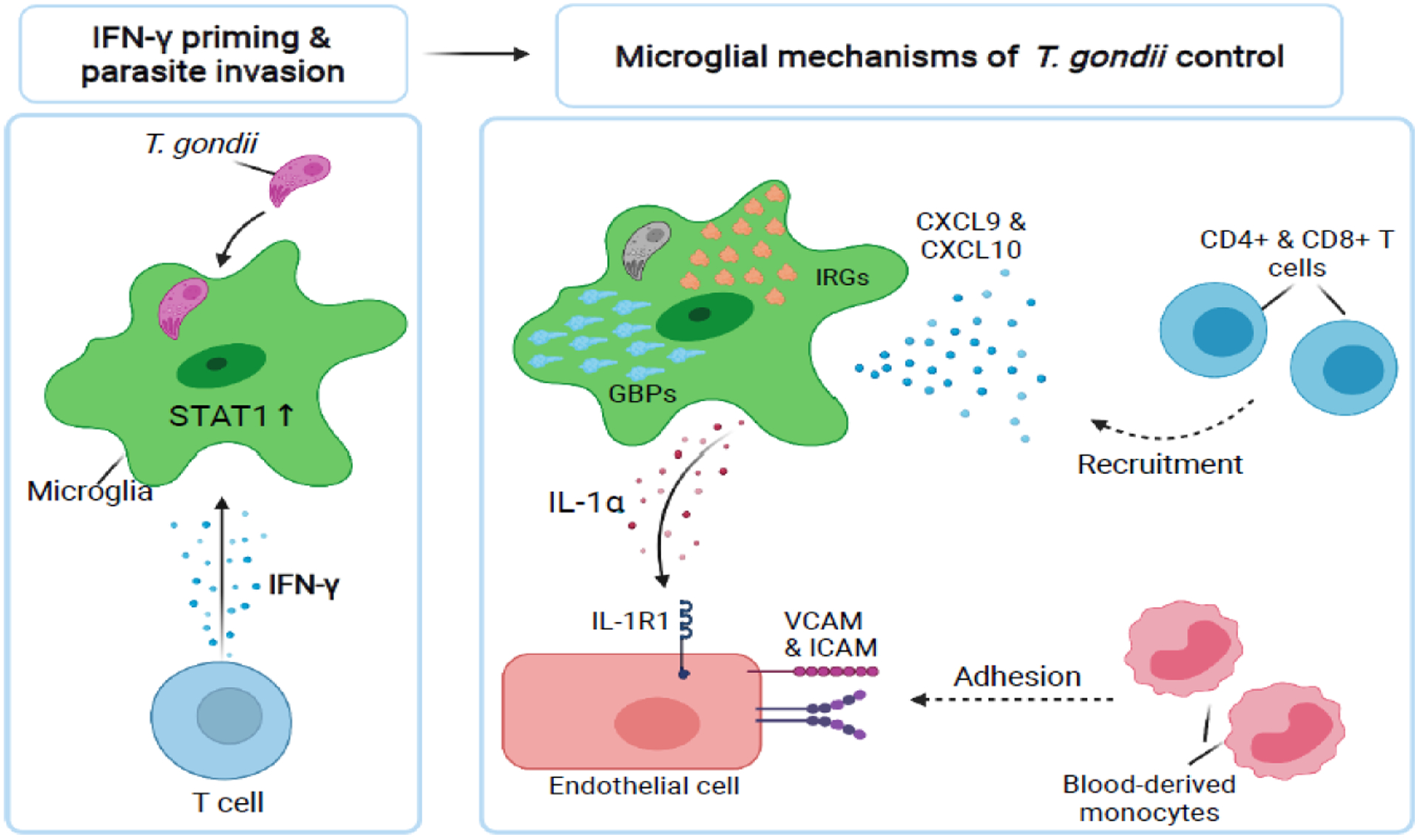

Most hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cell types are capable of responding to IFN-γ via signaling through the downstream transcription factor, STAT1 [73,74]. IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling is essential for the upregulation of anti-parasitic molecules, such as guanylate-binding proteins (GBPs) and immunity-related GTPases (IRGs) [71,73]. These cytosolic proteins are encoded by large gene families and are required for cooperatively targeting and disrupting the T. gondii parasitophorous vacuole or promoting parasite elimination via autophagy [75–78]. Monocyte-derived cells additionally require IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling for the upregulation of specialized cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic anti-toxoplasmic programs, including nitric oxide production via the enzyme, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and the upregulation of the antigen presentation molecules required for T cell activation and further IFN- γ production from T cells [74,79]. The specific IFN-γ-STAT1 mechanisms of resistance employed by microglia during CNS infection with T. gondii have not yet been defined, but may parallel those of monocyte-derived cells, including the recruitment of immune cells via the T-cell chemoattractants CXCL9 and CXCL10 [80–82]. Microglia produce both of these chemokines during T. gondii infection and CXCL10 is required for CD8+ T cell recruitment to the CNS, where its inhibition leads to increased brain parasite burden [82,83]. Together, previous studies strongly suggest that IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling in microglia may be required for controlling T. gondii in the brain (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Microglial responses to CNS infection with Toxoplasma gondii.

Microglia in the brain likely respond to T cell-derived IFN-γ and activate the downstream transcription factor, STAT1. IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling primes host cells to respond to intracellular parasitic infection. Upon parasite invasion, IFN-γ-STAT1 signaling may confer microglia with the cell-intrinsic ability to clear the parasite via Immunity-Related GTPases (IRG) and Guanylate-Binding Proteins (GBP) activity. Microglial also produce the chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10, which recruit T cells to the brain to fight infection. In addition to IFN-γ-mediated mechanisms of parasite control, microglia have been recently shown to release the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1α, to activate CNS endothelial cells, driving the recruitment of anti-parasitic monocyte-derived cells from the blood into the CNS [48].

Alarmins are damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) sequestered intracellularly and canonically released upon tissue damage or inflammasome activation [84,85]. A recent paper has revealed that microglia release the cytosolic alarmin, IL-1α, to control CNS infection with T. gondii [48]. Microglial IL-1α was shown to upregulate adhesion molecules on the brain vasculature to permit the infiltration of anti-parasitic monocytes from the blood into the brain to control CNS parasite burden (Figure 3). This study used an inducible Cx3cr1-driven fluorescent reporter as a tool to discriminate microglia from blood-derived myeloid cells, revealing that microglia are the key source of IL-1α in both the steady-state and T. gondii-infected brain. Batista et al. showed that microglia release IL-1α ex-vivo, in a gasdermin-D-dependent manner. While microglial-derived IL-1α is required to control T. gondii parasite burden during chronic infection, IL-1α-deficient mice do not succumb to infection. Surprisingly, IL-1α but not IL-1 β is required for controlling T. gondii parasite burden in a manner that phenocopies Il-1R1-deficient mice, despite the two cytokines being both expressed in the brain and sharing the same receptor. These studies also revealed that IL-1α signaling via Il-1R1 does not alter brain IFN- γ levels or lead to animal mortality, but instead regulates infiltrating monocyte number and ability to express iNOS.

Interestingly, this microglial-specific control of parasite burden occurred despite a dampened NF-κB signature in resident microglia relative to blood-derived myeloid in the brain. This study thus highlighted physiological distinctions between the two key macrophage populations responding to T. gondii infection, despite a shared tissue micro-environment in the inflamed brain. Because gasdermin-D has been characterized an essential driver of inflammasome-mediated pyroptotosis, this work suggests that microglial IL-1α release and control of infection is mediated by cell death [86]. The potential triggers of microglial cell death and the specific inflammasome sensor(s) required for IL-1α release remain unidentified. Alarmin release by resident glial cells may serve as a key effector program in prompting immune activation and parasite control in discrete regions of the CNS, without resulting in unrestrained, tissue-wide neuroinflammation and resulting immunopathology.

Microglia may be especially poised to respond to lytic cell death stemming from focal sites of T. gondii replication, in part through purinergic-mediated chemotaxis. Several studies have demonstrated that the microglial “sensome” includes purinergic receptors that regulate their motility, including P2RY12, P2RY13, P2RY6, and P2RX4 [6,46]. These receptors collectively mediate cellular chemotactic responses to ATP and adenosine-family purines. Notably, a loss of purinergic signaling due to genetic deletion or the delivery of purinergic inhibitors results in a loss of the rapid microglial chemotactic responses to sites of acute injury, in addition to markedly reduced baseline motility [6,47,87]. While microglia are evenly spatially distributed throughout the steady-state brain, they lose their uniform tiling and migrate into nodules surrounding T. gondii replication in the infected brain [88,89]. While not yet explored, T. gondii-induced cell lysis and the resulting liberation of purinergic alarmins may mobilize and position microglia to focal sites of parasite replication to restrict pathogen growth. Their resident status in the CNS, coupled with a unique sensome not shared by other myeloid populations, may thus position microglia to serve as first responders to CNS infection, possibly by pinpointing discrete regions of the brain that require recruitment and activation of blood-derived immune cells for parasite restriction.

West Nile Virus and Japanese Encephalitis Virus

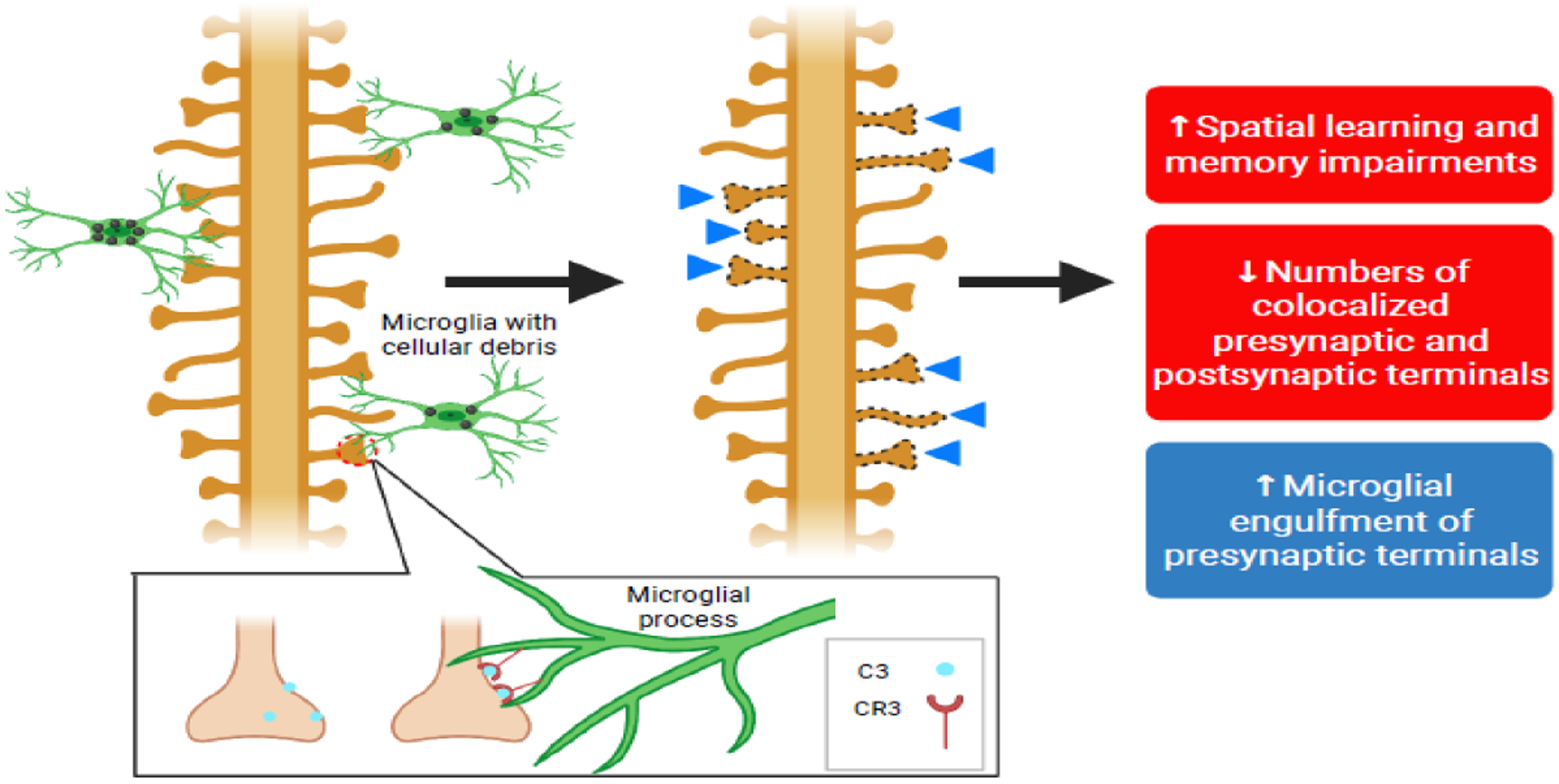

West Nile Virus (WNV) and Japanese Encephalitis Virus (JEV) are mosquito-borne, neurotropic flaviviruses that cause widespread morbidity and mortality throughout the human population [90]. A WNV neuroinvasive disease model determined that microglial activation drives complement-mediated synapse elimination and neurocognitive impairments in mice (Figure 4). IL-34-deficient mice, which lack most microglia, were shown to be protected from synapse loss and the cognitive sequelae stemming from WNV infection [33]. In both WNV and JEV, microglia appear to be critical for preventing disease progression, as microglial depletion with the CSF1R antagonist PLX5622 results in increased CNS viral load and mortality [38,91]. This neuroprotection may be mediated by phagocytosis and the release of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines by activated microglia, including CXCL10, CCL5, CCL2, TNF-α, and IL-6 as suggested by ex vivo spinal cord culture [92]. Whether microglia primarily respond to pro-inflammatory cytokines in an autocrine manner or protective immune responses are mediated cell-extrinsically by other brain-resident or infiltrating cells remains unclear. However, these studies suggest that microglia may serve protective roles in controlling neurotropic viral infection, and also highlight that microglia activation leads to synapse loss and neuronal dysfunction as is similarly observed in neurodegenerative models.

Figure 4. Microglial-mediated synaptic pruning in West Nile Virus (WNV) drives neurocognitive sequelae.

The microglial-derived complement protein, C3, mediates microglial engulfment of synaptic terminals (synaptic pruning) via CR3-dependent receptor-mediated phagocytosis during WNV infection. Hippocampal CA3 synaptic terminals are excessively pruned following infection-induced microglial activation, leading to impaired spatial learning acquisition and memory recall [33].

Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses have gained global interest due to the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Unsurprisingly, microglial activation is observed in CNS infection with various coronaviruses. Infection with the J2.2v-1 neuro-attenuated strain of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a murine coronavirus, drives acute encephalitis and chronic de-myelination in mice [65,93–95]. A 2018 study showed that microglial depletion with PLX5622 resulted in increased MHV viral protein expression in neurons and mortality, along with diminished CD4+ and CD8+ brain T cell counts and IFN- γ production [37]. This research lends supports to the notion that microglia may serve as APCs or promote the recruitment, retention, or survival of T cells in the brain during viral infection.

Additional studies using pharmacological depletion of microglia with the J2.2v-1 strain of MHV found similar results with respect to viral load, associated with increased white matter damage in both brain and spinal cord [94]. This latter research reported more modest decreases in CD4+ T cell activation and concomitant increases in both CD8+ T cell and B cell populations. [94]. The mixed results of these separate MHV studies may relate to differences in the timing of pharmacological depletion of microglia between the two studies. However, these reports remain consistent with an expanding pool of literature across several viral models supporting a role for microglia in controlling CNS viral replication.

In addition to viral clearance, the role of microglia in coronavirus-induced demyelination has been examined by multiple groups [93–96]. While targeted depletion of peripheral macrophages does not alter demyelinating disease progression following JHV infection, an intact microglial population, is critical for neuroprotection [94,96]. Depleting microglia via PLX5622 during late stages of viral clearance leads to exacerbated white matter damage, impaired oligodendrocyte function, and the persistence of myelin debris, each consistent with this neuroprotective role [94,96]. These findings underscore fundamental functional differences between resident microglia and peripherally-derived macrophages that are recruited to the CNS during infection.

The role of various CNS cells in SARS-CoV-2 infection has only been preliminarily investigated, but there is clear evidence of microglial activation in post-mortem human COVID-19 brain tissue [97,98]. Similarly to CNS infection with T. gondii, microglial nodules, or the aggregation of activated microglia within discrete foci, are observed in post-mortem brain samples of COVID-19 patients [98–100]. SARS-CoV-2 infection in the CNS is largely restricted to ACE2-receptor-expressing cells within the olfactory bulb and brainstem vasculature – presenting the paradox of what parenchymal microglia may be responding to within nodules [99]. A potential explanation may involve microglial migration to sites of blood-brain-barrier damage stemming from vascular viral replication or robust CD8+ T cell infiltration to the brain [99]. Multiple studies have highlighted microglial purinergic-dependent juxtapositioning with the brain vasculature, either upon induced injury, or under steady-state conditions in micro-segments of the neurovascular unit displaying limited astrocytic endfoot coverage [40,87,101]. A leaky blood-brain-barrier caused by the cytokine storm resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection may result in microglial nodule formation in areas displaying blood-brain-barrier disruption, where CD8+ T cells may contribute to vascular immunopathology [99]. Whether microglial activation mediates the poorly understood neurological sequelae of COVID-19, as is the case in WNV infection, is yet to be determined. Given the role of microglia in driving neuroinflammation via pro-inflammatory cytokine release, promoting neurotoxic astrocyte development, and promoting excessive synaptic pruning, these may take center stage in studies exploring the new clinical phenomenon of “neuro-COVID.”

Concluding Remarks

Recent studies investigating microglial function during CNS infection highlight two main themes: (1) microglia as a key mediator of neuroprotection against invading pathogens and (2) microglia as inflammatory drivers of neuropathology and degeneration. In several infection models, microglia are collectively protective in combatting pathogen growth, by releasing and responding to proinflammatory cytokines, as well as via recruiting anti-parasitic and anti-viral blood-derived immune cells [35,37,48]. This immune activation can simultaneously prove detrimental, as inflammation caused by microglial activation may result in neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration [10,14,33,56]. Current work highlights this central need for the immune system to strike a balance between pathogen control and immune tolerance during CNS infection in order to prevent neuropathology. The field of neuroimmunology is continuing to learn the ways in which microglial ontogeny and their unique transcriptional identity as CNS-resident cells influences functional responses that differ from blood-derived immune cells [19–21,48]. With the advent of emerging experimental tools for studying microglia, further research will expand our growing understanding of how microglial physiology confers neuroprotection against CNS infection and other disease states (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions.

Do infections induce a similar disease-associated microglia (DAM) gene signature to that observed in models of neurodegenerative disease? How do genes associated with the DAM signature influence the anti-microbial functions of microglia?

Do microglia have the capacity to serve as antigen-presenting cells that optimally activate anti-microbial T cells in the brain parenchyma?

Do microglia respond to damage-associated purine release during CNS infection as they do during CNS injury states?

What factors lead to microglia nodule formation during CNS infection?

Is microglial physical apposition with the brain vasculature required for CNS pathogen control or for maintaining tissue homeostasis during infection?

Highlights.

Microglia, the primary immune cell population in the brain, play distinct roles in development and homeostasis. To study them during neuroinflammatory states, researchers use experimental paradigms such as an inducible-cre system and pharmacological antagonism of the CSF1 receptor with its antagonist PLX5622.

Microglia are poised to respond to key signals for inflammation, damage, and infection in the central nervous system (CNS). They are able to promote inflammation via the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and potentially serve as functional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) during infection.

Understanding the specific roles of microglia in experimental infection models will allow us to gain a deeper knowledge on how important microglia-induced inflammation is for combatting neurotropic pathogens, while also recognizing that this inflammation may cause significant damage to other cell types in the CNS.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Isaac Babcock, Mike Kovacs, and Lydia Sibley, the other members of the Harris lab, for their time and effort in reading this article, providing valuable and appreciated feedback, and engaging in continuous discussions and learning. This work was supported by NIH grants R56 R01106028 and R01NS112516 to THH and T32AI007496 to MNC and by the University of Virginia Office of Undergraduate Research Double Hoo Award to MNC and IS and the Harrison Undergraduate Research Award to IS. All figures were created using BioRender.

Glossary

- Cre recombinase

An enzyme of viral origin that drives genetic recombination at flanking loxP or “floxed” sites incorporated into a genome. Cre is often expressed as a transgene to operate as “molecular scissors” in specific cell types.

- Inducible Cre recombinase

A chimeric cre recombinase fused to an estrogen receptor binding domain. Pharmacological administration of the estrogen agonist, tamoxifen, drives cre translocation to the nucleus, where it cleaves loxP transgenes flanking a target gene and results in gene excision. Commonly driven by the Cx3cr1 gene promoter to temporally control microglial genetic manipulations and to increase cell type specificity.

- Complement system

A family of small, soluble and membrane-bound proteins and their receptors that confers resistance against microbes and promotes debris clearance. Traditionally, complement accumulates on pathogens to promote their opsonization and phagocytosis by specialized phagocytes. In the CNS, the complement proteins, C1q and C3, localize to synapses normally during development and aberrantly in neurodegenerative settings, where they lead to synaptic pruning.

- Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R)

A surface receptor expressed on myeloid cells and required for macrophage survival. Its pharmacological antagonism via PLX3397 and PLX5622 results in the depletion of microglia and additional macrophage populations.

- Disease-Associated Microglia (DAM)

A unique subset of microglia first identified in neurodegenerative disease states, including Alzheimer’s Disease. Characterized by the decreased expression of homeostatic microglia signature genes and the upregulation of markers including CD11c, Clec7a, and MHC II. The transition from homeostatic microglia to DAMs is regulated by TREM2-APOE signaling in mice.

- Antigen Presentation Cells

Cells with surface expression of foreign molecules, or antigen, in the context of major histocompatibility (MHC) proteins. Antigen presented via MHC I and MHC II prime CD8+ and CD4+ T cells via MHC-T cell receptor binding, respectively. Professionally performed by myeloid-lineage immune cells, including dendritic cells and macrophages.

- Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)

A pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by immune cells, typically in response to intracellular infections. Signals through the transcription factor, STAT1, to drive a wide array of different cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic immune programs in responding cells. Upregulates antigen presentation machinery, iNOS, cytokines,chemokines, IRGs, and GBPs.

- Immunity Related GTPases (IRGs)

A family of interferon-regulated, antimicrobial cytosolic proteins that confer cellular resistance against intracellular protozoan and bacterial infections. Also known as the p47 GTPases.

- Guanylate Binding Proteins (GBPs)

A family of interferon-regulated, antimicrobial cytosolic proteins that confer cellular resistance against intracellular protozoan and bacterial infections. More conserved in the human genome, relative to IRG family proteins.

- Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS)

an interferon-regulated enzyme that uses L-arginine and NADPH to catalyze a series of reactions that result in reactive nitrogen release. Potent inhibitor of intracellular viral, bacterial, and protozoan replication. Essential for the control of CNS infection with the protozoan parasite, Toxoplasma gondii.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Blériot C et al. (2020) Determinants of Resident Tissue Macrophage Identity and Function. Immunity 52, 957–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginhoux F et al. (2010) Fate Mapping Analysis Reveals That Adult Microglia Derive from Primitive Macrophages. Science (80-. ). 330, 841–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kierdorf K et al. (2013) Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1-and Irf8-dependent pathways. Nat. Neurosci 16, 273–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Askew K et al. (2017) Coupled Proliferation and Apoptosis Maintain the Rapid Turnover of Microglia in the Adult Brain. Cell Rep. 18, 391–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nimmerjahn A et al. (2005) Resting Microglial Cells Are Highly Dynamic Surveillants of Brain Parenchyma in Vivo. Sci. Reports 1314, 1314–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davalos D et al. (2005) ATP mediates rapid microglial response to local brain injury in vivo. Nat. Neurosci 8, 752–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernier L-P et al. (2019) Nanoscale Surveillance of the Brain by Microglia via cAMP-Regulated Filopodia. Cell Rep. 27, 2895–2908.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salter MW and Stevens B (2017) Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat. Med 23, 1018–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohlen CJ et al. (2017) Diverse Requirements for Microglial Survival, Specification, and Function Revealed by Defined-Medium Cultures. Neuron 94, 759–773.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liddelow SA et al. (2017) Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 541, 481–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosselin D et al. (2017) An environment-dependent transcriptional network specifies human microglia identity. Science (80-. ). 356, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dailey ME et al. (2013) Imaging Microglia in Brain Slices and Slice Cultures. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc 2013, pdb.prot079483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madry C et al. (2018) Microglial Ramification, Surveillance, and Interleukin-1β Release Are Regulated by the Two-Pore Domain K+ Channel THIK-1. Neuron 97, 299–312.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldmann T et al. (2013) A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1618–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser T and Feng G (2019) Tmem119-EGFP and Tmem119-CreERT2 Transgenic Mice for Labeling and Manipulating Microglia. eneuro 6, ENEURO.0448–18.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J-S et al. (2021) A Binary Cre Transgenic Approach Dissects Microglia and CNS Border-Associated Macrophages. Immunity 54, 176–190.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masuda T et al. (2020) Novel Hexb-based tools for studying microglia in the CNS. Nat. Immunol 21, 802–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buttgereit A et al. (2016) Sall1 is a transcriptional regulator defining microglia identity and function. Nat. Immunol 17, 1397–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett FC et al. (2018) A Combination of Ontogeny and CNS Environment Establishes Microglial Identity. Neuron 98, 1170–1183.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronk JC et al. (2018) Peripherally derived macrophages can engraft the brain independent of irradiation and maintain an identity distinct from microglia. J. Exp. Med 215, 1627–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shemer A et al. (2018) Engrafted parenchymal brain macrophages differ from microglia in transcriptome, chromatin landscape and response to challenge. Nat. Commun 9, 5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geirsdottir L et al. (2019) Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Divergence of the Primate Microglia Program. Cell 179, 1609–1622.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fricker M et al. (2018) Neuronal Cell Death. Physiol. Rev 98, 813–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koso H et al. (2016) Conditional rod photoreceptor ablation reveals Sall1 as a microglial marker and regulator of microglial morphology in the retina. Glia 64, 2005–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butovsky O et al. (2014) Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci 17, 131–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yona S et al. (2013) Fate Mapping Reveals Origins and Dynamics of Monocytes and Tissue Macrophages under Homeostasis. Immunity 38, 79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prinz M et al. (2017) Ontogeny and homeostasis of CNS myeloid cells. Nat. Immunol 18, 385–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saederup N et al. (2010) Selective Chemokine Receptor Usage by Central Nervous System Myeloid Cells in CCR2-Red Fluorescent Protein Knock-In Mice. PLoS One 5, e13693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldmann T et al. (2016) Origin, fate and dynamics of macrophages at central nervous system interfaces. Nat. Immunol 17, 797–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green KN et al. (2020) To Kill a Microglia: A Case for CSF1R Inhibitors. Trends Immunol. 41, 771–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spangenberg E et al. (2019) Sustained microglial depletion with CSF1R inhibitor impairs parenchymal plaque development in an Alzheimer’s disease model. Nat. Commun 10, 1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y et al. (2012) IL-34 is a tissue-restricted ligand of CSF1R required for the development of Langerhans cells and microglia. Nat. Immunol 13, 753–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasek MJ et al. (2016) A complement-microglial axis drives synapse loss during virus-induced memory impairment. Nature 534, 538–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kana V et al. (2019) CSF-1 controls cerebellar microglia and is required for motor function and social interaction. J. Exp. Med 216, 2265 LP – 2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waltl I et al. (2018) Microglia have a protective role in viral encephalitis-induced seizure development and hippocampal damage. Brain. Behav. Immun 74, 186–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fekete R et al. (2018) Microglia control the spread of neurotropic virus infection via P2Y12 signalling and recruit monocytes through P2Y12-independent mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 461–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wheeler DL et al. (2018) Microglia are required for protection against lethal coronavirus encephalitis in mice. J. Clin. Invest 128, 931–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Funk KE and Klein RS (2019) CSF1R antagonism limits local restimulation of antiviral CD8+ T cells during viral encephalitis. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goddery EN et al. (2021) Microglia and Perivascular Macrophages Act as Antigen Presenting Cells to Promote CD8 T Cell Infiltration of the Brain. Front. Immunol 12, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bisht K et al. (2021) Capillary-associated microglia regulate vascular structure and function through PANX1-P2RY12 coupling in mice. Nat. Commun 12, 5289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mok S et al. (2014) Inhibition of CSF-1 receptor improves the antitumor efficacy of adoptive cell transfer immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 74, 153–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tagliani E et al. (2011) Coordinate regulation of tissue macrophage and dendritic cell population dynamics by CSF-1. J. Exp. Med 208, 1901–1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruttger J et al. (2015) Genetic Cell Ablation Reveals Clusters of Local Self-Renewing Microglia in the Mammalian Central Nervous System. Immunity 43, 92–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willis EF et al. (2020) Repopulating Microglia Promote Brain Repair in an IL-6-Dependent Manner. Cell 180, 833–846.e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu AML et al. (2021) Aging and CNS Myeloid Cell Depletion Attenuate Breast Cancer Brain Metastasis. Clin. Cancer Res 27, 4422–4434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hickman SE et al. (2013) The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat. Publ. Gr 16, 1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roth TL et al. (2014) Transcranial amelioration of inflammation and cell death after brain injury. Nature 505, 223–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Batista SJ et al. (2020) Gasdermin-D-dependent IL-1α release from microglia promotes protective immunity during chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection. Nat. Commun 11, 3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathys H et al. (2017) Temporal Tracking of Microglia Activation in Neurodegeneration at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Rep. 21, 366–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hammond TR et al. (2018) Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Microglia throughout the Mouse Lifespan and in the Injured Brain Reveals Complex Cell-State Changes. Immunity DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krasemann S et al. (2017) The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norris GT et al. (2018) Neuronal integrity and complement control synaptic material clearance by microglia after CNS injury. J. Exp. Med 215, jem.20172244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schafer DP et al. (2012) Microglia Sculpt Postnatal Neural Circuits in an Activity and Complement-Dependent Manner. Neuron 74, 691–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bialas AR and Stevens B (2013) TGF-β signaling regulates neuronal C1q expression and developmental synaptic refinement. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1773–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 55.Kopec AM et al. (2018) Microglial dopamine receptor elimination defines sex-specific nucleus accumbens development and social behavior in adolescent rats. Nat. Commun 9, 3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hong S et al. (2016) Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science (80-. ). 352, 712–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Y et al. (2019) Persistent Toxoplasma Infection of the Brain Induced Neurodegeneration Associated with Activation of Complement and Microglia. Infect. Immun 87, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keren-Shaul H et al. (2017) A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 169, 1276–1290.e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krasemann S et al. (2017) The TREM2-APOE Pathway Drives the Transcriptional Phenotype of Dysfunctional Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y et al. (2015) TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer ‘ s Disease Model Article TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer ‘ s Disease Model. Cell 160, 1061–1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y et al. (2016) TREM2-mediated early microglial response limits diffusion and toxicity of amyloid plaques. J. Exp. Med 213, 667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song WM et al. (2018) Humanized TREM2 mice reveal microglia-intrinsic and -extrinsic effects of R47H polymorphism. J. Exp. Med 215, 745–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dorman LC et al. (2021) A type I interferon response defines a conserved microglial state required for effective phagocytosis. bioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/2021.04.29.441889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wolf Y et al. (2018) Microglial MHC class II is dispensable for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and cuprizone-induced demyelination. Eur. J. Immunol 48, 1308–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Savarin C et al. (2015) Self-reactive CD4+ T cells activated during viral-induced demyelination do not prevent clinical recovery. J. Neuroinflammation 12, 207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mundt S et al. (2019) Conventional DCs sample and present myelin antigens in the healthy CNS and allow parenchymal T cell entry to initiate neuroinflammation. Sci. Immunol DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau8380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.John B et al. (2011) Analysis of behavior and trafficking of dendritic cells within the brain during toxoplasmic encephalitis. PLoS Pathog. 7, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herz J et al. (2015) Therapeutic antiviral T cells noncytopathically clear persistently infected microglia after conversion into antigen-presenting cells. J. Exp. Med 212, 1153–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ajami B et al. (2007) Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat. Neurosci 10, 1538–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nayak D et al. (2013) Type I Interferon Programs Innate Myeloid Dynamics and Gene Expression in the Virally Infected Nervous System. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matta SK et al. (2021) Toxoplasma gondii infection and its implications within the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Microbiol DOI: 10.1038/s41579-021-00518-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mendez OA and Koshy AA (2017) Toxoplasma gondii: Entry, association, and physiological influence on the central nervous system. PLoS Pathog. 13, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hunter CA and Sibley LD (2012) Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 10, 766–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kak G et al. (2018) Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ): Exploring its implications in infectious diseases. Biomol. Concepts 9, 64–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yamamoto M et al. (2012) A cluster of interferon-γ-inducible p65 gtpases plays a critical role in host defense against toxoplasma gondii. Immunity 37, 302–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao YO et al. (2009) Disruption of the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole by IFNγ-inducible immunity-related GTPases (IRG proteins) triggers necrotic cell death. PLoS Pathog. 5, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khaminets A et al. (2010) Coordinated loading of IRG resistance GTPases on to the Toxoplasma gondii parasitophorous vacuole. 12, 939–961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fisch D et al. (2019) Human GBP1 is a microbe-specific gatekeeper of macrophage apoptosis and pyroptosis. Embo J DOI: 10.15252/embj.2018100926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tur J et al. (2021) Induction of CIITA by IFN-γ in macrophages involves STAT1 activation by JAK and JNK. Immunobiology 226, 152114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strack A et al. (2002) Chemokines are differentially expressed by astrocytes, microglia and inflammatory leukocytes in Toxoplasma encephalitis and critically regulated by interferon-γ. Acta Neuropathol. 103, 458–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ochiai E et al. (2015) CXCL9 is important for recruiting immune T cells into the brain and inducing an accumulation of the T cells to the areas of tachyzoite proliferation to prevent reactivation of chronic cerebral infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Am. J. Pathol 185, 314–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harris TH et al. (2012) Generalized Lévy walks and the role of chemokines in migration of effector CD8 + T cells. Nature 486, 545–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Norose K et al. (2011) CXCL10 is required to maintain T-cell populations and to control parasite replication during chronic ocular toxoplasmosis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 52, 389–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang D et al. (2017) Alarmins and immunity. Immunol. Rev 280, 41–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Phulphagar K et al. (2021) Proteomics reveals distinct mechanisms regulating the release of cytokines and alarmins during pyroptosis. Cell Rep. 34, 108826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu X et al. (2016) Inflammasome-activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature 535, 153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lou N et al. (2016) Purinergic receptor P2RY12-dependent microglial closure of the injured blood–brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 113, 1074–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ferguson DJ et al. (1991) Pathological changes in the brains of mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii: a histological, immunocytochemical and ultrastructural study. Int. J. Exp. Pathol 72, 463–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ferguson DJP et al. (1989) Tissue cyst rupture in mice chronically infected withToxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Res 75, 599–603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Daep CA et al. (2014) Flaviviruses, an expanding threat in public health: focus on dengue, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis virus. J. Neurovirol 20, 539–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Seitz S et al. (2018) Pharmacologic Depletion of Microglia Increases Viral Load in the Brain and Enhances Mortality in Murine Models of Flavivirus-Induced Encephalitis. J. Virol 92, 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Quick ED et al. (2014) Activation of Intrinsic Immune Responses and Microglial Phagocytosis in an Ex Vivo Spinal Cord Slice Culture Model of West Nile Virus Infection. J. Virol 88, 13005–13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Savarin C et al. (2018) Distinct Gene Profiles of Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages and Microglia During Neurotropic Coronavirus-Induced Demyelination. Front. Immunol 9, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mangale V et al. (2020) Microglia influence host defense, disease, and repair following murine coronavirus infection of the central nervous system. Glia DOI: 10.1002/glia.23844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Syage AR et al. (2020) Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals the Diversity of the Immunological Landscape following Central Nervous System Infection by a Murine Coronavirus. J. Virol 94, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sariol A et al. (2020) Microglia depletion exacerbates demyelination and impairs remyelination in a neurotropic coronavirus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 117, 24464–24474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Poloni TE et al. (2021) COVID-19-related neuropathology and microglial activation in elderly with and without dementia. Brain Pathol. 31, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Al-Dalahmah O et al. (2020) Neuronophagia and microglial nodules in a SARS-CoV-2 patient with cerebellar hemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol. Commun 8, 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schwabenland M et al. (2021) Deep spatial profiling of human COVID-19 brains reveals neuroinflammation with distinct microanatomical microglia-T-cell interactions. Immunity 54, 1594–1610.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schurink B et al. (2020) Viral presence and immunopathology in patients with lethal COVID-19: a prospective autopsy cohort study. The Lancet Microbe 1, e290–e299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mondo E et al. (2020) A Developmental Analysis of Juxtavascular Microglia Dynamics and Interactions with the Vasculature. J. Neurosci 40, 6503–6521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Elmore MRP et al. (2014) Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron 82, 380–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dagher NN et al. (2015) Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibition prevents microglial plaque association and improves cognition in 3xTg-AD mice. J. Neuroinflammation 12, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]