Abstract

Classically, platelets have been described as the cellular blood component that mediates hemostasis and thrombosis. This important platelet function has received significant research attention for more than 150 years. The immune cell functions of platelets are much less appreciated. Platelets interact with and activate cells of all branches of immunity in response to pathogen exposures and infection, as well as in response to sterile tissue injury. In this review, we focus on innate immune mechanisms of platelet activation, platelet interactions with innate immune cells, as well as the intersection of platelets and adaptive immunity. The immune potential of platelets is dependent in part on their megakaryocyte (Mk) precursor providing them with the molecular composition to be first responders and immune sentinels in initiating and orchestrating coordinated pathogen immune responses. There is emerging evidence that extramedullary Mks may be immune differentiated compared to bone marrow Mks, but the physiologic relevance of immunophenotypic differences are just beginning to be explored. These concepts are also discussed in this review. The immune functions of the Mk/Platelet lineage have likely evolved to coordinate the need to repair a vascular breach with the simultaneous need to induce an immune response that may limit pathogen invasion once the blood is exposed to an external environment.

Keywords: Platelets, Immunity, TLR, Complement, NOD, CLR, FcR, Megakaryocytes, MHC

Introduction

Platelets are the second most abundant blood component after red blood cells, and once released into the circulation, they circulate for 7–10 days.1 Platelets are anucleate cell fragments generated by their bone marrow precursors, megakaryocytes, and their size varies from 2–5 μm in healthy humans.1, 2 Platelets are pre-packaged with many proteins and molecules that enable them to quickly respond to stimuli, bypassing transcription and translation. These proteins and molecules are stored in one of three types of granules: α (contain proteins), δ or dense (contain small molecules such as serotonin, ATP, ADP, and Ca2+), and lysosomes (contain enzymes and proteins appropriate for this cell compartment). Platelets are not a homogeneous population:3, 4 Platelet content varies according to their size, with smaller platelets carrying more inflammatory transcripts than larger platelets in healthy humans.3, 4 During infection, antiviral proteins are elevated in platelets5, 6, a response that is initiated by megakaryocytes.5 During infection, and in response to direct pathogen activation, platelets also release extracellular vesicles7–10 leading to smaller platelets that may be enriched in inflammatory/immune related contents.

In this review, we will discuss the major immune defense systems by which platelets detect pathogens. We will also describe how platelets interact and activate both the innate and adaptive immune systems, focusing on platelet immune functions.

Platelets and Innate Immune Responses

Two major systems related to innate immunity have evolved in the circulation to mediate pathogen responses. The first system is exclusively cell based and composed of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize and initiate a response to microbial components, either extracellular or intracellular.11 In platelets, these are the Toll-like receptors (TLR1–10 in humans), the nucleotide-binding domain leucine-rich repeat-containing (NOD-like) receptors (NLRs) and the C-type lectin receptors (CLR). Human platelets contain all ten TLRs8, 12, 13 and their transcripts are expressed at higher levels in platelets from women than men.13 TLR transcripts in women’s platelets also associate with serum P-selectin concentration, while TLRs in platelets from men are associated with other inflammatory markers present in serum (soluble tumor necrosis factor-α receptor 1 and intracellular cell adhesion molecule 1).13 Although many of the transcripts for the NLR receptors (NOD1, NOD2, NLRC3–4, NLRP1–9, etc.)14 can be detected in platelets8, 12 only NOD215 has been described to have a platelet function. Similarly, from the various known CLRs, platelets express functional DC-SING and CLEC-2. The second system, the complement system, is activated directly in the circulation and is a system of more than 30 proteins located in plasma.16 The ultimate goal of both of these systems is pathogen recognition and the induction of defense responses that will ultimately lead to pathogen destruction and clearance.

Platelets and Toll-like Receptors

The ultimate goal of the TLR system is to increase cytokine production, induce antigen presentation, and activate adaptive immunity. The surface TLRs (TLR2, TLR4 and TLR5) recognize surface components of pathogens while endosomal TLRs (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9) recognize pathogen nucleic acids. TLR10 is a surface TLR, but, contrary to other TLRs, it suppresses inflammatory signaling on primary immune cells.17 All TLRs form an m-shaped homodimer as a result of ligand binding to induce a response, with the exception of TLR2 which forms a heterodimer. TLR2 signals in combination with either TLR1 or TLR6 to form a functional TLR2 complex. There is also evidence that TLR2 may form a dimer with TLR10, although TLR2-TLR10 fails to initiate typical TLR-induced signaling.

Platelet-TLR4

TLR4 was the first TLR described to be present and functional in platelets (Fig 1 and Fig 2).14, 18 TLR4 can be activated by liposaccharide (LPS) components expressed mostly on gram-negative bacteria, in addition to multiple molecules present in plasma such as oxidized low density lipoprotein (LDL), certain viral components, cleaved fibrinogen, components of fibronectin, beta-defensin, high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1), S100A8 (calgranulin A), heparin sulfate proteoglycan and many more.11 In order for TLR4 to recognize LPS it requires cofactors such as CD14, MD-2 and MyD88 that are expressed by platelets11, although plasma soluble CD14 may be necessary for LPS induced platelet secretion.19 20 LPS activation of platelet-TLR4 has been most studied12, 20, 21 but more recent work has shown HMGB1 immune signaling to also function through TLR4.22

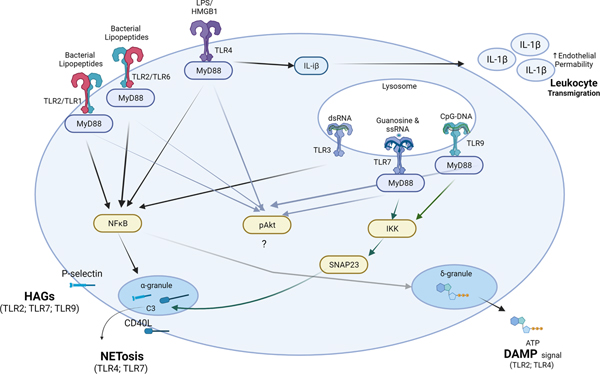

Figure 1: Platelet-TLRs and their contribution to the innate immune response.

Activation of platelet-TLRs induces fast release or surface expression of prepackaged proteins or molecules stored in platelet granules. Surface expression of P-selectin (or CD40L, in some cases) leads to interaction, in the form of heterotypic aggregates (HAGs) with neutrophils and monocytes; HAGs are important for leukocyte activation and tissue transmigration. Platelets can also mediate (TLR7-complement C3 axis) or accelerate (TLR4) the process of NETosis through their TLRs either by direct or indirect interaction with neutrophils. CD40L-CD40 axis may also be involved in NETosis. Activation of platelet-TLR4 can also deliver IL-1β to the vasculature, increasing endothelial permeability and consequently coordinating leukocyte migration in infected or damaged tissues. Finally, TLR-mediated release of ATP or HMGB1 from platelets can serve as a danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signal that can alert the leukocytes to the infection, promote inflammation and tissue transmigration, and mediate regeneration.

TLR-toll-like receptors; LPS-liposaccharide; HMGB-1; dsRNA-double stranded RNA; ssRNA-single stranded RNA; CpG-DNA- unmethylated 5’—C—phosphate—G—3’ oligonucleotides (DNA). (Illustration Credit: Ben Smith)

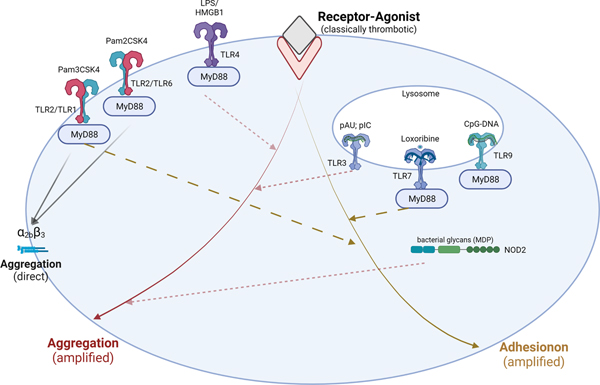

Figure 2: Platelet TLRs and NODs mostly contribute to thrombosis by amplifying thrombotic signals.

In addition to their interactions with leukocytes, activation of platelet pattern-recognition receptors can also amplify signaling mediated by classically strong (IIa, collagen, AA) or weak platelet agonists (ADP) that lead to platelet aggregation. It is important to acknowledge that pattern-recognition receptors related to sensing bacterial pathogens such as TLR2 are more likely to have direct prothrombotic implications. Activation of platelet thrombotic, adhesive and immune responses in cases of bacteria sensing may be necessary for proper coordination of containing and confining the pathogen while simultaneously inducing activation of innate immune recruitment. Of note, carboxy (alkylpyrrole) protein adducts (CAP) generated during chronic oxidative stress can utilize platelet TLR9 and lead to aggregation in vitro and thrombosis in vivo. TLR9 activation by microbial DNA however is not prothrombotic.

TLR-toll-like receptors; LPS-liposaccharide; NOD2-nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 receptor; MDP-muramyl dipeptide; IIa-thrombin; AA-arachidonic acid; pAU- Polyadenylic–polyuridylic acid (dsRNA); pIC- Polyinosylic–polycitosinylic acid (dsRNA); Loxoribine- modified guanosine analog; CpG ODN- unmethylated 5’—C—phosphate—G—3’ oligonucleotides (DNA). (Illustration Credit: Ben Smith)

Somewhat contradictory LPS induced platelet activation results have been reported that may be dependent on the purity and origin of LPS and the experimental design. Some studies report that LPS-TLR4 signals through MyD8820, ultimately resulting in degranulation. Other studies were not able to detect α-granule release as a function of LPS stimulation and reported a lack of either P-selectin23, 24 or CD40L17, 24 surface expression (Fig 1). LPS by itself does not induce platelet aggregation through TLR4, but is able to amplify platelet aggregation caused by collagen,20, 25 ADP,25 thromboxane,21 or thrombin20, 24 or in combination with collagen related peptide (CRP-XL)21 (Fig. 2). Platelet-TLR4 stimulation may lead to fibrinogen binding21 and, therefore, increased adhesion,14 as well as increased mitochondrial respiration,23 H2O2 production,21 NOX2 activation,25 TxA2 and eicosanoid production (8-iso-PGF2a-III)25.

There are a few signaling pathways that may be involved in platelet activation as a function of TLR4 stimulation. P-selectin surface expression and ATP release may be dependent on MyD88-PKG-cGMP signaling20, while Von Willebrand Factor (VWF) release, thrombin-induced aggregation, fibrinogen binding and ATP secretion have been reported as a function of NF-κB p65 activation.24 H2O2 production, NOX2 activation, PLA2 phosphorylation, TxA2 and 8-iso-PGF2a-III over-production have all been reported to be a function of pAKT, p38, and p47phox translocation.25 LPS induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and TxA2 are also described to be dependent on TLR4-PI3K-Akt-ERK1/2-PLA2 signaling.21 It is important to mention that platelet-released ATP through the P2X receptor can lead to platelet shape change but not to aggregation. Once released from platelets, cytosolic ATP also has the potential to act as a danger associated molecular pattern (DAMP) signal.26 DAMPs serve as a danger signal, stimulate inflammation and promote tissue regeneration. ATP acting as a DAMP recruits macrophages and contributes to inflammasome activation in leukocytes consequently increasing IL-1b release. 26 Thus, ATP released from platelets can contribute to the overall platelet-mediated immune response.

Activation of platelet-TLR4 with LPS may also lead to IL-1β release.7 At baseline, platelets from healthy donors do not express IL-1β protein, but do contain the IL-1β mRNA incorporated in polysomes.27 IL-1β mRNA is one of the few hundred RNAs known to undergo protein translation in platelets.27 Stimulation with LPS leads to IL-1β mRNA translation, Caspase-1-mediated processing, and release of IL-1β (Fig 1). It has been proposed that TLR4-signaling-mediated IL-1β release from platelets is exclusively by microparticle (MP) formation.7 IL-1β processing and IL-1β-MP release requires MyD88 and TIRAP, as well as IRAK1/4, Akt, and JNK activation.7 LPS-generated platelet MPs activate endothelial cells7 and IL-1β increased endothelial activation and endothelial barrier permeability. The ability of platelets to generate and release IL-1β as a function of TLR4, suggests that in the settings of infection, platelets regulate endothelial barrier integrity allowing for other immune cells to enter the tissue and contain, confine, and initiate pathogen responses.

Despite the unsettled outcomes and unclear mechanisms of LPS-mediated platelet pro-thrombotic function, in vivo studies have indicated that platelet-TLR4 signaling may lead to activation of the innate immune cell systems. In vivo stimulation of platelet-TLR4 with LPS leads to platelet-neutrophil binding, neutrophil activation, and stimulates neutrophils to release their DNA in a process termed NETosis.28

In addition to LPS, platelet-TLR4 can be activated by HMGB1, a major danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecule that contributes to innate immune responses.29 HMGB1 belongs to the high mobility group (HMG) family of DNA-binding proteins that can be found in the nucleus and cytoplasm.29 Platelets contain HMGB1 and, with activation, HMGB1 is found on the platelet surface.15 Platelets can undergo necroptosis and contain the machinery necessary to mediate pyroptosis, and HMGB1 is released from cells that undergo these processes. 8, 29 HMGB1-mediated TLR4 activation leads to platelet granule secretion and increased fibrinogen and collagen adhesion.24 HMGB1 relays platelet activation signaling through MyD88 and PKG, ultimately contributing to thrombosis (Fig. 2).24 Finally, platelet-derived HMGB1 contributes to increased NETosis in a TLR4-dependent manner.24

Platelet-TLR2

TLR2 recognizes and becomes activated by lipoprotein components of gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria, and can recognize the surface coat of some viruses, such as dengue,30 measles,31 cytomegalovirus (CMV)32 and SARS-CoV-2.33 Platelets have a functional TLR2, and synthetic ligands such as Pam3CSK4 have contributed to our understanding of the contribution of platelet-TLR2 to immunity and thrombosis.

Contrary to TLR4, activation of TLR2/TLR1 with Pam3CSK4 is directly pro-thrombotic,34 but similar to TLR4, stimulation of TLR2/TLR1 leads to increased collagen adhesion (Fig. 2).34 TLR2/TLR1 activation results in increased P-selectin and CD40L surface expression, and as a result, platelet-neutrophil heterotypic aggregate (HAG) formation, and α2bβ3 activation that may explain the increased direct aggregation (Fig. 1).34 Platelet-neutrophil HAGs are also increased in a TLR2-dependent manner after in vivo infection with P. gingivalis.34 The effects of α-granule release, platelet adhesion and platelet-leukocyte HAGs are mediated in a PI3K-Akt-, pERK-p38- and NF-κB-dependent manner.

Platelet TLR2/TLR6 activation by Pam2CSK4 also leads to α-granule release (P-selectin and TLT1 surface expression), δ-granule secretion (ATP) and α2bβ3 activation (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).35 Similar to TLR2/TLR1, TLR2/TLR6 activation results in increased platelet aggregation and adhesion to collagen.35 Platelet activation responses to Pam2CSK4 are mediated through NF-κB, Bruton tyrosine kinase activation and ADP feedback loop.35 Although interaction with leukocytes has not been described to date, Pam2CSK4 mediates increased interaction between platelets and endothelial cells.35

In vivo studies have also shown that activation of TLR2 by gram-negative bacteria during infection with P. gingivalis-mediated platelet-neutrophil aggregates.34 Independent of infection, during hyperlipidemic states, in vivo activation of TLR2-TLR6 can also form a complex with CD36 and mediates increased thrombosis by oxidized phospholipids.36 Complex formation between TLR2 with surface integrins such as CD36 suggest that recognition and signaling in platelets may involve much more combinatory interactions then just one ligand at a time.

Endosomal TLRs

Platelets express the transcripts for all endosomal TLRs.11, 13, 37 Endosomal TLRs recognize pathogen nucleic acids that have been internalized into endosomes.11 Endosomal TLRs require the acidic pH of the endosome/lysosome compartment for proper activation and signaling. Functional studies have outlined the role of platelet-TLR737–39 and TLR939–41 in immunity and thrombosis, while the role of TLR3 and TLR8 are less understood. When it comes to TLR8, differences in human and murine TLR842 have hindered our understanding of this receptor’s in vivo function.

Platelet-TLR9

TLR9 recognizes unmethylated 2’-deoxyribose cytidine-phosphate-guanosine (CpG) motifs that are present in microbial and mitochondrial DNA, but not mammalian DNA.43 Platelet-TLR9 has been described inside of platelets and on the surface, similar to other cells.18, 41 Proper activation and signaling of TLR9 by CpG-motifs requires an acidic endosomal pH,43 and this is true for platelets.39 TLR9 activation by synthetic CpG leads to α- and δ-granule exocytosis that results in platelet-leukocyte aggregates.39 TLR9 signaling requires MyD88 and leads to Akt and IKK activation while granule release is mediated via the MyD88-IRAK1/4-IKKb-SNAP23 pathway (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).39 Although TLR9 mediates platelet interactions with monocytes and neutrophils, stimulation with type C CpG does not have a direct pro-adhesion/pro-aggregation effect on collagen coated slides when compared to control.41 Platelets from acute coronary syndrome patients have been reported to have significantly elevated expression of TLR and increased granule release in response to ODN2006-mediated TLR9 stimulation.44 Additionally, studies using carboxy (alkylpyrrole) protein (CAP) adducts, an altered-self ligand generated during oxidative stress, with elevated plasma levels in diabetes and atherosclerosis.40 CAPs increased P-selectin40 surface expression and α2bβ340 activation in vitro and increased thrombosis in vivo in a TLR9-MyD88-dependent manner.40 It is unclear, however, if the effect of CAPs on thrombosis is due to direct activation of TLR9 or contribution to its signaling. These observations suggest that depending on environmental cues, agonist specificity, and levels of TLR9 expression, platelet-TLR9 can mediate an innate immune response and may contribute to thrombosis in certain chronic conditions.

Platelet-TLR7

TLR7 and TLR8 (in humans) are receptors for single-stranded viral RNA. TLR7 is a receptor with two activation sites, one for guanosine or guanosine analogs and one for uridine-rich single-stranded RNA.45, 46 In the absence of ligands, TLR7 exists as a monomer. Guanosine and uridine-rich single-stranded RNA induces TLR7-monomer dimerization and consequently signaling activation.46 Guanosine and its derivatives are sufficient and essential to induce dimerization and signaling without requiring a ligand at the second site, defining TLR7 as a guanosine receptor.46 The second site occupied by at least three uridine stretches in the single-stranded RNA only contributes to the activation of TLR7.45, 46 It is important to mention that antiphospholipid antibodies, underlining pathologies of various immune disease states associated with increased blood clotting, have the ability to increase the expression and sensitization of TLR7.47

Platelets express functional TLR7 in their endosomal/lysosomal compartments (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).37–39 Activation of platelet-TLR7 in human platelets leads to α-granule secretion and with it, increased surface P-selectin38, 39 and CD40L38 expression, which mediates the formation of HAGs with leukocytes,38, 39 especially neutrophils (Fig. 1).38 Consistent with lack of α2bβ3 activation, washed human platelets does not aggregate in the presence of guanosine analog stimulation (loxoribine or R838)38, but TLR7 does mediate increased collagen adhesion.38 Contrary to human platelets, murine platelets have detectable TLR7-mediated α2bβ3 surface activation.39 This is not surprising, as activation of murine TLR7 is different than human TLR7. Murine TLR7 can be activated by agonists for both human TLR7 and TLR8,42 and expression in murine platelets is almost doubled at the transcript level in mice compared to human platelets.38 Studies utilizing murine platelets also have shown that activation of platelet-TLR7 by the guanosine analog, loxoribine, leads to the secretion of all platelet granules.39 Activation of murine platelet-TLR7 by guanosine analog or HIV-RNA increases the release of PF4 from α-granules, serotonin from δ-granules and β-hexosaminidase from lysosomes.39 Activation of TLR7 leads to Akt38, 39 and p38-MAPK38 phosphorylation as well as IKK39 activation and granule release is mediated via the MyD88-IRAK1/4-IKKb-SNAP23 pathway (Fig. 1).39

In vivo murine studies have shown that TLR7 activation with loxoribine or infection with a single-stranded RNA virus such as Encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) leads to a transient, mild thrombocytopenia.38 Platelet-TLR7 also contributes to the survival of mice during EMCV infection.38 Mild thrombocytopenia occurs at 2 and 24h post infection and coincides with HAG formation with neutrophils and internalization of platelet content by these cells.38 Platelet-TLR7 also mediates increased NETosis at 24h post stimulation.37 The mechanism of platelet-TLR7 initiated NETosis involves the release of complement C3 (discussed below)37 and activation of the complement cascade (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). In the presence of platelets and stimulation of platelet-TLR7, neutrophils release their DNA directly into the circulation without the need for tethering to the vessel wall.37 Additionally, since neutrophils do not express TLR7, platelet-TLR7 seems to be able to mediate NETosis at early phases of infection.37

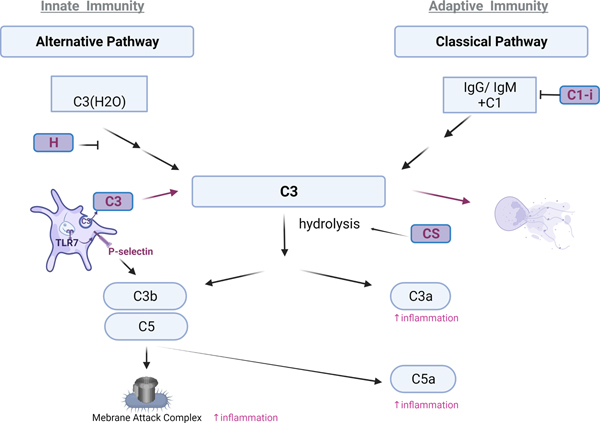

Figure 3: Platelets complement the Complement response, bringing TLRs and Complement together.

Platelets contain various molecules that either initiate (C3) and amplify (Factor H, condroitin sulfate (CS)) or inhibit (C1-i) the complement cascade. The alternative pathway is activated by spontaneous hydrolysis of complement C3 that is stabilized by pathogen surfaces and properdin and is amplified by complement factor B and D, or inhibited by complement factor H and I. P-selectin on platelets can bind and activate C3b, further supporting the activation of the complement system during innate immune response. The classical pathway is initiated by antibody complexes IgM and IgG as well as apoptotic surfaces. During infection with viruses such as influenza, platelets can mediate a crosstalk between TLRs and complement in the circulation by releasing C3 from their granules as a function of TLR7 activation. Platelet C3a receptor-increases platelet adhesion, spreading and Ca2+ influx and platelet-C5aR-inhibits angiogenesis by inhibiting endothelial function through PF4. The ultimate function of the membrane attack complex, composed of C5b-C6-C7-C8-C9 is to lyse a pathogen (bacteria) or pathogen infected cells (virus). All factors in purple come from platelets. (Created in: BioRender)

Overall, activation of platelet-TLR7 may provide a crosslink between immunothrombosis and complement activation, without directly affecting platelet aggregation. This function of platelet-TLR7 may ensure proper communication and activation of the immune system by platelets without adhering in a thrombus.

Platelet-TLR8

TLR8 is the other endosomal receptor in human cells that recognizes single-stranded viral or bacterial RNA. Contrary to TLR7, TLR8 exists as a dimer in the absence of ligand.45, 48 Upon ligand binding, requiring an endosomal pH, conformational changes induce activation.48 Similar to TLR7, TLR8 is a dual receptor with two distinct activation sites that require binding of uridine and guanosine rich single-stranded RNA and both of the sites are essential for its activation.48 Although mice have TLR8, murine TLR8 is not activated in the same way with the same ligands as human TLR8, hindering our understanding of TLR8 in vivo. Some platelets carry the transcripts for TLR8, although not all individuals have detectable levels.13 Expression of platelet-TLR8 associates with hypertension, increased serum levels of TNFR and mildly with body mass index in Framingham Heart Study participants (n=1625, visit 8).13 It has been proposed that the fungal-derived circulating polysaccharide, chitin, can interact with platelets through TLR8,49 but it is unclear if the described platelet-inhibition phenomenon is via direct interaction with this platelet TLR.49 Overall, the role of platelet-TLR8 activation, when it comes to immunity and thrombosis, needs further investigation.

Platelet-TLR3

TLR3 is activated by double-stranded microbial RNA, often generated as a result of transcription of microbial genes, and it is also an endosomal receptor. Transcript levels of platelet-TLR3 seems to vary in human platelets.13, 44 Activation of platelet-TLR3 using poly I:C or poly A:U does not lead to P-selectin or CD40L surface expression, but it does result in ATP release (Fig. 1 and Table 1).50 Incubation of platelets with a high concentration of poly I:C or poly A:U results in amplification of arachidonic acid, ADP, or collagen induced aggregation.50, 51 Agonist stimulation using poly I:C or poly A:U leads to increased activation of the NF-κB, PI3K-Akt and ERK1/2 pathways in platelets.48 Additional studies are necessary to elucidate the roles for platelet-TLR3 in vivo.

Table 1.

Platelet-Pathogen Recognition Receptors (PRR) and their functions related to immunity and thrombosis

| Location & type | Receptor | Signaling complex | Pathogen | Ligand | Signaling | Outcome | Immunity | Thrombosis | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Toll-like receptor |

TLR2 | TLR2-TLR1 | Gram negative (P. gingivitis) Surface components of dengue; measles; CMV; SARS-CoV-2 |

Pam3CSK4 | PI3K; pERK-p38; NF-kB | P-selectin; CD40L; α2bβ3 | HAGs with neutrophils and Netosis | Direct increase of aggregation; Increased adhesion on collagen | 24, 34 |

| TLR2-TLR6 | Pam2CSK4 | NF-kB; Burton kinase-ADP feedback loop | P-selectin; TLT1; α2bβ3; ATP-release |

? | increased aggregation and adhesion in presence of collagen | 35 | |||

| TLR2-TLR6-CD36 | oxPL (KODA-PC) |

MyD88-IRAK1,4-TRAF6; Src/Syk-PLCy | P-selectin; α2bβ3; | ? | Increased thrombosis in vivo during hyperlipidemia | 36 | |||

| Surface Toll-like receptor |

TLR4 | TLR4-TLR4 complexed with CD14 and MD-2 | Gram positive bacteria; oxLDL; cleaved FgN; fibronectin; S100A8; heparan sulfate | LPS | MyD88-cGMP-PKG; PI3K-Akt-Erk1/2-PLA2; pAKT, p38, and p47phox translocation; NF-kB; JNK | P-selectin; ATP; vWF ROS; TxA H2O2 production, NOX2 activation, PLA2 phosphorylation, TxA2 and 8-iso-PGF2a-III over-production; IL-1b-microparticles |

HAGs with neutrophils and monocytes | increased aggregation in presence of IIa, collagen, ADP, TxA | 7, 20, 21, 24, 25 |

| LPS | No P-selectin; no CD40L | Netosis | 14, 23, 24, 28 | ||||||

| HMGB1 (DAMP) | MyD88-cGMP-PKG; | P-selectin; ATP; | Netosis | Increased adhesion on collagen | 22 | ||||

| Endosomal/lysosomal compartment Toll-like receptor |

TLR3 | TLR3-TLR3 | Double stranded microbial RNA | pIC; pAU | NF-kB, PI3K-Akt; pErk1/2 | Liver netosis (high agonist concentration) | Increased aggregation in presence of arachidonic acid, ADP, or collagen induced aggregation (high agonist concentration) | 50, 51 | |

| Endosomal/lysosomal compartment Toll-like receptor |

TLR7 | TLR7-TLR7 | Dual receptor for Guanosine & Single stranded RNA (U-rich) Viruses: EMCV; influenza |

Loxoribine, R837 at low concentration), R848 (where there is no TLR8) | p38; Akt; MyD88-IRAK1/4-IKKb-SNAP23; | P-selectin CD40L C3; PF4 & HEX - release α2bβ3 (mice only) |

HAGs with neutrophils; mediate complement release and consequently netosis; | Increased adhesion on collagen without directly mediating aggregation | 37–39 |

| Endosomal/lysosomal compartment Toll-like receptor |

TLR9 | TLR9-TLR9 | Microbial DNA; mitochondrial DNA | CpG-DNA | MyD88-IRAK1/4-IKKb-SNAP23; Akt | P-selectin; α2bβ3 (mice); PF4 & HEX release |

HAGs with neutrophils and monocytes | Increased adhesion or aggregation in presence of collagen | 39–41 |

| CAP | MyD88-IRAK1/Akt Src kinase | P-selectin α2bβ3; | ? | Increased thrombosis in vivo | 40 | ||||

| Cytoplasm Nucleotide binding oligomerization domain receptor | NOD2 | Cytoplasmic content of any bacteria | MDP | MAPK and cGMP/PKG pathways | ATP (in presence of collagen) | ? | Increased aggregation in presence of collagen Accelerated thrombosis in vivo |

56, 57 | |

| Surface C-type lectin receptor |

DC-SIGN | HIV-1; Dengue many bacteria | HIV-1 Dengue | ? | P-selectin (Dengue) | ? | Not known | 59, 60 | |

| Surface C-type lectin receptor |

CLEC-2 | HIV-1 | Rhodocytin; podoplanin; S100A13 hemin | Src, Syk, and PLCγ | ? | ? | Increased thrombosis | 55–6060–63, 65 |

P-selectin and CD40L in this table indicate surface expression and α2bβ3 indicates activation. All endosomal TLRs require acidic pH for proper signaling. R838- can activate adenosine receptors and should at high concentrations; R848-can activate both TLR7 and TLR8 and is useful for TLR7 activation when there is no expression of TLR8.

The following abbreviations were used throughout: MDP- muramyl dipeptide; HEX- β-hexosaminidase; CAP-carboxyl (alkylpyrole) protein; EMCV-Encephalomyocarditis virus;

Overall, platelet-TLR activation initiates an innate immune response during infection through various mechanisms, including DAMP release and shortening the time to NETosis (TLR4) or solely mediating the process (TLR7). The contribution of platelet-TLRs to thrombosis is not direct and is manifested mostly in the presence of other platelet prothrombotic agonists, further highlighting the fact that there is a population of platelets dedicated to immunity.

Platelet-NOD1 and -NOD2

Nucleotide binding oligomerization domain receptors (NOD) 1 and 2 are also pattern recognition receptors, but contrary to the TLR family, they are expressed in the cytoplasm.52 The NOD receptors detect peptidoglycan components derived from the cell wall of bacteria and provide defense against pathogen invasion rather than initial detection.52 NOD1 becomes activated as a result of γ-d-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP), while NOD2 senses the shorter fragment, muramyl dipeptide (MDP). In that sense, NOD1 responds specifically to gram-negative and some gram-positive-bacteria while NOD2 detects the cytoplasmic presence of any bacteria.52 It has been proposed that TLRs and NOD receptors play redundant roles in the detection of bacterial pathogens and immune activation.53, 54 Platelets express both NOD18, 55 and NOD28, 55, 56 and interestingly NOD1 transcripts are upregulated in patients with COVID-19 when compared to either healthy controls55 or non-infected myocardial infarction patients.8 The role of platelet-NOD1 has not been elucidated to date, and limited data is available for platelet-NOD2 immune functions, but NOD2 activation by MDP increases platelet aggregation and ATP release in the presence of thrombin or collagen in vitro and accelerates thrombus formation in vivo (Fig. 2; Table 1).56 Inhibition of NOD2 by GSK669, reduces collagen-mediated platelet aggregation, ATP release, and ROS generation and decreases thrombus formation using the same model.57 NOD2 signaling in platelets may involve activation of MAPK and cGMP/PKG pathways.56 MDP also induces the maturation and accumulation of IL-1β in human and mouse platelets.56 Further studies are necessary to assess the contribution of platelet NOD1 and NOD2 to immune cell activation and inflammation.

Platelet-CLRs

C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) are expressed on the cell surface and participate in immune responses to pathogens. CLRs recognize carbohydrate residues on the pathogen surface and can crosstalk with TLRs in dendritic cells.58 Of the various described CLRs, platelets express functional DC-SIGN (CD209) and CLEC-2. DC-SIGN can interact with pathogens by recognizing high mannose and fucose levels on their surface. Platelets recognize and become activated by Dengue virus, at least partially, through DC-SIGN.59 Neutralizing antibodies against this CLR have shown to abrogate Dengue-mediated surface P-selectin expression.59 Platelets can also bind HIV-1 particles by utilizing DC-SIGN, although CLEC-2 seems to be the predominant CLR involved in HIV-1 binding.60 CLEC-2 on platelets can be potently activated by rhodocytin, a C-type lectin that is present as a toxin in snake venom, which leads to increased aggregation.61 Rhodocytin-CLEC-2 signaling in platelets involves Src, Syk, and PLCγ.62 Endogenous molecules such as podoplanin, S100A13 and hemin have also been identified as ligands for platelet CLEC-2 that ultimately lead to pro-thrombotic outcomes. 63–65 Further investigations are necessary to elucidate the contribution of platelet-CLRs in initiating and driving immune responses.

NETosis and Heterotypic Aggregates with Neutrophils and Monocytes

Platelets mediate the initial response to infections by alerting leukocytes such as neutrophils and monocytes to the presence of pathogens. Platelets can directly interact with and alter the behavior of these immune cells by forming heterotypic aggregates (HAGs) through the P-selectin/PSGL1 axis. Through P-selectin HAGs, platelets acutely activate and enhance neutrophil binding to immobilized fibrinogen and ICAM1 which are important for neutrophil activation and interstitial migration.66–68 The importance of platelet-neutrophil HAGs is demonstrated in models of murine lung injury, where inhibition of HAGs reduced neutrophil recruitment to the lung tissue and prolonged survival.68 Platelet-monocyte HAGs through P-selectin/PSGL1 lead to increased expression of CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1) on monocytes. 69 Consequently Mac-1 monocytic expression further amplifies the interaction of platelets with monocytes through α2bβ3 activation.69 Platelet-monocyte HAGs can also trigger monocyte tissue factor expression contributing to the overall immune-thrombotic response.70

Platelets also mediate or shorten the time to NETosis. NETosis is a process that results in the release of DNA from neutrophils in response to pathogen presence or inflammatory stimuli. The release of DNA from neutrophils in concert with platelets is important for capturing and removing bacteria or viral particles from the circulation.28, 71 Neutrophil DNA is coated with positively charged histones that are pro-thrombotic.71 In fact, pathogens such as Y. pestis have evolved to disaggregate platelets and evade ‘netting’ neutrophils.72 Although beneficial to pathogen responses, this process, when dysregulated, is a double-edged sword and can contribute to thrombotic events and unstable coronary syndrome. As previously noted, platelets through their TLR4 receptor are able to shorten the time of NETosis from hours to minutes.28 Platelets, through TLR7 mediate the level of NETosis by releasing complement C3 and further control its levels by elevating GM-CSF.37

Platelet defensins

Defensins are a family of antimicrobial peptides that are major contributors to innate pathogen immunity. Defensins are small, 2–5 kDa, positively-charged peptides stabilized by three conserved disulfide bonds.73 In humans, they are classified into two major groups, α (six members) and β (30 members).73 Defensins exert both antiviral and antibacterial properties and limit microbial invasion by interacting with Ca2+/Mg2+ and destabilizing microbial membranes.73 Alpha-defensins are expressed predominantly by neutrophils and Paneth cells, while β-defensins are expressed predominantly by epithelial cells.73 Platelets have detectable transcript levels of four α-defensins (DEFA1, A1B, A3, A4)8, 55 and two β-defensins (DEFB18, 74 and DEFB12455). Protein levels and functional properties of β-defensin 175 and α -defensin 176 have also been described in platelets. Alpha-defensin 1 localizes to platelet α-granules76 while β-defensin 1 is found in the platelet cytoplasm75. Stimulation of platelets with α-toxin derived from S. aureus, results in the release of β-defensin 1 independently of granule secretion.75 The release of platelet β-defensin 1 significantly impairs S. aureus growth and mediates robust NETosis from neutrophils that is necessary for capture and neutralization of the bacteria.75 Alpha-defensin 1 on the other hand is released from platelets that are stimulated with thrombin, ADP or LPS.76 The secreted α -defensin 1 is able to bind to the platelet surface and exert antimicrobial effects against E. coli.76 The presence of functional platelet defensins highlights the importance of platelets, not only in providing an innate immune function against foreign pathogens,75 but also in platelets as the circulating blood component that is first to encounter pathogens.

Platelets and the Complement System

The complement system enhances innate immune responses against foreign invaders.77 The complement cascade proceeds from the activation of pre-formed plasma proteins and functions to initiate and support phagocyte and antibody targeting of microbes or infected cells, the clearance of microbes and damaged cells, and to promote inflammation.77 The complement system is composed of more than 30 proteins made by the liver that circulate in their inactive form and become activated as a result of three different activation pathways.77 In the classical pathway, complement components are recruited and activated by complement activating antibody binding to a membrane surface.77 The lectin pathway becomes activated as a result of pathogen or infected cell carbohydrate binding, such as on apoptotic cells.77 The alternative pathway is activated by spontaneous hydrolysis of complement C3 that is amplified by complement factor B and D, or inhibited by complement factor H and I.77 In addition to these major mechanisms of activation as a function of pathogen exposure, the complement cascade can also be activated by non-pathogen mechanisms involving the contact coagulation cascade. Regardless of the mechanism of activation, all pathways converge at complement C3.77 Cleavage of complement C3 leads to the generation of two fragments, C3a and C3b. C3a promotes inflammation while C3b, also termed an opsonin, attaches to microbial or infected cell surfaces triggering lysis of those cells by enabling a formation of the membrane attack complex (puncturing the cell membrane) from downstream complement components (C5b-C6-C7-C8-C9).77

Platelets can activate, and become activated by, the complement system (Fig. 3). Platelets contain complement C378, C4a78, C1-inhibitor (C1-I)78, 79 and complement factor H80 in their α-granules, and can release complement factor H80, 81 and C1-inhibitor81 as a function of thrombin81 or collagen79 (C1-I) stimulation. C1-inhibitor inhibits the activation of the complement cascade by interacting with activated C1 components, relevant to the classical pathway of activation (Fig. 3).82 C1-inhibitor also inhibits coagulation factors XIIa and FXIa, providing a cross regulation between coagulation and the complement cascade.82 The major function of complement factor H is to prevent spontaneous activation of the alternative pathway by mediating dissociation of C3-convertase components inhibiting C3 hydrolysis and by enhancing cleavage of C3b thereby inhibiting downstream activation of the lytic pathway.80 Interestingly, coagulation factor XIa can cleave complement factor H, and consequently remove the brake on C3 activation and cascade stimulation.83 Regulation of complement by FXIa provides another link of cross regulation between coagulation and complement pathways. Platelets can also activate the classical pathway of the complement cascade on their surface84 linking innate and adaptive responses (Fig. 3). The classical pathway of complement activation on the platelet surface is supported by deposition of complement components C1q and C4d and consequent C4d and C3a generation.84

Platelets can also activate the alternative pathway of the complement cascade. Platelets secrete complement C3 from their granules in response to TLR7 or thrombin stimulation37 ultimately leading to NETosis that is impaired when C3 fragmentation is inhibited with compstatin.37 A possible mechanism of pushing spontaneous activation of C3 outside of platelets, could be through TLR7-mediated surface P-selectin expression.38, 39 Complement needs membrane surface molecules for activation and surface P-selectin may be a C3b-binding protein.85 It has also been demonstrated that the platelet glycosaminoglycan, chondroitin sulfate, is able to mediate spontaneous hydrolysis of C3 and consequently complement cascade activation (Fig. 3).86 Additional studies are necessary to elucidate which complement component mediates NETosis as a function of platelet-TLR7-C3 release, but it is clear that platelets are responsible for the increased complement C3 levels in influenza infection.

Platelets also interact with and respond to activated components of the complement cascade. During blood-borne bacterial infections platelet GPIb interacts with C3b-coated bacteria to mediate pathogen clearance and immune activation.87 Platelets also can be activated by the classical or alternative pathways of complement activation.88 Activation of the C3a receptor increases platelet adhesion to fibrinogen under shear stress and increases ADP-mediated platelet aggregation. The platelet molecular signaling pathway downstream of C3aR involves phosphorylation of PI3Kβ and the consequent activation of Rab1b.89 Platelets from patients with coronary artery diseases show strong positive correlation of platelet complement C3aR expression with activated α2bβ3. Thrombi obtained from patients with myocardial infarction also show co-expression of C3aR with α2bβ3.90 Thus the C3a/C3aR axis on platelets demonstrates a distinct regulation of thrombus formation that involves platelet adhesion, spreading, and Ca2+ influx.90 Platelets can also be activated through the C5a/C5aR axis and C5a activated platelets inhibit endothelial migration and tube formation.91 Mechanistically, C5aR-activated platelets exert their anti-angiogenic activity on endothelial cells through PF4 secretion.91 Lack of C5aR on platelets allows for more collateral artery formation and pericyte coverage.91 It has been proposed that the insertion of the C5b-C9 complex in the platelet membrane can trigger platelet-MP formation and release.92, 93 Platelets bridge the effects of TLR, complement, and coagulation systems, providing a first line for coordinated responses to foreign invaders. These responses, when dysregulated, could clearly have a pathological impact on the host.

Platelet Fc Receptor

Human, but not mouse, platelets express the low affinity receptor for the constant fragment (Fc) of immunoglobulin (Ig), FcγRIIa. While antibody-mediated thrombocytopenia is not dependent on the internal signaling FcR γ-chain,94 IgG immune complexes can trigger platelet integrin activation and granule secretion in a FcγRIIa internal domain signaling-dependent manner. Many of the initial studies of platelet FcγRIIa focused on its role in heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP).95 More recently an appreciation for the role of FcγRIIa in platelet immune functions and immune dysregulation has emerged. Immune complexes are noted in RNA virus mediated infectious diseases such as influenza or SARS-CoV-2. In influenza infection, H1N1 virus scaffolds with IgG to form immune complexes that promote platelet activation (Fig. 4).10 In COVID-19, IgG and SARS-CoV-2 scaffolds and in the presence of dysregulated glycosylation these immune complexes may contribute to platelet adhesion to endothelial cells and increased thrombus size (Fig. 4).96 Immune complex platelet activation via FcγRIIa is also a feature of autoimmune diseases such as lupus that may accelerate end organ lesions97 and immune complexes can lead to transient platelet margination and systemic shock in a platelet derived serotonin-dependent manner.98

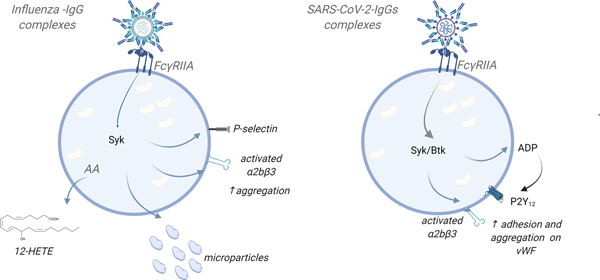

Figure 4: Human platelet FcγRIIa mediates a response to immunocomplexes in the circulation.

FcγRIIa is the activating IgG Fc receptor. IgG immune complexes can trigger platelet integrin activation and granule secretion in a FcγRIIa ITAM- signaling-dependent manner, increasing platelet prothrombotic response. Different IgGs for different pathogens may also exhibit different response on platelets. Of note, IgGs for anti-spike SARS-CoV-2 have to be attached to VWF on endothelial cells in order to induce adhesion/aggregation response of platelets.

AA-arachidonic acid; ITAM- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif on the FcR; vWF-von Willebrand Factor (Created in: BioRender)

Overall, depending on the IgG and the environmental stimuli as a result of infection severity, activation of FcγRIIa by IgG immune complexes may contribute to the prothrombotic potential of platelets.

Platelets and Adaptive Immune Responses

Platelets have multiple indirect and direct effects on adaptive immunity. Our knowledge in this area of platelet-immune cell intersection is much less than our understanding of innate immune interactions, but may include roles for platelets in acquired immune cell trafficking, adaptive immune cell maturation and differentiation, and effects on antigen presenting cell (APC) maturation and T-cell stimulation. The goal of this section is to introduce these concepts and point to areas of future research need.

Antigen presentation to T-cells, and T-cell activation, is described to occur in lymph tissues, such as lymph nodes, and more recently lung derived antigen presenting cells have been shown to also migrate to the spleen to present antigen to T cells 99. Getting immune cells to the site of tissue injury, the site of pathogen exposure, and sites of antigen presentation at the proper time and context are key steps in the adaptive responses to tissue injury and infection. Like all immune cells, T-cells must receive signals and cues to inform their trafficking, including the binding of T-cells to lymph node high endothelial venules (HEV) so they can enter the lymph node as an early event in antigen specific responses. Activated platelets bind to circulating lymphocytes and help to mediate T-cell rolling in HEVs in a platelet P-selectin-dependent manner.100 Activated platelets were also shown in vitro to enhance the tethering of lymphocytes and sustain their rolling on HEVs 101. Platelets may be important in adaptive immune cell tissue localization. For example, platelet activation was necessary for the accumulation of virus-specific CD8+ T-cells to the liver in a hepatitis model.102 Using both models of cerebral malaria and skin transplantation, we have shown that platelets, and platelet derived immune mediators, recruit T-cells to sites of inflammation and that can drive the tissue injury and associated neurocognitive decline and transplant rejection.103–107 This included PF4 mediated CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell cerebral vascular localization in experimental cerebral malaria (ECM). Platelets therefore accelerate the T-cell-dependent cerebral vascular injury and blood brain barrier (BBB) loss that underlies the disease pathogenesis. Similarly, in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), experimental autoimmune encephalitis (EAE), platelets were found in the brain tissue itself, likely secondary to BBB loss108. Antibody mediated platelet reduction was separately shown to reduce antigen specific CD4+ accumulation and alleviate anxiety like behavior in the EAE mouse model 109. Neurocognitive deficits may result in part from platelets sustaining the recruitment of antigen specific T-cells. While circulating platelet and T-cell aggregates have been identified in many disease conditions 110–112, direct platelet recruitment of T-cells at the vascular interface to sites of inflammation is thus far largely just implied, and how platelets may support T-cell tissue trafficking is not well defined and in need of further investigation.

T-cells are broadly classified as CD8+ cytolytic T-cells, or CD4+ T helper cells. CD4+ T-cells are further classified based on the cytokines they secrete as Th1 (example, IFNγ secretion), Th2 (IL-4 secretion), or Th17 (IL-17 secretion) effector T-cells, or as T regulatory (Treg) cells that have immune reparative functions (secrete TGFβ and IL-10). CD4+ T-cell differentiation is driven by the cytokine environment at the time and site of their activation, but T helper cell differentiation is somewhat fluid and plastic in nature – effector T cell phenotype is not absolute, but can be pushed to another phenotype by the cytokine and tissue environment 113, 114. Because platelets are major sources for plasma cytokines and chemokines, platelets can have roles in mediating T helper cell differentiation (Fig. 5). Human CD4+ T-cells in culture with platelets were shown to increase their production of cytokines that are typical of Th1 (IFNγ) and Th17 (IL-17) T-cell differentiation, but platelets had little effect on Th2 associated cytokines 115. Co-incubation with recombinant platelet derived proteins including PF4 and RANTES, enhanced both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production 116. These in vitro data showed that platelets exerted effects on T helper cell differentiation. Platelets as mediators of T helper cell differentiation has also been explored in vivo.107 Using a mouse model of chronic cardiac allograft rejection, platelet deficient (thrombopoietin receptor knockout mice) mice had a T helper skewing to more Th17 cells, fewer Th1 cells, and similar to in vitro studies, no difference in Th2 cells, compared to control transplant mice, that drove a more robust rejection response.107 These CD4+ phenotype skewing differences were also evident basally prior to any cardiac allograft. Mice lacking PF4 also had increased Th17 differentiation bias both in steady state and post cardiac transplantation conditions, demonstrating that platelets are in part mediators of T-helper cell homeostasis and differentiation that is at least in part PF4-dependent. These studies also demonstrated that the PF4 gene became expressed by activated CD4+ T-cells, but whether they make PF4 at detectable levels in vivo and the physiologic impact of activated T-cell PF4 is yet to be completely understood. This of course also raises the caveat of any Cre driver, that understanding potential off target effects must be taken into account.

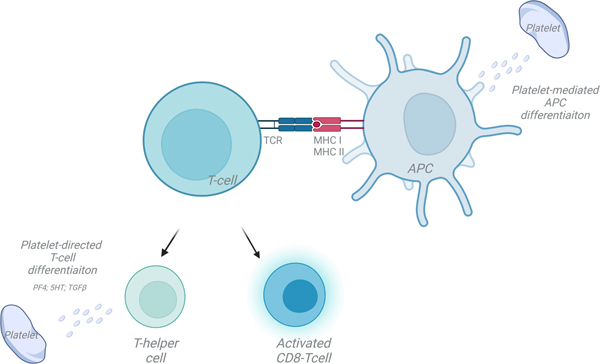

Figure 5: Platelets influence all steps in T cell activation and differentiation.

Platelets interact directly with T cells and regulate antigen presenting cell differentiation. Platelet derived mediators, such as PF4, serotonin (5HT) and TGFβ influence T-helper cell differentiation.

APC-antigen presenting cell; MHC-major histocompatibility complex; TCR-T-cell receptor. (Illustration Credit: Ben Smith)

In addition to T effectors, platelets can augment the activity and function of Tregs. In a bacterial lung infection and resolution model, platelets were shown to be both important in the acute neutrophil responses and in Treg cell driven injury resolution (Fig. 5).117 Prior study also demonstrated improved T reg function with TPO treatment in chronic immune mediated thrombocytopenia (ITP) patients in a manner that may be TGF-β1 dependent 118. This further indicates that platelets may be mediators of all phases of T-cell responses, including the resolution phase necessary for proper tissue repair. Platelet derived MHC I may suppress CD8+ T-cell responses in sepsis119, further emphasizing that platelet immune functions cannot simply be considered in an acute post-injury pro-inflammatory context, but rather platelet functions should be considered in all phases of tissue injury responses including the reparative phases. This is particularly relevant when using genetically modified mouse models in which platelet functions or platelet derived molecules are altered from birth, as it may have unappreciated impacts on immune development and disease model outcomes that are the result of the loss of platelet immune limiting effects.

T-cell activation is dependent on antigen presenting cells (APC) that must internalize, process, and present antigen in the context of a Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC), while simultaneously providing co-stimulatory signals via either CD80 or CD86 interactions with T-cell CD28 (Fig. 5). MHC I presents antigen to CD8+ T-cells, while MHC II presents antigen to CD4+ T-cells. All cells, except red blood cells (RBC), have MHC I and the potential to present antigen to CD8+ T cells, if they can process antigen and express co-stimulatory molecules. ‘Professional’ APCs such as dendritic cells (DC) constitutively express MHC II and present antigen to CD4+ T-cells. Other cells such as endothelial cells can be induced to express MHC II and are considered non-professional APCs 120, 121. DCs differentiate and mature from myeloid lineage cells and platelets can indirectly influence T-cell activation by promoting DC maturation via platelet derived CD40L.122 Platelet secreted products have also been proposed to induce DC maturation that may then influence T helper cell polarization.123 Direct platelet interactions with circulating monocytes that have the potential to become DCs were shown to lead to DC differentiation in a P-selectin-dependent, but cytokine independent manner.124 Not only may platelets influence DC differentiation and function, platelets may also deliver antigen to DCs (Fig. 5). Platelets have been shown to associate with Listeria in the circulation, and in a complement- and GP1b-dependent manner, shuttle the bacteria to CD8+ DCs in the spleen to augment T-cell responses to the blood infection and thus function as an immune sentinel.125

Platelets express T-cell co-stimulatory molecules; human platelets express both CD80 and CD86 while mouse platelets express only CD86, and all platelets express CD40 at high levels that can provide additional T-cell co-stimulation (Fig. 5).106 Platelets have an active proteosome that can process exogenous antigen, and platelets have the ability to internalize antigens, including antigen-antibody complexes.106, 126, 127 By loading platelets with antigen and transfusing the platelets into a recipient mouse, platelets were shown to induce CD8+ T-cell responses in a MHC I-dependent manner in vivo.106 However, whether this effect on T cell responses is dependent on direct platelet and T-cell interactions or is indirect via an antigen presenting cell interaction is not yet known.

Megakaryocytes (Mks) shape platelets’ immune phenotype

Platelets are produced by regulated processes in which Mks either form pro-platelets that project into the blood stream to facilitate platelet release, or Mks may produce platelets through membrane budding regulated events.128–132 Mks have typically been described as large (30 to >100 μm) bone marrow resident cells that are polyploid and can make many copies of their genome (64N or greater is common) without cell or nuclear division. The reasons why Mks duplicate their DNA without nuclei or cell duplications are not known, but may be associated with a greater capacity to increase membrane mass to make more platelets compared to lower ploidy Mks.133, 134 Thrombopoietin (TPO) is the major liver derived cytokine signal to increase Mk differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) and increased plasma TPO drives more Mk formation and increased platelet counts.135 The TPO-receptor (TPOR, also known as c-mpl) is present on platelets and megakaryocytes, so when platelet levels decline, free plasma TPO is increased to signal more Mk differentiation and increased platelet production.136 TPO is made from liver hepatocytes, along with acute phase proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloids, and complement proteins. An increased drive for platelet production can therefore be part of the early acute phase immune responses.135, 137 Other immune signals can augment Mk and platelet production, particularly during inflammation.137–139 Immune molecules such as IL-1, IL-6 and IL-3 induce platelet production (emergency thrombopoiesis) and can maintain low levels of platelet production as evidenced by mice that lack TPOR, while being thrombocytopenic, still having enough Mks and platelets to prevent acute bleeding issues in unprovoked states.135 This further emphasizes the ‘inter-twining’, or perhaps the co-evolution, of immune regulation and platelet production. Conceptually this makes sense – a bleeding episode that results in a measurable decline in platelet numbers is typically associated with a significant vascular breach that may be a source of pathogen exposure and necessitate the demand for significant tissue repair and immune responses. Therefore, the dual induction of platelet production and immune responses provides a level of efficiency in tissue repair and pathogen defenses.

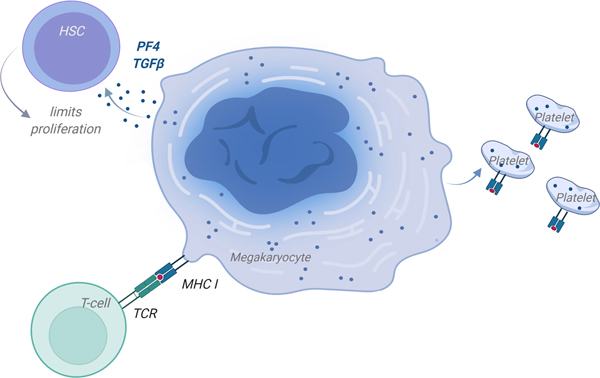

MKs regulate immune cell development in the bone marrow

Mks regulate the development of other immune cells in the bone marrow (BM). A complex network of cytokine signaling between Mks and neutrophils has been shown to facilitate neutrophil BM egress.140 Increased G-CSF indirectly lead to an increase in TPO that stimulated Mks to produce KC/CXCL1 (IL-8 in humans), that in turn stimulated neutrophil egress. Given that Mks produce and secrete many cytokines and chemokines, regulating the egress of neutrophils may represent only one of many Mk regulated immune cell development processes in the marrow space. For example, mice lacking PF4 had delayed maturation to a committed B-cell lineage in the bone marrow environment, but PF4 was found to have no effect on peripheral B-cell maturation and maintenance.141 This further indicates potential key links between Mks and immune cell development in the marrow space. Mk and immune cell development connections may begin as early as the HSC, as Mks regulate HSC quiescence via PF4 and TGF-β signaling (Fig. 6),142, 143 leading to the concept of a potential Mk-HSC niche. However, little is known whether immune challenges influence Mk regulation of HSC proliferation, and thus the Mk interface with broader immune cell development. As Mk immune regulatory roles become better appreciated, it may lead to a deeper understanding of how Mks mediate progenitor cell maintenance as well as progenitor lineage bias.

Figure 6: Megakaryocytes (Mks) are Immune Regulators.

Mks secrete immune molecules to maintain a Mk-HSC niche and HSC quiescence. Mks process and present antigen and produce platelets with processed antigen.

APC-antigen presenting cell; MHC-major histocompatibility complex; TCR-T-cell receptor. (Illustration Credit: Ben Smith)

Infection-mediated changes in Mks

Because Mks are rarely considered in an immune context, how Mks both shape and are shaped by, their immune environment has received little attention. In general, the Mk and platelet transcriptomes parallel each other, as Mks provide platelets with mRNA transcripts.128, 144–146 Like more classically described immune cells, Mks are responsive to infections and inflammation. For example, Interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3) expression is increased in platelets from patients during influenza and dengue virus (DENV) infections, and lower platelet IFITM3 is correlated with increased illness and mortality.5 Furthermore, infecting human Mks with DENV selectively increased type I interferons and IFITM3, and IFITM3 overexpression in Mks prevented DENV infection, demonstrating that Mks are an immune regulatory cell in viral infections.

Mks package platelet granules with inflammatory molecules, including PF4, RANTES/CCL5, CXCL12, CD40L, PPBP, and TGF-β.147 Mks also possess innate immune cell associated molecules such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), CD36, and the inflammasome related P2X receptors,14, 148–151 as well as adaptive immune associated molecules including CD40, CD40L, CD80, CD86 and MHC I.152 MHC II expression is lower on higher ploidy BM Mks, but MHC II is expressed by lung Mks, Mk progenitors, and at least some 2N BM Mks.153 Both Mk progenitors and lung Mks are predominately 2N, perhaps indicating a loss of immune differentiation with ploidy expansion that needs more investigation. The recent identification of a low ploidy, immune differentiated BM Mk population154 also highlights the unexplored question of where and how immune modulatory Mks arise in a tissue environment, whether Mk immune phenotype is associated with ploidy, and the role of low ploidy Mks in platelet production during times of immune stress. This recently defined low ploidy ‘immune sub-population’ of bone marrow Mks were shown to be defined by CD53 and LSP1 expression, their ability to internalize and cross-present antigen, and their expansion upon pathogen exposure. Much more work needs to be done to draw comparisons between the low ploidy immune Mk populations across tissues, as well as to better define their immune characteristics and immune functions.

Lung Mks, immunity and platelets

Despite a long history of studies showing the presence of Mks in the lung that may also produce platelets155, 156, a more definitive demonstration of a significant number of platelet-producing Mks in the lung was only recently published132. RNA-seq and scRNA-seq on lung and BM Mks suggested that lung Mks are immune differentiated compared to BM Mks132 leading us to term lung Mks as MkL to denote their differences from BM Mks.132, 157, 158 These immune phenotype differences may in large part be driven by the tissue environment, as we found that siimilar to more ‘traditional’ immune cells, Mks are environmentally responsive and exist on an immune spectrum that is dependent on the inflammatory environment157. The BM is an immune quiescent environment that allows for naïve cell development such that when a new immune cell leaves this protected space, it can respond to peripheral tissue demands. In contrast, the lung has a microbiome and faces constant antigen challenges. In support of this concept, isolated BM Mks could be induced to have a MkL-like immune-phenotype by the addition of immune agonists and cytokines such as IFNγ, LPS, or IL-33. On a functional level, Mks can cross-present antigen on MHC I and activate CD8+ T-cells159 and Mks transfer MHC I with antigen to platelets in vitro (Fig. 6).159 This raises the still speculative concept that platelet production in the lung may be a means of antigen dissemination either for immune responses or immune tolerance, and yet another way in which platelets are immune sentinels or maintain immune tolerance. MHC II positive Mk progenitors (MkP) have been shown to be present in the spleen and using a Lupus model, MkPs isolated from the spleen presented autoantigens and induced Th17 dominant responses 153, 160. Direct in vivo evidence of MkP antigen presentation in the spleen is needed to determine the more broad disease relevance, but these studies may provide the framework and basis to do so.

The origin of ‘immune differentiated’ MkL remains unknown. The typical explanation is that MkL originate from circulating BM Mks or MkPs and become ‘trapped’ in the lung vasculature.161 However, there is no true experimental evidence to support this concept. Based on a classical understanding of hematopoiesis, Mks arise from a well-defined hierarchy of cells within the BM that begins with HSCs. A pool of long- and short-term HSCs with self-renewal potential contributes to multipotent progenitors (MPPs) with no self-renewal potential and some lineage bias.162–165 MPP subtypes 1 and 2 give rise to common myeloid progenitors that may differentiate to a Megakaryocyte/Erythrocyte Progenitor (MEP).162, 165, 166 Recent evidence supports the existence of Mk-biased HSCs that bypasses the standard hierarchical tree and differentiate more directly to Mks, 167–172 particularly during inflammation.166 In describing platelet-producing MkL, a functional hematopoietic progenitor pool in the lung was also described.132 The extent to which this lung hematopoietic progenitor population contributes to an extravascular MkL pool in homeostatic conditions remains unclear. A lack of research tools to reconstitute only part of the HSPC population (lung or BM) is a major limitation to determining the ultimate origin of lung Mks.

Whether all platelets are ‘created immunologically equal’ is also not known, in large part due to the inability to perform single platelet analysis on a larger scale, unlike other blood cell types. But there are some clues that are perhaps emerging from Mk analysis. There are conflicting thoughts regarding MkL ploidy and what it means in terms of Mk ‘maturity’. The majority of MkL are 2N and as a result, it has been proposed that MkL have an immature phenotype173, 174. What Mk maturity means in a functional context is less clear. CD42d has been proposed as a marker of maturity for megakaryocytes175 and CD42d is greater on BM Mks than MkL.132 However, using scRNA-seq and flow cytometry to assess MkL maturity based on typical platelet producing Mk markers, MkL in adults (10 wks) and in development (E13) had greater enrichment in cellular pathways associated with pro-platelet formation, such as ATP production, protein translation, and cytoskeletal rearrangement. Additionally, using flow cytometry they found a greater proportion of CD42d+ MkL than BM Mks.173 Because higher ploidy Mks have historically been thought to be more differentiated for platelet production, better defining what ploidy functionally means in these different tissue environments could provide important insights into their roles in immune platelet production or immune modulation. Resolving the associations between ploidy, platelet production, and immune differentiation may also yield clues into the origins of extramedullary Mks.

Conclusion

Platelets are equipped with the machinery to participate in both innate and adaptive immune responses. This is evident by their ability to respond to various pathogens through their TLRs, complement activation, sensing of immune complexes through FcγRIIa, activation of T-cells, APC to dendritic cells and so forth. Due to their abundant nature (~20 more platelets than WBC/μl), prepackaged content, anucleate nature and their role in hemostasis, platelets are central not only in preventing bleeding but in rapidly responding to microbial components and alerting the immune system. As infections progress, platelets are also able to respond to increased levels of circulating antibody-pathogen components and to send signals to cells of the adaptive immune branch. As infection progresses, Mks also contribute to changes related to the immune response in platelets underlining the importance of platelets during the infection-mediated immune response. Overall, during infection, platelets may orchestrate beneficial innate and adaptive immune responses. As infection progresses and platelets are activated by various means and this additive response can lead to pathological outcomes. As our understanding of the immune role of platelets grows, we can better design platelet-targeted treatments for patients who present with thrombotic complications during infection.

Sources of Funding

Dr. Koupenova is supported by NIHLBI R01 HL153235 and NIH UL1TR001453. Dr. Morrell is supported by R21 HL153409, R01HL141106 and R01 HL142152

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AIRTRIP

AnaklnRa for Treatment of Recurrent Idiopathic Pericarditis

- AMI

acute myocardial infarction

- ASC

apoptosis-associated spec-like protein containing a carboxy-terminal containing a caspase recruiting domain

- ATPase

adenosine triphosphatase

- CANTOS

Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study

- CIRT

Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial

- COLCOT

Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcome Trial

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DAMPS

damage-associated molecular patterns

- D-HART

Diastolic Heart Failure Anakinra Response Trial(s)

- GSDMD

gasdermin D

- HF

heart failure

- IL

interleukin

- IL-18BP

IL-18 binding protein

- IL-1R1

IL-1 receptor type 1

- IL-1Ra

IL-1 receptor antagonist

- LDL-R

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LoDoCo

Low-Dose Colchicine

- M RC-I LA*

Medical Royal Council

- Heart study

InterLeukin-1 Antagonist Heart Study

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation factor 88

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NLRP3

NACHT LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

- P2X7

purinergic receptor 2X7

- REDHART

Recently Decompensated Heart Failure Anakinra Response Trial(s)

- sST2

soluble ST2

- ST2

suppressor of tumorigenicity 2

- STEM I

ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction

- TIR

Toll-IL-1-receptor

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- VCUART

Virginia Commonwealth University Anakinra Remodeling/Response Trial(s)

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures

References

- 1.Machlus KR, Italiano JE Jr. The incredible journey: From megakaryocyte development to platelet formation. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:785–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koupenova M, Clancy L, Corkrey HA, Freedman JE. Circulating platelets as mediators of immunity, inflammation, and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2018;122:337–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy L, Beaulieu LM, Tanriverdi K, Freedman JE. The role of rna uptake in platelet heterogeneity. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:948–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koupenova M, Ravid K. Biology of platelet purinergic receptors and implications for platelet heterogeneity. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell RA, Schwertz H, Hottz ED, Rowley JW, Manne BK, Washington AV, Hunter-Mellado R, Tolley ND, Christensen M, Eustes AS, Montenont E, Bhatlekar S, Ventrone CH, Kirkpatrick BD, Pierce KK, Whitehead SS, Diehl SA, Bray PF, Zimmerman GA, Kosaka Y, Bozza PT, Bozza FA, Weyrich AS, Rondina MT. Human megakaryocytes possess intrinsic antiviral immunity through regulated induction of ifitm3. Blood. 2019;133:2013–2026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hottz ED, Lopes JF, Freitas C, Valls-de-Souza R, Oliveira MF, Bozza MT, Da Poian AT, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA, Bozza FA, Bozza PT. Platelets mediate increased endothelium permeability in dengue through nlrp3-inflammasome activation. Blood. 2013;122:3405–3414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GT, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: Kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory il-1beta-rich microparticles. J Immunol. 2011;186:5489–5496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koupenova M, Corkrey HA, Vitseva O, Tanriverdi K, Somasundaran M, Liu P, Soofi S, Bhandari R, Godwin M, Parsi KM, Cousineau A, Maehr R, Wang JP, Cameron SJ, Rade J, Finberg RW, Freedman JE. Sars-cov-2 initiates programmed cell death in platelets. Circ Res. 2021;129:631–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.French SL, Butov KR, Allaeys I, Canas J, Morad G, Davenport P, Laroche A, Trubina NM, Italiano JE, Moses MA, Sola-Visner M, Boilard E, Panteleev MA, Machlus KR. Platelet-derived extracellular vesicles infiltrate and modify the bone marrow during inflammation. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3011–3023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boilard E, Pare G, Rousseau M, Cloutier N, Dubuc I, Levesque T, Borgeat P, Flamand L. Influenza virus h1n1 activates platelets through fcgammariia signaling and thrombin generation. Blood. 2014;123:2854–2863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brubaker SW, Bonham KS, Zanoni I, Kagan JC. Innate immune pattern recognition: A cell biological perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:257–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauer EM, Chanthaphavong RS, Sodhi CP, Hackam DJ, Billiar TR, Bauer PM. Genetic deletion of toll-like receptor 4 on platelets attenuates experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2014;114:1596–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koupenova M, Mick E, Mikhalev E, Benjamin EJ, Tanriverdi K, Freedman JE. Sex differences in platelet toll-like receptors and their association with cardiovascular risk factors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1030–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andonegui G, Kerfoot SM, McNagny K, Ebbert KV, Patel KD, Kubes P. Platelets express functional toll-like receptor-4. Blood. 2005;106:2417–2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maugeri N, Franchini S, Campana L, Baldini M, Ramirez GA, Sabbadini MG, Rovere-Querini P, Manfredi AA. Circulating platelets as a source of the damage-associated molecular pattern hmgb1 in patients with systemic sclerosis. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:584–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noris M, Remuzzi G. Overview of complement activation and regulation. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:479–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marin Oyarzun CP, Glembotsky AC, Goette NP, Lev PR, De Luca G, Baroni Pietto MC, Moiraghi B, Castro Rios MA, Vicente A, Marta RF, Schattner M, Heller PG. Platelet toll-like receptors mediate thromboinflammatory responses in patients with essential thrombocythemia. Front Immunol. 2020;11:705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aslam R, Speck ER, Kim M, Crow AR, Bang KW, Nestel FP, Ni H, Lazarus AH, Freedman J, Semple JW. Platelet toll-like receptor expression modulates lipopolysaccharide-induced thrombocytopenia and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in vivo. Blood. 2006;107:637–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damien P, Cognasse F, Eyraud MA, Arthaud CA, Pozzetto B, Garraud O, Hamzeh-Cognasse H. Lps stimulation of purified human platelets is partly dependent on plasma soluble cd14 to secrete their main secreted product, soluble-cd40-ligand. BMC Immunol. 2015;16:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang G, Han J, Welch EJ, Ye RD, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Malik AB, Du X, Li Z. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates platelet secretion and potentiates platelet aggregation via tlr4/myd88 and the cgmp-dependent protein kinase pathway. J Immunol. 2009;182:7997–8004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopes Pires ME, Clarke SR, Marcondes S, Gibbins JM. Lipopolysaccharide potentiates platelet responses via toll-like receptor 4-stimulated akt-erk-pla2 signalling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0186981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogel S, Bodenstein R, Chen Q, Feil S, Feil R, Rheinlaender J, Schaffer TE, Bohn E, Frick JS, Borst O, Munzer P, Walker B, Markel J, Csanyi G, Pagano PJ, Loughran P, Jessup ME, Watkins SC, Bullock GC, Sperry JL, Zuckerbraun BS, Billiar TR, Lotze MT, Gawaz M, Neal MD. Platelet-derived hmgb1 is a critical mediator of thrombosis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:4638–4654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claushuis TAM, Van Der Veen AIP, Horn J, Schultz MJ, Houtkooper RH, Van ‘t Veer C, Van Der Poll T. Platelet toll-like receptor expression and activation induced by lipopolysaccharide and sepsis. Platelets. 2019;30:296–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivadeneyra L, Carestia A, Etulain J, Pozner RG, Fondevila C, Negrotto S, Schattner M. Regulation of platelet responses triggered by toll-like receptor 2 and 4 ligands is another non-genomic role of nuclear factor-kappab. Thromb Res. 2014;133:235–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nocella C, Carnevale R, Bartimoccia S, Novo M, Cangemi R, Pastori D, Calvieri C, Pignatelli P, Violi F. Lipopolysaccharide as trigger of platelet aggregation via eicosanoid over-production. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1558–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venereau E, Ceriotti C, Bianchi ME. Damps from cell death to new life. Front Immunol. 2015;6:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindemann S, Tolley ND, Dixon DA, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Weyrich AS. Activated platelets mediate inflammatory signaling by regulated interleukin 1beta synthesis. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:485–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, McDonald B, Goodarzi Z, Kelly MM, Patel KD, Chakrabarti S, McAvoy E, Sinclair GD, Keys EM, Allen-Vercoe E, Devinney R, Doig CJ, Green FH, Kubes P. Platelet tlr4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13:463–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolb JP, Oguin TH 3rd, Oberst A, Martinez J Programmed cell death and inflammation: Winter is coming. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:705–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Ng MM, Chu JJ. Activation of tlr2 and tlr6 by dengue ns1 protein and its implications in the immunopathogenesis of dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bieback K, Lien E, Klagge IM, Avota E, Schneider-Schaulies J, Duprex WP, Wagner H, Kirschning CJ, Ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schaulies S. Hemagglutinin protein of wild-type measles virus activates toll-like receptor 2 signaling. J Virol. 2002;76:8729–8736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Assinger A, Kral JB, Yaiw KC, Schrottmaier WC, Kurzejamska E, Wang Y, Mohammad AA, Religa P, Rahbar A, Schabbauer G, Butler LM, Soderberg-Naucler C. Human cytomegalovirus-platelet interaction triggers toll-like receptor 2-dependent proinflammatory and proangiogenic responses. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P, Jonsson CB, Kanneganti TD. Tlr2 senses the sars-cov-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:829–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blair P, Rex S, Vitseva O, Beaulieu L, Tanriverdi K, Chakrabarti S, Hayashi C, Genco CA, Iafrati M, Freedman JE. Stimulation of toll-like receptor 2 in human platelets induces a thromboinflammatory response through activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Circ Res. 2009;104:346–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parra-Izquierdo I, Lakshmanan HHS, Melrose AR, Pang J, Zheng TJ, Jordan KR, Reitsma SE, McCarty OJT, Aslan JE. The toll-like receptor 2 ligand pam2csk4 activates platelet nuclear factor-kappab and bruton’s tyrosine kinase signaling to promote platelet-endothelial cell interactions. Front Immunol. 2021;12:729951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]