Early Life

Born in Las Vegas, New Mexico, Mary Lake was the eldest child of a first-generation Lithuanian father, an ophthalmologist then serving in the United States Army, and a first-generation Protestant, Wisconsin-born mother of Norwegian descent. Her parents had met and married while her father was a resident and her mother a nurse at the University of Wisconsin teaching hospital. Mary Lake was born during the Second World War while her father was stationed in New Mexico, before his posting overseas for two years in a military hospital in the Azores.

Mary Lake spent her early life in Huntington, West Virginia, an idyllic small town stretched out along the Ohio River—front doors were left unlocked, children walked to and from father took Mary Lake and her school with friends, and lunch was eaten at home. On the weekends, from the age of nine, her younger brother, Chuck, into the mountains of West Virginia where they shot bottles off tree stumps with their .22 rifles. From an early age, she found “the world beyond the coalmines and mountains magnetic,” as she describes in her 2016 book, A Doctor’s Journey: What I Learned about Women, Healing and Myself in Eritrea1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Microscopy revealed distinctive circular forms in MtDNA

Attribution: ©1973 by The Rockefeller University Press. Polan ML, Friedman, Gall JG, Gehring W. Isolation and characterization of mitochondrial DNA from Drosophila melanogaster.2 Originally published in the Journal of Cell Biology. 1973; 56:580–589. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.56.2.580

Her large Jewish family in Huntington comprised her father’s relatives. She recalls being raised among her two younger siblings and a dozen cousins whose fathers, unlike her physician father, were connected to the Polan family business, a manufacturer of bombsights during World War II and, subsequently, optical lenses. The mothers of all the children were surrogate mothers to all the cousins. When it came to issues of discipline, “they would paddle you or correct you regardless of who your parents were,” Mary Lake recalls. The cousins were more like siblings and have remained so throughout their lives.

Mary Lake’s interest in medicine came quite naturally—her father often took her with him on Sunday mornings to round on surgical patients at the hospital. Her first job at the age of 17 was as a summer ward clerk at the local hospital where she managed the phones and paperwork on a surgical ward. Mary Lake says that her father was loving and supportive and made her feel she could achieve anything to which she aspired.

It all sounds pretty idyllic, except for one thing. Mary Lake perceived a much more rewarding and exciting world outside the Appalachian region of the country, in part because her father had often exposed their family to the more metropolitan and cosmopolitan regions of the country, which included periodic trips to New York City, Miami, and the Caribbean islands. In addition, already the voracious reader she has remained throughout her life, Mary Lake knew she had a great deal to learn from the wider world. “I would have done anything to get out of West Virginia” and “If there’s some way to get there, I’m ready to go anywhere” are two of a number of her utterances that begin to describe the life of Mary Lake Polan.

Her chance came during the ninth grade in Huntington. At Mary Lake’s request, her parents surveyed several Southern boarding schools but, ultimately, they sent her to the Emma Willard School, a private school for girls in Troy, New York, founded in 1814. At first, Mary Lake told me that she felt more like the Appalachian girl she wished to leave behind. Her fellow classmates were, at least in her mind, more sophisticated, more worldly, than she envisioned herself. For example, in class one day, her French pronunciation of the Battle of Agincourt was corrected by her teacher. In that moment, she promised herself she would learn French and never again be embarrassed by mispronouncing a French word. And she did learn, spending her junior year of college in Paris with the Smith College Junior Year Abroad Program. Mary Lake’s talent to live up to her father’s expectations soon showed itself as an indicator of what life thereafter would be like for her. The Emma Willard School and its student life became something that she came to enjoy and admire. Years later, her devotion to the merits of all-girls schooling caused her to remain both supportive of the School and connected to its leadership and her classmates.

An Education in Connecticut: College and Graduate School

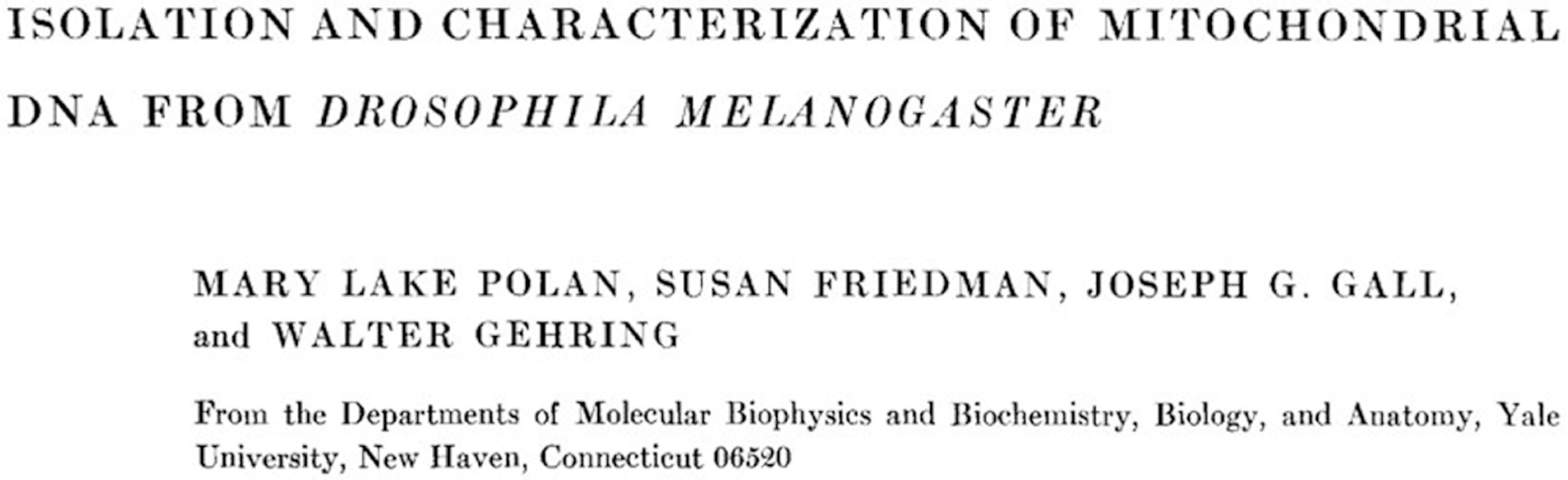

Mary Lake attended a private liberal arts women’s college in New London. The school was supportive of students charting their own educational course and Mary Lake began, after her freshman year, spending a summer in Switzerland with the “The Experiment in International Living” program. That summer trip was quickly followed by her junior year in Paris. After graduating from Connecticut College with a major in chemistry, Mary Lake migrated 50 miles down the Connecticut coastline to the Department of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale University, where she completed her PhD in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, followed by a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Biology in the laboratory of Dr Joseph Gall. Dr Gall, who developed in situ hybridization, was awarded the Albert Lasker Award in 2006 and is known for encouraging women to pursue a career in science. His trainees include Dr Joan Steitz (Lasker-Koshland awardee for pioneering contributions to RNA biology) and Dr Elizabeth Blackburn (Nobel Laureate for her discoveries of the molecular nature of telomeres). Mary Lake’s work focused on the isolation and characterization of circular mitochondrial DNA of Drosophilia melanogaster2 (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Behold the fruit fly: molecular revelations of MtDNA

While working in the laboratory of Dr Joseph Gall at Yale University in the 1970s, Dr Mary Lake Polan analyzed and described unique genetic aspects of the fruit fly, reported in the study “Isolation and characterization of mitochondrial DNA from Drosophila melanogaster.”2

Attribution: ©1973 by The Rockefeller University Press. Polan ML, Friedman, Gall JG, Gehring W. Isolation and characterization of mitochondrial DNA from Drosophila melanogaster. Originally published in the Journal of Cell Biology. 1973; 56:580–589. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.56.2.580

Yale University Medical School, Residency, and Fellowship

At this juncture, medical school seemed like a better idea than a laboratory career—Mary Lake found talking to colleagues about the experiments was more fun than actually doing the research. Yale Medical School offered a logical path to medicine, as there were no exams and only required a passing grade on Boards Part 1 and Part 2 as well as a thesis project to graduate. Having completed her PhD thesis at Yale, Mary Lake finished medical school in three years—an important bonus since her father had told her he was not willing to pay for medical school. Undertaking only three years of tuition was critical, and she spent her two preclinical years of medical school working part-time as a laboratory technician in Dr Gall’s lab to support herself.

There were two other major advantages to staying in New Haven. First, the Yale curriculum was flexible, allowing Mary Lake to spend three months at the University of Oxford, England, in the Radcliffe Infirmary and the John Radcliffe Hospital completing her obstetrics and gynecology and pediatric clinical clerkships during her third year of medical school. Second, while conducting research in the Department of Dermatology for her doctoral thesis at Yale, she met her future husband, Dr Joseph Smith McGuire, Professor of Dermatology.

Mary Lake remained at Yale for her residency. Indeed, she was the first woman to graduate from the residency program in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. She had the opportunity to spend three months as an elective during the last year of residency in the hospitals in Shiraz, the “City of Roses,” in southern Iran. The Iranian spring included trips to Isfahan and to Persepolis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site located 60 kilometers from Shiraz, whose ruins date back to 515 BC. The mystique of Persia was translated into Mary Lake’s medical mystery novel, Second Seed, published in 19873 (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Bridging science, history, and the literary arts

Inspired during a visit to the historic city of Shiraz in southern Iran, Dr Polan wrote a medical mystery novel Second Seed.3

Attribution: ©1988. Image of the paperback reproduced with permission by St. Martin’s Press.

A Fellowship in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility

Louise Brown, the first in vitro fertilization baby, was born on July 25, 1978. The excitement of the new infertility technologies drew Mary Lake to a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellowship with Drs Nathan Kase and Alan DeCherney, who worked with Drs Harold Behrman and Richard Hochberg conducting bench research in endocrinology.4 The fellowship was followed by a faculty appointment as Assistant Professor at Yale, where she initiated an NIH-sponsored research program on the hormonal function of human granulosa-luteal cells.5, 6

Yale also brought priceless opportunities for relationships and mentors. There, she married Dr McGuire, a distinguished physician and teacher who, remarkably, came from Mary Lake’s native West Virginia. From his early life as a coal miner’s son, Joe became a highly regarded Professor of Pediatric Dermatology at Yale and later at Stanford. As a mentor, he encouraged Mary Lake to fully realize her potential in the world of medicine. Her other mentors at Yale were Drs Joan Steitz, Florence Haseltine, and Leon Speroff, along with Drs DeCherney and Kase. The latter three, previously recognized as Giants in Obstetrics and Gynecology, have been important mentors to many in obstetrics and gynecology.7–9

Throughout her residency and fellowship, which included time as a fellow in gynecologic oncology, she met and worked for Dr John McLean Morris, a Yale gynecologist who had been raised in China. The child of Christian missionaries, Dr Morris, world renowned for his discovery of testicular feminization and post-coital contraception (morning after pill), introduced Mary Lake to the Yale-China Program, which, since 1914, had sponsored Yale undergraduates to teach English to middle-school students in Changsha, a city of five million people in central Hunan Province. As a junior faculty member, Mary Lake, her husband Joe McGuire, and their two children, seven-year-old Joshua and five-year-old Lindsay, spent four months in 1986 at the Second Affiliated Hospital in Changsha teaching students and residents. After enrolling the children in a Chinese daycare, Mary Lake, then four months pregnant with their third child, taught, lectured, and performed infertility surgeries. On returning to Yale, her research interests expanded to include cytokines and the relationship of interleukin (IL)-1 to reproductive function10–12 (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5:

An innovative study in implantation

A study of importance emerged during her tenure at Stanford University, reflecting a significant research interest in implantation, reported in the article “Single Blastomeres within Human Preimplantation Embryos Express Different Amounts of Messenger Ribonucleic Acid for β-Actin and Interleukin-1 Receptor Type I.”22

Attribution: Reproduced with permission. Originally published by the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 Mar; 83(3):953–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.3.4632.

Figure 6:

A murine study of molecular mechanisms in implantation

A novel finding in implantation that informed our field came forth from Dr Mary Lake Polan’s laboratory at Stanford University in the late 1990s, reported as “Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents embryonic implantation by a direct effect on the endometrial epithelium.”24

Attribution: Reproduced with permission. Originally published by Fertility and Sterility. Fertil Steril. 1998 Nov;70(5):896–906. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00275-1.24

Professor and Chair at Stanford University School of Medicine

In 1990, Mary Lake moved, with her husband and their three young children, to Palo Alto, California, to become Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, as the Katherine Dexter McCormick and Stanley McCormick Memorial Professor at Stanford University School of Medicine. This appointment opened an even wider world of interest in, and in service to, women’s health for Mary Lake. During her 16 years in that capacity, she joined the boards of Wyeth, a prestigious pharmaceutical company, and Quidel, a maker of rapid diagnostic tests; she was elected to The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) and served on its Governing Council as well as on numerous NIH and other professional association committees; and she lectured and testified broadly about women’s health issues. During a sabbatical, Mary Lake returned to school at the University of California, Berkeley, where she obtained a Master’s in Public Health (MPH) degree and became interested in obstetric fistulae. Significantly, in 2002, she founded the Eritrean Women’s Project, described earlier, resulting in novel reports of surgical techniques and social interventions to prevent and treat obstetric fistulas resulting from birth trauma.13–15

A Role for Interleukin-1 in Ovulation and Implantation

Ovulation is a sterile inflammatory process, and a role for the IL-1 system was envisioned in the early 1990s after the identification of the cytokine in human follicular fluid16, 17 and the characterization of the human intraovarian IL-1 system.18 Mary Lake’s studies showed that the production of IL-1 by peripheral blood monocytes and ovarian cells increases during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and produces a mid-cycle IL-1 surge in humans.19 Her laboratory at Stanford demonstrated the presence of the IL-1 system in the mouse ovary during follicular growth, ovulation, and lutealization20 and of time-dependent inhibition of ovulation by the natural IL-1 receptor antagonist.21 Much of this work was done in collaboration with Professor Carlos Simón, a member of her team at Stanford who now has become a towering figure in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. The focus then turned to the role of IL-1 in implantation after showing that the blastocysts produce IL-122, 23 (Figure 5) and that the administration of the natural IL-1 receptor antagonist prevented embryonic implantation by a direct effect on the endometrial epithelium24 (Figure 6).

Mary Lake Polan, the Author

Several years after writing her novel Second Seed, Mary Lake published A Doctor’s Journey: What I Learned about Women, Healing, and Myself in Eritrea,1 a story of friendship between physicians in the US and doctors and nurses in Eritrea, which began on a winter night in 2002. With this first trip to East Africa, Mary Lake initiated the Eritrean Women’s Program, created to surgically treat women with obstetric fistulas and to train Eritrean surgeons to repair the fistulas, an endeavor lasting nearly two decades. This excerpt is Mary Lake’s description of her first arrival in Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, a small country in the Horn of Africa, on the Red Sea, tucked between Sudan, Ethiopia, and Djibouti:

“After the plane had hopscotched from San Francisco to Frankfurt to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the pilot’s announcement—“We’re descending for our landing in Asmara”—was an electric jolt waking me from the intermittent dozing of the twenty-four-hour trip. Deprived of sleep, hair uncombed, I tried unsuccessfully to separate excitement from anxiety.

“The airplane door swung inward. Freezing night air washed over me. In my Out of Africa-influenced imagination, it should have been hot, but on this January night, I shivered in my cotton jacket as we descended the roll-up staircase onto a cracked concrete runway. ASMARA AIRPORT read the sign on the wall of a two-story building a couple of hundred yards away, visible in the yellow glow from the airport windows.

“I’d been dreaming of this moment for a long time. This trip was the goal I had worked toward over the last two years, ever since the idea of bringing American surgeons to treat women injured in childbirth became the focus of my sabbatical studies in international public health. I was then Chair of the Ob-Gyn department at Stanford University, and I had become fascinated by the problem of obstetric fistula—a terrible situation caused by prolonged labor which left a woman with a stillborn baby and constantly leaking urine from a hole torn in her bladder.

“Five American gynecologists, including me, were here because of my efforts. After months of work and planning, I had finally persuaded two foundations to support this two-week trip to Eritrea….

“The heavy metal door to the terminal clanged open and we followed an animated group of Eritrean men and women into a bare room, painted a dull brown. The room was lit by hanging bulbs and smelled of stale cigarette smoke. Two unsmiling officials sat behind glass panels at the far end, the sleeves of their uniform shirts rolled up to the elbow. They were slowly and systematically examining documents handed to them by the incoming passengers. The Eritrean passengers chatted excitedly as they greeted one another and the border control guards behind the glass. Tired, we held back until one of the guards beckoned. One by one, we handed over our passports and visas to be stamped and were ushered into the Customs area. We waited as the boxes of donated medical sutures, antibiotics, and surgical retractors were brought from the plane and piled up around us.

“I began to sweat. What if nobody comes to meet us?

“We were here because I wanted to work in Africa. I was drawn to this strange and unknown world. I felt acutely responsible for the three other women docs and for the single man in the group. I silently prayed we would be able to accomplish our goal of successful surgeries and, equally important, that we’d be safe in this very foreign country….

“Please, God, let someone be here to tell us what to do and take care of us.”1

An International Presence

Before COVID-19 interfered with world travel, Mary Lake encouraged her second husband, Frank Bennack, Jr, (Figure 7), to take two trips that he probably would not have taken without her urging. The first, a trip in 2008 with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra to Pyongyang, North Korea, when Frank was serving as Chair of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Then, in October 2016, again with a Lincoln Center group, they went to Havana, Cuba.

Figure 7.

Sabbatical: Reflections on women’s reproductive health care in Eritrea1

Author Mary Lake Polan chronicles her sabbatical in Eritrea: the significant outcomes for pregnant women and their children affected by obstetric fistulas and other birth traumas and the restorative surgeries performed by an international medical team in her 2016 memoir, A Doctor’s Journey: What I Learned about Women, Healing and Myself in Eritrea.1

Attribution: ©2016 by Mary Lake Polan. Image reproduced with permission.

With Mary Lake’s planning, the couple also collaborated on family trips of up to 40 children, spouses, significant others, and grandchildren to Kenya and South Africa, to the glacial waters of Alaska, and to the beaches of the Galapagos Island, to name a few. After her marriage to Frank, Mary Lake moved to New York City and served as Visiting Professor at Columbia University School of Medicine before coming full circle to Yale in 2014 as Professor of Clinical Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences.

Having contributed to the field of women’s health in the laboratories, clinics, and operating rooms of the US, Iran, China, and Eritrea, Mary Lake says, “Living in a different country, working with physicians from other cultures, with very different training, forces you to be flexible, open to new techniques and, importantly, new ways to relate to people. Unconstrained by familiar social hierarchies, one is thrown back on oneself and discovers unexpected capabilities. It is a freedom to give back that becomes addictive, and it has been a guiding theme throughout my life, facilitating friendships between colleagues here at home and in countries around the world (Figures 8–10). Yes, it has allowed me to help women, but as importantly, it has enriched my life.” In the full spirit of giving, Mary Lake and Frank have endowed chairs at both Stanford and Yale dedicated to the area of gynecologic oncology in the respective Departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

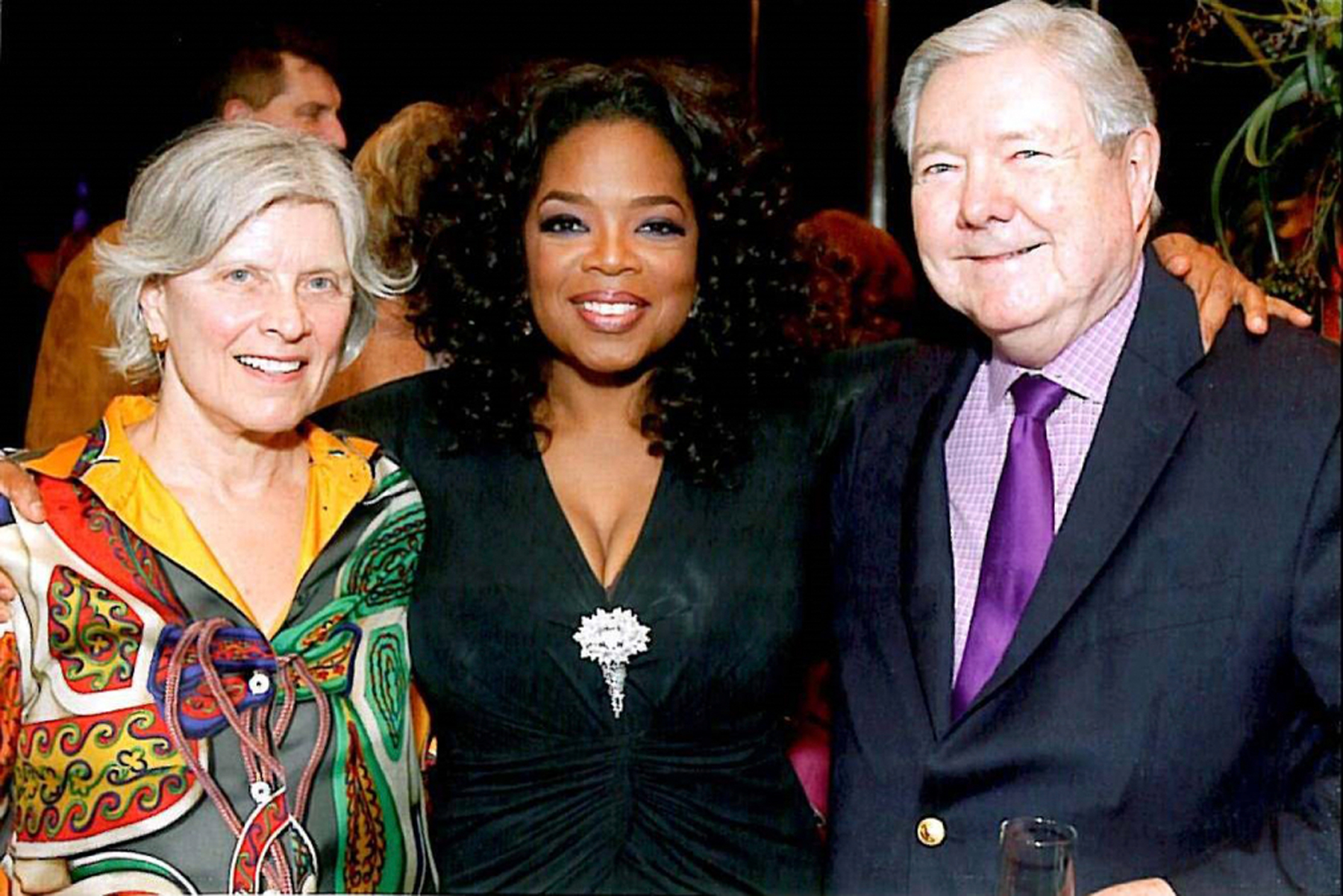

Figure 8:

A memorable day

Dr Mary Lake Polan and her husband Mr Frank A. Bennack, Jr., at their wedding, standing on a bluff overlooking the ranch.

Attribution: Photo courtesy of Dr Mary Lake Polan.

Figure 10:

L-R: Dr Mary Lake Polan, Ms Oprah Winfrey, Mr Frank A. Bennack, Jr. Attribution: Photo courtesy of Dr Mary Lake Polan.

The American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology recognizes Dr Mary Lake Polan’s professional contributions as a physician, scientist, leader, and role model.

Figure 3:

Marg Lake and her son Scott visiting Tehran, Iran

Attribution: Photo courtesy of Dr Mary Lake Polan.

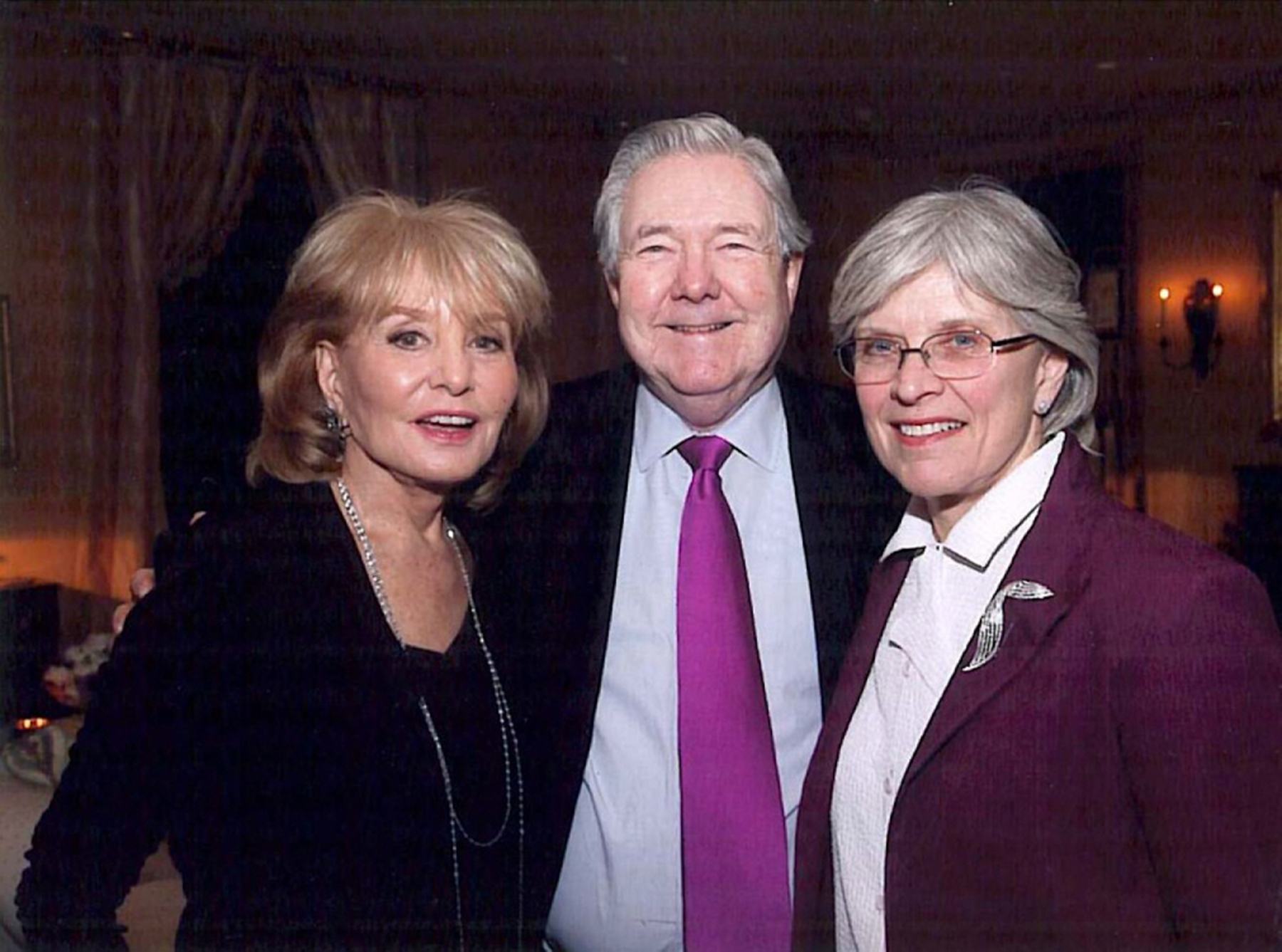

Figure 9:

Visiting with a well-known personality in broadcasting

Attribution: Photo courtesy of Dr Mary Lake Polan.

Figure 11:

Attending a History Channel symposium, 2019

L-R: William J. Clinton, former US president; Mr Frank A. Bennack, Jr; Dr Mary Lake Polan; and George W. Bush, former US president.

Attribution: Photo courtesy of Dr Mary Lake Polan.

Acknowledgements

This profile is based on conversations with Dr Mary Lake Polan and Mr Frank Bennack, Jr, during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Dr Polan has reviewed and agreed with this article.

Biography

Dr Mary Lake Polan is a physician-scientist, clinician, educator, and academic leader who has produced pioneering work on the role of cytokines and inflammation in reproduction and, specifically, in implantation and ovulation. She served as Professor and Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Stanford University, promoted clinical excellence, and established a unique program to treat women with obstetric fistulas and to train surgeons in the East African country of Eritrea. Dr Polan is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, an author, and a humanist. For her many contributions that have changed the lives of women, Dr Polan is recognized as a Giant in Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The author reports no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.POLAN ML. A Doctor’s Journey: What I learned about women, healing and myself in Eritrea. First Persona LLC; Number of pages. [Google Scholar]

- 2.POLAN ML, FRIEDMAN S, GALL JG, GEHRING W. Isolation and characterization of mitochondrial DNA from Drosophila melanogaster. The Journal of cell biology 1973;56:580–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.POLAN ML. Second Seed. Bronx, NY: Charles Scribner & Sons, Inc; Number of pages. [Google Scholar]

- 4.POLAN ML, DECHERNEY AH, HASELTINE FP, MEZER HC, BEHRMAN HR. Adenosine amplifies follicle-stimulating hormone action in granulosa cells and luteinizing hormone action in luteal cells of rat and human ovaries. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1983;56:288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.POLAN ML, LAUFER N, DLUGI AM, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin and prolactin modulation of early luteal function and luteinizing hormone receptor-binding activity in cultured human granulosa-luteal cells. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1984;59:773–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.POLAN ML, SEU D, TARLATZIS B. Human chorionic gonadotropin stimulation of estradiol production and androgen antagonism of gonadotropin-stimulated responses in cultured human granulosa-luteal cells. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1986;62:628–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ROMERO R Giants in Obstetrics and Gynecology Series: A profile of Nathan Kase, MD. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2017;217:112–20.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ROMERO R Giants in Obstetrics and Gynecology Series: A profile of Leon Speroff, MD. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2017;217:263.e1–63.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ROMERO R A profile of Alan H. DeCherney, MD. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2017;217:389.e1–89.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LOUKIDES JA, LOY RA, EDWARDS R, HONIG J, VISINTIN I, POLAN ML. Human follicular fluids contain tissue macrophages. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1990;71:1363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.POLAN ML, KUO A, LOUKIDES J, BOTTOMLY K. Cultured human luteal peripheral monocytes secrete increased levels of interleukin-1. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1990;70:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.POLAN ML, LOUKIDES J, NELSON P, et al. Progesterone and estradiol modulate interleukin-1 beta messenger ribonucleic acid levels in cultured human peripheral monocytes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1989;69:1200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.HUSAIN A, JOHNSON K, GLOWACKI CA, et al. Surgical management of complex obstetric fistula in Eritrea. Journal of women’s health (2002) 2005;14:839–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MORGAN MA, POLAN ML, MELECOT HH, DEBRU B, SLEEMI A, HUSAIN A. Experience with a low-pressure colonic pouch (Mainz II) urinary diversion for irreparable vesicovaginal fistula and bladder extrophy in East Africa. International urogynecology journal and pelvic floor dysfunction 2009;20:1163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.TURAN JM, JOHNSON K, POLAN ML. Experiences of women seeking medical care for obstetric fistula in Eritrea: implications for prevention, treatment, and social reintegration. Global public health 2007;2:64–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.KHAN SA, SCHMIDT K, HALLIN P, DI PAULI R, DE GEYTER C, NIESCHLAG E. Human testis cytosol and ovarian follicular fluid contain high amounts of interleukin-1-like factor(s). Molecular and cellular endocrinology 1988;58:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WANG LJ, NORMAN RJ. Concentrations of immunoreactive interleukin-1 and interleukin-2 in human preovulatory follicular fluid. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 1992;7:147–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.HURWITZ A, LOUKIDES J, RICCIARELLI E, et al. Human intraovarian interleukin-1 (IL-1) system: highly compartmentalized and hormonally dependent regulation of the genes encoding IL-1, its receptor, and its receptor antagonist. The Journal of clinical investigation 1992;89:1746–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.POLAN ML, LOUKIDES JA, HONIG J. Interleukin-1 in human ovarian cells and in peripheral blood monocytes increases during the luteal phase: evidence for a midcycle surge in the human. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1994;170:1000–6; discussion 06–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SIMÓN C, FRANCES A, PIQUETTE G, POLAN ML. Immunohistochemical localization of the interleukin-1 system in the mouse ovary during follicular growth, ovulation, and luteinization. Biology of reproduction 1994;50:449–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.SIMÓN C, TSAFRIRI A, CHUN SY, PIQUETTE GN, DANG W, POLAN ML. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist suppresses human chorionic gonadotropin-induced ovulation in the rat. Biology of reproduction 1994;51:662–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.KRÜSSEL JS, HUANG HY, SIMÓN C, et al. Single blastomeres within human preimplantation embryos express different amounts of messenger ribonucleic acid for beta-actin and interleukin-1 receptor type I. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1998;83:953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SIMÓN C, PELLICER A, POLAN ML. Interleukin-1 system crosstalk between embryo and endometrium in implantation. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 1995;10 Suppl 2:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.SIMÓN C, VALBUENA D, KRÜSSEL J, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents embryonic implantation by a direct effect on the endometrial epithelium. Fertility and sterility 1998;70:896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]