Abstract

Objective

To systematically scope and map research regarding interventions, programmes or strategies to improve maternal and newborn health (MNH) in Nigeria.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources and eligibility criteria

Systematic searches were conducted from 1 June to 22 July 2020 in PubMed, Embase, Scopus, together with a search of the grey literature. Publications presenting interventions and programmes to improve maternal or newborn health or both in Nigeria were included.

Data extraction and analysis

The data extracted included source and year of publication, geographical setting, study design, target population(s), type of intervention/programme, reported outcomes and any reported facilitators or barriers. Data analysis involved descriptive numerical summaries and qualitative content analysis. We summarised the evidence using a framework combining WHO recommendations for MNH, the continuum of care and the social determinants of health frameworks to identify gaps where further research and action may be needed.

Results

A total of 80 publications were included in this review. Most interventions (71%) were aligned with WHO recommendations, and half (n=40) targeted the pregnancy and childbirth stages of the continuum of care. Most of the programmes (n=74) examined the intermediate social determinants of maternal health related to health system factors within health facilities, with only a few interventions aimed at structural social determinants. An integrated approach to implementation and funding constraints were among factors reported as facilitators and barriers, respectively.

Conclusion

Using an integrated framework, we found most MNH interventions in Nigeria were aligned with the WHO recommendations and focused on the intermediate social determinants of health within health facilities. We determined a paucity of research on interventions targeting the structural social determinants and community-based approaches, and limited attention to pre-pregnancy interventions. To accelerate progress towards the sustainable development goal MNH targets, greater focus on implementing interventions and measuring context-specific challenges beyond the health facility is required.

Keywords: public health, obstetrics, health policy, maternal medicine, perinatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A comprehensive search strategy was used including three (3) large databases (PubMed, Embase and Scopus) as well as grey literature.

The review employed a unique framework to map the evidence and identify gaps in maternal and newborn health (MNH) research and action in Nigeria—using an integrated framework combining the WHO recommendations for MNH, the continuum of care model for maternal health and the social determinants of health.

We recognise that there may be publication bias, as not all interventions/programmes for MNH in Nigeria may have been published and captured in the study.

Introduction

Nigeria has the second highest estimated maternal deaths globally, and accounts for one of the highest neonatal mortality rates in Africa.1 2 The WHO estimates the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to be over 800 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births with a neonatal mortality rate of 33 per 1000 live births1 3 in 2019. These figures contrast with corresponding figures from the UK and the USA which are around 10–18 deaths per 100 000 live births, respectively, with neonatal mortality rates below 4 deaths per 1000 live births.1 2 Maternal and newborn health (MNH) outcomes are intricately linked; maternal deaths significantly affect newborn survival and development.4–6 The sustainable development goal (SDG) 3 calls for all countries to reduce MMRs to less than 70 per 100 000 live births and neonatal mortality to less than 12 deaths per 1000 live births by 2030.1 7 However, if current trends continue, Nigeria will fall far short of these targets despite existing efforts and resource allocations.8 Of note, the global MNH community has recently intensified efforts on innovative indicators to measure progress in MNH towards achieving the SDG targets.9–11

Most maternal deaths in Nigeria are reportedly due to preventable obstetric causes.6 Furthermore, complications of preterm birth, intrapartum events and infections account for over 80% of newborn deaths and stillbirths.1 6 12 Underlying these conditions, socioeconomic, cultural, political and environmental factors contribute to the persistently high and inequitable burden of maternal and neonatal mortality in Nigeria.7 The highest rates of deaths and morbidity occur among the poor, rural communities, where many challenges to improve MNH remain.8 13 In addition, some religious and sociocultural norms adversely influence health-seeking behaviour and expose women to discriminatory practices which pose serious health risks.8 13 Addressing these underlying social conditions and inequities will both facilitate efforts to improve maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity and may improve other dimensions of health and well-being.

Beyond the clinical causes and social determinants that underpin maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality, evidence shows that coordinated strategies across the reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health continuum of care improves the general well-being of young women and mothers and the development of newborns.4 6 Thus, the WHO recommends that the ‘essential packages of interventions for low and middle-income settings’ should be provided across the continuum of care to improve MNH.5 14–16 Such interventions include family planning, appropriate antenatal care, immediate thermal care for newborns and early initiation of exclusive breastfeeding among others. Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that addressing maternal health inequities through action on the social determinants of health can significantly improve MNH outcomes.17

It is not entirely clear why, despite laudable efforts to improve the situation in Nigeria, the burden of maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity persists.8 Understanding the evidence and gaps for maternal and neonatal health interventions and programmes will help to identify areas to focus new MNH measurement tools and direct future resource allocations.

This study aims to systematically scope and map the published literature on interventions, programmes or strategies implemented to improve MNH in Nigeria. By integrating and applying existing key frameworks in MNH,17–20 this study identifies evidence gaps that require further research and highlights areas where action is needed. The following objectives were formulated following an initial exploratory search:

Outline the types of interventions for MNH in Nigeria and their characteristics.

Describe the nature and range of evidence.

Elaborate the study settings and target populations.

Examine reported evidence of outcomes or effectiveness or impact.

Identify reported facilitators and barriers of effective implementation of interventions.

Methods

The review was conducted according to the methodological guidance for scoping reviews provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute manual for evidence synthesis.21 The main research question guiding the review was: what is the evidence available for MNH interventions in Nigeria? An intervention was defined as ‘a single or a combination of program elements or strategies designed to produce behavioural changes or improve health status, outcomes, or both among individuals or an entire population’.22 We focused on research studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions on outcomes related to MNH.

Search strategy

A preliminary database search was undertaken to identify keywords and index terms for articles related to the review topic and refine the search strategy. Thereafter, the definitive search of search of PubMed, Embase (via OVID) and Scopus (via OVID) was conducted by NN between June and July 2020 to identify relevant publications. The searches were updated in May 2021 by rerunning the searches and through email alerts. The search expressions in PubMed including keywords and MeSH terms used were: ‘Maternal Health’ OR ‘Infant, Newborn’ OR ‘Infant Health’ AND ‘Nigeria’ AND (intervention OR programme OR strategy). No filter was used to restrict results. Similar search terms were used for the other databases. A summary of the search strategy for each database is provided (online supplemental file 1). This was supplemented by a web-based search of the grey literature, and a Google scholar search using similar terms, including a directed search of relevant key organisations websites. Cited references were examined by browsing the reference lists of studies to identify additional eligible studies.

bmjopen-2021-054784supp001.pdf (32.7KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria and selection of sources of evidence

Table 1 outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the sources of evidence. The results from the searches were screened in an iterative process by two authors (NN and AKA). First, the sources were screened based on the information presented in the title and abstract. Next, full-text articles were assessed to determine their eligibility for inclusion using the criteria in table 1. Discrepancies regarding eligibility were resolved by consensus and discussion with a third author (PA).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Type of studies | Any existing literature including journal articles, systematic reviews, grey literature and evaluation reports. | Conference proceedings, study protocols, editorials, cost effectiveness studies, modelling studies or commentaries on MNH interventions. |

| Setting | Nigeria; international/ multicountry studies including Nigeria. | Studies with topics not reporting on MNH interventions in Nigeria. |

| Time period | No time limits set. | |

| Language | Studies in English. | Studies not in English. |

| Focus of study | Studies focused on maternal and newborn health (MNH) interventions/ programmes. | Studies without an intervention/programme for MNH or outcomes not focused on MNH. Studies where intervention/programme focused only on child health and did not include newborns. |

Data charting and summary

The included literature was reviewed using a data extraction form developed through an iterative process to identify the data elements critical to answering the review question and objectives. The form was piloted with 10% of the included studies to ensure consistency and revised, as necessary.

The extracted data included authors, year of publication, geographical setting, study design, target population(s), type and description of intervention, duration of implementation, reported outcomes and any facilitators or barriers.

The first author (NN) charted the data, and the second author (AKA) reviewed the data. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by a consensus involving the third author (PA) whenever necessary. In line with the scoping review methodology, a formal assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies was not undertaken, as the intention was to provide a broad overview of the existing literature related to the review question.21 Data extracted across the included sources of evidence were summarised using figures, tables and summaries.

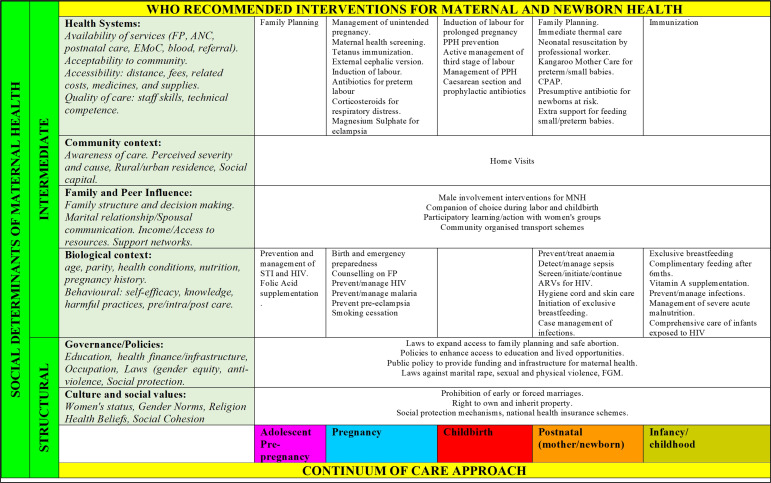

To map and summarise the evidence, we used an integrated model developed from the WHO recommended interventions for MNH,4 18 20 the continuum of care approach for maternal health19 and the social determinants of health framework17 23 (figure 1). The model combines WHO’s consensus recommendations of both clinical and non-clinical interventions for MNH as outlined in the guidelines issued in 2011 and 2017 and presents these interventions across the continuum of care for maternal, newborn and child health. We assessed whether interventions described in the included studies were in line with any of the WHO recommended interventions outlined in the model. The model also adapts the social determinants of health framework to highlight interventions aimed at addressing structural factors (such as those related to the distribution of wealth and power) and intermediary factors (such as the ability of women to access health services) which influence maternal health.

Figure 1.

Integrated framework of the WHO recommendations, continuum of care approach and social determinants of maternal health.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Ethics approval statement

Due to the nature of the study (scoping review), the study did not involve human participants.

Results

Overview of the literature search

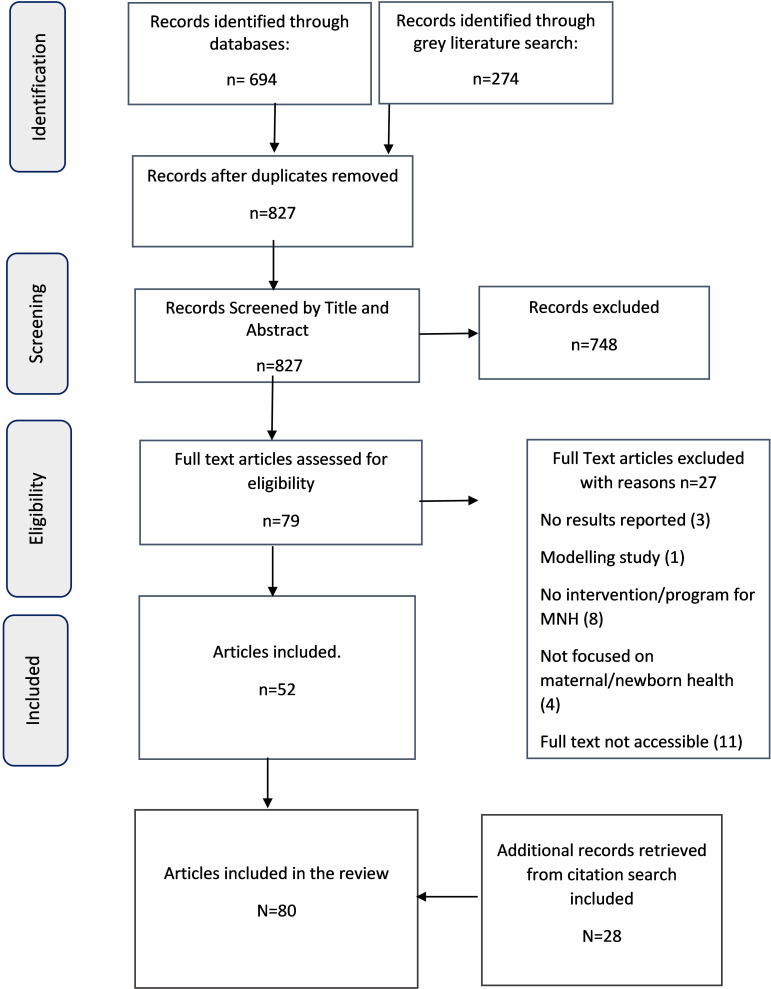

The systematic literature search resulted in 827 publications after removing duplicates. A total of 79 full texts were assessed, of which 52 were included in the review. An additional 28 articles were retrieved from citations, and the full texts were assessed and included in the review. A total of 80 publications were included in the final review.24–103 A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews flow diagram in figure 2 summarises the search results and screening processes for this study.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the selection process of sources of evidence.

Characteristics of included literature

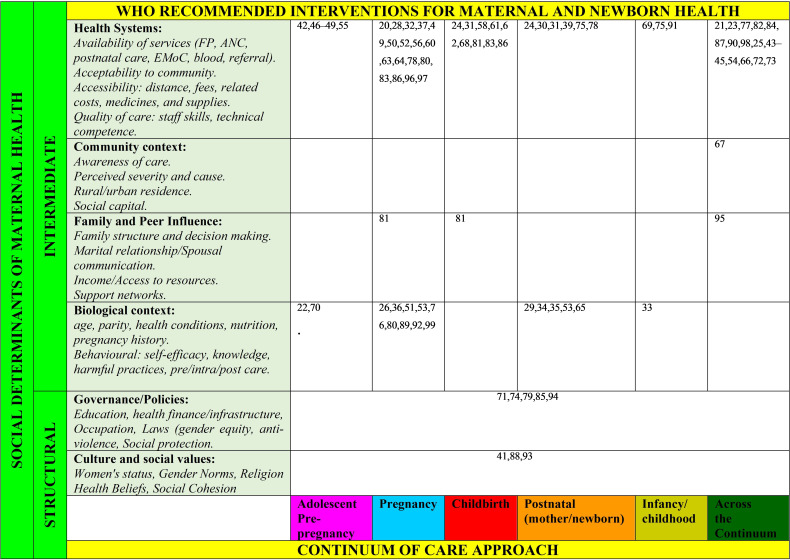

The characteristics of the included sources of evidence are summarised in table 2, and the details of each publication are presented in online supplemental table S2. Figure 3 shows the results of mapping the studies to the integrated framework developed in this study. The results are summarised below.

Table 2.

General characteristics of included sources of evidence

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Figure 3.

Mapping of interventions to the WHO recommendations, continuum of care approach and social determinants of health.

bmjopen-2021-054784supp002.pdf (275.7KB, pdf)

Intervention and programmes along the continuum of care for maternal and newborn health

Half (n=40) of the interventions targeted pregnancy, childbirth or both. Only four interventions targeted the prepregnancy stage and involved family planning or contraception services.46 50–52 Nine interventions focused on the postpartum period for mothers, newborns or both, and involved postpartum family planning,44 79 promoting early breastfeeding,38 39 neonatal resuscitation,34 keeping the baby warm,69 immunisation73 95 and a combination of essential newborn interventions.43 Just over one-third (34%, n=27) of the programmes spanned all stages of the continuum of care.

Alignment with WHO recommendations for improving maternal and newborn health

Most of the publications reviewed (71%, n=57) reported interventions aligned with the recommendations outlined in figure 2 based on the WHO 2011 and 2017 guidelines for MNH. The remaining studies (29%, n=23) aimed to improve quality or standard of MNH services mainly through capacity building of health providers, improving access through community health insurance schemes, providing free MNH services, emergency loans, conditional cash transfers and outreach services. These were not specifically listed as priority interventions in 2011 and 2017 guidelines, although may be stated elsewhere in other WHO guidance.

Mapping interventions to the social determinants of health framework for maternal health

Nearly all interventions (93%, n=74) focused on the intermediate social determinants of health. These include health system factors such as demand, access, quality and utilisation of MNH services (n=38), improving maternal health knowledge and behaviour (n=18) and improving the health status of mothers and newborns by addressing obstetric and/or newborn complications and diseases (n=18). Only six studies had interventions targeted at structural social determinants of health, including public policies, gender dynamics or sociocultural norms.45 75 78 92 97 99

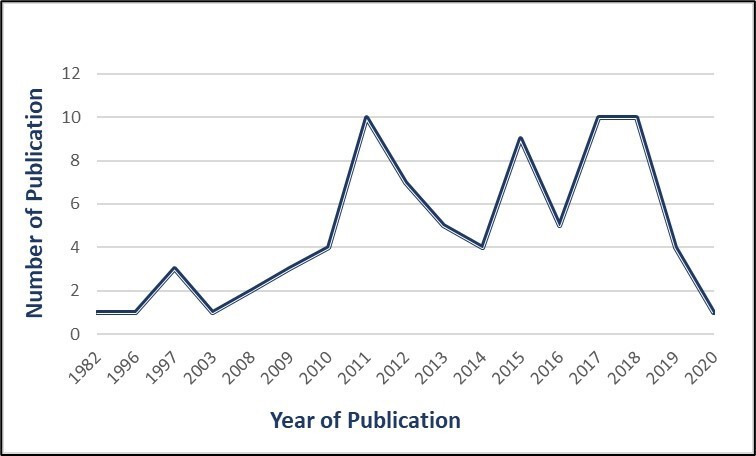

Types of studies, year of publication and lead author/institution

Of the literature included, 71 publications were journal articles and nine were programme evaluation reports. The publication year ranged from 1982 to 2020, with most sources (n=64) published between 2010 and 2018 (figure 4). The publications included in this review employed many study types/designs. One-quarter of the reviewed studies involved a process, outcome or impact evaluation (n=21), followed by quasi-experimental designs (n=16), preintervention or postintervention designs (n=15) and postintervention analysis (n=13). Nearly one-third (30%, n=24) of the reviewed studies reported having a comparison group, including eight (8) randomised control trials. Only six (6) sources used qualitative methods, and the remaining 74 were quantitative, two of which used a mixed-methods design.79 83 Over half (60%, n=48) of the reviewed articles had the lead author or institution based in Nigeria. Study duration varied as follows: less than a year (n=10), 1 year–5 years (n=53) and greater than 5 years (n=13).

Figure 4.

Number of publications per year.

Geographical region, setting and site of intervention

Based on Nigeria’s six geopolitical regions, over half (51%, n=41) of the studies reported interventions in a single region, and 21 studies reported interventions across two or more regions. About a third (n=28) of the studies were conducted in the northern regions and 21 studies in the southern regions. Thirteen studies (16%) involved settings in both the northern and southern regions. Six studies reported national coverage, including one study involving all 36 states of Nigeria and the Federal Capital Territory.75 Two studies reported multicountry sites, including Nigeria.88 100

There were fewer community-based interventions or programmes (39%, n=31) compared with those in health facilities (46%, n=37). The health facilities included ranged from primary care clinics to referral hospitals. A small portion (15%, n=12) of the studies reported both community and health facility programme sites. More studies (47.5%, n=38) were conducted in a rural setting compared with an urban environment (34%, n=27), with approximately 19% (n=15) involving both rural and urban settings.

Target populations

Most interventions in the literature reviewed (79%, n=63) were targeted mainly at pregnant women, mothers and women of childbearing age, described as 15–49 years of age, with one specifically focused on young adolescent females.42 Eleven interventions focused on healthcare providers, including community health workers and midwives.25 34 35 58 60 87 88 91 97 100 Four interventions involved community members, including the male members of the community, husbands or both.45 89 92 99 Two interventions specifically targeted policymakers.48 75

Reported outcomes, effectiveness, or impact

The interventions outlined in the reviewed literature sought to address a wide range of outcomes. Nearly half (45%, n=33) had outcomes related to improving the demand, access, coverage, quality and utilisation of essential MNH services, interventions or both. Other outcomes include reducing maternal or newborn deaths or both;24 26 27 32 34 49 60 62 64 67–69 72 78 102 improving knowledge of preventive practices and self-management;30 38 39 50 51 55 65 71 73 74 93 95 improving community participation in MNH including male members of the community;28 45 92 99 capacity building of the health workforce44 77 79 86 88 and the prevention and management of pregnancy or newborn-related diseases and complications, or both.31 35 37 40 41 57 61 66 96 103

Reported barriers and facilitators

Not all included studies reported facilitators and/or barriers of implementing the interventions. Forty-six studies (n=46) reported factors that facilitate or positively influence the intervention or programme. The most common facilitators reported were community engagement and participation (50%, n=23).24 25 27 28 31 39 41 42 45 51 53 54 63 65 77 85 91 92 98 100–102 Others included an integrated approach to implementation of interventions;31 48 85 89 98 communication of adequate (and culturally appropriate) knowledge about the programme or intervention54 65 69 103 and demand creation activities.52 53

Forty-two studies (n=42) reported barriers, with funding limitations posing the main challenge to implementation reported in 11 studies.25 27 33 53 78 80 82 86 91 92 94 Nine studies reported negative attitudes and perceptions regarding the intervention, the health system, or both as a barrier.36 39 48 53 64 71 79 82 83

Discussion

It is promising to see increasing research on maternal and neonatal health programmes in Nigeria. Following a systematic search of literature on existing interventions and programmes in Nigeria, this study used a novel framework to identify gaps for research and action on MNH interventions and programmes in Nigeria. We developed an integrated model combining the WHO recommendations for MNH with the continuum of care and the social determinants of health frameworks. This approach can provide researchers and policy makers a rigorous method to examine and assess gaps in MNH interventions and service delivery and identify country-specific priorities to focus attention.

Our findings show that the interventions in a large majority of studies in this review (71%) aligned with the WHO recommendations for MNH. Most interventions targeted the pregnancy and childbirth stages of the continuum of care. This is likely related to evidence showing that the critical causes of maternal and newborn deaths occur during these periods.7 104 Only a few studies focused on the prepregnancy stage and the provision of family planning services. This area requires further attention, as studies have shown that providing reproductive health services, mainly contraceptive services, can help with further reductions in maternal and newborn mortality.7 17 104

Accordingly, most studies examined the intermediate social determinants of health, such as access to and availability of relevant health services within health facilities, with only a few investigating programmes aimed at the more structural social determinants of health, such as gender, cultural and religious norms and public policies. Although these proximal social determinants remain essential, growing evidence emphasises the significant role of distal determinants influencing maternal health and its outcomes.17 104 Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests actions to improve these distal social determinants can improve MNH outcomes.17 This highlights the need for further research on how social interventions affect maternal and neonatal health outcomes in Nigeria to inform programme development and implementation.

Of the 80 publications reviewed, over 80% reported achieving the interventions’ intended outcomes. Many of the programmes investigated interventions related to WHO recommendations, with a focus on women and their engagement with health facilities. Our review also highlights the focus of existing programmes on measuring coverage of evidence-based MNH interventions in health facilities, with limited attention to community-based interventions. Importantly, the research synthesised does not clearly show whether these interventions were chosen to align with country-level priorities. Consequently, to accelerate progress towards the SDG goals of ending preventable maternal and newborn deaths, a broader lens to identify and measure critical and context-specific factors beyond the health facility is required. Country level researchers may be better posed to understand and highlight country-level priorities for MNH research. Of note, international collaborators led over a third of the research in this review. Going forward, we implore global health institutions to actively improve local research capacity and funding as articulated by the African Academy of Science.105 106

Factors that facilitated achieving intended outcomes involved engagement with the communities and integration of multiple interventions. This result supports the call for the application of integrated packages of effective health interventions across the continuum of care, re-emphasised by the strategic plans to achieve SDG 3.19 104 In addition, these findings highlight the role of participatory mechanisms to engage families (including men) and communities in improving MNH.17 Two key barriers to interventions achieving their intended health outcomes were funding limitations and negative attitudes and perceptions. This may be related to the need for public engagement to address participants’ critical concerns and the need for more integrated interventions.

The search strategy was limited to PubMed, Embase and Scopus databases; thus, publications in excluded databases might be missing in this review. Nevertheless, we conducted a grey literature search alongside these databases to cover other relevant resources. Although we carefully considered the search terms used in our strategy, we recognise that there may be publication bias, as not all interventions/programmes for MNH will have been published.

A broad range of study designs were employed in the studies included in this review. However, most employed quantitative approaches with only a small fraction using qualitative and mixed-methods approaches. Given the nature of MNH interventions and the complexity of the challenges facing women and newborns, multidisciplinary research and mixed-methods approaches are needed to add depth to understanding the contextual nuances of MNH. This helps to uncover unknown and emerging factors which potentially informs better use of limited resources. An important domain to consider within the spectrum of factors that can influence MNH outcomes is the quality of services received by women and children,107 especially if they suffer mistreatment.108 109

Conclusion

Using a novel framework combining WHO recommendations for MNH, the continuum of care and the social determinants of health frameworks, most MNH interventions were aligned with the WHO recommendations and focused on the proximal social determinants of health. These were related largely to health system factors within health facilities. In addition, our findings show only a few programmes targeting the structural social determinants of maternal health such as religious and cultural barriers and MNH policies and highlights the relative neglect of non-facility-based interventions. The evidence evaluating MNH outcomes was mostly quantitative and with only a few benefiting from qualitative and mixed-methods approaches, thus limiting the exploration of contextual factors that influence MNH outcomes. Therefore, efforts to improve MNH in Nigeria and other similar contexts may need to focus greater attention on implementing MNH interventions and measuring context-specific challenges beyond the health facility. This may help to accelerate progress towards the SDG goal of ending preventable maternal and newborn deaths.

bmjopen-2021-054784supp003.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @naimanasir, @ade_aderoba

Contributors: The conception and design of the research was conducted by all authors (NN, AKA and PA). Data collection and analysis and interpretation of results were conducted by NN, AKA and PA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by NN, and AKA and PA contributed to this version. All authors contributed to subsequent revisions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. NN acts as guarantor for this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data for the study are included in the manuscript and supplementary materials. No other data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) . Levels and trends in child mortality 2018 report: estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. New York, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division [online], 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/193994/WHO_RHR_15.23_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 9 Aug 2019].

- 3.World Health Organization . Maternal health in Nigeria: generating information for action [online]. Available: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/maternal-health-nigeria/en/ [Accessed 22 Nov 2020].

- 4.The Partnership for Maternal Newborn and Child Health . Essential interventions, commodities and guidelines for reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health [online]. Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/part_publications/essential_interventions_18_01_2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.United Nations . MDG report 2015. In: Disease control priorities: reproductive, Maternal, newborn, and child health [online]. Vol. 2. 3rd edn. The World Bank, 2016: 1–23. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/full/10.1596/978-1-4648-0348-2_ch1 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burchett HE, Mayhew SH. Maternal mortality in low-income countries: what interventions have been evaluated and how should the evidence base be developed further? Int J Gynecol Obstet 2009;105:78–81. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black RE, Levin C, Walker N, et al. Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: key messages from disease control priorities 3rd edition. Lancet 2016;388:2811–24. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00738-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Izugbara CO, Wekesah FM, Adedini SA. Maternal health in Nigeria: a situation update. Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchant T, Boerma T, Diaz T, et al. Measurement and accountability for maternal, newborn and child health: fit for 2030? BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002697. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grove J, Claeson M, Bryce J, et al. Maternal, newborn, and child health and the sustainable development goals—a call for sustained and improved measurement. Lancet 2015;386:1511–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00517-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maternal Health Taskforce . Who decides what matters in maternal and newborn health measurement? [online], 2021. Available: https://www.mhtf.org/2021/02/24/who-decides-what-matters-in-maternal-and-newborn-health-measurement/ [Accessed 26 Apr 2021].

- 12.Ezeh OK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ, et al. Determinants of neonatal mortality in Nigeria: evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ujah IAO, Aisien OA, Mutihir JT, et al. Factors contributing to maternal mortality in north-central Nigeria: a seventeen-year. Afr J Reprod Health 2005;9:27–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lassi ZS, Mansoor T, Salam RA, et al. Essential pre-pregnancy and pregnancy interventions for improved maternal, newborn and child health. Reprod Health 2014;11:S2. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lassi ZS, Middleton PF, Crowther C, et al. Interventions to improve neonatal health and later survival: an overview of systematic reviews. EBioMedicine 2015;2:985–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salam RA, Mansoor T, Mallick D, et al. Essential childbirth and postnatal interventions for improved maternal and neonatal health. Reprod Health 2014;11:S3. 10.1186/1742-4755-11-S1-S3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNDP . Discussion paper: a social determinants approach to maternal health. Roles for development actors, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on newborn health: guidelines approved by the WHO Guidelines Review Committee [online]. Geneva, 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/newborn-health-recommendations/en/

- 19.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, et al. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007;370:1358–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . WHO recommendations on maternal health. Guidelines approved by the WHO guidelines review committee, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis [online], 2020. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Google Scholar]

- 22.Intervention MICA: Building Healthy Communities . What is an intervention? [online], 2017. Available: https://health.mo.gov/data/interventionmica/ [Accessed 6 Apr 2021].

- 23.Hamal M, Dieleman M, De Brouwere V, et al. Social determinants of maternal health: a scoping review of factors influencing maternal mortality and maternal health service use in India. Public Health Rev 2020;41:13. 10.1186/s40985-020-00125-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloan NL, Storey A, Fasawe O, et al. Advancing survival in Nigeria: a pre-post evaluation of an integrated maternal and neonatal health program. Matern Child Health J 2018;22:986–97. 10.1007/s10995-018-2476-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oguntunde O, Surajo IM, Dauda DS, et al. Overcoming barriers to access and utilization of maternal, newborn and child health services in northern Nigeria: an evaluation of facility health committees. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:104. 10.1186/s12913-018-2902-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alexander DA, Northcross A, Karrison T, et al. Pregnancy outcomes and ethanol cook stove intervention: a randomized-controlled trial in Ibadan, Nigeria. Environ Int 2018;111:152–63. 10.1016/j.envint.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abegunde D, Orobaton N, Sadauki H, et al. Countdown to 2015: tracking maternal and child health intervention targets using lot quality assurance sampling in Bauchi state Nigeria. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129129. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cannon M, Charyeva Z, Oguntunde O, et al. A case study of community-based distribution and use of misoprostol and chlorhexidine in Sokoto state, Nigeria. Glob Public Health 2017;12:1553–67. 10.1080/17441692.2016.1172102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Findley SE, Uwemedimo OT, Doctor HV, et al. Early results of an integrated maternal, newborn, and child health program, Northern Nigeria, 2009 to 2011. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1034. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishola G, Fayehun F, Isiugo-Abanihe U, et al. Effect of volunteer household counseling in improving knowledge of birth preparedness and complication readiness of pregnant women in northwest Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2017;21:39–48. 10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orobaton N, Austin AM, Abegunde D, et al. Scaling-up the use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: results and lessons on scalability, costs and programme impact from three local government areas in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Malar J 2016;15:1–24. 10.1186/s12936-016-1578-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezugwu EC, Agu PU, Nwoke MO, et al. Reducing maternal deaths in a low resource setting in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2014;17:62–6. 10.4103/1119-3077.122842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orobaton N, Abegunde D, Shoretire K, et al. A report of at-scale distribution of chlorhexidine digluconate 7.1% gel for newborn cord care to 36,404 newborns in Sokoto State, Nigeria: Initial lessons learned. PLoS One 2015;10:e0134040. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Disu EA, Ferguson IC, Njokanma OF, et al. National neonatal resuscitation training program in Nigeria (2008-2012): a preliminary report. Niger J Clin Pract 2015;18:102–9. 10.4103/1119-3077.146989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwast BE. Reduction of maternal and perinatal mortality in rural and peri-urban settings: what works? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1996;69:47–53. 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02535-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eluwa GI, Adebajo SB, Torpey K, et al. The effects of centering pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes in northern Nigeria; a prospective cohort analysis. BMC Preg Child 2018;18:158. 10.1186/s12884-018-1805-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sam-Agudu NA, Ramadhani HO, Isah C, et al. The impact of structured mentor mother programs on presentation for early infant diagnosis testing in rural north-central Nigeria: a prospective paired cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:S182–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qureshi AM, Oche OM, Sadiq UA, et al. Using community volunteers to promote exclusive breastfeeding in Sokoto state, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 2011;10:8. 10.4314/pamj.v10i0.72215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies-Adetugbo AA, Adebawa HA. The Ife South breastfeeding project: training community health extension workers to promote and manage breastfeeding in rural communities. Bull World Health Organ 1997;75:323–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ojofeitimi EO, Elegbe I, Babafemi J. Diet restriction by pregnant women in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1982;20:99–103. 10.1016/0020-7292(82)90019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danmusa S, Coeytaux F, Potts J. Expanding use of magnesium sulfate for treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia building towards scale in Nigeria [online], 2014. Available: https://www.macfound.org/media/files/MagSulfateFINAL.pdf [Accessed 9 Jun 2020].

- 42.Maternal Newborn and Child Health Program (MNCH2) . Case study No.4: providing hard-to-reach communities in northern Nigeria with RMNCH services [online], 2017. Available: https://www.mnch2.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/4-FINAL-SCREEN_Case_Study_Outreach_MNCH2_2017.pdf

- 43.USAID/Maternal and Child Survival Program . Strengthening newborn care: Kogi and Ebonyi states Nigeria, 2018. https://www.mcsprogram.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) . Increasing family planning uptake among postpartum women [online], 2018. Available: https://www.mcsprogram.org/

- 45.Maternal Newborn and Child Health Program (MNCH2) . Case study No. 6: male motivators in communities: uniting men on the importance of women’s health [online], 2017. Available: http://resources.jhpiego.org/

- 46.Maternal Newborn and Child Health Program (MNCH2) . Case study No. 7: increasing the uptake of long acting reversible contraception services in primary health centres through competency-based training [online], 2016. Available: http://resources.jhpiego.org/

- 47.Abegunde D, Orobaton N, Shoretire K, et al. Monitoring maternal, newborn, and child health interventions using lot quality assurance sampling in Sokoto State of northern Nigeria. Glob Health Action 2015;8:27526. 10.3402/gha.v8.27526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mckaig C, Charurat E, Sasser E. An assessment of integration of family planning and maternal, newborn and child health in Kano, Nigeria [online]. Maryland, 2009. Available: www.jhpiego.org [Accessed 9 Jun 2020].

- 49.Kana MA, Doctor HV, Peleteiro B, et al. Maternal and child health interventions in Nigeria: a systematic review of published studies from 1990 to 2014. BMC Public Health 2015;15:334. 10.1186/s12889-015-1688-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdul-Hadi RA, Abass MM, Aiyenigba BO, et al. The effectiveness of community based distribution of injectable contraceptives using community health extension workers in Gombe State, Northern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2013;17:80–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Speizer IS, Corroon M, Calhoun L, et al. Demand generation activities and modern contraceptive use in urban areas of four countries: a longitudinal evaluation. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2:410–26. 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hotchkiss DR, Godha D, Do M. Effect of an expansion in private sector provision of contraceptive supplies on horizontal inequity in modern contraceptive use: evidence from Africa and Asia. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:33. 10.1186/1475-9276-10-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fayemi M, Momoh G, Oduola O, et al. Community based distribution agents’ approach to provision of family planning information and services in five Nigerian States: a mirage or a reality? Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2011;3. 10.4102/phcfm.v3i1.228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogu R, Okonofua F, Hammed A, et al. Outcome of an intervention to improve the quality of private sector provision of postabortion care in northern Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;118:S121–6. 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60010-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mens PF, Scheelbeek PF, Al Atabbi H, et al. Peer education: the effects on knowledge of pregnancy related malaria and preventive practices in women of reproductive age in Edo State, Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2011;11:610. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNabb M, Chukwu E, Ojo O, et al. Assessment of the quality of antenatal care services provided by health workers using a mobile phone decision support application in northern Nigeria: a pre/post-intervention study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123940. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Anyaehie U, Nwagha UI, Aniebue PN, et al. The effect of free distribution of insecticide-treated nets on asymptomatic Plasmodium parasitemia in pregnant and nursing mothers in a rural Nigerian community. Niger J Clin Pract 2011;14:19–22. 10.4103/1119-3077.79234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kabo I, Otolorin E, Williams E, et al. Monitoring maternal and newborn health outcomes in Bauchi State, Nigeria: an evaluation of a standards-based quality improvement intervention. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:566–72. 10.1093/intqhc/mzw083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chabikuli NO, Awi DD, Chukwujekwu O, et al. The use of routine monitoring and evaluation systems to assess a referral model of family planning and HIV service integration in Nigeria. AIDS 2009;23:S97–103. 10.1097/01.aids.0000363782.50580.d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalu CA, Umeora O, Sunday-Adeoye I. Review of post-abortion care in south-eastern Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 2012;16:105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Joseph O, Biodun O, Michael E. Pregnancy outcome among HIV positive women receiving antenatal HAART versus untreated maternal HIV infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2011;21:356–9. doi:07.2011/JCPSP.356359 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ojengbede OA, Morhason-Bello IO, Galadanci H, et al. Assessing the role of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment in reducing mortality from postpartum hemorrhage in Nigeria. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2011;71:66–72. 10.1159/000316053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chiwuzie J, Okojie O, Okolocha C, et al. Emergency loan funds to improve access to obstetric care in Ekpoma, Nigeria. The Benin PMM team. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1997;59:S231–6. 10.1016/S0020-7292(97)00170-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tukur J, Ahonsi B, Ishaku SM, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes after introduction of magnesium sulphate for treatment of preeclampsia and eclampsia in selected secondary facilities: a low-cost intervention. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1191–8. 10.1007/s10995-012-1105-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prata N, Ejembi C, Fraser A, et al. Community mobilization to reduce postpartum hemorrhage in home births in northern Nigeria. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1288–96. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hunyinbo K, Fawole A, Sotiloye O. Evaluation of criteria-based clinical audit in improving quality of obstetric care in a developing country hospital. Afr J Reprod Health 2008;12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Okonofua FE, Ogu RN, Fabamwo AO, et al. Training health workers for magnesium sulfate use reduces case fatality from eclampsia: results from a multicenter trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2013;92:716–20. 10.1111/aogs.12135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Igwegbe AO, Eleje GU, Ugboaja JO, et al. Improving maternal mortality at a university teaching hospital in Nnewi, Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2012;116:197–200. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh K, Khan SM, Carvajal-Aguirre L, et al. The importance of skin-to-skin contact for early initiation of breastfeeding in Nigeria and Bangladesh. J Glob Health 2017;7:020505. 10.7189/jogh.07.020505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Galadanci H, Künzel W, Shittu O, et al. Obstetric quality assurance to reduce maternal and fetal mortality in Kano and Kaduna state hospitals in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2011;114:23–8. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gummi FB, Hassan M, Shehu D, et al. Community education to encourage use of emergency obstetric services, Kebbi state, Nigeria. The Sokoto PMM team. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1997;59:S191–200. 10.1016/S0020-7292(97)00165-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miller S, Ojengbede O, Turan JM, et al. A comparative study of the non-pneumatic anti-shock garment for the treatment of obstetric hemorrhage in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;107:121–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Odusanya OO, Alufohai JE, Meurice FP, et al. Short term evaluation of a rural immunization program in Nigeria. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:175–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amoran OE. Impact of health education intervention on malaria prevention practices among nursing mothers in rural communities in Nigeria. Niger Med J 2013;54:115. 10.4103/0300-1652.110046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Okonofua F, Lambo E, Okeibunor J, et al. Advocacy for free maternal and child health care in Nigeria-Results and outcomes. Health Policy 2011;99:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Findley SE, Uwemedimo OT, Doctor HV, et al. Comparison of high- versus low-intensity community health worker intervention to promote newborn and child health in northern Nigeria. Int J Womens Health 2013;5:717–28. 10.2147/IJWH.S49785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pathfinder International . The maternal health care improvement initiative: Nigeria [online], 2011. Available: https://www.pathfinder.org/publications/maternal-health-care-improvement-initiative-nigeria/ [Accessed 6 Jul 2020].

- 78.Galadanci HS, Idris SA, Sadauki HM. Programs and policies for reducing maternal mortality in Kano state, Nigeria: a review: original research article. Afr J Reprod Health 2010;14. [Google Scholar]

- 79.et alCharurat E, Nasir B, Airede RL. Postpartum systematic screening in Northern Nigeria: a practical application of family planning and maternal newborn and child health integration [online]. USAID-ACCESS-FP Report, 2010. Available: http://resources.jhpiego.org/system/files/resources/ACCESS-FP_Nigeria_PPSS_Report.pdf [Accessed 7 Jul 2020].

- 80.Omole O, Ijadunola MY, Olotu E, et al. The effect of mobile phone short message service on maternal health in south-west Nigeria. Int J Health Plann Manage 2018;33:155–70. 10.1002/hpm.2404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okoli U, Morris L, Oshin A, et al. Conditional cash transfer schemes in Nigeria: potential gains for maternal and child health service uptake in a national pilot programme. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:408. 10.1186/s12884-014-0408-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu JX, Shen J, Wilson N, et al. Conditional cash transfers to prevent mother-to-child transmission in low facility-delivery settings: evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:32. 10.1186/s12884-019-2172-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edu BC, Agan TU, Monjok E, et al. Effect of free maternal health care program on health-seeking behaviour of women during pregnancy, intra-partum and postpartum periods in cross river state of Nigeria: a mixed method study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2017;5:370–82. 10.3889/oamjms.2017.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noguchi L, Grenier L, Kabue M, et al. Effect of group versus individual antenatal care on uptake of intermittent prophylactic treatment of malaria in pregnancy and related malaria outcomes in Nigeria and Kenya: analysis of data from a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Malar J 2020;19:51. 10.1186/s12936-020-3099-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oguntunde O, Yusuf FM, Nyenwa J, et al. Emergency transport for obstetric emergencies: integrating community-level demand creation activities for improved access to maternal, newborn, and child health services in northern Nigeria. Int J Womens Health 2018;10:773–82. 10.2147/IJWH.S180415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lalonde AB, Grellier R. FIGO saving mothers and newborns initiative 2006-2011. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2012;119:S18–21. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Okeke E, Glick P, Chari A, et al. The effect of increasing the supply of skilled health providers on pregnancy and birth outcomes: evidence from the midwives service scheme in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:425. 10.1186/s12913-016-1688-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ameh CA, Kerr R, Madaj B, et al. Knowledge and skills of healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia before and after competency-based training in emergency obstetric and early newborn care. PLoS One 2016;11:e0167270. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brals D, Aderibigbe SA, Wit FW, et al. The effect of health insurance and health facility-upgrades on hospital deliveries in rural Nigeria: a controlled interrupted time-series study. Health Policy Plan 2017;32:990–1001. 10.1093/heapol/czx034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Okeke EN, Pitchforth E, Exley J, et al. Going to scale: design and implementation challenges of a program to increase access to skilled birth attendants in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:356. 10.1186/s12913-017-2284-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Okereke E, Tukur J, Aminu A, et al. An innovation for improving maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) service delivery in Jigawa State, Northern Nigeria: a qualitative study of stakeholders’ perceptions about clinical mentoring. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:64. 10.1186/s12913-015-0724-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oguntunde O, Nyenwa J, Yusuf FM, et al. The experience of men who participated in interventions to improve demand for and utilization of maternal and child health services in northern Nigeria: a qualitative comparative study. Reprod Health 2019;16:104. 10.1186/s12978-019-0761-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adaji SE, Jimoh A, Bawa U, et al. Women’s experience with group prenatal care in a rural community in northern Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2019;145:164–9. 10.1002/ijgo.12788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Onwujekwe O, Obi F, Ichoku H, et al. Assessment of a free maternal and child health program and the prospects for program re-activation and scale-up using a new health fund in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2019;22:1516–29. 10.4103/njcp.njcp_503_18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brown VB, Oluwatosin OA, Akinyemi JO, et al. Effects of community health nurse-led intervention on childhood routine immunization completion in primary health care centers in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Community Health 2016;41:265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Asa OO, Onayade AA, Fatusi AO, et al. Efficacy of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine in preventing anaemia in pregnancy among Nigerian women. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:692–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Walker J-A, Hashim Y, Oranye N. Impact of Muslim opinion leaders’ training of healthcare providers on the uptake of MNCH services in Northern Nigeria. Glob Public Health 2019;14:200–13. 10.1080/17441692.2018.1473889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ehigiegba A, Adibe N, Ekott M. Making community and clinic-based PMTCT services more accessible: the role of a community health insurance scheme: a Nigerian cottage Hospital experience. J Med Biomed Res 2012;11. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adeleye OA, Aldoory L, Parakoyi DB. Using local culture and gender roles to improve male involvement in maternal health in southern Nigeria. J Health Commun 2011;16:1122–35. 10.1080/10810730.2011.571340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haver J, Brieger W, Zoungrana J, et al. Experiences engaging community health workers to provide maternal and newborn health services: implementation of four programs. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;130:S32–9. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Okeibunor JC, Orji BC, Brieger W, et al. Preventing malaria in pregnancy through community-directed interventions: evidence from Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. Malar J 2011;10:227. 10.1186/1475-2875-10-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Findley SE, Doctor HV, Ashir GM, et al. Reinvigorating health systems and community-based services to improve maternal health outcomes: case study from Northern Nigeria. J Prim Care Community Health 2015;6:88–99. 10.1177/2150131914549383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Leight J, Sharma V, Brown W, et al. Associations between birth kit use and maternal and neonatal health outcomes in rural Jigawa state, Nigeria: a secondary analysis of data from a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208885. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chou D, Daelmans B, Jolivet RR, et al. Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths. BMJ 2015;351:h4255–22. 10.1136/bmj.h4255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.The African Academy of Sciences, The Academy of Medical Sciences . From minding the gap to closing the gap: science to transform maternal and newborn survival and stillbirths in sub-Saharan Africa in the sustainable development goals era. Nairobi, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marincola E, Kariuki T. Quality research in Africa and why it is important. ACS Omega 2020;5:24155–7. 10.1021/acsomega.0c04327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Tunçalp Ó¦, Were WM, MacLennan C. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns the WHO vision. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2015;122:1045–9. 10.1111/1471-0528.13451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Bohren MA, Mehrtash H, Fawole B, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys. Lancet 2019;394:1750–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31992-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sacks E, Mehrtash H, Bohren M, et al. The first 2 H after birth: prevalence and factors associated with neonatal care practices from a multicountry, facility-based, observational study. Lancet Global Health 2021;9:e72–80. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30422-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-054784supp001.pdf (32.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-054784supp002.pdf (275.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2021-054784supp003.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data for the study are included in the manuscript and supplementary materials. No other data are available.