Abstract

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a congenital structural anomaly in which the diaphragm has not developed properly. It may occur either as an isolated anomaly or with additional anomalies. It is thought to be a multifactorial disease in which genetic factors could either substantially contribute to or directly result in the developmental defect. Patients with aneuploidies, pathogenic variants or de novo Copy Number Variations (CNVs) impacting specific genes and loci develop CDH typically in the form of a monogenetic syndrome. These patients often have other associated anatomical malformations. In patients without a known monogenetic syndrome, an increased genetic burden of de novo coding variants contributes to disease development. In early years, genetic evaluation was based on karyotyping and SNP-array. Today, genomes are commonly analyzed with next generation sequencing (NGS) based approaches. While more potential pathogenic variants are being detected, analysis of the data presents a bottleneck—largely due to the lack of full appreciation of the functional consequence and/or relevance of the detected variant. The exact heritability of CDH is still unknown. Damaging de novo alterations are associated with the more severe and complex phenotypes and worse clinical outcome. Phenotypic, genetic—and likely mechanistic—variability hampers individual patient diagnosis, short and long-term morbidity prediction and subsequent care strategies. Detailed phenotyping, clinical follow-up at regular intervals and detailed registries are needed to find associations between long-term morbidity, genetic alterations, and clinical parameters. Since CDH is a relatively rare disorder with only a few recurrent changes large cohorts of patients are needed to identify genetic associations. Retrospective whole genome sequencing of historical patient cohorts using will yield valuable data from which today's patients and parents will profit Trio whole genome sequencing has an excellent potential for future re-analysis and data-sharing increasing the chance to provide a genetic diagnosis and predict clinical prognosis. In this review, we explore the pitfalls and challenges in the analysis and interpretation of genetic information, present what is currently known and what still needs further study, and propose strategies to reap the benefits of genetic screening.

Keywords: foregut, genetics, development, counseling, diaphragm, hernia, discordant monozygotic twin, congenital

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) [OMIM: 142340] has an estimated incidence of 1 in 1,750–5,880 live births (1–3) and is characterized by a defect of the diaphragm. This defect allows herniation of the abdominal organs into the thorax. CDH can be detected prenatally during first or second trimester ultrasounds in 50–68% of CDH pregnancies (4–7). Patients are often referred to a center of expertise with a specialized multidisciplinary team for prenatal assessment, prognostic and genetic counseling and care. CDH prevalence has slightly increased in the past years (3). Still, the mortality rates have decreased, probably due to better treatment strategies (8), although this decline is more pronounced in wealthier coutnries than in developing countries (9).

Most of what we know of human diaphragm development is based on descriptive and functional analyses of animal models. The diaphragm muscle develops initially from transient structures located at the top of the liver: the septum transversum, the pleuroperitoneal folds, the posthepatic mesenchymal plate, and the somites. Myoblast progenitors and other mesenchymal cells (10) in the developing pleuroperitoneal folds expand and migrate to the posthepatic mesenchymal plate. Vice versa, cells from the posthepatic mesenchymal plate migrate toward the pleuroperitoneal folds. Finally, the pleuroperitoneal folds fuse with the posthepatic mesenchymal plate between embryonic day (E) E12.5 and E13.5 (10, 11). When complete, this membrane separates the thoracic and abdominal cavity (E14.5). In CDH, this process is disrupted and the diaphragm will not fully close (12, 13). A more detailed description of diaphragm and CDH development can be found elsewhere in this issue (14).

Patients with aneuploidies, pathogenic single nucleotide variants, de novo Copy Number Variations (CNVs) (15–18) develop CDH, often in the form of a monogenetic syndrome and in combination with other anatomical malformations (2, 19). Here, we discuss what is currently known and inventoried what is necessary to provide optimal genetic counseling for the individual patients and their parents. We evaluate genetic outcome of a CDH cohort in the Erasmus MC-Sophia Children's Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and propose strategies to reap the benefits of genetic screening.

CDH Has Subtypes Based on Defect Size, Type and Anatomical Location

CDH is the most severe diaphragm defects compared to other, less frequent defects such as incomplete muscularization of the diaphragm (diaphragmatic eventration) or the presence of just a thin layer of non-muscular tissue (sac hernia). Subtypes are identified by the size and anatomical location of the herniation. Most prevalent are Bochdalek hernias, which are mostly left-sided (20). Prenatal predictors for survival include associated malformations (21), defect size (7), lung volume (22), liver herniation (23), stomach position (24, 25), and lung-to-head ratio (26, 27). Other predictors include birth weight, Apgar score, respiratory parameters, cardiac anomalies, chromosomal changes, and pulmonary hypertension (28–30).

The Relation of Defect Size and Genetic Alterations

Larger diaphragms defects are associated with a higher mortality rate, the prevalence of associated anatomical malformations as well as the number of associated anatomical malformations (21). We hypothesized that large continuous locus or gene changes (e.g., 15q26 loss, 17q12 loss; see Table 1) can modify multiple genes involved in diaphragm formation, and impact the development of the embryo in general. In contrast, small deletions or Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) as seen in for instance FBN1, TGFB3, and SLC2A10 (see Table 2) will be associated with smaller defects. Therefore, we evaluated whether the size of the defect was associated with the finding of “a pathogenic genomic variant” and/or “a genetic syndrome.” We compared the genetic test results and the defect size classification (n = 336). Statistical analysis did not indicate associations of the defect size with an different, uncommon genetic test result. What we did observed was that patients with no or little follow-up revealed associations (P < 0.001). In this category patients are present lacking a registered defect size or registered genetic test. This category includes patients who have not been subjected to an intervention due to intrauterine fetal demise or termination of pregnancy. In the Netherlands, pregnancies in which severe genetic anomalies (e.g., Edwards syndrome, Patau syndrome) or structural malformations are observed that are incompatible with life, are often terminated. The CDH defect size is not determined in those cases (see Table 1). Therefore, a complete genetic and phenotypic evaluation and subsequent association analysis in this particular group is difficult and often not performed.

Table 1.

Pathogenic alterations in CDH patients of which the defect size was not registered.

| Defect size (n) | Syndrome (n) | n | Death | Chromosome | Type | Inheritance | Zygosity | Genetic change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR (n = 41) | Microdeletion | 1 | NR | 3p26.3-p25.3 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg18] 3p26.3-p25.3 (0–9398383) x1 |

| Microduplication | NR | 11q23.3-q25 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg18] 11q23.3-q25 (16192532–134452384) x3 | ||

| Microdeletion | 1 | NR | 5p15 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg19] 5p15 (0–37,299,510) x1, | |

| Microduplication | NR | 12p13.3 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg19] 12p13.31 (9,909,002–10,021,222) x 3 | ||

| Cornelia de lange | 1 | N | 5p13.2 | Missense | de novo | het | NM_1334333 (NIPBL): c.3574G>A; p. (Glu1192Lys) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | T | 7q11.23 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg18] 7q11.23 (72,701,018–74,143,000) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | NR | 8p23 | Gain | ut | het | 46, XY, der (8) t (3;8) (p23; p23.1) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | D | 9p24.3-p13.1 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg18] 9p24.3p13.1 (0–39,155,853) x4, arr[hg18]9p13.1p11.2 (39,155,853–46,468,856) x3 | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | T | 9q31.1q31.2 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg19] 9q31.1q31.2 (105,034,238–111,044,933) x1 | |

| Trisomy 9 | 1 | I | 9 | Aneuploidy | de novo | het | 47, XX, +9(20)/46, XX (4) | |

| Mosaic MYRF gene | 1 | N | 11q12.2 | Splicing | de novo | het | NM_001127392.2 (MYRF): c.46+2T>C(r.spl?) | |

| Pallister Killian syndrome | 3 | T (1), NR (2) | 12p10 | Gain | de novo | het | 47, XX/XY, +i (12) (p10) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | D | 12q24.3 | Gain | ut | het | 46, XY, der (12) t (11,12) (q23.3; q24.3) | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | T | 13q12 | Loss | de novo | het | 46, XY, del (13) (q12?) (8)/46, XY (35) | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | T | 13q21.31q32.3 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg19]13q21.31q32.3 (64,535,372–98,354,979) x1 | |

| Patau syndrome | 3 | T (1), D (1), NR (1) | 13 | Aneuploidy | de novo | het | 47, XX +13 | |

| Isochromosome 14q | 1 | N | 14q10 | Gain | de novo | het | 46, XX, i (14) (q10) (3)/46, XX (22) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | NR | 15 | ut | het | 46, XX, der (15) t (2;15) | ||

| Microdeletion | 1 | D | 15q26 | Loss | de novo | het | 46, XY, t (1;14) (p22; q13), inv (6) (p25q22), del (15) (q26) | |

| Edward's syndrome | 16 | T (3), I (1), N (2), D (3), NR (9) | 18 | Aneuploidy | de novo | het | 47 XX / XY + 18 | |

| Down syndrome | 1 | NR | 21 | Aneuploidy | de novo | het | 47, XX +21 | |

| Cat eye syndrome | 1 | T | 22q11.1q11.21 | Gain | de novo | het | arr [hg19] 22q11.1q11.21 (14,449,498–17,017,139) x4 | |

| XY reversal* | 2 | D (2) | XY | ? | de novo | het | ? |

Genetic tests included karyotyping, SNP array or Whole exome sequencing. AR, Autosomal recessive; XLR, X-linked recessive; CH, compound heterozygote; n, number of patients; ut, unbalanced translocation.

Table 2.

Pathogenic alterations in CDH patients of which the defect size was registered.

| Defect size (n) | Syndrome (n) | n | Death | Chromosome | Type | Inheritance | Zygosity | Genetic change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (n = 10) | Wolf Hirschshorn Syndrome | 1 | NR | 4p156.3 | Loss | de novo | het | 46, XY FISH: ish del (4) (p16.3p16.3) (D4S96-) |

| Louys-Dietz syndrome V | 1 | NR | 14q24 | Frameshift | AD | het | NM_003239.4 (TGFB3): c.232del.G, p. (Glu78fs) | |

| Marfan syndrome | 1 | NR | 15q21.1 | Frameshift | AD | het | NM_000138.5 (FBN1):c1301_1302del, p. (Tyr434Serfs*17) | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | NR | 16p13.3 | Loss | de novo | het | 46, XY arr[hg18] 16p13.3 (154,014–174,381) x1 | |

| Arterial tortuosity syndrome | 1 | NR | 20q13 | Missense | AR | hom | NM_030777.4 (SLC2A10): c.127 6G>T, p. (Gly426Trp) | |

| Down syndrome | 4 | D (1), NR (3) | 21 | Aneuploidy | de novo | het | 47, XX / 47, XY + 21 | |

| Down syndrome | 1 | NR | 21 | Aneuploidy | ut | het | 46, XY, t (15;21) (p12; p12) | |

| B (n = 4) | Microduplication | 1 | NR | 4p15.2p14 | Gain | de novo | het | arr [hg18] 4p15.2p14 (224,500,018–38,700,366) x3 |

| Sotos syndrome | 1 | NR | 5q35.2 | Missense | de novo | het | NM_022455.5 (NSD1): c.5685C>G, p. (Cys1895Tyrp) | |

| Microduplication | 1 | NR | 7q31.33–36.3 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg19]7q31.33q36.3 (125839750_159124173) x3[0.2]/arr[hg19]7q31.33q36.3 (125839750_159124173) x4[0.1] | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | D | 8p23.1 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg18] 8p23.1 (8,139,051–12,619,015) x1 | |

| C (n = 5) | Fraser syndrome | 1 | NR | 9p22.3 | Splicing | de novo | het | NM_144966.7 (FREM1): c.5334 + 1G > A (r.spl?) |

| Microdeletion | 9p22.3 | Loss | Inherited | het | arr[hg18] 9p22.3 (14,871,409–14,938,830) x1 | |||

| Prader Willi | 1 | NR | 15q11 | Gain | de novo | het | arr[hg18]15q11.2q13.1 (20,319,702–26,143,385) x3 | |

| Microdeletion | 1 | NR | 17q12 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg19] 17q12 (34815551_36249430) x1 | |

| Congenital disorder of glycosylation | 1 | NR | Xp11.23 | Loss | de novo | het | NM_001042498 (SLC35A2): c.753delG, p.(Trp251fs) | |

| XY reversal | 1 | D | XY | ? | de novo | ? | –* | |

| D (n = 2) | Microdeletion | 1 | N | 15q26 | Loss | de novo | het | arr[hg18] chr15:80,689,404–82,938,351 x 1 and |

| 17p12 | het | arr[hg18] chr17:14049619–15497020 x1 | ||||||

| Microdeletion | 1 | D | 22q11.2 | Gain | ut | het | 47, XY, +der (22) t (11;22) (q23.3; q11.2) mat |

Genetic tests included karyotyping, SNP array or Whole exome sequencing. AR, Autosomal recessive; XLR, X-linked recessive; CH, compound heterozygote; n, number of patients; ut, unbalanced translocation.

Isolated CDH and Complex CDH

CDH may present as an isolated anomaly (isolated-CDH) or patients can have one or more additional anomalies (CDH-complex) (1, 31). Anomalies can be found in all body sites; cardiac anomalies, anomalies of the urogenital system, limb malformations, nervous system anomalies, orofacial clefts, and gastrointestinal anomalies including intestinal atresia (3, 32). Zaiss et al. described syndromic clinical features such as hypertelorism not assigned to a specific syndrome in 7.7% of studied patients (32). Pathogenic genetic alterations—both in complex and in isolated CDH—are associated with a worse prognosis (33). Moreover, de novo pathogenic alterations are seen more often in complex CDH (34–36). Phenotypical complex patients could be more likely to receive a genetic test. In our cohort, genetic test results were described for patients with associated anomalies (n = 207) and for patients without associated anomalies (n = 311). Thus, there was not a priory bias in this respect (p = 0.923). Twenty patients with associated anomalies had pathogenic genetic alterations vs. one with isolated CDH (P < 0.001). Main outcome parameters of the Erasmus MC-Sophia Children's Hospital, Rotterdam, the Netherlands CDH cohort are depicted in Tables 3, 4. Full cohort descriptions and analysis methods are described in Supplementary Tables S1, S2.

Table 3.

Cohort description of output measures and genetic evaluation.

| Group | Characteristic | Genetic test (n = 530) | No genetic test (n = 275) | Total (n) | P | Abnormal genetic test (n = 62) | No genetic test (n = 275) | No pathogenic changes (n = 468) | Total (n) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | 238a (44.9%) | 120a (43.6%) | 358 (44.5%) | 0.824 | 34a (54.8%) | 120a (43.6%) | 204a (43.6%) | 358 (44.5%) | 0.502 |

| M | 285a (53.8%) | 150a (54.5%) | 435 (54.0%) | 27a (43.5%) | 150a (54.5%) | 258a (55.1%) | 435 (54.0%) | |||

| O | 7a (1.3%) | 5a (1.8%) | 12 (1.5%) | 1a (1.6%) | 5a (1.8%) | 6a (1.3%) | 12 (1.5%) | |||

| Associated anomalies | CDH-C | 207a (39.1%) | 104a (37.8%) | 311 (38.6%) | 0.923 | 56a (90.3%) | 104b (37.8%) | 151b (32.3%) | 311 (38.6%) | 4.5658E-16 |

| CDH-I | 311a (58.7%) | 164a (59.6%) | 475 (59.0%) | 6a (9.7%) | 164b (59.6%) | 305b (65.2%) | 475 (59.0%) | |||

| CDH-MD | 12a (2.3%) | 7a (2.5%) | 19 (2.4%) | 0a (0.0%) | 7a (2.5%) | 12a (2.6%) | 19 (2.4%) | |||

| Location of defect | Bilateral | 4a (0.8%) | 6a (2.2%) | 10 (1.2%) | 0.005998 | 0a (0.0%) | 6a (2.2%) | 4a (0.9%) | 10 (1.2%) | 0.004092 |

| Eventration | 17a (3.2%) | 1b (0.4%) | 18 (2.2%) | 1a, b (1.6%) | 1b (0.4%) | 16a (3.4%) | 18 (2.2%) | |||

| Left | 415a (78.3%) | 199a (72.4%) | 614 (76.3%) | 48a (77.4%) | 199a (72.4%) | 367a (78.4%) | 614 (76.3%) | |||

| POE | 4a (0.8%) | 2a (0.7%) | 6 (0.7%) | 2a (3.2%) | 2a (0.7%) | 2a (0.4%) | 6 (0.7%) | |||

| Right | 73a (13.8%) | 58b (21.1%) | 131 (16.3%) | 7a, b (11.3%) | 58b (21.1%) | 66a (14.1%) | 131 (16.3%) | |||

| MD | 17a (3.2%) | 9a (3.3%) | 26 (3.2%) | 4a (6.5%) | 9a (3.3%) | 13a (2.8%) | 26 (3.2%) | |||

| Defect size | A | 97a (18.3%) | 19b (6.9%) | 116 (14.4%) | 1.3023E-41 | 10a, b (16.1%) | 19b (6.9%) | 87a (18.6%) | 116 (14.4%) | 1.3224E-44 |

| B | 50a (9.4%) | 2b (0.7%) | 52 (6.5%) | 4a (6.5%) | 2b (0.7%) | 46a (9.8%) | 52 (6.5%) | |||

| C | 157a (29.6%) | 12b (4.4%) | 169 (21.0%) | 5a (8.1%) | 12a (4.4%) | 152b (32.5%) | 169 (21.0%) | |||

| D | 32a (6.0%) | 0b (0.0%) | 32 (4.0%) | 2a (3.2%) | 0b (0.0%) | 30a (6.4%) | 32 (4.0%) | |||

| NR | 194a (36.6%) | 242b (88.0%) | 436 (54.2%) | 41a (66.1%) | 242b (88.0%) | 153c (32.7%) | 436 (54.2%) | |||

| Timing of test | MD-genetic test | – | – | – | – | 13a (21.0%) | 0b (21.0%) | 88a (18.8.0%) | 101 (12.5%) | 8.4554E-167 |

| MD-no genetic test | – | – | – | 0a (0.0%) | 127b (46.2%) | 0a (0.0%) | 127 (15.8%) | |||

| Postnatal-genetic test | – | – | – | 16a (25.8%) | 0b (0%) | 101a (21.6%) | 117 (14.5%) | |||

| Postnatal-no genetic test | – | – | – | 0a (0.0%) | 96b (34.9%) | 0a (0.0%) | 96 (11.9%) | |||

| Prenatal-genetic test | – | – | – | 33a (53.2%) | 0b (0%) | 279a (59.6%) | 312 (38.8%) | |||

| Prenatal-no genetic test | – | – | – | 0a (0.0%) | 52b (18.9%) | 0a (0.0%) | 52 (6.5%) |

In total, 530 out of 805 patients received a genetic test. Defect size (A–D) was described in 369 patients. Defect sizes are classified from A to D as described in the method section. A is the smallest defect size and D a (near) absence of the diaphragm. Within a column each characteristic that does not share a subscript letter (a−b) differs significantly from those with different subscript letters (a−b) whose column proportions do not differ significantly from each other at the 0.05 level. For instance, more patients with associated anomalies have an abnormal test and vice versa more patients with an isolated defect have no abnormal test (P < 0.001). Patients with defect size A stand apart from the other defect sizes in respect to the number of abnormal genetic tests, C in having no genetic test and having no pathogenic alteration (P < 0.001). There are differences in having no genetic test, having an abnormal test result and having a normal test result comparing post- and pre-natal subgroups (P < 0.001). Trisomy 13, 18, and 21 were evaluated in 530 patients and more than half of the patients received at least karyotyping or SNP-array. A full cohort description is available in Supplementary Table S1. Complete statistical comparison of patients with a genetic test is depicted in Supplementary Table S2. MD, Missing data; CDH-C, CDH patients with associated defects; CDH-I, CDH patients without other associated defects; CDH-MD, CDH patients in which no additional information was registered; POE, Paraoesophageal hernia; EV, Eventration; BL, Bilateral hernia; AGT, abnormal genetic test; NPC, no pathogenic changes.

Table 4.

Significant differences in output measures of patients with a genetic test.

| Group | Characteristic | Abnormal genetic test (n = 62) | No pathogenic changes (n = 468) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated anomalies | CDH-complex (n = 207) | 56a (27.1%) | 151a (72.9%) | 1,432E-14 |

| CDH-isolated (n = 311) | 6b (1.9%) | 305b (98.1%) | ||

| CDH-unknown (n = 12) | 0a,b (0.0%) | 12a,b (100.0%) | ||

| Defect size | A (n = 97) | 10a,b (10.3%) | 87a,b (89.7%) | 0.000006 |

| B (n = 50) | 4a,b (8.0%) | 46a,b (92.0%) | ||

| C (n = 157) | 5b (3.2%) | 152b (96.8%) | ||

| D (n = 32) | 2a,b (6.3%) | 30a,b (93.8%) | ||

| NR (n = 194) | 41a (21.1%) | 153a (78.9%) | ||

| Type of genetic test | Karyotyping | 297 (56.0%) | ||

| WES | 51 (9.6%) | |||

| Array | 362 (68.3%) | |||

| Trisomy 13, 18, 21* | 530 (100%) |

Significant differences when evaluating only patients with a genetic test. Trisomy 13, 18, and 21 were evaluated in 530 patients and more than half of the patients received at least karyotyping or SNP-array. An abnormal genetic test is seen more often in complex-CDH (P < 0.001) and defect size C differs from the missing data category (P < 0.001) as substantially more abnormal genetic tests are described in the later. Within a column each characteristic measure that does not share a subscript letter (a−b) differs significantly from those with different subscript letters (a−b) whose column proportions do not differ significantly from each other at the 0.05 level. WES, whole exome sequencing; MD, Missing data; CDH-C, CDH patients with associated defects; CDH-I, CDH patients without other associated defects; CDH-MD, CDH patients in which no additional information was registered; POE, Paraoesophageal hernia; EV, Eventration; BL, Bilateral hernia; AGT, abnormal genetic test; NPC, no pathogenic changes.

Comparing features of isolated CDH and complex CDH is difficult, depending on how accurately these two groups can be distinguished. Not all patients receive the same phenotypical evaluation and registration is sometimes incomplete. For instance, not all associated anatomical malformations are detectable with ultrasound. Nevertheless, increased resolution of prenatal ultrasound over time has improved the detection of associated anatomical malformations. Neurological symptoms could develop at later age and are not noticeable during the first months or years of development. Furthermore, not all symptoms observed during often organ specific evaluations of medical subspecialities. For instance, postnatal monitoring is essential to detect any associated neurological or ophthalmological symptoms. CDH registries would benefit from regular re-evaluation of these outcome measures. In short, there is a level of uncertainty in registries regarding which patients have no associated anomalies, have no associated anomalies detected, or have no associated anomalies registered.

Genetic Associations and Co-morbidity

Long-term complications in children born with CDH include chronic lung disease, feeding difficulties, gastro-esophageal reflux, growth failure, scoliosis, chest asymmetry, neurodevelopmental delay, and sensorineural hearing loss (37, 38). These co-morbidities can be either a direct or indirect consequence of the CDH or be a consequence of the treatment. Damaging de novo variations in both isolated CDH and complex CDH-complex have been found associated with pulmonary hypertension, higher mortality rate, and worse neurodevelopmental outcome (33). There is a large difference in survival rates between patients with or without persistent pulmonary hypertension (39) and bronchopulmonary sequestration (40). The genetic contribution to bronchopulmonary sequestration etiology is unknown. Mutations in BMPR2 (41, 42) and several SMAD signaling molecule genes have been associated with the development of pulmonary hypertension in adults and children (43–45). A striking association between TGF-β/SMAD signaling and pulmonary hypertension has been reported in CDH, as the CDH lungs had increased miR-200b expression and decreased TGF-β/SMAD signaling (46). Increasing miR-200b decreases the TGF-β signaling and reduces lung hypoplasia in a nitrofen induced congenital diaphragmatic hernia -pulmonary hypertension rat model (46). Similarly, Pereira-Terra and colleagues described a specific micro-RNA signature in tracheal aspirate fluid, upregulation of miR-200b and miR-10a and decreased TGFB signaling (47). Patients with mutations in genes from this pathway have connective tissue disorders (48). In patients and mice, several genetic factors have been associated to lung and cardiac abnormalities (2, 49–52). CDH has been found in patients with connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome (53), Loeys-Dietz Syndrome (54, 55) and arterial tortuosity syndrome (56). Patients with these connective tissue disorders are at increased risk of cardiovascular problems (57, 58) later in life. Abnormal retinoic acid signaling can result in a diaphragm defect (59). Patients with variants in STRA6 and RARB-receptors and deletions of RBP1 at chromosome 3q22 (60, 61) in the retinoic acid signaling pathway have ophthalmic symptoms (62, 63). Patients with CDH may have other eye defects as well (64, 65). These occurrences of direct genotype-phenotype correlations stress the importance of genetic diagnostic screening to inform parents and patients about possible co-morbidities.

CDH Is a Complex Genetic Disorder

CDH is a multifactorial disease but neither environmental nor genetic contributions have been fully characterized. Maternal morbidities during pregnancy such as pre-gestational hypertension (66) and pre-existent maternal obesity (67–69) are associated with an increased risk for development of CDH in the fetus. Several other environmental factors have been associated with an increased risk: antidepressant medication (70), antibacterial medication (71), exposure to fungicides (72), the immunosuppressant drug mycophenolate mofetil (73), methotrexate use (74), exposure to cadmium (75), pesticides (76), hairspray use (77), alcohol intake (69, 77–79), and smoking (75, 78, 80). However, to what extent these associations impact diaphragm development and the onset of CDH is not known. The mother's nutrient intake during pregnancy is associated as well (81, 82); reduced vitamin A intake during pregnancy has the strongest associations with CDH (83, 84). Vitamin A shortage can be detected postnatally (85). It is hard to determine whether environmental factors explain some of the non-genetic contributions on a population level or to what extent the environment interacts with the processes disturbed by genetic anomalies. Epigenetic differences acquired during the life span can be detected between monozygotic twin pairs (86–88). Evaluating these differences—and the resulting gene expression changes—is an interesting approach. There are methods to overcome cellular heterogeneity and if epigenetic changes are present in blood these can be compared between patient and sibling (89–91).

The exact heritability—the contribution of genetic factors—is difficult to determine, in light of the relatively low disease incidence, the high mortality limiting vertical transmission and the limited numbers of twin pregnancies (92, 93). Heritability can be estimated using twin studies. For CDH, the concordance rates in dizygotic and monozygotic twins are comparable. Fifty-three monozygotic twins have been described, of whom 12 were concordant for CDH (2, 92). In our cohort, 24 twin pairs (15 dizygotic, 8 monozygotic, and one same sex twin pair of whom no genetic material was available to determine zygosity) are described. One dizygotic and one monozygotic twin pair were concordant for CDH. To reduce the effect of technical noise in twin comparisons, we used different alignment techniques, variant callers and statistics (see Supplementary Table S3). Neither the larger CNVs (94) nor SNVs (see Supplementary Table S3) differed between these twin siblings. Differences in phenotype can also be the result of twin-to-twin perfusion differences. Furthermore, single nucleotide changes could be located outside the coding sequence or at very low frequency, and then could not be detected with exome sequencing.

Somatic mosaicism is difficult to determine when the affected tissue or cells are missing. The mutated diaphragmatic cells might not have survived in sufficient quantities and, therefore, be undetectable with sequencing technologies (95). In line with this, whole genome sequencing did not find causative somatic variants in diaphragm biopsies (96, 97). In contrast, germline de novo variants are often present (33, 96–98). Females have a higher burden of de novo variants (98), suggesting a female protective model. Large cohort descriptions about sibling recurrence rate (92) or familial CDH are not available. In our cohort, only a few familial cases are known (<1%). Still, CDH is described to segregate through families (1) and/or present as a monogenetic disorder following autosomal dominant (53, 98–109), autosomal recessive (62, 110), or X-linked (111–113) inheritance patterns.

Depending on the specific family the monogenetic disorder has CDH is either a common or a less prevalent feature. More than 100 (candidate) genes have been described, mostly identified from animal models or monogenetic syndromes (2, 19). Monogenetic syndromes often have distinct phenotypical features and have been reviewed by Longoni et al. and Yu et al. (20, 114). Monogenetic syndromes in which CDH is a frequent feature are, for instance, autosomal recessive Donnai Barrow syndrome (OMIM: #22248, LRP2 gene), syndromic microphthalmia (#601186, #615524, STRA6, RARB), and autosomal dominant cardiac-urogenital syndrome (#3618280, MYRF gene). Associated phenotypes in these syndromes are congenital heart defects, sensorineural hearing loss, microphthalmia, genitourinary malformations, craniosynostosis and myopia with each of these syndromes its distinct features. Detailed phenotyping might be crucial in diagnosing clusters of CDH patients: either “phenotype first” and searching for an overlapping gene or “genotype first” and searching if patients with the same affected gene have an overlapping phenotype. Interestingly, Fryns syndrome and also Pentalogy of Cantrell have CDH as a defining feature; yet the gene or genes responsible for these conditions are not yet known.

CNV studies reported overlapping deletions and duplications, such as duplications of 11q23-qter (115), 16p11.2p duplications (15, 18), 17q12 deletions (15, 18, 116, 117), and 5p15.2 deletions (15). By prioritizing and sequencing the genes within these CNVs in other patients, new disease genes have been discovered. For example, in the 8p23.1 deletions (118–120), GATA4 (50) and SOX7 (121) and in case of 8q23.1 deletions (18), ZFPM2 (122) are the genes likely contributing to CDH. 15q26 deletions (120, 123) and subsequent sequencing implicate NR2F2 as a disease gene (124). For 1q41–1q42 deletions, one duplication disrupting the HLX gene and subsequent HLX gene variants have been described (15, 18, 125–128). Constraint coding regions are enriched for de novo variants (104), and using variant evaluation guidelines of rare de novo changes in these types of constraint genes (129) result in a likely pathogenic or pathogenic classification, especially if variants result in reduced amounts of protein.

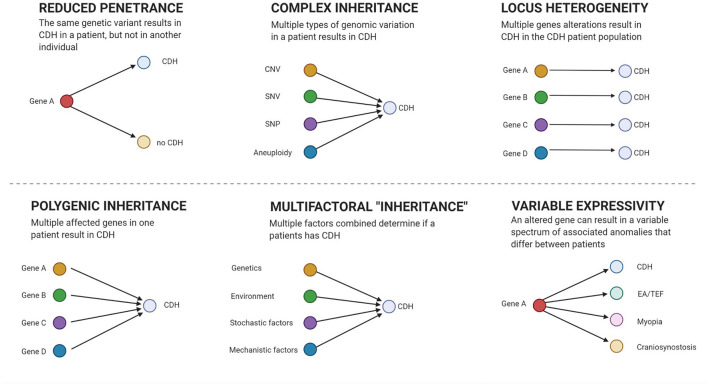

Interpretation of genetic results can be hindered by reduced penetrance (18, 122) and variable expressivity (2) that may mask the causal culprit in segregation analysis (see Figure 1). Polygenic inheritance (51), locus heterogeneity (33, 34, 130), and contributions of different kinds of genetic variation (17, 114) mask culprits from innocent bystanders. Therefore, large patient and control samples sizes are required to have enough power to classify variants into “benign,” “causal,” or “contributing.”

Figure 1.

Genetic models. Figure created with BioRender.com.

From Pathogenic Alteration to CDH

Finding a genetic variant predicted to be deleterious is only the first step in proving the functional effect of this DNA alteration. This is especially true for missense changes, in-frame insertion-deletions and copy number variations. Often there is only in-silico evidence regarding the impact of a variant on gene function and the way in which the disturbed gene function affects a biological pathway or mechanism. What is lacking is proof how a specific deleterious variant lead to defective diaphragm formation. Unfortunately, for most likely pathogenic CNVs and SNVs, the assumed functional consequence is based on the genetic alteration itself: i.e., copy number loss or nonsense variant is assumed to result in reduced amounts of mRNA expression and protein. Deleterious de novo missense variants and in-frame insertion-deletions in conserved coding regions are more difficult to relate to a likely functional consequence and is often on in-silico surveys. Improving the in-vitro evaluation of candidate variants is crucial in distinguishing causal variants from non-causal variants. These experiments require tremendous effort and can be complicated by the presence of more than one candidate alteration.

Detecting a deleterious variant in a gene in multiple patients helps prioritizing candidate genes for function evaluation and studies using animal models. In a large cohort (n = 827), seven syndromic and four recurrent CNVs were identified (104). Some of these have already been associated with CDH; e.g., 17q12 deletions, 16p13.1 duplications, 22q11 deletions, and 21q22 duplications. Furthermore, 87 CNVs were de novo, of which 54 were large (>2 Mb) deletions (104). Although non-recurrent, at least a proportion of these large de novo deletions are likely to be related to the patient's phenotype. Ten genes were enriched for de novo variants, of which mitochondrial lon peptidase 1 (LONP1) and Aly/REF export factor (ALYREF) were the most promising candidate disease genes. LONP1, MYRF as well as ZFPM2 reached or approached genome wide significance when a variant burden test was performed for all deleterious changes (i.e., including inherited variants) (104). Combining multiple “omics” and in-vitro translational approaches can potentially bridge the gap between genetic findings and animal models.

In animal models, fewer progenitors reaching the PPF at the proper developmental due to decreased proliferation, increased apoptosis, migration defects or failure to differentiate in their proper cell fates have been proposed as causes for CDH (131–134). Disturbances in specific processes such as retinoic acid signaling or muscle connective tissue formation were initially discovered in animal experiments; genes associated with these pathways or processes were subsequently found altered in patients (132, 135–138). Additionally, disturbed processes can be identified using gene enrichment strategies to find common denominators in the affected genes and loci. Longoni and colleagues described the enrichment of rare, likely deleterious variants in CDH patients of genes derived from mouse PPF embryonic transcriptomes (139), known human disease genes, their protein interaction partners and candidate genes from CNV hotspots (35). Often, these alterations were inherited and implicate non-Mendelian inheritance patterns. On the individual level, these changes can be regarded as risk factors. Combined, these changes may affect a biological pathway to such an extent that they result in CDH. Assigning such a pathway or process—for instance how these gene variants disturb myoblast progenitor cell proliferation or migration—is not easy. Animal models are not perfect, although they provide evidence of involvement of a gene when it is knocked-out and in which cases the animals develop CDH at a certain frequency. However, this procedure hardly ever takes into account that genetic variation is mostly not a complete loss-of-function of a gene. Missense variants, copy number gains and heterozygous changes could—and likely do—differ in impact or mechanism of action. Thus, in these cases, knock-out models either over- or underestimate the effect of a genetic variant.

In some cases, specific variants can be associated with the causative mechanism; e.g., the association of FBN1 variants in Marfan syndrome (53) and defects in the connective tissue. Indeed, our cohort included patients with FBN1 and TGFB3 alterations. In other patients, the affected pathway is known; e.g., patients with deletions of NR2F2 (123) have a defect in a gene that codes for a receptor that is activated by retinoic acid signaling (140). Of other genes, we know that they interact with other disease genes, are expressed in the developing diaphragm and are also associated with retinoic acid signaling (e.g., ZFPM2, GATA4). A small difference in spatial and temporal binding and organ-specific combination of transcription factors have been suggested as links between the different syndromes with CDH (141). Most of the deleterious CNVs and aneuploidies are assumed pathogenic and the most likely cause of the diaphragm defect. However, how these—often continuous gene deletions—in patients impact diaphragm formation and subsequently result in CDH remains unclear.

Temporal Screening Bias

Technologies have a different resolution to detect genomic changes ranging from chromosome arms, several mega-bases to single nucleotide level. Initially, patients were evaluated with karyotyping, MLPA and QF-PCR, with which only aneuploidies or chromosome (band) level changes could be detected. At the Erasmus MC-Sophia Children's Hospital, SNP-array was introduced in 2010 and is standard practice in case of ultrasound abnormalities since 2012. The use of SNP arrays increased the detection resolution to gains and losses of several from mb to kilobases. Many patients in our cohort have retrospectively been re-evaluated with SNP-array. In 10.9% of patients a pathogenic change was. Similarly, 10.4% of patients registered in the EUROCAT registry (1980–2009) have a chromosomal anomaly, genetic syndrome or microdeletion (3). This was before the NGS era, and the findings mostly represent the larger genetic changes with a large phenotypic effect. Whole exome sequencing was introduced in our clinic more recently (2015), and initially only used to evaluate the more complex patients. Restoring the temporal screening bias by screening large historical cohorts of patients and subsequent evaluating potential associations between genetic factors and long-term morbidity can benefit the future and today's patients and parents.

Collaboration Is Key

Combining disease cohorts revealed that damaging de novo alterations are associated with the more severe and complex phenotypes (33, 130). This strategy was pivotal in identifying disease genes (98, 104, 130, 142). The success of this effort stresses the importance of collaborations such as the DHREAMS consortium (http://www.cdhgenetics.com). Trio whole genome-based approaches are recommended, as these enable to simultaneously determine different types of genetic variation. Additionally, this technique is suited for continuous re-analysis. By combining and sequencing these cohorts, the CDH-EURO consortium (143) and Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group (144) can add to endeavors of the DHREAMS consortium. This will enable to identify genes that are more often affected in patients than by chance alone, and will allow manageable numbers of required functional tests and animal models. For collaborations to work, samples need to be stored in well-managed biobanks and data should be meticulously archived for later re-analysis or re-evaluation. New challenges for these biobanks and data archiving and sharing are privacy regulations (145). Sharing of patient material and data should consider the privacy of participants and their families but also acknowledge the efforts of stakeholders such as researchers and clinicians (146). An ethical and legal balance should be sought weighing the privacy needs of individual patients against the medical benefits of the patient population.

Conclusions

Diagnostic yields of up to 37% using next generation sequencing have been proposed. These yields are reached when, in addition to genes from known monogenetic syndromes, heterozygous de novo variants in genes expressed at the proper time-point in relevant tissue in animal models are classified as likely pathogenic (105). Importantly, heritability and diagnostic yield are calculated on a population level. From a patient's or parents' perspective it matters the most to know (1) if they themselves or their children have or do not have genetic changes in their genome explaining the CDH, (2) if subsequent children or patients' offspring are at risk of CDH, and (3) what the consequences of these changes are for the prognosis and/or the probability of complications. CDH is now mostly detected prenatally; consequently, fast, accurate, and predictive genetic diagnostics are increasingly needed. As about a third of patients have a de novo variant in the coding region (104). For parents to make informed choices, it is vital to knowing if a genetic variant detected in their child is causal or benign, and what the predicted consequences are of this variant.

Author Contributions

EB, AdK, and DT: conceptualization and funding acquisition. RB and WvI: methodology and software. EB: validation, visualization, and project administration. KvW, SO, EB, and RB: formal analysis. EB and RB: investigation. AE, DT, and RW: resources. EB, RB, NP, and DV: data curation. EB and KvW: writing—original draft preparation. NP, AdK, MvD, SO, RW, AE, DT, RR, CB, HR, DV, WvI, FS, HB, RB, and JS: writing—review and editing. AdK and EB: supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Sophia Foundation for Scientific Research [Grant Numbers 493 (DT and AdK) and S13-09 (DT, AdK, and EB)].

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and parents who participated in this study. We thank Ko Hagoort for critical reading of the manuscript, text editing and editorial advice.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2021.800915/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. (2007) 145c:158–71. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kardon G, Ackerman KG, McCulley DJ, Shen Y, Wynn J, Shang L, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernias: from genes to mechanisms to therapies. Dis Models Mech. (2017) 10:955–70. 10.1242/dmm.028365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGivern MR, Best KE, Rankin J, Wellesley D, Greenlees R, Addor MC, et al. Epidemiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Europe: a register-based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2015) 100:F137–44. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grandjean H, Larroque D, Levi S. The performance of routine ultrasonographic screening of pregnancies in the Eurofetus Study. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. (1999) 181:446–54. 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70577-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham G, Devine PC. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. (2005) 29:69–76. 10.1053/j.semperi.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garne E, Haeusler M, Barisic I, Gjergja R, Stoll C, Clementi M. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: evaluation of prenatal diagnosis in 20 European regions. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. (2002) 19:329–33. 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00635.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgos CM, Frenckner B, Luco M, Harting MT, Lally PA, Lally KP. Prenatally versus postnatally diagnosed congenital diaphragmatic hernia - side, stage, and outcome. J Pediatric Surg. (2019) 54:651–5. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta VS, Harting MT, Lally PA, Miller CC, Hirschl RB, Davis CF, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia study, mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter registry study of over 5000 patients over 25 years. Ann Surg. (2021). 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005113. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global PaedSurg Research C . Mortality from gastrointestinal congenital anomalies at 264 hospitals in 74 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: a multicentre, international, prospective cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 398:325–39. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00767-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleal L, McHaffie SL, Lee M, Hastie N, Martínez-Estrada OM, Chau YY. Resolving the heterogeneity of diaphragmatic mesenchyme: a novel mouse model of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Dis Models Mech. (2021) 14:dmm046797. 10.1242/dmm.046797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmona R, Cañete A, Cano E, Ariza L, Rojas A, Muñoz-Chápuli R. Conditional deletion of WT1 in the septum transversum mesenchyme causes congenital diaphragmatic hernia in mice. Elife. (2016) 5:e16009. 10.7554/eLife.16009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sefton EM, Gallardo M, Kardon G. Developmental origin and morphogenesis of the diaphragm, an essential mammalian muscle. Dev Biol. (2018) 440:64–73. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sefton EM, Kardon G. Connecting muscle development, birth defects, and evolution: an essential role for muscle connective tissue. Curr Top Dev Biol. (2019) 132:137–76. 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edel GG, Schaaf G, Wijnen RMH, Tibboel D, Kardon G, Rottier RJ. Cellular origin(s) of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Front Pediatrics. (2021) 9:804496. 10.3389/fped.2021.804496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Q, High FA, Zhang C, Cerveira E, Russell MK, Longoni M, et al. Systematic analysis of copy number variation associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:5247–52. 10.1073/pnas.1714885115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott DA, Klaassens M, Holder AM, Lally KP, Fernandes CJ, Galjaard RJ, et al. Genome-wide oligonucleotide-based array comparative genome hybridization analysis of non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Human Mol Genet. (2007) 16:424–30. 10.1093/hmg/ddl475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu L, Wynn J, Ma L, Guha S, Mychaliska GB, Crombleholme TM, et al. De novo copy number variants are associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Med Genet. (2012) 49:650–9. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wat MJ, Veenma D, Hogue J, Holder AM, Yu Z, Wat JJ, et al. Genomic alterations that contribute to the development of isolated and non-isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Med Genet. (2011) 48:299–307. 10.1136/jmg.2011.089680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holder AM, Klaassens M, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Lee B, Scott DA. Genetic factors in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Hum Genet. (2007) 80:825–45. 10.1086/513442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longoni M, Pober BR, High FA. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews(®).Seattle, WA: University of Washington; Copyright © 1993-2020. Seattle, WA: University of Washington. GeneReviews Is a Registered Trademark of the University of Washington, Seattle (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study G, Morini F, Valfrè L, Capolupo I, Lally KP, Lally PA, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: defect size correlates with developmental defect. J Pediatric Surg. (2013) 48:1177–82. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kilian AK, Büsing KA, Schuetz EM, Schaible T, Neff KW. Fetal MR lung volumetry in congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH): prediction of clinical outcome and the need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Klinische Padiatrie. (2009) 221:295–301. 10.1055/s-0029-1192022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metkus AP, Filly RA, Stringer MD, Harrison MR, Adzick NS. Sonographic predictors of survival in fetal diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatric Surg. (1996) 31:148–51; discussion: 151–2. 10.1016/S0022-3468(96)90338-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cordier AG, Jani JC, Cannie MM, Rodó C, Fabietti I, Persico N, et al. Stomach position in prediction of survival in left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia with or without fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion. Ultrasound Obstetr Gynecol. (2015) 46:155–61. 10.1002/uog.14759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basta AM, Lusk LA, Keller RL, Filly RA. Fetal stomach position predicts neonatal outcomes in isolated left-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Fetal Diagnosis Ther. (2016) 39:248–55. 10.1159/000440649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deprest JA, Flemmer AW, Gratacos E, Nicolaides K. Antenatal prediction of lung volume and in-utero treatment by fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion in severe isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2009) 14:8–13. 10.1016/j.siny.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snoek KG, Peters NCJ, van Rosmalen J, van Heijst AFJ, Eggink AJ, Sikkel E, et al. The validity of the observed-to-expected lung-to-head ratio in congenital diaphragmatic hernia in an era of standardized neonatal treatment; a multicenter study. Prenatal Diagnosis. (2017) 37:658–65. 10.1002/pd.5062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson DM, Gupta VS, Lally PA, Luco M, Tsao K, Lally KP, et al. Postnatal pulmonary hypertension severity predicts inpatient outcomes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Neonatology. (2021) 118:147–54. 10.1159/000512966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brindle ME, Cook EF, Tibboel D, Lally PA, Lally KP. A clinical prediction rule for the severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernias in newborns. Pediatrics. (2014) 134:e413–9. 10.1542/peds.2013-3367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu L, Sawle AD, Wynn J, Aspelund G, Stolar CJ, Arkovitz MS, et al. Increased burden of de novo predicted deleterious variants in complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Human Mol Genet. (2015) 24:4764–73. 10.1093/hmg/ddv196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cochius-den Otter SCM, Erdem Ö, van Rosmalen J, Schaible T, Peters NCJ, Cohen-Overbeek TE, et al. Validation of a prediction rule for mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20192379. 10.1542/peds.2019-2379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, Roth MP. Associated malformations in cases with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Genet Couns. (2008) 19:331–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaiss I, Kehl S, Link K, Neff W, Schaible T, Sütterlin M, et al. Associated malformations in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Perinatol. (2011) 28:211–8. 10.1055/s-0030-1268235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qiao L, Wynn J, Yu L, Hernan R, Zhou X, Duron V, et al. Likely damaging de novo variants in congenital diaphragmatic hernia patients are associated with worse clinical outcomes. Genet Med. (2020) 22:2020–8. 10.1038/s41436-020-0908-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longoni M, High FA, Russell MK, Kashani A, Tracy AA, Coletti CM, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia revealed by exome sequencing, developmental data, and bioinformatics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2014) 111:12450–5. 10.1073/pnas.1412509111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bendixen C, Reutter H. The role of de novo variants in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Genes. (2021) 12:1405. 10.3390/genes12091405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amoils M, Crisham Janik M, Lustig LR. Patterns and predictors of sensorineural hearing loss in children with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. JAMA Otolaryngol. (2015) 141:923–6. 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masumoto K, Nagata K, Uesugi T, Yamada T, Taguchi T. Risk factors for sensorineural hearing loss in survivors with severe congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Euro J Pediatr. (2007) 166:607–12. 10.1007/s00431-006-0300-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coughlin MA, Werner NL, Gajarski R, Gadepalli S, Hirschl R, Barks J, et al. Prenatally diagnosed severe CDH: mortality and morbidity remain high. J Pediatric Surg. (2016) 51:1091–5. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coughlin MA, Gupta VS, Ebanks AH, Harting MT, Lally KP. Incidence and outcomes of patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and pulmonary sequestration. J Pediatric Surg. (2021) 56:1126–9. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane KB, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Thomson JR, Phillips JA, 3rd, Loyd JE, et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension. Nat Genet. (2000) 26:81–4. 10.1038/79226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomson JR, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Morgan NV, Humbert M, Elliott GC, et al. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-β family. J Med Genet. (2000) 37:741–5. 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nasim MT, Ogo T, Ahmed M, Randall R, Chowdhury HM, Snape KM, et al. Molecular genetic characterization of SMAD signaling molecules in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Human Mutation. (2011) 32:1385–9. 10.1002/humu.21605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shintani M, Yagi H, Nakayama T, Saji T, Matsuoka R. A new nonsense mutation of SMAD8 associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Med Genet. (2009) 46:331–7. 10.1136/jmg.2008.062703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu N, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Welch CL, Ma L, Qi H, King AK, et al. Exome sequencing in children with pulmonary arterial hypertension demonstrates differences compared with adults. Circul Genomic Precision Med. (2018) 11:e001887. 10.1161/CIRCGEN.117.001887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khoshgoo N, Kholdebarin R, Pereira-Terra P, Mahood TH, Falk L, Day CA, et al. Prenatal microRNA miR-200b therapy improves nitrofen-induced pulmonary hypoplasia associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Surg. (2019) 269:979–87. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pereira-Terra P, Deprest JA, Kholdebarin R, Khoshgoo N, DeKoninck P, Munck AA, et al. Unique tracheal fluid microrna signature predicts response to FETO in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Ann Surg. (2015) 262:1130–40. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacFarlane EG, Haupt J, Dietz HC, Shore EM. TGF-β family signaling in connective tissue and skeletal diseases. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. (2017) 9:a022269. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jay PY, Bielinska M, Erlich JM, Mannisto S, Pu WT, Heikinheimo M, et al. Impaired mesenchymal cell function in Gata4 mutant mice leads to diaphragmatic hernias and primary lung defects. Dev Biol. (2007) 301:602–14. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu L, Wynn J, Cheung YH, Shen Y, Mychaliska GB, Crombleholme TM, et al. Variants in GATA4 are a rare cause of familial and sporadic congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Human Genet. (2013) 132:285–92. 10.1007/s00439-012-1249-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Donahoe PK, Longoni M, High FA. Polygenic causes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia produce common lung pathologies. Am J Pathol. (2016) 186:2532–43. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brady PD, Van Houdt J, Callewaert B, Deprest J, Devriendt K, Vermeesch JR. Exome sequencing identifies ZFPM2 as a cause of familial isolated congenital diaphragmatic hernia and possibly cardiovascular malformations. Euro J Med Genet. (2014) 57:247–52. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beck TF, Campeau PM, Jhangiani SN, Gambin T, Li AH, Abo-Zahrah R, et al. FBN1 contributing to familial congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. (2015) 167a:831–6. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lobaton GO, Chen YJ, Jelin E, Garcia AV. Unusual case of delayed congenital diaphragmatic hernia in Loeys-Dietz syndrome: a case report. J Surg Case Rep. (2021) 2021:rjaa604. 10.1093/jscr/rjaa604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marsili L, Overwater E, Hanna N, Baujat G, Baars MJH, Boileau C, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of TGFB3 disease-causing variants in a Dutch-French cohort and first report of a homozygous patient. Clin Genet. (2020) 97:723–30. 10.1111/cge.13700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaidi SH, Meyer S, Peltekova I, Teebi AS, Faiyaz-Ul-Haque M. Congenital diaphragmatic abnormalities in arterial tortuosity syndrome patients who carry mutations in the SLC2A10 gene. Clin Genet. (2009) 75:588–9. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacCarrick G, Black JH, Bowdin S, El-Hamamsy I, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Guerrerio AL, et al. Loeys–Dietz syndrome: a primer for diagnosis and management. Genet Med. (2014) 16:576–87. 10.1038/gim.2014.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yetman AT, Bornemeier RA, McCrindle BW. Long-term outcome in patients with Marfan syndrome: is aortic dissection the only cause of sudden death? J Am Coll Cardiol. (2003) 41:329–32. 10.1016/S0735-1097(02)02699-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Clugston RD, Zhang W, Alvarez S, de Lera AR, Greer JJ. Understanding abnormal retinoid signaling as a causative mechanism in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (2010) 42:276–85. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0076OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dillon E, Renwick M, Wright C. Congenital diaphragmatic herniation: antenatal detection and outcome. Br J Radiol. (2000) 73:360–5. 10.1259/bjr.73.868.10844860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wolstenholme J, Brown J, Masters KG, Wright C, English CJ. Blepharophimosis sequence and diaphragmatic hernia associated with interstitial deletion of chromosome 3 (46,XY,del(3)(q21q23)). J Med Genet. (1994) 31:647–8. 10.1136/jmg.31.8.647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Srour M, Chitayat D, Caron V, Chassaing N, Bitoun P, Patry L, et al. Recessive and dominant mutations in retinoic acid receptor beta in cases with microphthalmia and diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Hum Genet. (2013) 93:765–72. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pasutto F, Sticht H, Hammersen G, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Fitzpatrick DR, Nürnberg G, et al. Mutations in STRA6 cause a broad spectrum of malformations including anophthalmia, congenital heart defects, diaphragmatic hernia, alveolar capillary dysplasia, lung hypoplasia, mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. (2007) 80:550–60. 10.1086/512203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kantarci S, Al-Gazali L, Hill RS, Donnai D, Black GC, Bieth E, et al. Mutations in LRP2, which encodes the multiligand receptor megalin, cause Donnai-Barrow and facio-oculo-acoustico-renal syndromes. Nat Genet. (2007) 39:957–9. 10.1038/ng2063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kammoun M, Brady P, De Catte L, Deprest J, Devriendt K, Vermeesch JR. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia as a part of Nance-Horan syndrome? Euro J Human Genet. (2018) 26:359–66. 10.1038/s41431-017-0032-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mesas Burgos C, Ehrén H, Conner P, Frenckner B. Maternal risk factors and perinatal characteristics in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a nationwide population-based study. Fetal Diagnosis Ther. (2019) 46:385–91. 10.1159/000497619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Blomberg MI, Källén B. Maternal obesity and morbid obesity: the risk for birth defects in the offspring. Birth Defects Res. (2010) 88:35–40. 10.1002/bdra.20620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Waller DK, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, Hobbs CA, Canfield MA, Siega-Riz AM, et al. Prepregnancy obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med. (2007) 161:745–50. 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McAteer JP, Hecht A, De Roos AJ, Goldin AB. Maternal medical and behavioral risk factors for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatric Surg. (2014) 49:34–8; discussion: 38. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson KN, Lind JN, Simeone RM, Bobo WV, Mitchell AA, Riehle-Colarusso T, et al. Maternal use of specific antidepressant medications during early pregnancy and the risk of selected birth defects. JAMA Psychiatry. (2020) 77:1246–55. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crider KS, Cleves MA, Reefhuis J, Berry RJ, Hobbs CA, Hu DJ. Antibacterial medication use during pregnancy and risk of birth defects: National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med. (2009) 163:978–85. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carter TC, Druschel CM, Romitti PA, Bell EM, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Antifungal drugs and the risk of selected birth defects. Am J Obstetr Gynecol. (2008) 198:191.e1–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Perez-Aytes A, Marin-Reina P, Boso V, Ledo A, Carey JC, Vento M. Mycophenolate mofetil embryopathy: a newly recognized teratogenic syndrome. Euro J Med Genet. (2017) 60:16–21. 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dawson AL, Riehle-Colarusso T, Reefhuis J, Arena JF. Maternal exposure to methotrexate and birth defects: a population-based study. Am J Med Genet A. (2014) 164a:2212–6. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramakrishnan R, Stuart AL, Salemi JL, Chen H, O'Rourke K, Kirby RS. Maternal exposure to ambient cadmium levels, maternal smoking during pregnancy, and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Birth Defects Res. (2019) 111:1399–407. 10.1002/bdr2.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carmichael SL, Yang W, Roberts E, Kegley SE, Brown TJ, English PB, et al. Residential agricultural pesticide exposures and risks of selected birth defects among offspring in the San Joaquin Valley of California. Birth Defects Res. (2016) 106:27–35. 10.1002/bdra.23459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schulz F, Jenetzky E, Zwink N, Bendixen C, Kipfmueller F, Rafat N, et al. Parental risk factors for congenital diaphragmatic hernia - a large German case-control study. BMC Pediatr. (2021) 21:278. 10.1186/s12887-021-02748-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Balayla J, Abenhaim HA. Incidence, predictors and outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a population-based study of 32 million births in the United States. J Maternal Fetal Neonatal Med. (2014) 27:1438–44. 10.3109/14767058.2013.858691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Felix JF, van Dooren MF, Klaassens M, Hop WC, Torfs CP, Tibboel D. Environmental factors in the etiology of esophageal atresia and congenital diaphragmatic hernia: results of a case-control study. Birth Defects Res. (2008) 82:98–105. 10.1002/bdra.20423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Caspers KM, Oltean C, Romitti PA, Sun L, Pober BR, Rasmussen SA, et al. Maternal periconceptional exposure to cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption and congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Birth Defects Res. (2010) 88:1040–9. 10.1002/bdra.20716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang W, Shaw GM, Carmichael SL, Rasmussen SA, Waller DK, Pober BR, et al. Nutrient intakes in women and congenital diaphragmatic hernia in their offspring. Birth Defects Res. (2008) 82:131–8. 10.1002/bdra.20436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Carmichael SL, Ma C, Witte JS, Yang W, Rasmussen SA, Brunelli L, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia and maternal dietary nutrient pathways and diet quality. Birth Defects Res. (2020) 112:1475–83. 10.1002/bdr2.1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Beurskens LW, Schrijver LH, Tibboel D, Wildhagen MF, Knapen MF, Lindemans J, et al. Dietary vitamin A intake below the recommended daily intake during pregnancy and the risk of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the offspring. Birth Defects Res. (2013) 97:60–6. 10.1002/bdra.23093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Michikawa T, Yamazaki S, Sekiyama M, Kuroda T, Nakayama SF, Isobe T, et al. Maternal dietary intake of vitamin A during pregnancy was inversely associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: the Japan Environment and Children's Study. Br J Nutr. (2019) 122:1295–302. 10.1017/S0007114519002204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Beurskens LW, Tibboel D, Lindemans J, Duvekot JJ, Cohen-Overbeek TE, Veenma DC, et al. Retinol status of newborn infants is associated with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. (2010) 126:712–20. 10.1542/peds.2010-0521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fraga MF, Ballestar E, Paz MF, Ropero S, Setien F, Ballestar ML, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2005) 102:10604–9. 10.1073/pnas.0500398102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Malki K, Koritskaya E, Harris F, Bryson K, Herbster M, Tosto MG. Epigenetic differences in monozygotic twins discordant for major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e839. 10.1038/tp.2016.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Castillo-Fernandez JE, Spector TD, Bell JT. Epigenetics of discordant monozygotic twins: implications for disease. Genome Med. (2014) 6:60. 10.1186/s13073-014-0060-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jaffe AE, Irizarry RA. Accounting for cellular heterogeneity is critical in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biol. (2014) 15:R31. 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gervin K, Salas LA, Bakulski KM, van Zelm MC, Koestler DC, Wiencke JK, et al. Systematic evaluation and validation of reference and library selection methods for deconvolution of cord blood DNA methylation data. Clin Epigenet. (2019) 11:125. 10.1186/s13148-019-0717-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rahmani E, Schweiger R, Rhead B, Criswell LA, Barcellos LF, Eskin E, et al. Cell-type-specific resolution epigenetics without the need for cell sorting or single-cell biology. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:3417. 10.1038/s41467-019-11052-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pober BR, Lin A, Russell M, Ackerman KG, Chakravorty S, Strauss B, et al. Infants with Bochdalek diaphragmatic hernia: sibling precurrence and monozygotic twin discordance in a hospital-based malformation surveillance program. Am J Med Genet. (2005) 138A:81–8. 10.1002/ajmg.a.30904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang W, Pan W, Chen J, Xie W, Liu M, Wang J. Outcomes of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in one of the twins. Am J Perinatol. (2019) 36:1304–9. 10.1055/s-0038-1676830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Veenma D, Brosens E, de Jong E, van de Ven C, Meeussen C, Cohen-Overbeek T, et al. Copy number detection in discordant monozygotic twins of Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH) and Esophageal Atresia (EA) cohorts. Euro J Human Genet. (2012) 20:298–304. 10.1038/ejhg.2011.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.MacKenzie KC, Garritsen R, Chauhan RK, Sribudiani Y, de Graaf BM, Rugenbrink T, et al. The somatic mutation paradigm in congenital malformations: hirschsprung disease as a model. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:12354. 10.3390/ijms222212354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Matsunami N, Shanmugam H, Baird L, Stevens J, Byrne JL, Barnhart DC, et al. Germline but not somatic de novo mutations are common in human congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Birth Defects Res. (2018) 110:610–7. 10.1002/bdr2.1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bogenschutz EL, Fox ZD, Farrell A, Wynn J, Moore B, Yu L, et al. Deep whole-genome sequencing of multiple proband tissues and parental blood reveals the complex genetic etiology of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. HGG Adv. (2020) 1:100008. 10.1101/2020.04.03.024398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qi H, Yu L, Zhou X, Wynn J, Zhao H, Guo Y, et al. De novo variants in congenital diaphragmatic hernia identify MYRF as a new syndrome and reveal genetic overlaps with other developmental disorders. PLoS Genet. (2018) 14:e1007822. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Devriendt K, Deloof E, Moerman P, Legius E, Vanhole C, de Zegher F, et al. Diaphragmatic hernia in Denys-Drash syndrome. Am J Med Genet. (1995) 57:97–101. 10.1002/ajmg.1320570120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Antonius T, van Bon B, Eggink A, van der Burgt I, Noordam K, van Heijst A. Denys-Drash syndrome and congenital diaphragmatic hernia: another case with the 1097G > A(Arg366His) mutation. Am J Med Genet A. (2008) 146a:496–9. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Suri M, Kelehan P, O'Neill D, Vadeyar S, Grant J, Ahmed SF, et al. WT1 mutations in Meacham syndrome suggest a coelomic mesothelial origin of the cardiac and diaphragmatic malformations. Am J Med Genet. (2007) 143a:2312–20. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Denamur E, Bocquet N, Baudouin V, Da Silva F, Veitia R, Peuchmaur M, et al. WT1 splice-site mutations are rarely associated with primary steroid-resistant focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. (2000) 57:1868–72. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00036.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schwab ME, Dong S, Lianoglou BR, Aguilar Lucero AF, Schwartz GB, Norton ME, et al. Exome sequencing of fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernia supports a causal role for NR2F2, PTPN11, WT1 variants. Am J Surg. (2021). 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Qiao L, Xu L, Yu L, Wynn J, Hernan R, Zhou X, et al. Rare and de novo variants in 827 congenital diaphragmatic hernia probands implicate LONP1 as candidate risk gene. Am J Hum Genet. (2021) 108:1964–80. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Scott TM, Campbell IM, Hernandez-Garcia A, Lalani SR, Liu P, Shaw CA, et al. Clinical exome sequencing data reveal high diagnostic yields for congenital diaphragmatic hernia plus (CDH+) and new phenotypic expansions involving CDH. J Med Genet. (2021). 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107317. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jacobs AM, Toudjarska I, Racine A, Tsipouras P, Kilpatrick MW, Shanske A. A recurring FBN1 gene mutation in neonatal Marfan syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2002) 156:1081–5. 10.1001/archpedi.156.11.1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Revencu N, Quenum G, Detaille T, Verellen G, De Paepe A, Verellen-Dumoulin C. Congenital diaphragmatic eventration and bilateral uretero-hydronephrosis in a patient with neonatal Marfan syndrome caused by a mutation in exon 25 of the FBN1 gene and review of the literature. Euro J Pediatr. (2004) 163:33–7. 10.1007/s00431-003-1330-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Stheneur C, Faivre L, Collod-Béroud G, Gautier E, Binquet C, Bonithon-Kopp C, et al. Prognosis factors in probands with an FBN1 mutation diagnosed before the age of 1 year. Pediatric Res. (2011) 69:265–70. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3182097219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hosokawa S, Takahashi N, Kitajima H, Nakayama M, Kosaki K, Okamoto N. Brachmann-de Lange syndrome with congenital diaphragmatic hernia and NIPBL gene mutation. Congenital Anomalies. (2010) 50:129–32. 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2010.00270.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Donnai D, Barrow M. Diaphragmatic hernia, exomphalos, absent corpus callosum, hypertelorism, myopia, and sensorineural deafness: a newly recognized autosomal recessive disorder? Am J Med Genet. (1993) 47:679–82. 10.1002/ajmg.1320470518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maas SM, Lombardi MP, van Essen AJ, Wakeling EL, Castle B, Temple IK, et al. Phenotype and genotype in 17 patients with Goltz-Gorlin syndrome. J Med Genet. (2009) 46:716–20. 10.1136/jmg.2009.068403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yano S, Baskin B, Bagheri A, Watanabe Y, Moseley K, Nishimura A, et al. Familial Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome: studies of X-chromosome inactivation and clinical phenotypes in two female individuals with GPC3 mutations. Clin Genet. (2011) 80:466–71. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hogue J, Shankar S, Perry H, Patel R, Vargervik K, Slavotinek A. A novel EFNB1 mutation (c.712delG) in a family with craniofrontonasal syndrome and diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. (2010) 152a:2574–7. 10.1002/ajmg.a.33596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yu L, Hernan RR, Wynn J, Chung WK. The influence of genetics in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Perinatol. (2020) 44:151169. 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Klaassens M, Scott DA, van Dooren M, Hochstenbach R, Eussen HJ, Cai WW, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with duplication of 11q23-qter. Am J Med Genet A. (2006) 140:1580–6. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Goumy C, Laffargue F, Eymard-Pierre E, Kemeny S, Gay-Bellile M, Gouas L, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia may be associated with 17q12 microdeletion syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2015) 167a:250–3. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hendrix NW, Clemens M, Canavan TP, Surti U, Rajkovic A. Prenatally diagnosed 17q12 microdeletion syndrome with a novel association with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Fetal Diagnosis Ther. (2012) 31:129–33. 10.1159/000332968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wat MJ, Shchelochkov OA, Holder AM, Breman AM, Dagli A, Bacino C, et al. Chromosome 8p23.1 deletions as a cause of complex congenital heart defects and diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. (2009) 149a:1661–77. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Longoni M, Lage K, Russell MK, Loscertales M, Abdul-Rahman OA, Baynam G, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia interval on chromosome 8p23.1 characterized by genetics and protein interaction networks. Am J Med Genet A. (2012) 158a:3148–58. 10.1002/ajmg.a.35665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Slavotinek A, Lee SS, Davis R, Shrit A, Leppig KA, Rhim J, et al. Fryns syndrome phenotype caused by chromosome microdeletions at 15q26.2 and 8p23.1. J Med Genet. (2005) 42:730–6. 10.1136/jmg.2004.028787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wat MJ, Beck TF, Hernández-García A, Yu Z, Veenma D, Garcia M, et al. Mouse model reveals the role of SOX7 in the development of congenital diaphragmatic hernia associated with recurrent deletions of 8p23.1. Human Mol Genet. (2012) 21:4115–25. 10.1093/hmg/dds241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Longoni M, Russell MK, High FA, Darvishi K, Maalouf FI, Kashani A, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of ZFPM2 mutations and deletions causing congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Genet. (2015) 87:362–7. 10.1111/cge.12395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Klaassens M, van Dooren M, Eussen HJ, Douben H, den Dekker AT, Lee C, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia and chromosome 15q26: determination of a candidate region by use of fluorescent in situ hybridization and array-based comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Hum Genet. (2005) 76:877–82. 10.1086/429842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.High FA, Bhayani P, Wilson JM, Bult CJ, Donahoe PK, Longoni M. De novo frameshift mutation in COUP-TFII (NR2F2) in human congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Med Genet A. (2016) 170:2457–61. 10.1002/ajmg.a.37830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kantarci S, Casavant D, Prada C, Russell M, Byrne J, Haug LW, et al. Findings from aCGH in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH): a possible locus for Fryns syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. (2006) 140:17–23. 10.1002/ajmg.a.31025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Slavotinek AM, Moshrefi A, Lopez Jiminez N, Chao R, Mendell A, Shaw GM, et al. Sequence variants in the HLX gene at chromosome 1q41-1q42 in patients with diaphragmatic hernia. Clin Genet. (2009) 75:429–39. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01182.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Shaffer LG, Theisen A, Bejjani BA, Ballif BC, Aylsworth AS, Lim C, et al. The discovery of microdeletion syndromes in the post-genomic era: review of the methodology and characterization of a new 1q41q42 microdeletion syndrome. Genet Med. (2007) 9:607–16. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181484b49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Slavotinek AM, Moshrefi A, Davis R, Leeth E, Schaeffer GB, Burchard GE, et al. Array comparative genomic hybridization in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: mapping of four CDH-critical regions and sequencing of candidate genes at 15q26.1-15q26.2. Euro J Human Genet. (2006) 14:999–1008. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. (2015) 17:405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Longoni M, High FA, Qi H, Joy MP, Hila R, Coletti CM, et al. Genome-wide enrichment of damaging de novo variants in patients with isolated and complex congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Human Genet. (2017) 136:679–91. 10.1007/s00439-017-1774-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Merrell AJ, Ellis BJ, Fox ZD, Lawson JA, Weiss JA, Kardon G. Muscle connective tissue controls development of the diaphragm and is a source of congenital diaphragmatic hernias. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:496–504. 10.1038/ng.3250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]