Abstract

Adolescents are at high risk of skin cancer. Since protecting the skin from the sun’s ultraviolet rays is an important way to prevent this disease, the present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of teaching skin cancer prevention behaviors using the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) in male students in Isfahan. An intervention study examined change in attitudes and behaviors among 104, 13-year-old male students from two schools in Isfahan, Iran. The schools were randomized to either receive or not receive a 5-session skin cancer prevention curriculum based in PMT theory. Data were collected using a validated questionnaire that included demographic, PMT, and behavior construct variables. Questionnaires were completed by both groups before and 2 months after the intervention. Data were analyzed using SPSS 20, chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, paired t-test, and McNemar’s test. The results indicated that the mean scores of all constructs of PMT increased in the intervention group compared to the baseline assessment, except for the response cost (P < 0.001). The mean score of students’ skin cancer preventive behaviors was 39.6 (21.4) in the intervention group, and it increased to 74.7 (23.5) after educational intervention, while the control group did not exhibit any significant behavior change. The intervention certainly shows the potential for being effective over the short-term. Therefore, it is recommended that PMT-based educational interventions be designed to teach and promote social health, particularly at an early age.

Keywords: Skin cancer, Prevention, Student

Introduction

Skin cancer is a common cancer in most countries of the world, including Iran [1]. There is evidence that the incidence, prevalence, and DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) can be reduced through prevention; however, they have disproportionately increased among different demographic groups [2].

Multiple risk factors play roles in the incidence of skin cancer, the most important of which include exposure to ultraviolet rays of the sun and tanning. Some risk factors, such as having white skin and bright eyes, having numerous moles, family history, immunodeficiency, and radiotherapy are involved in its incidence [3–5].

Adolescents are particularly spending more time exposed to the sun during summer and weekends than other age groups, as 80% of exposure to the sun occurs before the age of 21[6]. Furthermore, many adolescents do not adequately protect themselves from the sun, and most of them experience severe sunburn [6]. Exposure to sunlight during childhood and adolescence plays a key role in the development of skin cancers and is associated with an increase in the number of melanocytic nevi. Children and adolescents are more exposed than adults [2, 6].

By teaching a few simple strategies, such as minimizing the time of exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) at the peak hours of sunlight, standing in the shade, and using appropriate sunscreen, the occurrence of this cancer can be prevented [7]. Studies indicate that central theory interventions were considered effective in the prevention of skin cancer from 2000 to 2015 [8]. Given the determinants of skin cancer protection behaviors, including awareness, attitudes, self-efficacy, perceived susceptibility and severity [9], and the findings of other preventive interventions, the protection motivation theory (PMT) was considered in the present study an effective framework in creating cancer-preventive behaviors [8–11].

According to this theory, threat appraisal evaluates maladaptive behaviors and includes rewarding misbehavior and understanding the threat (severity and susceptibility). Rewarding misbehavior increases the likelihood of choosing maladaptive reactions, while threats reduce the likelihood of choosing maladaptive reactions. Fear is a mediating variable between perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and threat appraisal. Therefore, if individuals realize that they are susceptible to a considerable health threat, they experience higher levels of fear, thereby increasing their motivation to perform preventive behavior (protective behavior) [12].

Isfahan is located in a semi-desert region in central Iran, and its cancer rate has dramatically increased [13]. Children spend several hours of their time at school exposed to sunlight; hence, the school environment is appropriate in teaching and creating a pattern of preventive health behavior [7, 14]. The present study aimed to examine the application of PMT in teaching preventive behaviors of skin cancer among male students of Isfahan to develop educational programs with effective strategies for improving protective behaviors.

Methods

Study Design and Sampling

This is a pilot study evaluating the intervention in two schools randomized to intervention or non-intervention. The target group was 13-year-old male first-grade high school students in Isfahan in 2019. The sampling method was as follows: Education District 3 from five education districts of Isfahan was selected, and two high schools out of 47 high schools were chosen using the simple random sampling method. Then, a school was randomly regarded as the intervention group, and the other school as the control group. Fifty-two students were selected from each school for the intervention and control groups using the systematic random sampling method and the table of random numbers.

Based on assuming a confidence level of 95%, a test power of 80%, and a drop probability of 10%, a sample size of at least 100 was sought (15). However, 104 students were finally recruited.

The first-grade high school students entered the study voluntarily and had no known skin diseases. Absence from more than one teaching session and transfer to other schools were considered as drop-outs.

Data Collection

A reliable questionnaire, whose validity and reliability had already been confirmed, was used to collect data [15]. The questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) basic demographic information (including age, education level, parental education, father’s job, mother’s job, family income per month, and a history of sunburn); (2) the PMT questions in eight items (perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived rewards, fear, self-efficacy, response efficacy, response cost, and protection motivation); (3) preventive behaviors for skin cancer. The PMT section consisted of 34 questions designed based on the 5-point Likert scale and each item was scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Eight questions were about skin cancer preventive behaviors. The PMT constructs consisted of the following items: (a) perceived susceptibility, for example: If I am exposed to sunlight for a long time, I am more likely to get skin cancer; (b) perceived severity, for example: Sunburn can cause serious damage to my skin; (c) self-efficacy, for example: I can use sunscreen whenever I am exposed to the sun; (d) response cost, for example: Sunscreens are expensive; (e) perceived rewards, for example: Sunlight increases a person’s health; (f) fear, for example: I get worried when I think of skin cancer; (g) protection motivation, for example: I intend to use sunscreen with a protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher when I am exposed to the sun for a long time; and (g) response efficacy, for example: I can prevent skin diseases by using sunscreen. Prevention behavior items included eight 3-point Likert scale questions, which were scored from 1 (never) to 3 (always). For example: Do you use sunscreen on summer days?

For ease of comparing, all scores of different parts of the questionnaire were reported based on 100.

Validity and Reliability of Data Collection Tools

The content validity index (CVI) of the questionnaire was higher than 0.79, the content validity ratio (CVR) of the questionnaire was higher than 0.75, and the internal consistency of the questionnaire was calculated 0.78, using Cronbach’s alpha [15].

The parents and students received the explanation of the research purpose and signed the written consent forms before the study. The questionnaires were designed anonymously, and the students and parents were reassured about the information confidentiality.

Educational Program

The educational intervention for the intervention group consisted of five 60-min sessions of lecture, question and answer, slideshows, and practical displays that were performed in groups at certain schools. The educational content included the importance of skincare, incidence of skin cancer, risk factors for skin cancer, harmful effects of sunlight, ways of protection from the sun, methods of proper use of sunscreen, and other means of preventing skin cancer. To continue the educational program, the taught content was provided in pamphlets to students. To determine the effect of the educational program, the questionnaires were re-completed 2 months after the intervention by both control and intervention groups. According to the constructs of the educational model and reliable sources, necessary training was given to the intervention group during five teaching sessions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of teachings in the sessions based on the PMT constructs

| Sessions | Educational goals | Target construct | Titles of activity | Educational method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Cogitative | Awareness | Increasing knowledge about cancer statistics, the impact of the sun’s rays on the skin and hours of risk, and danger signs, protective equipment and materials, the use of protective equipment |

Lecture Using educational slides |

| Second | Affective-cognitive | Perceived susceptibility, severity, and rewards | Susceptibility to dangers of sun exposure without protective equipment and understanding the benefits of using sunscreen, and the risk of skin cancer if personal sun protection measures are not taken |

Group discussion Educational video Educational pamphlet |

| Third | Affective-cognitive | Fear | Overcoming the fear of the risk of skin cancer, and understanding the benefits of using sun protection equipment |

Educational video Presentation of statistics Questions and answers |

| Fourth | Affective-cognitive | Response efficacy, Self-efficacy |

Trust in the ability of sun protection equipment (long-sleeved clothing, caps, sunscreen) Trust in the benefits of not being exposed to sunlight during critical hours of sunlight Trust in the benefits of spending fewer hours of sun exposure |

Using educational models with the help of educational videos and plays; verbal encouragement; identifying and introducing classmates who regularly perform protective behaviors |

| Fifth | Affective-cognitive | Protection motivation and behavior | Helping to make effective decisions in performing protective behaviors (visiting a doctor to see abnormal symptoms on the skin, paying attention to media messages, using reliable information sources, adopting appropriate protective methods depending on personal-environmental conditions), and preparing and having protective equipment | Teaching the practical method of applying sunscreen in the classroom; educational videos |

Statistical Analysis

The status of skin cancer prevention behavior and other variables in the intervention and control groups were evaluated, and the data were analyzed using SPSS 20. After completing the questionnaires, the data were compared using Mann–Whitney and chi-square tests to compare demographic characteristics (education level, income level, and experience of sunburn) in both groups. The paired t-test was employed to compare the constructs of PMT in each group before and after the educational intervention. McNemar’s test was used to compare the frequency distribution of different types of sun protection behaviors in each group before and after the intervention, and α < 0.05 was considered the significance level.

Results

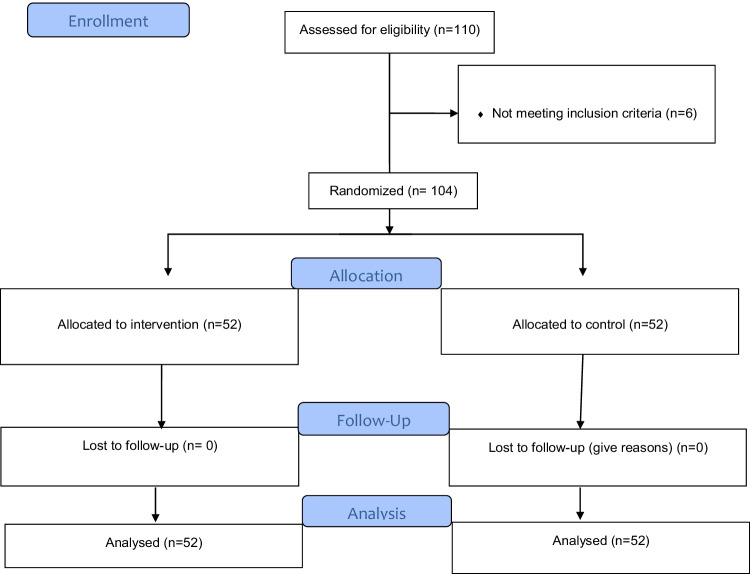

In this study, considering the inclusion criteria, 104 people from two schools were selected and randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups. All students were present until the end of the intervention and none of them were excluded from the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

In the baseline assessment, 66.5% of the students in the intervention group and 53.8% of the students in the control group reported a history of sunburn in the past. However, no significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of demographic characteristics and percentage of sunburn (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and behavioral characteristics at baseline

| Variable | Intervention | Control | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |||

| Having Sunburn history | 33 | 66.5 | 28 | 53.8 | 0.32* | |

| Father’s job | Employee | 24 | 46.2 | 15 | 28.9 | |

| Self-employed | 23 | 44.2 | 31 | 59.6 | 0.35* | |

| Worker | 1 | 1.9 | 2 | 3.8 | ||

| Retired | 4 | 7.7 | 4 | 7.7 | ||

| Mother’s job | Housewife | 41 | 78.8 | 38 | 73.1 | 0.49* |

| Employee | 11 | 21.2 | 14 | 26.9 | ||

| Father’s education level | Primary school | 1 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| Secondary school | 1 | 1.9 | 4 | 7.7 | 0.42** | |

| High school diploma and higher | 50 | 96.2 | 48 | 92.3 | ||

*chi-square test

**Mann–Whitney U test

The paired t-test indicated that the mean score of the response cost was significantly lower in the intervention group after the intervention than before the intervention (P = 0.02). This finding indicates a reduction in barriers to preventive behaviors for students. However, the mean scores of other PMT constructs as well as the behavior score were significantly higher after the intervention than before the intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 3). Performing cognitive interventions in different domains using behavioral change strategies has led to an increase in scores of PMT constructs.

Table 3.

Comparison of mean scores of protection motivation theory constructs and behavior in the intervention group before and after the intervention

| Constructs | Pre-intervention (N = 52) | Post-intervention (N = 52) | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | 44.6 | 25.2 | 83.1 | 18.6 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived severity | 55.1 | 25.1 | 87.9 | 11.9 | < 0.001 |

| Self-efficacy | 66.6 | 20.6 | 82.3 | 12.8 | < 0.001 |

| Response cost | 47.8 | 15.7 | 37.8 | 24.7 | 0.02 |

| Response efficacy | 60.9 | 20.6 | 85.8 | 13.6 | < 0.001 |

| Rewards | 46.3 | 18.2 | 58.3 | 25.3 | 0.01 |

| Fear | 65.9 | 22.6 | 81.4 | 20.9 | < 0.001 |

| Protection motivation | 58.4 | 15.4 | 89.4 | 13.1 | < 0.001 |

*Paired t-test

The same test demonstrated a lack of significant changes in the mean scores of the PMT constructs in the control group after the intervention (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of mean scores of protection motivation theory constructs and behavior in control group before and after intervention

| Constructs | Pre-intervention (N = 52) | Post-intervention (N = 52) | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) | ||

| Perceived susceptibility | 44.9 | 27.5 | 45.1 | 27.1 | 0.96 |

| Perceived severity | 54.6 | 26.2 | 54.5 | 26.01 | 0.88 |

| Self-efficacy | 66.8 | 20.7 | 67.3 | 19.9 | 0.22 |

| Response cost | 47.4 | 19.6 | 48.5 | 24.1 | 0.94 |

| Response efficacy | 59.2 | 18.9 | 58.9 | 20.2 | 0.84 |

| Rewards | 45.3 | 20.5 | 46.6 | 24.5 | 0.76 |

| Fear | 64.7 | 30.6 | 63.6 | 24.8 | 0.57 |

*Paired t-test

McNemar’s test indicated that the frequency rates of using sunscreen, caps, and long-sleeved clothes were not significantly different in the control group before and after the intervention but was significantly higher in the intervention group after the intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency distribution of sun protection behaviors in the two groups before and after the educational intervention

| Time | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | P-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | ||

| Sunscreen | Intervention | 21 | 40.4 | 37 | 71.2 | 0.003 |

| Control | 17 | 32.7 | 17 | 32.7 | 1 | |

| Cap | Intervention | 20 | 38.5 | 34 | 65.4 | 0.01 |

| Control | 25 | 48.1 | 24 | 46.2 | 0.99 | |

| Long-sleeved clothing | Intervention | 17 | 32.7 | 30 | 57.7 | 0.03 |

| Control | 17 | 32.7 | 12 | 23.1 | 0.36 | |

*McNemar’s test

Discussion

The present study examined changes in sun protective beliefs and behaviors after a 5-week educational intervention using PMT. The mean behavior of protection from the sun was undesirable in students before the intervention; however, teaching based on the protection motivation constructs improved skin cancer prevention behaviors in the male adolescents. The PMT constructs (except for the response cost) significantly increased, and the behavior improved significantly in the intervention group after education.

In PMT, the intention to perform protective behavior is created during two main cognitive processes while encountering danger. When students recognize risk factors, they could overcome their fear, and then adopt appropriate behavior. This theory is based on two pillars: (1) threat appraisal, mediated by perceived susceptibility and perceived severity and (2) coping appraisal, mediated by response efficacy and self-efficacy, determining preventive behaviors. Furthermore, individuals’ intention and social support shape their behavior. Social support is also formed in the light of informational, emotional, appraisal, and instrumental support [16, 17].

UV exposure is a preventable skin carcinogen [14], so that limiting UV exposure or regularly using sunscreen, seeking shadow, wearing sunglasses, wearing skin protection clothing, and not using artificial tanning devices can reduce the risk of skin cancer by more than 75% [18]. Some known factors have prevented protective behaviors. Previous studies have mentioned the lack of awareness about the relationship between sunlight and cancer and the harmful effects of sunlight in adolescents [11]. Studies indicate that students are not sensitive to the risk of skin cancer and do not feel a high risk of developing cancer at this age [19]. The beauty and attractiveness due to tanning evoke a reward in adolescents’ minds, so that they ignore the risk of cancer [10, 19] and are not afraid of its incidence [11]. Furthermore, factors such as support received from parents and friends, having a positive attitude towards wearing protective clothing, high self-efficacy, and high perception of skin cancer risk, have been introduced as predictors of skin cancer preventive behaviors [11, 20–23]. Perception of effective response and self-efficacy of sun protection behaviors are higher than adaptive behavior response costs [24]; therefore, protection motivation leads to the creation and promotion of more self-care behaviors [25]. Therefore, assuming the students’ training sessions and providing them with the necessary information and attitude, they considered the possibility of developing skin cancer severe with higher susceptibility; they had a higher self-efficacy and exhibited better protective behaviors to protect their skin; hence, they often used sunscreen, sunglasses, and caps.

Sotoudeh et al. (2020) indicated that 43% of skin cancer preventive care behaviors in seafarers were predictable by the PMT constructs [26]. One intervention study by Velasqause et al. (2016) indicated that while half of the students aged 9–12 years did not have sufficient knowledge about the relationship between self-caring behaviors and skin cancer, they perceived the risk of association between sunlight and skin cancer and observed skincare behaviors, including the use of sunscreen and skincare at critical hours after learning through lectures and games [11]. Similarly, Persson et al. (2018) conducted a review study and determined that interventions were significantly effective in preventing sun exposure immediately after the intervention and 12 months after the intervention [27]. Dehbari et al. (2015) found a significant relationship between the PMT constructs except for perceived rewards and methods of sun protection [28]. Studies on other social classes, including farmers, revealed that increase of self-efficacy and protection motivation scores significantly increased skin cancer preventive behaviors [5, 29, 30].

The results of a study in France showed that conducting educational intervention, although it increased students’ awareness, did not change preventive behaviors against the sunburn [31]. Aslo, based on PMT, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, response efficiency, self-efficacy, and protection motivation are among the known constructs in performing preventive behaviors against diseases, such as COVID-19 [32], Pap smear to prevent cervical cancer [33], improving breast self-examination behavior in the prevention of breast cancer [34], and physical activity in type-2 diabetic patients [35], confirming appropriateness of health-related behavior training based on the PMT and enhancing health-related behaviors. Based on other models or theories of behavior change, other researchers demonstrated the effectiveness of education, so that they implemented a comprehensive skin cancer prevention program by the University of Texas and Houston University of Medical Sciences for preschools based on the social cognitive theory that expanded knowledge, improved self-efficacy, and removed obstacles in all preventive behaviors for sun protection behaviors in children [36].

The measurement of variables through self-reporting and not examining the roles of parents, teachers, and peers in adopting protective behavior against the sun are important limitations of the study. Given that this intervention was performed in a specific geographical area, specific care should be taken in generalizing the results of the present study. In this study, the development of a clear conceptual framework using the theory of protection motivation caused the interventions to be implemented more effectively for the target group, which can be considered as a strength of this study.

Conclusion

It is essential to design and implement programs to improve the skin cancer protective behavior in students from an early age to prevent undesirable and irreparable damage to the skin owing to slighter inclination to use protective equipment. Since PMT is a useful guide to explain cancer-related preventive behaviors, this theory can be used to design interventions to promote skin cancer prevention behaviors in different groups of people. The results recommend appropriate and effective ways for health planners and authorities to design large-scale educational programs.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the all the officials and staff of the selected schools, and all the students who are the main owners of this research.

Abbreviation

- PMT

Protection motivation theory

Author Contribution

Initially conceived and designed the study: Afsaneh Maleki and Hossein Shahnazi.

Conducted the analysis: Akbar Hassanzadeh.

Wrote the paper and made revisions: Hossein Shahnazi and Seyede Shahrbanoo Daniali.

Reviewed the manuscript critically: Hossein Shahnazi.

The final version of the manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, and the requirements for authorship have been met.

Funding

The Isfahan University of Medical Sciences funded this study. However, this grant did not cover the most sections of this study.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Deputy of research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (ID number: IR.MUI.REC.1397.081). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants. Furthermore, the students were assured of the study confidentiality.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Afsaneh Maleki, Email: erfanhp6@gmail.com.

Seyedeh Shahrbanoo Daniali, Email: sh_daniali@yahoo.com.

Hossein Shahnazi, Email: h_shahnazi@yahoo.com.

Akbar Hassanzadeh, Email: Hassanzadeh.aja@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Razi S, Enayatrad M, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Salehiniya H, Fathali-Loy-Dizaji M, Soltani S. The epidemiology of skin cancer and its trend in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:64. doi: 10.4103/2008-7802.161074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagelhout ES, Parsons BG, Haaland B, Tercyak KP, Zaugg K, Zhu A. Differences in reported sun protection practices, skin cancer knowledge, and perceived risk for skin cancer between rural and urban high school students. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(11):1251–1258. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Correia O, Correia B, Duarte AF. A skin cancer prevention campaign: spreading the word on sugar packets. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(2):129–30. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016 (2016) CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 66(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wernli KJ, Henrikson NB, Morrison CC, Nguyen M, Pocobelli G, Blasi PR. Screening for skin cancer in adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 2016;316(4):436–447. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alberg AJ, Herbst RM, Genkinger JM, Duszynski KR. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors toward skin cancer in Maryland youths. The Journal of adolescent health: official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2002;31(4):372–377. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban K, Mehrmal S, Uppal P, Giesey RL, Delost GR. The global burden of skin cancer: a longitudinal analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990–2017. JAAD International. 2021;2:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdin.2020.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taber JM, Dickerman BA, Okhovat JP, Geller AC, Dwyer LA, Hartman AM. Skin cancer interventions across the cancer control continuum: review of technology, environment, and theory. Prev Med. 2018;111:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripp MK, Vernon SW, Gritz ER, Diamond PM, Mullen PD. Children’s skin cancer prevention: a systematic review of parents’ psychosocial measures. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rouhani P, Parmet Y, Bessell AG, Peay T, Weiss A, Kirsner RS. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of elementary school students regarding sun exposure and skin cancer. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(5):529–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velasques K, Michels LR, Colome LM, Haas SE. Educational activities for rural and urban students to prevent skin cancer in Rio Grande do Sul. Brazil Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(3):1201–1207. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.3.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prentice-Dunn S, McMath BF, Cramer RJ. Protection motivation theory and stages of change in sun protective behavior. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(2):297–305. doi: 10.1177/1359105308100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokarian F, Ramezani MA, Heydari K, Tabatabaeian M, Tavazohi H. Epidemiology and trend of cancer in Isfahan 2005–2010. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(9):1228–1233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bränström R, Kasparian NA, Chang Y-m, Affleck P, Tibben A, Aspinwall LG. Predictors of sun protection behaviors and severe sunburn in an international online study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(9):2199–2210. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshki M, Karimy M, Asl HR, Mojadam M, Araban M. Predictors of sun protection behavior in high school students of Ahvaz: a cross-sectional study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019;32(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Verkijika SF. Understanding smartphone security behaviors: an extension of the protection motivation theory with anticipated regret. J Comput Secur. 2018;77:860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cose.2018.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bubeck P, Wouter Botzen WJ, Laudan J, Aerts J, Thieken AH. Insights into flood-coping appraisals of protection motivation theory: empirical evidence from Germany and France. Risk Anal. 2018;38(6):1239–1257. doi: 10.1111/risa.12938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linares MA, Zakaria A, Nizran P. Skin cancer. Prim Care. 2015;42(4):645–659. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornung RL, Lennon PA, Garrett JM, DeVellis RF, Weinberg PD, Strecher VJ. Interactive computer technology for skin cancer prevention targeting children. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasques K, Michels LR, Colome LM, Haas SE. Educational activities for rural and urban students to prevent skin cancer in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(3):1201–1207. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.3.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vries Hd, Lezwijn J, Hol M, Honing C. Skin cancer prevention: behaviour and motives of Dutch adolescents. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2005;14(1):39–50. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30(2):407–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02323.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiter RA, Kessels LT, Peters GJ, Kok G. Sixty years of fear appeal research: current state of the evidence. Int J Psychol. 2014;49(2):63–70. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norman P, Conner P (2005) Predicting health behaviour: a social cognition approach. M Conner, & P Norman (2nd Ed), Predicting health behavior 1–27.

- 25.Karmakar M, Pinto SL, Jordan TR, Mohamed I, Holiday-Goodman M. Predicting adherence to aromatase inhibitor therapy among breast cancer survivors: an application of the protection motivation theory. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2017;11:1178223417694520. doi: 10.1177/1178223417694520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sotoudeh A, Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Vaezi AA, Fattahi Ardakani M, Sadeghi R. Determining skin cancer protective behaviors in the light of the protection motivation theory among sailors in Bandar-Bushehr in the south of Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(12):3551–3556. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.12.3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persson S, Benn Y, Dhingra K, Clark-Carter D, Owen AL, Grogan S. Appearance-based interventions to reduce UV exposure: a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(2):334–351. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dehbari SR, Dehdari T, Dehdari L, Mahmoudi M. Predictors of sun-protective practices among Iranian female college students: application of protection motivation theory. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(15):6477–6480. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.15.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moeini B, Ezati E, Barati M, Rezapur-Shahkolai F, Mohammad Gholi Mezerji N, Afshari M. Skin cancer preventive behaviors in Iranian farmers: applying protection motivation theory. Workplace Health Saf. 2019;67(5):231–240. doi: 10.1177/2165079918796850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghaffari M, Rakhshandehrou S, Tezval J, Harooni J, Armoon B. Skin cancer-related coping appraisal among farmers of rural areas: applying protection motivation theory. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(6):1830–1836. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quéreux G, Nguyen J-M, Volteau C, Dréno B. Prospective trial on a school-based skin cancer prevention project. Eur J Cancer. 2009;18(2):133–144. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32831362cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezati Rad R, Mohseni S, Kamalzadeh Takhti H, Hassani Azad M, Shahabi N, Aghamolaei T. Application of the protection motivation theory for predicting COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Hormozgan, Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):466. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10500-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malmir S, Barati M, Khani Jeihooni A, Bashirian S, Hazavehei SMM. Effect of an educational intervention based on protection motivation theory on preventing cervical cancer among marginalized women in West Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(3):755–761. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.3.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bashirian S, Barati M, Mohammadi Y, Moaddabshoar L, Dogonchi M. An application of the protection motivation theory to predict breast self-examination behavior among female healthcare workers. Eur J Breast Health. 2019;15(2):90–97. doi: 10.5152/ejbh.2019.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ali Morowatisharifabad M, Abdolkarimi M, Asadpour M, Fathollahi MS, Balaee P. The predictive effects of protection motivation theory on intention and behaviour of physical activity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(4):709–714. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2018.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tripp MK, Herrmann NB, Parcel GS, Chamberlain RM, Gritz ER. Sun protection is fun! A skin cancer prevention program for preschools. J Sch Health. 2000;70(10):395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Deputy of research of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.