Abstract

Child and adolescent mental health indicators were trending in the wrong direction pre-COVID-19 and have worsened with the exacerbation of life stressors during a pandemic, especially among youth of color and girls (Racine et al. in JAMA Pediatr 175:1142–1150, 2021). Hip Hop integrated group work with adolescents has increased in the literature, with an emphasis on being more culturally responsive and engaging compared to traditional therapeutic approaches. Levy and Travis (J Spec Group Work 45:307–330, 2020) found in their research that while all Hip Hop integrated groups were effective, the semi-structured group had the most significant reduction in symptoms of stress, depression, and anxiety, compared to the highly structured and minimally structured groups. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether a Hip Hop integrated intervention, that is multi-modal and interdisciplinary (i.e., blending two distinct models [HHE/CCMC] and facilitated by a social worker and school counselor). could effectively promote positive social and emotional development, across three leadership styles. Three groups of six high school students (total n = 18), identifying predominantly as Latinx and Black, were selected from a high school summer enrichment program. Results suggest social and emotional benefits for youth across all groups, regardless of facilitation style. Benefits included increased confidence, a strong sense of community, experiencing joy, and a willingness to step outside of their comfort zones to collaborate and create something personally meaningful. The setting (summer) and sample (high school students) have implications for programming and policies to best meet the mental health needs of youth year round and during times of instability.

Keywords: Hip Hop, Mental health, Empowerment, SEL, Prevention

In 2019, more than a third of high school students reported experiencing consistent sadness or hopelessness, a 40 percent increase since 2009 (CDC, 2021b). Following these trends, the spread of COVID-19 in 2020 produced additional mental health strains (Newall & Machi, 2020). Among global youth, “clinically elevated child and adolescent depression and anxiety were at 25.2% and 20.5% respectively, which is double pre-pandemic rates and highest among older adolescents and girls” (Racine, McArthur, Cooke et al., 2021, p. E1).

Many parallels exist between the stressors produced by COVID-19-era social isolation and those reported by students during summer months, a phenomenon referred to as “summer strain” by Travis et al. (2019a, b). The term “summer strain,” was introduced to highlight that “student stressors, the residual effects of trauma, and general mental health concerns” persist across summer, and are often a result of “reduced access to school-based structure, support, safety, and services… and a reduced buffer to home instability during these months” (Travis et al., 2019a, b, p. 2). This reduced access to school-based resources impacts key mediators of student mental health including access to food, physical activity, social interaction, structure, as well as parental and familial stress.

If the mental health needs of youth continue unaddressed, especially during summer months, and during high stress times like the COVID-19 era, aside from negative real-time mental health distress it can negatively impact educational outcomes, school attendance, and long-term financial and social factors (Fox et al., 2015). To help promote positive development, social and emotional growth, and reduce the adverse effects of depression, trauma, and suicidal ideation among youth, it is essential to identify innovative ways that social work professionals can help independently and collaboratively with other professions.

The purpose of the present study is to determine the potential social and emotional benefits of a Hip Hop integrated intervention, that is multi-modal and interdisciplinary (i.e., blending two distinct models [HHE/CCMC] and facilitated by a social worker and school counselor). integrated intervention. The setting (summer months) and sample (high school students) have implications for programming and policies to best meet the mental health needs of youth year round and in times of instability like during COVID-19.

Literature Review

Mental Health Trends Across Groups

Among youth today, over one-third of high school students (36.7%) in the United States report feeling sad or depressed, an occurrence twice as likely for females (46.6%) as for males (26.8%) (CDC, 2021a). Reports of sadness and depression also vary by race, affecting 33.7% of Hispanic participants, 29.2% of Black participants, 45.5% of American Indians/Alaska Natives, 31.6% of Asians, 36.0% for Whites, and 45.2% for those who identified as multiracial (CDC, 2021a). The magnitude of these reports is especially prominent when looking at the intersection of gender and race, especially in the case of Latinx women. Statistics show the highest disparity between gender within race for Latinx respondents, with 29.1% of Latinx men reporting feelings of sadness and depression compared to 50.4% of Latinx women, though other races also report significant disparities between gender within race (for example, for white respondents, 25.9% of men and 46.1% of white women, and for black respondents, 22.3% of men and 41.2% of women) (CDC, 2021a).

These mental health concerns also have the potential to be compounded through the co-occurrence of stress, trauma, and anxiety. Anxiety specifically has been the most widespread mental health disorder both in the United States population generally (Bandelow & Michaelis, 2015) as well as among youth ages 13–17 (Merikangas et al., 2010). Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for those between the ages of 10 and 35, with rates steadily climbing (Kann et al., 2018; National Institute of Mental Health, 2018). In 2019, 17.2% of high school students reported they had seriously considered attempting suicide (CDC, 2021a).

Youth, Summer Stress, and COVID-19

The literature regarding youth and summer stress is relatively sparse, though existing research has identified mediators of poor mental health during the summer for youth as including food insecurity (Morgan et al., 2019; Stretesky et al., 2020; Turner & Calvert, 2019), loneliness/social isolation (Morgan et al., 2019), physical activity (Morgan et al., 2019), structure (Boylan, 2019), and parental stress (Stretesky et al., 2020), with disproportionate effects on low SES individuals (Morgan et al., 2019; Turner & Calvert, 2019).

These stressors have taken on a continued significance extending beyond summer months with the spread of COVID-19, the accompanying general shift to online learning, and socio-economic and emotional instability. These added stressors and tensions overlap with those reported in summer stress studies, including a disproportionate impact on marginalized communities (Fortuna et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020; Levinson et al., 2020). The global pandemic has increased social isolation (Chen et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020), family stressors (including increased need for childcare, limitations with parental ability to return to the workforce, and parent–child conflicts) (Johnson et al., 2020; Levinson et al., 2020), financial strain (Dunn et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020; Levinson et al., 2020), and food insecurity (Dunn et. al, 2020; Stretesky et al, 2020).

Interdisciplinary Goals and Strategies: Social Work and School Counseling

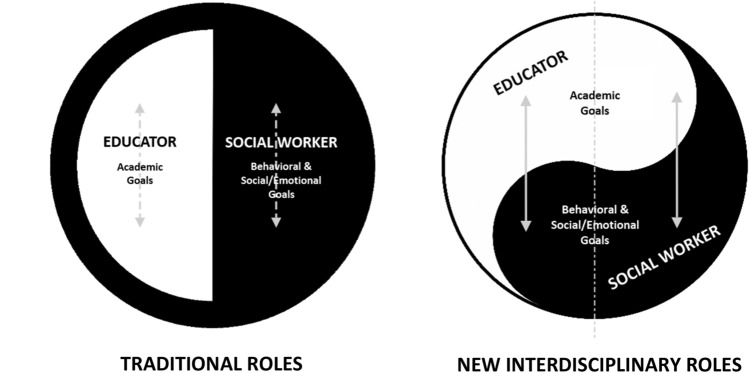

Intervention responses to both pre-pandemic stressors and the new COVID-19 landscape of stressors that school-age youth endure, must include thoughtful collaborations between potentially isolated mental health professionals. A more integrated social work position within the school ecosystem can help bring clarity to the intersections and relationship between social work and school counseling roles (Gherardi & Whittlesey-Jerome, 2018; Lim & Wong, 2018; Maras et al., 2015; Porter et al., 2000; Yu & Chiang, 2017). Studies point to necessary school counseling tasks that overlap with family life, tasks traditionally associated with social work (Lam, 2005; Smith, 2018). Alternatively, there are similar interdisciplinary ventures of social workers into the academic world and traditional realms of school counseling (Gherardi & Whittlesey-Jerome, 2018). These reciprocal advances in interdisciplinary approaches for school counseling and social work support the development of a flexible model of interdisciplinary practice for social worker where they support academic, social, and emotional development (Fig. 1). Interdisciplinary collaboration between social work and school counseling is naturally facilitated by the shared professional values and guiding principles of both social work and school counseling. Each discipline follows a comprehensive code of ethics (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2016; National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2017), and maintains a commitment to social, emotional, and academic development. Existing literature and practice trends provide a strong foundation for collaborative interdisciplinary work in general, and for Social Work and School Counseling in particular. More opportunities are needed to further assess social worker’s ability to work collaborative within school environments to provide uniquely engaging culturally responsive interventions year-round.

Fig. 1.

Traditional and non-traditional education and social work roles

Culturally Responsive and Creative Strategies for Mental Health

The threats to emotional well-being for Black and Latinx youth, and the disparities by gender and intersectionalities, illustrate the value and need for using culturally responsive interventions to ameliorate stressors and enhance coping strategies. Current mental health services are often group-based and have been critiqued for their lack of cultural relevance (Chu et al., 2016). As a result, there is a need to continue exploration of the efficacy of different culturally sensitive approaches to improving youth mental health. More specifically, it is important to understand the effectiveness of summer mental health-based group work with lower-SES youth. Results may inform efforts to improve mental health outcomes and address the cumulative stress that accompanies summer strain.

Existing interventions with some evidence of success include academic enrichment programs (Bowers & Schwartz, 2017; Lenhoff et al., 2020; Nicholson & Tiru, 2019; Shinwell & Defeyter, 2017), summer camps (Garst & Ozier, 2015; Kirschman et al., 2010; Riley & Anderson-Butcher, 2012), food outreach programs (Collins et al., 2018; Litt et al., 2020; Turner & Calvert, 2019; Turner et al., 2019), and more recently, computer-based and online offerings for summer academic support (Boyd, 2018; Osborne & Shaw, 2021; Pindiprolu & Marks, 2020), and Hip Hop culture and music integrated approaches (Levy & Travis, 2020; Travis et al., 2019a, b).

Music Engagement and Mental Health

Strategies to promote positive development and optimal mental health through music can range from informal to highly-structured, formal interventions. Effort may be informal self-care strategies by individuals, general prevention and education strategies guided by facilitators, or more structured and codified therapeutic regimens such as the Critical Cycle of Mixtape Creation (Levy & Travis, 2020), Hip Hop Therapy (Tyson, 2002), Rap Therapy (Elligan, 2000), Hip Hop Empowerment (Travis et al., 2020), and Therapeutic Beat Making (Travis et al., 2019a, b). Thus, people may choose to engage music in their everyday life for learning, growth, or coping, recognizing its empowering and health-enhancing effects, with or without any professional or facilitator-mediated support (Anyiwo et al., 2021; Batt-Rawden et al., 2007; Travis, 2013, 2016).

Individual engagement and collective/social music engagement, whether in person or digitally online, are being represented more clearly as vehicles for development, human connectedness, and well-being. Digital social music engagement can be more receptive when experiencing a produced livestream concert, or DJ set (e.g., passively watching/listening but not communicating [i.e., “lurking”], or by interacting with digital music experiences with “likes” or comments in the live chat stream), or the more active end of the spectrum through music making (e.g., livestreaming independently produced music or collectively creating music together such as the Hip Hop based Global Beat Cypher (Next Level, 2020).

Hip Hop Integrated Intervention Models

Research in social work, school counseling and allied disciplines have found evidence of effectiveness for Hip Hop integrated strategies in promoting well-being among youth, with individuals and groups (Alvarez, 2012; Burt, 2020; Ciardiello, 2003; DeCarlo & Hockman, 2004; Donnenwerth, 2012; Gann, 2010; Travis, Rodwin, and Allcorn, 2019b; Tyson, 2002). More specifically by discipline, professionals have theorized about and developed practices to promote positive development and inhibit negative mental health using Hip Hop culture within social work (Alvarez, 2012; DeCarlo & Hockman, 2004; Evans, 2020; Leafloor, 2012; Tillie, 2005; Tyson, 2002; Travis & Deepak, 2011), psychiatry (Hakvoort 2015; Inkster & Sule, 2014), psychology (Abdul-Adil, 2014; Dang et al., 2014; Gann, 2010; Winfrey, 2009), school counseling (Armstrong & Ricard, 2016; Elligan, 2000; Gonzalez & Hayes, 2009; Levy, Emdin, & Adjapong, 2018a, b; Washington, 2018), youth development (Hicks Harper et al., 2007), and music therapy (Geipel, Koenig, Hillecke, Resch, & Kaess, 2018; Lightstone, 2012; Rolvsjord, 2010; Viega, 2016).

The positive correlates of professionally-mediated music engagement continue to be reflected conceptually, but more importantly empirically. Individual level and group-based intervention efficacy in improving mental health outcomes has been demonstrated qualitatively and quantitatively. Highlights from recent positive impacts from therapeutic uses of Hip Hop include a mixed methods RCT showing improved self-regulation (Uhlig, Jansen, and Scherder, 2019), and quantitative, quasi-experimental designs showing reduced depression and anxiety (Travis et al., 2019a, b) and reduced stress (Levy & Travis, 2020). Levy (2019) showed quantitative evidence of a significant progression in emotional coping. A single study case design (Gulbay, 2021) and a synthesis of the literature (McFerran, Lai, Chang et al., 2020) found evidence of reduced PTSD symptoms. Qualitative studies showed improvements in PYD outcomes with youth in detention (Hickey, 2018) and among younger and older adults struggling with homelessness and mental health (Travis, Rodwin, and Allcorn, 2019). Qualitative findings also found improvement in SEL and growth areas, for identity and relationships (Richards et al., 2019) and emotional self-awareness (Levy, 2019).

Multiple Methods, Multiple Modalities, and Global Approaches

The range of Hip Hop and well-being strategies use different conceptual models and often emphasize different aspects of Hip Hop culture as guiding the theories of change. However, most emphasize Hip Hop culture’s roots in self and social awareness alongside its many opportunities for regulation, self-expression, identity development, and shaping personal narratives (Travis, 2016, pp. 55–57). These principles can be found in Hip Hop integrated opportunities for learning, growth, and social change that began in the United States but now extend across the globe (Uhlig, Jansen, and Scherder, 2019). For example, Gulbay (2021) not only blended multiple elements of Hip Hop culture, but also blended different methods of Hip Hop integrated therapeutic interventions, and trauma treatment perspectives. They created a sequential model from the synthesized categories of approaches to music-based therapies for trauma developed by McFerran et al. (2020), moving from stabilization, to entrainment, to expressive (“exploratory”), to performative strategies. Gulbay’s (2021) Integral Hip Hop Methodology, focused on asylum seekers and unaccompanied minor migrant youth, is the ultimate multi-method and interdisciplinary approach applicable to meet the needs of youth and young adults around the globe. Additionally, Brown and Nicklin (2019) examined the positive individual and community impacts of an experiential Hip Hop integrated project which sought to help facilitate personal well-being, learning, and active and engaged citizenship. Participants connected to global social issues through critical pedagogy and Hip Hop culture.

The two distinct conceptual models for the present study, Hip Hop and Empowerment (social work) and the Critical Cycle of Mixtape Creation (school counseling), anchor self and social awareness within all facets of the tested intervention. Further, these two guiding models emphasize a person-centered approach, recognizing the importance of positive and supportive 1-on-1 and group relationships, and the necessity of creating a safe supportive space for programming activities.

The Hip Hop and Empowerment (HHE) System

The purpose of the Hip Hop and Empowerment system of strategies, grounded conceptually in the EMPYD framework, is to create empowering music and art-based experiences (i.e., receptive, or active) anchored in Hip Hop culture. Listening, watching, analyzing, creating, or otherwise engaging Hip Hop’s elements (e.g., emceeing, deejaying or producing) are meant to facilitate the evocation, modulation, or termination of emotions, which helps instigate and reinforce health development. Listening to songs, playlists, or DJ sets, freestyling and improvising lyrics, crafting well thought out lyrics, creating beats, developing DJ or beat sets, making songs (combining beats and lyrics), remixing songs, are just a few of the ways people engage the culture. Maximizing empowerment while inhibiting risk is the goal. Therapeutic effects are measured by positive developmental, social, and emotional capacities, attitudes, and behaviors (Travis, 2016, pp. 128–131).

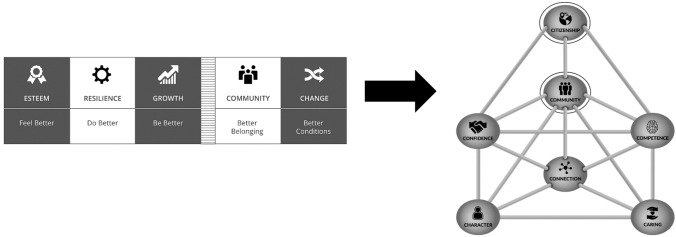

At the conceptual core of the HHE approach are five distinct but overlapping dimensions of empowerment (i.e., esteem, resilience, growth, community, and change) as outlined in the Individual and Community Empowerment framework (ICE) (Travis & Bowman, 2015; Travis & Deepak, 2011). This framework proposes that these dimensions facilitate health development and capture normative developmental processes of self and community improvement, which are core values in Hip Hop culture (Travis, 2016, p. 5). Further there is recognition of the potential for high to low risk amid all empowerment narratives. Thus, all Hip Hop integrated activities can be analyzed through narrative lenses based on these dimensions, as even the most hedonistic and risky art content often includes narratives of esteem and resilience (Travis, 2016, pp. 84–86).

The five ICE dimensions of empowerment, as universal developmental narratives that span person and environment to promote individual improvement and community improvement, offer tremendous flexibility for helping professionals to understand, develop and guide educational, therapeutic, and health promotive experiences (Travis, 2013, 2016). The ICE framework allows attention to emotional regulation, identity development, affirming strengths, and creating healthy narratives (esteem); it allows attention to cathartic expression, validation, and healthy coping with trauma and adverse experiences (resilience); it allows attention to renewal, healthy decision-making, post-traumatic growth, positive and supportive relationships, and mentorship (growth); it allows attention to social identities, social networks, belonging, and cultural or collective resilience (community); and it allows attention to equity, justice, and working to inhibit stress and trauma inducing environments (change) (Travis, 2016, pp. 55–56).

Again, Hip Hop culture is used to connect, emotionally engage, and create an environment that facilitates empowerment, for individuals and the communities they care about. Hip Hop engagement can help facilitate self-awareness and self-regulation, but also social awareness and looking outward toward and with others (Travis & Deepak, 2011; Travis et al., 2019a, b). These Hip Hop integrated experiences are hypothesized to and have shown to help inhibit negative mental health outcomes, and promote positive development and SEL outcomes (Travis et al., 2019a, b; Travis et al., 2019a, b).

The Critical Cycle of Mixtape Creation

Levy, Cook, and Emdin (2017) describe the Critical Cycle of Mixtape Creation (CCMC) and the creation of a Hip Hop mixtape as “a distinct Hip Hop cultural process.” Cultural notions of a “mixtape” vary, from (a) live recordings of Hip Hop’s earliest pioneers like Cold Crush Brothers, to (b) skilled mixes and sequenced song “blends” in the tradition of Kip Capri and Ron G. (and regionally specific pioneers like DJ Screw), to (c) less-mixed collections of “exclusives” by unknown or lesser known artists in the tradition of DJ Clue and Funkmaster Flex, to (d) carefully curated blends of music, words, and other forms of cultural expression (Ball, 2011; Noz, 2013). Some consider anything that is not a studio album a mixtape.

From the CCMC model and activities of the present study, a mixtape is a product consisting of a collection of group participant-created songs with lyrics and beats, all developed as part of the therapeutic intervention (Levy, Emdin, & Adjapong, 2018a, b, p. 106). The CCMC model adopts youth participatory action research (YPAR) processes, coupled with Hip Hop and spoken word therapy strategies (Levy, 2019). YPAR’s investigative inquiry (Cook & Kruger-Henny, 2017) aligns with CCMC’s use of researching what youth deem important during the song construction process (Levy, Cook, and Emdin, 2018a). As a model for group work, mixtape making takes youth through researching, discussing, creating, and disseminating emotionally-themed Hip Hop music about issues in and around their lives. To accomplish this goal, helpers who use the CCMC in group work take young people through a series of steps that include: Identifying Action Mixtape Area of Interest, Researching Mixtape Content, Discuss and Digest Findings, Developing a Tracklist, Planning the Recording and Release of Mixtape, and Evaluating Mixtape Process and Response to Release (Levy, Cook, and Emdin, 2018a, p. 6). Preliminary research integrating the CCMC model suggests that it has a promising impact on emotional well-being factors like stress, anxiety, and depression (Levy & Travis, 2020).

When investigating the mental health impacts of the combined HHE/CCMC interdisciplinary approach, Levy and Travis (2020) found significant quantitative reductions in anxiety, depression, and stress for participants, across multiple leadership styles. PYD and SEL indicators are hypothesized to mediate these desirable mental health outcomes.

PYD and SEL

Positive Youth Development (PYD) and Social Emotional Learning (SEL) are common desired outcomes of prevention and interventions efforts and key indicators of well-being. PYD, introduced and operationalized early by Roth and Brooks-Gunn (2003), Eccles and Gootman (2002, pp. 60–83), and Lerner et al. (2005), is often referred to merely as “youth development” (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2016). Taylor et al. (2017) describe PYD as a process (not an outcome), as prioritizing “enhancing youth strengths, establishing engaging and supportive contexts, and providing opportunities for bi-directional, constructive youth context interactions” (p.1157). SEL captures efforts to strengthen competencies across three linked areas, including: (1) cognitive skills, (2) emotional competencies, and (3) social and interpersonal skills (Jones & Kahn, 2017).

CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning) has helped to popularize and operationalize SEL as: (1) self-awareness, (2) social awareness, (3) self-management, (4) positive decision-making, and (5) relationship skills (CASEL, 2021). While PYD and SEL have different conceptual roots, there is overlap in “emphasizing the importance of reinforcing positive developmental outcomes that enable youth to thrive psychologically, emotionally, socially, and behaviorally” (Travis et al., 2019a, b, p. 747).

Researchers have been investigating the correlations among PYD and SEL constructs (Ross & Tolan, 2018; Taylor et al., 2017). Interpretations of SEL components differ among researchers and practitioners. For example, social awareness is identified and measured by Ross and Tolan (2018) as more of a pro-social character oriented characteristic (p. 1180), while CASEL (2021) emphasizes “the ability understand the perspective of and empathize with others,” but also to “understand broader historical and social norms… situational demands and opportunities… influences of organizations and systems on behaviors” (CASEL, 2021). Further, one of the earliest articulations of PYD by Lerner et al. (2005) describes competence as “positive views of one’s actions in domain specific areas including social, academic, cognitive, and vocational” (p. 23). Travis and Leech (2014) and Travis (2016) with the Empowerment-based Positive Youth Development (EMPYD) framework use a broader and interrelated conceptualization of PYD indicators, including a definition of competence that aligns with the CASEL features of social awareness. The importance of sense of community and engaged citizenship are also emphasized as crucial reinforcing features of development (Fig. 2) especially for youth of color and marginalized youth (Travis & Leech, 2014).

Fig. 2.

ICE to EMPYD: Hip Hop’s empowerment narratives as reflections of reinforcing pathways of youth development

The purpose of the present study is to determine the potential social and emotional benefits of a one week HHE/CCMC integrated intervention for a sample of high school students during the summer. More specifically, the present project helps to answer the major research question: (1) In what ways do students report experiencing social and emotional growth as a result of participating in an integrated multi-modal and interdisciplinary Hip Hop based intervention (“Mixtape Camp”)?

Methods

Participants

This study occurred during a high school student summer enrichment program held at a university in Southwest Texas. During a six-week long summer enrichment program, a total of 18 high school aged-youth volunteers participated in a five-day Hip Hop mixtape camp for an hour and 45 min per day. Of these 18 individuals, eight identified as girls and ten identified as boys. Three of the participants identified as Black, ten identified as Latinx, and two identified as multi-racial/multi-ethnic Black and Latinx. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) with the university of one of the co-researchers.

To secure study participants, researchers advertised broadly to the summer program participants and then told program leaders that a maximum of 30 youth could participate (i.e., ten per group). All parental consents were obtained prior to the start of the camp. Consent was received for 18 participants. The list of names was divided into three equal groups of six by camp leadership. The students were placed in groups based on which group meeting time best fit their daily schedule within the broader camp schedule.

Setting

The experiences provided in the present study were structured as a mental health support extension of the larger high school summer enrichment program. The study took place in primarily two medium sized rooms, including a music studio with a wide range of music technology and software. The studio provided a space grounded in Hip Hop culture, both functionally and aesthetically, where the research study could take place. The music technology (e.g., MacBook, Ableton Push, and MIDI keyboards) and software (e.g., Ableton Live, Logic Pro, and ProTools) provided sufficient material to create high quality music. The hardware and software were consistent with creating music within Hip Hop culture, and were appropriate for creating a wide range of music genres (Crooke, 2018). The studio provided several workstations generally used for therapeutic interventions, research, and education. Participants used this space to engage in recording, lyric writing, and beat creating. There was also an adjacent classroom-type space with computers, speakers, a chalkboard, and multiple tables that were arranged in a large square so that all participants could face each other during discussions. In the classroom-type meeting space, participants researched lyric content and engaged in group discussions around music videos and song lyrics.

Procedures

Facilitators designed and implemented the five day Hip Hop intervention, or Mixtape Camp. One facilitator is a licensed clinical social worker, and the second facilitator is a licensed school counselor. A local teaching artist and producer, who specialized in working with youth and beat production, helped facilitate the music technology and music-making aspects of the week-long mixtape camp. The 18 students were separated into three groups of six. To respond to the gap in the literature exploring the ideal leadership style to use in Hip Hop integrated group work, the researchers structured each of the three groups differently.

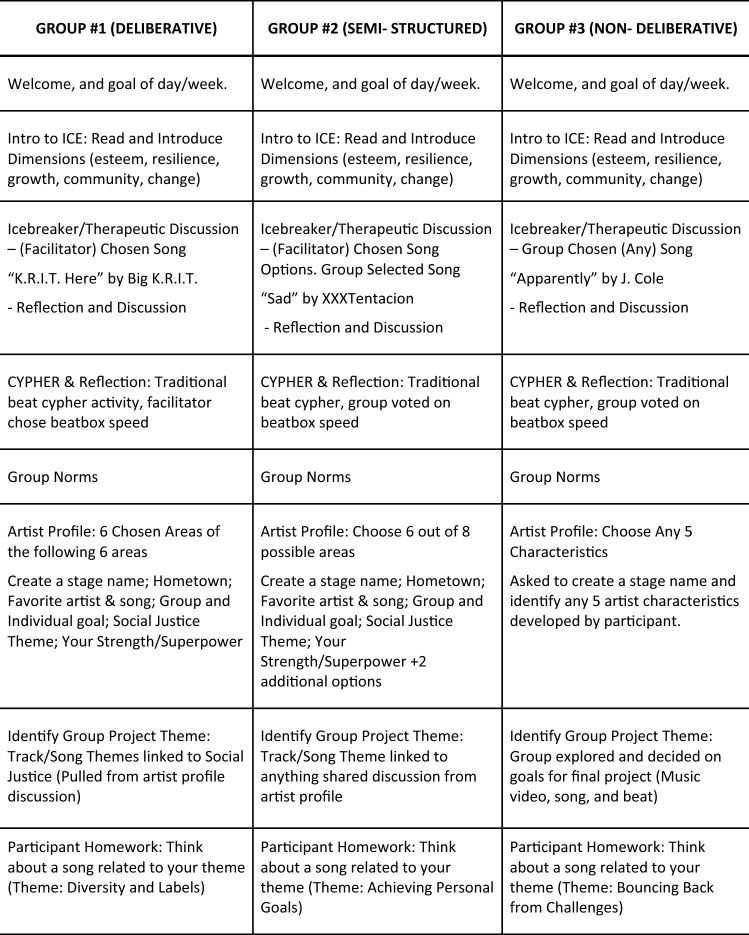

The first group (Group 1) was a deliberative group structure, where youth were taken through the CMCC process in order to create a social justice themed song. The semi-structured group used the CMCC model to support youth in completing an emotionally themed Hip Hop song about any issue they identified as important to them. During the second, semi-structured group (Group 2), a variety of choice points were given to enable youth to take more of a leadership role than the deliberative group in guiding the direction of their experiences and the overall mixtape creation process. Lastly, the third, non-deliberative group (Group 3) used the CCMC process to provide youth much more autonomy in their experiences. Youth were given the opportunity to create any type of Hip Hop related project (e.g., song, video, drawing, dance, skit) about any topic they mutually agreed to explore. Figures 3 and 4 provides a comprehensive overview of daily activities (for Day 1) with differences in curriculum design across groups.

Fig. 3.

Mixtape camp curriculum across three leadership styles, day 1

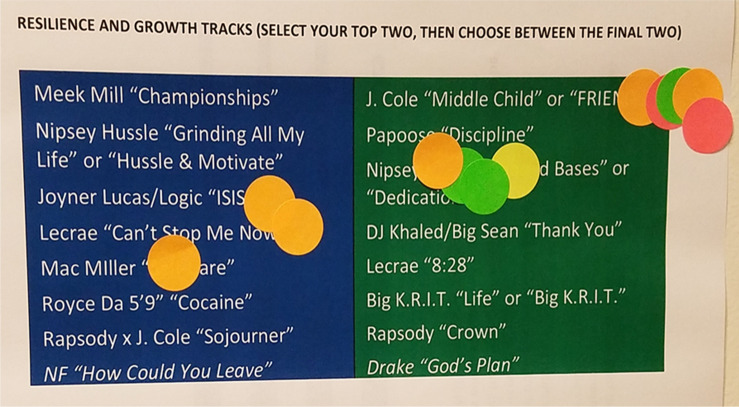

Fig. 4.

Song selection results for therapeutic discussion based on the resilience and growth (empowerment) dimensions, day 2

Throughout the week, each group worked through the process of writing, researching, recording, and performing their project at a final camp listening party. In accordance with CCMC principles and HHE dimensions of empowerment, the week included: Day 1: Identifying an area of interest (esteem); Day 2: Researching and digesting content for their project (resilience/growth); Day 3: Developing a product (community/change); Day 4: Recording and planning the release of the project (esteem to change review); Day 5: Sharing and evaluating the project. Though each of the groups was facilitated with a different leadership style, each group followed the core CCMC structure integrated with key elements of the HHE system. For example, Day 1 had a core objective of identifying an area of interest (CCMC) while also exploring the esteem dimension of empowerment throughout group activities (HHE).

Data Collection

Qualitative data were the primary data interpreted to answer the research questions. Data were collected from a post-intervention focus group. The aim of the focus group was to explore participant experiences during the mixtape group process, as well as assess how they believe the group processes impacted them. More specifically, the focus group was conducted in the format of a “Post Show Debrief” which occurred at the conclusion of the camp after the final group performances (each group presented and discussed their created project). This method of measurement is consistent with the Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) framework of: Dissemination (Final Performance/Show) + Intervention Recap (Picture/Video Montage as Primer) + Evaluation (Focus Group/Post-Show Debrief) (Cook & Kruger-Henny, 2017).

As authors were interested in understanding participants’ lived experiences, an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) framework was used for the interview guide development, data collection procedures, and data analysis. These questions included: “What was this process like for you all this week?”, “What was the song about your project?” “So, thinking about the overall week, what is something that you'll take away from this experience?” and “Are there any questions, thoughts, comments?” (Note: this question was used to solicit any number of questions/comments from the audience). Following IPA, after each question from this semi-structured interview, facilitators were able to ask impromptu follow-up questions.

Data Analyses

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was selected as an approach to qualitative data collection and analyses by the research team because it supports gathering a detailed understanding of how participants make meaning of their experiences in social contexts (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin, 2009). As a subjective phenomenological approach, IPA privileges focusing on participants' reflections as data, with focus on understanding meaning of the experience as opposed to gathering a quantifiable number of themes (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014). Thus, social and emotional growth constructs were discerned and interpreted after analysis, as opposed to being interpreted from a priori identified SEL-specific codes (see Hickey, 2018 for a priori based coding of Hip Hop integrated programming outcome data). Focus group data were used as the basis for IPA, drawn from a culminating component of the mixtape camp, in a listening party format where youth shared their songs with their peers. Each group played their song, and answered questions about their experiences in the group, and their song (Groups 1, 2, and 3) and video (Group 3) development. These group reflections were audio recorded and used as focus group data, as they allowed youth to describe their experiences in their own words.

Following the IPA methodological process, a flexible and semi-structured interview guide was used, for the purpose of positioning participants as the leaders of the discussion content (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin, 2009). Prior to the listening party, the researchers met with youth to collectively brainstorm what questions should be asked during the listening party (focus group). While specific questions were selected by youth, the facilitators, in accordance with IPA, were able to ask follow-up questions as needed to clarify meaning. Each of the three groups (n = 6) had 20 min to present their song and engage in a follow-up focus discussion about their song and group process. Transcriptions of the focus groups were collected for data analysis.

The purpose of IPA in this study was to illuminate the meaning behind the student focus groups. Following IPA data analysis steps, first two researchers downloaded the transcriptions into separate Word documents, read and re-read the contents, and then engaged in their own identification of codes that signified meaning (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin, 2009). Next, all codes were placed beneath lower-order themes that used a descriptive word or short phrase to the common meaning between the codes. All codes sat beneath lower-order themes which were finally grouped beneath high-order themes (Saldaña, 2016). While each researcher engaged in this process independently to generate meaning about students' experiences in the mixtape camp, they eventually met together to reconcile findings. Researchers compared their respective lists/themes to mutually decide on a final list. Much deliberation took place to finalize the title of lower-order and higher-order themes so that they accurately reflected the complexities of the codes that sat within them. Potential alignment of themes with PYD and SEL concepts was investigated to help answer the research question about the program’s ability to facilitate growth.

Trustworthiness

Once a final list was compiled, the two researchers turned to the third member of the research team to serve as an auditor (Patton, 2015). This auditor role required the third researcher to review the work of their colleagues with the goal of highlighting any missing codes or themes within the analysis, and increasing rigor/agreement in the final list of themes (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009). The first two authors met, reviewed the feedback from the auditor, and made changes to the lists of themes. Finally, they were able to confirm a final list of themes, organized in Table 1 in higher- and lower-order theme rows and in columns by all groups combined.

Table 1.

A Numerical count of each different participant comment by higher (H) & lower-order (L) themes

| Higher & lower-order themes | N (18) |

|---|---|

| Collective impact of group processes (H) | 18 |

| Icebreakers and building comfort (L) | 3 |

| Collaborating and creating community (L) | 10 |

| Beyond comfort (L) | 7 |

| Fun and joy together (L) | 7 |

| Enjoyed finalizing project (H) | 17 |

| Youth selected personally meaningful topics (L) | 11 |

| Active and creative decision-making (L) | 6 |

Results

Results suggest multiple examples of social and emotional growth linked directly to programming activities, especially group processes and the project-based element of creating a final product within programming. Again, IPA methods were used to analyze the collected data and answer the research question: In what ways do students report experiencing social and emotional growth as a result of participating in the summer program? Through data analysis from focus groups with all 18 youth participants, the following two higher-order themes and respective lower-order themes emerged: (1) Collective Impact of Group Processes (containing the lower-order themes of Icebreakers and Building Comfort Collaborating, Creating Community Beyond Comfort Fun, and Joy Together) and (2) Enjoyed Finalizing Project (containing the lower-order themes of Youth Selected Personally Meaningful Topics and Active and Creative Decision-making). Participant quotes are showcased to illustrate the results with more depth and with more specificity especially through the lenses of social and emotional growth. Frequencies for higher and lower-order themes are listed across the full sample and within the three groups (Table 1).

Collective Impact of Group Processes

The first higher-order theme describes myriad ways in which participants were positively impacted by group processes throughout the week. The structure of the program is filled with group processes, guided by HHE and CCMC theories of change that emphasize the importance of relationships and building community to promote or reinforce positive development and SEL competencies. For example, (a) the cypher, (b) the empowerment and therapeutic discussions, and (c) the steps needed to create the final group project, are all group based processes meant to facilitate PYD and SEL outcomes. The Collective Impact of Group Processes included four lower-order themes: (1) Icebreakers & Building Comfort, (2) Collaborating & Creating Community, (3) Growth Beyond Comfort, and (4) Fun & Joy Together.

Icebreakers & Building Comfort

Each day started with icebreakers and activities meant to build community. Participants felt that these collective-oriented group activities and ice-breakers, (e.g., Creating a Cypher, Introducing ICE, and Therapeutic Discussions) allowed them to develop a sense of comfort within the group. A sample quote from a student reflecting on group cyphers captures this theme:

The movement... with all of us working together, be able to walk in - they didn't show y'all but we would come in every single day, and we would do cyphers pretty much. Pretty much, we would make our own beats, switch directions, and switch the rotation around. And pretty much we got to see how creative we all were together. And to be able to meet each and every one of you and getting to know you better, it was pretty awesome so…

In this quote we hear that participating in the daily cypher activity (where youth circled up and created a collective drum beat with a sound they created on their own with their mouth or a nearby object) sparked and validated individual and group creativity. The participant also affirmed the value of the cypher in helping group members to notice each other’s strengths and creativity, and to start to develop supportive relationships with each other.

Collaborating & Creating Community

The second lower-order theme, Collaborating & Creating Community indicated that the overall group process, and daily structured group activities (i.e., cypher, introduction to ICE, therapeutic discussions, creating the hook), promoted cohesion amongst group members. The strong rapport within the group as a whole was apparent in two distinct student quotes. First was, “Now we're all family.” Family is even more of a powerful sense of connection and community than “friends.” This hints at the magnitude of closeness some participants felt by the end of the camp. Next was the statement, “We became more comfortable around each other, just being there with each other every day, working together as a group.” Again, the sense of community is tied to collaboration and working together on a regular basis. Respectively, these quotes illuminate the closeness that group members created during group work. After working together as a group, they equated the level and quality of comfort they experienced to being with family.

Growth Beyond Comfort

The third lower-order theme, Growth Beyond Comfort reflects participant beliefs about their growth from pushing through discomfort. This is consistent with ideas of growth that occurs from facing and overcoming adversity. For example, one student stated:

I think coming out of your comfort zone is a big one. Because you don't really know people. So, it's just like you don't really want to associate yourself, but you have to because you want to make something cool out of it.

The student explains how coming out of their comfort zone was an active process as opposed to a passive process. There was agency in actively transcending discomfort in front of people that they didn’t know very well. While the prior theme also highlighted how the group facilitated a sense of comfort, this lower-order theme captures specific pathways to comfort. Through ice breakers and other activities within the group process, students embraced and worked through vulnerabilities to increase their comfort and ultimately more fully engage in the intervention.

Fun & Joy Together

The fourth lower-order theme, Fun & Joy Together, detailed how students felt engaged. They had fun and experienced joy with their peers during group processes. One quote states, "It wasn't all serious about beats and music, it was getting to know each other.” In this quote the student explains how music and beat making were enjoyable because they functioned as pathways for connection and relationship building that didn’t feel too serious. Another student described group interactions as “Yeah. Just having a good time with each other.” Feelings of enjoyment appeared to pervade the group process.

Enjoyed Finalizing Project

Building on this notion of collective fun and joy, the second higher-order theme was Enjoyed Finalizing Project. In these statements students explained how much they enjoyed the process of creating their projects. They fell within two lower-order themes: a) Youth selected personally meaningful topics and b) Active and creative decision making.

Youth Selected Personally Meaningful Topics

The first lower-order theme, Youth Selected Personally Meaningful Topics, included statements illustrating students’ personal connections to, and meanings behind, the content they created. For example, when discussing their song one student said:

My favorite line was "we set our own limits, we'll show you what we got, those in the hood", the last line. I picked that one because we're all self-imposed people and we set our own potential, whether it's high or low. We do it, we set our own expectations for ourselves.

In this statement, a participant talks about one lyric from their song, where they processed their own expectations and potential. In particular, the participant reflected on the importance of defining their own potential, disallowing others to do that for them. A second quote details another created song lyric:

I think for me, my favorite part was "don't try to hide from other people's sins" because y'all see other peoples, like they didn't get to have a chance to go to college or didn't get this opportunity and y'all see that and y'all don't wanna do it either. So, I love that line.

Here the participant shares a feeling of appreciation for, and dedication too, the higher education opportunities they lay ahead for them. While the student might know people who did not have the opportunity to go to college, or chose not to go, like they soon would, they did not want to miss their opportunity. They conveyed a focus on their personal goals, but also showed an awareness of both unequal opportunities and the impacts of choice and decision-making.

Active and Creative Decision Making

Within the second and last lower-order theme, Active and Creative Decision Making, participants reflected on the creative decisions they made to complete their projects. An excellent exemplar reflecting on both the final track and the process leading to the completed track is:

My favorite part was the switch up and the beat. Pretty much, it was different, creative, and just coming up with the idea was one and number two right here. It was pretty awesome so just get to see how we can try something else other than just sticking to that same beat was pretty awesome and I just liked that.

In this quote the participant walks us through the creation of a beat. While working with the our in-house producer, they were able to actualize creative ideas that deviated from the normal way they understood beat making. This quote highlights how creative and empowered the student felt by the decisions they were able to make about their Hip Hop project. Another statement showcases a similar sentiment, “…it's brainstorming the ideas and making them all fit into what we all wanted, but at the end we all had similar choices, ideas.” Part of the group's creative process pushed students to collaborate with each other to make joint decisions that reflected the shared interests of the whole group. Having the flexibility to brainstorm together, and the interpersonal skills to collaborate in a positive manner, led to a concrete shared decision.

Discussion

The present study found opportunities for students to improve in positive development and grow socially and emotionally through Hip Hop integrated programming. Results suggest that social and emotional growth can occur through group (or “community”) reinforced empowerment, and project-based creative art experiences—specifically through a Hip Hop cultural lens. Results also highlight the potential for an integration of Hip Hop based techniques, being multi-modal and interdisciplinary with social work and school counselor facilitators.

The core theories of change guiding the models in this study drew from this rich conceptual and empirical history of Hip Hop integrated strategies. Results of the present study included displays of self-awareness, social awareness, relationship skills, self-management/self-regulation, and responsible decision-making among participants working together during group processes to create their Hip Hop project. But even more importantly, results highlighted how important a sense of community and self-regulation was for participants as they developed and created uniquely meaningful projects.

Aside from general well-being, participants also had fun and experienced joy, which is known to help improve friendship quality and reduce internalizing symptoms (Smith, 2015). The ability for individuals coping with race and ethnicity-based stress and trauma to see, share (i.e., social media), and experience more joy has been expressed as especially important for mental health (Black Youth Project, 2017; Charles, 2020). Yet, strategies to promote joy are critically under-investigated in research. Results align with prior research suggesting that Hip Hop integrated strategies help to promote well-being and promote potential mediators of well-being. Study findings also echo research showing Hip Hop based strategies (a) are more engaging for some (i.e., participants express more enthusiasm and excitement about joining and continuing to participate in the group) than traditional talk-based strategies (Dang, Vicon, Abdul-Adil, 2014; DeCarlo & Hockman, 2004; Travis et al., 2019a, b; Tyson, 2002; Washington, 2018), (b) are culturally consistent (DeCarlo, 2001; Elligan, 2000; Levy, Emdin, Adjapong, 2018; Travis, 2016; Tyson, 2003; Washington, 2018), and (c) promote all elements of PYD (Hickey, 2018; Levy, Hess, Elber, and Hayden, 2020; Travis and Rodwin, 2018) and SEL (Levy, 2019), and (d) when group-based, can amplify natural, collective, therapeutic principles of community and mutual aid (Levy, Emdin, Adjapong, 2018, p.105; Levy & Travis, 2020).

Group Processes: Creating Community

Students relished the idea that community could be established so quickly among relative strangers, and that this new community could propel them throughout the week and in creating art that captured all of their voices and talents. They talked together, they had fun together, they created together, they validated each other, they critically analyzed together, they overcame nervousness together, they were vulnerable together, they shared an appreciation of music and art together and so much more. This quickly developed positive and supportive environment aligns with research suggesting the significant value of creating spaces that are deliberately, proactively, and enthusiastically grounded in principles of mutual support, validation, and encouragement in words and gestures as in the Hip Hop cypher, especially when emotionally significant content is explored (Levy, Emdin, & Adjapong, 2018a, b, pp. 107–109; Travis & Rodwin, 2019, pp. 92–93). Students “grew” together by overcoming existing anxieties to not only get comfortable, but to actually have fun together for a co-created project.

The value placed by students on growing together and becoming more comfortable aligns with interpersonal emotion regulation (i.e., co-regulation) and positive and safe relational experiences (Rosanbulm and Murray, 2018). The CCMC is anchored by the principle of the Hip Hop cypher as a cultural practice of mutual support and intimacy that is able to “unite and affirm” (Levy, Emdin, and Adjapong (2018a, b). Hip Hop and Empowerment strategies similarly prioritize the importance of sense of community, for people to feel empowered in general, but also to reinforce positive and supportive relationships (i.e., connection) and other important areas of development. The present study supports these CCMC and HHE principles, and Travis and Leech’s (2014) premise that “belonging to a masterful community” exists for individuals when the powerful feelings of belonging associated with sense of community are continually and reciprocally reinforcing other youth development indicators. More specifically, community amplifies and reinforces “the mastery network” of connection, confidence, and competence, “through the ongoing support, learning and growth within the safe and healthy environment of the community (e.g., a family, school, team, or club)” (Travis & Leech, 2014, pp. 102–103). Evidence suggests that the Mixtape Camp was a masterful community for participants, where the space allowed them to connect, and build their confidence, on the way to exceptional learning and creative growth.

Results were strikingly similar to findings from Hickey (2018) who found that a Hip Hop integrated intervention over five years within a juvenile justice setting had the top two most frequently coded responses from participants (i.e., over 70% of responses) as competence and positive feelings. Learning something new, creating something new, and achieving a goal were very meaningful. Positive feelings of fun, joy, and experiential love of the process were also highly valued by participants. At the same time, the challenge of overcoming doubts and working through learning something new was similarly valued. Alternatively, the intervention included more independent experiences as opposed to group experiences. Thus, the interpersonal relatedness and collective oriented findings anchored in group experiences that were in the present study were not prominent in the findings of Hickey (2018). In a study of adults participating in a Hip Hop integrated mental health program by Richards (2018), one of the three main impacts alongside the affirmation of identity and escaping from the present was “connection to others and building relationships” (p. 483).

Further, findings saw SEL competency-building among participants as evidenced by “high self and social awareness, positive and supportive relationship skills, and responsible decision-making” throughout project development and completion (Ross & Tolan, 2018). Each group created song topics (and Group 3 created a video too) meant to affirm, validate, inspire, and educate others. Travis and Leech’s (2014) EMPYD framework, which helps guide HHE strategies, incorporates conceptual features of PYD and SEL. However, their framework and thus HHE strategies include SEL competencies as part of EMPYD competence. Competence is linked to other interrelated and reinforcing EMPYD/HHE constructs including caring and sense of community (Fig. 2). Thus, the ongoing, reinforcing positive development process reflected in the mastery network (building confidence, functional music skills + SEL competencies) is further buoyed within a positive, supportive, and empowering collection of social relationships (1-on-1 relationships + the collective group relationship). Even further, as a testament to growth in social and emotional competencies in the present study, when Group 2 members were given the choice of potential focus group questions, they decided to create all of their own prompts, showcasing high levels of self-awareness, social awareness, and decision-making skills.

Results also expand existing work on the perceived social and emotional benefits of Hip Hop engagement across different life stages through this lens of empowerment. Prior findings have been both quantitative and qualitative explorations, but there had yet to be extensive qualitative findings among high school participants. Prior studies included middle school youth (Travis et al., 2019a, b), high school youth (Travis & Bowman, 2012), college students (Travis & Bowman, 2015; Travis & Maston, 2014; Travis et al., 2016), and adults (Travis et al., 2019a, b).

Art Creation: Creating a Collective and Meaningful Hip Hop Project

The core premise of the Critical Cycle of Mixtape Creation is for participants to collectively drive a process of creating art together (Levy, Cook, and Emdin, 2018a). It is an active process of music engagement. It is anchored in Hip Hop culture and based on emotional engagement. Mixtape making is rooted in YPAR which is intentionally flexible in allowing youth to guide how projects are created—shifting power dynamics to position youth as researchers and able to generate solutions to issues within their lives (Cook & Kruger-Henny, 2017). This model enabled youth in different groups to create qualitatively different creative art products. For example, Group 3 when given the option to “create anything you like” elected to create a music video in addition to a song. This malleability is captured within the lower-order theme of active and creative decision making. Aligned with the premise of YPAR, utilizing Hip Hop based approaches in group work offers youth a platform to create their own products, in their own ways, on their own terms, while still developing socially and emotionally.

The results of the current study also extend the theoretical grounding for Hip Hop and spoken word therapy as a platform for youth to write, record, and perform emotionally themed Hip Hop music (Levy, 2019). In the context of group work, Hip Hop mixtape making supports youth engaging in action research about various social and emotional themes in their lives (Levy, Emdin, & Adjapong, 2018a, b), noted as aiding the reduction of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms for Black and Latinx youth (Levy & Travis, 2020).

Interdisciplinary, Multiple Methods, and Multiple Modalities

The present study and results add to recent research blending disciplines, methods, and models while examining arts-integrated strategies for academic, social, and emotional development. The present study provides the specific conceptual and practical underpinnings of two distinct Hip Hop based modalities, developed by individuals representing social work and school counseling, with use of multiple elements/methods from Hip Hop culture. t

An increasing number of Hip Hop based efforts combine Hip Hop elements like emceeing and deejaying/beatmaking through programming centered on lyric writing, music production and creating finished songs. However, few bring together distinct therapeutic models to create a new integrated model with augmented objectives that transcend either of the distinct models.

Even more, results add to research suggesting the value of combining multiple Hip Hop based modalities. Combining modalities follows recent research examining the efficacy and benefits of combining Therapeutic Beat Making and HHE strategies (Travis et al., 2019a, b) and the Integral Hip Hop Methodology which combines elements of Therapeutic Beat Making, Hip Hop and Empowerment, principles from McFerran et al.’s Spectrum of Approaches to Music and Trauma, and other therapeutic tools (Gulbay, 2021).

Further, the present study adds to research about creating more complex methodologies within research to help strengthen the quality of evidence and practice strategies. The current research also helps to provide a concrete example of how to blend school counseling and social work practices to help promote student well-being; offering opportunities for future innovation across the mental health treatment spectrum—from self-care, to prevention, to treatment. There is tremendous flexibility for using these strategies as standalone change models, and the possibilities are exponential when used in partnership with other models.

Policy and Practice Implications

Results suggest that while substantial support exists for academic support during the summer months (to address summer slide or summer melt), there is a need for a more concerted effort toward social and emotional support to address potential summer strain. Further, there is room for strategies that promote both receptive and active engagement of music. Results also suggest that policies and procedures are needed that support intentional and conscious use of music by individuals needing help whether or not they participate in traditional therapeutic activities (i.e., whether they engage music alone or with a professional). Lastly, further research is needed on interdisciplinary approaches, and multi-modal or blended Hip Hop integrated approaches to therapeutic music engagement.

Beyond Summer Slide: Mental Health Strategies/Funding

Strategies to address summer slide/summer melt can benefit from incorporating SEL objectives as well. While the concept of summer slide continues to be debated (Kuhfeld, 2019), resources exist, and the substantive data and evidence for SEL benefits on well-being has little debate (Durlak et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2017). Support and opportunities for interdisciplinary and multimodal creative art strategies is important. First, evidence suggests continued exploration of interdisciplinary strategies is important. Neth et al. (2020) found that a program facilitated by counselors and social workers has been especially helpful in promoting SEL and reducing internalizing mental health symptoms.

Marginalized Youth: By Gender and by Race

It is also critical to think about intersectionality, recognizing that disparities are unique among youth with multiple intersecting identities and the influences of their social environments (Appleseed Network, 2020; Mann, Whitaker, Torres-Guillen et al., 2019). For example, negative depressive outcomes are often most disparate for girls, women, and individuals that identify as LGBTQ (Reinert, Nguyen, and Fritze, 2021; Soklaridis et al., 2020). Suggested interventions based on research, within practice and public policy include investments in: (1) positive and supportive relationships, (2) positive developmental and culturally responsive school settings, and (3) the quantity and quality of mental health supports.

Efforts like the Elementary and Secondary School Counselors Act (Mann, Whitaker, Torres-Guillen et al., 2019; NAS, 2021) and H.R. 5469, the Pursuing Equity in Mental Health Act speak to the desire for a greater presence of school-based mental health professionals in schools, such as social workers, psychologists, counselors, and nurses, and the concern that exists about the negative impacts of excessive law enforcement and school resource/discipline officers (Mann, Whitaker, Torres-Guillen et al., 2019).

Limitations

While the present intervention and results spoke to core values of the social work and school counseling profession, including attention to the well-being of the person, self-determination, empowerment-in-context, and social justice as an influence on the well-being of individuals, the present study had several limitations to consider for future research. Three key limitations were a smaller sample size, relying on self-report data, and not teasing out separate impacts of the different therapeutic elements of the intervention. Sample size is especially important for calculating statistically significant differences, but since these data are qualitative it is less of an issue. However, there is still a risk of non-generalizability. A larger sample could allow for more confidence in answers based on larger group trends, but also greater depth and nuance to qualitative responses. Similarly, only self-report data does not provide the opportunity to triangulate agreement about findings across multiple data sources. For example, had project facilitators and camp counselors also indicated in separate interviews that students grew closer over the course of the week, could not stop talking about the fun they were having creating their project, and new levels of confidence, then the self-report data would be even more convincing.

Lastly, a limitation is not teasing out elements of the intervention for potential separate impacts. For example, are there equal impacts for receptive and active strategies? Is lyric analysis and therapeutic discussion as health promotive as therapeutic lyric writing? Does each general stage of the CCMC approach carry equal weight? Addressing these in future work could provide a more robust analysis of the effects of Hip Hop integrated therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion

The ability to meet mental health needs of young people is especially important during times of stress and environmental instability, phenomena prominent for many during summer months and more broadly during the COVID-19 era. Interventions that help youth and young adults reduce negative mental health symptoms and promote positive well-being outcomes, are critical. Project-based, creative art approaches, that include Hip Hop integrated strategies, are engaging and culturally responsive opportunities that have shown consistent effectiveness.

Mental health professionals and other helping professionals linked to education have substantial opportunities with Hip Hop integrated approaches. Strategies have shown to be effective independently, but now more complex integration of methods have also demonstrated effectiveness, along with blended modalities. Skilled professionals can help facilitate well-being across the mental health spectrum from promoting self-care, to prevention among higher and lower risk populations, to active treatment, offering a full range of ways to support youth and young adults in times of instability and crisis. There is tremendous flexibility for using these strategies as standalone change models, and the possibilities are exponential when used in partnership with other models.

However, based on potential differing interpretations of SEL, it is important to continue explicating conceptual underpinnings of SEL efforts and desired short and long-term outcomes across different phases of the life-course. Funding priorities, implementation strategies, goals and objectives, and evaluation implications will be influenced by the subjective interpretations of what SEL entails. At the same time, creating connection and developing community, expressivity, and social and emotional growth during periods of isolation, sadness, depression, family strain, and inconsistency in school engagement remains very promising.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdul-Adil J. From voiceless to victorious. See You at the Crossroads. 2014 doi: 10.1007/978-94-6209-674-5_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez TT. Beats, rhymes, and life: Rap therapy in an urban setting. In: Hadley S, Yancy G, editors. Therapeutic uses of rap and hip-hop. Routledge; 2012. pp. 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- American School Counselor Association. (2016). ASCA ethical standards for school counselors. https://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/Ethics/EthicalStandards2016.pdf.

- Anyiwo N, Watkins D, Rowley S. “They can’t take away the light”: Hip-Hop culture and black youth’s racial resistance. Youth & Society. 2021 doi: 10.1177/0044118X211001096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appleseed Network (2020). Appleseed network: Protecting girls of color from the school-to-prison pipeline. Appleseed Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.appleseednetwork.org/uploads/1/2/4/6/124678621/appleseed_network_-_protecting_girls_of_color_2020.pdf.

- Armstrong SN, Ricard RJ. Integrating rap music into counseling with adolescents in a disciplinary alternative education program. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. 2016;11(3–4):423–435. doi: 10.1080/15401383.2016.1214656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball, J. (2011). Mixtape manifesto: I mix what I like! Accessed on 9 August 2021 from: https://imixwhatilike.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/iMiXWHATiLiKE-Full-Book.pdf.

- Bandelow B, Michaelis S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2015;17:327–335. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.3/bbandelow. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batt-Rawden KB, Trythall S, DeNora T. Health musicking as cultural inclusion. In: Edwards J, editor. Music: Promoting health and creating community in healthcare contexts. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2007. pp. 64–82. [Google Scholar]

- Black Youth Project . Black joy is resistance: Why we need a movement to balance Black triumph with trials. Black Youth Project; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers L, Schwarz I. Preventing summer learning loss: Results of a summer literacy program for students from low-SES homes. Reading and Writing Quarterly. 2017;34(2):99–116. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2017.1344943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, A. C. (2018). Perceived parent involvement and a technology-enabled workbook intervention effect analysis on summer learning loss for 6th and 7th grade students attending a Pennsylvania k-12 virtual school [ProQuest LLC]. In ProQuest LLC. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/2007241970.

- Boylan K. Summer can be hard on kids with mental health problems. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019;28(2):14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Nicklin LL. Spitting rhymes and changing minds: Global youth work through hip-hop. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning. 2019;11(2):159–174. doi: 10.18546/IJDEGL.11.2.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt I. I get money: A therapeutic financial literacy group for Black teenagers. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2020;45(2):165–181. doi: 10.1080/01933922.2020.1740845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CASEL (2021). SEL: What are the core competence areas and where are they promoted? CASEL. Retrieved from https://casel.org/sel-framework/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2021a). Youth risk behavior surveillance system United States 2019 youth online data analysis tool [YRBSS]. (2019, June). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline/App/Results.aspx?LID=XX.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2021b). Youth risk behavior survey data summary & trends report 2009–2019 [YRBSS]. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/YRBSDataSummaryTrendsReport2019-508.pdf.

- Charles, S. (2020). Gen Z wants to see more joy and positive moments, less trauma and negativity in their social media feeds. VSCO Press; JUV Consulting. Retrieved from https://vscopress.co/vsco-blog/2020/8/11/gen-z-wants-to-see-more-joy-and-positive-moments-less-trauma-and-negativity-in-their-social-media-feeds.

- Chen B, Sun J, Feng Y. How have Covid-19 isolation policies affected young people’s mental health? Evidence from Chinese college students. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Leino A, Pum S, Sue S. A model for the theoretical basis of cultural competency to guide psychotherapy. Professional Psychology. 2016;47(1):18–29. doi: 10.1037/pro0000055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ciardiello S. Meet them in the lab: Using hip-hop music therapy groups with adolescents in residential settings. In: Sullivan NE, Mesbur ES, Lang NC, Goodman D, Mitchell L, editors. Social work with groups: Social justice through personal, community and societal change. Haworth Press; 2003. pp. 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Klerman J, Briefel R, Rowe G, Gordon A, Logan C, Wolf A, Bell S. A summer nutrition benefit pilot program and low-income children’s food security. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):1–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook AL, Krueger-Henney P. Group work that examines systems of power with young people: Youth participatory action research. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2017;42:176–193. doi: 10.1080/01933922.2017.1282570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crooke AHD. Music technology and the hip hop beat making tradition: A history and typology of equipment for music therapy. Voices. 2018 doi: 10.15845/voices.v18i2.996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dang S, Vigon D, Abdul-Adil J. Exploring the Healing Powers of Hip-Hop: Increasing therapeutic efficacy, utilizing the hip-hop culture as an alternative platform for expression, connection. In: Porfilio BJ, Roychoudhury D, Gardner LM, editors. See you at the crossroads: Hip Hop scholarship at the intersections. Sense Publishers; 2014. pp. 169–180. [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo A. Rap therapy? An innovative approach to groupwork with urban adolescents. Journal of Intergroup Relations. 2001;27(4):40–48. [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo A, Hockman E. RAP therapy: A group work intervention method for urban adolescents. Social Work with Groups. 2004;26(3):45–59. doi: 10.1300/J009v26n03_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnenwerth AM. Song communication using rap music in a group setting with at-risk youth. In: Hadley S, Yancy G, editors. Therapeutic uses of rap and hip-hop. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2012. pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, A., Hood, K., and Driessen. (2020). Measuring the effects of the covid-19 pandemic on consumer spending using card transaction data. US Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.bea.gov/research/papers/2020/measuring-effects-covid-19-pandemic-consumer-spending-using-card-transaction.

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB. the impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development. 2011;82(1):405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Gootman, J. A. (2002). Features of positive developmental settings. Community programs to promote youth development, (pp. 86–118). The National Academies Press. Doi:10.17226/10022.

- Elligan D. Rap therapy: A culturally sensitive approach to psychotherapy with young African American men. Journal of African American Men. 2000;5(3):27–36. doi: 10.1007/s12111-000-1002-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. Connecting Black youth to critical media literacy through hip hop making in the music classroom. Journal of Popular Music Education. 2020;4(3):277–293. doi: 10.1386/jpme_00020_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna LR, Tolou-Shams M, Robles-Ramamurthy B, Porche MV. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(5):443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S, Southwell A, Stafford N, Goodhue R, Jackson D, Smith C. Better systems, better chances: A review of research and practice for prevention and early intervention. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gann, E. (2010). The effects of therapeutic hip-hop activity groups on perception of self and social supports in at-risk urban adolescents. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The Wright Institute.

- Garst BA, Ozier LW. Enhancing youth outcomes and organizational practices through a camp-based reading program. Journal of Experiential Education. 2015;38(4):324–338. doi: 10.1177/1053825915578914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geipel J, Hillecke T, Koenig J, Kaess M, Resch F. Music-based interventions to reduce internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2018;225:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherardi SA, Whittlesey-Jerome WK. Role integration through the practice of social work with schools. Children & Schools. 2018;40(1):35–44. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdx028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez T, Hayes BG. Rap music in school counseling based on Don Elligan's rap therapy. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health. 2009;4(2):161–172. doi: 10.1080/15401380902945293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulbay S. Exploring the use of hip hop-based music therapy to address trauma in asylum seeker and unaccompanied minor migrant youth. Voices. 2021;21(3):14. [Google Scholar]

- Hakvoort L. Rap music therapy in forensic psychiatry: Emphasis on the musical approach to rap. Music Therapy Perspectives. 2015;33(2):184–192. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miv003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harper PTH, Rhodes WA, Thomas DE, Leary G, Quinton SL. Hip-hop development™ bridging the generational divide for youth development. Journal of Youth Development. 2007;2(2):42–55. doi: 10.5195/jyd.2007.345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey M. “We all come together to learn about music”: A qualitative analysis of a 5-year music program in a juvenile detention facility. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2018;62(13):4046–4066. doi: 10.1177/0306624X18765367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkster B, Sule A. A hip-hop state of mind. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(7):494–495. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A., Phillips, D., Horm, D., & Luk, G. (2020). Parents, teachers, and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A snapshot from Tulsa, OK. Tulsa Seed Study. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@TulsaSEED/parents-teachers-and-distance-learning-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-snapshot-from-tulsa-ok-5b5fdb54ea18.

- Jones, S. M., & Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence base for how we learn: Supporting students' social, emotional, and academic development. Consensus Statements of Evidence from the Council of Distinguished Scientists. Aspen Institute.

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Queen B, Lowry R, Chyen D, Whittle L, Thornton T, Lim C, Bradford D, Yamakawa Y, Leon M, Brener N, Ethier KA. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67(8):1–114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschman KJB, Roberts MC, Shadlow JO, Pelley TJ. An evaluation of hope following a summer camp for inner-city youth. Child & Youth Care Forum. 2010;39(6):385–396. doi: 10.1007/s10566-010-9119-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld M. Surprising new evidence on summer learning loss. Phi Delta Kappan. 2019;101(1):25–29. doi: 10.1177/0031721719871560. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 2. SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lam S. An interdisciplinary course to prepare school professionals to collaborate with families of exceptional children. Multicultural Education. 2005;13(2):38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Leafloor S. Therapeutic outreach through Bboying (break dancing) in Canada's arctic and first nations communities: Social work through hip-hop. In: Hadley S, Yancey G, editors. Therapeutic Uses of Rap and Hip-Hop. Routledge; 2012. pp. 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lenhoff S, Somers C, Tenelshof B, Bender T. The potential for multi-site literacy interventions to reduce summer slide among low-performing students. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]