Structured Abstract

Background:

Polypharmacy is associated with a poor prognosis in the elderly, however, information on the association of polypharmacy with cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is sparse. This study sought to investigate the relationship between polypharmacy and adverse cardiovascular events in patients with HFpEF.

Methods:

Baseline total number of medications was determined in 1,758 patients with HFpEF enrolled in the Americas regions of the TOPCAT trial, by three categories: non-polypharmacy (<5 medications), polypharmacy (5 to 9), and hyper-polypharmacy (≥ 10). We examined the relationship of polypharmacy status with the primary outcome (cardiovascular death, HF hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest), hospitalizations for any reason, and serious adverse events.

Results:

The proportion of patients taking 5 or more medications was 92.5% (inclusive of polypharmacy [38.7%] and hyper-polypharmacy [53.8%]). Over a 2.9-year median follow-up, compared to patients with polypharmacy, hyper-polypharmacy was associated with an increased risk for the primary outcome, hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events in the univariable analysis, but not significantly associated with mortality. After multivariable adjustment for demographic and comorbidities, hyper-polypharmacy remained significantly associated with an increased risk for hospitalization for any reason (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.05–1.41; P=0.009) and any serious adverse events (hazard ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.07–1.42; P=0.005), whereas the primary outcome was no longer statistically significant.

Conclusions:

Hyper-polypharmacy was common and associated with an elevated risk of hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events in HFpEF patients. There were no significant associations between polypharmacy status and mortality.

Keywords: Polypharmacy, Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Prognosis

Introduction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is a growing healthcare problem in the aging population [1, 2]. Comorbidities are common in patients with HFpEF and medications for comorbidity management are prescribed in accordance with practice guidelines accompanied by an increase in the number of medications, whereas there are no definitive standard treatments to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with HFpEF [3, 4]. Polypharmacy is common in older patients and the use of at least 10 medications is particularly notable, representing a condition described in the geriatrics and pharmacology literature as hyper-polypharmacy [5, 6]. Forty percent of community-dwelling adults older than 65 years took 5 or more medications [7]. Older patients are at high risk for medications-related adverse outcomes due to alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics [8, 9]. Polypharmacy is reported to be associated with adverse outcomes including mortality and hospitalizations in a population-based cohort study and in a study of older veterans [10, 11]. The prevalence of taking ≥ 10 medications in 558 older adults aged ≥65 years with adjudicated HF hospitalizations in the US was 55% at discharge [12]. A recent study demonstrated that 74% of HFpEF patients took 10 or more medications [13]. Despite the high burden of medication use among HFpEF patients, the associations between polypharmacy and clinical outcomes in HFpEF is not well known.

We hypothesized that polypharmacy would reflect multimorbidity in HFpEF and be associated with a higher incidence of cardiovascular (CV) events. The objectives of this study were to investigate the prevalence of polypharmacy and hyper-polypharmacy and to clarify the association of polypharmacy with CV and serious adverse events in a large cohort of HFpEF patients enrolled in the TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist) trial.

Methods

Patients and Study Design

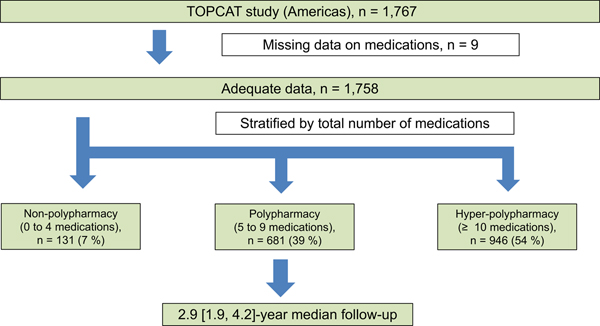

The TOPCAT trial data were obtained through the publicly available National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute BioLINCC data repository. This was a post-hoc analysis of the TOPCAT trial. TOPCAT was a multicenter, international, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial that tested the efficacy and safety of the mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone compared with placebo on CV morbidity and mortality in 3,445 subjects. Details of the study design, baseline characteristics, and main results have been described previously [14–16]. Eligible subjects were at least 50 years old with signs and symptoms of HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 45% (per local reading). Randomization was stratified by the presence of one of the following inclusion criteria: at least one HF hospitalization within the 12 months prior to study screening or, if no qualifying HF hospitalization, a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) ≥ 100 pg/mL or N-terminal pro BNP ≥ 360 pg/mL within the 60 days prior to screening. The study protocol was approved at each participating institutional review board or ethics committee. All study participants provided written informed consent before enrollment. All hospitalizations were adjudicated by a blinded clinical endpoint committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, according to pre-specified criteria. Of 3,445 randomized patients, we excluded patients from Russia/Georgia (n=1,678) because of substantial region variation in population characteristics and outcomes between the Americans region (United States, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina) and Russia/Georgia [17] and missing medication data at baseline (n=9). We assessed a total of 1,758 (99.5%) patients enrolled from the Americas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study design.

TOPCAT study, The Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist study.

Based on prior studies, polypharmacy status was categorized into three groups: non-polypharmacy (0–4 medications), polypharmacy (5–9 medications), and hyper-polypharmacy (≥ 10 medications) captured by electronic case report form at the baseline visit in the TOPCAT study [5, 6, 18, 19]. Over-the-counter medications, vitamins, and mineral supplements administered on a daily basis were included in this study. Medication name and daily dose in diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta-blockers calcium channel blockers, other CV medications (hypertension, dyslipidemia, HF, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and atrial fibrillation), and hypoglycemic agents were obtained via an electronic case report form, while medication name alone was included in non-CV medications. Basically, all information on drug history including over-the-counter was at the discretion of the investigator at each local site. We defined the medications for hypertension, dyslipidemia, HF, coronary artery disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and atrial fibrillation as CV medications. We assessed the number of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) raised in the updated Beers 2019 criteria [20]. Number of comorbidities (range: 0 to 13) was the sum of self-reported medical history collected on the case report form or baseline laboratory findings. Comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidemia, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2), thyroid disease, and bone fracture [15]. The study outcomes were the TOPCAT primary outcome (first occurrence of CV death, HF hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest), first HF hospitalization, CV death, all-cause death, non-CV or unknown death, hospitalization for any reason, hospitalization for CV reason, and hospitalization for a non-CV reason. Safety outcomes included a doubling of the serum creatinine level to a value above the upper limit of the normal range as read at the local laboratory, hyperkalemia (any serum potassium >5.5 mEq/L), hypokalemia (any serum potassium ≤3.5 mEq/L), discontinuation of study drug, suspected hypotension symptom defined as an adverse event related to hypotension with dizziness, faint, syncope, presyncope, or lightheadedness, and any serious adverse events. An adverse event was considered serious for the TOPCAT trial if it met one or more of the following criteria: fatal, life-threatening, requires in-patient hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, congenital anomaly/birth defect, results in permanent impairment/damage of a body function/structure, or requires intervention to prevent impairment of a body function/structure.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Clinical characteristics across polypharmacy categories were compared using linear regression for continuous normally distributed variables, Cuzick’s nonparametric trend tests for continuous non-normally distributed variables, and chi-squared trend tests for categorical variables. Linear regression models were used to estimate the mean numbers of CV and non-CV medications as a function of patient with age expressed using restricted cubic splines. We further quantified the relationship between age (per decade) and total number of medications, CV, non-CV medications using standard linear regression models. Clinical factors associated with hyper-polypharmacy were assessed using backward stepwise regression models (P-value threshold = 0.05) including age, sex, white race, country, heart rate, the total number of comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus status [insulin-treated, not insulin-treated, or no history of diabetes], prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obesity, thyroid disease, and bone fracture), smoking status, self-reported alcohol drinks in the past week, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (overall summary score), LVEF, hemoglobin, and log eGFR. Relationships between continuous variables were assessed using Spearman correlation. Poisson models were used to estimate incidence rates. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to estimate the association between polypharmacy categories and subsequent clinical events and safety outcomes, using variables including the above covariates, randomized treatment assignment (spironolactone vs. placebo), and randomization strata (prior heart failure hospitalization or biomarker criteria). The polypharmacy group (5–9 medications) was the most frequent category and was defined as the reference group for Cox analyses, providing estimated hazard ratio (HR) with 95 % confidence interval (CI). Because polypharmacy definitions were varied, we also conducted sensitivity analyses where patients were classified according to 1) the hyper-polypharmacy group (≥10 medications) vs. non-hyper-polypharmacy group (<10 medications) and 2) quartile of total medications. Given the marked differences in total number of medications by countries, we examined the presence of comorbidities among countries. A two-sided P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.1 (Stata Cor., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

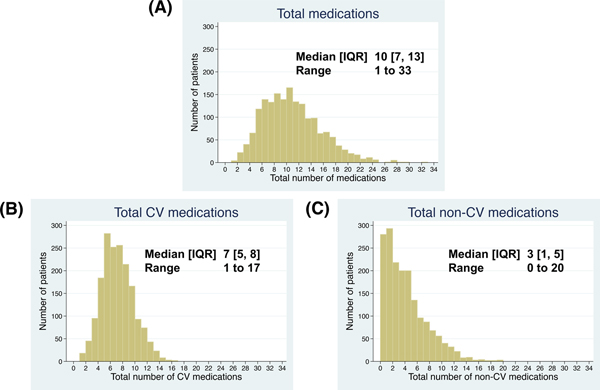

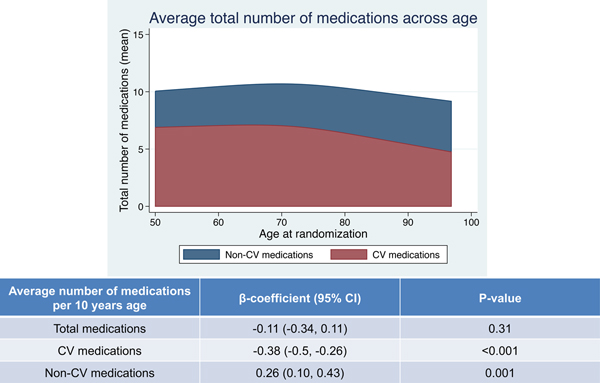

Of the 1,758 patients in this study, the baseline clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 72 ± 10 years, and 50% were female. The distributions of total number of medications, CV, and non-CV medications at baseline are shown in Figure 2. The median [25th, 75th percentile] total number of medications were 10 [7, 13]. Patients were classified into three groups; non-polypharmacy (n=131, 7.5%), polypharmacy (n=681, 38.7%), and hyper-polypharmacy (n= 946, 53.8%) (Figure 1). Patients in the hyper-polypharmacy group were more likely to be male, have higher body mass index, worse NYHA functional class, higher frailty score (indicating greater frailty), and lower Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire scores (indicating impaired quality of life), and had lower hemoglobin and eGFR. The prevalence of hyper-polypharmacy was about 60% in the US and Canada, whereas less than 10% of patients from Brazil and Argentina were categorized into the hyper-polypharmacy group. Comorbidities were more common in the hyper-polypharmacy group. Figure 3 shows the mean number of medications, sorted by CV medications and non-CV medications as a function of patient age. There were no significant associations between total number of medications and age (P=0.31), although older patients had significantly fewer CV medications and significantly more non-CV medications (P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively). Hyper-polypharmacy had a significant association with total number of comorbidities along with covariates found to be significant in Table 2. There were modest correlations between the number of comorbidities and the total number of medications and CV medications (R=+0.47, P<0.001 and R=+0.52, P<0.001, respectively), whereas non-CV medications were a weak but significant correlation (R=+0.26, P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients according to total number of medications

| Non-polypharmacy (<5 medications) (n = 131) | Polypharmacy (5 to 9 medications) (n = 681) | Hyper-polypharmacy (≥ 10 medications) (n = 946) | P-value (for trend) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Total number of medications (range; 1 to 33 medications) |

3 [3, 4] | 7 [6, 8] | 13 [11, 16] | - |

| Total number of cardiovascular medications (range; 1 to 17 medications) |

3 [2, 4] | 5 [5, 6] | 8 [7, 10] | <0.001 |

| Total number of non-cardiovascular medications (range; 0 to 20 medications) |

0 [0, 1] | 1 [1, 3] | 5 [3, 8] | <0.001 |

| Age | 70 ± 11 | 72 ± 10 | 71 ± 10 | 0.85 |

| Age ≥ 65 yr, n (%) | 84 (64.1) | 514 (75.5) | 670 (70.8) | 0.88 |

| Age ≥ 75 yr, n (%) | 52 (39.7) | 299 (43.9) | 366 (38.7) | 0.16 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 72 (55.0) | 355 (52.1) | 450 (47.6) | 0.031 |

| White, n (%) | 99 (75.6) | 523 (76.8) | 753 (79.6) | 0.13 |

| Country, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| USA (n=1148/1152) | 35 (26.7) | 384 (56.4) | 729 (77.1) | |

| Canada (n=326/326) | 12 (9.2) | 115 (16.9) | 199 (21.0) | |

| Brazil (n=164/167) | 40 (30.5) | 109 (16.0) | 15 (1.6) | |

| Argentina (n=120/123) | 44 (33.6) | 73 (10.7) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 72 ± 10 | 69 ± 12 | 69 ± 11 | 0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128 ± 14 | 127 ± 15 | 128 ± 16 | 0.88 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 31.0 ± 7.6 | 32.8 ± 7.9 | 35.1 ± 8.7 | <0.001 |

| NYHA functional class (III or IV), n (%) | 27 (20.6) | 200 (29.4) | 391 (41.5) | <0.001 |

| Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, overall summary score | 64 [42, 79] | 64 [41, 81] | 56 [38, 74] | <0.001 |

| Prior HF hospitalization, n (%) | 69 (52.7) | 396 (58.1) | 571 (60.4) | 0.09 |

| Comorbidities and lifestyle factors | ||||

| Total number of comorbidities (range; 0 to 13 comorbidities) | 3 [2, 4] | 4 [3, 5] | 5 [4, 6] | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 105 (80.2) | 605 (88.8) | 873 (92.4) | <0.001 |

| Resistant hypertension, n (%) | 14 (10.7) | 212 (31.1) | 458 (48.4) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 52 (39.7) | 424 (62.3) | 772 (81.7) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 23 (17.6) | 218 (32.0) | 546 (57.8) | <0.001 |

| Insulin-treated, n (%) | 7 (5.3) | 80 (11.7) | 291 (30.8) | <0.001 |

| Prior myocardial infarction, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 104 (15.3) | 249 (26.3) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 2 (1.5) | 48 (7.0) | 108 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 4 (3.1) | 56 (8.2) | 147 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 29 (22.1) | 296 (43.5) | 417 (44.1) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 4 (3.1) | 89 (13.1) | 198 (21.0) | <0.001 |

| Asthma, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 44 (6.5) | 145 (15.3) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 43 (32.8) | 299 (43.9) | 510 (53.9) | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), n (%) | 69 (52.7) | 395 (58.5) | 667 (70.6) | <0.001 |

| Thyroid disease, n (%) | 7 (5.3) | 103 (15.1) | 222 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Bone fracture, n (%) | 7 (5.3) | 93 (13.7) | 164 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| (Basal skin) cancer, n (%) | 1 (0.8) | 24 (3.5) | 44 (4.7) | 0.032 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 13 (9.9) | 48 (7.0) | 56 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol drinks in the past week, n (%) | 0.24 | |||

| 0 | 99 (75.6) | 484 (71.2) | 715 (75.8) | |

| 1 – 4 | 25 (19.1) | 138 (20.3) | 158 (16.8) | |

| ≥ 5 | 7 (5.3) | 58 (8.5) | 70 (7.4) | |

| Activity level (MET-min/week) | 30 [0, 180] | 60 [0, 240] | 70 [0, 240] | 0.016 |

| Cooking salt score* | 4.0 [0.0, 7.0] | 3.0 [0.0, 4.0] | 0.0 [0.0, 4.0] | <0.001 |

| Home meals, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Almost none | 9 (6.9) | 44 (6.5) | 61 (6.5) | |

| 25% | 4 (3.1) | 35 (5.2) | 59 (6.3) | |

| 50% | 2 (1.5) | 56 (8.3) | 110 (11.8) | |

| 75% | 15 (11.5) | 87 (2.9) | 168 (18.0) | |

| Almost all | 101 (77.1) | 455 (67.2) | 536 (57.4) | |

| Live alone, n (%) | 28 (21.4) | 195 (28.8) | 277 (29.3) | 0.15 |

| Frailty index | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.10 | 0.40 ± 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Medications | ||||

| Assignment to spironolactone, n (%) | 64 (48.9) | 344 (50.5) | 474 (50.1) | 0.93 |

| ACE-inhibitors, n (%) | 59 (45.0) | 333 (48.9) | 497 (52.5) | 0.05 |

| ARBs, n (%) | 34 (26.0) | 198 (29.1) | 319 (33.7) | 0.016 |

| ACE-inhibitors/ARBs, n (%) | 93 (71.0) | 520 (76.4) | 780 (82.5) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 67 (51.1) | 516 (75.8) | 803 (84.9) | <0.001 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 25 (19.1) | 226 (33.2) | 430 (45.5) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 84 (64.1) | 603 (88.5) | 884 (93.4) | <0.001 |

| Alpha-1 blockers | 2 (1.5) | 39 (5.7) | 117 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| Other antihypertensive drugs, n (%) | 3 (2.3) | 68 (10.0) | 223 (23.6) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 37 (28.2) | 341 (50.1) | 648 (68.5) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 15 (11.5) | 229 (33.6) | 348 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| Long-acting nitrate, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 50 (7.3) | 255 (27.0) | <0.001 |

| Statins, n (%) | 20 (15.3) | 371 (54.5) | 757 (80.0) | <0.001 |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 6 (4.6) | 45 (6.6) | 27 (2.9) | 0.005 |

| Digitalis, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 77 (11.3) | 96 (10.1) | 0.29 |

| Hypoglycemic agents, n (%) | 16 (12.2) | 190 (27.9) | 513 (54.2) | <0.001 |

| Proton pump inhibitors, n (%) | 7 (5.3) | 104 (15.3) | 96 (10.1) | 0.29 |

| NSAIDs | 0 (0.0) | 24 (3.5) | 67 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Barbiturate, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 8 (0.8) | 0.09 |

| SSRI/SNRI, n (%) | 5 (3.8) | 43 (6.3) | 108 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Total potentially inappropriate medications based on 2019 Updated Beers Criteria, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0 | 118 (90.1) | 521 (76.5) | 610 (64.5) | |

| 1 | 13 (9.9) | 149 (21.9) | 280 (29.6) | |

| ≥ 2 | 0 (0.0) | 11 (1.6) | 56 (5.9) | |

| Laboratory and echocardiography data | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5 ± 1.5 | 13.1 ± 1.7 | 12.6 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 140 ± 3 | 140 ± 3 | 140 ± 3 | 0.50 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0.003 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2 surface area) | 72.1 [57.0, 86.8] | 63.6 [51.1, 78.3] | 58.1 [47.6, 72.8] | <0.001 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 240 [140, 500] (n = 41) | 269 [153, 435] (n = 230) | 250 [150, 443] (n = 426) | 0.83 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 725 [484, 1790] (n = 33) | 960 [499, 2188] (n = 150) | 972 [632, 1820] (n = 173) | 0.18 |

| LVEF (%) | 59.3 ± 7.9 | 58.2 ± 8.1 | 58.0 ± 7.5 | 0.15 |

| LVEF ≥50%, n (%) | 118 (90.1) | 599 (88.0) | 846 (89.4) | 0.68 |

Values are presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [25th, 75th percentiles].

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SSRI/SNRI; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

Cooking salt score = sum of salt added to staple foods, soup, meat, and vegetables during cooking. Range is 0–12 (None = 0, 1/8 tsp = 1, 1/4 tsp = 2, 1/2 tsp or more = 3 for each food category)

Figure 2. Distribution of total number of (A) medications, (B) CV medications, and (C) non-CV medications.

CV, cardiovascular; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 3. Average total number of medications across age.

CV, cardiovascular.

Table 2.

Predictors of hyper-polypharmacy assessed by multivariable logistic regression models (n = 1693)

| Variables | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |Z|-score | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Number of comorbidities, per 1 increase | 1.58 (1.46–1.70) | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Country, USA (reference) | |||

| Canada | 0.82 (0.61–1.09) | 1.4 | 0.17 |

| Brazil | 0.07 (0.04–0.13) | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Argentina | 0.02 (0.01–0.07) | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, per 1g/dL decrease | 1.16 (1.08–1.25) | 4.0 | <0.001 |

| KCCQ (overall summary) score, per 5 unit decrease | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 2.9 | 0.004 |

| Race (White) | 1.50 (1.13–2.00) | 2.8 | 0.006 |

| Male sex | 1.33 (1.02–1.65) | 2.2 | 0.031 |

Variables in multivariable regression models were selected by backward stepwise logistic regression models using cut-off p-value of 0.05. Initial covariates included age, sex, race (white vs. non-white), country, the total number of comorbidities (range; 0 to 13), smoking status, alcohol drinks in the past week, New York Heart Association functional class, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (overall summary score), left ventricular ejection fraction, hemoglobin, and log eGFR. Z-score was measured in terms of standard deviations from the mean (expressed per 1 standard deviation

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; OR, odds ratio.

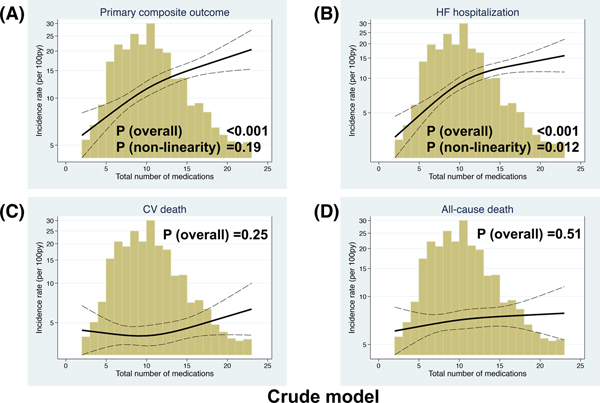

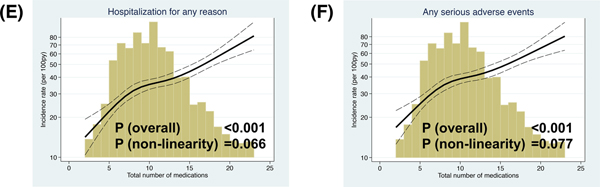

During the median 2.9 year follow up period (interquartile range 1.9–4.2 years), the primary outcome, HF hospitalization, CV death, and all-cause death were observed in 521 patients (incidence rate: 11.5 per 100 patient-years [py]), 399 patients (8.8 per 100 py), 223 patients (4.3 per 100 py), and 383 patients (7.1 per 100 py) (Table 3). We related the total number of medications as a continuous variable with the primary outcome, its components, hospitalization for any reason, and serious adverse events. There was a significant linear association between the total number of medications and higher incidence of the primary outcome, hospitalization for any reason, and serious adverse events and non-linear association with HF hospitalization in the crude model. The associations of total number of medications with the primary outcome or hospitalization for HF were no longer statistically significant, while there remained a significant linear relationship between the total number of medications and hospitalization for any reason and serious adverse events after adjusted for the factors associated with hyper-polypharmacy (i.e. sex, race, country, the number of comorbidities, hemoglobin, and KCCQ score). Total number of medications was not significantly associated with CV death and all-cause death (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards analyses of clinical outcomes by total number of medications

| Polypharmacy categories | Overall (n = 1758) | Non-polypharmacy (< 5 medications) (n = 131) HR (95% CI) P-value (vs. Poly-) | Polypharmacy (5 to 9 medications) (n = 681) Reference | Hyper-polypharmacy (≥ 10 medications) (n = 946) HR (95% CI) P-value (vs. Poly-) | Medication, 1 per increase HR (95% CI) | Interaction: (Number of medications) * (Treatment) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Primary outcome Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(521 events) 11.5 (10.5–12.5) |

(22 events) 6.3 (4.2–9.6) |

(164 events) 9.0 (7.8–10.5) |

(335 events) 14.1 (12.7–15.7) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.70 (0.45–1.09) P = 0.11 |

Reference | 1.55 (1.29–1.87) P < 0.001 |

1.06 (1.04–1.08) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.98 (0.61–1.57) P = 0.93 |

Reference | 1.20 (0.97–1.49) P = 0.091 |

1.02 (0.99–1.04) P = 0.17 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.69 (0.43–1.62) | 0.73 (0.54–0.99) | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | P = 0.51 | ||

|

Hospitalization for HF Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(399 events) 8.8 (7.9–9.7) |

(8 events) 2.3 (1.1–4.6) |

(122 events) 6.7 (5.6–8.0) |

(69 events) 11.3 (10.0–12.7) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.34 (0.17–0.70) P = 0.003 |

Reference | 1.67 (1.35–2.07) P < 0.001 |

1.07 (1.05–1.09) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.58 (0.28–1.22) P = 0.15 |

Reference | 1.18 (0.93–1.51) P = 0.18 |

1.01 (0.99–1.04) P = 0.29 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.14 (0.02–1.18) | 0.69 (0.48–0.98) | 0.92 (0.73–1.17) | P = 0.20 | ||

|

CV death Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(n = 223) 4.3 (3.7–4.9) |

(n = 16) 4.5 (2.8–7.3) |

(n = 77) 3.8 (3.1–4.8) |

(n = 130) 4.6 (3.8–5.4) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

1.20 (0.70–2.06) P = 0.50 |

Reference | 1.18 (0.89–1.56) P = 0.26 |

1.02 (0.99–1.05) P = 0.21 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

1.26 (0.70–2.27) P = 0.45 |

Reference | 1.08 (0.77–1.51) P = 0.66 |

1.01 (0.97–1.04) P = 0.70 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

1.01 (0.38–2.70) | 0.69 (0.44–1.08) | 0.76 (0.54–1.08) | P = 0.54 | ||

|

All-cause death Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(383 events) 7.1 (6.4–7.8) |

(27 events) 7.4 (5.1–10.9) |

(132 events) 6.3 (5.3–7.5) |

(224 events) 7.5 (6.6–8.6) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

1.20 (0.79–1.82) P = 0.38 |

Reference | 1.18 (0.95–1.48) P = 0.13 |

1.01 (0.99–1.03) P = 0.31 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

1.43 (0.91–2.25) P = 0.13 |

Reference | 1.05 (0.82–1.36) P = 0.68 |

0.99 (0.96–1.02) P = 0.47 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.97 (0.46–2.07) | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | 0.92 (0.71–1.20) | P = 0.92 | ||

|

Non-CV or unknown death Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(160 events) 3.0 (2.5–3.4) |

(11 events) 3.0 (1.7–5.5) |

(55 events) 2.6 (2.0–3.4) |

(94 events) 3.2 (2.6–3.9) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

1.17 (0.61–2.24) P = 0.63 |

Reference | 1.19 (0.85–1.65) P = 0.32 |

1.00 (0.97–1.04) P = 0.85 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

1.69 (0.82–3.49) P = 0.15 |

Reference | 1.02 (0.69–1.50) P = 0.94 |

0.97 (0.93–1.01) P = 0.17 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.89 (0.27–2.07) | 0.74 (0.43–1.25) | 1.22 (0.81–1.82) | P = 0.46 | ||

|

Hospitalization for any reason Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(1055 events) 34.2 (32.2–36.4) |

(46 events) 16.0 (12.0–21.3) |

(369 events) 28.7 (25.9–31.8) |

(640 events) 42.5 (39.3–45.9) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1756) |

0.58 (0.42–0.78) P < 0.001 |

Reference | 1.44 (1.27–1.64) P < 0.001 |

1.07 (1.05–1.09) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1689) |

0.82 (0.59–1.14) P = 0.24 |

Reference | 1.22 (1.05–1.41) P = 0.009 |

1.04 (1.02–1.05) P < 0.001 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.64 (0.35–1.16) | 0.90 (0.73–1.10) | 1.00 (0.85–1.16) | P = 0.52 | ||

|

Hospitalization for CV reason Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(689 events) 17.7 (16.4–19.0) |

(28 events) 8.7 (6.0–12.6) |

(233 events) 14.7 (12.9–16.7) |

(428 events) 21.5 (19.5–23.6) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.60 (0.40–0.89) P < 0.001 |

Reference | 1.44 (1.23–1.69) P < 0.001 |

1.05 (1.04–1.07) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.83 (0.55–1.27) P = 0.40 |

Reference | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) P = 0.11 |

1.02 (1.00–1.04) P = 0.069 |

||

| Treatment effect, Unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.89 (0.42–1.86) | 0.93 (0.72–1.21) | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | P = 0.79 | ||

|

Hospitalization for non-CV reason Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(756 events) 20.1 (18.7–21.6) |

(30 events) 9.6 (6.7–13.7) |

(255 events) 16.6 (14.7–18.8) |

(471 events) 24.5 (22.4–26.8) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.55 (0.37–0.80) P < 0.001 |

Reference | 1.53 (1.32–1.78) P < 0.001 |

1.06 (1.05–1.08) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.81 (0.54–1.21) P = 0.30 |

Reference | 1.24 (1.04–1.48) P = 0.016 |

1.04 (1.02–1.06) P < 0.001 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

|

0.57 (0.27–1.21) | 1.07 (0.74–1.37) | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | P = 0.93 | |

|

Doubling of the serum creatinine Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(259 events) 5.4 (4.8–6.1) |

(8 events) 2.3 (1.2–4.7) |

(81 events) 4.4 (3.5–5.4) |

(170 events) 6.6 (5.7–7.7) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.54 (0.26–1.11) P = 0.093 |

Reference | 1.53 (1.17–1.99) P = 0.002 |

1.07 (1.04–1.10) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.62 (0.29–1.33) P = 0.22 |

Reference | 1.22 (0.90–1.65) P = 0.21 |

1.04 (1.00–1.07) P = 0.030 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

1.06 (0.26–4.23) | 2.17 (1.36–3.49) | 1.44 (1.06–1.95) | P = 0.45 | ||

|

Hyperkalemia ≥5.5 mmol/L Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(280 events) 6.1 (5.4–6.9) |

(12 events) 3.6 (2.0–6.3) |

(119 events) 6.7 (5.6–8.1) |

(149 events) 6.0 (5.1–7.0) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

0.53 (0.29–0.95) P = 0.035 |

Reference | 0.90 (0.71–1.14) P = 0.38 |

1.01 (0.99–1.04) P = 0.24 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

0.60 (0.32–1.13) P = 0.11 |

Reference | 0.69 (0.52–0.92) P = 0.012 |

0.98 (0.95–1.02) P = 0.28 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

5.51 (1.21–25.14) | 2.69 (1.80–4.02) | 3.60 (2.47–5.25) | P = 0.73 | ||

|

Hypokalemia <3.5 mmol/L Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(308 events) 6.8 (6.1–7.6) |

(20 events) 6.2 (4.0–9.7) |

(99 events) 5.6 (4.6–6.8) |

(189 events) 7.8 (6.8–9.0) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1758) |

1.08 (0.67–1.75) P = 0.74 |

Reference | 1.40 (1.10–1.79) P = 0.006 |

1.03 (1.00–1.05) P = 0.033 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1691) |

1.00 (0.59–1.68) P = 0.99 |

Reference | 1.52 (1.14–2.01) P = 0.004 |

1.04 (1.01–1.07) P = 0.018 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.23 (0.08–0.68) | 0.34 (0.22–0.53) | 0.52 (0.39–0.70) | P = 0.31 | ||

|

Study drug discontinuation Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(777 events) 21.1 (19.7–22.7) |

(39 events) 13.7 (10.0–18.7) |

(279 events) 18.8 (16.7–21.1) |

(459 events) 24.1 (22.0–26.4) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1750) |

0.74 (0.53–1.03) P = 0.075 |

Reference | 1.27 (1.09–1.47) P = 0.002 |

1.03 (1.02–1.05) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1686) |

0.97 (0.67–1.40) P = 0.85 |

Reference | 1.07 (0.90–1.26) P = 0.46 |

1.00 (0.98–1.02) P = 0.72 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

1.10 (0.59–2.06) | 1.08 (0.85–1.36) | 1.32 (1.10–1.58) | P = 0.32 | ||

|

Suspected hypotension symptom Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(321 events) 36.4 (32.6–40.6) |

(15 events) 21.5 (13.0–35.7) |

(102 events) 28.0 (23.1–34.0) |

(204 events) 45.4 (39.6–52.1) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1423) |

0.81 (0.47–1.39) P = 0.44 |

Reference | 1.47 (1.16–1.87) P < 0.001 |

1.07 (1.05–1.11) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1373) |

1.23 (0.68–2.23) P = 0.50 |

Reference | 1.19 (0.91–1.56) P = 0.20 |

1.05 (1.02–1.08) P = 0.001 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

1.81 (0.62–5.27) | 1.45 (0.98–2.15) | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) | P = 0.14 | ||

|

Any serious adverse event Event rate (per 100 patient-years) |

(1129 events) 37.4 (35.3–39.7) |

(53 events) 18.4 (14.0–24.1) |

(402 events) 32.0 (29.0–35.3) |

(674 events) 45.7 (42.4–49.3) |

||

| Unadjusted (n = 1756) |

0.60 (0.45–0.79) P < 0.001 |

Reference | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) P < 0.001 |

1.06 (1.04–1.07) P < 0.001 |

||

| Adjusted (n = 1689) |

0.80 (0.59–1.09) P = 0.15 |

Reference | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) P = 0.005 |

1.03 (1.02–1.05) P < 0.001 |

||

| Treatment effect, unadjusted HR (95%CI) (Spironolactone vs. Placebo) |

0.64 (0.37–1.11) | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) | P = 0.52 |

The primary outcome was the composite of cardiovascular death, hospitalization for worsening heart failure, or resuscitated sudden death.

Multivariable model was adjusted for randomized treatment assignment, age, sex, race (white vs. non-white), country, heart rate, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus status (insulin-treated, not insulin-treated, or no history of diabetes), prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obesity, thyroid disease, bone fracture, smoking status, alcohol drinks in the past week, New York Heart Association functional class, randomization strata (prior heart failure hospitalization or biomarker criteria), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (overall summary score), left ventricular ejection fraction, hemoglobin, and log eGFR.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 4. Association between total number of medications and incident rate of (A) the primary composite outcome, (B) HF hospitalization, (C) CV death, (D) all-cause death, (E) hospitalization for any reason, and (F) serious adverse events in the crude model.

Depicting the incidence rate of each outcome (events per 100 person-years) on the left y-axis (log) and total number of medications on the x-axis. The solid black curve depicts the incidence, with 95% confidence intervals of the estimates. The Primary composite outcome was CV death, HF hospitalization, or aborted cardiac arrest. Poisson models were used to estimate the incidence rates. Histograms show the population distribution of total number of medications.

CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure.

Table 3 presents univariable and multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards analyses for all outcomes, categorized by polypharmacy status. In the crude model, hyper-polypharmacy compared with polypharmacy was associated with a higher risk of the primary outcome, hospitalization for HF, hospitalization for any reason, hospitalization for CV reason, hospitalization for non-CV reason, doubling of the serum creatinine, hypokalemia, discontinuation of the study drug, symptoms of hypotension, and any serious adverse event, whereas there were no significant associations with CV death, all-cause death, and non-CV or unknown death. After multivariable adjustment for clinical characteristics, hyper-polypharmacy remained significantly associated with an increased risk for hospitalization for any reason (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.41), hospitalization for non-CV reason (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04–1.48), hypokalemia (HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.14–2.01), and any serious adverse events (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.07–1.42). There were no significant interactions between spironolactone treatment and total number of medications for any outcomes (all, P>0.1) (Table 3 and Supplemental Table 1). We assessed the association of polypharmacy status (using only 1 threshold; patients with hyper-polypharmacy vs. those without hyper-polypharmacy) with clinical outcomes. The results fundamentally showed the same results (Supplemental Table 2 and 3). In sensitivity analyses with the classification according to quartile of medications, patients in the highest total number of medications (≥14 medications, n=421) were more likely to be male, have higher body mass index, worse HF severity, lower hemoglobin, and lower eGFR (Supplemental Table 4). The quartile with the highest number of medications relative to the lowest quartile (<7 medications, n=521) had a higher incidence of hospitalization for any reason (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.14–1.74), hospitalization for non-CV reason (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.15–1.91), doubling serum creatinine (HR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.04–2.52), hypokalemia (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.07–2.37), and any serious adverse events (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11–1.67) (Supplemental Table 5). There were no significant interactions between LVEF categorized analysis (LVEF<50% [n=195] vs. LVEF≥50% [n=1563]) or continuous LVEF and total number of medications for any outcomes (all, P>0.1). Patients from the US and Canada had more comorbidities, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and obesity and had less prior HF hospitalization than those from Brazil and Argentina (Supplemental Table 6). Despite these differences, there were no significant interactions between countries and total number of medications for any outcomes (P for interaction >0.05 for all analyses). We assessed whether a certain drug such as NSAIDs, amiodaron, digitalis, or proton pump inhibitors was associated with an increased risk of adverse outcomes. We observed that each drug and the total number of PIMs did not show worse outcomes after adjusted for demographic and comorbidities. We assessed subjects without PIMs (n=1247, 70%) to investigate whether total number of medications was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for any reasons and serious adverse events. Total number of medications remained significantly associated with an increased incidence of hospitalization for any reason (hazard ratio 1 per increase of medication, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06; P=0.001) and serious adverse events (hazard ratio 1 per increase of medication, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.05–1.08; P<0.001) in the multivariable model.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the TOPCAT trial restricted to the Americas, participants took multiple medications and more than 90% met the commonly accepted definition of polypharmacy (≥5 medications daily) and 54% met the definition for hyper-polypharmacy (≥10 medications). We found that hyper-polypharmacy was related to multimorbidity and a higher risk of the primary composite CV outcome, HF hospitalization, hospitalization for any reason, and any serious adverse events. However, the association of polypharmacy categories with the incidence of the primary outcome and HF hospitalization did not remain significant after adjustment for potential confounders, whereas hospitalization for any reason and serious adverse events remained significant.

In our study, the prevalence of polypharmacy and hyper-polypharmacy was respectively 93% and 54%, which was substantially higher compared with previous reports in patients with HF [19, 21]. The prevalence of polypharmacy varies depending on the definition, accuracy of medication lists, and the study population, particularly comorbidities. Prior studies did not include over-the-counter medications or vitamins, which may contribute to differences observed from our study. As some vitamins and mineral supplements have pharmacological activity that can cause clinically significant interactions when they are taken along with prescribed medications [22], it is important to assess the total medication burden that includes prescription, over-the-counter, and complementary and alternative medications, as done in the present study. Indeed, a recent single-center study demonstrated that 74% of HFpEF patients took ≥10 medications including over-the-counter medications [13]. Prior research reported that a higher number of total medications more frequently prescribed in the elderly compared with younger age groups [23]. Our study did not show differences in the total number of medications across age in those enrolled. The older subjects were prescribed fewer CV medications and more non-CV medications. Unlu et al. described that the number of non-CV medications increased more rapidly than the number of CV medications among older patients hospitalized for HF [12]. In contrast, the younger patients with HFpEF were more frequently obese men, had more diabetes mellitus and prior myocardial infarction, and died more often of CV causes, whereas the older participants with HFpEF more often died of non-CV reasons [24]. Our findings would reflect the heterogeneity of HFpEF in terms of medication types across age.

We assessed the association of multiple factors with hyper-polypharmacy and found that hyper-polypharmacy was strongly associated with the number of comorbidities. Our finding indicated hyper-polypharmacy reflected comorbidity burdens, consistent with a previous report in HF patients [19]. The reasons for polypharmacy among HF patients can be multifactorial, and may be linked to treatment of concomitant comorbidities in an aging population [22]. The geographical variability on polypharmacy categories is consistent with prior surveys among four countries. In previous studies, the prevalence of polypharmacy among the older adults was 30–41% in the US and Canada and 18–21% in Brazil and Argentina, suggesting that number of medications might be affected by the prevalence of comorbidities, socioeconomic status, and type of health insurance [21, 23, 25, 26]. Although we were unable to examine socioeconomic status and health insurance, our study showed that more patients from the US and Canada had comorbidities, such as dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and obesity compared with those from Brazil and Argentina, which may partially account for the variation in polypharmacy among countries. Local and global guideline for underlying diseases and practice variation may also be a potential contributor.

The present study demonstrated that hyper-polypharmacy was associated with an elevated risk of hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events in HFpEF patients. Although previous studies showed that multiple medications were associated with a higher incidence of mortality in the elderly population and HF patients, the impact of polypharmacy in a large cohort of HFpEF patients is sparse [11, 27]. In this study, we evaluated the association of hyper-polypharmacy with a variety of clinical outcomes in a multicenter, international trial. There are several potential explanations for the relationship between hyper-polypharmacy and adverse events in HFpEF patients. First, patients with hyper-polypharmacy were more likely to have multiple comorbidities and reflect an advanced phase of systemic illness. Patients with multimorbidity represent a state of increased vulnerability resulting from alterations in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics due to advanced age [8, 9]. Indeed, patients with hyper-polypharmacy was associated with greater frailty, despite the number of medications was one of domains for a frailty score. Frailty is associated with a higher risk of impaired physical functioning and adverse outcomes in HFpEF, suggesting geriatric and multi-domain management approach is possibly more appropriate than narrow medical domain approach [28–30]. Second, drug-disease interactions, in which a medication worsens a disease condition, are common in older patients; for example, potassium disturbances can be attributed to several medications in patients with chronic kidney disease [10, 31]. Third, polypharmacy is associated with a higher risk of drug-drug interactions, which have been reported to increase with the number of medications [32]. Fourth, polypharmacy has been associated with poor medication adherence, an especially relevant problem in HF patients since poor medication adherence was associated with a higher incidence of adverse events [27, 33]. Poor adherence may undermine the efficacy of pharmacological treatment. The relationship between hyper-polypharmacy and some outcomes were attenuated after adjustment for clinical risk factors. Although the reasons for different results were unclear, a potential contributor was that hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events were nonspecific events, indicated a larger disease burden, and remained the prognostic value of hyper-polypharmacy compared with the other outcomes.

Since there are limited therapeutic options for the treatment of HFpEF, identifying modifiable factors for adverse events is crucial [2]. Some studies have shown that various interventions, such as medication reviews, geriatrician’s services, computerized support system, and multidisciplinary teams, may be beneficial to reduce inappropriate prescribing and serious adverse events in the elderly [34]. Computerized support system intervention, developed by an interdisciplinary expert, decreases drug-drug interactions and subsequent adverse events, highlighting the need for multidisciplinary care management. Medication review would be an important first step in optimizing prescribing practices, which identifying and eliminating drug with minimal benefit and risk for harm. Pharmacist-based interventions demonstrated some promise to reduce potential drug-related problems in the elderly [35]. Our exploratory findings highlight possible areas for future prospectively studies to evaluate the role of multidisciplinary interventions including pharmacist-based medication reviews with taking account for risk-benefit ratio of drugs on a variety of outcomes ae well as quality of life in HFpEF. Indeed, current HF guidelines have advocated for multidisciplinary HF care management to reduce the risk of adverse events [36]. The recent data on polypharmacy in HFpEF demonstrated that hyper-polypharmacy was related to multimorbidity and its prevalence was rising over time [12, 13]. Our study now extends these findings by showing the association between hyper-polypharmacy and adverse outcomes, suggesting the assessment of polypharmacy categories may be useful for identifying HFpEF patients at elevated risk for a future serious adverse event. In the trial of intensified medical treatment according to NT-proBNP vs. symptoms alone in the elderly with HF (TIME-CHF), opposite effects of NT-proBNP-guided management were observed in HFpEF than HFrEF (significant interaction) and patients with HFpEF had worse outcome in the NT-proBNP-guided group, suggesting the contribution of comorbid and demographic aspects to clinical outcomes was greater than cardiac aspects in HFpEF [37, 38]. Our exploratory findings raise the possibility of importance in prescribing review to avoid unnecessary medications and to optimize the prescribing practice of HF guidelines. Further research is warranted to evaluate whether these interventions can prevent serious adverse events in HFpEF.

Our study should be considered in the context of its limitations. This was not a pre-specified post-hoc analysis and unmeasured confounding factors might have affected the results regardless of multivariable adjustment; thus our results should be considered hypothesis-generating study. The data precision of non-CV medications, over-the-counter medications, and co-morbidities may be lower compared with CV-related medications and co-morbidities since the TOPCAT trial was designed for HF patients and primarily focused on CV events. There would be a possibility that some patients did not realize that over-the-counter drugs and vitamins were medications since all patients were not explicitly asked for a list of these substances. Furthermore, the influence of geographical variation on prevalence of hyper-polypharmacy was seen in our study, suggesting that total number of medications might be affected by health care service, socioeconomic status, transportation and access to medication, but we did not have this information in the TOPCAT trial. Second, polypharmacy category was only evaluated at baseline and we did not assess change in the total number of medications or medication pattern during the follow-up period. Third, we were unable to evaluate several comprehensive comorbidity indices and adjust all relevant confounders due to incomplete data on medication type and medical history. Fourth, this study is not designed to identify the causality between hyper-polypharmacy and a higher incidence of hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events. Fifth, our exploratory findings may not be generalizable to community-based HFpEF population since clinical trials impose inevitably specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Despite these limitations, hyper-polypharmacy remained consistently associated with hospitalization for any reason and serious adverse events after adjustment for potential confounders regardless of categorical and continuous analyses. We will need to be confirmed prospectively whether our exploratory findings are relevant in HF with reduced ejection fraction. Multiple drug classes following guideline-directed medical therapies for HF with reduced ejection fraction was associated with improvement in CV outcomes and mortality, although a previous paper demonstrated that an increasing number of noncardiac comorbidities was associated with a higher risk for hospitalization for any reason irrespective of HF subtype. Further studies are needed to determine whether hyper-polypharmacy per se is the proximate cause rather than reflecting a marker of disease severity and clarify the causality relationship between total number of medications and outcomes in HFpEF patients.

In conclusion, hyper-polypharmacy was common and reflected multimorbidity in HFpEF patients from the Americas region of the TOPCAT trial. Hyper-polypharmacy was associated with an elevated risk of hospitalization for any reason and any serious adverse events. These findings highlight possible areas for future prospective studies to evaluate the role of multidisciplinary interventions including medication reviews on a variety of outcomes in HFpEF patients.

Supplementary Material

What is new?

There is a paucity of data on the association of polypharmacy with clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

We observed a strong association of polypharmacy with comorbidities and the total number of medications was related to an elevated risk of hospitalization for any reason and serious adverse outcome, while there were no significant associations between polypharmacy status and mortality in patients with HFpEF

What are the clinical implications?

Medication reviews including the total number of medications would allow clinicians to identify HFpEF patients at elevated risk for future all-cause hospitalizations and serious adverse events.

Our post-hoc exploratory findings raise the possibility of importance in prescribing review to avoid unnecessary medications and to optimize the prescribing practice of HF guidelines and support the basis for future prospective studies to assess the role of multidisciplinary interventions including medication reviews on clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants (patients, caregivers, and staff) of the TOPCAT trial for providing invaluable contribution.

Disclosures

Dr. Minamisawa has received support from the Japanese Circulation Society, the Japanese Society of Echocardiography, and the Uehara Memorial Foundation Overseas Research Fellowship. Dr. Hegde has received support through her institution from Myokardia.

Dr. Amil M. Shah has received research support from Novartis and Philips Ultrasound through Brigham and Women’s Hospital and has consulted for Philips Ultrasound.

Dr. Desai has received research grants from Abbott, Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Novartis as well as consulting fees from Abbott, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Cytokinetics, DalCor Pharma, Lupin Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Relypsa, Regeneron, and Sun Pharma.

Dr. Lewis has received funding from Novartis (research support), Merck, and Dal-Cor (consulting agreement).

Dr. Fang has served on steering committees for Novartis, Amgen, AstraZeneca, and J & J.

Dr. Anand has received personal fees and honoraria for serving as a steering committee member for the Genetic-AF trial, personal fees and honoraria for serving as a steering committee member for the Galactic-HF trial from Amgen, personal fees and honoraria for serving as a steering committee member for the Emperor trial from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and honoraria for serving as chair of the data and safety monitoring board for the Manage-AF trial from Boston Scientific, personal fees and honoraria for serving as a steering committee member for the Paragon-HF Trial from Novartis, personal fees and honoraria for serving as a steering committee member for the ANTHEM-HF Pivotal trial from LivaNova, and personal fees from and being a member of the advisory committee for Zensun outside the submitted work.

Dr. Pitt has received consulting fees from Amorcyte, AstraZeneca, Aurasense, Bayer, BG Medicine, Gambro, Johnson & Johnson, Mesoblast, Novartis, Pfizer, Relypsa, and Takeda; research grant support from Forest Laboratories; holds stock in Aurasense, Relypsa, BG Medicine, and Aurasense; and has a pending patent related to site-specific delivery of eplerenone to the myocardium.

Dr. Pfeffer has received research support from Novartis; serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, DalCor, Genzyme, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Teva, and Thrasos; and has stock options in DalCor.

Dr. Solomon has received research grants from Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bellerophon, Bayer, BMS, Celladon, Cytokinetics, Eidos, Gilead, GSK, Ionis, Lone Star Heart, Mesoblast, MyoKardia, NIH/NHLBI, Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, Theracos, and has consulted for Akros, Alnylam, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Cardior, Corvia, Cytokinetics, Daiichi-Sankyo, Gilead, GSK, Ironwood, Merck, Myokardia, Novartis, Roche, Takeda, Theracos, Quantum Genetics, Cardurion, AoBiome, Janssen, Cardiac Dimensions, Tenaya.

Dr. Vardeny reported receiving personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur outside the submitted work.

Sources of Funding

This research was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health contract HH-SN268200425207C. The content of this article does not necessarily represent the views of the National Heart, Lund, and Blood Institute or of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Abbreviations List:

- BNP

B-type natriuretic peptide

- CV

cardiovascular

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimokawa H, Miura M, Nochioka K, Sakata Y. Heart failure as a general pandemic in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 884–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, van Heerebeek L, Zile MR, Kass DA, Paulus WJ. Phenotype-Specific Treatment of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Multiorgan Roadmap. Circulation 2016; 134: 73–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction In Perspective. Circ Res 2019; 124: 1598–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Runganga M, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Multiple medication use in older patients in post-acute transitional care: a prospective cohort study. Clin Interv Aging 2014; 9: 1453–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishtala PS, Salahudeen MS. Temporal Trends in Polypharmacy and Hyperpolypharmacy in Older New Zealanders over a 9-Year Period: 2005–2013. Gerontology. 2015; 61: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Rosenberg L, Anderson TE, Mitchell AA. Recent patterns of medication use in the ambulatory adult population of the United States: the Slone survey. JAMA. 2002; 287: 337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004; 57: 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onder G, Petrovic M, Tangiisuran B, Meinardi MC, Markito-Notenboom WP, Somers A, Rajkumar C, Bernabei R, van der Cammen TJ. Development and validation of a score to assess risk of adverse drug reactions among in-hospital patients 65 years or older: the GerontoNet ADR risk score. Arch Intern Med. 2010; 170: 1142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, Aspinall SL, Handler SM, Ruby CM, Pugh MJ. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012; 60: 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gómez C, Vega-Quiroga S, Bermejo-Pareja F, Medrano MJ, Louis ED, Benito-León J. Polypharmacy in the Elderly: A Marker of Increased Risk of Mortality in a Population-Based Prospective Study (NEDICES). Gerontology. 2015; 61: 301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai AS, Lewis EF, Li R, Solomon SD, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Clausell N, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, et al. Rationale and design of the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial: a randomized, controlled study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J 2011; 162: 966–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unlu O, Levitan EB, Reshetnyak E, Kneifati-Hayek J, Diaz I, Archambault A, Chen L, Hanlon JT, Maurer MS, Safford MM, et al. Polypharmacy in Older Adults Hospitalized for Heart Failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2020; 13: e006977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinker LM, Konerman MC, Navid P, Dorsch MP, McNamara J, Willer CJ, Tinetti ME, Hummel SL, Goyal P. Complex and Potentially Harmful Medication Patterns in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Am J Med. 2020: S0002–9343(20)30700–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah SJ, Heitner JF, Sweitzer NK, Anand IS, Kim HY, Harty B, Boineau R, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial. Circ Heart Fail 2013; 6: 184–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Claggett B, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, et al. ; TOPCAT Investigators. Spironolactone for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 1383–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Assmann SF, Boineau R, Anand IS, Clausell N, Desai AS, Diaz R, Fleg JL, Gordeev I, et al. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation 2015; 131: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennel PJ, Kneifati-Hayek J, Bryan J, Banerjee S, Sobol I, Lachs MS, Safford MM, Goyal P. Prevalence and determinants of hyperpolypharmacy in adults with heart failure: an observational study from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2019; 19: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019; 67: 674–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prescription drug use in the past 30 days, by sex, race and Hispanic origin, and age: United States, selected years 1988–1994 through 2011–2014. Table 79. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/contents2016.htm#079.

- 22.Page RL 2nd, O’Bryant CL, Cheng D, Dow TJ, Ky B, Stein CM, Spencer AP, Trupp RJ, Lindenfeld J; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committees of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Drugs That May Cause or Exacerbate Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 134: e32–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hales CM, Servais J, Martin CB, Kohen D. Prescription Drug Use Among Adults Aged 40–79 in the United States and Canada. NCHS Data Brief, No. 347. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tromp J, Shen L, Jhund PS, Anand IS, Carson PE, Desai AS, Granger CB, Komajda M, McKelvie RS, Pfeffer MA, et al. Age-Related Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74: 601–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiapella LC, Montemarani Menna J, Mamprin ME. Assessment of polypharmacy in elderly patients by using data from dispensed medications in community pharmacies: analysis of results by using different methods of estimation. Int J Clin Pharm 2018; 40: 987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos LR, Tavares NU, Bertoldi AD, Farias MR, Oliveira MA, Luiza VL, Pizzol TD, Arrais PS, Mengue SS. Polypharmacy and Polymorbidity in Older Adults in Brazil: a public health challenge. Rev Saude Publica 2016;50: 9s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granger BB, Swedberg K, Ekman I, Granger CB, Olofsson B, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, Michelson EL, Pfeffer MA; CHARM investigators. Adherence to candesartan and placebo and outcomes in chronic heart failure in the CHARM programme: double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet 2005; 366: 2005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders NA, Supiano MA, Lewis EF, Liu J, Claggett B, Pfeffer MA, Desai AS, Sweitzer NK, Solomon SD, Fang JC. The frailty syndrome and outcomes in the TOPCAT trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2018; 20: 1570–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorodeski EZ, Goyal P, Hummel SL, Krishnaswami A, Goodlin SJ, Hart LL, Forman DE, Wenger NK, Kirkpatrick JN, Alexander KP; Geriatric Cardiology Section Leadership Council, American College of Cardiology. Domain Management Approach to Heart Failure in the Geriatric Patient: Present and Future. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 1921–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleipool EEF, Wiersinga JHI, Trappenburg MC, van Rossum AC, van Dam CS, Liem SS, Peters MJL, Handoko ML, Muller M. The relevance of a multidomain geriatric assessment in older patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 1264–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramírez E, Rossignoli T, Campos AJ, Muñoz R, Zegarra C, Tong H, Medrano N, Borobia AM, Carcas AJ, Frías J. Drug-induced life-threatening potassium disturbances detected by a pharmacovigilance program from laboratory signals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 69: 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanlon JT, Perera S, Newman AB, Thorpe JM, Donohue JM, Simonsick EM, Shorr RI, Bauer DC, Marcum ZA; Health ABC Study. Potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions in well-functioning community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Pharm Ther 2017; 42: 228–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ewen S, Baumgarten T, Rettig-Ewen V, Mahfoud F, Griese-Mammen N, Schulz M, Böhm M, Laufs U. Analyses of drugs stored at home by elderly patients with chronic heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 2015; 104: 320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaur S, Mitchell G, Vitetta L, Roberts MS. Interventions that can reduce inappropriate prescribing in the elderly: a systematic review. Drugs Aging 2009; 26: 1013–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vinks TH, Egberts TC, de Lange TM, de Koning FH. Pharmacist-based medication review reduces potential drug-related problems in the elderly: the SMOG controlled trial. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(2):123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation 2013; 128: e240–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeder MT, Rickenbacher P, Rickli H, Abbühl H, Gutmann M, Erne P, Vuilliomenet A, Peter M, Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP; TIME-CHF Investigators. N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide-guided management in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: findings from the Trial of Intensified versus standard medical therapy in elderly patients with congestive heart failure (TIME-CHF). Eur J Heart Fail 2013; 15: 1148–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rohde LE, Claggett BL, Wolsk E, Packer M, Zile M, Swedberg K, Rouleau J, Pfeffer MA, Desai AS, Lund LH, Kober L, Anand I, Merkely B, Senni M, Shi V, Rizkala A, Lefkowitz M, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Cardiac and Noncardiac Disease Burden and Treatment Effect of Sacubitril/Valsartan: Insights From a Combined PARAGON-HF and PARADIGM-HF Analysis. Circ Heart Fail 2021; 14: e008052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.