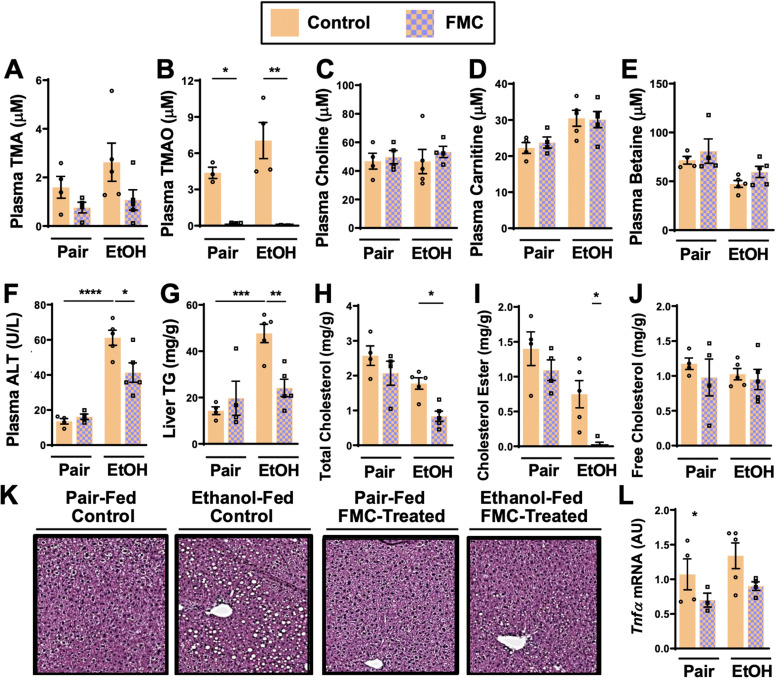

Figure 3. Small molecule choline trimethylamine (TMA) lyase inhibition with fluoromethylcholine (FMC) protects mice against ethanol-induced liver injury.

Nine- to eleven-week-old female C57BL6/J mice were fed either ethanol-fed or pair-fed in the presence and absence of FMC as described in the methods. Plasma levels of TMA (A), trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) (B), choline (C), carnitine (D), and betaine (E) were measured by mass spectrometry (n = 3–5). Plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (F) were measured at necropsy (n = 4–5). Liver triglycerides (G), total cholesterol (H), cholesterol esters (I), and free cholesterol (J) were measured enzymatically (n = 4–5). (K) Representative H&E staining of livers from pair and EtOH-fed mice in the presence and absence of FMC. (L) Hepatic messenger RNA levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnfα). Statistics were completed by a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey’s multiple comparison test. *p ≤ 0.05; **p ≤ 0.01; ***p ≤ 0.001; ****p ≤ 0.0001. All data are presented as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise noted.