Abstract

“Norwalk-like viruses” (NLVs), members of a newly defined genus of the family Caliciviridae, are the most common agents of outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. Two features of NLVs have hindered the development of simple methods for detection and determination of serotype: their genetic diversity and their inability to grow in cell culture. To assess the immune responses of patients involved in outbreaks of gastroenteritis resulting from infection with NLVs, we previously used recombinant-expressed capsid antigens representing four different genetic clusters, but this panel proved insufficient for detection of an immune response in many patients. To extend and further refine this panel, we expressed in baculovirus the capsid genes of three additional genetically distinct viruses, Burwash Landing virus (BLV), White River virus (WRV), and Florida virus. All three expressed proteins assembled into virus-like particles (VLPs) that contained a full-length 64-kDa protein, but both the BLV and WRV VLPs also contained a 58-kDa protein that resulted from deletion of 39 amino acids at the amino terminus. The purified VLPs were used to measure the immune responses in 403 patients involved in 37 outbreaks of acute gastroenteritis. A majority of patients demonstrated a fourfold rise in the titer of immunoglobulin G to the antigen homologous to the outbreak strain, but most seroconverted in response to other genetically distinct antigens as well, suggesting no clear pattern of type-specific immune response. Further study of the antigenicity of the NLVs by use of VLPs should allow us to design new detection systems with either broader reactivity or better specificity and to define the optimum panel of antigens required for routine screening of patient sera.

“Norwalk-like viruses” (NLVs) are a genetically and antigenically diverse group of viruses that belong in the family Caliciviridae (29). NLVs are the major cause of outbreaks of acute nonbacterial gastroenteritis in adults (7, 16) and recently have also been shown to be a common cause of gastroenteritis in children (25). The NLV particle is approximately 34 nm in diameter, as determined by electron microscopy (EM), and shows no particular motif on its capsid. Its genome is composed of a single strand of positive-sense RNA, 7 to 7.5 kb in length, that comprises three open reading frames (ORFs) (15): ORF1 encodes the nonstructural proteins such as the proteinase, the putative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and the helicase (30); ORF2 encodes a 58- to 65-kDa protein, which is the major component of the capsid (11); and ORF3 encodes a minor structural protein of approximately 25 to 28 kDa, whose function(s) remains unknown.

On the basis of the analysis of the amino acid sequence in ORF2, human NLV strains can be divided into two genogroups (genogroups GI and GII), which can be further differentiated into five and nine genetic clusters, respectively (3). Clusters and representative strains have been identified by their genogroups and have been numbered consecutively on the basis of the date of their genetic analysis. The clusters are designated as follows: GI/1 (Norwalk virus [NV]), GI/2 (Southampton virus [SOV]), GI/3 (Desert shield virus [DSV]), GI/4 (Cruise ship strain [CS]), GI/5 (strain 318), GII/1 (Hawaii virus [HV]), GII/2 (Snow Mountain virus [SMV]), GII/3 (Toronto virus [TV]), GII/4 (Bristol virus [BV]), GII/5 (White River virus [WRV]), GII/6 (Florida virus [FV]), GII/7 (Gwynedd virus [GV]), GII/8 (strain 378), and GII/9 (Idaho Falls virus [IFV]). These clusters contain strains that are genetically distinct but that, due to a lack of a cell culture system or animal model, have not yet been shown to be antigenically distinct.

Jiang et al. first expressed the capsid protein of NV in the baculovirus expression system and found that the monomers self-assembled into virus-like particles (VLPs) (14) that were similar to the native particles in their structural, antigenic, and immunogenic properties (10). The structure of recombinant NV consists of 180 copies of the 58- to 65-kDa ORF2 proteins that comprise an NH2-terminal arm facing the interior of the capsid and a shell domain (S) to which a protruding P domain is attached via a flexible hinge, as determined by X-ray crystallography (28). Located toward the exterior of the capsid on the P domain is the P2 subdomain, and because this is so variable, it is thought to contribute to strain diversity (28). Since the preparation of recombinant NV antigen, the baculovirus system has been used to express the capsid proteins of NLV strains representing different genetic clusters such as GI/2 (SOV) (27), GI/3 (DSV [18] and Stavanger virus [21]), GII/1 (HV) (9), GII/3 (TV [17] and Mexico virus [MXV] [26]), and GII/4 (Lordsdale virus [LV] [6] and Grimsby virus [12]). These antigens have been used to study seroprevalence (5, 19, 22, 26, 27) and the immune responses to NLV infections of patients involved in outbreaks of gastroenteritis and of individuals in volunteer challenge studies (8, 13, 23)

Given the absence of an in vivo system for the direct assessment of serotype, we previously used paired sera from patients involved in outbreaks caused by well-characterized NLV strains as a proxy to distinguish immune responses to expressed capsid antigens homologous to the strains causing the outbreak from antigens homologous to other genetically distinct strains (23). We were able to demonstrate a good correlation: 57 to 70% of patients seroconverted when infected with an NLV strain that belonged to the same genetic cluster as the baculovirus-expressed antigen being used. Correspondingly, only 3 to 47% of patients infected with one of the genetically distinct strains, GV or WRV, for which we had no representative antigen, seroconverted.

The aims of the present study were twofold: to express in the baculovirus system the major capsid proteins of three new genetically distinct NLV strains and characterize the synthesized capsid proteins and to use these antigens to extend our previous study (23), in which we examined the correlation of patients' immune responses to a panel of seven antigens. The three new NLV strains from which we expressed the recombinant capsid proteins were baculovirus-expressed recombinant Burwash Landing virus (rBLV; cluster GII/4), baculovirus-expressed recombinant WRV (rWRV; cluster GII/5), and baculovirus-expressed recombinant FV (rFV; cluster GII/6); this strain was previously known as the GV cluster. (Upon sequencing of the ORF2 of GV, we identified it to be genetically distinct from the remaining strains in the cluster and thus reclassified samples from the GV cluster accordingly [3].) rBLV represents the globally common 95/96-US strain which formed a distinct subgroup within the BV cluster (4, 24). Analysis of the amino acid sequences demonstrated that BLV was 95.5% identical to LV in ORF2, thus allowing us to examine antigenic relationships within a genetic cluster. WRV and FV each represent genetically distinct NLV clusters (1, 23) for which we previously did not have a representative antigen. We used VLPs prepared from these three viruses to extend our previously published data (23) by comparing the responses of sera from an expanded collection of patients involved in outbreaks and infected with NLV strains from three GI clusters and seven GII clusters to the panel of six antigens (one GI cluster and five GII clusters). In addition, we investigated in greater detail the responses of serum from patients infected with BLV-like and LV-like strains (cluster GII/4) against both rLV and rBLV antigens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Outbreaks.

The clinical specimens used in the present study were from patients involved in outbreaks of suspected viral gastroenteritis reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention between March 1990 and 1997. The 322-base capsid regions of the outbreak strains had been amplified and sequenced as described previously (23, 24). All outbreak strains were classified into genetic clusters according to the nomenclature recently described by Ando et al. (3).

Cloning strategy.

For the three strains tested, BLV, WRV, and FV (GenBank accession numbers AF414425, AF414423, and AF414407, respectively), a total of 3 kb, consisting of 600 nucleotides of ORF1 together with the complete sequences of ORF2 and ORF3, was amplified as described previously (2), cloned, and sequenced (Y. Seto et al., unpublished data). PCR fragments containing ORF2 were generated by using primers engineered with restriction sites (Table 1). The PCR fragments were digested, ligated into transfer vector pVL1392 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), and transformed into HB101 cells. The resulting clones were screened for the presence of inserts by PCR with primer Mon 381 and primer Mon 382 (5′-TGATAGAAATTATTCCTAACATCAGG-3′) for FV, primer Mon 383 for BLV, or primers jsn7 and jsn8 for WRV, as described previously (23). The reading frames, sizes, and nucleotide sequences of selected clones were confirmed prior to transfection.

TABLE 1.

Descriptions of oligonucleotide primers used in this studya

| Strain | Polarity | Restriction site | Sequenceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| FV | + | XbaI | CTAGTCTAGAATGAAGATGGCGTCGAATGAC |

| − | BamHI | CGCGGATCCCGAAGAAGGCTCCAGCCATTATTG | |

| WRV | + | BglII | GAAGATCTATGAAGATGGCGTCGAAT |

| − | NotI | ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCGAAAGCTCCTGC | |

| BLV | + | EcoRI | CCGGAATTCATGAAGATGGCGTCGAATGAC |

| − | BamHI | CGCGGATCCCCAGCCATTATAATGCACG |

The primers used for cloning were designed by using the sequence information from Y. Seto et al. (unpublished data).

The restriction site of each enzyme is underlined. The start codons of the ORF2 sequences are in boldface. Extra bases were added upstream of each restriction site, as suggested by New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.).

Production of recombinant baculoviruses.

Monolayers of Sf9 (Spodoptera frugiperda) insect cells were cotransfected with defective wild-type baculovirus DNA (Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus) and the transfer vector containing the insert by standard transfection procedures (Pharmingen). For all constructs, at 5 days postinfection the cell lysate was examined for the presence of VLPs by EM. Three rounds of purification of single plaques were used to purify recombinant baculoviruses producing VLPs. EM and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with serum from a patient involved in an outbreak caused by a homologous virus were used to test for VLP production. A high-titer seed stock of recombinant baculovirus was produced by infecting Sf9 cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 to 0.2 in TMN-FH medium (Pharmingen) containing 10% fetal calf serum. The viral titer was determined by plaque assay.

Antigen production and purification of VLPs.

VLPs were prepared by using High-Five cells (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) infected in serum-free medium (Excell-400; JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, Kans.) at a multiplicity of infection of 10. The cell lysate was collected at 5 days postinfection. The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was further clarified to remove baculovirus particles by centrifugation at 8,300 × g for 30 min at 4°C. VLPs were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C, and the resulting pellets were allowed to resuspend overnight in Grace's medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10 μM leupeptin (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Cesium chloride was added to a final concentration of 1.36 g/ml and centrifuged at 38,000 rpm for 22 h at 10°C with a Beckman SW55 Ti rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). Fractions containing the VLPs were desalted by using Centricon-30 columns (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.), and purified VLPs were eluted in Grace's medium containing 10 μM leupeptin. EM and electrophoresis on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gel were used to assess the quantities and the qualities of the VLPs produced. Yield was determined with a protein assay reagent kit (Micro BCA; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Western blotting and amino-terminal microsequencing of expressed capsid proteins.

The purified baculovirus-expressed proteins from BLV, WRV, and FV were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The resulting gel was washed twice in ultrapure water containing 2 mg of dithiothreitol (DTT) per ml for 10 min each time at room temperature and was then washed four times in 10 mM 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) buffer (pH 11) containing 2 mg of DTT per ml for 10 min for each bath at room temperature. Purified capsid proteins were electrotransferred (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) to an Immobilon PSQ membrane (pore size, 0.2 μm; Millipore Corp.) for 1.5 h at 75 V. The membrane was then rinsed by using at least four washes in water containing 2 mg of DTT per ml before staining with a solution of methanol-water-acetic acid (5:4:1) containing 0.05% Coomassie blue. Following destaining (methanol-water-acetic acid; 5:4:1), the immobilized proteins were excised and processed for microsequencing.

Serological characterization using purified VLPs.

To determine the titers of immunoglobulin G (IgG) to each antigen in patient serum, paired serum specimens were assayed at a single dilution (1:1,000), as described previously (23). IgG units were calculated by using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of a reference serum sample on each test plate. Seroconversion was defined as a fourfold or greater rise between the acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples for a given patient.

RESULTS

Characterization of VLPs expressed with baculovirus system.

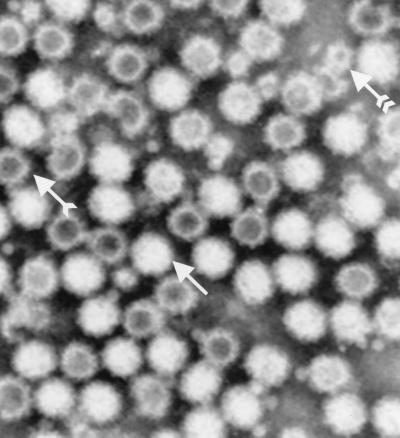

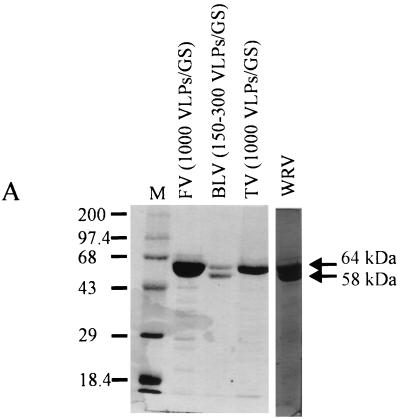

For all constructs, VLPs were detected at 5 days postinfection by EM in both the High-Five cell lysate and the supernatant (25 to 150 VLPs per grid square [GS]). Isopycnic centrifugation in CsCl yielded a single band with a buoyant density of 1.32 g/ml (the band was more diffuse for BLV). By EM it was found that these bands contained more than 1,000 VLPs/GS for all constructs but BLV (300 VLPs/GS). Following CsCl purification, a majority of the VLPs were intact and had diameters of approximately 34 nm. However, the BLV preparation contained more particles that were broken or small (20 nm) (Fig. 1). Additional purification by sucrose gradient centrifugation brought no major improvement in the purity of the protein and appeared to increase the background when the antigen was used for serodiagnosis by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (data not shown). For all constructs, SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified fractions demonstrated no differences in the migration of the major 64-kDa protein. For two of the constructs, BLV and WRV, a second band was observed at 58 kDa (Fig. 2A). The VLPs were purified from 500 ml of medium, corresponding to 1.6 × 108 infected cells, and yielded 400 μg of purified protein for BLV, 2 to 3 mg of purified protein for FV, and 2.5 mg of purified protein for WRV.

FIG. 1.

Electron micrograph of CsCl-purified VLPs from BLV construct at a magnification of ×265,085, after negative staining. Complete VLPs (white particles) are indicated by an arrow without a tail. Broken VLPs (dark particles) are indicated by a single-tailed arrow, and the 20- to 22-nm subunit particles are indicated by a double-tailed arrow.

FIG. 2.

(A) SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel of 10 μl of CsCl-purified VLPs from TV, FV, BLV, and WRV baculovirus-expressed proteins. The 64- and 58-kDa proteins are indicated. Lane M, protein weight marker. (B) Amino acid sequence of the expressed proteins from panel A. The NV sequence with an NH2-terminal arm (the shaded sequence), involved in capsid stability, is indicated as a reference (28). The first methionines of the 64-kDa proteins are indicated; the first amino acids of the 58-kDa proteins found in the BLV and WRV preparations are boxed.

The amino-terminal extremities of the 64- and 58-kDa capsid proteins of all constructs, together with purified baculovirus-expressed recombinant TV (rTV) as a control, were sequenced by Edman degradation. For the 64-kDa proteins, translation began at the first methionine of ORF2, whereas the 58-kDa proteins of the BLV and WRV constructs were truncated, with 37 amino residues less than the number of residues in the 64-kDa protein from the NH2-terminal region (Fig. 2B). When compared with the X-ray crystallographic structure for NV, these 37 missing amino acids were homologous to those of baculovirus-expressed recombinant NV (rNV) that face the interior of the capsid (28).

Serological characterization.

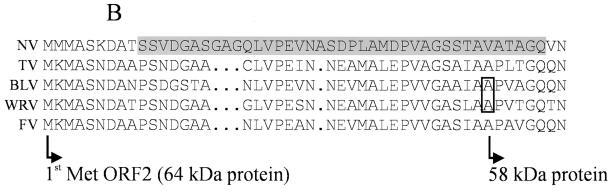

We used our three new antigens to examine the seroresponses of 403 patients involved in outbreaks for which the NLV strains have previously been genetically characterized (Table 2). rFV and rWRV were used to analyze paired serum samples from patients involved in 37 outbreaks caused by NLV strains belonging to GI clusters (GI/3 [DSV], GI/4 [CS]) and GII clusters (GII/1 [HV], GII/2 [SMV], GII/3 [TV], GII/4 [BV], GII/5 [WRV], GII/6 [FV], GII/7 [GV]). The immune responses of patients infected with GI strains versus the immune responses of patients infected with GII strains were quite distinct and specific, with the best responses noted being to the antigen from the homologous strain. The rise in the titer of IgG to each antigen occurred most frequently and was of the greatest magnitude when the outbreak was caused by a strain belonging to the same cluster as the antigen used for testing. For example, 73% of patients involved in outbreaks caused by GII/5 (WRV) exhibited seroconversions to rWRV antigen, whereas 56% or fewer patients involved in outbreaks caused by other strains demonstrated seroconversions; the magnitudes of the rises were 20.7-fold and 7.2-fold or less, respectively. We also observed, however, strong heterologous immune responses between paired sera from patients involved in GII/1-related outbreaks and rWRV and rFV antigens; between sera from patients involved in GII/3-related outbreaks and baculovirus-expressed recombinant HV (rHV), rWRV, and rFV antigens; between sera from patients involved in GII/4-related outbreaks and the rWRV antigen; and between sera from patients involved in GII/6-related outbreaks and the rWRV antigen. Surprisingly, only 31% of 35 patients involved in GII/6 (FV) outbreaks exhibited seroconversions in response to the rFV antigen, while 44% of GII/3 (TV) patients demonstrated seroconversions; however, the differences in the magnitudes of the rises in titers of antibodies to any of the expressed antigens were not significant. Only 3 to 38% of patients involved in GI outbreaks demonstrated seroconversions in response to one or more GII antigens, while only 0 to 27% of patients involved in GII outbreaks demonstrated seroconversions in response to the NV (GI) antigen (Table 2). The results obtained from the testing of sera from patients involved in the outbreaks included in the present study (outbreaks numbered 326 and higher) with rNV, rHV, baculovirus-expressed recombinant MXV (rMXV; or closely related virus rTV), and baculovirus-expressed recombinant LV (rLV) were consistent with those published previously (23). Finally, in agreement with our previous results, only 20% or fewer patients involved in GII/2 (SMV)-related outbreaks (the SMV antigen was not represented in our antigen collection) exhibited seroconversions in response to any of the seven antigens in our panel.

TABLE 2.

Seroconversions in response to baculovirus-expressed VLPs in patients involved in outbreak

|

Genetic classification from Ando et. al. (3)

rNV, rTV, rLV, and rHV, have been described previously (21). rBLV, rWRV, and rFV are virus capsid proteins prepared the study described in this report.

Outlined areas highlight the serological assay results obtained by using the antigen homologous to the genetic cluster that caused the the outbreak.

Boldface type indicates that greater than 50% of patients involved in the outbreak showed greater than or equal to fourfold rises in titer to the expressed antigen.

NA, not assessed.

Tested with rMXV.

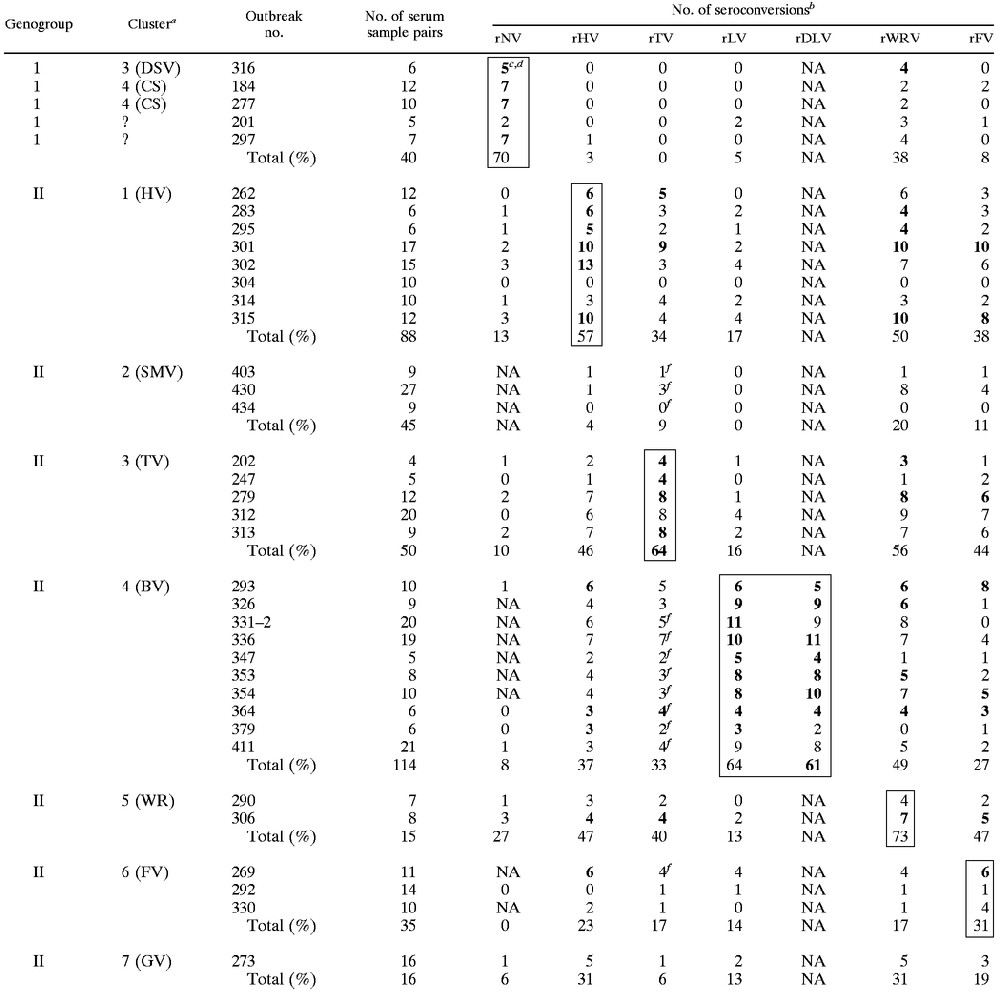

To further analyze heterotypic and homotypic seroresponses among patients involved in outbreaks, we divided all patients into one of four categories, depending on their seroresponses to the individual antigens, as follows: category A, no seroconversions; category B, seroconversion against only the homologous antigen; category C, seroconversion against the homologous antigen and at least one heterologous antigen; and category D, seroconversion against a heterologous antigen only (Table 3). Among the patients from all outbreaks, category C seroresponses predominated. Of the 110 patients with no seroconversion (category A), the sera from 22 patients (20%) had a very high acute-phase titer (>50,000 units; as the standard curve plateaus at 200,000 units, a fourfold rise in titer would not be detected if the acute-phase serum sample had a titer of 50,000 units or greater), and the sera from an additional 12 patients (11%) had a moderately high acute-phase titer (25,000 to 50,000 units). The majority of these sera were from patients involved in outbreak 304 (HV) and outbreaks 292 (FV) and 330 (FV), in which less than 50% of patients demonstrated seroconversion in response to the homologous antigen and the high titer of preexisting antibody was likely preventing us from detecting a seroresponse to the present infection. Similarly, 8 (32%) of the 25 patients from category D had a moderate to high acute-phase titer (>25,000) of antibody to the homologous antigen in serum, which may have masked seroconversions in response to that antigen. The cumulative frequency of seroconversions among patients from categories B, C, and D was 68% and was representative of the overall detection rate for serological analysis of patients involved in outbreaks when antigen homologous to the one causing the outbreak was included in the detection panel. When the homologous antigen was not available, the frequency of seroconversion (categories C and D) was 55%.

TABLE 3.

Frequencies and types of seroconversions developed by each patient involved in outbreaks with GI, GII/1, GII/3, GII/4, GII/5 and GII/6 using NV, HV, TV, LV, WRV, and FV synthetic antigens

| Cluster:antigena | % Homology for the following categoryb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |

| GI:NV | 20 (8) | 38 (15) | 30 (12) | 13 (5) |

| GII/1:HV | 31 (27) | 8 (7) | 52 (46) | 9 (8) |

| GII/3:TV | 28 (14) | 4 (2) | 60 (30) | 8 (4) |

| GII/4:LV | 32 (37) | 14 (16) | 50 (57) | 4 (4) |

| GII/5:WRV | 27 (4) | 7 (1) | 67 (10) | 0 (0) |

| GII/6:FV | 57 (20) | 9 (3) | 23 (8) | 11 (4) |

| Totalc | 32 (110) | 13 (44) | 48 (163) | 7 (25) |

Cluster of the NLV strain detected during the outbreak and the corresponding antigen.

The numbers of serum pairs associated with each category are given in parentheses.

The total for categories C and D is 55% (188 shown sample pairs). The total for categories B, C, and D is 68% (232 serum sample pairs).

Finally, we compared patient seroresponses to two antigens within the same genetic cluster. BLV and LV share 95.5% amino acid identity in ORF2. Although the ORF2 proteins of these two viruses are genetically closely related, BLV formed a distinct subset within the GII/4 (BV) cluster and was the strain that was detected globally and that predominated in the United States from 1995 to 1996 (22). Overall, 77% of patients demonstrated seroconversion in response to either the BLV antigen or the LV antigen, or both; and individually, 61 and 64% of the patients demonstrated seroconversion in response to the BLV antigen and the LV antigen, respectively, of which only 6 (5.3%) and 8 (7.0%) of patients, respectively, demonstrating seroconversion in response to only one antigen (P < 0.0001 by two-tailed Fisher's exact text). There were no significant differences in the fold rise in titers to the BLV and LV antigens, which ranged from 0.1 to 152.7 (mean, 20.7) and 0.2 to 171.4 (mean, 18.9), respectively.

DISCUSSION

The identification of serotypes of NLVs has important implications for the development of immune diagnostics and new vaccines. For the NLVs, determination of classical serotypes is not possible because the virus cannot be cultivated to permit traditional neutralization assays, and the problem is compounded by the genetic diversity of the virus, with several genogroups and many distinct clusters of strains being observed. Our goal for the project described here was to use clinical specimens (both stool and paired serum specimens from persons involved in outbreaks) to gather insights into the homotypic and heterotypic immune responses to specific clusters of NLVs. We further believed that having a collection of seven expressed VLP antigens representing six distinct genetic clusters would allow us to clearly distinguish cluster-specific immune responses as a proxy for serotype. Our results generally support the hypothesis that individuals develop a better immune response to an antigen expressed from strains of the same genetic cluster as the infecting strain than to antigens from strains of different genetic clusters. Nonetheless, in individual patients infected with GII viruses, many heterotypic reactions were detected, and we could not unambiguously determine the cluster type of the infecting strain simply from the magnitude of the seroconversion to a specific VLP. For all GII-related outbreaks except GII/2- and GII/7-related outbreaks, we observed similar rates of detection of immune responses using the homologous antigen and at least one heterologous antigen; homologous antigens were not available for the GII/2- and GII/7-related outbreaks. Heterologous immune responses were observed in earlier studies (20) and may reflect previous exposure to different NLVs with cross-reacting epitopes or minor antigenic differences between the infecting strain and the homotypic VLP used for testing. The implication of these observations for diagnosis is that, to detect recent exposure to NLV by serology, one needs to screen paired serum specimens with several different antigens. The implication for vaccines is that challenge studies will have to be conducted with a variety of heterotypic challenge strains in people with diverse backgrounds of preexisting antibodies in order to determine the extent of cross-protection afforded by a single vaccine strain.

The results of the present study extend our previous observations that a single antigen could be used to detect seroresponses in the majority of patients infected with GI strains, while multiple antigens would be required to detect seroresponses in patients infected with different GII strains. Correspondingly, in the study described in this paper, we added three GII antigens to our panel, and our results indicate that although we can detect seroresponses in 55 to 68% of patients involved in an outbreak, depending on the composition of our panel of antigens, representatives of clusters GII/2 (SMV) and GII/7 (GV) are still required to complete the test panel.

By using the BLV, WRV, and FV recombinant antigens, overall, seroconversions were more common and stronger among patients infected with a strain belonging to the same genetic cluster as the VLP parent strain. In our analysis of intracluster reactivity, patient seroresponses to antigens of BLV and LV, both of which are representatives of genetic cluster GII/4, were comparable. These results indicate that strains with up to 4.5% divergence in their ORF2 amino acid sequence are still antigenically related. For the FV recombinant antigen, detection of the seroresponses to NLVs belonging to other clusters was more efficient than detection of seroresponses to viruses from FV-related outbreaks. Seroresponses to rFV were detected in 31% of patients involved in the three GII/6-related outbreaks, but seroresponses to rFV were detected in 47, 44, and 38% of patients involved in GII/5-, GII/3-, and GII/1-related outbreaks, respectively. The reason for the higher level of heterotypic reactivity is unknown but may be related to the small sample size and high levels of preexisting antibodies in patients involved in outbreaks 292 and 330. A total of 11 (57%) of the 19 patients who did not seroconvert had moderate to high acute-phase titers of 25,000 units or greater, which may have precluded detection of a fourfold increase.

Our present data that give cumulative frequencies of seroconversions of 55% (categories C and D) and 68% (categories B, C, and D) (Table 3) support our previous definition for an outbreak of NLV, which requires that greater than 50% of patients involved in the outbreak show a fourfold or greater rise in antibody titer by serology (23). Thus, serological analysis with a panel of representative antigens (in our case, six antigens) could provide a reliable alternative to reverse transcription-PCR when stool specimens are unavailable for testing. In contrast, the small number of patients who demonstrated a homologous response only (category B) and the predominance of patients with heterologous responses (category C) indicate that serological analysis alone is inadequate for the typing of the NLV strain causing the outbreak. Human IgG immune responses to NLV infections are generally not type specific, with presumably both preexisting antibody and anamnestic responses playing a role. Although it has been proposed that the measurement of IgM or IgA seroresponses might be more type specific (8), to date these assays have not been widely applied. Biological or chemical removal of IgG is often required to facilitate direct detection of IgM or IgA, or a complementary serum sample in which antibody against each recombinant antigen is raised is required for indirect assay formats.

The second most common category of seroresponses among patients involved in an outbreak was no seroconversions (category A). One-third of these patients had high levels of IgG (25,000 to 200,000 units) in their acute-phase serum samples. This high IgG titer is consistent with those detected in studies showing a high seroprevalence of NLVs in human populations and is most likely responsible for our inability to detect seroconversions in these patients. While we are uncertain of the reason why we failed to detect conversions in the remaining patients in category A, for most patients matched stool and serum specimens were not available for the direct assessment of infection status.

In the present study, we cloned and expressed the ORF2 proteins of three genetically distinct NLV strains by using the baculovirus system. VLPs were observed by EM for each construct. Analysis of the purified VLPs by SDS-PAGE showed that the molecular mass was approximately 64 kDa, while the calculated molecular mass on the basis of the sequence was approximately 58 kDa, a difference which may be a result of electrophoresis conditions. Microsequencing showed the translation of the 64-kDa protein started at the first methionine encoded by ORF2 for all constructs. The second protein of 58 kDa, which was present at a quantity equal to that for the 64-kDa protein observed for the BLV and WRV constructs, represents a truncated protein that starts at the alanine located at position 38 in ORF2. The addition of a protease inhibitor, such as leupeptin, did not prevent the production of the truncated protein (data not shown). For both constructs, the presence of the 58-kDa protein more likely reflects a degradation phenomenon or a specific cleavage of the 64-kDa protein rather than an internal binding of the ribosome. On the basis of the amino acid sequence, such cleavage could be due to a metalloproteinase activity, so chelating agents such as EDTA might reduce the level of production of this 58-kDa protein. The protein composition of the capsid as well as the primary and secondary structures of the capsid protein(s) can affect the stabilities of the VLPs, as shown by the effects of alkaline buffers on VLPs (31). Although the amino acid sequences of the ORF2 proteins from TV and FV show cleavage sites similar to those for the ORF2 proteins from BLV and WRV, no 58-kDa proteins were observed, and we were able to produce stable VLPs. Our results suggest that the overall lower levels of stability of the VLPs of BLV and WRV may be due to the presence of the truncated protein. Determination of the protein structure of rNV by X-ray crystallography has indicated that residues 10 to 49 (corresponding to residues 10 to 46 of TV, BLV, WRV, and FV; Fig. 2B) form the NH2-terminal arm, which faces the interior of the capsid and which is thought to play a role in imposing symmetry on the interactions between the S domains in the icosahedral shell of the calicivirus capsid (28).

The combination of X-ray crystallography data, nucleotide sequences, and antigenicity data will be helpful in the evolution of simpler technologies for serological analysis with new synthetic antigens such as peptides or mosaic proteins presenting common epitopes. Systems that use such methods would be good alternatives to the present baculovirus expression systems. Moreover, the study of antigenicity with VLPs will enable us to detect putative common epitopes between NLV clusters, which could be used to improve serodiagnostics for these viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the many state health departments for providing the serum specimens from patients involved in outbreaks analyzed in the study described in this paper. In addition, we thank Tamara Crew, Biotechnology Core Facility Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for protein sequencing, and John O'Connor and Anne Mather for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ando T, Jin Q, Gentsch J R, Monroe S S, Noel J S, Dowell S F, Cicirello H G, Kohn M A, Glass R I. Epidemiologic applications of novel molecular methods to detect and differentiate small round structured viruses (Norwalk-like viruses) J Med Virol. 1995;47:145–152. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ando T, Monroe S S, Noel J S, Glass R I. A one-tube method of reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction to efficiently amplify a 3-kilobase region from the RNA polymerase gene to the poly(A) tail of small round-structured viruses (Norwalk virus-like viruses) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:570–577. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.570-577.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando T, Noel J S, Fankhauser R L. Genetic classification of “Norwalk-like viruses.”. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl. 2):S336–S348. doi: 10.1086/315589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beller M, Ellis A, Lee S H, Drebot M A, Jenkerson S A, Funk E, Sobsey M D, Simmons O D, Monroe S S, Ando T, Noel J, Petric M, Middaugh J P, Spika J S. Outbreak of viral gastroenteritis due to a contaminated well. JAMA. 1997;278:563–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimitrov D H, Dashti S A H, Ball J M, Bishbishi E, Alsaeid K, Jiang X, Estes M K. Prevalence of antibodies to human caliciviruses (HuCVs) in Kuwait established by ELISA using baculovirus-expressed capsid antigens representing two genogroups of HuCVs. J Med Virol. 1997;51:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dingle K E, Lambden P R, Caul E O, Clarke I N. Human enteric Caliciviridae: the complete genome sequence and expression of virus-like particles from a genetic group II small round structured virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2349–2355. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fankhauser R L, Noel J S, Monroe S S, Ando T A, Glass R I. Molecular epidemiology of “Norwalk-like viruses”in outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1571–1578. doi: 10.1086/314525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gray J J, Cunliffe C, Ball J, Graham D Y, Desselberger U, Estes M K. Detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgA, and IgG Norwalk virus-specific antibodies by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with baculovirus-expressed Norwalk virus capsid antigen in adult volunteers challenged with Norwalk virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:3059–3063. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.3059-3063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green K Y, Kapikian A Z, Valdesuso J, Sosnovtsev S, Treanor J J, Lew J F. Expression and self-assembly of recombinant capsid protein from the antigenically distinct Hawaii human calicivirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1909–1914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1909-1914.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green K Y, Lew J F, Jiang X, Kapikian A Z, Estes M K. Comparison of the reactivities of baculovirus-expressed recombinant Norwalk virus capsid antigen with those of the native Norwalk virus antigen in serologic assays and some epidemiologic observations. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2185–2191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2185-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenberg H B, Valdesuso J, Kalica A P, Wyatt R G, McAuliffe V J, Kapikian A Z, Chanock R M. Proteins of Norwalk virus. J Virol. 1981;37:994–999. doi: 10.1128/jvi.37.3.994-999.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hale A D, Crawford S E, Ciarlet M, Green J, Gallimore C, Brown D W, Jiang X, Estes M K. Expression and self-assembly of Grimsby virus: antigenic distinction from Norwalk and Mexico viruses. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;1:142–145. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.142-145.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale A D, Lewis D C, Jiang X, Brown D W. Homotypic and heterotypic IgG and IgM antibody responses in adults infected with small round structured viruses. J Med Virol. 1998;54:305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X, Wang M, Graham D Y, Estes M K. Expression, self-assembly, and antigenicity of the Norwalk virus capsid protein. J Virol. 1992;66:6527–6532. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6527-6532.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Wang M, Wang K, Estes M K. Sequence and genomic organization of Norwalk virus. Virology. 1993;195:51–61. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapikian A Z, Estes M K, Chanock R M. Norwalk group of viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, Chanock R M, Melnick J L, Monath T P, Roizman B, Straus S E, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 783–810. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leite J P, Ando T, Noel J S, Jiang B, Humphrey C D, Lew J F, Green K Y, Glass R I, Monroe S S. Characterization of Toronto virus capsid protein expressed in baculovirus. Arch Virol. 1996;141:865–875. doi: 10.1007/BF01718161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lew J F, Kapikian A Z, Valdesuso J, Green K Y. Molecular characterization of Hawaii virus and other Norwalk-like viruses: evidence for genetic polymorphism among human caliciviruses. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:535–542. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis D C, Hale A, Jiang X, Eglin R, Brown D W G. Epidemiology of Mexico virus, a small round-structured virus in Yorkshire, United Kingdom, between January 1992 and March 1995. J Infect Dis. 1996;175:951–954. doi: 10.1086/513998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madore H P, Treanor J J, Buja R, Dolin R. Antigenic relatedness among the Norwalk-like agents by serum antibody rises. J Med Virol. 1990;32:96–101. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890320206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myrmel M, Rimstad E. Antigenic diversity of Norwalk-like viruses: expression of the capsid protein of a genogroup I virus, distantly related to Norwalk virus. Arch Virol. 2000;145:711–723. doi: 10.1007/s007050050665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakata S, Honma S, Numata K, Kogawa K, Ukae S, Adachi N, Jiang X, Estes M K, Gatheru Z, Tukel P M, Chiba S. Prevalence of human calicivirus infections in Kenya as determined by enzyme immunoassays for three genogroups of the virus. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3160–3163. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3160-3163.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noel J S, Ando T, Leite J P, Green K Y, Dingle K E, Estes M K, Seto Y, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Correlation of patient immune responses with genetically characterized small round-structured viruses involved in outbreaks of nonbacterial acute gastroenteritis in the United States, 1990 to 1995. J Med Virol. 1997;53:372–383. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199712)53:4<372::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noel J S, Fankhauser R L, Ando T, Monroe S S, Glass R I. Identification of a distinct common strain of “Norwalk-like viruses” having a global distribution. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1334–1344. doi: 10.1086/314783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang X-L, Joensuu J, Vesikari T. Human calicivirus-associated sporadic gastroenteritis in Finnish children less than two years of age followed prospectively during a rotavirus vaccine trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18:420–426. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199905000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker S P, Cubitt W D, Jiang X. Enzyme immunoassay using baculovirus-expressed human calicivirus (Mexico) for the measurement of IgG responses and determining its seroprevalence in London, UK. J Med Virol. 1995;46:194–200. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelosi E, Lambden P R, Caul E O, Liu B, Dingle K, Deng Y, Clarke I N. The seroepidemiology of genogroup 1 and genogroup 2 Norwalk-like viruses in Italy. J Med Virol. 1999;58:93–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad B V V, Hardy M E, Dokland T, Bella J, Rossmann M G, Estes M K. X-ray crystallographic structure of the Norwalk virus capsid. Science. 1999;286:287–290. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pringle C R. Virus taxonomy. Arch Virol. 1999;144:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s007050050515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seah E L, Marshall J A, Wright P J. Open reading frame 1 of the Norwalk-like virus Camberwell: completion of sequence and expression in mammalian cells. J Virol. 1999;73:10531–10535. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10531-10535.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White L J, Hardy M E, Estes M K. Biochemical characterization of a smaller form of recombinant Norwalk virus capsids assembled in insect cells. J Virol. 1997;71:8066–8072. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.8066-8072.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]