Abstract

Screening of blood donors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection by PCR permits the earlier diagnosis of HIV-1 infection compared with that by serologic assays. We have established a high-throughput reverse transcription (RT)-PCR assay based on 5′-nuclease PCR. By in-tube detection of HIV-1 RNA with a fluorogenic probe, the 5′-nuclease PCR technology (TaqMan PCR) eliminates the risk of carryover contamination, a major problem in PCR testing. We outline the development and evaluation of the PCR assay from a technical point of view. A one-step RT-PCR that targets the gag genes of all known HIV-1 group M isolates was developed. An internal control RNA detectable with a heterologous 5′-nuclease probe was derived from the viral target cDNA and was packaged into MS2 coliphages (Armored RNA). Because the RNA was protected against digestion with RNase, it could be spiked into patient plasma to control the complete sample preparation and amplification process. The assay detected 831 HIV-1 type B genome equivalents per ml of native plasma (95% confidence interval [CI], 759 to 936 HIV-1 B genome equivalents per ml) with a ≥95% probability of a positive result, as determined by probit regression analysis. A detection limit of 1,195 genome equivalents per ml of (individual) donor plasma (95% CI, 1,014 to 1,470 genome equivalents per ml of plasma pooled from individuals) was achieved when 96 samples were pooled and enriched by centrifugation. Up to 4,000 plasma samples per PCR run were tested in a 3-month trial period. Although data from the present pilot feasibility study will have to be complemented by a large clinical validation study, the assay is a promising approach to the high-throughput screening of blood donors and is the first noncommercial test for high-throughput screening for HIV-1.

To date, serologic enzyme immunoassay-based antibody testing plus confirmation by Western blotting are “gold standards” for the screening of blood donors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) infection. Due to the lack of detectable antibody early after exposure to HIV-1, these assays fail to detect a recent HIV infection. They leave a diagnostic window during which the viral load is high (on the order of 106 to 109 genome equivalents per ml of donor plasma) (1, 2, 4, 15, 16). Transmission of HIV-1 by blood products from individuals who donated blood during this preseroconversion window period has been reported previously (23). Schreiber et al. have calculated the remaining residual risk of HIV-1 transmission from serologically negative blood to range from 1/202,000 to 1/2,778,000 (20). Screening for HIV-1 by PCR is expected to reduce the window period before seroconversion to positivity for HIV by 11 days (20).

Although the feasibility of screening of blood donors for HIV-1 by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR has been demonstrated, difficulties with post-PCR processing, assay stability, and interpretation of results restrict its use to specialized laboratories (18). It was our aim to establish a high-throughput PCR assay for screening for HIV-1 infection that provides reliable results without the need for a sophisticated means of interpretation of results. We have used the 5′-nuclease PCR technology (TaqMan PCR), in which a fluorescent signal is generated in the course of amplification and the result is reported through the closed cap of the reaction tube. A probe labeled with a reporter dye and a quencher dye is added to the reaction mixture prior to amplification. Fluorescence in the intact probe is quenched by trans-molecular energy transfer (22). Due to its intrinsic 5′-nuclease activity, Taq DNA polymerase digests the probe after it specifically anneals to the PCR product generated in each cycle. This liberates the reporter dye from the quencher dye, causing an increase in reporter dye-specific fluorescence during PCR. The risk of post-PCR contamination is thereby eliminated because the reaction tubes do not have to be opened for product detection (8, 12).

When large numbers of patient samples are routinely tested by PCR, amplification failures due to inhibition of the reaction must be efficiently monitored to avoid false-negative results. Inhibition of PCR is usually detected by spiking a patient's sample with a weakly positive control after the nucleic acids are prepared or while the nucleic acids are being prepared (3, 10, 17). This procedure does not allow control of the complete nucleic acid preparation process, including lysis of the pathogen. To implement monitoring of the complete preparation, we have used a phage-packaged internal control RNA sequence (Armored RNA) that is coextracted with the viral RNA from plasma (14), coamplified in the same reaction tube, and detected with a heterologous probe.

In this report, we outline the development and evaluation of the assay from a technical point of view, focusing on analytical sensitivity and specificity and on technical feasibility for the qualitative high-throughput testing of single and pooled samples. The report first provides, however, preliminary data on clinical performance obtained by testing a panel of plasma samples in which the HIV-1 load was quantified, a panel of plasma samples from patients infected with different subtypes of HIV-1 group M, and two panels of follow-up plasma from patients who have seroconverted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HIV-1 sequence alignment.

The 1996 alignment of consensus HIV-1 sequences of the Los Alamos National Laboratory was downloaded from ftp://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

HIV-1-positive plasma samples.

Plasma samples from 39 individual patients with a confirmed diagnosis of HIV-1 infection were kindly provided by H. Rabenau, Institute of Virology, University of Frankfurt. The viral loads in all samples had previously been determined by the Amplicor Monitor (version 1.5) HIV-1 RT-PCR assay (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, N.J.). The range of viral loads in the samples was <400 to 106 genome equivalents (geq)/ml, with 13 samples having loads below 20,000 geq/ml and 8 samples having loads below 2,000 geq/ml.

Reference samples.

HIV-1-positive plasma samples in which the HIV-1 loads were quantified were obtained from INSTAND e.V., Düsseldorf, Germany, a national reference center that provides material for proficiency testing. The material contained 40,000 geq of HIV-1 subtype B per ml of plasma.

A panel that included subtypes A to F of HIV-1 group M was purchased from the National Institute for Biological Standardization and Control, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom.

All sample materials were diluted in pretested plasma pooled from 96 HIV-1-negative patients.

Seroconversion panels.

Two HIV-1 seroconversion panels were purchased from BioClinical Partners, Inc., Franklin, Mass. The patient identification numbers were 60722 and 62238. All material had been pretested with PRISM and AXSYM automated anti-HIV-1/2 assays (Abbott, Inc., Abbott Park, Ill.).

The viral loads of the samples were quantified with the Roche Amplicor Monitor HIV-1 RT-PCR assay system for patient 62238 and with an independent quantitative RT-PCR system for patient 60722. The sensitivity limits of the quantitative PCR assays were 400 and 100 geq/ml, respectively.

Dilution buffer for Armored RNA phages.

The TSM Armored RNA dilution buffer contained 10 mM Tris (pH 7.0), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.3% sodium azide, and 0.1% bovine gelatin (tissue culture grade). All substances were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany.

Nucleic acid extraction.

By using the viral RNA kit from Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, 100 μl of serum was processed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the elution of RNA, the columns were incubated with 75 μl of RNase-free water at 80°C. Elutes were stored at 4°C until analysis.

Plasma pooling and virus concentration.

After pooling of 100-μl aliquots of 96 blood donor samples on an automated pipetting station (Genesis; TECAN, Crailsheim, Germany), the complete 9.6 ml was centrifuged at 48,000 × g for 60 min. The supernatant was decanted and the virus pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of water. Further procedures were the same as those used for the plasma samples from single donors (18).

Primer and probe design.

Oligonucleotides were designed with Primer Express software, supplied by Perkin-Elmer, Weiterstadt, Germany. The degree of nucleotide sequence homology of all oligonucleotides to sequences other than the HIV-1 sequence was checked by using the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases and the BLAST algorithm (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST), which searches the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases.

Oligonucleotides in screening assay.

Primers cdis (ATC AAG CAG CCA TGC AAA TGT T and ACC AGG CAG CTA TGC AAA TGT T, equal amounts) and cdia (TG AAG GGT ACT AGT AGT TCC TGC TAT GTC and CTG AAG GGT ACT AGT AGT TCC TGC TAT ATC; equal amounts) were used to amplify a conserved 152-bp region spanning nucleotides 578 to 730 of the HIV-1 subtype B gag gene (the numbering is according to the Los Alamos National Laboratory HIV-1 consensus sequence). Probe cdso29 (ACC ATC AAT GAG GAA GCT GCA GAA TGG GA; positions 607 to 636) was used to detect HIV-1 PCR products. It was labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) at its 5′ end and 6-carboxy-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) at its 3′ end. Probe cdsti (ACG ACG GAC CAC ACT GAC CAG TCA) was used to detect an alternative probe binding site in the internal control sequence, which had been generated by replacement of nucleotides 605 to 637 by site-directed mutagenesis. It was labeled with 6-carboxy-4,7,2′,7′-tetrachlorofluorescein (TET) at its 5′ end and TAMRA at its 3′ end. Both of the probes were phosphorylated at their 3′ ends to prevent elongation during PCR.

Construction of internal control sequence.

Moloney murine leukemia virus Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used for synthesis of cDNA from HIV-1 subtype B RNA, according to the manufacturer's instructions, with primer Bas (GT TCC TGA AGG GTA CTA GTA GTT CCT GCT ATG TC) as an RT primer. Primers As (G CTT TCA GCC CAG AAG TAA TAC CCA TG) and Bas were used to amplify a 307-bp fragment that included genome positions 485 to 729. Gene splicing by overlap extension was carried out for construction of an internal control sequence (5, 7, 19) by using primers Aas (CTC TGG TAG TTA CTC CTT CGA CGT CTT ACC CTA TTT TAA CAT TTG CAT GGC TGC TTG ATG) and Bs (TAG GGT AAG ACG TCG AAG GAG TAA CTA CCA GAG AGA TTG CAT CCA GTG CAT GCA GG) to introduce an alternative probe binding site into the PCR product at nucleotide positions 605 to 637. The resulting sequence constructs were cloned into pCR II vectors (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) to generate plasmid pHIVSTD1.11. The integrities of the plasmid insert sequences, including confirmation of the presence of the alternative probe binding site, were confirmed with the Taq dye deoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer) and an ABI 310 automatic DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer S400 (GCT TTC AGC CCA GAA GTA ATA CCC ATG; nucleotides 485 to 511) was used as a sequencing primer. Packaging of internal control RNA into MS2 coliphages was performed by B. Pasloske, Ambion, Inc., Austin, Tex., with plasmid pHIVSTD1.11 as the template. The preparation procedure and the properties of the Armored RNA have been described previously (14). The Armored RNA stock solution contained 1014 particles per ml after preparation. For use as an internal control sequence, Armored RNA was spiked into plasma or resuspended virus pellets before nucleic acid extraction. The Armored RNA solution was custom designed for this work and is not identical to a similar product available from the same company.

5′-Nuclease HIV-1 RT-PCR.

PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μl containing 50 mM KCl; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); 0.01 mM EDTA; 60 nM 6-carboxy-x-rhodamine; 0.2% (vol/vol) polyethylene glycol 6000 (Fluka Chemicals, Munich, Germany); 0.05% bovine gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich); 3 mM MgCl2; dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP each at a concentration of 200 μM; primers cdis and cdia each at a concentration of 400 nM; 300 nM probe cdso29; 100 nM probe cdsti; 6 U of RNase-out RNase inhibitor; 6 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus Superscript reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies); and 0.75 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase. A total of 10 μl of nucleic acid extract was added to complete the reaction volume of 25 μl. Thermal cycling in a Perkin-Elmer 7700 thermal cycler involved preincubation at 40°C for 20 min, denaturation at 95°C for 7 min, 10 cycles of 95°C for 35 s and 62°C for 45 s with an annealing temperature decrement of 0.2°C per cycle, and 40 cycles of 93°C for 10 s and 58°C for 30 s with an annealing temperature increment of 0.2°C per cycle. Calculation and interpretation of fluorescence data either during or immediately after PCR have been described previously (5). A reaction was considered positive for wild-type HIV sequences when there was a signal from the FAM emission wavelength (518 nm), negative when there was a signal from the TET emission wavelength only (538 nm), and nonvalid when there was no signal. Reagents were purchased from Perkin-Elmer unless stated otherwise. The contamination precautions of Kwok and Higuchi were strictly complied with (11).

Statistical analysis.

The relationship between the proportion of 31 (direct testing) or 24 (testing of pooled samples) positive samples in replicate determinations with different concentrations of HIV-1 RNA as inputs was examined by probit analysis as a model for nonlinear regression (6). The analysis was performed with the Statgraphics plus (version 5.0) software package (Statistical Graphics Corp.).

RESULTS

Sensitivity and specificity for HIV-1 in plasma samples from single patients and sensitivity for various HIV-1 subtypes.

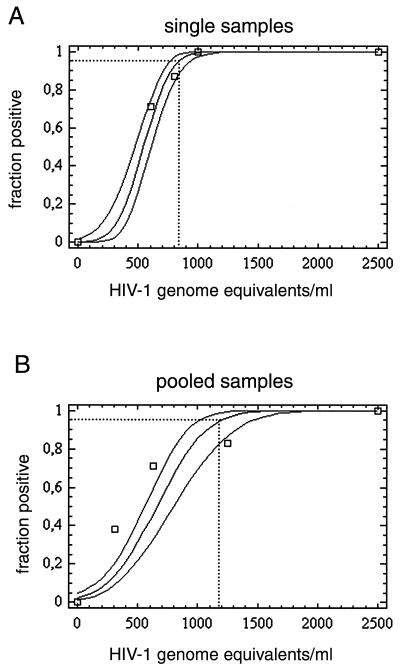

To determine the analytical sensitivity of the assay, we used plasma from a national proficiency study in which the HIV-1 subtype B load was quantified. The plasma was diluted in pooled negative plasma to 2,500, 1,000, 800, and 600 geq/ml for replicate amplification reactions by the protocol given in the Materials and Methods section. Thirty-one replicate reactions were performed with each RNA input concentration on 2 different days to minimize the effect of handling errors. The proportions of positive results obtained for each input concentration were subjected to probit regression analysis. The software determined a continuous 95% confidence interval (CI) of the probability that a positive result would be achieved at any given input concentration within the concentration range of the experiment. Table 1 summarizes the experimental results, and Fig. 1A depicts the results of probit analysis. The concentration at which 95% of results are expected to be positive was calculated to be 831 geq/ml (95% CI, 759 to 936 geq/ml). The percent deviance (for the proportion of samples with positive results) explained by the model was 99.273, proving the adequacy of the model.

TABLE 1.

Analytical sensitivity for plasma samples from single donorsa

| HIV-1 load (geq/ml of plasma) | Proportion positiveb

|

Total % positive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | ||

| 2,500 | 16/16 | 15/15 | 100 |

| 1,000 | 16/16 | 15/15 | 100 |

| 800 | 15/16 | 12/15 | 87 |

| 600 | 12/16 | 10/15 | 71 |

| 0 | 0/8 | 0/8 | 0 |

Assays were performed on 2 successive days, and dilution series were prepared with two different stocks. RNA was extracted directly from 100 μl plasma from each dilution step, and 10 μl of the 75-μl nucleic acid extract was analyzed as described in the text.

The values represent the number of samples with positive PCR results/total number of samples for which reactions were performed.

FIG. 1.

Predicted proportion of positive amplification results versus the input concentration of HIV-1 RNA in replicate reactions, as determined by probit regression analysis. Dotted lines, 95% probability of a positive result. (A) Direct testing of plasma samples from single patients. The datum points represent the RNA input concentrations given in Table 1. (B) Testing of plasma consisting of pools of plasma from 96 blood donors. The datum points represent the RNA input concentrations of a single positive sample in a pool given in Table 3.

To determine the capability of the assay to detect HIV-1 isolates from various clades, a subtype reference panel was tested by the preparation procedure used for plasma samples from single patients. Samples infected with HIV-1 clades A, B, C, D, E, and F all tested positive. The viral loads for the panel were not provided.

For a very preliminary determination of clinical sensitivity, plasma samples from 39 randomly selected German patients with HIV-1 viremia (confirmed by the standard protocol with Roche Amplicor Monitor system [version 1.5]) were tested by the TaqMan HIV-1 RT-PCR by using the preparation procedure described above for plasma samples from single patients. RNA could be detected in the plasma of 36 of 39 patients (data not shown), resulting in a sensitivity of 92.3% (95% CI, 84 to 100%). The viral loads in the three samples that tested negative were 800, 400, and <400 (below the quantitation range) geq/ml, respectively. In the samples that contained HIV-1 at 800 and 400 geq/ml, RNA could be detected upon retesting.

Implementation of Armored RNA internal control sequence.

For implementation of an internal amplification control reaction, which would be useful for continuous monitoring of the sample preparation process, we determined the lowest possible number of copies of Armored RNA internal control phages necessary to avoid detection failures due to statistical distribution effects (Poisson distribution). We spiked decreasing amounts of Armored RNA diluted in TSM buffer into 100 μl of plasma before nucleic acid extraction. Nucleic acid extracts were amplified by the PCR protocol given above. Table 2 summarizes the results.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity for Armored RNA internal control phagesa

| No. of aRNA phages/100 μl of plasma | No. of aRNA phages per PCRb | Proportion positivec |

|---|---|---|

| 1,125 | 150 | 8/8 |

| 750 | 100 | 8/8 |

| 375 | 50 | 8/8 |

| 187 | 25 | 7/8 |

| 93 | 12.5 | 3/8 |

| 46 | 6.25 | 1/8 |

| 0 | 0 | 0/8 |

The indicated amount of Armored RNA (aRNA) phages was spiked into 100 μl of HIV-1-negative plasma prior to extraction. After elution with 75 μl of water, 10 μl of nucleic acid extract was analyzed by PCR.

The extraction efficiency supposedly equals 100%.

The values represent the number of samples with positive PCR results/total number of samples for which reactions were performed.

To ensure that the Armored RNA internal control sequence does not suppress amplification of wild-type HIV RNA in routine screening tests, we spiked pooled plasma containing 2,500 geq of HIV-1 subtype B/ml with increasing amounts of Armored RNA phages. For each Armored RNA concentration step, RNA was extracted from plasma four times in parallel; each nucleic acid extract was amplified twice in parallel. With up to 11,500 copies of Armored RNA per ml of plasma, no failure of detection of wild-type HIV RNA occurred in eight of eight PCRs (data not shown). On the basis of this result, 7,500 particles of Armored RNA internal control per ml of plasma, which corresponds to 750 particles per nucleic acid extraction or 100 RNA copies per PCR, was used as an internal amplification control for routine screening of plasma from blood donors.

Sensitivity for pooled plasma samples from 96 donors.

Analytical sensitivity after pooling of 96 plasma samples from blood donors was determined with the same quantified HIV-1 subtype B-positive plasma sample mentioned above. Dilution series of HIV-1 subtype B-positive plasma were prepared independently on 3 different days by three different technicians. Samples from each of six concentration steps were then spiked into eight replicate plasma pools of 9.5 ml each. Viral particles were concentrated from pools as described in the Materials and Methods section. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μl of water, inoculated with 750 particles of the Armored RNA internal control, and extracted with the Qiagen viral RNA kit. The proportions of 24 replicate reactions positive at each input RNA concentration were subjected to probit regression analysis as described above. Table 3 summarizes the experimental results, and Fig. 1B shows the results of probit analysis. The RNA input concentration at which 95% of tests are expected to be positive was 1,195 geq/ml (95% CI, 1,014 to 1,470 geq/ml). Notably, the datum point obtained for 1,250 geq/ml appeared to be an outlier, giving a falsely low value. The zero value was overweighted by a factor of 10 to obtain a probit curve that fit the data instead of excluding the outlier, which otherwise would have caused a bias toward a lower sensitivity limit. The percent deviance (for the proportion of positive samples) explained by the model was 86.32.

TABLE 3.

Analytical sensitivity for HIV-1 after pooling of plasma samples from 96 donorsa

| HIV-1 subtype B geq/ml of spiked individual donor plasma | HIV-1 subtype B geq/virus pelletb | HIV-1 subtype B geq/PCRc | Proportion positived

|

Total % positive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | ||||

| 10,000 | 1,000 | 200 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 100 |

| 5,000 | 500 | 100 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 100 |

| 2,500 | 250 | 50 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 | 100 |

| 1,250 | 125 | 25 | 8/8 | 6/8 | 6/8 | 83 |

| 625 | 62 | 12.5 | 7/8 | 5/8 | 5/8 | 71 |

| 312 | 31 | 6.25 | 5/8 | 1/8 | 3/8 | 38 |

Pools of plasma from 95 donors that tested negative (95 × 100 μl) were spiked with an identical volume (100 μl) containing the indicated number of genome equivalents of an externally quantified reference plasma. The spiked pools were centrifuged, and viral pellets were spiked with 750 particles of Armored RNA internal control phages and were subjected to nucleic acid extraction. A total of 10 μl from 75 μl of nucleic acid extract was analyzed by PCR.

Concentrated from a pool of samples from 96 donors. The concentration efficiency supposedly equals 100% (approximately).

The concentration and extraction efficiencies supposedly equal 100% (approximately).

The values represent the number of samples with positive reactions/total number of samples for which reactions were performed.

Technical feasibility and specificity of procedure for day-to-day application.

To assess whether the TaqMan HIV-1 PCR is technically suitable for day-to-day application, the assay was used in parallel with our established blood donor screening PCR (18) to screen pools of plasma in a 3-month test period. During this time, 1,791 pools were tested in 89 individual test runs, with a maximum of 4,000 individual plasma samples included in one run. In each run, two low-positive control plasma samples (2,500 geq of HIV-1 RNA per ml) were included, one of which was treated as single patient plasma sample and the other of which was inoculated into a negative plasma pool and concentrated as described above. All of the resulting 178 positive controls were detected.

In 51 of 1,791 reactions the internal control failed to be amplified, with the result being that 2.85% (95% CI, 2.13 to 3.73%) of pools had to be retested. Upon retesting of the same nucleic acid extract, the internal control was detected in 45 of these reactions. In the remaining six plasma pools the internal control was repeatedly undetectable. Thus, inhibitory substances were present in or an insufficient amount of Armored RNA was recovered from only 0.34% (95% CI, 0.12 to 0.73%) of plasma pools tested. When the complete preparation process for these remaining six pools from which no internal control was recovered was repeated starting from the pooling of the original samples, the internal control was detected in all pools. Consequently, inhibitory substances did not originate from patient plasma but came from the sample preparation process.

Five false-positive reactions occurred among the 1,791 pools tested. The results for all five pools could be resolved to be true negative by four independent negative retests: two by the same method and two by the established routine PCR. The specificity was therefore 99.72% (95% CI, 99.48 to 99.97%). To complement the specificity data obtained from the trial period, the oligonucleotides used in the assay were tested for their alignments with sequences in DNA databases. No significant primer or probe sequence homologies other than with HIV or HIV-human fusion sequences were found with sequences in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ databases by a search with the BLAST program, available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website.

Detection of low levels of HIV-1 RNA in early infection.

To compare the performance of our HIV-1 RT-PCR to those of established quantitative PCR systems, we tested two different seroconversion panels from U.S. plasma donors in which the HIV load had been quantified by PCR. An aliquot of 100 μl of plasma from each patient on each individual bleeding date was inoculated into a pool of plasma from 95 individuals pretested and found to be HIV-1 negative by RT-PCR. The total volume of 9.6 ml was processed under routine conditions for screening of plasma from blood donors by PCR, as described above. The results were also compared to those obtained by the Abbott PRISM and AXSYM anti-HIV-1/2 assays and provided by the supplier of the seroconversion panels. These assays are commonly used by blood transfusion services. Viral loads and the data obtained by serologic testing of each sample are summarized in Table 4. Viral RNA could not be detected by our pooling assay in one low-positive sample (patient 62238; bleed date, 9 September 1996) that contained 1,180 geq/ml of plasma, but viral RNA was detected with the Roche Amplicor Monitor HIV-1 RT-PCR assay system upon testing of a single sample. For patients 60772 and 62238, PCR detection of HIV-1 RNA was achieved 9 and 12 days earlier, respectively, than anti-HIV-1 detection by both serologic assays.

TABLE 4.

Detection of HIV-1 in early infectiona

| Donor | Bleed date (mo/day/yr) | Result of 5′-nuclease PCR with pooled samplesb | Viral load (geq/ml) by quantitative PCRc | s/cod

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRISM | AXSYM | ||||

| 60772 | 11/08/95 | − | <100 | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| 11/13/95 | −/− | <100 | 0.22 | 0.37 | |

| 11/15/95 | −/− | <100 | 0.23 | 0.24 | |

| 11/20/95 | +/+ | 15,000 | 0.22 | 0.27 | |

| 11/22/95 | + | 120,000 | 0.56 | 0.30 | |

| 11/27/95 | + | >1,000,000 | 0.48 | 0.92 | |

| 11/29/95 | + | >1,000,000 | 3.22 | 3.01 | |

| 12/05/95 | + | 450,000 | 18.64 | 7.40 | |

| 62238 | 08/29/96 | − | <400 | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| 09/03/96 | −/− | <400 | 0.24 | 0.31 | |

| 09/09/96 | −/− | 1,180 | 0.22 | 0.33 | |

| 09/11/96 | +/+ | 3,930 | 0.22 | 0.33 | |

| 09/16/96 | + | 265,000 | 0.27 | 0.38 | |

| 09/18/96 | + | 413,000 | 0.24 | 0.44 | |

| 09/23/96 | + | 295,000 | 4.41 | 4.81 | |

| 09/25/96 | + | 447,000 | 8.13 | 5.75 | |

A total of 100 μl of plasma from each bleed date was spiked into a pool of samples from 95 donors that tested negative and analyzed under routine screening conditions with an internal control.

Replicate results represent those for two independent runs, including pooling, concentration, extraction, and PCR.

For patient 60772, quantitative in-house RT-PCR; for patient 62238, Roche Monitor quantitative RT-PCR. Data were provided by BioClinical Partners, Inc.

s/co, signal to cutoff (s/co) ratios for the PRISM and AXSYM assays. Ratios >1.0 are considered reactive. Data were provided by BioClinical Partners, Inc.

DISCUSSION

High-throughput screening for HIV-1 by RT-PCR requires handling by experienced laboratory personnel and tremendous laboratory effort. In particular, the risk of contamination during product detection after thermal cycling restricts diagnostic PCRs to experienced laboratories.

Our HIV-1 TaqMan 5′-nuclease PCR provides a screening assay that does not require time-consuming and contamination-prone post-PCR processing steps; reaction vials stay closed after amplification and are discarded, with no need to open them.

In addition to contamination, unspecific by-products infrequently generated by PCR can contribute to false-positive screening results by misinterpretation of DNA bands in an agarose gel (18). These errors can be eliminated by hybridization with a specific probe. However, classical hybridization procedures, like Southern blotting or dot blotting, increase the assay time and the contamination risk even more. The TaqMan 5′-nuclease PCR overcomes this problem by in-tube hybridization, which is suitable for high-throughput screening. As a result, the specificity of 99.72% that was achieved is superior to that of our established routine method (18).

Use of an internal control sequence enables verification of the sensitivity for each individual reaction tube, while it circumvents the need for additional labor-intensive and costly external control reactions (3, 10, 17). Because the target DNA sequences with different base compositions undergo different amplification conditions in the PCR (9), we used a competitive internal control sequence to monitor PCR failures. The base composition of the internal control sequence including the primer binding sites is nearly identical to that of wild-type HIV-1 RNA; hence, the amplification properties for the internal control sequence exactly reflect those of the wild type. Packaging of the internal control RNA in a phage (Armored RNA) makes the control RNA resistant to RNase degradation (14). Because the Armored RNA can be spiked into donor plasma like a virus without being degraded by ubiquitous RNases, this format enables monitoring of the complete nucleic acid extraction and amplification process for each specimen. The concentration of Armored RNA inoculated into each sample is about 10 times the detection limit of the assay. Thus, a 10-fold drop in efficiency of any step of the preparation or amplification procedure will likely be detected. The observed proportion of tests that had to be repeated due to failure of the internal control (2.85%) does not prohibit the day-to-day application of the assay. It appeared that the amplification part of the procedure is more susceptible to errors than the preparation part of the procedure, since only 11.8% of controls that failed to be amplified were repeatedly negative when the same RNA extract was retested. In contrast to earlier findings from tests with single samples (17), confirmed failure of detection resulted from the nucleic acid preparation process and not from the samples themselves. This is attributable to the fact that each patient plasma sample is diluted by inclusion in a pool of 96 samples; any inhibitors possibly present in single samples are similarly diluted.

The analytical sensitivity for testing of plasma from single donors and pools of plasma has been determined by probit regression analysis of the proportions of samples positive in replicate reactions with different input concentrations. This calculation has proved adequate for description of the sensitivity limits of PCR assays (5, 21). Expressed as the RNA input concentration at which ≥95% of the test reactions are positive, sensitivity limits were 831 geq/ml for plasma from single donors and 1,195 geq/ml for pooled plasma (with respect to a single positive sample in a pool). The small reduction in sensitivity observed despite the pooling of plasma is attributable to the high efficiency of concentration of HIV-1 particles by centrifugation. It is consistent with the similarly high concentration efficiency achieved by the ultrasensitive protocol of the Roche Amplicor Monitor assay. By the Roche assay, samples are centrifuged at only 20,000 × g for 1 h. We used 48,000 × g instead because the same pools are used to test for hepatitis C and B viruses, and concentration of hepatitis C virus in particular has proved to require high centrifugation forces (personal observation).

It has been shown by others that screening of plasma from blood donors by PCR with a sensitivity limit in the range of 103 geq/ml can significantly reduce the window during which HIV-1 infection fails to be diagnosed by serological assays (16, 23). Murthy et al. have indicated that this may be sufficient to completely eliminate the window (13). The reductions of the window periods for two seroconverting patients obtained in the present study (9 and 12 days, respectively) are in concordance with the calculations of Schreiber et al., who proposed a reduction of 11 days (20).

Preliminary data on the clinical sensitivity of our assay in its intended application (testing of German blood donors) have been obtained with a small panel of plasma samples from German HIV-1 RNA-positive patients. The low viral loads (≤800 geq/ml) in the three samples for which the assay failed to detect HIV-1 RNA, as well as the viral load in one sample from the seroconversion panels for which the assay failed to detect HIV-1 RNA (1,180 geq/ml), are in concordance with the analytical sensitivity limits determined for our assay. This also implies that false-negative reactions due to primer-probe mismatches occurred in none of the remaining samples. The observation that HIV-1 RNA was detected in plasma samples containing subtypes A, B, C, D, E, and F is another indicator of the good diagnostic performance of the assay. However, for a comprehensive determination of the clinical sensitivity of the assay, a large validation study is required. This would include comparative testing of various preseroconversion plasma panels by our method and established commercial procedures, e.g., the Roche AmpliScreen or GenProbe TIGRIS assays. Furthermore, testing of low-positive samples from patients infected with HIV-1 clades that are rare in Germany, including HIV-1 subtype O, will be necessary. Moreover, validation of the assay for the quantification of viral loads in patients, which should be feasible, given the technical possibilities of real-time PCR, may be profitable for clinical laboratories.

However, the data obtained in the present pilot feasibility study are promising with respect to clinical application of the assay. Our data suggest that recent advances in PCR technology make it feasible to screen for viral pathogens like HIV-1 with high sample throughput without being dependent on commercially provided testing formats. To our knowledge, this is the first noncommercial TaqMan HIV-1 RT-PCR assay available for this purpose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to B. Rüster for helpful discussions and to C. Weis and S. Buhr for expert technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Busch M P, Lee L L, Satten G A, Henrard D R, Farzadegan H, Nelson K E, Read S, Dodd R Y, Petersen L R. Time course of detection of viral and serologic markers preceding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion: implications for screening of blood and tissue donors. Transfusion. 1995;35:91–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35295125745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark S J, Saag M S, Decker W D, Campbell-Hill S, Roberson J L, Veldkamp P J, Kappes J C, Hahn B H, Shaw G M. High titers of cytopathic virus in plasma of patients with symptomatic primary HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:954–960. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104043241404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cone R W, Hobson A C, Meei-Li W H. Coamplified positive control detects inhibition of polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3185–3189. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3185-3189.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daar E S, Moudgil T, Mayer R D, Ho D D. Transient high levels of viremia in patients with primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:961–964. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104043241405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drosten C, Weber M, Seifried E, Roth W K. Evaluation of a new PCR assay with competitive internal control sequence for blood donor screening. Transfusion. 2000;40:718–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40060718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finney D J. Probit analysis. 3rd ed. London, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Higuchi R. Using PCR to engineer DNA. In: Ehrlich H A, editor. PCR technology. Principles and applications for DNA amplification. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1989. pp. 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holland P M, Abramson R D, Watson R, Gelfand D H. Detection of specific polymerase chain reaction product by utilizing the 5′ to 3′-exonuclease activity of Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7276–7280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Innis M A, Gelfand D H. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1990. Optimization of PCRs. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kox L F, Rhienthong D, Miranda A M, Udomsantisuk N, Ellis K, van Leeuwen J, van Heusden S, Kuijper S, Kolk A H. A more reliable PCR for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:672–678. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.672-678.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwok S, Higuchi R. Avoiding false positives with PCR. Nature. 1989;339:237–238. doi: 10.1038/339237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livak K J, Flood S J, Marmaro J, Giusti W, Deetz K. Oligonucleotides with fluorescent dyes at opposite ends provide a quenched probe system useful for detecting PCR product and nucleic acid hybridization. PCR Methods Appl. 1995;4:357–362. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.6.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murthy K K, Henrard D R, Eichberg J W, Cobb K E, Busch M P, Allain J P, Alter H J. Redefining the HIV-infectious window period in the chimpanzee model: evidence to suggest that viral nucleic acid testing can prevent blood-borne transmission. Transfusion. 1999;39:688–693. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39070688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasloske B L, Walkerpeach C R, Obermoeller R D, Winkler M, DuBois D B. Armored RNA technology for production of ribonuclease-resistant viral RNA control and standards. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3590–3594. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3590-3594.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petersen L R, Satten G A, Dodd R, Busch M, Kleinman S, Grindon A, Lenes B. Duration of time from onset of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection to development of detectable antibody. Transfusion. 1994;34:283–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1994.34494233574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piatak M, Jr, Saag M S, Yang L C, Clark S J, Kappes J C, Luk K C, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Lifson J D. High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science. 1993;259:1749–1754. doi: 10.1126/science.8096089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenstraus M, Wang Z, Chang S Y, DeBonville D, Spadoro J P. An internal control for routine diagnostic PCR: design, properties, and effect on clinical performance. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:191–197. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.191-197.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth W K, Weber M, Seifried E. Feasibility and efficacy of routine PCR screening of plasma from donors for hepatitis C virus, hepatitis B virus, and HIV-1 in a blood bank setting. Lancet. 1999;353:359–363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rüster B, Zeuzem S, Roth W K. Quantification of hepatitis C virus by competitive reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction using a modified hepatitis C virus transcript. Anal Biochem. 1995;224:597–600. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schreiber G B, Busch M P, Kleinmann S H, Korelitz J J. The risk of transfusion-transmitted viral infections. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smieja M, Mahony J B, Goldsmith C H, Chong S, Petrich A, Chernesky M. Replicate PCR testing and probit analysis for detection and quantitation of Chlamydia pneumoniae in clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1796–1801. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.1796-1801.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Förster T. Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Ann Physics (Leipzig) 1948;2:55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward J W, Holmberg S D, Allen J R, Cohn D L, Critchley S E, Kleinman S H, Lenes B A, Ravenholt O, Davis J R, Quinn M G, Jaffe H W. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by blood transfusions screened as negative for HIV antibody. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:473–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198802253180803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]