Abstract

Supervised fieldwork is a critical component in the training of future behavior analysts. A growing body of literature describes best practices in behavior-analytic supervision, yet the trainee is rarely referenced. Additional resources delineating the expectations and suggested practices of the trainee are warranted. The current article describes recommended activities for the behavior-analytic trainee using practice guidelines for the supervisor offered by Sellers, Valentino, and LeBlanc (2016c). This work extends the current literature by outlining the role of the trainee in the supervisory relationship and supervised fieldwork experience.

Keywords: fieldwork, individual supervision, trainee, supervision

Recommended practices for effective behavior-analytic supervision have received growing interest in the past decade (e.g., Andzik & Kranak, 2020; Sellers, Alai-Rosales, & MacDonald, 2016a; Sellers, LeBlanc, & Valentino, 2016b; Sellers et al., 2016c; Sellers, Valentino, Landon, & Aiello, 2019; Valentino, LeBlanc, & Sellers, 2016). For example, Sellers et al. (2016c) outlined five recommended practice guidelines for individual supervision that should underlie the majority of supervisory activities. These guidelines included (a) establishing an effective supervisor–trainee relationship, (b) establishing a plan for structured supervision content and competence evaluation, (c) evaluating the effects of supervision, (d) incorporating ethics and professional development into supervision, and (e) continuing the professional relationship postcertification. Although most of these guidelines make some reference to the supervisory relationship, the role of the trainee in this process is rarely discussed. Indeed, many of the resources in the extant literature are designed to guide the practice of the supervisor, which is logical as the supervisor is most likely to read these journals. Nevertheless, in doing so, the field may be misrepresenting supervision as something that is done to the trainee.

Descriptions of supervision in the behavior-analytic literature place particular emphasis on the responsibility of behavior analysts in the supervision process for shaping the skills of the trainee (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2020d; Turner, 2017). Reference to the trainee in this literature is rarely made, although one exception exists (Kazemi et al., 2019). Some authors have characterized supervision as an active and/or collaborative process (Turner, 2017; Turner et al., 2016), which might allude to the role of the trainee, yet the BACB makes no reference to the trainee when describing the supervisory relationship (e.g., BACB, 2016, 2020b, d). As a complement to this position, the American Psychological Association (APA) defines supervision as “a distinct professional practice employing a collaborative relationship [emphasis added] that has both facilitative and evaluative components, that extends over time, which has the goals of enhancing the professional competence and science-informed practice” (APA, 2014, p. 2). Thus, it is proposed here that the literature on behavior-analytic supervision should emphasize the role and expectations of the trainee in the supervisory relationship. In doing so, the behavior-analytic trainee might enter into these supervisory relationships more prepared to benefit from the experience.

The purpose of the current article is to serve as an overview of behavioral expectations and recommendations for the trainee, which are aligned with the guidelines outlined by Sellers et al. (2016c) for the supervisor. Each guideline is followed by relevant codes from the Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2016). Codes from the recently published Ethics Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2020b) will also be included, which will take effect as of 2022. Although not an exhaustive list, the reference to specific codes is intended to illustrate the coherence of the expectations described in this article and those provided by the BACB. Additional codes may be relevant, and the trainee should consult the current version of the BACB ethics code (BACB, 2016, 2020b) frequently throughout their experience.

Recommended Practice Guideline 1: Establish and Maintain an Effective Supervisor–Trainee Relationship

Before Supervision Contract

Although signing the supervision contract will define the formal beginning of the supervisory relationship, there are a few things that the trainee should do beforehand (see the Appendix). First and foremost, they should be aware of the role of supervision and clinical training in their development as a behavior analyst. Supervision should be a top priority in their training, as it is the opportunity to develop foundational skills in behavior-analytic practice. A critical consideration for supervisors entering into a new supervisory relationship is their current caseload as it relates to the ability to provide effective supervision (Sellers et al., 2019). The trainee should discuss their supervisor’s current caseload and supervisory volume. This should include an explicit discussion of the number of contacts that will occur during each supervisory period and the supervisor’s availability to support the trainee (Turner et al., 2016). Likewise, the trainee should consider their current workload, past supervision experience, and proficiency with relevant items in the Task List for Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs; BACB, 2017) when determining their ability to benefit from supervision. Instances in which the supervisor has a high supervisory volume and the trainee has limited experience in applied settings may not be optimal. Conversely, if the trainee is more advanced, a supervisor with a high supervisory volume and large caseload may help them develop greater independence and proficiency as a behavior analyst. In addition to discussing the supervisor’s current caseload and supervisory volume, another critical consideration for the trainee is the supervisor’s current standing with the BACB. Trainees should consider finding their supervisor’s information on the BACB registry (https://www.bacb.com/services/o.php?page=101135) to confirm that they meet the BACB’s supervision requirements and to determine whether any disciplinary actions have been raised against their supervisor. Trainees may also search disciplinary information by state using the BACB Disciplinary Actions webpage (https://www.bacb.com/services/o.php?page=100180). If there are any discrepancies noted, the trainee should reflect on how their training may be impacted and discuss it with their supervisor.

The BACB’s Fieldwork Standards describe requirements for trainees to begin their fieldwork experience. The trainee should review the BACB requirements, as well as those that may exist within their academic program, to ensure that all have been satisfied and they are eligible to begin supervised fieldwork. The trainee should also be familiar with the current BCBA Task List (BACB, 2017) and consider their mastery of the Task List items. The information gleaned from this sort of self-assessment should help the trainee identify their goals, strengths, and weaknesses, which may then help them identify specific experiences that are coherent with the supervision training program. An explicit discussion about the trainee’s needs and the experience available at the training site should occur before the supervision contract is signed. Doing so may prevent future issues in the supervisory relationship. Other documents that trainees should download and review prior to beginning the fieldwork experience include the current version of the BACB’s ethics code (BACB, 2016, 2020b), the BCBA Handbook (BACB, 2020a), and the Supervisor Training Curriculum (BACB, 2020e). These and other documents can be found on the BACB website (BACB, n.d.), which the trainee should also become familiar with before starting their training. Generally, the trainee’s familiarity with their supervisor, the practice of behavior analysis, and the BACB’s current standards and requirements for fieldwork experience will aid the trainee when entering into a new supervisory relationship.

Contracts

The BACB’s Fieldwork Standards require that the trainee and supervisor both thoroughly review and discuss a supervision contract (BACB, 2020d). This contract must be signed before the trainee begins to accrue experience hours. Some sites or supervisors will have a standard supervision contract, but the trainee should still review the document before signing. The trainee should take the time to independently review the contract and make note of any vague or confusing aspects to discuss with their supervisor. If the supervisor does not allow for adequate time to review the contract or provide the trainee with an opportunity to ask questions, then the trainee should politely request additional time, details, or examples as needed. Politely advocating for these components of supervision from the outset will not only ensure that the trainee is well informed but also illustrate the trainee’s investment in the supervisory relationship.

The supervision contract must include certain components, but some flexibility is warranted with regard to either party’s preference for delineating responsibilities or expectations. Sellers et al. (2016c) recommended that trainees identify specific training experiences that they would like to count toward fieldwork requirements. It may be the case, however, that the site or supervisor has an established supervision program that the trainee will be expected to complete. In these experiences, the trainee may have less input into the specific activities that will be included in their supervised experience. Nevertheless, the supervision contract should delineate the scope of activities to be included during fieldwork, and the trainee should consider sharing their goals, strengths, and weakness where applicable within the training curriculum so that the experience can be tailored to their specific needs. Relatedly, trainees should ask how often they will be evaluated and on what basis (see Guideline 2 for more details).

If a required component of the supervision contract is absent or poorly defined, the trainee should ask their supervisor about these components before signing the contract. In particular, they should ask about the conditions under which their supervisor will not sign the monthly Experience Verification Forms (EVFs) and other situations that could lead to the termination of the supervisory relationship (BACB, 2019a). No one enters into a supervisory relationship expecting it to end prematurely, but it is in the trainee’s best interest to determine what criteria are used to make these decisions. The supervision contract should explicitly state the conditions under which supervisors will not sign monthly EVFs or the final EVF at the end of the training experience. More information about contested experiences can be found on the BACB’s website (BACB, n.d.), including the Contested Experience Fieldwork Form. Once both parties have signed the supervision contract, the trainee should retain a copy for their personal records for at least 7 years following the last meeting with their supervisor (BACB, 2020d).

Clear Expectations

The BACB’s Fieldwork Standards (BACB, 2020d) and ethics code (BACB, 2016, 2020b) should be used to guide the content of the trainee’s supervision and training experiences. Specifically, the BACB endorses that individual supervision should be behavior analytic, effective, and ethics based and meet the requirements for certification (BACB, 2016, 2019a, 2020b). These expectations of supervision should remain even when experience at the training site and the mode of supervision (Turner et al., 2016) change over time. For example, if the trainee is working with a new clinical population or in a new setting, supervision may commonly involve direct observation and immediate feedback. As the trainee advances, their role will likely change and include activities consistent with case conceptualization, treatment planning, consultation, and supervision of newer trainees. In these instances, the supervisor should continue to provide feedback to the trainee, though this may include fewer direct observations and the feedback may be more delayed (Turner et al., 2016). Supervision meetings should also include topics not related to the direct implementation of services, including ethical dilemmas, treatment program development, and other challenges that may arise in behavior-analytic practice, to name a few.

Although the BACB has a number of materials used to guide training as a behavior analyst, there are other behaviors that will be expected of the trainee that are not explicitly identified in the Fieldwork Standards (BACB, 2020d) or Task List (BACB, 2017; e.g., Andzik & Kranak, 2020; Garza et al., 2018; Sellers et al., 2016b; Sellers et al., 2019). For example, Sellers et al. (2019) noted that a majority of supervisors reported measuring trainees’ interpersonal, time management, communication, organization, and prioritization skills in some way. The trainee should discuss their supervisor’s expectations for professional behaviors and share their strengths and weaknesses in those domains. One such professional repertoire includes skills to facilitate interactions and relationships with other trainees. Often, trainees will advance to serve in leadership roles in the training setting, and their interactions and relationships might change accordingly. Being thoughtful of these interactions and discussing how to best approach their evolving role may help the trainee successfully navigate these relationships in the future. With any of these professional skills, the trainee should make sure that they are aware of their supervisor’s expectations and be prepared to receive, and even solicit, feedback on their performance in these domains. Considerations for receiving feedback are discussed in Guideline 3, later in this article.

Some expectations of the trainee may be specific to a given clinical setting. These activities will still likely be relevant to the trainee’s future practice as a behavior analyst and may include developing instructional stimuli, using various computer programs, aiding in billing and insurance, or other administrative duties. The trainee should consider what other activities they may be required to complete at their training site and work with their supervisor to ensure that they are adequately trained to effectively perform all relevant tasks. Although some of these tasks may be less enjoyable than others, if they are relevant to the practice of the supervisor, the trainee should pursue experiences to develop competence in these areas as well. To note, although non-behavior-analytic activities may be required at the training site, such activities may not count toward the trainee’s experience hours. The trainee should meet with their supervisor and review the Fieldwork Standards to ensure that they are accruing at least the minimum number of experience and supervision hours each month when these activities are excluded.

The trainee should be aware of their supervisor’s expectations of them, while simultaneously being aware of what is expected of the supervisor by the BACB. One of the most common violations of the BACB Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (BACB, 2016) is the inadequate supervision and delegation of responsibilities in the supervisory relationship (BACB, 2018, as cited by Sellers et al., 2019). It is critical that the trainee is trained or directly supervised to complete all relevant tasks in their experience. Best practices in clinical training include four components: (a) instructions, (b) modeling, (c) rehearsal, and (d) feedback (Parsons et al., 2015). This program is called behavioral skills training (BST), and considerable research has demonstrated the efficacy of BST to train a variety of behavior-analytic repertoires (e.g., Cariveau et al., 2019; Iwata et al., 2000; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004; Weiss, 2005). If the trainee does not feel proficient in a given task, they may request more explicit instruction, modeling, opportunities to practice, or feedback from their supervisor. In doing so, the trainee is developing a valuable professional repertoire and ensuring that their supervisor is adhering to the BACB (, 2016; , 2020b) ethics code.

The division and types of tasks will likely change as the trainee progresses in their training. The trainee should share with their supervisor when they feel they have demonstrated competence, or do not feel competent, in various training activities. The supervisor may delegate tasks early in their relationship, but the trainee will likely be expected to complete more complex fieldwork activities independently as they gain more experience (Turner et al., 2016). Early and frequent communication with the supervisor regarding the trainee’s competence and confidence in their clinical role will allow the supervisor to tailor the experience to the trainee’s specific needs. Of course, the trainee’s confidence in a given domain should always be determined through objective assessment by their supervisor, although communicating when they would like to be evaluated may always be an option.

Finally, the trainee should discuss their supervisor’s expectations for documenting experience hours. For example, Sellers et al. (2019) recommended that supervisors complete monthly fieldwork documentation; however, some supervisors may expect that the trainee do so, and the supervisor will conduct reliability checks. Regardless, the trainee should verify that their experience forms are up to date and retain signed versions each month. Ultimately, reporting accurate and complete information on monthly forms and all other fieldwork experience documentation is the trainee’s responsibility, so setting a reminder or some other prompt each month to review these materials with the supervisor may be ideal (see the Appendix).

Creating a Positive and Committed Relationship

The trainee’s relationship with their supervisor will likely last several months. As with any relationship, efforts should continually be made to establish and maintain positive and respectful interactions within the supervisory relationship. Sellers et al. (2016c) recommended that supervisors be pleasant, caring, and consistently professional to convey their commitment to a positive relationship with the trainee. The same should be said for the trainee. It is important to recognize that whereas the supervisor plays an important role in shaping the trainee’s professional behavior, the trainee’s behavior within the context of the relationship will also shape the supervisor’s supervision practices. In fact, despite the trainee’s performance in other areas, these interpersonal and professional behaviors might be most readily observed by their supervisor (Bloom & Bell, 1979). It is typically recommended that these skills be explicitly measured, so the trainee should be aware that they may receive feedback on their interactions with their supervisors or other individuals in the training setting. Andzik and Kranak (2020) described a Needs Assessment and Checklist for Interpersonal Skills that may be valuable resources for the trainee to use for self-reflection, even if their performance in these areas is not being directly assessed by their supervisor. Developing competence in these interpersonal and professional behaviors will be expected in any professional setting, even when such behaviors are not explicitly endorsed. Further, interpersonal skills may lead to higher ratings of the trainee by their supervisor (Bloom & Bell, 1979).

The supervisory relationship will inherently differ from other relationships in the trainee’s life. The trainee will be expected to balance professional and interpersonal interactions with their supervisor, requiring that the trainee be thoughtful in how they approach the supervisory relationship. This may include their supervisor’s preference for communication modality (e.g., text message or email), interactions outside of the training setting (e.g., communication on weekends), and how they should reference their supervisor (e.g., first name or professional title). The trainee should discuss their supervisor’s preference in these and related domains. Further, the trainee might request information about past trainees whom the supervisor found to be exceptional. In doing so, relatively minor activities (e.g., adhering to deadlines) may be endorsed as having significant implications for the supervisory relationship. Respecting the supervisor’s preferences and being professional throughout their interactions will help maintain the positive context of their supervisory relationship.

Due to the complexity of the supervisory relationship, it is important for the trainee to recognize potential instances of multiple relationships, conflicts of interest, or even exploitative relationships (BACB, 2016, Codes 1.06–1.07; 2020b, Codes 1.11–1.14). The trainee should work with their supervisor to develop a plan for communication should any issues develop in the relationship. The first step for the trainee to resolving these issues is to bring the issues to their supervisor’s attention. Additional processes are available from the BACB and likely the trainee’s company or academic program. The trainee should be aware of resources and expectations to resolve issues in their supervisory relationship and communicate any concerns as early as possible so that their training is not affected.

The trainee should not limit discussions of their relationship with their supervisor to instances when issues arise. Instead, evaluations of their supervisory relationship should be a consistent point of discussion during supervision (see the Appendix). Sellers et al. (2019) noted that just over half of supervisors reported continuously evaluating the supervisory relationship. Given that the nature of their relationship will likely change as the trainee gains more experience, they should review their relationship at least as frequently as other regularly scheduled evaluations (see the Appendix). Sellers et al. (2019) suggested that the supervisory relationship be evaluated based on the frequency and structure of meetings, the supervision contract, feedback, the trainee’s needs, and both short- and long-term goals. The trainee should also reflect on their own behavior and consider how they may be positively or negatively impacting the supervisory relationship. Although research on self-monitoring for individuals receiving behavior-analytic supervision is limited, including self-monitoring in training packages has been effective for improving staff’s accuracy in implementing behavioral interventions (e.g., Petscher & Bailey, 2006; Plavnick et al., 2013). The trainee may use the Needs Assessment and Checklist for Interpersonal Skills (Andzik & Kranak, 2020) or some similar checklist to self-monitor their professional behavior in the training setting.

Relevant ethical codes for Guideline 1 are 1.04–1.07, 5.01–5.03, 5.05, 7.01, 10.05, and 10.06 (BACB, 2016), as well as 1.01–1.04, 1.06, 1.08–1.14, 2.08, 4.01–4.05, and 4.09 (BACB, 2020b).

Recommended Practice Guideline 2: Establish and Maintain a Plan for Structured Supervision Content and Competence Evaluation

The trainee should collaborate with their supervisor to develop a plan for covering aspects of the Task List (BACB, 2017) and other related content during their training experience. A generic plan may be ideal, as much of the content covered in supervision may be client specific, so adherence to a strict schedule may not be possible. In addition, the trainee may consider developing a system to record when particular content is discussed in supervision and align this content with those items defined in the Task List (BACB, 2017). Regardless, monitoring of this content should consistently occur throughout the supervisory relationship (see the Appendix).

The trainee should also discuss their supervisor’s expectations for supervision meetings. Supervisors might request that trainees develop and submit an agenda prior to each meeting (Sellers et al., 2016c), bring clinical graphs to discuss, provide summaries of relevant research, or practice role-playing a specific protocol. Developing a tentative agenda that includes questions or topics to discuss during their meetings is recommended, although the trainee should be flexible in case their supervisor has other feedback or content to discuss. In preparing for supervision meetings, the trainee should prioritize topics to ensure that questions pertinent to their clients’ needs are addressed first. Additionally, the trainee should consider preparing tentative answers to questions they plan to ask during their supervision meeting. Specifically, instead of asking “What should we do about X?” the trainee might consider making a recommendation first, and then requesting feedback on their proposal. Doing so will allow the trainee to practice clinical and ethical decision making and allow supervision to be more consultative and collaborative, rather than instructional. See the Appendix for a list of recommended activities trainees may consider on a weekly basis to prepare for supervision.

The trainee’s preparation for supervision meetings may vary as relevant topics arise in their clinical casework. The trainee should review relevant protocols at their site, ask other trainees about their experiences related to the topic, and review relevant research or other resources before bringing a recommendation to discuss in their supervision meeting. This is good practice for when they become a BCBA and need to conduct record reviews, seek consultation from other BCBAs, or identify research-based practices when facing a clinical problem. Although it is ideal to prepare in this way, the trainee may not always be able to prepare for the range of topics that will be discussed in a supervision meeting, particularly when a topic arises organically. In those instances, the trainee should ask any questions that they have, particularly when it is unclear how they should incorporate the topic into future clinical work. The trainee should not feel embarrassed to ask “obvious” questions or to ask their supervisor to return to a previous topic, to slow down, or to provide more specific instructions or examples. If the trainee feels uncomfortable asking questions, they should paraphrase or attempt to describe another example of the topic to receive additional feedback from their supervisor. Because every trainee enters a supervisory relationship with unique academic training and applied experiences, their supervisor may not always be aware of the topics with which the trainee is not yet confident. Although not knowing an answer can be aversive, the supervisor should not expect that the trainee knows everything. If that were the case, there would be no reason for supervision.

Although the trainee may use a number of strategies to monitor their development in the supervisory relationship, formal competency evaluations conducted by the supervisor are a critical element of this process. The timing of these evaluations should be outlined in the supervision contract. Competency evaluations may include items from the BCBA Task List (BACB, 2017) or other professional and interpersonal skills. In a recent survey of supervisors, over 60% reportedly included measurement of interpersonal, communication, and self-management skills (Sellers et al., 2019). Additionally, competency evaluations often include a combination of performance- and knowledge-based skills, which may be evaluated under a variety of contexts (Sellers et al., 2016c). The trainee should request a list of the competencies that will serve as the basis for their performance evaluations and periodically assess and set goals related to their performance on those items (Garza et al., 2018). As always, the trainee should ask questions that they may have about individual competencies, particularly if the skill is not operationally defined or it is unclear how they may demonstrate proficiency.

Relevant ethical codes for Guideline 2 are 5.03–5.05, 10.01, 10.05, and 10.06 (BACB, 2016), as well as 1.01, 1.02, 4.01, 4.06, and 4.09 (BACB, 2020b).

Recommended Practice Guideline 3: Provide Feedback and Evaluate the Effects of Supervision

The supervisor is required to evaluate the effects of their supervision (Bailey & Burch, 2016; BACB, 2016, 2019a, 2020b; Sellers et al., 2016a, b, c), but effective supervision also requires the trainee to continuously self-monitor their proficiency, progress, and responsiveness to feedback. Research has indicated that performance feedback is a critical component of training packages (Codding et al., 2005; LeBlanc et al., 2005; Page et al., 1982; Roscoe et al., 2006; Slowiak & Lakowske, 2017), although the way in which trainees receive and incorporate feedback into their practice may influence its effectiveness. When there are discrepancies between the trainee’s self-assessment and the feedback provided by the supervisor, the trainee should request an opportunity to demonstrate competence or ask for specific recommendations for improvement. For example, the trainee may ask “How can I show you that I can perform X?” or “Will there be an opportunity to demonstrate my competence in X?” rather than argue or debate the basis of the evaluation. At each evaluation, the trainee should consider the feedback provided by the supervisor and develop short- and long-term goals that may be met before the next evaluation. Additionally, the trainee should request feedback on at least one behavior that is relevant to their current clinical activities, the Task List (BACB, 2017), and prior feedback from their supervisor each week (see the Appendix).

Ideally, the trainee will receive frequent, explicit, and direct feedback from their supervisor about progress in a number of areas, including performance on professional development, interpersonal skills, clinical readiness, and conceptual knowledge. The trainee’s ability to accept this feedback is also critical and defined based on their immediate (e.g., listening to the feedback without protest, nodding, paraphrasing the relevant content) and future behavior (e.g., emitting new responses under similar situations). Actively listening and acknowledging the supervisor’s feedback, indicating appreciation for their guidance, asking follow-up questions, setting relevant behavior-change goals, and self-monitoring progress toward those goals are all ways that the trainee may show their supervisor that they are accepting of feedback (BACB, 2020e; Ehrlich et al., 2020). Sellers et al. (2016b) identified unwillingness or difficulty accepting and/or applying feedback as a common issue in the supervisory relationship. The trainee should discuss with their supervisor when and how feedback will be delivered, as well as appropriate (immediate) responses for accepting feedback.

The supervisor should provide structured feedback at set points during training, although more frequent feedback should also be provided during supervision of clinical or other day-to-day activities. Feedback may include a combination of supportive and corrective components (Slowiak & Lakowske, 2017; Turner et al., 2016). Although the trainee can always share their preference for different types of feedback, corrective feedback will likely be delivered at some point during their supervisory relationship. Receiving corrective feedback may sometimes be difficult and lead to the trainee feeling embarrassed or disappointed. When this is the case, the trainee may ask for clarification, accept the feedback and discuss it with the supervisor later, repeat the feedback to the supervisor, or request instructions for how to incorporate the feedback into other areas of their work.

In addition to receiving feedback, it is important for the trainee to periodically deliver feedback to their supervisor to ensure that their needs are being met. It is most appropriate for trainees to deliver feedback upon solicitation from their supervisor, but it may also be acceptable for trainees to initiate the feedback if problems arise in the supervisory relationship. Just like their supervisor, the trainee should be thoughtful in how this feedback is delivered to ensure that the supervisory relationship is not damaged. Turner et al. (2016) identified the reciprocal nature of feedback as a potential tool for monitoring the supervisor–trainee relationship, and although there may be disagreements in the content of the feedback, allowing opportunities for trainees to deliver feedback opens the dialogue for improving and/or maintaining a successful and positive supervisory relationship. Trainees may consider using the Supervision Monitoring and Evaluation Form developed by Turner et al. when delivering feedback to supervisors. Other formal evaluations may be required by the training site or the trainee’s academic program to evaluate the effects of supervision. There may also be options for the trainee to provide anonymous informal or formal feedback. However, trainees should be aware that anonymity may not always be possible and is likely dependent on their supervisor’s current supervisory volume. Nevertheless, providing feedback to a supervisor, colleague, supervisee, or caregiver is an important skill for the trainee to develop, and doing so effectively may improve their relationships and effectiveness as a behavior analyst. Much like their supervisor, the trainee’s feedback is most likely to be effective if they include reinforcement for the positive effects of supervision, as well as specific information about what has not been effective in the past. In doing so, the trainee should use a supportive tone, rather than being argumentative or accusatory. This skill will ultimately benefit the trainee when it is time to transition into the supervisor role as a practicing BCBA.

Relevant ethical codes for Guideline 3 are 1.01, 5.03, 5.06, and 5.07 (BACB, 2016), as well as 2.01 and 4.08–4.10 (BACB, 2020b).

Recommended Practice Guideline 4: Incorporate Ethics and Professional Development Into Supervision

Ethics

As the trainee begins to develop competence in their professional, interpersonal, and behavior-analytic skill sets, they should also pursue more advanced or nuanced topics in supervision meetings. Sellers et al. (2016c) suggested that it is important for supervisors to provide opportunities for the trainee to discuss ethical scenarios, the majority of which will come from personal accounts by their supervisor (Sellers et al., 2019). The trainee can also prepare their own ethical scenarios or incorporate scenarios provided in published resources (e.g., Bailey & Burch, 2016; Koocher & Keith-Spiegel, 2016; Sush & Najdowski, 2019). Bringing novel scenarios to supervision meetings will allow the supervisor to model their approach to ethical decision making. As endorsed previously, however, the trainee should always prepare for discussions during supervision meetings before they occur. For ethical scenarios, this should include reviewing the current version of the BACB ethics code (BACB 2020b; BACB, 2016) and following an ethical decision-making model (for examples, see Bailey & Burch, 2016, and Rosenberg & Schwartz, 2019). Additional resources are available to the trainee and may be incorporated into a discussion of ethical practice with their supervisor (e.g. BACB 2016, 2019b, 2020b, c; Brodhead & Higbee, 2012; Sellers et al., 2016a).

Although ethics may be an interesting topic for philosophical discussion, the application of ethical guidelines to clinical practice should also be a prominent feature of training. It is critical that the trainee develop a fundamental understanding of the ethical and professional expectations of the behavior-analytic practitioner. Indeed, ethical dilemmas may even arise in the supervisory relationship (BACB, 2016, Codes 1.06–1.07, 5.01–5.07, 7.01–7.02; BACB 2020b, Codes 1.11–1.14, 4.02–4.04, 4.06, 4.08–4.10). The trainee’s proficiency with the code and ethical decision-making models will help them identify instances in which ethical violations have occurred and how best to respond.

Professional Development

Among the greatest benefits of the supervisory relationship is learning how the supervisor maintains or expands their competence through various forms of professional development. Ideally, the trainee will have the opportunity to develop a number of prerequisite skills during their graduate training (e.g., finding relevant resources, critically evaluating experimental methods, noting limitations of findings), although maintaining those skills after leaving their graduate program requires distinct repertoires. The trainee might request specific resources their supervisor has found to be helpful in their professional practice. For example, the trainee might ask whether their supervisor attends conferences or professional meetings or whether they are members of special interest groups or other professional organizations. The trainee should consider and discuss how they will continue their professional development following their academic training, particularly when certain resources, such as journal subscriptions, are no longer freely available. The supervisor will be able to provide some insight into the activities that they have found to be helpful in their professional development, which can include numerous activities beyond those that are required to maintain their certification.

Relevant ethical codes for Guideline 4 are 1.01, 1.03, 6.01, and 6.02 (BACB, 2016), as well as 1.06, 2.01, and 4.07 (BACB, 2020b).

Recommended Practice Guideline 5: Continue the Professional Relationship Postcertification

Sellers et al. (2016c) described the termination of the supervisory relationship as an event worthy of celebration, reflection, and feedback. Although this should certainly be the case, the trainee might participate in supervised experiences with more than one supervisor or at multiple training sites. This will likely prove to be beneficial for their training, as they will receive more opportunities to contact a variety of supervision styles, perhaps occurring across unique training sites or clinical populations. Nonetheless, the trainee should still reflect on each experience and set goals based on their development therein. The trainee should consider developing experience goals for their future placements with their current supervisor, as the supervisor may recommend goals that the trainee had not considered. In their final supervision meeting, the trainee should reflect on their experience with the supervisor and provide feedback on their overall experience, as this will aid the supervisor in their professional development as well (see the Appendix).

The timing of supervised experiences will inherently affect the feedback that the trainee can provide to their supervisors. The most informative feedback the trainee may provide will likely occur after they have experienced multiple supervisory relationships. Notably, it may be difficult to compare and provide relative feedback across experiences as the opportunities, relevant Task List items, and clinical populations may qualitatively differ. The trainee should consider what aspects of each experience contributed to their professional development and provide this feedback to their supervisors. In order to provide this feedback to past supervisors, the trainee will need to maintain their professional relationship after the formal supervisory relationship has terminated.

Efforts to maintain the professional relationship will likely fall on the trainee. This may have little to do with their supervisor’s appraisal of their relationship. Instead, it is likely the case that the trainee will have only a handful of supervisors, whereas their supervisors may have had dozens (or even hundreds) of trainees. This does not absolve the supervisor from making an effort to continue their relationship with the trainee, but it will be helpful for the trainee to take a proactive approach to maintain their relationship postcertification. As the trainee’s fieldwork experience is nearing its end, they should have a formal discussion regarding ways in which they may continue their relationship, specifically noting how the supervisor may best support them in their professional career. The trainee might express their interest in continuing to meet with their supervisor or participating in other formal experiences (e.g., a peer-review group or journal club), request letters of recommendation, or ask for their supervisor to help them network with other behavior analysts (Sellers et al., 2016c). Perhaps the most effective way to maintain the relationship is to collaborate on research or other clinical activities. Doing so might lead to opportunities to collaborate or interact through task interdependence and shared reinforcement.

There may be instances in which a supervisor is unable to provide opportunities to collaborate, consult, or interact as frequently as the trainee had hoped. In these situations, the trainee should consider other ways to maintain their relationship. Sending their supervisor updates regarding new positions, exciting clinical outcomes, areas of research that interest them, or other life events will also help to maintain their professional relationship. The trainee might also find ways to acknowledge their supervisor for their contributions to their training or the field of behavior analysis. Many special interest groups through the Association for Behavior Analysis International have awards for clinical supervisors or mentors. Additionally, the supervisor’s company, university, and state or regional professional organizations may also have mechanisms for recognizing their contributions. Finally, at a bare minimum, attending state, regional, or international conferences might allow for at least annual interactions with previous supervisors.

Relevant ethical codes for Guideline 5 are 1.07, 8.02, and 9.04 (BACB, 2016), as well as 1.13, 1.14, 4.12, 5.05, and 6.05 (BACB, 2020b).

Conclusion

Supervision of behavior-analytic trainees has received growing attention, though the role of the trainee in this process is underemphasized. Although this is likely unintentional, the definitions and descriptions of supervision may often treat the trainee as a passive, rather than active, participant. Instead, each member of the supervisory relationship serves a critical, albeit distinct, role. This article was intended to provide guidance to the trainee in accordance with recommendations for the behavior-analytic supervisor as outlined by Sellers et al. (2016c). Additional resources provided by the BACB and the published work referenced in this article may help the trainee navigate their fieldwork experience and supervisory relationships. For example, Sellers et al. (2016c) provided a table of resources and activities related to each recommended guideline for supervisors. Similar resources and activities may also be appropriate for the trainee, and a review of the table may provide the trainee with a glimpse of some of the expectations of their supervisor. Finally, a sample checklist of recommended tasks for the trainee to complete at specific points in their supervisory relationship is also included in the Appendix. This resource should be adapted to best fit the trainee’s needs, ideally in concert with their supervisor. Overall, trainees should ensure that they are informed and prepared to take an active role in the supervisory relationship and fieldwork experience.

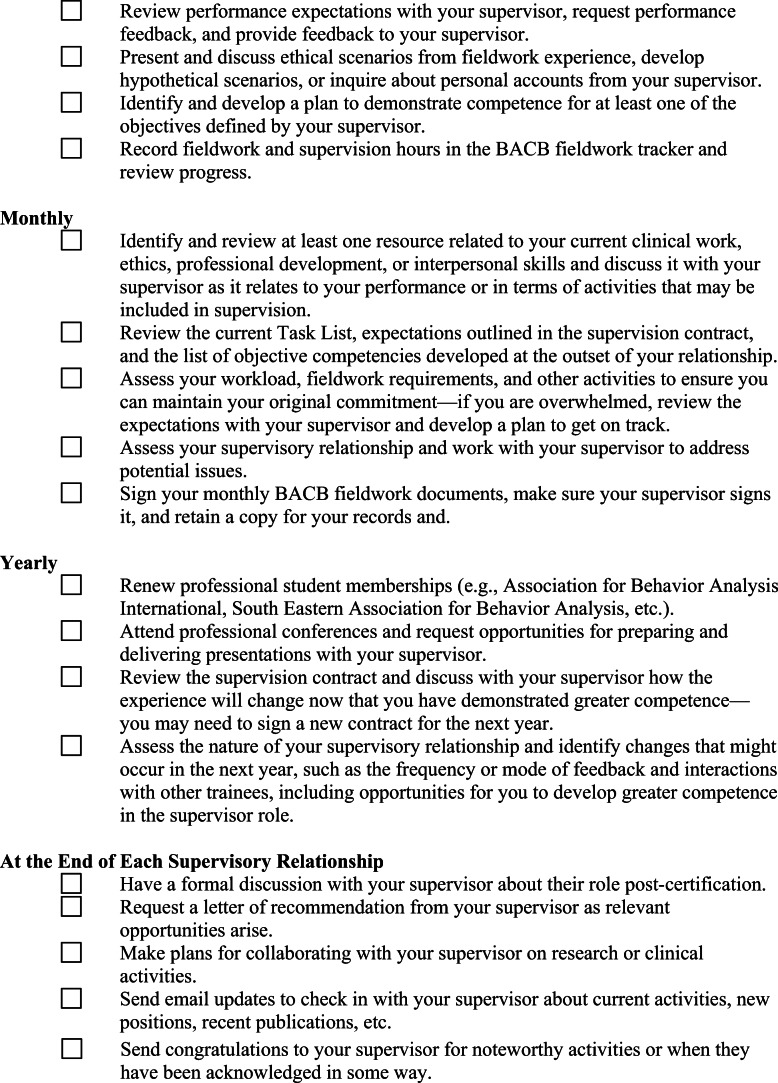

Appendix

Trainee “To-Do” Checklist

This checklist is recommended for use by behavior-analytic trainees to help guide practices in their supervisory relationship. Sellers et al. (2019) provided a similar checklist for supervisors. Recommendations are written in the second-person point of view to make it explicit that the actions listed in this resource are to be completed by the trainee.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Casey Irwin Helvey declares that she has no conflict of interest. Elizabeth Thuman declares that she has no conflict of interest. Tom Cariveau declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was sought because human participants were not used for research.

Informed consent

No informed consent was obtained because human participants were not used for research.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Guidelines for clinical supervision in health service psychology. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/guidelines-supervision.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Andzik, N. R., & Kranak, M. P. (2021). The softer side of supervision: Recommendations when teaching and evaluating behavior-analytic professionalism. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 21(1), 65–74. 10.1037/bar0000194

- Bailey, J., & Burch, M. (2016). Ethics for behavior analysts (3rd ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9781315669212

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). Contested experience/fieldwork form. https://www.bacb.com/contested-experience-fieldwork-form/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2016). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. http://www.bacb.com/Downloadfiles//BACB_Compliance_Code.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2017). BCBA/BCaBA task list (5th ed.). https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/170113-BCBA-BCaBA-task-list-5th-ed-.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019a, August). BACB newsletter. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BACB_August2019_Newsletter-.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019b). Ethics guidance. https://www.bacb.com/ethics/ethics-guidance/

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020a). Board Certified Behavior Analyst® handbook. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/BCBAHandbook_201119.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020b). Ethics code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ethics-Code-for-Behavior-Analysts-201228.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020c). Ethics-related journal and book resources. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Ethics-Related-Journal-and-Book-Resources_200603-1.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020d). Fieldwork standards. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-BCBA-Fieldwork-Standards_200501.pdf

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020e). Supervisor training curriculum outline (2.0). https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Supervision_Training_Curriculum_190813.pdf

- Bloom, L. J., & Bell, P. A. (1979). Making it in graduate school: Some reflections about the superstars. Teaching of Psychology, 6(4), 231–232. 10.1207/s15328023top0604_11.

- Brodhead MT, Higbee TS. Teaching and maintaining ethical behavior in a professional organization. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5(2):82–88. doi: 10.1007/BF03391827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cariveau T, La Cruz Montilla A, Ball S, Gonzalez E. A preliminary analysis of equivalence-based instruction to train instructors to implement discrete trial teaching. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2019;29:787–805. doi: 10.1007/s10864-019-09348-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codding RS, Feinberg AB, Dunn EK, Pace GM. Effects of immediate performance feedback on implementation of behavior support plans. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38(2):205–219. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.98-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, R. J., Nosik, M. R., Carr, J. E., & Wine, B. (2020). Teaching employees how to receive feedback: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(1-2), 19–29. 10.1080/01608061.2020.1746470.

- Garza, K. L., McGee, H. M., Schenk, Y. A., & Wiskirchen, R. R. (2018). Some tools for carrying out a proposed process for supervising experience hours for aspiring Board Certified Behavior Analysts®. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 11(1), 62–70. 10.1007/s40617-017-0186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Iwata BA, Wallace MD, Kahng SW, Lindberg JS, Roscoe EM, Conners J, Hanley GP, Thompson RH, Worsdell AS. Skill acquisition in the implementation of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33(2):181–194. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, E., Rice, B., & Adzhyan, P. (2019). Fieldwork and supervision for behavior analysts: A handbook. Springer Publishing Company.

- Koocher, G. P., & Keith-Spiegel, P. (2016). Ethics in psychology and the mental health professions (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- LeBlanc M, Ricciardi J, Luiselli J. Improving discrete trial instruction by paraprofessional staff through an abbreviated performance feedback intervention. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005;28(1):76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Page, T. J., Iwata, B. A., & Reid, D. H. (1982). Pyramidal training: A large‐scale application with institutional staff. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 15(3), 335–351. 10.1901/jaba.1982.15-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2015). Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(2), 2–11. 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Petscher EA, Bailey JS. Effects of training, prompting, and self-monitoring on staff behavior in a classroom for students with disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(2):215–226. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.02-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plavnick JB, Ferreri SJ, Maupin AN. The effects of self-monitoring on the procedural integrity of a behavioral intervention of young children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;43(2):315–320. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe EM, Fisher WW, Glover AC, Volkert VM. Evaluating the relative effects of feedback and contingent money for staff training of stimulus preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;37(535):538. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.7-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, N. E., & Schwartz, I. S. (2019). Guidance or compliance: What makes an ethical behavior analyst? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(2), 473–482. 10.1007/s40617-018-00287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sarokoff RA, Sturmey P. The effects of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37(4):535–538. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Alai-Rosales S, MacDonald RPF. Taking full responsibility: The ethics of supervision in behavior analytic practice. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):299–308. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers, T. P., LeBlanc, L. A., & Valentino, A. L. (2016b). Recommendations for detecting and addressing barriers to successful supervision. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 309–319. 10.1007/2Fs40617-016-0142-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, Landon TJ, Aiello S. Board Certified Behavior Analysts’ supervisory practices of trainees: Survey results and recommendations. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):536–546. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):274–286. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slowiak JM, Lakowske AM. The influence of feedback statement sequence and goals on task performance. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17(4):357–380. doi: 10.1037/bar0000084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sush, D., & Najdowski, A. C. (2019). A workbook of ethical case scenarios in applied behavior analysis. Academic Press.

- Turner, L. B. (2017). Behavior analytic supervision. In J. K. Luiselli (Ed.), Applied behavior analysis advanced guidebook: A manual for professional practice (pp. 3–20). Elsevier Academic Press. 10.1016/B978-0-12-811122-2.00001-2.

- Turner, L. B., Fischer, A. J., & Luiselli, J. K. (2016). Towards a competency-based, ethical, and socially valid approach to supervision of applied behavior analytic trainees. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(4), 287–298. 10.1007/s40617-016-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP. The benefits of group supervision and a recommended structure for implementation. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(4):320–328. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MJ. Comprehensive ABA programs: Integrating and evaluating the implementation of varied instructional approaches. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2005;6(4):249–256. doi: 10.1037/h0100077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]