Abstract

In his 2014 paper, Friman provided 15 recommendations for behavior analysts wishing to improve their public speaking skills and encouraged the field to view public speaking as a mechanism through which we can more broadly disseminate our science. Although some behavior-analytic research exists on the topic of public speaking, this body of literature is small, and many empirical questions remain. Little is known regarding which skills need to be targeted to improve public speaking and what successful public speakers in our field do to be effective and entertaining. In this study, we identified and interviewed the 10 most frequently invited public speakers at major behavior-analytic conferences. We then coded transcriptions of the interviews using qualitative analysis to generate a preparation checklist for presenters, a considerations list for behavior analysts training mentees on presentation skills, and a feedback form for those wishing to improve their public speaking skills.

Keywords: behavior analysis, dissemination, expert interviews, feedback, public speaking, recommendations

In recent years, the total number of certified behavior analysts has increased exponentially (Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], n.d.). Behavior analysis is becoming more recognized as a profession, and members of our field are more visible and sought out by employers (BACB, 2019). According to a recent employment demand report, annual demand for individuals holding Board Certified Behavior Analyst certification has increased by approximately 800% from 2010 to 2018, with increases seen in almost every state (BACB, 2019). As this growth occurs, it is important to examine professional repertoires or skills that will have a positive impact on the community and our profession. Several authors have identified some of these critical repertoires, including working effectively with individuals from diverse backgrounds (Beaulieu et al., 2018), arranging components of group supervision to maximize the experience (Valentino et al., 2016), accurately self-identifying one’s scope of competence (Brodhead et al., 2018), building therapeutic relationships (Taylor et al., 2019), and collaborating with professionals from other disciplines (Kelly & Tincani, 2013). Put another way, behavior analysts must target such areas for professional development that, if not developed appropriately, could have a negative impact on our relatively young field.

Effective public speaking is another critical professional repertoire for behavior analysts (Friman, 2014). Dissemination of scientific findings is necessary for the development of evidence-based practices, and expedited dissemination of collective findings is necessary to help narrow the research-to-practice gap (Kelly et al., 2019). No matter the discipline, oral presentations are an efficient means of disseminating information to large and varied audiences. Friman (2014) called this behavior “being in the front of the room” (p. 114) and defined it as any time a person has an audience—presenting at a conference or seminar, leading a meeting, or speaking with a group of peers. If not targeted, behavior analysts may make mistakes common to public speaking in general (e.g., high rates of speech disfluencies) that lead audiences to perceive them as less competent (Sereno & Hawkins, 1967). Behavior analysts might also make mistakes associated with our field—such as describing client outcomes via complex line graphs or using terminology that also has colloquial meaning (e.g., reinforcement, punishment, extinction) with unfamiliar audiences—that may result in a reputation that we do not “play nice in the sandbox” or that our treatments are inaccessible (Critchfield et al., 2017). Addressing such errors early in a behavior analyst’s training may increase the likelihood that important stakeholders (e.g., professionals from other disciplines, parents) select behavior-analytic intervention and adhere to our clinical recommendations. Investing in graduate students’ public speaking skills may also empower new generations of behavior analysts to effectively combat common misperceptions of our field while disseminating our science (Becirevic, 2014).

Unfortunately, many critical professional development skills are overlooked in behavior analysis graduate programs (e.g., Beaulieu et al., 2018; Kelly & Tincani, 2013; Taylor et al., 2019), including public speaking (Friman, 2014). Whereas the behavior-analytic literature on public speaking is small and mainly focused on reducing anxiety (Glassman et al., 2016; Laborda et al., 2016) and speech disfluencies (Mancuso & Miltenberger, 2016; Montes et al., 2019; Spieler & Miltenberger, 2017), other disciplines, such as communication sciences, counseling, and psychology, have included public speaking as a focus of study (e.g., Knight et al., 2016; Mladenka et al., 1998). There are also numerous mainstream resources available to help improve public speaking, such as websites with tips (e.g., North, 2019), books (e.g., O’Hair et al., 2015), courses (e.g., Effective Presentations Inc., 2019), and clubs (Toastmasters, 2019).

Although these resources are valuable and should not be ignored, students would need to invest time and money to identify and utilize materials most relevant to them. In addition, behavior analysis training programs are responsible for covering a growing list of concepts, applications, and professional skills. Faculty and supervisors likely distribute presentation opportunities throughout their programs (e.g., class assignments, conferences) and may not evaluate performance using a consistent feedback system. Therefore, behavior analysis students, faculty, and supervisors may benefit from simplified resources that can easily be incorporated into their existing curricula. As such, Friman (2014) used both mainstream resources and his personal experience to develop 15 behaviorally based recommendations for those wishing to improve their public speaking skills. In this study, we sought to expand Friman’s work by (a) identifying and interviewing the top 10 most frequently invited public speakers at major applied behavior analysis (ABA) conferences and (b) generating helpful tools (i.e., preparation checklist, comprehensive feedback form, list of considerations for mentors) from the recommendations provided.

Method

Participants

We identified 10 behavior analysts who were the most frequently invited speakers at ABA conferences or conventions. We included conferences or conventions that (a) had existed for at least 10 years and (b) had at least 500 attendees per year during those 10 years. The five events that fit these parameters included the (a) Association for Behavior Analysis International (ABAI) annual convention, (b) Texas Association for Behavior Analysis regional conference, (c) Berkshire Association for Behavior Analysis and Therapy annual conference, (d) Florida Association for Behavior Analysis annual conference, and (e) California Association for Behavior Analysis annual western regional conference.

We contacted the expert speakers ranked 1 through 10 via email and invited them to participate in an interview with an attached consent form. We did not receive a response from two of these individuals, and another indicated they could not participate due to other obligations. We then moved down the list of speakers and obtained consent from the individuals ranked 11–13 (i.e., until we had a total of 10 interviewees). When we identified ties for a particular rank, we broke the tie through random selection. Please see Table 1 for the final list of expert speakers who participated in the interview for this study, all of whom provided consent to be identified by name. The participants included one woman and nine men, all with doctoral degrees, who were either professors or in professional leadership positions within the field of ABA at the time of the study. The participants also reported presenting at conferences between 5 and 35 times per year.

Table 1.

List of Identified Expert Speakers

| Speaker | |

|---|---|

| James Carr | |

| Iser DeLeon | |

| Patrick Friman | |

| Timothy Hackenberg | |

| Gregory Hanley | |

| Linda LeBlanc | |

| Gregory Madden | |

| Matthew Normand | |

| David Palmer | |

| Tristram Smith |

Interviews

Each of the four experimenters conducted semistructured interviews with two to three participants using the same 15 questions (see Table 2). We sent the list of questions to the participants via email prior to the interview and scheduled interviews either in person at a location convenient to the participant and experimenter (e.g., ABAI convention) or electronically via videoconference (i.e., Zoom, Skype). All interviews were conducted within 1 month of speaker identification (i.e., May to June of 2018) and averaged approximately 30 min (range 17–47). We audio recorded all interviews and later transcribed them by reducing the playback speed of the recordings and typing out each response verbatim. In addition, we emailed participants approximately 1 month after their initial interview with one follow-up question (i.e., Item 16 in Table 2) and later analyzed their written responses.

Table 2.

List of Interview Questions for Expert Speakers

| Interview Questions | |

|---|---|

| 1. How frequently do you engage in public speaking? | |

| 2. Do you ever speak to non-behavior-analytic audiences? If so, how do you tailor your presentations for such audiences? | |

| 3. What is your philosophy on the use of visual aids? Or how do you feel about the use of visual aids? | |

| 4. Do you use visual aids? If so, how do you approach developing them, such as PowerPoint slides, for a public speaking event? If you do not use visual aids, why not? | |

| 5. Do you use speaker notes or scripts? If so, how do you use them? | |

| 6. How do you practice or prepare for a public speaking event? | |

| 7. Do you now, or have you ever, experienced nervousness, anxiety, or fear around public speaking? If so, what do you do to address this? | |

| 8. What do you consider to be the most important vocal verbal behaviors of an effective public speaker? | |

| 9. What do you consider to be the most important nonvocal verbal behaviors of an effective public speaker? | |

| 10. Do you believe that it is important for behavior analysts to be effective public speakers? Why or why not? | |

| 11. Do you ever train or mentor others around effective public speaking? If so, what strategies do you use to train effective public speaking repertoires? What strategies do you use to evaluate performance? | |

| 12. What are the most common public speaking errors or problems you see when observing others? | |

| 13. What do think are the most common controlling variables associated with those errors or problems? | |

| 14. If you were going to give one piece of advice to a novice public speaker, what would it be? | |

| 15. Is there anything else that you would like to share with us about your public speaking experiences? | |

| 16. Who are 3–5 behavior analysts you suggest others watch as a public speaking model and why? |

Note. Questions 1–15 were asked vocally during a semistructured interview with the expert speakers, and Question 16 was sent to the experts in a follow-up email.

Qualitative Coding and Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) of participant responses using a semantic approach (i.e., the explicit content of the responses directed our coding and theme development) using the following steps. First, we read all responses to a single question several times and highlighted possible recommendations from each participant. Second, we used the highlighted sections to pull direct quotes from each participant’s response (known as in vivo codes; Saldaña, 2009) and had a second experimenter repeat this process to avoid overlooking any potential recommendations. We then assigned short descriptive codes to each direct quote to categorize recommendations made by more than one participant and refined these codes after reviewing all initial descriptive codes. Third, we classified all refined descriptive codes under main themes and counted the number of participants who provided recommendations under each theme. Fourth, we reviewed each theme in relation to other themes for each question and renamed them (if necessary) to develop a summary of recommendations for each interview question (see Table 3 for an example of codes and themes for Item 3). Last, we reported our analysis using a narrative summary (with some additional tables and appendices when useful) for each interview question and embedded direct quotes as examples whenever possible. We did not link any recommendations to specific participants.

Table 3.

Examples of Codes and Themes for the Third Interview Question

| In vivo code | Descriptive code | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| “You should always have visual aids of some sort.” | Necessary | Value |

| “In a presentation, graphs are coming at the speaker’s pace, not the audience’s pace.” | Present digestible data | Style recommendations |

| “[The aid] should be . . . an opportunity for the audience to rest their eyes and look at something interesting while listening.” | Function as interesting stimulus to audience | Function |

Intercoder and Interobserver Agreement

Participant Identification

The second author served as the primary coder for identifying expert speakers to participate, and undergraduate research assistants enrolled at California State University, Sacramento, served as secondary coders. We coded conference programs of the five included conferences from 2008 to 2017 by tallying the number of events for which a speaker delivered an invited presentation, address, symposium, panel, paper, tutorial, keynote address, or B. F. Skinner lecture. We only counted an event (e.g., ABAI 2016) once per speaker, even if they were invited for multiple presentation types (e.g., both an invited address and an invited panel). We did not tally discussants, award presentations, presidential addresses, opening remarks, invited tributes, professional development series, or workshops because they did not include invited speakers (e.g., workshops submitted by the speakers themselves), or the speakers were likely selected using processes other than conventional conference committee consensus (e.g., presidential address). We identified 563 total speakers using these coding criteria. We calculated intercoder reliability for 30% of identified speakers using occurrence agreement in which each event recorded served as an occurrence. We scored an agreement if both the primary and secondary coders scored the occurrence of the same event. We divided the total number of agreements by the total number of occurrences and multiplied the result by 100. The average occurrence agreement was 99% (range 83%–100%).

Prior to finalizing the top 10 expert speakers, we reviewed any disagreements between the primary and secondary coders for the 25 most invited speakers to ensure the accurate number of public speaking events was assigned to each speaker. If there was a disagreement, the second author reviewed the conference programs to identify any errors. Following this review, we rank ordered the top 10 most invited speakers using the total frequency of presentations for each speaker across the five conferences.

Interview Transcriptions

A second experimenter independently transcribed a portion of each expert interview for interobserver agreement (IOA) purposes. The secondary transcriber used a random number generator to select approximately 30% of each interview to transcribe. For example, 30% of a 16 min 59 s interview is just over 5 min; therefore, the second experimenter randomly selected and transcribed a total of 6 min of that interview. The second experimenter compared her transcription word by word with the primary transcription, identified any word disagreements, and then divided the number of agreements by the total number of words and multiplied that value by 100. Our average IOA score across all interviews was 97% (range 94%–99%).

Results

Behavior Analysts as Public Speakers

All the participants agreed that it was important for behavior analysts to be effective public speakers for reasons that centered on the themes of public speaking as a general skill set, the power of dissemination and reach, and the history of behavior analysts as disseminators. Seven participants emphasized that they viewed public speaking as a skill set, and that anyone—behavior analyst or not—would benefit from learning how to speak effectively. For example, one participant mentioned, “I think just for being an effective grown up, it’s a nice skill to have,” and another stated, “Messages go nowhere without effective presentation skills.”

In addition, six participants emphasized the importance of using public speaking to disseminate our science both within and outside of the field (e.g., “We all know we need to disseminate more broadly . . . and public speaking is a very common way to do that”). Although most participants discussed using public speaking as an efficient platform to reach large numbers of people concurrently, one highlighted the importance of effectively conveying a message to even an individual listener:

You might be the only behavior analyst the person you are meeting is ever going to meet. . . . That means you are the entirety of our field to that person. . . . Be effective, be eloquent, and remember to convey the values that we have because you might be the only shot we have.

Finally, three of the participants related the importance of behavior analysts as effective speakers to our field’s history. Participants mentioned that “we [behavior analysts] haven’t done a great job of representing ourselves to the world” and that our common use of technical, discipline-specific terminology “turns a lot of people off. . . . It can be very off-putting and condescending to speak in jargon.”

Preparation

Nine of the 10 participants agreed that preparation was important for a public speaking event. In fact, prepare was the most commonly identified theme derived from all answers to this question. Only one participant noted that other than writing the content, they do no preparation until delivering the talk. Two participants discussed content fitting into the theme of efficiency of preparation. For example, one shared that they recycle content and visuals from previous talks, and another described that they create speaking points while preparing slides, rather than completing these tasks independently. The specific ideas about preparing mostly centered on creating an outline, writing the talk ahead of time, and practicing it out loud. A few creative suggestions were identified about preparation. One participant described that they practiced speeches while exercising to mimic the bodily sensations (e.g., heart racing, shortness of breath) that are likely present while delivering the speech. Two participants noted that they write out and memorize the first and last parts of their talk because those parts are likely to have the most impact on the audience. Finally, two participants described that they write out what they want to say in each block of the talk but practice it so much that they never actually use the text.

Visual Aids and Notes

We identified the themes of value, style, and function from the experts’ philosophies on using visual aids. Most experts (n = 7) viewed visual aids as important and, in some cases, necessary (e.g., “For a relatively lengthy talk, I need visual aids”). Half of the participants preferred simple visual aids, such as PowerPoint slides that included high-quality images with no distracting animations and slides with limited text and organization branding (e.g., logos, watermarks). One mentioned the importance of “building a PowerPoint”—that is, presenting one bullet at a time (rather than all text at once) and presenting data in digestible segments (e.g., “In a presentation, the graphs are coming at the speaker’s pace, not the audience’s pace”). Lastly, half of the participants stressed that visual aids should function as a stimulus to evoke the speaker’s verbal behavior, as well as an interesting visual stimulus for the listener. Four of those same participants also indicated that they avoided presenting identical information both vocally and as text on the slide. For example, one specified, “It’s almost impossible to do both [read the message and listen to the same message] well,” and another clarified that visual aids should “be something that is going to be engaging to the person who is looking . . . but not duplicative of what I say.”

When asked how they prepared visual aids, half of the participants explained their general process, whereas the others simply described their preference for simple visual aids (i.e., emphasizing images, decreasing text and distractors). Of those who explained their process, three described first talking through their topic either overtly or covertly, typically in a sequential manner, followed by either envisioning or searching for a visual that best evoked or represented their message. However, two participants described that they first determine learning objectives for their topic and then use a “backward design” to construct their talk. They described chunking the objectives and linking them to a common theme throughout the presentation with “planned redundancy” to aid in reiterating and transitioning between the learning objectives. One additional participant reported continuously refining their presentations and visual aids until giving the talk and clarified, “Talks are never done; they are just due.”

Although none of the participants reported using scripts while presenting, half stated that they used “Presenter view” in PowerPoint to access notes or prompts. However, these same participants also reported practicing until they no longer needed to use their notes, except for occasionally using notes for novel talks or to aid in transitions. In addition, we identified two main reasons why the experts avoided relying on scripts or notes. First, three participants viewed reading from a script as aversive for the listener. For example, one stated that using scripts “tends to lead to unnatural patterns of speaking,” and another stated that “reading a talk is extremely boring and ineffective.” Second, two participants mentioned that relying on notes limited the distance they can move away from their podium or computer, which can be problematic if they wish to move about the room or if the room is not situated in a manner where the speaker is in front of their computer.

Nonbehavioral Audiences

Six of the participants reported that they commonly spoke to nonbehavioral audiences, including medical and mental health professionals (e.g., pediatricians, psychiatrists), university or agency stakeholders, parents, and students. The remaining speakers reported that they either occasionally spoke to nonbehavioral audiences (n = 1) or rarely did so (n = 3). When they were asked how they tailor their presentations for more diverse audiences, we identified the themes of language, perspective taking, and difficulty from their responses. Most participants (n = 8) mentioned that they decreased their use of terminology, defined any necessary behavior-analytic jargon, and used as much everyday language as possible. Interestingly, none mentioned that they created different talks for different audiences—instead, most stressed the use of accessible visuals and language for any talk. For example, one participant stated, “Most audiences are mixed, and I want to reach everybody.” Another highlighted the history behind the importance of reaching their audience by saying, “So much has been made over the years about the technical speak of behavior analysis and how it really hurts us within the larger field of psychology.” One participant also mentioned that they “casualize it [terminology] even with the behavior-analytic audiences” to model how to speak with nonbehavioral audiences.

Regarding perspective taking, most participants (n = 6) indicated that they focused on being relatable to their audience either via relevant examples (e.g., “I try to anchor them [examples] within the context that the audience is likely to be familiar with”) or via their overall message (e.g., “I link what I have to say with the themes of their organization, meeting, or profession”). Finally, three participants mentioned tailoring the content difficulty of their presentation to their audience. For example, one clarified, “I try to tailor my talks explicitly to the baseline repertoire of the audience,” whereas another mentioned that they drew from their introductory undergraduate teaching experience (e.g., “I start at fairly low level and build up [the difficulty] over the course of the talk”).

Public Speaking Anxiety

All participants reported feeling anxiety or fear around public speaking at one point in their careers (e.g., “If I said no, you’d know I was lying”), and most (n = 8) indicated that they still experience nervousness. The two participants who no longer reported feeling anxious had a history as university professors and both conveyed that their teaching experience has likely functioned as exposure therapy for facing their fear. Not surprisingly, several participants (n = 4) indicated that they felt the most anxiety immediately prior to speaking or during the beginning of their presentation—one even referred to this time as “critical” and a “vulnerable spot.”

We identified the themes of preparedness and alternative behavior from the participants’ descriptions of how they address their public speaking anxiety. Seven participants emphasized the importance of preparation (e.g., “I think just getting practice and making sure I am reasonably prepared keeps it [the anxiety] manageable”), and two specifically reported that they practiced the first portion (e.g., first 5 min) of their talks to fluency. One participant expanded on this point and clarified that “people who are fearful should learn to perform while they’re afraid instead of trying not to be afraid.”

Most participants also mentioned that they strategically engaged in alternative responses immediately prior to or during the first few minutes of speaking (e.g., “I try to engage in some behavior that isn’t waiting without behaving”). These responses included overt behavior such as walking around the room and casually greeting audience members or engaging audience members in a challenge as soon as possible (e.g., “I try to find a central . . . way of engaging the audience right at the outset. Once I feel they are engaged . . . the anxiety dissipates”). Other participants explained that they engaged in a variety of covert behaviors such as “thinking about other things,” focusing their attention on “trying to find the anxiety within the body,” and reframing fear as excitement (e.g., “Be excited about what it is you have to say, and a lot of the [anxiety] problems go away”). Finally, one participant described that they consistently arrived early to their talk to relax, explaining,

The notion is your subjective experience of emotion is largely a function of you responding to your body. . . . It’s very important that before a presentation, you don’t do anything that produces physiological arousal. If you have to get from one conference hotel to another . . . your heartbeat will be elevated, and you will interpret that as you’re nervous. . . . I always leave a time cushion where I can relax, get there early, not necessarily to acclimate to the room, but to make sure that I am not doing things like helping someone move the podium back to the middle of the room.

Characteristics of an Effective Speaker

Nine of the 10 participants described important vocal verbal behaviors of effective public speakers, and we identified the three themes of voice quality (n = 6), delivery (n = 6), and responsiveness (n = 1) from their answers. Regarding voice quality, participants stated that effective public speakers vary their prosody or paralinguistic behavior while presenting—that is, their “intonation,” “volume,” “tone,” “pitch,” “pacing,” and “enunciation.” They also commented that effective speakers “work toward unscripted presentations” and “learn how to use the full range of their voice.” As to delivery, the participants emphasized that effective speakers use a conversational, relaxed, and authentic tone and commented that such speakers tend to have a “very structured talk, but one that feels like a conversation.” One commented, “I think you have to smile with your voice,” whereas another stated, “The most important thing for a presenter is to come across as authentic.” Finally, one participant’s comments fell under the responsiveness theme; they described that effective speakers “react to the audience as a listener” and in turn “improvise and tailor on the fly to make it [the presentation] better.”

We identified the three themes of movement (n = 9), nonlinguistic behavior (n = 9), and audience interaction (n = 4) from the participants’ comments regarding important nonvocal verbal behavior of effective public speakers. With reference to movement, one stated, “You can be an effective ‘podium speaker’ or an effective ‘walking-around speaker.’” Other participants echoed this statement. That is, some preferred walking around while speaking (e.g., “I hate being restricted by the podium. . . . I move around the room and sometimes down the aisles”), whereas others preferred standing at the podium (e.g., “Way back when, I used to walk around a lot, but . . . the more I see people do it, the less effective I think it is. I just stand at the podium”). A few participants also mentioned that too much movement or poor control of movement could be distracting (e.g., “Nothing is worse than seeing a poor walker. . . . It is awkward”), whereas others highlighted the importance of timing one’s movements. For example, one participant explained,

The body is part of the message, and so you should make sure that what it is doing does not distract from what is being said. . . . All the body movements should be executed in a way that amplifies what you are trying to say and is done for a particular reason. I’m walking back and forth because I am connecting with people on both sides of the room. So, . . . do your movements on purpose.

Regarding nonlinguistic behavior, the participants noted the importance of hand gestures, facial expression, eye contact, and posture while delivering a message. Like larger movements such as walking, they described that hand gestures were important, but too many gestures could be distracting (e.g., “I come from a culture that is very expressive; everyone talks with their hands. I don’t know that that’s necessarily a great public speaking behavior. It can be distracting”). Some recommended that speakers should “talk to everyone, make reasonable eye contact, and keep your face to the audience,” as well as “stand up straight” and “be aware of your facial affect.” Finally, several participants noted the importance of smiling—for example, one stated, “Smile as often as you can as long as it’s not some kind of hideous leer. But put a smile on your face! It does something for the audience; it also does something for the speaker.” Last, regarding audience interaction, participants described the importance of orienting toward the audience (e.g., “You need to be looking back at them [the audience], and in doing so, you create this consistent engagement with them”) and scanning the audience (e.g., “scanning your head back and forth so that the entire audience sees your face”).

Public Speaking Mistakes

When the participants were asked to describe common public speaking errors, we identified the main themes of preparation (n = 10) and presentation style (n = 8) from the experts’ responses. Under the preparation theme, nine participants mentioned a lack of practice and an overreliance on scripts, and two of these participants noted that some senior-level behavior analysts are still guilty of these errors (e.g., “They mistake . . . seniority level for public speaking expertise”). Six participants also described poorly constructed or complicated graphs as errors. For example, one stated that presenters “should give the audience time to read them [graphs] . . . and make sure that it is going to be legible.” A few participants commented on the amount of time taken on complicated graphs, and one suggested that presenters “not use real graphs at all but . . . make new simplified graphs . . . with regression lines rather than raw data…so that the audience members are not bewildered by this profusion of data points.” Five participants also reported the use of overly detailed visual aids and content (e.g., “having too much material or too many slides”). One clarified, “The presentation should be simplified. . . . speakers should cut down on the detail. . . . The speaker should not confuse the requirements of a published paper with the requirements of a research presentation.” Four conveyed a lack of perspective taking as an error (e.g., “I don’t think that the speakers generally take their audience into account . . . they use too much technical language”).

Regarding presentation style errors, four participants commented on the likeability of presenters and the use of jokes. For example, they mentioned disliking conceited (e.g., “being arrogant about your brand of behavior analysis”) or distant (e.g., “speaking to audiences rather than talking with them”) presentation styles. One participant shared that they disliked when presenters lack an individual style (e.g., “complete flatness because they are a scientist”) or use a similar format to most other presenters from their research group, calling this style “formulaic.” The same participant also mentioned “off-colored, forced jokes” as a common error, and another suggested letting jokes speak for themselves (e.g., “If you put a cartoon or a joke slide up, don’t read it to your audience and explain it”). In addition, four participants described distracting behavior (e.g., speech disfluencies or filler words, forced style) as common errors, whereas four other participants noted an absence of storytelling (e.g., “Just tell me a story and tell me one that your mother would understand”) as common errors.

When we asked the participants to comment on the controlling variables behind common public speaking errors, we identified the themes of practice, mentorship, fear, and audience control from their responses. Regarding lack of practice (n = 6), one participant stated,

It goes back to people not taking the presentation itself as seriously as the work that they do and not looking at the presentation as a skill in and of itself. It is not a summary of a paper you wrote.

Half of the participants also mentioned insufficient or poor mentorship as a potential controlling variable. For example, one explained that “faculty press students to give technical presentations,” and another stated, “There isn’t a lot of training in public speaking” and that even mentors “may have some trouble organizing a professional presentation.” Regarding fear, half of the experts mentioned public speaking anxiety as a factor, and one participant explained that novice speakers often have a “fear of being less than perfect.” Last, two participants discussed a lack of audience control as a controlling variable behind public speaking errors. One exclaimed, “Publication standards are the villain to some extent. . . . It is not important for the audience to know all of the details. . . . Speakers expect audiences to be as critical as a reviewer of a publication,” and another mentioned that public speaking errors may be “rule-governed instead of contingency governed. . . . Speakers are not being shaped by and not attending to the audience.”

Expert Advice

Most participants (n = 7) advised novice speakers to consider the audience and have a message (e.g., “It is most important to figure out what the reinforcers are for the audience. . . . See if the audience is getting those reinforcers. Why are they there?”). Likewise, they stated, “Have a message and make sure you are clear on what that message is,” and, “Only accept speaking opportunities when you have something to say.” Most (n = 6) also recommended that novice speakers should consider public speaking as a skill set. One participant stated, “We all make tradeoffs in terms of the amount of response effort we are willing to put into something based on its value to us. . . . Treat it [public speaking] seriously and practice.” Finally, two participants advised that speakers should be authentic in their style, and one clarified by stating, “Make it [public speaking] enjoyable for yourself. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Coming off as natural is a lot more important than coming across as flawless.”

Training Effective Speakers

All but one participant reported that they have trained or mentored others around effective public speaking in some form or another (e.g., “I’ve never developed a program for effective speaking, but I’m often training them [students]”). Each of the participants who answered that question positively also described that they used components of behavioral skills training (BST; i.e., instructions, modeling, rehearsal, and feedback), and one even stated, “I use a training approach. I don’t think about it as shaping . . . more of an extended BST model.” Not surprisingly, we identified the four components of BST as themes from the experts’ transcripts.

Interestingly, only one participant described the instructions component of BST, and this participant instructed their mentees to “outline . . . figure out who your audience is . . . and prepare the visuals” before presenting to an audience. Four of the nine participants described the modeling component, of which three mentioned that they provided the model themselves, whereas one pointed out other models as “good speakers to go listen to and pay attention to” at conferences. All discussed how they implemented the rehearsal and feedback components of BST. They described that they offered multiple practice opportunities in front of different audiences. One participant specified that they structured initial rehearsal opportunities in a less stress-provoking environment with a familiar audience (e.g., “There are no outsiders, because I want them [the mentees] to be very comfortable”) and indicated that rehearsal opportunities should be filled with “dedicated practice” and that mentees should “always present with a mission.”

None of the participants described a systematic feedback method and, instead, reported a variety of subjective evaluations (e.g., “I don’t really have a rubric or formal training process”). Three reported that they listened to practice presentations in their entirety before presenting feedback (to avoid disrupting the speaker) and that all audience members were involved in providing feedback. One also designated a notetaker to transcribe feedback so the speaker could reference all comments and suggestions when subsequently revising their talk, whereas another noted the importance of video feedback for the speaker (i.e., “Video yourself and watch it immediately. . . . Identify what are the three things that you think are most important to work on from that”). Finally, four participants stressed the importance of descriptive praise while providing feedback. For example, one mentioned that they try to “build a culture of positive feedback” without using a “praise sandwich” to provide corrective feedback. This same participant also noted that they intentionally avoided corrective feedback after authentic (e.g., conference) presentations, explaining,

I try to show my appreciation that someone put their behavior out there, because it is hard to do. . . . So, I just want to make sure they feel rewarded for doing so. . . . So, no negative feedback after an authentic [public speaking engagement].

Suggested Models of Effective Speakers in the Field

Without knowing whom the other experts were, nine participants identified 22 individuals they suggest other behavior analysts watch as public speaking models, and six of these models overlapped with our participant pool. We identified the themes of presentation organization or style, speaking style, engaging, and articulate from their responses. The individuals included in each of these categories are listed in Table 4. For example, under presentation organization or style, one participant wrote that Derek Reed is the “master of the PowerPoint/visuals,” and another that Janet Twyman “has a high level of mastery of the technical dimensions of graphics and PowerPoint.” For presenters with exemplary speaking style, one participant noted that Gregory Hanley is “a polished, yet very natural presenter,” and another that Leonard Green is “energetic and varies his pace.” For engaging presenters, one participant noted that Patrick Friman “crafts presentation into story,” and another that Matthew Normand “spins a great story” and “makes the esoteric interesting.” Finally, for articulate public speaking models, one participant wrote that Gregory Madden is “adept at getting complex material across to audiences that range widely in background,” and another that Peter Killeen has the “ability to take complex material and make it accessible.”

Table 4.

Public Speaking Models and Themes Identified by Expert Speakers

| Speaker | Themes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation style | Speaking style | Engaging | Articulate | |

| Jon Borrero | X | X | ||

| Jim Carr | X | |||

| Michael Dougher | X | X | ||

| Francesca degli Espinosa | X | X | ||

| Patrick Friman | X | X | X | |

| Leonard Green | X | X | X | |

| Gregory Hanley | X | X | X | |

| Steve Hayes | X | X | ||

| Brian Iwata | X | X | ||

| Peter Killeen | X | X | ||

| Gregory Madden | X | X | ||

| Alan Neuringer | X | |||

| Matthew Normand | X | X | ||

| David Palmer | X | X | ||

| Cathleen Piazza | X | X | ||

| Carol Pilgrim | X | |||

| Thom Ratkos | X | X | ||

| Derek Reed | X | X | X | |

| Mark Sundberg | X | X | X | |

| Jonathan Tarbox | X | X | ||

| Bridget Taylor | X | X | ||

| Janet Twyman | X | X | X | X |

Additional Points

Seven of the 10 participants provided extra advice that they thought would be helpful to readers when asked if they had any additional thoughts, and we identified varied themes given the broadness of this question: professionalism, preparation, confidence, growth, humility, service to the field, and enjoyment. There were some unique recommendations in this section worthy of specifically mentioning. For example, one participant highlighted the importance of always asking for an artist’s permission to use images in a talk rather than freely taking them from the internet (e.g., to avoid infringing on copyrights, potential litigation). Four participants discussed public speaking anxiety and shared that an individual can overcome anxiety and give a successful talk, that it is very normal to experience anxiety even after many years of public speaking, and that anxiety should be viewed as something that can assist someone in delivering a high-quality talk. Finally, several participants described that they still feel honored when they are asked to give a talk and that they see these opportunities to speak as ways to serve the field and grow as a professional.

Discussion

The aim of our discussion is to condense the suggestions described previously into practical tools, highlight the need for equitable representation of women and other minorities in the “front of the room,” and encourage future research. We reviewed all themes from our analysis and noted three main intersecting ideas. First, speakers ought to consider their audience when preparing and respond to their audience via their vocal (e.g., using everyday language) and nonvocal verbal behavior, especially when speaking to a group of varied listeners. The finding that behavior-analytic terms are regarded as more unpleasant than terms used to describe general science and clinical work further supports this idea (Critchfield et al., 2017). Second, speakers need to treat public speaking as a skill set rather than an innate trait; meaning, it is vital to prepare and rehearse to decrease public speaking anxiety and increase overall quality and effectiveness. Finally, speakers should remember the importance of dissemination—ABA is a field that is often misunderstood by other professions and society (Morris, 1985). Public speaking is an efficient mechanism to circulate accurate information; however, behavior analysts in the “front of the room” need to effectively convey their message to truly do a service to our field.

We identified our participants similar to Keeley et al. (2016), who identified excellent teachers via national teaching award archives, but there are some limitations of our methods worth mentioning. First and foremost, the most frequently invited presenters might not necessarily be the most proficient speakers in our field. However, when asked to identify public speaking models, our participants (who were unaware of all other participants’ identities) named 6 of the 10 speakers identified via our methods. Second, we only included the last 10 years of five ABA conferences in our evaluation. It is possible that some speakers turn down invitations to these conferences because they instead choose to present at conferences outside of ABA, such as behavior analysts with expertise outside of developmental disabilities (e.g., fitness, organizational behavior management, neurorehabilitation). On the other hand, it is also possible that speakers ask to be invited, conference committee members invite their colleagues, and so on.

We would also like to note that our methods did not aid in identifying a diverse or representative sample of speakers—our “top 10” list only included one woman, and only 23% of the model speakers named by our participants are women. Fortunately, our profession is beginning to recognize and discuss issues surrounding equity (Fong et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019), including a special series on women in The Behavior Analyst (Nosik & Grow, 2015) and a special issue on diversity and inclusion in Behavior Analysis in Practice (Zarcone et al., 2019). It seems that this discussion is producing some promising outcomes. For example, Nosik et al. (2019) found that approximately 27% of invited speakers at ABAI conventions from 2014 to 2016 were women, which is an increase from previous years (e.g., 15% in 1991; Myers, 1993). However, to the authors’ knowledge, representation of speakers (as well as editorial board members, faculty, etc.) has not been analyzed by other critical demographic variables, such as race or ethnicity. Therefore, there is much work to be done to ensure that women and minorities have equitable opportunities at the “front of the room.” Li et al. (2019) recommended that those “employed in behavior analysis training programs . . . act quickly and forcefully to eliminate practices that are discriminatory” to help close the gender pay gap in academia (p. 745). We echo this recommendation and call for all conference committee members to speak up regarding discriminatory practices when selecting speakers. In addition, conference attendees should have the opportunity to provide feedback to conference committees on the representativeness of speakers.

As mentioned previously, behavior-analytic research on public speaking is scarce. We focused on traditional “front of the room” presentations in our study. However, dissemination is beginning to transition from infrequent conferences to more expedited “Web 1.0 and 2.0” technologies (Bernhardt et al., 2011)—including podcasts, webinars, YouTube videos, social media posts, and so on—which seem to be quite popular for younger generations of behavior analysts. It is still critical to be an effective speaker when disseminating our science via other modalities. It might prove interesting to analyze which skills identified in this study overlap and do not overlap with the skills necessary to be an effective podcast presenter, and so forth.

In addition, we noted that only two speakers described using learning objectives when preparing their talks even though the BACB “strongly encourages” their inclusion in any approved continuing education event (BACB, 2020). Similarly, whereas almost all our interviewees discussed their involvement in mentoring others’ public speaking skills, none of them reported using a systematic program for doing so. This second finding seems akin to our profession’s approach to clinical supervision—that is, the literature on taking a structured approach to supervision has only recently emerged (e.g., Sellers et al., 2016; Valentino et al., 2016). Although behavior analysts training others to be effective speakers (similar to our interviewees) are likely using some components of BST and encouraging their mentees to use learning objectives when preparing their talks, additional tools—such as a preparation checklist, a detailed feedback form, and a list of considerations for mentors on how to “pull back the curtain” and model public speaking skills intentionally—may prove useful. We developed such tools (see Appendices A–C) using the results of this study, as well as our approaches as doctoral-level faculty and clinical supervisors. We caution readers that we have not empirically validated these tools; therefore, we encourage researchers to evaluate them. For example, researchers have evaluated the Teacher Behavior Checklist (i.e., a checklist developed to train future faculty at Auburn University) and found it had excellent psychometric properties and could effectively differentiate between good and bad teachers (Buskist et al., 2002; Keeley et al., 2010; Keeley et al., 2006).

Finally, our interviewees stressed the importance of style to convey a message, and we noted both overlapping and idiosyncratic behaviors when they described their own styles. For example, many emphasized eye contact and audience interaction; however, some mentioned they preferred to walk around the stage and use humor, whereas others preferred storytelling while at the podium. This finding suggests that those wishing to improve their public speaking skills should watch a variety of high-quality models to develop a style that is both individualized and entertaining. Our goal for this study was to expand on Friman’s (2014) recommendations paper, as well as the small number of behavior-analytic studies on public speaking, by summarizing information from many excellent models in our field to provide some practical tools for behavior analysts interesting in improving their public speaking skills. It is our hope that faculty and supervisors in behavior analysis training programs incorporate and empirically evaluate these tools in their existing curricula to help shape this critical repertoire for future behavior analysts.

Author Note

We honor the late Dr. Tristram Smith, whose interview was conducted shortly before his untimely passing. We also thank the research assistants who served as data coders: Shelby Bryeans, Alex Guendulain, Chelsea Helm, Savauna Lacey, and Christina Warner. The content of this article does not reflect an official position of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board.

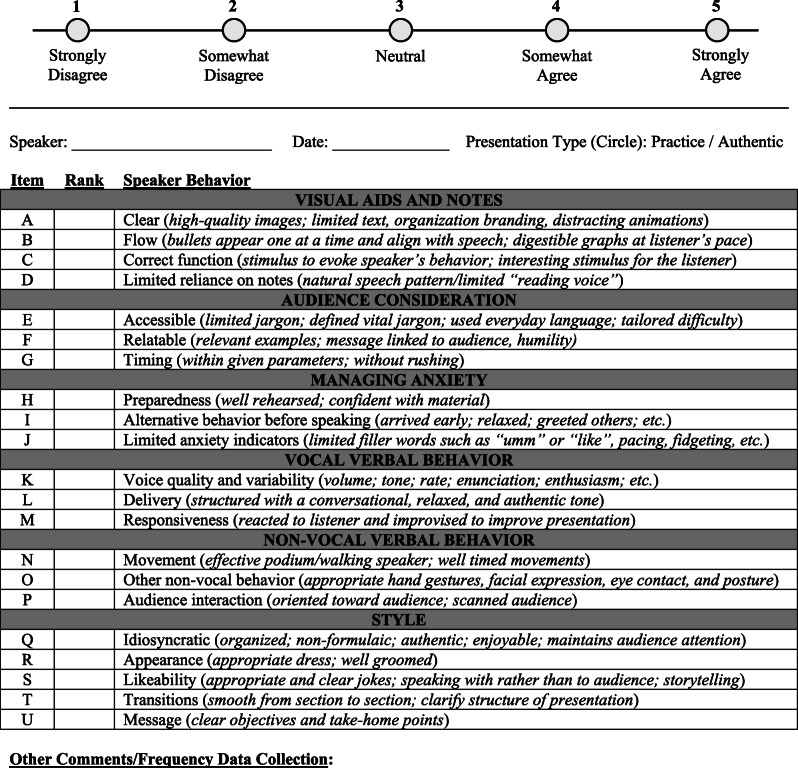

Appendix A: Public Speaking Feedback Form

For each speaker behavior that follows, please rank the presentation using the following 5-point Likert scale and record comments regarding positive and negative aspects of the presentation in the space provided. Please read all items carefully before rating.

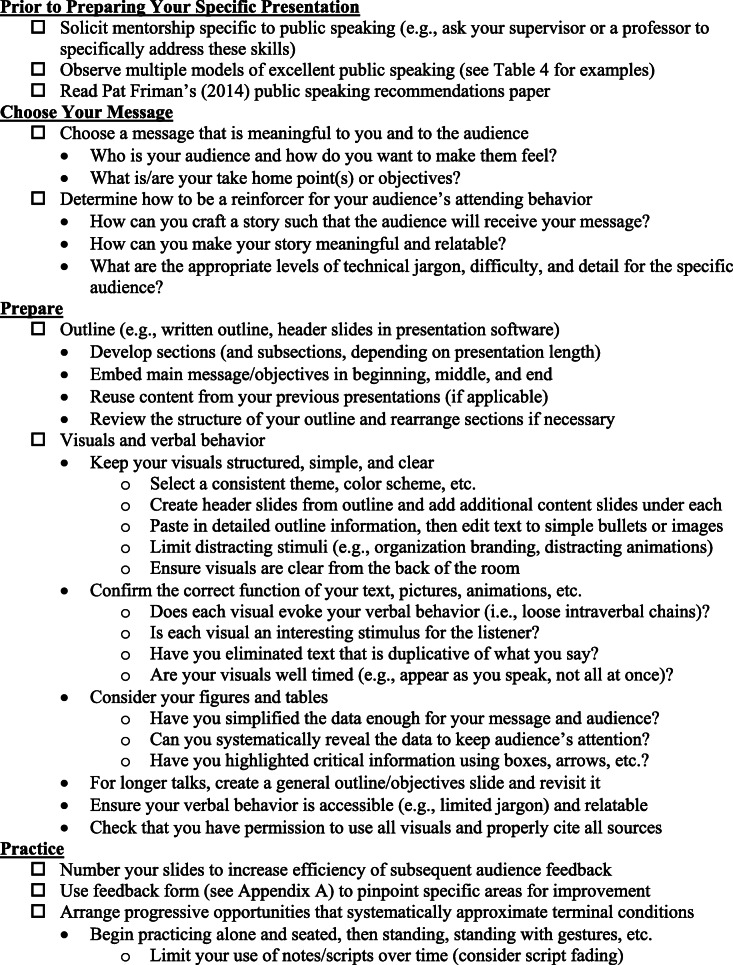

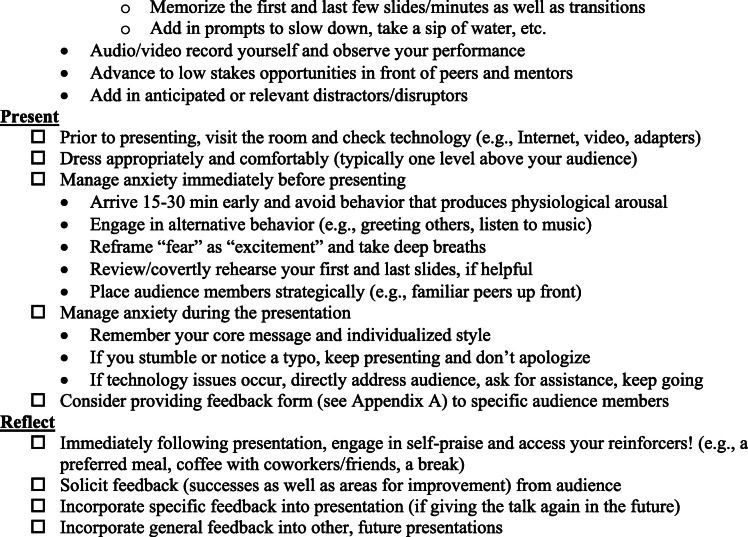

Appendix B: Public Speaking Preparation Checklist

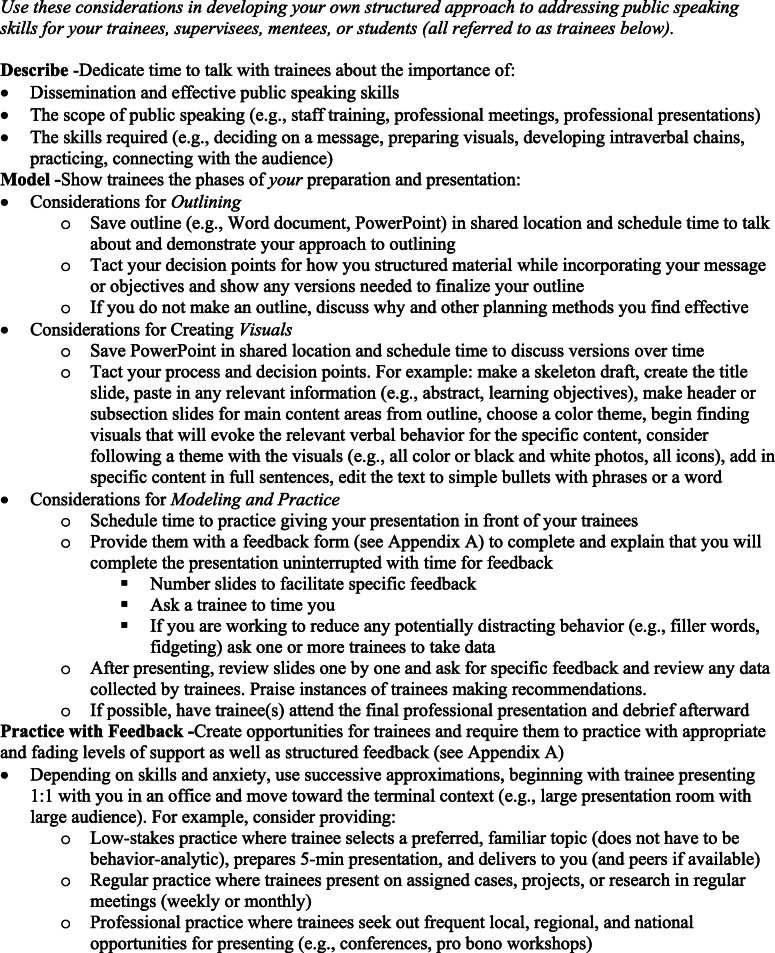

Appendix C: Considerations for Supervisors/Mentors

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Implications for Practice

This paper

• helps behavior analysts learn strategies to improve their public speaking skills,

• offers guidance to those teaching behavior analysts on how to effectively shape public speaking skills,

• provides specific behaviors that behavior analysts can engage in to deliver high-quality public speaking events (via an easy-to-use checklist), and

• provides researchers with several ideas for future studies to encourage continued research on this underinvestigated topic.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Beaulieu L, Addington J, Almeida D. Behavior analysts’ training and practices regarding cultural diversity: The case for culturally competent care. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;12:557–575. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becirevic A. Ask the experts: How can new students defend behavior analysis from misunderstandings? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2014;7:138–140. doi: 10.1007/s40617-014-0019-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (n.d.). BACB certificant data. https://www.bacb.com/BACB-certificant-data

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019). US employment demand for behavior analysts: 2010–2018.

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). ACE provider handbook. https://www.bacb.com/authorized-continuing-education-providers/

- Bernhardt JM, Mays D, Kreuter MW. Dissemination 20: Closing the gap between knowledge and practice with new media and marketing. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16:32–44. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.593608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Wilczynski SM. A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11:424–435. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskist W, Sikorski J, Buckley T, Saville BK. Elements of master teaching. In: Davis SF, Buskist W, editors. The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie and Charles L. Brewer. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield TS, Doepke KJ, Epting LK, Becirevic A, Reed DD, Fienup DM, Kremsreiter JL, Ecott CL. Normative emotional responses to behavior analysis jargon or how not to use words to win friends and influence people. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2017;10:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0161-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effective Presentations Inc. (2019). Public speaking training workshops, classes and coaching. https://www.effectivepresentations.com/public/public-speaking-training/

- Fong EH, Ficklin S, Lee HY. Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17:103–113. doi: 10.1037/bar0000076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friman PC. Behavior analysts to the front! A 15-step tutorial on public speaking. The Behavior Analyst. 2014;37:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s40614-014-0009-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman LH, Forman EM, Herbert JD, Bradley LE, Foster EE, Izzetoglu M, Rocco AC. The effects of a brief acceptance-based behavioral treatment versus traditional cognitive-behavioral treatment for public speaking anxiety: An exploratory trial examining differential effects on performance and neurophysiology. Behavior Modification. 2016;40:748–776. doi: 10.1177/0145445516629939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley J, Furr RM, Buskist W. Differentiating psychology students’ perceptions of teachers using the Teacher Behavior Checklist. Teaching of Psychology. 2010;37:16–20. doi: 10.1080/00986280903426282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley JW, Ismail E, Buskist W. Excellent teachers’ perspectives on excellent teaching. Teaching of Psychology. 2016;43:175–179. doi: 10.1177/0098628316649307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keeley J, Smith D, Buskist W. The Teacher Behaviors Checklist: Factor analysis of its utility for evaluating teaching. Teaching of Psychology. 2006;33:84–91. doi: 10.1207/s15328023top3302_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Tincani M. Collaborative training and practice among applied behavior analysts who support individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. 2013;48:120–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MP, Martin N, Dillenburger K, Kelly AN, Miller MM. Spreading the news: History, successes, challenges, and the ethics of effective dissemination. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:440–451. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-0238-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight ML, Johnson KG, Stewart F. Reducing student apprehension of public speaking: Evaluating effectiveness of group tutoring practices. Learning Assistance Review. 2016;21:21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Laborda MA, Schofield CA, Johnson EM, Schubert JR, George-Denn D, Coles ME, Miller RR. The extinction and return of fear of public speaking. Behavior Modification. 2016;40:901–921. doi: 10.1177/0145445516645766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Gravina N, Pritchard JK, Poling A. The gender pay gap for behavior analysis faculty. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:743–746. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00347-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso C, Miltenberger RG. Using habit reversal to decrease filled pauses in public speaking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:1–5. doi: 10.1002/jaba.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mladenka JD, Sawyer CR, Behnke RR. Anxiety sensitivity and speech trait anxiety as predictors of state anxiety during public speaking. Communication Quarterly. 1998;46:417–429. doi: 10.1080/01463379809370112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montes CC, Heinicke MR, Geierman DM. Awareness training reduces college students’ speech disfluencies in public speaking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2019;52:746–755. doi: 10.1002/jaba.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris EK. Public information, dissemination, and behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst. 1985;8:95–110. doi: 10.1007/BF03391916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers DL. Participation by women in behavior analysis: II. 1992. The Behavior Analyst. 1993;16:75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF03392613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North, M. (2019). 10 tips for improving your public speaking skills. Harvard Extension School Professional Development Blog. https://www.extension.harvard.edu/professional-development/blog/10-tips-improving-your-public-speaking-skills

- Nosik MR, Grow LL. Prominent women in behavior analysis: An introduction. The Behavior Analyst. 2015;38:225–227. doi: 10.1007/s40614-015-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosik MR, Luke MM, Carr JE. Representation of women in behavior analysis: An empirical analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2019;19:213–221. doi: 10.1037/bar0000118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hair, D., Rubenstein, H., & Stewart, R. (2015). A pocket guide to public speaking. Bedford/St. Martin’s

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers TP, Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA. Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:274–286. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0110-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereno KK, Hawkins GJ. Effects of variations in speakers’ nonfluency upon audience ratings of attitude toward the speech topic and speakers’ credibility. Speech Monographs. 1967;34:58–64. doi: 10.1080/03637756709375520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spieler C, Miltenberger R. Using awareness training to decrease nervous habits during public speaking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50:38–47. doi: 10.1002/jaba.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BA, LeBlanc LA, Nosik MR. Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:654–666. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toastmasters. (2019). All about Toastmasters. https://www.toastmasters.org/about/all-about-toastmasters/

- Valentino AL, LeBlanc LA, Sellers TP. The benefits of group supervision and a recommended structure for implementation. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:320–328. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarcone J, Brodhead M, Tarbox J. Beyond a call to action: An introduction to the special issue on diversity and equity in the practice of behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12:741–742. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]