Abstract

Clinical symptoms of impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome may not only be expressed as the splitting of cell layers within the epidermis but are often accompanied by some localized inflammation. Toxin patterns of Staphylococcus aureus isolates originating from patients with impetigo and also from those with other primary and secondary skin infections in a retrospective isolate collection in France and a prospective isolate collection in French Guiana revealed a significant association (75% of the cases studied) of impetigo with production of at least one of the epidermolysins A and B and the bicomponent leucotoxin LukE-LukD (P < 0.001). However, most of the isolates were able to produce one of the nonubiquitous enterotoxins. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of genomic DNA hydrolyzed with SmaI showed a polymorphism of the two groups of isolates despite the fact that endemic clones were suspected in French Guiana and France. The combination of toxin patterns with PFGE fingerprinting may provide further discrimination among isolates defined in a given cluster or a given pulsotype and account for a specific virulence. The new association of toxins with a clinical syndrome may reveal principles of the pathological process.

Among the variety of human infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, skin infections in which the bacteria are isolated are very important in ambulatory and hospital routines. Skin infections caused by S. aureus can be primary, like staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS), furuncles, folliculitis, carbuncles, abscesses, whitlows, perleche, onyxis, and sycosis. The discovery of staphylococcal toxins provided evidence of association for some of them, such as toxic shock syndrome toxin (TSST-1) with the staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome (47), epidermolysins A and/or B (or exfoliative toxins) with SSSS (22, 32), and Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL) with furuncles (9, 34). Recently, S. aureus strains producing enterotoxin A together with the bicomponent leucotoxin LukE-LukD (18) were associated with staphylococcal postantibiotic diarrhea (19). Experimental models exist for the first three associations cited above (11, 26, 37, 47). Like LukE-LukD, a series of toxins have recently been characterized that belong to the two major families of staphylococcal toxins: pore-forming toxins (36) and enterotoxins (12, 13, 20, 28, 40, 45, 50, 52). Another toxin, the epidermis cell differentiation inhibitor (EDIN), ADP-ribosylates RhoE and Rnd3, two small GTP-binding proteins (46, 49), but its role in staphylococcal virulence remains to be identified. In fact, clinical studies of S. aureus collections including examination of a large panel of toxins are generally lacking.

SSSS and bullous impetigo primarily affect neonates (6 to 16 days), young children, and adults with immunodeficiencies (23). Splitting of the granular cell layer in the epidermis constitutes the major clinical symptom of the diseases (23). It provokes exfoliation of the skin and exposes the patients to secondary infections by opportunistic pathogens (23). However, a scarlatiniform erythroderma may be observed in some cases that are not associated with TSST-1 or enterotoxins (16, 23). The mode of action of epidermolysins remained controversial until recently (23), but at present a proteolytic activity is presumed (1, 38). However, this does not explain the presence of aqueous or purulent exudates in the bullae. These exudates are not observed after subcutaneous injection of epidermolysins in the newborn-mouse experimental model (26, 32).

The aim of this work was to investigate the occurrence of epidermolysins, bicomponent leucotoxins, and enterotoxins in retrospective and prospective S. aureus strains isolated in cases of diagnosed impetigo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteriological analyses and strains.

S. aureus was identified in all samples by conventional methods (21). A set of 168 retrospective and independent strains (up to 1996), previously collected at Strasbourg University Hospital and typed for epidermolysins and PVL (9, 41), were chosen for secondary typing of the other staphylococcal toxins (Table 1). They all originated from patients with skin infections: 83 strains were isolated from young patients (mean age, 2.3 years; range, 1 month to 7 years) with SSSS or bullous impetigo and produced at least one of the epidermolysins, 47 strains were isolated from patients with furuncles or anthrax, and 12 and 26 strains originated from patients with other primary skin infections and secondary skin infections (secondary infections of eczema, ecthyma, and prurigo), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Toxin patterns of groups of S. aureus isolates according to the phenotypic or genotypic identification

| Isolatea | No. of strains | No. producingb:

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET's

|

Leucotoxins

|

Staphylococcal enterotoxins, TSST-1, and EDIN factorb

|

||||||||||||||||

| ETA | ETB | PVL | LukE- LukD | LukE-LukD + ETs | SEA | SEB | SEC | SED | see | seg | seh | sei | sej | set | TSST-1 | edin | ||

| Retrospective isolates | ||||||||||||||||||

| ET producing (impetigo) | 83 | 49 | 57 | 0 | 66 | 66 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 80 | 9 | 80 | 1 | 60 | 2 | 0 |

| PVL producing (furuncles) | 47 | 2 | 1 | 47 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 15 | 4 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4 | ND |

| Primary SI | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 2 | ND |

| Secondary SI | 26 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | ND |

| Prospectives isolates | ||||||||||||||||||

| Impetigo | 48 | 39 | 28 | 1 | 41 | 36 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 47 | 2 | 47 | 1 | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| Furuncles | 22 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 21 | 6 | 21 | 1 | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary SI | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0 | ND |

| Secondary SI | 30 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1 | ND |

SI, staphylococcal infections.

ND, not determined; ETs, epidermolysins.

The prospective study included 108 strains which were collected from separate patients in French Guiana (Cayenne Hospital) between 1995 and 1999. Forty-eight strains were obtained from clinical specimens from patients (mean age, 6.0 years; range, 3 months to 13 years) with clinically diagnosed impetigo only when Streptococcus sp. did not coculture with S. aureus, 22 isolates were obtained from patients with furuncles or anthrax, 8 isolates were obtained from patients with other primary staphylococcal infections, and 30 isolates were obtained from patients with secondary staphylococcal infections. Staphylococcal bullous impetigo was characterized by small flaccid bullae filled with clear yellow fluid; these bullae ruptured and healed, leaving a yellow-brown crust and a nontender lesion (27, 42). Nonbullous impetigo was characterized by superficial erosion of the epidermis without observation of bullae (7, 10). We distinguished 12 cases of bullous impetigo and 36 cases of nonbullous impetigo.

Toxin determination. (i) Enterotoxins A, B, C, and D and TSST-1.

S. aureus cultures were carried out, and toxins were detected using the semiquantitative reversed passive latex agglutination detection kits SET-RPLA and TST-RPLA (Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). These tests were reported to be sensitive and specific, although large amounts of enterotoxin E may be detected as low levels of enterotoxin A (4).

(ii) Enterotoxins E, G, H, I, and J, SET1, and EDIN factor.

Total DNA of isolates contained in agarose plugs (see below) was digested by EcoRI restriction of chromosomal DNA. After 0.8% (wt/vol) agarose gel electrophoresis, the restricted DNAs were transferred to Immobilon P membranes (Millipore) as recommended by the manufacturer, and genes encoding the different toxins were probed by Southern blotting (44) with 5′-32P-labeled specific oligonucleotides with a minimal specific activity of 0.2 μCi/pmol. Although, the egc operon encodes enterotoxins G, I, M, N, and O (20, 28) and the set1 locus comprises five suspected genes encoding superantigens (50), oligonucleotides specific for see, seg, seh, sei, sej, set1, and edin were used for these detections (Table 2). Hybridization was carried out overnight at 55°C in 6× SSPE (20× SSPE is 200 mM NaH2HPO4, 20 mM EDTA, and 3.6 M NaCl, pH 7.0)–5× (vol/vol) Denhardt's solution–0.5% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate–0.1 mg of herring sperm DNA/ml followed by two washes in 0.5× SSPE–0.05% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate at 45°C.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of oligonucleotide probes for staphylococcal enterotoxins

| Target gene | Sequence | GenBank accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| see | 5′-CTTACCGCCAAAGCTGTCT-3′ | M21319 | 8 |

| seg | 5′-AATTATGTGAATGCTCAACCCGAT-3′ | AF064773 | 28 |

| seh | 5′-CATCTACCCAAACATTAGCACC-3′ | U11702 | 39 |

| sei | 5′-CTCAAGGTGATATTGGTGTAGG-3′ | AF064774 | 28 |

| sej | 5′-GGTATCTCTGAAAAGATAATGAC-3′ | AF053140 | 51 |

| set | 5′-AGATCTCAACGTTTCATCGTTAAGCTGC-3′ | AF094826 | 49 |

| edin | 5′-TGGTCCATTAAGACTCGCAGGTGGA-3′ | M63917 | 45 |

(iii) Bicomponent leucotoxins and epidermolysins.

The different leucotoxins (PVL, LukE-LukD, LukM-LukF′-PV, and the gamma-hemolysin proteins HlgA, HlgB, and HlgC) and epidermolysins A and B were evident in culture supernatants after 18 h of growth in YCP medium (18) by radial gel immunodiffusion with component-specific rabbit polyclonal and affinity-purified antibodies.

Phage typing.

Phage types from susceptibilities to phage groups I (types 29, 52, 52A, 79, and 80), II (types 3A, 3B, 55, and 71), and III (types 6, 42E, 47, 53, 54, 75, 77, 83A, 84, and 85) and four unclassified phages, 81, 94, 95, and 96, were classified. For this purpose, the critical dilution and a 100-fold-concentrated dilution of each phage were used, according to the method of Blair and Williams (3). Phage susceptibilities were given in that work as susceptibilities to a phage group(s) on the basis of the most concentrated phage dilution.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE).

S. aureus strains at mid-exponential phase in 25 ml of TY medium (1.6% [wt/vol] BioTrypcase, 1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 0.5% [wt/vol] NaCl) were embedded in agarose plugs as previously described (35). After lysis for 18 h at 56°C, the plugs were washed and stored at 4°C in 10 mM Tris-HCl–1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0. DNA macrorestriction was accomplished with SmaI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The agarose plugs (2.5 by 5.0 by 1 mm) were equilibrated in 300 μl of restriction enzyme buffer for 30 min at 0°C. They were incubated for 4 h at room temperature in 60 μl of restriction buffer with 10 U of enzyme. Electrophoresis was performed at 12°C with a Beckman Geneline transverse alternating-field electrophoresis (TAFE) system at 150 mA in 0.5× TAFE buffer (20× TAFE buffer is 0.2 M Tris base, 10 mM free acid EDTA, and 87 mM CH3COOH, pH 8.2) in a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel. Electrophoresis of SmaI DNA fragments began with 2-s pulses for 1 h, followed by 14-s pulses for 1 h, 12-s pulses for 1.5 h, 10-s pulses for 2.5 h, 8-s pulses for 6 h, and 6-s pulses for 6 h. Lambda PFG Marker (New England Biolabs) was used as a molecular marker. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV transillumination (Fig. 1). Pulsotypes (Fig. 2 and 3) were compared and classified in a dendrogram using the Dice coefficient and the unweighted pair group with arithmetic mean clustering methods provided by Molecular Analyst (version 1.5) and Fingerprinting (version 1.12) software (Bio-Rad, Ivry sur Seine, France).

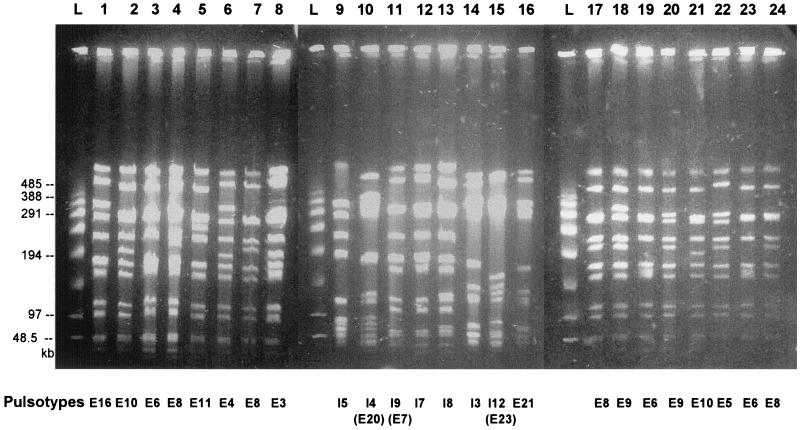

FIG. 1.

Three PFGE gels of 24 independent S. aureus isolates from patients with impetigo with correspondences of pulsotypes (bottom) in both retrospective and prospective series; schematics of the pulsotypes are shown in Fig. 2 and 3. Ladders (L) were obtained from statistic oligomers of bacteriophage lambda DNA (New England Biolabs).

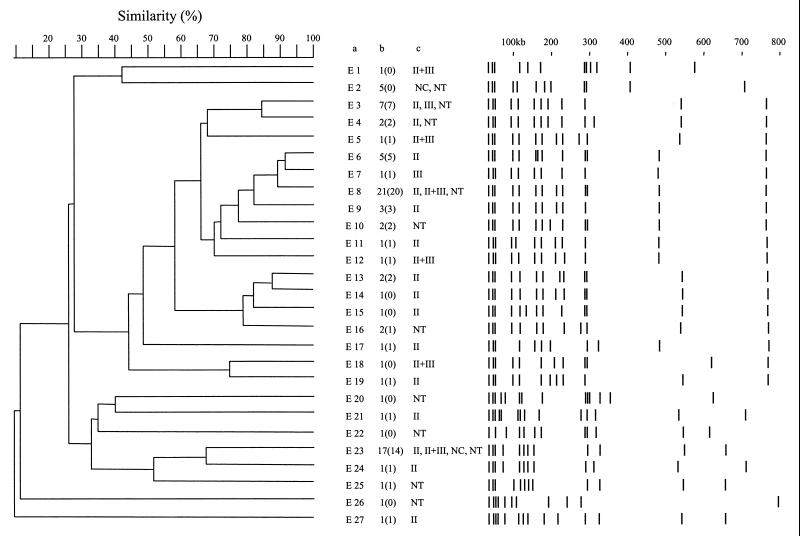

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation and computer-aided dendrogram analysis of the 83 SmaI pulsotypes of S. aureus DNA from strains producing at least one epidermolysin and isolated from patients with impetigo in metropolitan France. Columns: a, pulsotype numbers; b, number of isolates corresponding to each pulsotype (numbers in parentheses are the numbers of isolates producing at least one epidermolysin and LukE-LukD); c, different phage groups, with sensitivities of isolates distinguished in each pulsotype (NC, nonclassified phages 81, 94, 95, and 96; NT, nontypeable isolate).

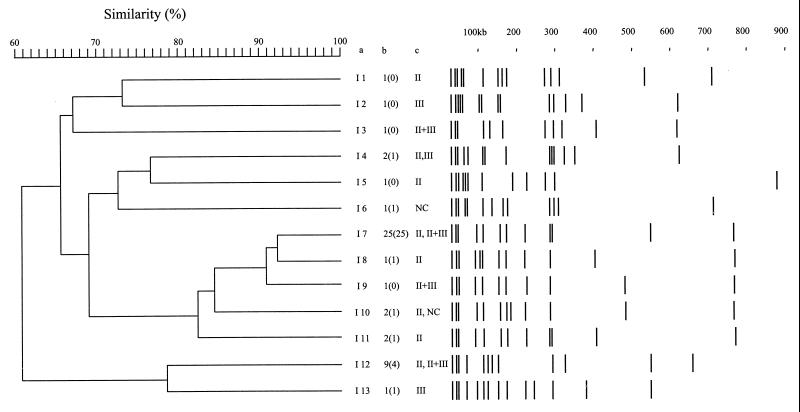

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation and computer-aided dendrogram analysis of the 48 SmaI pulsotypes of S. aureus DNA from strains originating from patients with impetigo in French Guiana. Columns: a, pulsotype numbers; b, number of isolates corresponding to each pulsotype (numbers in parentheses are the numbers of isolates producing at least one epidermolysin and LukE-LukD); c, sensitivity of isolates distinguished in each pulsotype to phages belonging to phage groups (NC, nonclassified phages 81, 94, 95, and 96).

RESULTS

Production of toxins by isolates.

The results of toxin production are summarized in Table 1. Among the 168 retrospective isolates, 66 out of 83 isolates (79%) which originated from patients with impetigo and produced at least one epidermolysin also produced LukE-LukD. Only three (6%) of the 47 strains isolated from furuncles and positive for PVL production also produced epidermolysins, but 13 of 47 (28%) produced LukE-LukD. Only 5 of 13 isolates (38%) from patients with other primary staphylococcal infections produced this toxin. The last two frequencies were not different from the previous LukE-LukD production by routine clinical isolates (18). Production of LukE-LukD was significantly different in isolates from patients with impetigo and those from patients with the other primary skin infections (P < 0.001). Curiously, 16 of 26 isolates (61%) from patients with the secondary staphylococcal infections produced LukE-LukD. However, no significant association was seen between levels of expression of epidermolysins or PVL and LukE-LukD for this group of clinical isolates.

Among the 108 isolates included in the prospective study, 42 of 48 isolates (87%) originating from patients with impetigo produced at least one of the epidermolysins: 14 were only epidermolysin A+ (ETA+), 3 were ETB+, and 25 produced both toxins. All 12 isolates from patients with bullous impetigo produced at least one epidermolysin, and 30 of 36 isolates (83%) from patients with nonbullous impetigo were epidermolysin producers. There was no significant difference between the two types of staphylococcal impetigo in epidermolysin production (P > 0.05). Forty-one (85%) of these isolates from patients with impetigo produced LukE-LukD, and 36 (75%) produced a combination of the two kinds of toxins. Once again, among the prospective furuncle isolates, 20 produced PVL, while only one produced ETA and 11 produced LukE-LukD. Among isolates from patients with other primary and secondary staphylococcal infections, only four produced both an epidermolysin and LukE-LukD. Whatever group of prospective isolates was considered, the association of an epidermolysin and LukE-LukD with isolates responsible for impetigo was significant (P < 0.001).

An enlarged panel of enterotoxins and TSST-1 were checked by phenotypic characterization or DNA hybridization against these isolates from patients with impetigo (Table 1). In fact, 80 of 83 retrospective isolates and 47 of 48 prospective isolates produced at least one of the toxins. All of the prospective furuncle isolates also produced one of the enterotoxins or TSST-1. However, as was recently reported for two sets of clinical isolates (20, 49), the set and egc loci were frequently present (Table 1). Except for the frequent presence of set and egc, enterotoxin B was produced by 52% of the prospective isolates from patients with impetigo, whereas it was produced by only 7% of the isolates in the retrospective group. The difference between the two groups of strains was significant (P < 0.005). Enterotoxin B was produced by 32 and 27% of retrospective and prospective isolates from furuncles, respectively. The locus seh (40) was found in 11% of the same retrospective isolates and in 4% of the prospective ones. The same locus was present in 27% of the prospective isolates from furuncles. No specific association of the clinical isolates was evident with either the last two enterotoxins or any other. From these toxin identifications, the low prevalence of TSST-1 within isolates of cutaneous origin was apparent, especially in prospective isolates. This may confirm the previous observation by Lina et al. (24). Among the isolates studied, none harbored the gene encoding the EDIN factor. All retrospective and prospective isolates produced gamma-hemolysin, and none produced LukM-LukF′-PV.

Phage group sensitivity.

Among the isolates originating from patients with impetigo, none were sensitive to phages of group I, whereas 50 and 68% of the retrospective and prospective isolates from patients with impetigo, respectively, were sensitive to from one to all phages belonging to group II only. Sensitivity to the 3C phage was the most frequent (64% of these clinical samples). The strains were not frequently sensitive to group III phages (4 and 7%, respectively) or to unclassified phages (2 and 6%, respectively). However, isolates sensitive to phages of both groups II and III were more abundant, since they represented 12 and 23% of the retrospective and prospective isolates, respectively. Finally, nontypeable strains were more frequent in the retrospective collection (32%) and absent in the prospective collection. As previously reported (33), isolates from furuncles were sensitive to group II (15%) and group III (25%) phages or unclassified phages (60%), and a similar distribution was observed for isolates from patients with other primary or secondary staphylococcal infections.

Differentiation of strains by DNA PFGE fingerprinting.

DNA of isolates from retrospective and prospective cases of impetigo were analyzed by SmaI macrorestriction and PFGE (Fig. 1). Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the 27 different pulsotypes identified from the retrospective isolates. The number of isolates corresponding to each pulsotype is indicated in column B. Taking into account the profiles obtained for three independent isolates tested on both single and different gels, standard deviations of ±5% were recorded for the various DNA fragments.

For retrospective isolates, the profiles showed 8 to 13 DNA fragments greater than 50 kb (Fig. 2). The profile E8 was the most frequently encountered with 21 isolates (25.3%), followed by profile E23 with 17 isolates (20.5%) and profile E3 with 5 isolates (8.4%). Seventeen profiles corresponded to 17 isolates. When clusters of isolates with pulsotype similarity coefficients greater than 80% were considered, three clusters could be defined in this collection. Cluster I contained pulsotypes E3 and E4, which differed in only one DNA fragment of 315 kb. Cluster II contained pulsotypes E6, E7, E8, and E9. Pulsotypes E6, E7, and E8 differed from each other in the presence and lengths of two DNA fragments. Pulsotype E9 differed from E8 only in the presence of one 290-kb fragment. Cluster III contained pulsotypes E13, E14, and E15, which differed from each other in the length of one DNA fragment, from 230 to 140 kb. However, in the defined cluster I, six out of the seven isolates bearing the E3 pulsotype produced the chromosomal ETA, and only one of the two isolates classified in E4 produced the chromosomal enterotoxin A. In cluster II, 11 out of the 21 isolates from the E8 pulsotype produced ETA, 20 isolates produced the chromosomal LukE-LukD, 15 isolates had the set locus, and only 4 isolates produced SEH. However, none of the isolates in the E6 or E9 pulsotype produced ETA. The isolates corresponding to cluster III showed more heterogeneity in toxin production, since one of the two isolates from pulsotype E13 produced ETA while both produced ETB and LukE-LukD, but the isolate presenting the pattern E14 did not produce LukE-LukD and that corresponding to E15 produced only ETB. Furthermore, among the 17 isolates presenting the E23 pulsotype, all produced ETA but only 14 produced LukE-LukD and 15 possessed the set locus.

For prospective isolates from patients with impetigo, 13 profiles that displayed between 9 and 13 fragments of more than 50 kb were observed (Fig. 3). The profiles I7 and I12 were the most frequent with 25 (52%) and 9 (19%) isolates, respectively. Isolates bearing these two pulsotypes were collected during the 5 years of the prospective study. Out of these isolate-generated pulsotypes, only one cluster containing pulsotypes I7, I8, I9, I10, and I11 could be defined, representing 65% of the isolates. The corresponding patterns differed from each other in the location or presence of DNA fragments whose lengths were about 110, 190, 230, 410, and 520 kb. All isolates whose DNA belonged to pulsotype I7 produced ETA and LukE-LukD, and 23 of the 25 isolates had the set locus. Among these isolates, 22 produced ETB and 16 produced SEB, whose encoding genes are carried by plasmids. The isolate corresponding to fingerprint I9 did not produce LukE-LukD, and only one of the two isolates classified as I10 produced ETA. Comparison of the isolates from the retrospective and prospective collections (Fig. 2 and 3) indicated considerable similarity between pulsotypes E20 and I4, E7 and I9, and E23 and I12. However, the E20 isolate produced ETB whereas the two I4 isolates both produced ETA, ETB, and LukE-LukD. Similarly, the E7 isolate produced ETA, ETB, and LukE-LukD, while the I9 isolate produced only ETB. All 26 isolates classified as pulsotypes E23 and I12 produced ETA, and none produced ETB; 15 of 17 isolates from the prospective study and 6 of 9 isolates from the retrospective study produced LukE-LukD. Isolates harboring a frequently-encountered pulsotype were further discriminated by phage typing, being sensitive to phages of different groups (Fig. 2 and 3). No strict correlation was found between retrospective and prospective isolates harboring similar pulsotypes and their respective phage types. Finally, as indicated in Fig. 2 and 3, 19 out of the 27 retrospective and 8 out of the 13 prospective pulsotypes contained isolates that produced both epidermolysins and LukE-LukD. Thus, toxin production was not concentrated among isolates classified in frequently encountered pulsotypes. It can be seen that among the pulsotypes that were comparable in the two series (see above), only E20 and I9 did not produce both toxins, but the two patterns were not comparable.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have characterized new compounds secreted by S. aureus that belong to two of its major families of toxins: superantigens (12) and β-sheet-rich pore-forming toxins (36). Recently, enterotoxin K (29) and enterotoxin L within a putative pathogenicity island from a bovine S. aureus isolate encoding multiple superantigens (13) were characterized. Concurrently, a growing number of adhesion factors and regulatory systems (6, 14, 25, 30, 51) have been identified. Considering the multiple forms and sites of staphylococcal infections, it is likely that these bacteria are well equipped to sense environmental conditions and to regulate expression of virulence factors for colonization, impairing immunological defenses, multiplication, and spreading.

Among these infections, only a few were associated with a defined toxin. In the case of impetigo or SSSS, the action of epidermolysins does not explain all the symptoms observed. These toxins were not found for isolates from blood cultures or colonized patients (31). Epidermolysins were previously considered serine proteases on the basis of sequence homologies and esterase activity (37). This activity was confirmed by structure-function relationship studies (5), but a concurrent rationale of a superantigenic activity (48) was advanced based on the fact that the bacteria were not necessarily found in all the skin bullae observed in SSSS. However, detection of the toxin in these bullae was never undertaken. Finally, Rago et al. (38) further investigated the topic and reported that the mitogenic activity associated with epidermolysins was not responsible for the lesions observed in the experimental model, compared to the esterase activity. Schlievert et al. identified a proteolytic activity that could be exerted on α- and β-melanoma-stimulating hormones (43). More conclusively, the demonstration of a cleavage of desmoglein (1), a protein constituting desmosomes, provided an explanation for the splitting of tissues within the epidermis. However, proteolytic activity does not explain all of the symptoms encountered in impetigo or SSSS, particularly the local inflammation and the exudates often contained in bullae. Gemmel (16) suggested that other factors could be involved in the pathogenesis of impetigo, since injection of pure epidermolysins in neonatal mice does not cause erythema. These different features prompted us to examine isolates from patients with impetigo for a large number of toxins.

First, a prospective study in Guiana which involved young infants in ambulatory practice showed that epidermolysins A and B were very frequently (86%) produced by isolates originating from patients with impetigo. This was similar to results in a retrospective study (79%). These frequencies were significantly different for epidermolysins from isolates from patients with other primary or secondary staphylococcal infections. Once again, isolates from furuncles in French Guiana were associated with production of PVL, as was reported for European isolates from northeastern France (9) and African isolates (2). Diagnosis is a critical matter for impetigo. A majority of cases in neonates produce bullae that are more or less extended and multifocused and are generally considered SSSS or localized SSSS. However, there are cases where no bullae are observed or are evident after historical investigation of the infection. Nevertheless, in this work, S. aureus was found to produce epidermolysins in so-called nonbullous impetigo. In any case, diagnosis of impetigo has to be clinically distinguished from toxic shock syndrome or staphylococcal scarlet fever (24). There are several reasons why S. aureus isolates sampled from patients with impetigo may not always produce epidermolysin A or B: (i) two kinds of isolates might colonize the lesions, while only one was selected; (ii) an isolate of Streptococcus pyogenes might in fact have been responsible for some lesions but was not recovered for identification; (iii) S. aureus may produce compounds other than epidermolysins with identical functions. However, although the role of epidermolysins in impetigo is supported by epidemiological observations (22, 23), experimental models (26), and in vitro studies (17), the only association with another staphylococcal leucotoxin was that with LukE-LukD leucotoxin. In fact, 78% of all tested isolates from patients with impetigo produced at least one of the epidermolysins and LukE-LukD. The corresponding loci were not genetically linked with LukE-LukD, which was produced by 33% of 146 routine hospital isolates or nasal carriers (while epidermolysins were produced by 1% of isolates of the same collection [19]) and by isolates from other staphylococcal skin infections (primary and secondary). Differences were significant (P < 0.001) between occurrences of both toxins when isolates were from patients with impetigo or when patients were concerned by other infections (18, 19, 31).

Conversely, no particular association of the isolates was found with the enterotoxins tested. As reported previously for routine isolates (50), egc and set operons were found in most isolates from patients with impetigo or primary staphylococcal infections in the prospective collection. Most other enterotoxins were rarely produced, except enterotoxin B, which was more frequent in the prospective than in the retrospective isolates from patients with impetigo. These observation differed slightly from data postulating that strains isolated in SSSS rarely produce toxins other than epidermolysins (24). Production of the ADP-ribosylating toxin EDIN factor was not observed in isolates from patients with impetigo or in those from patients with furuncles (prospective) or other skin infections.

As previously reported (22), isolates from patients with impetigo are sensitive to some group II phages (72%) or nontypeable phages (20%). PFGE fingerprinting of DNAs revealed a significant polymorphism within isolates from patients with impetigo (Fig. 1 to 3). However, several fingerprints, like PFGE patterns E8 and E23, comprised up to 38% of isolates in the retrospective study. In fact, the isolates distributed in these profiles were further distinguished by phage typing, and by toxin typing as well (Fig. 2 and 3). These isolates were distinguished by their enterotoxins, e.g., SEB and SEH or set. Finally, 19 out of the 27 retrospective and 8 out of the 13 prospective pulsotypes contained isolates that may produce one epidermolysin and LukE-LukD, a total of 26 of 37 (70%) different pulsotypes, accounting for the significance of the association. Moreover, analysis of PFGE patterns of the 20 prospective isolates associated with furuncles and producing PVL showed 10 profiles (data not shown), among which 5 were comparable to E3, E9, E16, E21, and I11, indicating that a given pulsotype cannot determine the toxin content of an isolate and that toxin typing may be critical to discriminate among previously PFGE-labeled isolates. Therefore, the notion of clonality of isolates having comparable PFGE profiles may be relative and would benefit from confirmation by other investigations.

In this study, of the 25 isolates harboring the I7 pulsotype, only 3 originated from members of the same family, and other isolates actually did not suggest any evident link. Since the different cases included in this study seemed independent and corresponded to ambulatory practice that excluded hospital or community epidemics, the existence of related or endemic clones that produce both epidermolysins and LukE-LukD is suggested. Nevertheless, a majority of different clones associated with impetigo produced both kinds of toxins. The fact that, except for the association of epidermolysins and LukE-LukD, no common toxin pattern was evident within the two populations of isolates or within a group of isolates having a frequently encountered pulsotype strengthens the significance of this association in cases of impetigo.

Until now, correlation of LukE-LukD with some of the clinical symptoms associated with SSSS has proved difficult. It was found that LukE-LukD could permeate or lyse human polymorphonuclear cells from about one out of five donors (18). This member of the bicomponent leucotoxin family, together with enterotoxin A, was clinically associated with postantibiotic diarrhea with pure or predominant S. aureus (19) infection. Its intradermal injection may also induce dermonecrosis of rabbit skin (18). Unfortunately, epidermolysins are not active on rabbit neonates and LukE-LukD is not very active in the skin of newborn mice (G. Prévost, personal communication). Recently, Gauduchon et al. (15) showed the dependence of the specific binding sites of PVL on the systems controlled by protein kinase C. The possibility that LukE-LukD is a leucotoxin more specialized for specifically maturated cells cannot be excluded. This would corroborate epidemiological observations and explain the purulent exudates observed in impetigo bullae or erosive manifestations. There is a lack of completely satisfying experimental animal models for epidermolysin and LukE-LukD and possibly also for the mitogenic activity of epidermolysins tested in the lymphocytes of rabbits (38).

In conclusion, epidermolysins and LukE-LukD were epidemiologically associated with S. aureus sampled from patients with impetigo in two collections which were independent in time and geography. S. aureus may use combinations of virulence factors to originate a clinical syndrome and possibly to contribute to bacterial spreading. Further investigations are needed to define the target of the LukE-LukD leucotoxin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We greatly appreciate the technical assistance of Daniel Keller and A.-M. Freyd from the Institute of Hygiene—Strasbourg. We thank N. Boord for help with English.

This work was supported by grant EA-1318 from Direction de la Recherche et des Etudes Doctorales.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amagai M, Matsuyoshi N, Wang Z H, Andl C, Stanley J R. Toxin in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome targets desmoglein 1. Nat Med. 2000;6:1275–1277. doi: 10.1038/81385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baba Moussa L, Sanni A, Dagnra A Y, Anagonou S, Prince David M, Edoh V, Befort J J, Prévost G, Monteil H. Approche épidémiologique de l'antibiorésistance et de la production de leucotoxines par les souches de Staphylococcus aureus isolées en Afrique de l'Ouest. Med Mal Infect. 1999;29:689–696. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair J E, Williams R E O. Phage typing of staphylococci. Bull W H O. 1961;24:771–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brett M. Kits for the detection of some bacterial food poisoning toxins: problems, pitfalls and benefits. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:S110–S118. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1998.0840s1110s.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavarelli J, Prévost G, Bourguet W, Moulinier L, Chevrier B, Delagoutte B, Bilwes A, Mourey L, Rifai S, Piémont Y, Moras D. The structure of Staphylococcus aureus epidermolytic toxin A, an atypic serine protease, at 1.7 Å resolution. Structure. 1997;5:813–824. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung A L, Koomey J M, Butler C A, Projan S J, Fischetti V A. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus sar distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coskey R J, Coskey L A. Diagnosis and treatment of impetigo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:62–63. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couch J, Soltis M, Betley M. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of the type E staphylococcal enterotoxin gene. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2954–2960. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.2954-2960.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Couppié P, Cribier B, Prévost G. Leukocidin from Staphylococcus aureus and cutaneous infections: an epidemiologic study. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1208–1209. doi: 10.1001/archderm.130.9.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couppié P, Sainte-Marie D, Prévost G, Gravet A, Clyti E, Moreau B, Monteil H, Pradinaud R. Impetigo in French Guiana. A clinical, bacteriological, toxicological and sensitivity to antibiotics study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1998;125:688–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cribier B, Prévost G, Couppié P, Finck-Barbançon V, Grosshans E, Piémont Y. Staphylococcus aureus leukocidin: a new virulence factor in cutaneous infections? An epidemiological and experimental study. Dermatology. 1992;185:175–180. doi: 10.1159/000247443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinges M M, Orwin P M, Schlievert P M. Exotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:16–34. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.16-34.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald J R, Monday S R, Foster T J, Bohach G A, Hartigan P J, Meaney W J, Smyth C J. Characterization of a putative pathogenicity island from bovine Staphylococcus aureus encoding multiple superantigens. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:63–70. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.1.63-70.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster T J, Hook M. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:484–488. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gauduchon V, Werner S, Prévost G, Monteil H, Colin D A. Flow cytometric determination of Panton-Valentine leucocidin S component binding. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2390–2395. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2390-2395.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemmell C G. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:318–327. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-5-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentilhomme E, Faure M, Piémont Y, Binder P, Thivolet J. Action of staphylococcal exfoliative toxins on epidermal cell cultures and organotypic skin. J Dermatol. 1990;17:526–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1990.tb01689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravet A, Colin D A, Keller D, Girardot R, Monteil H, Prévost G. Characterization of a novel structural member, LukE-LukD, of the bi-component staphylococcal leucotoxins family. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gravet A, Rondeau M, Harf-Monteil C, Grunenberger F, Monteil H, Scheftel J M, Prévost G. Predominant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from antibiotic-associated diarrhea is clinically relevant and produces enterotoxin A and the bicomponent toxin LukE-LukD. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:4012–4019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.12.4012-4019.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarraud S, Peyrat M A, Lim A, Tristan A, Bes M, Mougel C, Etienne J, Vandenesch F, Bonneville M, Lina G. egc, a highly prevalent operon of enterotoxin gene, forms a putative nursery of superantigens in Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2001;166:669–677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.669. . (Erratum, 166:4260.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloos W E, Bannerman T L. Staphylococcus and Micrococcus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 7th ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1999. pp. 264–282. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo I, Sakurai S, Sarai Y, Futaki S. Two serotypes of exfoliatin and their distribution in staphylococcal strains isolated from patients with scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:397–400. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.5.397-400.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladhani S, Joannou C L, Lochrie D P, Evans R W, Poston S M. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:224–242. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.2.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lina G, Gillet Y, Vandenesch F, Jones M E, Floret D, Etienne J. Toxin involvement in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1369–1373. doi: 10.1086/516129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McNamara P J, Milligan-Monroe K C, Khalili S, Proctor R A. Identification, cloning, and initial characterization of rot, a locus encoding a regulator of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3197–3203. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3197-3203.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melish M E, Glasgow L A. The staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome: development of an experimental model. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:1114–1119. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197005142822002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melish M E, Glasgow L A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: the expanded clinical syndrome. J Pediatr. 1971;78:958–967. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(71)80425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munson S H, Tremaine M T, Betley M J, Welch R A. Identification and characterization of staphylococcal enterotoxin types G and I from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3337–3348. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3337-3348.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orwin P M, Leung D Y M, Donahue H L, Novick R P, Schlievert P M. Biochemical and biological properties of staphylococcal enterotoxin K. Infect Immun. 2001;69:360–366. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.360-366.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng H L, Novick R P, Kreiswirth B, Kornblum J, Schlievert P M. Cloning, characterization, and sequencing of an accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4365–4372. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4365-4372.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piémont Y, Rasoamananjara D, Fouace J M, Bruce T. Epidemiological investigation of exfoliative toxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus strains in hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:417–420. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.3.417-420.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piémont Y, Rifai S, Monteil H. Les exfoliatines de Staphylococcus aureus. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1988;86:263–296. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prévost G, Couppié P, Prévost P, Gayet S, Petiau P, Cribier B, Monteil H, Piémont Y. Epidemiological data on Panton-Valentine leucocidin producing Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Med Microbiol. 1995;42:237–245. doi: 10.1099/00222615-42-4-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prévost G, Cribier B, Couppié P, Petiau P, Supersac G, Finck-Barbançon V, Monteil H, Piémont Y. Panton-Valentine leucocidin and gamma-hemolysin from Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 49775 are encoded by distinct genetic loci and have different biological activities. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4121–4129. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4121-4129.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prévost G, Jaulhac B, Piémont Y. DNA fingerprinting by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis is more effective than ribotyping in distinguishing among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:967–973. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.4.967-973.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prévost G, Mourey L, Colin D A, Menestrina G. Staphylococcal pore-forming toxins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;257:53–83. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56508-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prévost G, Rifai S, Chaix M L, Piémont Y. Functional evidence that the Ser-195 residue of staphylococcal exfoliative toxin A is essential for biological activity. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3337–3339. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3337-3339.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rago J V, Vath G M, Bohach G A, Ohlendorf D H, Schlievert P M. Mutational analysis of the superantigen staphylococcal exfoliative toxin A (ETA) J Immunol. 2000;164:2207–2213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rago J V, Vath G M, Tripp T J, Bohach G A, Ohlendorf D H, Schlievert P M. Staphylococcal exfoliative toxins cleave alpha- and beta-melanocyte-stimulating hormones. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2366–2368. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2366-2368.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren K, Bannan J D, Pancholi V, Cheung A L, Robbins J C, Fischetti V A, Zabriskie J B. Characterization and biological properties of a new staphylococcal exotoxin. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1675–1683. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rifai S, Barbançon V, Prévost G, Piémont Y. Synthetic exfoliative toxin A and B DNA probes for detection of toxigenic Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:504–506. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.504-506.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogolsky M. Non-enteric toxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Rev. 1979;43:320–360. doi: 10.1128/mr.43.3.320-360.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schlievert P M, Jablonski L M, Roggiani M, Sadler I, Callantine S, Mitchell D T, Ohlendorf D H, Bohach G A. Pyrogenic toxin superantigen site specificity in toxic shock syndrome and food poisoning in animals. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3630–3634. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3630-3634.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Southern E. Detection of specific sequence among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su Y C, Wong A C. Identification and purification of a new staphylococcal enterotoxin, H. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1438–1443. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1438-1443.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugai M, Enomoto T, Hashimoto K, Matsumoto K, Matsuo Y, Ohgai H, Hong Y M, Inoue S, Yoshikawa K, Suginaka H. A novel epidermal cell differentiation inhibitor (EDIN): purification and characterization from Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:92–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todd J K. Staphylococcal toxin syndromes. Annu Rev Med. 1985;36:337–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.36.020185.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vath G M, Earhart C A, Monie D D, Iandolo J J, Schlievert P M, Ohlendorf D H. The crystal structure of exfoliative toxin B: a superantigen with enzymatic activity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10239–10246. doi: 10.1021/bi990721e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wilde C, Chhatwal G S, Schmalzing G, Aktories K, Just I. A novel C3-like ADP-ribosyltransferase from Staphylococcus aureus modifying RhoE and Rnd3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9537–9542. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams R J, Ward J M, Henderson B, Poole S, O'Hara B P, Wilson M, Nair S P. Identification of a novel gene cluster encoding staphylococcal exotoxin-like proteins: characterization of the prototypic gene and its protein product, SET1. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4407–4415. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4407-4415.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yarwood J M, McCormick J K, Schlievert P M. Identification of a novel two-component regulatory system that acts in global regulation of virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1113–1123. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1113-1123.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, Iandolo J J, Stewart G C. The enterotoxin D plasmid of Staphylococcus aureus encodes a second enterotoxin determinant (sej) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;168:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]