Abstract

We reported previously on the complete sequence of hepatitis E virus (HEV) genotype 4, isolated from patients with sporadic cases of acute HEV infection in China. At least eight HEV genotypes have now been described worldwide, and further isolates await classification. Current immunoassays for the detection of anti-HEV antibodies are based on polypeptides from genotypes 1 and 2 only and may be inadequate for the reliable detection of other genotypes. Because genotypes 1 and 4 predominate in China, we wished to investigate the antigenic reactivities of HEV genotype 4 proteins. Four overlapping regions of open reading frame 2 (ORF2) (FB5, amino acids [aa] 1 to 130; E4, aa 67 to 308; F2-2, aa 288 to 461; E5, aa 414 to 672) and the entire ORF3 product were expressed in Escherichia coli as fusion proteins. Enzyme immunoassays based on each of the five purified polypeptides were evaluated with sera from patients with sporadic cases of acute HEV infection. Individual immunoassays derived from HEV genotype 4 detected more cases of acute hepatitis E than a commercial assay. Some serum samples, which were positive for anti-HEV immunoglobulin G only by assays based on HEV genotype 4, were positive for HEV RNA by reverse transcription-PCR. Polypeptide FB5, from the N terminus of ORF2, had the greatest immunoreactivity with sera from patients with acute hepatitis E. These data indicate that the N terminus of ORF2 may provide epitopes which are highly reactive with acute-phase sera and that assays based on genotypes 1 and 2 alone may be inadequate for the detection of HEV infection in China, where sporadic cases of HEV infection are caused predominantly by HEV genotypes 4 and 1.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV), the principal cause of enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis, was previously considered endemic only in developing countries, including countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Recently, however, several HEV isolates have been cloned from patients with acute hepatitis who live in countries where HEV was not believed to be endemic and who had no history of travel to an area of endemicity (11, 19, 25, 26), and therefore, the virus seems to be distributed worldwide. HEV isolates from patients with sporadic cases of HEV infection in industrialized countries were found to belong to novel genotypes (genotypes 3 and 5 to 8) which are distinct from those described from the developing world. The extent to which these infections represent zoonoses (13, 24) and the effects of genotype on pathogenesis are not clear. However, it should be emphasized that only isolated cases of infection with genotypes 3 and 5 to 8 have been described. Worldwide, most HEV infections are caused by genotype 1, while the importance of genotype 4 as a cause of sporadic cases of HEV infection in China is being recognized more and more.

In 1986, an outbreak of hepatitis E occurred in the southern part of the Xinjiang Uighur autonomous region of China (35). A number of HEV isolates were obtained from Xinjiang Uighur (isolates from Kashi, Turfan, and Hetian). The sequences of these isolates are highly conserved and are homologous to those of genotype 1 isolates of the Burmese-like group of viruses (3, 4, 33). More recently, a novel genotype was identified in the sera of patients from various regions of China with a provisional diagnosis of sporadic, acute non-A to non-E hepatitis and was designated HEV genotype 4 (29, 30). Other HEV variants have been reported from the city of Guangzhou in China and Taiwan (14, 16, 31). Determination of the complete sequence of HEV genotype 4 led to the conclusion that additional genotypes of HEV may be endemic in China (29, 30).

HEV is a small, nonenveloped virus that has a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 7.2 kb and that contains three conserved open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes a nonstructural protein, ORF2 encodes a structural (capsid) protein of about 660 amino acids (aa), and ORF3 encodes a protein of about 123 aa, the biological role of which has yet to be elucidated. Several immunoreactive domains have been identified by using linear peptides from the ORF2 and ORF3 gene products (17, 18, 32). Conformational epitopes may also make an important contribution to the generation of immune responses to HEV (21, 23, 28, 34). Commercially available diagnostic assays for anti-HEV antibodies are based on recombinant polypeptides or synthetic peptides derived from ORFs 2 and 3 of the Burmese and Mexican isolates (genotypes 1 and 2, respectively) (10, 32). The ORF2 polypeptides and peptides used in most commercial anti-HEV enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) are from the C terminus, but immunoreactive epitopes have also been identified in the N terminus and the central region of the protein (17, 18).

We failed to detect anti-HEV antibodies in some sera from patients infected with HEV genotype 4 using commercial assays, although some acute-phase samples may have been taken prior to the development of detectable levels of antibody (29). In order to investigate further the immunoreactivities of polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 isolates, four overlapping regions of ORF2 and the entire ORF3 product were expressed in Escherichia coli with a His-Patch Thiofusion expression system. EIAs based on each of the five purified recombinant polypeptides were developed and were evaluated with sera from Chinese patients with acute hepatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sera from patients with sporadic cases of acute hepatitis and blood donors.

Sera were collected from 300 patients attending the Youan Hospital, Beijing, China, with a clinical diagnosis of acute hepatitis. Serological diagnosis was based on the detection of anti-hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV) immunoglobulin M (IgM), hepatitis B virus (HBV) markers (anti-HBV core IgM, HBV surface antigen [HBsAg], HBV e antigen), anti-hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) IgG, and anti-HEV IgG. The anti-HAV IgM and anti-HCV IgG assays were from the Kehua Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China) and are accredited by the Chinese National Reference Laboratory. Assays for anti-HBV core IgM, HBsAg, and HBV e antigen were from DiaSorin s.r.l. (Saluggia, Italy). Anti-HEV IgG was detected by using an assay from Genelabs Inc. (Singapore). This assay is based on recombinant antigens from the carboxyl-terminal portions of the ORF2 (clone 3-2) and ORF3 (clone 4-2) gene products of both the Burmese (genotype 1) and Mexican (genotype 2) prototypes of HEV (32). A total of 104 patients were diagnosed with hepatitis A, 112 patients were diagnosed with hepatitis B, 1 patient was diagnosed with hepatitis C, and 39 patients were diagnosed with hepatitis E. Two patients were coinfected with HBV and HEV, two patients were coinfected with HAV and HBV, and one patient was coinfected with HBV and HCV. The remaining 39 patients were provisionally diagnosed as having non-A to non-E hepatitis.

Control sera were collected from 100 donors from the Beijing blood center and were tested and found to be negative for anti-HEV IgG by two independent assays. The anti-HEV assay from the Kehua Biotechnology Company is based on synthetic peptides from ORF2 (in the region from aa 600 to 660) and ORF3. The assay from the Wantai Pharmaceutical Company (Beijing, China) is based on recombinant polypeptides from ORF2 (aa 621 to 660) and ORF3 (aa 76 to 123) expressed in E. coli as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins. Both assays are based on HEV genotype 1 sequences and are accredited by the Chinese National Reference Laboratory. These 100 serum samples were also negative for HBsAg and antibodies to HCV and human immunodeficiency virus.

Construction of expression plasmids for the entire ORF3 and four overlapping regions of ORF2.

The E. coli vector pThioHis (vectors A, B, and C) (Invitrogen Inc., Groningen, The Netherlands) facilitates the expression of heterologous polypeptides fused to thioredoxin (trxA) and driven by the trc (trp-lac) promoter. The system includes three vectors (vectors A, B, and C; for cloning into each reading frame) to ensure correct fusion, and a modified His-Patch-thioredoxin with a metal binding domain, which enables purification of the products with metal-chelating resins. The following recombinant plasmids were derived from HEV T1 (genotype 4 [30]) and were cloned in pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, Wis.): R11, which contains 902 bp from nucleotides (nt) 4627 to 5529; E4, which contains 725 bp from nt 5343 to 6067; F2-2, which contains 521 bp from nt 6006 to 6526; and E5, which contains 781 bp from nt 6384 to the 3′ end (nt 7164). It should be noted that a single nucleotide insertion in genotype 4 HEV potentially results in an additional 12 residues at the amino terminus of the ORF2 protein and the loss of 10 residues from the amino terminus of the ORF3 protein (12).

The entire ORF3 region (O3) was amplified from plasmid R11 with ORF3 sense primer 1 (5′-GGGGTACCTTTTGCTCCGTGCATG-3′) and ORF3 antisense primer 2 (5′-GGAATTCAGCCGGAGCCACAGCAGTCA-3′), which contain the BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites (in boldface), respectively. The ORF3 PCR product (nt 5161 to 5529) and pThioHis A were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, and the products were ligated.

The 5′ region of ORF2 (polypeptide FB5) was amplified from plasmid R11 with ORF2 sense primer 1 (5′-GAAGATCTACCATGAATAACATGTTCT-3′) and ORF2 antisense primer 2 (5′-GGAATTCAGCCGGAGCCACAGCAGTCA-3′) , which contain the BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites (in boldface), respectively. The PCR product (nt 5146 to 5529, encoding aa 1 to 128 of ORF2) and pThioHis C were digested with BglII and EcoRI and ligated as described above for the ORF3 polypeptide. The three recombinant plasmids E4, F2-2, and E5 were digested with restriction enzymes SacI and SacII in the pGEM-T multiple cloning site flanking the insert. The pThioHis C vector was digested with SacI and SacII and ligated separately to each of the three overlapping fragments. All the constructs were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion.

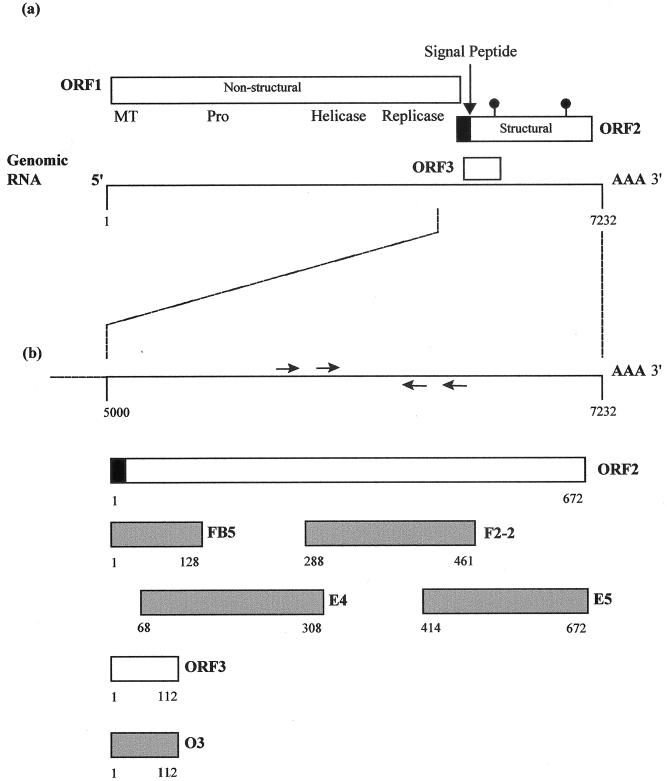

After construction of the expression plasmids, all five target sequences were in the same ORF as the fusion partner (thioredoxin). Polypeptide O3 includes the entire ORF3 product of 112 aa. Polypeptide FB5 includes 128 aa from residues 1 to 128 of ORF2, E4 includes 242 aa from residues 67 to 308, F2-2 includes 174 aa from residues 288 to 461, and E5 includes 259 aa from residues 414 to 672 (Fig. 1). Translation of polypeptide O3 terminates at the stop codon of HEV T1 ORF3, and no residues from the pThioHis vector are fused at the C terminus. Polypeptide O3 comprises 237 aa including 112 aa of target polypeptide and 125 aa from the fusion partner at the N terminus and includes the region equivalent to clone 4-2 in the Genelabs assay. Translation of polypeptide FB5 terminates at a stop codon in the pThioHis plasmid so that polypeptides from the pThioHis vector are fused at both the C and N termini of the target polypeptide. Polypeptide FB5 comprises 274 aa, including 128 aa of target polypeptide, 129 aa from the fusion partner located at the N terminus, and 17 aa from the pThioHis vector at the C terminus.

FIG. 1.

Organization of HEV genotype 4 and locations of sequences expressed as recombinant antigens. (A) Translation strategy and ORFs of HEV genotype 4 (30). The ORF2 product has a signal sequence at the amino terminus (black box) and potential N-linked glycosylation sites (indicated by lollipop-shaped symbols). The 7.5-kb genomic RNA is shown below. (B) Magnification of the 3′ region of the genome and ORFs 2 and 3. Arrows above and below the line representing RNA show the approximate locations of the PCR primers. Shaded boxes below the ORFs indicate the regions expressed in recombinant proteins FB-5, F2-2, E4, E5, and O3.

The E4, F2-2, and E5 fragments in the remaining expression constructs were derived from recombinant pGEM-T plasmids after digestion at the SacI and SacII restriction sites located in the multiple cloning site. Thus, these fragments in the expression plasmids contained small regions from the pGEM-T vector. The translation of polypeptides E4 and F2-2 terminated at the stop codon in the pThioHis plasmid. Polypeptide E4 comprises 399 aa, containing the 127-aa fusion partner, 13 aa from the pGEM vector, the 242-aa HEV ORF2 polypeptide, 2 aa from the pGEM-T vector, and 15 aa from the pThioHis vector. Similarly, polypeptide F2-2 comprises 331 aa: the 127-aa fusion partner, 13 aa from the pGEM-T vector, the 174-aa HEV ORF2 polypeptide, 2 aa from the pGEM-T vector, and 15 aa from the pThioHis vector. The translation of polypeptide E5 terminates at the authentic ORF2 stop codon, and this polypeptide includes the region equivalent to clone 3-2 in the Genelabs assay. It is 399 aa in length and comprises the 127-aa fusion partner, 13 aa from the pGEM-T vector, and 259 aa from the N terminus of HEV T1 ORF2.

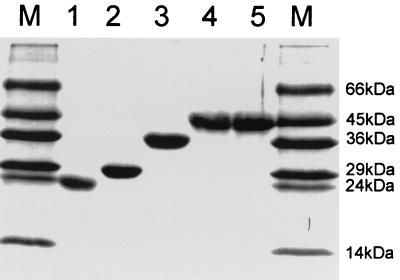

In summary, the predicted lengths of polypeptides O3, FB5, E4, F2-2, and E5 are 237, 276, 398, 330, and 399 aa, respectively, and the expected sizes of the fusion polypeptides are 26, 29, 43, 36, and 43 kDa, respectively. The locations of the regions of ORF2 and ORF3 expressed in these polypeptides are shown in Fig. 1. The bacterial lysates were run on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel, and in each case, they gave a clear band with approximately the expected mobility (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

SDS-PAGE of the five recombinant polypeptides. Lanes 1 to 5, purified O3, FB5, F2-2, E4, and E5 fusion polypeptides, respectively; lanes M: polypeptide molecular mass markers.

Protein expression and purification.

Plasmid-positive bacteria were transferred to 5 ml of Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and were shaken at 37°C. When the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.6, isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 1 mM and the bacteria were shaken at 37°C for a further 5 h. The bacteria were collected by centrifugation, and the ∼0.5-g pellets were resuspended in 3 ml of sonication buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 25 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 50 mM glucose, 10 mg of lysozyme per ml) and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The solution was put on ice, sonicated three times, and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Fractions were run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels to determine whether the proteins were expressed in soluble or insoluble form.

All five proteins were expressed in insoluble form. Approximately 1 g of pelleted protein was suspended in 5 ml of wash buffer (10% Triton X-100, 10 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The washing procedure was repeated, the pellets were dissolved in 8 M urea, and the proteins were purified by reverse-phase chromatography on a C18 column. The column was equilibrated with 3 column volumes of eluent A (0.1% [vol/vol] trifluoroacetic acid) at 200 μl/min. The sample in 8 M urea was diluted in eluent A (1:1) to produce a working solution, loaded onto the column, and eluted with 10% acetonitrile (eluent B). The optical density at 280 nm of the eluate was recorded with a UV detector. The elution step was repeated, and the concentration of acetonitrile in eluent B was increased in 5% increments. The purified protein was then lyophilized for 12 h and redissolved in 8 M urea.

Polypeptides E4 and E5 were successfully purified by reverse-phase chromatography and were freeze-dried. However, polypeptides O3, FB5, and F2-2 could not be purified successfully by this method and were therefore purified by size-exclusion, ion-exchange, and affinity chromatographies. Size-exclusion chromatography was carried out with Sepahcryl S-1000SF equilibrated with buffer I (4 M urea, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.5]). Ten milliliters of lysate in urea was loaded onto the column and was eluted with the same buffer at a rate of 1 ml/min. Two-milliliter samples were collected, and 30 μl from each sample was run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Fractions which gave the desired band by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on 15% polyacrylamide gels were pooled.

Ion-exchange chromatography was then carried out with DEAE-Sepharose equilibrated with buffer II (4 M urea, 10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.5]). The sample was dialyzed twice against buffer II, and 20 ml of the sample was loaded into the column and washed with 2 column volumes of buffer II. The bound protein was eluted with a gradient from 100 ml of buffer II to 100 ml of buffer III (4 M urea, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.5]). Fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 15% polyacrylamide gels, peak fractions were pooled, and the protein was dialyzed against PBS overnight. Finally, affinity chromatography was carried out with the nickel-chelating Sepharose resin (ProBond; Invitrogen Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Following purification, each purified polypeptide was shown to produce only one band on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). The molecular sizes of polypeptides O3, FB5, E4, F2-2, and E5 were approximately those predicted.

Development of EIAs.

Each recombinant protein was dissolved in coating buffer (0.06 M sodium carbonate buffer [pH 9.6]) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml and dialyzed against coating buffer. A total of 100 μl of the coating buffer was added to each well of the microtiter plates, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h. The coating buffer was discarded, and each well was washed three times with washing buffer (0.5% Tween 20 in PBS). A total of 200 μl of blocking buffer (5% [wt/vol] milk powder, 2% [wt/vol] bovine serum albumin in PBS) was added to each well, and the microtiter plates were incubated at 4°C overnight. The blocking buffer was discarded, and each well was washed three times with washing buffer. The microtiter plates were then dried and vacuum sealed. The working dilution of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody, working substrate [50 ml of 0.04 M 2-2′ azino-D1(3-ethylbenthiazoline sulfonic acid) diammonium salt in 5 ml of 0.05 M citrate (pH 4.0) and 20 ìl of 0.5 M H2O2], and stop solution (1 N H2SO4) were provided by the Sino-American Biotechnology Company (Luoyang, China).

One hundred serum samples from volunteer blood donors, which were negative for anti-HEV IgG antibody according to the results of two anti-HEV IgG assays (see above), were tested by the five EIAs. The means and standard deviations of the optical densities for all negative samples were calculated, and the cutoff value was determined as the mean for the negative samples plus 3 standard deviations. To test for anti-HEV, 10 μl of each sample was diluted in 200 μl of sample diluent. A total of 100 μl of the dilution was added to each well, with three negative and two positive control wells included on each plate. The microtiter plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and were then washed three times with washing buffer. A total of 100 μl of the working dilution of peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG antibody was added to each well. The microtiter plates were then incubated at 37°C for 0.5 h and washed three times with washing buffer. A total of 50 μl of working substrate was added to each well, the plate was incubated at 37°C for 15 min, and then 50 μl of stop solution was added to each well. The optical density of each sample was read with an EIA plate reader with a 405-nm filter. Test samples with optical densities equal to or greater than the cutoff value were considered positive for anti-HEV IgG.

Detection of HEV RNA and sequence analysis.

The methods for HEV RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and amplification were those described previously (29), except that the primers used for PCR were those described by Meng et al. (24), as follows: outer sense primer, 5′-AA(CT)TATGC(AC)CAGTACCGGGTTG-3′; outer antisense primer, 5′-CCCTTATCCTGCTGAGCATTCTC-3′; inner sense primer, 5′-GT(CT)ATG(CT)T(CT)TGCATACATGGCT-3′; inner antisense primer, 5′-AGCCGACGAAAT(CT)AATTCTGTC-3′.

The products of PCR amplification were run on 2% agarose gels. Amplicons from positive reactions were excised from the gels, purified with Wizard PCR Preps DNA Purification System (Promega), and cloned into the pGEM-T easy vector (Promega). Recombinant plasmids were purified, and the inserts were sequenced with an ABI Prism dRhodamine terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) and an ABI 310 genetic analyzer.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in the present study have been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide database (accession nos. AJ344171 to AJ344194). Individual sequences were compared to those in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database with the BLAST program (2) and were aligned by use of the PileUp program (Program manual for the GCG package, version 7, Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis., 1991).

RESULTS

Determination of cutoff values for EIAs.

The five purified polypeptides were coated separately onto microtiter plates in order to produce an enzyme immunoassay for each polypeptide. The 100 control serum samples from volunteer blood donors, which were negative for anti-HEV IgG according to assays from the Kehua Biotechnology Company and Wantai Pharmaceutical Company, were tested by each assay; and the means and standard deviations of the optical densities were calculated. The results showed that the mean ± standard deviation optical densities for the negative samples were 0.120 ± 0.062 for O3, 0.115 ± 0.057 for FB5, 0.123 ± 0.063 for E4, 0.112 ± 0.061 for F2-2, and 0.111 ± 0.054 for E5. When the cutoff value was set at the mean optical density plus 3 standard deviations, all control samples were negative. This value was approximately equal to the mean for the three negative controls on each plate plus 0.20, and the cutoff value was set as the mean for the three negative controls plus 0.20.

Detection of antibodies in sera of patients with hepatitis E.

Thirty-nine patients with clinical symptoms of acute hepatitis were diagnosed as having hepatitis E on the basis of detection of antibodies by the Genelabs assay, and two further patients were diagnosed as being coinfected with HBV and HEV. These 41 serum samples were tested by the five EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 (Table 1). The results showed that only one of these serum samples (from patient 261) was negative by all five assays (this sample was also negative for HEV RNA by reverse transcription [RT]-PCR), and we cannot rule out a false-positive reaction for anti-HEV antibody by the Genelabs assay. The assay based on polypeptide FB5 detected anti-HEV antibody in all the samples which were positive for anti-HEV antibody by the Genelabs assay (with the exception of the sample from patient 261), and the assay based on polypeptide O3 was negative for only two other serum samples. The assays based on polypeptides E4 and F2-2 detected antibodies in 28 and 29 of 41 samples, respectively, but the assay based on polypeptide E5 detected antibodies in only 19 of 40 samples. These data indicate that the sensitivity of the EIA based on polypeptide FB5 is comparable to that of the Genelabs assay for the detection of antibodies to HEV.

TABLE 1.

Detection of anti-HEV IgG in the sera of patients with acute hepatitis E by EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4a

| Patient | Sexb | Age (yr) | Ratio of sample optical density to cutoff valuec

|

Detection of RNA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | FB5 | E4 | F2-2 | E5 | G | ||||

| 11 | M | 22 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 6.1 | 4.3 | 1.8 | 2.8 | − |

| 33 | M | 42 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 2.8 | − |

| 41 | M | 44 | 4.2 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.6 | − |

| 75 | M | 44 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 2.3 | − |

| 95 | M | 70 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | − |

| 92 | M | 65 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.7 | − |

| 122 | M | 74 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 3.3 | − |

| 145 | F | 45 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.9 | − |

| 149 | M | 65 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 2.3 | − |

| 152 | F | 43 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | + (1)d |

| 153 | M | 40 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | + (1) |

| 155 | M | 71 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | − |

| 168 | M | 27 | 2.5 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 2.2 | − |

| 176 | M | 73 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.1 | − |

| 177 | M | 52 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 2.3 | − |

| 179 | M | 49 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 3.6 | − |

| 180 | M | 72 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | − |

| 181 | M | 46 | 0.6 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 4.1 | + (4) |

| 185 | M | 48 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 3.4 | + (1) |

| 194 | F | 44 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 2.6 | + (4) |

| 202 | M | 43 | 8.0 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 3.9 | + (4) |

| 213 | M | 48 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 2.3 | − |

| 219 | M | 49 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 3.4 | + (1) |

| 223 | M | 52 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.9 | − |

| 226 | M | 48 | 3.4 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 2.0 | + (1) |

| 241 | F | 23 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.7 | + (4) |

| 248 | M | 40 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 2.8 | − |

| 252 | M | 57 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 1.3 | 3.1 | − |

| 254 | M | 45 | 5.7 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 3.2 | + (4) |

| 261 | F | 17 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 2.2 | − |

| 263 | M | 58 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 3.2 | − |

| 266 | F | 50 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 2.6 | + (4) |

| 272 | M | 43 | 6.8 | 5.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 3.4 | − |

| 273 | M | 52 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 3.4 | + (1) |

| 277 | F | 57 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 2.9 | + (4) |

| 287 | M | 38 | 6.6 | 3.0 | 6.2 | 4.6 | 0.7 | 2.9 | + (4) |

| 290 | M | 67 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 4.9 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | + (1) |

| 292 | M | 26 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 3.3 | + (4) |

| 297 | M | 32 | 3.5 | 5.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 2.8 | + (4) |

| 157e | M | 48 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 | − |

| 210e | M | 41 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.2 | + (4) |

The diagnosis was based on the clinical symptoms and the detection of antibodies by the Genelabs assay (G).

M, male; F, female.

Sera were considered positive when the ratio of the sample optical density to the cutoff value was equal to or greater than 1.0 (shown in boldface).

The genotypes of RT-PCR-positive samples are given in parentheses.

HBV-positive patients with hepatitis E.

Detection of anti-HEV antibodies in the sera of patients with non-E hepatitis.

Sera from 104 patients with hepatitis A, 112 patients with hepatitis B, 1 patient with hepatitis C, 2 patients with hepatitis A and B, 1 patient with hepatitis B and C, and 39 patients with a provisional diagnosis of non-A to non-E hepatitis were also tested by the five EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4. Only 1 of the 104 serum samples from patients with hepatitis A tested positive by the assay based on E4, although this may have been a false-positive result. Similarly, 1 of 112 serum samples from patients with hepatitis B was positive for anti-HEV by four of the five polypeptide-based assays (only the E5-based assay was negative), and it seems likely that the patient from whom this sample was obtained was coinfected with HBV and HEV.

Ten serum samples from the patients in the non-A to non-E hepatitis group, which were negative for anti-HEV IgG by the Genelabs EIA, were positive by at least one of the five EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 (Table 2). The assay based on polypeptide FB5 detected antibodies in all 10 serum samples, and this result was accompanied by a positive result by at least one of the other four assays for 9 of the serum samples. The single serum sample that was reactive only with polypeptide FB5 was also positive for HEV RNA. The assays based on polypeptides E4 and F2-2 detected antibodies in 7 and 8 of the 10 serum samples, respectively, but that based on polypeptide E5 detected antibodies in only 4 of the 10 serum samples. In contrast to its performance with known anti-HEV-positive sera, the assay based on polypeptide O3 detected antibodies only in 3 of 10 serum samples from patients diagnosed as having non-A to non-E hepatitis.

TABLE 2.

Detection of anti-HEV IgG in the sera of patients with a provisional diagnosis of non-A to non-E hepatitis by EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides of HEV genotype 4a

| Patient | Sexb | Age (yr) | Ratio of sample optical density to cutoff valuec

|

Detection of RNA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O3 | FB5 | E4 | F2-2 | E5 | G | ||||

| 48 | F | 29 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.1 | − |

| 79 | M | 19 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.1 | − |

| 87 | F | 26 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | + (4) |

| 91 | M | 49 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.2 | +/−e |

| 94 | M | 20 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.0 | − |

| 108 | F | 37 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | + (4) |

| 109 | F | 28 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.0 | − |

| 132 | F | 36 | 0.6 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 0.1 | − |

| 170 | M | 52 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 0.0 | + (1) |

| 245 | F | 24 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.8 | − |

| 218 | F | 30 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.0 | + (1) |

| 253 | F | 29 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | + (4) |

| 255 | M | 24 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | + (4) |

Exclusion of hepatitis E was based on a negative result from the Genelabs assay (6).

F, female; M, male.

Sera were considered positive when the ratio of the sample optical density to the cutoff value was equal to or greater than 1.0 (shown in boldface).

The genotypes of RT-PCR positive samples are given in parentheses.

The amplicon was not confirmed by sequencing.

A second serum sample, taken 3 weeks after that for which the result is shown in Table 2, was available from patient 170. This sample was positive by the Genelabs assay (ratio of the sample optical density to the cutoff value, 2.9). The ratio of the sample optical density to the cutoff value from the FB5-based assay had increased to 2.2, but that from the F2-2-based assay had declined to 1.1. Antibodies were no longer detectable by the O3-based assay, and the E4- and E5-based assays remained negative.

Comparison of the Genelabs EIA and the EIAs based on each of the recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4.

Each of the EIAs based on the recombinant polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 was compared to the Genelabs assay. The results of EIAs based on O3, FB5, E4, F2-2, and E5 showed 97.3, 96.0, 92.6, 93.0, and 91.7% concordances with the results of the Genelabs assay, respectively (Table 3). Notably, the EIA based on polypeptide FB5 could detect more cases of HEV infection than the Genelabs EIA, while the assay based on the E5 polypeptide could detect fewer cases.

TABLE 3.

Relationship between results of EIAs based on HEV polypeptides and the Genelabs EIAa

| Polypeptide and assay result | No. of samples with the following Genelabs EIA result:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| O3 | |||

| Positive | 38 | 5 | 43 |

| Negative | 3 | 254 | 257 |

| Total | 41 | 259 | 300 |

| FB5 | |||

| Positive | 40 | 11 | 51 |

| Negative | 1 | 248 | 249 |

| Total | 41 | 259 | 300 |

| E4 | |||

| Positive | 28 | 9 | 37 |

| Negative | 13 | 250 | 263 |

| Total | 41 | 259 | 300 |

| F2-2 | |||

| Positive | 29 | 9 | 38 |

| Negative | 12 | 250 | 262 |

| Total | 41 | 259 | 262 |

| E5 | |||

| Positive | 19 | 3 | 22 |

| Negative | 22 | 256 | 278 |

| Total | 41 | 259 | 300 |

Concordances between the O3-, FB5-, E4-, F2-2-, and E5-based EIA, and the Genelabs EIA were 97.3% (P > 0.05), 96.0% (P < 0.01), 92.6% (P > 0.05), 93.0% (P > 0.05), and 91.7% (P < 0.01), respectively.

Detection of HEV RNA in sera from patients with sporadic cases of acute hepatitis.

The etiology of sporadic acute hepatitis was diagnosed by serological tests for antigens and antibodies, as described above. All 300 serum samples were tested for HEV RNA by RT-PCR. The results showed that 17 of 39 cases of hepatitis E plus 1 of the cases of HBV and HEV coinfection were RNA positive (Table 1). Six of 39 patients provisionally diagnosed with non-A to non-E hepatitis (hepatitis E was excluded on the basis of antibody negativity by the Genelabs assay) were positive for HEV RNA, including 3 of the 10 serum samples from patients with non-A to non-E hepatitis which were reactive in assays based on antigens from HEV genotype 4 (Table 2). Three serum samples (Table 2, patients 218, 253, and 255), which were negative by all five polypeptide-based assays as well as the Genelabs assay, were positive for HEV RNA and may have been taken very early in infection, prior to the development of antibodies. A further sample (from patient 91), which was positive only by the FB5-based assay, appeared to be positive by RT-PCR, but attempts to clone the amplicon were unsuccessful.

HEV genotypes causing sporadic acute hepatitis in China.

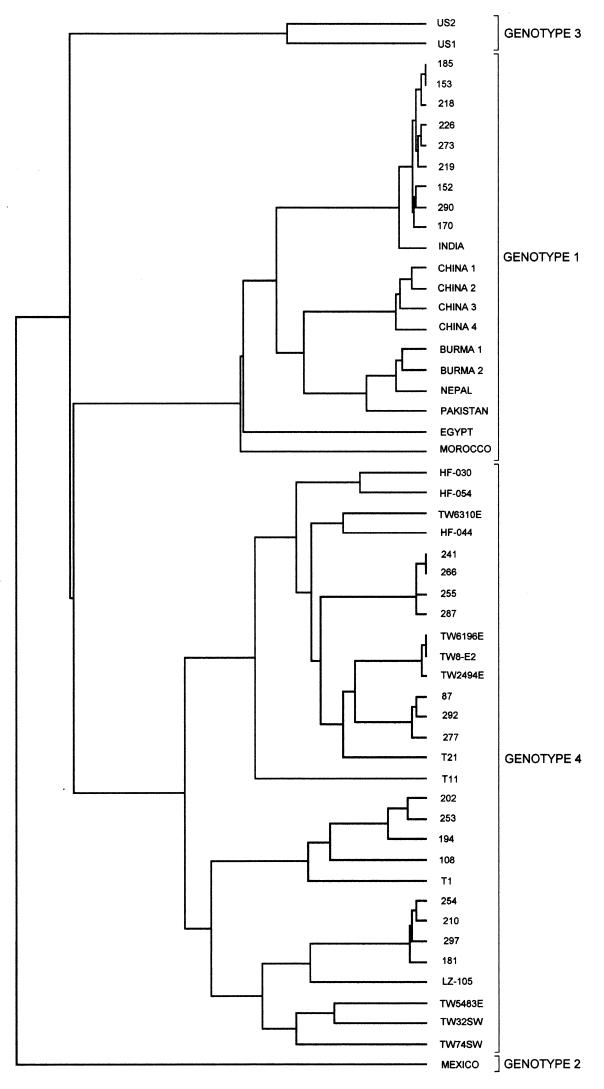

Comparison of individual sequences to the sequences in the GenBank database revealed that of the 18 anti-HEV-positive serum samples which were found to contain virus (Table 1), 7 contained HEV genotype 1 and 11 contained HEV genotype 4. HEV sequences were obtained from six patients originally diagnosed as having non-A to non-E hepatitis (Table 2); two were genotype 1 and four were genotype 4. Figure 3 shows a dendrogram of the 24 sequences with all homologous HEV genotype 4 sequences and a representative selection of genotype 1 sequences from the GenBank nucleotide database.

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram of HEV sequences generated in the present study, produced by using the PileUp program (Genetics Computer Group). All homologous genotype 2, 3, and 4 sequences present in the GenBank nucleotide database are included for comparison, along with a representative selection of genotype 1 sequences. Accession numbers for GenBank sequences are as follows: for genotype 1, India, accession no. x98292; China 1, accession no. l25547; China 2 (Xinjiang), accession no. d11092; China 3, accession no. af141652; China 4, accession no. m94177; Burma 1, accession no. m73218; Burma 2, accession no. d10330; Nepal, accession no. af051830; Pakistan, accession no. af185822; Egypt, accession no. af051352; Morocco, accession no. af065061; for genotype 2, Mexico, m74506; for genotype 3, US1, af060669; US2, af060669; for genotype 4 (all from China or Taiwan), HF-030, accession no. af134916; HF-054, accession no. af134917; TW6310E, accession no. af117279; HF-044, accession no. af134612; TW6196E, accession no. af117278; TW8-E2, accession no. af117275; TW2494E, accession no. af117276; T21, accession no. af151963; T11, accession no. af151962; T1, accession no. aj272108; LZ-105, accession no. af103940; TW5483E, accession no. af117277; TW32SW, accession no. af117280; TW74SW, accession no. af117281.

DISCUSSION

The entire ORF3 product and four overlapping ORF2 polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 were expressed in E. coli as fusion proteins. EIAs based on these purified polypeptides were developed for detection of anti-HEV IgG and compared to a commercial (Genelabs) assay, which is based on polypeptides from HEV genotypes 1 and 2. Of 41 serum samples from patients with acute sporadic hepatitis which were positive for anti-HEV by the Genelabs assay, 40, 38, 29, 28, and 19 serum samples were positive for anti-HEV IgG by EIAs based on recombinant polypeptides FB5, O3, F2-2, E4, and E5 of HEV genotype 4, respectively (Table 1). Only one of these serum samples (from patient 261) was negative for anti-HEV IgG by all five HEV genotype 4 polypeptide-based EIAs. Because this sample was also negative for HEV RNA, a false-positive reaction for anti-HEV antibody in the Genelabs assay cannot be ruled out. We also tested sera from patients with a provisional diagnosis of non-A to non-E hepatitis; 10 of 39 (26%) were positive for anti-HEV IgG on the basis of the results of the EIAs with polypeptides from HEV genotype 4 (Table 2). Of these 10 serum samples, 10, 8, and 7 serum samples were positive for anti-HEV IgG by assays based on polypeptides FB5, F2-2, and E4, respectively.

The concordances between the Genelabs EIA and each of these five assays in detecting anti-HEV antibody were analyzed. The results (Table 3) showed that there were no significant differences between the Genelabs EIA and assays based on polypeptides O3, E4, and F2-2; but the differences were significant between the Genelabs EIA and the FB5 and E5 polypeptide-based assays. The assay based on polypeptide FB5 detected more cases of HEV infection than the Genelabs assay did, while that based on polypeptide E5 detected fewer cases. Polypeptide FB5, from the N-terminal region of ORF2 of HEV genotype 4, showed the greatest immunoreactivity to anti-HEV with both sets of sera, confirming the importance of this region in eliciting an antibody response in the early acute phase of infection (20). The recombinant polypeptides and peptides used in most anti-HEV EIAs are from the C terminus of ORF2 (and from ORF3), but in the present study, polypeptide E5 from the C terminus of ORF2 showed much lower immunoreactivity than polypeptide FB5. The N terminus of the ORF2 product may thus provide epitopes which are highly reactive with sera from patients in the early acute phase, while the C terminus of ORF2 may contain epitopes which are reactive with convalescent-phase sera (20). Antibody status may vary with the stage of disease, and screening of a population with a significant number of individuals in the convalescent phase could give results different from those of the present study in terms of immunoreactivity to each of the five recombinant polypeptides. Ideally, we would wish to monitor individual patients longitudinally throughout the duration of their infection and convalescence, using each of our assays. In addition, we would like to be able to evaluate our assays with sera from patients previously infected with HEV isolates of genotypes other than 1 and 4.

The results of the present study suggest that some patients diagnosed provisionally as having non-A to non-E hepatitis in China may, in fact, have hepatitis E and that a single test for anti-HEV IgG is insufficient for the diagnosis of hepatitis E. Variations in immunoreactivities and a limited window for the persistence of antibodies to various epitopes may account for such diagnostic failures. Anti-HEV IgM and IgA have been detected in the acute phase of hepatitis E and may disappear during the convalescence period, so that diagnosis of hepatitis E may be improved by detecting anti-HEV IgM and IgA antibodies also (6, 8, 9, 12).

All samples were tested for HEV RNA by using degenerate primers that can amplify HEV genotypes 1 to 4 (24). A total of 43% (18 of 41) of serum samples positive for anti-HEV IgG by both the Genelabs and the HEV genotype 4 polypeptide-based assays and 30% (3 of 10) of those positive by the HEV genotype 4 polypeptide-based assay only were positive for HEV RNA (the result for an additional, RT-PCR-positive sample was not confirmed by sequencing; Table 2). The rates of HEV RNA positivity were not significantly different between the two populations. However, it is clear that HEV genotype 4 predominated in both populations. One of three cases detected by the genotype 4 polypeptide-based EIAs, but not the Genelabs assay, proved to be a case of genotype 1 infection (Table 2), indicating that genotype differences are not the sole reason for the failure of the Genelabs assay to detect antibodies. Indeed, the average ratio of the sample optical density to the cutoff value obtained by the Genelabs assay was higher for those sera that were positive for HEV genotype 4 than for those sera that were positive for genotype 1 (Table 1). Three samples negative for antibody by all HEV genotype 4 polypeptide-based assays, as well as the Genelabs assay, were positive for HEV RNA (one sample was positive for genotype 1 and two samples were positive for genotype 4), indicating that some patients with hepatitis E may present prior to the appearance of detectable levels of IgG.

Detection of HEV requires visualization of virus particles in fecal specimens by immunoelectron microscopy (5) or the detection of HEV RNA by RT-PCR. However, immunoelectron microscopy is of insufficient sensitivity and too cumbersome for use for routine analysis. As far as RT-PCR is concerned, the viremia in patients with hepatitis E is typically of limited duration (1), and the RT-PCR assay requires complex technology and is prone to contamination. Neither of these assays, therefore, is ideal for routine use, and the diagnosis of hepatitis E is dependent primarily on the detection of antibodies.

The anti-HEV IgG EIA from Genelabs, which is the commercial assay for HEV most commonly used worldwide, uses polypeptides from the C-terminal ORF3 and ORF2 domains of HEV genotypes 1 and 2. However, thus far, genotype 2 has been reported only in Mexico (15) and Nigeria (7) and has never been isolated in Asia. HEV genotypes 1 and 4 are predominant in China (29), and other genotypes may also be present. The EIA derived from genotypes 1 and 2 proved inadequate for the diagnosis of acute hepatitis in one of the patients infected with the U.S. strain, which was of genotype 3 (27), and commercial immunoassays derived from HEV genotypes 1 and 2 may be of insufficient sensitivity for the reliable detection of other HEV genotypes. Our assays based on HEV genotype 4 polypeptides can detect antibodies in the majority of patients found to be positive for anti-HEV antibody by the Genelabs assay. Furthermore, some patients negative for anti-HEV antibody by the Genelabs assay were positive by assays derived from genotype 4, and the Genelabs assay may miss some cases of acute HEV infection when it is used in China. The antigens used in most anti-HEV immunoassays are recombinant polypeptides and synthetic peptides from the ORF3 product and the C terminus of the ORF2 product, and there is evidence that assays based on recombinant polypeptides may be more reliable than those based on synthetic peptides (22). The immunoreactive epitopes at the C terminus of ORF2 may be conformational peptides, and even recombinant polypeptides may not adopt the correct conformation (18, 20). The N terminus of the ORF2 product may provide epitopes which are highly reactive with sera from patients in the early acute phase of infection, while the C terminus of ORF2 may contain epitopes which are reactive with sera from patients in the convalescent phase. The FB5 polypeptide from the HEV T1 ORF2 product was also shown in the present study to be highly reactive with sera from patients in the early acute phase of infection. It is not clear whether the presence of an additional 12 aa residues at the amino terminus of the genotype 4 gene product (30) may contribute to the antigenic reactivity of the FB5 recombinant protein.

In summary, the sensitivities of immunoassays for antibodies to HEV may be increased by including antigens from different genotypes and from both the N termini and the C termini of ORF2 and ORF3. The incidence of HEV infection in China, as well as in the West, may be underestimated due to a lack of appropriate assays for the detection of all strains of HEV with equal sensitivities, especially in sera from patients in the early acute phase of infection. For China, the way forward may be to develop EIAs based on genotype 1 and 4 antigens, and the FB5 and O3 polypeptides seem good candidates for the latter. The value of assays for IgM and IgA, both for diagnosis in the early acute phase and for differentiation of the acute phase of HEV infection, merits further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zhengyong Li for assistance with the purification of the recombinant polypeptides and Yunlong Wang for assistance with the development of the enzyme immunoassays.

Youchun Wang was the recipient of a Research Development Award in Tropical Medicine from the Wellcome Trust.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aggarwal R, Kini D, Sofat S, Naik S R, Krawczynski K. Duration of viraemia and faecal viral excretion in acute hepatitis E. Lancet. 2000;356:1081–1082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02737-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aye T T, Uchida T, Ma X Z, Iida F, Shikata T, Zhuang H, Win K M. Complete nucleotide sequence of a hepatitis E virus isolated from the Xinjiang epidemic (1986–1988) of China. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3512. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.13.3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi S L, Purdy M A, McCaustland K A, Margolis H S, Bradley D W. The sequence of hepatitis E virus isolated directly from a single source during an outbreak in China. Virus Res. 1993;28:233–247. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(93)90024-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley D W, Krawczynski K, Cook E H, Jr, McCaustland K A, Humphrey C D, Spelbring J E, Myint H, Maynard J E. Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis: serial passage of disease in cynomolgus macaques and tamarins and recovery of disease-associated 27- to 34-nm viruslike particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6277–6281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryan J P, Tsarev S A, Iqbal M, Ticehurst J, Emerson S, Ahmed A, Duncan J, Rafiqui A R, Malik I A, Purcell R H, Legters L J. Epidemic hepatitis E in Pakistan: patterns of serologic response and evidence that antibody to hepatitis E virus protects against disease. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:517–521. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buisson Y, Grandadam M, Nicand E, Cheval P, van Cuyck-Gandre H, Innis B, Rehel P, Coursaget P, Teyssou R, Tsarev S. Identification of a novel hepatitis E virus in Nigeria. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:903–909. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chau K H, Dawson G J, Bile K M, Magnius L O, Sjogren M H, Mushahwar I K. Detection of IgA class antibody to hepatitis E virus in serum samples from patients with hepatitis E virus infection. J Med Virol. 1993;40:334–338. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890400414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clayson E T, Myint K S, Snitbhan R, Vaughn D W, Innis B L, Chan L, Cheung P, Shrestha M P. Viremia, fecal shedding, and IgM and IgG responses in patients with hepatitis E. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:927–933. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.4.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson G J, Chau K H, Cabal C M, Yarbough P O, Reyes G R, Mushahwar I K. Solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for hepatitis E virus IgG and IgM antibodies utilizing recombinant antigens and synthetic peptides. J Virol Methods. 1992;38:175–186. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(92)90180-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erker J C, Desai S M, Schlauder G C, Dawson G J, Mushahwar I K. A hepatitis E virus variant from the United States: molecular characterization and transmission in cynomolgus macaques. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:681–690. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-3-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Favorov M O, Khudyakov Y E, Mast E E, Yashina T L, Shapiro C N, Khudyakova N S, Jue D L, Onischenko G G, Margolis H S, Fields H A. IgM and IgG antibodies to hepatitis E virus (HEV) detected by an enzyme immunoassay based on an HEV-specific artificial recombinant mosaic protein. J Med Virol. 1996;50:50–58. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199609)50:1<50::AID-JMV10>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison T J. Hepatitis E virus—an update. Liver. 1999;19:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.1999.tb00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsieh S Y, Yang P Y, Ho Y P, Chu C M, Liaw Y F. Identification of a novel strain of hepatitis E virus responsible for sporadic acute hepatitis in Taiwan. J Med Virol. 1998;55:300–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199808)55:4<300::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang C C, Nguyen D, Fernandez J, Yun K Y, Fry K E, Bradley D W, Tam A W, Reyes G R. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the Mexico isolate of hepatitis E virus (HEV) Virology. 1992;191:550–558. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90230-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang R T, Nakazono N, Ishii K, Kawamata O, Kawaguchi R, Tsukada Y. II. Existing variations on the gene structure of hepatitis E virus strains from some regions of China. J Med Virol. 1995;47:303–308. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaur M, Hyams K C, Purdy M A, Krawczynski K, Ching W M, Fry K E, Reyes G R, Bradley D W, Carl M. Human linear B-cell epitopes encoded by the hepatitis E virus include determinants in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3855–3858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khudyakov Y E, Favorov M O, Jue D L, Hine T K, Fields H A. Immunodominant antigenic regions in a structural protein of the hepatitis E virus. Virology. 1994;198:390–393. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwo P Y, Schlauder G G, Carpenter H A, Murphy P J, Rosenblatt J E, Dawson G J, Mast E E, Krawczynski K, Balan V. Acute hepatitis E by a new isolate acquired in the United States. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:1133–1136. doi: 10.4065/72.12.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li F, Torresi J, Locarnini S A, Zhuang H, Zhu W F, Guo X X, Anderson D A. Amino-terminal epitopes are exposed when full-length open reading frame 2 of hepatitis E virus is expressed in Escherichia coli, but carboxy-terminal epitopes are masked. J Med Virol. 1997;52:289–300. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199707)52:3<289::aid-jmv10>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T C, Zhang J, Shinzawa H, Ishibashi M, Sata M, Mast E E, Kim K, Miyamura T, Takeda N. Empty virus-like particle-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for antibodies to hepatitis E virus. J Med Virol. 2000;62:327–333. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200011)62:3<327::aid-jmv4>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mast E E, Alter M J, Holland P V. Evaluation of assays for antibody to hepatitis E virus by a serum panel. Hepatology. 1998;27:857–861. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McAtee C P, Zhang Y F, Yarbough P O, Bird T, Fuerst T R. Purification of a soluble hepatitis E open reading frame 2- derived protein with unique antigenic properties. Protein Express Purif. 1996;8:262–270. doi: 10.1006/prep.1996.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng X J, Purcell R H, Halbur P G, Lehman J R, Webb D M, Tsareva T S, Haynes J S, Thacker B J, Emerson S U. A novel virus in swine is closely related to the human hepatitis E virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9860–9865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlauder G G, Desai S M, Zanetti A R, Tassopoulos N C, Mushahwar I K. Novel hepatitis E virus (HEV) isolates from Europe: evidence for additional genotypes of HEV. J Med Virol. 1999;57:243–251. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199903)57:3<243::aid-jmv6>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlauder G G, Frider B, Sookoian S, Castano G C, Mushahwar I K. Identification of 2 novel isolates of hepatitis E virus in Argentina. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:294–297. doi: 10.1086/315651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smalley D L, Hall M F, Broughton C L. Autoantibodies present in chronic hepatitis C and chronic hepatitis B viral infections. Hepatology. 1998;27:1452–1453. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsarev S A, Tsareva T S, Emerson S U, Kapikian A Z, Ticehurst J, London W, Purcell R H. ELISA for antibody to hepatitis E virus (HEV) based on complete open-reading frame-2 protein expressed in insect cells: identification of HEV infection in primates. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:369–378. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y C, Ling R, Erker J C, Zhang H Y, Li H M, Desai S, Mushahwar I K, Harrison T J. A divergent genotype of hepatitis E virus in Chinese patients with acute hepatitis. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:169–177. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y C, Zhang H Y, Ling R, Li H M, Harrison T J. The complete sequence of hepatitis E virus genotype 4 reveals an alternative strategy for translation of open reading frames 2 and 3. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1675–1686. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-7-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J C, Sheen I J, Chiang T Y, Sheng W Y, Wang Y J, Chan C Y, Lee S D. The impact of traveling to endemic areas on the spread of hepatitis E virus infection: epidemiological and molecular analyses. Hepatology. 1998;27:1415–1420. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yarbough P O, Tam A W, Fry K E, Krawczynski K, McCaustland K A, Bradley D W, Reyes G R. Hepatitis E virus: identification of type-common epitopes. J Virol. 1991;65:5790–5797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5790-5797.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin S, Tsarev S A, Purcell R H, Emerson S U. Partial sequence comparison of eight new Chinese strains of hepatitis E virus suggests the genome sequence is relatively stable. J Med Virol. 1993;41:230–241. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890410311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, McAtee P, Yarbough P O, Tam A W, Fuerst T. Expression, characterization, and immunoreactivities of a soluble hepatitis E virus putative capsid protein species expressed in insect cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:423–428. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.423-428.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang H, Cao X Y, Liu C B, Wang G M. Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in China. In: Shikata T, Purcell R H, Uchida T, editors. Viral hepatitis C, D and E. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Exerpta Medica; 1991. pp. 277–285. [Google Scholar]