Abstract

Background:

Heralded as a teaching, assessment and reflective tool, and increasingly as a longitudinal and holistic perspective of the educator’s development, medical educator’s portfolios (MEP)s are increasingly employed to evaluate progress, assess for promotions and career switches, used as a reflective tool and as a means of curating educational activities. However, despite its blossoming role, there is significant dissonance in the content and structure of MEPs. As such, a systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to identify what is known of MEPs and its contents.

Methods:

Krishna’s Systematic Evidenced Based Approach (SEBA) was adopted to structure this SSR in SEBA of MEPs. SEBA’s constructivist approach and relativist lens allow data from a variety of sources to be considered to paint a holistic picture of available information on MEPs.

Results:

From the 12 360 abstracts reviewed, 768 full text articles were evaluated, and 79 articles were included. Concurrent thematic and content analysis revealed similar themes and categories including: (1) Definition and Functions of MEPs, (2) Implementing and Assessing MEPs, (3) Strengths and limitations of MEPs and (4) electronic MEPs.

Discussion:

This SSR in SEBA proffers a novel 5-staged evidence-based approach to constructing MEPs which allows for consistent application and assessment of MEPs. This 5-stage approach pivots on assessing and verifying the achievement of developmental milestones or ‘micro-competencies’ that facilitate micro-credentialling and effective evaluation of a medical educator’s development and entrust-ability. This allows MEPs to be used as a reflective and collaborative tool and a basis for career planning.

Keywords: Medical educator portfolio, teaching portfolio, medical education, teaching, assessment, reflection

Introduction

Portfolios provide a holistic and longitudinal self-portrait of a medical educator’s professional identity formation and career development.1-3 Using self-selected material and reflections, portfolios3-7 differ sharply from logbooks, curriculum vitae, course logs, and training folders as a better means of evaluating a professional holistically and longitudinally.1,3,4,8,9 These self-portraits have even been used by medical educators as a means of illustrating their many roles10-15 for employment and promotion purposes.16-18 Indeed, medical educator portfolios (henceforth MEPs) circumnavigate the limitations posed by conventional assessment methods that often focus upon research grants and publications5-7,15,18-20 and to the detriment of appreciating the quality, breadth, depth19,21, and impact 11 of a medical educator’s role amongst other things a ‘Professional Expert’, ‘Facilitator’, ‘Information Provider’, ‘Enthusiast’, ‘Faculty Developer’, ‘Mentor’, ‘Undergraduate and Postgraduate Trainer’, ‘Curriculum Developer’, ‘Assessor and Assessment Creator’, ‘Influencer’, ‘Scholar’, ‘Innovator’, ‘Leader’ and ‘Researcher’. 13

Increasing use of electronic portfolios 22 have further boosted the visibility of MEPs,2,3,6,14,16-18,23,24 and expanded its use in collaborative work and mentoring, making MEPs a valuable tool to assess medical educators,1,17 and underlining its increasing footprint in the medical education landscape.1,4,25

However, despite its much heralded benefits,2,3,6,14,16-18,23,24 various considerations in MEP’s structure, implementation, and assessments challenge its validity2,7,14,18,21. A systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to study current literature to enhance understanding of MEPs, its roles, its structure, and help to design a consistent framework for MEPs that can be used across settings, purposes, and specialities, given its ability to evaluate data26-30 from ‘various methodological and epistemological traditions’. 31

Methodology

To overcome a lack of structuring and the reflexive nature of SSRs, which raises questions to their reproducibility and transparency, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidenced Based Approach (henceforth SEBA)32-35 to guide the SSR (henceforth SSR in SEBA) of MEPs. SSRs in SEBA proffer accountable, transparent and reproducible reviews.

To enhance accountability and transparency, SSRs in SEBA employ an expert team to guide, oversee, and support all stages of SEBA. The expert team is composed of composed of medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), and local educational experts and clinicians at NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School. The expert team were involved in all stages of the SSR in SEBA.

SSRs in SEBA are built on a constructivist perspective. It acknowledges the personalised, reflective and experiential aspect of development as a medical educator, as well as medical education as a sociocultural construct influenced by prevailing clinical, academic, personal, research, professional, ethical, psychosocial, emotional, legal, and educational factors.36-40 This enables them to map data on a specific topic from multiple angles and consider the factors influencing the adoption of MEPs.

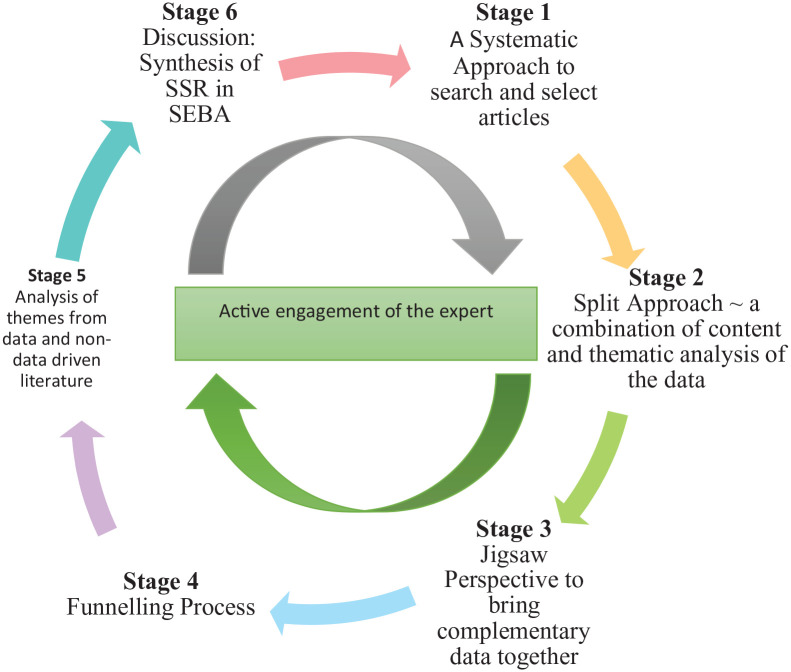

To operationalise a SSR in SEBA, the research team adopted the principles of interpretivist analysis, to enhance reflexivity and discussions30,41-43 in the Systematic Approach, Split Approach,44-47 Jigsaw Perspective, Funnelling Process, analysis of data from grey and black literature, and Synthesis of SSR in SEBA which make up SEBA’s 6 stages outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The SEBA process.

Stage 1 of SEBA: Systematic approach

Determining the title and background of the review

The expert and research team worked together to determine the overall goals of the SSR and the population, context, and concept to be evaluated. With increasing focus on the evaluation of educational activities amongst clinical faculties, 48 it was deemed reasonable for MEPs to focus exclusively on educational activity and be distinct from a clinical portfolio, given prevailing suggestions that clinical accomplishments and development tend to cloud educational achievements. 1

Identifying the research question

Guided by the Population, Concept, and Context (PCC), the teams agreed upon the research questions. The primary research question was ‘what is known about medical educator portfolios?’. The secondary questions were ‘what are its components?’, ‘how are MEPs implemented?’ and ‘what are the strengths and weaknesses of current MEPs?’.

Inclusion criteria

All grey literature, peer reviewed articles, narrative reviews, systematic, scoping, and systematic scoping reviews published from 1st January 2000 to 31st December 2019 were included in the PCC and a PICOS format was adopted to guide the research processes49,50 (See Supplemental File 1).

Searching

A search on 6 bibliographic databases (PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, Google Scholar and Scopus) was carried out between 17th of November 2019 to 24th of April 2020 for articles published between the years 2000 to 2019. Limiting the inclusion criteria to these dates was in keeping with Pham et al (2014)’s 51 approach of ensuring a viable and sustainable research process. The search process adopted was structured along the processes set out by systematic scoping reviews. Additional articles were identified through snowballing.

The PubMed Search Strategy may be found in Supplemental File 2.

Extracting and charting

Using the abstract screening tool, members of the research team independently reviewed the titles and abstracts and created independent lists of titles to be reviewed. These lists were discussed online, and Sambunjak, Straus, Marusic’s 52 approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be scrutinised.

The 6 members of the research team independently reviewed all articles on the final list, discussed them online, and adopted Sambunjak, Straus, Marusic’s 52 approach to ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be included.

Stage 2 of SEBA: Split approach

Three teams of researchers simultaneously and independently reviewed the 79 included full-text articles. The first team of 3 researchers independently summarised and tabulated the included full-text articles in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong, Greenhalgh, Westhorp, Buckingham, Pawson’s 53 RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews and Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai, Rodgers, Britten, Roen, Duffy’s 54 ‘Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews’. These individual efforts were compared and discussed by the 3 researchers and consensus was achieved on the final content and structure of the tabulated summaries. The tabulated summaries served to ensure that key aspects of included articles were not lost.

Concurrently, the second team of 3 researchers independently analysed the included articles using Braun, Clarke’s 55 approach to thematic analysis. 56 In phase 1 of Braun and Clarke’s approach, the research team carried out independent reviews, ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data.57-61 In phase 2, ‘codes’ were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning and collated into a code book to code and analyse the rest of the articles using an iterative step-by-step process. As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts. In phase 3, the categories were organised into themes that best depict the data. An inductive approach allowed themes to be ‘defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification’ . 60 In phase 4, the themes were refined to best represent the whole data set and discussed. In phase 5, the research team discussed the results of their independent analysis online and at reviewer meetings. ‘Negotiated consensual validation’ was used to determine a final list of themes approach and ensure the final themes. 52

A third team of 3 researchers independently analysed the included articles using Hsieh, Shannon’s 62 approach to directed content analysis. Analysis using the directed content analysis approach involved ‘identifying and operationalising a priori coding categories’.62-67 The first stage saw the research team draw categories from Baldwin, Chandran, Gusic’s 68 article entitled ‘Guidelines for evaluating the educational performance of medical school faculty: priming a national conversation’ to guide the coding of the articles. Any data not captured by these codes were assigned a new code. In keeping with deductive category application, coding categories were reviewed and revised as required.

In the third stage, the research team discussed their findings online and used ‘negotiated consensual validation’ to achieve consensus on the categories delineated and the codes within them. The final codes were compared and discussed with the final author, who checked the primary data sources to ensure that the codes made sense and were consistently employed. Any differences in coding were resolved between the research team and the final author. ‘Negotiated consensual validation’ was used as a means of peer debrief in all 3 teams to further enhance the validity of the findings. 69

Results

A total of 12 360 abstracts were reviewed, 768 full text articles were evaluated, and 79 articles were included (see Supplemental File 3). The themes identified using Braun, Clarke’s 55 approach to thematic analysis and categories identified through use of Hsieh, Shannon’s 62 approach to directed content analysis were similar and included (1) Definition and functions of MEPs, (2) Developing and implementing MEPs, (3) Assessing MEPs, (4) Strengths and limitations of MEPs and Electronic MEPs (E-MEP)s. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Themes/categories by jigsaw perspective.

| S/N | Themes/Categories by Jigsaw Perspective | Sub-themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definition and Functions of MEPs | Definition |

| Functions of MEPs | ||

| 2 | Developing and implementing MEPs | Designing MEPs |

| Components of MEPs | ||

| Implementation of MEPs | ||

| 3 | Assessing MEPs | Formative and/or summative assessment of MEPs |

| MEPs may contain quantitative and/or qualitative information. | ||

| Setting standards/rubrics for assessment | ||

| Assessors of portfolio | ||

| 4 | Strengths and Limitations of MEPs and Electronic MEPs (E-MEP)s | Strengths of MEPs |

| Strengths of E-MEPs | ||

| Limitations of MEPs | ||

| Limitations of E-MEPs |

Stage 3 of SEBA: Jigsaw perspective

The Jigsaw Perspective sees the themes identified using Braun, Clarke’s 55 approach to thematic analysis and categories identified through use of Hsieh, Shannon’s 62 approach to directed content analysis reviewed by the research and expert teams as part of SEBA’s reiterative process. These discussions determined that there were significant overlaps and similarities between the themes and categories allowing them to be considered and presented in tandem.

Theme/Category 1: Definition and functions of MEPs

Definition of MEPs

MEPs are defined as a collection of documents spanning a period of time4,5,7,14,17,20,70,71 seeking to demonstrate developing competencies,1-4,8,17-20,72 desirable character traits, 8 learning,4,8 challenges and improvements made3,8,14 in the field of medical education. Curated by the individual, these documents reflect the medical educator’s perspective of their development1-4,8,17-20,72 and contains elements of feedback 73 and reflection on good and bad experiences.1-4,8

Functions of MEPs

MEPs are used by medical educators to highlight professional development, documentation, learning activities, educational undertakings, reflections and career planning, while institutions employ MEPs for assessment purposes.

MEPs serve several functions and are used by medical educators and institutions differently. First, medical educators use MEPs to highlight professional development. They record their appraisals,1,2,4,18,23 revalidations,1,3,4,23 accreditations,3,23,70,73 and promotions1,2,4,5,14,15,17-20,68,70,73,74 in an MEP, and this can also be used for applying for specific roles within educational settings.1,6,18 Second, they serve as a form of documentation, where medical educators document their competencies1-4,8,14,17-19,75 certification of standards of professional performance3,4, illustrate accomplishments and educational activities,1-4,7,17,18,25,70,71,76 demonstrate desirable character traits,1,8 highlight leadership roles and successes,1,8,17,19,68 and showcase teamwork. 8 Third, medical educators use MEPs as a learning tool to guide professional and personal improvements. They highlight experiences8,24,76,77 and reflections,4,6,14,70,74 capture feedback from learners, peers, mentors and supervisors, 4 set learning objectives and guide work towards the achievement of learning objectives,4,78 and help to plan future lessons based on past experiences.4,8

On the other hand, institutions employ MEPs for assessment purposes. It serves as an assessment tool to facilitate hiring and promotion of medical educators by selection committee,2,4-6,14,18,21,23,68 and to evaluate medical educator’s performance and impact.2,6,18,68 Furthermore, MEPs help with the review of program accreditation. 79

Theme/Category 2: Developing and implementing MEPs

Designing MEPs

MEPs attempt to capture longitudinal development. Design of prevailing MEPs occur in a stepwise fashion beginning with an understanding of prevailing use of portfolio16-18,73,76 and the guiding principles behind these design structures,16-18,73,74,76 and its benefits and limitations.8,70 To contextualise MEPs to the particular setting, speciality, and the desired role,3,4,8 designers often consult intended users 77 and experts.68,73,76

The dominant guiding principle for the design of the prototype is the need to balance structure1,3,4,7,77 and flexibility.8,25,73 Structure takes the form of including ‘critical’ domains to be curated 1 and a consistent format is employed to ensure that practical 23 and local institutional needs,17,74 as well as minimum standards of MEPs are met. 77 Flexibility8,25,73 revolves around the contents of the MEP where aspects are sought to effectively capture inventiveness and learning 73 and documentation and reflections.3,4 The prototype 4 is then piloted and review from experts68,73,76 and feedback2,3 sought from a small group further refines its components 77 . The feedback and lessons learnt may be used to educate future users. 3

Components of MEPs

A variety of domains are listed within current MEPs. These domains reflect the setting and the goals of the MEP. How these domains are selected and structured are often not described nor discussed and are thus curated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Components of MEP.

| Sub-themes | Elaboration and/or examples |

|---|---|

| General | Cover page2,71,80,81

List of Contents2,71,79,80,82-84 Identification72,83,85-90 Personal particulars and contact details72,83,85-90 Present rank and organisation affiliation83,86-92 Present role71,93-97 Personal statement2,6,17,79,81,89,93,98,99 Teaching philosophy1,3,5,6,14,17,20,22,71,72,75,81,86-88,90,94-115 What the educator considers essential constituents and attributes for successful teaching and learning1,6,71,75,87,94-98,100,101,104-106,115,116, experiences that shaped teaching style6,75,86,87,96,101,104,105,109,115,116, motivation in teaching1,75,100,104,112. beliefs and principles71,86,87,100,104,112 reflections on strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and growth in teaching over time81,105,106,109,115,116 enthusiasm in teaching 98 comparing own teaching approach with other/newer approaches 1 Goals1,2,5,7,14,20,75-77,79,84,86-88,93-95,97,99-103,105-108,110-113,115 short- and long-term goals2,6,110 may be recorded and ought to be regularly re-evaluated1,2,75,105 should consider areas of interest in medical education, future duties to be undertaken, potential obstacles for progression1,20,89,94,101,105 Should be specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time bound (SMART)1,75,108 outline of duties and roles2,85,91,97,103,113,114,117 Listing of key contributions to medical education and major educational activities81,85,95,98,108,109,117,118 |

| Teaching and scholarship | Documentation of teaching evidence illustrating topics taught1-3,5,6,14,15,18-21,25,71,72,76-83,85-96,98-112,114,115,117-126

Individual exemplars of techniques, approaches and outcomes7,78 Or general materials used in lectures, tutorials, workshops or courses1,2,6,15,19,20,71,86,92,94,107,110,121,124 Or online multimedia5,18,20,71,92,94,107,124 Teaching pedagogy and modalities19,69,79,81-83,85,90,99,103,105,110,112,114,116,122,124. This should highlight alignment with learning objectives and learner needs7,69,116 should consider the characteristics of the learner population 5 should have an interactive element 69 Use of creative and realistic teaching pedagogy7,100,107,112,116,124 Adoption of best practice when developing teaching content7,69,80,85,98,108,117 Evidence of use of the individual’s teaching pedagogy by fellow educators81,100,124 Learner numbers and profile2,6,15,19,20,72,75,79-83,85-91,95,96,99,101,103,105-108,112,117,119-122,124-126 Balance between quantity of learners and quality of teaching impact on learner69,75,83 Teaching location and hours15,20,69,75,80-83,85-92,95,96,99,100,103,105-108,112,117-119,121,122,124-126 Includes number of hours spent devising the activity as well as its actual execution69,105 Teaching impact7,14,69,81,85,88,90,98,108,109 Invitations to teach95,98,100,107,118,125 Multi-source feedback and ratings1,2,6,8,15-17,20,69,73,75,85,86,89,91,92,94-96,98,100,101,106,107,109,110,120,124 Learner grades and feedback5,7,15,20,69,71,72,74,75,79,81,83,84,86,89,92,94-96,98-100,105-110,112,117,118,121,122,124-126 Based on standardised assessments 2 Comparing pre and post teaching2,69 Mentor or supervisor feedback20,75,107,109,112 Peer feedback2,6,15,71,75,77,79,83,85,92,95,96,98,99,107,109,110,112,118,124-126 Self-evaluation1,2,71,75,98,106,110 Comparing one’s performance with the standard 1 Reflective entries1,2,8,24,69,73,76,79-81,85,90,105,108,116,118 Context, analysis and response (2, 57) Reflect on defining teaching experiences8,76 Reflect on insufficiencies, what was learnt and how to improve teaching8,24,80,85,116,118 Reflect on how to utilising feedback and outcomes to better teaching7,69,80,118 Aids goal setting 74 |

| Mentorship and advising5,14,15,19,22,69,71,72,75,80-83,85-91,93-96,98-103,105,106,108,110-112,116-125 | Mentoring duties80,82,83,85-91,93,96,100,103,108,117,118,121,124

List and profiles of mentees69,72,75,80,82,83,86-91,93,94,96,98-101,103,105,108,110,118-122,124 Mentoring goals and pedagogies85,88,108,117 Mentee’s awards and scholarly products69,75,80,83,85-87,89-91,93,94,96,98-100,103,105,108,110,117,118,122,124 Reflective entries85,98,103,108,112,117 |

| Educational research products | Publications details1,6,7,15,20-22,69,71-73,75,82-84,86,87,89,91,94-101,103-110,112,117,118,122,124,126

Presentations and invited conferences7,15,18,20,21,69,71,73,75,82-84,86,87,89-91,95-97,99,100,103-105,107-110,112,117,118,124 Details of delivery method and impact7,69,82,83,87,89,91,96,105,108,117 Books and Chapters2,18,20,69,71,86,91,96,99,106,107,124,126 Details of role, impact, and methodology69,96 Research projects2,3,5,18,71,72,82,96,98 Details of role and impact 96 Development of educational tools and/or modules15,20,69,71,75,88,104,105,108,121,125 Details of effect on other institutions/curriculums7,20,69,75,88,100,108,118 |

| Use of modern technology

71

Research or project or educational grants5,15,20,69,71,72,75,82,83,88,90,91,94,96,97,99,100,103,105,117,122,124 Details of grant value and impact on program development15,69,82,90,94,96,105 Role in grant (Principal or Co-Investigator)69,82,90,94,96,105 |

|

| Leadership and Administration | Leadership roles5,14,15,21,69,71,72,75,80-83,85-91,93-106,108-112,116-120,122-125

Details of duties, position and impact15,69,80,82,83,85-91,93,96,98,99,101,103,105,106,108,116-118,120,122 Directs curriculum through establishing challenging targets, proper distribution of resources and assessing standard of teaching and learning69,106,108,117,118 Reflective entries85,90,108,117,118 Administrative roles3,15,69,71,72,75,80,82,83,86,87,90-107,110,111,120,122-126 Organising courses69,97,107 or assisting in curriculum development69,96,97,99,107 Member of institution committees20,69,71,83,86,90,93,94,96,97,99,101,103,105,106,110,117,122,124 Part of student-faculty associations20,71 |

| Curriculum development | Curriculum development1,5,6,15,20,21,69,71,75,79,80,82,83,85,86,89-91,93-106,108-110,112,116-119,121-126

Role and contribution to curriculum development69,80,82,83,85,96,97,100,101,104-106,108,112,117,118,121,122,124 Brief description of curriculums created including its implementation process and learner profile69,80,82,83,85,86,89-91,94,96-98,100,101,103-106,108,110,116-118,121,122,124 Evidence of needs analysis of students89,90,98,106,108 Assessment of curriculum86,89,90,94,96-99,101,103,105,108,116,117,124 Adoption of curriculum by other institutes 122 Reflective entries85,98,105,108,117 |

| Assessment of learners | Learner assessment1,15,19,69,75,80,85,89-91,94,95,99,101-103,105,108-110,117,118,121,122,125

Role in assessment of learners101,103,108 Details of number of learners assessed and its importance of evaluation to the program15,69,75,80,85,90,101,103,105,108,117,118 Creating new assessment modalities69,75,80,89-91,107,110,117,121 Adoption of best practice117,127 Use of assessment tools to evaluate learners’ knowledge, skills, behaviours, and actions69,90,101,103 Special attention paid to reliability and validity of assessment modality 94 Reflective entries80,103,108,117,118 |

| Formal recognition | Teaching awards1,2,5-7,17,20,69,71,72,75,81,82,85,86,89,91-101,103,104,106-108,110-112,115,117,118,120-122,124,125

Description of selection criteria for94,96,106,110,120,124 Reference letters or letters of appreciation/support2,6,7,71,75,81,92,96,98,100,103,110,120,124,126 |

| Professional development (training and certification) | Attendance at medical education conferences, meetings, courses, seminars, workshops, or modules1,2,6,18,71,73,82-84,86,89,92,94-97,99,100,103,106,107,109,111,112,115,117,122,124

Post-graduate degrees, programs or CME activities in medical education1,3,71,82-84,92,94-97,103,106,109,111,112,117,121,122 |

Implementation of MEPs

There are similarly poorly described steps in implementing current MEPs. Implementation of MEPs can be grouped under 4 themes – user training, assessor training, support and integration into existing practice. With user training, teaching sessions should be carried out prior to implementation of portfolio practice.8,23 This includes highlighting the purpose and benefits when introducing portfolios which may increase portfolio uptake, and providing samples, templates, flowcharts and assessment criteria to medical educators for better clarity on how to create and use portfolios.7,8,17,68,73 Trainers in these sessions should stress the documentation of activities before details are forgotten, 1 highlight the use of portfolios as an active learning tool which allows for self-directed learning, the sharing of teaching philosophy and goals, introduce how one may interact with peers via dissemination of work,17,77 and explain how one should be discerning in the selection of evidence to include for reflection. 2 Second, assessor training can enhance reliability as an assessment tool, 4 help the institute’s promotion committee identify essential components of quality performance and train assessors to work with one another to evaluate and interpret a portfolio. 73 Third, support should be provided through telephone calls or in person. Mentors, facilitators and tutors may facilitate reflection 2 and help review the portfolio or go through portfolio assessment criteria before evaluation.6,73,76 Additionally, administrative support such as an information technology team are essential for successful implementation of MEPs to troubleshoot user problems. 23 Lastly, integration into practice may be done in a longitudinal manner where users have to fill in the portfolio over time, and portfolios may be standalone or an adjunct to existing documentation methods like a curriculum vitae,16,76 and may also be part of summative assessments. 73

Theme/Category 3: Assessing MEPs

Table 3 summarises the key subthemes associated with assessments of MEPs including its use as a formative and summative tool, the type of evidence required for assessment, the development of assessment rubrics, and the assessors.

Table 3.

Assessment of MEP.

| Sub-themes | Elaboration and/or Examples |

|---|---|

| Formative and/or summative assessment of MEPs | Formative assessment8,16,74

Usually involve quality improvement 16 Inclusion and analysis of feedback 74 Summative assessment3,8,16,74 Provides a transparent assessment 8 Ensures negative elements are also included8,74 Emphasises the learning process within professional development 74 |

| MEPs may contain quantitative and/or qualitative information. | Qualitative entries Aided by use of validated tools and frameworks16,19 Used to evaluate goals, personal statement and philosophy and the outcomes of their application 17 Quantitative entries (student results, awards, teaching hours etc.)17,19 Allows the same assessment rubric to be used to ensure fairness and reproducibility 19 Easily analysed 69 Assess both qualitative and quantitative items15,19,20,69,72,75 |

| Setting standards/rubrics for assessment | Benefits of establishing standards and rubrics for assessment Allow for academic recognition across institutions19,21 Ensure sufficient rigour to provide a platform for continuous development 19 Ensures educators meet the standard of practice7,19 Empowers use of a summative portfolio in high-stake evaluations 69 Easily utilised to determine fitness for promotion by committee members 19 |

| This may be achieved by developing a novel scoring criteria

4

or using existing standards or analysis tools7,16

Providing details regarding how each criterion is rated 19 Addressing reliability issues by ensuring a fair and standardised assessment 4 Encourages transparency and objectivity 74 Can be utilised by different institutions 19 Need for review and revision of assessment criteria Assessment rubric may be reviewed by educational experts to improve reliability 19 Revision/updating of assessment rubrics after feedback and discussion by users19,74 Assessment should be tailored to each institution Rating system should be contextual and relevant to institutional needs 69 Weightage of each component varies according to needs 19 Agreed upon by own team of expert educators 19 |

|

| Assessors of portfolio | Institute69,73,74

Use of a team of assessors to ensure comprehensive assessment 74 Can be coaches/mentors74,77 Longitudinal engagement improves validity of assessment 77 Peer1,2,6,73 Self 74 Needs to be trained 19 Assessors need to be clear regarding rating system 19 |

Theme/Category 4: Strengths and limitations of MEPs and E-MEPs

Table 4 showcases the strengths and limitations of MEPs and electronic-MEPs.

Table 4.

Strengths and limitations of MEPs and E-MEPs.

| Strengths of MEPs | |

|---|---|

| Sub-themes | Elaboration and/or examples |

| Impact on medical educators | Motivates life-long self-learning1-4,6,8,14,18,20,24,71,75,77,78

Through repeating phases of reflection, preparation and execution of learning goals1-3,5,8,24,77 Flexibility in managing and selection of content in one’s own portfolio8,78 Identification of areas for improvement1,3,8,14,24,77,79 Developing self-awareness through reflection2,3,14,79 Facilitates the planning of activities to undertake in the future1,14,79 Strengthens good learning attributes3,77 Fosters self-confidence1,24 Develops an inquisitive mind 1 Promotes problem-solving skills 71 Promotes courage and stepping out of comfort zones 1 Encourages teamwork 75 Acquisition of competency3,24,77 Portfolios motivates educator to reach targeted objectives 2 Expertise improvement 1 Facilitates career advancements1,3,71,75,77 Fosters student-tutor relationships 25 Ease of organising documents for regular assessments as documents are already gathered 6 |

| Impact on teaching | Improves quality of teaching1-3,20,75,77

By preparing teachings based on previous experiences2,79 By reflecting and being flexible during teachings2,20 Through multisource feedback from peers and learners regarding teaching practices2,6,75,77 Through collaboration with peers by sharing different perspectives, experiences and thoughts77,79 |

| Impact on patient | Feedback improves patient care1,3 and patient safety 76 |

| Impact on institute | Efficient assessment 71 |

| Features of portfolio | Offers both qualitative and quantitative evidence16,19,20,69,75

Stimulates reflection1-4,8,24,75 Occurs throughout the process from the inclusion of meaningful evidence to the recognition of strengths and insufficiencies 8 Evaluates teaching practices, goals and philosophy 8 More comprehensive than other forms of documentation1,6,18,19,21,69,77,80 More accurate assessment of competence than curriculum vitae and/or letters of recommendation and/or standardised tests1,18,19,21,69,80 Better at illustrating an educator’s teaching techniques, efficacy, objectives and philosophy1,19 Allows evaluation of less successful activities 2 |

| Strengths of E-MEPs | |

| User perspective | Diversity of evidence such as Audio-visual recordings1,3,4,71, Graphics 3 , Web projects 3 , and Digital media1,3,22,71 may be included into MEPs Ease of accessibility, maintenance, and function1-3,7,22,71 Increases reflection8,9 Enhanced portability1,2,4 and instant access 9 Easy to update22,25, retrieve peers’ work and provide feedback9,71 Readily backed-up1,6 More presentable as compared to paper-based portfolios 6 Fosters collaboration and sharing of portfolio1,4,7,25 Provides privacy and security3,25,71 Greater learning drive2,22 More user-friendly2,25,71 |

| Faculty perspective | Assessors and/or mentors can easily access user’s portfolio7,9,22

Allows administrators to evaluate portfolios regularly 9 |

| Limitations of MEPs and E-MEPs | |

| Sub-themes | Elaboration and/or Examples |

| User perspective |

MEPs:

Time and effort required2,8,23,25,77,79 User stress when deciding what content to include 16 Lack of user motivation8,74 Lack of user control over portfolio components 2 and variability in rigidity or flexibility 2 Assessment orientated E-MEPs: Lack of technologic skill required to navigate online platform Unacquainted3,8,9 Lack of technical support3,8 Unable to find the time to learn how to use3,8 Security Hacking3,8 |

| Faculty perspective |

MEPs:

Time and effort required8,20 Cost to assess 23 Unnecessary 18 Inadequate as a stand-alone measure of performance 18 Presence of other documentation modalities already in use 18 Lack of reliability2,19 subjectivity is a concern due to variability of portfolio content7,19,20 Issues with plagiarism 8 E-MEPs: Resources Lack of availability of computers in workplace 9 Increase expenditure to provide technological support and training9,25 With high expectations for a visually pleasing and functionally impeccable design, creating an e-portfolio for medical educators can be challenging 8 |

Stage 4 of SEBA: Funnelling

Reviewing the themes/categories identified through the Jigsaw Process and comparing them with the tabulated summaries highlighted in Supplemental File 4 allows verification of the themes/categories and ensure that there is no additional data to be included. The themes/categories are then reviewed again by the expert team to determine if they may be funnelled into larger themes/categories that will form the basis of the discussion.

Stage 5 of SEBA: Analysis of peer-reviewed and non-data driven literature

Evidenced based data from bibliographic databases (henceforth evidence-based publications) were separated from grey literature and opinion, perspectives, editorial, letters and non-data-based articles drawn from bibliographic databases (henceforth non-data driven) and thematically analysed to determine if non-data driven accounts had influenced the final synthesis of the discussions and conclusions.

The key themes identified from the peer-reviewed evidence-based publications and non-data driven publications were identical and included:

Definition and functions of MEPs

Developing and implementing MEPs

Assessing MEPs

Strengths and limitations of MEPs and E-MEPs

There was consensus that themes from non-data driven and the peer-reviewed evidence-based publications were similar and did not bias the analysis untowardly.

Discussion

The narrative produced from consolidating the themes/categories/tabulated summaries was guided by the Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide and the STORIES (Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis) statement.

Stage 6: Synthesis of the SSR in SEBA

In answering its primary and secondary research questions, this SSR in SEBA provides a number of key insights into the creation and employ of MEPs. To begin MEPs chronicles the professional, personal, research, academic, education and learning journey and development of a medical educator through self-selected data points, descriptions and reflections. Medical educators see MEPs as a means of advancing their careers, capturing their experiences and reflections and as a learning tool, whilst for institutions, MEPs provide a wider perspective of the medical educator and an additional source of data to evaluate an education program.

With evidence that they motivate lifelong learning, self-improvements, promote the acquisition of competency and career advancement, and benefit learners by improving quality of teaching, patient safety and care and program efficacy, MEPs are gradually gaining traction amongst medical educators and institutions. These developments underline the need better structure MEPs to facilitate its wider use.

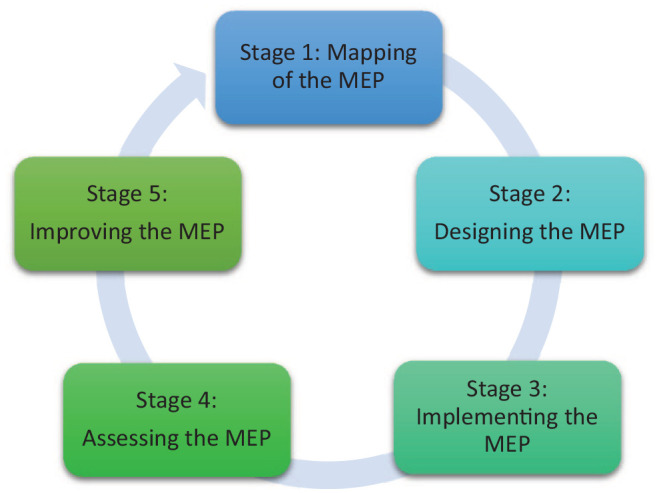

Here we proffer a 5-staged evidence-based approach to the construction and deployment of a MEP as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Five stages of construction and deployment of MEP.

Stage 1: Mapping of the MEP

To begin with, a needs assessment should be carried out by the educational institute to determine, the need, goals,17,74 support and practical issues9,25 associated with implementing such a process. Party to this process must be an acceptable, transparent16,19,20,68,74 and verifiable1,6,18,19,21,68,77,80 means of evaluating the diverse contents of MEPs for accreditation and promotion.16-18 This takes the form of a purpose designed MEP.

Stage 2: Designing the MEP

To maximise its impact, a MEP must include longitudinal quantitative and qualitative evidence15,19,20,68,71,74,75 that is accompanied by clear documentation, reflections and be supplemented the medical educators’ many educational roles,12,81-83 competencies,84-87 characteristics, expectations5,15,20,21,80 and attainment of specific professional standards such as those set out by the Academy of Medical Educators (AoME)84,88-92 and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).91,93-96 Guiding this design are several considerations.

One, the competency based assessments of progression set out by the Academy of Medical Educators 84 helps ensure that key elements of this assessment process is contained within the MEP. These competency based assessments of progression 84 also align a medical educator’s learning objectives to the relevant competency guidelines, local context7,68 and an institution’s promotion criteria,5,74 making the MEP more applicable across settings95,97 and outcomes.95,97

Two, the need for a flexible framework that facilitates balance between flexibility to infuse personal data and the requisite for consistency to ensure that critical data is included. Only when a balance of structure and flexibility is obtained can the portfolio be an accurate depiction of the beliefs, attitudes, behaviours, and professional identity of the medical educator. 3

Three, there must be adequate education of medical educators to ensure that they remain motivated to maintain this ‘living’ document and update it with their goals and plans for future career development. This will also foster effective use of the MEPs as a means of regular self-assessment, continuous education and reflection3,95 which will boost professional development. 3

Four, for ease of review, access and personalisation, electronic MEPs ought to be employed. Electronic MEPs also allow application and storage of diverse evidence such as digital media and recordings and provide a convenient means of collaboration with peers and mentors.1,4,7,9,25,98 However, it is crucial to keep an electronic MEP user-friendly2,25,98 and well supported, 9 to aid its adoption. 99

Five, the combination of this template and use of an electronic platform facilitates adaption to local requirements 68 and enable medical educators to personalise the MEP to their own needs, focuses, phases of their career 73 and learning style. 3

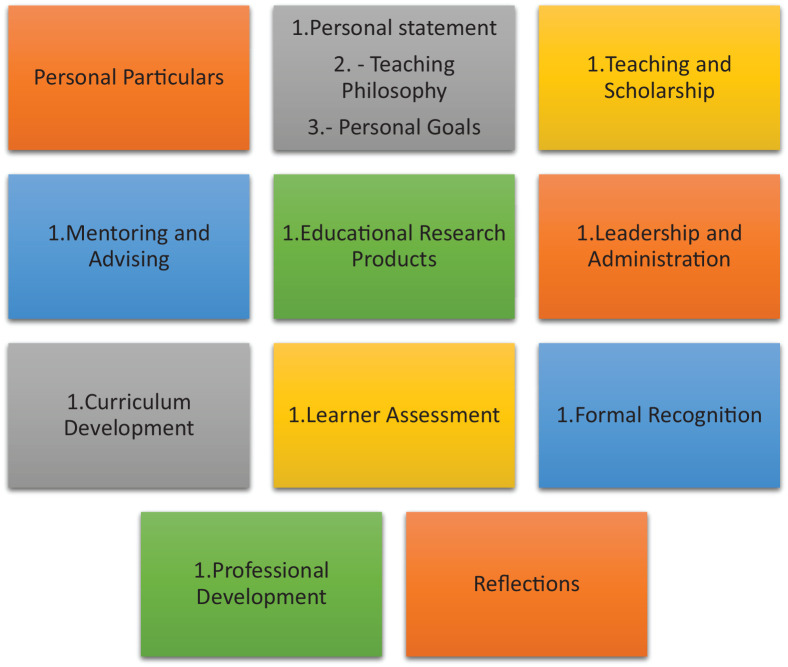

Based on these 5 considerations, we suggest that MEPs document these themes seen in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3.

What should be documented in MEPs.

See also Supplemental File 5 for a MEP template based on these themes.

(Sections 3-10 should contain exemplars, innovations, evidence of progress/maturation of practice, evaluations, feedback and reflections and analysis of events, both positive and negative experiences)100,101

Stage 3: Implementing the MEP

Implementation of MEPs must be accompanied by the training of all users, assessors, and faculty as to the role, need, value and use of MEPs as well as how it is assessed.70,102-105 Exemplars7,8 and scoring rubrics, 19 can guide new users14,16 and ensure fair assessments and improve reliability.4,106 To provide support and guidance for users, assessors and faculty,99,102,104,107,108 coaches, supervisors, and increasingly mentors 1 should be made available to follow the learner’s progress. 99 In turn these coaches, supervisors, and mentors must be provided with protected time 109 and administrative support to help design, update and troubleshoot issues. 105

Stage 4: Assessing the MEP

Pre-empting issues with assessing the various domains and diverse designs through use of qualitative, quantitative, and or mixed methods in the absence of a general standardised assessment rubric, 7 local institutions could promote a homogenous portfolio structure which would aid in the creation of an assessment rubric 19 and clear assessment criteria. 110 Such a rubric may be drawn from Glassick’s criteria of educational excellence,111-114 Miller’s pyramid, 115 the GNOME model of curriculum design,116-118 Kirkpatrick’s Model119,120 and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Toolbox.121,122 These tools will help overcome concerns about the lack of transparency and consistency in prevailing assessments of MEPs.16,73,110,123-126

Stage 5: Updating and improving the MEP

As ‘living documents’ capturing the evolving self-concepts and professional and personal identities of medical educators’ and their changing goals, experiences, and MEPs need to be adapted, pared, and reviewed. Here the data suggests the presence of ‘micro-competencies’. ‘Micro-competencies’ are effectively milestones that are formally assessed and verified using multisource assessments contained within the portfolio. ‘Micro-competencies’ are evident in the developing medical educator’s entries within the portfolio. These entries replete with learning objectives, reports of training approaches and assessments used, the feedback garnered from these sessions, evidence of the longer-term impact upon the learners, the medical educator’s own reflections and plans for refinement provide evidence and verification to development.

‘Micro-competencies’ suggest that a medical educator’s skills, knowledge, and attitudes develop in stepwise competency-based stages from early medical training and continue till all the micro-competencies and competencies are met. These micro-competencies and competencies are then honed and refined by master medical educators. We see the use of these verified achievements of milestones as a natural progression of the concept of milestones within the context of MEPs. ‘Micro-competencies’ guide the medical educator’s development and inform appraisals of their progress, coping, conduct and development. Critically rather than merely standardized points to be met along the trajectory towards achieving a competency, micro-competencies within the MEPs allow a number of refinements to the traditional concept of milestones.

One, micro-competencies are variable and determined with due consideration of the medical educator’s abilities, skills, level of practice, experience, training, and clinical and or professional roles and responsibilities as well as their practice settings and sociocultural context. This highlights the personalised features of micro-competencies.

Two, when considered in tandem with established milestones expected of all medical educators, micro-competencies also highlight the ‘general’ aspect of micro-competencies. The general aspect of micro-competencies is drawn from ‘stage specific requirements’ that all medical educators should achieve at a specific stage of their training.

Three, micro-competencies also vary with setting, stages of training, context, and time. Changes in these aspects of practice require re-evaluation of the medical educator’s micro-competencies. Micro-competencies allow the tutors, supervisors, reviewers, mentors, coaches, supervisors, assessors (henceforth faculty) and or employers to evaluate progress and provide medical educators with an opportunity to re-evaluate and reflect on their development and focus upon developing their learning plan.

Four, micro-competencies also acknowledge that they may be the basis of more than one competency and that without regular application will result in degradation of their abilities specifically communication and skills based micro-competencies. This highlights the time-specific nature of the micro-competency. Similarly, with medical educators often posted to different settings and or participate in training in different specialties involving learners of different backgrounds, experience and training underline the need for timely re-evaluation of micro-competencies.

Overall use of MEPs evidences the notion that micro-credentialling 127 could be built upon the achievement of personalised and general micro-competencies. Micro-credentialling allows medical educators, the organisation, the evaluators and potential recruiters to see the specific settings that a medical educator can function within, the capacity or roles and responsibilities that they can adopt, the level of supervision required and their overall progress towards attaining Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs). With EPAs built on micro-credentials, the trajectory and gaps on the course towards attaining a specific EPA are mapped out, aiding medical educators as they reflect upon and map their course towards their overall goals. Progress captured in longitudinal assessments will also help medical educators and faculty to personalise training and support programs.

Overall micro-competencies, their relationship with micro-credentialling and EPAs inform guidance on personal, professional, and research expectations upon medical educators and steer effective career progression, maturation of thought, philosophies, skills, and actions.

Limitations

Whilst our goal was to appreciate the scope of available literature on portfolios used by medical educators, this review is limited by the lack of longitudinal and holistic evaluations of portfolios.

Although the search process was vetted and overseen by the expert team, use of specific search terms and inclusion of only English language articles potentiates the possibility of key publications being omitted. In addition, whilst independent and concurrent use of thematic and content analysis by the team of researchers improved its trustworthiness through enhanced triangulation and transparency, biases cannot be entirely eradicated.

The inclusion of grey literature improves transparency in the synthesis of the discussion, but its themes may contain bias results and provide these opinion-based views with a ‘veneer of respectability’ despite a lack of evidence to support it. This raises the question as to whether grey literature should be accorded the same weight as published literature.

Conclusions

This SSR in SEBA has laid bare the range of data on MEPs and highlighted the gaps in prevailing concepts. Perhaps a critical consideration is the fact that MEPs continue to be used for a variety of roles and goals and remain influenced by local clinical, academic, personal, research, professional, ethical, psychosocial, emotional, cultural, societal, legal and educational factors underlining the heterogeneity of available data.

Recognising this fact, we propose to determine the key ‘ingredients’ of successful MEPs in a coming study. In the meantime, we look forward to continuing this discussion, evaluating how best to ensure this living document is effectively tended to and how effective and appropriate training and assessment processes can be set up to realise the full potential of MEPs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-6-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose advice and feedback greatly improved this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviations: MEP(s) Medical Educator Portfolio(s)

E-MEP(s) Electronic Medical Educator Portfolio(s)

SEBA Systematic Evidenced Based Approach

SSR Systematic Scoping Review

EPA(s) Entrustable Professional Activity/ies

PCC Population, Concept, and Context

PICOS Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome

STORIES Structured approach to the Reporting In healthcare education of Evidence Synthesis

BEME Best Evidence Medical Education

Authors’ Contributions: DZH, AJSL, RT, YTO, AP, EJXC, CWNQ, JYL, JJQT, MC, AMCC, ASIL, LW, SC, LKRK were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript. All authors were involved in data curation, formal analysis, investigation, preparing the original draft of the manuscript as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Chrystie Wan Ning Quek  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2266-7469

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2266-7469

Min Chiam  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0145-6256

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0145-6256

Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7350-8644

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7350-8644

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analysed during this review are included in this published article [and its supplementary files].

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Dalton CL, Wilson A, Agius S. Twelve tips on how to compile a medical educator’s portfolio. Med Teach. 2018;40(2):140-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sidhu NS. The teaching portfolio as a professional development tool for anaesthetists. Anaesth Intens Care 2015;43(3):328-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goliath CL. Diffusion of an e-portfolio to assist in the self-directed learning of physicians: An exploratory study. Dissert Abstract Int Sec A: Hum Soc Sci 2010;70(10-A):3729. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Izatt S. Educational perspectives: portfolios: the next assessment tool in medical education? NeoReviews. 2007;8(10):e405-e408. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thomas JV, Sanyal R, O’Malley JP, Singh SP, Morgan DE, Canon CL. A guide to writing academic portfolios for radiologists. (1878-4046 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuhn GJ. Faculty development: the educator’s portfolio: its preparation, uses, and value in academic medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11(3):307-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shinkai K, Chen CF, Schwartz BS, et al. Rethinking the educator portfolio: an innovative criteria-based model. Acad Med 2018;93(7):1024-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ingrassia A. Portfolio-based learning in medical education. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2013;19(5):329-336. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawson M, Nestel D, Jolly B. An e-portfolio in health professional education. Med Educ 2004;38(5):569-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bligh J, Brice J. The Academy of Medical Educators: a professional home for medical educators in the UK. Med Educ 2007;41(7):625-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brice J, Archer J, Isba R, Miller A. What is the Academy of Medical Educators, and what can it do for doctors in training? Foundation Years. 2008;4(8):335-336. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crosby RMHJ. AMEE Guide No 20: the good teacher is more than a lecturer - the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach 2000;22(4):334-347. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nikendei C, Ben-David MF, Mennin S, Huwendiek S. Medical educators: How they define themselves - Results of an international web survey. Med Teach 2016;38(7):715-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deshpande S, Chari S, Radke U, Karemore T. Evaluation of the educator’s portfolio as a tool for self-reflection: faculty perceptions. Educ Health 2019;32(2):75-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simpson D, Fincher Rm, Fau -Hafler JP, Hafler Jp, Fau -Irby DM, et al. Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship. Med Educ 2007;41(10):1002-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chandran L, Gusic ME, Lane JL, Baldwin CD. Designing a national longitudinal faculty development curriculum focused on educational scholarship: process, outcomes, and lessons learned. Teach Learn Med 2017;29(3):337-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simpson D, Hafler J, Brown D, Wilkerson L. Documentation systems for educators seeking academic promotion in U.S. medical schools. Acad Med 2004;79(8):783-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zobairi SE, Nieman LZ, Cheng L. Knowledge and use of academic portfolios among primary care departments in U.S. medical schools. Teach Learn Med 2008;20(2):127-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chandran L, Gusic M, Baldwin C, et al. Evaluating the performance of medical educators: a novel analysis tool to demonstrate the quality and impact of educational activities. Acad Med 2009;84(1):58-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lamki N, Marchand M. The medical educator teaching portfolio: its compilation and potential utility. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2006;6(1):7-12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ryan MS, Tucker C, DiazGranados D, Chandran L. How are clinician-educators evaluated for educational excellence? A survey of promotion and tenure committee members in the United States. Med Teach 2019;41(8):927-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ngo AV, Thapa MM. Documenting your career as an educator electronically. Pediatr Radiol 2018;48(10):1399-1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swanwick T, McKimm J, Clarke R. Introducing a professional development framework for postgraduate medical supervisors in secondary care: considerations, constraints and challenges. Postgrad Med J 2010;86(1014):203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tigelaar DE, Dolmans DH, de Grave WS, Wolfhagen IH, van der Vleuten CP. Portfolio as a tool to stimulate teachers’ reflections. Med Teach 2006;28(3):277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhargava P, Patel VB, Iyer RS, et al. Academic portfolio in the digital era: organizing and maintaining a portfolio using reference managers. J Digital Imaging 2015;28(1):10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8(1):19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33(1):147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levac D, Colquhoun H, Fau - O’Brien KK, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ruiz-Perez I, Petrova D. Scoping reviews. Another way of literature review. Med Clín (English Edition). 2019;153(4):165-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should i use? a review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health 2016;3:172-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thomas AA-O, Lubarsky S, Varpio L, Durning SJ, Young ME. Scoping reviews in health professions education: challenges, considerations and lessons learned about epistemology and methodology. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2020;25(4):989-1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ngiam LXL, Ong YA-O, Ng JX, et al. Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;1049909120950031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curricular Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guba EG, Lincoln Y.S. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook Qual Res. 1994:105-117. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krishna L, Yaazhini, Tay KT, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine – a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mack L. The philosophical underpinnings of educational research. Polyglossia 2010;19:5-11. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Scotland J. Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. Engl Lang Teach 2012;5:9-16. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thomas A, Menon AF, Boruff J, et al. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2014;9:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. J Philos Educ 2000;34(2):247-260. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Crotty M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: possibilities, challenges and potential outcomes. OnCUE J 2012;6(1):23-36. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kamal NHA, Tan LHE, Wong RSM, et al. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliat Med Care 2020;7(1):1-11. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ong RRS, Seow REW, Wong RSM. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care 2020;7(1):1-22. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW, et al. A Systematic Scoping Review of Systematic Reviews in Palliative Medicine Education. Palliat Med Care 2020;7(1):1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. Plos One 2020;15(5):e0232511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Frank J, Snell L, Sherbino J. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency Framework. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015. Accessed April 29, 2019. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf.

- 50. Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13(3):141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pham MA-O, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5(4):371-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25(1):72-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med 2013;11(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product ESRC Methods Programme Version 2006;1:b92. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, et al. Assessing mentoring: A scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PloS one 2020;15(5):e0232511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sawatsky AP, Parekh N, Muula AS, Mbata I, Bui TJMe. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Med Educ 2016;50(6):657-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto KJHmj. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns School of Medicine. Hawaii Med J 2007;66(4):102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0193001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer SJMt. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach 2010;32(2):148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15(9):1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Neal JW, Neal ZP, Lawlor JA, et al. What makes research useful for public school educators? Adm Policy Ment Health 2018;45(3):432-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wagner-Menghin M, de Bruin A, van Merriënboer JJJAiHSE. Monitoring communication with patients: analyzing judgments of satisfaction (JOS). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2016;21(3):523-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Elo S, Kyngäs HJJoan. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62(1):107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mayring PJActqr. Qualitative content analysis. Theor Found Basic Proced Softw Solut 2004;1:159-176. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Humble ÁMJIJoQM. Technique triangulation for validation in directed content analysis. Int J Qual Methods 2009;8(3):34-51. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Baldwin C, Chandran L, Gusic M. Guidelines for evaluating the educational performance of medical school faculty: priming a national conversation. Teach Learn Med 2011;23(3):285-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marušić A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;296(9):1103-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lewis KO, Baker RC. The development of an electronic educational portfolio: an outline for medical education professionals. Teach Learn Med 2007;19(2):139-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Brodell RT, Alam M, Fau -Bickers DR, Bickers DR. The dermatologist’s academic portfolio: a template for documenting scholarship and service. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4(11):733-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bannard-Smith J, Bishop S, Gawne S, Halder N. Twelve tips for junior doctors interested in a career in medical education. Med Teach 2012;34(12):1012-1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dolmans DH, Tigelaar D. Building bridges between theory and practice in medical education using a design-based research approach: AMEE Guide No. 60. Med Teach 2012;34(1):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Little-Wienert K, Mazziotti M. Twelve tips for creating an academic teaching portfolio. Med Teach 2018;40(1):26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Carroll RG. Professional development: a guide to the educator’s portfolio. Am J Physiol 1996;271(6 Pt 3):S10-S13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Taylor BB, Parekh V, Estrada CA, Schleyer A, Sharpe B. Documenting quality improvement and patient safety efforts: the quality portfolio. a statement from the academic hospitalist taskforce. J Gen Intern Med 2014:29(1):214-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Tigelaar DE, Dolmans DH, de Grave WS, Wolfhagen IH, van der Vleuten CP. Participants’ opinions on the usefulness of a teaching portfolio. Med Educ 2006;40(4):371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Blake K. The daily grind–use of log books and portfolios for documenting undergraduate activities. Med Educ. 2001;35(12):1097-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Klocko DJ. The use of course portfolios to document the scholarship of teaching. J Physician Assist Educ 2010;21(1):23-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Luks AM, Yukawa M, Fau -Emery H, Emery H. Disseminating best practices for the educator’s portfolio. Med Educ 2009;43(5):497-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Khan N, Khan MSF, Dasgupta P, Dasgupta PF, Ahmed K, Ahmed K. The surgeon as educator: fundamentals of faculty training in surgical specialties. BJU Int 2013;111(5):E266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Molenaar WM, Zanting A, van Beukelen P, et al. A framework of teaching competencies across the medical education continuum. Med Teach 2009;31(5):390-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ramani S, Leinster S. AMEE Guide no. 34: teaching in the clinical environment. Med Teach 2008;30(4):347-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Academy of Medical Educators. Professional standards for medical, dental and veterinary educators. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.medicaleducators.org/write/MediaManager/AOME_Professional_Standards_2014.pdf. Published 2014. Updated October 2014.

- 85. Gusic Maryellen E, Amiel J, Baldwin Constance D, et al. Using the AAMC toolbox for evaluating educators: you be the judge! Mededportal. 2013;9. [Google Scholar]

- 86. SingHealth DukeNUS Academic Medicine Education Institute. Assess your teaching competencies. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.singhealthdukenus.com.sg/amei/teaching-competencies. Published 2019.

- 87. Glassick CE. Boyer’s expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing scholarship, and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Acad Med 2000;75(9):877-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. National Health Service. Educator standards & guidance. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.nwpgmd.nhs.uk/educator-development/standards-guidance.

- 89. SingHealth Duke-NUS Medical Centre. Developing educators through a structured framework. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.singhealthdukenus.com.sg/amei/Pages/educators-framework.aspx.

- 90. Görlitz A, Ebert T, Bauer D, et al. Core Competencies for Medical Teachers (KLM)–A Position Paper of the GMA Committee on Personal and Organizational Development in Teaching. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2015;32(2):Doc23-Doc23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Si J. Needs assessment for developing teaching competencies of medical educators. Korean J Med Educ 2015;27(3):177-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Walsh A, Koppula S, Antao V, et al. Preparing teachers for competency-based medical education: Fundamental teaching activities. Med Teach 2018;40(1):80-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Rosenbaum M. Competencies for Medical Teachers. SGIM Forum 2012; 35(9):2-3. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Brink D, Simpson D, Crouse B, Morzinski J, Bower D, Westra R. Teaching competencies for community preceptors. Fam Med 2018;50(5):359-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. "Teaching as a competency": competencies for medical educators. Acad Med 2011;86(10):1211-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zabar S, Hanley K, Stevens DL, et al. Measuring the competence of residents as teachers. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(5 Pt 2):530-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Carraccio C, Englander R, Van Melle E, et al. Advancing competency-based medical education: a charter for clinician-educators. Acad Med 2016;91(5):645-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Maza Solano JM, Benavente Bermudo G, Estrada Molina FJ, Ambrosiani Fernández J, Sánchez Gómez S. Evaluation of the training capacity of the Spanish Resident Book of Otolaryngology (FORMIR) as an electronic portfolio. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2018;69(4):187-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Tochel C, Haig AF, Hesketh A, et al. The effectiveness of portfolios for post-graduate assessment and education: BEME Guide No 12. Med Teach 2009;31(4):299-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Taylor DCM, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: Implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Med Teach 2013;35(11):e1561-e1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ahmed MH. Reflection for the undergraduate on writing in the portfolio: where are we now and where are we going? J Adv Med Educ Prof 2018;6(3):97-101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Foucault ML, Vachon B, Thomas A, Rochette A, Giguère C. Utilisation of an electronic portfolio to engage rehabilitation professionals in continuing professional development: results of a provincial survey. Disabil Rehabil 2018;40(13):1591-1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ryland I, Brown J, O’Brien M, et al. The portfolio: how was it for you? Views of F2 doctors from the Mersey deanery foundation pilot. Clin Med 2006;6(4):378-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Webb TP, Aprahamian CF, Weigelt JA, et al. The Surgical Learning and Instructional Portfolio (SLIP) as a self-assessment educational tool demonstrating practice-based learning. Curr Surg 2006;63(6):444-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tartwijk J, Driessen E. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Med Teach 2009;31:790-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Joshi MK, Gupta P, Fau -Singh T, Singh T. Portfolio-based learning and assessment. Indian Pediatr 2015;52(3):231-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Driessen EW, Muijtjens AF, van Tartwijk J, van der Vleuten CPM, van der Vleuten CP. Web- or paper-based portfolios: is there a difference? Med Educ 2007;41(11):1067-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Buckley S, Coleman JF, Davison I, et al. The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 11. Med Teach 2009;31(4):282-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Tailor A, Dubrey S, Das S. Opinions of the ePortfolio and workplace-based assessments: a survey of core medical trainees and their supervisors. Clin Med 2014;14(5):510-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lingnan University. An Introduction to “The Full Teaching Portfolio” A Guide for Academic Staff. Accessed November 15, 2020 https://tlc.ln.edu.hk/tlc/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/LU_Teaching_Portfolio_Handbook-Full.pdf. Published 2015.

- 111. Fincher RME, Simpson D, Mennin S, et al. Scholarship in teaching: an imperative for the 21st century. Acad Med 2000;75:887-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Flynn JA. The educator’s portfolio. Accessed November 11, 2020 https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/The-Educators-Portfolio.pdf.

- 113. Upstate Medical University College of Medicine. Educator portfolio checklist and tips. Accessed November 15, 2020 https://www.upstate.edu/facultydev/pdf/educator-portfolio-checklist.pdf.

- 114. University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Educator’s portfolio. Accessed November 11, 2020 https://faculty.uams.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/112/2018/10/Educators-Portfolio-Template-Overview.pdf.

- 115. Williams BW, Byrne PF, Welindt D, Williams MV. Miller’s pyramid and core competency assessment: a study in relationship construct validity. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2016;36(4):295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Roberts KB, DeWitt TG, Goldberg RL, Scheiner AP. A program to develop residents as teachers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148(4):405-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Academic Pediatrics Association for the PAS Educational Scholars Program. Medical education portfolio. Accessed November 11, 2020 https://www.saem.org/resources/careers/medical-education-portfolio. Published 2008.

- 118. University of Arizona College of Medicine. Educator portfolio template. Accessed November 11, 2020 https://emergencymed.arizona.edu/sites/emergencymed.arizona.edu/files/uploads/AMES-Education-Portfolio.pdf.

- 119. Irby DM, Shinkai K, O’Sullivan P. The Educator’s portfolio: creation and evaluation. Accessed November 08, 2020. https://slideplayer.com/slide/5748090/

- 120. Roos M, Kadmon M, Kirschfink M, et al. Developing medical educators–a mixed method evaluation of a teaching education program. Med Educ Online 2014;19:23868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Gusic M, Amiel J, Baldwin C, et al. Using the AAMC toolbox for evaluating educators: you be the judge! MedEdPORTAL Publications 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 122. Gusic ME, Baldwin CF, Chandran L, et al. Evaluating educators using a novel toolbox: applying rigorous criteria flexibly across institutions. Acad Med 2014;89(7):1006-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Duke-NUS Medical School. Education portfolio. Accessed November 08, 2020. https://www.duke-nus.edu.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/education-portfolio-checklist-and-expanatory-notes.pdf?sfvrsn=2fe8e1c3_0.

- 124. McLachlan JC. The relationship between assessment and learning. Med Educ 2006;40(8):716-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Thistlethwaite J. More thoughts on ‘assessment drives learning’. Med Educ 2006;40(11):1149-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Wood T. Assessment not only drives learning, it may also help learning. Med Educ 2009;43(1):5-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Norcini J. Is it time for a new model of education in the health professions? Med Educ 2020;54(8):687-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-mde-10.1177_23821205211000356 for A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators by Daniel Zhihao Hong, Annabelle Jia Sing Lim, Rei Tan, Yun Ting Ong, Anushka Pisupati, Eleanor Jia Xin Chong, Chrystie Wan Ning Quek, Jia Yin Lim, Jacquelin Jia Qi Ting, Min Chiam, Annelissa Mien Chew Chin, Alexia Sze Inn Lee, Limin Wijaya, Sandy Cook and Lalit Kumar Radha Krishna in Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development