Purpose

To better prepare for potential future large-scale redeployments, this study examines quality of supervision and care as perceived by redeployed residents, fellows, and attendings during a COVID-19 surge.

Method

During April and May 2020, attendings, fellows, and residents redeployed at 2 teaching hospitals were invited to participate in a survey, which included questions on respondents’ prior experience; redeployed role; amount of supervision needed and received; and perceptions of quality of supervision, patient care, and interprofessional collaboration. Frequencies, means, and P values were calculated to compare perceptions by experience and trainee status. Narrative responses to 2 open-ended questions were independently coded; themes were constructed.

Results

Overall, 152 of 297 (51.2%) individuals responded, including 64 of 142 attendings (45.1%), 40 of 79 fellows (50.6%), and 48 of 76 residents (63.2%). Fellows and attendings, regardless of prior experience, perceived supervision as adequate. In contrast, experienced residents reported receiving more supervision than needed, while inexperienced residents reported receiving less supervision than needed and rated overall supervision as poor. Attendings, fellows, and experienced residents rated the overall quality of care as acceptable to good, whereas inexperienced residents perceived overall quality of care as worse to much worse, particularly when compared with baseline.

Conclusions

Narrative themes indicated that the quality of supervision and care was buffered by strong camaraderie, a culture of informal consultation, team composition (mixing experienced with inexperienced), and clinical decision aids. The markedly negative view of inexperienced residents suggests a higher risk for disillusionment, perhaps even moral injury, during future redeployments. Implications for planning are explored.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, redeployments often placed physicians in roles and environments that were different from their typical practice; created challenges to providing adequate supervision and support; and may, ultimately, have affected quality of patient care on a daily basis. 1–6 In preparing for potential future surges, it is important to learn from these redeployment experiences about how best to supervise physicians with varied prior experiences in their new environments. In this study, we focus on the experiences of physician attendings, fellows, and residents redeployed to the medical floors at 2 medical centers in New York. This study aims to answer 3 questions:

To what extent did the supervision provided to redeployed physicians match their perceived needs?

How did these perceptions differ by level of training and by familiarity of the physician with the setting/role?

What lessons can be drawn for future surges or pandemics?

Method

Design

This paper reports on a cross-sectional survey that explored how physicians redeployed to the medical floors perceived the quality of supervision and patient care during a COVID-19 surge. The Institutional Review Board at Northwell Health deemed the study exempt.

Setting

This study was conducted between April 16, 2020, and May 5, 2020, at 2 of Northwell Health’s teaching hospitals, Long Island Jewish Medical Center and North Shore University Hospital. Northwell Health is a 23-hospital system in the New York Metropolitan region. Combined, the 2 teaching hospitals typically have 1,256 medical floor beds. At the peak of the surge, the 2 hospitals were treating, at any given time, 1,617 patients, representing a 30% increase over presurge capacity. To meet these staffing demands, 297 physicians, including 142 attendings, 79 fellows, and 76 residents, were redeployed from other settings to the medical floors. This does not include the internal medicine residents who almost exclusively worked on COVID-19 medical floors, a context familiar to them. None of the redeployed physicians practiced in the role or setting to which they were assigned. Some had prior relevant experience, while others did not.

Participants and procedures

All 297 redeployed attendings, fellows, and residents were invited to participate in the survey. Redeployments lasted a minimum of 2 weeks and the survey was sent at the end of the second week of each redeployment. Reminders were sent daily for 5 days. The survey included items on demographics; voluntary versus mandated status; specialty; training level and program (residents and fellows only); number of years since they last functioned in their redeployed role on a medical floor (attendings only); amount of supervision needed and received; and the perceived quality of supervision, patient care, and interprofessional collaboration (see Supplemental Digital Appendix 1 at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B211 for the survey instrument).

The survey questions were developed by J.Q.Y., O.t.C., and K.A.F., guided by the study questions and prior research experience. For supervision, we asked respondents to rate, using 5-point scales: (1) how often the respondent needed and how often they received supervision at each of 3 levels while redeployed in the week before the survey; (2) how frequently they received less supervision than needed over the past week; and (3) the overall quality of the supervision. Similarly, participants were asked to rate, again using 5-point scales, the quality of care compared with baseline, overall quality of care, and the quality of the interprofessional collaboration compared with baseline. Narrative questions asked respondents to address areas that went well and areas that could be improved.

Data analysis

We divided respondents by training status (attending, fellow, or resident) and by experience status (yes/no). We defined prior experience for residents as having completed an internship in internal medicine (e.g., a dermatology resident), for fellows as having completed a residency in internal medicine (e.g., a nephrology fellow), and for attendings as having functioned as an attending (after their training was completed) on the medical floors at any point in the past. To compare supervision needed versus received by training and experience status, we calculated the percentage of respondents in each group who indicated “frequently” or “almost always” needing and “frequently” and “almost always” receiving a given level of supervision (direct, indirect, and independent). Means and standard deviations were calculated to compare how each group rated overall the frequency of receiving less supervision than needed, the quality of care, the quality of care compared with baseline, and the quality of interprofessional collaboration. Analyses were performed with RStudio (version 1.2.1335, build 1379, Boston, Massachusetts). Comments were de-identified and independently coded by 2 authors (J.Q.Y. and K.A.F.). The coding included content (e.g., teamwork) and valence (e.g., positive or negative). Codes were compared and modified iteratively. Differences were resolved through consensus between J.Q.Y. and K.A.F. All comments were reanalyzed with the final set of codes. Codes were then organized into categories and themes were constructed.

Results

Of the 297 invited to participate in the survey, 152 (51.2%) responded, including 64 of 142 attendings (45.1%), 40 of 79 fellows (50.6%), and 48 of 76 residents (63.2%) (see Table 1.) Across all responding physicians, 69.8% were mandated to be redeployed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Physicians Redeployed to COVID-19 Medical Floors

Quantitative findings

Supervision needed versus received and overall quality of supervision.

All attendings, all fellows, and experienced residents received levels of supervision that approximated their needs. In contrast, inexperienced residents reported supervision levels as less than needed on a regular basis (see Tables 2 and 3) and rated the overall quality of supervision as below 3.0 (i.e., the “poor” to “neither poor nor good” range). (See Table 3.)

Table 2.

Perceptions of Supervision Needed Versus Received for Residents Redeployed to Medical Floors by Experience, Percentage Reporting Frequently or Almost Alwaysa

Table 3.

Perceptions of Quality of Care Amongst Physicians Redeployed to the Medical Floors by Level of Training, Setting, and Prior Experience

Quality of care and interprofessional collaboration.

All groups rated the quality of care as somewhat lower compared with baseline (between “worse” and “about the same”) except for inexperienced residents, who perceived quality as “worse” to “much worse.” All reported the overall quality of care and the quality of interprofessional collaboration as acceptable to good, except for the inexperienced residents, who reported both as below “acceptable/usual” (see Table 3).

Qualitative findings

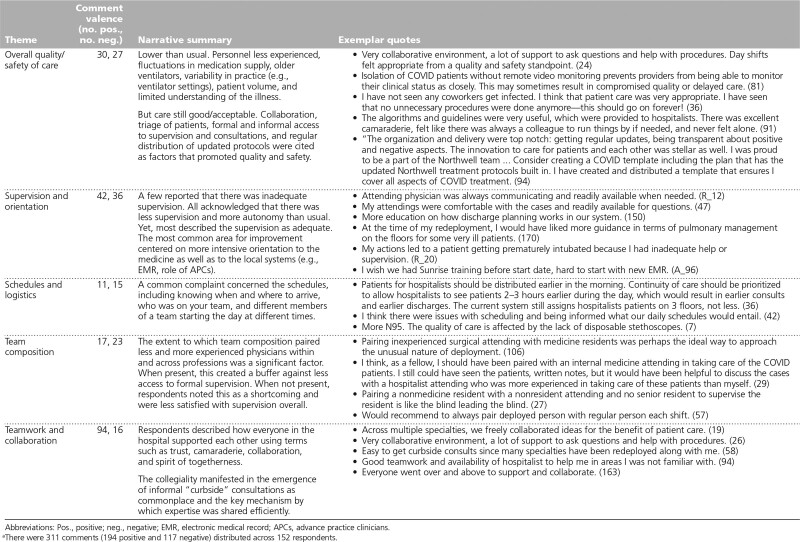

Table 4 presents the primary themes that emerged from the narrative comments with exemplar quotes. Overall quality of care was perceived as lower than usual due to many factors, including less experienced personnel, fluctuations in medication supply, older ventilators, variability in practice (e.g., ventilator settings), patient volume, and limited understanding of the illness. However, care was still described as “acceptable” to “good” by most groups, except by the inexperienced residents.

Table 4.

Themes From the Narrative Commentsa of Physicians Redeployed to Medical Floors

All groups acknowledged that there was less supervision and more autonomy than usual. Yet, most described the supervision as adequate. Respondents appreciated teams being composed to pair together less experienced and more experienced clinicians, both within and across the professions. When present, this created a buffer against less access to formal supervision; it was a common complaint when this did not happen (see Table 4). Inexperienced residents were the only group to overwhelmingly cite team composition as inadequate, consistent with their above rating of supervision quality as less than “acceptable/safe.”

Collaboration, formal and informal access to supervision, “curbside” (i.e., informal hallway) consultations, adequate personal protective equipment, and provision of protocols were cited as significant positive factors mitigating the effects of a less experienced workforce in a chaotic and stressed environment. Respondents described how everyone in the hospital supported each other using terms such as trust, camaraderie, collaboration, and spirit of togetherness. Informal curbside consultations, as a mechanism to share expertise, emerged from this atmosphere of collaboration and were a key “safety net” for supervision and quality of care. The most common area for improvement centered on more intensive orientation to the medicine as well as to the local systems (e.g., electronic medical record, role of advance practice clinicians), especially for those without experience.

Discussion

Despite immense strains, most groups of physicians in this survey perceived the supervision and patient care as still adequate to good. There was, however, an important exception; residents without prior experience had negative views of the quality of supervision and patient care, both in general and compared with baseline. Moreover, inexperienced residents perceived the amount of supervision they received as less than needed, while experienced residents reported the opposite.

The markedly different perceptions among inexperienced residents compared with all other groups has several possible explanations. First, it could be that these negative perceptions were in fact inaccurate (i.e., too negative). Self-assessment is a notoriously difficult skill. 7 Kruger and Dunning have established that, as trainees transition from unconscious incompetence to conscious incompetence to competence, the awareness of incompetence paradoxically increases. 8 Perhaps the inexperienced residents occupied a developmental space in which they overestimated their incompetence and supervision needs and underestimated the quality of care. 9 Junior trainees might attribute the high death rate to the quality of care rather than the limits of science at that time. In this scenario, interventions would focus on reassuring the inexperienced junior trainees to adjust their perceptions of the quality of supervision and care upward.

Second, it is possible that the positive perceptions of the 5 other groups were inaccurate (i.e., too positive). Several known psychological mechanisms may have operated to influence judgment of their own competence and need for supervision, and even the collective team competence at the units. Cognitive dissonance theory states that 2 cognitions in 1 person at the same time are dissonant if the obverse (opposite) cognitions simultaneously exist. 10 Dissonance brings psychological discomfort and motivates efforts to reduce the dissonance, which in turn can lead to avoidance of information likely to increase the dissonance. 11 Perhaps redeployed attendings, fellows, and experienced residents—initially cognizant of their incompetence, but nevertheless expected to deliver competent care—overestimated the quality of the supervision and care to reduce dissonance and preserve ego integrity. If this overestimation was a significant factor, then the question becomes whether the downsides (e.g., not recognizing inadequate supervision) outweigh the upside (e.g., preserved self-esteem). Interventions would focus on helping these groups have a more accurate (less positive) perception and to recognize and act when the supervision and/or quality of care is inadequate.

Finally, it is also possible that the positive perceptions of the 5 other groups were due to the fact that the supervision provided truly met or exceeded their needs, whereas the markedly negative views held by inexperienced residents may in fact be an accurate reflection of their role in the care provided. In this case, the fundamental solution would revolve around reallocating the oversupervision provided to experienced residents to the inexperienced residents, who reported undersupervision.

This study measured the perception of supervision and quality of care, not actual quality of care and supervision. If the patient outcomes were negatively impacted by inadequate supervision, then there are serious ethical implications, especially in a context where different groups may have been simultaneously under- and oversupervised. However, our data do not permit such a conclusion. Regardless of how the views of inexperienced residents might align with actual quality of the supervision and care, their perceptions are concerning. Redeployment appears to have put them in a role and context in which they delivered care to very ill patients that they perceived as not just lower than baseline but overall unacceptable. This has the potential to create significant distress as the inexperienced residents attempt to reconcile the gap between the care they provided and the care they feel they should have provided. 12 When this gap transgresses deeply held moral beliefs, it can lead to what some have labeled “moral injury.” 13 For some of these inexperienced residents, this gap might have challenged their own values and norms so fundamentally as to lead to negative feelings such as shame, guilt, and betrayal and put them at higher risk, both now and over the course of their careers, for burnout. 14 This experience could have enduring effects on their professional lives, choices, and behaviors. Future research should follow redeployed cohorts longitudinally to explore this possible sequalae.

The perceptions of inexperienced residents have important implications for planning for future surges. Vygotsky’s concept of the zone of proximal development seems relevant. Learners need to be placed in roles where the distance between their actual skill set and the skills required by the role is sufficiently proximal. 15,16 Most groups appear to have been within their zone of proximal development. In contrast, inexperienced residents appear to have been placed into the zone of development that was not proximal enough. For future surges, hospitals may need to be more judicious in how they deploy inexperienced residents. For example, more affordances in the workplace could be made available. The orientations, the pairing of more and less experienced physicians on teams, scaffolds, direct and indirect supervision, and ongoing support should be especially robust for inexperienced residents. Moreover, training programs and clinical departments could develop mechanisms, such as a supervision response team activated by text message, that could make it easier for residents to ask for and receive additional supervision when needed. In the context of this study, some of this need could have been met by reallocating the “excess” support provided to experienced residents and other groups to inexperienced residents.

In the above discussion, a number of key recommendations have been identified to help improve the environment of the inexperienced residents. Special attention should be made to minimize both under- and oversupervision. This requires careful construction of teams composed of both less and more experienced physicians and consideration of something like a “rapid-supervision-response” team. Attendings, fellows, and more experienced residents can be actively encouraged to not underestimate the supervision needs of the inexperienced residents and identify ways that less experienced residents can communicate without fear of retaliation when they feel consistently undersupervised. Orientations should be provided, in advance, to both the clinical medicine and the local systems. When applicable, easy-to-read visual aids depicting diagnostic and treatment algorithms should be constructed. Finally, informal consultation should be promoted and leveraged (see List 1).

This study has several limitations. It is limited to 2 hospitals in the same health system. It is unclear how generalizable these results are to other regions and contexts. For example, survey respondents largely described access to personal protective equipment as adequate. This was not true for many hospitals. The study also reports perceptions of the quality of supervision and patient care. We do not have actual outcome data for either. It could be that the perceptions differ from actual outcomes. The direction bias may be toward a more positive view of quality given the comradery and the fact that these physicians are commenting on their own care and the care of those who they know and likely respect.

In conclusion, this study of 2 hospitals suggests that attendings, fellows, and experienced residents perceived the quality of supervision and patient care as lower than usual but still acceptable. Inexperienced residents perceived both as unacceptable. The mitigating factors can inform future planning. Special attention needs to be given to how inexperienced residents are oriented, supervised, and supported.

List 1.

Key Recommendations

Provide easy-to-read visual aids that depict diagnostic and treatment algorithms

Post schedules in a single, central, easy-to-access digital hub so changes are seen by everyone

Provide orientations to both clinical medicine and local systems just before and in first few days, especially for those without experience

Compose teams with a mix of less and more experienced providers

Promote and leverage informal consultation

Develop mechanisms by which trainees in need of more supervision can activate the support (e.g., supervision rapid-response team)

Implement process by which trainees who experience consistent undersupervision can escalate the concern without fear of retaliation

Actively train more experienced physicians on the importance of not underestimating the supervision needs of the less experienced and the importance of initiating check-ins

Minimize both under- and oversupervision; pay special attention to residents without prior experience in the setting/role (as opposed to residents with experience and fellows and attendings in general)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content for this article is available at http://links.lww.com/ACADMED/B211.

Funding/Support: None reported.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: The Institutional Review Board at Northwell Health deemed the study exempt.

Contributor Information

Karen A. Friedman, Email: kfriedma@northwell.edu.

Krima Thakker, Email: kthakker@northwell.edu.

Marije P. Hennus, Email: m.p.hennus@umcutrecht.nl.

Martina Hennessy, Email: mhenness@tcd.ie.

Aileen Patterson, Email: patteram@tcd.ie.

Andrew Yacht, Email: ayacht@northwell.edu.

Olle ten Cate, Email: t.j.tencate@umcutrecht.nl.

References

- 1.Dennis B, Highet A, Kendrick D, et al. Knowing your team: Rapid assessment of residents and fellows for effective horizontal care delivery in emergency events. J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12:272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flotte TR, Larkin AC, Fischer MA, et al. Accelerated graduation and the deployment of new physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acad Med. 2020;95:1492–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Situation report–111. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200510covid-19-sitrep-111.pdf?sfvrsn=1896976f_6. Published May 10, 2020. Accessed August 26, 2020.

- 4.Fraher EP, Pittman P, Frogner BK, et al. Ensuring and sustaining a pandemic workforce. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2181–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall AK, Nousiainen MT, Campisi P, et al. Training disrupted: Practical tips for supporting competency-based medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Teach. 2020;42:756–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross SW, Lauer CW, Miles WS, et al. Maximizing the calm before the storm: Tiered surgical response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID-19). J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1080–1091.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: A reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(suppl 10):S46–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:1121–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finn KM, Metlay JP, Chang Y, et al. Effect of increased inpatient attending physician supervision on medical errors, patient safety, and resident education: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:952–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MK, Clark JD, Jehle A. Cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger). Wiley Online Library. Published October 26, 2015. doi: 10.1002/9781405165518.wbeosc058.pub2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein J, McColl G. Cognitive dissonance: How self-protective distortions can undermine clinical judgement. Med Educ. 2019;53:1178–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopacz MS, Ames D, Koenig HG. It’s time to talk about physician burnout and moral injury. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: Moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36:400–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford EW. Stress, burnout, and moral injury: The state of the healthcare workforce. J Healthc Manag. 2019;64:125–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groot F, Jonker G, Rinia M, Ten Cate O, Hoff RG. Simulation at the frontier of the zone of proximal development: A test in acute care for inexperienced learners. Acad Med. 2020;95:1098–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.