Abstract

Objective:

In this study, we assessed patient knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about brain health and strategies for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) prevention.

Methods:

We administered a Web-based survey consisting of 17 questions about brain health and strategies for ADRD prevention in a convenience sample of 1661 patients in an integrated healthcare delivery system in Washington state between February and March 2018. We calculated frequency distributions of the quantitative data and conducted inductive content analysis of qualitative data.

Results:

Most respondents were female (77%), 51–70 years of age (64%), and white (89%). Although most agreed it is possible to improve brain health and reduce personal ADRD risk, one-third lacked confidence that they could take action to reduce personal ADRD risk. Participants’ responses to open-ended questions revealed 10 themes grouped into 3 organizing categories regarding their perceptions about how to prevent ADRD onset: (1) understand ADRD; (2) stay engaged; and (3) manage one’s own health and healthcare.

Conclusions:

Survey respondents were engaged and aware of dementia prevention, but they lacked access to personally actionable evidence..

Keywords: aging, disease prevention, gerontology, health promotion, neurological disorders, public health

Approximately 6 million persons in the United States (US) are living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), a number expected to rise to 14 million by 2050.1 Given the significant burden this will place on the US healthcare system, increasing resources are being deployed to summarize the evidence for the prevention of ADRD as well as prioritize efforts moving forward. In 2017, The Lancet Commission, the National Academy of Sciences, and the World Health Organization published major reports summarizing evidence regarding ADRD prevention and treatment.2–4 Evidence highlighted in these reports emphasizes that by addressing modifiable risk factors, approximately one-third of ADRD cases could be prevented.2

Any effort attempting population risk reduction requires the public to have an informed understanding of evidence-based prevention efforts. Yet, previous reports have demonstrated important gaps between patient knowledge and scientific evidence related to ADRD prevention. For example, Cations et al5 conducted a systematic review synthesizing surveys assessing knowledge and attitudes about the prevention and treatment of ADRD. They found that nearly half of respondents across 34 studies agreed that ADRD are a normal and non-preventable part of aging.5 However, there is a paucity of qualitative research examining public awareness of ADRD prevention. As new evidence emerges on the topic, a qualitative assessment could complement quantitative findings, and offer a depth of understanding regarding underlying perceptions and motivations for ADRD prevention. Thus, our objective was to conduct a contemporary US survey to assess knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about brain health and strategies for ADRD prevention using a mixed-method approach. This study aims to provide insights into patients’ perspectives regarding the role of healthcare and behavior in brain health and ADRD prevention as well as where patients get their information on these topics.

METHODS

Survey Design

We assembled a Web-based survey in 2 phases to assess knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about brain health and ADRD prevention among members of Kaiser Permanente Washington (KPW), an integrated healthcare delivery system in Washington state. First, we drafted initial questions based on a review of the latest evidence regarding dementia prevention. Specifically, we adapted questions from the 2006 Brain Health Poll administered by the American Society on Aging and the Metlife Foundation6 and questions from other national surveys on dementia prevention7 to create the survey. Questions were included that focused on concepts highlighted in recent reports, such as the preventability of ADRD and strategies used for ADRD prevention. We sought feedback on the survey from the KPW Senior Caucus, which serves as advocates of healthy aging and a source of advice to the KPW medical and research community. The study team incorporated KPW Senior Caucus feedback into a final survey instrument consisting of 17 questions that assess demographics; knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes regarding brain health and ADRD prevention; and information-seeking behavior for brain health.

Demographic measures included age, level of education, sex, employment, household income, and race/ethnicity. Attitudes, defined as individuals’ evaluation of a particular behavior,8 and beliefs, defined as what individuals assume to be true8 toward overall brain health were assessed with 3 survey items: (1) How important is it for people to have their thinking abilities checked? (2) To what extent can people improve their brain health? and (3) How useful is regular exercise for improving a person’s brain health?

Participants’ attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs toward ADRD prevention were assessed with 5 items: (1) whether it is possible to reduce the risk of ADRD; (2) their confidence level that they could take action now to reduce their risk of ADRD; (3) the average person’s risk for developing ADRD over their lifetime (response options included deciles from 0% to 100%); (4) what percentage of ADRD cases they think can be prevented (same response options); and (5) at what age should people start to take action to reduce their risk of ADRD. All other items used Likert scale or categorical response options. One question asked: “What do you think a person can do to help reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease or other forms of dementia?”

Response options included 10 activities (ie, exercise, socialization, relaxation, meditation, healthy diet/nutrition, take appropriate medications, quit smoking, moderate alcohol use, puzzles/brain games, adequate sleep), as well as a free-text, open-ended component wherein participants were able to provide additional perspective using their own words about what they perceived could reduce ADRD risk. Finally, participants were asked to select the most common source where most people their age go to learn about the brain and ways to keep it healthy, categorized into healthcare professionals, community members, and media sources.

Participants

Participants were recruited through the January issue of Northwest Health News, a monthly electronic newsletter disseminated to KPW members. The newsletter contained information that introduced the study and provided a link that interested participants could use to direct to the Web-based survey. We collected data using Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com). Participants were eligible if they were aged 18 or older, were KPW members, and could read and write in English. There was no incentive for completing the survey.

Data Analysis

We exported data from Survey Monkey into Microsoft Excel for descriptive analysis. Qualitative data were uploaded into Atlas.ti Version 7 (Berlin, Germany) and analyzed concurrently with the quantitative data analysis. We conducted an inductive thematic analysis, a process used to summarize the underlying attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs described by study participants.9 Using this approach, a lead coder reviewed open-ended responses on strategies to reduce ADRD risk and derived codes based on participant quotes. In consultation with the study team, we developed a codebook and applied codes to segments of text that represented specific attitudes, knowledge, and beliefs about ADRD among study participants. The study team communicated regularly to review and refine the codes and confirm agreement regarding the interpretation of quotes attached to each code. The team created a visual thematic network to facilitate analysis. In this process, emergent basic themes regarding respondent perceptions about ADRD prevention were grouped into organizing themes determined by the study team on the basis of their thematic content. The team defined and described all themes and explored and interpreted patterns in participant responses within and across themes.10 Once all data were analyzed, the team met to discuss and determine areas where qualitative and quantitative data revealed similar or different results.

RESULTS

A total of 1661 respondents completed the survey. Table 1 describes respondent characteristics. Most respondents were female (77%), between the ages of 51 and 70 years(64%), and white (89%). Over half (67%) had obtained a bachelor’s degree and 46% were retired.

Table 1.

Survey Respondent Characteristics (N = 1661)

| Respondents N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 1274 (76.7) |

| Male | 317 (19.1) |

| Non-binary | 3 (0.2) |

| Prefer not to answer/skipped | 67 (4.0) |

| Age, years | |

| 18–50 | 243 (14.6) |

| 51–70 | 1055 (63.5) |

| 71–80 | 300 (18.1) |

| ≥81 | 59 (3.6) |

| Skipped | 3 (0.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 1470 (88.5) |

| Asian | 39 (2.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 21 (1.3) |

| Black or African-American | 18 (1.2) |

| Other | 43 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to answer/skipped | 109 (6.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity | 1512 (91.0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 42 (2.5) |

| Don’t know/prefer not to answer/skipped | 107 (6.4) |

| Education | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 1120 (67.4) |

| Some post-secondary education | 407 (24.5) |

| High school graduate or GED | 72 (4.3) |

| Some high school | 1 (0.0) |

| Prefer not to answer/skipped | 61 (3.7) |

| Employment status | |

| Retired | 770 (46.4) |

| Full time employment | 502 (30.2) |

| Doing volunteer or unpaid work | 181 (10.9) |

| Part time employment | 160 (9.6) |

| Self-employed | 152 (9.2) |

| Homemaker | 96 (5.8) |

| Disabled/unable to work | 36 (2.2) |

| Looking for paid work | 16 (1.0) |

| Student | 16 (1.0) |

| Prefer not to answer/skipped | 63 (3.8) |

| Annual household income, $ | |

| ≤50,000 | 339 (20.4) |

| 50,000–74,999 | 314 (18.9) |

| 75,000–100,000 | 291 (17.5) |

| ≥100,000 | 404 (24.3) |

| Don’t know/prefer not to answer/skipped | 313 (18.8) |

Quantitative Findings

Table 2 describes the quantitative results for participants’ attitudes toward brain health. Nearly all respondents (94%) indicated that it is very/somewhat important to have thinking abilities checked at healthcare appointments. Nearly half of participants (48%) reported that brain health “can improve a little,” and 41% reported that brain health “can improve a lot.” Almost all respondents (96%) reported that regular exercise is very/somewhat useful for improving a person’s brain health.

Table 2.

Brain Health Attitudes and Beliefs (N = 1661)

| BRAIN HEALTH ATTITUDES AND BELIEFS | Respondents, N (%) |

|---|---|

| How important is it for people to have their thinking abilities checked just like they have physical check-ups? | |

| Very/somewhat important | 1565 (94.2) |

| Not important | 35 (2.1) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 61 (3.7) |

| Extent that brain health can be improved | |

| Can improve a lot | 679 (40.9) |

| Can improve a little | 802 (48.3) |

| Cannot do much to improve | 66 (4.0) |

| Cannot do anything to improve | 3 (0.2) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 109 (6.6) |

| Usefulness of regular exercise for improving a person’s brain health | |

| Very/somewhat useful | 1586 (95.5) |

| Not at all useful | 11 (0.7) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 30 (1.8) |

Table 3 describes the quantitative results for participants’ knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes toward ADRD prevention. Most (73%) strongly or somewhat agreed that it is possible to reduce one’s risk of developing dementia. However, nearly one-third (31%) of participants reported they were not very or not at all confident that they could take action now to reduce their risk of ADRD. Participants reported a variety of responses for estimating one’s average lifetime risk of ADRD, ranging from 0%–10% to 91%–100% response categories; the most common response was 51%–60% (26% of respondents). Likewise, respondents stated a range of estimates for preventability of ADRD, ranging from 0%–10% to 91%–100% response categories, with nearly one-fourth reporting that they did not know or skipped the question. Respondents also reported a range of ages at which people should start to take action to reduce their risk of ADRD, with most responses (70%) indicating an age prior to 60 years and 20% at any age.

Table 3.

ADRD Prevention Knowledge and Beliefs (N = 1661)

| ADRD PREVENTION KNOWLEDGE AND BELIEFS | Respondents, N (%) |

|---|---|

| It is possible to reduce the risk of a person developing AD or others forms of dementia? | |

| Strongly/somewhat agree | 1207 (72.7) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 165 (9.9) |

| Strongly/somewhat disagree | 158 (9.5) |

| No opinion | 5 (0.3) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 121 (7.3) |

| Confidence level that they could take action now to reduce risk of AD or other forms of dementia. | |

| Very/moderately confident | 1011 (60.9) |

| Not very/at all confident | 516 (31.1) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 134 (8.1) |

| Average person’s risk for developing AD or other forms of dementia in their lifetime. | |

| 0–10% | 52 (3.1) |

| 11–20% | 183 (11.0) |

| 21–30% | 282 (17.0) |

| 31–40% | 246 (14.8) |

| 41–50% | 194 (11.7) |

| 51–60% | 241 (26.2) |

| 61–70% | 118 (7.1) |

| 71–80% | 98 (5.9) |

| 81–90% | 29 (1.7) |

| 91–100% | 12 (0.7) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 206 (12.4) |

| How many cases of AD or other forms of dementia can be prevented? | |

| 0–10% | 229 (13.8) |

| 11–20% | 216 (13.0) |

| 21–30% | 242 (14.6) |

| 31–40% | 147 (8.9) |

| 41–50% | 149 (9.0) |

| 51–60% | 145 (8.7) |

| 61–70% | 61 (3.7) |

| 71–80% | 50 (3.0) |

| 81–90% | 27 (1.6) |

| 91–100% | 13 (0.8) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 382 (23.0) |

| At what age should people start to take action to reduce their risk of ADRD? | |

| <18 years | 226 (13.6) |

| 19–29 years | 208 (12.5) |

| 30–39 years | 255 (15.4) |

| 40–49 years | 251 (15.1) |

| 50–59 years | 227 (13.7) |

| 60–69 years | 70 (4.2) |

| 70–79 years | 9 (0.5) |

| ≥80 years | 3 (0.2) |

| Any age | 321 (19.3) |

| Don’t know/skipped | 91 (5.5) |

| What do you think a person can do to help reduce the risk of developing AD or other forms of dementia? | |

| Exercise/stay active | 1575 (94.8) |

| Healthy diet/nutrition | 1506 (90.7) |

| Socialization | 1476 (88.9) |

| Get adequate sleep | 1424 (85.7) |

| Puzzles/brain games | 1199 (72.2) |

| Quit smoking | 1080 (65.0) |

| Moderate alcohol use | 961 (57.9) |

| Relaxation | 896 (53.9) |

| Meditation | 874 (52.6) |

| Take appropriate medications | 761 (45.8) |

Note.

Abbreviation: ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias

Moreover, respondents identified a wide range of activities they believed could help prevent or delay ADRD. The most common responses were exercising/staying active (95%), maintaining a healthy diet/nutrition (91%), socializing (89%), and getting adequate sleep (86%). Less than half (46%) reported that taking appropriate medications could help reduce the risk of ADRD.

As for preferred sources of information regarding brain health, primary care physicians (PCPs) (83%), spouse/partners (52%), and Internet/Web (81%) were cited as the most common healthcare professional, community member, and media source of information, respectively.

Qualitative Findings

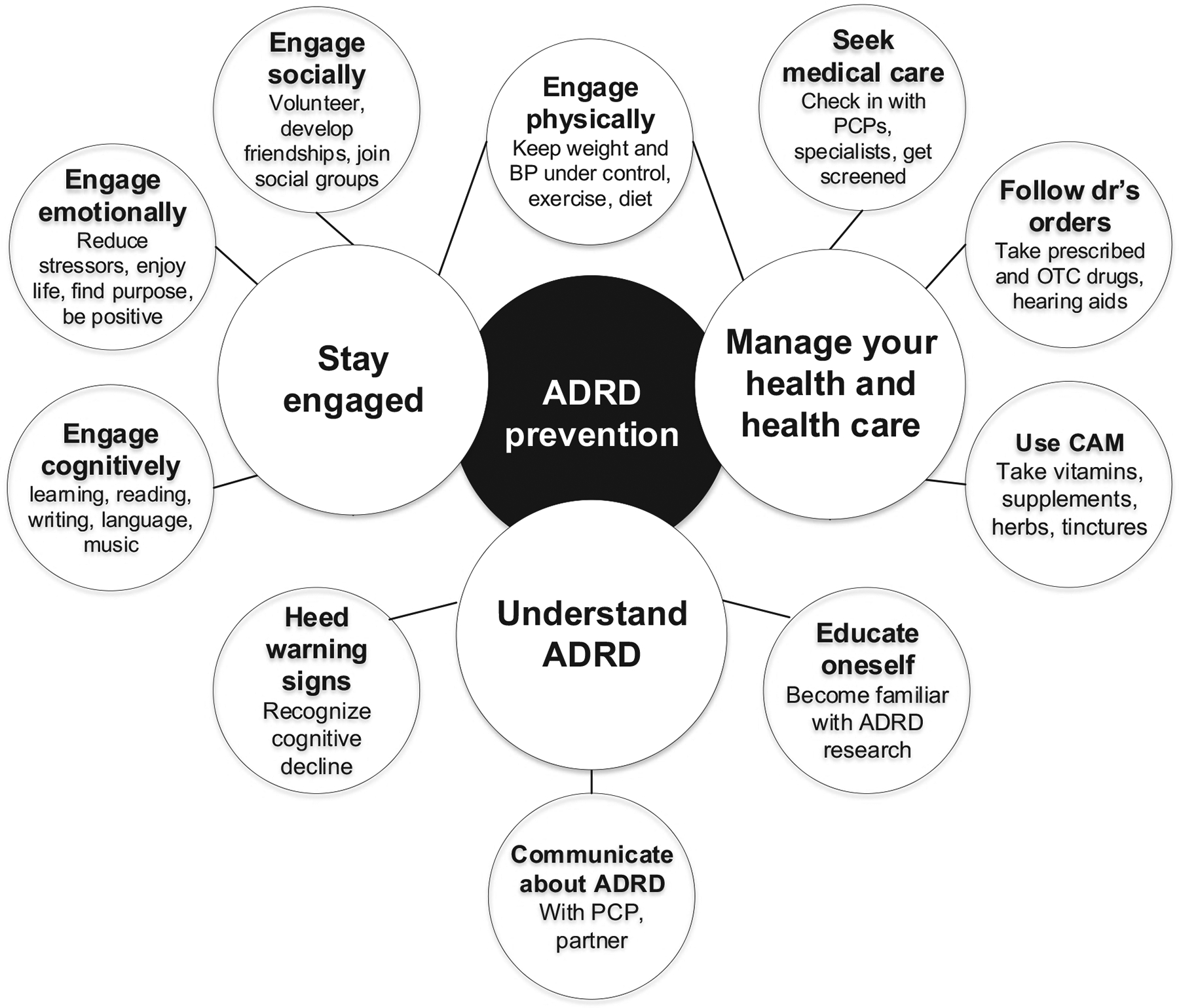

Participants who responded to the free-text, open-ended component of the question: “What do you think a person can do to help reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s Disease or other forms of dementia?” (N = 232) added detail to the response options provided regarding additional activities that they perceived could reduce one’s risk of ADRD. Participants described a range of activities, attitudes, and beliefs that expanded upon their responses to the quantitative survey items. We organized the data into 3 overarching organizing themes (understand ADRD, stay engaged, manage your health and healthcare) and their corresponding basic themes that emerged from the data, illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thematic Network: Beliefs about ADRD Preventiona.

Note.

a: Organizing themes are denoted by large circles; basic themes are denoted by smaller circles.

Abbreviations: ADRD, Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias; BP, blood pressure; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; OTC, over-the-counter; PCP, primary care physician

Understand ADRD

In free-text responses, participants described the value of “learn[ing] about advances in biomedical research” as well as “having regular check-ups with your doctor.” Further reflecting these themes, one participant stated: “I think brain science is evolving and so it is important to touch base with healthcare providers, and also stay on top of credible research as available to public.” Respondents also said patients should “develop awareness of [cognitive] lapses” and “take it seriously when someone says they are concerned about their brain functioning.”

Moreover, some participants expressed doubt that dementia prevention is possible, often based on their observations of others’ experiences. For example, one responded noted: “I know too many people that did literally everything ‘right’ and still ended up with dementia.” Other respondents expressed doubt or lack of knowledge about the strength of the evidence for specific prevention approaches. Illustrating this theme, these respondents reported: “They say all of these [referring to response options provided] help, but I really don’t believe that” and “All of the above are recommended by various sources, but I have no idea which actually work.”

Respondents described the importance of communicating with healthcare professionals, particularly PCPs, as well as family members, such as their partner/spouse, about ADRD. Of the small number of participants who did not indicate a healthcare professional source of information, those participants, such as this one, shared their confusion about the most appropriate healthcare provider to disseminate information about keeping one’s brain healthy, stating: “I definitely would like to know which physician to talk to about advances in diagnosing, preventing or reducing the risks of developing Alzheimer’s and other dementia.” Many reiterated the importance of social support. For example, this respondent advised: “understand the symptoms and have a plan in the event of decline, ie, family member or trusted friend or social network that can help with appropriate support.”

Stay engaged.

Respondents highlighted the importance of engaging socially, emotionally, cognitively, and physically to prevent or delay ADRD onset. They provided specific examples of socialization they believed could reduce their risk of ADRD. Respondents advised: “Develop healthy interpersonal skills” and “have stable, loving relationships with family and friends.” Accordingly, respondents revealed that in general, reducing stress, maintaining a positive attitude, and improving mental health were critical to reducing dementia risk. For example, one participant reported: “Reducing stress and being a part of something bigger than yourself, through things like having a pet, believing in a higher cause, and volunteering” could reduce dementia risk.

Respondents noted that engaging in intellectual undertakings and “keeping your brain active” was valuable in staving off ADRD. They emphasized their beliefs that “doing complex mental activities” such as playing or learning to play a musical instrument, learning a new language, and continuing to read and write so as to “challenge your brain with something new” and “learn and develop new skills” could help delay or avoid ADRD onset. They offered examples of specific activities they believed would be helpful, such as “reducing screen time and spending time outside” and “having sex frequently” and “running steep hills.”

In addition to advocating for moderate use of and abstention from alcohol, participants widely recommended avoiding recreational drugs, processed foods, and high-sugar diets. Others maintained that avoiding aluminum is essential to dementia prevention, such as these participants who stated: “quit using aluminum pots and pans,” “avoid aluminum in skin care and deodorant products,” and “eliminate canned foods due to link now realized between canned foods and Alzheimer’s.” Many participants emphasized the value of sustaining a balanced diet suggesting, for example, that “specifically, an antiinflammatory diet, such as the Mediterranean style of eating” or “intermittent fasting” or “eating leafy greens every day” would help prevent ADRD.

Manage health and healthcare.

Participants expressed a preference for exhausting means other than medications for dementia prevention, stating: “[I am] not a fan of medications as an initial choice of treatment” and, as summarized by this participant:

The data of which I am aware indicates that other factors (diet, exercise, low stress, etc) are currently believed to be the primary drivers, in addition to genetics. I would want my medical team to take a conservative approach, as I believe medication is over-prescribed in the US generally.

However, regardless of their perception of the utility of appropriate medication, participants indicated that seeking regular healthcare, including appropriate hearing and cognitive screenings, as well as following physicians’ orders could facilitate ADRD prevention. Reflecting this theme, these participants advised: “Get your hearing checked and wear a hearing aid if necessary. Loss of hearing can cause portions of your brain to lose function,” and “Have regular check-ups with your doctor,” which can assist in “early diagnosis, so you can get the right advice and take action.”

Other participants reported that taking “natural supplements” and “using supplements widely accepted in the alternative medical community” could help reduce the risk of dementia. Specifically, participants identified various fish oils, turmeric, cinnamon, and ginkgo as potentially helpful in this endeavor.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we administered a Web-based survey to assess knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes about brain health and ADRD prevention. Although most agreed it is possible to improve brain health generally and to reduce one’s risk of ADRD, one-third lacked confidence to take action now to reduce their risk. Respondents reported highly variable estimates for the average lifetime risk of developing ADRD, the preventability of ADRD, and the age at which people should start to take action to reduce their risk of ADRD. Respondents emphasized the value of keeping abreast of evidence pertaining to ADRD, staying engaged, and managing one’s health. They reported PCPs and the Internet as the most sought-after sources of information on brain health. This study uniquely contributes to the literature by using a mixed-methods approach, adding a depth of understanding of public awareness regarding prevention of ADRD.

Compared to the systematic review by Cations et al,5 our survey respondents were more likely to report that it is possible to reduce one’s risk of ADRD. This likely reflects the demographics (eg, highly educated) of our survey respondents, and thus, our results likely reflect an upper end of ADRD knowledge among the public. It also could reflect that beliefs have changed over time as more information regarding dementia has been disseminated to the public. Despite that, we observed a wide range of beliefs about ADRD prevention. Specifically, respondents estimated the average lifetime risk of developing ADRD from 0% to 100%, with several reporting high risk. It is important to note that lifetime risk of ADRD varies by sex, age, and life expectancy.11 For example, an analysis in Framingham Heart Study participants found that the lifetime risk of developing ADRD at age 45 was 20% in women and 10% in men. Future research is needed to develop and validate patient-specific risk calculators for ADRD. In addition, future public health education efforts should aim to increase individuals’ understanding of lifetime risk of ADRD based on key factors such as family history. Moreover, the Lancet Commission estimated that up to one-third of cases of ADRD could be prevented by addressing modifiable risk factors over the lifetime.2 We observed a wide range of responses for estimating the preventability of ADRD, with approximately 50% reporting a response from 0% to 40%. Of note, nearly one-fourth reported that they did not know. Opportunities exist for improving the public perception of the preventability of ADRD.

Furthermore, some participants described prevention approaches not supported by evidence, such as avoiding aluminum. In addition, respondents expressed doubt about the robustness of evidence supporting dementia prevention, which may be reflective of how evidence is communicated to the public as well as the lack of evidence in this nascent area. Further qualitative and/or mixed-methods research is needed to improve understanding of the barriers and facilitators to prevention of ADRD across age groups.12

Improving the public’s understanding of modifiable risk factors for prevention of ADRD could encourage preventive health behaviors earlier in life.5 Indeed, participants in this study emphasized the value of staying current on the latest evidence and ADRD research, although some expressed confusion about the most reliable sources for this information. To have the greatest impact, it is important to know how and where this information should be targeted. Based on the results of our survey, PCPs were the most common source for information on brain health, and thus, should be equipped with up-to-date, consensus, and research based evidence on prevention of ADRD. However, given the time and resource constraints PCPs face, alternative strategies may be needed. Interdisciplinary teams, including PCPs, neuropsychologists, neurologists, and pharmacists, are ideally positioned to provide such information to patients. One strategy is to leverage the Internet,13 which most respondents accessed for information on brain health. Given the broad reach of the Internet, there is tremendous promise for online dissemination of public health communication for prevention of ADRD. For example, the Wicking Dementia Research and Education Centre at the University of Tasmania currently runs 2 Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) – Understanding Dementia and Preventing Dementia – that are free and open to the public (https://mooc.utas.edu.au/courses). Dacks et al14 recommended that Internet-based tools and decision aids could be used to communicate evidence on ADRD prevention to encourage the public to start making health choices to reduce their risk. On the other hand, the Internet can be a source of harmful or misleading information where myths are perpetuated. For example, some survey respondents reported unproven supplements as having benefits for prevention of ADRD. Future research should explore how people navigate the Internet for information on brain health and identify ways to direct them to the most appropriate resources. Additional resources on brain health are available from the Alzheimer’s Association and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) who partnered to create the Healthy Brain Initiative to address brain health from a public health perspective.15,16

Our study has several limitations. First, we used a convenience sample of adults from a single region in the US, so the results do not necessarily generalize to other populations. Our sample was more likely to be females of an older age compared to the entire KPW membership. More specifically, among the more than 617,000 KPW members as of March 2018, 54.3% were female and 40.1% were 55 years of age and older compared to our sample where most respondents were older females. Future studies should explore these concepts in more racially/ethnically diverse regions. In addition, respondents to our survey may be inherently different than those not responding, introducing potential selection bias. Second, the qualitative section of this survey was limited to participants’ comments in the “other” response option; thus, only participants who checked “other” were prompted to append free-text responses, which may have limited the diversity of responses in the sample. In addition, this was a Web-based survey so potential participants without access to a computer and the Internet were not represented in these results. Finally, we could not calculate a survey response rate because we were unable to determine how many people opened the electronic newsletter. Future studies of dementia prevention behavior should explore alternative recruitment methods such as face-to-face, mailed, or phone.17

The ultimate goal of any public health activity in this space is to reduce the burden of ADRD on society. Achieving this goal will take a multifaceted approach using key tenets learned from other public health prevention campaigns (eg, diabetes, cardiovascular disease) in this relatively new field.18 There is mounting evidence that prevention of ADRD is possible, and low-risk health choices starting in early and mid-life can help mitigate a sizable proportion of the risk. Our results indicate that knowledge about risk and preventability of ADRD can be improved, even for a well-educated group of respondents. Findings such as these could be used to improve public education campaigns on ADRD prevention. For example, the Alzheimer’s Association and the CDC partnered to create the Healthy Brain Initiative to address brain health from a public health perspective.16 The most recent version – the 2018–2023 Road Map – contains 25 actions for public health leaders to promote brain health, 2 of which focus on educating the public about cognitive aging and one that addresses educating public health professionals about the best available evidence.16 However, Anstey and Peters19 caution on the oversimplification of such public health messaging about dementia prevention. It is important to note that brain health promoting activities are also general health promoting so public health campaigns about brain health may drive people to behaviors that are of benefit for their general health. Ongoing efforts are needed to communicate the best available evidence on dementia prevention to the public and healthcare and public health professionals clearly and accurately.

Acknowledgements

ZM was supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality grant (K12HS022982). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors thank Jane McNamee for her assistance with survey deployment, Kelly Hansen for her assistance with project management, and the members of the KPW Senior Caucus for their important feedback on the initial survey.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Statement

The Institutional Review Board at the KPW Health Research Institute approved all study materials and procedures (IRB approval 1141868-8).

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors of this article declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Zachary A. Marcum, Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington, School of Pharmacy, Seattle, WA..

Sarah D. Hohl, Fred Hutch Biobehavioral Cancer Prevention & Control..

Shelly L. Gray, Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington, School of Pharmacy, Seattle, WA..

Doug Barthold, Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington, School of Pharmacy, Seattle, WA..

Paul K. Crane, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Washington, School of Medicine, Seattle, WA..

Eric B. Larson, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA..

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):367–429. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. Available at: https://www.nursing.umn.edu/sites/nursing.umn.edu/files/jan_2018_preventing_cognitive_decline_and_dementia.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf;sequence=1. Accessed December 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cations M, Radisic G, Crotty M, Laver KE. What does the general public understand about prevention and treatment of dementia? A systematic review of population-based surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0196085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Society on Aging Metlife Foundation. Attitudes and Awareness of Brain Health Poll. San Francisco, CA: American Society on Aging; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith BJ, Ali S, Quach H. Public knowledge and beliefs about dementia risk reduction: a national survey of Australians. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rimer BK, Glanz K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2005. Available at: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/theories_project/theory.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attride-Stirling J Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual Res. 2001;1(3):385–405. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tom SE, Hubbard RA, Crane PK, et al. Characterization of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in an older population: updated incidence and life expectancy with and without dementia. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):408–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson LA, Day KL, Beard RL, et al. The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the U.S. population: a national review. Gerontologist. 2009;49(Suppl 1):S3–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Connor E, Farrow M, Hatherly C. Randomized comparison of mobile and web-tools to provide dementia risk reduction education: use, engagement and participant satisfaction. JMIR Mental Health. 2014;1(1):e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dacks PA, Andrieu S, Blacker D, et al. Dementia prevention: optimizing the use of observational data for personal, clinical, and public health decision-making. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2014;1(2):117–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley M, Ulin B, McGuire LC. Reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease and maintaining brain health in an aging society. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(3):225–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alzheimer’s Association & US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy Brain Initiative road map for state and local public health partnerships. Available at: https://www.alz.org/professionals/public-health-officials/public-health-road-map. Accessed August 4, 2018.

- 17.Heerman WJ, Jackson N, Roumie CL, et al. Recruitment methods for survey research: findings from the MidSouth Clinical Data Research Network. Contemp Clin Trial. 2017;62:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell S, Ridley SH, Sancho RM, Norton M. The future of dementia risk reduction research: barriers and solutions. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(4):e275–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anstey KJ, Peters R. Oversimplification of dementia risk reduction messaging Is a threat to knowledge translation in dementia prevention research. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2018;5(1):2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]