Abstract

A sensitive multiplex PCR assay for single-tube amplification that detects simultaneous herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), human cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is reported with particular emphasis on how the method was optimized and carried out and its sensitivity was compared to previously described assays. The assay has been used on a limited number of clinical samples and must be thoroughly evaluated in the clinical context. A total of 86 cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) specimens from patients which had the clinical symptoms of encephalitis, meningitis or meningoencephalitis were included in this study. The sensitivity of the multiplex PCR was determined to be 0.01 and 0.03 50% tissue culture infective doses/the reciprocal of the highest dilution positive by PCR for HSV-1 and HSV-2 respectively, whereas for VZV, CMV and EBV, 14, 18, and 160 ag of genomic DNA were detected corresponding to 48, 66, and 840 genome copies respectively. Overall, 9 (10.3%) of the CSF samples tested were positive in the multiplex PCR. HSV-1 was detected in three patients (3.5%) with encephalitis, VZV was detected in four patients (4.6%) with meningitis, HSV-2 was detected in one neonate (1.16%), and CMV was also detected in one neonate (1.16%). None of the samples tested was positive for the EBV genome. None of the nine positive CSF samples presented herpesvirus coinfection in the central nervous system. Failure of DNA extraction or failure to remove any inhibitors of DNA amplification from CSF samples was avoided by the inclusion in the present multiplex PCR assay of α-tubulin primers. The present multiplex PCR assay detects simultaneously five different herpesviruses and sample suitability for PCR in a single amplification round of 40 cycles with an excellent sensitivity and can, therefore, provide an early, rapid, reliable noninvasive diagnostic tool allowing the application of antiviral therapy on the basis of a specific viral diagnosis. The results of this preliminary study should prompt a more exhaustive analysis of the clinical value of the present multiplex PCR assay.

Human herpesviruses, herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are ubiquitous agents causing a wide range of acute central nervous system (CNS) infections in humans. Encephalitis caused by HSV-1 or VZV has been described extensively, and most patients with HSV-1 or VZV encephalitis lack cutaneous vesicles at the onset of neurological disease (8, 16). Both primary and recurrent herpesvirus infections may lead to CNS infection and disease. Among these viruses, HSV accounts for approximately 2 to 19% of all cases of encephalitis and 20 to 75% of all cases of necrotizing encephalitis (34, 36). Herpes simplex encephalitis has a yearly incidence of one to four per million people (37) and may be associated with significant morbidity and mortality without treatment (11). Neonatal HSV encephalitis is a devastating disease most commonly occurring as a consequence of perinatal transmission of HSV-2. Life-threatening herpesvirus infections of the brain can occur throughout life. In immunocompetent patients older than 3 months, meningitis, meningoencephalitis, and myelitis are often associated with HSV-2 (2). Dual or triple infections (coinfections) due to concomitant infection of the CNS by two or three herpesviruses determined by PCR have been reported (23, 36). A clinical diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis is unreliable, as none of the presenting symptoms (fever, focal seizures, hemiparesis, and altered level of consciousness) is pathognomonic of herpes simplex encephalitis.

Early diagnosis of HSV encephalitis is important to start adequate treatment and to exclude other diseases that have a similar clinical presentation. The convincing method for diagnosis of HSV encephalitis is the isolation of virus from brain tissue obtained by biopsy (25), but in 40 to 60% of the cases, brain biopsy is an unnecessary procedure, as these patients were finally proved to be negative for HSV (9). Conventional laboratory diagnosis of CNS infections caused by human herpesviruses has not been productive. HSV is rarely recovered in cell cultures from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). A tentative diagnosis of HSV encephalitis can be performed by the demonstration of intrathecally produced anti-HSV antibodies as expressed in an increased ratio of HSV CSF and serum antibodies. By using immunoprecipitation, radioimmunoassay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and immunoblotting, several authors suggested that an increased CSF-to-serum antibody ratio is a reliable measure for the diagnosis of HSV encephalitis (5, 10, 15, 20, 26, 31). By contrast, other authors hypothesized that prolonged antigen stimulation is present in the CNS after acute HSV encephalitis and that serological measurements combined with immunoglobulin and albumin determinations provide only a tentative, not definite, diagnosis (18).

The viral antigen detection in CSF samples using indirect ELISA was proved to be not efficient enough, since the sensitivity of this assay was below that of serological methods applied to CSF (3).

The use of PCR for the diagnosis of CNS disease has been well evaluated for HSV encephalitis (11, 24, 33), and PCR is now the method of choice for herpesvirus detection. It was shown that a clinically diagnosed viral infection of the CNS was 88 times more likely to occur in a patient with a positive PCR result than in one with a negative result (13).

Usually, a series of independent, targeted PCRs in which each PCR detects a single virus is performed. In the present report, we describe a multiplex PCR assay for single-tube amplification of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV. Failure in DNA extraction procedure used or the presence of DNA amplification inhibitors are revealed by the inclusion of α-tubulin primers in the multiplex PCR assay.

In the present methods development study, we report the results of a preliminary study on a multiplex, one-round PCR assay for single-tube amplification that was performed to increase the sensitivity of this assay, compared to already published multiplex-nested PCRs (6, 30), and to evaluate the feasibility of this assay on a limited number of clinical samples, raising confidence in negative results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimens.

A total of 86 CSF from patients with clinical suspicion of HSV encephalitis, meningitis, or meningoencephalitis was included in this preliminary study. At least one CSF sample, and for some patients two consecutive CSF samples, were taken within the first 10 days following onset of neurological symptoms. None of the patients included in the study had a previous human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Twelve CSF samples collected from patients with unrelated diseases (10 had noninfectious CNS disease and 2 had autoimmune diseases) were used as negative controls. CSF samples were stored at −20°C until DNA extraction and multiplex PCR were performed.

Viruses and controls.

HSV-1 strain F, HSV-2 strain G, VZV strain Ellen, CMV strain AD169, and EBV strain P-3 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.) were used as positive controls. All but EBV were propagated in tubes in MRC-5 cells (American Type Culture Collection) grown in minimal essential medium Dulbecco's modified enriched medium (MEM-D) medium supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum and examined daily until observation of typical cytopathic effect (CPE). When 70 to 80% CPE was observed, tubes were frozen at −70°C. EBV strain P-3 was subjected to DNA extraction directly from the stock solution.

Genetically related viruses, such as HHV-8 DNA isolated from infected lymphoma cells (kindly provided by L. Arvanitakis, Hellenic Pasteur Institute), and not genetically related viruses, such as enteroviruses (poliovirus type 1, Sabin, and Mahoney strains; poliovirus type 2, Sabin, and MEF strains; poliovirus type 3, Sabin, and Saucket strains; Coxsackievirus B5 strain Faulkner; and Echovirus 30 strain Bastianni) were used in control experiments as negative controls.

DNA extraction.

HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV DNA was recovered from CSF according to the method described by Casas et al. (4), with minor modifications. Briefly, 100 μl of CSF was incubated for 10 min at room temperature with 400 μl of lysis buffer (4 M GuSCN, 0.5% N-lauroyl sarcosine, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 25 mM sodium citrate, and 40 μg of glycogen/tube). Then, 500 μl of cold isopropyl alcohol were added. The tubes were vortexed, allowed to stand for 15 min in ice, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g at 4°C. The isopropyl alcohol was removed, and the pellet was washed by addition of 1 ml of 70% ethanol. The samples were centrifuged again as above. The ethanol was removed, and the pellet was dried and dissolved in 25 μl of sterile, double-distilled water.

DNA extraction from infected cell cultures as well as from uninfected MRC-5 cells was performed using Xtreme Genomic DNA purification KIT II (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Sensitivity and specificity.

The sensitivity of the PCR was determined using serial dilutions of titrated suspensions of either HSV-1 or HSV-2 and by testing serial dilutions of VZV-, CMV-, and EBV-specific PCR products quantitated by GelPro Analyzer version 3.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.). All dilutions were prepared in pooled lymphocytic CSF and were shown to be negative for the DNA of all five herpesviruses by PCR. These CSF samples and DNA extract of uninfected MRC-5 cells were used as negative controls. A similar approach for the quantitation of PCR sensitivity has already been reported by Johnson et al. (14).

In addition, whole HSV-1 (strain McIntyre), HSV-2 (stain G), VZV (strain Rod), CMV (strain AD169), and EBV (strain B95-8) virus particles, counted by negative stain electron microscopy (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc., Columbia, Mass.), were also used in the present sensitivity and specificity assays.

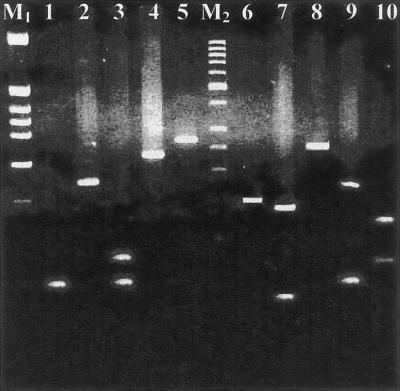

The specificity of the PCR was tested with the limiting dilution of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV viruses that yielded a clear positive result after amplification in the presence of 1 μg of DNA extract from pooled CSF samples shown to be negative for DNA of all five herpesvirus by PCR. Moreover, the specificity of each reaction and confirmation of positive results were achieved by digestion with the restriction enzymes HpaII (New England Biolabs) and Tru9I (Promega). Positive samples that gave rise to amplicons of the predicted size were excised and purified from the agarose gel with DNA-Pure gel extraction kit (CPG Inc., Lincoln Park, N.J.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. This procedure was necessary in order to avoid interference with the amplicon of α-tubulin (as α-tubulin is not digested by HpaII, but produces two bands of ∼225 and 302 bp by Tru9I). Following excision and purification of the PCR products, 10 μl of each purified product was incubated with 1.5 μl of 10× buffer, 20 U of each restriction enzyme, and double-distilled water, up to a final volume of 15 μl. The reaction mixtures were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C.

Primers.

The primer pairs could enable identical amplification efficiencies for their target sequence in a multiplex reaction. Primers with nearly identical optimum annealing temperatures should work under fairly similar conditions if they anneal with single-copy sequences. Primer concentration is a critical parameter for successful multiplex PCR. If all primers in a reaction mixture anneal with equal efficiencies, they can be used at the same concentration (21). The PCR primers were synthesized with an Applied Biosystems oligonucleotide synthesizer, and their sequences are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences—digestion of PCR amplicons as predicted by DNA sequence analysis

| Primers | Sequences (5′→3′) | Virus | Genome region amplifieda | Primer position | Length of amplimers (bp) | Tm (°C)b | Ta (°C)b | HpaII site(s) (positions)c | Tru9I site(s) (positions)g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1P32 | TGGGACACATGCCTTCTTGG | HSV-1 | RL 2 | 6621–6640 | 147 | 54 | 57 | 58, 85 | No site |

| H1M32 | ACCCTTAGTCAGACTCTGTTACTTACCC | 6741–6768 | 54 | ||||||

| EP5 | AACATTGGCAGCAGGTAAGC | EBV | Exon 4/5 terminal protein RNA | 775–794 | 182 | 50 | 51 | No site | 133 |

| EM3 | ACTTACCAAGTGTCCATAGGAGC | 935–957 | 50 | ||||||

| H2M40 | GTACAGACCTTCGGAGG | HSV-2 | UL 28 | 56320–56336 | 227 | 39 | 55 | 61, 143 | No site |

| H2P4 | CGCTTCATCATGGGC | 56533–56547 | 42 | ||||||

| CP15 | GTACACGCACGCTGGTTACC | CMV | IRL 11 | 8868–8887 | 256 | 51 | 55 | 235 | 25, 196 |

| CM3 | GTAGAAAGCCTCGACATCGC | 9105–9124 | 50 | ||||||

| VP22 | CACACGATAATGCCTGATCGG | VZV | ORF 8 | 9796–9816 | 275 | 54 | 52 | No site | 122, 200 |

| VM20 | TGCTGATATTTCCACGGTACAGC | 10049–10071 | 54 |

Primer pairs H1P32/H1M32, H2M40/H2P4, VP22/VM20, CP15/CM3, and EP5/EM3 were chosen from the DNA sequences of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV complete genomes, respectively. Sequences were accessible with the following GenBank accession numbers: X14112 for HSV-1, Z86099 for HSV-2, X04370 for VZV, X17403 for CMV, and V01555 for EBV.

Primers for α-tubulin sequences were accessible from GenBank, accession number X01703. The amplified PCR fragment was 527 bp (22).

Primer sequences were designed by Primer 3, Whitehead Institute, and elaborated by Steve Rozen and Helen J. Skaletsky in 1996 and 1997; code is available online (http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/genomesoftware/other/).

DNA amplification-multiplex PCR.

To optimize the multiplex PCR, a series of titrations of primer concentrations and deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP levels were performed. Primer concentrations of 10, 25, 50, and 100 pmol from each primer pair were titrated simultaneously with dNTP (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 mM concentrations of each of the dNTPs).

The amplification was performed with Perkin-Elmer Gene Amp PCR system 9.600. Forty amplification cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 60°C, and 50 s at 72°C were carried out in a 50-μl final volume containing 5 μl of 10× reaction buffer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), 0.2 mM concentrations of each dNTP, 10 pmol of each of the 12 primers, and 2.5 U of cloned Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). Five microliters of appropriate DNA sample (positive controls, HSV-1 strain F, HSV-2 strain G, VZV strain Ellen, CMV strain AD 169, and EBV strain P-3; negative controls, uninfected MRC-5 cells and pooled CSF samples and clinical samples) was added to the reaction mixture. After the last cycle, the samples were incubated for 15 min at 78°C to complete the extension of primers.

Ten microliters of each amplified product was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis on 3.5% agarose (NUSIEVE 3:1; FMC, Rockland, Maine) containing 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml in 1× TBE buffer and was visualized in a UV transilluminator FOTO/PHORESIS, FOTODYNE (Hartland, Wis.). Reaction mixtures digested by HpaII and Tru9I were electrophoresed as above.

Carryover contamination by the amplified products was avoided by strict physical separation of pre- and postamplification processes with general precautions against contamination, such as the use of aerosol barrier-protected pipette tips, well-separated rooms, each with its own set of micropipettes and equipment, frequent changes of gloves, and frequent decontamination of surfaces with UV light, are routinely used in our laboratory. DNA from negative controls yielded positive results only for the α-tubulin amplimer, confirming the efficiency of these preventive measures.

RESULTS

Optimization of multiplex PCR.

The selected concentration for all 12 primers was 10 pmol, as all the primers in the reaction mixture annealed with equal efficiencies when the concentration of dNTPs was 0.8 mM.

Optimal results (maximum band intensity and minimal background, nonspecific staining) were obtained with 0.8 and 1 mM dNTPs, while lower levels resulted in a decrease in the efficiency of amplification. Magnesium chloride concentration affects primer annealing and template denaturation, as well as enzyme activity and fidelity. Generally, an excess Mg2+ concentration results in accumulation of nonspecific amplification products, whereas insufficient Mg2+ concentration results in reduced yield of the desired PCR product. PCR amplification reaction mixtures should contain free Mg2+ in excess of the total dNTP concentration (an optimal free Mg2+ concentration between 0.5 and 2.5 mM) (12).

For Pfu DNA polymerase-based PCR, fidelity is optimal when the total Mg2+ concentration is ∼2 mM in a standard reaction mixture. This total Mg2+ concentration is present in the final 1× dilution of cloned Pfu DNA polymerase 10× reaction buffer (Pfu DNA polymerase, instruction manual, Stratagene).

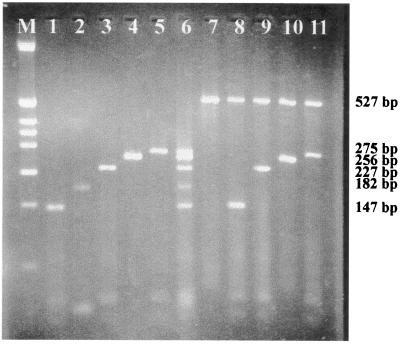

Melting temperatures (Tm) and annealing temperatures (Ta) were estimated by Primer 3 software. The estimated Tm for each primer and Ta for each couple of primers are reported in Table 1. The estimated Tm ranged from 39 to 54°C, while Ta ranged from 52 to 57°C. Increasing the annealing temperature enhances discrimination against incorrectly annealed primers and reduces misextension of incorrect nucleotides at the 3′ end of the primers. Therefore, stringent annealing temperatures will help to increase specificity (12). The annealing temperature (60°C) was chosen to be as high as possible, taking care not to reduce the sensitivity of the assay. The choice of a hybridization temperature of 60°C avoided parasite bands while maintaining a normal amplification rate (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 11).

FIG. 1.

Specificity of the multiplex PCR to detect HSV-1, EBV, HSV-2, CMV, and VZV. Detection and typing of clinical isolates by multiplex PCR. Amplification was performed with 0.8 mM dNTPs. All primer pairs were used at the concentration of 10 pmol. Amplification conditions were as follows: 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 40 s at 60°C, and 50 s at 72°C. The amplified products were subjected to a 3.5% agarose gel electrophoresis containing 1 μg of ethidium bromide/ml in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. Lane M, molecular weight markers corresponding to a HinfI digest of pBR322 DNA (Minotech, Crete, Greece). Shown in lanes 1 to 5 are amplifications performed on 10 log PCRD50 of HSV-1/ml, 160 ag of EBV, 7 log PCRD50 of HSV-2/ml, 18 ag of CMV, and 14 ag of VZV in the presence of 1 μg DNA of pooled CSF samples. Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, amplifications with primer pairs H1P32/H1M32, EP5/EM3, H2M40/H2P4, CP15/CM3, and VP22/VM20, respectively; lane 6, positive multiplex PCR amplification with the five sets of primers of the above five herpesviruses (product size marker used in the screening of the clinical specimens). Shown in lanes 7 to 11 are amplifications performed with α-tubulin primers and the above set of five primers on clinical samples. Lane 7, negative CSF sample; lanes 8, 9, 10, and 11, CSF samples containing HSV-1, HSV-2, CMV, and VZV, respectively. The predicted size of each amplimer is shown on the right.

Sensitivity and specificity of multiplex PCR assay.

The sensitivity of the multiplex PCR was determined using serial dilutions of infected tissue culture supernatants of predetermined 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s) for HSV-1 and HSV-2. The reciprocal of the highest dilution positive by PCR adjusted to concentration per milliliter after DNA extraction was defined as PCRD50/ml. The sensitivity of the multiplex PCR for VZV, EBV, and CMV was determined by testing serial dilutions of quantitated PCR products. All dilutions were prepared in lymphocytic CSF shown to be negative for all five herpesviruses (HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV) by PCR. Following agarose gel electrophoresis, the minimal amounts of HSV-1 and HSV-2 detectable were 10 and 7 log PCRD50/ml, respectively. For VZV, EBV, and CMV, genomic DNA was detected at 14, 160, and 18 ag, respectively (Table 2). The corresponding sensitivity in DNA copies was 48, 66, and 840 genome copies for VZV, CMV and EBV respectively. The sensitivity was also assayed by 10-fold dilutions of active virus particles of HSV-1 (stain McIntyre), HSV-2 (strain G), VZV (strain Rod), CMV (strain AD169), and EBV (strain B95-8) counted by negative stain electron microscopy (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc.), prior to DNA extraction. The limiting sensitivities measured were 52, 213, 90, 260, and 600 virus particles for HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity of multiplex PCR for detection of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV

| Virus | Log infectivity (TCID50/ml)a | Log PCRD50/mlb | TCID50/ PCRD50 | Serial dilutions of quantitated PCR products (corresponding genome copies) | No. of active virus particlesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSV-1 | 8 | 10 | 0.01 | 52 | |

| HSV-2 | 5.5 | 7 | 0.03 | 213 | |

| VZV | 14 ag (48) | 90 | |||

| CMV | 18 ag (66) | 260 | |||

| EBV | 160 ag (840) | 600 |

TCID50, TCID at which 50% of inoculated monolayers become infected.

The reciprocal of the highest dilution positive by PCR adjusted to concentration per milliliter after DNA extraction.

Active virus particles counted by negative stain electron microscopy prior to DNA extraction.

The specificity of the multiplex PCR protocol for HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, EBV, and CMV was demonstrated by amplicons of the predicted sizes of 147, 227, 275, 180, and 256 bp, respectively. In control experiments, the oligonucleotides designed, for example, for the amplification of HSV-1 were shown to be specific for HSV-1 and did not amplify the other four herpesviruses (HSV-2, VZV, EBV, and CMV). The specificity of each primer pair was evaluated further against the four other herpesviruses tested in the presence of 1 μg of DNA extract from negative pooled CSF samples (Fig. 1, lanes 1 to 5). During the control experiments, all five primer pairs designed for the specific amplification of each of the five herpesviruses were mixed and used for the amplification of related (human herpesvirus 8) or unrelated viruses (enteroviruses). The mixture of these primer pairs did not amplify any of the above viruses (data not shown).

Potential presence of inhibiting factors in CSF.

The diagnostic value of CSF PCR may be compromised by the presence of inhibitors, and PCR may potentially lead to false-negative results. Elevated CSF protein levels that are observed in acute encephalitis may contribute to this inhibitory effect (28). In the present assay, the inclusion of α-tubulin primers permitted the detection of occasional false-negative results. Thus, failure in the DNA extraction procedure or the presence of DNA amplification inhibitors is easily detected (22).

Six of the 86 CSF samples tested were negative with all primers used. The lack of PCR products visible on the gel was taken as being indicative of the presence of inhibitors or of failure in DNA extraction procedure, in the corresponding CSF samples. Failure in the DNA extraction procedure, or the presence of DNA amplification inhibitors, is detected by the lack of PCR product for α-tubulin primers. Inhibition or failure in DNA extraction was removed in all six samples following extraction of another aliquot diluted 1/5 in distilled water prior to DNA extraction.

Multiplex PCR analysis of CSF samples.

The presence of the HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV genomes was investigated by multiplex PCR in a total of 86 CSF specimens. These samples were sent to our laboratory for routine diagnostic purposes.

Overall, nine (10.3%) of the CSF samples tested were positive in the multiplex PCR. HSV-1 was detected in three patients (3.5%) with encephalitis, VZV was detected in four patients (4.6%) with meningitis, HSV-2 was detected in one neonate (1.16%), and CMV was detected in one neonate too (1.16%).

None of the samples tested was positive for EBV genome. From the nine positive CSF samples, none presented herpesvirus coinfection in the CNS (Table 3; Fig. 1, lanes 7 to 11). All the samples that gave rise to amplicons of the predicted size were excised, purified from the agarose gel, and subjected to digestion with restriction enzymes HpaII and Tru9I. The restriction patterns were always those predicted by DNA sequence analysis (Table 1; Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Detection of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV genomes by multiplex PCR in 86 CSF samples

| Result | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | VZV | CMV | EBV | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. negative (%) | 83 (96.5) | 85 (98.9) | 82 (95.4) | 85 (98.9) | 86 (100) | 77 (89.7) |

| No. positive (%) | 3 (3.5) | 1 (1.1) | 4 (4.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 9 (10.3) |

| Total | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | 86 (100) | 86 (100) |

FIG. 2.

Restriction enzyme digestion pattern for HSV-1, EBV, HSV-2, CMV, and VZV by HpaII (lanes 1 to 5) and Tru9I (lanes 6 to 10). Lane M1, molecular weight marker, corresponding to a HinfI digest of pBR322 DNA (Minotech, Crete, Greece); lane M2, molecular weight marker, 50-bp DNA ladder (MBI, Vilnius, Lithuania). Fragments smaller than 30 bp are not visible on the ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. Lane 1, HSV-1 digest (58- and 62-bp fragments; the 27-bp fragment is not visible); lane 2, EBV, no digestion; lane 3, HSV-2 digest (61-, 82-, and 84-bp fragments); lane 4, CMV digest (235-bp fragment; the 21-bp fragment is not visible); lane 5, VZV, no digestion; lane 6, HSV-1, no digestion; lane 7, EBV digest (49- and 133-bp fragments); lane 8, HSV-2, no digestion; lane 9, CMV digest (60- and 171-bp fragments; the 25-bp fragment is not visible); lane 10, VZV digest (75-, 78-, and 122-bp fragments).

DISCUSSION

The detection of CNS infections by PCR has provided a new tool of laboratory diagnosis compared to conventional techniques of cell culture and serology. Target genes of organisms responsible for CNS infections are generally present early in the acute phase of the disease; in contrast, CSF samples from patients without an infectious etiology do not contain these nucleic acid sequences (1). PCR was evaluated in a large series of patients with biopsy-proven herpes simplex encephalitis, and 98% sensitivity was achieved using a single-round PCR protocol (19). Thus, the relevance of PCR for the early diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis was established when a therapeutic decision is urgent.

The present multiplex PCR assay was developed to allow simultaneous detection and typing of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV DNA within the same tube. Particular emphasis was given to how the method was optimized and carried out. In addition, as the detection of these viruses is performed with a single nucleic acid extraction and amplification conditions, it is convenient and cost-effective for use on a routine basis. The limited clinical data in this study are used to show that the assay may be implemented as a routine diagnostic test. The results of this preliminary study should prompt a more exhaustive analysis of the clinical value of the present multiplex PCR assay.

A sensitive assay was established by careful choice of primers and adjustment of dNTP and primer concentrations. The rather high number of 40 cycles was chosen to drive PCR into the linear phase of amplification, when the amount of primers or enzyme became limiting. In each PCR amplification, 2.5 U of cloned Pfu DNA polymerase were used. The advantage was that it provided adequate enzymatic activity when one DNA amplification was less efficient than another in a simultaneous reaction. The annealing temperature was chosen to be as high as possible (60°C), taking care not to reduce the sensitivity of the assay.

The sensitivity of detection of each of the viral nucleic acids was equivalent by each single primer pair and by multiplex primer pair reactions. The multiplex PCR has a high molecular sensitivity for all five herpesviruses detected in the present assay. For HSV-1 and HSV-2, log TCID50/ml values were 8 and 10, respectively, and log PCRD50/ml values were 5.5 and 7, respectively. Thus, the present multiplex PCR assay has a higher molecular sensitivity than those reported by Cassinoti et al. (6) (0.003 and 0.3 TCID50 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively), while the sensitivity is 30-fold greater than those reported by Read and Kurtz (30) for HSV-1 (TCID50/PCRD50 of 0.3 instead of 0.01; Table 2). A potential difficulty in making such a comparison is the lack of well-validated standard materials for such comparisons. TCID50 is a semiquantitative estimate of the infectivity. By titration of this material in PCR (PCRD50), a detection limit of 0.01 and 0.03 TCID50/PCRD50 for HSV-1 and HSV-2, respectively, was achieved. The problem with such an approach is that the infectivity of a virus preparation may not be an accurate indication of the number of viral genomes in a preparation (i.e., there may be significant numbers of non-infectious particles). To properly compare the assays, the same batch of material would need to be tested in all three assays. For VZV, CMV, and EBV, the sensitivity of the assay was of 14, 18, and 160 ag, or 48, 66, and 840 genome copies, respectively. In addition, the present assay has the considerable advantage that it is a single-round multiplex PCR, while Cassinoti et al. (6) and Read and Kurtz (30) performed two-round PCRs of 35 and 15 cycles for the first round and of 33 cycles for each round, respectively, exposing the assay to potential carryover contamination.

Quality controls are of crucial importance to monitor the potential occurrence of false-positive as well as false-negative PCR results. Potential contaminations leading to false-positive results were monitored by submitting negative controls to the whole PCR process, including DNA extraction. Occasional negative PCR results were observed for patients with proven herpes simplex encephalitis (19, 27) raise an important problem; the competence of each sample for PCR amplification. It is well known that CSF may contain inhibitors that can partially or completely block DNA polymerase activity and cause false negative results. Due to the clinical and therapeutic implications of a false-negative PCR result, identification of inhibited PCRs is a priority. Therefore, when PCR is employed for diagnostic purposes, it is imperative to adopt adequate controls for assessing sample suitability for PCR. In the present multiplex PCR assay, occasional false-negative results for herpesvirus DNA amplification could lead to unidentifiable false-negative results if α-tubulin primers were not included in the assay. Thus, failure of DNA extraction or failure to remove any inhibitors of DNA amplification may be avoided by the present assay. In routine practice, failure of DNA extraction or the presence of inhibitors was subsequently assessed by testing a distinct aliquot of each of the six CSF samples diluted 1/5 in distilled water prior to DNA extraction.

In the present study, we investigated a PCR-based DNA amplification technique for detecting herpesvirus DNA in the CSF samples of patients manifesting symptoms of viral encephalitis. The CSF samples evaluated in our study were from patient populations with CNS disease not associated with HIV infection. Coinfection was not detected. Detection of more than one virus from any clinical specimen is uncommon. Moreover, documented reports of viral coinfections in CNS diseases in immunocompetent patients determined by PCR have also been uncommon (29). The diagnostic procedure which was elaborated during the present study allowed the rapid detection of herpesvirus DNA in patients with the symptoms of encephalitis or meningitis. All patients were subsequently treated with acyclovir for 14 days (30 mg/kg of body weight/day, given intravenously). Four of the nine herpes virus-positive patients (Table 3) were clinically diagnosed with meningitis (detection of VZV DNA in CSF), and they had a full recovery. Three patients presented the clinical symptoms of encephalitis (detection of HSV-1 DNA in CSF); two of them recovered and the third one had neurological sequelae during a 6-month follow-up. The two neonates (detection of HSV-2 or CMV DNA in respective CSF samples) recovered with mild to moderate sequelae. Conventional virologic laboratory diagnosis (cell culture) of these CNS infections was not productive. All CSF samples were inoculated into MRC-5 and Vero cells and were followed for at least 8 days. Early CSF samples showed mild to moderate pleocytosis ranging from 20 to 400 cells/mm3 and consisted mainly of mononuclear cells. Protein content was either normal (<0.5g/liter), or increased up to 2 g/liter. In ELISAs, all nine patients showed serological evidence of the corresponding CNS infection by one of the VZV, HSV-1, HSV-2, or CMV viruses (high titers of anti-immunoglobulin G [IgG] antibodies to VZV, or HSV-1 and detection of anti-IgM antibodies to HSV-2, or CMV). The multiplex PCR assay described appears to be reliable for use with clinical samples. It has been shown to be appropriate for the early and type-specific detection of HSV-1, HSV-2, VZV, CMV, and EBV genomes in patients with suspected CNS infection. This assay has many advantages over other types of laboratory tests including single target PCR or multiplex nested PCR as has already been discussed. It detects simultaneously five different herpesviruses and sample suitability for PCR in a single amplification round of 40 cycles. There are clear advantages to a method that involves only one reaction: less sample material, reagents, and time are required.

In conclusion, the multiplex PCR assay presented in this study can provide an early, rapid, reliable noninvasive diagnostic tool allowing antiviral therapy to be initiated on the grounds of a specific viral diagnosis. The clinical features of neurological disease due to non-polio enteroviruses can overlap those caused by herpesviruses. There may be unnecessary hospitalization and anti-herpetic therapy may, therefore, be initiated for patients with mild enterovirus infection (32). However, additional studies are required in order to evaluate the present assay with a greater number of CSF specimens in the clinical context by testing it against well-defined specimens that have been thoroughly characterized by other methods and, finally, in order to assess its clinical significance and its utility in monitoring the efficacy of treatment with antiviral drugs. Such a study should be the subject of a subsequent submission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by a research grant from the “Délégation Générale au Réseau International des Instituts Pasteur et Instituts Associés—ACIP maladies émergentes.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Aslanzadeh J, Osmon D R, Wilhelm M P, Espy M J, Smith T F. A prospective study of the polymerase chain reaction for selection of herpes simplex virus in cerebrospinal fluid submitted to the clinical virology laboratory. Mol Cell Probes. 1992;6:367–373. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(92)90029-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aurelius E. Herpes simplex encephalitis—early diagnosis and immune activation in the acute stage and during long-term follow up. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1993;89:3–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos C A, Olding-Stenkvist E, Wilterdink J B, Scheffer A. Detection of viral antigens in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Med Virol. 1987;21:169–178. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890210209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casas I, Powell L, Klapper P E, Cleator G M. New method for the extraction of viral RNA and DNA from cerebrospinal fluid for use in the polymerase chain reaction assay. J Virol Methods. 1995;53:25–36. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)00173-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casas I, Tenorio A, de Ory F, Lozano A, Echevarria J M. Detection of both herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with encephalitis. J Med Virol. 1996;50:82–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199609)50:1<82::AID-JMV14>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassinotti P, Mietz H, Siegl G. Suitability and clinical application of a multiplex nested PCR assay for the diagnosis of herpes simplex virus infections. J Med Virol. 1996;50:75–81. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199609)50:1<75::AID-JMV13>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry J D. Enteroviruses. The forgotten viruses of the 80's. In: de la Maza L M, Peterson E M, editors. Medical virology. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1988. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Echevarria J M, Casas I, Tenorio A, de Ory F, Martinez-Martin P. Detection of varicella-zoster virus-specific DNA sequences in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with acute aseptic meningitis and no cutaneous lesions. J Med Virol. 1994;43:331–335. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felgenhauer K, Ackermann R. Early diagnosis and treatment of herpes simplex encephalitis. J Neurol. 1985;232:123–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00313915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forsgren M, Sköldenberg B, Jeansson S, Grandien M, Blomberg J, Juto P, Berström T, Olding-Stenkvist E. Serodiagnosis of herpes encephalitis by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: experience from Swedish antiviral trial. Ser Immun Infect Dis. 1989;3:259–271. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guffond T, Dewilde A, Lobert P E, Lefebre D C, Hober D, Wattre P. Significance and clinical relevance of the detection of herpes simplex virus DNA by the polymerase chain reaction in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with presumed encephalitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:744–749. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J. Optimization of PCRs. In: Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T I, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffery K J, Read S J, Peto T E, Mayon-White R T, Bangham C R M. Diagnosis of viral infections of the central nervous system: clinical interpretation of the PCR results. Lancet. 1997;349:313–317. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson G, Nelson S, Petric M, Tellier R. Comprehensive PCR-based assay for detection and species identification of human herpesviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3274–3279. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3274-3279.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klapper P E, Laing I, Longson M. Rapid non invasive diagnosis of herpes encephalitis. Lancet. 1981;ii:607–608. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klapper P E, Cleator G M. The diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis. Rev Med Microbiol. 1992;3:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klapper P E, Cleator G M. Herpes simplex virus. Intervirology. 1997;40:62–71. doi: 10.1159/000150534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koskiniemi M L, Vaheri A. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid antibodies in herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych. 1982;45:239–242. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.45.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lakeman F D, Whitley R J. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis: application of polymerase chain reaction to cerebrospinal fluid from brain-biopsied patients and correlation with disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:857–863. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markoulatos P, Labropoulou V, Kordossi A, Krikelis V, Spyrou N, Moncany M. A combined indirect Elisa and immunoblotting for the detection of intrathecal herpes simplex virus IgG antibody synthesis in patients with herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Clin Lab Anal. 1995;9:325–333. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860090508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markoulatos P, Samara V, Siafakas N, Plakokefalos E, Spyrou N, Moncany M. Development of a quadriplex polymerase chain reaction for human cytomegalovirus detection. J Clin Lab Anal. 1999;13:99–105. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1999)13:3<99::AID-JCLA2>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Markoulatos P, Mangana-Vougiouka O, Koptopoulos G, Nomikou K, Papadopoulos O. Detection of sheep poxvirus in skin biopsy samples by a multiplex polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 2000;84:161–167. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(99)00141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mingolie S, Michelet C, Jusselin I, Joannes M, Cartier F, Colimon R. Amplification of the six major human herpesviruses from cerebrospinal fluid by a single PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;37:950–953. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.950-953.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell P S, Espy M J, Smith T F, Toal D R, Rys P N, Berbari E F, Osmon D R, Persing O H. Laboratory diagnosis of central nervous system infections with herpes simplex virus by PCR performed with cerebrospinal fluid specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2873–2877. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2873-2877.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morawetz R B, Whitley R J, Murphy D M. Experience with brain biopsy for suspected herpes encephalitis: A review of forty consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 1983;12:654–657. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198306000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauli G, Ludwig H. Immunoprecipitation of herpes simplex virus type 1 antigens with different antisera and human cerebrospinal fluids. Arch Virol. 1977;53:139–155. doi: 10.1007/BF01314855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puchhammer-Stöckl E, Heinze F X, Kundi M, Popow-Kraupp T, Grimm G, Millner M M, Kunz C. Evaluation of the polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:146–148. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.1.146-148.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ratnamohan V M, Cunningham A L, Rawlinson W D. Removal of inhibitors of CSF-PCR to improve diagnosis of herpesviral encephalitis. J Virol Methods. 1998;72:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read S J, Jeffery K J M, Bangham C R M. Aseptic meningitis and encephalitis: the role of PCR in the diagnostic laboratory. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:691–696. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.691-696.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Read S J, Kurtz J B. Laboratory diagnosis of common viral infections of the central nervous system by using a single multiplex PCR screening assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1352–1355. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1352-1355.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberg M, Forsberg P, Tegnell A, Ekerfeldt K. Intrathecal production of specific IgA antibodies in central nervous system infections. J Neurol. 1995;242:390–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00868395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rotbart H A. Nucleic acid detection systems for enteroviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:156–158. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rozenberg F, Lebon P. Amplification and characterization of herpesvirus DNA in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with acute encephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;35:2869–2872. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2412-2417.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skoldenerg B, Forsgren M, Alestig K, Bergstrom T, Burman L, Dahlqvist E, Forkman A, Fryden A, Lovgren K, Norlin K. Acyclovir versus vidarabine in herpes simplex encephalitis: randomized multicentre study in consecutive Swedish patients. Lancet. 1984;ii:707–711. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studahl M, Richsten A, Sandberg T, Elowson S, Herner S, Sall C, Bergstrom T. Cytomegalovirus infection of the CNS in non-compromised patients. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitley R J, Alford C A, Hirsch M S, Schooley R T, Luby J P, Aoki F Y, Hanley D F, Nahmias A J, Soong S J. Vibaradine versus acyclovir therapy in herpes simplex virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:144–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198601163140303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whitley R J, Lakeman F. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:414–420. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.2.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]