Abstract

Objective: This study is a secondary analysis of data collected in an earlier clinical trial of mindfulness-based resilience training (MBRT) (ClinicalTrials.gov registration number 02521454), where the MBRT condition demonstrated a significant reduction in self-reported burnout and trend-level reductions in alcohol use in law enforcement officers (LEOs). Given that MBRT is not designed to be a substance use intervention and does not contain explicit substance-related content, this study sought to clarify these findings by exploring whether improved burnout mediates reduced alcohol use.

Method: Participants (n = 61) were sworn LEOs (89% male, 85% White, 8% Hispanic/Latinx) recruited from departments in a large urban metro area of the northwestern United States, and were randomized to either MBRT (n = 31) or no intervention control group (n = 30) during the trial.

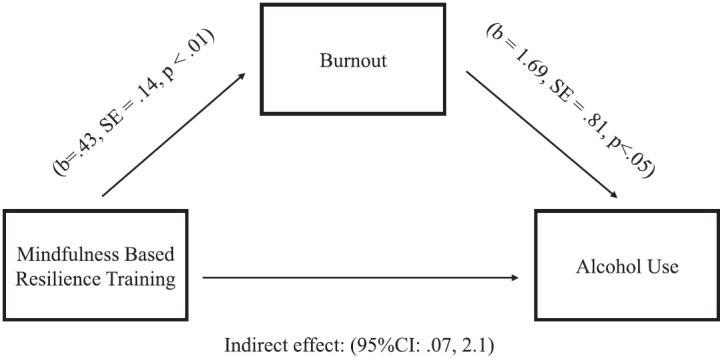

Results: MBRT group assignment predicted reduced burnout (b = 0.43, standard error [SE] = 0.14, p = 0.004), which subsequently predicted reduced alcohol use (b = 1.69, SE = 0.81, p = 0.045). Results suggest that reduced alcohol use was indirectly related to a reduction in burnout post-MBRT.

Conclusion: Given that MBRT does not explicitly address substance use, these findings were interpreted to suggest that officers in the training acquired a new set of coping skills to deal with the operational and organizational stressors of police work.

Keywords: burnout, mindfulness, law enforcement officers, alcohol use

Introduction

Law enforcement officers (LEOs), widely considered to be employed in one of the most stressful occupations,1 are at an elevated risk for a wide variety of negative health implications. Research shows increased mental1,2 and physical risk factors,2–4 including maladaptive coping skills, higher suicidal ideation, and increased sickness.1,4,5 In particular, LEOs are at greater risk for burnout relative to most other professions.5,6 Burnout is a psychological condition characterized by emotional exhaustion, reduced feelings of personal accomplishment, and depersonalization resulting from chronic work-related stress.7 In the context of burnout, depersonalization appears as a distorted view of oneself and their environment, and often presents as a lack of empathy.8 LEOs experiencing burnout are more likely to display aggression9 and demonstrate impaired ethical decision making10 and disrupted problem solving.11 LEOs appear to use alcohol as a coping strategy to manage negative outcomes of their occupation, including burnout.12

Although multiple studies have found that LEOs engage in elevated rates of overall and high-risk alcohol consumption relative to the general population,13,14 others have found LEOs did not use more alcohol than the general population, but do engage in more binge drinking behavior.15 Other studies have found that one in three LEOs reported at least one recent binge drinking episode in the past 30 days.13,16 Alcohol use among LEOs is positively associated with job stress, dissatisfaction,17 critical incident exposure,18 and post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).19 Elements of law enforcement culture, such as drinking to fit in or bond with coworkers, appear to encourage drinking as a strategy for coping with job-related stress and burnout.20

Burnout among LEOs is related to negative health outcomes such as hypertension,21 depressive22,23 and anxiety disorders,22 and suicide.24 LEOs experiencing burnout are also at risk for negative behavioral effects, such as increased aggression,9,25 impaired decision making,10 impaired problem solving,11 administrative and tactical errors, and absenteeism.9 Burnout is also associated with increased alcohol consumption in high-stress occupations, including medical professions,26,27 transit operators,28 prison employees,29 and LEOs.17 Studies have also demonstrated that burnout is a predictor of frequency and quantity of alcohol consumed in ambulance workers,30 U.S. medical students,31 and correctional officers.32

Despite the significant need, existing wellness interventions for LEOs appear insufficient. In a meta-analysis, Patterson et al.33(p508) concluded that “insufficient evidence exists to demonstrate the effectiveness of stress management interventions for reducing negative physiological, psychological or behavioral outcomes among LEOs and recruits.” Recently, mindfulness-based resilience training (MBRT) has emerged as a novel treatment approach to address the pressing need of effective interventions for LEOs.34 MBRT provides formal and informal mindfulness training specifically tailored to the needs and culture of the law enforcement community and has demonstrated feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness in clinical trials.34,35 Further research found reduced perceived stress, sleep disturbances, anxiety, burnout, and PTSD symptoms in LEOs after completion of MBRT.36

Delivered over 8 weekly sessions, MBRT provides participants with strategies for coping with stressors inherent in policing. As with other mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), over the course of the intervention, meditation training allows participants to increase awareness of automatic cognitive, affective, and behavioral patterns that tend to interact automatically and subconsciously. For example, external job stressors could trigger excessive negative rumination that leads to negative affective states, states that can be abated by engaging in an external behavior, such as aggression or alcohol use. As this pattern plays out over the course of a career in law enforcement, negative consequences readily accrue and manifest in burnout. In MBIs such as MBRT, the experiences and interventions increase awareness of these processes that then provide the opportunity for more agency in individuals' response to internal and external stimuli, both positive and negative. This theoretical model appears to be supported by preliminary data. Officers randomized to MBRT demonstrated significant reductions in burnout and trend-level reductions in alcohol use,35 though a larger sample size would have increased the likelihood of a significant reduction. This is somewhat striking, given that MBRT does not involve any explicit interventions for reducing substance use. In attempt to explain this spontaneous reduction in alcohol use among officers receiving MBRT, consistent with the theoretical model of MBIs, the purpose of this study is to assess whether improvement in burnout mediates the impact of MBRT on reduced alcohol use.

Methods

Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected in an earlier clinical trial of MBRT,35 which was approved by the Pacific University IRB and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, registration number 02521454. Participants (n = 61) were sworn LEOs recruited from departments in a large urban metro area of the northwestern United States (see Table 1 for participant demographics).

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| MBRT |

NIC |

X2/t/F | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or mean | % | n or mean | % | |||

| n | 31 | — | 30 | — | ||

| Age (SD) | 44.73 (6.63) | — | 43.22 (5.43) | — | t = 0.98 | 0.17 |

| Gender | X2 = 0.20 | 0.65 | ||||

| Female | 3 | 10% | 4 | 10% | ||

| Male | 28 | 90% | 26 | 90% | ||

| Race | X2 = 5.06 | 0.54 | ||||

| White | 27 | 88% | 25 | 84% | ||

| Black | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific | 1 | 3% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Native American/Alaskan | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Asian | 1 | 3% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Multiracial | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Other | 0 | 0% | 2 | 7% | ||

| Ethnicity | X2 = 2.07 | 0.15 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 | 3% | 4 | 13% | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 30 | 97% | 26 | 87% | ||

| Years of education (SD) | 15.89 (2.37) | — | 14.75 (2.35) | — | t = 1.59 | 0.14 |

| Years on the job (SD) | 18.50 (6.98) | — | 17.97 (6.69) | — | t = 0.30 | 0.38 |

| Relationship status | X2 = 7.74 | 0.17 | ||||

| Married | 23 | 74% | 25 | 83% | ||

| Divorced | 4 | 13% | 2 | 7% | ||

| Widowed | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Cohabitating | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Single | 3 | 10% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Rank | X2 = 11.90 | 0.16 | ||||

| Officer | 9 | 29% | 4 | 13% | ||

| Deputy | 3 | 10% | 5 | 17% | ||

| Criminalist | 0 | 0% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Detective | 3 | 10% | 6 | 20% | ||

| Sergeant | 6 | 19% | 10 | 33% | ||

| Lieutenant | 3 | 10% | 5 | 17% | ||

| Commander | 1 | 3% | 1 | 3% | ||

| Captain | 4 | 13% | 0 | 0% | ||

| Other | 2 | 6% | 0 | 0% | ||

MBRT, mindfulness-based resilience training; NIC, no intervention control; SD, standard deviation.

Procedures

Participants were recruited using several methods. Recruitment emails with study information and attached informational flyers were sent to police department chiefs in the region where the study was conducted. Research team members also presented study information to groups of LEOs at a number of police departments during recruitment sessions. To be eligible for study participation, interested individuals had to be a full-time sworn LEO with no exposure to MBRT or a similar mindfulness course. Those meeting criteria were scheduled for a pretraining assessment appointment, where they provided written informed consent and completed all measures through computer. LEOs were subsequently randomly assigned, by research team members using computer-generated permuted-block randomization (1:1 ratio) with stratification (gender and age), to MBRT (n = 31) or no intervention control (NIC; n = 30). Beginning April 2016, two MBRT groups were conducted, and NIC participants were offered the training at no charge after the final follow-up assessment (October 2016). Participants completed a similar computer-administered battery of measures post-training and at 3-month follow-up (January 2017).

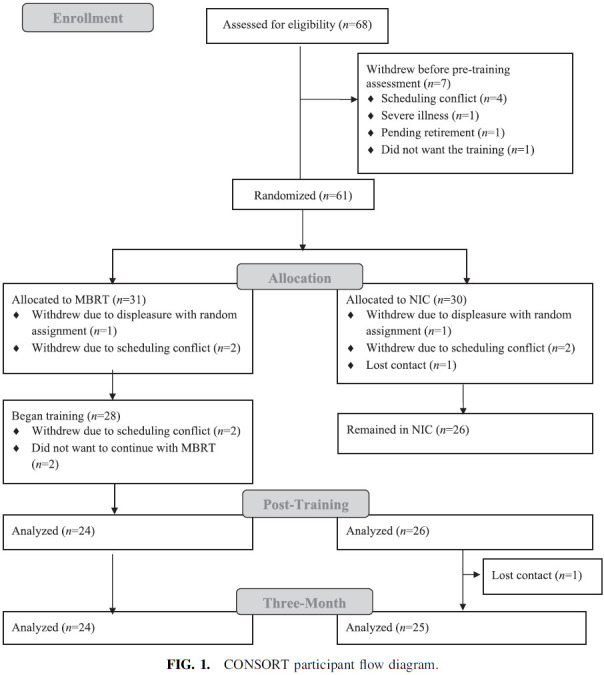

The MBRT curriculum was adapted from the mindfulness-based stress reduction framework and was designed to enhance law enforcement resilience in the context of acute and chronic stressors inherent to policing. The intervention was delivered in 8 weeks with 2-hour weekly sessions and an extended 6-hour class in the seventh week of class. Training activities included both experiential and didactic exercises including body scan, sitting and walking meditations, mindful movement, and group discussion. Both content and language of the training were adapted to fit law enforcement population. During the intervention, 11 participants withdrew from the study, resulting in 50 participants completing postcourse assessment measures (MBRT = 24; NIC = 26) (see Fig. 1 for CONSORT flow diagram).

FIG. 1.

CONSORT participant flow diagram.

Measures

Burnout was measured by the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory,37 a 16-item self-report measure that assesses exhaustion and disengagement from work and demonstrated acceptable internal consistency in the present sample (αpre = 0.73; αpost = 0.76).

Alcohol use was measured by the Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; v1.0) short form, a 7-item self-report measure of drinking patterns (e.g., quantity and frequency of consumption, time spent drinking, and episodes of heavy drinking), cue-based drinking (internal states and external contexts), cravings to drink (e.g., urgency and compulsivity), and efforts to control drinking (e.g., difficulty in limiting drinking), indicative of problematic drinking. Participants are first asked to answer a screener question about whether they have consumed any type of alcoholic beverage in the past 30 days. Those who endorse in the affirmative complete the remainder of the PROMIS items, whereas those who respond in the negative do not finish these items, moving on to the next measure in the assessment battery. Only those endorsing consumption of alcohol in the past 30 days at baseline and postcourse were used in the analysis for this study, where at baseline, 50 participants responded in the affirmative to the screener question (MBRT = 26; NIC = 24) and 11 participants responded in the negative (MBRT = 5; NIC = 6). At postcourse, 41 participants responded in the affirmative (MBRT = 20; NIC = 21) and 9 participants denied consuming alcohol in the past 30 days (MBRT = 4; NIC = 5), resulting in a total sample of 39 used in this study. The PROMIS demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the present sample (αpre = 0.94; αpost = 0.94).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SPSS statistics version 24. A repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess pre- to post-MBRT change across groups (MBRT v. NIC) on the PROMIS alcohol use. For the mediation analysis, burnout and alcohol use at postcourse were regressed on the same variable at the beginning of the course with saved standardized residuals used to create a residualized change score. This method for measuring change has been used in previous research of MBIs38 and corrects for statistical regression toward the mean.

Model 4 of PROCESS macro39 was used to test whether the association between treatment condition and alcohol use was mediated by improvement in burnout. Nonparametric bias-corrected bootstrapping with 10,000 resamples was used to test the statistical significance of the indirect effect of treatment condition on alcohol use through burnout,40 where a 95% confidence interval (CI) not containing 0 is thought to provide evidence of mediation (indirect effect).

Results

Repeated measures ANOVA results revealed a significant group-by-time interaction, whereby PROMIS alcohol use scores decreased over time in the MBRT group (Mpre = 46.94, standard deviation [SD] = 7.89; Mpost = 44.31, SD = 6.34) but not in the NIC group (Mpre = 46.88, SD = 8.24; Mpost = 47.29, SD = 8.72), p = 0.04. Mediation analyses revealed that the indirect effect of treatment condition on alcohol use through burnout was significant. Figure 2 shows the unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% CI of each path in the model. MBRT group assignment predicted reduced burnout (b = 0.43, standard error [SE] = 0.14, p = 0.004), which subsequently predicted reduced alcohol use (b = 1.69, SE = 0.81, p = 0.045). The bootstrapped CI of the indirect effect did not contain 0 (95% CI: 0.07, 2.1), providing evidence for mediation. There were no adverse events reported in either group during the parent study.

FIG. 2.

Results of the mediation model. Unstandardized regression coefficients depicting indirect effect of treatment condition on alcohol use through burnout.

Discussion

Burnout is a well-documented negative occupational consequence among LEOs, who commonly endorse alcohol use as a coping strategy, placing them at a greater risk for developing use disorders relative to the public at large.19 LEOs demonstrated significant reductions in self-reported burnout and trend-level reductions in alcohol use in a recent trial of MBRT,35 which this study sought to clarify, by exploring potential mediating factors.

The findings suggest that reduced alcohol use was indirectly related to reduced burnout post-MBRT. Given that MBRT does not explicitly address substance use, these findings were interpreted to suggest that MBRT participants acquired a new set of coping skills to deal with the factors perpetuating burnout in police work. As burnout reduced over the training, it is possible that officers became less reliant on alcohol use to cope and to regulate activation as they developed positive coping strategies related to mindfulness and resilience skills learned in MBRT. The use of alcohol to cope can be conceptualized as a strategy to avoid to regulate negative emotions,41,42 which is predictive of burnout.43,44 Lacking more adaptive coping skills, along with elements of police culture that appears to promote drinking as a way to “destress,”20 propagates the use of drinking as a coping mechanism.45,46 It may be that police officers were able to employ newly acquired MBRT skills to cope with burnout instead of relying on alcohol. This is consistent with the content of MBRT, the spontaneous nature of alcohol use reduction, and the “drinking to cope” hypothesis.41 As LEOs increase application of the mindfulness skills learned over the course, in addition to some explicit course content on burnout and related topics, it is possible that the perceived experience of burnout reduces the need to cope through alcohol use. If MBRT contained explicit content and focus on substance use, it may be that the reductions in alcohol mediated reductions in burnout. However, given the absence of specific content and hypothesized temporal relationship between the variables lends evidence to this currently studied mode.

Certain limitations must be considered when interpreting these findings. The primary limitations involve the reliance on self-report measures that are inherently subject to bias based on social desirability of respondents, especially with sensitive topics such as alcohol use that could have serious potential professional consequences for this population.46 Furthermore, the small sample size limits generalizability. Perhaps the most significant limitation to the interpretation of the results is the racial homogeneity of this sample, which was overwhelmingly White. It is likely that officers of color, perhaps most particularly Black officers, experience burnout in a unique manner.47,48 Further research is critically needed to expand understanding of policing while Black especially as it relates to burnout and resilience. More broadly, the extent to which these current findings related to LEO burnout will be applicable in the future, given the newly intense focus on policing in America may be limited.

Conclusion

Findings from this study provide an interesting analysis of MBRTs' influence on alcohol use through burnout. Specifically, reduced alcohol use was indirectly related to reduced burnout, supporting the transdiagnostic and generalizable utility of MBRT for LEOs. Given the variety of physical, emotional, and behavioral stressors faced by LEOs and the toxic interactions that exacerbate the impact, these types of transdiagnostic resilience trainings are highly indicated. Mindfulness training provides a wide range of new coping practices for both operational and organizational stressors, which decreases burnout and leaves officers less reliant on maladaptive coping practices (i.e., alcohol use). MBIs, in general, have shown collective health benefits; this study may contribute to that growing body of evidence with MBRT potentially influencing drinking.

Authors' Contributions

This secondary analysis was proposed and designed by A.B. and K.R. Statistical analysis of data was performed by J.K., A.B., and K.R. A.E., K.R., J.K., and A.B. drafted the article, and M.C. critically revised it. All coauthors have reviewed and approved of the article before submission.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.C. received funding from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. K.R., A.E., J.K., and A.B. have no funding to disclose.

Funding Information

Research reported in this publication was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under award no. R21AT008854. This study was also funded, in part, by NIH-NCCIH T32 AT002688.

References

- 1. Stanley IH, Hom MA, Joiner TE. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;(44):25–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacobsson A, Backteman-Erlanson S, Brulin C, et al. Experiences of critical incidents among female and male firefighters. Int Emerg Nurs 2015;23:100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anshel MH. A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Crim Justice Behav 2000;27:375–400. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Wang L. Acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression in disaster or rescue workers. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1370–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. De la Fuente Solana EI, Extremera RA, Pecino CV, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of burnout syndrome among Spanish police officers. Psicothema 2013;25;488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schaible LM, Six M. Emotional strategies of police and their varying consequences for burnout. Police Q 2016;19;3–31. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prinz P, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U, et al. Burnout, depression and depersonalization—Psychological factors and coping strategies in dental and medical students. GMS Z Med Ausbild 2012;29:Doc10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rajaratnam SW, Barger LK, Lockley SW, et al. Sleep disorders, health, and safety in police officers. JAMA 2011;306:2567–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kligyte V, Connelly S, Thiel C, et al. The influence of anger, fear, and emotion regulation on ethical decision making. Human Perform 2013;26:297–326. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arslan C. An investigation of anger and anger expression in terms of coping with stress and interpersonal problem-solving. Educ Sci Theory Pract 2010;10:25–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sterud T, Hem E, Ekeberg O, et al. Occupational stress and alcohol use: A study of two nationwide samples of operational police and ambulance personnel in Norway. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007;68:896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ballenger JF, Best SR, Metzler TJ, et al. Patterns and predictors of alcohol use in male and female urban police officers. Am J Addict 2011;20:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirschman E. I Love a Cop: What Every Family Needs to Know. Guilford Press, New York; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weir H, Stewart DM, Morris RG. Problematic alcohol consumption by police officers and other protective service employees: A comparative analysis. J Crim Justice 2012;40:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zavala E, Curry TR. The role of religious coping on problematic alcohol consumption by police officers. Police Pract Res 2018;19:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohan A, O'Connor BP. Police officer job satisfaction in relation to mood, well-being, and alcohol consumption. J Psychol 2002;136:307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chopko BA, Palmieri PA, Adams RE. Critical incident history questionnaire replication: Frequency and severity of trauma exposure among officers from small and midsize police agencies. J Trauma Stress 2015;28:157–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ménard KS, Arter LM. Police officer alcohol use and trauma symptoms: Associations with critical incidents, coping, and social stressors. Int J Stress Manag 2013;20:37–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Violanti JM, Slaven JE, Charles LE, et al. Police and alcohol use: A descriptive analysis and associations with stress outcomes. Am J Crim Justice 2011;36:344–356. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kop N, Euwema M, Schaufeli W. Burnout, job stress and violent behaviour among Dutch police officers. Work Stress 1999;13:326–340. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aguayo R, Vargas C, Canadas GR, et al. Are socio-demographic factors associated to burnout syndrome in police officers? A correlational meta-analysis. An Psicol 2017;33:383–392. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. J Appl Psychol 2008;93:498–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berg AM., Hem E, Lau B.. Suicidal ideation and attempts in Norwegian police. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2003;33:302–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sack RE. Rethinking use of force: A correlational study of burnout and aggression in patrol officers. PhD dissertation. Alliant International University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oreskovich MR, Shanafelt T, Dyrbye LN, et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders in American physicians. Am J Addict 2015;24:30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel R, Huggard P, van Toledo A. Occupational stress and burnout among surgeons in Fiji. Front Public Health 2017;5:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cunradi CB, Greiner BA, Ragland DR, et al. Burnout and alcohol problems among urban transit operators in San Francisco. Addict Behav 2003;28:91–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campos DB, Schneider V, Bonafé, FS, et al. Burnout Syndrome and alcohol consumption in prison employees. Rev Bras Epidemiol 2016;19:205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moustou I, Panagopoulou E, Montgomery AJ, et al. Burnout predicts health behaviors in ambulance workers. Open Occup Health Saf J 2010;2, DOI: 10.2174/1876216601002010016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jackson ER, Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, et al. Burnout and alcohol abuse/dependence among US medical students. Acad Med 2016;91:1251–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shepherd BR, Fritz C, Hammer LB, et al. Emotional demands and alcohol use in corrections: A moderated mediation model. J Occup Health Psychol 2019;24:438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patterson GT, Chung IW, Swan PW. Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits: A meta-analysis. J Exp Criminol 2014;10:487–513. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Christopher MS, Goerling RJ, Rogers BS, et al. A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of a mindfulness-based intervention on cortisol awakening response and health outcomes among law enforcement officers. J Police Crim Psych 2015;31:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Christopher MS, Hunsinger M, Goerling LR, et al. Mindfulness-based resilience training to reduce health risk, stress reactivity, and aggression among law enforcement officers: A feasibility and preliminary efficacy trial. Psychiatry Res 2018;264:104–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grupe DW, McGehee C, Smith C, et al. Mindfulness training reduces PTSD symptoms and improves stress-related health outcomes in police officers. J Police Crim Psych 2019;36:72–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Vardakou I, et al. The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. Eur J Psychol Assess 2003;19:12–23. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greeson JM, Webber DM, Smoski JM, et al. Changes in spirituality partly explain health-related quality of life outcomes after mindfulness-based stress reduction. J Behav Med 2011;34:508–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling, 2012. http://afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf Accessed on 12 October 2017.

- 40. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40:879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cooper LM. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess 1994;6:117. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cooper LM, Russell M, George WH. Coping, expectancies, and alcohol abuse: A test of social learning formulations. J Abnorm Psychol 1988;97:218–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lechat T, Torres O. Exploring Negative Affect in Entrepreneurial Activity: Effects on Emotional Stress and Contribution to Burnout. In: Emotions and Organizational Governance (Research on Emotion in Organizations, Vol. 12). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zellars KL, Hochwarter WA, Perrewe PL, et al. Experiencing job burnout: The roles of positive and negative traits and states. J Appl Soc Psychol 2004;34:887–911. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, et al. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Krumpal I. Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Qual Quant 2013;47:2025–2047. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kurtz DL. Controlled burn: The gendering of stress and burnout in modern policing. Feminist Criminol 2008;3:216–238. [Google Scholar]

- 48. McCarty WP, Garland BE. Occupational stress and burnout between male and female police officers. Policing 2007;30:672–691. [Google Scholar]