ABSTRACT

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has imposed fundamental challenges on nearly every area of life.

Objective

The purpose of the current study was to expand on the literature on the impact of the pandemic on college students by a) examining domains of impact of the pandemic on psychiatric and alcohol outcomes and b) controlling for pre-pandemic outcomes.

Method

Participants included 897 college students (78.6% female) from a larger longitudinal study on college student mental health. Structural equation models were fit to examine how COVID-19 impact (exposure, worry, food/housing insecurity, change in social media use, change in substance use) were associated with PTSD, anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, and alcohol phenotypes. Models were fit to adjust for pre-pandemic symptoms.

Results

No effects of COVID-19 exposure remained after adjusting for earlier outcomes. COVID-19 worry predicted PTSD, depression, and anxiety, even after adjusting for earlier levels of outcomes (β’s: .091–.180, p’s < .05). Housing/food concerns predicted PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms as well as suicidal ideation (β’s: .085–.551, p’s < .05) after adjusting for earlier levels of symptoms. Change in media use predicted alcohol consumption (β’s: ± .116−.197, p’s < .05). Change in substance use affected all outcomes except suicidality (β’s: .112–.591, p’s < .05).

Conclusions

Domains of COVID-19 impact had differential effects on mental health and substance outcomes in college students during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Future studies should examine the trajectory of these factors on college student mental health across waves of the pandemic.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, pandemic, college students, traumatic stress, substance use, mental health

HIGHLIGHTS

SEMs were used to find that five correlated domains of COVID-19 impact were associated with mental health and substance outcomes in college students during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: La pandemia de COVID-19 ha impuesto desafíos fundamentales en prácticamente todas las áreas de la vida.

Objetivo: El propósito del presente estudio fue ampliar la literatura sobre el impacto de la pandemia en estudiantes universitarios, a) examinando dominios de impacto de la pandemia sobre resultados psiquiátricos y de alcohol, y b) controlando por resultados pre-pandemia.

Método: Los participantes incluyeron 897 estudiantes universitarios (78,6% mujeres) de un estudio longitudinal más grande sobre salud mental de estudiantes universitarios. Se ajustaron modelos de ecuaciones estructurales para examinar cómo se asociaba el impacto del COVID-19 (exposición, preocupación, inseguridad de alimentos/habitación, cambio en el uso de medios sociales, cambio en uso de sustancias) con los fenotipos TEPT, ansiedad, depresión, ideación suicida y alcohol. Los modelos se ajustaron por síntomas pre-pandémicos.

Resultados: No permanecieron efectos de la exposición al COVID-19 luego de ajustar por resultados previos. La preocupación por el COVID-19 predijo TEPT, depresión y ansiedad incluso luego de ajustar por niveles previos de resultados (β’s: .091–.180, p’s < .05). Los problemas de habitación/alimentación predijeron síntomas de TEPT, ansiedad y depresión así como también ideación suicida (β’s: .085–.551, p’s < .05) después de ajustar por niveles sintomáticos previos. El cambio en el uso de medios predijo el consumo de alcohol (β’s: ±.116–.197, p’s < .05). El cambio en el uso de sustancias afectó a todos los resultados excepto suicidalidad (β’s: .112–.591, p’s < .05).

Conclusiones: Los dominios de impacto del COVID-19 tuvieron diferentes efectos sobre los resultados de salud mental y uso de sustancias en estudiantes universitarios durante la primera ola de la pandemia de coronavirus. Futuros estudios deberían examinar la trayectoria de esos factores en la salud mental de estudiantes universitarios a través de las olas de la pandemia.

PALABRAS CLAVE: COVID-19, pandemia, estudiantes universitarios, estrés traumático, uso de sustancias, salud mental

Short abstract

背景: COVID-19 疫情几乎对生活的所有领域都带来了根本性的挑战。

目的: 本研究旨在通过 a) 考查疫情对精神和酒精结果的影响领域, 以及 b) 控制疫情前结果, 扩展有关疫情对大学生影响的文献。

方法: 参与者包括来自一项更大型大学生心理健康纵向研究的 897 名大学生 (78.6% 为女性) 。结构方程模型适用于考查 COVID-19 的影响 (暴露, 担忧, 食物/住房不安全, 社交媒体使用的变化, 物质使用的变化) 如何与 PTSD, 焦虑, 抑郁, 自杀意念和酒精表型相关联。模型在控制疫情前症状中拟合。

结果: 在控制了早期结果后, COVID-19 暴露没有影响。 COVID-19 担忧预测了 PTSD, 抑郁和焦虑, 即使在控制了早期结果水平之后 (β:0.091–.180, p< .05) 。在控制了早期症状水平后, 住房/食物问题可预测 PTSD, 焦虑和抑郁症状以及自杀意念 (β:.085–.551, p< .05)。媒体使用的变化预测了饮酒量 (β:±.116–.197, p< .05)。物质使用的变化影响除自杀之外的所有结果 (β: .112–.591, p< .05)。

结论: 在第一波冠状病毒疫情期间, COVID-19 影响领域对大学生的心理健康和物质结果有不同的影响。未来研究应该考查这些因素在疫情波动中对大学生心理健康的影响。

关键词: COVID-19, 疫情, 大学生, 创伤应激, 物质使用, 心理健康

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic is a large-scale stressor with widespread detrimental impacts on numerous domains of functioning. Although the pandemic has impacted individuals on a global level, there is heterogeneity in the impact of COVID-19 and related stressors, as is seen with other large-scale stressors and traumatic events, such as natural disasters (e.g. Schwartz, Gillezeau, Liu, Lieberman-Cribbin, & Taioli, 2017). Although the severity of the effects of the pandemic varies by domain (e.g. physical health, behavioural factors, social impact, etc.) on an individual basis, it is likely that exposure to COVID-19 through any one of these domains is related to worsened mental health and substance use outcomes. Analyses from our group (Bountress et al., 2021) find that the impact of the pandemic is best modelled by five correlated factors (i.e. exposure, worry, food/housing instability, changes in social media use, changes in substance use). The purpose of this longitudinal study is to determine how severity of exposure to the pandemic is associated with mental health and alcohol use outcomes (i.e. posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD], anxiety, depression, alcohol use, alcohol use disorder [AUD]) in the acute phase of the pandemic (i.e. spring/summer 2020), adjusting for pre-pandemic levels of each outcome.

Indeed, recent literature has demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on population mental health including but not limited to: anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms (see Salari et al., 2020), insomnia, and posttraumatic stress symptoms (for a review and meta-analysis, see Krishnamoorthy, Nagarajan, Saya, & Menon, 2020). More specifically, this research has evidenced an increase in anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts (e.g. Patsali et al., 2020) since the start of the pandemic, with people of colour being reporting higher prevalence rates of depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and substance use (e.g. McKnight-Eily et al., 2021). Not only have studies demonstrated an increase in anxiety and depressive symptoms from pre-pandemic to after the start of the pandemic, research has also shown that these symptoms have not improved from the initial outbreak to various follow-up timepoints throughout the course of the pandemic, further highlighting the importance of work related to mental health consequences of COVID-19 (Vindegaard & Benros, 2020).

In addition to internalizing phenotypes, the extant literature has shown that the pandemic has also spurred an increase in alcohol use (e.g. Pollard. Tucker, & Green, 2020), cannabis use (Bartel, Sherry, & Stewart, 2020), and overdosing on opioids (Haley & Saitz, 2020). Not only have levels of consumption increased with the pandemic, problems secondary to consumption have also increased. Indeed, Pollard et al. (2020) found a 39% increase in problems related to alcohol use as compared to the 2019 average, independent of consumption levels. Thus, the existing research has shown that the pandemic has adversely impacted mental health and substance use outcomes, though methodological limitations preclude a comprehensive understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on outcomes (e.g. lack of assessment of severity of impact).

Specifically, although many of the studies conducted to date have been longitudinal, most do not directly assess COVID-19 impact. Instead, studies examine mental health symptoms pre-and post-COVID-19 for significant differences and inferred the impact of COVID-19. For example, in a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies examining the psychological impact of COVID-19 (Prati & Mancini, 2021), the majority of studies use within-person designs that compare pre- and post-COVID-19 scores. One study assessed domains of COVID impact (e.g. perceived risk of death due to COVID-19; Robinson & Daly, 2020). However, these authors simply counted the number of stressful experiences individuals endorsed during the pandemic – that is, they did not account for the fact that there might be distinct COVID impact factors. The present study extends this work by controlling for pre-COVID levels of symptoms, and using more rigorous modelling of impact (Bountress et al., 2021), to allow for stronger inferences about the unique impact of COVID-19 on variables of clinical significance.

In addition to directly assessing the effects of domains of COVID-19 impact on mental health symptoms and substance use using rigorous statistical modelling, the present study includes a sample of college students, a specific population in need of further examination, given that student lives have been impacted in unique ways as compared to the general population (e.g. initially unable to return to dorms, jobs, classes; Copeland et al., 2021). The majority of studies that longitudinally examine the impact of COVID-19 on mental health symptoms include adult populations more generally (for a meta-analysis, see Prati & Mancini, 2021). The few studies that have examined changes in mental health related to COIVD-19 in college student populations specifically have found that COVID-19 has adversely impacted the mental health of college students, with both externalizing (Copeland et al., 2021) and internalizing symptoms (Huckins et al., 2020). In addition to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms, changes in substance use in college students have been evidenced, whereby alcohol consumption (amount and frequency) increased as the duration of University closures increased, and further, these alcohol consumption increases were associated with increased anxiety and depressive symptoms (Casale, Caponi, & Fioravanti, 2020). Given the different ways that the COVID pandemic uniquely impacted college students (e.g. most moved home to live with their families), continued research with this population is an important next step. Lastly, much of the research that has been rapidly published on the pandemic involves statistically modelling mental health outcomes and substance use separately, which is problematic as comorbidity following trauma is the norm (Marthoenis, Ilyas, Sofyan, & Schouler-Ocak, 2019).

The present study sought to build upon prior work examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and substance use outcomes, investigating how domains of impact of the pandemic are associated with psychiatric and alcohol use outcomes. We conducted two sets of models, one adjusted and one unadjusted for pre-COVID-19 mental health and alcohol use phenotypes. We hypothesized that higher levels on all outcomes would be found at the COVID-19 assessment compared to the pre-pandemic report, that the impact of COVID-19 across the correlated domains would be associated with adverse mental health and alcohol use phenotypes, and that the relations between domains of impact and outcomes would be attenuated, yet still significant, when controlling for pre-pandemic mental health and alcohol use.

2. Method

2.1. Larger study sample

Participants for the current project came from a larger, ongoing longitudinal study of college student well-being at a mid-Atlantic public university. Cohorts of incoming first-year students, ages 18 and older, were invited to participate. This study was approved by Virginia Commonwealth University’s institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent. Baseline and multiple follow-up surveys were collected on five cohorts, with the first enrolled in 2011, during the fall and spring semesters (i.e. fall of first year and each spring after). Data for all surveys were collected online, through Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Harris et al., 2009). The project began in fall 2011, and new cohorts were recruited in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2017 (N = 12,358). Participants were on average 18.49 years old at baseline, and 36.7% were male, 61.9% were female; 1.4% declined to identify their sex. The sample was representative of its population: 47.9% White, 19.3%, Black, 16.6% Asian, 6.6% Hispanic/Latino, 9.6% other/multi-race/unknown/declined to respond.

2.2. Current study sample

Only the fifth cohort of students were still enrolled at the university during the onset of the pandemic. These students who began participating in the larger study during fall of their freshman year (2017) and who were still enrolled as at the university in the spring of 2020 were recruited for a COVID-related survey in the spring/summer of 2020. Thus, requirements to be in the current study analyses were that individuals must have been in the fifth cohort of the original study and still enrolled in the university in spring 2020. All surveys were completed between 7 May 2020 and 17 July 2020 with 87% occurring in May. There were in general no differences between those completing ‘early’ (in May 2020) versus ‘late’ (June or July 2020) on all study variables, including race, PTSD, anxiety, depression symptoms, suicidal ideation, alcohol consumption or AUD symptoms. There was a sex difference, such that a greater percent of those completing early were female (79.8%), compared to the percent of those completing late (69.3%; Chi-square: 5.890, p < .05); this was a small effect (Cramer’s V: .083).

Prior to the COVID survey, these individuals were interviewed in the fall of 2017 (year 1 fall/freshman year), in the spring of 2018 (year 1 spring/freshman year), spring of 2019 (year 2 spring/sophomore year), and spring/summer of 2020 (year 3 spring/junior year), following COVID-19 being declared a pandemic in March of 2020. Of note, only the last two of these surveys provided data for the current study analyses (i.e. spring 2019/year 2 spring and spring/summer 2020/year 3 spring). Of the N = 1,899 in cohort five who were invited to participate in this survey, 897 (47.2%) completed it. The goal of this survey was to understand how students experienced and responded to COVID-19 and its sequelae. Individuals who completed the survey were more likely to be female (78.6% versus 62% of those not participating), were more likely to Asian (22.9% versus 15.3%) and were less likely to be Black (18.4% versus 22.4%) or White (40.2% versus 44%). They also reported more earlier levels of anxiety, depression, but less alcohol consumption and less problems (among drinkers). These effects were all small (Cramer’s V range: .117-.171, Cohen’s d: .22-.26) or small-medium (Cohen’s d: .37). There were no differences on earlier levels of PTSD symptoms or suicidal ideation. Table S1 displays the sex and race/ethnic break down for the university as a whole, the larger study, as well as this sub-sample.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographic predictors

Sex assigned at birth was coded 0 for Female (78.6%) and 1 for Male (21.4%). To maximize the power to detect potential race differences, individuals were coded as being in one of the three largest groups: White, Black, Asian, or were coded as Other. Thus, three dummy coded variables comparing White (40.2%) to Black (18.4%), Asian (22.9%) and Other (18.4%) were created with the White group coded as all zeros serving as the reference group.

2.3.2. COVID-19 impact

Building upon prior work from this dataset (Bountress et al., 2021), in which a single factor, five correlated factors, hierarchical, and bifactor models were all estimated, and fit indices and factor loadings compared, the five correlated factor model tapping distinct but related COVID-impact-related constructs was found to represent the item response data most adequately. Specifically, these constructs map onto COVID-19 exposure (e.g. exposed to someone likely to have COVID), COVID-19 worry (e.g. worry about family/friends being infected), housing/food concerns (e.g. concern whether food will run out because of money), change in media use (e.g. amount of social media), and change in substance use (i.e. alcohol, marijuana, tobacco products, vaping). Higher scores on all factors indicate more risk. The items that comprise the indicators for these factors come from the Coronavirus Health Impact Survey and the Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory.

2.4. Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS)

The CRISIS measure was developed to assess COVID-19 impact. Although developed by content experts in the field, including intramural NIMH researchers (Merikangas & Stringaris, 2020), due to the unexpected nature of COVID, psychometric developments had not been undertaken at the time of the development of this tool. Twenty-four of the COVID-related impact items were taken from the CRISIS (e.g. ‘Have you been exposed to someone likely to have COVID?’, ‘Do you worry whether food will run out because of lack of money?’) adapting to fit the needs of college student population (e.g. assessing whether activities have been able to be transferred to virtual format). Answer choices varied by question, but can be seen, along with all included items in the original paper by this author group on which this paper builds (Bountress et al., 2021). This scale has demonstrated good concurrent and predictive validity (Nikolaidis et al., 2020).

2.5. Epidemic-Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII)

Like the CRISIS, the EPII was developed by content experts in the field (Grasso, Briggs-Gowan, Ford, & Carter, 2020). Twenty of the COVID-19 impact items used in this survey were taken from the EPII (Grasso et al., 2020), assessing ‘tangible impacts’ of epidemics (e.g. impact of COVID-19 on social life, ‘Has to move or relocate’, ‘became homeless’). This measure assesses whether individuals experienced a range of difficulties including but not limited to those of work- (e.g. being laid off), education- (e.g. had a child in home unable to attend school), and home life (e.g. family or friends moving in). Response options were ‘Yes, me’, ‘Yes, person in my home’, ‘No’, and ‘Not applicable’). Although little data are available on the EPII’s psychometric properties, initial data support its utility as a tool for assessing personally relevant events occurring during the COVID pandemic (Grasso, Briggs‐Gowan, Carter, Goldstein, & Ford, 2021). Included questions and answers can be seen, along with all included items in the original paper by this author group on which this paper builds (Bountress et al., 2021).

2.5.1. Mental health and substance use covariates and outcomes

Mental health and alcohol use symptoms were administered at two assessments: during the COVID-19 survey as the primary outcomes, as well as one year prior (i.e. year 2 spring). Mental health and substance use variables coming from the year 2 spring assessment were used as covariates in the prediction of these same symptoms assessed during the COVID-19 survey.

2.6. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms

Participants reported on their past month PTSD symptoms via the PTSD Checklist (PCL)-5 (Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015), comprised of 20 items assessing re-experiencing, avoidance, hypervigilance, and negative alterations in mood/cognitions. Participants reported their symptoms with regard to the pandemic. This scale showed good internal consistency in the current dataset at the year 2 spring and COVID time points (alpha:.962, .982, respectively) and has demonstrated strong reliability and validity in published work (Blevins et al., 2015).

2.7. Anxiety symptoms

Participants reported their anxiety symptoms since the onset of COVID-19 using the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90, Todd, Deane, & McKenna, 1997). The SCL-90 asks participants about symptoms using a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely). A sum of four anxiety items (e.g. nervousness or shakiness) was created. This scale showed good internal consistency in the current dataset at the year 2 spring and COVID time points (alpha: .869, .902, respectively) and the SCL-90 has demonstrated strong reliability and validity (Martinez, Stillerman, & Waldo, 2005).

2.8. Depressive symptoms

Participants reported on their depressive symptoms since the onset of COVID-19 using items from the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90, Todd et al., 1997). A sum of the four depression items (e.g. feeling blue, blaming yourself for things) was created. This scale showed good internal consistency in the current dataset at the year 2 spring and year 3 spring COVID time points (alpha: .851, .894, respectively).

2.9. Suicidal ideation

Participants reported on their suicidal ideation since the onset of COVID-19 using one item from the Symptom Checklist-90 Revised (SCL-90, Todd et al., 1997). Specifically, participants answered whether they had thought about killing themselves (yes or no).

2.10. Alcohol consumption

Participants reported on their alcohol use since the onset of COVID-19 with ordinal frequency and quantity items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). These items were combined to create a single ‘grams of ethanol consumed per month’ alcohol use variable using a method previously reported in (Dawson, 2000), and used by (Salvatore et al., 2016). During the COVID-19 survey, individuals consumed ~72.37 g of ethanol per month (i.e. between 5–6 standard drinks; SD: 198.44). As the skew and kurtosis were outside of acceptable thresholds (±2, 7), this variable was log transformed. The year 2 spring survey this measure as also administered, and participants reported consuming ~140.74 grams of ethanol per month (i.e. about 10 standard drinks; SD: 298.51); a log transformation was also conducted.

2.11. Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) symptoms

Participants reported on AUD symptoms since the onset of COVID-19 using DSM-5 AUD symptoms from the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA, Bucholz et al., 1994). The 11 symptoms (e.g. drinking interfered with professional responsibilities) were summed to create a DSM-5 AUD Symptoms score at each time point used for analyses. These items showed adequate internal consistency in the current dataset among drinkers at the year 2 spring and year 3 spring COVID time points (alpha: .918, .752, respectively).

2.12. Data analysis

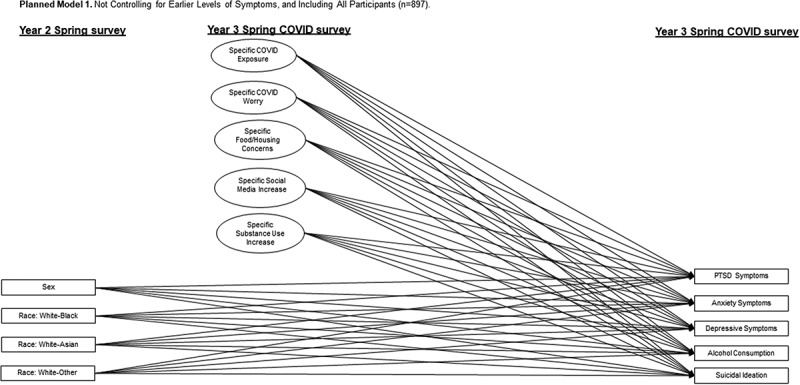

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize mental health and alcohol outcomes at the two time points, including tests of significance. To investigate the primary study questions, four structural models were specified and estimated (see Figure 1 for diagrammatic presentation of these four models). Specifically, five correlated factors capturing COVID impact, as well as covariates and outcomes, were simultaneously modelled. The measurement portion of the model was generated in a prior set of analyses by this group (Bountress et al., 2021), which provides all included items and answer choices as well as standardized loadings. Within this model, both the COVID impact factors among one another, and the mental health and alcohol outcomes, were allowed to correlate. All modelling was conducted in Mplus Version 8, using the WLSMV estimator, and missing data were estimated using Maximum Likelihood estimation. To evaluate model fit, three omnibus fit indices (Comparative Fit Index (CFI): ≥.9, Tucker Lewis Index (TLI): ≥.9, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤.08; Hu & Bentler, 1999) were examined.

Figure 1.

Depiction of first planned model to be tested.

Model Two builds on this model by adding PTSD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, and alcohol consumption and suicidal ideation at year 2 spring as covariates. Models Three and Four are identical to One and Two with a couple exceptions, namely that those models will only include drinkers (n = 696) and AUD symptoms will be added as an outcome (Models Three and Four), with earlier AUD symptoms as a covariate (Model Four).

Model One examined the impact of the five correlated COVID-19 impact factors on symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression, as well as alcohol consumption and suicidal ideation. Race and sex were included as additional covariates but were dropped when non-significant (p < .05). Model Two built on Model One, adding earlier assessments of the outcome in as a covariate in the prediction of each dependent variable. All n = 897 individuals were included in these first two models. Significant predictor effects of COVID-19 impact within Model Two were set to zero to determine how robust these effects are when allowing the full model to compensate for these significant effects being forced to be zero.

Model Three and Four built on these models, adding AUD symptoms as an outcome. Thus, only drinkers were included in the analyses for Models Three and Four (n = 696) – this was done to avoid conflating alcohol use and AUD symptoms that would occur if abstainers were simply given a score of zero on AUD symptoms. Again, non-significant (p < .05) effects of race and sex were dropped. Significant predictor effects of COVID-19 impact within Model Four were set to zero and global misfit was determined. Table S2 provides the fit indices for all intermediate (i.e. with covariates not trimmed) to final models (Models 1–4).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

We present descriptive information for PTSD, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, as well as alcohol consumption, suicidal ideation, and AUD symptoms for the full sample, as well as for drinkers, in Table 1. PTSD symptoms did not change between the year prior to COVID (year 2 spring) and the spring when COVID was beginning (year 3 spring). For all other variables, participants reported significant (p < .05) decreases in symptoms.

Table 1.

Descriptive information and tests of change over time for mental health and alcohol outcomes

| Study constructs | Time 1 (year 2 spring) M (SD) or % | Time 2 (COVID questionnaire) M (SD) or % | t(p) or McNemar’s Test | Cohen’s d or Cramer’s V (size of effect) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample (n = 897) | ||||

| PTSD Symptoms | 20.31 (18.59) | 21.79 (19.46) | t = −1.21 (NS) | −.07 (small) |

| Anxiety Symptoms | 7.94 (3.77) | 7.18 (4.04) | t = 4.99 (p < .001) | .20 (small) |

| Depressive Symptoms | 10.63 (4.05) | 10.17 (4.72) | t = 2.62 (p < .01) | .10 (small) |

| Alcohol Consumption | 1.55 (.79) | .93 (.98) | t = 14.13 (p < .001) | .61 (medium/large) |

| Suicidal Ideation | 38.2% | 12.7% | McNemar’s Test = p < .001 | .33 (small/medium) |

| Including Drinkers Only (n = 696) | ||||

| PTSD Symptoms | 20.54 (19.27) | 22.74 (19.86) | t = −1.60 (NS) | −.10 (small) |

| Anxiety Symptoms | 8.04 (3.83) | 7.22 (4.04) | t = 4.72 (p < .001) | .21 (small) |

| Depressive Symptoms | 10.79 (4.13) | 10.32 (4.70) | t = 2.27 (p < .05) | 10 (small) |

| Alcohol Consumption | 1.62 (.77) | 1.00 (.98) | t = 13.46 (p < .001) | .61 (medium/large) |

| Suicidal Ideation | 41.6% | 13.6% | McNemar’s Test = p < .001 | .31 (medium) |

| AUD Symptoms | 2.29 (2.61) | 1.52 (2.11) | t = 5.70 (p < .001) | .29 (small/medium) |

t-Test or McNemar’s Test, and Cohen’s d or Cramer’s V were used when outcomes were continuous or categorical, respectively.

3.2. Models one and two

See Figure 1 for visual depiction of Model One. Table 2 provides results from Models One and Two. Model One showed fits at the lower end of recommended cut-offs for fit indices, χ2(310) = 1289.56, p < .001; CFI: .91, TLI: .88, but acceptable fit based on approximate model fit (RMSEA = .06). In terms of constructs associated with PTSD symptoms, those who experienced greater COVID-related exposure, worry, housing/food instability, and increase in substance use, reported greater levels of symptomatology. These same four factors were related to anxiety and depression symptoms as well, with the addition that females reported more anxiety and depression compared to males. Those who reported increases in substance use reported more alcohol consumption, but no other factors or covariates were associated with alcohol consumption. Those who experienced more COVID-19 exposure, housing/food instability, and increases in substance use reported higher likelihood of suicidal ideation. Additionally, Whites were more likely to report suicidal ideation than Asians, but there were no sex and no other race differences.

Table 2.

Standardized betas and standard errors for models one and two (full sample; n = 897)

| PTSD symptoms |

Anxiety |

Depression |

Consumption |

Suicidal ideation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | SE | Β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE |

| Model 1: All Participants | ||||||||||

| Exposure | .122*** | .044 | .131** | .041 | .136** | .044 | −.032 | .037 | .216** | .072 |

| Worry | .182*** | .036 | .228*** | .039 | .139** | .040 | −.013 | .036 | .028 | .069 |

| Housing/Food Stability | .267*** | .044 | .131** | .044 | .229*** | .043 | −.045 | .039 | .376*** | .078 |

| Change in Media Use | .027 | .051 | .044 | .049 | .079 | .051 | .086 | .049 | −.138 | .086 |

| Change in Substance Use | .261*** | .043 | .176*** | .044 | .254*** | .042 | .644*** | .036 | .192* | .086 |

| Sex | −.076* | .036 | −.106*** | .030 | ||||||

| Race: White-Black | −.151 | .107 | ||||||||

| Race: White-Asian | −.329** | .112 | ||||||||

| Race: White-Other | −.065 | .097 | ||||||||

| Model 2: All Participants, Controlling for Earlier Levels of Outcomes | ||||||||||

| Exposure | .083 | .049 | .059 | .038 | .071 | .041 | −.026 | .037 | .098 | .089 |

| Worry | .161** | .048 | .180*** | .039 | .113** | .038 | .002 | .036 | .026 | .077 |

| Housing/Food Stability | .181*** | .051 | .085* | .041 | .165*** | .042 | −.065 | .038 | .551*** | .112 |

| Change in Media Use | −.004 | .058 | .052 | .048 | .087 | .047 | .068 | .051 | −.197* | .096 |

| Change in Substance Use | .201*** | .050 | .112** | .039 | .185*** | .040 | .591*** | .042 | −.117 | .140 |

| Sex | −.034 | .038 | −.071* | .031 | ||||||

| Race: White-Black | −.763** | .291 | ||||||||

| Race: White-Asian | −.912*** | .276 | ||||||||

| Race: White-Other | −.666* | .272 | ||||||||

| Year 2 Spring Symptoms | .412*** | .040 | .422*** | .032 | .378*** | .035 | .102* | .041 | .343*** | .070 |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; Sex: 0 = Female, 1 = -Male; Race: For all 0 = White, For first: 1 = Black, second: 1 = Asian, third: 1 = Other.

Consumption = Alcohol Consumption. Year 2 Spring Symptoms corresponds to earlier levels of the outcome for each model.

Model Two fit (χ2(405) = 1436.26, p < .001; CFI: .90, TLI: .87, RMSEA: .05) was similar to Model One falling at the lower end of conventional recommendations for acceptable goodness-of-fit values. In general, adding earlier PTSD symptoms, which was a significant predictor such that higher levels of earlier symptoms were associated with higher later symptoms, did not change the estimates in the prediction of PTSD. The one exception to this was that COVID-related exposure no longer was associated with PTSD symptoms. The findings for anxiety and depression were nearly identical: the effects of worry, housing/food instability, and change in substance use remained with the addition of earlier assessed levels of the outcomes, which were both statistically significant, except for exposure which was no longer a significant predictor. A significant sex effect for depression remained, but not for anxiety. In terms of alcohol consumption, only change in substance use remained significantly associated following the addition of earlier reported levels of alcohol consumption, which was also a significant predictor with higher earlier levels of alcohol consumption associated with higher later levels. Finally, in terms of suicidality, the effects of exposure and change in substance use were rendered non-significant when earlier levels of suicidality were included. However, housing/food stability remained significant. Change in media was related to suicidality even with the inclusion of earlier levels of suicidality, but in the opposite direction – such that, higher levels of media use were associated with reduced risk of suicidality. The other effects of race also became significant, specifically White participants reported higher risk than Blacks and Others, as well as Asians (this effect was present in Model Three as well). A model setting all significant (p < .05) COVID-19 impact effects on mental health and substance use outcomes to zero produced a significant misfit χ2(12) = 153.86, p < .001, confirming that imposing such a joint restriction on significant path coefficients within the full model results in a poorer model-data fit.

3.3. Models three and four

Table 3 gives results for Models Three and Four. Model Three also had fit indices at the low end of the range of conventional acceptable omnibus fits, χ2(267) = 997.32, p < .001; CFI: .92, TLI: .89, RMSEA: .06. Those who experienced greater COVID-related exposure, worry, housing/food instability, and increases in substance use, reported more PTSD symptoms. Additionally, on average, females reported more symptoms than males. The same impact factors and sex was related to anxiety and depression symptoms, with again women reporting more anxiety and depression symptoms than males. In terms of alcohol consumption, those who reported less housing/food instability, more increase in media use and more increase in substance use reported more alcohol use. Those reporting greater COVID-19 exposure, more housing/food instability, and more increases in substance use reported higher likelihood of suicidal ideation. Females also reported higher likelihood of suicidality than males. In terms of AUD symptoms, those with more COVID-19 exposure, more housing/food stability and more increase in substance use, reported more symptoms.

Table 3.

Standardized betas and standard errors for models three and four (drinkers only sample; n = 696)

| PTSD symptoms |

Anxiety |

Depression |

Consumption |

Suicidal ideation |

AUD symptoms |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE |

| Model 3: All Participants | ||||||||||||

| Exposure | .095* | .047 | .113* | .045 | .105* | .049 | −.012 | .040 | .197* | .078 | .114* | .052 |

| Worry | .160*** | .041 | .228*** | .047 | .115* | .047 | −.007 | .041 | −.038 | .080 | −.054 | .057 |

| Housing/Food Stability | .274*** | .047 | .135** | .048 | .239*** | .047 | −.090* | .042 | .304*** | .081 | .197*** | .054 |

| Change in Media Use | .024 | .060 | .024 | .057 | .085 | .060 | .127* | .056 | −.087 | .096 | −.021 | .081 |

| Change in Substance Use | .268*** | .048 | .211*** | .050 | .275*** | .046 | .617*** | .042 | .308*** | .074 | .372*** | .048 |

| Sex | −.080* | .038 | −.096* | .041 | −.128*** | .035 | −.145* | .066 | ||||

| Model 4: All Participants, Controlling for Earlier Levels of Outcomes | ||||||||||||

| Exposure | .064 | .049 | .057 | .042 | .068 | .046 | −.010 | .040 | .148 | .078 | .084 | .047 |

| Worry | .141** | .048 | .180*** | .046 | .091* | .045 | −.007 | .041 | −.054 | .077 | −.052 | .057 |

| Housing/Food Stability | .223*** | .053 | .064 | .047 | .181*** | .048 | −.093* | .043 | .308*** | .080 | .229*** | .055 |

| Change in Media Use | −.023 | .062 | .051 | .056 | .095 | .055 | .116* | .058 | −.067 | .093 | −.082 | .083 |

| Change in Substance Use | .198*** | .054 | .148** | .046 | .210*** | .045 | .568*** | .049 | .237** | .077 | .275*** | .053 |

| Sex | −.100* | .046 | −.041 | .042 | −.088* | .035 | ||||||

| Year 2 Spring Symptoms | .350*** | .043 | .415*** | .036 | .338*** | .040 | .109* | .046 | .353*** | .065 | .336*** | .043 |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; Sex: 0 = Female, 1 = -Male. Consumption = Alcohol Consumption. Year 2 Spring Symptoms corresponds to earlier levels of the outcome for each model.

Fitting Model Four produced the following fit indices, χ2(388) = 1149.99, p < .001; CFI: .91, TLI: .88, and RMSEA = .05. For PTSD, adding earlier levels of PTSD symptoms into the model resulted in significant prediction, and generally did not alter findings. The one exception was that COVID-related exposure no longer was associated with PTSD symptoms. In terms of anxiety symptoms, those reporting greater worry and an increase in substance use, as well as those with more prior anxiety symptoms, reported higher levels. In terms of depression, those with greater worry, housing/food instability, and greater change in substance use reported more symptoms. Additionally, females and those reporting more earlier depression symptoms also reported higher levels. In terms of alcohol consumption, those reporting less housing/food instability, more increase in media consumption, and more increase in substance use reported more alcohol use. Additionally, those with higher levels of earlier consumption reported more consumption later as well. For suicidality, those with more housing/food instability and more increase in substance use reported higher likelihood of suicidal ideation. Those with prior ideation were also more likely to report suicidal ideation. Finally, those reporting more housing/food instability and more increase in substance use reported more AUD symptoms. Those reporting more earlier AUD symptoms also reported more symptoms later. The model setting all significant (p < .05) COVID-19 impact effects on mental health and substance use outcomes to zero indicated a significant increase in misfit χ2(19) = 98.64, p < .001, suggesting that there would be a significant decrease in fit if those paths were to be set to zero.

4. Discussion

The present study extends the psychological literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among college students in a number of ways, perhaps the most significant of which stems from the availability of pre-pandemic assessments. Contrary to our hypotheses, the COVID-19 assessment reports of psychological and alcohol use outcomes were either not significantly different from pre-pandemic report, or were actually lower than what was reported during the prior year’s assessment. These findings, while surprising given the literature on the psychological correlates of the pandemic (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020), highlight the need for more study among college students.

While previous research has examined deleterious mental health and substance use outcomes during the pandemic, the current study sought to examine how domain-specific impacts of COVID-19 constructs affect these outcomes. We hypothesized that the domains of impact of COVID-19 would be associated with adverse mental health and alcohol use phenotypes and that the relations between domains of impact and outcomes would be attenuated when controlling for pre-pandemic mental health and alcohol use. Through our systematic analytic approach estimating four different models, three key findings emerged to offer a more nuanced understanding of the specific ways COVID-19 factors impact college student’s psychiatric and alcohol outcomes during the acute phase (i.e. spring/summer 2020) of the pandemic.

First, consistent with the extant literature on PTSD, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020), in the full sample (Models One and Two), increasing levels (greater negative impact) on the COVID-19 exposure, worry, housing/food instability, and substance use were associated with higher PTSD, anxiety, and depression symptoms. Interestingly, the COVID-19 exposure factor itself became non-significant after adjusting for pre-pandemic symptomatology. One explanation is that these data were collected relatively early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, when the University was still operating virtually.

Previous studies of the acute response to the pandemic have shown women have greater symptomatology in depression, anxiety and PTSD globally (González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020; Odriozola-González, Planchuelo-Gómez, Irurtia, & de Luis-garcía, 2020; Wang et al., 2020), and in college populations in the USA (Wang et al., 2020), yet we only found this for depression in the full sample. Further, among drinkers, women had higher PTSD symptoms than men. This finding is novel because, unlike most of the extant COVID-19 research, our approach accounted for the covariation between co-morbid mental health symptoms.

Second, in regard to suicidal ideation, higher COVID-19 exposure, housing/food instability, and changes in substance use were associated with higher likelihood of endorsement. When controlling for prior suicidal ideation, the effects of exposure and change in substance use became non-significant, yet housing/food instability remained significant. These results suggest that perhaps concern about having consistent basic needs is associated with risk for suicidal ideation.

Interestingly, the effect of media use was significant, but in the opposite direction than was hypothesized – higher levels of media use was associated with lower risk of suicidality. Social media is a key factor in spreading misinformation (Zarocostas, 2020), yet it also can serve as a health technology intervention (Cuello-Garcia, Pérez-Gaxiola, & van Amelsvoort, 2020) and important means of staying connected in a time of extreme disconnection. Given the extreme isolation that occurred as a result of the necessary public health measures to quarantine, perhaps the increase in a college sample social media use buffered against the social consequences of lockdown.

Previous research (O’Connor et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020) found no race or sex effects on suicidal ideation during the pandemic. We largely found this to be true in our initial models, however, among drinkers, females were at higher risk for suicidal ideation. Importantly, when controlling for pre-COVID-19 rates, race was also associated with ideation. White participants reported higher risk than Blacks and Others, as well as Asians. This is contrary to findings from a previous study on a U.S. sample collected at roughly the same time as the present study (Czeisler et al., 2020).

Current study findings are interesting to think about in the context of a lack of race/ethnic differences on alcohol use and AUD symptoms. Specifically, prior to COVID, Whites have typically reported more alcohol use than Blacks and Asians, at least among college students (LaBrie, Lac, Kenney, & Mirza, 2011; McCarthy, Miller, Smith, & Smith, 2001). The fact that no race/ethnic differences emerged – coupled with a general decrease in consumption and AUD symptoms – may mean a couple different things. It may mean that there was a bit of a floor effect, such that all groups found it difficult to consume alcohol or experience AUD symptoms in this new setting – resulting in no group differences. It is also possible that Whites in particular used college as a setting to consume/misuse alcohol, and thus began consuming less and experiencing less problems when they moved home to live with families, making their alcohol use/AUD symptoms ‘look’ more like the low levels reported historically by other race/ethnic groups.

Finally, in contrast to research on the psychological ramifications of the pandemic, less research has measured the impact on alcohol consumption and AUD. In the general adult population, self-reported alcohol use has been found to be higher than before the pandemic (Pollard et al., 2020). However, among college students, studies (White, Stevens, Hayes, & Jackson, 2020) have reported decreased drinking during the pandemic, likely resulting from shifts in environmental risk factors (e.g. increased parental monitoring if students moved home resulting in reduced availability of alcohol). In the present study, the second set of models were tested on a reduced sample of the subset of drinkers (n = 696). Among drinkers, those with increased media use and more housing/food insecurity had higher consumption.

In analyses limited to current drinkers, AUD symptoms was added as an outcome. Higher COVID-19 exposure, food/housing instability, and substance use were all associated with higher AUD symptoms, but similar to the mental health findings in the full sample COVID-19 exposure did not remain significant when controlling for prior AUD symptoms. An increase in food/housing instability and substance use was significant. Food insecurity is an increasing problem facing college students, disproportionally affecting those receiving financial aid, who are Black or Hispanic, and are housing insecure (Payne-Sturges, Tjaden, Caldeira, Vincent, & Arria, 2018). This highlights the ongoing needs related to the interaction between AUD and the burden of financial secondary stressors that will likely impact communities in unique ways long after the physical effects of the health pandemic.

4.1. Limitations

This study extends the literature on the specific impacts of COVID-19 by employing sophisticated modelling of COVID impact on outcomes longitudinally, among college students. However, several limitations should be taken into consideration. While this study utilized a sample that matched the racial/ethnic makeup of the broader community from which it came, it is limited to college-aged students at one south-eastern university. There were relatively few significant differences by race/ethnicity, yet we know that COVID-19 impacts racial/ethnic communities in disproportionate ways (Bowleg, 2020; Selden & Berdahl, 2020). Further, there are likely differences in persons of colour who attend college compared to those that do not that may be influencing our findings. Additionally, the sample was predominantly female, so these findings may not generalize as well to males. Finally, the COVID impact factors were assessed at the same time point as the mental health and alcohol outcomes. Thus, we cannot infer causality when significant associations are detected.

College students are an important demographic to study, given that COVID-19 research has consistently shown young adults to be at significantly higher risk for increased anxiety and depression (Odriozola-González et al., 2020) and other COVID-19 related mental health impacts (Ozamiz-Etxebarria, Dosil-Santamaria, Picaza-Gorrochategui, & Idoiaga-Mondragon, 2020). Yet, there may be important differences between college students and their non-college peers, as well as non-college aged samples, that limit generalizability of the present study to all adults. Further, as distinct domains of impact of the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with mental health and substance use outcomes in college students during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, future studies should examine how these domains impact trajectories of symptoms across subsequent waves of the pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Spit for Science participants for making this study a success, as well as the many University faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project.

Funding Statement

Spit for Science has been supported by Virginia Commonwealth University [P20 AA017828, R37AA011408, K02AA018755, P50 AA022537, and F31AA025820] from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. The Spit for Science COVID survey was funded by VCU’s CCTR and Office of the Vice President for Research. Additional support from NIAAA [1K01AA028058-01].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

We intend to make the data available to any qualified investigator. Details regarding this process can be found here: https://spit4science.vcu.edu/collaborators/.

References

- Bartel, S. J., Sherry, S. B., & Stewart, S. H. (2020). Self-isolation: A significant contributor to cannabis use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Substance Abuse: Official Publication of the Association for Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1823550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. doi: 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bountress, K. E., Cusack, S. E., Conley, A. H., Aggen, S. H., Group, S. F. S. W., Vassileva, J., … Amstadter, A. B. (2021). Unpacking the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: Identifying structural domains. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1). doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.1932296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg, L. (2020). We’re not all in this together: On COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. American Journal of Public Health, 110(7), 917. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2020.305766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz, K. K., Cadoret, R., Cloninger, C. R., Dinwiddie, S. H., Hesselbrock, V. M., Nurnberger, J. I., Jr., … Schuckit, M. A. (1994). A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 55(2), 149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush, K., Kivlahan, D. R., McDonell, M. B., Fihn, S. D., & Bradley, K. A. (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale, S., Caponi, L., & Fioravanti, G. (2020). Metacognitions about problematic smartphone use: Development of a self-report measure. Addictive Behaviors, 109, 106484. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, W. E., McGinnis, E., Bai, Y., Adams, Z., Nardone, H., Devadanam, V., … Hudziak, J. J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health and wellness. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(1), 134–141.e132. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.08.466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuello-Garcia, C., Pérez-Gaxiola, G., & van Amelsvoort, L. (2020). Social media can have an impact on how we manage and investigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 127, 198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, M., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., … Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2020, June 24–30). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, D. A. (2000). US low-risk drinking guidelines: An examination of four alternatives. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(12), 1820–1829. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb01986.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino, C., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, D. J., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Ford, J. D., & Carter, A. (2020). The Epidemic–Pandemic Impacts Inventory (EPII). University of Connecticut School of Medicine. Retrieved from https://health.uconn.edu/psychiatry/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2020/05/EPII-Main-V1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, D. J., Briggs‐Gowan, M. J., Carter, A. S., Goldstein, B. L., & Ford, J. D. (2021). Profiling COVID‐related experiences in the United States with the epidemic‐pandemic impacts inventory: Linkages to psychosocial functioning. Brain and Behavior, 11(8), e02197. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley, D. F., & Saitz, R. (2020). The opioid epidemic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jama, 324(16), 1615–1617. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.18543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huckins, J. F., DaSilva, A. W., Wang, W., Hedlund, E., Rogers, C., Nepal, S. K., … Meyer, M. L. (2020). Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(6), e20185. doi: 10.2196/20185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy, Y., Nagarajan, R., Saya, G. K., & Menon, V. (2020). Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie, J. W., Lac, A., Kenney, S. R., & Mirza, T. (2011). Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors, 36(4), 354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marthoenis, M., Ilyas, A., Sofyan, H., & Schouler-Ocak, M. (2019). Prevalence, comorbidity and predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in adolescents following an earthquake. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 43, 154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S., Stillerman, L., & Waldo, M. (2005). Reliability and validity of the SCL-90-R with Hispanic college students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27(2), 254–264. doi: 10.1177/0739986305274911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, D. M., Miller, T. L., Smith, G. T., & Smith, J. A. (2001). Disinhibition and expectancy in risk for alcohol use: Comparing black and white college samples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(3), 313–321. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily, L. R., Okoro, C. A., Strine, T. W., Verlenden, J., Hollis, N. D., Njai, R., … Thomas, C. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70(5), 162. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas, K., & Stringaris, A. (2020). The Coronavirus Health Impact Survey (CRISIS) V0.3. National Institute of Mental Health. https://health.uconn.edu/psychiatry/child-and-adolescent-psychiatry-outpatient-clinic/family-adversity-and-resilience-research-program/epii/ [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaidis, A., Paksarian, D., Alexander, L., DeRosa, J., Dunn, J., Nielson, D. M., … Merikangas, K. R. (2020). The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. medRxiv. 2020.2008.2024.20181123. doi: 10.1101/2020.08.24.20181123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, R. C., Wetherall, K., Cleare, S., McClelland, H., Melson, A. J., Niedzwiedz, C. L., … Robb, K. A. (2020). Mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal analyses of adults in the UK COVID-19 mental health & wellbeing study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 1–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, Á., Irurtia, M. J., & de Luis-garcía, R. (2020). Psychological symptoms of the outbreak of the COVID-19 confinement in Spain. Journal of Health Psychology, 1359105320967086. doi: 10.1177/1359105320967086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Dosil-Santamaria, M., Picaza-Gorrochategui, M., & Idoiaga-Mondragon, N. (2020). Stress, anxiety, and depression levels in the initial stage of the COVID-19 outbreak in a population sample in the northern Spain [Niveles de estrés, ansiedad y depresión en la primera fase del brote del COVID-19 en una muestra recogida en el norte de España]. Cadernos de Saude Publica, 36(4), e00054020. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00054020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsali, M. E., Mousa, D. P. V., Papadopoulou, E. V., Papadopoulou, K. K., Kaparounaki, C. K., Diakogiannis, I., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2020). University students’ changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry research, 292, 113298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne-Sturges, D. C., Tjaden, A., Caldeira, K. M., Vincent, K. B., & Arria, A. M. (2018). Student hunger on campus: food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(2), 349–354. doi: 10.1177/0890117117719620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, M. S., Tucker, J. S., & Green, H. D. (2020). Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2022942–e2022942. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati, G., & Mancini, A. D. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychological Medicine, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E., & Daly, M. (2021). Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID‐19 crisis in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the Understanding America Study. British Journal of Health Psychology, 26(2), 570–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N., Hosseinian-Far, A., Jalali, R., Vaisi-Raygani, A., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., … Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, J. E., Thomas, N. S., Cho, S. B., Adkins, A., Kendler, K. S., & Dick, D. M. (2016). The role of romantic relationship status in pathways of risk for emerging adult alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(3), 335–344. doi: 10.1037/adb0000145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, R. M., Gillezeau, C. N., Liu, B., Lieberman-Cribbin, W., & Taioli, E. (2017). Longitudinal impact of Hurricane Sandy exposure on mental health symptoms. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(9), 957. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14090957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selden, T. M., & Berdahl, T. A. (2020). COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities in health risk, employment, and household composition. Health Affairs, 39(9), 1624–1632. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd, D. M., Deane, F. P., & McKenna, P. A. (1997). Appropriateness of SCL-90-R adolescent and adult norms for outpatient and nonoutpatient college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 44(3), 294–301. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.44.3.294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard, N., & Benros, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5). doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Hegde, S., Son, C., Keller, B., Smith, A., & Sasangohar, F. (2020). Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9), e22817. doi: 10.2196/22817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, H. R., Stevens, A. K., Hayes, K., & Jackson, K. M. (2020). Changes in alcohol consumption among college students due to COVID-19: Effects of campus closure and residential change. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 81(6), 725–730. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2020.81.725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarocostas, J. (2020). How to fight an infodemic. Lancet, 395(10225), 676. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30461-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We intend to make the data available to any qualified investigator. Details regarding this process can be found here: https://spit4science.vcu.edu/collaborators/.