Abstract

A total of 6,625 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clinical isolates obtained from 278 hospitals throughout Japan were obtained between November and December 1997 and were examined for their sensitivities to vancomycin using Mueller Hinton (MH), brain heart infusion (BHI), agar plates, or the broth microdilution method. A concentrated inoculum of an MRSA strain or the use of highly enriched medium, such as BHI medium, allows an individual cell to grow on agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration greater than the MIC for the parent strain. However, cells of the colonies which grew on BHI agar plates containing the higher vancomycin concentrations did not acquire a level of vancomycin resistance greater than that of the parent strain and were not subpopulations of heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA. There was no significance in the fact that these colonies grew on the higher concentration of vancomycin: none showed stable resistance to vancomycin at a concentration above the MIC for the parent strain, and no cell from these colonies showed a relationship between the MIC and the ability of these colonies to grow on higher concentrations of vancomycin. The vancomycin MIC was not above 2 μg/ml for any of the cells originating from these colonies. No Mu3-type heterogeneously resistant MRSA strains, which constitutively produce subpopulations from MRSA clinical isolates with intermediate vancomycin resistance at a high frequency, were detected. There was a unipolar distribution of the MICs ranging from 0.25 to 2 μg of vancomycin/ml among the 6,625 MRSA clinical isolates, indicating that there was no Mu50-type intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA (MIC, 8 μg/ml by National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards criteria) among the clinical isolates, and there was no evidence of dissemination of Mu3-type MRSA heteroresistant to vancomycin.

Vancomycin has been used for more than 30 years to treat gram-positive bacterial infections, especially methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections. In Japan, vancomycin injections have been used for the treatment of MRSA infections since November 1991, a shorter period of usage than in the United States and European countries. Nonetheless, the intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA strain Mu50 (vancomycin MIC, 8 μg/ml) and the heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA strain Mu3 (vancomycin MIC, 2 μg/ml) have been isolated from patients at Juntendo University Hospital in Japan (9, 10).

The Mu3 strain produced a subpopulation of cells of different but stable vancomycin resistance levels, with vancomycin MICs ranging from 4 to 8 μg/ml (i.e., the subpopulation for which the MIC is 8 μg/ml is the Mu50 strain), at the relatively high frequency of 10−4 to 10−6 in drug-free medium without vancomycin selective pressure (9). These results suggest why the intermediately vancomycin-resistant Mu50 strain was easily isolated from the patient's abscess during the early stage of vancomycin chemotherapy (9). The phenotype of the Mu50 strain has been characterized as being similar to that of the strain isolated by repeated in vitro exposure of the MRSA strain to vancomycin (8, 16).

Hiramatsu et al. have previously reported that the Mu3-type MRSA strains, which produce the vancomycin-resistant Mu50-type MRSA strain, are widely disseminated and account for 10 to 20% of the MRSA clinical isolates obtained from Japanese hospitals, and they suggested the need for special precautions to limit the global transmission of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) (9).

In this study, we conducted a nationwide survey to determine whether the Mu3 and Mu50-type strains, or any other strains with intermediate vancomycin resistance, are present in MRSA clinical isolates. This survey was carried out with the cooperation of microbiology specialists assigned to the hospital laboratories of each of the 278 hospitals. This is the first report of the surveillance, which was conducted by a group authorized by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and reagents.

A total of 6,625 MRSA clinical isolates were obtained from a total of 278 hospitals located in each prefecture, and also Hokkaido, Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo, between November and December 1997. The hospitals included 58 university hospitals and the major hospitals that have more than 500 beds in each area of Japan. Each strain was isolated from an infected specimen of a different patient. The media used in this study were MH broth, MH agar for the Sensitivity Disk agar-N (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan), MH agar for the sensitivity test (Eiken, Tokyo, Japan), BHI broth (Difco Laboratory, Detroit, Mich.), and Tripticase soy broth (BBL; Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems). S. aureus FDA209P (vancomycin MIC, 0.5 μg/ml), ATCC29213 (vancomycin MIC, 1 μg/ml), and ATCC25923 (vancomycin MIC, 2 μg/ml) were used as vancomycin-sensitive quality control strains throughout these studies. Mu50 (vancomycin MIC, 8 μg/ml) and Mu3 (vancomycin MIC, 2 μg/ml) were used throughout these studies (9). Vancomycin was kindly provided by Shionogi Co. (Osaka, Japan). Teicoplanin was kindly provided by Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd.

Vancomycin sensitivity.

Unless otherwise described, the vancomycin MIC was determined by the criteria of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) using MH agar (13, 13a). Overnight cultures of the strains grown in MH broth were diluted 100 times with fresh broth. One loopful (5 μl, about 5 × 103 to 1 × 104 CFU of bacterial cells) of each dilution was plated on agar plates containing drug. The MICs of vancomycin among MRSA strains using Nissui MH agar were compared to the MICs obtained with Eiken MH agar and were found to be identical. Therefore, only the MIC obtained with the Nissui MH agar is shown in this report. The MICs of the colonies that grew on the BHI agar plates when MH broth was used for isolate precultures were compared to the MICs obtained for colonies that had been precultured in Trypticase soy broth (9). There was no essential difference in the results obtained; therefore, the results obtained with MH broth for the isolate precultures after the initial screening are shown in this report.

Broth microdilution testing.

The vancomycin MICs for the clinical isolates were confirmed by the broth microdilution method on MIC panels (MicroScan, Pos combo Panel Type 3C worksheet; DADE BEHRING, West Sacramento, Calif.) according to NCCLS guidelines.

Screening of heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA.

After the initial screening of heterogeneously VRSA (hetero-VRSA), examination of hetero-VRSA was performed as follows: 5 μl (about 5 × 105 to ∼1 × 106 CFU of bacterial cells) of an overnight culture in MH broth was inoculated onto the BHI agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration of 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, or 32 μg/ml. The plates were incubated for 24 and 48 h at 35°C, and the colonies that grew on the plates were examined.

Population analysis.

Vancomycin sensitivity profiles of populations of MRSA strains (population analysis) were determined by previously described methods (9, 16). Appropriate dilutions of the overnight cultured strain (0.1 ml each) were inoculated onto BHI agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration of 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 16 μg/ml. The plates were incubated for 24 and 48 h at 35°C.

Initial screening of heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA Mu3-type strain.

The 278 hospitals were divided into 11 groups. The MRSA clinical isolates which were isolated from each hospital within any one of the 11 groups were transferred to the main hospital in that group. The initial screening for vancomycin-resistant MRSA strains was conducted at each main hospital. The 11 main hospitals examined a total of 6,625 clinical isolates. The agar plates used were BHI agar plates containing 1, 2, 3, or 4 μg of vancomycin/ml that had been made by Nissui. A sample of 106 or more bacterial cells was inoculated onto the agar plates (9), which were then incubated for 24 and 48 h at 35°C, as described previously (9). The data and all the clinical isolates were then transferred to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan. A total of 248 strains out of the 6,625 isolates were identified as giving rise to colonies on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml. These 248 strains were used as putative vancomycin heteroresistant MRSA Mu3-type strains in the population analysis of the following studies.

RESULTS

Screening of heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA Mu3-type strain.

If there is a Mu3-type strain among the clinical isolates, the strain should give rise to colonies of intermediately vancomycin-resistant cells at a frequency of 10−5 to 10−6 on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml, as described by Hiramatsu et al. (9), and the colonies should exhibit a vancomycin MIC greater than 4 μg/ml after repeated purifications on drug-free agar plates, because the subpopulations should exhibit stable but intermediate vancomycin resistance. As shown in Materials and Methods, 248 of a total of 6,625 strains gave rise to colonies on the BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml in the initial screening. The MIC of vancomycin for each of the 248 strains was determined to be ≤2 μg/ml by the agar dilution method with MH agar and broth microdilution methods.

We examined the 248 strains for their vancomycin sensitivity a total of five times using BHI agar plates containing different concentrations of vancomycin, as described in Materials and Methods. When approximately 106 bacterial cells were inoculated onto BHI agar plates containing vancomycin, strains gave rise to colonies on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml or more at frequencies of 4, 6, 12, 14, and 15% of the total 248 strains for each experiment. Colonies that grew on BHI agar plates containing the higher concentrations of vancomycin were purified three times on drug-free agar plates, and after purification the MIC of each colony was found to be ≦2 μg/ml on MH agar plates.

Population analysis was performed three times on the 248 isolates. When approximately 5 × 107 bacterial cells were inoculated onto BHI agar plates containing vancomycin, strains gave rise to colonies on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml or more. All of the strains grew on BHI agar plates containing ≤4 μg of vancomycin/ml at a frequency of ≥10−7 per bacterial inoculum. Of the 248 strains, 151 strains (61%) grew on BHI agar plates containing 6 and 8 μg of vancomycin/ml at frequencies between 10−6 and 10−7 per bacterial inoculum, and 27 strains (11%) grew on BHI agar plate containing 6 μg of vancomycin/ml at frequencies between 10−6 and 10−7 per bacterial inoculum. In each experiment, colonies grew on BHI agar plates containing 6 or 8 μg of vancomycin/ml were purified three times on drug-free agar plates, and the MICs for each of the colonies was determined to be ≤2 μg/ml by the NCCLS criteria with MH agar.

Of the 6,625 MRSA strains, 6,377 strains (96.3%) did not give rise to any colonies on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml in the first screening. Of the 6,377 strains, two strains were selected at random from the strains isolated from each of the 150 hospitals, and a total of 300 strains were examined a total of five times for their vancomycin resistance levels by examination of hetero-VRSA, as described in Materials and Methods. The MIC of vancomycin for each of the 300 strains was determined to be ≦2 μg/ml by the agar dilution method with the MH agar and broth microdilution method. Although the 300 strains did not give rise to colonies on BHI agar plates containing vancomycin at a concentration of 4 μg/ml in the first screening, the strains gave rise to colonies on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg or more of vancomycin/ml at frequencies of 5, 9, 12, 14, and 14% of the total 300 strains for each experiment. In each experiment, the colonies that grew on BHI agar plates containing the higher concentrations of vancomycin were purified three times on drug-free agar plates, and the vancomycin MIC for each colony after purification was found to be ≦2 μg/ml on MH agar plates.

Of the 300 strains, 30 strains were selected from different hospitals and were used for the population analysis. When about 5 × 107 bacterial cells were inoculated on BHI agar plates containing different concentrations of vancomycin, of the 30 strains, 8 (27%) strains grew on the BHI agar plates containing ≦6 μg of vancomycin/ml at frequencies between 10−7 to 10−6 per inoculum bacteria, and 12 (40%) strains grew on the BHI agar plates containing ≦8 μg of vancomycin/ml at frequencies of about 10−7 to 10−6 per inoculum bacteria. In each experiment, colonies that grew on BHI agar plates containing 6 or 8 μg of vancomycin/ml were purified three times, and the MIC for each of the colonies was determined to be ≦2 μg/ml by the NCCLS criteria with MH agar.

Population analyses of the Mu3 strain were also performed more than 10 times, as described in Materials and Methods. The Mu3 strain also grew on BHI agar plates containing 8 μg of vancomycin/ml at a frequency of about 10−6 per bacterial inoculum, and the vancomycin MIC for the colonies was 2 μg/ml after three purifications. The intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulation (Mu50; vancomycin MIC, 8 μg/ml) was never isolated in these population analyses.

Restriction endonuclease digestion patterns of S. aureus chromosomal DNA.

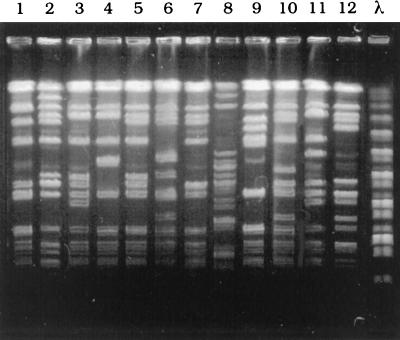

As described in Materials and Methods, the 248 strains were used as putative vancomycin-heteroresistant MRSA based on the initial screening. The 248 strains were derived from 78 different hospitals. One strain from each of the 78 hospitals was randomly selected in order to compare the strains by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. SmaI restriction endonuclease digestion patterns of the chromosomal DNAs of the 78 strain showed 67 different patterns. Of the 78 strains, five groups comprising 2 strains each, one group of 3 strains, and one group of 5 strains, each of 2 strains of the 10 strains, 3 strains, and 5 strains showed the identical patterns, respectively. There is no pattern identical to that of Mu3 or Mu50 strains with respect to the restriction endonuclease digestion pattern of the chromosomal DNA (9), indicating that there is no dissemination of Mu3- and Mu50-type strains in Japanese hospitals. Representative results of the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNAs were shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNAs isolated from MRSA strains. Lane 1, Mu3 strain. Lane 2 to lane 12, MRSA strains isolated from different hospitals. λ, a bacteriophage λ DNA ladder used as a molecular size marker.

Effects of inoculum size and medium on sensitivities to vancomycin.

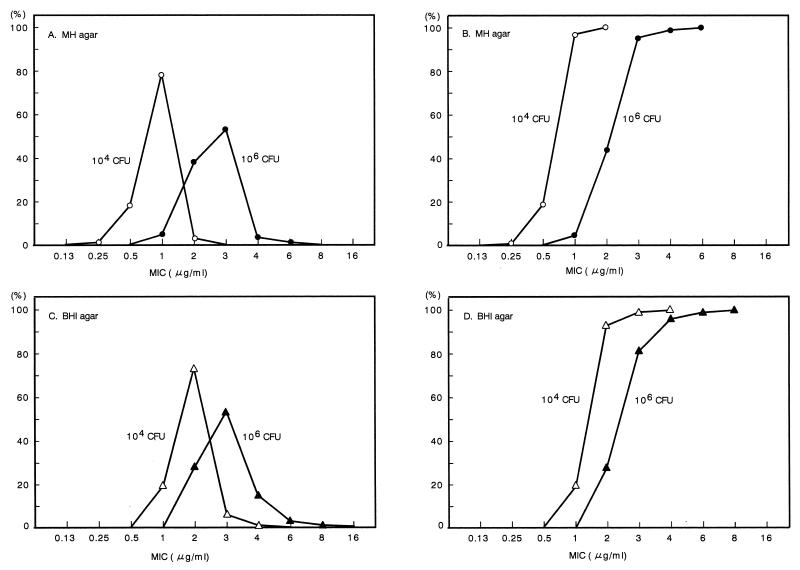

Five MRSA strains from each of 40 hospitals were selected at random to test their sensitivities to vancomycin on MH agar and BHI agar. Approximately 104 and 106 bacterial cells were inoculated on the vancomycin-containing agar plates. As shown in Fig. 2, the distributions of vancomycin MICs increased in proportion to the increase in the number of bacterial cells which were inoculated onto the Mueller Hinton or BHI agar plates containing vancomycin. The distribution of the MICs among the MRSA strains grown on BHI agar plates indicated a higher level of resistance than for those grown on MH agar (Fig. 2). When approximately 106 cells were inoculated onto the BHI agar plates, 11 strains (5.5%) and 1 strain (0.5%) gave rise to colonies on agar plates containing vancomycin concentrations of 4 and 6 μg/ml, respectively. After three rounds of purification, the vancomycin MICs for colonies that had been grown on agar plates containing more than 4 μg of vancomycin/ml were determined to be 1 or 2 μg/ml, which were identical to those for the parent strains. We examined the sensitivities to vancomycin of the 200 MRSA strains a total of three times. When about 106 cells were inoculated onto BHI agar plates containing vancomycin, the strains which gave rise to colonies on the BHI agar plates containing more than 4 μg of vancomycin/ml varied in each experiment, indicating that the strains were not specific MRSA strains (data not shown). These results confirmed that MRSA could give rise to colonies on agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration above the MICs for the parent strains, but the MICs for the resulting colonies were identical to those for the parent strains, as shown by NCCLS criteria.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of vancomycin MICs among MRSA strains in different inoculums and in different mediums. Five strains were selected at random from each of 40 hospitals, and a total of 200 strains were examined for vancomycin MICs by inoculating approximately 104 or 106 bacterial cells onto agar plates containing the vancomycin concentrations indicated in the figure. The media used for the agar plates were MH agar and BHI agar. (A and B) MIC distribution and the cumulative MIC distribution with MH agar, respectively. (C and D) MIC distribution and the cumulative MIC distribution with BHI agar, respectively. Symbols, ○ and ▵, 104 inoculum; ● and ▴, 106 inoculum. CFU, CFU of bacterial cells. A 5-μl aliquot of overnight culture was used as the 106 inoculum. Overnight cultures were 100-fold diluted, and 5 μl of each dilution was used as the 104 inoculum. After the bacterial cells were inoculated onto the agar plates, the plates were incubated for 24 h at 35°C. Numbers at left indicate percentages of strains.

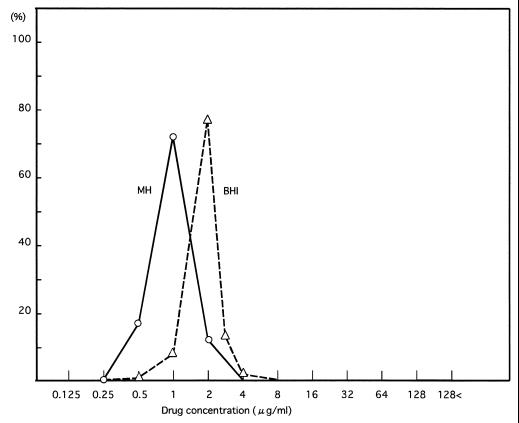

Distribution of vancomycin MICs among the 6,625 MRSA isolates.

The vancomycin resistance levels of the 6,625 MRSA isolates were examined by NCCLS criteria and also by using BHI agar plates. There was a unipolar distribution of the MICs for these strains (Fig. 3). The MICs for these strains ranged from 0.25 to 2 μg/ml, and no intermediately resistant strain was isolated. The MICs for 6 strains (0.1%), 1,097 strains (16.5%), 4,744 strains (71.6%) and 778 strains (11.7%) were 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg/ml, respectively. When we used BHI agar plates, the MICs for these strains ranged from 0.5 to 4 μg/ml, indicating a shift to greater resistance levels than those obtained with MH agar. The 6,625 MRSA isolates examined in this study were isolated between November and December 1997. Since then, there has been no report of isolation of intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA from any Japanese hospital to the National Institute of Infectious Disease of Japan in National Surveillance conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

FIG. 3.

Vancomycin MIC distributions in MRSA clinical isolates. The vancomycin MICs of the 6,625 clinical isolates were examined by NCCLS methods with MH agar and BHI agar. About 104 bacterial cells were inoculated onto agar plates containing different concentrations of vancomycin, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 35°C. Symbols: ○, MIC distribution with MH agar. ▵, MIC distribution with BHI agar. Numbers at left indicate percentages of strains.

The MIC of teicoplanin for the Mu50 strain is 16 μg/ml (9). To examine the teicoplanin sensitivities of the MRSA clinical isolates, 5 MRSA strains from each of the 278 hospitals in the study were selected at random, and a total of 1,390 strains were tested for teicoplanin sensitivity on MH agar by the NCCLS criteria. The MICs for 28 strains (2%), 247 strains (17.8%), 570 strains (41%), 452 strains (32.5%), 73 strains (5.3%), 16 strains (1.1%) and 4 strains (0.3%) were 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 μg/ml, respectively. No strain expressed teicoplanin resistance at a level of 16 μg/ml for the MIC. Sixteen (1.1%) and four (0.3%) strains expressed teicoplanin resistance levels of 4 and 8 μg/ml, respectively. The MICs of vancomycin for these 20 strains were determined to be ≦2 μg/ml using the broth microdilution method. These results indicate that there was no correlation between the vancomycin resistance level and the teicoplanin resistance level in these clinical isolates.

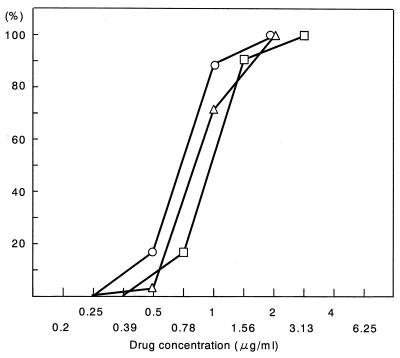

The distribution of the MICs was compared with the reported data of the distributions of the MICs for MRSA strains that had been reported in 1991, prior to the use of vancomycin injections in Japan (19). The distribution of MICs for vancomycin did not differ from the reports of 1991 (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Comparison of the distribution of vancomycin MICs of MRSA clinical isolates between clinical isolates obtained before 1991 and in 1997. Symbols: ○, 6,625 isolates in 1997 (in this study); ▵, 77 isolates obtained before 1991 from the Chiba University Hospitals, Chiba, Japan (19); □, 54 isolates before 1991 Tokyo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan (19). Numbers at left indicate percentages of strains.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that there is no vancomycin-heteroresistant Mu3-type strain that produces a subpopulation of cells with stable vancomycin resistance, with MICs above those of the parent strain, among Japanese MRSA clinical isolates. Also, there is no intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA Mu50-type strain or other intermediately vancomycin-resistant strain among these strains. In this study, we showed that when a concentrated inoculum (i.e., more than 5 × 105 CFU of bacterial cells) of MRSA strain was inoculated onto a BHI agar plate containing vancomycin, it was possible for a strain to give rise to colonies by chance which then grew on agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration above the MIC for the parent strain. However, the cells of the colonies which grew on the BHI agar plates containing the higher vancomycin concentrations did not acquire a level of vancomycin resistance greater than that of the parent strain. There was no significance in the fact that these colonies grew on the higher concentration of vancomycin: none was stably resistant to vancomycin at a concentration above the MIC for the parent strain, and no cell from these colonies showed a relationship between the MIC and the presence of colonies growing on higher concentrations of vancomycin. No colony produced cells that had a vancomycin MIC above 2 μg/ml. While there were 248 isolates out of a total of 6,625 isolates that were initially detected by screening the subpopulation that had given rise to colonies that grew on BHI agar plates containing 4 μg of vancomycin/ml when a sample of 106 or more bacterial cells was inoculated onto the selective agar, colonies that grew on higher concentrations of vancomycin could be detected in virtually any isolate if the test or population analysis was repeated a number of times and the initial 248 isolates were not specific strains.

Our results also indicated that it was possible for a cell within the MRSA strain population to grow adaptively on the vancomycin agar plates. As vancomycin binds to the peptidoglycan precursor, the bacterial growth-inhibitory activity of vancomycin could be affected by the size of the bacterial inoculum and the nutritive value of the agar plate, similar to the β-lactam antibiotics. Recently similar results with MH agar plates have been reported by Hubert et al. (11). They also showed by population analysis that the colonies grown on BHI agar plates containing a higher concentration of vancomycin do not acquire the higher levels of resistance (11).

When a vancomycin-sensitive MRSA strain gives rise to a colony on agar plates containing a vancomycin concentration above the MICs for the parent strain, there are two possibilities as to the character of the colony. As shown in this report, one is the result of adaptation of a bacterial cell to the vancomycin. The other is the result of selection for intermediately vancomycin-resistant cells in a subpopulation of the vancomycin-heteroresistant strain, as shown by Hiramatsu et al. (9). There are a few reports of the isolation of heterogeneously resistant MRSA (1, 9). To examine the heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA, an excessively large number of bacterial cells are usually inoculated onto agar plates containing vancomycin, and population analyses for the detection of the intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulations of the heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA are usually performed according to the method of Hiramatsu et al. (9). However, as we have shown in this report and as Hubert et al. (11) have recently reported, the colonies which grow on the agar plates are not subpopulations of the heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA. It is essential to confirm whether the isolates are heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA, such as the Mu3 strain, and necessary to develop methods to examine heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA, such as the Mu3 strain.

In standard methods used in bacterial genetics or for the isolation of a drug-resistant mutant (or subpopulation) from a bacterial strain in vitro (3, 4, 7), an isolate which initially grows on a selective agar plate containing a drug should be purified several times on agar plates without the selective drug prior to the confirmatory test (3, 4, 7, 11). If an isolate which initially grows on the selective agar plates is selected repeatedly on selective medium, the phenotypes or genotype of the resulting strain is different in each experiment (3), and the resulting strain is not a drug-resistant mutant or a subpopulation with a single mutation that was already present in the broth culture of a strain (parent strain) in the absence of the selective environment prior to inoculation of the culture on initial selective agar. In this case, the strain is a drug-resistant derivative that is derived from the colony that initially grows on the selective agar plates, and the possibility remains that the strain has multiple mutations resulting from repeated selective pressure in vitro. In the case of intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA in particular, the specific determinant which is associated with intermediate vancomycin resistance is not known (2). Thus, it is highly possible that the intermediately vancomycin-resistant strain obtained by repeated culturing, on agar plates containing vancomycin, of an isolate which initially grows on a selective agar plate, is not an intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulation resulting from a mutation of a progeny cell of an MRSA strain that has been cultured in the absence of a selective environment in broth but is a derivative with multiple mutations derived from a phenotypic variant of an MRSA strain that initially grows adaptively on an agar plate containing higher concentration of vancomycin. For the same reason, when we isolate intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA from a clinical specimen obtained from a patient, we should not culture the isolate or specimen in the presence of the selective environment containing vancomycin prior to the confirmatory test, otherwise we would not be able to determine whether the isolate is derived from the clinical specimen or from in vitro mutations. Although many of the reports describing isolation of intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA do not describe details of the isolation procedures in the laboratories, there is a report that describe the isolation procedures (12). However, it seems that the intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA for which the vancomycin MIC was 8 μg/ml was not isolated directly from the clinical specimen but was selected in vitro from the culture of a MRSA isolate with a vancomycin MIC of 4 μg/ml in the medium containing vancomycin (12). Another recent report also indicates these problems (18).

Boyle-Vavra et al. (2) have recently reported the results of detailed analysis of the peptidoglycan composition of several glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (GISA) isolates and have indicated that a single genetic or biochemical change is unlikely to account for the glycopeptide resistance phenotype in the clinical GISA isolates. Another recent report concerning Mu50 shows that there is a correlation between the increased vancomycin resistance and several metabolic changes for peptidoglycan synthesis in Mu50 (6). It seems that Mu50 might be a strain with multiple mutations that was selected by repeated and prolonged culturing in the presence of a selective environment of vancomycin in vitro. These results confused us as to whether Mu50 is a subpopulation of naturally occurring intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA (9).

To our knowledge, Mu3 is the only heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA strain in the world that produces stable intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulations. However, we have never isolated an intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulation (i.e., Mu50; MIC, 8 μg/ml) from Mu3 (18). Mu3, which is susceptible to vancomycin (MIC, 2 μg/ml) by NCCLS criteria, is unique in that the strain produces a subpopulation of cells of different but stable resistance phenotypes, with vancomycin MICs ranging from 4 to 8 μg/ml at a 1-μg/ml incremental increase in vancomycin-free medium in vitro at a frequency of 10−6 or more by random mutation (9). The report of Hiramatsu et al. (9) has influenced the clinical environment worldwide, and various documents describing the heterogeneously vancomycin-resistant MRSA (Mu3) and intermediately vancomycin-resistant S. aureus refer to this report (9). However, the data reported by Hiramatsu et al. (9) are controversial from a biological, methodological, and epidemiological point of view. It is not known why cells with a resistance to 8 μg of vancomycin/ml cannot be selected on agar plates containing less than 8 μg of vancomycin/ml. It is not known why BHI agar is used to test vancomycin resistance levels and why an extremely large number of bacterial cells (5 × 105) were inoculated to test the vancomycin resistance level of cells belonging to a subpopulation of the Mu3 strain (9). We usually use 3.5 × 103 to 1 × 104 cells and MH agar for determining MICs (13, 13a). There is no comparative study of the MICs obtained with BHI agar and MH agar (9). The vancomycin MICs for a MRSA strain with MH agar were not the same as the MICs obtained with BHI agar, as shown in this study. BHI medium is not an adequate medium for the testing of antibiotic MICs. If the naturally occurring Mu3-type strains are widely disseminated throughout Japanese hospitals, as reported by Hiramatsu et al. (9), and the Mu3-type strain gives rise to the intermediately vancomycin-resistant subpopulations at a high frequency (i.e., ≧10−6) in the patient (in vivo), the amount of the Mu50 type or another intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA strain would be selectively increased in the clinical environment and should be easily identified from among the clinical isolates. However, since the 1997 report, there has been no report describing such strains sent from any Japanese hospital to the National Institute of Infectious Diseases of Japan in the National Surveillance conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Our investigations have shown that the MICs of all the clinical isolates ranged from 0.25 to 2 μg/ml and that the MIC distribution did not differ from that reported in 1991 (19), indicating that there was no Mu50 type of strain or other intermediately vancomycin-resistant strain present among the clinical isolates in Japan and that there was no dissemination of the Mu3-type strain among the clinical isolates.

To date, the isolation of six intermediately glycopeptide-resistant S. aureus strains from patients has been reported in the United States and Japan (5, 10, 14, 15, 17). A comparative study of four intermediately glycopeptide-resistant S. aureus infections, including three isolates in United States, and the Mu50 strain have been reported (17). We do not know whether the other three strains isolated in the United States arose by mutation of the Mu3-type strain, like the Mu50-type strain (9, 10). The Mu50-type strain should be easily isolated from patients infected with the Mu3-type strain (9), because the Mu50-type strain is a subpopulation of Mu3-type strain. The backgrounds of patients from whom the intermediately vancomycin-resistant MRSA strains were isolated were completely different from those of patients who had Mu50 and the other three isolates in the United States (10, 17). The Mu50 strain was isolated from the pus of a postoperative wound infection of an infant patient after a relatively short period of vancomycin chemotherapy (10). The other three strains were isolated from old patients who received repeated and prolonged vancomycin chemotherapy and received long-term or temporary dialysis (17). These strains are similar to the vancomycin resistance derivatives of MRSA that are isolated by prolonged exposure of MRSA to vancomycin in vitro (16). These suggest that intermediately glycopeptide-resistant S. aureus may be isolated from patients who undertake long-term vancomycin chemotherapy for MRSA infection, and monitoring for colonization or infection with S. aureus with intermediate glycopeptide resistance may be warranted among patients who are often treated with vancomycin (17). However, if the Mu3-type strain occurs naturally, it would be hard to prevent the dissemination of the vancomycin-resistant Mu50-type strain within the clinical environment. Our investigation showed that there is no evidence of a naturally occurring Mu3-type strain or Mu50-type strain, and there is no dissemination of any Mu3-type strain and Mu50-type strain. A recent report has shown that intermediate vancomycin resistance among MRSA strains is not a widespread problem in the United States (11).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

We thank all members of the glycopeptide-intermediate S. aureus working group in the clinical laboratories of the 278 hospitals throughout Japan who contributed to this study and the Japanese Association of Medical Technologists. We thank Elizabeth Kamei, Don B. Clewell, Masanosuke Yoshikawa, Masatoshi Konno, Hajime Hashimoto, Kihachiro Shimizu, and Fred Tenover for their helpful advice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ariza J, Pujol M, Cabo J, Pena C, Fernandez N, Linares J, Ayats J, Gudiol F. Vancomycin in surgical infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin. Lancet. 1999;353:1587–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle-Vavra S, Labischinski H, Ebert C C, Ehlert K, Daum R S. A spectrum of changes occurs in peptidoglycan composition of glycopeptide-intermediate clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:280–287. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.1.280-287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun W. Bacterial genetics. W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Company; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalli-Sforza L L, Lederberg J. Isolation of pre-adaptive mutants in bacteria by sib selection. Genetics. 1956;41:367–381. doi: 10.1093/genetics/41.3.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin—Illinois. 1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;48:1165–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui L, Murakami H, Kuwahara-Arai K, Hanaki H, Hiramatsu K. Contribution of a thickened cell wall and its glutamine nonamidated component to the vancomycin resistance expressed by Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demerec M. Origin of bacterial resistance to antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1948;56:63–74. doi: 10.1128/jb.56.1.63-74.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanaki H, Kuwahara-Arai K, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum R S, Labischinski H, Hiramatsu K. Activated cell-wall synthesis is associated with vancomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strains Mu3 and Mu50. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:199–209. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiramatsu K, Aritaka N, Hanaki H, Kawasaki S, Hosoda Y, Hori S, Fukuchi Y, Kobayashi I. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet. 1997;350:1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover F C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:135–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hubert S K, Mohammed J M, Fridkin S K, Gaynes R P, McGowan J E, Jr, Tenover F C. Glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus: evaluation of a novel screening method and results of a survey of selected U.S. hospitals. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3590–3593. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3590-3593.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marlowe E M, Cohen M D, Hindler J F, Ward K W, Bruckner D A. Practical strategies for detecting and confirming vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus: a tertiary-care hospital laboratory's experience. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2637–2639. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2637-2639.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13a.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7–A4. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotun S S, McMath V, Schoonmaker D J, Maupin P S, Tenover F C, Hill B C, Ackman D M. Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin isolated from a patient with fatal bacteremia. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:141–149. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieradzki K, Roberts R B, Haber S W, Tomasz A. The development of vancomycin resistance in a patient with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:517–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sieradzki K, Tomasz A. Inhibition of cell wall turnover and autolysis by vancomycin in a highly vancomycin-resistant mutant of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2557–2566. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2557-2566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith T L, Pearson M L, Wilcox K R, Cruz C, Lancaster M V, Robinson-Dunn B, Tenover F C, Zervos M J, Band J D, White E, Jarvis W R. The glycopeptide-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus working group. Emergence of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:493–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tenover F C, Biddle J W, Lancaster M V. Increasing resistance to vancomycin and other glycopeptides in Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:327–332. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi K. Proceedings of vancomycin symposium. Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan: The 38th Eastern Chapter of Japanese Society of Chemotherapy; 1991. Antibacterial activity of vancomycin; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]