Abstract

Introduction:

In 2013, we implemented a pill-based, multi-modal pain regimen (MMPR) in order to decrease in-hospital opioid exposure after injury at our trauma center. We hypothesized that the MMPR would decrease inpatient oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME), decrease opioid prescriptions at discharge, and result in similar Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) pain scores.

Methods:

Adult patients admitted to a level-1 trauma center with ≥1 rib fracture from 2010–2017 were included – spanning 3 years before and 4 years after MMPR implementation. MME were summarized as medians and interquartile range (IQR) by year of admission. The effect of the MMPR on daily total MME was estimated using Bayesian generalized linear model.

Results:

Over the 8 year study period, 6,933 patients who met study inclusion criteria were included. No significant differences between years were observed in Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) Chest or Injury Severity Scores (ISS). After introduction of the MMPR, there was a significant reduction in median total MME administered per patient day from 60 MME/ patient day (IQR 36–91 MME/patient day) pre-MMPR implementation to 37 MME/patient day (IQR 18–61 MME/patient day) in 2017, p <0.01. Total MME administered per patient day decreased by 31% in 2017 as compared to 2010 (rate ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.64 – 0.75). Average NRS pain scores decreased by 0.8 points (95% CI −0.87, −0.81) from 2010 to 2017.

Conclusion:

The introduction of a multi-modal pain regimen resulted in significant reduction in in-patient opioid exposure after injury. The reduction in inpatient opioid use from 2010 to 2017 was equivalent to 11 mg less oxycodone or 17 mg less hydrocodone per patient per day. Additionally, use of the MMPR was associated with a reduction in NRS pain scores.

Keywords: Multi-modal pain regimen, opioid, pain management, trauma

Introduction

Drug overdose deaths are now the leading cause of death in the U.S. for those under 50 years of age.1 In 2017, drug overdose deaths in the United States were 33% higher than in 2015, with approximately two-thirds of the culpable drugs being opioids.2 Of patients seeking treatment for heroin addication, 75% had their first exposure to opioids via prescription.3 In 2014, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared prescription drug overdose to be in the top five health threats.4 Opioid abusers are estimated to cost $15,000 more per person in healthcare expenditure and $50 billion more per year in societal costs in the United States.5 Opioid exposure during healthcare interactions appears to have been and continues to be a major driver of the current opioid epidemic.6

Historically, opioids have served as the mainstay of acute pain management in injured patients. In contrast to enhanced recorvery after major elective surgery or surgery on an isolated area of the body, trauma patients often have multi-system injury, precluding the widespread use of regional anesthesia.7 In 2013, our U.S. Level 1 trauma center implemented a pill-based, multi-modal pain regimen (MMPR) with the primary aim of decreasing opioid use while still providing adequate pain control. The MMPR consisted of scheduled non-opioid pain medications as first-line agents, supplemented with opioids as needed.

The purpose of this study was to quantify the effect of the MMPR on in-patient opioid exposure, discharge opioid prescribing, and self-reported Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) pain scores. We hypothesized that the MMPR would be associated with decreased inpatient oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per patient day, decreased opioid prescriptions at discharge, and similar NRS pain scores.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, we performed a retrospective cohort study of adult patients admitted to the Red Duke Trauma Institute (RDTI) at Memorial Hermann Hospital-Texas Medical Center from from 2010 to 2017. The RDTI is an American College of Surgeons-verified Level 1 trauma center located in Houston, Texas and is the primary teaching hospital for the McGovern Medical School at UT Health.

The trauma registry was queried for all adult patients (≥16 years) with at least 1 rib fracture who were admitted to the RDTI during the study period. The inclusion of only patients with at least 1 rib fracture was a decision made a priori to allow for both a feasible number of patients for whom to gather data and to have a large enough sample to obtain an accurate estimate of opioid exposure. The 8-year study timeframe was divided into a pre-MMPR (2010 – 2012) period, during MMPR implementation (2013), and individual post-MMPR years (2014, 2015, 2016, 2017).

The MMPR consisted of the following medications ordered in a scheduled fashion such that they were given around the clock without the patient having to request them: acetaminophen (24 hours of intravenous acetaminophen followed by oral acetaminophen), gabapentinoids (48 hours of pregabalin followed by gabapentin), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs (48 hours of celecoxib followed by naproxen)], lidocaine patches, and tramadol (MME factor of 0.1). This regimen was supplemented with stronger opioids given on an as needed basis. The MMPR acted as a starting point; the inpatient pain medication regimen was evaluated during daily rounds and adjusted according to the patient’s pain level, the type of pain described, and the ability to mobilize. Patients were weaned to a regimen which allowed for the lowest amount of opioid to be used to adequately treat pain. At discharge, patients were given prescriptions for the MMPR medications and an opioid if needed.

Baseline patient demographics, Injury Severity Score (ISS), regional Abbreviated Injury Scales (AIS), adverse events (including ileus, cardiac arrest, unplanned intensive care unit admission, unplanned intubation, and death), hospital lengths of stay and discharge opioid prescriptions were collected by chart review or via the trauma registry. Inpatient opioid use and NRS pain scores were collected by querying electronic medical records. Opioids were converted to oral MME based on best available evidence.8 MME/patient day were summarized as medians and interquartile range (IQR) by year of admission.

The amounts of medications given during anesthesia, via continuous intravenous infusions, and by patient-controlled analgesia were unavailable in the older years of the study, so all opioids given by these methods were not evaluated in this study. Hence, the MME/day values reported in this study are conservative estimates. Additionally, only NRS pain scores are reported. NRS pain scores measure a patient’s self-reported pain on a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 being no pain and 10 being the most severe pain. At our institution, patients who cannot verbalize a NRS pain scale score are assessed using the Behavioral Pain Scale, a three dimensional scale with a score that can range from 3 to 12. Since these two pain scales cannot be converted to one equivalent pain measurement, we only report the NRS pain scale scores in this study and do not report any Behavioral Pain Scale values.

MME/patient day was calculated by dividing the total MME given during a patient’s hospital stay by the number of hospital days. Average NRS pain scores for each patient were calculated by adding all recorded pain scores and dividing by the number of measurements taken. Univariate analysis was performed using Chi-squared and Kruskal-Wallis tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Bayesian negative binomial regression was used to model total MME per patient day as a function of unit of admission with year as a categorical variable. Bayesian linear regression model was used to examine the relationship between averaged NRS pain scores and year while adjusting for unit of admission. We used vague neutral priors ~Normal (0,1000) for the intercept and all coefficients. We fitted each model with four Markov chains including 2000 warmups and 10,000 iterations per chain. We reported mean and 95% credible interval for the estimates. Bayesian methods were utilized because they provide the probability that the true treatment effect lies within a specified range. This allows the incorporation of uncertainty into our probability estimates and provides clinicians with a clinically applicable outcome. This is in contrast to null hypothesis significance testing (e.g. odds ratios and p-values) which treat outcomes as dichotomous – significant or not significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.0 (College Station, Texas), R v3.4.1 and Stan v2.18.1 using the brms package.

Results

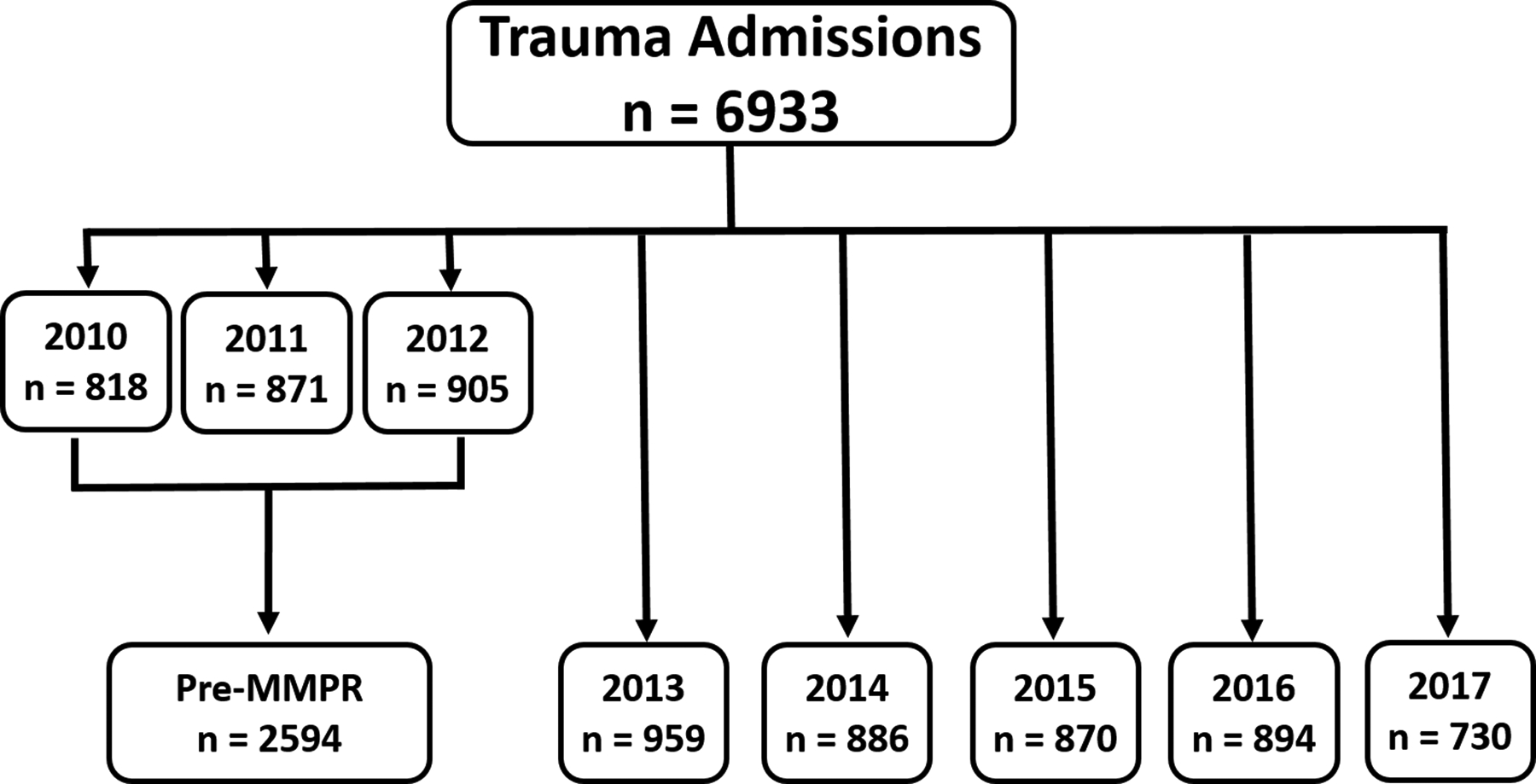

Over the 8-year study period, 6,933 patients with ≥1 rib fracture were admitted to the RDTI, 2,594 (37%) pre-MMPR (2010 – 2012), 959 (14%) during MMRP implementation (2013), and 3,380 (49%) post-MMPR implementation (2014 – 2017) (Figure).

Figure:

Trauma admission pre- and post-MMPR from 2010 to 2017. MMPR was implemented in 2013.

No significant differences in the proportion of male patients (71%), injury severity (ISS 18, IQR 13 – 27), or AIS Chest (3, IQR 3 – 3) were observed over the study period (Table 1). Patients were significantly younger, were more likely to be non-Hispanic Caucasian, suffered blunt injury, and were admitted to the intermediate monitoring unit (IMU) in the pre-MMPR period as compared to during and post-MMPR implementation.

Table 1:

Patient Demographics Pre- and Post-Multi Modal Pain Regimen (MMPR)

| Median (IQR) | All (n = 6933) |

Pre-MMPR (n = 2594) |

2013 (n = 959) |

2014 (n = 886) |

2015 (n = 870) |

2016 (n = 894) |

2017 (n = 730) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 47 (31 – 60) | 46 (31 – 59) | 46 (31 – 59) | 47 (31 – 61) | 48 (31 – 62) | 48 (32 – 62) | 48 (33 – 62) | 0.0022 |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 4926 (71%) | 1890 (73%) | 653 (68%) | 609 (69%) | 623 (72%) | 632 (71%) | 519 (71%) | 0.057 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| ISS | 18 (13 – 27) | 18 (14 – 27) | 18 (14 – 27) | 17 (13 – 26) | 17 (13 – 25) | 17 (13 – 25) | 18 (13 – 29) | 0.0895 |

| ISS > 15, n (%) | 4339 (63%) | 1644 (63%) | 612 (64%) | 540 (61%) | 539 (62%) | 544 (61%) | 460 (63%) | 0.596 |

| AIS Chest | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 3 (3 – 3) | 0.5416 |

| AIS Chest > 3, n (%) | 5455 (77%) | 2058 (79%) | 745 (78%) | 693 (78%) | 682 (78%) | 700 (78%) | 577 (79%) | 0.910 |

| Blunt Injury, n(%) | 6580 (95%) | 2505 (97%) | 908 (95%) | 828 (93%) | 811 (93%) | 838 (94%) | 690 (95%) | <0.001 |

| Unit of Admission |

ISS = injury severity score; AIS = abbreviated injury scale; ICU = intensive care unit; IMU = intermediate monitoring unit

Recorded adverse events were infrequent (Appendix A). There were no differences in diagnoses of ileus (5% pre-MMPR versus 6% in 2017, p = 0.5), cardiac arrest (3% pre-MMPR versus 1% in 2017, p = 0.1), or death (6% pre-MMPR versus 7% in 2017, p = 0.8) during the study period. Unplanned intubations decreased (3% pre-MMPR versus 2% in 2017, p < 0.001) while unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) admissions increased (<1% pre-MMPR versus 4% in 2017, p < 0.001). There was also an increase in hospital-free days (22, IQR 14 – 27 days pre-MMPR versus 24, IQR 15 – 27 days in 2017, p = 0.002) and ventilator-free days (30, IQR 27 – 30 days pre-MMPR versus 30, IQR 29 – 30 days in 2017, p = 0.04) and no change in ICU-free days (29, IQR 23 – 30 days pre-MMPR versus 30, IQR 26 – 30 days in 2017, p = 0.45). Median average pain scores significantly decreased after MMPR implementation (4.5, IQR 3.2 – 5.8 points pre-MMPR versus 3.5, IQR 1.8 – 4.7 points in 2017, p < 0.001).

After introduction of the MMPR in 2013, there was a significant reduction in median total MME administered per patient day from 60 MME/patient day (IQR 36 – 91 MME/patient day) in pre-MMPR period to 37 MME/patient day (IQR 18 – 61 MME/patient day) in 2017, p <0.001. The use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) significantly decreased from 10% in pre-MMPR period to 2% in 2017 (p < 0.001). The use of regional anesthetics remained constant during the 8-year study period (Table 2). Inpatient non-opioid pain medication use revealed an increase in use of lidocaine patches, acetaminophen, and NSAIDs, while the use of gabapentinoids remained the same pre- and post-MMPR implementation (Table 3).

Table 2:

Inpatient Opioid Use Pre- and Post-Multi Modal Pain Regimen (MMPR)

| Median (IQR) | All (n = 6933) |

Pre-MMPR (n = 2594) |

2013 (n = 959) |

2014 (n = 886) |

2015 (n = 870) |

2016 (n = 894) |

2017 (n = 730) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MME/patient day | ||||||||

| PCA, n (%) | 609 (9%) | 263 (10%) | 182 (19%) | 75 (8%) | 44 (5%) | 31 (3%) | 14 (2%) | <0.001 |

| Regional Anesthetic, n (%) | 553 (8%) | 230 (9%) | 74 (8%) | 51 (6%) | 72 (8%) | 78 (9%) | 48 (7%) | 0.041 |

MME = morphine milligram equivalent; ICU = intensive care unit; IMU = intermediate monitoring unit; PCA = patient-controlled analgesia

Table 3:

Inpatient Non-Opioid Use Pre- and Post-Multi Modal Pain Regimen (MMPR)

| Median (IQR) | All (n = 6933) |

Pre-MMPR (n = 2594) |

2013 (n = 959) |

2014 (n = 886) |

2015 (n = 870) |

2016 (n = 894) |

2017 (n = 730) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lidocaine Patches, n

[% patients prescribed] |

0 (0 – 0) [24%] |

0 (0 – 0) [21%] |

0 (0 – 0) [23%] |

0 (0 – 0.1) [26%] |

0 (0 – 0) [25%] |

0 (0 – 0.1) [26%] |

0 (0 – 0.3) 28%] |

0.001 |

|

Acetaminophen, mg

[% patients prescribed] |

390 (0 – 2050) [68%] |

325 (0 – 1950) [68%] |

488 (0 – 2489) [70%] |

426 (0 – 2442) [69%] |

462 (0 – 1933) [71%] |

397 (0 – 1833) [68%] |

361 (0 – 2138) [64%] |

0.0373 |

|

NSAIDs*, doses [% patients prescribed] |

0.5 (0 – 2.2) [68%] |

0.5 (0 – 2) [66%] |

0.6 (0 – 2.3) [68%] |

0.5 (0 – 2.3) [67%] |

0.6 (0 – 2.1) [71%] |

0.5 (0 – 2) [67%] |

0.7 (0 – 2.6) [72%] |

0.0072 |

|

Gabapentinoids, doses

[% patients prescribed] |

0 (0 – 1.9) [49%] |

0 (0 – 1.7) [50%] |

0.1 (0 – 1.9) [51%] |

0.1 (0 – 1.8) [50%] |

0 (0 – 2) 45%] |

0 (0 – 2.2) [47%] |

0 (0 – 2.4) [49%] |

0.5035 |

NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs include ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib, ketorolac.

Patients with opioids prescribed at discharge significantly decreased from 83% in the pre-MMPR period to 74% in 2017 (p < 0.001). Discharge prescriptions of codeine, tramadol, and oxycodone increased (all p < 0.001), whereas hydrocodone prescriptions decreased in the post-MMPR period (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4:

Discharge Pain Medications Pre- and Post-Multi Modal Pain Regimen (MMPR)

| Median (IQR) | All (n = 6933) |

Pre-MMPR (n = 2594) |

2013 (n = 959) |

2014 (n = 886) |

2015 (n = 870) |

2016 (n = 894) |

2017 (n = 730) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients Discharged with Opioid, n (%) | 5629 (81%) | 2150 (83%) | 830 (87%) | 720 (81%) | 698 (78%) | 698 (78%) | 542 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Opioid | ||||||||

| Prescribed, n (%) | ||||||||

| Codeine | 374 (7%) | 5 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | 54 (7%) | 84 (12%) | 134 (19%) | 97 (18%) | <0.001 |

| Tramadol | 2287 (41%) | 223 (10%) | 269 (32%) | 371 (52%) | 488 (71%) | 515 (74%) | 421 (78%) | <0.001 |

| Hydrocodone | 3902 (69%) | 1968 (92%) | 757 (91%) | 530 (74%) | 277 (40%) | 228 (33%) | 142 (26%) | <0.001 |

| Oxycodone | 468 (8%) | 155 (7%) | 20 (2%) | 25 (3%) | 96 (14%) | 111 (16%) | 61 (11%) | <0.001 |

| Methadone | 16 (<1%) | 6 (<1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 4 (1%) | 0.104 |

Negative binomial regression showed that total MME administered per patient day decreased by 31% in 2017 as compared to 2010 (rate ratio 0.69, 95% CI 0.64 – 0.75), with the largest decreases being from 2014 to 2016 (Table 5). There was a 60% posterior probability that MME/patient day decreased by at least 30% in 2017 as compared to 2010 (Table 6). Averaged NRS pain scores decreased by 0.8 points (95% CI −0.87, −0.81) after implementation of the MMPR compared to 2010 (Table 5).

Table 5:

Bayesian Multi-Level Generalized Linear Models

| Morphine Milligram Equivalents per Day | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rate Ratio | 95% Credible Interval | |

| Unit of Admission* | ||

| IMU | 1.29 | 1.23 , 1.35 |

| Floor | 1.41 | 1.34 , 1.49 |

| Study Year§ | ||

| 2011 | 1.00 | 0.93 , 1.09 |

| 2012 | 1.10 | 1.01 , 1.19 |

| 2013 | 1.04 | 0.96 , 1.02 |

| 2014 | 1.00 | 0.92 , 1.08 |

| 2015 | 0.85 | 0.79 , 0.92 |

| 2016 | 0.69 | 0.63 , 0.74 |

| 2017 | 0.69 | 0.64 , 0.75 |

| Intercept | 55.7 | 52.3 , 59.4 |

| Average Numerical Rating Pain Scale Scores | ||

| Change in Pain Score | 95% Credible Interval | |

| Unit of Admission* | ||

| IMU | 0.14 | 0.13 , 0.16 |

| Floor | 1.03 | 1.01 , 1.05 |

| Study Year§ | ||

| 2011 | −0.08 | −0.11 , −0.05 |

| 2012 | 0.36 | 0.33 , 0.39 |

| 2013 | 0.36 | 0.33 , 0.39 |

| 2014 | −0.36 | −0.39 , −0.32 |

| 2015 | −0.52 | −0.55 , −0.49 |

| 2016 | −0.92 | −0.95 , −0.89 |

| 2017 | −0.84 | −0.87 , −0.81 |

| Intercept | 4.61 | 4.59, 4.64 |

Reference unit is Intensive Care Unit.

Reference year is 2010.

IMU = Intermediate Monitoring Unit

Table 6:

Posterior Probabilities of Different Reductions in Morphine Milligram Equivalent per Day from 2010–2017

| Percent Reduction | Posterior Probability |

|---|---|

| ≥ 10% | 100% |

| ≥ 20% | 100% |

| ≥ 30% | 60% |

| ≥ 40% | 0% |

| ≥ 50% | 0% |

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of over 6,000 trauma patients at a single U.S. Level 1 trauma center, implementation of a pill-based MMPR was associated with a significant reductions in in-hospital opioid exposure and opioid prescriptions at discharge. Our conservative estimate of 17 MME/patient day decrease in 2017 compared to 2010 is equivalent to a reduction of 11 mg of oxycodone or 17 mg of hydrocodone given per day. Contrary to our hypothesis, the reduction in opioid exposure was also associated with a significant, albeit modest, reduction in patient-reported NRS pain scores.

The gradual decrease in opioid exposure over time was expected given that the goal of the MMPR was to reduce opioid use. The implementation of the MMPR at our institution was initially controversial, because opioid-related overdose deaths had not yet garnered state-level attention, the impetus for reducing opioid prescribing was questioned by practitioners.9 Therefore, the need for decreasing opioid prescribing was questioned by practitioners. Additionally, potential complications associated with NSAIDs led to concerns regarding potential delays in healing bony fractures and increased bleeding risk in patients with traumatic brain injury. After a close review of available evidence and stakeholder engagement, these concerns were eased, though not eliminated. As awareness of the opioid epidemic spread and comfort with high-dose NSAID use in patients with fractures and traumatic brain injury has become standard, these concerns have now almost completely disappeared.

The reduction in self-reported NRS pain scores over this period was surprising as we had hypothesized that pain scores would remain unchanged. However, the observed improvement in pain scores with decreased opioid consumption may be due to that 1) opioid are not as effective in reducing pain as previously thought,10 2) opioids may cause paradoxical opioid-related hyperalgesia,11, 12 and 3) the MMPR may be more effective in reducing pain by targeting multiple pain pathways.13, 14

While the results of this study are encouraging, there are several unanswered questions that remain regarding the MMPR. First, the exact mechanism by which the MMPR was effective continues to be unknown. It is unknown whether all of the medications included in the MMPR are required to achieve significant improvements in pain scores; the effectiveness of individual components of the MMPR cannot be quantified from this study. While there was a significant increase in the amount of acetaminophen, doses of NSAIDs, and number of lidocaine patches, the number of gabapentinoid doses was similar. Attempting to understand the individual effect of any part of the MMPR was further confounded by the fact that our MMPR consisted of two different NSAIDs and two different gabapentinoids. Furthermore, the use of pregabalin and celecoxib was initially not limited to 48 hours. Thus, no statement regarding the effectiveness of the individual components of our MMPR can be made.

Second, the MMPR may not be generalizable. Intravenous acetaminophen, celecoxib, and pregabalin are not widely available in hospital formularies. The drugs were selected for the initial MMPR given their pharmacologic properties. Intravenous acetaminophen theoretically leads to faster therapeutic bloodstream levels and increased bioavailability.15 Celecoxib has fewer gastrointestinal side effects in patients at risk for acute gastritis and bleeding.16 Pregabalin has more consistent intestinal absorbption than gabapentin and also has a more consistent dose-response relationship.17 These drugs are not widely available despite these properties as they are more expensive than their oral and generic counterparts. A single-center, randomized clinical trial to address this question is ongoing.8

Lastly, the described MMPR was not truly opioid-minimizing as it included the use of scheduled tramadol. Tramadol is a centrally acting opioid that has long been considered a “safer” opioid because it is a weaker opioid receptor agonist. While tramadol may lead to lower rates of persistent opioid use, it still has potential to be abused by individuals. On a societal level, the reliance upon and increased prescribing of tramadol for pain will lead to an excess of pills available for diversion and another systematically misused and abused drug which prescribers will be slow to recognize. This pattern of abuse previously occurred with oxycodone and hydrocodone and was recognized too late.

There are several limitations to the study which must be considered. First, given its retrospective pre-post design, potential unknown confounding variables may exist that affect our estimates of MME/patient day and pain scores. Second, the exclusion of opioids provided during anesthesia, by continuous infusion, and via patient controlled analgesia lends our estimate of MME/patient day to be conservative. The true MME/patient day was likely to be higher as we were unable to include these sources. Nevertheless, the rate of change in MME/patient day and pain scores should not be greatly affected by this limitation. Also, because so many patients were included in this study, the inclusion of additional confounders to our model tends to not affect the estimates greatly. Third, the reliance on the NRS pain scores excludes scores from patients during the times that they cannot self-report levels of pain. NRS pain scores are the manner of assessing pain in verbal patients at our institution. We know of no systematic changes in the manner of assessing NRS pain scores over the study period that may have affected the trends observed. Not only is this pain score not applicable in non-verbal patients, but more are questioning its validity in clinical care and are considering a transition to other forms of pain evaluation, such as functional pain assessments.18 Fourth, this study only focused on the inpatient effects of the MMPR on opioid use. Opioid prescribing after discharge by other providers was not captured and long-term opioid use was not estimated. Lastly, while the MMPR was a tool used to decrease overall use of opioids, a cultural change in acute pain management occured at our institution over this time period that we are unable to quantify or adjust for in our analytical models. This change likely reflected the increased awareness of the opioid epidemic over the past decade.

Conclusion

The introduction of a multi-modal pain regimen resulted in significant reduction in MME administered per patient day, decreased the need for opioid prescriptions at discharge, and improved patient pain scores. The reduction in inpatient opioid use from 2010 to 2017 was equivalent to 11 mg less oxycodone or 17 mg less hydrocodone per patient per day. While the MMPR implementation was successful, additional research is needed to better understand its effect.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights:

Implementation of a Multi-Modal Pain Regimen in trauma patients led to decreased opioid use.

Patient pain scores significantly decreased after Multi-Modal Pain Regimen implementation.

No significant differences in adverse events such as ileus, cardiac arrest, or deaths

Disclosures:

SW is supported by a T32 fellowship (grant no. 5T32GM008792) from NIGMS. Authors report no conflicts of interest. JAH is supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences, which is funded by National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Award UL1 TR000371 and KL2 TR000370 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

- MMPR

Multi-modal pain regimen

- MME

Morphine milligram equivalents

- ISS

Injury severity score

- AIS

Abbreviated injury scale

- RDTI

Red Duke Trauma Institute

Footnotes

This study was given a podium presentation at the 71st Annual Southwestern Surgical Congress in Huntington Beach, California (April 14th – 17th, 2019).

References

- 1.Health NIo. Drug Overdoses Kill More Than Cars, Guns, and Falling Available: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/drug-overdoses-kill-more-than-cars-guns-falling. Accessed March, 2019, 2019.

- 2.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, et al. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, et al. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobaugh DJ, Gainor C, Gaston CL, et al. The opioid abuse and misuse epidemic: implications for pharmacists in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(18):1539–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oderda GM, Lake J, Rudell K, et al. Economic Burden of Prescription Opioid Misuse and Abuse: A Systematic Review. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29(4):388–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jalal H, Buchanich JM, Roberts MS, et al. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science. 2018;361(6408). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamplot JD, Wagner ER, Manning DW. Multimodal pain management in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvin JA, Green CE, Vincent LE, et al. Multi-modal Analgesic Strategies for Trauma (MAST): protocol for a pragmatic randomized trial. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2018;3(1):e000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health NIo. Texas Opioid Summary. 2018.

- 10.Trescot AM, Glaser SE, Hansen H, et al. Effectiveness of opioids in the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S181–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher D, Martinez V. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in patients after surgery: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112(6):991–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grace PM, Strand KA, Galer EL, et al. Morphine paradoxically prolongs neuropathic pain in rats by amplifying spinal NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(24):E3441–3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devin CJ, McGirt MJ. Best evidence in multimodal pain management in spine surgery and means of assessing postoperative pain and functional outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(6):930–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamrick KL, Beyer CA, Lee JA, et al. Multimodal Analgesia Decreases Opioid Use in Critically Ill Trauma Patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jibril F, Sharaby S, Mohamed A, et al. Intravenous versus Oral Acetaminophen for Pain: Systematic Review of Current Evidence to Support Clinical Decision-Making. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, et al. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(2):121–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(10):661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Topham D, Drew D. Quality Improvement Project: Replacing the Numeric Rating Scale with a Clinically Aligned Pain Assessment (CAPA) Tool. Pain Manag Nurs. 2017;18(6):363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.