Highlights

-

•

Neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with damage to the brain in the acute phase.

-

•

In mid-childhood, neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with smaller brain regions.

-

•

Deep grey matter regions such as the caudate and thalamus are implicated.

-

•

Children with neonatal hypoglycemia had smaller occipital lobe cortical thickness.

-

•

Grey matter may be especially vulnerable to long-term effects of neonatal hypoglycemia.

Keywords: Neonatal hypoglycaemia, MRI, Diffusion tensor imaging, Brain volume, Child

Abstract

Neonatal hypoglycaemia is a common metabolic disorder that may cause brain damage, most visible in parieto-occipital regions on MRI in the acute phase. However, the long term effects of neonatal hypoglycaemia on the brain are not well understood. We investigated the association between neonatal hypoglycaemia and brain volumes, cortical thickness and white matter microstructure at 9–10 years.

Children born at risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia at ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation who took part in a prospective cohort study underwent brain MRI at 9–10 years. Neonatal hypoglycaemia was defined as at least one hypoglycaemic episode (at least one consecutive blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mmol/L) or interstitial episode (at least 10 min of interstitial glucose concentrations < 2.6 mmol/L). Brain volumes and cortical thickness were computed using Freesurfer. White matter microstructure was assessed using tract-based spatial statistics.

Children who had (n = 75) and had not (n = 26) experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had similar combined parietal and occipital lobe volumes and no differences in white matter microstructure at nine years of age. However, those who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had smaller caudate volumes (mean difference: −557 mm3, 95% confidence interval (CI), −933 to −182, p = 0.004) and smaller thalamus (−0.03%, 95%CI, −0.06 to 0.00; p = 0.05) and subcortical grey matter (−0.10%, 95%CI −0.20 to 0.00, p = 0.05) volumes as percentage of total brain volume, and thinner occipital lobe cortex (−0.05 mm, 95%CI −0.10 to 0.00, p = 0.05) than those who had not. The finding of smaller caudate volumes after neonatal hypoglycaemia was consistent across analyses of pre-specified severity groups, clinically detected hypoglycaemic episodes, and severity and frequency of hypoglycaemic events.

Neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with smaller deep grey matter brain regions and thinner occipital lobe cortex but not altered white matter microstructure in mid-childhood.

1. Introduction

Hypoglycaemia is the most common metabolic problem in neonates, and can lead to brain damage and adverse developmental outcomes. (Shah et al., 2019) The operational definition of clinically significant neonatal hypoglycaemia remains controversial, (Cornblath et al., 2000) although a blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mmol/L is widely accepted as an appropriate threshold for treatment. (Koh et al., 1988, Lucas et al., 1988)

An initial case report of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings following isolated severe neonatal hypoglycaemia (blood glucose concentration 0.2 mmol/L) reported extensive bilateral damage in the posterior parietal and occipital lobes along with generalised cortical thinning throughout the brain. (Spar et al., 1994) Since then, multiple reports of term neonates scanned soon after symptomatic hypoglycaemia have identified parieto-occipital white matter injury along with restricted diffusion and abnormal signal intensities in the deep grey matter structures of the basal ganglia and thalamus. (Alkalay et al., 2005, Barkovich et al., 1998, Kinnala et al., 1999, Traill et al., 1998, Tam et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2006, Filan et al., 2006, Mao and Chen, 2007)

A prospective cohort study of 35 term neonates who had experienced symptomatic hypoglycaemia (≤ 2.6 mmol/L) also reported abnormalities in the deep grey matter regions, posterior cortex, and severe underlying white matter injury at a median age of nine days. (Burns et al., 2008) However, they also reported periventricular lesions, focal infarcts, and haemorrhage, which differed from the previous literature, (Alkalay et al., 2005, Traill et al., 1998) and may reflect the inclusion of neonates with mild hypoxic ischaemia as well as hypoglycaemia. (Inder, 2008) Diffusion weighted imaging case series suggest that neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with restricted diffusion in the parieto-occipital lobes and splenium of the corpus callosum in the days following hypoglycaemia episodes at various thresholds (≤ 0.6 mmol/L, (Kim et al., 2006) ≤ 1.5 mmol/L, (Filan et al., 2006) ≤ 1.7 mmol/L, (Mao and Chen, 2007) and < 2.6 mmol/L (Tam et al., 2008)). However, this was no longer detectable on diffusion imaging acquired only days later. (Tam et al., 2008, Kim et al., 2006, Filan et al., 2006)

Neuroimaging studies to date have focussed on severe, symptomatic and prolonged neonatal hypoglycaemia; the potential for selection bias is concerning and these cases may not be representative of typical infants who experience transitional hypoglycaemia. Furthermore existing published studies are either case reports (Traill et al., 1998, Alkalay et al., 2005, Barkovich et al., 1998) or descriptive studies with small sample sizes, (Kinnala et al., 1999, Murakami et al., 1999, Yalnizoglu et al., 2007, Per et al., 2008) and few included a control group. (Tam et al., 2008, Burns et al., 2008, Karimzadeh et al., 2011, Tam et al., 2012) Although there is general agreement that acute neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with damage in parietal-occipital lobes, (Alkalay et al., 2005, Tam et al., 2012, Gu et al., 2019) little is known about the long-term neurological or neuroimaging sequelae of neonatal hypoglycaemia. We report the association between neonatal hypoglycaemia and MRI-based brain measures in mid-childhood.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The CHYLD study is a prospective cohort study of babies born with one or more risk factors for neonatal hypoglycaemia: maternal diabetes, preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestation), small (< 10th centile or < 2500 g) or large (> 90th percentile or > 4500 g) birthweight, or other illness. Babies were recruited between December 2006 and November 2010 at Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand, and screened and treated aiming to maintain blood glucose concentrations ≥ 2.6 mmol/L. Two-thirds had masked continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) (CGMS Gold; Medtronic MiniMed). None had hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy. Details of the cohort are available elsewhere. (McKinlay et al., 2015, McKinlay et al., 2017, Harris et al., 2013, Harris et al., 2010)

All eligible participants (had not previously withdrawn or died) were invited to undergo neurodevelopmental assessment at 9–10 years for the CHYLD Mid-Childhood Outcome Study. Up to 75 eligible children born ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation were randomly selected from each of four groups, based on their experience of neonatal hypoglycaemia: none, mild (1 to 2 hypoglycaemic events 2.0 to 2.6 mmol/L, severe (any hypoglycaemia events < 2 mmol/L or ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic events) or clinically undetected hypoglycaemia (interstitial episodes only). Hypoglycaemic events were defined as the sum of nonconcurrent blood and interstitial (CGM-based) episodes more than 20 min apart. A hypoglycaemic episode was defined as at least one consecutive blood glucose concentration of < 2.6 mmol/L. Interstitial episodes were defined as at least 10 min of interstitial glucose concentrations < 2.6 mmol/L.

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Health and Disability Ethics Committee (16/NTB/208/AM02). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and assent from the child. All MRI scans were reviewed by a paediatric radiologist (RM) to detect clinically significant findings.

2.2. Image acquisition

MRI scans were acquired at Midland MRI, Anglesea Imaging Centre, Hamilton or the Centre for Advanced MRI (CAMRI), Auckland, with a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Skyra using a 20-channel head coil.

A sagittal T1-weighted three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence was acquired covering the whole head [slice thickness = 0.85 mm; repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms; echo time (TE) = 3.51 ms; field of view (FOV) = 210 mm; voxel size = 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm; flip angle = 9°].

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) was acquired on 58 slices along the anterior-posterior phase-encoding direction [b value = 2000 s/mm2; 64 gradient directions; slice thickness = 2.3 mm; TR = 8500 ms; TE = 112 ms; FOV = 225 mm; voxel size = 2.3 × 2.3 × 2.3 mm]. An additional image with b value = 0 s/mm2 was acquired in the opposite phase encoding polarity (posterior-anterior) to correct for susceptibility induced distortions. (Andersson et al., 2003)

2.3. Image processing

T1-weighted images were processed using Freesurfer 6.0 image analysis suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), as described elsewhere. (Dale et al., 1999, Fischl et al., 2001, Fischl et al., 2004) The Freesurfer recon-all stream was used, which has been validated in children aged 4–11 years. (Ghosh et al., 2010) All output was visually inspected and manually corrected when necessary.

DTI data were pre-processed using the Oxford Centre for Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain Software Library (FSL) version 6.0. (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) using the topup-eddy algorithm to correct for phase encoding distortions, motion, susceptibility, and eddy currents; (Andersson et al., 2003, Andersson and Sotiropoulos, 2016) slices deemed as outliers because of signal loss were replaced (--repol). (Andersson et al., 2016) Datasets with more than 10% of volumes removed due to uncorrected signal dropout or visible within-volume motion artefacts were excluded from further analysis. The diffusion toolbox was then used to fit the tensor model and compute fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD) and radial diffusivity (RD) maps for each participant.

This research was supported by use of the Nectar Research Cloud, a collaborative Australian research platform supported by the NCRIS-funded Australian Research Data Commons (ARDC).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics and clinical measurements were analysed using Student’s t-test, ANOVA, Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. All analyses followed a pre-specified analysis plan and were adjusted for sex, birth weight z-score, gestational age and age at MRI using JMP version 14.0 (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA) and FSL for DTI data.

We estimated differences of at least 0.8 standard deviations could be detected between those with (n = 25) and without (n = 75) hypoglycaemia, (PASS 16 Power Analysis and Sample Size Software (2018). NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA, ncss.com/software/pass) and that 25 analysable scans in each of the four hypoglycaemia exposure groups would give 90% power at the 5% significance level to detect a difference of 1.06 standard deviations between pairs of groups.

All brain volumetric measures are presented as absolute volume (mm3) and as percentage of total brain volume (%TBV) and compared between groups using generalized linear models with Dunnett’s post hoc pair-wise comparisons. Pre-specified between-group comparisons were primary; combined volume of parietal and occipital lobe, and secondary; volumes and cortical thickness of all other regions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total and regional brain volumes in participants who did and did not experience neonatal hypoglycaemia, and in different pre-specified severity groups.

| None vs any hypoglycaemia |

Severity of hypoglycaemia |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None Mean (SD) | Any Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p | Mild |

Severe |

Undetected |

||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |||||

| N | 26 | 75 | 24 | 30 | 21 | |||||

| Absolute brain volume (mm3) | ||||||||||

| Total brain | 1,230,213 (109081) | 1,224,016 (120056) | 2859 (-41637,47356) | 0.90 | 1,251,966 (104767) | 28,587 (-37727,94900) | 1,209,396 (136136) | −1704 (-65334,61926) | 1,212,964 (111570) | −19979 (-88468,48510) |

| Total white matter | 453,296 (48767) | 456,383 (56056) | 6265 (-14803,27332) | 0.56 | 468,348 (45363) | 17,262 (-14251,48776) | 449,413 (66985) | 3170 (-27069,33408) | 452,666 (49947) | −2033 (-34581,30514) |

| Total grey matter | 777,151 (68437) | 767,742 (67840) | −3565 (-29715,22585) | 0.78 | 783,751 (62179) | 11,230 (-27722,50183) | 760,113 (73666) | −5039 (-42415,32337) | 760,345 (65276) | −18171 (-58402,22059) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 339,007 (28457) | 337,152 (37294) | 843 (-3284,14970) | 0.91 | 348,515 (37702) | 11,682 (-9200,32565) | 329,454 (38514) | −4276 (-24313,15762) | 335,164 (33357) | −4685 (26253,16883) |

| Parietal lobe | 238,156 (23719) | 236,117 (28745) | 166 (-11009,11340) | 0.97 | 244,557 (27128) | 7297 (-9339,23932) | 231,045 (29937) | −2614 (-18577,13348) | 233,718 (27953) | −4224 (-21405,12957) |

| Occipital lobe | 100,852 (11248) | 101,035 (12889) | 678 (-4458,5813) | 0.79 | 103,959 (14213) | 4386 (-3217,11989) | 98,409 (11121) | −1661 (-8957,5634) | 101,446 (13499) | −461 (-8314,7391) |

| Frontal lobe | 350,844 (37662) | 351,382 (37191) | 3597 (-11087,18281) | 0.62 | 360,539 (32816) | 12,345 (-9521,34212) | 346,614 (40565) | 1951 (-19031,22933) | 347,726 (36670) | −4048 (-26632,18536) |

| Temporal lobe | 143,991 (17848) | 143,221 (16093) | 83 (-6473,6639) | 0.98 | 145,766 (12664) | 1909 (-7975,11794) | 141,652 (19085) | −314 (-9798,9171) | 142,555 (15288) | −1446 (-11654,8763) |

| Parahippocampal | 54,672 (4878) | 55,066 (6192) | 353 (-2160,2866) | 0.78 | 55,672 (6393) | 1135 (-2605,4874) | 55,631 (6486) | 1055 (-2534,4643) | 53,567 (5532) | −1418 (-5280,2445) |

| Cingulate cortex | 48,191 (4229) | 48,428 (5534) | 485 (-1634,2603) | 0.65 | 50,053 (5171) | 2005 (-1136,5146) | 47,464 (5728) | −182 (-3196,2832) | 47,950 (5493) | −356 (-3600,2888) |

| Insula | 35,057 (3965) | 34,702 (3693) | −187 (-1773,1399) | 0.81 | 35,106 (3621) | 94 (-2302,2489) | 34,428 (4263) | −238 (-2536,2061) | 34,631 (2953) | −436 (-2910,2038) |

| Caudate | 8029 (8 6 4) | 7425 (8 8 1) | −557 (-933,-182) | 0.004 | 7516 (7 3 9) | −490 (-1049,68) | 7505 (9 0 7) | −410 (-946, 126) | 7207 (9 9 1) | −820a (-1397,-243) |

| Putamen | 10,557 (1243) | 10,264 (1209) | −172 (-682,338) | 0.50 | 10,455 (1206) | −10 (-778,758) | 10,098 (1256) | –232 (-970,505) | 10,284 (1165) | −275 (-1068,519) |

| Pallidum | 4126 (4 8 1) | 4073 (4 9 7) | –32 (-242,178) | 0.76 | 4244 (5 1 0) | 139 (-169,447) | 4015 (5 3 6) | −66 (-362,229) | 3961 (3 8 1) | −179 (-497,139) |

| Subcortical grey matter | 60,822 (4489) | 59,313 (4967) | −1196 (-3138,747) | 0.14 | 60,022 (4240) | −562 (-3444,2321) | 59,512 (5855) | −582 (-3348,2184) | 58,220 (4356) | −2688 (-5665,290) |

| Thalamus | 15,829 (1209) | 15,426 (1484) | −330 (-915,256) | 0.24 | 15,660 (1291) | −110 (-968,748) | 15,569 (1731) | −74 (-897,750) | 14,954 (1248) | −902a (-1788,-16) |

| Cerebellum | 153,908 (19000) | 152,088 (16714) | −628 (-7559,6304) | 0.86 | 152,455 (13176) | −480 (-10873,9912) | 153,081 (19228) | 1789 (-8183,11760) | 150,250 (17109) | −3887 (-14620,6847) |

| Total brainstem | 19,650 (1916) | 19,703 (2199) | 176 (-685,1037) | 0.68 | 19,585 (2029) | 100 (-1191,1391) | 19,882 (2476) | 511 (-728,1749) | 19,584 (2045) | −168 (-1501,1165) |

| Optic chiasm | 148 (45) | 165 (47) | 19 (-2,40) | 0.07 | 166 (56) | 18 (-13,50) | 165 (40) | 22 (-8,52) | 162 (47) | 16 (-16,49) |

| Ventricles | 11,581 (3480) | 12,450 (5510) | 736 (-1561,3033) | 0.52 | 11,789 (4590) | 59 (-3353,3471) | 13,773 (6805) | 2109 (-1165,5383) | 11,316 (4057) | −269 (-3793,3255) |

| Anterior corpus callosum | 908 (1 7 2) | 883 (1 4 0) | −15 (-82,51) | 0.65 | 883 (1 3 5) | –22 (-122,79) | 874 (1 4 4) | −16 (-112,81) | 897 (1 4 6) | −8 (-112,96) |

| Mid anterior corpus callosum | 684 (1 6 1) | 694 (1 6 4) | 15 (-58,88) | 0.68 | 704 (1 6 2) | 26 (-84,136) | 687 (1 8 2) | 14 (-92,120) | 692 (1 4 7) | 5 (-109,119) |

| Central corpus callosum | 731 (1 2 5) | 720 (1 6 3) | −6 (-76,64) | 0.86 | 744 (1 3 6) | 17 (-89,122) | 699 (1 9 0) | −24 (-125,77) | 722 (1 5 5) | −9 (-118,100) |

| Mid posterior corpus callosum | 528 (1 0 1) | 510 (92) | −14 (-56,28) | 0.82 | 541 (61) | 15 (-48,78) | 486 (1 1 3) | −36 (-96,24) | 511 (82) | −18 (-83,47) |

| Posterior corpus callosum | 898 (1 3 9) | 878 (1 3 0) | −16 (-76,45) | 0.61 | 910 (1 1 7) | 11 (-80,102) | 858 (1 3 5) | –33 (-120,54) | 872 (1 3 6) | −24 (-118,70) |

| Percent of total brain volume | ||||||||||

| Total white matter | 36.82 (1.76) | 37.22 (1.42) | 0.40 (-0.29,1.08) | 0.26 | 37.38 (1.00) | 0.56 (-0.47,1.6) | 37.04 (1.80) | 0.23 (-0.75,1.2) | 37.28 (1.26) | 0.46 (-0.61,1.53) |

| Total grey matter | 63.20 (1.78) | 62.79 (1.42) | −0.41 (-1.10,0.28) | 0.25 | 62.63 (1.00) | −0.57 (-1.61,0.46) | 62.97 (1.80) | −0.23 (-1.21,0.75) | 62.73 (1.00) | −0.48 (-1.55,0.6) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 27.53 (1.51) | 27.58 (1.03) | −0.05 (-0.56,0.46) | 0.84 | 27.80 (1.19) | 0.22 (-0.54,0.97) | 27.26 (1.20) | −0.33 (-1.04,0.38) | 27.63 (0.98) | 0.04 (-0.74,0.82) |

| Parietal lobe | 19.37 (1.09) | 19.28 (1.25) | −0.09 (-0.63,0.46) | 0.87 | 19.52 (1.17) | 0.15 (-0.67,0.97) | 19.10 (1.15) | −0.27 (-1.04,0.51) | 19.26 (1.48) | −0.11 (-0.96,0.75) |

| Occipital lobe | 8.22 (0.79) | 8.25 (0.67) | 0.04 (-0.28,0.35) | 0.94 | 8.28 (0.66) | 0.06 (-0.41,0.54) | 8.15 (0.56) | −0.07 (-0.52,0.39) | 8.36 (0.83) | 0.15 (-0.35,0.64) |

| Frontal lobe | 28.49 (1.07) | 28.71 (1.08) | 0.21 (-0.28,0.70) | 0.32 | 28.80 (0.94) | 0.3 (-0.44,1.04) | 28.67 (1.12) | 0.17 (-0.52,0.87) | 28.66 (1.21) | 0.16 (-0.6,0.93) |

| Temporal lobe | 28.49 (1.07) | 28.71 (1.08) | 0.02 (-0.26,0.30) | 0.97 | 28.80 (0.94) | −0.03 (-0.45,0.40) | 28.67 (1.12) | 0.02 (-0.39,0.42) | 28.66 (1.21) | 0.07 (-0.37,0.52) |

| Parahippocampal | 4.45 (0.25) | 4.50 (0.31) | 0.05 (-0.08,0.18) | 0.80 | 4.44 (0.30) | −0.01 (-0.2,0.19) | 4.61 (0.30) | 0.16 (-0.03,0.34) | 4.42 (0.29) | −0.03 (-0.23,0.17) |

| Cingulate lobe | 3.92 (0.19) | 3.96 (0.23) | 0.03 (-0.06,0.13) | 0.61 | 4.00 (0.25) | 0.08 (-0.07,0.23) | 3.93 (0.19) | 0.00 (-0.14,0.14) | 3.95 (0.26) | 0.03 (-0.12,0.18) |

| Insular lobe | 2.85 (0.17) | 2.84 (0.18) | −0.01 (-0.09,0.07) | 0.69 | 2.81 (0.21) | −0.04 (-0.16,0.08) | 2.85 (0.18) | 0.00 (-0.12,0.12) | 2.86 (0.17) | 0.01 (-0.11,0.14) |

| Caudate | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.06) | −0.05 (-0.07,-0.02) | 0.001 | 0.60 (0.05) | −0.05a (-0.09,-0.01) | 0.62 (0.06) | −0.03 (-0.07,0.01) | 0.60 (0.07) | −0.06a (-0.10,-0.02) |

| Putamen | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.84 (0.09) | −0.02 (-0.05,0.02) | 0.20 | 0.84 (0.07) | −0.02 (-0.08,0.03) | 0.84 (0.09) | −0.02 (-0.07,0.03) | 0.85 (0.09) | −0.01 (-0.06,0.05) |

| Pallidum | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.01) | 0.99 | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.02) | 0.33 (0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.02) | 0.33 (0.03) | −0.01 (-0.03,0.01) |

| Pooled subcortical | 4.96 (0.24) | 4.86 (0.22) | −0.10 (-0.20,0.00) | 0.05 | 4.80 (0.20) | −0.15a (-0.31,-0.001) | 4.93 (0.21) | −0.02 (-0.17,0.12) | 4.81 (0.24) | −0.14 (-0.30,0.01) |

| Thalamus | 1.29 (0.08) | 1.26 (0.06) | −0.03 (-0.06,0.00) | 0.05 | 1.25 (0.07) | −0.04 (-0.08,0.01) | 1.29 (0.05) | 0.00 (-0.04,0.04) | 1.23 (0.05) | −0.06a (-0.10,-0.01) |

| Cerebellum | 12.52 (1.15) | 12.45 (0.99) | −0.07 (-0.54,0.39) | 0.77 | 12.20 (0.78) | −0.32 (-1.02,0.37) | 12.68 (1.04) | 0.16 (-0.5,0.81) | 12.41 (1.08) | −0.11 (-0.83,0.6) |

| Total brainstem | 1.60 (0.12) | 1.61 (0.12) | 0.01 (-0.04,0.07) | 0.73 | 1.57 (0.12) | −0.03 (-0.12,0.05) | 1.65 (0.11) | 0.04 (-0.03,0.12) | 1.62 (0.13) | 0.02 (-0.07,0.10) |

| Optic chiasm (x 10-2) | 1.19 (0.34) | 1.35 (0.36) | 0.15 (-0.00,0.32) | 0.05 | 1.32 (0.40) | 0.14 (-0.11,0.38) | 1.37 (0.29) | 0.18 (-0.05,0.41) | 1.35 (0.40) | 0.15 (-0.00,0.41) |

| Ventricle | 0.94 (0.27) | 1.01 (0.43) | 0.07 (-0.10,0.25) | 0.53 | 0.94 (0.33) | 0.00 (-0.27,0.26) | 1.14 (0.55) | 0.20 (-0.05,0.44) | 0.93 (0.29) | −0.01 (-0.28,0.26) |

| Corpus callosum (x 10-2) | ||||||||||

| Anterior of corpus callosum | 7.36 (1.10) | 7.23 (1.01) | −0.14 (-0.60,0.33) | 0.65 | 7.06 (0.98) | −0.30 (-1.01,0.40) | 7.24 (1.05) | −0.12 (-0.78,0.55) | 7.40 (0.99) | 0.03 (-0.69,0.76) |

| Mid anterior of corpus callosum | 5.57 (1.28) | 5.68 (1.24) | 0.10 (-0.46,0.67) | 0.72 | 5.65 (1.28) | 0.08 (-0.78,0.93) | 5.67 (1.28) | 0.09 (-0.72,0.90) | 5.71 (1.20) | 0.14 (-0.74,1.03) |

| Central of corpus callosum | 5.99 (1.12) | 5.90 (1.30) | −0.09 (-0.66,0.48) | 0.73 | 5.98 (1.50) | 0.00 (-0.86,0.85) | 5.79 (1.18) | −0.20 (-1.01,0.61) | 5.95 (1.17) | −0.04 (-0.92,0.85) |

| Mid posterior of corpus callosum | 5.57 (1.28) | 5.68 (1.24) | 0.10 (-0.46,0.67) | 0.72 | 5.65 (1.28) | 0.08 (-0.78,0.93) | 5.67 (1.28) | 0.09 (-0.72,0.90) | 5.71 (1.20) | 0.14 (-0.74,1.03) |

| Posterior of corpus callosum | 7.32 (1.05) | 7.20 (0.98) | −0.12 (-0.57,0.33) | 0.53 | 7.29 (0.96) | −0.02 (-0.70,0.66) | 7.10 (0.84) | −0.22 (-0.86,0.43) | 7.23 (1.20) | −0.08 (-0.79,0.62) |

| Cortical thickness | ||||||||||

| Total cerebral | 2.81 (0.13) | 2.80 (0.10) | −0.002 (-0.05,0.05) | 0.91 | 2.78 (0.09) | −0.02 (-0.09,0.06) | 2.82 (0.10) | 0.01 (-0.05,0.08) | 2.80 (0.11) | −0.007 (-0.08,0.07) |

| Parietal lobe | 2.70 (0.13) | 2.68 (0.12) | −0.02 (-0.07,0.04) | 0.56 | 2.66 (0.12) | −0.03 (-0.12,0.05) | 2.68 (0.12) | −0.01 (-0.09,0.07) | 2.69 (0.12) | −0.01 (-0.09, 0.08) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.30 (0.12) | 2.24 (0.11) | −0.05 (-0.10,0.00) | 0.05 | 2.25 (0.10) | −0.04 (-0.11,0.04) | 2.24 (0.10) | −0.04 (-0.11,0.03) | 2.24 (0.11) | −0.06 (-0.14,0.01) |

| Frontal lobe | 2.89 (0.16) | 2.90 (0.12) | 0.02 (-0.04,0.08) | 0.53 | 2.89 (0.12) | 0.007 (-0.08,0.10) | 2.92 (0.12) | 0.03 (-0.05,0.12) | 2.90 (0.12) | 0.01 (-0.08,0.10) |

| Temporal lobe | 3.08 (0.17) | 3.10 (0.12) | −0.002 (-0.07,0.06) | 0.95 | 3.07 (0.11) | −0.01 (-0.12,0.09) | 3.12 (0.13) | 0.004 (-0.09,0.10) | 3.11 (0.13) | 0.003 (-0.10,0.11) |

| Parahippocampal | 3.12 (0.12) | 3.14 (0.13) | 0.02 (-0.04,0.07) | 0.59 | 3.12 (0.11) | 0.001 (-0.08,0.08) | 3.19 (0.11) | 0.06 (-0.02,0.14) | 3.10 (0.14) | −0.02 (-0.11,0.06) |

| Cingulate cortex | 2.85 (0.15) | 2.85 (0.12) | 0.003 (-0.05,0.06) | 0.92 | 2.83 (0.08) | −0.01 (-0.10,0.07) | 2.90 (0.14) | 0.05 (-0.04,0.13) | 2.82 (0.11) | −0.03 (-0.12,0.05) |

| Insula | 3.28 (0.15) | 3.26 (0.15) | −0.02 (-0.09,0.05) | 0.59 | 3.24 (0.10) | −0.05 (-0.15,0.06) | 3.28 (0.16) | 0.003 (-0.09,0.10) | 3.26 (0.17) | −0.01 (-0.12,0.09) |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or mean difference (95% confidence interval). None, no evidence of hypoglycaemic events; Any, any hypoglycaemic events (mild + severe + undetected); Mild, 1 or 2 hypoglycaemic events between 2.0 and 2.6 mmol/L; Severe, any hypoglycaemic events < 2 mmol/L or ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic events; Undetected, interstitial episodes only. Hypoglycaemic events are defined as the sum of nonconcurrent hypoglycaemic and interstitial episodes more than 20 min apart. A hypoglycaemic episode is defined as at least one consecutive blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mmol/L. Interstitial episodes are defined as at least 10 min of interstitial glucose concentrations < 2.6 mmol/L.ap ≤ 0.05 for comparison with the None group (Dunnett).

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) were used to compare voxel-wise white matter microstructure between the groups. (Smith et al., 2006) Results were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05 following threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) and family-wise error rate correction.

The primary analysis compared MRI measures between those who had and had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia and between the four pre-specified severity groups (no, mild, severe and undetected hypoglycaemia). Sensitivity analyses were performed excluding children scanned outside the major scanning site, twins, children with any postnatal head injury or seizures, and children with no CGM data. To explore the effect of sex, we included sex interaction terms in the analyses and performed subgroup analyses of girls and boys separately.

Post hoc exploratory analyses related the outcomes to the severity and frequency of clinically detected hypoglycaemia, as previously described, (McKinlay et al., 2015, McKinlay et al., 2017) where severity was classified based on hypoglycaemic episodes (blood glucose only) as none, mild (2 to 2.6 mmol/L), and severe (< 2 mmol/L), and frequency was classified as none, 1 to 2, and ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic episodes.

Similarly, since criteria for the pre-specified severity groups included both severity and frequency of low glucose concentrations, we separately classified the severity of hypoglycaemic events (blood or interstitial glucose) as none, mild (2 to 2.6 mmol/L), or severe (<2 mmol/L), and frequency as none, 1 to 2, and ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic events.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

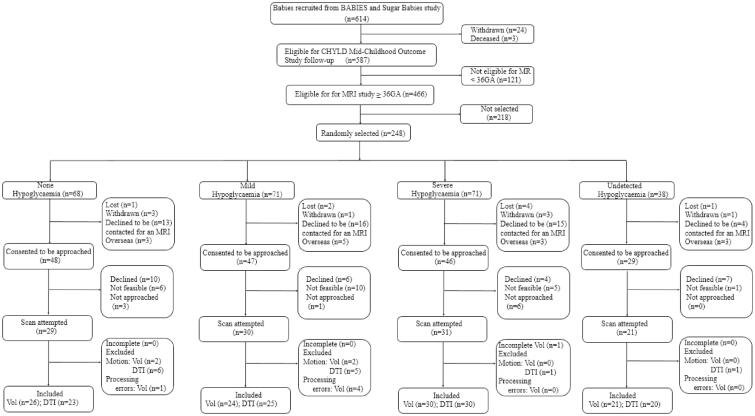

Of the 248 children initially randomly selected, parents of 170 (69%) agreed to be approached about MRI. Of these, 27 declined, scanning was not feasible in 22, e.g., living too far from scanning site, and 10 were not approached because sufficient scans had been completed in that group. The remaining 111 children (69% of those approached) underwent MRI between 2017 and 2020 at a median age of 9.5 (range: 9.0 to 12.4) years. After exclusion due to motion (n = 10 volumetric; n = 13 DTI), 101 children were included in the volumetric analysis and 98 in the DTI analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of recruitment for CHYLD Mid-Childhood Outcomes MRI Study. GA = gestational age; Vol = morphometric analysis; DTI = diffusion tensor imaging.

Of the children included in the MRI analysis, those who had experienced any neonatal hypoglycaemia compared to those who had not were not different in sex, gestational age, weight, length, and head circumference at birth, or primary reason for risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia (Table 1). Those who had experienced any neonatal hypoglycaemia had a higher percentage of interstitial glucose concentrations outside the central band (3 to 4 mmol/L) (McKinlay et al., 2015, Harris et al., 2010) and lower mean and minimum blood and interstitial glucose concentrations, but similar maximum blood and interstitial glucose concentrations in the first 48 h (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who did and did not experience neonatal hypoglycaemia, and in different pre-specified severity groups.

| Variable | None |

Any |

Mild |

Severe |

Undetected |

p |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None vs Any | Severity of hypoglycaemia | ||||||

| N | 26 | 75 | 24 | 30 | 21 | ||

| Neonatal characteristics | |||||||

| Boys | 13 (50) | 35 (47) | 10 (42) | 13 (43) | 12 (57) | 0.76 | 0.71 |

| Birth weight z-score | 0.09 (1.94) | 0.10 (1.77) | 0.55 (1.42) | −0.03 (2.00) | −0.23 (1.74) | 0.98 | 0.50 |

| Birth weight (g) | 3230 (9 4 2) | 3206 (8 5 4) | 3393 (6 9 9) | 3135 (9 8 2) | 3097 (8 2 3) | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| Birth length z-score¶ | 0.48 (1.08) | 0.89 (1.34) | 1.38 (1.21) | 0.35 (1.37) | 1.38†† | 0.45 | 0.26 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 38.4 (1.4) | 38.3 (1.6) | 38.3 (1.6) | 38.1 (1.6) | 38.4 (1.6) | 0.76 | 0.89 |

| Birth head circumference z-score¶ | −0.08 (1.42) | 0.32 (1.72) | 0.55 (1.13) | 0.31 (2.05) | −0.01 (1.60) | 0.30 | 0.68 |

| Twin | 1 (4) | 5 (7) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 2 (10) | 0.60 | 0.84 |

| Primary risk for hypoglycaemia‡ | 0.73 | 0.78 | |||||

| IDM | 12 (47) | 37 (49) | 15 (63) | 11 (37) | 11 (52) | ||

| Preterm | 3 (12) | 14 (19) | 4 (17) | 7 (23) | 3 (14) | ||

| Small | 6 (23) | 11 (15) | 1 (4) | 6 (20) | 4 (19) | ||

| Large | 4 (15) | 8 (11) | 3 (13) | 3 (10) | 2 (10) | ||

| Others | 1 (4) | 5 (7) | 1 (4) | 3 (10) | 1 (5) | ||

| High deprivation† | 9 (35) | 24 (32) | 4 (17) | 9 (30) | 11 (52) | 0.88 | 0.58 |

| Measures of glycaemia in first 48 h | |||||||

| Duration of episodes (CGM, min)¶ | 0 | 157 (1 9 4) | 101 (1 1 6) | 243a (2 4 5) | 91 (1 1 8) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Mean blood glucose | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.4) | 3.3a (0.3) | 3.1a (0.3) | 3.5a (0.4) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Maximum blood glucose | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.6) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.8) | 0.13 | 0.20 |

| Minimum blood glucose | 3.1 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.3a (0.2) | 1.9a (0.4) | 2.8a (0.2) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Mean interstitial glucose¶ | 3.7 (0.4) | 3.4 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.4a (0.5) | 0.004 | 0.04 |

| Maximum interstitial glucose¶ | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.6 (1.3) | 4.6 (0.7) | 4.9 (1.8) | 4.3 (0.8) | 0.65 | 0.39 |

| Minimum interstitial glucose¶ | 3.0 (0.3) | 2.3 (0.4) | 2.3a (0.5) | 2.2a (0.5) | 2.4a (0.3) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Percentage of blood glucose concentrations outside the central band (3 to 4 mmol/L) | 38.2 (23.2) | 48.2 (21.7) | 47.9 (17.2) | 58.4a (15.6) | 34.1 (26.3) | 0.06 | 0.0002 |

| Percentage of interstitial glucose concentrations outside the central band (3 to 4 mmol/L)¶ | 30.0 (25.0) | 41.9 (20.8) | 42.4 (21.2) | 44.9a (17.0) | 37.9 (24.6) | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Head circumference z-score | |||||||

| 2 years¶ | 0.97 (1.14) | 0.86 (1.24) | 1.28 (0.95) | 0.53 (1.22) | 0.81 (1.46) | 0.69 | 0.21 |

| 4.5 years¶ | 0.61 (0.97) | 0.73 (1.12) | 1.06 (1.14) | 0.66 (1.28) | 0.45 (0.68) | 0.62 | 0.31 |

| Characteristics at nine-year assessment | |||||||

| Right-Handed | 23 (88) | 67 (89) | 23 (96) | 26 (87) | 18 (86) | 0.90 | 0.67 |

| Age at the time of MRI scan (y) | 9.5 (0.6) | 9.7 (0.6) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.8 (0.8) | 9.6 (0.4) | 0.19 | 0.27 |

| MRI scanning site Midlands | 24 (92) | 69 (92) | 23 (96) | 28 (93) | 18 (86) | 0.96 | 0.63 |

| Ethnicity | 0.10 | 0.46 | |||||

| Māori | 7 (27) | 28 (37) | 8 (33) | 10 (33) | 10 (48) | ||

| Pacific | 2 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) | ||

| Asian | 1 (4) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | ||

| European | 16 (61) | 45 (60) | 16 (67) | 19 (63) | 10 (48) | ||

Data are presented as n (%) or mean (standard deviation). CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; IDM, Infant of diabetic mother. None, no evidence of hypoglycaemic events; Any hypoglycaemia, any hypoglycaemic events (mild + severe + undetected); Mild, 1 or 2 hypoglycaemic events between 2.0 and 2.6 mmol/L; Severe, any hypoglycaemic events < 2 mmol/L or ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic events; Undetected, interstitial episodes only. Hypoglycaemic events are defined as the sum of nonconcurrent hypoglycaemic and interstitial episodes more than 20 min apart. A hypoglycaemic episode is defined as at least one consecutive blood glucose concentration (BGC) < 2.6 mmol/L. Interstitial episodes are defined as at least 10 min of interstitial glucose concentrations < 2.6 mmol/L. ¶Missing data: Birth length z-score: Total 72, None 18, Any 54, Mild 14, Severe 20, Undetected 20; Birth head circumference z-score: Total 32, None 5, Any 27, Mild 10, Severe 5, Undetected 12; Duration of episodes: Total 15, Any 15, Mild 10, Severe 5; Mean/maximum/minimum interstitial glucose: Total 15, Any 15, Mild 10, Severe 5; Percentage of interstitial glucose concentrations outside the central band (3 to 4 mmol/L) in the first 48 h: Total 15, Any 15, Mild 10, Severe 5; Head circumference z-score at 2 years: Total 14, None 1, Any 13, Mild 3, Severe 7, Undetected 3; Head circumference z-score at 4.5 years: Total 11, None 4, Any 7, Mild 2, Severe 2, Undetected 3. ††Data available only for one participant. ‡Small: < 10th centile or < 2.5 kg; Large: greater than 90th centile or greater than 4.5 kg; Others: sepsis, haemolytic disease of the newborn, respiratory distress, congenital heart disease, and poor feeding. †High deprivation: NZDPI 8 to 10. ap ≤ 0.05 for comparison with the None group (Dunnett).

Among the children who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia, those in the undetected hypoglycaemia group had the highest mean and minimum blood glucose concentration, suggesting that they had experienced less severe hypoglycaemia than those in the other two pre-defined groups. Children in the severe hypoglycaemia group had the longest duration of episodes and the highest percentage of blood and interstitial glucose concentrations outside the central band in the first 48 h (Table 1). There were two children who experienced afebrile seizures in childhood, one of these two also had hypoglycaemia related seizures in infancy

3.2. Any neonatal hypoglycaemia

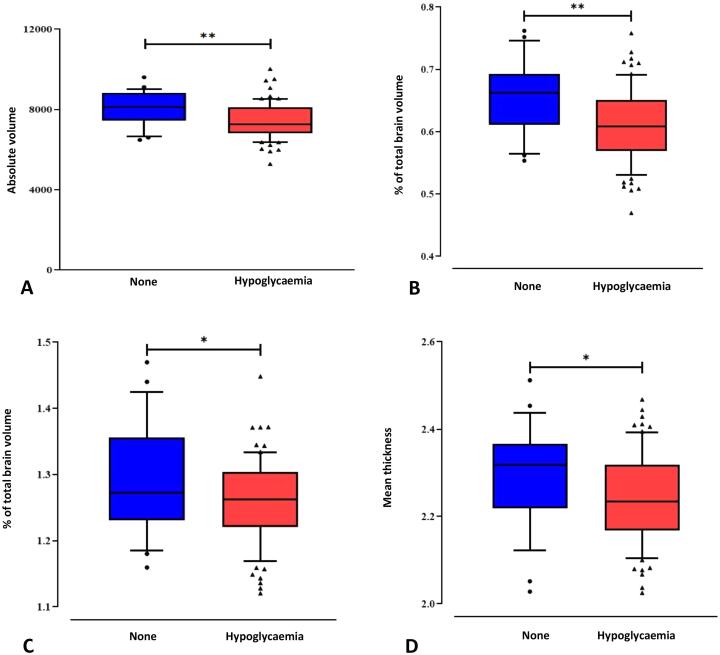

Children who had and had not experienced any neonatal hypoglycaemia had similar combined parietal and occipital lobe volumes. Compared with those who had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia, children who had had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV (mean difference: −557 mm3, 95% confidence interval (CI), −933 to −182, p = 0.004; −0.05%, 95%CI −0.07 to −0.02; p = 0.001); smaller subcortical grey matter %TBV (−0.10%, 95%CI −0.20 to 0.00, p = 0.05); smaller thalamus %TBV (-0.03%, 95%CI −0.06 to 0.00, p = 0.05) and larger optic chiasm %TBV (0.15%, 95%CI −0.00 to 0.32, p = 0.05) (Table 2). Children who had experienced any hypoglycaemia also had smaller occipital lobe cortical thickness (−0.05 mm, 95%CI −0.10 to 0.00, p = 0.05), but there was no difference between groups in parietal lobe cortical thickness (Table 2) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Caudate volume (absolute volume in mm3 A; and as percentage of total brain volume B), relative thalamus volume (C) and occipital lobe mean thickness in mm (D) were lower in children who experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia compared to children who did not. ** p < 0.01; *p ≤ 0.05.

There were no differences across the white matter skeleton in any of the assessed contrasts between children who had and had not experienced any neonatal hypoglycaemia for FA (none > any; lowest p = 0.11), MD (none < any; lowest p = 0.27), AD (none > any; lowest p = 0.54), RD (none < any; lowest p = 0.18), or MO (none > any; lowest p = 0.19) (Figure S1).

3.3. Pre-defined severity

When compared with children who had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia, children who experienced undetected episodes had smaller caudate and thalamus volumes both absolute and %TBV. Children who experienced mild neonatal hypoglycaemia had smaller caudate and subcortical grey matter volumes %TBV (Table 2). There were no other significant differences between severity groups.

There were no differences across the white matter skeleton in any of the assessed contrasts when children in the undetected, mild and severe hypoglycaemia groups were compared with children who had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia.

3.4. Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses including children scanned at the major scanning site (Midland MRI), excluding twins, excluding children with postnatal injury or seizures, and excluding children with no CGM yielded results similar to those of the main analyses (Supplementary Tables S1 to S4). Children who had experienced any neonatal hypoglycaemia, and children in the mild and undetected hypoglycaemia groups had smaller caudate volumes and smaller cortical thickness of the occipital lobe compared to children who had not experienced hypoglycaemia. There were no differences across the white matter skeleton in any of the assessed contrasts.

3.5. Sex effects

The sex interaction terms for the relationship between hypoglycaemia and brain volumes were significant for the combined parietal and occipital lobe volume %TBV (p = 0.02); but not for the other 18 comparisons.

Girls (n = 53) who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had smaller combined parietal and occipital volumes %TBV (−0.60%, 95% CI −1.17 to −0.02, p = 0.04), but not absolute volume than those who had not experienced hypoglycaemia (Table S5). Girls who experienced severe hypoglycaemia also had smaller combined parietal and occipital volumes both absolute and %TBV.

Boys (n = 48) who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV (−576 mm3, 95% CI −1144 to −8, p = 0.04; −0.06%, 95%CI −0.09 to −0.02, p = 0.001) and smaller total grey matter %TBV (-1.03%, 95% CI −2.10 to −0.04, p = 0.05) and correspondingly larger total white matter %TBV (1.03%, 95%CI −0.03 to 2.09, p = 0.05) than those who had not experienced hypoglycaemia (Table S6). Boys in the undetected hypoglycaemia group had smaller caudate volumes both absolute and %TBV, and in the mild hypoglycaemia group had smaller caudate volumes %TBV only.

The sex interaction terms were not significant for any DTI measures. When girls (n = 50) and boys (n = 48) were analysed separately, there were no differences across the white matter skeleton in any of the assessed contrasts.

3.6. Clinically detected neonatal hypoglycaemia

Compared to children who had not experienced hypoglycaemia, children who had experienced mild episodes of clinically detected hypoglycaemia (blood glucose 2.0 to 2.6 mmol/L) had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV and children who had experienced severe episodes (< 2.0 mmol/L) had a smaller caudate volume as absolute volume (Table 3). Similarly, children who had experienced 1 to 2 episodes of clinically detected hypoglycaemia had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV. There were no differences across the white matter skeleton between groups classified based on either severity or frequency of clinically detected hypoglycaemia.

Table 3.

Total and regional brain volumes and cortical thickness in participants who did and did not experience clinically detected neonatal hypoglycaemia.

| None |

Mild |

Severe |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| N | 26 | 37 | 17 | ||

| Absolute brain volume (mm3) | |||||

| Total brain | 1,230,213 (109081) | 1,255,946 (117262) | 28,562 (-26575,83698) | 1,168,173 (119718) | −36360 (-109490,36770) |

| Total white matter | 453,296 (48767) | 468,720 (53893) | 16,397 (-10158,42952) | 434,124 (63114) | −9761 (-44982,25460) |

| Total grey matter | 777,151 (68437) | 787,307 (66653) | 12,005 (-20501,44511) | 734,298 (61787) | −26753 (-69868,16361) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 339,007 (28457) | 346,617 (38295) | 8474 (-8902,25851) | 319,009 (34354) | −13080 (-36127,9967) |

| Parietal lobe | 238,156 (23719) | 242,904 (28588) | 5191 (-8396,18778) | 224,310 (27273) | −7394 (-25415,10627) |

| Occipital lobe | 100,852 (11248) | 103,713 (12794) | 3283 (-2984,9550) | 94,699 (10620) | −5686 (-13998,2626) |

| Caudate | 8029 (1 6 4) | 7606 (1 3 8) | −425a (-861,10) | 7300 (2 0 3) | −574a (-1151,3) |

| Putamen | 10,557 (1243) | 10,404 (1123) | −128 (-787,530) | 9935 (1435) | −172 (-1045,702) |

| Pallidum | 4126 (4 8 1) | 4189 (4 9 5) | 74 (-195,342) | 3959 (5 8 9) | −102 (-458,254) |

| Percent of total brain volume | |||||

| Total white matter | 36.82 (1.76) | 37.26 (1.30) | 0.44 (-0.48,1.36) | 37.05 (1.88) | 0.23 (-0.89,1.35) |

| Total grey matter | 63.20 (1.78) | 62.75 (1.31) | −0.46 (-1.38,0.47) | 62.97 (1.87) | −0.23 (-1.36,0.89) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 27.59 (1.03) | 27.59 (1.32) | 0.00 (-0.67,0.67) | 27.31 (0.96) | −0.27 (-1.09,0.54) |

| Parietal lobe | 19.37 (1.09) | 19.33 (1.24) | −0.04 (-0.70,0.63) | 19.19 (1.01) | −0.17 (-0.98,0.63) |

| Occipital lobe | 8.22 (0.79) | 8.25 (0.60) | 0.04 (-0.35,0.42) | 8.12 (0.62) | −0.10 (-0.57,0.37) |

| Caudate | 0.65 (0.01) | 0.61 (0.01) | −0.05a (-0.08,-0.01) | 0.63 (0.01) | −0.03 (-0.07,0.01) |

| Putamen | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.83 (0.08) | −0.03 (-0.07,0.02) | 0.85 (0.09) | −0.01 (-0.06,0.05) |

| Pallidum | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.02) | 0.34 (0.04) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.03) |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | |||||

| Parietal lobe | 2.70 (0.13) | 2.68 (0.11) | −0.02 (-0.09,0.05) | 2.66 (0.12) | −0.02 (-0.12,0.07) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.30 (0.12) | 2.26 (0.10) | −0.03 (-0.09,0.03) | 2.21 (0.12) | −0.06 (-0.14,0.02) |

| None | 1 to 2 hypoglycaemic episodes | ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic episodes | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| N | 26 | 45 | 9 | ||

| Absolute brain volume (mm3) | |||||

| Total brain | 1,230,213 (109081) | 1,238,873 (128446) | 16,688 (-38376,71751) | 1,175,517 (85173) | −16428 (-106968,74113) |

| Total white matter | 453,296 (48767) | 464,009 (58824) | 13,498 (-12536,39532) | 426,926 (49587) | −12918 (-55725,29890) |

| Total grey matter | 777,151 (68437) | 775,041 (72413) | 3084 (-29553,35721) | 748,512 (47105) | −3985 (-57650,49680) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 339,007 (28457) | 341,834 (39169) | 5118 (-12192,22428) | 318,387 (33404) | −9939 (-38402,18524) |

| Parietal lobe | 238,156 (23719) | 240,340 (28596) | 4130 (-9110,17369) | 220,602 (28389) | −10890 (-32660,10879) |

| Occipital lobe | 100,852 (11248) | 101,494 (13508) | 988 (-5391,7367) | 97,785 (7996) | 951 (-9538,11440) |

| Caudate | 8029 (1 7 3) | 7513 (8 1 4) | −473a (-898,-48) | 7493 (9 5 4) | −408 (-1106,291) |

| Putamen | 10,557 (1243) | 10,334 (1210) | −111 (-752,529) | 9870 (1364) | −306 (-1359,747) |

| Pallidum | 4126 (4 8 1) | 4140 (5 4 7) | 31 (–233,295) | 3999 (4 5 6) | 15 (-419,449) |

| Percent of total brain volume | |||||

| Total white matter | 36.82 (1.76) | 37.38 (1.31) | 0.54 (-0.32,1.40) | 36.25 (2.05) | −0.61 (-2.02,0.80) |

| Total grey matter | 63.20 (1.78) | 62.63 (1.31) | −0.55 (-1.41,0.31) | 63.74 (2.06) | 0.56 (-0.86,1.98) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 27.59 (1.03) | 27.59 (1.19) | 0.01 (-0.66,0.68) | 27.05 (1.33) | −0.53 (-1.63,0.57) |

| Parietal lobe | 19.37 (1.09) | 19.40 (1.09) | 0.07 (-0.58,0.71) | 18.73 (1.43) | −0.68 (-1.74,0.38) |

| Occipital lobe | 8.22 (0.79) | 8.19 (0.63) | −0.06 (-0.42,0.30) | 8.33 (0.47) | 0.15 (-0.44,0.74) |

| Caudate | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.05) | −0.05a (-0.08,-0.01) | 0.64 (0.07) | −0.03 (-0.08,0.03) |

| Putamen | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.84 (0.08) | −0.02 (-0.06,0.03) | 0.84 (0.08) | −0.01 (-0.09,0.06) |

| Pallidum | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.03) | −0.001 (-0.02,0.02) | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.01 (-0.02,0.04) |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | |||||

| Parietal lobe | 2.70 (0.02) | 2.65 (0.11) | −0.04 (-0.10,0.03) | 2.77 (0.09) | 0.08 (-0.03,0.18) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.30 (0.02) | 2.23 (0.11) | −0.05 (-0.11,0.01) | 2.30 (0.11) | 0.03 (-0.07,0.13) |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or mean difference (95% confidence interval). None, no hypoglycaemic episodes; Mild, blood glucose concentrations between 2.0 and 2.6 mmol/L; Severe, < 2 mmol/L. A hypoglycaemic episode is defined as at least one consecutive < 2.6 mmol/L. ap ≤ 0.05 for comparison with the None group (Dunnett)

3.7. Severity and frequency of hypoglycaemic events

Children who had experienced mild hypoglycaemic events and those who had experienced severe events had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV, than children who had not experienced hypoglycaemia (Table 4). Similarly, children who had experienced 1 to 2 events and those who had experienced ≥ 3 events had smaller caudate volumes, both absolute and %TBV, than children who had not experienced hypoglycaemia. There were no differences across the white matter skeleton between groups classified based on severity or frequency of hypoglycaemic events

Table 4.

Total and regional brain volumes and cortical thickness in participants who did and did not experience different severities and frequencies of neonatal hypoglycaemic events.

| None |

Mild |

Severe |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| N | 26 | 43 | 32 | ||

| Absolute brain volume (mm3) | |||||

| Total brain | 1,230,213 (109081) | 1,234,547 (120810) | 12,000 (-40356,64356) | 1,200,207 (117442) | −20855 (-85139,43430) |

| Total white matter | 453,296 (48767) | 459,835 (53964) | 9625 (-15254,34504) | 448,579 (61048) | −2454 (-33001,28093) |

| Total grey matter | 777,151 (68437) | 774,827 (69793) | 2237 (-28485,32959) | 751,726 (61656) | −18617 (-56339,19104) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 339,007 (28457) | 340,563 (37756) | 3678 (-12951,20307) | 329,440 (35833) | −6511 (-26929,13907) |

| Parietal lobe | 238,156 (23719) | 237,535 (29003) | 1100 (-12149,14348) | 232,911 (28528) | −2257 (-18525,14010) |

| Occipital lobe | 100,852 (11248) | 103,028 (13322) | 2578 (-3338,8495) | 96,530 (10804) | −4253 (-11518,3011) |

| Caudate | 8029 (1 6 4) | 7513 (9 2 8) | −479a (-920,-37) | 7226 (7 4 5) | −761a (-1303,-218) |

| Putamen | 10,557 (1243) | 10,338 (1182) | −140 (-745,465) | 10,098 (1278) | −254 (-997,489) |

| Pallidum | 4126 (4 8 1) | 4067 (4 4 3) | −38 (-287,211) | 4087 (6 1 2) | −17 (–323,288) |

| Percent of total brain volume | |||||

| Total white matter | 36.82 (1.76) | 37.19 (1.23) | 0.39 (-0.41,1.20) | 37.27 (1.82) | 0.37 (-0.62,1.36) |

| Total grey matter | 63.20 (1.78) | 62.82 (1.23) | −0.41 (-1.22,0.40) | 62.74 (1.81) | −0.39 (-1.38,0.61) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 27.59 (1.03) | 27.58 (1.23) | −0.01 (-0.62,0.61) | 27.44 (0.98) | −0.10 (-0.86,0.65) |

| Parietal lobe | 19.37 (1.09) | 19.23 (1.34) | −0.11 (-0.76,0.54) | 19.39 (1.02) | 0.13 (-0.67,0.92) |

| Occipital lobe | 8.22 (0.79) | 8.34 (0.68) | 0.10 (-0.24,0.45) | 8.05 (0.62) | −0.23 (-0.66,0.20) |

| Caudate | 0.65 (0.01) | 0.61 (0.06) | −0.05a (-0.08,-0.01) | 0.60 (0.06) | −0.05a (-0.09,-0.01) |

| Putamen | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.84 (0.09) | −0.02 (-0.06,0.03) | 0.84 (0.08) | −0.005 (-0.06,0.05) |

| Pallidum | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.03) | −0.01 (-0.02,0.01) | 0.34 (0.04) | 0.005 (-0.02,0.03) |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | |||||

| Parietal lobe | 2.70 (0.13) | 2.68 (0.12) | −0.01 (-0.08,0.05) | 2.67 (0.12) | −0.02 (-0.10,0.06) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.30 (0.12) | 2.25 (0.11) | −0.04 (-0.10,0.01) | 2.23 (0.11) | −0.06 (-0.13,0.01) |

| None | 1 to 2 hypoglycaemic events | ≥ 3 hypoglycaemic events | |||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | |

| N | 26 | 43 | 32 | ||

| Absolute brain volume (mm3) | |||||

| Total brain | 1,230,213 (109081) | 1,232,589 (123107) | 9977 (-44532,64487) | 1,212,496 (116765) | −7160 (-65613,51293) |

| Total white matter | 453,296 (48767) | 459,471 (53932) | 8946 (-16891,34782) | 452,233 (59408) | 2490 (-25215,30196) |

| Total grey matter | 777,151 (68437) | 773,307 (71617) | 965 (-31054,32983) | 760,264 (62741) | −9941 (-44275,24394) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 339,007 (28457) | 341,070 (37630) | 4313 (-12924,21549) | 331,888 (36766) | −4041 (-22524,14443) |

| Parietal lobe | 238,156 (23719) | 237,878 (29875) | 1466 (-12243,15174) | 233,751 (27443) | −1664 (-16364,13036) |

| Occipital lobe | 100,852 (11248) | 103,192 (12570) | 2847 (-3331,9026) | 98,137 (12936) | −2377 (-9002,4249) |

| Caudate | 8029 (1 7 3) | 7436 (1 3 4) | −552a (-1014,-91) | 7411 (1 5 6) | −564a (-1059,-69) |

| Putamen | 10,557 (1243) | 10,305 (1228) | −153 (-779,474) | 10,210 (1199) | −199 (-871,473) |

| Pallidum | 4126 (4 8 1) | 4051 (4 7 6) | −58 (-315,200) | 4103 (5 2 9) | 4 (-272,280) |

| Percent of total brain volume | |||||

| Total white matter | 36.82 (1.76) | 37.23 (1.15) | 0.41 (-0.44,1.25) | 37.20 (1.74) | 0.39 (-0.51,1.28) |

| Total grey matter | 63.20 (1.78) | 62.79 (1.15) | −0.41 (-1.26,0.43) | 62.80 (1.74) | −0.41 (-1.31,0.49) |

| Combined parietal and occipital lobes | 27.59 (1.03) | 27.67 (1.17) | 0.08 (-0.54,0.70) | 27.36 (1.11) | −0.23 (-0.89,0.43) |

| Parietal lobe | 19.37 (1.09) | 19.29 (1.35) | −0.08 (-0.75,0.60) | 19.27 (1.12) | −0.10 (-0.82,0.62) |

| Occipital lobe | 8.22 (0.79) | 8.38 (0.65) | 0.16 (-0.23,0.55) | 8.09 (0.67) | −0.13 (-0.54,0.28) |

| Caudate | 0.65 (0.06) | 0.61 (0.06) | −0.05a (-0.08,-0.02) | 0.61 (0.06) | −0.04a (-0.08,-0.01) |

| Putamen | 0.86 (0.07) | 0.84 (0.09) | −0.02 (-0.06,0.03) | 0.84 (0.08) | −0.01 (-0.06,0.03) |

| Pallidum | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.33 (0.03) | −0.01 (-0.02,0.01) | 0.34 (0.03) | 0.00 (-0.02,0.02) |

| Cortical thickness (mm) | |||||

| Parietal lobe | 2.70 (0.02) | 2.68 (0.02) | −0.02 (-0.08,0.05) | 2.68 (0.02) | −0.02 (-0.09,0.05) |

| Occipital lobe | 2.30 (0.02) | 2.24 (0.02) | −0.05 (-0.11,0.01) | 2.24 (0.02) | −0.05 (-0.11,0.02) |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) or mean difference (95% confidence interval). None, no evidence of hypoglycaemic events; Mild, blood or interstitial glucose concentrations between 2.0 and 2.6 mmol/L; Severe, blood or interstitial glucose concentrations < 2 mmol/L. Hypoglycaemic events are defined as the sum of nonconcurrent blood and interstitial episodes more than 20 min apart. A hypoglycaemic episode is defined as at least one consecutive blood glucose concentration < 2.6 mmol/L. Interstitial episodes are defined as at least 10 min of interstitial glucose concentrations < 2.6 mmol/L. aP < 0.05 for comparison with the None group (Dunnett).

4. Discussion

At 9–10 years of age, children who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had no difference in combined parietal and occipital lobe volume and white matter microstructure but had smaller caudate, thalamus and subcortical volumes, larger optic chiasm volume and thinner occipital lobe cortical thickness, compared to children who had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia. The finding of smaller caudate volumes was consistent across analyses of pre-specified hypoglycaemia severity groups, clinically detected hypoglycaemic episodes, and severity and frequency of hypoglycaemic events.

We expected to find changes in parietal and occipital structures, given previous publications showing diffuse parenchymal loss in the parietal-occipital lobes in neonates who had experienced severe or recurrent and symptomatic hypoglycaemia. (Spar et al., 1994, Alkalay et al., 2005, Kinnala et al., 1999, Traill et al., 1998) We found that children who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia had thinner occipital lobe cortical thickness, but no differences in parietal or occipital lobe volume. It is possible that cortical thickness is more sensitive to subtle changes after neonatal hypoglycaemia, since it is thought to reflect the size, density and arrangement of neurons, neuroglia, and nerve fibres of the grey matter. (Dale et al., 1999, Fischl and Dale, 2000) Nonetheless, volumes of the caudate, thalamus and subcortical grey matter were smaller in children who had experienced hypoglycaemia. Progressive loss of brain tissue volume following injury can take months to years. (Cole et al., 20182018) Deep grey matter regions such as the basal ganglia and thalamus are reportedly more vulnerable than other brain structures to selective neuronal damage due to neonatal insults, such as hypoxia and ischaemia, (Belet et al., 2004, Miller et al., 2005, Pasternak and Gorey, 1998, Roland et al., 1998, Sie et al., 2000) and are among the regions where volume loss is most commonly reported following traumatic brain injury. (Cole et al., 20182018, Gooijers et al., 2016, Bendlin et al., 2008) In children with neonatal encephalopathy, abnormal hyperintensities in the basal ganglia and thalamus on neonatal MRI were still observable at 9–10 years of age. (van Kooij et al., 2010) Alterations to the basal ganglia and thalamus based on MRI observation (Kinnala et al., 1999, Burns et al., 2008) and reduction in the number of nerve cells (Anderson et al., 1967, Banker, 1967) following neonatal hypoglycaemia have previously been reported. Thus, our findings could reflect neonatal hypoglycaemic injury in deep grey matter structures.

We did not find differences between children who had and had not experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia in any measures of white matter microstructure. Previous studies using diffusion MRI were based on visual inspection by experienced radiologists, and neuroimaging was performed during the acute phase of hypoglycaemia. (Kim et al., 2006, Filan et al., 2006, Mao and Chen, 2007) Low mean apparent diffusion coefficient values have been reported in mesial occipital regions in 8 of 25 neonates between 1 and 28 days of age. (Tam et al., 2008) The acute phase of hypoglycaemia causes swelling of neuronal and glial cells from cytotoxic edema, (Su and Wang, 2012) which reduces the spacing between the myelin fibre bundles, causing increased restriction of movement of water molecules transverse to the fibre orientation. (Gutierrez et al., 2010, Schabitz and Fisher, 1995) These changes can be detected using diffusion MRI, which is sensitive to intracellular water movements. However, recovery can involve cortical reorganization, neurogenesis, axonal sprouting, dendritic plasticity, and angiogenesis, (Conner et al., 2005, Ramanathan et al., 2006) which may not be detected using diffusion MRI. For example, a study of 18 neonates who had experienced hypoglycaemia reported that six had abnormal white matter hyperintensities during the neonatal period, of whom four had normal MRI findings at two months of age. (Kinnala et al., 1997) Thus, our findings of no effect on white matter microstructure at 9–10 years could indicate a process of recovery following early brain injury, or no injury to white matter microstructure following neonatal hypoglycaemia.

Girls who experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia were more likely to have smaller combined parietal and occipital lobes, whereas in boys the findings were consistent with the overall findings of smaller deep grey matter volumes. A previous study of transient neonatal hypoglycaemia reported that at six to nine years boys had significantly lower fine motor scores, whereas girls had higher internalizing scores on the Child Behaviour Checklist, although within the normal range. (Rasmussen et al., 2020) Sex differences in brain maturation (Lenroot et al., 2007) or neuroprotective effects of sex hormones in specific brain regions (Brann et al., 2007) could lead to girls and boys experiencing a different pattern of brain injury following neonatal hypoglycaemia. However, given that neonatal hypoglycaemia in girls was only associated with the combined parietal and occipital lobes, and not the lobes individually, and that there were no sex effects on white matter microstructure, it is hard to draw any firm conclusions. Further investigations of sex-specific effects of neonatal brain injury, including hypoglycaemia, are warranted.

We anticipated that children who experienced severe neonatal hypoglycaemia would show the greatest differences in brain structure in mid-childhood, but observed the associations primarily in the pre-specified mild and undetected groups who experienced less severe hypoglycaemia. The undetected hypoglycaemia group had low glucose concentrations that were detected only on masked CGM and therefore were not treated. This raises the possibility that treatment may prevent long term neurological effects. Likewise, it is plausible that infants with severe hypoglycaemia receive more monitoring and treatment than those with mild or undetected episodes, which may have mitigated brain injury. However, our analyses of clinically detected episodes and of severity and frequency of hypoglycaemic events makes this explanation unlikely, as both mild and severe episodes, and more severe and more frequent events, were all associated with smaller caudate volumes.

The caudate has afferent connections to the cerebral cortex, especially the prefrontal cortex, and efferent connections to the prefrontal cortex through the thalamus, globus pallidus, and substantia nigra. (Grahn et al., 2008) It plays a significant role in higher-order functioning, including emotion processing, learning and working memory. (Grahn et al., 2008, Graff-Radford et al., 2017) Caudate volume has been associated with intelligence quotient in 7 year old children born preterm (Abernethy et al., 2004) and cognitive performance at age 9–13 years in children with a history of prenatal heavy alcohol exposure. (Fryer et al., 2012) Furthermore, smaller caudate volumes have been reported in adults with schizophrenia (Li et al., 2018) and depression, (Bluhm et al., 2009) and related to impulse control and hyperactivity in children with attention deficit hyperactivity. (Tremols et al., 2008) The thalamus is considered the sensory and motor relay centre of the brain, which processes all sensory and motor information from the peripheral nervous system, except olfactory signals, before sending information to the cerebral cortex. (Torrico and Munakomi, 2019) In children born preterm, thalamus volume at term-equivalent age has been positively related to motor, intelligence quotient, and academic outcomes at seven years of age. (Loh et al., 2017) Thalamus volume has also been associated with visual motor integration scores. (Young et al., 2015, Martinussen et al., 2009) Smaller volumes of these deep grey matter structures could be reflective of previously reported impaired executive and visual-motor function at age 4.5 years in this cohort. (McKinlay et al., 2017) Additionally, neonatal hypoglycaemia has been associated with lower educational achievement, (Kaiser et al., 2015) language delay, (Haworth et al., 1976) motor development delay, (Wickström et al., 2018) and neurodevelopmental disorders, (Yalnizoglu et al., 2007, Wickström et al., 2018, Stenninger et al., 1998) all of which could potentially be linked to impaired function of the caudate and thalamus.

This is the first prospective cohort study with a large sample size to investigate brain structure and white matter microstructure in school-age children who had experienced neonatal hypoglycaemia. Strengths of the study include a high follow-up rate in the overall cohort, and children were randomly selected for MRI based on severity of hypoglycaemia and were born ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation to minimize the influence of preterm birth. All MRIs were conducted with the same acquisition protocol, scanner upgrades and similar MRI machines in one of two centres. Furthermore, we have detailed information regarding the duration, severity and frequency of low glucose concentrations through CGM monitoring, rather than relying on clinical testing alone. All data were analysed according to a predefined statistical analysis protocol.

TBSS is a fully automated method that is well suited to whole-brain group comparison, and we created a study specific template appropriate to the paediatric cohort. However, TBSS may reduce anatomical accuracy of the white matter structures compared to tractography methods and the tensor model is limited in crossing or fanning fibres. For the volumetric analyses, we chose regions we expected to be important, but may have lost some sensitivity by combining the left and right hemispheres to reduce the number of regions of interest. Additionally, we did not correct for multiple comparisons for volumetric analyses, so the findings should be interpreted with caution. However, the consistency of the association between neonatal hypoglycaemia and smaller caudate volume across all subgroup and sensitivity analyses suggests a true association. Another limitation is that none of the participants underwent neonatal MRI and neonatal hypoglycaemia was mostly mild and transient. Thus, although children in this study may not have experienced the kind of neonatal brain injury previously reported following symptomatic, severe and prolonged hypoglycaemia, the findings are more applicable to the majority of cases of neonatal hypoglycaemia which are mild and transient.

Overall, we found that neonatal hypoglycaemia is associated with reduced size of specific brain regions in mid-childhood and is not associated with altered white matter microstructure. These associations are seen in a cohort who were routinely screened and treated for neonatal hypoglycaemia with the intention of maintaining blood glucose concentrations ≥ 2.6 mmol/L, and most of whom experienced only mild, asymptomatic hypoglycaemia. Grey matter, and in particular deep grey matter regions, may be particularly vulnerable to the long term effects of even mild neonatal hypoglycaemia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Samson Nivins: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Eleanor Kennedy: Supervision, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft. Benjamin Thompson: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Gregory D. Gamble: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jane M. Alsweiler: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Russell Metcalfe: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Christopher J.D. McKinlay: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Jane E. Harding: Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the children and families who participated in this study. We would like to thank the CHYLD steering group for their input. [Members of the CHYLD Study Team: Steering group: Jane Harding, DPhil, Christopher McKinlay, PhD, Jane Alsweiler, PhD, Deborah Harris, PhD, Gavin Brown, PhD, J. Geoffrey Chase, PhD, Gregory Gamble, MSc, Trecia Wouldes, PhD, Peter Keegan, PhD, and Benjamin Thompson, DPhil; International advisory committee: Heidi Feldman, PhD, William Hay, MD, Robert Hess, PhD, and Darrell Wilson, MD; Other members of the CHYLD Mid-childhood Outcome Study team: Jason Turuwhenua, PhD, Jenny Rogers, MHSc, Steven Miller, MD, Eleanor Kennedy, PhD, Arijit Chakraborty, PhD, Jennifer Knopp, PhD, Rajesh Shah, PhD, Darren Dai, MSSc, Samson Nivins, MSc, Tony Zhou, PhD, Jocelyn Ledger, Stephanie Macdonald, BSc, Alecia McNeill BSc, Coila Bevan, BA, Nataliia Burakevych, PhD, Robin May, MPhil, Safayet Hossin, MSc, Grace McKnight, Rashedul Hasan, MSc, Jessica Wilson, MSc.]

Funding

Health Research Council of New Zealand (17/240); Neurological Foundation (1729PG), and Liggins Institute PhD scholarship (awarded to SN).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2022.102943.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Shah R., Harding J., Brown J., McKinlay C. Neonatal glycaemia and neurodevelopmental outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neonatology. 2019;115(2):116–126. doi: 10.1159/000492859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblath M., Hawdon J.M., Williams A.F., Aynsley-Green A., Ward-Platt M.P., Schwartz R., Kalhan S.C. Controversies regarding definition of neonatal hypoglycemia: suggested operational thresholds. Pediatrics. 2000;105(5):1141–1145. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh T.H.H.G., Aynsley-Green A., Tarbit M., Eyre J.A. Neural dysfunction during hypoglycaemia. Arch. Dis. Child. 1988;63(11):1353–1358. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.11.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas A., Morley R., Cole T.J. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcome of moderate neonatal hypoglycaemia. Br. Med. J. 1988;297(6659):1304–1308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6659.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spar, J.A., Lewine, J.D., Orrison, W.W., 1994, Neonatal hypoglycemia: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol.;15(8):1477-1478. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/798556 Accessed July 3, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alkalay A.L., Flores-Sarnat L., Sarnat H.B., Moser F.G., Simmons C.F. Brain imaging findings in neonatal hypoglycemia: case report and review of 23 cases. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila). 2005;44(9):783–790. doi: 10.1177/000992280504400906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkovich, A.J., Al Ali, F., Rowley, H.A., Bass, N., 1998, Imaging Patterns of Neonatal Hypoglycemia. Vol 19. http://www.ajnr.org/content/ajnr/19/3/523.full.pdf. Accessed June 26, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kinnala A., Rikalainen H., Lapinleimu H., Parkkola R., Kormano M., Kero P. Cerebral magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography findings after neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4 Pt 1):724–729. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.724. www.aappublications.org/news Accessed June 26, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traill Z., Squier M., Anslow P. Brain imaging in neonatal hypoglycaemia. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1998;79(2):F145–F147. doi: 10.1136/fn.79.2.F145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam E.W.Y., Widjaja E., Blaser S.I., MacGregor D.L., Satodia P., Moore A.M. Occipital lobe injury and cortical visual outcomes after neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):507–512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.Y., Goo H.W., Lim K.H., Kim S.T., Kim K.S. Neonatal hypoglycaemic encephalopathy: diffusion-weighted imaging and proton MR spectroscopy. Pediatr. Radiol. 2006;36(2):144–148. doi: 10.1007/s00247-005-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filan P.M., Inder T.E., Cameron F.J., Kean M.J., Hunt R.W. Neonatal hypoglycemia and occipital cerebral injury. J. Pediatr. 2006;148(4):552–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J., Chen L., Ying FuJ., Hua Li J., Dong Xue X. Clinical evaluation by MRI on the newborn infants with hypoglycemic brain damage. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2007;45(7):518–522. https://europepmc.org/article/MED/17953809 Accessed May 25, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns C.M., Rutherford M.A., Boardman J.P., Cowan F.M. Patterns of cerebral injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes after symptomatic neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):65–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inder T. How Low Can I Go? The Impact of Hypoglycemia on the Immature Brain. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2853. 1412-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y., Yamashita Y., Matsuishi T., Utsunomiya H., Okudera T., Hashimoto T. Cranial MRI of neurologically impaired children suffering from neonatal hypoglycaemia. Pediatr. Radiol. 1999;29(1):23–27. doi: 10.1007/s002470050527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yalnizoglu D., Haliloglu G., Turanli G., Cila A., Topcu M. Neurologic outcome in patients with MRI pattern of damage typical for neonatal hypoglycemia. Brain Dev. 2007;29(5):285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Per H., Kumandaş S., Çoskun A., Gümüş H., Öztop D. Neurologic sequelae of neonatal hypoglycemia in Kayseri, Turkey. J. Child Neurol. 2008;23(12):1406–1412. doi: 10.1177/0883073808319075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimzadeh P., Tabarestani S., Ghofrani M. Hypoglycemia-occipital syndrome: A specific neurologic syndrome following neonatal hypoglycemia? J. Child Neurol. 2011;26(2):152–159. doi: 10.1177/0883073810376245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam E.W.Y., Haeusslein L.A., Bonifacio S.L., Glass H.C., Rogers E.E., Jeremy R.J., Barkovich A.J., Ferriero D.M. Hypoglycemia is associated with increased risk for brain injury and adverse neurodevelopmental outcome in neonates at risk for encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2012;161(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu M.-H., Amanda F., Yuan T.-M. Brain injury in neonatal hypoglycemia: a hospital-based cohort study. Clin. Med. Insights Pediatr. 2019;13 doi: 10.1177/1179556519867953. 117955651986795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay C.J.D., Alsweiler J.M., Ansell J.M., Anstice N.S., Chase J.G., Gamble G.D., Harris D.L., Jacobs R.J., Jiang Y., Paudel N., Signal M., Thompson B., Wouldes T.A., Yu T.-Y., Harding J.E. Neonatal Glycemia and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes at 2 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373(16):1507–1518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinlay C.J.D., Alsweiler J.M., Anstice N.S., Burakevych N., Chakraborty A., Chase J.G., Gamble G.D., Harris D.L., Jacobs R.J., Jiang Y., Paudel N., San Diego R.J., Thompson B., Wouldes T.A., Harding J.E. Association of neonatal glycemia with neurodevelopmental outcomes at 4.5 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):972. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D.L., Weston P.J., Signal M., Chase J.G., Harding J.E. Dextrose gel for neonatal hypoglycaemia (the Sugar Babies Study): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9910):2077–2083. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris D.L., Battin M.R., Weston P.J., Harding J.E. Continuous glucose monitoring in newborn babies at risk of hypoglycemia. J. Pediatr. 2010;157(2):198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.L.R., Skare S., Ashburner J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):870–888. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale A.M., Fischl B., Sereno M.I. Cortical surface-based analysis: I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Liu A., Dale A.M. Automated manifold surgery: constructing geometrically accurate and topologically correct models of the human cerebral cortex. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2001;20(1):70–80. doi: 10.1109/42.906426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Salat D.H., van der Kouwe A.J.W., Makris N., Ségonne F., Quinn B.T., Dale A.M. Sequence-independent segmentation of magnetic resonance images. NeuroImage. 2004;23:S69–S84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S.S., Kakunoori S., Augustinack J., Nieto-Castanon A., Kovelman I., Gaab N., Christodoulou J.A., Triantafyllou C., Gabrieli J.D.E., Fischl B. Evaluating the validity of volume-based and surface-based brain image registration for developmental cognitive neuroscience studies in children 4 to 11years of age. Neuroimage. 2010;53(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.L.R., Sotiropoulos S.N. An integrated approach to correction for off-resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1063–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J.L.R., Graham M.S., Zsoldos E., Sotiropoulos S.N. Incorporating outlier detection and replacement into a non-parametric framework for movement and distortion correction of diffusion MR images. Neuroimage. 2016;141:556–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Jenkinson M., Johansen-Berg H., Rueckert D., Nichols T.E., Mackay C.E., Watkins K.E., Ciccarelli O., Cader M.Z., Matthews P.M., Behrens T.E.J. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B., Dale A.M. Measuring the thickness of the human cerebral cortex from magnetic resonance images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97(20):11050–11055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole J.H., Jolly A., de Simoni S., Bourke N., Patel M.C., Scott G., Sharp D.J. Spatial patterns of progressive brain volume loss after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain. 2018;141(3):822–836. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belet N., Belet U., İncesu L.ü., Uysal S., Özinal S., Keskin T.ü., Sunter A.T., Küçüködük Sukru. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: correlation of serial MRI and outcome. Pediatr. Neurol. 2004;31(4):267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S.P., Ramaswamy V., Michelson D., Barkovich A.J., Holshouser B., Wycliffe N., Glidden D.V., Deming D., Partridge J.C., Wu Y.W., Ashwal S., Ferriero D.M. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2005;146(4):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak J.F., Gorey M.T. The syndrome of acute near-total intrauterine asphyxia in the term infant. Pediatr. Neurol. 1998;18(5):391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(98)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland E.H., Poskitt K., Rodriguez E., Lupton B.A., Hill A. Perinatal hypoxic-ischemic thalamic injury: clinical features and neuroimaging. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44(2):161–166. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sie L.T.L., Van Der Knaap M.S., Oosting J., De Vries L.S., Lafeber H.N., Valk J. MR patterns of hypoxic-ischemic brain damage after prenatal, perinatal or postnatal asphyxia. Neuropediatrics. 2000;31(3):128–136. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooijers J., Chalavi S., Beeckmans K., Michiels K., Lafosse C., Sunaert S., Swinnen S.P. Subcortical volume loss in the thalamus, putamen, and pallidum, induced by traumatic brain injury, is associated with motor performance deficits. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2016;30(7):603–614. doi: 10.1177/1545968315613448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendlin B.B., Ries M.L., Lazar M., Alexander A.L., Dempsey R.J., Rowley H.A., Sherman J.E., Johnson S.C. Longitudinal changes in patients with traumatic brain injury assessed with diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging. Neuroimage. 2008;42(2):503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooij B.J.M., van Handel M., Nievelstein R.A.J., Groenendaal F., Jongmans M.J., de Vries L.S. Serial MRI and neurodevelopmental outcome in 9- to 10-year-old children with neonatal encephalopathy. J. Pediatr. 2010;157(2):221–227.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.M., Milner R.D., Strich S.J. Effects of neonatal hypoglycaemia on the nervous system: a pathological study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1967;30(4):295–310. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.30.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker B.Q. The neuropathological effects of anoxia and hypoglycemia in the newborn. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1967;9(5):544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1967.tb02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J., Wang L. Research advances in neonatal hypoglycemic brain injury. Transl. Pediatr. 2012;1(2):108–10815. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2012.04.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L.G., Rovira À., Portela L.A.P., Da Costa L.C., Lucato L.T. CT and MR in non-neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: radiological findings with pathophysiological correlations. Neuroradiology. 2010;52(11):949–976. doi: 10.1007/s00234-010-0728-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schabitz W.R., Fisher M. Diffusion weighted imaging for acute cerebral infarction. Neurol. Res. 1995;17(4):270–274. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1995.11740325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner J.M., Chiba A.A., Tuszynski M.H. The basal forebrain cholinergic system is essential for cortical plasticity and functional recovery following brain injury. Neuron. 2005;46(2):173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan D., Conner J.M., Tuszynski M.H. A form of motor cortical plasticity that correlates with recovery of function after brain injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103(30):11370–11375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601065103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnala A., Nuutila P., Ruotsalainen U., Teräs M., Bergman J., Haaparanta M., Solin O., Korvenranta H., Äärimaa T., Wegelius U., Kero P., Suhonen-Polvi H. Cerebral metabolic rate for glucose after neonatal hypoglycaemia. Early Hum. Dev. 1997;49(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(97)01875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A.H., Wehberg S., Pørtner F., Larsen A.M., Filipsen K., Christesen H.T. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after moderate to severe neonatal hypoglycemia. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020;179(12):1981–1991. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03729-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenroot R.K., Gogtay N., Greenstein D.K., Wells E.M., Wallace G.L., Clasen L.S., Blumenthal J.D., Lerch J., Zijdenbos A.P., Evans A.C., Thompson P.M., Giedd J.N. Sexual dimorphism of brain developmental trajectories during childhood and adolescence. Neuroimage. 2007;36(4):1065–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brann D.W., Dhandapani K., Wakade C., Mahesh V.B., Khan M.M. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective actions of estrogen: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Steroids. 2007;72(5):381–405. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahn J.A., Parkinson J.A., Owen A.M. The cognitive functions of the caudate nucleus. Prog. Neurobiol. 2008;86(3):141–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Radford J., Williams L., Jones D.T., Benarroch E.E. Caudate nucleus as a component of networks controlling behavior. Neurology. 2017;89(21):2192–2197. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abernethy L.J., Cooke R.W.I., Foulder-Hughes L. Caudate and hippocampal volumes, intelligence, and motor impairment in 7-year-old children who were born preterm. Pediatr. Res. 2004;55(5):884–893. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000117843.21534.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer S.L., Mattson S.N., Jernigan T.L., Archibald S.L., Jones K.L., Riley E.P. Caudate volume predicts neurocognitive performance in youth with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2012;36(11):1932–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]