Abstract

A duplex PCR assay targeting the ail and 16S rRNA genes of Yersinia enterocolitica was developed to specifically identify pathogenic Y. enterocolitica from pure culture. Validation of the assay was performed with 215 clinical Yersinia strains and 40 strains of other bacterial species. Within an assay time of 4 h, this assay offers a very specific, reliable, and inexpensive alternative to the conventional phenotypic assays used in clinical laboratories to identify pathogenic Y. enterocolitica.

Yersinia enterocolitica is an important human enteroinvasive pathogen with a global distribution (3, 5, 22). Worldwide surveillance data show an extensive increase in the number of non-outbreak-related isolates and cases of yersiniosis reported in the last two decades. This notice has led to the referral of Y. enterocolitica as a potential emerging enteric human pathogen worldwide (17, 22, 28).

In contrast to most other common bacterial enteropathogens, Y. enterocolitica is able to proliferate at temperatures of about 4°C. This psychrophilic nature is responsible for the survival of the bacterium at temperatures found in refrigerators, e.g., in food (1, 2, 5, 6) or packed red blood cells needed for transfusion (7, 14, 30). Pigs are regarded as a major reservoir of Y. enterocolitica, and in particular, the consumption of porcine tongue and tonsils is considered a risk factor (1, 5, 6). The clinical spectrum of Y. enterocolitica infections varies with age and underlying conditions (3). Most commonly, yersiniosis is associated with gastroenteritis, although in children more severe clinical manifestations (peritonitis, ileitis, pseudoappendicitis) are observed and several fatalities have been reported (3, 16, 26). Due to the tropism for lymphoid tissues and the spread of the bacterium via the bloodstream, generalized infections may occur, resulting in meningitis, endocarditis, and aneurysm (15, 27). As a result of the host's immune response, Y. enterocolitica may also induce secondary, postinfectious sequelae such as erythema nodosum and acute and chronic arthritis (23, 29). An extensive overview of the pathogenic mechanisms of this versatile human pathogen has recently been described by Goverde (9).

Y. enterocolitica may be separated by serotyping into approximately 60 serogroups, of which only 11 serogroups are most frequently associated with human infections (with serogroups O:3, O:8, O:9, and O:5,27 predominating) (5, 31). One group of pathogenic strains, comprising serotypes O:4, O:8, O:13a/b, O:18, O:20, and O:21, was initially mainly isolated in the United States. On the other hand, strains that were the most common causes of yersiniosis in Europe and Japan, i.e., serotypes O:3 and O:9, were virtually unknown in the United States. Only one pathogenic serotype, i.e., O:5,27, seemed to have a global spread from the very beginning. Since the early 1980s, however, the distinction between “American” and “non-American” strains has been fading (5, 9, 31).

Of the six biotypes of Y. enterocolitica, five (biotypes 1B, 2, 3, 4, and 5) are considered pathogenic in humans (4, 9, 18). Strains of these pathogenic biotypes contain markers associated with virulence, and these are located on the chromosome and on the pYV virulence plasmid (10, 18).

The sequence of events following ingestion of virulent Y. enterocolitica strains that ultimately leads to multiplication in underlying tissues and entrance into the bloodstream starts with adherence to and invasion of intestinal epithelial cells (preferentially from the ileum). These first steps of infection require at least two chromosomal factors, called ail (attachment invasion locus) and inv (invasion). The inv gene is present in virulent as well as nonvirulent strains of Y. enterocolitica, whereas the ail gene is found only in the pathogenic serotypes of Y. enterocolitica (18, 19). The mode of action of the ail product, Ail, which is an outer membrane protein, has not been elucidated so far.

Expression of both plasmid and chromosomal genes is required for Y. enterocolitica virulence (18, 24). However, the plasmid has been shown to be difficult to maintain during laboratory culture, which would increase the chances of obtaining a false-negative result (8, 13). Consequently, plasmid pYV is not an ideal DNA target for the detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains. The chromosomal ail gene, however, has been shown to be a stable virulence marker limited to only invasive and, thus, pathogenic strains of Y. enterocolitica (10). Accordingly, amplification of ail-specific sequences by diagnostic PCR can be used for the unambiguous identification of invasive Y. enterocolitica strains. Miller et al. (20) elucidated the nucleotide sequence of the Y. enterocolitica ail gene in 1990. Besides the ail primers, we included in the PCR mixture a second primer set, based on the Y. enterocolitica 16S rRNA gene, for species identification. In this report, we describe the development of a rapid and sensitive duplex PCR assay that is specific for the detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial species and culture conditions.

A total of 215 clinical strains belonging to eight different species of the genus Yersinia were studied along with 40 non-Yersinia strains (Table 1). The isolates were selected from the bacterial collection of the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands). Of the Yersinia strains tested, about 70% were of human origin, whereas the remaining 30% originated from animals (mainly pigs). Furthermore, 15 Yersinia type (reference) strains were selected from the collections of the Institut Pasteur (National Reference Laboratory and World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Yersinia, Paris, France) and the University of Louvain (Brussels, Belgium) (Table 2). Fresh Yersinia cultures were prepared by overnight incubation on Cefsulodin-Irgasan-Novobiocin (CIN) agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) at 30°C. Strains were stored at −70°C in peptone broth with 25% (vol/vol) glycerol. The type strains used to test the specificity of the ail PCR were Listeria monocytogenes (NCTC 7973), Shigella dysenteriae (NCTC 11867), Campylobacter jejuni (NCTC 11168), Escherichia coli (CDC P2a), and Salmonella enterica (Institut Pasteur strain 5338/85).

TABLE 1.

Specificities of the two candidate primer sets for Y. enterocolitica

| Species | Serotype (O group) | No. of strains tested | PCR result

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y. enterocolitica (Y1-Y2 primer pair) | ail gene (A1-A2 primer pair) | |||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:3 | 37 | + | + |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:4 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:5 | 14 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:5,27 | 8 | + | + |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:6,30 | 11 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:6,31 | 4 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:7,8 | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:7,13b | 7 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:8 | 1 | + | −a |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:8 | 3 | + | + |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:9 | 4 | + | −a |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:9 | 35 | + | + |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:12,25 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:13b | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:13a,18 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:14 | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:16a,58 | 7 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:17 | 1 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:28,50 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:34,46 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:36 | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:36,59 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:40 | 4 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:41,42 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:41,43 | 6 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:43 | 1 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:47 | 2 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:48 | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | O:59 | 3 | + | − |

| Yersinia bercovieri | Diverse | 6 | − | − |

| Yersinia frederiksenii | Diverse | 6 | − | − |

| Yersinia intermedia | Diverse | 6 | − | − |

| Yersinia kristensenii | Diverse | 6 | − | − |

| Yersinia mollarettii | O:22,62 | 2 | − | − |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | Diverse | 10 | − | − |

| Yersinia rohdei | NDb | 2 | − | − |

| Campylobacter jejuni | O:1,44 | 3 | − | − |

| Escherichia coli | O:157 | 5 | − | − |

| Legionella pneumophila | O:1 | 5 | − | − |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1/2a | 5 | − | − |

| Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica | Enteritidis | 10 | − | − |

| Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica | Typhimurium | 10 | − | − |

| Shigella dysenteriae | O:14 | 1 | − | − |

| Shigella flexneri | O:6 | 1 | − | − |

Biotype 1A (nonpathogenic).

ND, not determined.

TABLE 2.

Type strains belonging to six different Yersinia species used in the study

| Species | Biotype | Serotype | Origina | Results of PCR that targets:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA | ail | ||||

| 1. Y. enterocolitica | 1A | O:5 | IP-124 | + | − |

| 2. Y. enterocolitica | 1A | O:8 | IP-1105 | + | − |

| 3. Y. enterocolitica | 1B | O:18 | IP-846 | + | + |

| 4. Y. enterocolitica | 1B | O:20 | IP-845 | + | + |

| 5. Y. enterocolitica | 1B | O:21 | IP-1110 | + | + |

| 6. Y. enterocolitica | 2 | O:5,27 | IP-885 | + | + |

| 7. Y. enterocolitica | 2 | O:9 | IP-383 | + | + |

| 8. Y. enterocolitica | 3 | O:1,2,3 | IP-64 | + | + |

| 9. Y. enterocolitica | 4 | O:3 | IP-134 | + | + |

| 10. Y. enterocolitica | 5 | O:2,3 | IP-178 | + | + |

| 11. Y. bercovieri | —b | O:16A,58 | IP-7506 | − | − |

| 12. Y. frederiksenii | — | O:44,45 | IP-7210 | − | − |

| 13. Y. intermedia | — | O:40 | IP-2677 | − | − |

| 14. Y. kristensenii | — | O:11 | IP-105 | − | − |

| 15. Y. mollarettii | — | O:19,20,36,59 | WA-751 | − | − |

IP, Institut Pasteur; WA, University Louvain.

—, not applicable.

DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was isolated with the QiaAmp Tissue Kit 250 (Qiagen Inc., Leusden, The Netherlands), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Purified genomic DNA was diluted to a concentration of 10 ng/μl in TE buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) and stored at −20°C.

Primer design.

Two primer sets (primers A1 and A2 and primers Y1 and Y2) were used in the multiplex PCR assay. Primers A1 (5′-TTA ATG TGT ACG CTG GGA GTG-3′) and A2 (5′-GGA GTA TTC ATA TGA AGC GTC-3′), directed against the Y. enterocolitica ail gene, were deduced from sequences in the EMBL database (EMBL accession number M29945). On the basis of this sequence, a PCR product of 425 bp was expected. To specifically amplify the Y. enterocolitica 16S rRNA gene, a second primer set, recently published by Neubauer et al. (21), Y1 (5′-AAT ACC GCA TAA CGT CTT CG-3′) and Y2 (5′-CTT CTT CTG CGA GTA ACG TC-3′), was used, resulting in a PCR product of 330 bp.

PCR conditions.

Precautions were taken to use sterile reagents and conditions wherever possible. Each 25-μl PCR mixture contained ail-specific primers at a concentration of 160 nM and the Y. enterocolitica 16S rRNA-specific primers at a concentration of 80 nM; dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP each at a concentration of 200 μM; 0.5 U of SuperTaq Polymerase (Sphaero-Q, Leiden, The Netherlands); 1× PCR buffer (the buffer was supplied at 10×), and 2 μl (i.e., 20 ng) of DNA sample. Amplification was performed in a Primus 96 Plus thermal cycler (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Cycling conditions started with a denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min, which was followed by 36 subsequent cycles consisting of heat denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, primer annealing at 62°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s. A final extension was performed at 72°C for 7 min to complete the synthesis of all strands. The PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide.

RESULTS

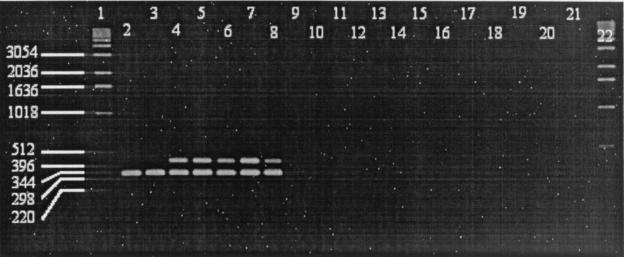

A duplex PCR approach was used for the detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica. The first primer pair (the A1-A2 primer pair) was used to amplify a 0.43-kb fragment of the ail gene, found exclusively in pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains, whereas the second primer pair (the Y1-Y2 primer pair) amplified a 0.33-kb fragment of the 16S rRNA gene exclusively of the Y. enterocolitica species (Fig. 1). The entire test could be completed in 4 h, including the DNA extraction step.

FIG. 1.

Example of agarose gel electrophoresis of PCRs. Lanes 1 and 22, molecular sizes in base pairs (Roche Diagnostics, Almere, The Netherlands). Each lane was loaded with 20 μl of a 25-μl PCR mixture. Lane 2, Y. enterocolitica O:5, biotype 1A (IP-124); lane 3, Y. enterocolitica O:8, biotype 1A (IP-1105); lane 4, Y. enterocolitica O:5,27, biotype 2 (IP-885); lane 5, Y. enterocolitica O:9, biotype 2 (IP-383); lane 6, Y. enterocolitica O:1,2,3, biotype 3 (IP-64); lane 7, Y. enterocolitica O:3, biotype 4 (IP-134); lane 8, Y. enterocolitica O:2,3, biotype 5 (IP-178); lane 9, Y. bercovieri (IP-7506); lane 10, Y. frederiksenii (IP-7210); lane 11, Y. intermedia (IP-2677); lane 12, Y. kristensenii (IP-105); lane 13, Y. mollaretii (WA-751); lane 14, S. flexneri; lane 15, Shigella boydii; lane 16, S. dysenteriae; lane 17, L. monocytogenes; lane 18, C. jejuni; lane 19, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium; lane 20, E. coli; lane 21, no template control.

Theoretical detection limit of PCR.

In order to determine the sensitivity of the assay, chromosomal DNA from Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3 was isolated with the QiaAmp kit from overnight cultures of bacteria grown in CIN medium at 30°C. Duplex PCR was performed by using 100 ng to 1 fg of chromosomal DNA as a template and the primers described above. A DNA concentration of ≥5 fg could be detected (data not shown). On the basis of an average yersinial genome size of 4,500 kb (25), 5 fg of DNA would amount to approximately one genome and, hence, one bacterial cell.

Specificity of PCR.

The specificity of the duplex PCR assay was examined by isolating genomic DNA from 27 different Y. enterocolitica serogroups, 7 different other Yersinia spp., and 6 different non-Yersinia bacteria pathogenic for humans (Tables 1 and 2). Among the 34 different Yersinia strains, only Y. enterocolitica isolates gave a PCR product of 0.33 kb. Of these, only pathogenic strains (mainly serogroup O:3, O:8, O:9, and O:5,27) gave an additional PCR product of 0.43 kb. No PCR products were observed when non-Yersinia strains were used. The results of the 16S rRNA gene PCR correlated well with the results obtained by Neubauer et al. (21). The retrieval of the PCR product derived from the ail gene only from pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains indicates the uniqueness of this virulence gene among this yersinial species.

DISCUSSION

The objective of the present study was to design a sensitive and specific single-reaction PCR assay for the detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains and to use the assay as a diagnostic tool for the rapid typing of pure yersinial cultures.

The Y1-Y2 primer pair differentiated Y. enterocolitica from a broad spectrum of both Yersinia and non-Yersinia bacteria. The A1-A2 primer pair intrinsically differentiated pathogenic from nonpathogenic Y. enterocolitica bacteria. About 40% of the Y. enterocolitica isolates used in the present study had previously been subjected to tissue culture invasion (TCI) testing by Goverde (9); the results showed a 100% correlation between invasiveness and the serotypes associated with disease. This was in agreement with the results obtained by Miller and colleagues (18, 19) and strongly supports the hypothesis that the TCI+ phenotype corresponds to in vivo pathogenicity.

By our PCR method, in contrast to fluorogenic PCR assays, no post-PCR data analysis is needed. Both primer sets were able to detect Y. enterocolitica in pure culture at a limit of 5 fg of chromosomal DNA, demonstrating that conventional PCR can be as sensitive as fluorogenic PCR (11, 12). Compared to the nonfluorogenic ail PCR of Harnett et al. (11), the detection limit of our PCR seems to be superior (1 pg versus 5 fg of DNA).

The duplex PCR assay provides a more rapid means of accurate identification of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica than present standard methods (i.e., biotyping combined with serotyping), which are time-consuming and laborious. Use of the duplex PCR would significantly reduce the amount of time required to identify pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains and can be used directly after primary selective culture of this pathogen, with the biotyping and serotyping steps omitted, if necessary.

The (rare) presence of a homologous ail locus has been suggested in strains of Y. pseudotuberculosis (19). Therefore, it cannot be excluded that in our duplex PCR the ail product was found, while no 16S rRNA PCR product appeared. Unfortunately, there are insufficient sequence data for Yersinia spp. other than Y. enterocolitica to prove that they may harbor the ail gene or a version of it (12). None of the 10 Y. pseudotuberculosis strains tested in our study gave a PCR product with the ail-specific primer set.

Some small differences in amino acid composition at the ail locus between the American and non-American serotypes have been discussed (9, 11) and could in theory interfere with primer annealing. Nevertheless, the duplex PCR described in this report is able to unambiguously identify both American and non-American pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains.

Thus far, only separate 16S rRNA gene and ail gene PCRs have been described for Y. enterocolitica (11, 12, 21, 25). Without the 16S rRNA gene PCR, species confirmation must be obtained by biotyping and serotyping; with our assay it is possible to omit these steps, and therefore, the assay can save time. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a PCR assay that makes use of combined primer sets for both Yersinia species identification and detection of pathogenicity has been described.

In summary, the duplex PCR assay described in this report appears to be a useful tool for the rapid, sensitive, and specific detection of pathogenic Y. enterocolitica. In addition, it can be applied in each laboratory with PCR facilities, even without prior biotyping and serotyping.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. H. A. M. van Hoek and H. J. M. Aarts from the RIKILT Institute, Wageningen, The Netherlands, for providing some of the Yersinia isolates. We also thank F. A. G. Reubsaet and J. F. P. Schellekens from the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, The Netherlands, for helpful comments on preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adesiyun A A, Krishnan C. Occurrence of Yersinia enterocolitica O:3, Listeria monocytogenes O:4 and thermophilic Campylobacter spp. in slaughter pigs and carcasses in Trinidad. Food Microbiol. 1995;12:99–107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bien J P. Anticipatory guidance and chitterlings. J Pediatr. 1998;133:712. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottone E J. Yersinia enterocolitica: a panoramic view of a charismatic micro-organism. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1977;5:211–241. doi: 10.3109/10408417709102312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottone E J. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:257–276. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bottone E J. Yersinia enterocolitica: overview and epidemiologic correlates. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:323–333. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Incidence of foodborne ilnesses—Foodnet 1997. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:782–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: Yersinia enterocolitica bacteraemia and endotoxin shock associated with red blood cell transfusions—United States, 1991. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;40:176–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenwick S G, Murray A. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet. 1991;337:497–498. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93436-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goverde R L J. Yersinia enterocolitica: genes involved in cold-adaptation. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht, The Netherlands: University of Utrecht; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant T, Bennett-Wood V, Robins-Browne R M. Identification of virulence-associated characteristics in clinical isolates of Yersinia enterocolitica lacking classical virulence markers. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1113–1120. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1113-1120.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harnett N, Lin Y P, Krishnan C. Detection of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica using the multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:59–67. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800001138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jourdan A D, Johnson S C, Wesley I V. Development of a fluorogenic 5′ nuclease PCR assay for detection of the ail gene of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3750–3755. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.9.3750-3755.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapperund G. Yersinia enterocolitica in food hygiene. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;12:53–66. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90047-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein H G, Dodd R Y, Ness P M, Fratantoni J A, Nemo G J. Current status of microbial contamination of blood components: summary of a conference. Transfusion. 1997;37:95–101. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37197176958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.La Scola B, Musso D, Carta A, Piquet P, Casalta J P. Aortoabdominal aneurysm infected by Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:9. J Infect. 1997;35:314–315. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)93536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin T, Kasian G F, Stead S. Family outbreak of yersiniosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:622–626. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.622-626.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy M D, Fenwick S G. Experiences with the diagnosis of Yersinia enterocolitica—an emerging gastrointestinal pathogen in the Auckland area 1987–1989. NZ J Med Lab Sci. 1990;45:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller V L, Falkow S. Evidence for two genetic loci in Yersinia enterocolitica that can promote invasion of epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1242–1248. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1242-1248.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller V L, Farmer J J, Hill W E, Falkow S. The ail locus is found uniquely in Yersinia enterocolitica serotypes commonly associated with disease. Infect Immun. 1989;57:121–131. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.1.121-131.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller V L, Bliska J B, Falkow S. Nucleotide sequence of the Yersinia enterocolitica ail gene and characterization of the Ail protein product. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1062–1069. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1062-1069.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neubauer H, Hensel A, Aleksic S, Meyer H. Identification of Yersinia enterocolitica within the genus Yersinia. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23:58–62. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostroff S M. Yersinia as an emerging infection: epidemiologic aspects of yersiniosis. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1995;13:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrus M, Micheau P, Danjoux M F, Thore B, Rhabbour M, Moulie N, Bildstein G, Netter J C. Succession arthrite purulente puis reactionelle a Yersinia enterocolitica chez un garcon de 8 ans. Sem Hop Paris. 1997;73:286–288. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schiemann D A, Devenish J A. Relationship of HeLa cell infectivity to biochemical, serological and virulence characteristics of Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1982;35:497–506. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.497-506.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sen K. Rapid identification of Yersinia enterocolitica in blood by the 5′ nuclease PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1953–1958. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1953-1958.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staatz G, Alzen G, Heimann G. Darminfektion, die haufigste Invaginationsursache im Kindesalter: Ergebnisse einer 10-jahrigen klinischen Studie. Klin Paediatr. 1998;210:61–64. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1043851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tame S, de Wit D, Meek A. Yersinia enterocolitica and mycotic aneurysm. Aust NZ J Surg. 1998;68:813–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tauxe R V. Emerging foodborne diseases: an evolving public health challenge. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:425–434. doi: 10.3201/eid0304.970403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Heyden I M, Res P C M, Wilbrink B, Leow A, Breedveld F C, Heesemann J, Tak P P. Yersinia enterocolitica: a cause of chronic polyarthritis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:831–837. doi: 10.1086/515535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner S J, Friedman L I, Dodd R Y. Transfusion-associated bacterial sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:290–302. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.3.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wauters G, Aleksic S, Charlier J, Schulze G. Somatic and flagellar antigens of Yersinia enterocolitica and related species. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1991;12:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]