SUMMARY

Activation of the innate immune system via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) is key to generate lasting adaptive immunity. PRRs detect unique chemical patterns associated with invading microorganism, but if and how the physical properties of PRR ligands influence development of the immune response remains unknown. Through the study of fungal mannans we show that the physical form of PRR ligands dictates the immune response. Soluble mannans are immunosilent in the periphery but elicit a potent pro-inflammatory response in the draining lymph node (dLN). By modulating the physical form of mannans, we developed a formulation that targets both the periphery and dLN. When combined with viral glycoprotein antigens, this mannan formulation broadens epitope recognition, elicits potent antigen-specific neutralizing antibodies, and confers protection against viral infections of the lung. Thus, the physical properties of microbial ligands determine the outcome of the immune response and can be harnessed for vaccine development.

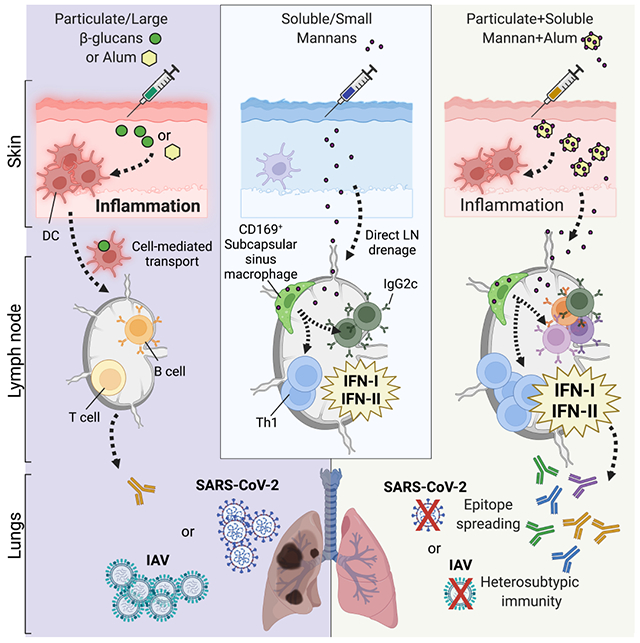

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Modulating the physical form of fungal mannans improves lymph node targeting and improves the adjuvant properties of these immune stimuli when included in vaccine formulations against respiratory viruses.

INTRODUCTION

The dialogue between the innate and adaptive branches of the immune system is critical for protection against infections as well as the pathogenesis of autoimmune, allergic, and inflammatory diseases (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004; Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002; Matzinger, 1994). Peripheral tissue infection and/or damage leads to activation and migration of innate immune phagocytes to the draining lymph node (dLN), where they initiate an antigen-dependent adaptive immune response. Alternatively, innate stimuli or microbes with specific physical properties (e.g., diameter in the nanometer range) can directly drain to the dLN and activate LN-resident innate and adaptive immune cells (Bachmann and Jennings, 2010; Irvine et al., 2020). The dLN has been thoroughly scrutinized for its capacity to host adaptive immune responses, but recent reports indicate that the antigen-dependent adaptive immune response is preceded and supported by an antigen-independent LN innate response (Acton et al., 2014; Coccia et al., 2017; De Giovanni et al., 2020; Didierlaurent et al., 2014; Kastenmuller et al., 2012; Leal et al., 2021; Lian et al., 2020; Lynn et al., 2015; Martin-Fontecha et al., 2004; Soderberg et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2015b). The LN innate response allows antigen-independent LN expansion, establishment of a pro-inflammatory milieu and the development of an effective adaptive immune response (Acton and Reis e Sousa, 2016; Grant et al., 2020). It remains a mystery if, and how, the LN innate response may differ when it is driven by migration of phagocytes from the periphery as opposed to when it is governed by the direct targeting of LN-resident innate immune cells.

Innate immune cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) (Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002) via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (Brubaker et al., 2015). PRR activation is critical for triggering inflammation and for the ensuing development of adaptive immune responses. For this reason, targeting of PRRs has been harnessed for vaccine development (O’Hagan et al., 2020). Among PRRs, the biology of C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) and their potential as vaccine adjuvant targets has been less investigated.

CLRs control innate and adaptive immune responses to fungal infection through recognition of cell wall polysaccharides (Borriello et al., 2020; Brown et al., 2018). The CLRs Dectin-1 (Clec7a) and Dectin-2 (Clec4n) are activated by β-glucans and mannans, respectively. These fungal polysaccharides vary not only by chemical structure, but also by physical form (e.g., size and solubility). Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 bind fungal polysaccharides in soluble as well as insoluble forms, but only the latter induces efficient receptor clustering and activation (Goodridge et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013). Consequently, it is widely held that only particulate polysaccharides are immunostimulatory. In this study we re-examined this paradigm and show that the quality of LN innate and adaptive immune responses can be tuned by modulating the physical properties of fungal ligands, providing a promising approach for adjuvant design and vaccine development.

RESULTS

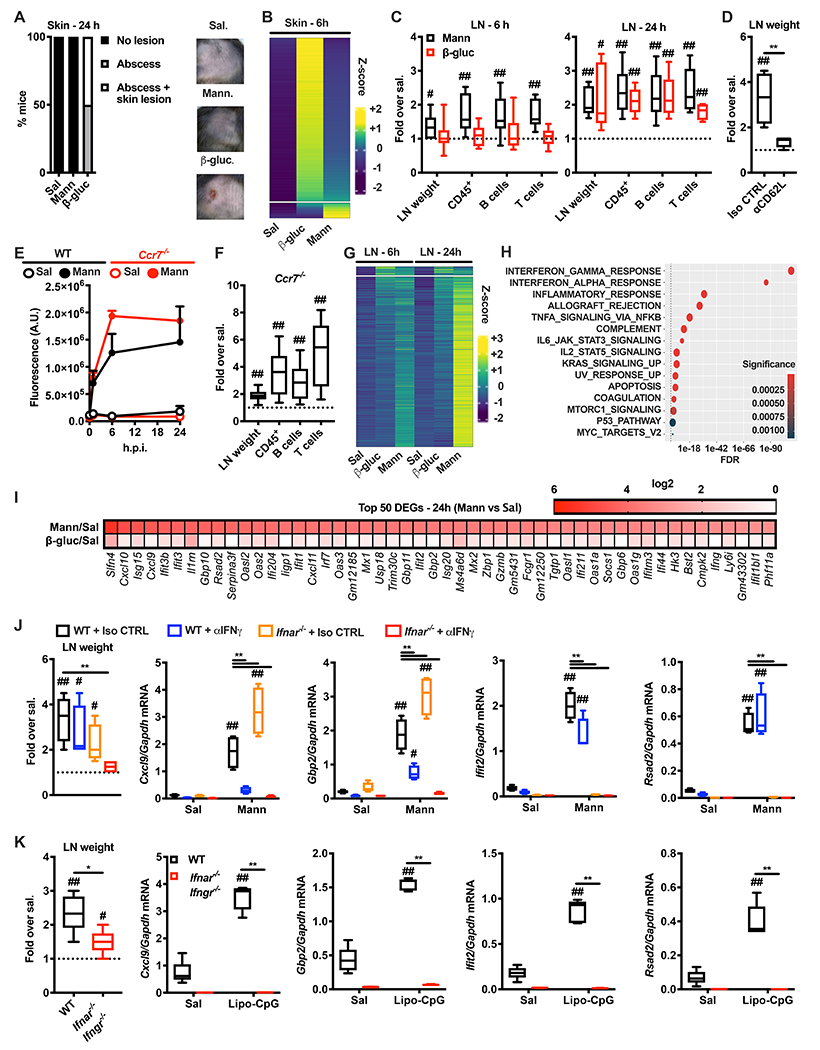

Mannans elicit LN-restricted IFN signatures that drive LN expansion

We employed preparations of β-glucans and mannans isolated from Candida albicans that exhibit distinct physical forms, being insoluble (with a diameter of ~500 nm) and soluble (with a diameter of ~20 nm) (Figure S1A). Particulate β-glucans, but not soluble mannans, elicited cytokine production and expression of co-stimulatory molecules by phagocytes in vitro (Figure S1B). As expected, signaling by β-glucans required Dectin-1 (Figure S1C). In contrast to soluble mannans, immobilization of mannans onto microbeads resulted in Dectin-2 and FcRγ-dependent activation of phagocytes (Figure S1C, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and curdlan were used as controls). Accordingly, β-glucans elicited formation of skin abscesses and lesions upon in vivo intradermal injection, whereas mannans did not (Figure 1A). These results were confirmed by transcriptomic analysis of skin samples (Figure 1B and Table S1. Pathway analysis of the cluster of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) upregulated by β-glucans showed enrichment for pro-inflammatory and type II interferon (IFN) pathways, consistent with the response elicited by C. albicans skin infection (Figure S1D) (Santus et al., 2017). While soluble mannans did not induce skin inflammation, these fungal ligands induced dLN expansion and lymphocyte accrual as early as 6 hours post-injection (h.p.i.), which was sustained at 24 h.p.i. (Figure 1C and Figure S2A–C) and dependent on circulating leukocyte recruitment (Figure 1D). β-glucans also elicited LN expansion but only at 24 h.p.i. (Figure 1C and Figure S2A–C). Both fungal ligands increased the numbers of myeloid cells in the dLN (Figure S2D–G), with β-glucans preferentially increasing neutrophils, possibly reflecting drainage from the skin (Figure S2D). However, only mannans induced activation of myeloid cells, as measured by increased CD86 expression (Figure S2H). Considering the fast response and the diameter compatible with lymphatic drainage, we reasoned that mannans might activate LN-intrinsic circuits that eventually lead to dLN expansion. In keeping with this hypothesis, mannans rapidly accumulated in the dLN (Figure 1E) and induced dLN expansion even in Ccr7−/− mice (Figure 1F) in which migration of immune cells from the periphery (i.e. skin) to the dLNs is abolished (Ohl et al., 2004). A transcriptomic analysis of dLNs showed a completely opposite profile compared to the skin, with mannans eliciting an earlier and more pronounced response compared to β-glucans (Figure 1G, Table S2). Pathway analysis showed that mannans upregulated type I and II IFN pathways (Figure 1H, I).

Figure 1. Mannans elicit lymph node-restricted IFN signatures that drive lymph node expansion.

(A) Mice were injected intradermally with saline (Sal), mannans (Mann) or β-glucans (β-gluc). 24 hours later the injection site was assessed for the presence of an abscess with or without skin lesion. The graph depicts percentages of mice in each of the indicated categories. Representative pictures of skin appearance at injection sites of saline, mannans and β-glucans are also shown. N = 5 mice per group. (B) Transcriptomic analysis of skin samples collected 6 hours after injection of saline (Sal), β-glucans (β-gluc) or mannans (Mann). Heatmap of abundance (z-scored log2 normalized counts) of genes induced by β-glucans and/or mannans compared to saline control, ranked by abundance difference between β-glucans and mannans. The gap splits the genes into two clusters, one that is highly upregulated by β-glucans and one that is highly upregulated by mannans. N = 3 mice per group. (C) Mice were injected intradermally with saline, mannans (Mann) or β-glucans (β-gluc). 6 or 24 hours later dLNs were collected and analyzed for weight as well as absolute numbers of CD45+, B and T cells. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 5-9 mice per group. (D) Mice were injected intravenously with a blocking anti-CD62L antibody (αCD62L) or the same dose of an isotype control (Iso CTRL) one day before intradermal injections of saline or mannans. 24 hours later dLNs were collected and their weights were measured. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 4 mice per group. (E) WT and Ccr7−/− mice were intradermally injected with saline (Sal) or fluorescently labelled mannans (Mann). 1, 6 and 24 hours later dLNs were collected and homogenized to measure total fluorescence. Results are expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.) of fluorescence and shown as mean + SEM. N = 3 mice per timepoint. (F) Ccr7−/− mice were injected intradermally with saline or mannans. 24 hours later dLNs were collected and analyzed as indicated in C. N = 6 mice. (G) Transcriptomic analysis of dLNs collected 6 and 24 hours after intradermal injection of saline (Sal), β-glucans (β-gluc) or mannans (Mann). Heatmap of abundance (z-scored log2 normalized counts) of genes induced by β-glucans and/or mannans compared to saline control, ranked by abundance difference between β-glucans and mannans. The gap splits the genes into two clusters, one that is highly upregulated by β-glucans and one that is highly upregulated by mannans. N = 4-5 mice per group. (H) Pathway enrichment analysis of genes belonging to the cluster upregulated by mannans as depicted in G. (I) Heatmap representation of the average expression levels of the top 50 genes upregulated in mannan-treated dLNs 24 hours after the injection compared to the saline control. N = 4-5 mice per group. (J) WT and Ifnar−/− mice were intravenously injected with an anti-IFNγ blocking antibody (αIFNγ) or the same dose of an isotype control (Iso CTRL) on day −1 and 0. On day 0 mice were also intradermally injected with saline (Sal) or mannans (Mann). 24 hours later dLNs were collected, their weights were measured, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN (weight) or as relative expression compared to Gapdh. N = 4 mice per group. (K) WT and Ifnar−/− Ifngr−/− mice were intradermally injected with saline (Sal) or Lipo-CpG. Samples were collected and analyzed as in J. N = 5 mice per group. # and ## respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing each group against the value 1 (which represent the contralateral control sample expressed as fold). * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing among different experimental groups. See also Figure S1, S2, S3 and Table S1 and S2.

The presence of type II IFN (IFNγ)-producing cells in mannan-treated dLN was confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure S2I). The majority of IFNγ-producing cells were CD8+ T and NK cells (Figure S2J), with NK cells expressing IFNγ at higher levels (Figure S2K). When NK cells were depleted, expression of Ifng was impaired (Figure S2L). cDC1 produce cytokines that induce NK cell activation and IFNγ production (Cancel et al., 2019) and may therefore contribute to the response induced by mannans. Nevertheless, Batf3−/− mice that lack cDC1 showed no impairment of mannan-elicited Ifng expression (Figure S2M). Notably, NK cell depletion only partially affected LN expansion and cell accrual (Figure S2N. In keeping with this, IFNγ blockade only partially reduced mannan-induced expansion of LN (Figure 1J). We therefore tested whether the absence of both IFNγ and type I IFN signaling impacted the LN innate response. Simultaneous blockade of both IFN types prevented mannan-elicited LN expansion and induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Figure 1J). This mechanism was not restricted to mannans, since LN expansion and induction of ISGs elicited by Lipo-CpG, a well characterized LN-targeted Toll-like receptor (TLR)9 ligand (Liu et al., 2014), were also impaired in Ifnar−/− Ifngr−/− mice (Figure 1K). To further establish whether these differences are due to distinct physical forms of fungal polysaccharides, we evaluated the response to whole glucan particles (WGP) in dispersible (D) or soluble (S) forms, which have been characterized as Dectin-1 agonists and antagonists, respectively (Goodridge et al., 2011). Consistent with the pattern observed with mannans, WGP-S did not induce skin inflammation (Figure S3A) but elicited LN expansion and ISG expression (Figure S3B). Altogether, these results support a model in which the physical form of PAMPs drive expansion of the dLN and ISG induction.

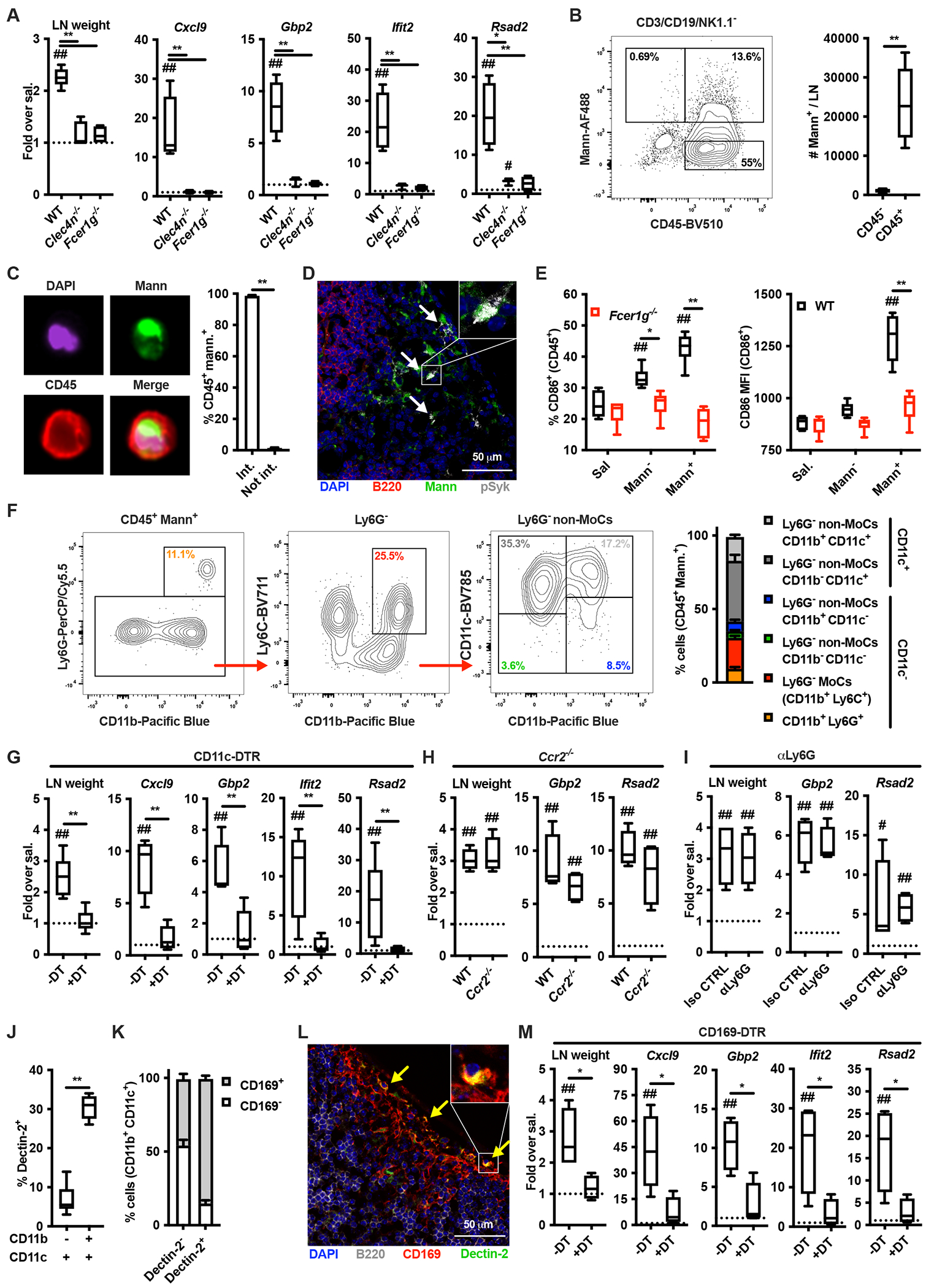

Mannan-elicited LN innate response requires Dectin-2-expressing CD169+ sinus macrophages

We found that Dectin-2, the major receptor for mannans (Borriello et al., 2020; Lionakis et al., 2017; Netea et al., 2008), and its co-receptor FcRγ were required for mannan-elicited LN expansion and ISG induction (Figure 2A). We employed fluorescently labeled mannans and found that mannan-laden cells were CD45+ cells (Figure 2B). Imaging cytometry analysis confirmed that these cells internalized mannans (Figure 2C) and confocal microscopy analysis showed colocalization of phospho-Syk and mannans (Figure 2D), indicative of Dectin-2 and FcRγ-mediated activation. Accordingly, mannan-laden cells showed the highest levels of expression of CD86 in an FcRγ-dependent manner (Figure 2E). We found that more than 50% of mannan-laden cells were Ly6G− (CD11b+ Ly6C+)− CD11c+ cells, while less abundant cell subsets were neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6G+) and monocytes(-derived) cells (MoCs, Ly6G− CD11b+ Ly6C+) (Figure 2F). Depletion of CD11c+ cells, but not inhibition of monocyte egress from the bone marrow or depletion of neutrophils, abolished the mannan-elicited LN innate response (Figure 2G–I). CD11c+ cells can be further distinguished based on the expression of CD11b (Figure 2F). Since Dectin-2 is critical for mannan-elicited LN innate response, we assessed its expression on CD11b− CD11c+ and CD11b+ CD11c+ cells at steady state. Dectin-2 was expressed mainly by CD11b+ CD11c+ cells (Figure 2J). The majority of CD11b+ CD11c+ Dectin-2+ cells expressed the subcapsular and medullary sinus macrophage marker CD169 (Figure 2K). Confocal microscopy analysis confirmed colocalization of CD169 and Dectin-2 on cells lining the LN subcapsular sinus (Figure 2L). Furthermore, DT-mediated depletion of CD169+ cells in CD169-DTR mice phenocopied the results obtained with CD11c-DTR mice and completely abolished mannan-elicited LN expansion and ISG induction (Figure 2M). These results are consistent with a role for CD169+ sinus macrophages as sentinels of lymph-borne materials (Moran et al., 2019).

Figure 2. Mannan-elicited lymph node innate response requires Dectin-2-expressing, CD169+ sinus macrophages.

(A) WT, Clec4n−/− and Fcer1g−/− mice were intradermally injected with saline or mannans. 24 hours later dLNs were collected, their weights were measured, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 3-5 mice per genotype. (B) WT mice were intradermally injected with fluorescently labelled mannans (Mann-AF488). 6 hours later dLNs were collected and the absolute numbers of mannan-laden (Mann+) CD3/CD19/NK1.1− cells were quantified by flow cytometry. N = 6 mice. (C) Mice were treated as in B. Imaging cytometry analysis and quantification of mannan internalization was performed on CD3/CD19/NK1.1-depeted, CD45+ mannan-laden (Mann+) cells. N = 4 mice. (D) WT mice were intradermally injected with fluorescently labelled mannans (Mann). 1 hour later dLNs were collected for confocal microscopy analysis using antibodies against B220 and phospho-Syk (pSyk). DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining. One representative image is shown. (E) WT and Fcer1g−/− mice were injected with saline or fluorescently labelled mannans. 6 hours later dLNs were collected and CD86 expression levels were assessed by flow cytometry on CD3/CD19/NK1.1− CD45+ mannan-laden (Mann+) cells, CD45+ cells that did not capture mannans (Mann−) and CD45+ cells from saline-injected dLNs (Sal). N = 6 mice per genotype. (F) WT mice were intradermally injected with fluorescently labelled mannans. 6 hours later dLNs were collected and the phenotype of CD3/CD19/NK1.1− CD45+ mannan-laden (Mann+) cells was assessed by flow cytometry. N = 6 mice. (G - I) Diphtheria toxin (DT)-treated CD11c-DT receptor (DTR), Ccr2−/− and isotype control (Iso CTRL)- or anti-Ly6G (αLy6G)-treated mice were treated and analyzed as in A. N = 4 mice per group. (J, K) LNs were isolated from untreated WT mice and the expression of Dectin-2 was evaluated by flow cytometry as percentage of expression in the indicated CD3/CD19/NK1.1− CD45+ cell subsets. N = 6 for J or 3 for K. (L) Confocal microscopy analysis of untreated LNs stained with antibodies against Dectin-2, B220 and CD169. DAPI was used for nuclear counterstaining. One representative image is shown. (M) DT-treated CD169-DTR mice were treated and analyzed as in A. N = 4 mice per group. # and ## respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing each group against the value 1 (which represent the contralateral control sample expressed as fold) or saline control. * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing among different experimental groups.

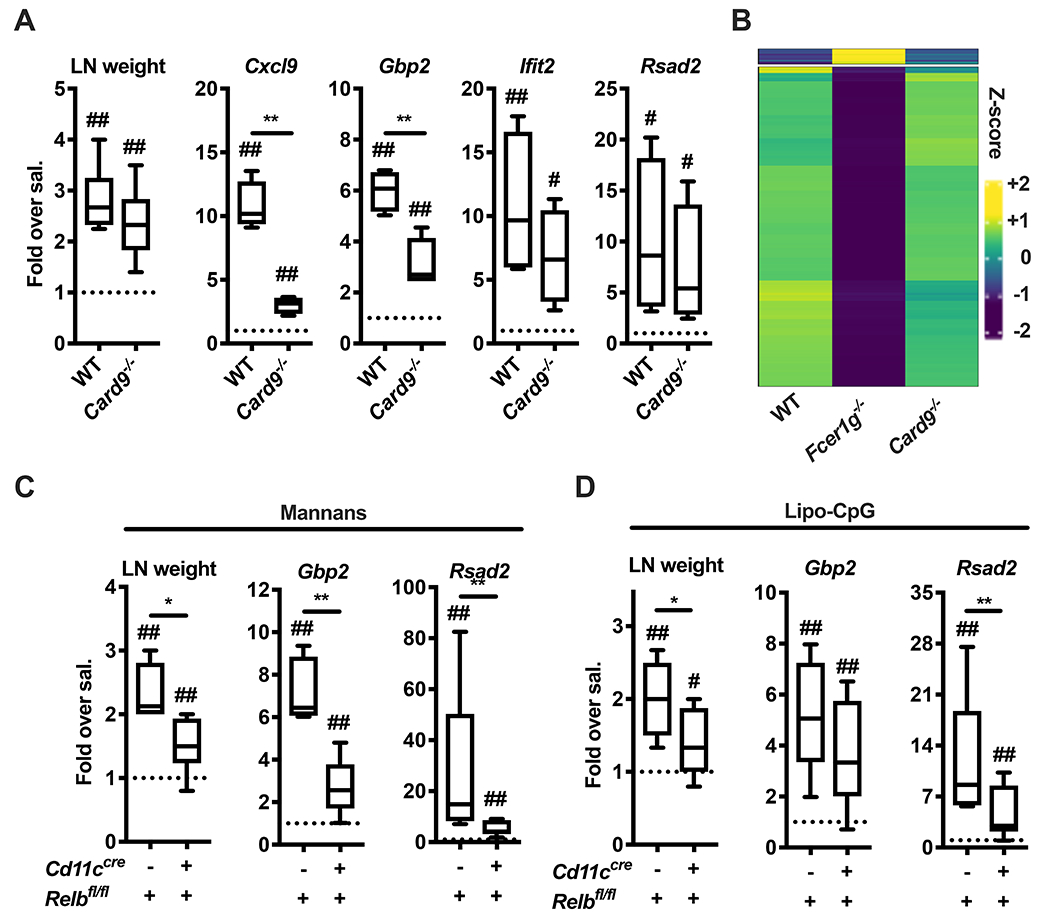

Activation of the non-canonical NF-κB subunit RelB governs mannan-elicited LN innate responses

CARD9 is the major signaling adaptor of Dectins (Brubaker et al., 2015) but mannan-elicited LN expansion was comparable between wild type (WT) and Card9−/− mice (Figure 3A). In keeping with this, induction of ISGs was largely maintained in Card9−/− mice (Figure 3A). In particular, type I IFN-dependent genes were unchanged in Card9−/− compared to WT mice, while type II IFN-dependent ISGs, although significantly decreased compared to WT mice, were still partially induced (Figure 3A). Next, we performed a targeted transcriptomic analysis of mannan-laden CD11b+ CD11c+ cells isolated from WT, Fcer1g−/− and Card9−/− mice. While several genes were differentially expressed between WT (or Card9−/−) and Fcer1g−/− mice, cells isolated from WT and Card9−/− mice exhibited strikingly similar transcriptomes (Figure 3B, Table S3–S7). Pathway enrichment analysis showed that DEGs between cells isolated from WT and Fcer1g−/− are represented in TNF/NF-κB, type I and II IFN pathways (Figure S4). Downstream of Dectin-2, Syk activates the kinase NIK, which in turn leads to CARD9-independent activation of the non-canonical NF-κB transcription factor RelB (Gringhuis et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2018). We therefore generated mice in which RelB is conditionally deleted in the CD11c+ compartment (Cd11ccre Relbfl/fl). Mannan-induced LN expansion and expression of both type I and type II IFN-dependent ISGs were significantly reduced compared to control (Relbfl/fl mice (Figure 3C). Similar results were obtained when Lipo-CpG was employed (Figure 3D). These results support a model in which RelB regulates optimal IFN-dependent ISG expression elicited by LN-targeted stimuli to sustain LN expansion.

Figure 3. Activation of the non-canonical NF-kB subunit RelB governs the mannan-elicited lymph node innate response.

(A) WT and Card9−/− mice were treated and analyzed as in Figure 2A. N = 9 (for LN weight) or 4 (for gene expression analysis) mice per genotype. (B) CD3− CD19− NK1.1− Ter119− CD45+ AF488-mannan+ Ly6G− (CD11b+ Ly6C+)− CD11b+ CD11c+ cells were sorted from dLNs of WT, Fcer1g−/− and Card9−/− mice 6 hours after AF488-mannan injection and transcriptional profiles were assessed by targeted transcriptome sequencing. Results are shown as heatmap of genes with an F-test FDR less than 0.05 and a log2 fold-change (FC) greater than 1 (or lower than −1) between a knockout mouse and WT control. (C, D) Relbfl/fl and Cd11ccre Relbfl/fl mice were treated with saline, mannans or Lipo-CpG, and analyzed as in Figure 2A. N = 4-13 mice per genotype. # and ## respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing each group against the value 1 (which represent the contralateral control sample expressed as fold) or saline control. * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing among different experimental groups. See also Figure S4 and Table S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7.

Molecular pathways required for mannan-elicited LN innate response regulate the magnitude of mannan adjuvant activity

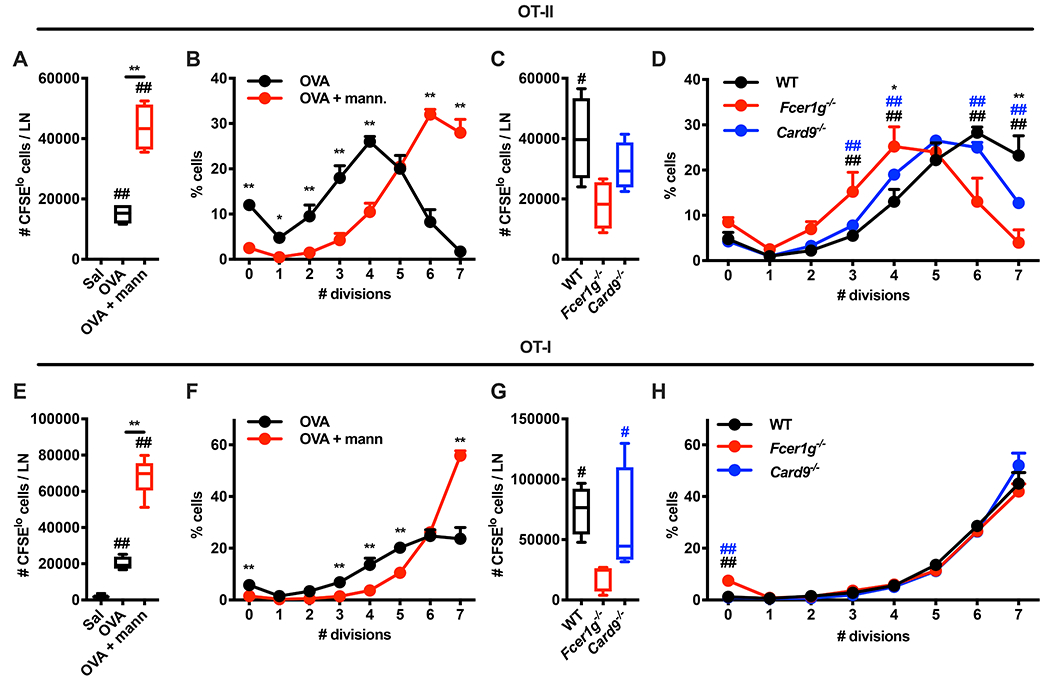

We reasoned that lymphocyte accrual and IFN signatures induced by mannan may favor the encounter of T cells with their cognate antigen and its efficient presentation by the innate immune compartment, thereby improving the adaptive immune response. We employed a model of adoptive transfer of CFSE-labeled, OVA-specific OT-I CD8+ and OT-II CD4+ T cells to assess modulation of T cell proliferation (Figure 4A–H). Combining mannans with OVA resulted in a strong increase in the numbers of OT-I and OT-II cells in the dLN compared to mice injected with saline or OVA alone (Figure 4A, E). This increase was likely due to improved T cell recruitment to the dLN and more efficient antigen presentation/co-stimulation by LN-resident innate immune cells. Indeed, we detected a lower percentage of non-proliferating T cells as well as a higher percentage of T cells undergoing 6 or 7 divisions in mice treated with OVA and mannans compared to OVA alone (Figure 4B, F). Of note, the effect of mannans on T cell proliferation was abrogated in Fcer1g−/− mice, while it was only attenuated in Card9−/− mice (Figure 4C, D, G, H). These results show that pathways required for mannan-elicited LN innate response are also critical for the adjuvant activity of mannans on antigen-specific adaptive immune responses.

Figure 4. Molecular pathways required for mannan-elicited lymph node innate response regulate the magnitude of mannan adjuvant activity.

(A-H) CFSE-labelled OT-I CD8+ T or OT-II CD4+ T cells were injected intravenously in WT mice on day −1. On day 0 the mice were intradermally injected with saline, ovalbumin (OVA), or OVA combined with mannans (OVA + mann). 3 days later dLNs were isolated and the absolute numbers of CFSElo cells (i.e., cells that underwent at least one cycle of cell division) (A, E) or the percentages of cells in each division peak (B, F) were quantified by flow cytometry. N = 4 mice per group. ## indicates p ≤ 0.01 when comparing each group against saline control (A, E). * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01 when comparing OVA vs OVA + mann. (A, B, E, F). (C, D, G, H) WT, Fcer1g−/− and Card9−/− mice were treated and analyzed as in A, B, E, F (with the exception that all mice received OVA combined with mannans). N = 4 mice per genotype. # and ## respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and p ≤ 0.01 when comparing WT vs Fcer1g−/− (black) or Card9−/− vs Fcer1g−/− (blue). * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing WT vs Card9−/−. Results in B, F and D, H are shown as mean + SD.

Mannans formulated with aluminum hydroxide acquire physical properties that predict immunological functions

To further modulate the physical properties of mannans, we exploited the presence of phosphate groups of mannans to promote adsorption onto aluminum hydroxide (hereafter alum), as shown for other molecules (Morefield et al., 2005; Moyer et al., 2020). By 1H-NMR we found that alum adsorbed ~40% of mannans, with the remainder staying soluble (Figure S5A). We also quantified that alum bound mannans at approximately twice its mass in the formulation used in these experiments.

In vitro experiments showed that formulation of mannans with alum, but not alum or mannans alone, induced cytokine production in a Dectin-2- and CARD9-dependent manner (Figure S5B, C), while the expression of costimulatory molecules was Dectin-2-dependent but CARD9-independent (Figure S5D, E). Finally, mannans formulated or not with alum, but not alum alone, induced ISG expression in a Dectin-2-dependent but CARD9-independent manner, except for CXCL1 that was significantly upregulated only in response to mannans formulated with alum in WT cells (Figure S5F–I).

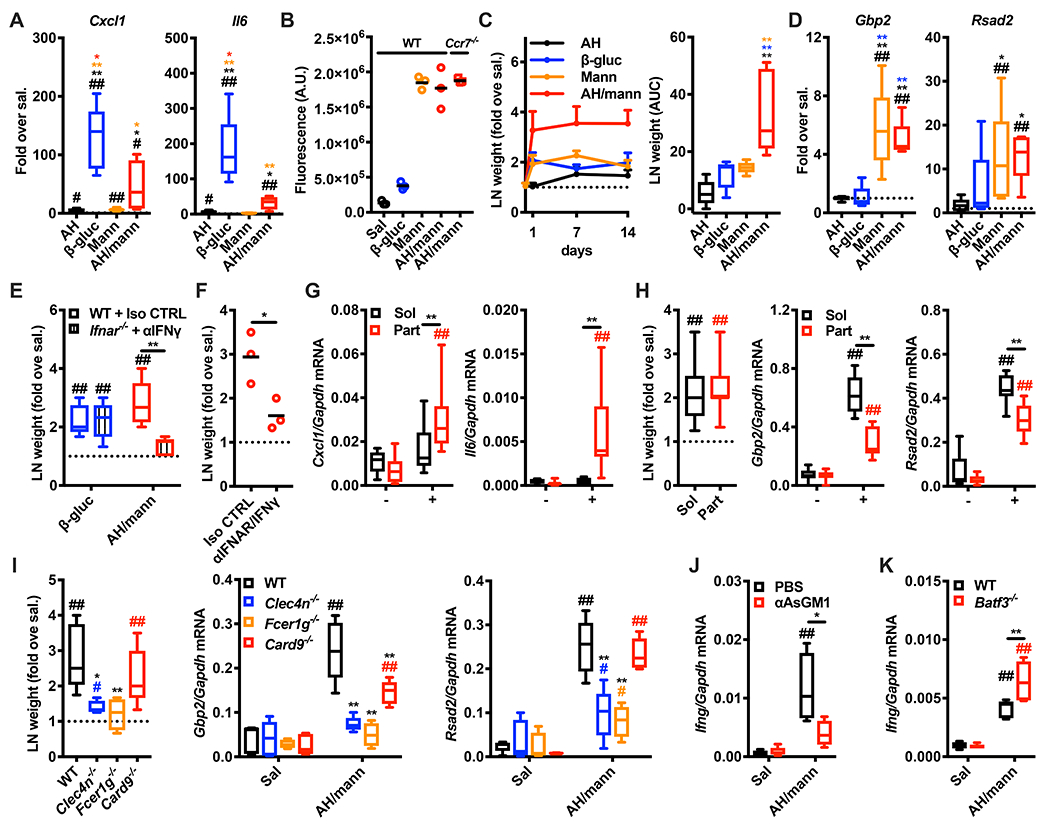

When injected into mice, mannans formulated with alum elicited skin inflammation (Figure 5A), but also drained to the LN in a CCR7-independent manner (Figure 5B). Mannans formulated with alum induced over time a higher LN expansion compared to alum, mannans or β-glucans (Figure 5C). Moreover, mannans alone or in combination with alum elicited comparable ISG expression in the dLN (Figure 5D). As expected, β-glucans induced LN expansion but were largely excluded from the LN and did not induce expression of ISG (Figure 5B–D). LN expansion induced by mannans formulated with alum, but not β-glucans, was impaired in Ifnar−/− mice treated with an anti-IFNγ blocking antibody (Figure 5E). Similar results were obtained when IFN production was transiently blocked by treating WT mice with anti-IFNAR and anti-IFNγ blocking antibodies (Figure 5F). Overall, these results are compatible with a model in which the particulate fraction (mannans adsorbed onto alum) promotes skin inflammation, while the soluble fraction (unbound mannans) drains to the LN and induces the ISG expression. Side by side injections of mice with either particulate or soluble fractions of mannans formulated with alum validated this model (Figure 5G, H). Finally, we assessed whether the LN innate response induced by mannans formulated with alum exploits the same cellular and molecular mechanisms of mannans or if the immunomodulatory functions of alum (Eisenbarth et al., 2008) completely rewired these requirements. We found that LN expansion and ISG induction were impaired in Clec4n−/− and Fcer1g−/− mice (Fig. 5I). In addition, Ifng expression in the dLN was reduced when NK cells were depleted (Fig. 5J) and preserved in Batf3−/− mice lacking cDC1 (Fig. 5K). Overall, formulation with alum endows mannans with enhanced immunological functions that can be predicted based on their physical properties (i.e., particulate vs soluble) and reflect triggering of mannan-dependent Dectin-2-activated pathways.

Figure 5. Formulation of mannans with aluminum hydroxide confers physical properties that predict immunological functions.

(A) Mice were intradermally injected with saline (sal.), alum (AH), β-glucans (β-gluc), mannans (Mann) or AH/mannans (AH/mann). 24 hours later skin samples were collected, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected skin sample. N = 4-5 mice per group. (B) WT mice were intradermally injected with saline (Sal), fluorescently labelled β-glucans (β-gluc), fluorescently labelled mannans (Mann) or their formulation with AH (AH/mann). In addition, Ccr7−/− mice were intradermally injected with AH/mann. 24 hours later dLNs were collected and homogenized to measure total fluorescence. Results are expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.) of fluorescence and shown as individual data points (horizontal bars represent means). N = 3 mice. (C) Mice were treated as in A. 1, 7 and 14 days later dLNs were collected, their weights were measured and expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. Results are represented as mean + SEM (left panel) or area under the curve (AUC, right panel). (D) Mice were treated as in A. 24 hours later dLNs were collected, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 5 per group. (E) Ifnar−/− and WT mice were respectively treated with a blocking anti-IFNγ antibody (αIFNγ) or the same dose of an isotype control (Iso CTRL) on day −1 and 0, and on day 0 mice were intradermally injected with saline (sal.), β-glucans (β-gluc), or AH/mannans (AH/mann). 24 hours later dLNs were collected and their weights were measured. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 5 mice per group. (F), WT mice treated with blocking anti-IFNAR plus anti-IFNγ (αIFNAR/IFNγ) antibodies or the same doses of isotype controls (Iso CTRL) on day −1 and 0, and on day 0 mice were intradermally injected with saline (sal.) or AH/mannans (AH/mann). 24 hours later dLNs were collected and their weights were measured. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected LN. N = 5 mice per group. (G, H) Mice were treated with the soluble (Sol) or particulate (Part) fractions of AH/mannans. 24 hours later skin samples (G) and dLNs (H) were collected, dLN weights were measured and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected skin sample or LN. N = 5 mice per group. (I) Mice of the indicated backgrounds were injected with saline (sal.) or AH/mannans (AH/mann). 24 hours later dLNs were collected, their weights were measured, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are expressed as fold over contralateral, saline-injected sample or as relative expression compared to Gapdh. (J, K) WT mice injected on day −1 and 0 with the same volumes of PBS or a depleting anti-Asialo GM1 antibody (αAsGM1) (J), or WT and Batf3−/− mice (K) were injected intradermally on day 0 with saline (Sal) or AH/mannans (AH/mann). 24 hours later dLNs were collected, and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis. Results are reported as relative expression compared to Gapdh N = 5 mice per group. # and ## respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing each group against its untreated control (CTRL) or the value 1 (which represent the contralateral control sample expressed as fold). * and ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing among different experimental groups. See also Figure S5.

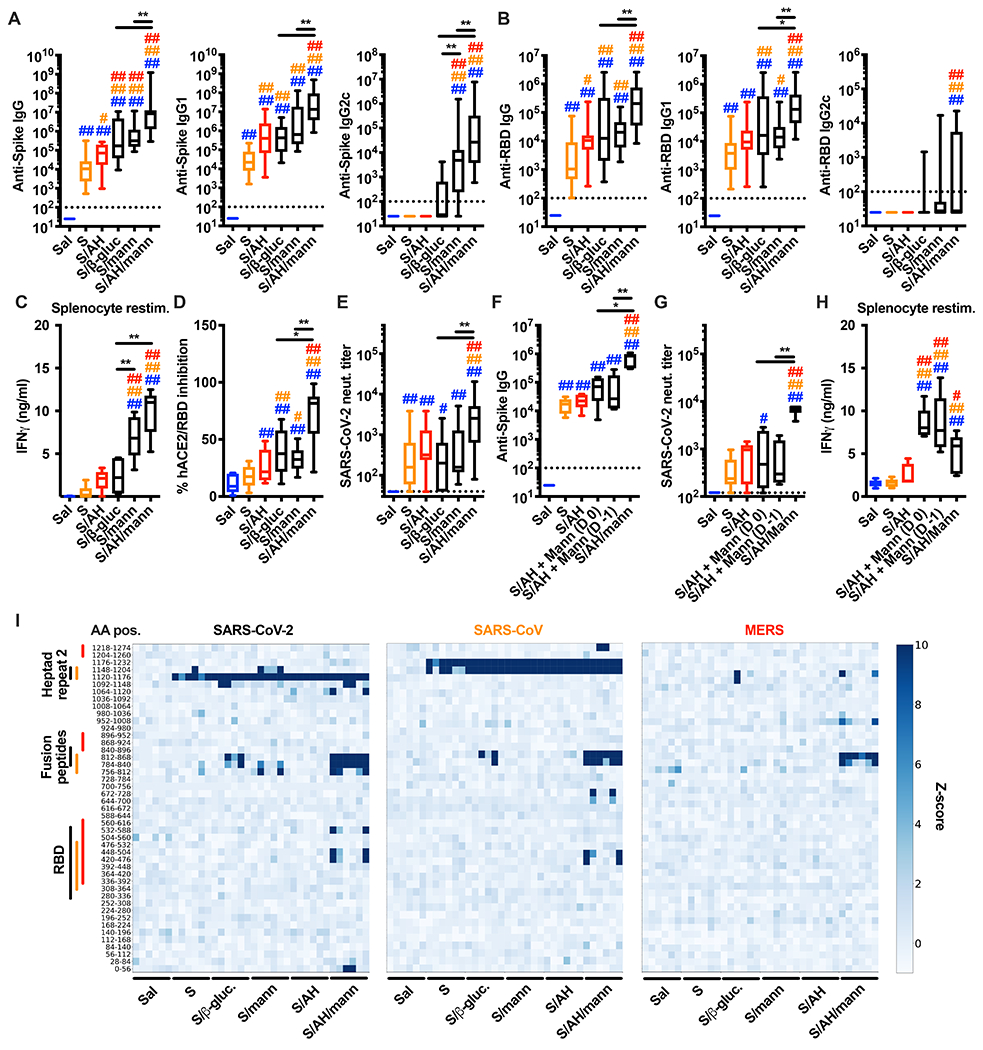

Immunization with SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and mannans formulated with alum generates anti-Spike type 1 immunity and neutralizing antibodies with broad epitope specificity

To investigate adjuvant activities of mannans in an immunization model of translational relevance, we used the pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike trimer (hereafter Spike) (Corbett et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2020; Keech et al., 2020; Mercado et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2020; Walsh et al., 2020; Wrapp et al., 2020). We immunized mice with Spike alone or with Spike admixed with alum, β-glucans, or mannans formulated or not with alum, with a prime - boost schedule. Mannans formulated with alum induced the highest levels of anti-Spike or anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies (Figure 6A, B). Type-1 immunity has been associated with reduced risk of vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease upon viral infection (Graham, 2020), and mannans formulated with alum promoted anti-Spike type-1 immunity by inducing anti-Spike IgG2c and antigen-specific T cells skewed toward IFNγ production (Figure 6A–C). Elevated levels of anti-Spike IgG1 and IgG2c were maintained for up to 98 days post immunization (Figure S6A, B. Next, we performed a surrogate virus neutralization test and an actual SARS-CoV-2 neutralization test and found that mice immunized with Spike and mannans formulated with alum showed the highest degree of neutralization (Figure 6D, E). We also assessed whether there were spatial and temporal constraints to the adjuvant effect of mannans formulated with alum. Mice were injected with Spike and mannans formulated with alum at the same site, or with Spike formulated with alum at one injection site and with mannans at an adjacent site, either on the same day or on consecutive days. An enhanced antibody response was observed only when Spike was admixed with mannans formulated with alum (Fig. 6F, G. In contrast to B cell responses, IFNγ production by antigen-specific T cells was observed in mice immunized with alum and mannans, regardless of when and where mannans were injected (Fig. 6H).

Figure 6. Immunization with SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and mannans formulated with alum generates anti-Spike type 1 immunity and neutralizing antibodies.

(A-E) Mice were injected intradermally with saline (Sal), pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 trimer alone (S) or combined with alum (AH) (S/AH), β-glucans (S/β-gluc.), mannans (S/mann) or AH/mannans (S/AH/mann) on day 0 (prime) and day 14 (boost). Serum samples were collected on day 28 to assess anti-Spike (A) and anti-RBD (B) antibody levels, SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus neutralization test (D) and neutralization titer (E). In selected experiments (C), mice were sacrificed on day 35 to collect spleens and isolate splenocytes for in vitro restimulation with Spike peptides. After 96 hours supernatants were collected and IFNγ protein levels were measured by ELISA. N = 16-18 (A, B), 10 (C), 8-10 (D) or 13-15 (E) mice per group. (F-H) Mice were injected intradermally with saline (Sal), pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 trimer alone (S), or combined with AH (S/AH). Mannans (Mann) were injected separately on the same side of the S/AH injection in a proximal site, either the same day (S/AH + Mann (D 0)) or the day before (S/AH + Mann (D −1)). As a control, SARS-CoV-2 trimer combined with AH and mannans (S/AH/Mann) was also injected. Formulations were injected on day 0 (prime) and day 14 (boost). Serum samples were collected on day 28 to assess anti-Spike antibody levels (F) and SARS-CoV-2 neutralization titer (G). In selected experiments (H), mice were sacrificed on day 35 to collect spleens and isolate splenocytes for in vitro restimulation as in C. N = 6-8 mice per group. #, * and ##, ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01 when comparing among different experimental groups. Comparisons are indicated by the color code. (I) Mice were immunized as in A-E. VirScan analysis was performed on serum samples collected on day 28. Each column represents a single serum sample collected from an individual mouse and each row represents a peptide tile. Tiles are labeled by amino acid start and end position. Color intensity represents the degree of enrichment (z-score) of each peptide. Color-coded lines indicate the approximate aminoacidic positions (AA pos.) of RBD, Fusion peptides and Heptad repeat 2 of each virus. N = 6 mice per group. See also Figure S6.

B and T cell responses induced by mannans formulated with alum were abrogated in Clec4n−/− mice (Fig. S6C, D) but only partially impaired in Card9−/− mice (Fig. S6E, F). Immunization of Cd11ccre Relbfl/fl or Ifnar−/− Ifngr−/− mice, as well as of WT mice in which IFN signaling was transiently abrogated during the immunization phase by administration of anti-IFNAR and anti-IFNγ antibodies, all showed impairment in the anti-Spike IgG response (Fig. S6G–I). Finally, we found that cDC1 were also required, as assessed by impaired IgG production in Batf3−/− mice (Fig. S6J).

To probe the extent of the Spike epitopes targeted by antibodies elicited by the different adjuvant formulations tested above, we performed a VirScan analysis (Shrock et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2015a). All formulations induced antibodies against the Heptad repeat 2 region, but only mannans formulated with alum induced antibodies directed toward the Fusion peptide and RBD (Figure 6I). This epitope targeting profile was comparable for SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV Spike proteins. Notably, although fewer epitopes were recognized, the MERS Spike was also detected by antibodies elicited in mice immunized with SARS-CoV-2 spike and mannans formulated with alum (Figure 6I). Altogether, our results show that mannan formulations enhance anti-Spike antibody levels and promote anti-Spike type 1 immunity, and that mannans formulated with alum are particularly effective at inducing anti-Spike neutralizing antibodies with broad epitope specificity.

The formulation of mannans and alum confers protection against viral infections of the lung.

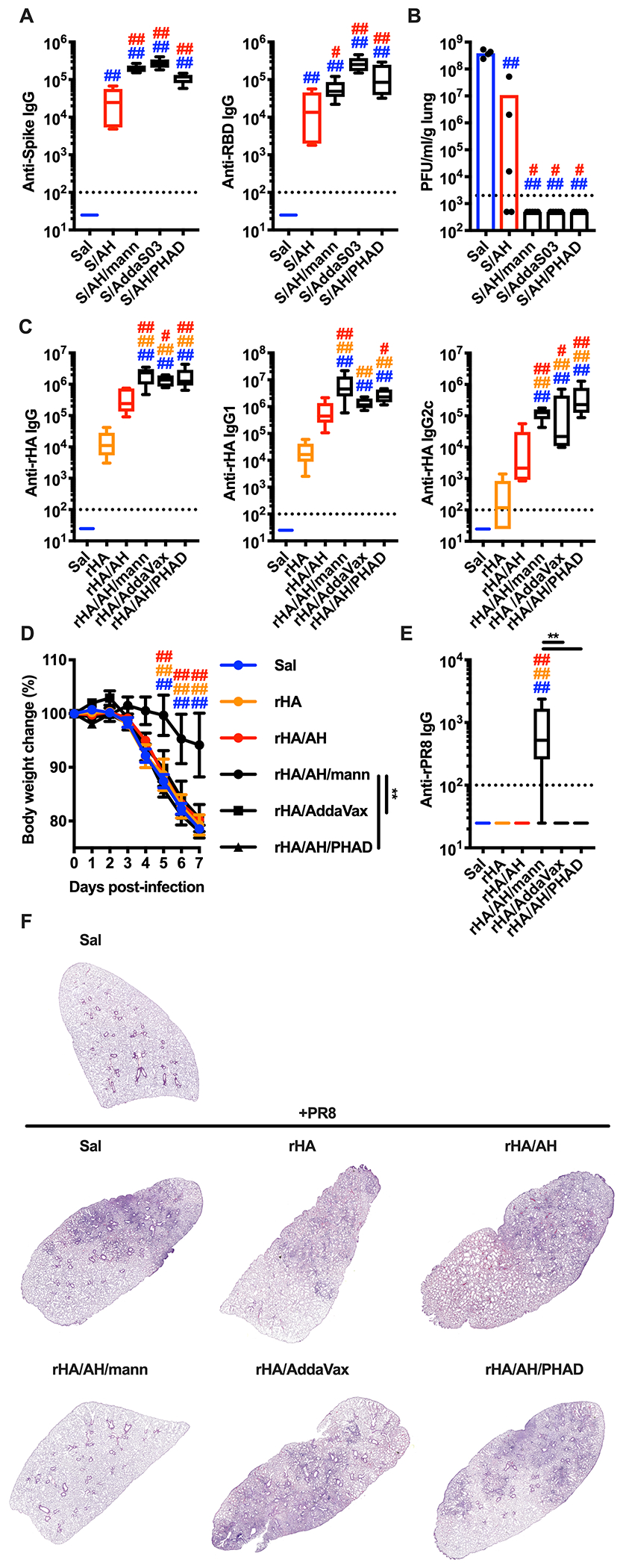

Next, we benchmarked mannans formulated with alum against FDA-approved adjuvants: squalene-based oil-in-water nano-emulsions (AS03-like AddaS03 or MF59-like AddaVax) and the AS04-like formulation prepared by simple admixture of alum and PHAD, a synthetic structural analog of the monophosphoryl lipid A (alum/PHAD).

Immunization of mice with Spike and mannans formulated with alum, AddaS03 or alum/PHAD elicited comparable levels of anti-Spike and anti-RBD IgG antibodies (Figure 7A). Increased anti-Spike and anti-RBD antibodies correlated with increased neutralization capacity compared to alum alone (Figure S7A, B). When mice were infected with the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 MA10 strain (Leist et al., 2020), we found markedly reduced viral lung titers in mice immunized with mannans formulated with alum, AddaS03 or alum/PHAD compared to saline-treated or alum-immunized mice (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. The adjuvant formulation of mannans and alum confers protection against lung viral infections.

(A, B) Mice were injected intradermally with saline (Sal), pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 trimer alone (S) or combined with alum (AH) (S/AH), AH/mannans (S/AH/mann), AddaS03 (S/AddaS03), or AH/PHAD (S/AH/PHAD) on day 0 (prime) and day 14 (boost). Serum samples were collected on day 28 to assess anti-Spike and anti-RBD antibody levels (A). On day 35 mice were intranasally infected with SARS-CoV-2 MA10 on day 35 and 2 days later numbers of plaque forming units (PFU) were quantified in the lungs (B). N = 4-5 mice per group. (C - F) Mice were injected intradermally with saline (Sal), Flublok alone (rHA) or combined with AH (rHA/AH), AH/mannans (rHA/AH/mann), AddaVax (rHA/AddaVax), or AH/PHAD (rHA/AH/PHAD) on day 0 (prime) and day 14 (boost). Serum samples were collected on day 28 to assess antibodies against rHA (anti-rHA, C) or IAV A/PR/8/1934 recombinant hemagglutinin (anti-rPR8, E). On day 35 mice were intranasally infected with IAV A/PR/8/1934 and body weights were recorded for 7 days (D). N = 5 (C, E) or 8 (D) mice per group. On day 7 post-infection mice were sacrificed and lungs were collected for histological analysis (hematoxylin eosin staining, F). One representative image per group is shown. #, * and ##, ** respectively indicate p ≤ 0.05 and 0.01. Comparisons are indicated by the color code. See also Figure S7.

The enhanced magnitude and breadth of the antigen-specific antibody response elicited by mannans formulated with alum might be relevant for additional viral glycoproteins of high antigenic variability, such as influenza A virus (IAV) hemagglutinin (HA). IAV is characterized by many strains within multiple serotypes, generating high subtypic diversity (Sangesland and Lingwood, 2021). We reasoned that the mannan formulation might not only promote a robust antibody response against target antigens but heterosubtypic immunity upon influenza vaccine immunization. We employed the clinically relevant recombinant HA (rHA) vaccine Flublok, and immunized mice with Flublok alone or formulated with alum, mannans formulated with alum, Addavax, or alum/PHAD. Anti-rHA antibodies were significantly increased in mice immunized with rHA and mannans formulated with alum, AddaVax or alum/PHAD (Figure 7C). We then challenged the mice intranasally with the IAV strain A/PR/8/1934, whose HA is not part of the Flublok vaccine, and found that only mice previously immunized with Flublok and mannans formulated with alum were significantly protected. These results correlated with high IgG levels against recombinant HA derived from A/PR/8/1934 (rPR8) in mice immunized with Flublok and mannans formulated with alum, but not the other adjuvant formulations (Figure 7D–F, S7D).

Overall, these data show that the mannans formulated with alum enhances both magnitude and breadth of the antibody response against multiple viral glycoproteins in clinically relevant immunization models.

DISCUSSION

Activation of innate immune cells by PRR ligands is a critical step to initiate an adaptive immune response (Banchereau and Steinman, 1998; Iwasaki and Medzhitov, 2004; Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002; Matzinger, 1994). The study of cellular and molecular events triggered by PRRs led to the identification of signaling organelles, metabolic pathways and gene expression profiles that shape the innate immune response (Brubaker et al., 2015). However, cell-intrinsic features of PRR activation and signaling alone do not explain the complexity of the in vivo inflammatory response elicited by innate stimuli. Indeed, their localization at cellular and organismal levels plays a key role in determining the activation status of innate immune cells (Evavold and Kagan, 2019).

The study of CLRs, and specifically of Dectin-1 and -2, is of particular interest since only the particulate form of their ligands induces efficient receptor clustering and activation (Goodridge et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013). In our study, we show that soluble mannans, while largely inactive in vitro and in vivo at the injection site, traffic to the LN due to their size and elicit a potent innate response, characterized by LN expansion and expression of type I and II IFN transcriptional programs. Remarkably, the responses we observe bypass the need for dendritic cell migration from the periphery to the dLN and soluble mannans directly target CD169+ sinus macrophages. We further modulated the physical properties of mannans by adsorbing them onto alum to obtain formulations in which mannans are present in both soluble and particulate forms. We show that this formulation results in enhanced immunological properties, such as full activation of innate immune cells in vitro and simultaneous targeting of the periphery and the LN. When tested as an adjuvant system formulated with viral glycoprotein antigens (IAV HA or SARS-CoV-2 Spike), mannans enabled induction of neutralizing antibodies with broad epitope specificity. Mannans formulated with alum protects against a SARS-CoV-2 MA10 challenge to the same extent as adjuvants that resemble those included in licensed vaccines. Immunization of mice with rHA-based Flublok vaccine, formulated with alum and mannans, elicited heterosubtypic immunity. Overall, our work sheds light on the molecular pathways activated by mannan formulations that trigger LN innate and adaptive responses and result in antibody responses against viral glycoproteins of enhanced magnitude and breadth.

A key aspect of our work is the requirement for both type I and II IFNs to sustain mannan-induced lymphocyte accrual and LN expansion. Also, IFNs are necessary to potentiate the induction of anti-glycoprotein antibodies. IFNs act on both myeloid cells and LN stromal cells where they modulate a range of functions, including chemokine expression and vascular permeability (Barrat et al., 2019; Ivashkiv, 2018). Hence, our results raise the possibility that mannan-elicited IFN signatures affect LN-resident myeloid and stromal compartments, eventually leading to potentiated adaptive immune responses. Our data on the augmented production and epitope specificity of anti-Spike antibody and data on the induction of heterosubtypic anti-A/PR/8/1934 HA-antibody suggest that the IFN signature driven by mannans formulated with alum broadens epitope recognition and potentiates protection against viruses. Nevertheless, it will be important in the future to assess a possible ‘innate training’ effect promoted by a more potent IFN response that may yield to cross-protective innate immunity.

Mannans formulated with alum acquire remarkable new immunological properties. Although we cannot exclude synergy between AH and mannans, our results are more readily explained by the concurrent presence in the formulation of mannans and alum of unbound and alum-adsorbed mannans. The former is responsible for ISG expression in the dLN, while the latter mediates skin inflammation. Evaluation of mannans formulated with alum in our immunization model with SARS-CoV-2 Spike supports this model. Direct synergy between alum and mannan inflammatory activity was excluded when alum and mannans were injected separately but in close physical proximity, an approach that led to a loss of the capacity of these adjuvants to enhance anti-Spike IgG. Such loss did not apply to T cell-mediated responses, which were boosted by the presence of mannans, independently of their coformulation with alum. Analysis of soluble mannans formulated or not with alum and admixed to Spike also showed that both formulations induce humoral and cellular type 1 immunity. Early induction of type I and II IFN signatures in the dLN is therefore sufficient to explain polarization of the adaptive immune response. Transient disruption of type I/II IFN signaling by administration of blocking antibodies significantly decreased levels of anti-Spike IgG, suggesting that early IFN signatures in the dLN translate into long-term potentiation of the immune response.

A remarkable property of the formulation of mannans and alum is its ability to induce neutralizing anti-Spike antibodies with broad epitope specificity. These antibodies cross-react with SARS-CoV Spike and, to a lesser extent, with MERS Spike. The epitope specificity profile observed in mice immunized with alum and mannans is comparable to that observed in COVID-19 patients, highlighting the translational relevance of our results (Shrock et al., 2020). Production of these antibodies has the same molecular and cellular requirements as the LN innate reaction induced by mannans formulated with alum, with the sole exception of cDC1 that play important roles in driving the IgG response, but not the LN innate response. Neutralizing antibodies are important for protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in animal models (Cao et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2020; Lv et al., 2020; McMahan et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2020; Schafer et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2020; Tortorici et al., 2020; Zost et al., 2020). Accordingly, mice immunized with Spike and mannans formulated with alum show undetectable lung viral titers after infection with SARS-CoV-2 MA10, similar to mice immunized with clinically relevant adjuvant formulations. We then employed a model of influenza vaccination, using the clinically relevant Flublok vaccine. While all adjuvants tested enhanced the antibody response to Flublok, only mannans formulated with alum induced heterosubtypic immunity, that was paralleled by detection of antibodies against HA of A/PR/8/1934. It will be important in the future to clarify how the formulation of mannans and alum modulates germinal center dynamics and B cell repertoire selection. From a translational perspective, the broadening of epitope specificity suggests that mannans formulated with alum in combination with appropriate antigens might be a promising candidate for the development of vaccines that target multiple coronavirus or influenza A strains.

Overall, our study provides mechanistic and translational insights into how modulation of the physical form of mannans enables Dectin-2 targeting to enhance vaccine immunogenicity and protection, thereby illuminating the relationship between the physical form of innate stimuli and LN innate and adaptive immune responses.

Limitations of the study:

Our study provides a detailed mechanistic analysis of mannan-induced LN innate response at the molecular and cellular level. We demonstrated that mannans alone, or admixed with alum, require Dectin-2-expressing, CD169+ sinus macrophages, but not cDC1, neutrophils or monocytes for LN expansion, while cDC1 are required to potentiate antibody production. It remains to be elucidated whether other immune cells, such as cDC2, may be involved either in the LN innate or adaptive response. Also, it will be important to unravel the possible relationship between NK cells and DCs. Another unexpected finding is the only partial requirement of CARD9, the key signaling adaptor downstream of Dectins (Borriello et al., 2020; Brubaker et al., 2015). CARD9-independent pathways downstream of Dectins have also been described, including NIK-dependent activation of the non-canonical NFκB subunits p52 and RelB (Gringhuis et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2018). Mice that lack NIK, p52 or RelB have profound defects in secondary lymphoid organ development (Sun, 2017). Our results show that RelB activation in CD11c-expressing cells regulates mannan-induced LN expansion and expression of type I ISGs and cooperates with CARD9 in modulating the expression of type II ISGs. Although the role of RelB in modulating IFN responses and ISG expression is ambiguous (Le Bon et al., 2006; Saha et al., 2020). and more studies will be required to decipher its role upon mannan encounter, our findings create an intriguing parallelism between LN development and the innate response, setting the stage for RelB as a central regulator of the biology of secondary lymphoid organs.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Ivan Zanoni (ivan.zanoni@childrens.harvard.edu; @Lo_Zanzi)

Materials Availability

All experimental models and reagents will be made available upon installment of a material transfer agreement.

Data and Code Availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

RNA sequencing data accession number: GSE193419.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice:

C57BL/6J (Jax 00664) (wild type), CB6F1 (Jax 100007), B6.129P2(C)-Ccr7tm1Rfor/J (Ccr7−/−, Jax 006621), B6.129S2-Ifnar1tm1Agt/Mmjax (Ifnar−/−, Jax 32045-JAX), B6.Cg-Ifngr1tm1Agt Ifnar1tm1.2Ees/J (Ifnar−/− Ifngr−/−, Jax 029098), B6.FVB-1700016L21RikTg(Itgax-DTR/EGFP)57Lan/J (CD11c-DTR, Jax 004509), B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-cre)1-1Reiz/J (Cd11ccre, Jax 008068), B6.Cg-Relbtm1Ukl/J (Relbfl/fl, Jax 028719), B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1Ifc/J (Ccr2−/−, Jax 004999), B6.129S(C)-Batf3tm1Kmm/J (Batf3−/−, Jax 013755), B6.129-Card9tm1Xlin/J (Card9−/−, Jax 028652), B6.129S6-Clec7atm1Gdb/J (Clec7a−/−, Jax 012337) and C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I, Jax 003831) were purchased from Jackson Labs. B6.129P2-Fcer1gtm1Rav N12 (Fcer1g−/−, Model 583) were purchased from Taconic. Clec4n−/− mice were kindly provided by Drs. Nora A. Barrett and Yoichiro Iwakura. B6;129-Siglec1<tm1(HBEGF)Mtka> (CD169-DTR) mice were kindly provided by Dr. F. Pucci and are from the Riken Institute (No. RBRC04395), deposited by Drs. Kenji Kohno and Masato Tanaka (Miyake et al., 2007; Saito et al., 2001). B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J (OT-II, Jax 004194) were kindly provided by Juan Manuel Leyva-Castillo. 6-8 week-old female mice were used for all the experiments. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions at Boston Children’s Hospital, and all the procedures were approved under the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and operated under the supervision of the department of Animal Resources at Children’s Hospital (ARCH).

Cell lines:

VeroE6 cells (ATCC, CRL-1586) were cultured in DMEM (Quality Biological, 112-014-101) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen/strep. Expi293 cells were grown in Expi293 Expression Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cells were maintained at 37°C (5% CO2) and passaged when confluent.

Viruses:

Influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1) (NR-348) was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH, and propagated in the allantoic cavity of 9-11 days old specific-pathogen-free chicken (SPF) eggs (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Samples of SARS-CoV-2 were obtained from the CDC following isolation from a patient in Washington State (WA-1 strain - BEI #NR-52281). SARS-CoV-2 MA10 was generated in mice infected with the SARS-CoV-2 MA stock virus for the first passage and with lung homogenates of the previous passage for all following passages (passage 2 – 10). Clonal isolate from P10 was plaque purified to obtain SARS-CoV-2 MA10. All virus stocks were propagated on Vero E6 cells.

Yeasts:

Candida albicans strain SC5314 was maintained on blood agar (Remel) plates grown at 37°C.

METHOD DETAILS

Reagents and antibodies:

for flow cytometry, imaging cytometry, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and confocal microscopy experiments the following reagents and antibodies were used: anti-CD45 BV510 (30-F11), anti-CD45 Alexa Fluor 700 (30-F11), anti-CD45 APC (30-F11), anti-CD45 PerCP/Cy5.5 (30-F11), anti-CD3 PE/Dazzle 594 (17A2), anti-CD3 BV510 (17A2), anti-TCRβ Alexa Fluor 400 (H57-597), anti-CD4 PE/Cy5 (GK1.5), anti-CD19 PE/Dazzle 594 (6D5), anti-CD19 BV650 (6D5), anti-NK1.1 PE/Dazzle 594 (PK136), anti-NK1.1 BV421 (PK136), anti-CD49b Alexa Fluor 488 (DX5), anti-Ter119 PE/Dazzle 594 (TER-119), anti-I-A/I-E PE/Cy7 (M5/114.15.2), anti-Ly6G PerCP/Cy5.5 (1A8), anti-CD11b Pacific Blue (M1/70), anti-Ly6C BV711 (HK1.4), anti-CD11c BV785 (N418), anti-CD11c APC (N418), anti-CD86 APC/Cy7 (GL-1), anti-CD86 APC (GL-1), anti-OX40L PE (RM134L), anti-CD169 APC (3D6.112), anti-CD169 Alexa Fluor 647 (3D6.112), anti-CD4 APC/Fire 750 (GK1.5), anti-CD8 PE/Cy7 (53-6.7), anti-CD45R/B220 Alexa Fluor 594 (RA3-6B2), anti-IFNγ PE (XMG1.2), anti-CD3 Biotin (145-2C11), anti-CD19 Biotin (6D5), anti-NK1.1 Biotin (PK136), anti-Ter119 Biotin (TER-119), TrueStain FcX (93), True-Stain Monocyte Blocker and Zombie Red Fixable Viability Kit were purchased from BioLegend; anti-Dectin-2 PE (REA1001) was purchased from Miltenyi Biotec; rat anti-Dectin-2 (D2.11E4) was purchased from GeneTex; anti-phopsho-Syk (Tyr525/526) (C87C1) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology; CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit, Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester (Succinimidyl Ester) and DAPI were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

For in vitro and in vivo experiments the following reagents were used: Iscove’s Modified Dubecco’s Medium (IMDM), Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS), penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep) and L-Glutamine (L-Gln) were purchased from Lonza; Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific; collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum, deoxyribonuclease (DNase) I from bovine pancreas and dispase II were purchased from MilliporeSigma; TLRGrade Escherichia coli LPS (Serotype O555: B5, 1 μg/ml) was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences; curdlan (10 μg/ml) was purchased from Wako Chemicals; mannans, β-glucans and their Alexa Fluor 488-conjugates (10 μg/ml for in vitro experiments, 500 μg/mouse for in vivo experiments) were provided by Michael D Kruppa, Zuchao Ma and David L Williams (East Tennessee State University); carboxyl latex beads 3 μm were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and used directly (cell:bead ratio 1:10 for in vitro experiments) or after coating with diaminopropane derivatized mannans provided by Michael D Kruppa, Zuchao Ma and David L Wiliams (East Tennessee State University); WGP-S and WGP-D (500 μg/mouse for in vivo experiments) were purchased from InvivoGen; Lipo-CpG was provided by Darrell J. Irvine (Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT); diphtheria toxin (unnicked) from Corynebacterium diphtheriae (200 ng/mouse for CD11-DTR mice, 500 ng/mouse for CD169-DTR mice) was purchased form Cayman Chemical; ovalbumin (OVA) EndoFit (5 μg/mouse), Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (AH, 2 μg/ml for in vitro experiments, 100 μg/mouse for in vivo experiments), AddaVax (25 μl/mouse) and AddaS03 (25 μl/mouse) were purchased from InvivoGen; PHAD (synthetic monophosphoryl lipid A, 50 μg/mouse) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids; recombinant pre-fusion stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike trimer (1 μg/mouse) and RBD were expressed and purified from plasmids generously provided by Drs. Berney S. Graham (NIH Vaccine Research Center) and Aaron G. Schmidt (Ragon Institute), respectively; SARS-CoV-2 Spike peptide pools (PepTivator SARS-CoV-2 Prot_S) were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec; Flublok vaccine (quadrivalent formula 2020 – 2021, composed of HAs from IAV A/Guangdong-Maonan/SWL1536/2019 [H1N1], IAV A/HongKong/2671/2019 [H3N2], influenza B virus B/Washington/02/2019 and influenza B virus B/Phuket/3073/2013) was purchased from the Boston Children’s Hospital Pharmacy; Influenza A H1N1 (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934) recombinant hemagglutinin (rPR8) was purchased from Sino Biological; anti-Asialo-GM1 (Poly21460, 25 μl/mouse) was purchased from BioLegend; anti-CD62L (Mel-14, 100 μg/mouse), anti-IFNAR1 (MAR1-5A3, 500 μg/mouse), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2, 200 μg/mouse), anti-Ly6G (1A8, 50 μg/mouse) and their isotype controls rat IgG2a (2A3), rat IgG1 (HRPN) and mouse IgG1 (MOPC-21) were purchased from Bio X Cell.

The formulation of alum and mannans (AH/mann) was obtained by admixture of alum (100 μg/10 μl), mannans (500 μg/25 μl) and saline (15 μl). When formulated with an antigen (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 Spike trimer or Flublok) the volume of saline was reduced accordingly in order to keep the total volume constant. This formulation is further described in the NIH/NIAID Vaccine Adjuvant Compendium (https://vac.niaid.nih.gov).

Isolation of mannan from C. albicans.

For mannan isolation, C. albicans was inoculated into 15 l of YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose) and grown for 20 hours at 37°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 minutes. This resulted in a 100 g pellet from 15 l of media. We used a standard protocol for isolation and NMR characterization of the mannan (Kruppa et al., 2011; Lowman et al., 2011). In brief, the cell pellets were suspended in 200 ml of acetone to delipidate the cells for 20 minutes prior to centrifugation at 5000 g for 5 minutes, removal of acetone and drying of the pellet for an hour. Dried pellets were broken up and transferred to a tissue homogenizer. An equivalent volume of acid-washed glass beads was added and 200 ml of dH2O was added to the mixture. The cells were subjected to bead beating for three 30 second pulses before the entire mixture was transferred to a 1 l flask. The material was autoclaved for 2 hours, allowed to cool and then centrifuged for 5 minutes at 5000 g. The supernatant was retained and the cell pellet discarded. Pronase (500 mg in 20 ml dH2O), which had been filter sterilized and heat treated for 20 minutes at 65°C (to remove any glycosidic activity) was added to the supernatant along with sodium azide to a concentration of 1 mM. The mixture was then incubated overnight (20 hours) at 37°C to allow for degradation of any proteins in the solution. Mannans were extracted by addition of an equal volume of Fehling’s solution to the protease treated mannan solution and allowed to mix for one hour at room temperature. After mixing the solution was allowed to stand for 20 minutes to facilitate mannan precipitation. The supernatant was decanted and the precipitate was dissolved in 10 ml of 3M HCl, to enable release of copper from the reducing ends of the mannans. To the dissolved mannan solution 500 ml of an 8:1 mixture of methanol:acetic acid was added, and the mixture stirred to allow the mannan to precipitate overnight. After the material had settled, the supernatant was decanted, washed again with 500 ml of methanol, allowing six hours for the mannans to settle. The supernatant was decanted and the remaining precipitate was dissolved in 200 ml dH2O. The mannans were dialyzed against a 200-fold change of dH2O over 48 hours using a 2000 MW cutoff membrane to remove residual acid, methanol and other compounds from the extraction process. The dialysate was then subjected to lyophilization and stored at −20°C until needed. A small sample (10 mg) of the material was subjected to NMR to confirm for the purity of the N-linked mannans (Lowman et al., 2011) and for assessment of molecular weight (Kruppa et al., 2011). Prior to in vitro or in vivo use the mannan is depyrogenated to remove any residual endotoxin and filter sterilized.

Preparation of the diaminopropane (DAP) derivatized mannan.

Mannan (100 mg) was dissolved in 6 ml of water, followed by addition of 1,3-diaminopropane (0.6 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 1 hour. Sodium cyanoborohydride (300 mg) was added and the pH value of the reaction mixture was adjusted to ~4.8 by slowly adding acetic acid (~1.1 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 hours, then dialyzed with a 2000 MWCO RC membrane against ultrapure water (1000 ml x 4). The retentate was harvested and lyophilized to yield the DAP attached mannan. The recovery was 88.5 mg, ~88%. The mannan-DAP was characterized by 1H-NMR to confirm the identity of the compound.

For conjugation with Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester (Succinimidyl Ester), ~15 mg of mannan-DAP were resuspended in 1 ml of sodium borate conjugation buffer (100 mM, pH 8.5) and allowed to solvate for at least 24 hours. Then, 1 mg of Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester resuspended in 35 μl of DMSO was added to the solution and incubated overnight in the dark at room temperature with gentle agitation. The reaction mixture was dialyzed with a 6000-8000 MWCO RC membrane against saline (1000 ml x 4) and the retentate was filter sterilized.

For conjugation with carboxyl latex beads 3 μm, mannan-DAP was resuspended at a concentration of 10 mg/1 ml of BupH MES conjugation buffer pH 4.5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and allowed to solvate for at least 24 hours. 1 ml of mannan-DAP was added to 50 x 106 beads and then mixed with 4 mg/1 ml of EDC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) resuspended in pure water. The reaction mixture was incubated for 4 hours in the dark at room temperature with gentle agitation. Then, the beads were washed twice (4000 g for 10 minutes) with saline and resuspended in saline at a concentration of 108 beads/ml.

Preparation of Candida albicans β-glucan particles.

β-glucan particles were isolated from Candida albicans SC5314 as previously described by our laboratory (Lowman et al., 2014). Briefly, glucan was isolated from C.albicans using a base/acid extraction approach with provides water insoluble glucan particles that are > 95% pure. The structure and purity of the glucan was determined by 1H-NMR in DMSO-d6 (Lowman et al., 2014). Prior to in vitro or in vivo use the β-glucan particles are depyrogenated and sterilized.

Preparation of the diaminopropane (DAP) derivatized β-glucan.

β-glucan particles (20 mg) were dissolved in 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in 4 ml vial after one hour of stirring. 1,3-Diaminopropane (100 μL) was added and stirred at ambient temperature for 3 hours. Sodium cyanoborohydride (100 mg) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 48 hours, followed by addition of sodium borohydride (50 mg) and stirring for 24 hours. Acetic acid (200 μl) was added dropwise at 0°C to quench the reaction and the reaction mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 3 hours. The β-glucan particles were harvested and washed five times in water by centrifugation (862 g). The recovery was >95%. The glucan-DAP was characterized by 1H-NMR to confirm the derivatized glucan was still intact. The glucan-DAP was lyophilized to dryness and stored at −20°C in the dark in a desiccator until needed.

For conjugation with Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester (Succinimidyl Ester), 20 mg of glucan-DAP were suspended in 1 ml of sodium borate conjugation buffer (100 mM, pH 8.5) and allowed to hydrate for at least 24 hours at 4°C. 1 mg of Alexa Fluor 488 NHS Ester resuspended in 35 μl of DMSO was then added to the solution which was incubated overnight in the dark at room temperature with gentle agitation. The reaction mixture was centrifuged, washed five times in water with centrifugation (862 g) and the 488 labeled glucan particles were harvested.

Quantification of mannans in the alum/mannans formulation.

Supernatants were harvested from the alum/mannans mixture and were lyophilized. Lyophilized supernatants and a standard mannan sample (4.0 mg) that was not mixed with AH were respectively dissolved in 500 μl of deuterium oxide (99.9% D) with 0.01% (W/V) internal standard TMSP-2,2,3,3-D4 (98.0% D). 1H-NMR data were collected on a 400MHz Bruker Avance Ultra Shield NMR spectrometer at 295 K with the same acquisition parameters for all the samples. NMR spectra were processed using TOPSPIN 2.1 running on the Avance 400MHz NMR. The ring proton resonances (3.25 - 4.50 ppm) were integrated referencing to the integral of internal standard (−0.02 - 0.02 ppm) calibrated as 1.0. Based on the ratio between the mass of standard mannan (4.0 mg) and its ring proton integral (39.12), the mass of mannan in the supernatant was calculated using the detected ring proton integral multiplied by 4.0/39.2. Thus, the amount of mannan absorbed by the AH was determined by difference between the mass of total mannan added and the mass of mannan remaining in the supernatant after formulation.

Analysis of skin and LN responses.

To assess skin and LN innate responses, mice were injected intradermally on day 0 with the indicated compounds in a volume of 50 μl on each side of the back (one side for the compound and the contralateral side for saline of vehicle control). 6 or 24 hours post-injection skin samples at the injection sites and draining (brachial) LNs were collected for subsequent analysis. In selected experiment LNs were also collected 7 and 14 days post-injection.

Skin samples were transferred to a tissue homogenizer and disrupted with beads in 1 ml of TRI Reagent (Zymo Research). Then, samples were centrifuged 12000 g for 10 minutes and 800 μl of cleared supernatant were transferred to a new tube for subsequent RNA isolation.

LNs were weighted on an analytical scale prior to transfer to a tissue homogenizer and disrupted with beads in TRI Reagent as indicated for skin samples or processed to generate a LN cell suspension by modification of a previously published protocol (Fletcher et al., 2011). Briefly, individual LNs were incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes in 400 μl of digestion mix (IMDM + pen/strep + FBS 2% + collagenase 100 mg/ml + dispase II 100 mg/ml + DNase 10 mg/ml). Then, LNs were ground by pipetting with a 1000 μl tip, supernatants were transferred to new tubes and kept at 4°C while 200 μl of digestion mix were added to the pellets and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. This cycle was repeated one more time, then pooled supernatants of individual LNs were divided into two aliquots: one for flow cytometry analysis, another one was centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes and the cell pellet was resuspended in 800 μl of TRI Reagent for subsequent RNA isolation. In selected experiment LN suspensions were cultured in the presence of Brefeldin A (BioLegend) for 4 hours and then processed for flow cytometry analysis (both surface staining and intracellular cytokine staining).

For specific experiments mice were treated with: anti-CD62L blocking antibody or isotype control, intravenous injections on day −1; anti-IFNγ and anti-IFNAR1 blocking antibody or isotype controls, intravenous injections on day −1 and 0; anti-Asialo-GM1 or PBS, intravenous injections on day −1 and 0; anti-Ly6G depleting antibody or isotype control, intraperitoneal injections on day −1 and 0; diphtheria toxin, intravenous injections on day −1 and intradermal injections (co-injected with mannans) on day 0 for CD11c-DTR mice, intraperitoneal injection on day −2 for CD169-DTR mice.

In vitro stimulation of GM-CSF-differentiated, bone marrow-derived phagocytes.

Bone marrow-derived phagocytes were differentiated from murine bone marrow in IMDM + 10% B16-GM-CSF derived supernatant + 10% FBS + pen/strep + L-Gln and used after 7 days of culture. Then, cells were harvested, plated in flat bottom 96 well plates at a density of 105 cells/200 μl/well in IMDM + 10% FBS + pen/strep + L-Gln and stimulated with the indicated compounds for 18-21 hours. At the end of stimulation, supernatants were harvested, and TNF and IL-2 concentrations were measured by ELISA (BioLegend) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were detached with PBS + EDTA 2 mM and transferred to a round bottom 96 well plate for subsequent flow cytometry staining and analysis. Alternatively, cells were stimulated for 6 hours, lysed in TRI Reagent and RNA was extracted for gene expression analysis.

In vivo quantification of fluorescently labelled β-glucans and mannans.

Mice were intradermally injected with 500 μg/mouse of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated β-glucans and mannans (in selected experiments mannans were formulated with 100 μg/mouse of AH before injection). At the indicated timepoints dLNs were collected, transferred to a tissue homogenizer and disrupted with beads in 400 μl of deionized water. Then, samples were centrifuged (12000 g for 10 minutes) and cleared supernatants were transferred to a 96 well clear bottom black plate. Fluorescence values were measured with SpectraMax i3x microplate reader (Molecular Devices) and expressed as arbitrary units after background (deionized water) subtraction.

Flow cytometry, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), imaging cytometry and confocal microscopy.

For flow cytometry analysis, cells were first stained with Zombie Red Fixable Viability in PBS for 5 minutes at 4°C, washed once with PBS + BSA 0.2% + NaN3 0.05% (300 g for 5 minutes) and then stained with antibodies against surface antigens diluted in PBS + BSA 0.2% + NaN3 0.05% for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed again and resuspended in PBS + BSA 0.2% + NaN3 0.05%. Samples were acquired on a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer and data were analyzed using FlowJo v.10 software (BD Biosciences). CountBright Absolute Counting Beads were used to quantify absolute cell numbers. In selected experiments, after fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde cells were permeabilized by incubation with a saponin-based permeabilization buffer (BioLegend) for 10 minutes at 4°C and stained with antibodies against intracellular cytokines diluted in permeabilization buffer for 20 minutes at 4°C. Then, cells were washed with permeabilization buffer, resuspended in PBS + BSA 0.2% + NaN3 0.05% and acquired as indicated before.

For FACS and imaging cytometry, mice were intradermally injected with AF488-mannans and 6 hours later dLNs were harvested to obtain LN cell suspensions. For FACS, cells were stained with antibodies against surface antigens diluted in PBS + BSA 0.2% for 20 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then washed once, resuspended in 1 ml of PBS + BSA 0.2%, filtered through 70 μm cell strainers (Fisher Scientific) and sorted with a Sony MA900 cell sorter directly into 1 ml of TRI Reagent. The following cell subset was sorted: CD3− CD19− NK1.1− Ter119− CD45+ AF488-mannan+ Ly6G− (CD11b+ Ly6C+)− CD11b+ CD11c+. For imaging cytometry, cells were depleted of lymphoid and erythroid cells by sequential staining with biotinylated antibodies against anti-CD3, anti-CD19, anti-NK1.1, anti-Ter119 and Streptavidin Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The remaining cells were stained with anti-CD45 APC, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, washed once and resuspended in 60 μl of PBS + DAPI (0.2 μg/ml). Samples were then acquired on an Amnis ImageStream X Mark II (Luminex Corporation). Mannan internalization was analyzed with Amnis Ideas Software and calculated with Internalization Feature as AF488 signal within the APC mask.

For confocal microscopy, dLNs were isolated at steady state or 1 hour post-injection of AF488-mannans and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Tissue slides were prepared from frozen LN samples at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Histology Core Facility and stained at the BIDMC Confocal Imaging Core Facility. Briefly, frozen sections were air-dried for 30 minutes and rehydrated. The sections were permeabilized using 0.05% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes at room temperature and washed three times with TBS. The sections were then incubated with 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab) for 1 hour at room temperature. For Dectin-2 staining of steady state LNs, slides were incubated with rat anti-Dectin-2 overnight at 4°C. The slides were washed three times and incubated with: Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated Donkey anti-rat secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab) for 90 minutes at room temperature and washed four times. Slides were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated rat anti-CD169 primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated rat anti-CD45R/B220 primary antibody for 90 minutes at room temperature and then washed with TBS. For phospho-Syk staining of AF488-mannan-treated LNs, slides were incubated with rabbit anti-phospho-Syk (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. The slides were washed three times and incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated Donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Lab) for 90 minutes at room temperature and washed four times. Slides were then incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated rat anti-CD45R/B220 primary antibody for 90 minutes at room temperature and then washed with TBS. rabbit anti-phospho-Syk (Cell Signaling Technology). Samples were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and washed three times with TBS. Slides were mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade mounting media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged on a Zeiss 880 laser scanning confocal microscope at the Boston Children’s Hospital Harvard Digestive Disease Center.

RNA isolation, qPCR, transcriptomic and pathway analyses.

RNA was isolated from TRI Reagent samples using phenol-chloroform extraction or column-based extraction systems (Direct-zol RNA Microprep and Miniprep, Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity (260/280 and 260/230 ratios) were measured by NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Purified RNA was analyzed for gene expression by qPCR on a CFX384 real time cycler (Biorad) using pre-designed KiCqStart SYBR Green Primers (MilliporeSigma) specific for Cxcl9 (M_Cxcl9_1), Gbp2 (M_Gpb2_1), Ifit2 (M_Ifit2_1), Rsad2 (M_Rsad2_1), Il6 (M_Il6_1), Cxcl1 (M_Cxcl1_1), Rpl13a (M_Rpl13a_1) or pre-designed PrimeTime qPCR Primers (Integrated DNA Technologies) specific for Gapdh (Mm.PT.39a.1).

For bulk RNAseq analysis, RNA isolated from skin or LN samples was submitted to Genewiz. RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and RNA integrity was checked with RNA Screen Tape on Agilent 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). RNA sequencing library preparation was prepared using TruSeq Stranded mRNA library Prep kit following manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina, Cat# RS-122-2101). Briefly, mRNAs were first enriched with Oligod(T) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 8 minutes at 94°C. First strand and second strand cDNA were subsequently synthesized. The second strand of cDNA was marked by incorporating dUTP during the synthesis. cDNA fragments were adenylated at 3’ends, and indexed adapter was ligated to cDNA fragments. Limited cycle PCR was used for library enrichment. The incorporated dUTP in second strand cDNA quenched the amplification of second strand, which helped to preserve the strand specificity. Sequencing libraries were validated using DNA Analysis Screen Tape on the Agilent 2200 TapeStation (Agilent Technologies), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as well as by quantitative PCR (Applied Biosystems). The sequencing libraries were multiplexed and clustered on 1 lane of flowcell. After clustering, the flowcell was loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2x150 Pair-End (PE) High Output configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software (HCS) on the HiSeq instrument. Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina HiSeq was converted into fastq files and demultiplexed using Illumina bcl2fastq program version 2.17. One mismatch was allowed for index sequence identification. Reads were quality-controlled using FastQC. Illumina adapters were removed using cutadapt. Trimmed reads were mapped to the mouse transcriptome (GRCm38) based on Ensembl annotations using Kallisto (Bray et al., 2016). Transcript counts were imported and aggregated to gene counts using tximport (Soneson et al., 2015). Gene counts were analyzed using the R package DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). When applicable, batch was used as a blocking factor in the statistical model. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified as those passing a threshold of FDR significance threshold (0.05 for skin; 0.01 for lymph nodes, a more stringent threshold thanks to the greater power due to higher number of replicates) where the alternate hypothesis was that the absolute log2 FC was greater than 0. Genes induced by mannan or glucan treatment over saline were plotted in heatmaps using the R package ComplexHeatmap, using Z-scored log2 normalized abundance. Genes were arranged by abundance delta between glucan and mannan (aggregated from multiple time points when appropriate), with a gap delimiting two clusters: genes more highly expressed upon mannan stimulation vs genes more highly expressed upon glucan stimulation. Pathway analysis was performed with the R package hypeR (Federico and Monti, 2020), using hypergeometric enrichment tests of genes belonging to a cluster of interest and the Hallmark gene set collection from the Broad Institute’s MSigDB collection.

For targeted transcriptome sequencing, 25 ng of RNA isolated from sorted cells was retrotranscribed to cDNA using Superscript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Barcoded libraries were prepared using the Ion AmpliSeq Transcriptome Mouse Gene Expression Kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced using an Ion S5 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the ampliSeqRNA plugin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). To quantify the number of DEGs, gene-level fold change < −1.5 or > 1.5 and gene-level p value < 0.05 (ANOVA) were considered. For heatmap representation, DEGs were defined with an F-test FDR less than 0.05 and a log2 fold-change (FC) greater than 1 (or lower than −1) between a mutant and WT control. Hierarchical clustering was performed with Pearson correlation and average linkage. Pathway analysis was performed with the R package hypeR, using Kolmogorov Smirnov Test on genes ranked according to their log2FC.

In vivo CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation assay.