Abstract

The molecular bases for the symbiosis of the amphibian skin microbiome with its host are poorly understood. Here, we used the odor-producer Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and the treefrog Boana prasina as a model to explore bacterial genome determinants and the resulting mechanisms facilitating symbiosis. Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and its closest relatives, within a new clade of the P. fluoresens Group, have large genomes and were isolated from fishes and plants, suggesting environmental plasticity. We annotated 16 biosynthetic gene clusters from the complete genome sequence of this strain, including those encoding the synthesis of compounds with known antifungal activity and of odorous methoxypyrazines that likely mediate sexual interactions in Boana prasina. Comparative genomics of Pseudomonas also revealed that Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and its closest relatives have acquired specific resistance mechanisms against host antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), specifically two extra copies of a multidrug efflux pump and the same two-component regulatory systems known to trigger adaptive resistance to AMPs in P. aeruginosa. Subsequent molecular modeling indicated that these regulatory systems interact with an AMP identified in Boana prasina through the highly acidic surfaces of the proteins comprising their sensory domains. In agreement with a symbiotic relationship and a highly selective antibacterial function, this AMP did not inhibit the growth of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS but inhibited the growth of another Pseudomonas species and Escherichia coli in laboratory tests. This study provides deeper insights into the molecular interaction of the bacteria-amphibian symbiosis and highlights the role of specific adaptive resistance toward AMPs of the hosts.

Subject terms: Transcriptomics, Phylogenetics, Phylogenomics, Microbial ecology, Symbiosis

Introduction

The animal skin represents the interface between the external environment and the body [1]. It is a unique ecosystem characterized by the chemical and physical properties of the epidermis, which is colonized by a community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses, the so-called skin microbiome [2]. The skin of amphibians, in particular, offers favorable conditions for the growth of microorganisms because of its moisture, stable pH, and neutral sugar content [3]. Recent studies have revealed that this ecosystem harbors a diverse and dynamic group of microbes whose composition depends on host phylogeny [4, 5], environmental variables [5, 6], and the presence of pathogens [5]. However, the specific mechanisms underlying this interaction, particularly the synthesis and role of microbial metabolites and the reciprocal effects of the host immune system, are still largely unexplored.

Bacteria from the genus Pseudomonas occur ubiquitously on the skin of amphibians and constitute major components of the microbiome with essential functions [4, 6–9]. For example, some Pseudomonas isolates inhibit the fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis [7], whereas others can produce secondary metabolites exploited by the host. Among them are those producing odorous methoxypyrazines potentially involved in sexual interactions of the treefrog Boana prasina [9], or the highly toxic tetrodotoxin that may mediate defense against predators in the newt Taricha granulosa [10]. However, the genetic basis for the biosynthesis of these compounds and their distribution among the different members of the genus Pseudomonas is still unknown.

On the host side, the amphibian skin produces various antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) [11], which are key components of the innate immune system. While most studies have assessed the broad-spectrum antimicrobial effects of AMPs [11, 12], recent work points toward selective inhibitory effects on the growth of specific microbial taxa [8, 13]. In this sense, AMPs are known to control host-symbiont interaction in other organisms, including plants [14] and insects [15], and they have presumably evolved in metazoan hosts to regulate the resident beneficial microbes rather than to control invasive pathogens [16, 17].

The mechanisms by which bacteria can withstand AMPs are little understood, but they include different strategies like removal by efflux pumps, degradation by membrane proteases, and alteration of membrane charge [18]. Another essential process regulating resistance is the sensing of host AMPs, which often occurs through signal transduction involving two-component regulatory systems (TCSs) [19] where the extracellular loop of the histidine kinase sensor senses external molecules [19, 20]. More than tens of TCSs with sensing domains that share little sequence similarity are found in different bacteria species and confer different ligand specificities [21]. Specifically, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, one of the most studied pseudomonads, pathogenicity and resistance have been associated with sensing and exporting various antimicrobial substances by at least five TCSs and by efflux pumps of the resistance nodulation family [22–25].

In the present study, the symbiosis between a methoxypyrazine-producing Pseudomonas sp. (hereafter Pseudomonas sp. MPFS) and the Brazilian treefrog Boana prasina was analyzed by a combination of different omics technologies [26], inhibitory assays, and molecular modeling. These analyses aimed to identify the origin of the relevant bacterial metabolites that may be beneficial to the host and the bacterial resistance mechanisms against the host’s immune system, which would provide further insights into the selective action of AMPs in the interaction. In addition, these results contribute to our understanding of the principles underlying the symbiosis between amphibians and their skin microbiome.

Materials and methods

Genome sequencing and annotation of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS

Pseudomonas sp. strain MPFS was isolated from the skin of the South American treefrog Boana prasina as part of a larger cultivation study (originally isolated as Pseudomonas haplotype 11) [9]. This lineage was selected because it was identified as the biological source of the odorous methoxypyrazines potentially acting as sex pheromones in its frog’s host [9]. In addition, it was consistently found in specimens from different populations of the frog host, suggesting a tight symbiotic relationship [9]. The complete genome sequence was determined by a combination of single-molecule real-time (PacBio RSII; Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA) and MiSeq sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and was assembled with the “RS_HGAP_Assembly.3” protocol included in SMRT Portal version 2.3.0.

Automated genome annotation was done using Prokka [27] and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [28]. EggNOG 4.5 was used to retrieve clusters of orthologous groups of proteins (COGs) functional categories [29]. Biosynthesis gene clusters (BGCs) potentially involved in the production of novel secondary metabolites were predicted using antiSMASH (vbeta5; https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org) [30]. The whole-genome project was deposited at NCBI GenBank (BioProject IDPRJNA684134, Acc. No. CP066123). For additional details of DNA extraction, genome sequencing, and assembly, see Supplementary Methods.

Phylogenetic analysis

To explore the evolutionary context of genes potentially involved in symbiosis, we first assessed the phylogenetic position of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS among the known clades of Pseudomonas spp. recognized previously [31]. One hundred and sixty Pseudomonas species, including most of the type strains of the 13 Pseudomonas groups and the 10 subgroups from the Pseudomonas fluorescens Group, were selected from Hesse et al. [31], and their genomes were downloaded from GenBank (NCBI). Cellvibrio japonicus was used as the outgroup. Information on the strains included in the analysis and NCBI accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table S1. A matrix of 243 protein-coding genes (76,157 amino acid sites) of single-copy housekeeping genes present in at least 90% of Pseudomonas genomes was constructed using ProteinOrtho v4.26, which predicted orthologous proteins from the complete genomes [32] employing default parameters (Supplementary Methods). A maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree was inferred with RAxML (v8.2.12) [33] using 100 replicates and the BLOSUM62 substitution matrix; 500 nonparametric bootstraps were used to estimate node support. The Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) web portal [34] was used to visualize the phylogenetic tree and gene annotations.

The genome-based platform Type Strain Genome Server (TYGS) [35] was used to find additional close relatives of Pseudomonas sp. MFPS and to determine the species and subspecies boundaries of this strain. Aside from the eight closest type strains identified by TYGS, two additional yet unnamed strains (Pseudomonas sp. CMR5c and Pseudomonas sp. CMR12a) were included in the analyses based on exploratory BLAST analysis. Intergenomic distances and a balanced minimum evolution tree with branch support were estimated using the Genome BLAST Distance Phylogeny and FASTME 2.1.4, respectively. Finally, all-against-all pairwise average nucleotide identity (ANI) values were calculated using FastANI [36] for this subset, using a species cutoff of 95%.

Biosynthetic gene clusters, two-component regulatory systems, and efflux pumps

To understand the distribution and evolutionary context of BGCs identified in Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, the occurrence of these clusters, and the total number of BGCs were compared with those identified in the closely related strains from a matrix of orthologous proteins constructed with ProteinOrtho v4.26 employing the default parameters. Previous studies have shown that at least five TCSs (PhoPQ, ColRS, PmrAB, ParRS, and CprRS) are involved in the resistance of P. aeruginosa PAO1 against AMPs like cyclic polymyxin, but also against linear peptides [23, 24]. Therefore, the matrix of orthologous proteins was also used to assess the presence/absence of protein orthologues of these five TCSs in the genus Pseudomonas. TCSs were considered orthologous when both the sensor histidine kinase and the response regulator were orthologous or when at least one member of the pair was retrieved as orthologous, and its pair shared the same neighboring genes of the orthologous system. The phylogeny of TCSs was analyzed based on the presence/absence matrices for each of these five TCSs in all Pseudomonas genomes and visualized using the iTOL web portal [34]. The ancestral state of the TCSs in pseudomonads was reconstructed in TNT [37], considering binary characters (presence/absence) and using the maximum parsimony criterion. Similarly, the phylogeny of the four multidrug efflux pumps MexAB-OprM, MexXY-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN of the resistance nodulation division family, known to export a variety of antimicrobial substances in P. aeruginosa [22], was determined based on the presence/absence matrices.

Identification of AMPs in the skin of Boana prasina and in silico characterization

One male and one female specimen of the treefrog Boana prasina (Anura: Hylidae) were collected from São Francisco Xavier, São Paulo, Brazil (22° 55’19”S, 45°53’14”W), and the total RNA was extracted from their dorsal skin (Supplementary Material). The cDNA libraries were prepared using TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit v2 (Illumina) and sequenced in a HiSeq2000 (2 × 100 PE; Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA; Supplementary Material).

Sequences from both individuals were de novo assembled with Trinity v2.11 using default parameters [38] creating a transcript consensus. For a preliminary assessment of potential protein-coding regions, the contigs were translated with ORFpredictor v3.0 [39]. Finally, the relative gene expression was quantified using the consensus skin transcriptome of the male and female B. prasina employing Kallisto [40]. The raw transcriptomic dataset was deposited at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject ID number PRJNA675859).

Prepropeptide sequences of AMPs in the transcriptome of B. prasina were identified based on the conserved six-amino acid motif “VSLSIC” of signal peptides previously described in other species from the genus Boana [41, 42]. Prepropeptides were further examined concerning their tripartite structure, comprising a signal peptide, a spacer region rich in acidic residues, and the mature peptide sequence [42]. Mature peptides were compared in silico to AMPs from public databases (Supplementary Material).

Effect of antimicrobial peptides on bacterial growth

Two novel mature peptides identified in the transcriptome of B. prasina, named here raniseptin-Prs and prasin a-Prs, were chosen to assess whether these peptides can inhibit the growth of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS (Supplementary Material). The synthetically synthesized mature peptides raniseptin-Prs and prasin a-Prs and the synthetic cleaved (at the Glyn-Lysn+1 site) peptide of the raniseptin-Prs following previous studies [42, 43] were purchased from Dg-Peptide Co. (Hang Zhou City, China).

Experimental assays were conducted with Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, P. aeruginosa PAO1, P. brassicacearum DSM 13227, and Escherichia coli DSM 498. E. coli has been previously tested using skin peptides from different amphibian species [11, 41, 42]. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P. brassicacearum served to test whether the CprRS system that is present in P. aeruginosa and Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, but absent in P. brassicacearum, can mediate bacterial resistance against AMPs. All tests were performed in triplicate and according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2012). Growth curves were constructed for each treatment based on their data distribution using the locally weighted regression “loess” in R. A standard procedure was used to determine differences between treatments. Briefly, the maximum growth rate and its 95% confidence interval were calculated from the log-linear part of growth curves from each AMP concentration and the control treatment without AMPs. When the confidence intervals for an AMP treatment and control did not overlap, they were judged to be significantly different.

Modeling of TCSs structures and AMP docking

To examine the specificity of peptide recognition, we used de novo protein modeling of sensory domains of the sensor histidine kinases PhoQ, ColS, PmrB, ParS, and CprS from P. aeruginosa PAO1 [23–25] and Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, and raniseptin-Prs as the peptide model. These yielded three-dimensional structures of the sensory domain and enabled in silico docking experiments of the sensor histidine kinases-peptide complexes. The molecular models of these complexes were constructed with HADDOCK2.4 [44] by docking the raniseptin-Prs as an extended α-helical peptide amidated at the C-terminal end to the β-sheet enriched portion of the predicted sensory domain of sensor histidine kinases. Because the opposite region of the sensory domain, which comprised the main N-terminal α-helix, was expected to participate in dimer formation [45], it was blocked from participating in the molecular interaction. The biological relevance of the generated models was refined by employing geometric and energetic selection criteria. Scores for the binding of raniseptin-Prs to the sensory domains of sensor histidine kinases were determined in arbitrary energy units (a.e.u.). Details on model construction, validation, and selection criteria can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Results and discussion

Genome sequence of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS

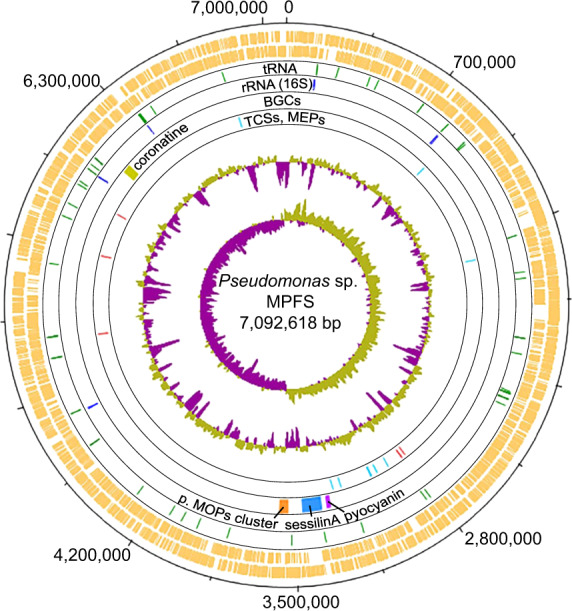

Pseudomonas sp. MPFS is the first Pseudomonas strain with a high-quality, closed genome from an amphibian skin microbiome. The genome of this strain comprises one large, circular chromosome (7,092,618 bp; Fig. 1) and represents one of the largest sequenced genomes within the genus Pseudomonas (mean, 5.6 ± 1.1 Mbp; Supplementary Table S1). The GC content is 63.1 mol%, and extrachromosomal elements are lacking. Annotation with Prokka predicted five copies of the ribosomal RNA operon, 80 tRNA genes, and 6384 protein-coding sequences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Circular plot of the 7.1 Mbp Pseudomonas sp. MPFS chromosome and COG functional categories.

The eight circles from the outermost to the innermost depict either the location of different genes or general genome features: circles 1 and 2 (orange) predicted coding sequences on the positive and negative strands, respectively; circles 3 (green) and 4 (blue), tRNA and rRNA genes, respectively; circle 5, biosynthetic clusters (BGCs) with high similarities (≥75%) to BGCs with known function, and a nonribosomal peptide synthetase putatively involved in the synthesis of methoxypyrazines (p. MOPs cluster, orange); circle 6, the five two-component system genes (TCSs, red) and eight multidrug efflux pumps (MEPs, cyan) known to mediate adaptive resistance against antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and; circle 7 and 8, %G+C and GC skew, respectively.

This complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS offers a novel basis for studying biotic interactions between bacteria and amphibians because Pseudomonas strains are common members of the skin microbial community of this group of vertebrates [4, 6, 46]. The only two other bacterial species isolated from the amphibian skin are the thermophilic pathogen Mycobacterium xenopi (strains DSM 43995T and CCUG 29060) and an isolate of the genus Pigmentiphaga [47]. According to the BacDive database [48], only M. xenopi is available up to this point.

Phylogenomic affiliation of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and distribution of symbiosis amongst pseudomonads

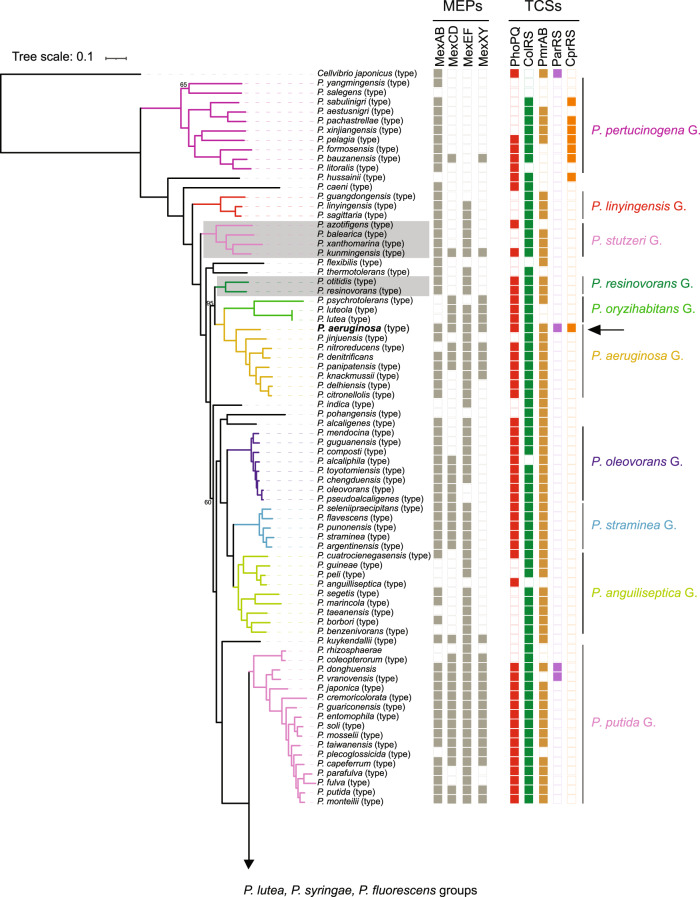

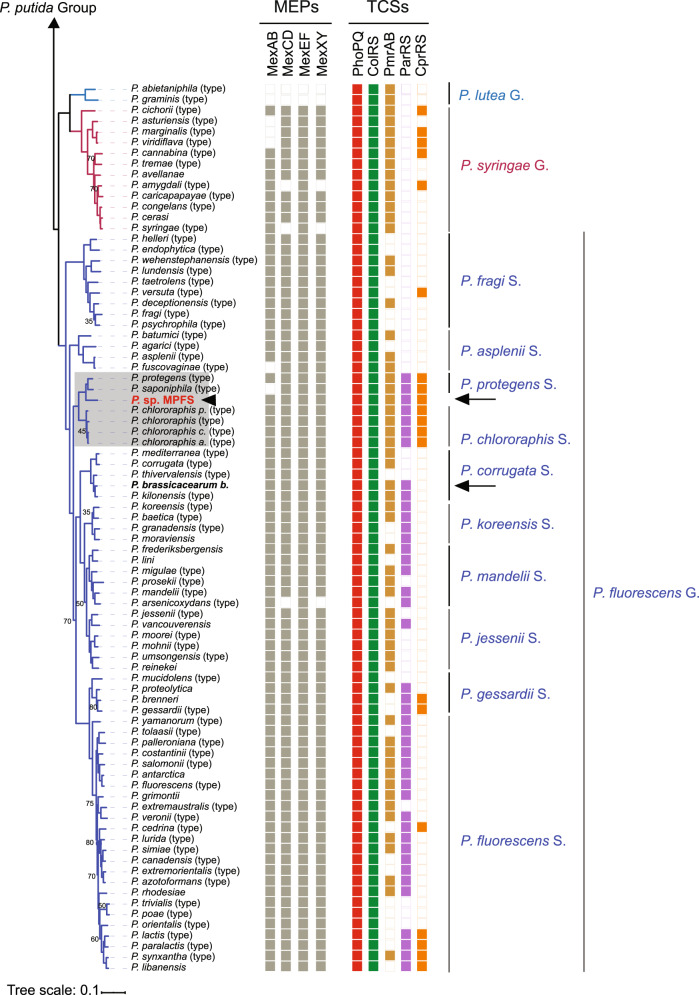

The phylogenomic tree based on 243 orthologous protein sequences of housekeeping genes revealed that Pseudomonas sp. MPFS is the sister clade of the P. protegens Subgroup closely related to the P. chlororaphis Subgroup (Fig. 2). This phylogenomic analysis also confirmed the monophyly of the previously recognized 13 Pseudomonas groups and 10 subgroups of the P. fluorescens Group [31] at high bootstrap support (95%). A further taxonomic delineation with the TYGS [35] showed that two genomes absent in the protein phylogenetic analysis (i.e., “P. aestus” CMAA1215, whose name is not validly published under Bacteriological Code, and P. piscis MC042) were also closely related to Pseudomonas sp. MPFS.

Fig. 2. Phylogenetic relationships of Pseudomonas obtained with maximum likelihood based on protein sequence alignments of orthologous genes from 141 type strains (type), 17 non-type strains, and the yet undescribed Pseudomonas sp. MPFS from this study (arrowhead, red, bold).

Cellvibrio japonicus was included as an outgroup. Nodes without numbers indicate bootstrap values higher than 95%. Branch colors depict Pseudomonas spp. groups (G.) and P. fluorescens subgroups (S.), and portions of the tree highlighted in gray depict groups or subgroups that differ from previous genome-based phylogenies. Columns on the right indicate the presence/absence of genes encoding for multidrug efflux pumps (MEPs) and two-component sensory systems (TCSs) known to participate in adaptive resistance in P. aeruginosa. Arrows and names in bold font indicate the strains selected for inhibition experiments.

Subsequent digital DNA–DNA hybridization with strains from the P. protegens and P. chlororaphis subgroups produced unexpectedly low values (<32% and <28%, respectively; Supplementary Table S2), indicating that strain MPFS constitutes a separate, previously unrecognized species. Based on the phylogenomic tree obtained with TYGS (Fig. 3A) and on the dDDH values and intergenomic distances (Supplementary Table S2), we designated the new P. piscis Subgroup within the P. fluorescens Group. This subgroup, in turn, comprises two distinct species clusters, the first consisting of P. piscis, “P. aestus,” and Pseudomonas sp. CMR5c and the second consisting of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and Pseudomonas sp. CMR12a (Fig. 3A). These species clusters were also independently confirmed by ANI values (Supplementary Table S3).

Fig. 3. Phylogenomic tree showing the position of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS in the most closely related clades and overview of ecological niches used by different clades of Pseudomonas.

A Based on the tree inferred with FastME 2.1.4 using the TYGS platform and on the genome BLAST distance phylogeny method (GBDP), we defined P. piscis Subgroup (S.) as a new clade within the P. fluorescens Group. Branch lengths are scaled in terms of GBDP distance formula d5, and the numbers on branches are GBDP pseudo-bootstrap support values from 100 replications. Different square colors on the right panel depict whether the strains belong to a given species and subspecies cluster, whereas the color intensity of the G+C content depicts their relative values. B A simplified list depicting known biological sources from where different strains (str.) from the Pseudomonas groups and Pseudomonas fluorescens subgroups included in this study were identified. Red rectangles on symbols depict pathogenic interactions. GS genome size, fl free-living strains, sy str symbiotic strains.

Representatives of these three groups form symbiotic associations with different crop plants, colonizing roots, and leaves [49, 50], and isolates were also obtained from crustaceans, soil arthropods, intestines, and head ulcers from fish, and now also from amphibians (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S4). Several members are free-living in habitats like river clay, mangrove sediments, the cocoyam rhizosphere, and, in the case of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, in permanent ponds. Recently, it was shown that the root-colonizing and plant-beneficial P. protegens CHA0 could also have a commensalistic relationship with insect vectors, indicating that it can switch between hosts using insects for dispersal [50, 51]. Thus, it appears that during evolution, members of the P. piscis, P. protegens, and P. chlororaphis subgroups developed the capacity to occupy diverse ecological niches, including plants and animals. Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and other Pseudomonas spp. of the amphibians skin microbiome thus may undergo a distinct life cycle that awaits future detailed analysis. The larger average genome size of the three subgroups (mean range 6.9–7.1 Mb) compared to genomes of all the remaining clades of Pseudomonas (<6.5 Mb; Fig. 3B) and the evolutionary analysis of genes potentially involved in the interaction with animals host as described in the subsequent sections yielded further insights into the ecological versatility of bacteria from the three clades.

Potential roles of genes and biosynthetic gene clusters in the symbiosis

When compared with other Pseudomonas species, 168 genes were exclusively found in Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, from which only 32 were assigned to COG functional categories that correspond mainly to amino acids, lipids, and secondary metabolite transport and metabolism (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). When the comparison also includes members of the P. piscis, P. protegens, and P. chlororaphis subgroups, we found that they share unique proteins involved in cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (five genes) and defense mechanisms (two genes; Table 1 and Supplementary Table S6) that do not occur in other pseudomonads. Genes in these categories include multidrug efflux pumps that may have a role in the colonization of their animal and plant hosts.

Table 1.

Specific genes classified according to COG categories present in Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and in closely related clades with no ortholog in the other Pseudomonas spp.

| COG categorya | Clade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition (name) | MPFS | MPFS CMR12a | P. piscis | P. piscis P. chl. P. prot. |

| Chromatin structure and dynamics | 1 | |||

| Energy production and conversion | 2 | 1 | ||

| Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning | 1 | |||

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | 8 | 1 | 6 | 3 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 1 | 1 | ||

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 1 | |||

| Lipid transport and metabolism | 6 | 1 | ||

| Translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Transcription | 2 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Replication, recombination, and repair | 3 | |||

| Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Heat-labile enterotoxin alpha chain A | 1 | |||

| RHS repeat | 1 | |||

| Carbohydrate-selective porin, OprB family (oprB) | 1 | |||

| multidrug efflux pump (mexE) | 1 | 1 | ||

| RND efflux system | 1 | |||

| Fimbrial chaperone protein (lpfB) | 1 | |||

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | 4 | 1 | ||

| Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport | 1 | 1 | ||

| Defense mechanisms | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Multidrug resistance protein, MATE family (norM-2) | 1 | |||

| AAA domain, putative AbiEii toxin (nodI) | 1 | |||

| ABC transporter transmembrane region (mdlB) | 1 | |||

| Multidrug efflux pump (mexF) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Protein with predicted functionb | 32 | 6 | 22 | 12 |

| Hypothetical protein/unknown function | 136 | 29 | 23 | 54 |

| Total | 168 | 35 | 45 | 66 |

MPFS Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, CMR12a Pseudomonas sp. CMR12a, P. chl. P. chlororaphis, P. prot. P. protegens.

aGenes within the categories in bold are displayed because of their potential relevance in resistance mechanisms against the host’s antimicrobial substances.

bBecause one gene can be classified in more than one COG category, the number of genes with predicted function is smaller than the sum of the genes in each COG category.

Of the total of 16 putative BGCs identified in Pseudomonas sp. MPFS (Figs. 1 and 4 and Supplementary Table S7), only three have high sequence similarities (≥87%) with clusters of known function available in the MiBIG database (Supplementary Table S7). These BGCs are involved in the production of Coronatine (NRPS-like), Pyocyanin (phenazine), and Sessilin A or Tolaasin I/F (cyclic depsipeptides members of the Tolaasin Group [52]; Figs. 1 and 4). One BGC encodes a two-module, five-domain nonribosomal peptide synthetase (Fig. 4A) whose product resembles the aminoaldehyde intermediate of pyrazinones [53] and an S-adenosyl-L-methionine-dependent methyltransferase that can methylate a pyrazinone intermediate during biosynthesis of methoxypyrazines. Predictions on this cluster also indicate an unknown substrate specificity of the adenylation domain A1, and a relaxed substrate specificity for aliphatic amino acids like alanine, valine, leucine, and isoleucine for the adenylation domain A2. This seeming lack of specificity likely explains the diversity of methoxypyrazines identified previously in the volatile profile of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS (Supplementary Fig. S1) [9, 54].

Fig. 4. Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and from strains within the P. piscis, P. protegens, and P. chlororaphis subgroups with reliable secondary metabolite assignment (sequence similarity ≥75% with clusters of known function).

A Three BGC types, phenazine (top), nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) (second from the top), and NRPS-like (third from the top), have high sequence similarities to clusters occurring in other Pseudomonas strains (denoted on the right of the panel). In addition, a dimodular NRPS putatively involved in the synthesis of methoxypyrazines was identified (bottom). B Total number of BGCs and presence/absence of BGCs with reliable secondary metabolite assignment. Information on the presence/absence of antifungal activity for these compounds was obtained from the literature as detailed in Supplementary Table S8.

These results suggest that metabolites from the Pseudomonas sp. MPFS might significantly affect different aspects of the biology of its frog host. For instance, the broad antifungal spectrum of Pyocyanin and the Tolaasin depsipeptides (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S8) make them good candidates for a protective function against the amphibian fungal pathogen B. dendrobatidis. This function would not be restricted to this specific strain and might imply functional redundancy in the bacterial skin community. For instance, the different strains within the P. piscis Subgroup carry between three to five BGCs with antifungal activity, including 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol that effectively inhibits B. dendrobatidis (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Table S8) [55]. In addition, and as shown previously [9], methoxypyrazines could mediate sexual interactions of its host.

Resistance to AMPs in Pseudomonas sp. MPFS

The analyses of the distribution of Mex efflux pumps revealed that the four pumps described in P. aeruginosa (i.e., MexAB-OprM, MexXY-OprM, MexCD-OprJ, and MexEF-OprN) are widespread in Pseudomonas (Fig. 2). Because these pumps are known to mediate intrinsic resistance of this species to several antibiotics [22], this distribution pattern may reflect a highly conserved mechanism to deal with such substances. However, we found two extra copies of the MexEF pumps and two efflux pumps of the ABC and MATE families among the specific genes of P. piscis, P. chlororaphis, and P. protegens subgroups with no orthologs in other Pseudomonas spp. (Table 1).

The analyses of the distribution of the five TCSs conferring resistance to P. aeruginosa (i.e., PhoPQ, ColRS, PmrAB, ParRS, and CprRS) [23, 24] to the cationic AMP polymyxin, but also to other cationic AMPs, revealed distinct patterns and evolutionary histories in Pseudomonas. The PhoPQ, ColRS, and PmrAB systems are widespread in the genus (Fig. 2). The phylogenetic reconstruction shows that the presence of PhoPQ and ColRS is an ancestral state of Pseudomonas (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3), whereas PmrAB has a more complex evolutionary pattern with several independent acquisitions and losses (Supplementary Fig. S4). In contrast, the presence/absence patterns of the ParRS and CprRS systems show that both are derived characters in Pseudomonas (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6). Our analyses indicate that both evolved independently within subclades of the P. fluorescens Group and in very few strains outside this group (CprRS in the groups of P. pertucinogena and P. syringae, and P. aeruginosa; ParRS in P. putida Group and P. aeruginosa) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6).

In the last decade, AMPs have been increasingly recognized as key agents of symbiotic interactions between bacteria and different hosts, ranging from deep-branching metazoans to insects and plants [14–16]. In this context, it is significant that the AMP Tachyplesin I elicits the overexpression of MexE in P. aeruginosa [25]. This evidence, along with our results on the distribution pattern of Mex efflux pumps, suggests that they are conserved detoxification mechanisms in Pseudomonas, also participating in more specialized roles like resistance to AMPs from the host. It is also significant that ParRS or CprRS occur in Pseudomonas clades like the P. syringae Group and the P. fluorescens Subgroup, given that many representatives form close associations with plants and animals (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the occurrence of the five two-component systems in all strains from the P. chlororaphis, P. protegens, and P. piscis subgroups, as well as P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figs. S2–S6) suggests the existence of a highly diversified sensing mechanism for AMPs. Though experimental evidence needs to be gathered, this diversification likely reflects the capability of these species to shift between different animal and plant hosts [51].

Transcriptomic identification and analysis of cationic AMPs from the amphibian host

Based on the conserved sequence motif VSLSIC of the N-terminal signal peptide and the distinct regions of the AMP precursors (signal peptide, acidic region, and mature peptide), we identified nine prepropeptides from the skin consensus transcripts of Boana prasina (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S9). Blast analysis using the AMP database identified all as novel peptides. Following the proposed nomenclature [56], and based on the sequence similarity, four peptides were assigned to the already described peptide families raniseptin and hylin (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S7), and the others were named prasin with the suffix “a”–“e.” Four isoforms were recognized in six of the nine peptides, differing mainly at the nucleotide sequence downstream of the signal peptide region and at the signal peptide region itself (Supplementary Table S10). Based on the relative quantification of the individual reads, we estimate that peptides raniseptin-Prs and hylin-Prs have high expression levels and are among the 50 and 450 highest expressed proteins in females and males, respectively (Supplementary Table S11).

Table 2.

Mature peptides identified in the skin transcriptome of Boana prasina.

| Name | Mature peptide | Length | MW | Net charge | GRAVY | µH | AMP Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| raniseptin-Prs | GIMDTLKKIGKKVGKVALDVAKNYLNQEK | 29 | 3202.85 | +4 | –0.448 | 0.469 | 0.8595 |

| hylin-Prs1 | FIGALIPALAGVIGGLIRKG | 20 | 1936.41 | +2 | 1.490 | 0.488 | 0.9370 |

| hylin-Prs2 | FLGALIPAAMGLISHLVNKG | 20 | 2022.48 | +1 | 1.215 | 0.390 | 0.8920 |

| hylin-Prs3 | FLGALIPAIAGAISGLINRG | 20 | 1924.32 | +1 | 1.370 | 0.455 | 0.8715 |

| prasin a-Prs | GFWHNLKNIFIETGKGIKRVWKNFFTGS | 28 | 3325.87 | +4 | –0.364 | 0.556 | 0.9935 |

| prasin b-Prs | GALERVKKYMFPIRYG | 16 | 1928.33 | +3 | –0.394 | 0.278 | 0.4835 |

| prasin c-Prs | GIMDTLKKIRKRNRGMKNLMKREESWIL | 28 | 3446.20 | +6 | –0.986 | 0.399 | 0.6445 |

| prasin d-Prs | SIYKLGGSCLDVPHIGRICG | 20 | 2088.47 | +1 | 0.455 | 0.201 | 0.6965 |

| prasin e-Prs | ELMERGMPWPPPFLPE | 16 | 1926.28 | –2 | –0.631 | 0.296 | 0.0705 |

Amino acid length, theoretical molecular weight (MW), total net charge, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), hydrophobic moment (µH), and probability of being AMPs estimated with Random Forest algorithm (AMP Prob.) were determined in silico. Peptides in bold were selected for bacterial growth experiments.

In silico characterization of mature peptide sequences revealed that all, except prasin e-Prs, have a cationic character with net charges ranging from +1 to +6. We also found that five of these cationic peptides contain α-helices with an amphipathic character and a high probability of representing AMPs (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S8). Given the proposed action mechanisms of membrane-active AMPs [57, 58], this net positive charge may favor the initial electrostatic attraction of the peptides to negatively charged bacterial membranes, while the amphipathic α-helix conformation may promote the integration of peptides into the microbial membrane, disrupting its physical integrity and ultimately killing the cell. Accordingly, wheel projection diagrams show distinct hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces on opposite sides of a peptide (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Because cationic AMPs of the raniseptin and hylin peptide families display broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, including E. coli, S. aureus, E. faecalis, B. subtilis, and P. aeruginosa [42, 59], we were interested in understanding their effect on different Pseudomonas strains as one of the main representatives of the skin bacterial community of amphibians [4, 7–9]. Thus, we chose raniseptin-Prs and the highly cationic prasin a-Prs from B. prasina to test their activity against Pseudomonas sp. MPFS, P. aeruginosa PAO, and P. brassicacearum DSM, using E. coli as control.

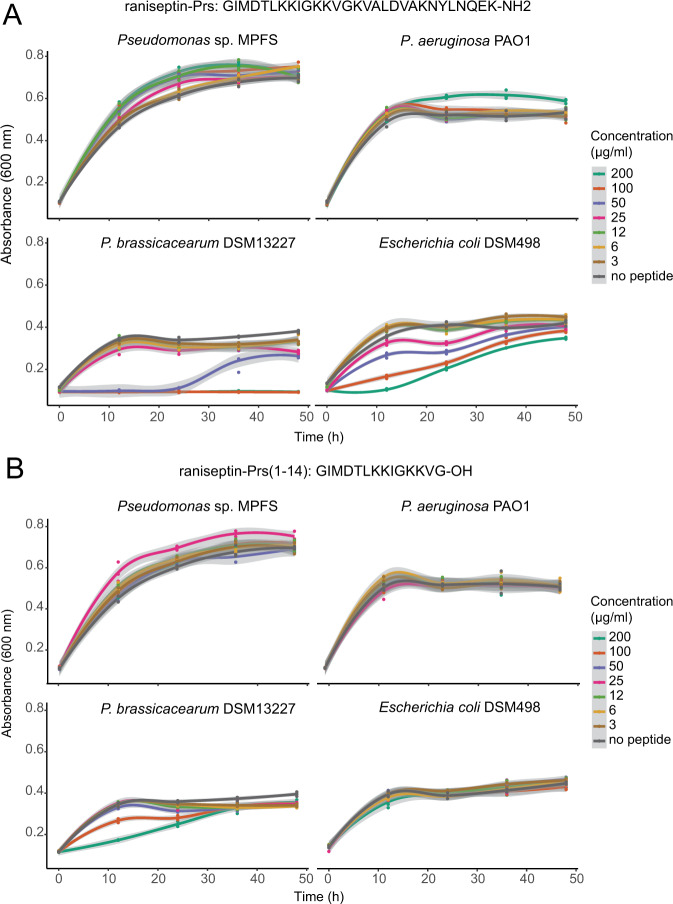

Effect of skin defense peptides on the growth of bacterial isolates

Full-length synthetic peptides raniseptin-Prs and prasin a-Prs (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. S10), as well as cleaved peptides raniseptin-Prs (1–14) and raniseptin-Prs (15–29) (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S11), did not inhibit the growth of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and P. aeruginosa PAO1, even at the moderate to high concentrations tested (~120 µM). In contrast, all full-length peptides inhibited the growth of P. brassicacearum and E. coli at concentrations equal to or higher than 100 µg/ml (~30 µM; Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. S10). However, when we tested cleaved peptides, no inhibition was observed in E. coli (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S11). The effect of cleaved raniseptin-Prs (1–14) and raniseptin (15–29) was variable in P. brassicacearum. Cleaved raniseptin-Prs (1–14) inhibited growth at concentrations higher than 100 µg/ml during the first 12 h of the experiment (Fig. 5A), whereas no inhibition of raniseptin-Prs (15–29) was detected at any concentration tested (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Fig. 5. Bacterial growth curves of three Pseudomonas strains and Escherichia coli exposed to different concentrations of the cationic antimicrobial peptide raniseptin-Prs from Boana prasina.

A full length peptide, and B N-cleaved peptide at the Gly14-Lys15 position. Shaded areas in each curve represent 95% confidence intervals.

These results demonstrate that the symbiotic Pseudomonas sp. MPFS would tolerate the high concentrations of raniseptin-Prs, and prasin a-Prs found on the skin environment of B. prasina. They also showed that peptide cleavage generates a drastic decrease in its antimicrobial activity, which agrees with previous biological assays of raniseptins [42]. Interestingly, our model predictions show that raniseptin-Prs may adopt either a single α-helix or a two α-helix motif joined by a random coil (Supplementary Fig. S12). This coil matches the Glyn-Lysn+1 of the peptide. This motif is a cleavage site recognized for endopeptidases that can be either produced by microorganisms [57] or by the amphibians themselves [60]. Previous studies showed that skin peptides from amphibians could have a selective antibacterial function or even favor the growth of their natural microbiota [8, 13]. We showed here that the selective effect of AMPs is a mechanism that likely contributes to the establishment of specific bacteria in the amphibian skin microbiome, including the symbiont Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and that peptide cleavage mechanisms can lower the strength of this selectiveness.

Molecular modeling of TCS and their docking with AMPs

Based on our results and previous studies [24, 61], we inferred that the sensory domains of the sensor histidine kinases of the different TCSs of Pseudomonas sp. MPFS may differ in their affinity to cationic AMPs, and that CprRS is necessary for the symbiont to overcome the AMPs from its amphibian host. To test these inferences, we modeled the structure of TCSs from Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and P. aeruginosa PAO1, and their interaction with raniseptin-Prs (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Figs. S13–S18). The predicted structures are similar for all five sensory histidine kinases: PhoQ, ColS, PmrB, ParS, and CprS, from both strains (Supplementary Figs. S13 and S14). Furthermore, all models exhibited good quality after energy minimization (Supplementary Table S12) and a similar folding. Basically, one or two helixes were positioned next to the transmembrane regions flanking the N- and C-terminal regions and four to five stranded antiparallel β-sheets in the central portion of the sequences (Fig. 6A and Supplementary Figs. S15 and S16). This three-dimensional structure is a common extracytoplasmic motif of signaling proteins known as PER-ARNT-SIM-like domains (Supplementary Fig. S17 and Supplementary Table S13) [62–64]. These domains can sense both small molecules and proteins [63, 65] through the ligand-binding pocket conformed mainly by the β-sheets rich portion of the sensor [45, 66].

Fig. 6. Tertiary structure model of the sensory periplasmatic domain of the sensory histidine kinases PhoQ and CprS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1 (left panel) and Pseudomonas sp. MPFS (right panel), and modeled docking with the peptide raniseptin-Prs.

A Both sensory domains form a PAS-like fold. B Net charge at pH = 7.0 and electrostatic potential (±2kT/e) visualized over molecular surface. The red to blue color gradient depicts the negative to positive potentials, respectively. The Asp and Glu residues near the expected membrane region are depicted for all sensory domains. C Structure of complexes of raniseptin-Prs with PhoQ and CprS and respective scores, in arbitrary energy units (a.e.u.), obtained by docking. The hydrophobic residues of raniseptin-Prs are shown as gray dots. Cytoplasmic membrane is represented only for reference.

Although the exact mechanisms by which AMPs activate TCSs are not understood, we examined our results considering the most accepted model described in Salmonella typhimurium that predicts that the negatively charged surface of the sensor PhoQ in proximity to the membrane senses cationic AMPs [65]. We observed marked differences in the negative net charges and a different distribution of aspartate and glutamate residues in the five sensory domains of sensor histidine kinases from both Pseudomonas strains (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Figs. S15B and S16B). Although the aspartate and glutamate residues occur along all the surfaces of the sensory domains, they have a higher density in the antiparallel β-sheet of ColS, ParS, and CprS located near the membrane. Consistently, the electrostatic potentials exhibit the same pattern (Fig. 6B and Supplementary Figs. S15B and S16B), with CprS showing the highest net negative charge imbalance.

The best scores for the binding of the sensory domains from Pseudomonas sp. MPFS and P. aeruginosa to the frog’s peptide raniseptin-Prs were obtained for CprS and ColS from Pseudomonas sp. MPFS (–43.6 and –55.0 a.e.u., respectively; Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. S15C and Supplementary Table S14), and for CprS from P. aeruginosa (–54.1 a.e.u; Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. S16C and Supplementary Table S14). Lower affinity scores (ranging from –34.8 to –10.0 a.e.u) were obtained for ColS from P. aeruginosa and the ParS or PmrB from both strains (Supplementary Figs. S15C and S16C and Supplementary Table S14), whereas PhoQs from both strains exhibited repulsive or zero scores (–0.1 to 9.1 a.e.u.; Fig. 6C). Taken together, our results suggest that adaptive resistance to cationic AMPs in Pseudomonas may have different scenarios involving more than one TCSs, in which CprRS combined with either or both ParRS and ColRS are key participants.

Conclusions

We have shown here that the Pseudomonas sp. MPFS strain isolated from the skin of a treefrog has a large and complex genome rich in regulatory elements, consistent with environmental versatility. This strain and its close relatives possibly evolved to occupy diverse ecological niches, including plants and animals, indicating that bacteria from these lineages are facultative symbionts with a horizontal transmission mode and capable of host switching. Our results suggest a complex frog–bacterium interaction involving the production of secondary metabolites by the bacterium’s BCGs that could mediate defensive and reproductive roles in its host. In turn, the host secretes AMPs that may regulate the microbiome by inhibiting the growth of some bacteria but with no effect on others. Such differential activity of AMPs can be traced to the presence of resistance mechanisms in the frog symbionts, specifically, evolutionarily derived two-component systems and multidrug efflux pumps, whose phylogenetic distribution in Pseudomonas matches that of the clades exhibiting higher host niche plasticity. Our findings likely go beyond this particular model and may be representative of metabolic interactions in other amphibian–bacteria systems, as well as molecular mechanisms involving host defense peptides in other symbiotic systems.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to members of the Vences lab and the DSMZ for many helpful suggestions while conducting this work, especially Miguel Vences, Joana Sabino Pinto, Heike Freese, and Juliane Hartlich. We thank the Pupo Lab for their assistance handling the Pseudomonas sp. MPFS strain and Simone Severitt for excellent technical assistance regarding PacBio genome sequencing. We also thank Santiago Di Lella, Sasha Greenspan, Julian Ferreras, and Livia Zaramela for productive comments and discussions. This research was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation FAPESP grants (#2013/50741-7, #2013/50954-0, #2020/02207-5; postdoctoral fellowships #2014/20915-6 and #2017/23725-1 to AEB, #2017/26162-8 to MLL). The research was also supported by a grant from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES; 88881.062205/2014-01, to CFBH, and MLL; and postdoctoral fellowship 88887.464731/2019-00 to CAF). CNPq for research fellowships (306623/2018-8). AEB and MMM are researchers of CONICET. Collection permits and genetic heritage access permits for both treefrogs and bacteria were issued by SISBIO (Permits 41508-8, 50071-1, 50071-2, 57098-1) and SISGEN (A1FC113, A9EC80A, A299B7D), respectively.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: AEB, BB, MLL, NPL, JO; methodology: AEB, BB, MLL, MMM, CS; data curation: AEB, BB, MLL, MMM, CS, JO; modeling, CAF; investigation: AEB, BB, MLL, CAF, MMM, JO; writing the original draft: AEB with substantial contributions from MLL, CAF, MMM, JO; reviewing and editing: AEB, BB, MLL, CAF, MMM, CS, CFBH, NPL, JO; funding acquisition: CFBH, NPL, JO.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrés E. Brunetti, Email: andresbrunetti@gmail.com

Norberto P. Lopes, Email: npelopes@fcfrp.usp.br

Jörg Overmann, Email: joerg.overmann@dsmz.de.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41396-021-01121-7.

References

- 1.Gallo RL, Hooper LV. Epithelial antimicrobial defence of the skin and intestine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:503–16. doi: 10.1038/nri3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erin Chen Y, Fischbach MA, Belkaid Y. Skin microbiota-host interactions. Nature. 2018;553:427–36. doi: 10.1038/nature25177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toledo RC, Jared C. Cutaneous granular glands and amphibian venoms. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1995;111:1–29.

- 4.Walke JB, Becker MH, Loftus SC, House LL, Cormier G, Jensen RV, et al. Amphibian skin may select for rare environmental microbes. ISME J. 2014;8:2207–17. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jani AJ, Briggs CJ. Host and aquatic environment shape the amphibian skin microbiome but effects on downstream resistance to the pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis are variable. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:487. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bletz MC, Archer H, Harris RN, McKenzie VJ, Rabemananjara FCE, Rakotoarison A, et al. Host ecology rather than host phylogeny drives amphibian skin microbial community structure in the biodiversity hotspot of Madagascar. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker MH, Walke JB, Murrill L, Woodhams DC, Reinert LK, Rollins‐Smith LA, et al. Phylogenetic distribution of symbiotic bacteria from Panamanian amphibians that inhibit growth of the lethal fungal pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:1628–41. doi: 10.1111/mec.13135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flechas SV, Acosta-González A, Escobar LA, Kueneman JG, Sánchez-Quitian ZA, Parra-Giraldo CM, et al. Microbiota and skin defense peptides may facilitate coexistence of two sympatric Andean frog species with a lethal pathogen. ISME J. 2019;13:361–73. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunetti AE, Lyra ML, Melo WGP, Andrade LE, Palacios-Rodríguez P, Prado BM, et al. Symbiotic skin bacteria as a source for sex-specific scents in frogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:2124–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806834116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaelli PM, Theis KR, Williams JE, O’Connell LA, Foster JA, Eisthen HL. The skin microbiome facilitates adaptive tetrodotoxin production in poisonous newts. Elife. 2020;9:e53898. doi: 10.7554/eLife.53898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pukala TL, Bowie JH, Maselli VM, Musgrave IF, Tyler MJ. Host-defence peptides from the glandular secretions of amphibians: Structure and activity. Nat Prod Rep. 2006;23:368–93. doi: 10.1039/b512118n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bevins CL, Zasloff M. Peptides from frog skin. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:395–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodhams DC, Rollins-Smith LA, Reinert LK, Lam BA, Harris RN, Briggs CJ, et al. Probiotics modulate a novel amphibian skin defense peptide that is antifungal and facilitates growth of antifungal bacteria. Micro Ecol. 2020;79:192–202. doi: 10.1007/s00248-019-01385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mergaert P. Role of antimicrobial peptides in controlling symbiotic bacterial populations. Nat Prod Rep. 2018;35:336–56. doi: 10.1039/c7np00056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pontes MH, Smith KL, de Vooght L, van den Abbeele J, Dale C. Attenuation of the sensing capabilities of PhoQ in transition to obligate insect-bacterial association. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bosch TCG. Cnidarian-microbe interactions and the origin of innate immunity in metazoans. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2013;67:499–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster KR, Schluter J, Coyte KZ, Rakoff-Nahoum S. The evolution of the host microbiome as an ecosystem on a leash. Nature. 2017;548:43–51. doi: 10.1038/nature23292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joo H-S, Fu C-I, Otto M. Bacterial strategies of resistance to antimicrobial peptides. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150292. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacob-Dubuisson F, Mechaly A, Betton J-M, Antoine R. Structural insights into the signalling mechanisms of two-component systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16:585–93. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao R, Stock AM. Biological insights from structures of two-component proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:133–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Piddock LJV. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps? not just for resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:629–36. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeannot K, Bolard A, Plésiat P. Resistance to polymyxins in Gram-negative organisms. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:526–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández L, Jenssen H, Bains M, Wiegand I, Gooderham WJ, Hancock REW. The two-component system CprRS senses cationic peptides and triggers adaptive resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa independently of ParRS. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:6212–22. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01530-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong J, Jiang H, Hu J, Wang L, Liu R. Transcriptome analysis reveals the resistance mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to tachyplesin I. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:155. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S226687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunetti AE, Neto FC, Vera MC, Taboada C, Pavarini DP, Bauermeister A, et al. An integrative omics perspective for the analysis of chemical signals in ecological interactions. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:1574–91. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00368d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Nawrocki EP, Zaslavsky L, et al. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6614–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Coelho LP, Szklarczyk D, Jensen LJ, Von Mering C, et al. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:2115–22. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blin K, Shaw S, Steinke K, Villebro R, Ziemert N, Lee SY, et al. antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W81–W87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hesse C, Schulz F, Bull CT, Shaffer BT, Yan Q, Shapiro N, et al. Genome-based evolutionary history of Pseudomonas spp. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20:2142–59. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lechner M, Findeiß S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinforma. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–3. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meier-Kolthoff JP, Göker M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain C, Rodriguez-R LM, Phillippy AM, Konstantinidis KT, Aluru S. High-throughput ANI analysis of 90k prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Goloboff PA, Catalano SA. TNT version 1.5, including a full implementation of phylogenetic morphometrics. Cladistics. 2016;32:221–38. doi: 10.1111/cla.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garber M, Grabherr MG, Guttman M, Trapnell C. Computational methods for transcriptome annotation and quantification using RNA-seq. Nat Methods. 2011;8:469–77. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Min XJ, Butler G, Storms R, Tsang A. OrfPredictor: predicting protein-coding regions in EST-derived sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W677–W680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nacif-Marçal L, Pereira GR, Abranches MV, Costa NCS, Cardoso SA, Honda ER, et al. Identification and characterization of an antimicrobial peptide of Hypsiboas semilineatus (Spix, 1824) (Amphibia, Hylidae) Toxicon. 2015;99:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magalhães BS, Melo JAT, Leite JRSA, Silva LP, Prates MV, Vinecky F, et al. Post-secretory events alter the peptide content of the skin secretion of Hypsiboas raniceps. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1057–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunetti AE, Marani MM, Soldi RA, Mendonça JN, Faivovich J, Cabrera GM, et al. Cleavage of peptides from amphibian skin revealed by combining analysis of gland secretion and in situ MALDI imaging mass spectrometry. ACS Omega. 2018;3:5426–34. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b02029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Zundert GCP, Rodrigues J, Trellet M, Schmitz C, Kastritis PL, Karaca E, et al. The HADDOCK2. 2 web server: user-friendly integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:720–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung J, Bingman CA, Reyngold M, Hendrickson WA, Waldburger CD. Crystal structure of a functional dimer of the PhoQ sensor domain. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13762–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710592200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rebollar EA, Hughey MC, Medina D, Harris RN, Ibáñez R, Belden LK. Skin bacterial diversity of Panamanian frogs is associated with host susceptibility and presence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. ISME J. 2016;10:1682–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Bletz MC, Bunk B, Spröer C, Biwer P, Reiter S, Rabemananjara FCE, et al. Amphibian skin-associated Pigmentiphaga: genome sequence and occurrence across geography and hosts. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0223747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reimer LC, Vetcininova A, Carbasse JS, Söhngen C, Gleim D, Ebeling C, et al. Bac Dive in 2019: bacterial phenotypic data for high-throughput biodiversity analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D631–D636. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramette A, Frapolli M, Saux MF-L, Gruffaz C, Meyer JM, Défago G, et al. Pseudomonas protegens sp. nov., widespread plant-protecting bacteria producing the biocontrol compounds 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol and pyoluteorin. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2011;34:180–8. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flury P, Aellen N, Ruffner B, Péchy-Tarr M, Fataar S, Metla Z, et al. Insect pathogenicity in plant-beneficial pseudomonads: phylogenetic distribution and comparative genomics. ISME J. 2016;10:2527–42. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flury P, Vesga P, Dominguez-Ferreras A, Tinguely C, Ullrich CI, Kleespies RG, et al. Persistence of root-colonizing Pseudomonas protegens in herbivorous insects throughout different developmental stages and dispersal to new host plants. ISME J. 2019;13:860–72. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0317-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pupin M, Esmaeel Q, Flissi A, Dufresne Y, Jacques P, Leclère V. Norine: a powerful resource for novel nonribosomal peptide discovery. Synth Syst Biotechnol. 2016;1:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson DJ, Shi C, Teitelbaum AM, Gulick AM, Aldrich CC. Characterization of AusA: a dimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetase responsible for the production of aureusimine pyrazinones. Biochemistry. 2013;52:926–37. doi: 10.1021/bi301330q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ryona I, Leclerc S, Sacks GL. Correlation of 3-isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazine to 3-Isobutyl-2-hydroxypyrazine during maturation of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) and wine grapes (Vitis vinifera) J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:9723–30. doi: 10.1021/jf102072w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brucker RM, Baylor CM, Walters RL, Lauer A, Harris RN, Minbiole KPC. The identification of 2, 4-diacetylphloroglucinol as an antifungal metabolite produced by cutaneous bacteria of the salamander Plethodon cinereus. J Chem Ecol. 2008;34:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s10886-007-9352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.König E, Bininda-Emonds ORP, Shaw C. The diversity and evolution of anuran skin peptides. Peptides. 2015;63:96–117. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeaman MR, Yount NY. Mechanisms of antimicrobial peptide action and resistance. Pharm Rev. 2003;55:27–55. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kumar P, Kizhakkedathu JN, Straus SK. Antimicrobial peptides: diversity, mechanism of action and strategies to improve the activity and biocompatibility in vivo. Biomolecules. 2018;8:4. doi: 10.3390/biom8010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castro MS, Ferreira TCG, Cilli EM, Crusca E, Mendes-Giannini MJS, Sebben A, et al. Hylin a1, the first cytolytic peptide isolated from the arboreal South American frog Hypsiboas albopunctatus (‘spotted treefrog’) Peptides. 2009;30:291–6. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Resnick NM, Maloy WL, Guy HR, Zasloff M. A novel endopeptidase from Xenopus that recognizes α-helical secondary structure. Cell. 1991;66:541–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutu AD, Sgambati N, Strasbourger P, Brannon MK, Jacobs MA, Haugen E, et al. Polymyxin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phoQ mutants is dependent on additional two-component regulatory systems. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2204–15. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02353-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure. 2009;17:1282–94. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zschiedrich CP, Keidel V, Szurmant H. Molecular mechanisms of two-component signal transduction. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:3752–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shah N, Gaupp R, Moriyama H, Eskridge KM, Moriyama EN, Somerville GA. Reductive evolution and the loss of PDC/PAS domains from the genus Staphylococcus. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Bader MW, Sanowar S, Daley ME, Schneider AR, Cho U, Xu W, et al. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell. 2005;122:461–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chang C, Tesar C, Gu M, Babnigg G, Joachimiak A, Raj Pokkuluri P, et al. Extracytoplasmic PAS-like domains are common in signal transduction proteins. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1156–9. doi: 10.1128/JB.01508-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.