Abstract

Introduction

Chorea, a common clinical manifestation of Huntington’s disease (HD), involves sudden, involuntary movements that interfere with daily functioning and contribute to the morbidity of HD. Tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine are FDA-approved to treat chorea associated with HD. Compared to tetrabenazine, deutetrabenazine has a unique pharmacokinetic profile leading to more consistent systemic exposure, less frequent dosing, and a potentially more favorable safety/tolerability profile. Real-world adherence data for these medications are limited. Here, we evaluate real-world adherence patterns with the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors, tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine, among patients diagnosed with HD.

Methods

Insurance claims data from the Symphony Health Solutions Integrated Dataverse (05/2017–05/2019) were retrospectively analyzed for patients diagnosed with HD (ICD-10-CM code G10). Patients were categorized into cohorts based on treatment. Outcomes included adherence, which was measured by proportion of days covered (PDC), adherence rate (PDC > 80%), and discontinuation rates during the 6-month follow-up period (after a 30-day dose stabilization period).

Results

Patient demographic characteristics between the deutetrabenazine (N = 281) and tetrabenazine (N = 101) cohorts were comparable at baseline. Mean ± SD PDC was significantly higher in the deutetrabenazine versus tetrabenazine cohort (78.5% ± 26.7% vs. 69.3% ± 31.4%; P < 0.01). Similarly, a higher adherence rate was observed in the deutetrabenazine versus tetrabenazine cohort, though the difference was not statistically significant (64.1% vs. 55.4%; P = 0.1518). Discontinuation rates were significantly lower in the deutetrabenazine versus tetrabenazine cohort during the 6-month follow-up period (1 month, 3.5% vs. 9.2%; 3 months, 14.7% vs. 23.3%; 6 months, 25.4% vs. 37.2%; P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Results from this real-world analysis indicate that patients treated with deutetrabenazine are more adherent to treatment and have lower discontinuation rates compared with patients in the tetrabenazine cohort. However, a potential limitation is overestimated adherence, as claims for prescription fills may not capture actual use. Additional research is warranted to explore the differences in adherence patterns between treatments, which may inform treatment decision-making.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-021-00309-5.

Keywords: Adherence patterns, Deutetrabenazine, Huntington’s disease, Tetrabenazine, Treatment discontinuation

Key Summary Points

| The vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat chorea associated with Huntington’s disease (HD). |

| Real-world adherence data for VMAT2 inhibitors to treat HD chorea are limited. |

| This analysis of a large database of United States claims showed that significantly higher proportions of patients in the deutetrabenazine versus the tetrabenazine cohort were adherent to treatment, as measured by the proportion of days covered. |

| In addition, discontinuation rates were lower among patients in the deutetrabenazine compared with the tetrabenazine cohort. |

Introduction

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a hereditary, progressive, and ultimately fatal neurodegenerative disease characterized by disruptions in motor function, emotional–behavioral control, and cognitive capacity. It is the most common hereditary neurodegenerative disorder globally, with a worldwide prevalence of 2.71 per 100,000 and an annual incidence of 0.38 per 100,000 in 2012 [1]. Chorea is a hallmark of HD, affecting ~ 90% of patients. Chorea associated with HD involves sudden, involuntary movement that can affect any muscle and can interfere with daily functioning and increase the risk of injury [2]. Thus, HD can significantly impact quality of life, with patients often experiencing loss of employment, ability to raise a family, and decision-making ability due to their symptoms [3, 4].

Currently, there is no cure for HD, and available therapies are focused on symptom management and supportive care to optimize quality of life [5]. HD patients with moderate-to-severe chorea may benefit from treatment with pharmacologic therapy with dopamine-depleting agents that inhibit presynaptic vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 (VMAT2), such as tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine. The VMAT2 inhibitor tetrabenazine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 [6], but has been used for decades in other countries to treat HD chorea and other hyperkinetic movement disorders. Deutetrabenazine is a novel, selective VMAT2 inhibitor that was approved by the FDA for the treatment of chorea associated with HD and tardive dyskinesia in 2017 [7]. Deutetrabenazine is a deuterated form of the VMAT2 inhibitor tetrabenazine. Deuteration of the molecule results in a unique pharmacokinetic profile that leads to more consistent systemic exposure, less frequent dosing, and a potentially more favorable safety and tolerability profile compared with tetrabenazine [8–15]. There have not been any head-to-head trials to directly compare the efficacy and safety of tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine; however, an indirect comparison of clinical trial data reported that deutetrabenazine had a significantly better tolerability profile than tetrabenazine in patients with HD [16]. Real-world adherence data for these medications are also limited. This study evaluated real-world adherence patterns with tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine among adult patients diagnosed with HD.

Methods

Data Source

Data were extracted from the Symphony Health Solutions’ (SHS) Integrated Dataverse (May 2017–May 2019), an insurance claims database that links health-care data for approximately 280 million people in the United States from 3 basic sources: pharmacy point-of-service sales, switch/network (clearing house) transactions, and additional direct prescriptions, medical, and hospital claims data feeds [17]. The database reflects pharmacy claims in all stages of processing, submitted medical claims, and includes physician National Provider Identifier numbers for the prescribing physician. In addition, the database includes various payment types (e.g., cash, Medicaid, Medicare, and commercial insurance payments), and is representative of patients in the United States in terms of age and sex. This database was well suited for this study, as it captures approximately 90% of all prescription claims filled at US retail pharmacies, representing over 75% of the United States population (i.e., more than 260 million people) annually, and includes data from specialty pharmacies which dispense tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine. The data were delivered in a de-identified format in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and its implementing regulations (HIPAA).

Study Design

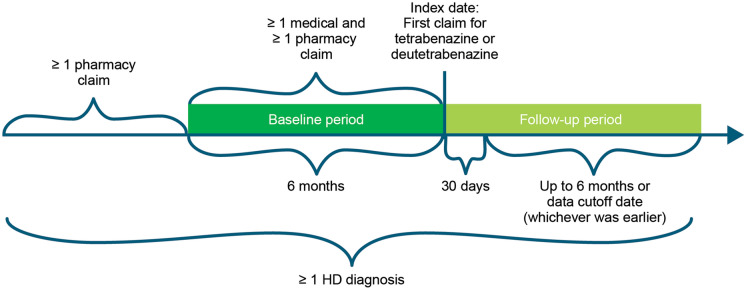

This retrospective study described the real-world patterns of adherence to deutetrabenazine or tetrabenazine among patients with HD (Fig. 1). Patients were categorized into 2 different cohorts based on index treatment (i.e., tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine). The index date was defined as the date of the first claim for either tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine. The baseline period was defined as the 6-month period before the index date, while the follow-up period was defined as 30 days after the index date up to 6 months (or end of data, whichever was first). The initial 30 days, including the index date, were considered as a period of dose stabilization.

Fig. 1.

Study design. HD Huntington’s disease

Sample Selection

Eligible patients were those with ≥ 1 claim with a diagnosis of HD (i.e., International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] code of G10) and ≥ 1 prescription claim for tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine between May 2017 and May 2019 who were aged between 18 and 65 years. Patients with ≥ 1 pharmacy claim prior to the baseline period were included as a washout to capture the first observable claim of tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine. From this, patients with continuous clinical activity (≥ 1 medical and ≥ 1 pharmacy claim) during the baseline period were included. Finally, patients were also included who (1) did not discontinue index treatment within 30 days from the index date, (2) had an index date which was ≥ 30 days prior to the data cutoff date, (3) had ≥ 30 total days of supply of index treatment, and (4) had ≥ 1-day supply of index treatment during the time period from 30 days after the index date and up to 6 months later or the data cutoff date, whichever was earlier.

Outcomes and Analyses

Patient characteristics were described during the baseline period. Outcomes of this analysis included adherence as measured by the proportion of days covered (PDC) for the index treatment; the adherence rate, which was defined as the proportion of patients with PDC > 80% during the follow-up period; and the proportion of patients who discontinued index treatment during the follow-up period, as determined by Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Patient characteristics during the baseline period were compared overall in each cohort and separately for each cohort according to adherence status [i.e., adherent (PDC > 80%) and nonadherent (PDC ≤ 80%)]. Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continuous variables, and counts and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables between the 2 cohorts.

PDC distributions were described using mean (SD), adherence rates were described using counts and percentages, and Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to characterize the proportions of patients who discontinued their index treatment during the follow-up period. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare the distribution of PDC, and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare adherence rates between the 2 cohorts. Statistical comparisons of time to discontinuation between the 2 cohorts were conducted using a log-rank test.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Our study is based on de-identified data collected from the SHS Integrated Dataverse, which were used with permission. Our study does not contain any experimental data with human or animal participants. This analysis was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight and we did not obtain informed consent, as the data was delivered in a de-identified format in compliance with the HIPAA of 1996 and its implementing regulations.

Results

Patient Characteristics in the Overall Study

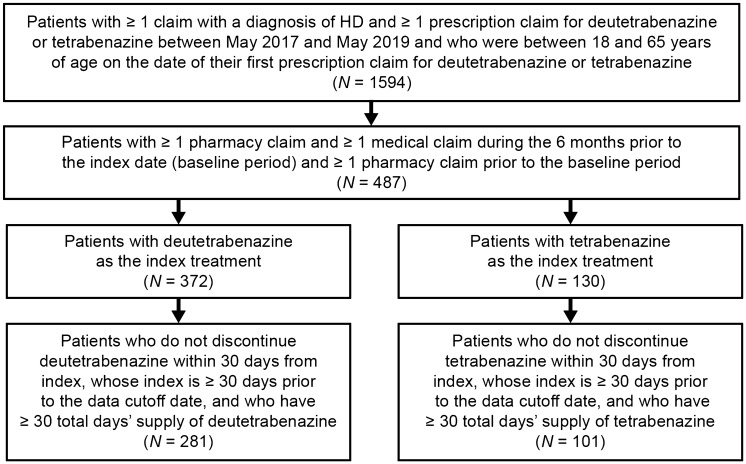

In total, 281 patients met the selection criteria for inclusion into the deutetrabenazine cohort and 101 patients met the selection criteria for inclusion into the tetrabenazine cohort (Fig. 2). Patients in the 2 cohorts had comparable demographic characteristics at baseline (Table 1). Most patients were between 38 and 65 years of age, and more than half of the patients in both cohorts were female. Overall, there were differences in the type of health-care coverage between cohorts (P < 0.001), with more patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort versus the tetrabenazine cohort having commercial coverage, and fewer patients having Medicaid coverage. Additionally, higher proportions of patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort initiated the index treatment in later years compared with patients in the tetrabenazine cohort (P < 0.001). The mean (SD) time from index date to the last observed medical/pharmacy activity (i.e., the duration of follow-up) was shorter in the deutetrabenazine cohort versus the tetrabenazine cohort [209.9 (142.0) days vs. 289.1 (155.7) days; P < 0.001]. Among patients who were diagnosed with HD before their index date, the mean (SD) time between the first diagnosis of HD and index date was significantly longer in the deutetrabenazine versus the tetrabenazine cohort [353.4 days (214.3) days vs. 257.6 (165.2) days; P < 0.001].

Fig. 2.

Sample selection. HD Huntington’s disease, ICD-10-CM International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification. There were 11 patients with both deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine claims; 10 patients had their first tetrabenazine claim before their first deutetrabenazine claim, while 1 patient had their first deutetrabenazine claim before their first tetrabenazine claim

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Deutetrabenazine cohort (N = 281) | Tetrabenazine cohort (N = 101) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age category (years), n (%) | |||

| 18–27 | 10 (3.6%) | 9 (8.9%) | 0.1024 |

| 28–37 | 20 (7.1%) | 11 (10.9%) | |

| 38–47 | 61 (21.7%) | 22 (21.8%) | |

| 48–57 | 87 (31.0%) | 22 (21.8%) | |

| 58–65 | 103 (36.7%) | 37 (36.6%) | |

| Male, n (%) | 110 (39.1%) | 44 (43.6%) | 0.4785 |

| Health plan typea, n (%) | |||

| Medicare | 113 (40.2%) | 37 (36.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Commercial | 53 (18.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Medicaid | 50 (17.8%) | 36 (35.6%) | |

| Otherb | 19 (6.8%) | 13 (12.9%) | |

| Unspecified | 46 (16.4%) | 15 (14.9%) | |

| Index year, n (%) | |||

| 2017 | 3 (1.1%) | 12 (11.9%) | < 0.001 |

| 2018 | 160 (56.9%) | 69 (68.3%) | |

| 2019 | 118 (42.0%) | 20 (19.8%) | |

| Observed disease durationc | |||

| Patients assessed, n (%) | 254 (90.4%) | 79 (78.2%) | < 0.01 |

| Observed disease duration, mean ± SD (days) | 353.4 ± 214.3 | 257.6 ± 165.2 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of follow-up, mean ± SD | |||

| Time from index date to end of datad (days) | 229.0 ± 146.1 | 313.4 ± 156.9 | < 0.001 |

| Time from index date to last observed medical/pharmacy activity (days) | 209.9 ± 142.0 | 289.1 ± 155.7 | < 0.001 |

| CCI score, mean ± SD | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.6716 |

| Selected comorbidities in the CCI, n (%) | |||

| Dementia | 23 (8.2%) | 9 (8.9%) | 0.8352 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 19 (6.8%) | 7 (6.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Diabetes without chronic complication | 12 (4.3%) | 7 (6.9%) | 0.2933 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 7 (2.5%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1.0000 |

| Any malignancy, including leukemia and lymphoma, except for malignant neoplasm of skin | 7 (2.5%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.6867 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (3.0%) | 0.3871 |

| Mild liver disease | 3 (1.1%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.6110 |

| Psychiatric comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Depressive disorders | 60 (21.4%) | 24 (23.8%) | 0.6745 |

| Anxiety disorders | 53 (18.9%) | 15 (14.9%) | 0.4486 |

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 31 (11.0%) | 18 (17.8%) | 0.0851 |

| Bipolar and related disorders | 23 (8.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Trauma- and stressor-related disorders | 10 (3.6%) | 3 (3.0%) | 1.0000 |

| ADD/ADHD | 5 (1.8%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1.0000 |

| Other psychoses | 4 (1.4%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0.2159 |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.2858 |

| Conduct disorder | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.0694 |

| Nonpsychiatric comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 42 (14.9%) | 15 (14.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 42 (14.9%) | 17 (16.8%) | 0.6337 |

| Dysphagia | 42 (14.9%) | 5 (5.0%) | < 0.01 |

| Falls | 37 (13.2%) | 11 (10.9%) | 0.6044 |

| Sleep-awake disorders | 29 (10.3%) | 14 (13.9%) | 0.3599 |

| Sleep disturbance | 18 (6.4%) | 8 (7.9%) | 0.6460 |

| Osteoarthritis | 19 (6.8%) | 6 (5.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Smoking history | 19 (6.8%) | 10 (9.9%) | 0.3800 |

| Abnormal weight loss | 14 (5.0%) | 4 (4.0%) | 0.7905 |

| Dystonia | 10 (3.6%) | 10 (9.9%) | < 0.05 |

| Tardive dyskinesia | 5 (1.8%) | 6 (5.9%) | 0.0745 |

| Tachycardia | 2 (0.7%) | 4 (4.0%) | < 0.05 |

| Treatment history, n (%) | |||

| Antidepressants | 185 (65.8%) | 61 (60.4%) | 0.3348 |

| Anticonvulsants | 113 (40.2%) | 37 (36.6%) | 0.5543 |

| Anti-anxiety medications | 64 (22.8%) | 26 (25.7%) | 0.5851 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 53 (18.9%) | 25 (24.8%) | 0.2492 |

| Anticholinergics | 44 (15.7%) | 9 (8.9%) | 0.0966 |

| Antihypertensives | 39 (13.9%) | 11 (10.9%) | 0.4960 |

| Cognition-enhancing medication | 23 (8.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Anti-diabetic drugs | 15 (5.3%) | 8 (7.9%) | 0.3384 |

| Sedatives and hypnotics | 14 (5.0%) | 7 (6.9%) | 0.4524 |

| Stimulants/ADHD medications | 14 (5.0%) | 5 (5.0%) | 1.0000 |

| First-generation or second-generation antipsychotics | 105 (37.4%) | 38 (37.6%) | 1.0000 |

| First-generation antipsychotics | 23 (8.2%) | 8 (7.9%) | 1.0000 |

| Haloperidol | 22 (7.8%) | 5 (5.0%) | 0.4967 |

| Second-generation antipsychotics | 85 (30.2%) | 35 (34.7%) | 0.4537 |

| Risperidone | 29 (10.3%) | 15 (14.9%) | 0.2747 |

| Quetiapine | 29 (10.3%) | 11 (10.9%) | 0.8514 |

| Olanzapine | 19 (6.8%) | 8 (7.9%) | 0.6572 |

| All-cause HCRU, n (%) | |||

| Any inpatient visit | 24 (8.5%) | 10 (9.9%) | 0.6859 |

| Any outpatient visite | 250 (89.0%) | 81 (80.2%) | < 0.05 |

| Any emergency visit | 49 (17.4%) | 24 (23.8%) | 0.1846 |

| Any other visit | 110 (39.1%) | 53 (52.5%) | < 0.05 |

| Any unknown visit | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.5689 |

All demographics, CCI, and psychiatric comorbidities with prevalence higher than 2% in any cohort; any non-psychiatric comorbidities and treatments with prevalence higher than 5% in any cohort; and all HCRU were presented in this table

ADHD attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CCI Charlson comorbidity index, ICD-10-CM International Classification of Diseases; 10th Revision, Clinical Modification, HD Huntington’s disease, HCRU health-care resource utilization, SD standard deviation

aHealth plan type is associated with a patient’s index claim

bOther health plan types include cash, employer group, third-party administrator, processors and workers’ compensation

cObserved disease duration (time between first diagnosis and index date) was assessed among patients who were diagnosed with HD before their index date

dEnd of data, May 31, 2019

eOutpatient visits include medical office, hospital outpatient, and clinic visits. Other visits include home health, hospital outpatient pharmacy, intermediate care facility, laboratory, long-term care facility, and other facilities

No notable differences in comorbidity and treatment history profiles were observed between cohorts except that a higher proportion of patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort versus the tetrabenazine cohort had dysphagia at baseline (14.9% vs. 5.0%; P < 0.01) and a lower proportion had dystonia (3.6% vs. 9.9%; P < 0.05) and tachycardia (0.7% vs. 4.0%; P < 0.05; Table 1). The most common concomitant treatments at baseline were antidepressants (> 60%), anticonvulsants (37–40%), and antipsychotics (~ 37%) in both cohorts.

Patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort were significantly more likely to have any baseline all-cause outpatient visits (P < 0.05), but less likely to have any all-cause other visits (e.g., home health, hospital outpatient pharmacy, intermediate care facility, laboratory, long-term care facility, and other facilities) compared to the tetrabenazine cohort (P < 0.05). Other all-cause health-care resource utilization (HCRU) was not significantly different between the 2 cohorts.

Adherence Analyses

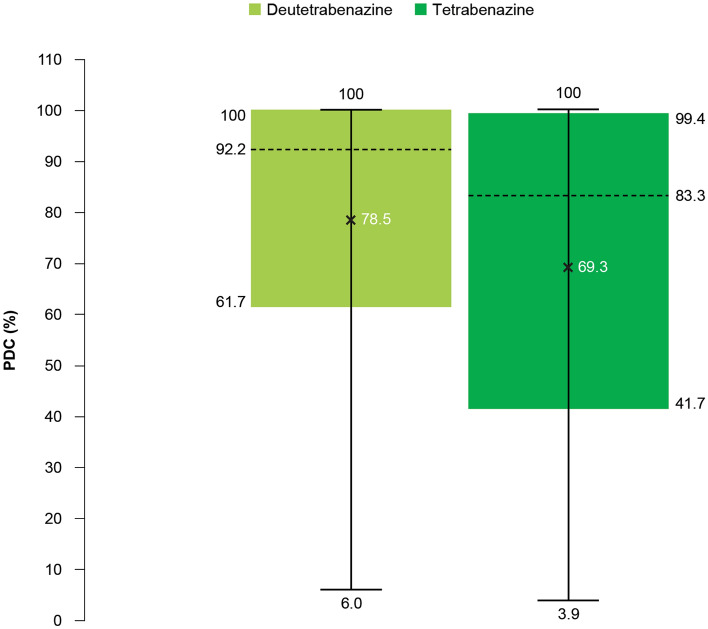

Adherence as measured by PDC was significantly higher in the deutetrabenazine cohort versus the tetrabenazine cohort [mean (SD): 78.5% (26.7) vs. 69.3% (31.4); P < 0.01; Fig. 3]. The deutetrabenazine cohort showed a higher adherence rate (i.e., the proportion of patients with PDC > 80%) compared to the tetrabenazine cohort, though the difference was not statistically significant (64.1% vs. 55.4%; P = 0.1518). In addition, 75% of patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort had adherence higher than or equal to 61.7%. In contrast, the first quartile of adherence in the tetrabenazine cohort was 41.7%.

Fig. 3.

Adherence as measured by PDC. PDC proportion of days covered. Mean PDC values are denoted by ×, with a range of 6–100% for the deutetrabenazine cohort and 3.9–99.4% for the tetrabenazine cohort. Horizontal lines within each box denote the median values and the limits of the box represent the interquartile range (Q1–Q3)

Patient Characteristics in Subgroups by Adherence Status

In an analysis of patient characteristics at baseline for adherent and nonadherent patients in each cohort, there were no significant differences in age and sex distributions or comorbidity and treatment history profiles (Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Material). In the deutetrabenazine cohort, there was a significant difference in health-care insurance type between adherent and nonadherent patients (P < 0.01), with higher proportions of adherent patients using Medicare and lower proportions using commercial insurance compared with nonadherent patients. Additionally, adherent patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort initiated the index treatment later, had longer disease duration, and shorter duration of follow-up compared with nonadherent patients (all P < 0.01). A significantly higher proportion of adherent versus nonadherent patients had hyperlipidemia (P < 0.05) and used antidepressants, anticonvulsants, anti-anxiety medications, and lipid-lowering agents (all P < 0.01).

In the tetrabenazine cohort, the duration of follow-up was shorter among adherent patients compared with nonadherent patients (P < 0.05). In addition, adherent patients in the tetrabenazine cohort had significantly lower use of sedatives and hypnotics and stimulants/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications compared with nonadherent patients (Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Material).

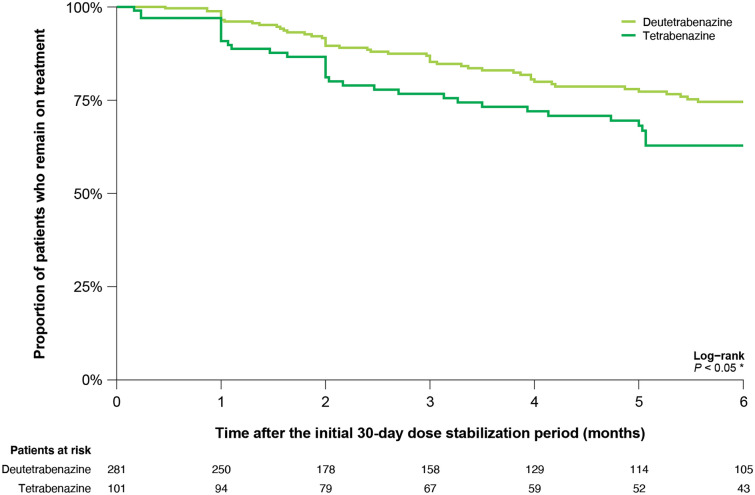

Discontinuation Rates

The proportion of patients who discontinued their index treatment during the 6-month follow-up period starting from 30 days after the index date was significantly lower in the deutetrabenazine cohort versus the tetrabenazine cohort (1 month, 3.5% vs. 9.2%; 3 months, 14.7% vs. 23.3%; 6 months, 25.4% vs. 37.2%; P < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier curve for time to discontinuation of deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine

Discussion

There is a lack of real-world data characterizing the adherence patterns of deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine in patients with HD. Results from this real-world analysis using data from a large United States claims database has shown that patients with HD in the deutetrabenazine cohort had greater adherence and lower discontinuation rates compared to patients in the tetrabenazine cohort.

There are several possible explanations for these findings. The higher adherence observed among patients receiving deutetrabenazine compared to tetrabenazine may be reflective of potential differences in tolerability profiles that have been reported in previous studies [8–14]. For example, an indirect treatment comparison study reported that deutetrabenazine had a significantly better tolerability profile than tetrabenazine both before and after adjusting for patient characteristics [16]. In addition, deutetrabenazine showed a superior pharmacokinetic profile compared with tetrabenazine in healthy volunteers, providing significant benefits to patients and potentially improving adherence [15]. Furthermore, the less frequent dosing of deutetrabenazine (twice daily) versus tetrabenazine (up to 3 times daily) could contribute to better adherence, as patients taking tetrabenazine may find it challenging to take the midday dose when their caregivers may be working or otherwise unavailable. In addition, more patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort had dysphagia at baseline, which may reflect that these patients are more inclined to use a less frequent dosing regimen, thereby increasing the likelihood for them to be adherent to treatment.

Patient adherence to deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine may also be affected by symptom severity, concomitant treatment use (e.g., antidepressants and antipsychotics), and comorbidities (e.g., depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disease). We found that patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort had a significantly longer time between HD diagnosis and index treatment date, which could suggest that these patients were further along in their disease progression, and thus experiencing more severe symptoms. Adherence may also be influenced, in part, by physician familiarity with the drug after it has been approved. For example, a higher proportion of the deutetrabenazine cohort initiated treatment in later years (i.e., 2018 and 2019) after FDA approval in 2017. Interestingly, a higher proportion of adherent patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort initiated treatment in 2019. We speculate that physician familiarity with titration and prescribing practices contributes to this relationship. In addition, patients may have responded well to additional guidance and information from their physicians, as previous research has suggested patients may have greater adherence when treatment plans are clearly outlined [18]. This could have important impacts on the health-care system, as better adherence may in turn lead to decreased clinical and economic burden (e.g., outcomes and HCRU).

It would also be beneficial to explore how health-care access disparities between Medicare and Medicaid populations and eligibility for financial support programs contributed to adherence in this study. Recent research efforts have begun to address some of the social determinants of health among Medicare and Medicaid recipients in order to improve health-care access and outcomes for these patients [19]. Importantly, access to specific types of health-care providers and treatments may vary depending on patients’ insurance coverage and health history. In this study, patients in the tetrabenazine cohort were more likely to have Medicaid than patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort; however, it is unknown if disparities measured in this study are entirely related to patients’ insurance coverage, and further research on this topic is warranted. The distribution of health insurance plans associated with a patient’s index treatment was significantly different between cohorts in the overall population and for adherent versus nonadherent patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort. Of note, no index claims for the tetrabenazine cohort were noted among those with commercial insurance. However, commercial insurance was more prevalent among nonadherent patients in the deutetrabenazine cohort, which suggests that differences in payer type may not fully explain the positive adherence trend with deutetrabenazine [20, 21]. Further research is needed to understand how the adherence to deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine is correlated with the observed treatment patterns, and how patient characteristics at baseline might affect adherence. In addition, it would also be interesting to further investigate reasons for nonadherence that cannot be determined with certainty from retrospective claims data.

Overall, this analysis is strengthened by the use of the SHS Integrated Dataverse, which includes recent health-care data representing ~ 90% of all United States retail claims, and is representative of the United States general population in terms of age and sex. Claims databases provide information on patterns of care and clinical practice in a real-world setting.

A few potential limitations to acknowledge are that HD and comorbidities were identified using ICD-10-CM codes, which are used for administrative billing purposes. As a result, these conditions may be underestimated due to coding completeness. The SHS Integrated Dataverse does not include eligibility records, and continuous health plan enrollment was inferred using patients’ claims activity. The SHS claims database is based on a large convenience sample (i.e., the sample is not random); therefore, the results may be confounded by unmeasured characteristics. The study period began in May 2017 to capture data following the FDA approval of deutetrabenazine for HD chorea treatment in April 2017; therefore, follow-up data were limited for the analysis. Due to the nature of claims data, specific reasons for treatment discontinuation in these patients were unknown. Lastly, adherence may have been overestimated, as claims for prescription fills may not capture actual use.

Conclusions

This real-world analysis provides evidence that patients with HD taking deutetrabenazine were more adherent to treatment and had lower discontinuation rates compared with patients taking tetrabenazine. The higher adherence observed among patients receiving deutetrabenazine compared with tetrabenazine may reflect differences in dosing regimen and tolerability profiles. Additional research is warranted to explain the observed differences in adherence patterns, and to identify potential predictors of adherence between the deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine cohorts. Health-care providers can, however, leverage the findings from this study to better understand these treatment options and aid patient populations at the greatest risk for negative treatment utilization outcomes.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Tel Aviv, Israel. The sponsor also supported the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Editorial Assistance

We thank Alaina Mitsch, PhD (Cello Health Communications/MedErgy with funding from Teva Pharmaceuticals) for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: All authors; Study design: Rajeev Ayyagari, Viviana Garcia-Horton, Su Zhang, Sam Leo; Data analysis: Rajeev Ayyagari, Viviana Garcia-Horton, and Su Zhang. Data interpretation: All authors. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Prior Presentation

These data were previously presented, in part, in abstract form at the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) 2021 Virtual National Meeting; April 12–16, 2021.

Disclosures

Daniel O. Claassen reports receiving research support from the Griffin Foundation, Huntington’s Disease Society of America, Michael J. Fox Foundation, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and National Institute on Aging; receiving pharmaceutical grant support from AbbVie, Acadia, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cerecor, Eli Lilly, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Teva Neuroscience, Vaccinex, and Wave Life Sciences; and serving as a consultant or on an advisory board for Acadia, Adamas, Alterity, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Teva Neuroscience, and Wave Life Sciences. Rajeev Ayyagari, Viviana Garcia-Horton, and Su Zhang are employees of Analysis Group, Inc. Jessica Alexander and Sam Leo are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Our study is based on de-identified data collected from the Symphony Health Solutions Integrated Dataverse, which were used with permission. Our study does not contain any experimental data with human or animal participants. This analysis was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight and we did not obtain informed consent, as the data was delivered in a de-identified format in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and its implementing regulations (HIPAA).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the data are available from Symphony Health Solutions, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Data at the aggregate level are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Symphony Health Solutions.

References

- 1.Pringsheim T, Wiltshire K, Day L, Dykeman J, Steeves T, Jette N. The incidence and prevalence of Huntington’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2012;27:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/mds.25075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner A, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P. Genetics and neuropathology of Huntington’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:325–372. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381328-2.00014-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgunder JM, Guttman M, Perlman S, Goodman N, van Kammen DP, Goodman L. An international survey-based algorithm for the pharmacologic treatment of chorea in Huntington's disease. PLoS Curr. 2011;3:RRN1260. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorley EM, Iyer RG, Wicks P, et al. Understanding how chorea affects health-related quality of life in Huntington disease: an online survey of patients and caregivers in the United States. Patient. 2018;11:547–559. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar A, Kumar Singh S, Kumar V, Kumar D, Agarwal S, Rana MK. Huntington’s disease: an update of therapeutic strategies. Gene. 2015;556:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.XENAZINE® (tetrabenazine) [package insert]. Fontaine-les-Dijon: Recipharm Fontaine SAS; 2017.

- 7.Austedo® (deutetrabenazine) tablets [prescribing information]. Parsippany: Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc.; 2020.

- 8.Shao L, Hewitt MC. The kinetic isotope effect in the search for deuterated drugs. Drug News Perspect. 2010;23:398–404. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2010.23.6.1426638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmins GS. Deuterated drugs: where are we now? Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;24:1067–1075. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.943184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein PD, Klein ER. Stable isotopes: origins and safety. J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;26:378–382. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1986.tb03544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jankovic J, Jimenez-Shahed J, Budman C, et al. Deutetrabenazine in tics associated with Tourette syndrome. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2016;6:422. doi: 10.5334/tohm.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stahl SM. Comparing pharmacologic mechanism of action for the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitors valbenazine and deutetrabenazine in treating tardive dyskinesia: does one have advantages over the other? CNS Spectr. 2018;23:239–247. doi: 10.1017/S1092852918001219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dean M, Sung VW. Review of deutetrabenazine: a novel treatment for chorea associated with Huntington’s disease. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2018;12:313–319. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S138828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings MA, Proctor GJ, Stahl SM. Deuterium tetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2018;11:214–220. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.CUPR.010318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneider F, Bradbury M, Baillie TA, et al. Pharmacokinetic and metabolic profile of deutetrabenazine (TEV-50717) compared with tetrabenazine in healthy volunteers. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:707–717. doi: 10.1111/cts.12754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claassen DO, Carroll B, De Boer LM, et al. Indirect tolerability comparison of deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine for Huntington disease. J Clin Mov Disord. 2017;4:3. doi: 10.1186/s40734-017-0051-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Symphony Health. IDV® fact sheet 2020. https://symphonyhealth.prahs.com/insights/idv-fact-sheet. Accessed August 27, 2021.

- 18.Roebuck MC, Liberman JN, Gemmill-Toyama M, Brennan TA. Medication adherence leads to lower health care use and costs despite increased drug spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:91–99. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman C, Paradise J. Health insurance and access to health care in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:149–160. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aetna. Covered and non-covered drugs: drugs not covered—and their covered alternatives. 2020 advanced control plan—Aetna formulary exclusions drug list; 2020. http://www.aetna.com/individuals-families/document-library/jan20-exclusion-drug-list.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2021.

- 21.Express Scripts. 2019 Express Scripts national preferred formulary for Missouri consolidated health care plan; 2019. https://www.express-scripts.com/art/pdf/MH3A-formulary.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the data are available from Symphony Health Solutions, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study. Data at the aggregate level are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Symphony Health Solutions.