Abstract

Purpose:

To investigate the association between corneal densitometry (CD) values from Scheimpflug tomography imaging, severity of guttae, and visual acuity (VA) in eyes with Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy (FECD).

Design:

Retrospective, cross-sectional study.

Subjects:

Patients with FECD examined at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from January 2015 to September 2019.

Methods:

We extracted CD values at central annuli of 0–2, 2–6, 6–10 and 10–12 mm from Scheimpflug tomography images. We investigated the association of corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) with CD values, severity of guttae, central corneal thickness (CCT), cataract grade, refractive error, corneal edema grade, age, and gender using multivariate generalized estimating equation regression models.

Main Outcome Measure(s):

CDVA.

Results:

192 eyes from 110 patients were included in this study. Increase in central CD values at the 0–2 mm zone (P<0.001), severity of guttae (P=0.046), age (P<0.001), cataract grade (P<0.001), corneal edema grade (P<0.001), and type of refractive error (P=0.008) were significantly associated with decreased CDVA. CCT, gender and the peripheral CD values (2–6, 6–10 and 10–12 mm) were not significantly associated with CDVA (p>0.05) in the final multivariate regression model.

Conclusions:

Our study demonstrates that central CD values at 0–2 mm and severity of guttae are each associated with decreased CDVA in FECD. These findings carry implications for patients with FECD considering surgical intervention for phacoemulsification alone, Descemet stripping only (DSO) or endothelial cell transplantation, and provide a multifactorial perspective on vision loss in FECD.

Keywords: Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy, Corneal Densitometry, Guttae, Scheimpflug tomography

INTRODUCTION

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is the most common condition leading to corneal transplantation in the United States and worldwide.1 The disease is characterized by an accelerated loss of endothelial cells with thickening of the Descemet membrane, formation of guttae, corneal edema, increased corneal thickness and stromal haze, all of which contribute to decreased corneal clarity and visual loss.

Corneal tomography using Scheimpflug imaging is a useful and commonly performed test in the clinical setting, which allows for quantitative assessment of corneal health and clarity by capturing corneal densitometry (CD) values.2,3 At this time, there are no large-scale studies correlating the findings of CD to the severity of FECD, level of guttae, and visual function.

In addition, with the advent of posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK), endothelial keratoplasty (EK), and Descemet’s Stripping Only (DSO), the treatment modalities for FECD have been rapidly evolving4–6 and removal of guttae have been advocated at earlier stages in the disease process with FECD. There is a need for understanding whether guttae alone, independent of corneal thickness or stromal haze, contribute to a decrease in visual function.

In this study, we explore the association of CD with visual acuity in FECD, and the relationship of guttae with decreased visual acuity after adjusting for CD values and edema. Together, these factors play an important role in determining the management and treatment guidelines for FECD.

METHODS

This retrospective cross-sectional study was performed in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. University of Miami Miller School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained. We included patients coming through Bascom Palmer Eye Institute January 2015 to September 2019, with FECD diagnosed by two corneal specialists (E.K., T.O’B.). Cases with prior keratoplasty or glaucoma surgery, complications related to cataract surgery, corneal trauma, infectious or inflammatory keratitis, incomplete records, and absence of Scheimpflug corneal tomography imaging were excluded. The Pentacam® HR (Oculus, Lynnwood, WA) was used to capture the Scheimpflug corneal tomographic images. A total of 192 eyes from 110 patient charts were evaluated in this study.

Chart Review and Data Collection

All charts were evaluated for demographic and clinical variables, including gender, age, guttae, refractive error, cataract grade, corneal edema grade, central corneal thickness (CCT) by ultrasound pachymetry, CD, and corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA). The lens status was documented at each visit. Nuclear sclerosis was assessed by slit lamp biomicroscopic examination and graded based on the Wisconsin Cataract Grading System.7

The corneal parameters were documented by two corneal specialists (E.K., T.O’B.) using slit lamp biomicroscopy. The corneal edema was graded using a descriptive 1–4 scale with 0.5 increments. A grade of 0 was given for clear corneas. A grade of 1 was given for corneas with mild stromal edema, a grade of 2 for corneas with mild Descemet folds and/or diffuse stroma edema, a grade of 3 for corneas with moderate Descemet folds and haze, and/or moderate-to-high stromal thickening, with epithelial changes limited to focal microcystic edema or bullae. Grade 4 represented diffuse bullous keratopathy. The severity of corneal guttae was determined according to the Krachmer scale.8 In this scale, the severity of guttae are defined by the distribution of guttae on the cornea, including 12 or more central scattered guttae (1+), up to 2 mm of central confluent guttae (2+), 2–5 mm diameter of central guttae (3+), and more than 5 mm diameter of confluent guttae (4+). In the original Krachmer scale, visible edema qualified as 5+, but in this study, edema was included as a separate variable and the scale was limited to the severity of guttae. Central guttae, if less than 12 in value, were described as 0.5 on the scale.

CD values, at central annuli of 0–2, 2–6, 6–10, and 10–12 mm, were collected from the Scheimpflug cornea tomography images.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics for categorical and ordinal variables include counts and percentages, for ordinal variables include medians and interquartile ranges, and for continuous variables include means and standard deviations. The primary outcome variable for this study was CDVA, which was measured by Snellen chart and subsequently converted to logMAR for statistical analysis. Univariate associations between CDVA and CD values, guttae severity, CCT, cataract grade, corneal edema grade, and age were assessed with Spearman correlations. Univariate associations between gender and (1) continuous variables (e.g. CDVA) were assessed with independent-samples t-tests; (2) ordinal variables (cataract grade, corneal edema grade, and guttae severity) were assessed with Jonckheere-Terpstra and Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon tests; and (3) categorical variables (e.g. type of refractive error) were assessed with chi-square tests. Multiple regression models were built with CDVA as the outcome (dependent) variable and the aforementioned variables as possible explanatory (independent) variables to determine independent significant predictors of CDVA. These models were built using generalized estimating equations to account for the correlation between both eyes of some subjects. The best, final model was determined by utilizing a backward selection approach. Initially, all possible explanatory variables were included in the model, and at each subsequent step, the variable with the highest p-value was removed until all variables in the model were statistically significant. Cataract grade, corneal edema grade, and severity of guttae were treated in the multivariate model as continuous variables. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are found in r. Corneal edema grade was the only variable that differed significantly by gender (P=0.024), with the value of 0 diagnosed more frequently in females (85.4%) than males (72.6%) (Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in logMAR CDVA by gender (males: mean = 0.182, standard deviation = 0.186; females: mean = 0.176, standard deviation = 0.202; P= 0.830) (Table 2). The median CD value was 23.6 (25th-75th percentile IQR 21.2 to 27.8). The mean was 25.3, with a few higher values extending up to 48.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics: Categorical and Ordinal Variables

| Variable | value | All Patients | Gender | Compare Groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| Categorical Variables [n, (%)] | n = 192 | 62 (32.3%) | 130 (67.7%) | test | p - value | ||||

| Gender | Male | 62 (32.3%) | |||||||

| Female | 130 (67.7%) | ||||||||

| Eye | OS | 95 (49.5%) | 30 (48.4%) | 65 (50%) | chi | 0.834 | |||

| OD | 97 (50.5%) | 32 (51.6%) | 65 (50%) | ||||||

| Refraction group | myopia: RE < −0.5 | 56 (29.2%) | 19 (30.7%) | 37 (28.5%) | chi | 0.312 | |||

| hyperopia: RE > +0.5 | 79 (41.2%) | 29 (46.8%) | 50 (38.5%) | ||||||

| RE −0.5 to +0.5 | 57 (29.7%) | 14 (22.6%) | 43 (33.1%) | ||||||

| Guttae Severity | Missing | 3 (1.6%) | JT | 0.413 | |||||

| 0.5 | 14 (7.3%) | 8 (13.1%) | 6 (4.7%) | ||||||

| (Eyes with missing data NOT included in statistical test) | 1 | 27 (14.1%) | 5 (8.2%) | 22 (17.2%) | |||||

| 1.5 | 18 (9.4%) | 5 (8.2%) | 13 (10.2%) | ||||||

| 2 | 37 (19.3%) | 13 (21.3%) | 24 (18.8%) | ||||||

| 2.5 | 30 (15.6%) | 6 (9.8%) | 24 (18.8%) | ||||||

| 3 | 22 (11.5%) | 12 (19.7%) | 10 (7.8%) | ||||||

| 3.5 | 20 (10.4%) | 3 (4.9%) | 17 (13.3%) | ||||||

| 4 | 21 (10.9%) | 9 (14.8%) | 12 (9.4%) | ||||||

| Cataract Grade | 0 | 58 (30.2%) | 18 (29%) | 40 (30.8%) | JT | 0.259 | |||

| 0.5 | 4 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.1%) | ||||||

| 1 | 11 (5.7%) | 4 (6.5%) | 7 (5.4%) | ||||||

| 1.5 | 18 (9.4%) | 3 (4.8%) | 15 (11.5%) | ||||||

| 2 | 70 (36.5%) | 25 (40.3%) | 45 (34.6%) | ||||||

| 2.5 | 18 (9.4%) | 5 (8.1%) | 13 (10%) | ||||||

| 3 | 11 (5.7%) | 5 (8.1%) | 6 (4.6%) | ||||||

| 4 | 2 (1%) | 2 (3.2%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| Corneal Edema | 0 | 156 (81.3%) | 45 (72.6%) | 111 (85.4%) | JT | 0.024 | * | ||

| 0.5 | 12 (6.3%) | 4 (6.5%) | 8 (6.2%) | ||||||

| 1 | 14 (7.3%) | 7 (11.3%) | 7 (5.4%) | ||||||

| 1.5 | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

| 2 | 6 (3.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | 3 (2.3%) | ||||||

| 2.5 | 2 (1%) | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||||||

| 3 | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | ||||||

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

% = percent; chi = chi-square test; JT = Jonckheere-Terpstra test; n = number; OD = right eye; OS = left eye; RE = refractive error;

Table 2:

Descriptive Statistics: Continuous and Ordinal Variables

| Patient Group | number (number missing) | mean (standard deviation, SD) | 5-Number Summary [minimum, 25th percentile, median, 75th percentile, maximum] | Compare Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean diff, (95% CI diff.), median diff | p - value | |||||

| Variable | ||||||

| Continuous Variables (all independent-samples t-tests) | ||||||

| CDVA logMAR | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 0.18 (0.2) | [−0.1, 0, 0.2, 0.3, 1.6] | 0.01 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 0.18 (0.19) | [−0.1, 0, 0.2, 0.3, 0.8] | (−0.05, 0.07) | 0.83 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 0.18 (0.2) | [−0.1, 0, 0.2, 0.3, 1.6] | 0.00 | ||

| Age | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 71.6 (9.4) | [35, 67, 72, 77, 91] | 1.2 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 72.4 (9.2) | [35, 68, 73.5, 80, 89] | (−1.7, 4.1) | 0.418 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 71.2 (9.5) | [35, 66, 72, 76, 91] | 1.5 | ||

| CD 0–2 mm | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 25.5 (6.1) | [17.3, 21.2, 23.9, 28, 48] | −0.4 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 25.2 (6.8) | [17.3, 20.3, 22.6, 28.1, 48] | (−2.4, 1.6) | 0.675 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 25.6 (5.7) | [17.7, 21.5, 24.2, 27.9, 45.6] | −1.6 | ||

| CD 2–6 mm | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 23.5 (4.9) | [15.9, 19.7, 22.6, 26.4, 41.5] | −0.1 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 23.4 (5.4) | [15.9, 19.3, 21.8, 26.7, 41.5] | (−1.6, 1.4) | 0.872 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 23.5 (4.6) | [15.9, 19.8, 22.7, 26.3, 37.8] | −0.9 | ||

| CD 6–10 mm | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 34 (8.9) | [16.6, 27.3, 32.5, 40.9, 56.9] | 0.9 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 34.6 (8.4) | [17.1, 28.5, 33.1, 42.1, 55.6] | (−1.8, 3.6) | 0.51 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 33.7 (9.2) | [16.6, 27, 32.4, 40.5, 56.9] | 0.6 | ||

| CD 10–12 mm | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 37.4 (9.4) | [16.5, 30.5, 36.6, 44.2, 65] | −0.6 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 37 (9.6) | [22.7, 30.7, 34.8, 43.8, 60.7] | (−3.5, 2.3) | 0.687 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 37.6 (9.4) | [16.5, 30.5, 37.7, 44.6, 65] | −3.0 | ||

| CCT | All Eyes | 175 (17) | 597.3 (48.1) | [486, 563, 595, 628, 770] | 1.7 | |

| Male | 56 (6) | 598.4 (54.2) | [486, 557, 592.5, 641.5, 742] | (−13.8, 17.1) | 0.83 | |

| Female | 119 (11) | 596.7 (45.2) | [514, 566, 595, 618, 770] | −2.5 | ||

| Refractive Error SE | All Eyes | 192 (0) | 0.14 (2.13) | [−7.75, −0.75, 0, 1.5, 5.25] | 0.24 | |

| Male | 62 (0) | 0.31 (2.07) | [−6, −1, 0.2, 1.75, 4.5] | (−0.41, 0.89) | 0.469 | |

| Female | 130 (0) | 0.07 (2.16) | [−7.75, −0.75, 0, 1.5, 5.25] | 0.20 | ||

| Ordinal Variables (means and SD do not apply to ordinal variables) All Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon 2-sample tests | ||||||

| Guttae | All Eyes | 189 (3) | [0.5, 1.5, 2, 3, 4] | |||

| Male | 61 (1) | [0.5, 1.5, 2, 3, 4] | 0.0 | 0.826 | ||

| Female | 128 (2) | [0.5, 1.5, 2, 3, 4] | ||||

| Cataract Grade | All Eyes | 192 (0) | [0, 0, 2, 2, 4] | |||

| Male | 62 (0) | [0, 0, 2, 2, 4] | 0.5 | 0.261 | ||

| Female | 130 (0) | [0, 0, 1.5, 2, 3] | ||||

| Corneal Edema | All Eyes | 192 (0) | [0, 0, 0, 0, 3] | |||

| Male | 62 (0) | [0, 0, 0, 0.5, 3] | 0.0 | 0.025 * | ||

| Female | 130 (0) | [0, 0, 0, 0, 2.5] | ||||

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001.

CCD = central corneal densitometry; CCT = central corneal thickness; CDVA = corrected distance visual acuity; CI = confidence interval; Diff. = difference; LogMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; mm = millimeters;

Spearman correlations were statistically significant between logMAR CDVA and age (rho = 0.29, P <0.001), CD values at the 0–2 mm zone (rho = 0.49, P <0.001), CD values at the 2–6 mm zone (rho = 0.46, P <0.001), CD values at the 6–10 mm zone (rho = 0.27, P <0.001), CD values at the 10–12 mm zone (rho = 0.18, P= 0.014), CCT (rho = 0.24, P= 0.001), guttae severity (rho = 0.30, P <0.001), and corneal edema grade (rho = 0.40, P <0.001). The Spearman correlation between logMAR CDVA and cataract grade was close to significant (rho = 0.12, P= 0.095) (Table 3).

Table 3:

Spearman Correlations with logMAR CDVA for continuous and ordinal variables

| Age (rho = 0.29, P <0.001***) |

| CD 0 to 2 mm (rho = 0.49, P <0.001***) |

| CD 2 to 6 mm (rho = 0.46, P <0.001***) |

| CD 6 to 10 mm (rho = 0.27, P < 0.001***) |

| CD 10 to 12 mm (rho = 0.18, P = 0.014*) |

| CCT (rho = 0.24, P = 0.001**) |

| Guttae Severity (rho = 0.30, P <0.001***) |

| Cataract Grade (rho = 0.12, P = 0.095†) |

| Corneal Edema (rho = 0.40, P <0.001***) |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001,

p<0.15 (marginally significant).

CD = corneal densitometry; CCT = central corneal thickness; CDVA = corrected distance visual acuity; LogMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; mm = millimeters; rho = Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient;

Final Multivariate Regression Model

The outcome variable CDVA did not follow a normal distribution pattern, primarily due to an outlier in which logMAR CDVA = 1.60 (Snellan CVDA = 20/800), despite all other values falling between logMAR CDVA −0.10 and 0.80 (Snellen CVDA 20/16 and 20/125). Without this outlier observation, logMAR CDVA had both skew (0.61) and kurtosis (0.57) less than 1.0, which is considered acceptable in order to assume a normal distribution.9 Because this outlier was eliminated due to missing severity of guttae, it had no effect on the built multivariate regression models. Results for each step of the backward selection approach for the multivariate regression model are displayed (Supplemental Table 1).

The final multivariate regression model (Table 4) indicates that an increase in central CD values at the 0–2 mm zone (P<0.001), severity of guttae (P=0.046), age (P<0.001), cataract grade (P<0.001), corneal edema grade (P<0.001), and hyperopia rather than myopia (P=0.008) were significantly associated with worse CDVA (increased logMAR). This final model estimated that a 3-unit increase in central CD values at the 0–2 mm zone was associated with an increase of 0.022 in logMAR CDVA. Over the range of CD values at the 0–2 mm zone in the sample (from 17.3 to 48.0), the model indicated an estimated increase in logMAR BCVA of 0.23. The regression model estimated that a 1-unit increase in severity of guttae was associated with an increase of 0.024 in logMAR CDVA. Over the range of severity of guttae in the sample (from 0.5 to 4.0), the model indicated an estimated increase in logMAR CDVA of 0.08. The regression model estimated that a 5-year increase in age was associated with an increase of 0.026 in logMAR CDVA. Over the age range in the sample (from 35 to 91 years), the model indicated an estimated increase in logMAR CDVA of 0.29. The regression model estimated that a 1-unit increase in cataract grade was associated with an increase of 0.050 in logMAR CDVA. Over the range of cataract grade in the sample (from 0.0 to 4.0), the model indicated an estimated increase in logMAR CDVA of 0.20. The regression model estimated that a 1-unit increase in corneal edema grade was associated with an increase of 0.117 in logMAR CDVA. Over the range of corneal edema grade in the sample (from 0.0 to 3.0), the model indicated an estimated increase in logMAR CDVA of 0.35. The regression model estimated that eyes with myopia had an estimated 0.061 greater logMAR CDVA than eyes with hyperopia. There were no significant differences in CDVA between eyes without refractive error and eyes with hyperopia and/or myopia (Table 4).

Table 4:

Final Generalized Estimating Equations Model to Predict CDVA

| beta 95% CI | Variable range | Effect over range | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Change | beta | low | high | p - value | minimum | maximum | ||

| Age | 5 year increase | 0.026 | 0.014 | 0.037 | <0.001 | *** | 35 | 91 | 0.29 |

| CD 0–2 mm | 3 unit increase | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.034 | <0.001 | *** | 17.3 | 48 | 0.23 |

| Guttae Severity | 1 unit increase | 0.024 | 0.000 | 0.047 | 0.046 | * | 0.5 | 4 | 0.08 |

| Cataract Grade | 1 unit increase | 0.050 | 0.029 | 0.070 | <0.001 | *** | 0 | 4 | 0.20 |

| Corneal Edema | 1 unit increase | 0.117 | 0.063 | 0.172 | <0.001 | *** | 0 | 3 | 0.35 |

| Refraction Group | Hyperopia to myopia | 0.061 | 0.016 | 0.106 | 0.008 | ** | hyperopia | myopia | 0.06 |

| Refraction Group | No refractive error to hyperopia | −0.026 | −0.071 | 0.019 | 0.256 | N/A – effect not significant N/A – effect not significant |

|||

| Refraction Group | No refractive error to myopia | 0.035 | −0.006 | 0.076 | 0.097 | † | |||

| Intercept | 0.172 | 0.137 | 0.207 | <0.001 | *** | ||||

| Total effect, over the ranges, of all statistically significant variables: | 1.21 | ||||||||

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001,

p < 0.15 (marginally significant).

CCD = central corneal densitometry; CDVA = corrected distance visual acuity; CI = confidence interval; hyperopia = refractive error GT plus 0.5; LogMAR = logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution; mm = millimeters; myopia = refractive error LT minus 0.5; N/A = not applicable; No refractive error = refractive error between −0.5 to +0.5; TOTAL = Total effect from all the “better” categories to all the “worse” (bolded) categories; NOTE: All Refraction Group effects must remain in the model as long as any of the effects are statistically significant.

In the final Generalized Estimating Equations model (Supplemental Table 2), both guttae (p < 0.0001) and corneal edema (p = 0.0018) were independently associated with the central CD values at the 0–2mm zone. The central CD values at 6–10mm nor at 10–12 mm were not associated with guttae or corneal edema in the final model (P values>0.05).

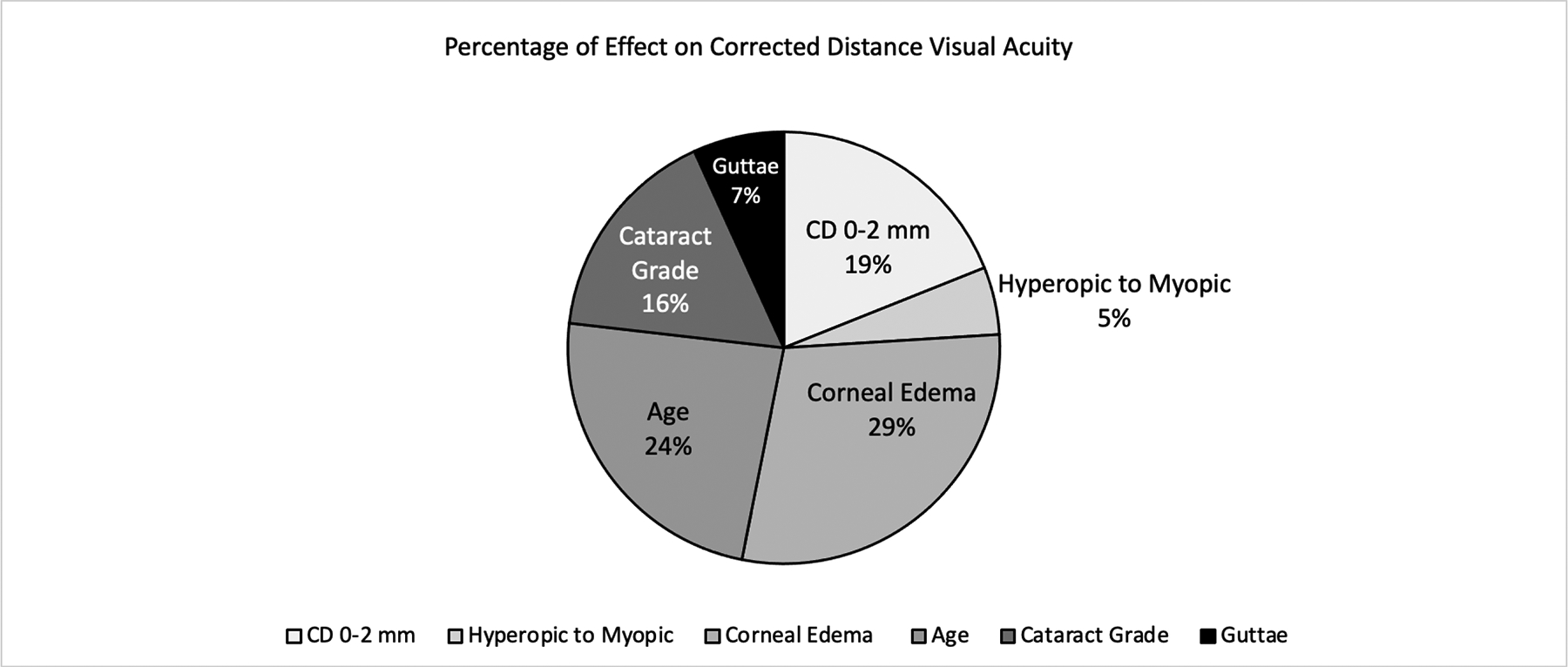

The hypothetical combined effect on 0.CDVA of all statistically significant variables in the final model (i.e. the predicted difference in CDVA between an eye with all minimum values of the explanatory variables to an eye with all maximum values) was 1.21 (Table 4). Clinically, a value of 1.21 is larger than the difference in 20/20 vision (logMAR VA = 0.00) and 20/200 vision (logMAR VA = 1.00). Generally, a difference in logMAR VA of 0.30 (approximately equivalent to 3 Snellen lines and 15 ETDRS letters)10 is considered to be clinically significant.11 Figure 1 illustrates the percent contribution of each explanatory variable’s statistically significant effect on the difference in CDVA between an eye with FECD with all the best (minimum) values to an eye with FECD with all the worst (maximum) values. A 3-unit increase in CD values at the central 0–2 mm zone contributes 19% to the overall impact on CDVA and a 1-unit increase in severity of guttae contributes 7%.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Effect on Corrected Distance Visual Acuity

CCT, gender, and the peripheral CD values (2–6, 6–10, and 10–12 mm) were not significantly associated with CDVA (p>0.05) in the final multivariate regression model despite the significant univariate Spearman correlations with CDVA for CCT and the peripheral CD values. Of the four CD values (0–2, 2–6, 6–10 and 10–12 mm), central CD values 0–2 mm had the strongest correlation (largest rho = 0.49) (Table 3). The peripheral CD values (2–6, 6–10, and 10–12 mm) all had statistically significant Spearman correlations with CD values 0–2 mm (2–6 mm: rho = 0.82, P <0.001), (6–10 mm: rho = 0.27, P <0.001), and (10–12 mm: rho = 0.16, P = 0.027). CCT also had a statistically significant Spearman correlation with CD values 0–2 mm (rho = 0.46, P <0.001), but the rho for CD values 0–2 mm was the largest and as a result, was utilized in the final model. Therefore, it is likely that the presence of CD values 0–2 mm in the final model caused these other variables to lose an independent significant association with CDVA.

DISCUSSION

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD) is a hereditary condition characterized by Descemet membrane thickening, the formation of guttae, a decline in corneal endothelial cells, corneal edema grade and increased corneal thickness. Patients with FECD describe vision loss and degradation of visual quality, but the extent to which each of the progressive corneal changes contribute to vision loss has been unclear. This study implicates several pathological features independently, including corneal densitometry (CD) measurements that reflect central stromal opacity and guttae.

In clinical practice, serial CCT measurements are often used as a sole indicator for progression of FECD disease and as a guide to therapeutic interventions.12 While CCT can serve as a useful measure in monitoring disease progression, this parameter is inadequate in serving as a single determinant in predicting disease severity or prognosis, especially as the baseline CCT prior to disease onset is often not available and CCT can vary greatly depending on demographics and environmental factors.13 This study suggests a multifactorial approach to understanding how FECD affects the quality of vision and offers insight into the relative contribution of each factor; patients and clinicians considering surgery may want to account for several of these variables in the decision-making process.

While it is thought that guttae themselves contribute to deterioration of vision, to our understanding, previous analyses suggesting that guttae are associated with light scatter14 have been unable to separate the effect of guttae from corneal thickness or edema as a confounding variable.15 In this study, guttae were a significant contributor to decreased CDVA even after adjusting for stromal changes in the cornea. This finding is relevant for patients who are increasingly undergoing Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK) at early stages of FECD16,17 and also for patients undergoing Descemet Stripping Only (DSO), a procedure in which central guttae are removed in milder stages of FECD.18,19 These data suggest that such patients, in addition to benefiting from a decrease in corneal edema, would also have potential to improve visual acuity from removing the visual aberrations produced by guttae alone.

Scheimpflug tomography is an important tool to quantify and predict corneal pathology associated with FECD. In addition to its ability to detect subclinical corneal edema and predict prognosis of FECD independent of CCT,20,21 the CD measurements can serve as a quantitative measurement of light scatter through the cornea; anterior and posterior corneal backscatter have been shown to be higher for all severities of FECD compared with controls,22,23 particularly in the central cornea.24 Our study demonstrates evidence that the increased CD at the central 0–2 mm zone is associated with decreased CDVA, independent of CCT. This held true even after adjusting for age, cataract grade, presence of corneal edema, and type of refractive error. As a result, this information is helpful for clinicians in guiding the management of cataract surgery in FECD patients. In addition, the implication of the central 0–2 mm in affecting visual acuity outcomes also carries relevance FECD for patients undergoing DSO, during which the Descemet membrane is stripped in the central 4 mm. While this central zone represents a fraction of the total area of the cornea, the data in this study suggest that it is within this zone that the pathological changes in FECD most strongly affect CDVA. Future studies would be needed to further define the implications of our findings on the CD values at the anterior and posterior layers of the cornea.

Interestingly, in the final model, hyperopic refractive error was associated with worse CDVA after adjusting for other factors, relative to eyes with myopia. While it is possible that much of the variability in refractive error may be due to axial length, the contribution of corneal pathology cannot be ruled out. One possibility might be that corneas that are flatter at baseline, and therefore more likely to be hyperopic, also experience distinct higher order aberrations with FECD relative to steeper corneas. Another possibility is that patients with more severe FECD experience a secondary hyperopic shift; in this case, the association may be one of correlation but not causation. Further research may better elucidate the extent to which each of these processes contributes to changes in vision.

Supplementary Material

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT (SDC) LEGEND

Supplemental Table 1. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) Model to Predict CDVA Stepwise Selection Process

Supplemental Table 2. Final Generalized Estimating Equations Models to Predict CCD values

Disclosure of Funding:

The study was funded in part by the NIH Core Center Grant P30EY014801.

Footnotes

Submitted work was presented as a Scientific Poster at the American Academy of Ophthalmology, November, 2020

No conflicting financial interests exists for any author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eye Bank Association of America, 2019. Eye Banking Statistical Report. www.restoresight.org. Accessed December 26, 2020.

- 2.Otri AM, Fares U, Al-Aqaba MA, Dua HS. Corneal densitometry as an indicator of corneal health. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:501–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tekin K, Sekeroglu MA, Kiziltoprak H, Yilmazbas P. Corneal Densitometry in Healthy Corneas and Its Correlation With Endothelial Morphometry. Cornea. 2017;36:1336–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorovoy MS. Descemet-stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2006;25:886–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melles GRJ, Ong TS, Ververs B, van der Wees J. Descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). Cornea. 2006;25:987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borkar DS, Veldman P, Colby KA. Treatment of Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy by Descemet Stripping Without Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2016;35:1267–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein BE, Klein R, Linton KL. Prevalence of age-related lens opacities in a population. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krachmer JH. Corneal endothelial dystrophy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darren G, Mallery P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference Fourth Edition (11.0 update). In: 4th ed. Pearson; 2003:98–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott DB. The good (logMAR), the bad (Snellen) and the ugly (BCVA, number of letters read) of visual acuity measurement. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt J Br Coll Ophthalmic Opt Optom. 2016;36:355–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suñer IJ, Kokame GT, Yu E, Ward J, Dolan C, Bressler NM. Responsiveness of NEI VFQ-25 to changes in visual acuity in neovascular AMD: validation studies from two phase 3 clinical trials. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3629–3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kopplin LJ, Przepyszny K, Schmotzer B, Rudo K, Babineau DC, Patel SV, Verdier DD, Jurkunas U, Iyengar SK, Lass JH; Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy Genetics Multi-Center Study Group. Relationship of Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy severity to central corneal thickness. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:433–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sng CC, Ang M, Barton K. Central corneal thickness in glaucoma. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2017;28:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe S, Oie Y, Fujimoto H, Soma T, Koh S, Tsujikawa M, Maeda N, Nishida K. Relationship between Corneal Guttae and Quality of Vision in Patients with Mild Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:2103–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wacker K, McLaren JW, Patel SV. Re: Watanabe et al.: Relationship between corneal guttae and quality of vision in patients with mild Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (Ophthalmology 2015;122:2103–9). Ophthalmology. 2016;123:e23–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price FW Jr, Price MO. Combined Cataract/DSEK/DMEK: Changing Expectations. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2017;6:388–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunker SL, Veldman MHJ, Winkens B, van den Biggelaar FJHM, Nuijts RMMA, Kruit PJ, Dickman MM; Dutch Cornea Consortium. Real-World Outcomes of DMEK: A Prospective Dutch registry study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;2;222:218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macsai MS, Shiloach M. Use of Topical Rho Kinase Inhibitors in the Treatment of Fuchs Dystrophy After Descemet Stripping Only. Cornea. 2019;38:529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moloney G, Garcerant Congote D, Hirnschall N, Arsiwalla T, Luiza Mylla Boso A, Toalster N, DʼSouza M, Devasahayam RN. Descemet Stripping Only Supplemented With Topical Ripasudil for Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy 12-Month Outcomes of the Sydney Eye Hospital Study. Cornea. 2020. Jul 31. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002437. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun SY, Wacker K, Baratz KH, Patel SV. Determining Subclinical Edema in Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: Revised Classification using Scheimpflug Tomography for Preoperative Assessment. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel SV, Hodge DO, Treichel EJ, Spiegel MR, Baratz KH. Predicting the Prognosis of Fuchs Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy by Using Scheimpflug Tomography. Ophthalmology. 2020;127:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wacker K, McLaren JW, Amin SR, Baratz KH, Patel SV. Corneal High-Order Aberrations and Backscatter in Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chu HY, Hsiao CH, Chen PY, Ma DH, Chang CJ, Tan HY. Corneal Backscatters as an Objective Index for Assessing Fuchs’ Endothelial Corneal Dystrophy: A Pilot Study. J Ophthalmol. 2017;2017:8747013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alnawaiseh M, Zumhagen L, Wirths G, Eveslage M, Eter N, Rosentreter A. Corneal Densitometry, Central Corneal Thickness, and Corneal Central-to-Peripheral Thickness Ratio in Patients With Fuchs Endothelial Dystrophy. Cornea. 2016;35:358–62.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT (SDC) LEGEND

Supplemental Table 1. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) Model to Predict CDVA Stepwise Selection Process

Supplemental Table 2. Final Generalized Estimating Equations Models to Predict CCD values