Abstract

High blood pressure in the postpartum period is most commonly seen in women with antenatal hypertensive disorders but it can develop de novo in the postpartum timeframe. Whether postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia represents a separate entity from preeclampsia / eclampsia with antepartum onset is unclear. While definitions vary, the diagnosis of postpartum preeclampsia should be considered in women with new-onset hypertension 48 hours to 6 weeks postpartum. New-onset postpartum preeclampsia is an understudied disease entity with few evidence-based guidelines to guide diagnosis and management. We propose that new-onset hypertension with the presence of any severe features (including severely elevated blood pressure in women with no history of hypertension) be referred to as postpartum preeclampsia after exclusion of other etiologies to facilitate recognition and timely management. Older maternal age, black race, and maternal obesity as well as cesarean delivery are all associated with a higher risk of postpartum preeclampsia. The majority of women with delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia present within the first 7–10 days postpartum, most frequently with neurologic symptoms, typically headache. The cornerstones of treatment include the use of anti-hypertensive agents, magnesium and diuresis. Postpartum preeclampsia may be associated with a higher risk of maternal morbidity than preeclampsia with antepartum-onset, yet remains a significantly understudied disease process. Future research should focus on the pathophysiology and specific risk factors. A better understanding is imperative for patient care and counseling, anticipatory guidance prior to hospital discharge and is critically important for reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality in the postpartum period.

Keywords: new-onset postpartum preeclampsia, delayed onset postpartum preeclampsia, hypertension, pregnancy, postpartum, postpartum hypertension, postpartum eclampsia

CONDENSATION

We review the etiology, risk factors, clinical manifestations, management and outcomes for pregnancies complicated by new-onset postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy complicate between 10–20% of pregnancies in the United States. They are responsible for a significant proportion of maternal morbidity and mortality and the number one reason for postpartum hospital readmission.1–3 While the majority of cases are diagnosed during the antepartum period, new-onset or de novo postpartum preeclampsia is increasingly being recognized as an important contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality in the postpartum period.4 High blood pressure in the postpartum period is most commonly seen in women with antenatal hypertensive disorders but it can develop de novo in the postpartum timeframe. While definitions vary, the diagnosis of postpartum preeclampsia should be considered in women with new-onset hypertension in the postpartum period. There is a need for improved terminology surrounding immediate postpartum preeclampsia (within the first 48 hours after delivery) and delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia, which has traditionally been defined as new-onset preeclampsia after 48 hours postpartum through 6 weeks postpartum. The majority of reports on postpartum preeclampsia are limited to smaller case series, thus the overall incidence has not been reliably ascertained in a prospective fashion. Literature estimates on the prevalence range between 0.3% to 27.5% of all pregnancies in the United States.5 The wide variation likely reflects that milder disease may go unnoticed postpartum, and many women may present to urgent care centers, emergency rooms or primary care physicians who may be less familiar with this disease process and the potential for adverse maternal outcomes.

Whether postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia represents a distinct entity from preeclampsia / eclampsia with antepartum-onset is unclear and remains a source of debate. In this review, we do not necessarily propose to label it as a separate disease process, but will discuss the limited literature surrounding this entity and highlight its importance in postpartum care and the need for better recognition and timely management. We intend here to review risk factors, clinical manifestations and management as well as maternal outcomes for pregnancies complicated by postpartum preeclampsia. Additionally, we will attempt to address the understudied aspects of the disease, including potential etiologies and implications for future maternal health as well as priorities for future research.

DEFINITION

Few national or international guidelines address new-onset postpartum hypertension and there are no clear definitions within existing guidelines. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG)/National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) do not specifically define postpartum preeclampsia and do not distinguish between new-onset postpartum preeclampsia and new-onset postpartum hypertension.4,6,7 In our experience, this is a diagnostic question that frequently arises when providing clinical care for this population of women.

In regards to timing, we propose that the diagnosis of postpartum preeclampsia should be considered in women with new-onset preeclampsia after 48 hours postpartum through 6 weeks postpartum. Although this timing is not explicitly defined, this is the terminology used by experts and existing literature on the topic.8–10 We acknowledge that the postpartum timeframe is a continuum and this timeframe may need to be modified as we better understand the pathophysiology of this condition. Forty-eight hours has traditionally been used because this generally encompasses immediate postpartum changes and usual in-hospital management. Importantly, other causes should be considered in cases of postpartum hypertension and seizures beyond 4 weeks postpartum. We believe further study is needed to determine if new-onset postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia is a distinct entity from preeclampsia with antepartum-onset; that said, we recommend that this condition be highlighted here and in national/international guidelines as it is under-recognized by providers.

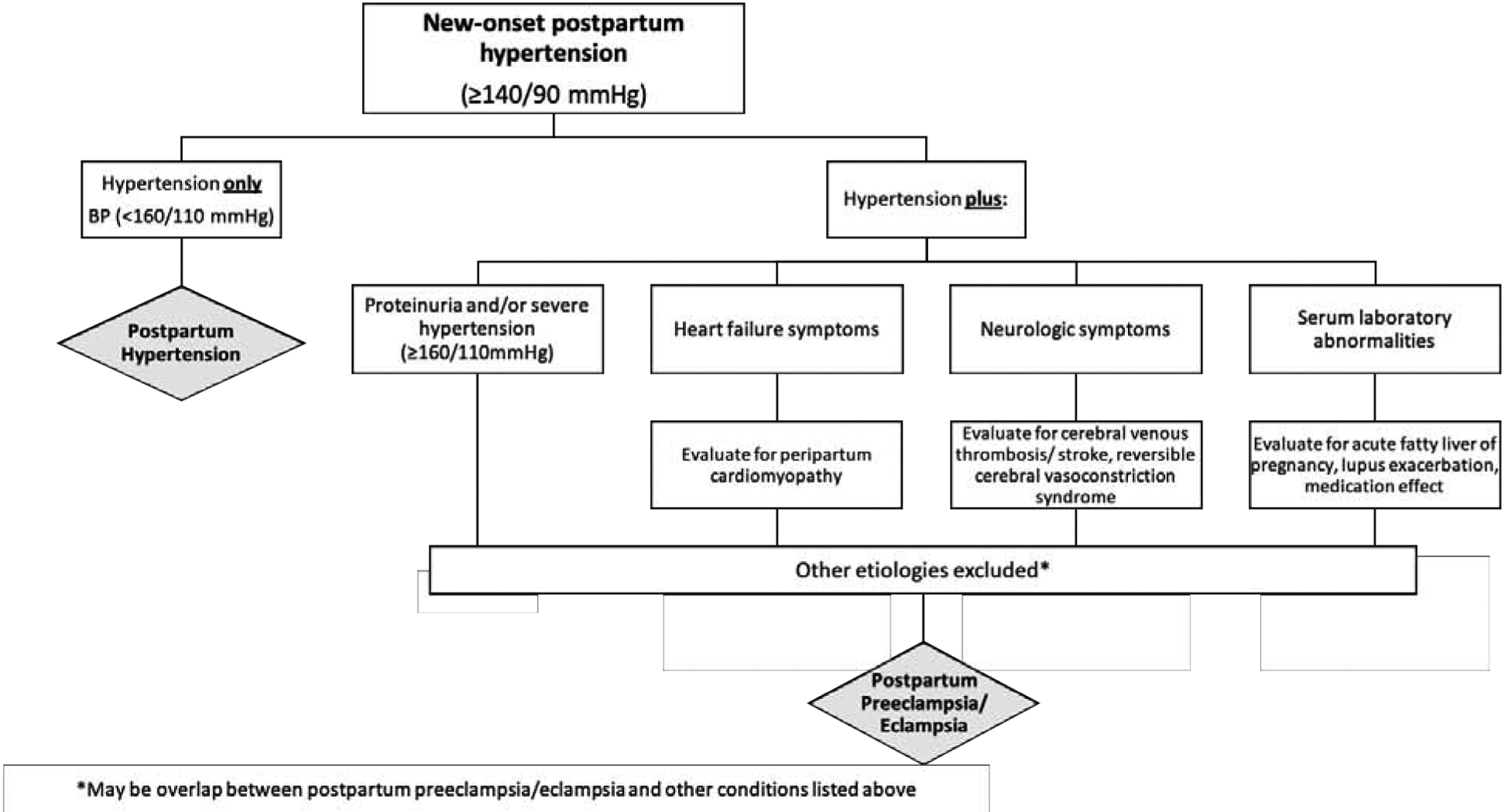

The definitions of hypertension and preeclampsia are extrapolated from guidelines surrounding hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with antepartum-onset, i.e. 140/90mmHg.4 There is no evidence to suggest that the presence of proteinuria is associated with worse clinical outcomes or that it is helpful in differentiating between potential subtypes of postpartum hypertension. In our clinical experience, women without proteinuria appear to be just as likely to experience adverse clinical outcomes as women with significant proteinuria. However, recognizing the limited data on clinical outcomes, we suggest continuing to evaluate for proteinuria, consistent with existing guidelines, until further studies evaluating outcomes in this population are available. Extrapolating from ACOG guidelines on the antepartum diagnosis of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, we suggest that less emphasis be placed on the presence of proteinuria among women with new-onset postpartum hypertension.4 We present a suggested evaluation and diagnostic framework in Figure 1. Of note, in line with ACOG recommendations regarding preeclampsia with antepartum-onset, elevated blood pressure should be confirmed on two occasions at least four hours apart, except in the case of severe hypertension, which should be confirmed within minutes to facilitate timely treatment. In the absence of specific postpartum definitions from ACOG, we propose that the presence of any severe features (including severely elevated blood pressure in women with no history of hypertension) be referred to as postpartum preeclampsia after exclusion of other etiologies. This is in line with the current guidelines on antepartum-onset of disease with removal of the term “mild preeclampsia” to emphasize the significant maternal morbidity associated with pregnancy-related hypertension.11 We suggest reserving the term postpartum hypertension for women with non-severe hypertension (≥140/90 mmHg but <160/110 mmHg) and no other end-organ involvement or other severe features. (Table 1 and Figure 1). While severe postpartum hypertension may represent undiagnosed chronic hypertension or exacerbation of chronic hypertension, the presence of severe features warrants further work-up and management similar to those outlined for postpartum preeclampsia.

Figure 1.

Suggested approach to new-onset postpartum hypertension

Table 1.

Approach to women with postpartum preeclampsia

| POSTPARTUM PREECLAMPSIA: PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA |

|---|

| Blood Pressure: New-onset hypertension on more than one occasion, four hours or more apart (systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or more) within 6 weeks of delivery with no other identifiable etiology |

AND

|

|

OR Systolic blood pressure of 160 mmHg or more or diastolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg or more within 6 weeks of delivery with no other identifiable etiology in the absence of any of the above features |

| DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATIONS |

|

| MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS |

|

RISK FACTORS

Demographics

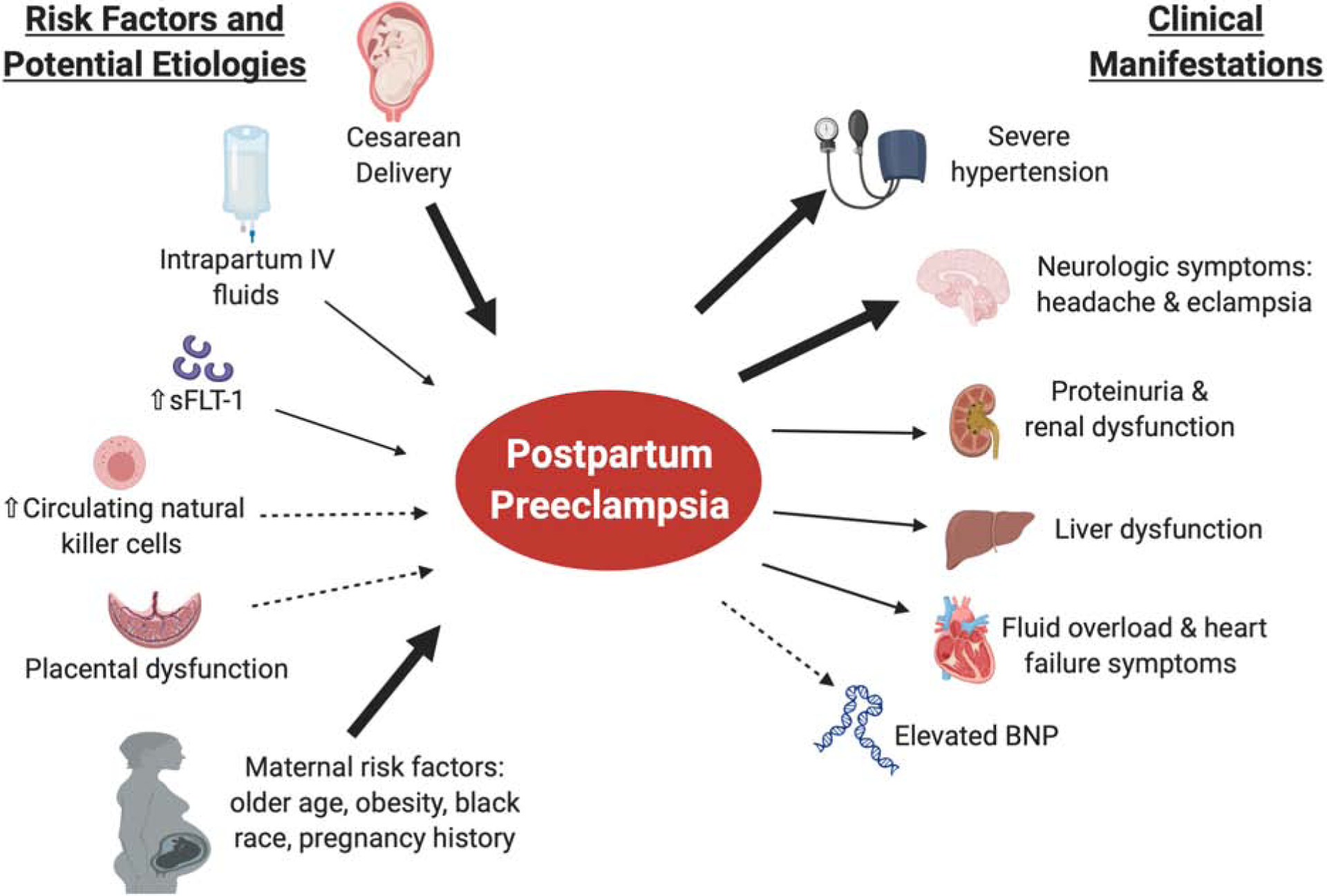

Multiple cohort studies have addressed risk factors for postpartum preeclampsia, and in general have found similar overlap with risk factors for preeclampsia with antepartum onset (Figure 1). Older maternal age, black race, and maternal obesity are associated with a higher risk of postpartum preeclampsia. Age ≥ 35 years has been repeatedly demonstrated to be associated with an approximately two-fold increased risk for postpartum preeclampsia.12,13 Pre-pregnancy obesity appears to be consistently associated with an increased risk of postpartum preeclampsia in a dose-dependent fashion, with an up to 7.7-fold increased risk associated with BMI greater than 40 kg/m2. Black women have a 2–4-fold increased risk of postpartum preeclampsia compared to women of other races.8,14 Unlike antepartum preeclampsia, postpartum preeclampsia does not appear to be more common among primiparous women.8,15 Postpartum preeclampsia develops more commonly among women with a history of a hypertensive disorder in a prior pregnancy.8,13

Intrapartum risk factors

Cesarean delivery increases the risk of postpartum preeclampsia by 2- to 7-fold compared to vaginal delivery, which is a consistent finding across multiple studies.8,12–15 Higher rates of intravenous (IV) fluid infusion on labor and delivery is also associated with an increased risk of postpartum preeclampsia.14 To our knowledge, published studies do not distinguish between pre-labor cesarean deliveries versus intra-partum cesarean sections, which would likely impact the amount of IV fluids administered. Women who receive greater volumes of IV crystalloids during labor and delivery may shift more fluid to the interstitial compartment and may subsequently be more likely to develop volume overload and hypertension when the fluid is remobilized to the intravascular space post-delivery. Overall, studies have not shown an increased risk of postpartum preeclampsia associated with the use of epidural anesthesia and pharmacologic agents that might be hypothesized to raise blood pressure, such as vasopressors or ergot derivatives in labor or postpartum.13,14

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

As noted above, postpartum preeclampsia can develop following a pregnancy with no antecedent diagnosis of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy or following a pregnancy complicated by gestational hypertension or in women with underlying chronic hypertension. Approximately 60% of patients with new, delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia have no antecedent diagnosis of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.16 The majority of women with delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia present within the first 7–10 days postpartum, however, this varies widely in the literature with onset up to 3 months postpartum reported.17 Women most frequently present with neurologic symptoms, typically headache, which has consistently been reported as the most common symptom in approximately 60–70% of women across multiple studies (Figure 2).8,14,16,18 Postpartum headache is exceedingly common; however, there are certain characteristics that should prompt additional investigation with imaging and/or consultation with a Neurologist or Neurosurgeon. In particular, refractory or thunderclap headaches or any headache associated with altered mental status, seizures, visual disturbances or focal neurologic deficits should prompt an evaluation for other cerebrovascular etiologies. In addition to postpartum preeclampsia, the differential diagnosis for postpartum headache should include migraine headache, post-dural puncture headache, medication-related headache, cerebral venous thrombosis, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome.19,20

Figure 2.

Risk factors, etiology and clinical manifestations of postpartum preeclampsia.

In prior studies, 21% of eclampsia occurs postpartum.21 Less commonly, eclampsia has been reported as the presenting symptom in up to 10–15% of women with delayed postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia.16,22 Other symptoms include those associated with volume overload such as shortness of breath, chest pain and peripheral edema. Less commonly, women may present with blood pressure elevations noted to either a physician’s office or as noted on home blood pressure monitoring, however, postpartum blood pressure monitoring is not universally recommended for women without signs or symptoms of a hypertensive disorder.8 These findings emphasize the importance of appropriate patient education regarding signs and symptoms that should prompt evaluation after discharge from the delivery hospitalization. Further, as women without an antenatal HDP typically do not have a visit with an obstetric provider for 2–6 weeks postpartum, appropriate education of other providers who may interact with women during the initial postpartum period, such as pediatricians, is critical to ensure timely identification and management. In an effort to facilitate early detection of postpartum preeclampsia, our institution has initiated a quality improvement initiative to screen women with blood pressure measurement and for symptoms of preeclampsia during well newborn exams. Similar efforts and education are imperative for all providers who interact with women in the postpartum period, including Emergency Medicine providers, Primary Care and Family Practice physicians. A review of maternal death in California from 2002 to 2007 demonstrated that the emergency department was a site with several improvement opportunities. Among women who died from pregnancy-related causes, two-thirds received care in an emergency department at some point during the prenatal or postpartum timeframe.23 Multi-disciplinary approaches to care of women in the postpartum period are critical to early detection and reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality.

EVALUATION OF NEW-ONSET POSTPARTUM HYPERTENSION

Labs and Imaging

Diagnostic evaluation of new-onset postpartum hypertension should include a detailed history and physical exam, with close attention to clinical volume status, cardiopulmonary and neurologic exam based on presenting signs and symptoms (Table 1). Serum laboratory evaluation should include assessment of electrolytes and renal function, platelet count, liver enzymes and urine protein assessment. Prior studies have demonstrated that approximately 25% of women have abnormal serum laboratory values and approximately 20–40% have an elevated urine protein / creatinine ratio (0.3 or higher).8,16 Further laboratory assessment and imaging studies should be guided by the clinical presentation. The majority of women presenting with postpartum preeclampsia undergo at least one radiologic study (74%).8 We review below the most common clinical presentations of postpartum preeclampsia and suggested workup.

In women with neurologic symptoms, such as headache or vision changes that persist after management of severe hypertension, neuroimaging should be considered to evaluate for cerebrovascular accident or posterior reversible cerebral encephalopathy (PRES). The differential diagnosis may include other etiologies of postpartum headache, such as post-dural puncture headache, subarachnoid hemorrhage, central venous sinus thrombosis, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and migraine. For women with clinical evidence of volume overload, assessment of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) can be useful to both confirm the diagnosis of fluid overload as well as to guide management. BNP has an established role in the diagnosis, prognosis and risk stratification of heart failure outside of pregnancy.24 Secreted predominantly by the left ventricular cardiac myocytes in response to increased wall tension, BNP increases diuresis and decreases vascular tone.25 Prior studies have demonstrated high correlation of serum BNP levels with echocardiography findings of fluid overload in pregnancy.26–28 Among women with postpartum preeclampsia at our institution with a BNP measured at the time of presentation (n=22), the median value was noted to be 424 [IQR 190–645] pg/mL (upper limit of normal <100 pg/mL).8 Women with clinical evidence of volume overload or signs and symptoms of heart failure, such as shortness of breath, orthopnea or palpitations should also be evaluated for peripartum cardiomyopathy with a transthoracic echocardiogram.

There is conflicting evidence about the benefit of uterine curettage at shortening resolution time of hypertension and laboratory abnormalities among women with preeclampsia with antepartum-onset.29,30 Based on this, we do not routinely recommend uterine curettage for women with postpartum preeclampsia in the absence of retained products of conception. Thus, we recommend pelvic ultrasound to evaluate for retained products of conception only in women with a suggestive history.

Other etiologies of hypertension

The most common cause of hypertension in the postpartum period is a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.5 However, if the patient does not clearly meet criteria for a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, then secondary causes of hypertension should be considered (Figure 1). Other etiologies include preexisting renal disease, peripartum cardiomyopathy, lupus exacerbation, hyperthyroidism, primary hyperaldosteronism, renal artery stenosis, cerebrovascular accident, drug or medication use and pheochromocytoma. Appropriate workup should be guided by the clinical presentation and may include additional labs and imaging such as renal artery ultrasound, thyroid function studies, basic metabolic panel and urine metanephrines. Involvement of additional consultants would clearly be warranted for further evaluation and management of these conditions. A previously published review article on this topic provides a comprehensive framework detailing the differential diagnosis and approach to workup of alternative etiologies of hypertension in this period.5

MANAGEMENT

Anti-hypertensive agents

Similar to management of preeclampsia with antepartum-onset, the cornerstone of management of postpartum preeclampsia is acute treatment of severe hypertension. There is clear evidence that sustained, severe hypertension is associated with an increased risk of maternal morbidity, including cerebrovascular accident and eclampsia.31 Cerebral perfusion pressure is increased in preeclampsia compared to healthy pregnant women. During the postpartum period, mean cerebral blood flow velocities significantly increase in preeclamptic women. Both cerebral hyperperfusion and increased cerebral perfusion pressure increase wall tension of cerebral vessels and can therefore increase the risk of intracerebral hemorrhage.32 ACOG recommends treating women with sustained, severe hypertension (≥160/110 mmHg) with rapid-acting anti-hypertensive agents within thirty to sixty minutes. Agents used for management of acute, severe hypertension in the postpartum period are similar to those used during pregnancy and include IV labetalol, IV hydralazine and oral nifedipine as first-line agents.33 Prior studies have addressed differences in time to blood pressure control with the use of IV hydralazine compared to IV labetalol and have found no difference.34 Some indirect evidence suggests that oral nifedipine may be superior to hydralazine or labetalol for management of acute, severe hypertension, however, these studies predominantly enrolled women during pregnancy and there is a dearth of evidence regarding the efficacy of specific anti-hypertensive agents in the postpartum period.35,36 As there are no longer fetal considerations post-delivery, a lower threshold for initiating treatment such as 150/100mmHg may be considered to prevent progression to severe hypertension.37 Further studies are needed to determine optimal BP targets and ranges for initiation and maintenance in the setting of postpartum preeclampsia.

Following initial stabilization of blood pressure, women should be initiated on oral anti-hypertensive agents if hypertension persists. Both ACOG and the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (RCOG)/National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend achieving a range of 140–150/90–100 mmHg.4,33,38 As there are no standardized management guidelines for specific anti-hypertensive agents or parameters for medication titration in the postpartum period, physician preference, experience, cost of drug, safety during breast-feeding and frequency of administration become important factors that impact choice of therapy.39 Options for oral anti-hypertensive agents are discussed in detail elsewhere and are beyond the scope of this review.6

Magnesium Sulfate

While magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis is a key component of management of antepartum-onset preeclampsia with severe features, few evidence-based recommendations exist to guide the use of magnesium sulfate in women with postpartum preeclampsia.40 ACOG recommends the use of magnesium sulfate for women with new-onset hypertension associated with headaches or blurred vision or preeclampsia with severe hypertension in the postpartum period, while acknowledging that this recommendation is based on low-quality evidence.41 Eclampsia most commonly presents within 48 hours following delivery, with the highest risk time period extending through the first week postpartum.16,42 However, as noted above, women with postpartum preeclampsia most frequently present with neurologic symptoms, including headache and eclampsia has been documented in 10–15% of women in larger case series.16,22 The authors, therefore, recommend use of magnesium for new-onset postpartum preeclampsia with any associated neurologic symptoms, particularly within the first week postpartum. Among women with severe disease as diagnosed by other non-neurologic features, such as severe hypertension, a discussion of risks and benefits of treatment is reasonable, particularly beyond the first week postpartum.

Diuresis

Multiple studies have noted the prevalence of clinical signs and symptoms of volume overload among women with postpartum preeclampsia, including shortness of breath (20–30%), peripheral edema (11–18%), and pulmonary edema (11%)8,16. Diuretics lower blood pressure by promoting natriuresis and decreasing intravascular volume which help to decrease cardiac preload and cardiac output.43 The authors recommend thoughtful assessment of clinical volume status, using such parameters as urine output, weight change from delivery hospitalization and clinical exam findings. In women with clinical evidence of volume overload, we recommend use of diuresis to potentially further lower blood pressure and shorten postpartum readmission. As noted above, the use of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) as an adjunctive tool to inform decision-making concerning volume status also appears to be promising.44 Adequate diuresis can typically be achieved with use of IV or oral furosemide and concurrent monitoring and repletion of serum electrolytes. For women with significant volume overload, consideration for a short-course of daily oral furosemide is reasonable (3–5 days). Several randomized controlled trials have investigated the use of prophylactic diuresis with furosemide among women with preeclampsia with antepartum-onset. In one study, women who had preeclampsia with severe features randomized to treatment with furosemide 20mg orally daily were found to have significantly lower blood pressure on postpartum day 2 and require significantly less antihypertensive therapy on discharge compared to women treated with placebo.45 A more recent study demonstrated improved blood pressure control and less need for anti-hypertensive medication among all women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy randomized to furosemide 20mg orally daily for the first five days postpartum compared to women treated with placebo.46 While further study is needed to support the routine use of prophylactic diuresis among women without clinical evidence of volume overload, in women with evidence of volume overload, we recommend a short course of diuresis to potentially lower blood pressure and shorten postpartum readmission.

Home blood pressure monitoring

Among women with antepartum hypertensive disorders, blood pressure increases at 3–7 days postpartum.43 The etiology for this exacerbation is unclear, however, others have speculated that it may be due to mobilization of fluid during this time period.43 Among women with antepartum-onset hypertensive disorders, remote hypertension monitoring improves compliance with ACOG recommendations surrounding blood pressure assessment within the first 3–10 days postpartum, reduces disparities in BP ascertainment and may identify women with otherwise unrecognized blood pressure elevations requiring medication in this period.4,47–49 While home blood pressure monitoring has not been studied specifically among a population of women with postpartum preeclampsia, based on existing data, the authors would advocate for its use as it has the potential to shorten the time of rehospitalization postpartum and allow for detection and management of severe hypertension after hospital discharge without relying on in-office assessment. This may be particularly useful in light of overall low attendance rates at in-person postpartum follow up visits and initiatives by ACOG to develop innovative approaches to delivering postpartum care.47

ETIOLOGY OF POSTPARTUM PREECLAMPSIA

Typically, hypertension resolves relatively rapidly following delivery, with blood pressure returning to pre-pregnancy range in the ensuing days to weeks. The traditional adage in obstetrics has always been that delivery of the placenta “cures” preeclampsia, thus the onset of preeclampsia days to weeks after placental delivery raises questions about whether delayed postpartum preeclampsia is a sub-type of antepartum preeclampsia or whether it represents a separate disease entity. Studies of angiogenic factors, inflammatory profiles and placental pathology have been useful in informing this distinction. Anti-angiogenic soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt1) is a well-established pathogenic factor in preeclampsia and imbalances between sFlt1 and the proangiogenic placental growth factor (PlGF) have been linked to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia with antepartum onset.50 A prospective study that collected blood samples prior to cesarean section noted that women who developed new onset postpartum preeclampsia had significantly higher sFlt1 levels and a higher sFlt1 / PlGF ratio compared with women who remained normotensive postpartum.51 This pattern is identical to that observed in preeclampsia with antepartum onset, leading the authors to hypothesize that women who develop postpartum preeclampsia may represent a group with subclinical preeclampsia that manifests as hypertension postpartum. The majority of women within this cohort (62%) developed postpartum hypertension between 48–72 hours after delivery, with only 5% developing hypertension after 5 days postpartum.51 Whether these imbalances in pro and anti-angiogenic factors are consistent among women who present days to weeks postpartum has not been studied, particularly considering sFLT1 declines rapidly after delivery.52

In contrast, the immune and inflammatory profile at the time of disease seems to differ significantly between postpartum and antepartum preeclampsia.53 The maternal circulating immune profile in women with antepartum preeclampsia has been well-characterized, with a consistently noted increase in T lymphocytes when compared to women with uncomplicated pregnancies.53–55 In addition to an increase in T lymphocytes compared to controls, women with postpartum preeclampsia also have elevated natural killer and natural killer-T cells not seen in women with antepartum preeclampsia.53

Similarly, placental findings from women with postpartum preeclampsia may further inform the etiology of the disease. Placental evidence of maternal vascular malperfusion is the pathognomonic lesion of preeclampsia and is thought to develop secondary to defective trophoblastic invasion and inadequate maternal uterine spiral artery remodeling.56 This impaired transformation of the maternal vessels and the resultant lesions are a common pathologic finding proposed to be secondary to impaired delivery of nutrients and oxygen.56,57 Comparison of placentas from women with early-onset preeclampsia, late-onset preeclampsia and postpartum preeclampsia demonstrates that women with postpartum preeclampsia have similar rates of decidual vasculopathy as women with late-onset preeclampsia and controls.58 This study is limited by its small sample size (<40 placentas per group) and inclusion of women with chronic hypertension, which is known to be associated with an increased frequency of placental lesions.59 Larger-scale studies to fully understand the placental findings among women with postpartum preeclampsia are needed.

Overall, it is clear from the limited data that the etiology of postpartum preeclampsia as well as whether it is a subtype of antepartum preeclampsia remain unanswered.

MATERNAL OUTCOMES

Short-term morbidity

Emerging evidence suggests that the risk of severe maternal morbidity is higher among women with postpartum preeclampsia compared to women with antepartum disease. One recent study utilizing the Nationwide Readmissions Database assessed outcomes among women readmitted with postpartum-onset hypertension compared to women with a hypertensive disorder during pregnancy who were readmitted postpartum.60 While this study is limited by its use of administrative database level data, the authors demonstrated a higher risk of severe maternal morbidity associated with new-onset postpartum hypertension when compared to women with hypertension during pregnancy (12.1% vs. 6.9%, p<0.01). Women with a readmission associated with new-onset postpartum hypertension had a higher risk of eclampsia and stroke. They demonstrate that most cases of eclampsia, stroke and overall severe morbidity associated with postpartum readmissions for hypertension occurred among women without a prior diagnosis of pregnancy-associated hypertension. These findings underscore the potential need for earlier identification of elevated blood pressure among this population, which may allow for closer surveillance and prevention of these morbidities. They also emphasize the importance of education about signs and symptoms of postpartum preeclampsia in all women at the time of discharge from the delivery hospitalization. In addition to indicating serious postpartum morbidity, maternal hospital readmission postpartum is associated with high healthcare costs, disruption of early parenting and increased family burden and is increasingly being tracked as a quality measure with financial implications.61 Finally, it remains of critical importance to continue broader education of other health professionals, such as Emergency Medicine providers, Pediatricians, and primary care providers, who may be front-line providers for postpartum patients, that new-onset hypertension postpartum should be distinguished from underlying pre-pregnancy chronic hypertension, as blood pressure goals and short-term morbidity differ significantly.

Long-term morbidity

The American Heart Association and ACOG have identified hypertensive disorders of pregnancy as risk factors for later-life cardiovascular disease, including chronic hypertension, heart failure and cardiovascular mortality.62–65 Recent high-quality evidence suggests that the risk of chronic hypertension is 30–40% following a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia as soon as 2–7 years postpartum, with an even higher risk observed among women with iatrogenic preterm birth secondary to preeclampsia.66 Whether this risk is the same ais among women with postpartum preeclampsia has not been well-studied. Most longer-term follow up studies do not differentiate the time of onset of preeclampsia (antepartum versus postpartum). One study demonstrated that over one-third of women with postpartum preeclampsia remained on anti-hypertensive agents at their postpartum visit and had significantly higher blood pressure at both the postpartum visit and on longer-term follow up, with 45% of women remaining hypertensive at follow up (median 1.1 years).8 Further studies are needed to assess the risk of future cardiovascular disease among women with postpartum preeclampsia.

Future pregnancy outcomes

To our knowledge, no studies have addressed prevention of postpartum preeclampsia, recurrence risk of postpartum preeclampsia in future pregnancies or management of future pregnancies specifically related to postpartum preeclampsia. Given the overlapping risk factors with antepartum preeclampsia, the authors advocate for a similar approach to that employed among women with a history of antepartum-onset preeclampsia, while acknowledging the lack of evidence in this population. In our practice, we recommend confirmation of normalization of blood pressures in the interpregnancy period. For women with a history of postpartum preeclampsia who remain on anti-hypertensive agents (21% in the aforementioned study)8, we recommend ensuring women are on a medication with a favorable pregnancy safety profile. For women with a history of postpartum preeclampsia, we suggest a baseline assessment of renal and liver function as well as baseline urinary protein assessment depending on other risk factors. We also recommend low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention, while acknowledging that no studies have specifically assessed efficacy in this population. In our experience, there is anecdotal evidence of recurrent postpartum preeclampsia, thus for women who remain normotensive during pregnancy, we typically recommend at least a single blood pressure check in the first week postpartum and close assessment of fluid status prior to discharge from the delivery hospitalization.

RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

Clearly, there remain many unanswered questions in the etiology, diagnosis and management of postpartum preeclampsia, which are outlined in Table 2. As noted above, there is a wide range of the incidence reported in the literature, likely secondary to the fact that women with less severe disease may not present for care and thus may go undetected. Large, prospective postpartum studies among women with uncomplicated pregnancies are needed to document the natural history of blood pressure trajectory delivery, which could inform the true incidence of disease. Such large-scale studies would also allow more complete identification of risk factors and development of risk scores to assist in determination of the need for closer postpartum follow up. The lack of clear definitions from ACOG and others also limits the ability to distinguish whether there may be subtypes of disease or a different disease entity entirely. Identification of which women with postpartum preeclampsia are at highest risk for significant postpartum morbidity would allow for development of evidence-based management algorithms and allow for prospective studies to evaluate algorithms and assess whether they impact postpartum morbidity. For example, it is very likely that not all women with postpartum preeclampsia necessitate hospital re-admission or treatment with magnesium. A more in-depth understanding of disease subtypes, anticipated clinical course, risk factors and biomarkers could facilitate development of evidence-based management algorithms.

Table 2.

Research priorities in postpartum preeclampsia

| Gaps in Knowledge | Proposed Methods and Specific Questions |

|---|---|

| Prospective determination of disease incidence and risk factors | Prospective postpartum BP measurement following uncomplicated deliveries. |

| Telehealth and remote monitoring may be useful to address this gap. | |

| In-depth understanding of etiology and pathophysiology | Prospective biomarker identification both prior to disease onset and at the time of diagnosis. |

| Placenta pathology to evaluate features of vascular malperfusion, if available | |

| Biorepositories may assist in answering these questions. | |

| Development of evidence-based management algorithms. | Prospective studies examining outcomes with varying treatment. |

| Priority should be given to the need for magnesium postpartum as well as the role of specific antihypertensive agents and routine use of diuretics. Determining optimal threshold for acute treatment and targets (for PP). Priority should also be given to development of the most effective strategies for patient and provider education surrounding postpartum preeclampsia recognition and diagnosis. | |

| Understanding risk of recurrence and future pregnancy risk as well as optimal management. | Large-scale multi-center studies will likely be needed to address these questions. |

| Specific questions include the use of low-dose aspirin in future pregnancies and postpartum prophylaxis with home BP monitoring or diuresis in future pregnancies. | |

| Assessing future risk to maternal health. | Clear definitions and classification will aid in determination of future cardiovascular risk. |

| Of particular interest is risk of heart failure among women with postpartum preeclampsia, which is known to be increased among women with preeclampsia with antepartum-onset. |

The authors note that one positive change that may result from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is the increasing implementation of telehealth as an integral part of prenatal care. A component of this is the provision of home blood pressure monitors for BP documentation during pregnancy. With an increasing proportion of the reproductive-aged population having access to self-monitoring devices, we may be able to implement widespread closer BP follow up in first 1–2 weeks postpartum without requiring an in-person visit. Whether this should become standard of care or could be implemented successfully with women at risk for postpartum preeclampsia remains uncertain as prospective studies have not addressed this strategy. The authors suggest a shorter interval follow up or home blood pressure monitoring among women at high-risk of developing postpartum preeclampsia. The use of biomarkers, such as anti and pro angiogenic factors appears to be quite promising in risk prediction, however, whether these factors are useful for women who develop disease beyond 5 days postpartum is less clear. Perhaps biomarkers may provide useful insight into the pathophysiology of postpartum preeclampsia and assist in informing whether it is truly a distinct entity from preeclampsia with antepartum-onset. Further, identification of biomarkers that can predict onset or need for rehospitalization could significantly reduce postpartum morbidity in this population. This should be a research priority in future studies. The use of biorepositories and multi-center approaches will be critical to address these issues. Finally, a more in-depth understanding of short and long-term risk for women with a history of postpartum preeclampsia is needed. Whether the risk of recurrent preeclampsia is similar to women with a history of antepartum preeclampsia has not been studied. Finally, to inform long-term health, further studies are needed to address whether women with postpartum preeclampsia have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

CONCLUSIONS

Postpartum preeclampsia/eclampsia may be associated with a higher risk of maternal morbidity than preeclampsia with antepartum-onset.60 This highlights the need for timely recognition of symptoms and signs by patients as well as obstetric and non-obstetric providers. Postpartum preeclampsia remains a significantly understudied disease process. Studies of delayed-onset postpartum preeclampsia are limited to case reports or small case series.10,67,68 We have outlined here our approach to evaluation and management as well as the most critical questions to be addressed by future research. Like much of the care we deliver in the fourth trimester, postpartum preeclampsia has been under-recognized and overlooked for too long. Understanding the etiology and each postpartum woman’s risk of the disease is imperative for patient care and counseling, anticipatory guidance prior to hospital discharge and is critically important for reduction of maternal morbidity and mortality in the postpartum period.

FUNDING SOURCE:

This work was supported by NIH/ORWH Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) NIH K12HD043441 scholar funds to AH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Data on Pregnancy Complications | Pregnancy | Maternal and Infant Health | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-complications-data.htm#. Published 2019. Accessed February 10, 2020.

- 2.Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. National Vital Statistics Reports Maternal Mortality in the United States : Changes in Coding, Publication and Data Release, 2018. Natl Vital Stat Reports. 2020;69(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clapp MA, Little SE, Zheng J, Robinson JN. A multi-state analysis of postpartum readmissions in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(1):113.e1–113.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(1):e1–e25. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(6):470–475. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magee LA, Pels A, Helewa M, Rey E, von Dadelszen P, Canadian Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP) Working Group. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014;4(2):105–145. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overview | Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management | Guidance | NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng133. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 8.Redman EK, Hauspurg A, Hubel CA, Roberts JM, Jeyabalan A. Clinical Course, Associated Factors, and Blood Pressure Profile of Delayed-Onset Postpartum Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(5):995–1001. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthys LA, Coppage KH, Lambers DS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia: An experience of 151 cases Postpartum period Hypertension Preeclampsia Eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1464–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Safi Z, Imudia AN, Filetti LC, Hobson DT, Bahado-Singh RO, Awonuga AO. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia and eclampsia: Demographics, clinical course, and complications. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1102–1107. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318231934c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACOG. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen WI, Strong JE, Farley JH. Risk factors for late postpartum preeclampsia. J Reprod Med. 2012;57(1–2):35–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takaoka S, Ishii K, Taguchi T, et al. Clinical features and antenatal risk factors for postpartum-onset hypertensive disorders. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2016;35(1):22–31. doi: 10.3109/10641955.2015.1100308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skurnik G, Hurwitz S, Mcelrath TF, et al. Labor therapeutics and BMI as risk factors for postpartum preeclampsia: a case-control study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;10:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.07.142.Labor [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bigelow CA, Pereira GA, Warmsley A, et al. Risk factors for new-onset late postpartum preeclampsia in women without a history of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):338.e1–338.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Safi Z, Imudia AN, Filetti LC, Hobson DT, Bahado-Singh RO, Awonuga AO. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1102–1107. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318231934c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giwa A, Nguyen M. Late Onset Postpartum Preeclampsia 3 Months After Delivery. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(10). doi: 10.1016/J.AJEM.2017.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atterbury JL, Groome LJ, Hoff C, Yarnell JA. Clinical Presentation of Women Readmitted With Postpartum Severe Preeclampsia or Eclampsia. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1998;27(2):134–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02603.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperling JD, Dahlke JD, Huber WJ, Sibai BM. The Role of Headache in the Classification and Management of Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(2):297–302. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stella CL, Jodicke CD, How HY, Harkness UF, Sibai BM. Postpartum headache: is your work-up complete? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(4):318.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berhan Y, Endeshaw G. Clinical and Biomarkers Difference in Prepartum and Postpartum Eclampsia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015;25(3):257–266. doi: 10.4314/ejhs.v25i3.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilchez G, Hoyos LR, Leon-Peters J, Lagos M, Argoti P. Differences in clinical presentation and pregnancy outcomes in antepartum preeclampsia and new-onset postpartum preeclampsia: Are these the same disorder? Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59(6):434. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.6.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Division A THE CALIFORNIA PREGNANCY-ASSOCIATED MORTALITY REVIEW Report from 2002 to 2007 Maternal Death Reviews.; 2018. https://www.cmqcc.org/sites/default/files/CA-PAMR-Report-1%283%29.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2020.

- 24.Oremus M, McKelvie R, Don-Wauchope A, et al. A systematic review of BNP and NT-proBNP in the management of heart failure: overview and methods. Heart Fail Rev. 2014;19(4):413–419. doi: 10.1007/s10741-014-9440-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsai S-H, Lin Y-Y, Chu S-J, Hsu C-W, Cheng S-M. Interpretation and use of natriuretic peptides in non-congestive heart failure settings. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(2):151–163. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.2.151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conti-Ramsden F, Gill C, Seed PT, Bramham K, Chappell LC, McCarthy FP. Markers of maternal cardiac dysfunction in pre-eclampsia and superimposed pre-eclampsia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;237:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rafik Hamad R, Larsson A, Pernow J, Bremme K, Eriksson MJ. Assessment of left ventricular structure and function in preeclampsia by echocardiography and cardiovascular biomarkers. J Hypertens. 2009;27(11):2257–2264. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283300541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malhamé I, Hurlburt H, Larson L, et al. Sensitivity and Specificity of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Diagnosing Heart Failure in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(3):440–449. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ragab A, Goda H, Raghib M, Barakat R, El-Samanoudy A, Badawy A. Does immediate postpartum curettage of the endometrium accelerate recovery from preeclampsia-eclampsia? A randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2013;288(5). doi: 10.1007/S00404-013-2866-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mc Lean G, Reyes O, Velarde R. Effects of postpartum uterine curettage in the recovery from Preeclampsia/Eclampsia. A randomized, controlled trial. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2017;10:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2017.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shields L, Wiesner S, Klein C, Pelletreau B, Hedriana H. Early Standardized Treatment of Critical Blood Pressure Elevations Is Associated With a Reduction in Eclampsia and Severe Maternal Morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(4). doi: 10.1016/J.AJOG.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janzarik WG, Jacob J, Katagis E, et al. Preeclampsia postpartum: Impairment of cerebral autoregulation and reversible cerebral hyperperfusion. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019;17:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.preghy.2019.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 767 Summary: Emergent Therapy for Acute-Onset, Severe Hypertension During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(2):409–412. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vigil-De Gracia P, Ruiz E, López JC, de Jaramillo IA, Vega-Maleck JC, Pinzón J. Management of severe hypertension in the postpartum period with intravenous hydralazine or labetalol: a randomized clinical trial. Hypertens pregnancy. 2007;26(2):163–171. doi: 10.1080/10641950701204430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vermillion S, Scardo J, Newman R, Chauhan S. A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial of Oral Nifedipine and Intravenous Labetalol in Hypertensive Emergencies of Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(4). doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70314-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shekhar S, Gupta N, Kirubakaran R, Pareek P. Oral Nifedipine Versus Intravenous Labetalol for Severe Hypertension During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BJOG. 2016;123(1). doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Gialdini C. Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2018;10(10):CD002252. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002252.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Redman CWG. Hypertension in pregnancy: the NICE guidelines. Heart. 2011;97(23):1967–1969. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cairns AE, Pealing L, Duffy JMN, et al. Postpartum management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018696. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vigil-De Gracia P, Ludmir J. The use of magnesium sulfate for women with severe preeclampsia or eclampsia diagnosed during the postpartum period. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28(18):2207–2209. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.982529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts JM, Druzin M, August PA, et al. ACOG Guidelines: Hypertension in Pregnancy.; 2012. doi:doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mikami Y, Takagi K, Itaya Y, et al. Post-partum Recovery Course in Patients With Gestational Hypertension and Pre-Eclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40(4). doi: 10.1111/JOG.12280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor RN, Roberts JM, Cunningham FG, Lindheimer MD. Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Fourth Edi. Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burlingame J, Yamasato K, Ahn H, Seto T, Tang W. B-type Natriuretic Peptide and Echocardiography Reflect Volume Changes During Pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2017;45(5). doi: 10.1515/JPM-2016-0266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ascarelli M, Johnson V, McCreary H, Cushman J, May W, Martin J. Postpartum Preeclampsia Management With Furosemide: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1). doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000148270.53433.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Perdigao JL, Lewey J, Hirshberg A, et al. LB 4: Furosemide for Accelerated Recovery of Blood Pressure Postpartum: a randomized placebo controlled trial (FoR BP). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222(1):S759–S760. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.1278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736 Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e140–e150. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirshberg A, Sammel M, Srinivas S. Text Message Remote Monitoring Reduced Racial Disparities in Postpartum Blood Pressure Ascertainment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(3). doi: 10.1016/J.AJOG.2019.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hauspurg A, Lemon LS, Quinn BA, et al. A Postpartum Remote Hypertension Monitoring Protocol Implemented at the Hospital Level. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):685–691. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia. Circ Res. 2019;124(7):1094–1112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goel A, Maski MR, Bajracharya S, et al. Epidemiology and Mechanisms of De Novo and Persistent Hypertension in the Postpartum Period. Circulation. 2015;132(18):1726–1733. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saleh L, van den Meiracker AH, Geensen R, et al. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 and placental growth factor kinetics during and after pregnancy in women with suspected or confirmed pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51(6):751–757. doi: 10.1002/uog.17547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brien M-E, Boufaied I, Soglio DD, Rey E, Leduc L, Girard S. Distinct inflammatory profile in preeclampsia and postpartum preeclampsia reveal unique mechanisms. Biol Reprod. 2019;100(1):187–194. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matthiesen L, Berg G, Ernerudh J, Håkansson L. Lymphocyte Subsets and Mitogen Stimulation of Blood Lymphocytes in Preeclampsia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1999;41(3). doi: 10.1111/J.1600-0897.1999.TB00532.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Borzychowski A, Croy B, Chan W, Redman C, Sargent I. Changes in Systemic Type 1 and Type 2 Immunity in Normal Pregnancy and Pre-Eclampsia May Be Mediated by Natural Killer Cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(10). doi: 10.1002/EJI.200425929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parks WT. Placental hypoxia: The lesions of maternal malperfusion. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(1):9–19. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The “great Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ditisheim A, Sibai B, Tatevian N. Placental Findings in Postpartum Preeclampsia: A Comparative Retrospective Study. Am J Perinatol. 2019. doi: 10.1055/S-0039-1692716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bustamante Helfrich B, Chilukuri N, He H, et al. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed associated with hypertensive disorders in the Boston Birth Cohort. Placenta. 2017;52:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wen T, Wright JD, Goffman D, et al. Hypertensive postpartum admissions among women without a history of hypertension or preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(4):712–719. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mogos MF, Salemi JL, Spooner KK, McFarlin BL, Salihu HH. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and postpartum readmission in the United States. J Hypertens. 2018;36(3):608–618. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bellamy L, Casas J-P, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2007;335(7627):974–974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu P, Haththotuwa R, Kwok CS, et al. Preeclampsia and future cardiovascular health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10(2). doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Graves CR, Davis SF. Cardiovascular Complications in Pregnancy: It Is Time for Action. Circulation. February 2018:CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spaan J, Peeters L, Spaanderman M, Brown M. Cardiovascular Risk Management After a Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy. Hypertension. 2012;60(6):1368–1373. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haas DM, Parker CB, Marsh DJ, et al. Association of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes With Hypertension 2 to 7 Years Postpartum. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013092. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bigelow CA, Pereira GA, Warmsley A, et al. Risk factors for new-onset late postpartum preeclampsia in women without a history of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(4):338.e1–338.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Matthys LA, Coppage KH, Lambers DS, Barton JR, Sibai BM. Delayed postpartum preeclampsia: An experience of 151 cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1464–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]