ABSTRACT

Background

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a significant disruption in healthcare delivery and poses a unique long-term stressor among frontline nurses. Hence, the investigators planned to explore the adverse mental health outcomes and the resilience of frontline nurses caring for COVID-19 patients admitted in intensive care units (ICUs).

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional online survey using Google form consisted of questionnaires on perceived stress scale (PSS-10), generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD-7), Fear Scale for Healthcare Professionals regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, insomnia severity index, and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC) were administered among the nurses working in COVID ICUs of a tertiary care center in North India.

Results

A considerable number of subjects in the study reported symptoms of distress (68.5%), anxiety (54.7%), fear (44%), and insomnia (31%). Resilience among the frontline nurses demonstrated a moderate to a high level with a mean percentage score of 77.5 (31.23 ± 4.68). A negative correlation was found between resilience and adverse mental outcomes; hence, resilience is a reliable tool to mitigate the adverse psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Emphasizing the well-being of the nurses caring for critical COVID-19 patients during the pandemic is necessary to enable them to provide high-quality nursing care.

How to cite this article

Jose S, Cyriac MC, Dhandapani M, Mehra A, Sharma N. Mental Health Outcomes of Perceived Stress, Anxiety, Fear and Insomnia, and the Resilience among Frontline Nurses Caring for Critical COVID-19 Patients in Intensive Care Units. Indian J Crit Care Med 2022;26(2):174–178.

Keywords: Anxiety, Coronavirus disease warriors, Coronavirus disease-2019, Fear, Frontline nurses, Insomnia severity, Mental health outcomes, Resilience, Stress

INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in China in December 2019 has ruthlessly affected almost all countries. It has imposed enormous morbidity and mortality burden by infecting more than 20 million and 700,000 deaths globally. This pandemic had severely disrupted the public health system and posed a significant threat to economies worldwide.1–3

Nurses play a significant role in controlling pandemics by directly being involved in managing patients for a longer duration. Still, this job nature of nurses put them at an increased risk of COVID-19 infection. Evidence from the previous infectious respiratory disease and other studies on COVID-19 epidemics reflects serious concern among nurses for personal and family health due to the direct contact with the life-threatening virus. The mental health burden of the healthcare workers is aggravated by the increased confirmed and suspected cases of COVID-19 infection, in addition to that overwhelming workload, lack of specific drugs, depletion or unavailability of personal protective equipment (PPE), sensational media coverage of COVID-19, societal abuse, stigma toward the healthcare workers, etc.3–5 This resulted in a higher rate of attrition and reluctance to work or contemplate resignation among the healthcare workers.

The physical strain and isolation, separation from the family, constant vigilance on the infection control measures, and the fear of contracting infection also contribute to their mental health burden.4–6 These critical situations prevalent in the care and management of COVID-19 patients place the frontline nurses at risk for developing adverse psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, psychological distress, and insomnia. These could, in turn, lead to poor work performance, impaired cognition, poor vigilance, impaired clinical judgment, and reduced motor skills.5,7

Psychological resilience is a personality quality, having protective effects against burnout, it's the ability of an individual to bounce back or recover from adverse circumstances, but in the present unprecedented stressful event of a pandemic, due to the lack of social support, prolonged isolation, fear of infecting family and friends’ resilience may get affected.8

So the investigators planned to evaluate the magnitude of the various adverse mental health outcomes; perceived stress, anxiety, fear, and insomnia among the nurses working for critical COVID-19 patients and their resilience and the effect of psychological resilience on these mental health outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Research Design and Participants

A web-based cross-sectional survey was conducted using Google form shared through WhatsApp of the 150 frontline nurses randomly selected from the list of nurses posted in COVID-19 intensive care units (ICUs) of a tertiary care center in Chandigarh in September 2020.

Instruments

After a thorough literature search, researchers selected appropriate standardized tools with high validity and reliability and used the original English version in the study.

The online Survey questionnaire consisted of:

1. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), consisted of 10 direct queries assessing the current levels of stress experienced by the participants using a Likert scale, ranging from never (0) to very often (4). Score = 0–13, no or mild stress; 14–26 = moderate stress, and 27–40 as severe perceived stress. Cronbach's alpha value for PSS-10 was 0.78 in this study.

2. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), consists of seven items; the items are assigned with a score ranging from 0 to 3 to the response categories of “not at all,” “several days,” “more than half the days,” and “nearly every day,” respectively. The reported Cronbach's alpha value for GAD-7 was 0.87 in this study.

3. Fear Scale for Healthcare Professionals regarding COVID-19 Pandemic, the scale consisted of nine items that assessed nurses’ fear in three main areas, namely, fear regarding infection, insecurity due to death, and instability in the work environment (fear of isolation, assignment to COVID hospital, societal stigma). We instructed the participants to answer each item on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, where 0 = definitely false and 3 = definitely true. Cronbach's alpha value obtained for this scale was 0.78 in this study.

4. Insomnia Severity Index, a 7-item screening tool to assess sleep pattern problems using a 4-point Likert scale. A total score of 0–7 indicates “no clinically significant insomnia,” 8–14 as “sub-threshold insomnia,” 15–21 is “clinical insomnia (moderate severity),” and 22–28 “clinical insomnia (severe).”

5. The Connor Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC), a 10-item 5-point Likert scale (0 = not true at all, 4 = true all the time) to measure resilience or capacity to change and adjust with adversity was used. Cronbach's alpha score for this tool in the study was 0.8.

Data Collection Procedure

The participants have explained the objectives of the study through telephone. The investigators sent Google form through WhatsApp of all the selected frontline nurses on quarantine after seven days of duty. We got 91% responses from the participants with reminders, and we only considered the responses complete in all aspects for analysis. The investigators assured anonymity and confidentiality of collected data and data stored in Google Drive, secured it with the password.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected were analyzed with Google spreadsheet and SPSS version 22.0. Demographics were reported using descriptive statistics, and an inferential statistics t-test was used to compare means between the demographic variables.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 137 frontline nurses who participated, the mean age was 30.4 (SD: 3.3) years, most of the respondents (53.3%) were females, and 86% of the nurses who participated were Bachelors in Nursing.

Table 1 depicts that 51.10% of the respondents were above 30 years old, and 75% of the nurses in the study had more than 5 years of clinical experience. The majority of the nurses in the survey were confident in self-protection against COVID-19 infection during clinical practice.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of frontline nurses caring COVID-19 patients in intensive care units of COVID hospital (n = 137)

| Variables | Mean ± SD or frequency |

|---|---|

| Age | 30.36 ± 3.3 |

| 20–30 | 67 (48.90%) |

| 31–40 | 70 (51.10%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 73 (53.3%) |

| Male | 64 (46.7%) |

| Marital status | |

| Currently single | 44 (32.10%) |

| Married | 93 (67.9%) |

| Educational level | |

| Diploma in nursing | 17 (12.4%) |

| Basic/postbasic in nursing | 117 (85.4%) |

| Postgraduation in nursing | 3 (2.2%) |

| Having children | |

| Yes | 76 (55.5%) |

| No | 61 (44.5%) |

| Number of members in household | |

| Alone | 25 (18.2%) |

| 2–4 | 92 (67.2%) |

| >5 | 20 (14.6%) |

| Years of experience in nursing profession | 8 ± 4.25 |

| 1–5 | 32 (23.40%) |

| 6–10 | 71 (51.80%) |

| >11 | 34 (24.80%) |

| Perception of workplace safety in caring COVID-19 patients | |

| Safe | 101 (73.7%) |

| Unsafe | 36 (26.3%) |

| Confidence in self-protection | |

| Confident | 125 (91.20%) |

| Unconfident | 12 (8.8%) |

Participants’ Mental Health Outcomes

A considerable number of the participants reported adverse psychological outcomes with symptoms of distress (68.5%), anxiety (54.7%), fear (44%), and insomnia (31%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mental health outcomes of frontline nurses caring COVID-19 patients in intensive care units (n = 137)

| Mental health outcomes | Mean ± SD or frequency |

|---|---|

| Anxiety (GAD scale) | 6.48 ± 2.96 |

| No anxiety (0–5) | 62 (45.3%) |

| Mild anxiety (6–10) | 61 (44.5%) |

| Moderate anxiety (11–15) | 13 (9.5%) |

| Severe anxiety (16–21) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Perceived stress (PSS-10) | 17.34 ± 5.57 |

| Mild distress (0–13) | 43 (31.4%) |

| Moderate distress (14–26) | 90 (65.7%) |

| Severe distress (27–40) | 4 (2.9%) |

| Fear (FS-HPs) | 11.75 ± 4.26 |

| No fear (0–5) | 10 (7.3%) |

| Mild fear (6–16) | 67 (48.9%) |

| Moderate fear (17–27) | 54 (39.4%) |

| 67 (48.9%) | 6 (4.4%) |

| Severity of insomnia (ISI) | 6.66 ± 3.43 |

| No clinically significant insomnia (0–7) | 95 (69.3%) |

| Sub threshold insomnia (8–14) | 38 (27.7%) |

| Clinical insomnia: moderate severity (15–21) | 4 (2.9%) |

Resilience of the Frontline Nurses Caring for Critical COVID-19 Patients

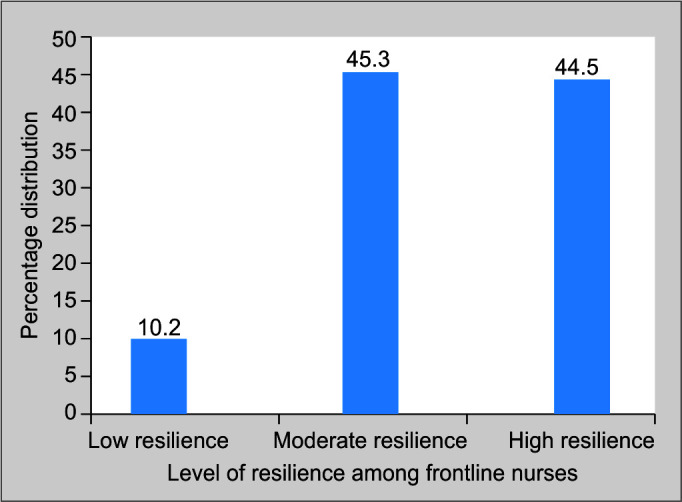

The nurses in ICUs caring for COVID patients expressed a high level of resilience with a mean score of 31.23 ± 4.68 (out of 40).

Figure 1 shows that the participants in the study had a significantly high level of resilience; 89.8% scored more than 50% (>20) on the CD-RISC-10 scale.

Fig. 1.

Level of resilience among frontline nurses caring for critical COVID-19 patients

Table 3 shows that the mean score for perceived stress was significantly higher among female frontline nurses and those with <5 years of clinical experience. The severity of insomnia was higher among those in higher age groups, those who are not confident in self-protection, and who perceived workplace unsafe against the spread of COVID-19 infection.

Table 3.

Differences in mental health impacts among various sociodemographic characteristics of frontline nurses caring COVID 19 patients in intensive care units (n = 137)

| Perceived stress | Anxiety | Fear | Severity of insomnia | Resilience | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | Mean ± SD | t value (p) | Mean ± SD | t value (p) | Mean ± SD | t value (p) | Mean ± SD | t value (p) | Mean ± SD | t value (p) |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male | 16.43 ± 6.55 | 1.781* | 6.42 ± 2.75 | 0.240 | 11.70 ± 4.82 | 0.125 | 7.09 ± 3.88 | -1.378 | 30.98 ± 5.06 | 0582 |

| Female | 18.12 ± 4.44 | (0.05) | 6.54 ± 3.19 | (0.811) | 11.79 ± 3.75 | (0.901) | 6.28 ± 2.94 | (0.170) | 31.45 ± 4.33 | (0.561) |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 20–30 years | 18.04 ± 5.18 | 1.463 | 6.70 ± 2.93 | 0.85 | 11.61 ± 4.17 | 0.125 | 6.08 ± 3.18 | 1.940* | 30.83 ± 4.94 | 0.973 |

| 31–40 years | 16.65 ± 5.87 | (0.146) | 6.27 ± 2.98 | (0.397) | 11.88 ± 4.38 | (0.901) | 7.21 ± 3.58 | (0.05) | 31.61 ± 4.41 | (0.332) |

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Married | 17.13 ± 4.88 | 0.2s81 | 6.62 ± 2.71 | 0.419 | 11.20 ± 4.73 | 0.987 | 6.16 ± 3.35 | 1.169 | 30.98 ± 4.67 | 0.871 |

| Other marital status | 17.43 ± 5.91 | (0.779) | 6.39 ± 3.08 | (0.676) | 11.98 ± 4.06 | (0.325) | 6.90 ± 3.46 | (0.244) | 31.74 ± 4.74 | (0.385) |

| Having children | ||||||||||

| Yes | 17.35 ± 5.48 | 0.046 | 6.48 ± 3.00 | 0.22 | 12.21 ± 4.25 | 1.409 | 7.02 ± 3.50 | 1.385 | 31.47 ± 4.16 | 0.669 |

| No | 17.31 ± 5.72 | (0.964) | 6.47 ± 2.92 | (0.982) | 11.18 ± 4.24 | (0.161) | 6.21 ± 3.30 | (0.168) | 30.93 ± 5.26 | (0.505) |

| Education | ||||||||||

| Diploma in nursing | 17.27 ± 5.38 | 0.496 | 5.47 ± 2.12 | 1.508 | 11.83 ± 4.17 | 0.223 | 6.8 ± 3.50 | 1.368 | 31.41 ± 4.81 | 1.152 |

| Bachelor in nursing or higher | 18 ± 7.23 | (0.621) | 6.63 ± 3.06 | (0.134) | 11.58 ± 5.17 | (0.824) | 5.58 ± 2.93 | (0.174) | 30 ± 3.93 | (0.251) |

| Experience in nursing profession | ||||||||||

| <5 years | 21.8 ± 1.30 | 2.242 | 5.96 ± 2.55 | 1.440 | 11.81 ± 3.56 | 0.489 | 8.60 ± 4.56 | 1.557 | 26 ± 0.707 | 3.535** |

| >6 years | 16.55 ± 5.05 | (0.045) | 6.85 ± 3.10 | (0.152) | 13.11 ± 5.32 | (0.634) | 5.55 ± 2.83 | (0.145) | 33.33 ± 4.52 | (0.004) |

| Confidence in self-protection | ||||||||||

| Confident | 17 ± 5.6 | 2.255* | 6.45 ± 2.98 | 0.327 | 11.60 ± 4.35 | 1.276 | 6.48 ± 3.41 | 2.055* | 31.45 ± 4.35 | 1.811 * |

| Unconfident | 20.75 ± 4 | (0.026) | 6.75 ± 2.76 | (0.744) | 13.25 ± 3.10 | (0.204) | 8.58 ± 3.08 | (0.042) | 28.91 ± 3.98 | (0.05) |

| Perception of workplace safety | ||||||||||

| Safe | 16.98 ± 5.88 | 1.254 | 6.604 ± 2.99 | 0.808 | 11.52 ± 4.46 | 1.043 | 6.32 ± 3.43 | 2.010* | 31.51 ± 4.55 | 0.240 |

| Unsafe | 18.33 ± 4.49 | (0.212) | 6.138 ± 2.88 | (0.420) | 12.38 ± 3.65 | (0.299) | 7.63 ± 3.27 | (0.046) | 30.44 ± 4.98 | |

Significant at 0.05;

Significant at 0.0

Table 4 shows that resilience had a significant negative impact on stress, anxiety, and fear; however, the correlation coefficient values were between 0.2 and 0.5.

Table 4.

Relation among the mental health outcomes of frontline nurses caring COVID-19 patients in North India (n = 137)

| Resilience | Stress | Anxiety | Fear | Severity of insomnia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | — | −0.453** | −0.414** | −0.230** | −0.100 |

| Stress | — | 0.656** | 0.314** | 0.063** | |

| Anxiety | — | 0.200** | 0.109 | ||

| Fear | — | 0.135* |

Significant at 0.05,

Significant at 0.01

DISCUSSION

Mental health problems among health workers affect their understanding, attention, and decision-making capacities, which hinder the quality of healthcare services to society. These mental health outcomes can also have a long-lasting impact on the overall well-being of healthcare workers.

In the present study among 137 frontline nurses, 55% reported mild to moderate anxiety while caring for COVID-19 patients, but compared to previous studies conducted in Wuhan among the healthcare professionals,9 and the pooled prevalence identified by Pappa et al.,10 the incidence of anxiety among frontline nurses in our study was relatively higher. As the number of cases increased and the lack of control on the spread of infection in the country and the cross-transmission among health workers resulted in reporting of moderate to a high level of perceived stress (68%), similar findings were echoed in studies where more than half had moderate to severe levels of perceived stress.9 In a survey during the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak,11 nurses started to develop burnout and deteriorated the standard of care provided after prolonged and sustained exposure to the stressors, so there is a need to curb stress among the frontline nurses through appropriate stress management and organizational supports.

Our findings indicate that women reported more severe stress; similar results were evidenced in the previous studies.4,10 This study found a significant difference in mean scores of perceived stress among those who had clinical experience less than 5 years and were unconfident in self-protection against COVID-19 infection. The result of the study is congruent with a study conducted among the frontline nurses in Wuhan, China, in the early pandemic.12

Almost all the nurses in the frontline feared that they would be infected with COVID-19, but they were equally worried about infecting family members. The findings of the study are consistent with the survey conducted among the dental practitioners, and they expressed a fear of being infected by their patients or coworkers,13 and similar results were recorded by Maunder et al. among health workers during the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak.14

In this study, 30% of the participants had experienced subthreshold to moderate levels of insomnia, a similar result seen in a comparative study conducted in the early phase of the epidemic in China. The study identified that healthcare workers (23.6%) were more likely to have poor sleep quality.15 A meta-analytical study conducted among Chinese health workers calculated the pooled prevalence as 34.32%. The nurses’ job nature also made them more prone to have circadian rhythm dysfunctions induced by irregular and frequent night shifts. The severity of insomnia scores was significantly higher among the older age groups (>30 years), the age intensifies the intensity of anxiety and abnormal parasympathetic activity, and increase age affected considerably by the sleep problems due to shift work disorder.16 Lack of confidence in self-protection against COVID-19 infection and the perception of an “unsafe” workplace were the other factors that aggravated insomnia among the frontline nurses.

The present study showed a moderate to high level of resilience with an average total score of 31.23 (SD 4.68), scoring higher for resilience for nurses in a survey conducted by Hegney et al.,8 and another study conducted in Hunan in China showed a similar level of resilience for nurses.17

A significant negative correlation was found between resilience and mental health outcomes (stress, anxiety, and fear). This finding is consistent with previous studies,4,8,18 so better resilience experiences good mental health outcomes.

The resilience of the nurses is found to be higher among those who had higher clinical experience (>5 years) and those who were confident in self-protection against COVID-19 infection. The resilience may be enhanced among the frontline nurses through online mindfulness training and organizational support through a good working environment. The hospital administration should address measures to maintain and improve individual traits and administrative supports to build resilience, thus improving nurses’ mental health.19

CONCLUSION

The present study showed a remarkable rate of mental health problems of perceived stress, anxiety, fear, and insomnia among the COVID ICUs nurses. The result of the present study immediately warrants the need for developing interventions aimed at enhancing the resilience among the nurses to combat a crisis like COVID-19.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ORCID

Sinu Jose https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7056-191X

Maneesha C Cyriac https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2697-0684

Manju Dhandapani https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3351-3841

Aseem Mehra https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5427-0247

Navneet Sharma https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5707-9686

REFERENCES

- 1.Euro surveillance editorial team. Note from the editors: World Health Organization declares novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) sixth public health emergency of international concern. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(5):1–2. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.5.200131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maben J, Bridges J. Covid‐19: supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2742–2750. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly M. The pandemic's psychological toll: an emergency physician's suicide. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3):A21–A24. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jose S, Dhandapani M, Cyriac MC. Burnout and resilience among frontline nurses during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in the emergency department of a tertiary care center, North India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(11):1081–1088. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jose S, Cyriac MC, Dhandapani M. Health problems and skin damages caused by personal protective equipment: Experience of frontline nurses caring for critical COVID-19 patients in Intensive care units. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(2):134–139. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and March 2020 during the outbreak of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hegney DG, Rees CS, Eley R, Osseiran-Moisson R, Francis K. The contribution of individual psychological resilience in determining the professional quality of life of Australian nurses. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1613. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du J, Dong L, Wang T, Yuan C, Fu R, Zhang L, et al. Psychological symptoms among frontline healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;67:144–145. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Vassilis GG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang HS, Son YD, Chae SM, Corte C. Working experiences of nurses during the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak. Int J Nurs Pract. 2018;24(5):e12664. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu D, Kong Y, Li W, Han Q, Zhang X, Zhu LX, et al. Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: a large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21(100424):48. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmed MA, Jouhar R, Ahmed N, Adnan S, Aftab M, Zafar MS. Fear and practice modifications among dentists to combat novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2821. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, Bennett J, Peladeau N, Leszcz M, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168(10):1245–1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CL, Wu MP, Ho CH, Wang JJ. Risks of treated anxiety, depression, and insomnia among nurses: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo YF, Cross W, Plummer V, Lam L, Luo YH, Zhang JP. Exploring resilience in Chinese nurses: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(3):223–230. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(5):412–420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh D. Occupational risks for COVID-19 infection. Occup Med (Lond) 2020;70(1):3–5. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]