Abstract

Dengue disease has become a major public health problem. Accurate and precise identification, prediction and mapping of high-risk areas are crucial elements of an effective and efficient early warning system in countering the spread of dengue disease. In this paper, we present the fusion area-cell spatiotemporal generalized geoadditive-Gaussian Markov random field (FGG-GMRF) framework for joint estimation of an area-cell model, involving temporally varying coefficients, spatially and temporally structured and unstructured random effects, and spatiotemporal interaction of the random effects. The spatiotemporal Gaussian field is applied to determine the unobserved relative risk at cell level. It is transformed to a Gaussian Markov random field using the finite element method and the linear stochastic partial differential equation approach to solve the “big n” problem. Sub-area relative risk estimates are obtained as block averages of the cell outcomes within each sub-area boundary. The FGG-GMRF model is estimated by applying Bayesian Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation. In the application to Bandung city, Indonesia, we combine low-resolution area level (district) spatiotemporal data on population at risk and incidence and high-resolution cell level data on weather variables to obtain predictions of relative risk at subdistrict level. The predicted dengue relative risk at subdistrict level suggests significant fine-scale heterogeneities which are not apparent when examining the area level. The relative risk varies considerably across subdistricts and time, with the latter showing an increase in the period January–July and a decrease in the period August–December.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10109-021-00368-0.

Keywords: Dengue disease, Relative risk, Fusion area-cell generalized geoadditive-Gaussian Markov random field model, Bayesian statistics, “Big n, Problem, Bottom-up approach

Introduction

Dengue disease is a major challenge to healthcare worldwide, potentially leading to death, especially among the poor in low- and middle-income countries (Ak et al. 2018). In addition, there are latent costs related to stress, productivity loss, school absence, and care taking (Wilastonegoro et al. 2020). To reduce health impacts and treatment costs, there have been substantial efforts aimed at the prevention of dengue disease outbreaks (Kampen et al. 2014). For these purposes, statistical models aimed at identifying the causes, transmission mechanisms, and prediction of outbreaks at a fine spatiotemporal scale are of crucial importance (Messina et al. 2019).

High-resolution information is needed for research on the etiology of the disease and the development of control and prevention strategies (Ak et al. 2018; Jaya et al. 2017; Jaya and Folmer 2020, 2021a, b; Pokharel and Deardon 2016). Dengue disease typically involves a spatiotemporal pattern (Jaya and Folmer 2020, 2021a, b; Phanitchat et al. 2019; Puggioni et al. 2020); therefore, high-resolution spatiotemporal models and maps of the distribution of relative risk are basic elements of an early warning system aimed at identifying where and when an outbreak will occur (Hanigan et al. 2019; Shi et al. 2013; Xu et al. 2019).

In many areas of spatial research including epidemiology, data are often only available at different levels of aggregation (Moraga et al. 2017; Shi et al. 2013; Utazi et al. 2019). If low-resolution information is available whereas high-resolution (cell level) information is needed but lacking, area-to-cell disaggregation through joint area-cell estimation can be applied to obtain the missing information (Moraga et al. 2017; Utazi et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018a).1 Data fusion or data assimilation (Banerjee et al. 2015) and Bayesian melding (Fuentes and Raftery 2005; Liu et al. 2011) are terms used to denote integrating multiple data sources of different spatial resolutions.2 The basic concept involves combining area and cell observations in a single statistical model. Combining data measured at different levels of aggregation can improve parameter estimation and increase prediction accuracy (Wang et al. 2018b). However, it may lead to spatial misalignment (Moraga et al. 2017; Sahu et al. 2010; Truong et al. 2014; Utazi et al. 2019), which induces biased or inconsistent estimators (Liu and Bertazzon 2016; Peng and Bell 2010; Saez and López-Casasnovas 2019).

Several kinds of correction approaches based on regression models have been developed to deal with area-to-cell misalignment problems (Banerjee and Gelfand 2002; Banerjee et al. 2015). Moraga et al. (2017) and Utazi et al. (2019) applied Bayesian geostatistical analysis to deal with misalignment in spatial non-Gaussian data with linear covariates. However, methods that address area-to-cell misalignment in spatiotemporal non-Gaussian data with nonlinear covariates are less well known. This applies especially to Poisson or Negative Binomial (NB) spatiotemporal data, which are typically applied in dengue and other disease incidence modeling, but also in other kinds of spatial and regional research.

In this paper, we introduce the Fusion Area-Cell Spatiotemporal Generalized Geoadditive (GG)-Gaussian Field (GF) model, abbreviated as FGG-GF model, to generate high-resolution (cell) predictions based on observations at lower (area) resolution of the variable of interest (i.e., the number of dengue incidences) and the population at risk, and high-resolution cell data (i.e., weather variables), while controlling for misalignment. Moraga et al. (2017) and Utazi et al. (2019) have shown that the prediction performance of integrated area-cell models can outperform models that use single level data sources.

Kammann and Wand (2003) introduced the Generalized Geoadditive Model (GGM), which has become popular in disease mapping (among other fields) because of its suitability for making high-resolution maps (Muleia et al. 2020; Wand et al. 2011). The model assumes that there is a spatially continuous variable underlying all observations which can be modeled using a Gaussian process, usually denoted Gaussian Field (GF). A GF is characterized by a first-order autoregressive model with spatially correlated innovations. The GGM combines the Generalized Additive Model (GAM) and the Geostatistical Model (GM). The former was introduced by Hastie and Tibshirani (1986) to provide a flexible means of handling nonlinear and interacting covariates. GAMs are also suitable for handling complex spatial and temporal autocorrelation (French and Wand 2004; Ma et al. 2014). GAMs are nonparametric because they do not require a priori specification of the regression function (Wang et al. 2018a). The GM was introduced by Matheron (1963) to construct high-resolution maps over a particular geographical region based on cell data on (risk) factors associated with a (dependent) variable of interest.

The integrated area-cell observations and the combination of non-Gaussian data, a nonlinear predictor and latent model components, in particular the spatiotemporal GF, make estimation of FGG-GF model, prediction, and mapping computationally complex and time-consuming (Barber et al. 2016) because of the “big n” problem. This issue can be handled by transforming a GF with a dense covariance matrix to a Gaussian Markov Random Field (GMRF) with a sparse precision matrix3 of Matérn covariances (Lindgren et al. 2011).

The objective of this paper is to develop a high-resolution prediction and mapping procedure for spatiotemporal Poisson or Negative Binomial data applying a Fusion Area-Cell Spatiotemporal Generalized Geoadditive-Gaussian Markov Random Field (abbreviated as FGG-GMRF) model. Inference and prediction are handled in a Bayesian framework. The approach will subsequently be applied to dengue disease risk in Bandung city, Indonesia. The purpose is to predict and map the relative dengue risk at subdistrict level, given observations on dengue incidence and population at risk at district level and weather risk factors at cell level.4 Special attention is paid to high-risk districts and subdistricts requiring public intervention (Aguayo et al. 2020).

The structure of the remainder of this paper is as follows. Section 2 introduces the spatiotemporal GG-GF model. Section 3 presents the FGG-GF and FGG-GMRF models and the Bayesian inference framework. The link between the GF and GMRF models is summarized in Appendix 1. Section 4 applies the methodology to dengue incidence in Bandung city, Indonesia, and Sect. 5 summarizes and concludes the conducted research.

The spatiotemporal generalized geoadditive-Gaussian field model

Consider region , partitioned into areas (e.g., districts in a city), each measured for periods. The areas are labeled , where denotes area at time for and . Region is further divided into a finite set of cells for periods. The set of cells over periods is denoted with denoting the number of cells in area for and . Note that the notation will be used to explicitly denote that cell belongs to area . If the area is not relevant, will be used. Moreover, the notation for will be incidentally used if there is no risk of misunderstanding. Finally, and denote the latitude and longitude coordinates of its centroid, respectively.

Let and denote the number of (dengue) incidences and population at risk in area at time , respectively, and and the number of (dengue) incidences and population at risk in cell at time , respectively. Note that both and are unobserved at the cell level. and are assumed to follow Poisson distributions5 with means and , respectively, with and denoting the expected number of (dengue) incidences and and the relative (dengue) risk for area and cell at time , respectively (Jaya and Folmer 2020. The expected rate is calculated using external standardization. It is defined based on the overall average across all areas and periods (Abente et al. 2018; Jaya and Folmer 2020, 2021a, b):

| 1 |

The relative risk is defined as the ratio of the local risk in a spatiotemporal unit relative to the average risk across the whole study region over the entire time period (Yin et al. 2014). It is centered around one, meaning that the total number of incidences is equal to the expected rate. The maximum likelihood (ML) estimator of the relative risk is (Jaya et al. 2017; Jaya and Folmer 2020):

| 2 |

This is known as the crude risk or the standardized incidence ratio (SIR).

Following Moraga et al. (2017), Jaya and Folmer (2020, 2021a, b), and Utazi et al. (2019), we model the relative risk as a non-separable Poisson log-linear model as follows6:

| 3a |

| 3b |

with and .

In Eqs. (3a) and (3b), is the overall intercept denoting the average risk across space and time, i.e., across all , , and . The latent7 functions and for , represent the (non)linear effects of the metrical area and cell risk factors, respectively. The risk factors at cell level for a given area and time are fixed. However, they vary across areas and times. The latent (non)linear risk factor functions are based on observations at cell level but are predicted at area level. The risk at cell and area levels are assumed to be driven by the same factors; therefore, we adopt joint risk factor functions. For this purpose, we stack the observations on the risk factors such that risk factor , at both area and cell level, becomes for and latent function . The functions are commonly centered at the mean, i.e., for identifiability reasons (Fahrmeir and Lang 2001).

Let be the sum of the functions for :

| 4 |

To account for spatiotemporal variation, Eq. (4) can be extended to a varying coefficients model8:

| 5 |

where the design vector contains components of or additional covariates. The vector , modifies the relationship between the covariate and the log-linear conditional expectation . If it is identical to the vector 1, i.e., with dimension (, then presents the overall (main) effect of If it is different from presents the effect of that varies along with . In other words, models the interaction between and (Fahrmeir and Lang 2001). According to Martınez-Bello et al. (2017a; b), the varying coefficients model helps refine the association between the regressors (e.g., the weather variables) and the response, thus improving predictions at a fine spatiotemporal scale. For example, if denotes the calendar day and is the spatiotemporal covariate temperature, then represents the temperature effect varying by day. In this study, we apply the temporally varying coefficients model to accommodate the temporally varying nonlinear effects of risk factors on the response. The time-varying effect of, for example, the -th covariate can be written as (Franco-Villoria et al. 2019):

| 6 |

where for is the time-varying regression coefficient, which can be regarded as a stochastic process over (Fahrmeir and Lang 2001). For ease of notation, we ignore the term and write .

A time-varying coefficient can be conveniently specified as the sum of a fixed (global mean) effect and a temporal random effect of the risk factor: for and . The fixed effect () presents the effect of the risk factor that remains constant across space or time, while the temporal random effect ( accounts for the time-varying effect of the risk factor (Song et al. 2020). The temporal random effect can be conveniently specified as a random walk model of order one (RW1) or two (RW2)9 (Bernardinelli et al. 1995; Martinez-Bello et al. 2017b; Schrödle and Knorr-Held 2011):

| 7 |

with white noise, and denoting the variance of the RW process controlling the smoothness of . A random walk process of order one needs an initial value of and a random walk of order two needs initial values of and .

The components and are the spatially structured and unstructured main effects at area level, respectively, whereas and denote the spatially structured and unstructured main effects for cell in the area to which it belongs. The components and are the temporally structured and unstructured main effects. For a given time they are equal for all areas and cells. represents the spatiotemporal interaction effect of the unobserved risk factors at area level and the impact of the interaction effect in cell in area to which it belongs (see Sect. 3.1 for details). We consider four type of space–time interactions (see Table 5 in Appendix 2).

Table 5.

Priors, joint priors and hyperpriorsa

| Component | Prior | Joint prior | Hyperprior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Exchangeable Gaussian processb | for every and . A vague Gaussian prior with zero mean and a large variance |

for every and with |

– |

| Global effects of the risk factors | Exchangeable Gaussian process | for every and and A vague Gaussian prior with zero mean and a large variance | for every and where and with for | – |

| Temporal random effects of the risk factorsc | Random walks of order one (RW1) or order two (RW2) |

RW1: for with for every and |

for every and, for with and the ( precision matrix of the parameters given by with the ( temporal structure matrix. For the RW1 model, is:

|

Inverse Gamma (IG) with shape and scale parameters 1 and 0.01, respectively, i.e., |

|

RW2: for with for every and |

For the RW2 model, is:

The joint prior of , is:

|

|||

| Spatially structured random effect | Leroux Conditional Autoregressive ( |

for every and with

and the () binary spatial weights matrix characterizing the neighborhood structure of the areas, e.g., an inverse distance matrix or a contiguity matrix and the spatial autoregressive coefficient |

for every , with and the precision matrix with , and the ( spatial structure matrix, with the th element defined as:

where is the number of neighbors in region , and denoting that areas and are neighbors |

Half Cauchy (HC) with scale parameter 25 for i.e., and

|

| Spatially unstructured random effect | Exchangeable (iid) Gaussian process | for every and |

for every , with and the precision matrix, the identity matrix and |

|

| Temporally structured random effect | Autoregressive of order one (AR1) |

, for every and and , with the autoregressive parameter and |

for every and , with and the precision matrix with , and the ( temporal structure matrix for the prior:

|

|

| Temporally unstructured random effect | Exchangeable (iid) Gaussian | for every and and |

for every and , with and the precision matrix with and the ( identity matrix |

|

| Area level Interaction effect | Type I: combines the spatially unstructured () and temporally unstructured random effects. Implies and |

where with independent over space and time for and . the precision matrix with and structure matrix with the ( identity matrix and the Kronecker product |

and | |

| Type II: combines the spatially unstructured and the temporally structured random effects. Implies and |

where with following an AR1, independently distributed for all areas. the precision matrix with and structure matrix |

and | ||

| Type III: combines the temporally unstructured and the spatially structured random effects. Implies and |

where with for following a Leroux CAR, independently distributed for all periods. the precision matrix with and structure matrix |

HC prior with scale parameter 25 for , and | ||

| Type IV: combines the spatially ( and temporally structured () random effects. Implies and |

where with for and dependent over space and time. the precision matrix with and structure matrix |

HC prior with scale parameter 25 for , and | ||

| Cell level Gaussian Field through LSPDE model |

for . I Initial value |

with and the precision matrix with the -dimensional precision matrix of the (AR1) process and the () spatial precision matrix of the GMRF |

Penalized complexity (PC) distribution for and i.e., and , respectively | |

aTable 5 is partly based on Jaya and Folmer (2021a)

bAn exchangeable (Gaussian) process is a sequence of random variables that are independent and identically (normal) distributed

cScaling is applied to the temporal structure matrices of RW1 and RW2 to make their marginal variances comparable. Scaling is implemented in R-INLA by using the option scale.model = TRUE

The final component, in Eq. (3b) is the spatiotemporal GF in cell at time , indicating the true but unobserved relative risk (Cameletti et al. 2013; Godana et al. 2019). Hence, is the “own” spatiotemporal interaction effect of cell . Because of the large number of cells, it is continuously indexed (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015). The component in Eq. (3a) denotes the area average of across the cells within . Following Cameletti et al. (2013) and Godana et al. (2019), we assume that changes over time following a first-order autoregressive (AR1) process with coefficient :

| 8 |

with defined as a mean square differentiable process10 (Stein 1999) with the temporally independent but spatially correlated innovations following a zero-mean Gaussian distribution with spatiotemporal covariance function:

| 9 |

for is the homogeneous variance of , i.e., for every and , and the spatial autocorrelation matrix as a function of the distance between and at time (e.g., the Euclidean distance). Under the assumption that the covariance function only depends on , it is a Matérn covariance function satisfying the second-order stationarity and isotropy assumptions. Consequently, the mean of the process is constant and only depends on the locations of and through the Euclidean distance (Song et al. 2008). The spatial autocorrelation function is defined as:

| 10 |

where is the gamma function, the modified Bessel function of the second order (Abramovitz and Stegun 1965) and the parameter controlling the smoothness of the GF (smoothness parameter). In applications, is commonly fixed because it is usually poorly identified (Miller et al. 2019; Utazi et al. 2019). In several software packages, including R-INLA (Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation), the default value is = 1), corresponding to moderate smoothness (Lindgren et al. 2011; Utazi et al. 2019). The scale parameter controls the rate of decay of the correlation and is inversely related to the range parameter of the Euclidean distance between and For large , goes to zero. Because of a lack of a simple relationship between and , Lindgren et al. (2011) proposed the empirically derived relationship for spatial autocorrelation near 0.1. Substituting Eq. (10) in Eq. (9), the spatiotemporal Matérn covariance function for each time is:

| 11 |

For the joint latent spatiotemporal GF at cell level, we have:

| 12 |

with a Matérn covariance matrix. That is, the joint latent spatiotemporal GF is a second-order stationary, isotropic GF with Matérn covariance function Eq. (11) and initial value distributed as .

Bayesian inference

This section consists of two subsections. In the first, we present the Fusion Area-Cell Spatiotemporal Generalized Geoadditive-Gaussian Field (FGG-GF) model which integrates the sub-models (3a) and (3b) into a single statistical model. The section also presents the Bayesian statistical tools. In the second section, we discuss solving the “big n” problem resulting in the Fusion Area-Cell Spatiotemporal Generalized Geoadditive-Gaussian Markov Random Field (FGG-GMRF) model and point out that it can be estimated using the R-INLA package. Details on the link between the GF and the GMRF through the Linear Stochastic Partial Differential Equation (LSPDE) approach are discussed in Appendix 1.

The fusion area-cell spatiotemporal generalized geoadditive-Gaussian field model

As observed above, combining low-resolution and high-resolution data to generate high-resolution predictions entails the risk of misalignment (Moraga et al. 2017; Utazi et al. 2019). To handle misalignment, we first stack the corresponding objects of the area and cell models in Eqs. (3a) and (3b) to give the FGG-GF model11 which is then estimated as a single model (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015; Kifle et al. 2017; Utazi et al. 2019). The FGG-GF model reads:

| 13 |

where , the global mean defined in Eq. (3), a vector of ones of dimension , the joint th risk factor with fixed coefficient and temporal random coefficient . Furthermore, , with and , with and , , with and defined as in Eq. (3), and , with and . Note that the above vectors are (( for

The following observations apply. First, the basic components of a high-resolution spatiotemporal relative risk model are the covariates and/or the GF at cell level . Either one or both are required for the estimation of the relative risk at cell level. Second, the interaction terms and in the non-separable models in Eqs. (3a) and (3b), respectively, have as covariance matrices the Kronecker products of the spatial and temporal covariance matrices (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015; Fuentes et al. 2008). See Table 5 in Appendix 2 and Sect. 3.2 for further details. For alternative approaches to handling non-separable models, see among others Bakka et al. (2020), Gneiting (2002), and Sherman (2011). Third, the parameters are estimated at area level. For the cell level, they are the corresponding area level parameters, implying that they do not vary among cells within a given area . Fourth, to control for misalignment, for each area , the model component and the area values of the risk factors are taken as the block averages of the cells within for a given time point , respectively (Banerjee et al. 2015). That is, for and , and where denotes the size of . The simplest procedure to estimate is to approximate for each time by taking the average of the values of the cell risk factor in : for , and , with denoting the number of cells in (Lawson et al. 2012; Utazi et al. 2019). Estimation of is discussed in Sect. 3.2.

Bayesian estimation of the FGG-GF model is initiated by defining the estimated parameter and hyperparameter vectors. Let and denote the parameter and hyperparameter vectors, respectively, of the FGG-GF model in Eq. (13). The joint posterior distribution of the FGG-GF model is:

| 14 |

where denotes the probability density function. Below, we first discuss the likelihood function and next the joint prior of the GF at cell level. Based on the assumption that follows a Poisson distribution at area and cell levels (see Eq. (3a) and (3b)), the likelihood function is given by:

| 15 |

The joint prior of the GF at cell level is obtained as follows. Since the GF in Eq. (8) at cell level is assumed to follow an AR1 model, the joint prior distribution of , i.e., , is (Godana et al. 2019):

| 16 |

Because of the AR1 process, we have:

| 17 |

Thus, the joint distribution of the latent spatiotemporal Gaussian process is:

| 18 |

The joint distribution of the GF in Eq. (18) consists of two probability distributions: and for . To obtain the joint distribution of , we need the joint distributions of for and and for and . is an AR1 stationary process, i.e., It is called the initial distribution for and reads as:

| 19 |

Because , with defined in Eq. (10), we have:

| 20 |

The joint distribution for and is given by:

| 21 |

Finally, the joint prior distribution for the AR1 process, denoted as , is given by multiplying Eqs. (20) and (21). It reads:

| 22 |

with denoting the covariance matrix of the GF in Eq. (12).

The priors and joint priors of and the hyperpriors of are presented in Table 5 in Appendix 2.12 Details can be found in Jaya and Folmer (2021a) and the references therein. The prior distributions are assumed to be independent, implying that:

| 23 |

The joint hyperparameter distribution is given by13:

Given the likelihood function, the joint prior distributions for the parameter vectors and the joint hyperparameter, the joint posterior distribution in Eq. (14) can be written as:

| 24 |

The fusion area-cell spatiotemporal generalized geoadditive-Gaussian Markov random field model

A continuously indexed GF typically has a dense covariance matrix, such as in Eq. (24), leading to complex, time-consuming numerical estimation challenges, commonly referred to as the “big n” problem. Lindgren et al. (2011) proposed to solve the big problem by substituting a sparse, discretely indexed Gaussian Markov Random Field (GMRF) for the continuously indexed GF.14 For a GMRF, the full conditional distribution for each component for only depends on a set of neighbors as follows:

| 25 |

where denotes all the elements in except , and denotes all the elements of in the neighborhood N() of The vector of elements of not in the neighborhood N( of is denoted as conditionally independent of the elements of . The conditional independence relationship is written as:

| 26 |

If Eq. (26) holds, the precision matrix of is sparse for each . In other words, for a pair and with and , we have:

| 27 |

implying that the nonzero pattern in the precision matrix is given by the neighborhood structure. Conversely,

| 28 |

Lindgren et al. (2011) proposed the Linear Stochastic Partial Differential Equation (LSPDE)15 approach based on a mesh of the study area, to transform a dense Matérn covariance matrix of a GF, such as in Eq. (11), into a sparse Matérn precision matrix of a GMRF (see Appendix 1). Specifically, for the GF in Eq. (12) with Matérn covariance function , is transformed into a GMRF, with sparse spatial precision matrix defined in Eq. (47). Consequently, for , the joint latent spatiotemporal GF at cell level in Eq. (12) is transformed into a GMRF as:

| 29 |

with the initial value distributed as: . The joint distribution of the -dimensional cell level GMRF is:

| 30 |

with precision matrix , i.e., the Kronecker product of the autoregressive temporal covariance matrix ( (see Table 5 in Appendix 2) and the Matérn spatial covariance matrix (, respectively.

To facilitate the estimation of , with and for , (Eq. (13)) as a GMRF , we introduce the —dimensional partitioned or block matrix that maps the GMFRs associated with the triangulation nodes16 to the areas and cells, respectively. The elements of correspond to the block average for . That is, is the sparse matrix with if vertex is in area and zero otherwise and is the number of vertices in the area . Hence, matrix reads:

| 31 |

Consequently, with th element of .

transforms the () elements of into elements of with the value of the th element corresponding to the value of th of . That is, is an sparse matrix with if the vertex l is at location and zero elsewhere such that for the gth cell for . Hence, matrix reads:

| 32 |

Given the partitioned matrix , the FGG-GF in Eq. (13) can be written as:

| 33 |

Because the FGG-GMRF model in Eq. (33) belongs to the class of the latent Gaussian models, it can be estimated using INLA-LSPDE (Cameletti et al. 2013; Gómez-Rubio et al. 2021). Predictions of the relative risk for the cells of the triangulated domain can be obtained via the posterior conditional distribution of , given for all the vertices and the posterior distributions of the parameter and hyperparameters in Eq. (24). The FGG-GMRF model setup in Eq. (33) implies that INLA generates predictions for the target cells during model-fitting.

Application: relative dengue risk at subdistrict level in Bandung, 2012–2018

Bandung city is divided into 30 districts and 151 subdistricts. The districts are third level administrative units within a province, and the subdistricts are fourth level administrative units. Every district in Bandung city consists of a minimum of four subdistricts. While the number of dengue incidences in Bandung city is reported at district level, for efficient and effective prevention and control, figures at the subdistrict scale are needed. In Sect. 4.1, we discuss and explore the data; in Sect. 4.2, we estimate the FGG-GMRF model; and in Sect. 4.3, we use the model to predict the relative dengue risk at subdistrict level.

Data and exploratory data analysis

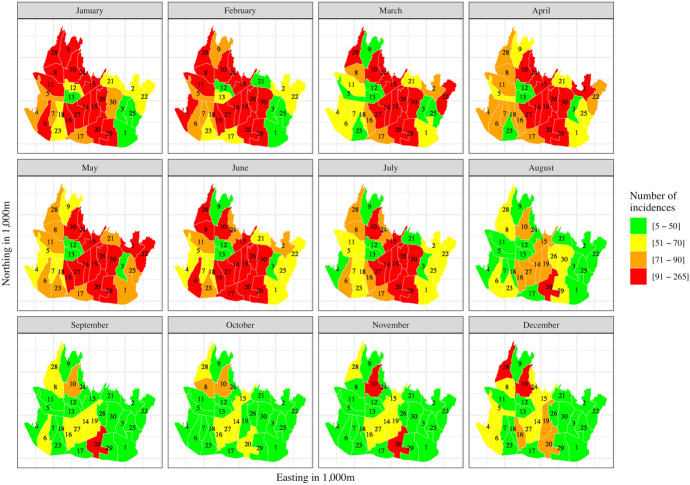

The data were obtained from existing databases. Annual observations at district level on the population at risk (see Online Resource 1) and monthly dengue incidence at district level (see Fig. 1) were obtained from the Bandung Central Statistical Bureau (2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018) and the Bandung Health Department (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019), respectively. From January 1, 2012, until December 31, 2018, a total of 26,095 dengue incidences (1,030 per 100,000 inhabitants) were reported. The monthly incidence pattern is highly similar from year to year and is taken as constant. Particularly, the mean Pearson correlation coefficient of monthly dengue incidence for the years 2012–2018 is approximately 0.70. In addition, there were no major shifts across the years in the annual cycle. Hence, as in Jaya and Folmer (2021a), we only consider the monthly cycle for the 30 districts.17 Figure 1 shows a high number of incidences from January to July, followed by a sharp drop in July and a low level of incidences for the remainder of the year. The monthly incidences range from 5 to 265 (0.197–10.461 per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Monthly dengue incidences at district level (in 1,000), Bandung City, Indonesia, 2012–2018 (1–30: district codes, see Online Resource 1)

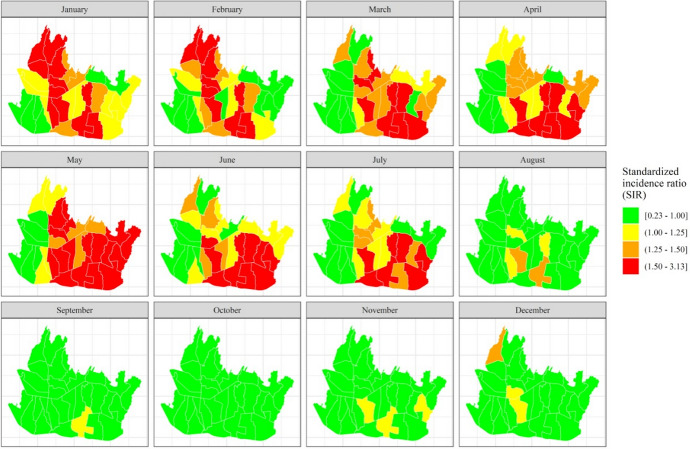

We derived the crude risk rate (i.e., the standardized incidence ratio, SIR) as the ratio of the observed to the expected number of incidences (see Eq. (2)). Figure 2 presents the monthly dengue SIR per district for the period 2012–2018. It ranges from 0.229 to 3.132. Most districts, primarily those in northern and southern Bandung, have a SIR greater than one from January to July. The districts with the highest SIR are Buah Batu (), Lengkong () and Rancasari ().

Fig. 2.

Monthly dengue standardized incidence ratio (SIR) at district level, Bandung City, Indonesia, 2012–2018

As observed by Ebi and Nealon (2016), Jaya and Folmer (2021a), and Zellweger et al. (2017), among others, socioeconomic and environmental conditions are the main factors influencing dengue disease risk over space and time. However, for Bandung, socioeconomic risk variables such as income, education, occupation and living conditions are unavailable for districts and cells. These factors are accounted for by the random effects, thus controlling for omitted variable bias (Jaya and Folmer 2020, 2021a, b). By contrast, the monthly averages of the weather risk variables of precipitation (mm), temperature (°C), sunshine duration (kJ/m2day) and water vapor pressure (kPa) are available at cell level from the WorldClim2.0 database (Fick and Hijmans 2017), obtained from 19 weather stations surrounding Bandung in West Java for 1970–2000. We selected cells of resolution 1 km2. Accordingly, Bandung city was divided into 179 cells. Table 1 presents the monthly average weather variables for the period 1970–2000.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the monthly averages of the weather variablesa

| Description | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation (mm) | 189.024 | 89.030 | 52.000 | 328.000 |

| Average temperature (°C) | 22.632 | 0.896 | 19.300 | 24.000 |

| Solar radiation (kJ/m2day) | 16,938.484 | 1,317.538 | 15,041.000 | 19,924.000 |

| Water vapor pressure (kPa) | 2.095 | 0.140 | 1.670 | 2.300 |

aWorldClim (2020) Global climate and weather data, version 2.1. WorldClim: https://www.worldclim.org/. Accessed May 2020

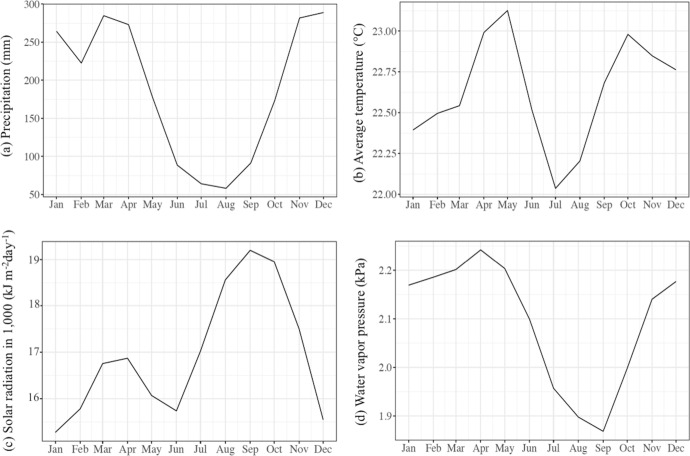

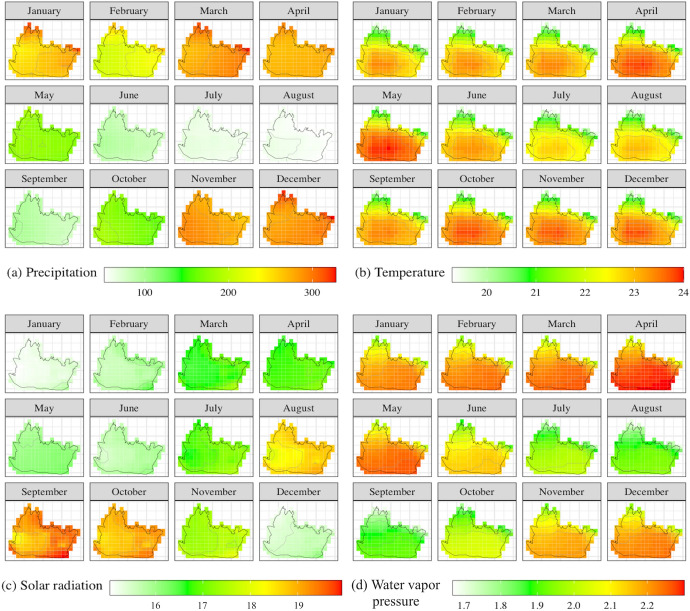

Figure 3 shows that precipitation and water vapor pressure are relatively high in the period November–April, temperature is relatively high in the period April–June and in October, and solar radiation is relatively high in the period August–November. Figure 4 indicates that the average temperature varies strongly over space. The minimum average temperature occurs in the northern districts, which are mountainous areas at approximately 800 m above sea level. In addition, they are densely covered with forests and have relatively high precipitation. The central districts, where the governmental facilities and businesses are located, also have high precipitation in the period November to April. Moreover, they have higher temperatures than northern Bandung because of differences in forest density and elevation. They also have high population density, high mobility and high air pollution (Jaya and Folmer 2020).

Fig. 3.

Monthly variation of the mean annual weather variables a precipitation (mm), b temperature (°C), c solar radiation in 1000 (kJ/m2day), and d water vapor pressure (kPa)

Fig. 4.

The spatiotemporal variation of the weather variables: a precipitation (mm), b temperature (°C), c solar radiation in 1000 (kJ/m2day), and d water vapor pressure (kPa)

In preparation for estimating the FGG-GMRF model in Eq. (33), we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF) of the weather variables to check multicollinearity. Table 2 shows that the maximum VIF is 9.312 (for water vapor pressure) which is below the critical (rule of thumb) value of 10, indicating that the correlation among variables is unlikely to affect estimation (Montgomery et al. 2012).

Table 2.

Variance inflation factors (VIF) for precipitation, average temperature, solar radiation and water vapor pressure

| No | Variable | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Precipitation (mm) | 3.074 |

| 2 | Average temperature (°C) | 3.234 |

| 3 | Solar radiation (kJ m−2 day−1) | 3.347 |

| 4 | Water vapor pressure (kPa) | 9.312 |

VIF < 10 indicates that there is no serious multicollinearity

The estimated generalized Geoadditive-Gaussian Markov Random Field model and prediction

The first step in estimating the FGG-GMRF model given by Eq. (33) is the construction of a triangle mesh of the study area for the application of the Finite Element Method (FEM) and LSPDE approach.

As described in Appendix 1, the accuracy of the FEM calculations and the precision of the forecasts, is a function of the number of vertices in the mesh (edge length). Blangiardo and Cameletti (2015) and Utazi et al. (2019) recommended varying the edge length between the minimum distance and approximately 5–8% of the maximum distance of any two cells (18,681 m). Hence, we considered vertices, corresponding to edge lengths varying from 1000 to 1500 m, with a difference18 of 100 m (see Online Resource 1). The data and R code are available in Online Resource 2.

Before turning to the estimations of the spatiotemporal FGG-GMRF model, we make the following observations. First, as explained in Sect. 3, the covariates and/or the state process at cell level are required for high-resolution spatiotemporal prediction using the FGG-GMRF model. Hence, either the covariates or , or both, are included in the selected model. Second, for every model, we considered Poisson and Negative Binomial model specifications for the number of incidences, a random walk of order one (RW1) and two (RW2) for the time-varying coefficients, structured and unstructured spatial and temporal random effects and their interaction, and six different edge lengths. Third, the best model was selected using the deviance information criterion (DIC), the Watanabe–Akaike information criterion (WAIC) and the marginal predictive likelihood (MPL). As a rule of thumb, the best model is the one with the smallest DIC and WAIC, and the largest MPL. Fourth, we started the estimation with the simplest models with covariates only (M1), and then, we proceeded to the model specifications with covariates and four types of interaction (see Table 5 in Appendix 2) at area and cell levels (M2) and, finally, we estimated the full models with covariates, four types of interaction at area and cell levels, and spatially and temporally structured and unstructured main effects (M3).19 Finally, due to the large number of outcomes, we only present the estimates for interaction Type IV (spatially structured temporally structured) which, as in Jaya and Folmer (2020), performed best among the models with spatiotemporal interaction.20

The estimations are presented in Table 6 (in Appendix 3). The table shows that the models21 with covariates only (M1) have the worst fit and predictive performance among the three classes of models. They have the highest DICs, WAICs and smallest MPLs. Given their relatively poor fit and predictive performance, the M1 models were not considered further in the selection procedure. Introduction of the interaction effect type IV (M2) yielded substantially better predictive performance. The full models with covariates, interaction at area and cell levels and spatially and temporally structured and unstructured main effects (M3) had fit and predictive performance similar to the M2 models. Hence, the main spatially and temporally structured and unstructured effects did not improve the model fit and prediction performance, which is consistent with Jaya and Folmer (2020). Based on these observations, and because the M2 models have a simpler structure, we selected the class of M2 models.

Table 6.

Deviance information criterion (DIC), Watanabe–Akaike information criterion (WAIC) and marginal predictive likelihood (MPL) of a subset of models of the FGG-GMRF model in Eq. (33)a

| Model specificationb | Likelihood | Time-varying effect | Edge length (m) | DIC | WAIC | MPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1.1.1.0 | Poisson | RW1 | – | 5184.089 | 5623.433 | − 2850.213 |

| M1.2.1.0 | NB | RW1 | – | 3281.386 | 3283.865 | − 1778.259 |

| M1.1.2.0 | Poisson | RW2 | – | 5229.130 | 5616.038 | − 2893.252 |

| M1.2.2.0 | NB | RW2 | – | 3380.390 | 3381.260 | − 1941.200 |

| M2.1.1.1 | Poisson | RW1 | 1000 | 2657.428 | 2640.887 | − 1582.563 |

| M2.2.1.1 | NB | RW1 | 1000 | 2676.950 | 2671.954 | − 1583.277 |

| M2.1.1.2 | Poisson | RW1 | 1100 | 2663.998 | 2660.371 | − 1579.446 |

| M2.2.1.2 | NB | RW1 | 1100 | 2676.937 | 2671.849 | − 1582.548 |

| M2.1.1.3 | Poisson | RW1 | 1200 | 2663.953 | 2660.405 | − 1580.599 |

| M2.2.1.3 | NB | RW1 | 1200 | 2680.719 | 2676.344 | − 1582.903 |

| M2.1.1.4 | Poisson | RW1 | 1300 | 2658.124 | 2642.776 | − 1583.341 |

| M2.2.1.4 | NB | RW1 | 1300 | 2681.375 | 2675.452 | − 1582.484 |

| M2.1.1.5 | Poisson | RW1 | 1400 | 2663.895 | 2661.152 | − 1580.897 |

| M2.2.1.5 | NB | RW1 | 1400 | 2680.761 | 2676.639 | − 1582.581 |

| M2.1.1.6 | Poisson | RW1 | 1500 | 2664.065 | 2661.030 | − 1580.177 |

| M2.2.1.6 | NB | RW1 | 1500 | 2680.761 | 2676.639 | − 1582.581 |

| M2.1.2.1 | Poisson | RW2 | 1000 | 2658.819 | 2644.598 | − 1597.562 |

| M2.2.2.1 | NB | RW2 | 1000 | 2669.423 | 2653.978 | − 1599.671 |

| M2.1.2.2 | Poisson | RW2 | 1100 | 2658.947 | 2642.814 | − 1599.163 |

| M2.2.2.2 | NB | RW2 | 1100 | 2658.947 | 2642.814 | − 1599.163 |

| M2.1.2.3 | Poisson | RW2 | 1200 | 2665.287 | 2663.565 | − 1594.933 |

| M2.2.2.3 | NB | RW2 | 1200 | 2681.804 | 2677.917 | − 1597.695 |

| M2.1.2.4 | Poisson | RW2 | 1300 | 2659.083 | 2643.993 | − 1598.382 |

| M2.2.2.4 | NB | RW2 | 1300 | 2683.923 | 2679.331 | − 1596.700 |

| M2.1.2.5 | Poisson | RW2 | 1400 | 2665.050 | 2662.933 | − 1595.102 |

| M2.2.2.5 | NB | RW2 | 1400 | 2683.923 | 2679.331 | − 1596.700 |

| M2.1.2.6 | Poisson | RW2 | 1500 | 2664.968 | 2662.321 | − 1595.516 |

| M2.2.2.6 | NB | RW2 | 1500 | 2683.821 | 2679.441 | − 1596.753 |

| M3.1.1.1 | Poisson | RW1 | 1000 | 2660.567 | 2644.342 | − 1586.289 |

| M3.2.1.1 | NB | RW1 | 1000 | 2667.208 | 2659.532 | − 1588.466 |

| M3.1.1.2 | Poisson | RW1 | 1100 | 2658.277 | 2641.471 | − 1585.928 |

| M3.2.1.2 | NB | RW1 | 1100 | 2667.213 | 2659.537 | − 1588.420 |

| M3.1.1.3 | Poisson | RW1 | 1200 | 2658.277 | 2641.472 | − 1585.928 |

| M3.2.1.3 | NB | RW1 | 1200 | 2667.213 | 2659.537 | − 1588.419 |

| M3.1.1.4 | Poisson | RW1 | 1300 | 2660.667 | 2644.078 | − 1586.228 |

| M3.2.1.4 | NB | RW1 | 1300 | 2667.213 | 2659.536 | − 1588.410 |

| M3.1.1.5 | Poisson | RW1 | 1400 | 2660.510 | 2644.422 | − 1586.429 |

| M3.2.1.5 | NB | RW1 | 1400 | 2667.191 | 2659.512 | − 1588.405 |

| M3.1.1.6 | Poisson | RW1 | 1500 | 2660.598 | 2644.207 | − 1586.461 |

| M3.2.1.6 | NB | RW1 | 1500 | 2667.191 | 2659.512 | − 1588.400 |

| M3.1.2.1 | Poisson | RW2 | 1000 | 2661.441 | 2647.045 | − 1600.555 |

| M3.2.2.1 | NB | RW2 | 1000 | 2668.788 | 2663.003 | − 1602.876 |

| M3.1.2.2 | Poisson | RW2 | 1100 | 2659.836 | 2645.165 | − 1599.883 |

| M3.2.2.2 | NB | RW2 | 1100 | 2659.836 | 2645.165 | − 1599.883 |

| M3.1.2.3 | Poisson | RW2 | 1200 | 2659.544 | 2645.097 | − 1599.448 |

| M3.2.2.3 | NB | RW2 | 1200 | 2668.788 | 2663.003 | − 1602.876 |

| M3.1.2.4 | Poisson | RW2 | 1300 | 2661.572 | 2646.658 | − 1599.695 |

| M3.2.2.4 | NB | RW2 | 1300 | 2668.788 | 2663.003 | − 1602.871 |

| M3.1.2.5 | Poisson | RW2 | 1400 | 2661.619 | 2647.490 | − 1600.489 |

| M3.2.2.5 | NB | RW2 | 1400 | 2668.803 | 2663.020 | − 1602.851 |

| M3.1.2.6 | Poisson | RW2 | 1500 | 2661.708 | 2647.171 | − 1600.532 |

| M3.2.2.6 | NB | RW2 | 1500 | 2668.803 | 2663.020 | − 1602.847 |

The second number refers to the likelihood: 1: Poisson and 2: Negative Binomial, the third to the time varying effect of the coefficients, 1: random walk of order 1 (RW1) and 2: random walk of order 2 (RW2), the fourth digit defines the edge length, 0: edge length not relevant, 1: 1000 m, 2: 1,100 m, 3: 1,200 m, 4: 1,300 m, 5: 1,400 m, and 6: 1,500 m. Note that there is no edge length for the M1 models because they do not need meshing. M1 contains 4 sub-models, and M2 and M3 contain 24 sub-models each

aThe FGG-GMRF models are specified as

bThe following notation applies. M denotes Model. M1 is the sub-model with covariates only, i.e., , M2 the model with covariates plus area and cell level interaction, i.e., (Area interaction type IV with precision matrix . M3 the full model, i.e.,

Next, we turned to the selection of the best model from the 24 models M2.1.1.1–M2.2.2.6. First, we considered the edge length, finding that the models M2.1.1.1–M2.2.2.6. have similar DIC, WAIC and MPL values. Based on this observation, we selected the edge length of 1500 m for reasons of computational time. Online Resource 1 presents the mesh. Second, among the M2 models with edge length 1500 m, the Poisson model had slightly lower DIC and WAIC and slightly higher MPL than the Negative Binomial model. In addition, the models with temporal trends RW1 and RW2 had similar DIC, WAIC and MPL values. Based on these considerations, we selected model M2 with Poisson distribution, RW1 time-varying effect, and edge length of 1500 m (denoted as model M2.1.1.6 below).

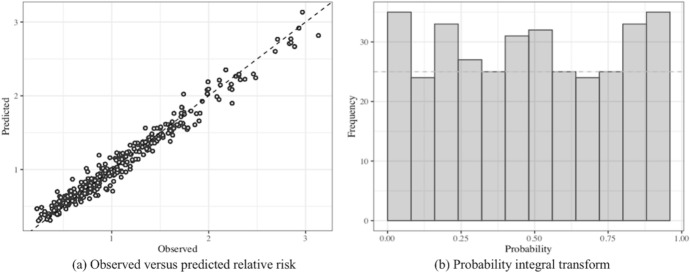

Figure 5a shows that for model M2.1.1.6, the observed and predicted dengue relative risks are strongly correlated , indicating that the model fits the data well. Figure 5b shows that the PIT histogram is close to the Uniform distribution, also indicating that model M2.1.1.6 fits the data well.

Fig. 5.

a Scatterplot for model M2.1.1.6 of the predicted versus the observed dengue relative risk and b histogram of the probability integral transform (PIT)

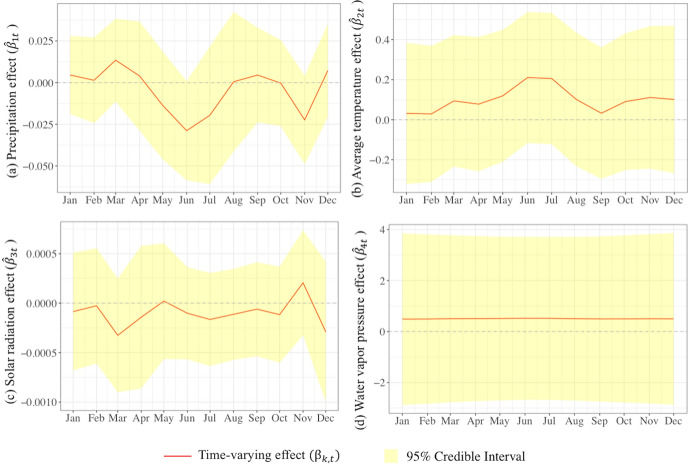

Table 3 summarizes various components of model M2.1.1.6 which are subsequently used to calculate the posterior means of the monthly relative risk at district and subdistrict levels. Before doing so, we discuss the components separately. To this end, we also make use of Figs. 6 and 7. Before going into detail, we make the following remarks. First, as observed in Sect. 2, p.8, the posterior means of the time-varying coefficients for , which are presented in Fig. 6, consist of the fixed effect plus the temporal random effect. The minimum and maximum posterior means of the temporal random effects present the largest negative and largest positive differences of the temporal random effects relative to the global effects. Secondly, the contributions of the weather variables in explaining the spatiotemporal variation of the dengue risk are conveniently summarized by the posterior means of their hyperparameter variances and their percentage contributions as fractions of the total variance (the last column of Table 3). In a similar vein, the posterior means and fractions of the hyperparameter variance of the random components present their variability and strength in explaining the relative risk across space and time.

Table 3.

The posterior means and 95% credible intervals of the fixed effects, the minimum and maximum posterior means and 95% credible intervals of the temporal random effects and the posterior means and 95% credible intervals of the hyperparameters of the FGG-GMRF model M2.1.1.6

| Parameter | Fixed effects /Global effects ( | Random effects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal random effects ( | Posterior means of the hyperparameters (95% credible interval) | Fraction of the total variance (%) | ||||

| Posterior means of the regression coefficients (95% credible interval)a | Percentage change (%)b | Minimum posterior means (95% credible interval) | Maximum posterior means (95% credible interval) | |||

| Risk factors | ||||||

| Precipitation () | − 0.0041 (− 0.0146; 0.0064) | − 0.41 | − 0.0248 (− 0.0440; − 0.0056) | 0.0176 ( 0.0032; 0.0319) | 0.019 (0.0191; 0.0191) | 8.17 |

| Temperature () | 0.1002 (− 0.1222; 0.3225) | 10.54 | − 0.0713 (− 0.1890; 0.0462) | 0.1104 ( 0.0054; 0.2153) | 0.015 (0.0145; 0.0145) | 6.20 |

| Solar radiation () | − 0.0001 (− 0.0004; 0.0002) | − 0.01 | − 0.0002 (− 0.0005; 0.0000) | 0.0003 ( 0.0001; 0.0005) | 0.023 (0.0231; 0.0231) | 9.88 |

| Water vapor pressure () | 0.5033 (− 2.4868; 3.4908) | 65.42 | − 0.0137 (− 0.3904; 0.3627) | 0.0161 (− 0.1877; 0.2197) | 0.018 (0.0178; 0.0178) | 7.62 |

| Interaction effect at area level () | ||||||

| Variance of interaction effect () | 0.102 (0.1018; 0.1018) | 43.47 | ||||

| Leroux CAR spatial autoregressive coefficient () | 0.815 (0.8147; 0.8147) | |||||

| Temporal autoregressive coefficient () | 0.962 (0.9619; 0.9619) | |||||

| Interaction effect at cell level () | ||||||

| Variance of Interaction effect at cell level () | 0.058 (0.0578; 0.0578) | 24.68 | ||||

| Spatial range () in km | 13.597 (13.597; 13.598) | |||||

| Temporal autoregressive coefficient at cell level ( | 0.749 (0.7485; 0.7485) | |||||

aThe 95% credible intervals are obtained from the posterior quantiles, i.e., and . Using INLA, the posterior marginal distributions of the parameters approximately follow a normal distribution due to the Laplace approximation (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015)

bThe exact percentage change to for a one-unit change in a risk factor with all the other variables in the model held constant, is

Fig. 6.

Time-varying effect ( of a precipitation (mm), b average temperature (°C), c solar radiation (kJ m−2 day−1) and d water vapor pressure (kPa)

Fig. 7.

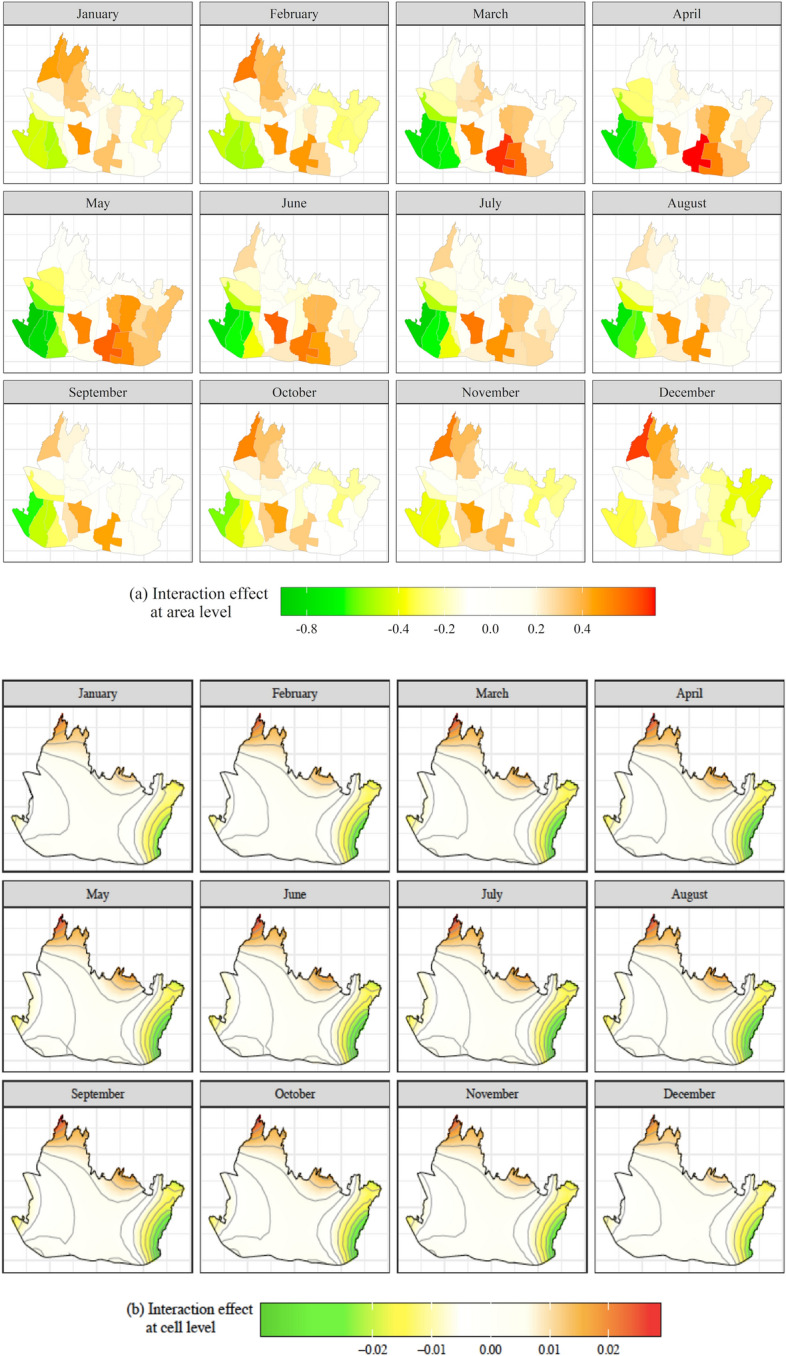

Monthly posterior means of a the area level interaction effect and b the cell level interaction effect, January–December

We will begin the discussion of Table 3 with the global mean effects of the weather variables. We only consider the posterior means and disregard credible intervals. Before going into the detail, it is worth noting that an indirect relationship exists between the relative risk of dengue and weather variables via the development and survival of the dengue virus and its vector (Jaya and Folmer 2021a).

Precipitation in general has a negative impact, with a posterior global (overall) mean of 0.0041, which is consistent with Jaya and Folmer (2021a). For a one mm increase in the global mean, the dengue risk decreases by . The explanation is that heavy rainfall disrupts the Aedes-spp mosquito’s reproductive cycle by washing away breeding sites (Abiodun et al. 2016; Benedum et al. 2018).

Temperature in general has a positive impact (0.1002), which is consistent with Hurtado-Díaz et al. (2007) and Jaya and Folmer (2021a). The relative risk increases by for an increase of global mean temperature by 10C. The explanation is that higher temperatures offer good conditions for mosquito development, particularly feeding (Hales et al. 2002; Lambrechts et al. 2012).

Solar radiation has a negative impact (− 0.0001), which is consistent with Ekasari et al. (2018), Jaya and Folmer (2021a) and Martínez-Bello et al. (2017b). An increase of 1 kJ m−2 day−1 of solar radiation decreases the relative dengue risk by . As shown by Rasjid et al. (2019), strong solar radiation negatively influences the breeding and spread of Aedes-spp mosquitoes. A longer spell of solar radiation implies a shortened spell of dawn and dusk, during which the Aedes-spp mosquito preys on animals and humans, particularly 20 to 30 min after sunset (Ekasari et al. 2018; Jaya and Folmer 2021a).

Water vapor pressure in general has a negative impact, with a posterior global mean of 0.5033. An increase of the global mean by 1% increases the relative dengue risk by due to an increase in breeding ability (Bambrick et al. 2009).

For the temporal random effects of the weather variables, the greatest negative temporal random effect of precipitation occurred in June (-0.0248), while the greatest positive occurred in March (0.0176). For temperature, the largest negative temporal random effect was in February (-0.0713), while the largest positive was in June (0.1104). Solar radiation has a temporal random effect close to zero, as indicated by its minimum and maximum posterior means of -0.0002 and 0.0003, respectively. The greatest negative of temporal random effect of water vapor pressure was in January (− 0.0137), while the greatest positive effect was in June (0.0161).

The variances of the weather variables together account for 31.87% of the total variance of the hyperpriors with solar radiation being the most important (, explaining 9.88%, while temperature is the smallest, accounting for 6.2%. The variance of the area level interaction effect () accounts for the highest fraction of the total variance (43.47%), followed by the cell level interaction effect (), with a fraction of 24.68%. These fractions indicate that the trend of dengue relative risk for each district and subdistrict is strongly affected by neighboring districts and subdistricts, respectively. The relatively low fractions of the total variance for the other effects imply that they are less important. Specifically, the low fraction of the total variance for the average temperature indicates that only a small part of the variability of the relative risk of dengue in districts and subdistricts is explained by the average temperature.

The posterior mean of hypermeter of the Leroux CAR spatial autoregressive coefficient (, and the posterior means of the hyperparameters of the temporal autoregressive coefficients at area level () and cell level () are substantial (larger than 0.700), indicating strong spatial and temporal dependency. The estimated range is equals . This implies that beyond the distance the spatial correlation among any two cells is smaller than 0.1. Hence, the observations are spatially strongly correlated. Beyond it is negligible.

Based on Table 3, we now discuss the estimated parameters for the time-varying effects of the risk factors and, next, the spatiotemporal interaction effects at the area and cell levels.

The posterior means of time-varying effects of the weather variables are presented in Fig. 6. The figure shows that the time-varying effects of precipitation, average temperature and solar radiation vary considerably over the year. The time-varying effect of water vapor pressure, in contrast, is highly constant over time.

The time-varying effect of precipitation is positive for the periods January–April, August–September and December and negative for May–July and October–November. The strongest negative effect was in June (− 0.0289), and the strongest positive effect was in March (0.0135). The negative impact for the period May–July follows after the peak of the rainy season from November–April. The negative impact for October–November is caused by the increase in precipitation after the peak of the dry season in June–July. The positive impacts for the periods January–April and August–September, and the peak in March, correspond to the relatively low rainfall one to two months before these periods.

The time-varying effect of temperature is positive for all months and ranges from 0.0289 (end of August) to 0.2106 (June–July). It increases from January–June, is at its peak in June, decreases from July until mid-September, and then starts increasing up to the global mean, where it remains for the rest of the year. Note that the monthly temperature has a delayed risk effect in that it increases from January–May, while its impact is largest in June. The delay is due to the mosquito life cycle and incubation period (Jaya and Folmer 2021a).

The time-varying coefficient of solar radiation is below zero for almost all months, except for November, and varies from − 0.0003 to 0.0002. This is due to the fact that tropical countries such as Indonesia receive a lot of solar radiation throughout the year (Handayani and Ariyanti 2012). The time-varying effect of water vapor pressure is positive all year round and hardly varies. The effect varies from 0.4896 to 0.5194. The strongest effect is in June (0.5194).

Figure 7 presents the estimated parameters of the spatiotemporal interaction effects at area and cell level which depend on their hyperparameters in Table 3.

Figure 7a presents the district level spatiotemporal interaction effects (i.e., the residual effect after accounting for the weather effects). The figure shows that the interaction effect varies across districts and time. In the northern districts, it is positive and quite high during January and February, followed by a decrease to around zero during the period March–May. From June–September it is moderately positive followed by a period of high positive interaction for the rest of the year, especially in the most north-western districts. The high interaction effect in the period September–February is related to multiple factors, in particular environmental conditions. The northern areas are ideal breeding habitats because of dense vegetation and high humidity, especially during the rainy season, with low sunshine duration and high humidity.

The central districts have high spatiotemporal interaction effects because of favorable socioeconomic conditions for the spread of the dengue virus, including high population density and high density of hotels, hostels and student apartments. For the northern central districts, there is the additional effect of spillover of mosquitoes from the northern districts. As a consequence, the interaction effect of the northern central districts follows a time pattern similar to time patterns of the northern districts, though less intense. The most central districts have high positive interaction effects all year round because they have the highest population density and density of hotels and hostels. The two most central districts have low interaction effects all year round, indicating that the main effects (risk factors) virtually fully explain the dengue risk. These districts have no special socioeconomic or environmental conditions affecting the dengue incidence rate.

In the southern districts, the spatiotemporal interaction effect is similar to that in the most central districts, although for partly different reasons. They have high population density with many residential areas that have unhygienic conditions. See Hsu et al. (2017) for details on the relationship between hygiene and dengue infection.

The situation in the eastern districts differs from that in the northern, southern and central districts. The interaction effect is negative in January and February, highly positive in March–May, slightly positive in June–August and negative for the rest of the year. The negative interaction effect in January–February is probably caused by the interaction of the weather variables and the environmental conditions. The absence of forests, heavy rainfall, and the short spells of sunshine in the period January–February keep the humidity low, which is unfavorable for the presence of dengue mosquitoes. The districts are residential areas with inadequate drainage and sanitation. The heavy rainfall until March combined with inadequate drainage and sanitation leads to large quantities of standing water, which provides favorable breeding habitats, contributing to the positive interaction effect in March.

The western districts have medium to strong negative interaction effects all year round, reducing the effects of the weather variables. The majority of the western districts have good drainage and sanitation, and the lifestyle and health behavior of the population is substantially better than in the other parts of Bandung, reducing dengue infection (Bandung Health Profile 2019). For example, the district with the highest healthy behavior index, Cicendo, is located in the western region. The negative effects also indicate that there is limited spillover of mosquitoes from the other districts.

Figure 7b presents contour maps of the cell level interaction effects. In contrast with Fig. 7a, the cell level interaction effects are almost the same across the months. Hence, after accounting for the weather variables, the cell level residual varies over space but is relatively constant over time, implying that it is related more to a topographical dimension, such as elevation, than to time. Positive cell level interaction effects are found in the northern part of Bandung, which is at 800 m above sea level and has high precipitation and dense vegetation, providing an ideal breeding ground and habitat for the Aedes-spp mosquito (Arboleda et al. 2009).

Posterior mean of the relative risk

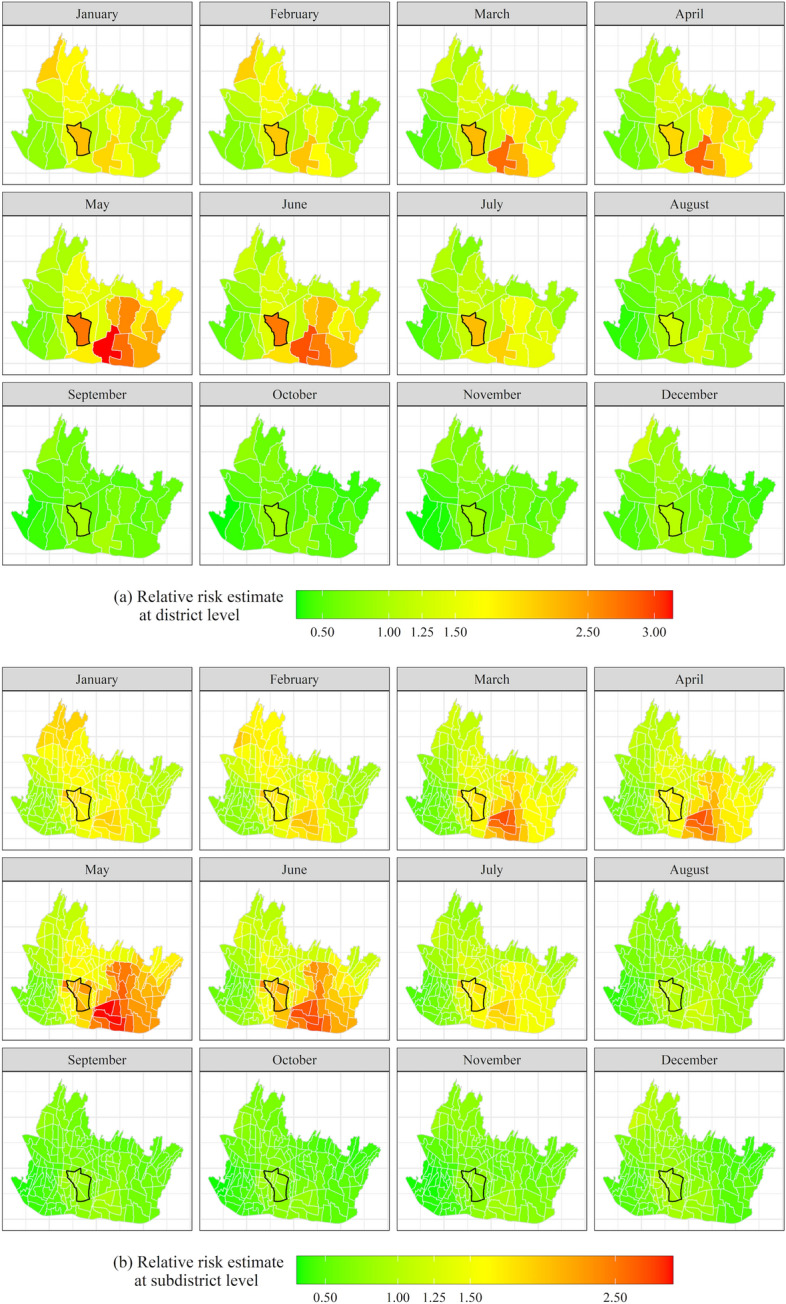

Figure 8a shows the posterior means of the relative risk estimates (based on the posterior means of the time-varying coefficients of the risk factors and the posterior means of the spatiotemporal interaction effects) at district level. The posterior means of the relative risk at subdistrict level (see Fig. 8b) are obtained as the block average of the cell values within each subdistrict boundary and the cell values that are partly outside its boundary.22 Accordingly, Bandung city is divided into 30 districts, 151 subdistricts and 179 cells.

Fig. 8.

Monthly posterior means of the relative risk at a area (district) level and b subdistrict level (surrounded area: Lengkong district)

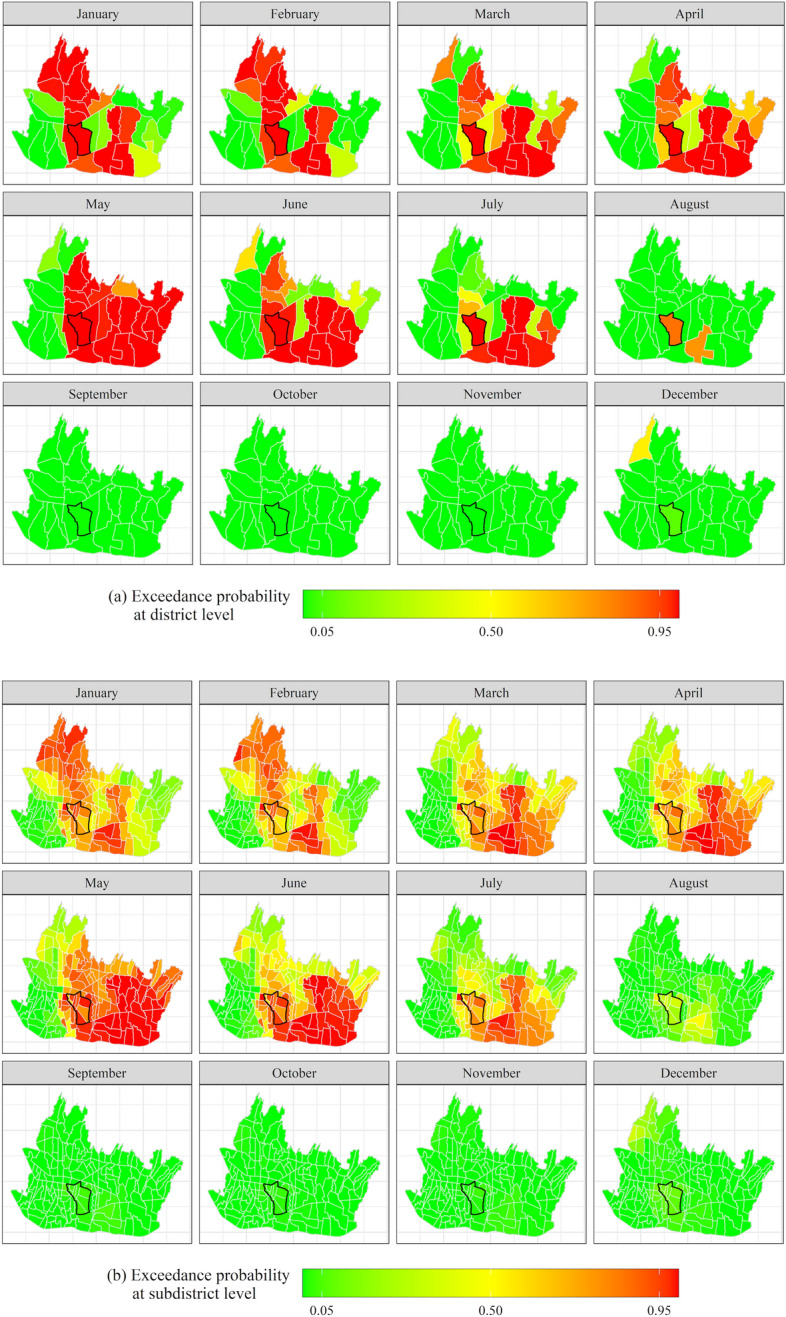

Comparing Figs. 8a and 8b shows similar temporal trends, in particular, an increase in January–July and a decrease in August–November. This applies especially to the spatial units with the highest risk, notably the districts in southern Bandung. For the spatial dimension, however, we notice substantial differences. For example, according to Fig. 8a, the entire central district of Lengkong (surrounded area in Fig. 8) is categorized as a high-risk area in the period January–July, whereas Fig. 8b shows that this only applies to parts of the district. The explanation is that categorization based on the model given by Eq. (3a) ignores within-district heterogeneity, while this is taken into account when categorization is based on the model given by Eq. (3b). To explore this issue further, we calculated the high-risk and low-risk districts and subdistricts based on the posterior exceedance probability for the two approaches, denoted as the top-down and the bottom-up approaches, respectively. Following Sparks (2015) and Osei and Stein (2017), we fixed the posterior exceedance probability threshold for . The exceedance probability over space and time is presented in Fig. 9. Table 4 presents the classification of the subdistricts into high and low risk based on the bottom-up and top-down approaches, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Monthly posterior exceedance probability of the relative risk at a district and b subdistrict levels (surrounded area: Lengkong district)

Table 4.

Misclassification of the subdistricts based on the bottom-up and top-down approaches

| Month | Bottom-up approach | Top-down approach | Misclassification (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | |||

| January | Low | 92 | 53 | 35.1 |

| High | 0 | 6 | ||

| February | Low | 97 | 48 | 31.8 |

| High | 0 | 6 | ||

| March | Low | 105 | 36 | 24.5 |

| High | 1 | 9 | ||

| April | Low | 111 | 29 | 19.9 |

| High | 1 | 10 | ||

| May | Low | 59 | 54 | 35.8 |

| High | 0 | 38 | ||

| June | Low | 93 | 30 | 19.9 |

| High | 0 | 28 | ||

| July | Low | 119 | 29 | 19.9 |

| High | 1 | 2 | ||

| August | Low | 151 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 | ||

| September | Low | 151 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 | ||

| October | Low | 151 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 | ||

| November | Low | 151 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 | ||

| December | Low | 151 | 0 | 0 |

| High | 0 | 0 | ||

| Average (%) | 15.6 | |||

Table 4 shows substantial misclassification for the top-down approach for the period January–July. The overall misclassification rate is 15.6% for all periods (January–December) and 26.7% for the high-risk period (January–July). The table furthermore shows that all the misclassifications occurred in the period January–July, which partly overlaps with the rainy season in November–May, whereas there is no misclassification from August–December. The explanation for the misclassification as such is that the bottom-up approach averages out the differences in risk factors, and consequently the number of incidences, over a set of relatively small number of relatively homogenous cells within a subdistrict. The top-down approach, on the other hand, averages out the differences over a substantially larger number of relatively heterogeneous cells in a district (a district contains at least four subdistricts; see Sect. 4.1).

The misclassification is obviously concentrated in the rainy period January–July with local variation in the risk factors due variation in local characteristics such as elevation or vegetation density. Although the rainy season is from November to May, there are positive rates of misclassification in June–July and unexpected zero rates in November–December. These misclassifications and unexpected rates are due to the delayed responses of mating, breeding and hunting by Aedes-spp mosquitos. Mating and breeding occur mainly during the rainy season. Following this, it takes approximately two weeks to one month for the eggs to develop into adult mosquitoes and for the virus to multiply and reach the salivary glands before it is transmitted to humans. If an individual is infected, the symptoms can be observed approximately four to seven days after being bitten (Ehelepola et al. 2015). Accordingly, there is a delayed infection response with respect to the weather conditions (Jaya and Folmer 2021a).

Summary and conclusions

Effective and efficient control of a variety of spatial problems, including dengue disease abatement, requires data at a fine spatiotemporal scale. However, data availability at the same (especially fine) spatial scale is quite rare (Moraga et al. 2017; Utazi et al. 2019). A major challenge in spatial sciences, including modeling of infectious diseases such as dengue and COVID-19, is how to align data bases of different resolutions consistently. In this study, we presented the Fusion Area-Cell Spatiotemporal Generalized Geoadditive-Gaussian Markov Random Field model as a solution to this problem. This model combines observations on the dependent variable and population at risk at the area level and covariates at the cell level to generate predictions of relative risk at the subdistrict level. Special attention was paid to the model setup to generate predictions for the target cells during model-fitting, using Bayesian Integrated Nested Laplace Approximation (INLA). The methodology was applied to monthly dengue disease data for 30 districts in the city of Bandung, Indonesia, for the period January 2012 to December 2018. The risk factors consisted of the monthly averages of precipitation, temperature, solar radiation and water vapor pressure. The analysis showed that the effects of precipitation, temperature and solar radiation varied considerably across space and time, while the effect of water vapor pressure was highly constant over time. Solar radiation was found to be the most important risk factor. The spatiotemporal interaction effect, capturing the effects of omitted variables at area level, also varied across districts and time. In contrast, the cell level interaction effect was almost constant over the months but varied substantially over space, indicating a strong spatial spillover effect.

Based on the posterior means of the relative risk at cell level, we obtained the relative risk estimates at subdistrict level. We found a similar temporal pattern for district and subdistricts. Relative dengue risk was relatively high in the period January–July and relatively low during the period August–December. We further compared the risk estimates per subdistrict based on: (i) the bottom-up approach using the cell level estimates and (ii) the top-down approach assigning the district value to its subdistricts. Using the posterior exceedance probability of the relative risk, we identified high-risk and low-risk districts to find that during the high-risk period of January–July, the top-down approach misclassified 26.4% of the subdistricts as high risk, which according to the bottom-up approach was low risk. The overall misclassification rate was 15.6%.

The main conclusions of the paper are the following. First, effective and efficient policy intervention, such as the control of infectious diseases, requires data at the right level of resolution. In particular, low-resolution maps may misclassify regions. If regions are incorrectly misclassified as high-risk, unnecessary policy intervention with undue financial, social and environmental costs may result. In contrast, if regions are incorrectly misclassified as low-risk, opportunities for policy intervention may be missed which may also have costs of various kinds. Secondly, the proposed FGG-GMRF model adjusts data and maps of different resolutions consistently, and allows more data to be utilized, thus improving the statistical efficiency. Third, application of the FGG-GMRF model to the dengue disease data for Bandung from 2012 to 2018 shows that the relative infection risk is high in various cells, subdistricts and districts from January–July. The strong spatiotemporal interaction indicates that the occurrence of the dengue disease vector is highly contagious and must be detected early in order to prevent its spread. Rapid response measures such as fogging are critical in areas with high dengue incidence. Finally, based on the experiences in the present paper, it is worthwhile to investigate the suitability of the FGG-GMRF model for a variety of other spatiotemporal problems, including other infectious diseases such as COVID-19 (see Jaya and Folmer 2021b), vaccination coverage (Utazi et al. 2019), particulate matter concentration (Cameletti et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2016), and social issues such as unemployment and crime.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Bandung City Health Office for providing the data. This research was funded by ALG Unpad contract: 1427/UN6.3.1/LT/2020.

Appendix 1: The linear stochastic partial differential equation approach

A GF with dense covariance matrix can be transformed to a GMRF with sparse covariance matrix by means of a Linear Stochastic Partial Differential Equation (LSPDE) (Lindgren et al. 2011) which reads:

| 34 |

where is a temporally independent GF, a Gaussian white noise process, a positive integer related to the smoothness parameter of the Matérn covariance function in Eq. (11) by and the Laplace operator, i.e., . Using spectral decomposition, Whittle (1954, 1963) showed that for > 1, the only exact stationary solution to Eq. (34) is the isotropic Matérn field, i.e., the stationary GF with the Matérn covariance function in Eq. (11).

A closed-form solution for the LSPDE in Eq. (34) is restricted to regular lattices (Lindgren et al. 2011). For an irregular lattice, it can be approximated through a basis function representation using the Finite Element Method (FEM) defined on the domain . The basis function representation is defined on a mesh, that is, a collection of (i) vertices, (ii) the edges between the vertices, and (iii) the polygons described by the edges. A mesh consists of a minimum of three connected edges conforming to the shape of the domain. It subdivides a continuous geometric space into a finite set of discrete geometric or topological elements such as triangles or rectangles (for a two-dimensional geometric space) or tetrahedral or rectangular prisms (for three-dimensional spaces). It reduces the degrees of freedom from infinite to finite. Because the FEM calculations are based on a finite number of cells and the results are generalized through interpolation for the entire domain, the accuracy of the global solution is a function of the number of elements of the mesh (Bohn and Feischl 2021).

Triangulation is a common FEM meshing scheme (Sloan 1993) because of its flexibility for irregular domains (Lindquist and Gilest 1989) and accuracy (due to the minimization of the discretization error)23 (Ahmadian et al. 1998). Triangulation divides the domain into a set of non-intersecting triangles, where any two triangles meet in, at most, a common edge or vertex. The popular Delaunay triangulation scheme (Cheng et al. 2013) ensures that the triangulation maximizes the minimum angle of the triangles, thus avoiding sliver (i.e., long and thin) triangles and rendering the transitions between small and large triangles smooth (Lindgren et al. 2011). The restricted Bowyer–Watson algorithm, which is designed to conform to the domain’s boundary, is a popular Delaunay triangulation algorithm (Cheng et al. 2013).

A drawback of applying an algorithm with boundary conditions is that the variance near the boundary is inflated by a factor of two (Lindgren et al. 2011). To avoid the boundary effect, Lindgren and Rue (2015) proposed to extend the domain of interest by an outer area at a distance of at least , corresponding to a correlation of approximately 0.1 between two points in the inner and outer areas. The edge length of the triangles of the outer area should be at least equal to the edge length of the triangles of the inner area (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015). To find the appropriate mesh for the data at hand, meshes of different sizes are usually considered, which can be evaluated using the DIC and WAIC (Righetto et al. 2018).

Given the triangular mesh, the FEM of the solution of the LSPDE in Eq. (34) is:

| 35 |

with the set of piecewise linear basis functions, the number of vertices in the triangulation and l the th vertex. For location , the piecewise linear basis function is:

| 36 |

The are zero mean Gaussian-distributed weights determining the value of for vertex at location . Hence, is uniquely defined by its values at the vertices of the mesh. The values in the interior of the triangles are estimated by linear interpolation. Hence, the Gaussian-distributed weights determine the values of the GF at the vertices such that the distribution of is determined by the joint distribution of the weights with sparse precision matrix (Lindgren et al. 2011).

To show that Eq. (34) approximates the GF , we take24 corresponding to = 1, define the LSPDE in Eq. (34) as a variational problem, i.e., multiply it by an arbitrary test function with , and integrate it by parts over the domain using Green’s first identity theorem25 (Langtangen and Logg 2016). Multiplying the LSPDE in Eq. (34) by a test function gives:

| 37 |

where is the entire spatial domain over which Eq. (37) is to be solved and is shorthand for of the two-dimensional integral. Partial integration of gives:

| 38 |

where is the directional derivative of in outward normal direction on the boundary (i.e., the subset of points which can be approached both from and from the outside of ) (Langtangen and Logg 2016) and is shorthand for of the two-dimensional integral along the boundary . Substituting Eq. (38) in Eq. (37), we have:

| 39 |

with the Neumann boundary condition:

where | denotes the boundary (Bakka 2019). Hence, Eq. (39) can be written as:

| 40 |

Because the set of the test functions is infinite (Langtangen and Logg 2016), it is not possible to test Eq. (40) for every test function . As a solution, the FEM can be applied to construct a finite set of test functions and tested against Eq. (40). Using Eq. (35) and substituting in Eq. (40), we obtain the system of linear equations:

| 41 |

The test functions are commonly taken to be equal to the basis functions, i.e., 26 for . Hence:

| 42 |

The integral on the right-hand side of Eq. (42) is the Gaussian white noise distribution , with mean zero and covariance matrix27:

| 43 |

We can write Eq. (42) in matrix form as (Simpson et al. 2012):

| 44 |

where , , and .

Because of the highly local nature of the piecewise linear basis functions, and are sparse matrices. However, is a dense matrix and will generally not be a GMRF. Lindgren et al. (2011) proposed to solve this issue by reducing the integration order of the inner product of the piecewise linear basis functions and for vertices and on the interval (i.e., )28 by taking as the constant function 1 yielding . The result is an approximate diagonal matrix, with diagonal elements . Replacing with yields

| 45 |

and

| 46 |

with the precision matrix

| 47 |

where Because of the serial independence assumption in Eq. (9), is constant over time.

Bolin and Lindgren (2009) compared the exact FEM approach (using with all the elements of calculated as a Hilbert space wavalet model such as a B-spline or a Daubechies wavalet model), and the Markov approximation (replacing with ) for spatial prediction and found that the differences between both approaches in terms prediction errors are negligible.

Appendix 2

This appendix consists of three parts. The first part is Table 5. which presents the priors and hyperpriors for the FGG-GMRF model given by Eq. (33). The second part consists of comments on the priors and hyperpriors and the final part deals with identification.

Priors, joint priors and hyperpriors for the FGG-GMRF model

See Table 5.

Comments on the priors and hyperpriors

The following observations apply for the parameters and hyperparameters of the FGG-GMRF. Due to the lack of strong prior knowledge, we used a vague Gaussian prior distribution with a zero mean and a very large variance for the parameters and for (Blangiardo and Cameletti 2015; Martinez-Beneito and Botella-Rocamora 2019). A weakly informative prior29 was assigned to the log-odds of the spatial autoregressive parameter (Utazi et al. 2019). Note that the transformation is used to ensure that takes values between 0 and 1 (Bivand et al. 2015; Martinez-Beneito and Botella-Rocamora 2019).