Abstract

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is a rare and aggressive tumor in humans with no universally agreed standard of care therapy. Spontaneous canine HS exhibits increased prevalence in specific breeds, shares key genetic and biologic similarities with the human disease, and occurs in an immunocompetent setting. Previous data allude to the immunogenicity of this disease in both species, highlighting the potential for their successful treatment with immunotherapy. Quantification of CD3 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) in five cases of human HS revealed variable intra-tumoral T cell infiltration. Due to the paucity of human cases and lack of current model systems in which to appraise associations between anti-tumor immunity and treatment-outcome in HS, we analyzed clinical data and quantified TIL in 18 dogs that were previously diagnosed with localized HS and treated with curative-intent tumor resection with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. As in humans, assessment of TIL in biopsy tissues taken at diagnosis reveal a spectrum of immunologically “cold” to “hot” tumors. Importantly, we show that increased CD3 and granzyme B TIL are positively associated with favorable outcomes in dogs following surgical resection. NanoString transcriptional analyses revealed increased T cell and antigen presentation transcripts associated with prolonged survival in canine pulmonary HS and a decreased tumor immunogenicity profile associated with shorter survivals in splenic HS. Based on these findings, we propose that spontaneous canine HS is an accessible and powerful novel model to study tumor immunology and will provide a unique platform to preclinically appraise the efficacy and tolerability of anti-cancer immunotherapies for HS.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-021-03033-z.

Keywords: Histiocytic sarcoma, Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, Comparative oncology, Canine model, Tumor immunogenicity

Introduction

Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) is an uncommon hematologic malignancy comprised of mature histiocytes exhibiting monocytic/macrophage immunophenotype and morphology [1]. Owing to the rarity of this diagnosis in humans, there is currently no universally agreed standard of care therapy. Surgery is generally considered a valuable treatment modality and was found to significantly improve survival in patients without evidence of splenic or bone marrow disease [2]. While a subset of patients with local disease exhibit prolonged survival after surgery with or without adjuvant radiation therapy, the potentially aggressive clinical course following curative-intent local treatment and the inability to identify patients at risk of metastasis leads to the frequent addition of chemotherapy [3]. Moreover, HS patients commonly present with disseminated disease [4], thus requiring systemic therapy for which various multi-agent chemotherapeutic approaches have been described [5, 6]. An alternative approach has been to target patient-specific oncogenic mutations. Such a strategy was utilized in the treatment of a HS patient with an activating mutation in MAP2K1, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, who achieved a complete clinical response following treatment with trametinib, a MAPK (MEK) 1 and 2 inhibitor [7]. However, despite both aggressive local control and systemic therapies, patient data from 159 HS cases mined from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database revealed a median overall survival time of only 6 months [2]. The low incidence of this disease supports the need to identify a large animal model in which to study the pathology of HS and subsequently provide a platform to appraise much needed novel therapeutic approaches.

Genetically outbred and immunologically intact canine cancer patients that develop tumors spontaneously [8, 9] are rapidly gaining traction as an invaluable preclinical model. This comparative approach is further bolstered by the fact that canine patients routinely receive definitive treatment, encompassing advanced surgical, radiation, cytotoxic, and targeted therapies [8–10]. HS is overrepresented in a number of dog breeds, including Bernese mountain dogs, retrievers, Rottweilers, and miniature schnauzers [11–14]. Canine HS is an aggressive disease that manifests in a variety of clinical presentations depending upon stage and anatomic location [15, 16]. As in humans, the prognosis for dogs with disseminated HS is unfavorable with a median survival time of four months when treated with chemotherapy. However, long-term survival for localized forms of HS can be achieved following treatment with a combination of surgery and adjuvant chloroethylcyclo-hexylnitrosourea (CCNU) [17, 18]. As such, dogs have a higher incidence of disease, and first-line treatment of localized canine HS is more homogenous relative to human HS. A number of genetic similarities between canine and human HS have also been detected, including loss of tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN and mutations to PTPN11 and KRAS, both of which have been associated with oncogenic activation of MAPK signaling [19–21]. The biologic, genetic, and clinical similarities between the human and canine variants of HS highlight the potential value of spontaneously occurring canine HS as a translational model in which to assess HS pathogenesis, identify potential biomarkers of disease progression, and ultimately to test novel therapeutic strategies. Increased tumor incidence in specific dog breeds provides an accessible and unique model to study this rarely diagnosed malignancy.

Studies to test the activity of targeted therapeutics for HS to date have focused on canine xenograft models in which canine tumor cells are orthotopically engrafted into immunocompromised mice [21]. As demonstrated in human HS patients, these canine systems revealed that specific targeting of oncogenic mutations by selective inhibitors, such as trametinib, show promising signs of preclinical activity [20, 21]. However, the paucity of immune competent model systems in which to study anti-tumor immunity in HS has limited the study of immunotherapeutics. Crucially, dogs spontaneously develop tumors in a natural stepwise manner with conservation of both initiation and progression processes under the surveillance of an intact immune system [10, 22]. Spontaneous canine HS therefore has the potential to become a unique and compelling model in which to study cancer immunology.

A growing body of evidence supports the anti-tumor function of cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) in multiple species [8, 23]. A seminal study by Galon et al. [24] revealed that cancer patients with T cell inflamed (hot) colorectal carcinoma biopsies had significantly improved prognoses compared to patients with non-inflamed (cold) tumors, and this finding was independent of grade. Similar prognostic implications for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) have been recorded in multiple other tumor types (reviewed in [25]). Prominent inflammation comprised of TIL and polymorphonuclear cells is a common histopathologic observation in human HS [26–28]; however, TIL have yet to be quantified in these exceptionally rare tumors. Although determining the prognostic relevance of TIL in human HS would be desirable, the design of well controlled studies is currently hindered by the marked infrequency of this diagnosis alongside highly heterogeneous approaches to treatment.

Intriguingly, a recent case report described a favorable therapeutic response in a young adult diagnosed with metastatic HS treated with the PD-1 blocking antibody nivolumab [29]. The PD-1 receptor is expressed on lymphocytes and nivolumab is posited to mediate its therapeutic effects by blocking PD-1 interaction with its inhibitory ligands primarily within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [30, 31]. PD-1 positive TIL have been identified in multiple histiocytoses including histiocytic sarcoma [32]. The favorable response to this checkpoint inhibitor provides further evidence of a population of TIL that may be exploited in HS patients.

Although a T cell infiltrate has been previously noted in flat-coated retrievers with HS [33], the prognostic implications of the extent and phenotype of TIL has not been explored. Here, we describe the findings of our study quantifying TIL infiltrate in human and localized canine HS and show that these malignancies vary across a spectrum from immunologically cold to hot in both species. Furthermore, increased TIL density in canine tumor tissue taken at the time of initial curative-intent resection confers a favorable outcome. Transcriptional analyses of dogs diagnosed with pulmonary HS revealed increased T cell and antigen presentation associated transcripts in this subset exhibiting prolonged survival times compared with a signature associated with decreased tumor immunogenicity in dogs with splenic HS and shortened survival times. Based on the data presented, we propose that spontaneously occurring canine HS represents a powerful new comparative model in which to investigate anti-tumor immunity in a rare and highly aggressive hematologic malignancy.

Materials and methods

Study populations

A retrospective search of cancer registry database at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) to identify all patients with a confirmed diagnosis of “histiocytic sarcoma” since 2011 was performed. Similarly, a retrospective search of the Penn Vet Diagnostic Laboratory database from 2012 to 2018 was performed to identify all dogs with a histopathologic diagnosis of “sarcoma” or “histiocytic sarcoma.” H&E tumor samples were retrospectively reviewed by board-certified pathologists (human-PJZ; canine-ACD) to ensure tumor morphology was consistent with the diagnosis of HS. Diagnosis of HS in humans was confirmed at the attending pathologist’s discretion using immunohistochemical panels (Table S1). Immunohistochemical analyses of archived residual formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) human tumor samples were approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board (IRB#848935).

For human HS, overall survival was recorded from the time of diagnosis of HS until death. For canine HS, medical records were reviewed and patients with localized tumors and a definitive diagnosis of HS were included. At the time of diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining for CD18 [11], CD204 [34] and/or IBA1 [35] was performed at the initial attending pathologist’s discretion to support the diagnosis of HS. For cases that did not have IBA1 immunohistochemistry performed at the time of diagnosis, IBA1 expression was retrospectively confirmed using immunohistochemistry to support the diagnosis of canine HS [35]. Inclusion criteria for dogs were as follows: adequate baseline testing to support the diagnosis of localized disease (complete blood counts, serum biochemistry, thoracic and abdominal imaging), treatment with curative-intent surgical resection of the tumor with or without adjuvant CCNU chemotherapy, and detailed follow-up data including date and cause of death. Required follow-up information not present within the medical record was obtained by contacting the referring veterinarian and owners. Dogs were considered to have localized HS if a single mass was identified and all metastatic disease, if present, was limited to a local lymph node bed. Dogs with CNS disease were excluded. Data captured included as follows: signalment, body weight, presenting complaint, clinicopathologic and diagnostic imaging findings, treatment, therapeutic response, survival time, and necropsy information (when performed). No animal experimentation was performed and all data in this study were obtained from materials collected in the course of routine clinical care, including use of residual FFPE tumor samples and thorough medical record review. Retrospective studies are exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Veterinary School Privately Owned Animal Protocol Committee.

Immunohistochemistry and digital image analyses

For immunohistochemistry, 5 µm thick FFPE sections of each biopsy were mounted on ProbeOn™ slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The immunostaining procedure was performed using a Leica BOND RXm automated platform combined with the Bond Polymer Refine Detection kit (Leica #DS9800). Briefly, after dewaxing and rehydration, sections were pretreated with either the epitope retrieval BOND ER2 high pH buffer (Leica #AR9640) (CD3 and FoxP3), or the epitope retrieval BOND ER1 low pH buffer (Leica #AR9961) (granzyme B) for 20 min at 98 °C. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated with 3% H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature (RT). Nonspecific tissue-antibody interactions were blocked with Leica PowerVision IHC/ISH Super Blocking solution (PV6122) for 30 min at RT. The same blocking solution also served as diluent for the primary antibody. A rabbit polyclonal primary antibody against granzyme B (GZB, Abcam ab4059) with cross-reactivity for canine GZB demonstrated by Frazier et al. [36] and rat monoclonal primary antibodies against CD3ε (CD3, Bio-Rad MCA1477T) and FOXP3 (eBioscience 14-5773-80) at a concentration of 1/200, 1/600 and 1/50, respectively, were used and incubated on the slides for 45 min at RT. A biotin-free polymeric IHC detection system consisting of HRP conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-rat IgG was then applied for 25 min at RT. Immunoreactivity was revealed with the diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen reaction. Slides were finally counterstained in hematoxylin, dehydrated in an ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and permanently mounted with a resinous mounting medium (Thermo Scientific ClearVue™ coverslip). Sections of human and canine lymphoid tissues were included as positive controls. Negative controls were obtained either by omission of the primary antibodies or replacement with an irrelevant isotype-matched rabbit polyclonal or rat monoclonal antibody.

The slides were then scanned using the Aperio AT2 automated slide scanner (Leica Biosystems) and visualized with the ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems). Two nuclear algorithms, available on ImageScope, were created for cell counting on the CD3 and FoxP3 stained slides and optimized to detect signal only within non-necrotic areas. All present tumor tissue, including areas of histomorphologic necrosis, was contoured to be included prior to application of the CD3 and FoxP3 algorithms. Granzyme B-positive lymphocytes were manually counted in 10 representative 1 mm2 non-necrotic regions of the tumor based on cellular morphology and staining pattern as an adequately sensitive and specific automated algorithm could not be applied to this population owing to the characteristic focal and granular staining of GZB positive TIL. The representative tumor regions were evenly distributed between tumor center and periphery, excluding areas of necrosis. Counts were then normalized for tumors with evidence of histomorphologic necrosis, such that if the tumor appeared 20% necrotic at low power, the final count was multiplied by a factor of 0.8.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence (IF) combining GZB and CD3 was also performed on representative samples using the OPAL Automation Multiplex IHC Detection Kit (Akoya Biosciences #NEL830001KT) implemented onto a BOND Research Detection System (Leica #DS9455) according to the manufacturer instructions. For this technique GZB and CD3 antibodies were used at a concentration of 1/1500 and 1/2000, respectively. The slides were then scanned using the Aperio VERSA 200 automated slide scanner (Leica Biosystems) and visualized with the ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems).

NanoString

RNA was extracted from FFPE scrolls using a RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen), DV200 values were > 50% for all samples as determined by TapeStation (Agilent). RNA (100 ng) in 5 uL was hybridized with gene-specific reporter and capture probes (nCounter Canine IO panel) at 65 °C for 18 h and processed on the nCounter Prep station. Data were acquired using nCounter scanner, both systems are part of the NanoString nCounter Flex system. Profiled data were pre-processed, specifically background was subtracted by using threshold counts of 20, normalization was performed with positive control and housekeeping genes using nSolver v4 software (NanoString) and no QC flags were raised. Obtained values were Log2 transformed prior to identification of differentially expressed (DE) genes (p < 0.05) using heteroscedastic t tests as per manufacturers’ recommendation. DEs were plotted using agglomerative clustering (Euclidean distance), fold changes and p values were reported for each DE.

Statistical analyses

Tumor-specific survival times were calculated in days from confirmation of diagnosis until death from HS and were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) product-limit estimator. When used in survival analyses, TIL counts were converted to binary variables according to whether a value was above and below the median value. Some patients were right-censored due to non-tumor associated death. KM curves were compared using the log-rank test. TIL densities were compared between groups using two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests. Correlation analyses were performed using Spearman correlation. Cox proportional-hazards regression models were fit when possible to allow for the inclusion of multiple potential predictors and verify that prognostic factors remained significant in the presence of other variables. Cox models with single predictor variables were used to estimate hazard ratios, and the log-rank test was used to determine the significance of hazard ratios based on these models. The proportional hazards assumptions were met for all variables and validated based on scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism v9 (GraphPad) and the survival and survminer packages for R 4.0.0 (R Core Team 2020).

Results

Human HS is variably infiltrated with T cells

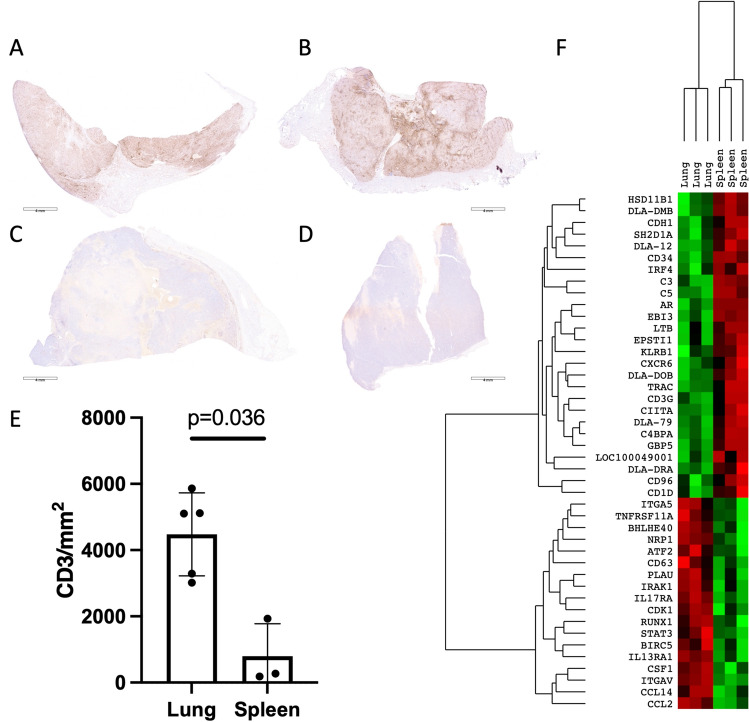

FFPE tissues from three male adult and two female adult HS patients were identified following a search of the HUP database. These tissues were stained with an antibody against the pan-T cell marker CD3, were scanned and underwent CD3 + TIL quantification. CD3 counts ranged from a heavily inflamed tonsillar HS (7934 cells/mm2) to a tumor virtually devoid of CD3 + TIL (30 cells/mm2) that notably was located within the spleen (Fig. 1, Table S1). At the time of writing, three patients with the greatest TIL infiltrate were still alive at last follow-up and the two patients with the lowest were deceased (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

Variable infiltration of human HS by T cells. IHC staining for CD3 in a tonsillar; b subcutaneous (left buttock); c subcutaneous (right foot); d brain and e splenic HS. f Survival time in days plotted as a function of primary tumor location and quantification of CD3 + TIL density. IHC staining detected using DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin, scale bars—70 µm. Histiocytic sarcoma, HS; diaminobenzidine chromogen, DAB; Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, TIL

Description of cohort of dogs diagnosed with HS

Based on the above observations in human HS, we identified eighteen cases of localized canine HS for quantification of TIL and the clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Table S2. Over 50% of our patients were from high-risk breeds, including Bernese mountain dogs, retrievers, and Rottweilers. The median age of dogs was 9 years with only fully grown dogs represented, consistent with the diagnosis of human HS affecting mostly middle to old-aged patients [2–4]. In our study, there were twice as many male dogs compared to females, which is also in-line with a higher incidence in males reported by the largest American study of HS patients described to date [2]. Collectively, demographics of the dogs not only reflect those of human patients, but also highlight the utility of predisposed breeds for studying HS.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of dogs with HS

| Variable | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients (2012–2018) | 18 |

| Median age (years) | |

| Male | 12, range 6–11 |

| Female | 6, range 4–13 |

| Median weight (kilograms) | |

| Male | 33.2, range 4.0–56.4 |

| Female | 26.9, range 10.2–41.3 |

| Sex | |

| Male, intact | 1 (6) |

| Male, castrated | 11 (61) |

| Female, castrated | 6 (33) |

| Breed | |

| Golden retriever | 3 (17) |

| Rottweiler | 3 (17) |

| Bernese mountain dog | 2 (11) |

| Flat-coated retriever | 1 (5.5) |

| Labrador retriever | 1 (5.5) |

| Greyhound | 1 (5.5) |

| Portuguese water dog | 1 (5.5) |

| Standard poodle | 1 (5.5) |

| Boxer | 1 (5.5) |

| Australian shepherd | 1 (5.5) |

| Cavalier King Charles spaniel | 1 (5.5) |

| Beagle | 1 (5.5) |

| Mixed breed | 1 (5.5) |

| Site | |

| Periarticular tissue | 8 (44) |

| Lung | 5 (28) |

| Spleen | 3 (17) |

| Lymph node | 2 (11) |

| Diagnostics | |

| Thoracic radiograph | 9 (50) |

| Thoracic CT | 9 (50) |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 16 (89) |

| Abdominal CT | 2 (11) |

| Metastases | |

| None | 14 (78) |

| Nodal | 4 (22) |

| Treatment | |

| Curative-intent surgery | 18 (100) |

| Adjuvant CCNU chemotherapy | 12 (67) |

| Steroid | 4 (22) |

| NSAID | 8 (44) |

CT computed tomography; CCNU chloroethylcyclo-hexylnitrosourea; NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; GZB Granzyme B

Disease staging was performed in all dogs to confirm the diagnosis of localized HS. There was no indication of hemophagocytic HS on bloodwork or medical record review. Anatomic distributions were determined using a combination of physical exam findings, diagnostic imaging, and surgical explorations. Similarity of affected sites was noted in dogs compared to humans where skin/connective tissues are most frequently involved followed by lymph nodes and the respiratory system [2]. Four of the dogs with periarticular HS had evidence of metastasis to a local lymph node and this is reminiscent of the progression of localized HS in humans, where nodal metastases from primary extranodal HS is the most common manifestation of an aggressive disease course [3]. Collectively, our data reveal that the disease distribution and biologic behavior of these tumors are similar across the canine and human species barrier.

Treatment of the dogs in this study was prescribed with the primary goal of achieving locoregional control, with adjunct systemic therapy recommended at the discretion of the attending veterinarian to impede disease dissemination. All dogs were treated with curative-intent surgery and 12 (67%) received adjuvant single-agent CCNU chemotherapy administered at a median starting dose of 66 mg/m2 (range 60–71 mg/m2) every 3 weeks. No dogs underwent radiation therapy. At the time of HS progression, three dogs received additional chemotherapy consisting of single-agent doxorubicin (n = 2) or single-agent dacarbazine (n = 1). For all dogs, the median tumor-specific survival was 256 days (range 75–1062 days). One dog was still alive at the time of manuscript preparation, 920 days after diagnosis. Fifteen dogs died as a result of HS, consistent with the aggressive nature of the disease in humans (Table S2). However, as in people, a small subset of dogs had more favorable long-term outcomes when treated comprehensively [2, 3].

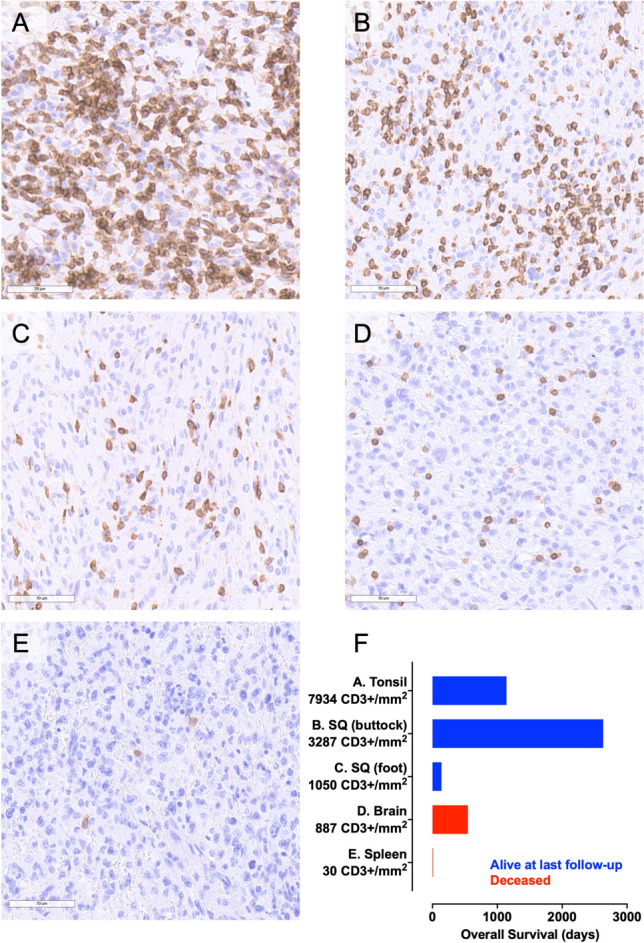

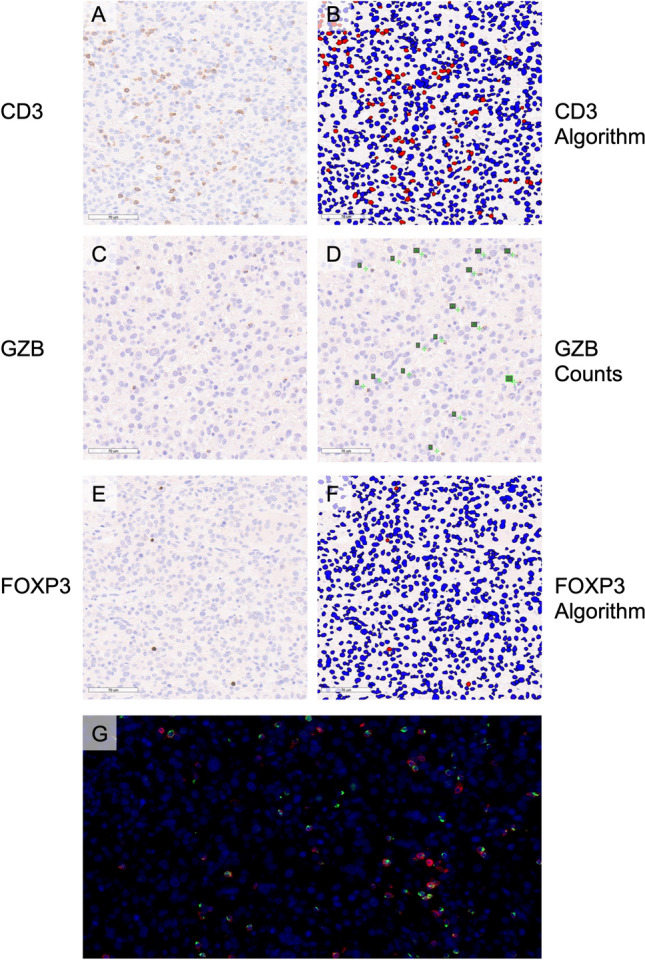

TIL quantification from digitally captured images of HS biopsies

In order to determine the prognostic implications of TIL density in canine HS, FFPE samples taken at the time of diagnosis were immunohistochemically stained with antibodies against CD3; the effector cytotoxic serine protease, GZB; and the key transcription factor for immunosuppressive Tregs, FOXP3. Slides were scanned to enable digital image capture and quantification of TIL (Figs. 2, 3). Variable TIL densities were observed ranging from sparsely (Fig. 2) to heavily infiltrated tumors (Fig. 3). Median cell counts (range) for CD3, GZB and FOXP3 were 2243 (170–5865), 219.5 (19–673) and 182.5 (5–832) cells/mm2, respectively (Fig S1 & Table S2). Immunofluorescence of representative samples revealed colocalization of GZB with CD3 (Figs. 2g, 3g). Comparatively there was no significant difference of CD3 densities between human and canine HS (Fig S2).

Fig. 2.

Sparsely infiltrated splenic HS in an 11-year-old male standard poodle. a IHC staining for CD3 and b application of nuclear quantification algorithm, c IHC staining for GZB and d manual quantification of digitally captured image, e IHC staining for FOXP3, and f application of nuclear quantification algorithm, g IF of nuclei, CD3 and GZB. IHC staining detected using DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin, scale bars—70 µm, negatively stained cells are labeled blue and positively stained cells labeled red in the applied algorithms (b&f), manually counted cells are labeled on digitally captured slides by enumeration in green font (d). IF blue signal reveals nuclei stained with DAPI, red CD3 signal and green GZB signal, 40 × magnification (g). Histiocytic sarcoma, HS; immunohistochemical, IHC; granzyme B, GZB; immunofluorescence, IF; diaminobenzidine chromogen, DAB; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, DAPI

Fig. 3.

Heavily infiltrated pulmonary HS in a 6-year-old male-neutered greyhound. a IHC staining for CD3 and b application of nuclear quantification algorithm, c IHC staining for GZB and d manual quantification of digitally captured image, e IHC staining for FOXP3, and f application of nuclear quantification algorithm, g IF of nuclei, CD3 and GZB. IHC staining detected using DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin, scale bars—70 µm, negatively stained cells are labeled blue and positively stained cells labeled red in the applied algorithms (b&f), manually counted cells are labeled on digitally captured slides by enumeration in green font (d). IF blue signal reveals nuclei stained with DAPI, red CD3 signal and green GZB signal, 40 × magnification (g). Histiocytic sarcoma, HS; immunohistochemical, IHC; granzyme B, GZB; immunofluorescence, IF; diaminobenzidine chromogen, DAB; 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, DAPI

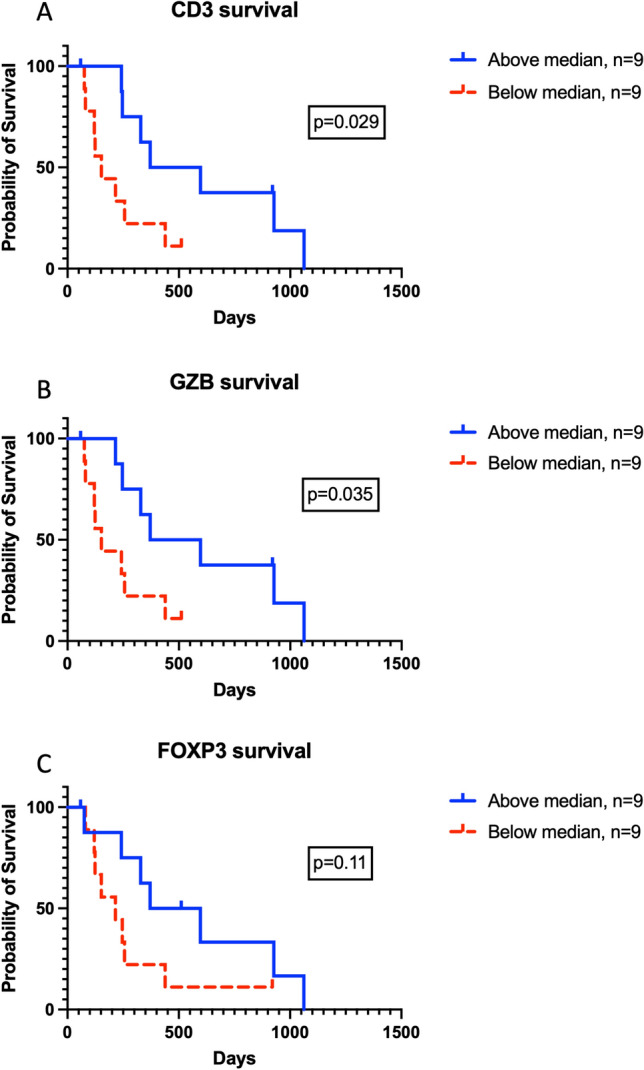

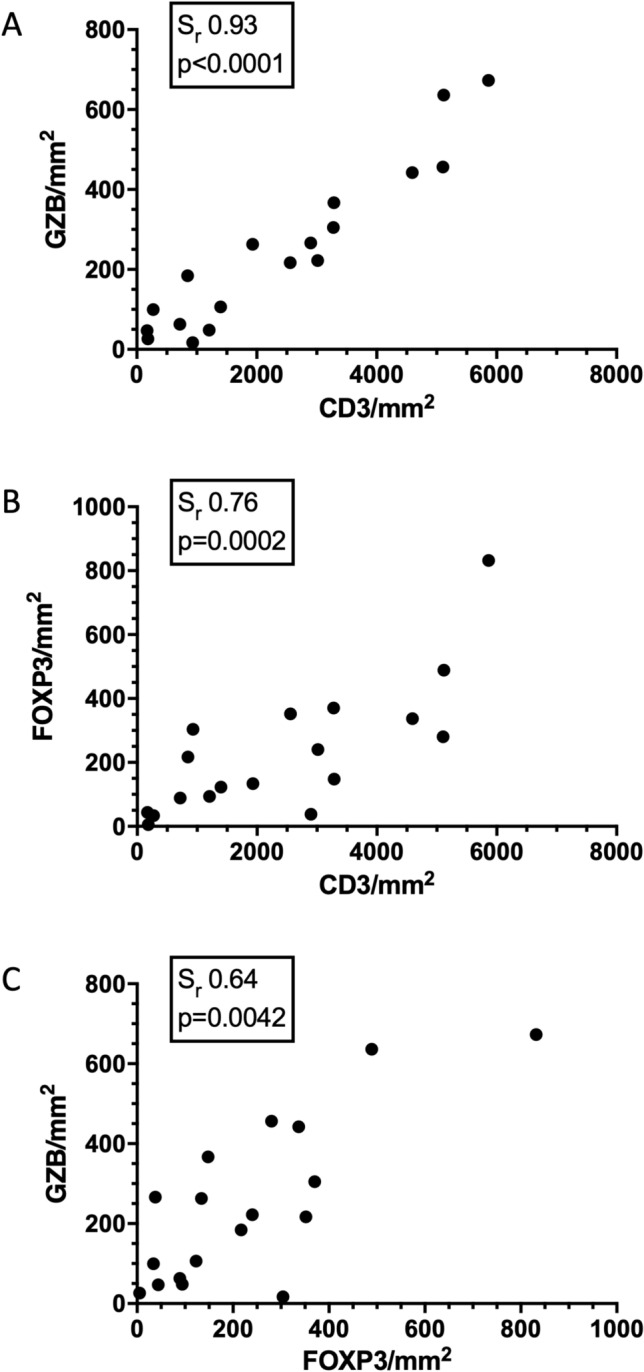

Increased TIL density is positively associated with favorable clinical outcome

We predicted that increased density of CD3 and GZB would be positively associated with survival, but that increased density of FOXP3 Treg cells would negatively impact outcomes. Increased densities of CD3 and GZB positive cells were associated with statistically significant prolongations of survival (Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, a non-statistically significant trend toward increased density of FOXP3 being associated with increased survival times was recorded (Fig. 4c). A very strong positive correlation between CD3 and GZB TIL density was observed (Fig. 5a), with strong correlations noted between CD3 and FOXP3 (Fig. 5b) density as well as FOXP3 and GZB (Fig. 5c). Taken together these data reveal a spectrum of immunologically cold and hot tumors in canine HS with increased T cell inflammation associated with prolonged survival times.

Fig. 4.

Tumor-specific survival times stratified by TIL densities. a CD3 positive TIL counts, b GZB positive TIL counts, and c FOXP3 TIL counts. Displayed p values calculated using log-rank test. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, TIL; Granzyme B, GZB

Fig. 5.

Canine HS ranges along a spectrum of immunologically cold to hot tumors. Scatter plots for 18 canine histiocytic sarcoma patients revealing correlations between a CD3 and GZB TIL density, b CD3 and FOXP3 density, and c FOXP3 and GZB density. Sr and p values displayed for each plot. Histiocytic sarcoma, HS; Granzyme B, GZB

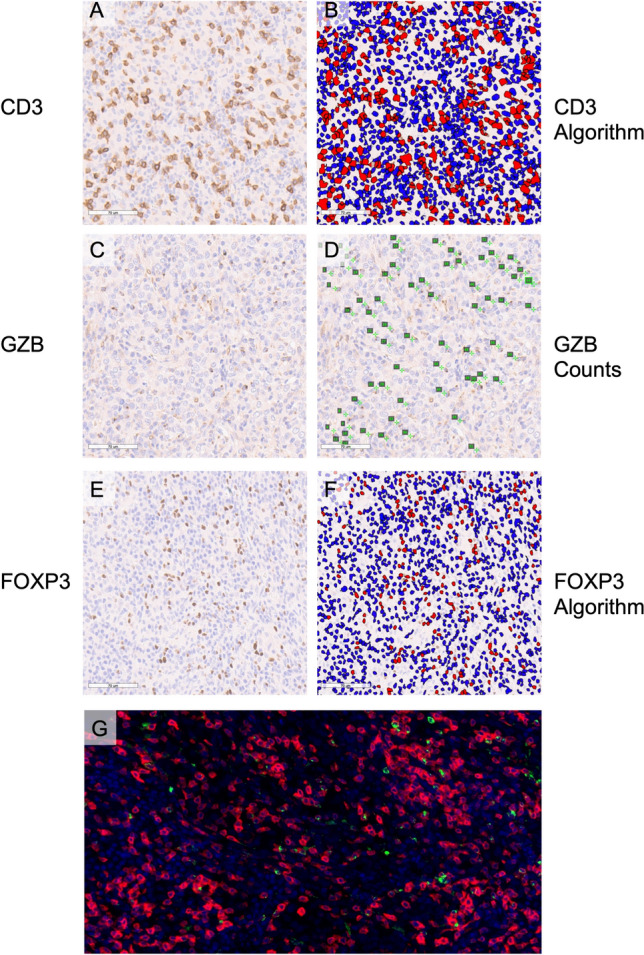

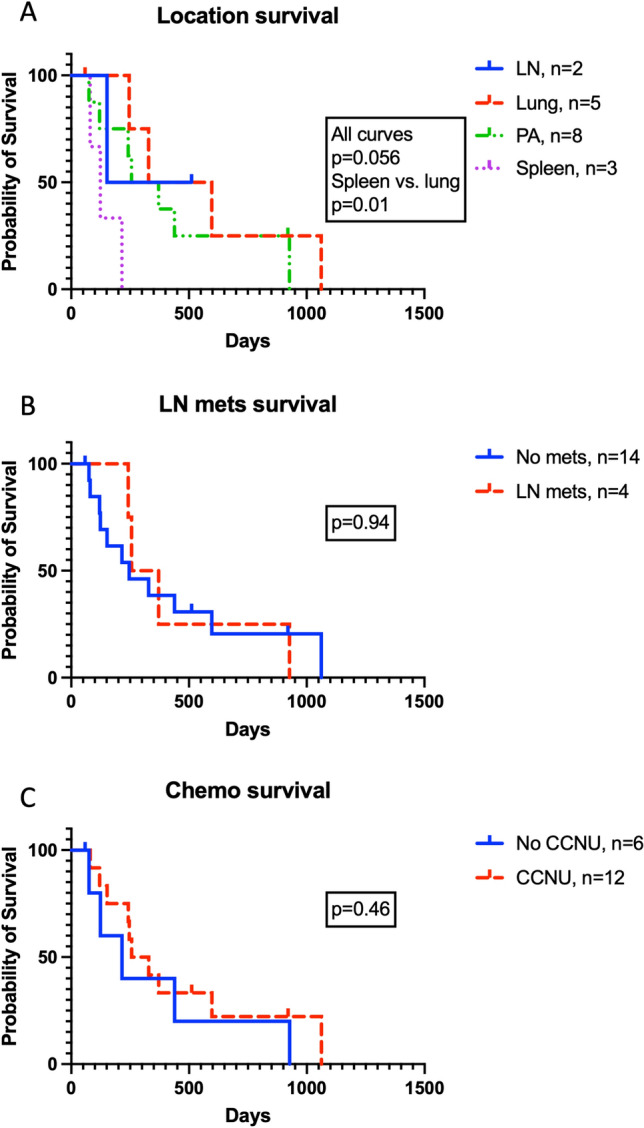

Divergence of pulmonary and splenic HS by TIL density and immune TME

Having established the prognostic relevance of TIL infiltration on disease outcome, we decided to analyze the effect of other clinicopathologic and therapeutic variables on disease progression. These included tumor location, presence of nodal metastases at diagnosis, and adjunctive treatment with chemotherapy (Fig. 6, Table S3). There was no significant difference in survival when all locations were analyzed using the log-rank test. However, when individual curves were compared, pulmonary HS patients survived significantly longer than splenic HS patients (Fig. 6a). Tumor-specific survival times were not impacted by the presence of nodal metastases (Fig. 6b) nor the inclusion of systemic CCNU chemotherapy (Fig. 6c). As dogs with pulmonary HS had a greater survival time compared to those with primary splenic disease, we hypothesized that pulmonary tumors would contain more TILs relative to splenic variants. We observed heavy T cell infiltrate in lung tumors (Figs. 7a, b) compared to only mild T cell infiltrate in splenic disease (Figs. 7c, d). TIL quantification confirmed significantly greater numbers of CD3 positive cells in primary lung HS compared to primary splenic HS (Fig. 7e). Collectively these data indicate that disease outcomes are associated with variable TIL density and distinct anatomic locations, but not the presence of nodal metastases or the inclusion of adjunct chemotherapy. Granzyme B (p = 0.023) and splenic location (p = 0.024) remained significant when included in subsequent models with additional predictor variables, including presence of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.57) and treatment with CCNU chemotherapy (p = 0.44). In order to further investigate the influence of tumor location on the immune TME in a comprehensive and unbiased manner, we performed transcriptional analyses on the three longest surviving dogs with pulmonary HS compared with three dogs with splenic HS. We documented multiple T cell transcripts as DE genes alongside a signature of higher expression of antigen presentation genes in the exceptional responders, interestingly complement related transcripts were also upregulated in pulmonary HS (Fig. 7f, Table S4). Taken together, these data confirm the significant association of TIL with outcome in spontaneous canine HS and revealed a pro-inflammatory TME in pulmonary HS compared to an immunosuppressive TME in splenic HS.

Fig. 6.

The impact of clinicopathologic and therapeutic variables on tumor-specific survival. Kaplan–Meier curves accounting for variables including a anatomic location of primary tumor, b the presence of nodal metastasis at diagnosis, and c inclusion of adjuvant CCNU chemotherapy. Displayed p values calculated using log-rank tests. Lymph node, LN; periarticular, PA; chloroethylcyclo-hexylnitrosourea (lomustine), CCNU

Fig. 7.

Pulmonary and splenic HS are dichotomized by T cell infiltration. Immunohistochemical staining for CD3 in pulmonary HS in a a 7-year-old male-neutered Rottweiler and b a 6-year-old male-neutered greyhound, and primary splenic HS in c an 11-year-old male standard poodle and d an 11-year-old male-neutered Rottweiler. e Quantification of CD3 GZB TIL in pulmonary and splenic HS. f Agglomerative cluster (heat-map) of differentially expressed (p < 0.05) genes following NanoString transcriptional profiling of the 3 longest surviving dogs with pulmonary HS compared with 3 dogs with splenic HS. Each column represents an individual patient with green color indicative of up-regulation, and red of down-regulation. IHC staining detected using DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin, scale bars = 4 mm, data mean ± SD, p values calculated using two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests. Histiocytic sarcoma, HS; diaminobenzidine chromogen, DAB

Discussion

In this study, we reveal that human and localized canine HS is variably infiltrated by T cells and that increased TIL density in these tumors is associated with a favorable outcome when canine HS is treated definitively. With the exception of tumor site, no other variables assessed impacted upon survival times, underscoring the importance of anti-tumor immunity in determining the outcome of current treatments for localized canine HS. As such, TIL density provides an important, potentially predictive indicator for this disease, in which histologic features have thus far not been prognostic. As canine HS bears a striking biologic and genetic resemblance to the human disease and as these dogs develop tumors spontaneously in the presence of an intact immune system, these data introduce the dog as a powerful model in which to study anti-tumor immunity in an orphan disease with a frequently dismal prognosis.

To characterize TIL infiltrate, we used CD3, a pan T cell marker, alongside GZB, a key effector serine protease, and FOXP3, the master transcriptional regulator of Tregs. The anti-tumor function of GZB is well established, as perforin/ GZB is the most potent mechanism that CTLs utilize to kill tumor cells [37]. Conversely, FOXP3 positive Tregs are classically associated with an immunosuppressive role, thereby promoting cancer progression [38]. As hypothesized, increased total TIL density and increased GZB were associated with improved clinical outcomes and there was a strong positive correlation between these markers. Somewhat surprisingly, there was also a non-significant trend of increased FOXP3 counts being associated with improved outcome. Interestingly, a meta-analysis by Bin Shang et al. [39] revealed that, while increased Treg infiltration was associated with poor survival times in people diagnosed with the majority of different solid tumors, the reverse was true for colorectal, head and neck, and esophageal cancers, suggesting the prognostic influence of infiltrating Tregs is in part defined by tumor type. Marcinowska et al. [33] documented the majority of TIL were FOXP3 positive in a study of HS in flat-coated retrievers, but no therapeutic outcome data were included. Our data reveal that there were approximately ten-fold greater total CD3 positive cells compared with FOXP3 labeled cells. Potential explanations for the difference between these studies may include geographical, breed, and disease-stage variations as the Marcinowska paper was restricted to a UK population of flat-coated retrievers, with many dogs presenting with advanced or disseminated disease necessitating euthanasia at the time of diagnosis or shortly thereafter. As we found significant and strong positive correlations between FOXP3 and CD3 as well as GZB, our data suggest that FOXP3 TIL infiltration in canine HS is one component of a diverse population of lymphocytes.

With the exception of TIL density, the only other variable that we found to be of prognostic relevance was anatomic location. Although analysis of this cohort resulted in small numbers of dogs with distinct anatomic locations, this finding is biologically cogent as another study found that dogs with splenic HS had significantly shorter median survival times compared to dogs with tumors in other locations and aligns with the clinical experience of the authors [17]. As numerous mechanisms can drive tumor progression by excluding T cells from the TME, thus resulting in immunologically barren neoplasms [40], we used a recently developed transcriptional profiling platform (NanoString) to investigate the influence of primary tumor site on the immune TME. Importantly, these analyses further strengthened the significance of T cell infiltration in dogs with pulmonary HS and prolonged survival times compared with splenic HS. We detected discrepancies in expression of multiple antigen presentation transcripts and down-regulation of such genes is a well-established mechanism by which tumors evade T cells [41]. Intriguingly, we also found a signature of increased complement in pulmonary HS, and although there is contradictory evidence for pro- versus anti-tumor activities of complement in cancer, both C3 and C5 components have important roles in antigen-presenting cell: T cell interactions [42]. Future prospective studies to further investigate and validate these findings in an independent cohort of dogs are planned.

Beyond the recent case report describing a favorable response in an HS patient treated with the immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) nivolumab [29], various other lines of evidence suggest that HS may be amenable to immunotherapy and specifically ICI. As TIL density serves as a biomarker for ICI responsiveness in various other tumor types [43, 44], the presence of TIL in the human tumors analyzed here supports ongoing evaluation of ICI for human HS. Similarly PD-L1 expression has prognostic relevance for the treatment of cancer patients with therapies targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 interactions [43, 44] with PD-1 [32], PD-L1 [32] and PD-L2 [32, 45] expression have been documented in human histiocytic malignancies. Expression of PD-L1 has also been detected in canine HS cell lines and primary canine tumor biopsy material [46]. Moreover, Tagawa et al. [47] demonstrated the presence of the checkpoint molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 on circulating T cells in dogs diagnosed with HS, supporting the potential utility of ICI in canine HS. Our collaborators here at the University of Pennsylvania are actively developing canine-specific ICIs, as are various other groups. Once available, canine HS will be an ideal model to preclinically appraise these drugs.

This study had some limitations. In epithelial tumors such as colorectal carcinoma, TIL at defined invasive margins are quantified separately to those in the center of the tumor [24, 48]. The uniform application and delineation of invasive margins in hematologic neoplasms, such as HS, is much more challenging and in some instances not possible. Therefore, we analyzed the entire tumor section as a whole, thus avoiding variability and inaccuracies in attempting to separate the peripheral invasive margins from central tissues in HS. Further, although adjuvant CCNU did not impact survival times in this cohort, it did result in some heterogeneity to the treatment of dogs in this retrospective study.

The reagents available to specifically interrogate the canine immune TME from FFPE tissues at a protein level are limited, for instance there are currently no well-described antibodies that recognize canine CD8 in FFPE tissues despite the availability of commercially available monoclonal antibodies that specifically bind canine CD8 T cells when used for flow cytometry [49]. Despite working up several anti-CD8 antibodies in FFPE tissues (data not shown), we were unable to identify a useful reagent in this setting. Prospective studies are planned to enable comprehensive phenotyping of circulating lymphocytes and isolation of lymphocytes from unfixed tumors allowing us to utilize a broader selection of canine reagents that will enable more comprehensive immunophenotypic profiling of TIL in canine HS [50]. We selected median values as cut-offs for stratifying high vs low TIL densities as previously described [24]; however, such stratification may not fully account for the complexity of the biology governing TIL densities. Ongoing projects will also allow us to validate our initial findings in a larger independent set of dogs diagnosed with HS by enabling the performance of a more comprehensive multiple-variable model with the aim of defining prognostic cut-offs for TIL density.

Although prior HS studies have not revealed clear immune prognostic data, they have provided parallel evidence of molecules that are targetable by immunotherapy in both dogs and humans. In this study, we have quantified CD3 + TIL in human HS and observed comparable variations of TIL density in canine HS. Further studies regarding TIL phenotype and definitive prognostic implications for human HS are desirable but are impeded as HS is infrequently encountered in humans. However, having an accurate and widely available model system in which to screen anti-cancer immunotherapies would be highly valuable. Spontaneously occurring canine HS represents a novel and accessible model in which to further study the significance of anti-tumor immunity in this disease. Here, we show the importance of TIL in shaping the outcome of HS in dogs. By uncovering the significance of TIL on the prognoses of dogs with localized HS, we suggest that these dogs offer a much needed and widely available setting to study both the immunopathology of HS and act as a sentinel to appraise novel therapeutics. The ultimate goal of future work is to assess the potential of new and existing immunotherapies that target TIL, thereby generating vital toxicity and preclinical efficacy data. Studies are planned to further characterize and subsequently manipulate immune effector cells in dogs with HS. Data from such studies will aim to inform and maximize the chances of success of early phase clinical trials appraising the safety and activity of immunotherapies for this rare and highly aggressive malignancy in people.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

CD3, GZB and FOXP3 TIL densities for 18 dogs with spontaneous HS.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 138 KB)

CD3 densities in human and canine HS. Data mean ± SD, p-values calculated using two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests. Histiocytic sarcoma, HS.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 101 KB)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Leslie King for manuscript review and editing.

Authors’ contributions

JAL and MJA were responsible for conceptualization. JAL, CAA, ER and MJA performed methodology. JAL, CAA, VC, KL, SR, NSK, PJZ, RGM, ACD and MJA performed formal analysis and investigation. JAL, CAA and MJA were responsible for writing—original draft preparation. JAL, CAA, NSK, ACD, ER and MJA were responsible for writing—review and editing. JAL, RGM and MJA performed funding acquisition. JAL, CAA, KL, PJZ, RGM, ACD, ER and MJA collected resources. JAL and MJA performed supervision.

Funding

This study was conducted using internal funds provided to Jennifer A Lenz, Department of Clinical Sciences and Advanced Medicine, School of Veterinary Medicine; internal funds to Robert G Maki Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania and NCI funding supporting Matthew J Atherton (K08CA252619). The Penn Vet Comparative Pathology Core is supported by the Abramson Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016520). The scanner used for whole slide imaging and the image analysis software was supported by a NIH Shared Instrumentation Grant (S10 OD023465-01A1).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Précis: Human and canine histiocytic sarcoma biopsies were analyzed for T cell infiltrates. Increased density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was associated with improved outcomes following curative-intent treatment.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Lenz, Email: jlenz@upenn.edu

Matthew J. Atherton, Email: mattath@upenn.edu

References

- 1.Takahashi E, Nakamura S. Histiocytic sarcoma : an updated literature review based on the 2008 WHO classification. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2013;53(1):1–8. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Durkin M, Go RS, Goyal G. Histiocytic sarcoma: a population-based analysis of incidence, demographic disparities, and long-term outcomes. Blood. 2018;131(2):265–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-812495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornick JL, Jaffe ES, Fletcher CDM. Extranodal histiocytic sarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 14 cases of a rare epithelioid malignancy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(9):1133–1144. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000131541.95394.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pileri SA, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Banks P, Campo E, Chan JKC, et al. Tumours of histiocytes and accessory dendritic cells: an immunohistochemical approach to classification from the International Lymphoma Study Group based on 61 cases. Histopathology. 2002;41(1):1–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari J, Naqash AR, Munker R, El-Osta H, Master S, Cotelingam JD, et al. Histiocytic sarcoma as a secondary malignancy: pathobiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Eur J Haematol. 2016;97(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsujimura H, Miyaki T, Yamada S, Sugawara T, Ise M, Iwata S, et al. Successful treatment of histiocytic sarcoma with induction chemotherapy consisting of dose-escalated CHOP plus etoposide and upfront consolidation auto-transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2014;100(5):507–510. doi: 10.1007/s12185-014-1630-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gounder MM, Solit DB, Tap WD. Trametinib in histiocytic sarcoma with an activating MAP2K1 (MEK1) mutation. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(20):1945–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1511490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atherton MJ, Morris JS, McDermott MR, Lichty BD. Cancer immunology and canine malignant melanoma: a comparative review. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2016;169:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBlanc AK, Breen M, Choyke P, Dewhirst M, Fan TM, Gustafson DL, et al. Perspectives from man’s best friend: National Academy of Medicine’s Workshop on Comparative Oncology. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(324):324ps5–324ps5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atherton MJ, Lenz JA, Mason NJ. Sarcomas - a barren immunological wasteland or field of opportunity for immunotherapy? Vet Comp Oncol. 2020;18:447–470. doi: 10.1111/vco.12595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Affolter VK, Moore PF. Localized and Disseminated Histiocytic Sarcoma of Dendritic Cell Origin in Dogs. Vet Pathol. 2002;39(1):74–83. doi: 10.1354/vp.39-1-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenz JA, Furrow E, Craig LE, Cannon CM. Histiocytic sarcoma in 14 miniature schnauzers - a new breed predisposition? J Small Anim Pract. 2017;58(8):461–467. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abadie J, Hédan B, Cadieu E, De Brito C, Devauchelle P, Bourgain C, et al. Epidemiology, pathology, and genetics of histiocytic sarcoma in the Bernese mountain dog breed. J Hered. 2009;100(Suppl 1):S19–27. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson J, Hoather T, McKinley TJ, Wood JLN. Mortality in a cohort of flat-coated retrievers in the UK. Vet Comp Oncol. 2009;7(2):115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2008.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulmer AK, Mauldin GE. Canine histiocytic neoplasia: An overview. Can Vet J. 2007;48(10):1041–1050. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafson DL, Duval DL, Regan DP, Thamm DH. Canine sarcomas as a surrogate for the human disease. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;188:80–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skorupski KA, Clifford CA, Paoloni MC, Lara-Garcia A, Barber L, Kent MS, et al. CCNU for the treatment of dogs with histiocytic sarcoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21(1):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb02937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skorupski KA, Rodriguez CO, Krick EL, Clifford CA, Ward R, Kent MS. Long-term survival in dogs with localized histiocytic sarcoma treated with CCNU as an adjuvant to local therapy*. Vet Comp Oncol. 2009;7(2):139–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2009.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedan B, Thomas R, Motsinger-Reif A, Abadie J, Andre C, Cullen J, et al. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of canine histiocytic sarcoma: A spontaneous model for human histiocytic cancer identifies deletion of tumor suppressor genes and highlights influence of genetic background on tumor behavior. BMC Cancer. 2011;26(11):201. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hédan B, Rault M, Abadie J, Ulvé R, Botherel N, Devauchelle P, et al. PTPN11 mutations in canine and human disseminated histiocytic sarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(6):1657–1665. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada M, Hix JML, Corner S, Schall PZ, Kiupel M, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V. Targeting MEK in a translational model of histiocytic sarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2018;17(11):2439–2450. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarone L, Barutello G, Iussich S, Giacobino D, Quaglino E, Buracco P, et al. Naturally occurring cancers in pet dogs as pre-clinical models for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(11):1839–1853. doi: 10.1007/s00262-019-02360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fesnak AD, Levine BL, June CH. Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(9):566–581. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313(5795):1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautès-Fridman C, Galon J. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skala SL, Lucas DR, Dewar R. Histiocytic sarcoma: review, discussion of transformation from B-cell lymphoma, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(11):1322–1329. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0220-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picarsic JL, Chikwava K (2018) Foundations in diagnostic pathology, hematopathology. 3rd edn, Disorders of Histiocytes, Elsevier, pp 567–616.e4

- 28.Miranda RN, Medeiros LJ (2018) Diagnostic pathology: lymph nodes and extranodal lymphomas. 2nd edn, Histiocytic Sarcoma, Elsevier, pp 812–821

- 29.Bose S, Robles J, McCall CM, Lagoo AS, Wechsler DS, Schooler GR, et al. Favorable response to nivolumab in a young adult patient with metastatic histiocytic sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019;66(1):e27491. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taube JM, Klein A, Brahmer JR, Xu H, Pan X, Kim JH, et al. Association of PD-1, PD-1 ligands, and other features of the tumor immune microenvironment with response to anti-PD-1 therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(19):5064–5074. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gatalica Z, Bilalovic N, Palazzo JP, Bender RP, Swensen J, Millis SZ, et al. Disseminated histiocytoses biomarkers beyond BRAFV600E: frequent expression of PD-L1. Oncotarget. 2015;6(23):19819–19825. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marcinowska A, Constantino-Casas F, Williams T, Hoather T, Blacklaws B, Dobson J. T lymphocytes in histiocytic sarcomas of flat-coated retriever dogs. Vet Pathol. 2017;54(4):605–610. doi: 10.1177/0300985817690208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato Y, Murakami M, Hoshino Y, Mori T, Maruo K, Hirata A, et al. The class A macrophage scavenger receptor CD204 is a useful immunohistochemical marker of canine histiocytic sarcoma. J Comp Pathol. 2013;148(2–3):188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pierezan F, Mansell J, Ambrus A, Rodrigues HA. Immunohistochemical expression of ionized calcium binding adapter molecule 1 in cutaneous histiocytic proliferative, neoplastic and inflammatory disorders of dogs and cats. J Comp Pathol. 2014;151(4):347–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frazier JP, Bertout JA, Kerwin WS, Moreno-Gonzalez A, Casalini JR, Grenley MO, et al. Multidrug analyses in patients distinguish efficacious cancer agents based on both tumor cell killing and immunomodulation. Cancer Res. 2017;77(11):2869–2880. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martínez-Lostao L, Anel A, Pardo J. How do cytotoxic lymphocytes kill cancer cells? Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(22):5047–5056. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Facciabene A, Motz GT, Coukos G. T regulatory cells: key players in tumor immune escape and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2012;72(9):2162–2171. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shang B, Liu Y, Jiang S, Liu Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;14(5):15179. doi: 10.1038/srep15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Joyce JA, Fearon DT. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science. 2015;348(6230):74–80. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa6204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dersh D, Hollý J, Yewdell JW. A few good peptides: MHC class I-based cancer immunosurveillance and immunoevasion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21(2):116–128. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Afshar-Kharghan V. The role of the complement system in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(3):780–789. doi: 10.1172/JCI90962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yi M, Jiao D, Xu H, Liu Q, Zhao W, Han X, et al. Biomarkers for predicting efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0864-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibney GT, Weiner LM, Atkins MB. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):e542–e551. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, Sun HH, Fletcher CDM, Hornick JL, Morgan EA, Freeman GJ, et al. Expression of programmed cell death 1 ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) in histiocytic and dendritic cell disorders. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40(4):443–453. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartley G, Faulhaber E, Caldwell A, Coy J, Kurihara J, Guth A, et al. Immune regulation of canine tumour and macrophage PD-L1 expression. Vet Comp Oncol. 2017;15(2):534–549. doi: 10.1111/vco.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tagawa M, Maekawa N, Konnai S, Takagi S. Evaluation of costimulatory molecules in peripheral blood lymphocytes of canine patients with histiocytic sarcoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0150030. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galon J, Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK, Berger A, Lagorce C, et al. Towards the introduction of the ‘Immunoscore’ in the classification of malignant tumours. J Pathol. 2014;232(2):199–209. doi: 10.1002/path.4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Panjwani MK, Atherton MJ, MaloneyHuss MA, Haran KP, Xiong A, Gupta M, et al. Establishing a model system for evaluating CAR T cell therapy using dogs with spontaneous diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1676615. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1676615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dow S. A role for dogs in advancing cancer immunotherapy research. Front Immunol. 2019;10:293510. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CD3, GZB and FOXP3 TIL densities for 18 dogs with spontaneous HS.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 138 KB)

CD3 densities in human and canine HS. Data mean ± SD, p-values calculated using two-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests. Histiocytic sarcoma, HS.

Supplementary file2 (PDF 101 KB)