INTRODUCTION

Studies of racial and ethnic disparities in the management and treatment of joint pain demonstrate a significant burden of disease and decreased treatment access among minorities1. Black and Hispanic patients have been shown to have decreased access to symptom alleviating medications and definitive surgical treatment for joint pain2–4. While these disparities are complex in origin, factors including discrepancies in patient education, poor physician communication, and implicit physician bias in treatment decisions likely play a role5. Although culturally competent care may mitigate these disparities5 by providing healthcare services that are respectful and responsive to the cultural and linguistic beliefs/needs of diverse patient populations6, few studies have actually investigated racial and ethnic differences in access to culturally competent care among patients with joint pain and various rheumatologic conditions.

METHODS

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) was queried for patients in 2017 who answered “yes” to the following: (1) “Had pain/aching at joints in the past 30 days;” (2) “Ever saw a doctor for joint symptoms;” (3) “Ever told you had arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia7.” Questions regarding provider cultural competence served as a proxy for patient preference and access to culturally competent care (Table 1)7, 8. Likert scale responses were binarized to very important/somewhat important vs. slightly important/not important at all.

Table 1.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Rates of Patient-Reported Measurements of Healthcare Provider’s Cultural Competency in Patients with Self-reported History of Joint Pain or Rheumatologic Conditions

| Black | Hispanic | Asian | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with joint pain or aching in the last 30 days | OR 95% (CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Perceived importance that HCP shares or understands patient culture | 2.34 (1.93–2.85) | <0.001 | 2.31 (1.87–2.87) | <0.001 | 3.03 (2.17–4.23) | <0.001 |

| Access to HCP who shares or understands culture | 0.37 (0.28–0.48) | <0.001 | 0.37 (0.27–0.5) | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.19–0.45) | <0.001 |

| Respectful treatment | 1.1 (0.71–1.70) | 0.67 | 0.94 (0.57–1.55) | 0.808 | 0.51 (0.24–1.07) | 0.073 |

| Easily understandable health information | 1.21 (0.88–1.65) | 0.24 | 0.65 (0.47–0.9) | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.27–0.72) | 0.001 |

| Asked for beliefs or opinions regarding to care | 1.28 (1.06–1.56) | 0.01 | 0.97 (0.79–1.21) | 0.811 | 1.41 (1.01–1.98) | 0.046 |

| Patients who have ever seen a physician for joint pain | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Perceived importance that HCP shares or understands patient culture | 2.38 (1.91–2.96) | <0.001 | 2.48 (1.91–3.23) | <0.001 | 3.45 (2.29–5.21) | <.000 |

| Access to HCP who shares or understands culture | 0.37 (0.27–0.5) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.27–0.55) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.18–0.49) | <.0010 |

| Respectful treatment | 1.07 (0.66–1.75) | 0.78 | 0.99 (0.52–1.89) | 0.98 | 0.52 (0.2–1.33) | 0.174 |

| Easily understandable health information | 1.11 (0.78–1.58) | 0.57 | 0.64 (0.43–0.97) | 0.034 | 0.58 (0.31–1.07) | 0.079 |

| Asked for beliefs or opinions regarding to care | 1.17 (0.95–1.46) | 0.144 | 1 (0.78–1.3) | 0.97 | 1.3 (0.86–1.96) | 0.217 |

| Patients who were ever told they had a rheumatologic condition | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p |

| Perceived importance that HCP shares or understands patient culture | 2.47 (2–3.04) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.76–3) | <0.001 | 3.71 (2.37–5.82) | <.0010 |

| Access to HCP who shares or understands culture | 0.38 (0.28–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.32 (0.22–0.46) | <0.001 | 0.36 (0.2–0.64) | 0.001 |

| Respectful treatment | 0.92 (0.56–1.5) | 0.733 | 1.01 (0.56–1.84) | 0.967 | 0.3 (0.13–0.66) | 0.003 |

| Easily understandable health information | 0.88 (0.62–1.25) | 0.46 | 0.76 (0.48–1.21) | 0.251 | 0.61 (0.32–1.17) | 0.135 |

| Asked for beliefs or opinions regarding to care | 1.14 (0.93–1.41) | 0.206 | 0.95 (0.73–1.25) | 0.718 | 1.54 (0.95–2.48) | 0.077 |

Patients with a self-reported history of joint pain within the last month and/or rheumatologic conditions responded to the following survey questions on physician cultural competency: (1) Some people think it is important for their healthcare providers (HCPs) to understand or share their race or ethnicity or gender or religion or beliefs or native language. How important is it to you that your healthcare providers understand or are similar to you in any of these ways? (2) How often were you able to see healthcare providers who were similar to you in any of these ways? (3) “How often were you treated with respect by your healthcare providers?” (4) “How often did your healthcare providers tell or give you information about your health and healthcare that was easy to understand?” (5) How often did your healthcare providers ask for your opinions or beliefs about your medical care or treatment?” Answers were binarized into two groups very important/somewhat important vs. slightly important/not important at all for questions about patient preferences, or always/most of the time vs. some of the time/none of the time for questions about frequency of access. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) were adjusted for sociodemographic variables including age, sex, race (non-Hispanic White, non-White Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and Asian), sexual orientation (straight, lesbian or gay, bisexual, other), family income, primary insurance status (insured vs. uninsured), highest level of education (8th grade or less, some high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, professional graduate), and baseline self-reported health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor). HCP healthcare provider

Sample-weight adjusted multivariable logistic regressions defined adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated to assess differences in answers to questions of cultural competence, with race and ethnicity as primary independent variables of interest, while controlling for various patient demographic factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 15.1 (StataCorp) with α=0.05. This study was exempt from our Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

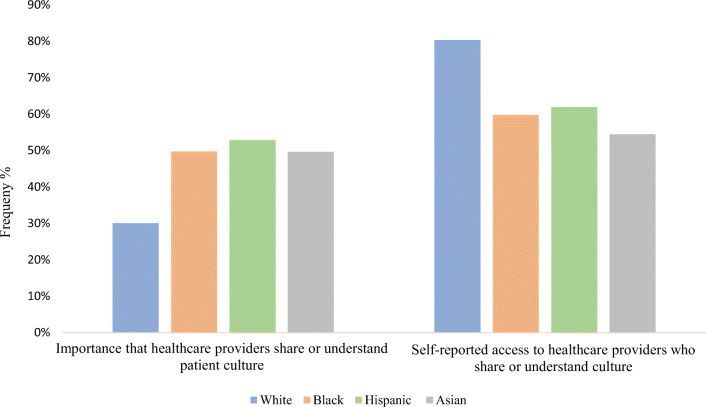

Eight thousand five hundred twenty-three patients with self-reported rheumatologic conditions were included, of whom 77% of patients were White, 9% were Hispanic, 8% were non-Hispanic (NH) Black, 3% were Asian, and 3% were other. Sixty percent of our patient sample was female, 5% were uninsured, and the median age was 58.2 years (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted rates of patient-reported measurements of healthcare provider’s cultural competency in patients with joint pain or aching in the last 30 days. Patients with a self-reported history of joint pain within the last month responded to the following survey questions on physician cultural competency: (1) Some people think it is important for their providers to understand or share their race or ethnicity or gender or religion or beliefs or native language. How important is it to you that your healthcare providers understand or are similar to you in any of these ways? (2) How often were you able to see healthcare providers who were similar to you in any of these ways? Answers were binarized into two groups very important/somewhat important and slightly important/not important at all.

Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients with a self-reported history of joint pain within the last month were more likely to report that it was very/somewhat important for their healthcare providers to share or understand their culture when compared to white patients (AOR=2.34, 95% CI=[1.93–2.85] Blacks, AOR=2.31 [1.87–2.87] Hispanics, AOR=3.03 [2.17–4.23] Asians, p<0.001 for all, Table 1). These patients were, however, less likely to report having access to healthcare providers who shared or understood their culture (AOR=0.37 [0.28–0.48] Blacks, AOR=0.37 [0.27–0.50] Hispanics, AOR=0.29 [0.19–0.45] Asians, p<0.001 for all, Table 1).

Hispanic and Asian patients were also less likely to report receiving easily understandable health information from their providers (p≤0.01, Table 1). Black and Asian patients were more likely to report being asked for their beliefs or opinions regarding their care (p≤0.001, Table 1). Similar differences among racial/ethnic groups were found for patients who had ever seen a doctor for joint pain and patients who were ever diagnosed with a rheumatologic condition (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Minorities including Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients with joint pain or a history of a rheumatologic condition were more likely to value cultural competency compared to White patients but were less likely to report actually having access to healthcare providers who understood their culture. These findings are concerning given the importance of effectively communicating treatment options in patient populations that already face significant structural barriers to accessing care4.

Longstanding systemic barriers preventing equal access to care may help explain these disparities; however, improving diversity within the pool of healthcare providers treating joint pain and other rheumatologic conditions may play a significant role in increasing access to culturally competent care for minority patients. Efforts are needed to diversify a workforce of rheumatologists that is currently less than 3% Black and 7% Hispanic9 and to recruit ethnically and racially representative healthcare providers treating rheumatologic conditions. Moving forward, emphasis should also be placed on increasing cultural humility training for both attendings, residents, and medical students as detailed by the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) guidelines6. Although our study has several strengths, it is limited by its retrospective nature and its reliance on self-reporting and occasional use of translators, as well as possible confounders not included in the model.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Ethnic differences in pain and pain management. Pain Manag. 2012;2(3):219–230. doi: 10.2217/pmt.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mossey JM. Defining racial and ethnic disparities in pain management. In: Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. Vol 469. Springer New York LLC; 2011:1859-1870. 10.1007/s11999-011-1770-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Amen TB, Varady NH, Rajaee S, Chen AF. Persistent racial disparities in utilization rates and perioperative metrics in total joint arthroplasty in the U.S. J Bone Joint Surg. 2020;102(9):811–820. doi: 10.2106/jbjs.19.01194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riad M, Dunham DP, Chua JR, et al. Health disparities among hispanics with rheumatoid arthritis: Delay in presentation to rheumatologists contributes to later diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26(7):279–284. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brach C, Fraserirector I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(SUPPL. 1):181–217. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001s09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Washington DC. National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health Care FINAL REPORT; 2001. [PubMed]

- 7.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey, 2017. Public-use data file and documentation. 2018;(June). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm.

- 8.Terlizzi EP, Connor EM, Zelaya CE, Ji AM, Bakos AD. Reported Importance and Access to Health Care Providers Who Understand or Share Cultural Characteristics With Their Patients Among Adults, by Race and Ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/index.htm. Accessed January 10, 2021. [PubMed]

- 9.Table 12 and 13. Practice Specialty, Females/Males by Race/Ethnicity, 2018 | AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-12-practice-specialty-females-race/ethnicity-2018 and https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/table-13-practice-specialty-males-race/ethnicity-2018. Accessed September 30, 2020.