Abstract

Penicillium marneffei is recognized as one of the most frequently detected opportunistic pathogens of AIDS patients in northern Thailand. We undertook a genomic epidemiology study of 64 P. marneffei isolates collected from immunosuppressed patients by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) with restriction enzyme NotI. Among the 69 isolates fingerprinted by PFGE, 17 were compared by HaeIII restriction endonuclease typing. The PFGE method demonstrated a higher degree of discriminatory power than restriction endonuclease typing with HaeII. Moreover, an impressive diversity of P. marneffei isolates was observed, as there were 54 distinct macrorestriction profiles among the 69 isolates of P. marneffei. These profiles were grouped into two large clusters by computer-assisted similarity analysis: macrorestriction pattern I (MPI) and MPII, with nine subprofiles (MPIa to MPIf and MPIIa to MPIIc). We observed no significant correlation between the macrorestriction patterns of the P. marneffei isolates and geographical region or specimen source. It is interesting that all isolates obtained before 1995 were MPI, and we found an increase in the incidence of infections with MPII isolates after 1995. We conclude that PFGE is a highly discriminatory typing method and is well suited for computer-assisted analysis. Together, PFGE and NotI macrorestriction allow reliable identification and epidemiological characterization of isolates as well as generate a manageable database that is convenient for expansion with information on additional P. marneffei isolates.

Penicilliosis marneffei is a disemminated and progressive infection caused by a dimorphic fungus, Penicillium marneffei (6). P. marneffei infections are increasingly common in Southeast Asia, particularly Thailand (3, 12), southern China (4, 8), and Hong Kong (14). With the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) into northern Thailand, approximately 1,115 cases of penicilliosis marneffei associated with HIV infection were diagnosed at Chiang Mai University Hospital in Chiang Mai, Thailand, over a 7-year period (10). There, the disease was the third most common opportunistic infection after tuberculosis and cryptococcosis (13). The routes and mechanism of infection by P. marneffei are still poorly understood, but the original infection was possibly through inhalation of conidia. In addition to the infection in humans, P. marneffei was also reported to be isolated from the internal organs of the bamboo rat. In Thailand, the first survey was carried out in the central plains from June to September 1987 (1). Thirty-one small bamboo rats (Cannomys badius) and eight hoary bamboo rats (Rhizomys pruinosus) were trapped. P. marneffei was isolated from the internal organs of 6 (19%) C. badius and 6 (75%) R. pruinosus rats. Notably, the rats did not show any signs or symptoms of the disease like those found in humans, but they might serve as natural reservoirs for P. marneffei.

A recent molecular biology-based study based on HaeIII restriction endonuclease analysis has led to the division of P. marneffei from northern Thailand into two DNA types (15). Evaluation of 22 human isolates revealed that 16 (72.7%) were of type I and 6 (27.3%) were of type II. Since only two genotypes accounted for the majority of isolates, further analysis was necessary to differentiate strains of the same DNA type more effectively. In the present study, we used pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) in an attempt to characterize P. marneffei isolates recovered from AIDS patients from several regions in Thailand. PFGE is based on the digestion of chromosomal DNA with a restriction endonuclease that cleaves infrequently and that produces only a few high-molecular-weight fragments that can be separated under special conditions of electrophoresis. PFGE has been demonstrated to have advantages in discriminatory power, typeability, and reproducibility (2, 9) and has been widely used to investigate epidemics of several fungi (11). We also assessed the performance of the PFGE technique by comparing the results of PFGE with those of restriction endonuclease typing of P. marneffei previously reported by Vanittanakom et al. (15).

Fungal isolates.

Sixty-four clinical isolates of P. marneffei from 62 patients with sporadic cases of infection were used for the genotypic study. Among these isolates, 14 were obtained from Lanna Medical Laboratory in the city of Chiang Mai, which is in northern Thailand. These isolates were recovered from patients who lived in Muang District, Maerim District, and Hang Dong District, which are in Chiang Mai Province. Twenty-three isolates were from Microbiology Laboratory, Prince of Songkla Hospital, which is in the city of Songkla, in southern Thailand, and the remaining 27 isolates were from several hospitals located in the central region of the country. Most patients who were admitted to Prince of Songkla Hospital were from Muang District, Haad Yai District, and Ranode District, which are in Songkla Province. Four isolates were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Two isolates (isolates ATCC 64101 and ATCC 24100) were clinical isolates, and the others (isolates ATCC 64102 and ATCC 18224) were from bamboo rats. Isolate ATCC 18244 was obtained from the liver of a Rhizomys sinensis rat captured in Vietnam in 1956, whereas isolate ATCC 64102 was obtained from the lung of an R. pruinosus rat captured in China in 1986. The details about each isolate obtained from the different geographical regions of Thailand are summarized in Table 1. Three clinical isolates (isolates 13, 14, and 15) were obtained from the skin, blood, and liver, respectively, of a patient from southern Thailand. Other bamboo rat isolates were gifts from Samaniya Sukroongreung, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. These isolates were obtained in 1987 (1). The isolates were recovered from different internal organs of one bamboo rat and displayed the same macrorestriction pattern. As a result, only one bamboo rat isolate was chosen as a representative isolate. Every isolate was cultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar and was incubated at 25°C for 1 to 2 weeks. To collect spores, 2 ml of 0.01% Tween 80 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) in sterile distilled water was added to each fully grown culture. Approximately 106 cells were inoculated into a 500-ml flat-bottom bottle containing Sabouraud dextrose broth. The cultures were incubated at 25°C in a gyratory shaker (New Brunswick Scientific Co., Inc.) set at 160 rpm for 2 days.

TABLE 1.

P. marneffei isolates used in the present study

| No. | Isolates | Yr of isolation | Source | Geographical origin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ATCC 18224 | 1956 | Bamboo rat liver (R. sinensis) | Vietnam | |

| 2 | ATCC 64102 | 1986 | Bamboo rat lung (R. pruinosus) | China | |

| 3 | ATCC 24100 | 1973 | Human spleen | United States | |

| 4 | ATCC 64101 | 1985 | Human | China | |

| 5 | PM-BR-49 | 1987 | Bamboo rat lung | Thailand | |

| 6 | PM-VV-2 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 7 | PM-AR-3 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 8 | PM-AR-4 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 9 | PM-AR-5 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 10 | PM-AR-6 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 11 | PM-AR-7 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 12 | PM-AR-8 | 1995 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 13 | PM-RT-12-1 | 1996 | Skin | Songkla | |

| 14 | PM-RT-12-2 | 1996 | Blood | Songkla | |

| 15 | PM-RT-12-3 | 1996 | Liver | Songkla | |

| 16 | PM-RT-13 | 1996 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 17 | PM-AR-14 | 1996 | Blood | Chiang Mai | |

| 18 | PM-RP-15 | 1984 | Oral cavity | Bangkok | |

| 19 | PM-RP-16 | 1984 | Oral cavity | Bangkok | |

| 20 | PM-RT-18 | 1996 | Skin | Songkla | |

| 21 | PM-AC-23 | 1995 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 22 | PM-AC-24 | 1995 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 23 | PM-RT-25 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 24 | PM-RT-26 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 25 | PM-RT-27 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 26 | PM-RT-28 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 27 | PM-RP-30 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 28 | PM-RT-33 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 29 | PM-RT-34 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla | |

| 30 | PM-SR-35 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 31 | PM-N-36 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 32 | PM-N-37 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok | |

| 33 | PM-BE-38 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi | |

| 34 | PM-BE-39 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi | |

| 35 | PM-BE-41 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 36 | PM-BE-42 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 37 | PM-BE-43 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 38 | PM-BE-44 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 39 | PM-RT-45 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 40 | PM-LN-46 | 1998 | Blood | Chiang Mai |

| 41 | PM-N-47 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 42 | PM-N-48 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 43 | PM-N-50 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 44 | PM-N-51 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 45 | PM-N-52 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 46 | PM-RP-53 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 47 | PM-RT-54 | 1998 | Bone marrow | Songkla |

| 48 | PM-RT-55 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 49 | PM-RT-56 | 1998 | Sputum | Songkla |

| 50 | PM-RT-57 | 1998 | Bone marrow | Songkla |

| 51 | PM-RT-58 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla |

| 52 | PM-N-59 | 1998 | Blood | Bangkok |

| 53 | PM-BE-60 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 54 | PM-BE-61 | 1998 | Lymph node | Nonthaburi |

| 55 | PM-BE-62 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 56 | PM-BE-63 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 57 | PM-RT-64 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla |

| 58 | PM-RT-65 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 59 | PM-RT-66 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 60 | PM-RT-67 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 61 | PM-RT-68 | 1998 | Blood | Songkla |

| 62 | PM-BE-69 | 1998 | Blood | Nonthaburi |

| 63 | PM-AR-70 | 1998 | Blood | Chiang Mai |

| 64 | PM-AR-71 | 1998 | Blood | Chiang Mai |

| 65 | PM-RT-72 | 1998 | Oral cavity | Songkla |

| 66 | PM-AR-73 | 1999 | Bone marrow | Chiang Mai |

| 67 | PM-AR-74 | 1999 | CSFa | Chiang Mai |

| 68 | PM-AR-75 | 1999 | CSF | Chiang Mai |

| 69 | PM-MK-76 | 1999 | Blood | Bangkok |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Preparation of DNA and PFGE.

Fungal mycelia (40 mg) were washed three times with 50 mM EDTA and suspended in 1 ml of cell wall lysis buffer containing 125 M EDTA, 50 mM sodium citrate, 25 μg of chitinase (Sigma-Aldrich) per ml, and 200 U of lyticase (Sigma) per ml. The mycelial suspension was mixed with low-melting-point agarose (SeaPlaque; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) to a final concentration of 1.0%. The mixture was cast into molds (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) and was allowed to solidify for 10 min at 4°C. The plugs were incubated in a buffer containing 0.4 M EDTA and 50 mM sodium citrate supplemented with 1% 2-mercaptoethanol for 24 h at 37°C, followed by three washings with 50 mM EDTA. The protoplasts in the plugs were disintegrated, and the proteins were degraded with lysis buffer (0.5 M EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 1% N-laurylsarcosine, 2 mg of proteinase K per ml) for 24 h at 50°C. The plugs were finally washed three times with 50 mM EDTA and were stored at 4°C until use.

Prior to restriction digestion, the plugs were treated twice with 1 ml of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 mM EDTA) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. Subsequently, the plugs were washed in TE buffer and were equilibrated with 1% restriction buffer for 2 h, and the DNA was finally digested at 37°C in 100 μl of restriction buffer containing 20 U of NotI (Promega, Madison, Wis.) for 2 h. The digested DNA plugs were loaded onto 1% SeaKem Gold agarose (FMC Bioproducts) and separated on a contour-clamped homogeneous electric field DR-III apparatus (Bio-Rad) in 0.5× TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer for 22 h at 14°C. Electrophoresis was done at 6 V/cm, the angle was 120 degrees, and ramp times were 10 to 50 s. The DNA size marker used was a bacteriophage ladder consisting of concatemers starting at 48.5 kb (Bio-Rad). After electrophoresis, the gels were stained in a solution of 1 mg of ethidium bromide per ml and were destained in electrophoresis buffer. The bands were visualized under UV light.

Data analysis.

The DNA banding patterns obtained were photographed with a digital camera (Vilber Lourmat, Mame Lavallec, France) and saved as TIFF files for use with BIO-PROFIL (Vilber Lourmat). Normalization was done according to the molecular weight standards on each gel, with one molecular weight standard being used for every six samples. Construction of similarity matrices was carried out by comparison of Dice coefficients (5). In all cases, the unweighted pair group method with average linkages was used to cluster the patterns.

HaeIII restriction endonuclease (RE) analysis.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of P. marneffei with restriction enzyme HaeIII was performed by the method previously described by Vanittanakom et al. (15), with some modification. In brief, protoplasts from 40 mg of fungal mycelia were suspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.3 M sodium acetate). After incubation at 65°C for 30 min, an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol was added and the upper aqueous phase was separated by centrifugation at 1,600 × g for 10 min. DNA was precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol and was finally suspended in TE buffer containing 50 μg of RNase A per ml. A digestion reaction was performed with the HaeIII restriction enzyme. After 1 h of incubation, electrophoresis was carried out for 3 h at 3 V/cm in a 1% agarose gel.

Results and discussion.

The experimental variation between duplicate experiments was determined for four replicate experiments with four P. marneffei strains. The reproducibility of PFGE was 97%, and only one pattern for each isolate was imported into BIO-PROFIL.

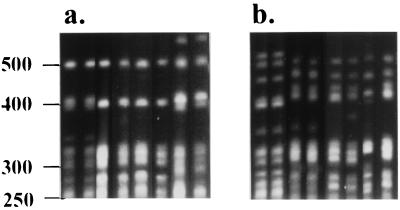

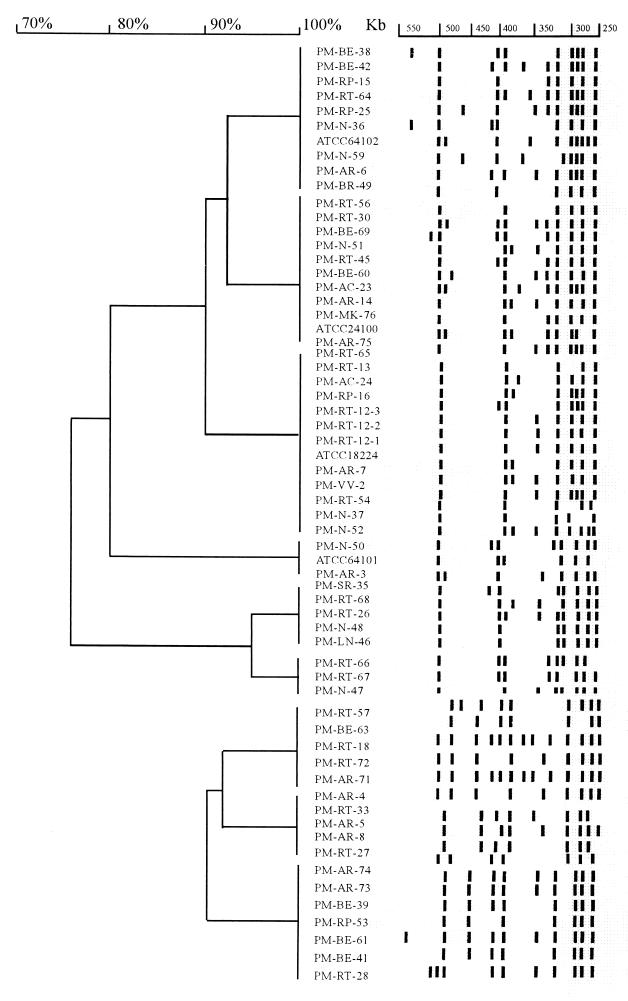

By using a cutoff value of 90%, PFGE analysis discriminated 54 different patterns and seven isolates proved ungroupable under the conditions used. The number of bands used to calculate levels of similarity between patterns ranged from 6 to 13 from 250 to 550 kb (Fig. 1). Although heterogeneity in macrorestriction patterns was observed, some of the macrorestriction patterns were quite similar, with only minor variations, usually with one band absent or present or with one band whose size had shifted. These variations were treated as separate PFGE profiles in the present study because a band-based analysis was used. The band-based Dice coefficient is based on a comparison of designated band positions and divides the number of matching bands between patterns by the total number of bands, thereby emphasizing the matching bands (5). In the present study, two large PFGE profile groups were observed by Dice coefficient analysis and were named macrorestriction pattern I (MPI) and MPII. MPI could be subdivided into six profiles (MPIa to MPIf), whereas MPII comprised three profiles (MPIIa to MPIIc) (Fig. 1). Among the 64 clinical isolates tested, 40 (70.2%) isolates were MPI and 17 (29.8%) were MPII.

FIG. 1.

PFGE pattern representations. (a) Lanes 1 to 8 (unnumbered, from left to right, respectively), P. marneffei isolates classified as MPI by cluster analysis; (b) lanes 1 to 8 (unnumbered, from left to right, respectively), isolates classified as MPII. Bacteriophage concatemer ladders (in kilobase pairs) are indicated to the left of the panel.

On the basis of the geographical distributions of the P. marneffei isolates (Table 2), seven isolates (53.8%) from northern Thailand were MPI and the other six isolates (46.2%) from the same region were MPII. Isolates from patients who lived in Muang District, Chiang Mai Province, displayed both the MPI and the MPII macrorestriction patterns. Only two isolates had identical NotI macrorestriction patterns. These two isolates were obtained from the bone marrow and cerebrospinal fluid of two patients, respectively (Table 1, isolates 66 and 67, respectively). Interestingly, the two patients were referred to Lanna Medical Laboratory within the same month in 1999, and both were from Muang District, Chiang Mai. Identical macrorestriction patterns were also detected for six other pairs of isolates (Fig. 2); nevertheless, these isolates had no relatedness to each another in terms of infection period or geographical distribution. Regarding isolates from southern Thailand, 14 isolates (70%) were MPI, whereas 6 isolates (30%) were MPII (Table 2). The six MPII isolates were recovered from patients whose residences were in Haad Yai District. Isolates from patients who resided in the other two districts of Songkla Province were of both macrorestriction patterns. Definitive conclusions about the macrorestriction patterns could not be made from the genotypic analysis of isolates from central Thailand, although 79.2% (19 of 24) of the isolates from central Thailand could be distinguished as MPI (Table 2). This was because the patients from whom these isolates were recovered often had a history of recent travel from elsewhere within the country. One interesting finding is that MPII isolates did not exist among the P. marneffei isolates obtained before 1995. Notably, since then the incidence of MPII had increased, i.e., from 28.6% in 1995 to approximately 50% in 1998 and 1999. However, with the limited number of isolates obtained before 1995, further assessments need to be done to confirm this observation.

TABLE 2.

Geographical distributions and macrorestriction patterns of P. marneffei isolates tested

| Origin of isolates tested | No. (%) of isolates

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | MI | MPII | Ungroupable | |

| Northern Thailand | 14 | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | 1 |

| Southern Thailand | 23 | 14 (70) | 6 (30) | 3 |

| Central Thailand | 27 | 19 (79.2) | 5 (20.8) | 3 |

| Total | 64 | 40 (70.2) | 17 (29.8) | 7 |

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram of PFGE patterns with designated bands. Cluster analysis was performed as described in the text. Isolates which were untypeable are not shown.

NotI macrorestriction analysis was also used to verify the clonal identities among the P. marneffei isolates from a patient who resided in southern Thailand. Three isolates were obtained from different organs of the patient during a single episode of penicilliosis marneffei. Identical macrorestriction pattterns were observed (Fig. 2, isolates PM-RT-12–1 to PM-RT-12–3). Additionally, we also analyzed whether there was a correlation between the macrorestriction pattern and the specimen source, but no such correlation was found other than the fact that most isolates from blood specimens were MPI.

The macrorestriction patterns of bamboo rat isolates appeared to be similar to those of human isolates and were MPI. Bamboo rat isolates from Thailand and from China (ATCC 64102) were MPIa. Another bamboo rat isolate obtained from Vietnam (ATCC 18224) was MPIc. PFGE analysis of paired P. marneffei isolates recovered from different body sites of each Thai bamboo rat revealed isolates with the same clonality (data not shown).

Previously, Vanittanakom et al. reported on an epidemiological typing method in which they used RE analysis with HaeIII to digest P. marneffei DNA (15). Only two DNA profiles (RFLP types I and II) were obtained in their study. To investigate the concordance between the methods, we used HaeIII RE analysis to type our isolates. We did not observe a good concordance between our PFGE results and HaeIII RE analysis results (Table 3). RE analysis demonstrated lower discriminatory power compared to that of PFGE. Fewer bands were obtained by HaeIII RE analysis, and only two patterns were generated by HaeIII RE analysis. PFGE, on the other hand, generated 14 individual patterns that could be grouped into nine subprofiles of macrorestriction patterns at a 90% level of similarity, providing a higher degree of resolution in discriminating among different fungal isolates. The lack of discrimination, which could raise problems of interpretation, especially in relation to strain dissemination, has been stated elsewhere (7). Hsueh and colleagues (7) recently reported on another molecular biology-based typing technique, random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis, that gave higher discriminatory power than the RFLP analysis reported by Vanittanakom et al. In that study, the investigators could clearly differentiate eight RAPD patterns among 20 P. marneffei isolates from Taiwanese patients. However, when RE analysis was used to type these clinical isolates, only two RFLP patterns were observed (six strains were RFLP type I and two strains were RFLP type II).

TABLE 3.

Repartition of HaeIII RE analysis groups into the eight macrorestriction subprofiles

| Type by HaeIII RE analysis | No. of strains with the following MP subprofiles:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPIa | MPIb | MPIc | MPId | MPIe | MPIIa | MPIIb | MPIIc | |

| I | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| II | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PFGE of P. marneffei genomic DNA digested with NotI has the advantage of a very high degree of discriminatory power together with perfect reproducibility. Different genotypes of P. marneffei could be clearly distinguished according to their NotI macrorestriction patterns. Because PFGE is a well-standardized method, it allows interlaboratory comparison of pulsotypes, evaluation of the true geographical distributions of P. marneffei isolates, and other genotypic analyses of P. marneffei for epidemiological purpose.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Development Agency and the Chulabhorn Research Institute, Bangkok, Thailand.

We gratefully acknowledge the supplies of the bamboo rat P. marneffei isolates from S. Sukroongreung (Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medical Technology, Mahidol University) and the clinical P. marneffei isolates from A. Chaiprasert (Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Mahidol University).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajello L, Padhye A A, Sukroongreung S, Nilakul C H, Tantimavanich S. Occurrence of Penicillium marneffei infections among wild bamboo rats in Thailand. Mycopathologia. 1995;131:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01103897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bostock A, Khattak M N, Matthews R, Burnie J. Comparison of PCR fingerprinting, by random amplification and polymorphic DNA, with other molecular typing methods for Candida albicans. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2179–2184. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiewchanvit S, Mahanupab P, Hirunsri P, Vanittanakom N. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated Penicillium marneffei mycosis in five HIV-infected patients. Mycoses. 1991;34:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1991.tb00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng Z, Ribas J L, Gibson D W, Conner D H. Infectious caused by Penicillium marneffei in China and Southeast Asia: review of eighteen published cases and report of four more Chinese cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1998;10:640–652. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dice L R. Measurement of the amount of ecological association between species. Ecology. 1945;26:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 6.DiSalvo A F, Fickling A M, Ajello L. Infection caused by Penicillium marneffei: description of first natural infection in man. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;60:259–263. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/60.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsueh P-R, Teng L-J, Hung C-C, Hsu J-H, Yang P-C, Ho S-W, Luh K-W. Molecular evidence for strain dissemination of Penicillium marneffei: an emerging pathogen in Taiwan. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1706–1712. doi: 10.1086/315432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J S, Pan L O, Wu S X, Su S X, Su S B, Shan L L. Disseminated penicilliosis marneffei in China. Report of three cases. Chin Med J. 1991;104:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magee P T, Bowdin L, Staudinger J. Comparison of molecular typing methods for Candida albicans. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2674–2679. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2674-2679.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sirisanthana T, Suppataratpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson K E. Amphotericin B and itraconazole for treatment of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1107–1110. doi: 10.1086/520280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soll D R. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:332–370. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.2.332-370.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Supparatpinyo K, Kwamwan C, Baosoung V, Nelson K E, Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in Southeast Asia. Lancet. 1994;344:110–113. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Supparatpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson K E, Srisanthana T. A controlled trial of itraconazole to prevent relapse of Penicillium marneffei infection in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1739–1743. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812103392403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang D N, Li P C, Tsui M S, Lau Y T, Ma K F, Yeah E K. Penicillium marneffei: another pathogen to consider in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:766–767. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.4.766-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vanittanakom N, Cooper C R, Chariyalertsak S, Youngchim S, Nelson K E, Sirisanthana T. Restriction endonuclease analysis of Penicillium marneffei. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1834–1836. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1834-1836.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]