Abstract

Young children with cleft palate with or without cleft lip (CL/P) are at risk for early vocabulary and speech sound production delays. Early intervention studies have shown some promising findings to promote early speech and vocabulary development following palate repair; however, we know little about how these interventions can be used in other international contexts (Kaiser et al., 2017; Scherer, Kaiser, et al., 2020). This study adapted an early speech and language intervention developed in the US, Enhanced Milieu Teaching with Phonological Emphasis (EMT+PE), to the Brazilian context at the Hospital for Rehabilitation of Craniofacial Anomalies at the University of São Paulo-Bauru. The purpose of this study was to compare the speech and language performance of 24 toddlers with CL/P randomized into an EMT+PE intervention group and a business-as-usual (BAU) comparison group over three time points: prior to, immediately following, and three months after intervention. Results immediately following intervention indicate gains in multiple measures of language. Three months following intervention, participants showed gains in both language and speech measures.

Keywords: cleft palate, early intervention, Enhanced Milieu Teaching, Brazilian Portuguese

Introduction

Cleft lip and/or palate (CL/P) is a frequently occurring condition that presents in one of every 500–700 births (World Health Organization, 2016). These children have early speech and vocabulary delays that can persist into school age (Scherer, D’Antonio, & Kalbliesch, 1999; Hardin-Jones & Chapman, 2011). A recent meta-analysis indicated that children with CL/P fall behind their peers in receptive and expressive language as well as speech through eight years of age (Lancaster et al., 2020). Early intervention is often recommended by cleft palate teams; however, there are only a few published studies of their efficacy (Scherer et al., 2008; Kaiser et al., 2017; Lancaster et al., 2020). In addition, there are few published studies of early intervention conducted in international contexts (Pamplona et al., 2004; Ha, 2015).

Speech and language development in children with CL/P

Vocabulary and speech sound development emerges simultaneously in early development and children with CL/P show delays in both vocabulary and speech as a result of their early structural deficits (Chapman, 2004). These early delays improve over time, but speech and language delays can continue into school age and can impact early reading acquisition (Chapman & Willadsen, 2011). While the focus of research has been on speech development, language differences have been described in early vocabulary development that persist through the preschool period (Scherer, 1999; Scherer et al., 2013; Kaiser et al., 2017). In addition to vocabulary, differences in sentence complexity and talking rate (word per minute) have been described (Kaiser et al., 2017; Frey et al., 2018). There is evidence to suggest that young children with CL/P are at higher risk for both receptive and expressive language deficits (Lancaster et al., 2020). While receptive language differences may be subclinical, they persist in the literature to early school age.

The relationship between early speech and vocabulary delays in children with clefts has focused on the restricted consonant inventories that limit vocabulary growth (Hardin-Jones & Chapman, 2014). However, the relationship may be bidirectional in that limited vocabulary reduces the opportunity to practice production of new words and sounds (Scherer, Kaiser & Frey, 2020). Further, approximately 30% of children with clefts will have velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD) and require secondary surgery (Peterson-Falzone et al., 2017; Zajac & Valino, 2017). The speech characteristics associated with VPD, including hypernasality on vowels, audible nasal emission on pressure consonants, and compensatory articulation errors (i.e., glottal stops, pharyngeal fricatives, nasal substitutions) are relatively easy to assess in older children. However, identifying early indications of VPD is not as straightforward for toddlers since some of these speech characteristics persist as learned behaviors after palate repair (Hardin-Jones et al., 2006). Further, the child’s age, maturation level, and presence of sufficient obstruents can impact definitive instrumental assessments.

These developmental differences observed in U.S. studies are also found in the Brazilian literature. A study conducted by the Hospital de Reabilitação em Anomalias Craniofaciais of the Universidade de São Paulo (HRAC-USP) in Brazil compared results of the Early Language Milestone Scale (ELMS) in children between 12 and 36 months with and without CL/P. Findings indicated that children with CL/P performed significantly lower in areas of receptive and expressive language when compared to typically developing peers (Lamônica et al., 2016). A recent study also developed at HRAC-USP analyzed the performance of gross motor, adaptive fine motor, personal-social, and language skills in 30 children with non-syndromic cleft lip and palate, aged from 36 to 47 months, compared to a typically-developing control group matched by age and gender. The Denver Developmental Screening Test II and MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (CDI) Section D were used to analyze developmental and language skills. The findings showed a significant difference in all tested skills between groups, except for the personal-social area, concluding that children with CL/P are at risk for developmental disorders (Cavalheiro et al., 2016). In older children from seven to nine years of age, Marcelino (2009) found that language abilities (oral and written) and auditory and visual abilities, such as memory, association, grammar and visual closure, language reception, receptive vocabulary, phonological processing, writing, arithmetic, reading, auditory attention, and processing performance were poorer than expected for the age in the majority of the children with CL/P. The Brazilian literature suggests that early speech and language delays persist into school age and may be associated with more general developmental concerns that could impact social and educational outcomes.

Early speech development has been characterized by limited consonant inventories, lower Percent Consonants Correct (PCC), persistence of developmental phonological errors and the presence of cleft-related speech errors (i.e., compensatory articulatory substitutions, nasal substitutions, nasal emission, hypernasality, and weak pressure consonants) (Jones et al., 2003; Chapman & Willadsen, 2011; Klinto, Salameh, Olsson, Flynn, Svensson & Lohmander, 2014). Children with clefts show developmental phonological patterns that are related to a developing or immature speech sound system and not thought to be related directly to the cleft. These errors include patterns of phonological processes characteristic of typical early development (e.g., fronting (t/k in cat), stopping (t/s in sun), final consonant deletion (ha for hat), simplification (nana for banana), assimilation (g/d in dog) (Willadsen et al., 2017). In addition to these developmental errors, toddlers may have errors that are commonly associated with velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). These errors may be a learned response to early anatomical deficits from the cleft or VPD (Sell, Harding, Grunwell, 1999). Glottal stop and pharyngeal fricative substitutions for stops and fricatives are one of the most common examples of the child’s attempt to compensate for inability to implode oral air pressure prior to palate repair. The errors may remain following palate repair as a learned substitution pattern or may be symptom of VPD. For toddlers, it may be difficult to discern the origin of compensatory patterns until sufficient language is present to assess the presence of VPD. Nasal substitutions (e.g., m/b or n/d), is another error pattern that is considered a symptom of VPD; however, it is also an error pattern observed frequently in noncleft toddlers and may or may not be related to the presence of VPD in toddlers with CLP (Hardin-Jones & Chapman, 2018). The presence of other signs of VPD that are related to structural deficits, are audible nasal emission (on pressure consonants), hypernasality (on vowels or pervasively in connected speech) and weak pressure consonants. Toddlers present a challenge to determine the origin of their speech errors and early intervention can provide an opportunity to facilitate vocabularies that contain early developing consonants permitting more detailed analysis of emerging patterns of sound production.

Interventions for children with CL/P

There are few intervention studies of children with CL/P and even fewer that focused on early intervention. Bessell et al. (2013) conducted a systematic review of speech interventions for individuals with cleft palate who received either a motor or linguistic approach to intervention. Motor approaches included non-speech oral-motor approaches or articulatory approaches that moved from sound to syllable-, word-, and phrase-level productions. Linguistic approaches included language approaches, such as focused stimulation, whole word, and phonological approaches. The results of the systematic review found some positive effects for both motor and linguistic approaches, but the limitations in methodology for many of the studies constrained the interpretation of findings.

Enhanced Milieu Teaching with Phonological Emphasis (EMT+PE) intervention has demonstrated positive speech and language outcomes for toddlers with clefts in the U.S. (Scherer et al., 2008; Kaiser et al., 2017; Scherer, Kaiser, et al., 2020). This approach combines vocabulary and speech sound targets in a single intervention approach which was particularly well-suited to the early speech and language delays of children with CL/P. EMT+PE utilizes naturalistic, conversationally-based strategies in the context of play and routines to target key speech sounds, based on individualized goals, through developmentally appropriate words and phrases. In a pilot study, Kaiser et al. (2017) and Scherer et al. (2020) administered EMT+PE to English-speaking children with CL/P across 48 sessions. Compared to a business-as-usual (BAU) group, children receiving EMT+PE made greater gains than BAU children on speech and vocabulary measures following the intervention. There was a differential effect of intervention, with the children who used at least seven words per minute (i.e., relatively higher vocabulary) making the greatest speech gains. As a note, BAU comparison groups are children who are receiving routine services in the community for that particular condition. So, children in the BAU comparison could potentially be getting other interventions (e.g., speech, language, physical/occupational therapies): however, children in this study were not receiving additional interventions but were receiving routine follow up in their cleft palate team.

Research questions

The purpose of the present study was to compare the speech and language performance of toddlers with CL/P randomized into an EMT+PE intervention or a business-as-usual (BAU) comparison group over three time points: prior to, immediately following, and three months after intervention. The following questions were investigated:

- Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate significant post-intervention and follow-up gains in the speech measures in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

- Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate a significant reduction in compensatory articulation (glottal stop, pharyngeal fricatives) and nasal substitutions in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate significant post-intervention and follow-up gains in language measures in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

Methods

This study was funded by NIDCD (Grant No: R03 DC013527) and approved by the Internal Review Boards of Arizona State University and the Hospital de Reabilitação de Anomalias Craniofaciais – Universidade de São Paulo (HRAC-USP).

Participants

A total of 24 children with CL/P participated in this study. The average age of palate repair was 14.1 months (11–19 months). The average age at baseline for participants was 24.5 months (20–34 months). Children were randomized into groups in such a way that the groups were optimally balanced with respect to pre-intervention age, expressive language standard score and number of consonants in the inventory in order to control the developmental performance within this age range. Participants varied by cleft type: unilateral cleft lip/palate (UCLP; n = 14), bilateral cleft lip/palate (BCLP; n = 3), and isolated cleft palate (ICP; n = 7). Individual participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Children were recruited from two sites at the time of palate repair: HRAC-USP and a satellite clinic in São Paulo, the Fundação para o Estudo e Tratamento das Deformidades Crânio-Faciais (FUNCRAF). Primary caregivers were provided information about the study and Brazilian speech-language pathologists (SLPs) contacted the families at regular intervals until 18 months to determine readiness for intervention.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Group

| Intervention group |

Control group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

|

| ||||

| Total number | 12 | 12 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 3 | 25% | 6 | 50% |

| Female | 9 | 75% | 6 | 50% |

| Cleft palate type | ||||

| Cleft palate only | 5 | 42.7% | 2 | 16.7% |

| Unilateral CL/P | 6 | 50% | 8 | 66.6% |

| Bilateral CL/P | 1 | 8.3% | 2 | 16.7% |

Note. CL/P = cleft lip and/or palate.

Participants were selected based on the following inclusionary/exclusionary criteria: (a) presence of a nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate, (b) aged 18 to 36 months at baseline, (c) demonstrated joint attention appropriate for verbal engagement and imitation skills by passing related items on the Avaliação do Desenvolvimento da Linguagem or Evaluation of Language Development (ADL; Menezes, 2004) (d) produced 10 distinguishable word approximations using Vihman criteria (Vihman, 1994), and (e) had their primary palate repair at 18 months of age or earlier. Children were excluded from the study if they: (a) had a sensorineural hearing loss or hearing thresholds ≥ 30-dB HL, as measured by an audiologist, (b) were multilingual or non-Portuguese speaking based on parent report, and (c) had more than three additional dysmorphic features in addition to the cleft or a syndrome diagnosis from a geneticist. Jones (1988) indicated that children with clefts who have three or more other anomalies should be considered as syndromic even though they may not have an identified syndrome.

Letters were provided to the primary caregivers describing the study. Consent was obtained by at least one of the child’s parents or guardians.

After meeting inclusionary criteria and providing consent, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental intervention (n = 12) or a business-as-usual comparison group (n = 12) using a covariate adaptive randomization procedure (Suresh, 2011; Weir & Lees, 2003). The goal of this method is to assign subjects to treatment or control as they enroll in the study in such a way that the groups are optimally balanced with respect to one or more desired characteristics. For our study chronological age (within two months) and expressive vocabulary were used as characteristics for the randomization. The Brazilian SLP who completed the assessment collected and scored the MacArthur CDI adapted for Brazilian Portuguese (Teixeira, 2000; Teixeira, 2019) to obtain a measure of expressive vocabulary within the clinical setting. A second Brazilian SLP rescored the CDI for accuracy. Comparison of pre-treatment vocabulary scores on the CDI showed that the groups did have a substantial range of scores (34–425); however, the groups were not significantly different (t=0.59, p= 0.28). Additionally, three participants dropped from the intervention group and two dropped from the BAU group prior to T1 due to the time commitment required in the project. Figure 1 shows the screening and enrollment process for the children in the study.

Figure 1.

Participant screening and enrollment process

Assessor/intervention training

All children were assessed for both speech and language development at three time points: baseline (T0), immediately following completion of the 12-week intervention (T1) and at a three-month follow-up after T1 (T2). Assessor training of Brazilian SLPs was accomplished in three phases. Phase 1 consisted of a foundational training of the lead Brazilian SLP by the primary investigator, including yearly in-person training (either in Brazil or the U.S.) on research skills (research design, data collection, progress monitoring and fidelity, assessment, and the EMT+PE intervention model) and five distance-learning training modules with video examples in English, training on research skills, professional reflection, and monthly video conferences to discuss and resolve training questions. A description of the elements of the training is provided in the Table 2. Phase 2 consisted of a mentorship approach to training, in which the lead SLP then trained local SLPs through a ‘coaching cycle’ (i.e., observation, modelling, and communication) with monthly video conferences, including the primary investigator, to discuss and resolve training questions. Phase 3 consisted of a sustainable approach to leadership development, in which the local team of Brazilian SLPs developed their own web-based repository in Brazilian Portuguese of the assessment techniques and intervention strategies. Criteria for completion of each training phase included both knowledge and skills competency, as demonstrated by a score of 90% on a competency-based assessment on the Canvas platform (knowledge) and 90% compliance on a 10-component EMT+PE fidelity checklist (skills). Three licensed Brazilian SLPs completed this training and one SLP administered speech and language assessments and two other SLPs delivered the intervention for the purposes of this study. Administration of each assessment was video and audio recorded.

Table 2.

Description of assessment and intervention training.

| Training Phase | Training Activities |

|---|---|

| Pre-Training | 1. Virtual meeting with the US and Brazilian research teams. 2. Overview of training schedule and activities. |

| Phase 1: Foundational Training | 1. Presentation of study design, methods for assessment and intervention and analysis. 2. Presentation on the covariate adaptive randomization procedure by statistician 3. Presentation and discussion of data management system 4. Reviewed fidelity and reliability methods and discussed modification. Assessed understanding of methodology on Canvas. 5. Discussed procedures for translating all training and intervention forms for the study. 6. Phonetic transcription practice and consensus training. Training presented and assessed on Canvas. 7. Screening and standardized assessment review. 8. Presentation on language sample collection and transcription procedures. Training presented and assessed on Canvas. |

| Phase 2:Intervention Training | 1. Research team completes 10 EMT+PE modules on the strategies. Competency-based knowledge assessment on Canvas to criterion of 90%. a. Environmental arrangement b. Responding to praise c. Responding to teach d. Modeling e. Expansions f. Speech recasting g. Requests h. Mirror and mapping i. Time delay j. Putting it all together 2. Choosing speech and language targets 3. Purchasing and organizing intervention materials 4. Parent training procedures and materials 5. Discussion and assessment of key readings on Canvas. 6. Practice EMT+PE strategies with feedback from US team. 7. 7. Two practice videos of each strategy were submitted by the Brazilian clinicians to the US team for fidelity measurement to criterion of 90%. Retraining occurred if fidelity fell below criterion. |

Speech and language assessment

Speech assessment and measures

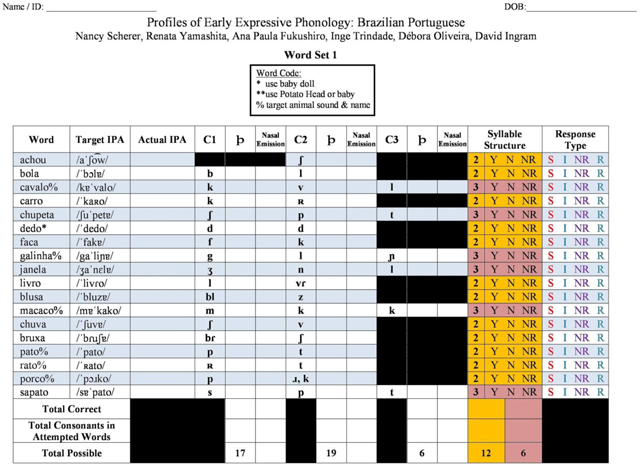

A Brazilian Portuguese adaptation of the Profiles of Early Expressive Phonological Skills (PEEPS:BP; Scherer et al., 2020; Scherer, Kaiser, et al., 2020; Stoel-Gammon & Williams, 2013) was administered to assess early speech development of populations with CL/P through the production of early acquired words (see Appendix). PEEPS:BP was constructed to represent the diversity of place, manner, voicing, and syllable and word shapes of Portuguese consonant production for children under three years of age. The assessment consists of 36 words, which were selected utilizing developmentally expected vocabulary from the Brazilian Portuguese CDI and considering their consistency with phonological properties expected of children between 13–36 months that are monolingual speakers of Brazilian Portuguese. To administer PEEPS:BP, assessor(s) introduced toys representing each word in a structured, play-based manner to elicit labels from a child. If the child did not independently label the toy after the toy was introduced and/or as a response to the question (‘What is this?’), the assessor provided a model of the target word embedded within a phrase (e.g., ‘Look, I have a ___.’). If the child did not produce a label with those cues, the assessor provided a direct command (e.g., ‘Say ___.’). If the child did not produce a label following the command, the item was scored as ‘No Response.’ Each administration was video- and audio-recorded for transcription and reliability.

All PEEPS:BP administrations were independently transcribed by Brazilian SLPs with experience transcribing the speech of children with CL/P. The ASU project manager provided ongoing feedback and training on these transcriptions. Inter- and intra-judge transcription reliability was completed and disagreements were resolved through consensus. Phonetic transcription reliability was performed on 100% of the single word samples. The reliability was performed by the lead Brazilian clinician and a Portuguese speaking clinician on the U.S. team who were not interventionists for the study. Twenty percent of the transcripts contained disagreements that required consensus discussion and a third research clinician was used when consensus was not achieved. Most often these disagreements occurred when the child turned away from the camera and microphone and/or used atypical compensatory articulation errors. Final PEEPS:BP phonetic transcriptions were analyzed for number of words attempted; number of consonants attempted (overall and by manner); total consonant inventory by word position; PCC by manner: stops, fricatives, affricates, nasals, liquids, and total PCC; as well as percentage of nasal emissions, nasal substitutions, and compensatory errors. Additionally, hypernasality was rated by three Brazilian SLPs from spontaneous language samples. Inter-rater reliability was 95% agreement. The samples were rated at T1 and T2 (only because of limited speech production at T0) on a 0 to 3 equal-appearing interval scale (0 = absent, 1 = minimal hypernasality, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe).

The Intelligibility in Context Scale for Brazilian Portuguese (ICS; McLeod, 2020, McLeod et al., 2012) was administered to ascertain a measure of child’s speech intelligibility per caregiver report. The intelligibility assessment elicits an overall judgement of intelligibility based on the average response to seven questions on a five-point rating scale. This measure has been used for 4–5 year olds; however, there were no similar measures for younger children that could provide a social validity measure of intelligibility. There is evidence to support that this tool is reliable and valid when administered in other languages and countries (McLeod, 2020). For this study, the mothers of the children completed the ICS at all time points.

Language assessment and measures

Multiple language measures were administered to assess children’s receptive and expressive language development throughout the intervention, including standardized and non-standardized language assessments in Brazilian Portuguese.

The Avaliação do Desenvolvimento da Linguagem or Evaluation of Language Development (ADL; Menezes, 2004), ADL is a norm-referenced, clinical assessment designed to evaluate preschool language development through play. Six scores were obtained from ADL administration: raw and standard receptive language scores, raw and standard expressive language scores, and raw and standard total language scores.

In addition, language samples were collected at T0, T1, and T2 for each child. Language samples consisted of a play-based interaction between the child and clinician with a standard set of toys. Clinicians were blinded to study group. After approximately a 15-minute recording was established, two native-BP-speaking SLPs transcribed the interaction orthographically. The ASU project manager provided ongoing feedback and training on these transcriptions. A final consensus transcription was obtained with the Brazilian SLPs and the research assistants at ASU. Few language-specific adaptations to language sampling transcription were made for Brazilian Portuguese (see Supplementary Materials). Language samples were analyzed for four measures: number of different words (NDW), total words produced, total utterances, and mean length of utterance in words (MLU-w).

The CDI adapted for Brazilian Portuguese (Teixeira, 2000; Teixeira, 2019) was administered to assess children’s vocabulary size. The assessment consists of a vocabulary checklist, in which caregivers indicate whether a child understands or understands and says a given vocabulary item. The Brazilian Portuguese adaptation of this assessment was developed considering early-developing words in Brazilian Portuguese. The CDI provides a measure of Total Vocabulary Size. Further, this study considered the average length (in words) of the three longest utterances.

A complete dataset for the speech and language measures from the current study is available at DOI10.13140/RG.2.2.33345.38241.

EMT+PE intervention

Children in the intervention group received 30–45-minute sessions, twice weekly, for a total of 12 weeks. The intervention sessions consisted of clinician directed intervention with parent training on the components of the EMT+PE program presented during the sessions to be practiced at home.

All sessions were administered by two Brazilian speech-language pathologists (SLPs), one at each of the two sites. Both SLPs had been trained to criterion to ensure consistency of intervention delivery before therapy administration. Training for intervention purposes consisted of a three-phase process (see ‘Assessor/intervention training’).

Core strategies of EMT+PE were used to engage the child and facilitate target word use. Per Kaiser et al. (2017), all EMT+PE strategies were implemented naturalistically in routines and play across each session. There were nine component strategies of EMT+PE: 1) environmental arrangement, in which SLPs provide environmental boundaries, provide age-appropriate toys, and use materials that elicitation conversation and play; 2) mirroring and mapping, in which SLPs intentionally respond to children’s play-based interests and communication attempts; 3) responding and praising, in which SLPs praise all correct requests, responses, and behaviors; 4) emphasis in models, in which SLP models include and emphasize children’s speech targets; 5) emphasis in speech recasting, in which SLPs emphasize target speech sounds when recasting children’s speech errors; 6) requests, in which SLPs use choice questions to elicit child speech targets; 7) time delays, in which the SLPs pause when the child requests an item non-verbally or with minimal verbalization (to encourage a verbal attempt); 8) expansions, in which SLP expansions preserve as much of children’s original utterances as possible; 9) ‘proximal’ or meaningful verbal feedback, in which SLPs do not produce utterances that exceed the child’s average utterance length by more than two to three words nor do SLPs ask more than five Wh- questions in a given session.

EMT+PE implementation

Target word selection.

For participants in the EMT+PE group, target words were selected based upon an assessment of each individual child’s baseline performance in the CDI and PEEPS:BP. The target words comprised high pressure consonants, primarily stops, and nasals in consonant-vowel-consonant-vowel (CVCV) words. Target words were selected from the CDI vocabulary list containing stops and nasals in word positions identified in the speech assessment.

Procedural fidelity.

Procedural fidelity of the intervention was assessed at three time points during intervention: sessions 6, 12, and 18. Fidelity checklists were completed by the lead Brazilian research clinician (who was not an interventionist) and verified by a Portuguese-speaking clinician on the U.S. team. The fidelity rating maintained a criterion of 90% to assure that the fidelity was maintained throughout the intervention. The procedural fidelity 92–100% for each of the fidelity sessions. The fidelity form is included in Appendix A.

Business-as-usual comparison group

Children assigned to the business-as-usual (BAU) group were assessed at the same three time points as the children receiving EMT+PE intervention. None of the children in the BAU group received speech and language services, but all received follow-up services from the cleft lip/palate team.

Analysis

For each outcome, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model compared outcomes for intervention vs. BAU group at the target time point controlling for those outcomes measured at the previous time point. The T0-T1 analysis estimates the immediate posttreatment effect, while the T0-T2 analysis estimates the follow up treatment effects. Analysis of covariance is an efficient statistical technique that produces unbiased estimates of treatment effects when the treatment is randomly assigned, as it was in this case, and is more powerful than alternative strategies (Van Breukelen, 2006).

Results

Post-intervention effects

The results in Table 3 shows the comparison of pre- and immediately post-treatment effects between the EMT+PE and BAU conditions. The primary significant effects were in the language variables including parent ratings of vocabulary and average of three longest sentences, language sample variables (NDW, total utterances, and MLU-w) and receptive language performance (ADL) at p < 0.05 with moderate and large effect sizes. Percent Consonants Correct (PCC)-Stops and the standardized language test (ADL) total raw score approached significance and had large effect sizes. Additionally, several variables that did not show significant results had large effect sizes (d = 0.65–0.70). These included the ICS and ADL expressive language scores and total words produced from the language sample.

Table 3.

Post-Intervention Comparison Results for ANCOVA Models of Change for Speech and Language Variables

| Measure and Outcome | Est (Std Err) | p | d | F(2, 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PEEPS:BP | ||||

| Percent Consonants Correct (Total) | 0.06 (0.06) | 0.352 | 0.40 | 17.67 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Nasal) | −0.19 (0.12) | 0.132 | −0.44 | 2.31 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Stop) | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.060 | 0.72 | 20.76 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Fricative) | −0.01 (0.08) | 0.879 | −0.07 | 10.14 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Affricate) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.867 | 0.06 | 0.69 |

| Percent Compensatory Errors | 0.00 (0.03) | 0.931 | 0.03 | 4.01 |

| Number of Consonants (Initial) | 0.81 (1.14) | 0.485 | 0.27 | 12.09 |

| Number of Consonants (Medial or Final) | 0.86 (1.40) | 0.545 | 0.23 | 10.26 |

| CDI | ||||

| Vocabulary | 92.19 (33.38) | 0.012 | 1.18 | 29.29* |

| Average of Three Longest Utterances | 0.67 (0.28) | 0.026 | 0.55 | 6.48* |

| ICS Total | 2.39 (1.43) | 0.110 | 0.66 | 12.21 |

| ADL | ||||

| Raw Score for Receptive Language | 3.82(1.39) | 0.012 | 1.14 | 17.56* |

| Raw Score for Expressive language | 3.07 (1.96) | 0.132 | 0.66 | 11.33 |

| Raw Score (Total) | 27.68 (13.76) | 0.057 | 0.71 | 7.00 |

| Language Sample | ||||

| Number of Different Words | 24.77 (7.90) | 0.005 | 1.26 | 17.19* |

| Total Words Produced | 47.56 (23.34) | 0.054 | 0.85 | 17.00 |

| Total Utterances | 31.29 (12.02) | 0.017 | 1.03 | 13.28* |

| Mean Length of Utterance in Words | 0.50 (0.15) | 0.002 | 1.37 | 22.87* |

Note. PEEPS:BP = Profiles of Early Expressive Phonological Skills: Brazilian Portuguese, CDI = Communicative Development Inventory, ICS = Intelligibility in Context Scale, ADL = Evaluation of Language Development

p < .05.

Follow-up effects

The results for the comparison of pre-treatment and 3-month follow-up showed a significant difference in gains in both language and speech skills between the groups and are displayed in Table 4. Two language variables that showed significant gains in the post-intervention effects also continued to show these effects in the three-month follow up. These included the language sample variables of NDW and total utterances. Three speech variables achieved significance at the three-month follow up. These included total PCC, PCC-stops, and the ICS score. Several speech and language variables showed nonsignificant results but moderate effect sizes (d = 0.48–0.69). These variables included PCC-fricatives, nasals, number of initial word position consonants, CDI vocabulary, ADL expressive language, and total words produced and MLU-w on the language sample. Table 4 shows the statistical analyses and effect size estimates for the three-month follow up.

Table 4.

Follow-Up Results for ANCOVA Models of Change for Speech and Language Variables

| Measure and Outcome | Est (Std Err) | p | d | F(2, 21) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PEEPS:BP | ||||

| Percent Consonants Correct (Total) | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.011 | 1.17 | 35.07* |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Nasal) | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.119 | 0.53 | 5.53 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Stop) | 0.22 (0.07) | 0.006 | 1.16 | 27.21 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Fricative) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.116 | 0.70 | 17.65 |

| Percent Consonants Correct (Affricate) | −0.06 (0.14) | 0.685 | −0.14 | 2.06 |

| Percent Compensatory Errors | −0.02 (0.02) | 0.472 | −0.15 | 4.54 |

| Number of Consonants (Initial) | 1.44 (0.96) | 0.150 | 0.54 | 15.62 |

| Number of Consonants (Medial or Final) | 1.46 (1.30) | 0.274 | 0.36 | 6.21 |

| CDI | ||||

| Vocabulary | 92.22 (58.17) | 0.129 | 0.70 | 5.94 |

| Average of Three Longest Utterances | 0.43 (0.29) | 0.154 | 0.32 | 2.23 |

| ICS Total | 3.89 (1.70) | 0.032 | 0.93 | 10.82* |

| ADL | ||||

| Raw Score for Receptive Language | 2.32 (2.28) | 0.323 | 0.42 | 10.12 |

| Raw Score for Expressive language | 2.07 (1.85) | 0.277 | 0.48 | 15.71 |

| Raw Score (Total) | 14.24 (13.97) | 0.320 | 0.38 | 6.64 |

| Language Sample | ||||

| Number of Different Words | 42.756 (13.85) | 0.006 | 1.23 | 7.31* |

| Total Words Produced | 40.47 (27.12) | 0.151 | 0.62 | 16.26 |

| Total Utterances | 43.35 (14.84) | 0.008 | 1.11 | 8.68* |

| Mean Length of Utterance in Words | 0.26 (0.20) | 0.210 | 0.55 | 5.46 |

Note: Positive estimates and Cohen's d effect sizes indicate that the intervention group mean was higher than the BAU group mean at 3-month follow-up controlling for the pretest scores measured at pre-intervention. p-values unadjusted for multiple comparisons. PEEPS:BP = Profiles of Early Expressive Phonological Skills: Brazilian Portuguese, CDI = Communicative Development Inventory, ICS = Intelligibility in Context Scale, ADL = Evaluation of Language Development

p < .05.

Cleft-related speech errors

Speech errors of place of articulation that occur more prominently in young children with clefts are characterised by compensatory articulatory substitutions (e.g., glottal stops, pharyngeal fricatives), nasal substitutions (Harding & Grunwell, 1998; Chapman & Willadsen, 2011). These speech errors are present very early in development and can undergo changes in their use along with the child’s changing phonological system and with subsequent surgical and speech interventions (Klinto, Salamah, Olssson, Flynn, Svensson & Lohmander, 2014). Compensatory articulation and nasal substitutions were present for most of the children in both groups, although at least half of the children used few (i.e., three or fewer) errors. The children who used compensatory articulation and nasal substitution showed changes in their error use during the study, although the direction of change did not show a consistent trend in either group. Six children (four from the EMT+PE group) showed a decline in compensatory and nasal substitutions while the remaining seven (two from the EMT+PE group) maintained or increased their use of these active errors. To show examples from individual children, Table 5 shows the speech profiles across the three time points for four children selected from the intervention and BAU group. These profile comparisons serve to demonstrate the complex relationship between early speech and language development and the presence of compensatory articulation and nasal substitutions. This information has implications for assessment and treatment decisions that will be discussed later.

Table 5.

Speech and language profiles for four children showing differences in language and speech measures during the study.

| ID | A11 (EMT+PE) | A12(EMT+PE) | B05 (BAU) | B10 (BAU) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | T0 | T1 | T2 | |

| Age (Months) | 24 | 27 | 30 | 29 | 32 | 35 | 23 | 26 | 29 | 33 | 37 | 40 |

| Language Sample * | ||||||||||||

| NDW | 12 | 45 | 194 | 29 | 75 | 97 | 17 | 68 | 81 | 82 | 90 | 92 |

| TW | 31 | 128 | 230 | 55 | 165 | 192 | 36 | 119 | 196 | 191 | 350 | 319 |

| MLU | 1.17 | 2.33 | 2.61 | 1.25 | 1.82 | 2.2 | 1.24 | 1.29 | 1.77 | 2.08 | 2.89 | 2.31 |

| Speech ** | ||||||||||||

| Consonant Inventory | 8 | 11 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 7 | 15 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 17 |

| PCC Total | 6.5 | 31 | 41 | 17 | 37 | 41 | 45 | 61 | 62 | 21 | 49 | 36 |

| PCC Stops | 33 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 62 | 67 | 66 | 79 | 89 | 10 | 34 | 24 |

| Comp. Errors | 19 | 33 | 32 | 29 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 19 | 18 |

| Nasal Subs | 10 | 16 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

*Note NDW=Number of different words, TW=Total words, MLU=Mean length of utterance, Number of Nasal Subs=Nasal substitutions

30-Minute Language Sample

Speech measures were collected from single word production in the PEEP:BR.

Table 5 shows a profile of language and speech performance for four children (two from the EMT+PE group and two from the BAU group) to demonstrate the differential patterns of performance over the three timepoints in the study and their relationship to speech and language growth. All four children began the study with relatively limited speech and language performance (T0). Child A11 achieved substantial gains in both language and speech outcomes during the study. However, this child showed increasing use of compensatory and nasal substitutions during the study and child demonstrated moderate hypernasality as rated by the Brazilian SLPs at T2, in addition to their nasal substitutions and compensatory errors, indicating presence of VPD. Child A12 had a similar profile of speech and language performance on pre-treatment measures (as to Child A11) with relatively high compensatory articulation use at pre-treatment. In contrast to Child A11, Child A12 decreased their use of compensatory and nasal substitutions during the study and was not considered at risk for VPD. Child B05 also had a similar speech and language profile to A11 at pre-treatment, but did not use many compensatory and nasal substitutions, despite having a moderate hypernasality rating; this child was also considered at risk for VPD. Child B10 (who was one of the older children in the study) showed a significant speech delay per speech measures and presence of compensatory and nasal substitutions. This child reduced the use of nasal substitutions, but maintained production of compensatory errors throughout the study. This child had moderate hypernasality indicating the presence of VPD. Seemingly all four children with comparable pre-treatment speech and language profiles developed observationally different profiles in compensatory and nasal substitution usage over the course of the study. Monitoring of the speech errors over time did assist in team decision making for referrals for VPD.

Answering the research questions

Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate significant post intervention and follow up gains in the speech measures in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

The data indicates that the intervention group made significant speech gains in the 3 month follow up but less so immediately post-intervention. Post-intervention results showed no significant group differences for speech measures, although a large effect size for PCC-Stops (d = 0.72) was noted. However, there were significant findings for speech in the follow-up. Total PCC, PCC-stops (the target sound class for treatment), and intelligibility (ICS) measures all achieved statistical significance and support the positive gains over the comparison group. Additionally, PCC-fricatives and -nasals showed large effect size differences even though the gains did not reach significance indicating that the speech effects had a broader impact beyond the target speech sounds. The improvement in our intelligibility measure (ICS) occurred primarily in how well the child was understood by strangers relative to the comparison group. This particular item was found to be predictive of which children with CL/P had better speech intelligibility at age 8 years (Wren, Miller, Peters, Edmond & Roulestone, 2016). Additionally, overall scores on the ICS at follow up were similar for our BAU group (M=3.63) to those reported for a study of children clefts in the UK at 3 years of age (M=3.75). While our treatment group had a mean score above those comparison groups (M=4.45) (Seifert, Davies, Harding, McLeod & Wren, 2021). To our knowledge this study is the first to validate the ICS in Brazilian Portuguese as an outcome measure for intervention research.

-

1a.

Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate a significant reduction in compensatory and nasal substitutions in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

No significant differences were observed between groups on compensatory or nasal substitutions across time points. However, the small number of children in each group with these errors in this pilot study likely contributed to these findings. Descriptive analysis revealed that about half of the children in each group had no or minimal use of compensatory or nasal substitutions (six Intervention, five BAU). As shown in Table 5, the relationship between compensatory and nasal substitution use and VPD was not straightforward. The monitoring of these errors over time when the child was gaining sufficient expressive language production did inform decision-making for subsequent surgery and further speech intervention.

2. Do children with CL/P that receive EMT+PE intervention demonstrate significant post intervention and 3 month follow up gains in language measures in comparison to a business-as-usual group?

The language variables showed both significant differences between groups for immediate post-intervention and follow-up gains. The EMT+PE group showed a significant difference in receptive language and expressive vocabulary and sentence combinations in the post-intervention. EMT+PE strategies promote child engagement, model and expand vocabulary, and increase child word and sentence attempts; such supports give the child sufficient opportunities to practice speech production. The post-intervention language effects pre-empt later speech-sound changes observed in the study.

Discussion

Post-intervention effects

The post-intervention effects were in the language domain including receptive language (ADL), vocabulary (CDI, language sample different words), and number and complexity of utterances (CDI longest sentences, total utterances in language sample). These findings align with prior literature. A recent EMT+PE intervention study involving children with CL/P in the USA showed a similar developmental trend in language and speech outcomes (Scherer, Kaiser, et al., 2020; Philp, 2020). The younger children in the study showed improvements in vocabulary use while the older children who used more than seven words per minute showed significant speech gains. The authors concluded that a language foundation is necessary to employ the speech facilitation strategies at a sufficient rate to impact speech outcomes. The current study clearly showed the language gains during the intervention when parents were trained in the matched turns, modelling, and expansions which facilitated language development. This current study supports the language findings of other studies with English- and Spanish-speaking non-cleft children with language delays (Roberts & Kaiser, 2015; Peredo et al., 2018).

Three-month follow-up

The three-month follow-up showed both significant gains in language and speech measures for the intervention group. The language gains (NDW and total utterances per the language sample indicate that the children receiving intervention talked more and with greater vocabulary diversity. Speech accuracy (PCC total and PCC stops) also improved for the intervention group. These gains are likely attributable to the intervention as stop consonants were the focus of the speech intervention and embedded into the activities during the intervention.

Why did the speech effects not appear immediately post-intervention? During the intervention, the mothers were modeled speech facilitation strategies during the intervention and as their child produced more language, they were able to use the speech recast strategies during their interactions with their child. We hypothesize that, in part, the children had to achieve sufficient expressive language use for the parents to use the speech strategies. The more the children talk, the more opportunities they have to practice speech production and receive feedback from adults in their environment (Scherer et al., 2020).

Developmental and cleft-related speech errors

All the children in both groups used developmental speech errors that are observed in children in the early stages of phonological development. While both groups showed changes in their speech acquisition over time, the intervention group made significantly more progress in acquisition of speech accuracy than the comparison group. The intervention group made more speech gains than the comparison group and many of the gains added consonants and reduced developmental substitutions to improve overall speech accuracy. Compensatory and nasal substitutions were only used by approximately half of the children in both groups. The presence of these errors for children with CL/P is thought to indicate VPD, and for some children in the study their presence was associated with a subsequent referral to the team for VPD assessment. This information did assist the team in making databased recommendations regarding subsequent follow up for VPD. However, the relationship between the presence of compensatory and nasal substitutions and VPD in toddlers with clefts is not straightforward. In a recent study, Hardin-Jones et al. (2018) found that 76% of toddlers with CL/P used nasal substitutions in their early words, while only 38% of those children had associated VPD at 39 months of age. Ongoing monitoring of compensatory and nasal substitutions prior to age 3 years, particularly in the presence of stop consonant use in words, will assist in recommendation for VPD follow up.

Limitations of the study

This pilot study provided the first randomized study of early intervention effects for toddlers with cleft palate in Brazil. However, it needs to be replicated with a larger clinical trial to validate the results. Replication studies with a similar experimental design should be conducted to evaluate the treatment efficacy of EMT+PE with a larger cohort of children. Further, this study is limited by the lack of validation of assessments available in Brazilian Portuguese. These non-standardized assessments, while generally clinically acceptable, limit analyses of treatment effects among the current sample and limit possible future comparisons between children with CL/P and typically developing children. Further standardization of relevant speech and language assessments in Brazilian Portuguese are necessary, as well as the collection of normative data for same-aged, typically developing children on similar measures.

Related to typical Brazilian Portuguese speech patterns, there is a need within existing literature to explore the confluence of standard Brazilian Portuguese’s phonemic inventory on the reliability of transcriptions pertaining to compensatory articulation. For instance, Brazilian Portuguese features five nasalized vowels, and though this study does not directly analyze vowel production, there is the possibility that nasalized vowels and/or errors in nasalization may influence transcription. Similarly, Brazilian Portuguese features the uvular fricative /χ/ as part of its typical phonemic inventory, which is also conventionally considered a compensatory error for populations with CL/P. Regardless, one approach to maintain the reliability of cross-linguistic transcriptions of CL/P speech is to rely on the transcriptions of trained native speakers of the language. For instance, Yamashita et al. (2018) found that native speakers of Swedish rated the hypernasality of Swedish-speaking children with CL/P significantly differently from the ratings of non-native speakers. Further research would be necessary to extend these findings to the reliability of the transcription of compensatory errors. Regardless, recruiting trained native speakers as transcribers is recommended for cross-linguistic CL/P speech assessments (Cordero, 2008).

Clinical implications

This study extends the evidence of language and speech benefits from the EMT+PE intervention to other language contexts. EMT has been successfully applied to noncleft bilingual Spanish-speaking families and now to Brazilian Portuguese children with cleft palate. The simultaneous gains in both vocabulary and speech production provide evidence for clinical application with this population. This study has led to the development of resources for training Brazilian SLPs and parents on EMT+PE, including a website that provides instructions for getting started with the therapy and implementing the strategies as well as video examples of the strategies (http://projetointerkids.hrac.usp.br/). Proper training of SLPs is essential for this treatment method to work. The SLP must be able to implement the strategies reliably prior to training parents on the strategies. The resources generated in this study will be useful to Brazilian SLPs when training parents on EMT+PE as well as SLPs based in other countries providing services for Brazilian Portuguese-speaking clients.

Future directions

Future research should include collecting normative speech and vocabulary data in Brazilian Portuguese for children under age three to improve clinical comparison to noncleft children. Additional development of the PEEPS:BP is also needed in order to account for dialectal variation in Brazil (Scherer, Yamashita, et al., 2020). In this study, dialectal speech-sound variations were identified and participants were not penalized for these differences, but there are likely more variations that need to be accounted for and factored into calculations such as sound classes. These advancements would yield a more accurate assessment and a more appropriate intervention for cleft and non-cleft Brazilian Portuguese toddlers. Future research should also consider longer follow up at 6 or 12-months post-intervention and adaptation of other early interventions for the Brazilian culture and comparison of EMT+PE to these other early interventions.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

References

- Albustanji YM, Albustanji MM, Hegazi MM, & Amayreh MM (2014). Prevalence and types of articulation errors in Saudi Arabic-speaking children with repaired cleft lip and palate. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 78(10), 1707–1715. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA). (2018). Parameters for evaluation and treatment of patients with cleft lip/palate or other craniofacial differences. Chapel Hill, NC. Retrieved from 10.1177/1055665617739564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bessell A, Dip C, Sell D, Whiting P, Roulstone S, Albery L, Persson M, Verhoeven A, Burke M, & Ness AR (2013). Speech and language therapy interventions for children with cleft palate: A systematic review. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 50(1), e1–e17. 10.1597/11-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro MG, Lamônica DAC, de Vasconsellos Hage SR, & Maximino LP (2019). Child development skills and language in toddlers with cleft lip and palate. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 116, 18–21. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero KN (2008). Assessment of cleft palate articulation and resonance in familiar and unfamiliar languages: English, Spanish, and Hmong. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Minnesota; Minneapolis, Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KL (2004). Is presurgery and early postsurgery performance related to speech and language outcomes at 3 years of age in children with cleft palate? Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 18(4–5), 235–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman KL, & Willadsen E (2011). The development of speech in children with cleft palate. In Howard S and Lohmander A (Eds.), Cleft palate speech: Assessment and intervention, (pp. 23–40). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Frey J, Kaiser A, & Scherer NJ (2018). The influences of child intelligibility and rate on caregiver responses to toddlers with and without cleft palate. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 55(2), 276–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha S (2015). Effectiveness of a parent-implemented intervention program for children with cleft palate. Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 79(5), 707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Jones M, & Chapman KL (2011). Cognitive and language issues associated with cleft lip and palate. Seminars in Speech and Language, 32(2), 127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Jones M & Chapman KL (2014). Early lexical characteristics in toddlers with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 51(6), 622–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Jones M & Chapman K (2018). The implications of nasal substitutions in the early phonology of toddlers with repaired cleft palate. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 55(9), 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Jones M, Chapman KL, Scherer NJ (2006). Early intervention for children with cleft palate. ASHA Leader, 11, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Harding A, & Grunwell P (1998). Active versus passive cleft-type speech characteristics. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 33(3), 329–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutters B & Brondsted K (1987). Strategies in cleft palate speech-with special reference to Danish. Cleft Palate Journal, 24(2), 126–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M (1988). Etiology of facial clefts: Prospective evaluation of 428 patients. Cleft Palate Journal, 25(1), 16–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Chapman K, & Hardin-Jones M (2003). Speech development of children with cleft palate before and after palate surgery. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 40(1), 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser AP, Scherer NJ, Frey JR, & Roberts MY (2017). The effects of enhanced milieu teaching with phonological emphasis on the speech and language skills of young children with cleft palate: A pilot study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26(3), 806–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinto K, Salameh E, Olsson M, Flynn T, Svensson H, & Lohmander A (2014). Phonology in Swedish-speaking three-year-olds born with cleft lip and palate and the relationship with consonant production at 18 months. International Journal of Language and Communicative Disorders, 49(2), 240–254. 10.1111/1460-6984.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamônica DAC, da Silva-Mori MJF, da Costa Ribeiro C, & Maximino LP (2016). Receptive and expressive language performance in children with and without cleft lip and palate. Communication Disorders, Audiology and Swallowing, 28(4), 369–372. 10.1590/2317-1782/20162015198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster HS, Lien KM, Chow JC, Frey JR, Scherer NJ, & Kaiser AP (2020). Early speech and language development in children with nonsyndromic cleft lip and/or palate: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(1), 14–31. 10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelino FC (2009) Perfil das habilidades de linguagem de indivíduos com fissura labiopalatina. [Unpublished PhD Dissertation]. Hospital de Reabilitação de Anomalias Craniofaciais, Universidade de São Paulo, Bauru, 2009. See http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/61/61132/tde-11122009-092121/pt-br.php. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S (2020). Intelligibility in Context Scale: Crosslinguistic use, validity, and reliability. Speech, Language and Hearing, 23(1), 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S, Harrison LJ, & McCormack J (2012). Intelligibility in Context Scale. Bathurst, NSW, Australia: Charles Sturt University. http://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech/ics [Google Scholar]

- Menezes MLN (2004). ADL: Avaliação do Desenvolvimento da Linguagem. São Paulo, SP: Pró-Fono. [Google Scholar]

- Pamplona C, Ysunza A, & Rameriz P (2004). Naturalistic intervention in children with cleft palate. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 68(1), 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peredo TN, Zelaya MI, & Kaiser AP (2018). Teaching low-income Spanish-speaking caregivers to implement EMT en Español with their young children with language impairment: A pilot study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(1), 136–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Falzone SJ, Trost-Cardamone JE, Karnell MP, & Hardin-Jones M (2017). A Clinician’s Guide to Treating Cleft Palate Speech, St. Louis: Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Philp J (2020). Enhanced Milieu Teaching with phonological emphasis (EMT+PE): A pilot telepractice parent training study. [Master’s thesis, Arizona State University]. ASU Digital Repository. [Google Scholar]

- Projeto Interkids. (n.d.). Intervenção precoce na fala de crianças com fissura labiopalatina. Retrieved July 31 from http://projetointerkids.hrac.usp.br

- Roberts MY, & Kaiser AP (2015). Early intervention for toddlers with language delays: A randomized control trial. Pediatrics, 135(4), 686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, D’Antonio LL, & Kalbfleisch JH (1999). Early speech and language development in children with velocardiofacial syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 88(6), 714–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, D’Antonio LL, & McGahey H (2008). Early intervention for children with cleft palate. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 45, 18–31. 10.1597/06-085.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, Boyce S, & Martin G (2013). Pre-linguistic children with cleft palate: Growth of gesture, vocalization, and word use. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(6), 586–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, Kaiser AP, Frey JR, Lancaster HS, Lien K, & Roberts MY (2020). Effects of a naturalistic intervention on the speech outcomes of young children with cleft palate. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 10.1080/17549507.2019.1702719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, Kaiser A, & Frey J, (2020). Enhanced Milieu Teaching/Phonological Emphasis: Application for Children with Cleft Lip and Palate. In Williams L and McCauley R (Eds) Speech Sound Disorders in Children, Second Edition, Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer NJ, Yamashita R, Fukushiro A, Oliveira D Keske-Soares M, Ingram D, Williams L, & Trindade. (2020). Assessment of early phonological development in children with clefts in Brazilian Portuguese. In Babatsouli E (Ed), Under-Reported Monolingual Child Phonology, (pp. 400–421). Multilingual Matters, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert M, Davies A, Harding S, McLeod S & Wren Y (2021). Intelligibility in 3-year-olds with cleft lip and/or palate using the intelligibility in context scale:Findings from the Cleft Collective Cohort Study, Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, DOI.org: 10.1177/1055665620985747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C, & Williams AL (2013). Early phonological development: Creating an assessment test. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 27(4), 278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh K (2011). An overview of randomization techniques: An unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. Journal of human reproductive sciences, 4(1), 8–11. 10.4103/0974-1208.82352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Teixeira ER (2000). A adaptação dos Inventários MacArthur de Desenvolvimento Comunicativo (CDI’s) para o português brasileiro. In: Anais do II Congresso Nacional da ABRALIN. Taciro – Produção de CDs Multimídia, 479–487. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira ER (2019). Communicative Development Inventory: Brazilian Portuguese. See mb-cdi.stanford.edu/adaptations.html

- Van Breukelen GJP (2006). ANCOVA versus change from baseline had more power in randomized studies and more bias in nonrandomized studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 59(9), 920–925. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihman M (1994). When is a word a word? Journal of Child Language, 21(3), 517–542. 10.1017/S0305000900009442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir CJ, & Lees KR (2003). Enhanced Milieu Teaching/Phonological Emphasis: Application for Children with Cleft Lip and Palate. Statistical Medicine, 15;22(5), 705–726, doi: 10.1002/sim.1366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willadsen E, Lohmander A, Persson C, Lundeborg I, Alalauusua S, Aukner R, Bau A, Bowden M, Davies J, Emborg B, Havstam C, Hayden C, Henningsson G, Holmefjord A, Hölttä E, Kisling-Møller M, Kjøll L, Lundberg M, McAleer E, … Semb G (2017). Scandcleft randomised trials of primary surgery for unilateral cleft lip and palate: 5. Speech outcomes in 5-year-olds-consonant proficiency and errors. Journal of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, 51(1), 38–51. 10.1080/2000656x.2016.1254647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wren Y Miller LL, Peters TJ, Edmond A & Roulestone S (2016). Prevalence and predictors of persistent speech sound disorder at eight years Olds: Findings from a population cohort study, Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research, 59;4, 647–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). International collaborative research on craniofacial anomalies. Retrieved from www.who.int/genomics/anomalies/en/

- Yamashita R, Borg E, Granqvist S, & Lohmander A (2018). Reliability of hypernasality rating: Comparison of 3 different methods for perceptual assessment. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 55(8), 1060–1071. 10.1177/1055665618767116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac DJ & Valino LD (2017). Evaluation and Management of Cleft Lip and Palate, San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.