Abstract

Background

Plastome (Plastid genome) sequences provide valuable markers for surveying evolutionary relationships and population genetics of plant species. Papilionoideae (papilionoids) has different nucleotide and structural variations in plastomes, which makes it an ideal model for genome evolution studies. Therefore, by sequencing the complete chloroplast genome of Onobrychis gaubae in this study, the characteristics and evolutionary patterns of plastome variations in IR-loss clade were compared.

Results

In the present study, the complete plastid genome of O. gaubae, endemic to Iran, was sequenced using Illumina paired-end sequencing and was compared with previously known genomes of the IRLC species of legumes. The O. gaubae plastid genome was 122,688 bp in length and included a large single-copy (LSC) region of 81,486 bp, a small single-copy (SSC) region of 13,805 bp and one copy of the inverted repeat (IRb) of 29,100 bp. The genome encoded 110 genes, including 76 protein-coding genes, 30 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes and four ribosome RNA (rRNA) genes and possessed 83 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) and 50 repeated structures with the highest proportion in the LSC. Comparative analysis of the chloroplast genomes across IRLC revealed three hotspot genes (ycf1, ycf2, clpP) which could be used as DNA barcode regions. Moreover, seven hypervariable regions [trnL(UAA)-trnT(UGU), trnT(GGU)-trnE(UUC), ycf1, ycf2, ycf4, accD and clpP] were identified within Onobrychis, which could be used to distinguish the Onobrychis species. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that O. gaubae is closely related to Hedysarum. The complete O. gaubae genome is a valuable resource for investigating evolution of Onobrychis species and can be used to identify related species.

Conclusions

Our results reveal that the plastomes of the IRLC are dynamic molecules and show multiple gene losses and inversions. The identified hypervariable regions could be used as molecular markers for resolving phylogenetic relationships and species identification and also provide new insights into plastome evolution across IRLC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-022-03465-4.

Keywords: Hypervariable region, IRLC, Onobrychis, Phylogenetic relationship, Plastome

Background

Chloroplast is a vital organelle in plant cells that plays an important role in plant carbon fixation and numerous metabolic pathways [1, 2]. In angiosperms, the chloroplast genome (plastome) typically has a circular structure that ranges from 120 to 180 kb in length. Plastomes mostly exhibit a quadripartite structure in which a pair of inverted repeats (IRa and IRb; usually around 25 kb, but can vary from 7 to 88 kb each) separate the large single-copy (LSC, ca. 80 kb) and the small single-copy (SSC, ca. 20 kb) regions [1, 2]. Most plastomes encode 80 protein-coding genes primarily involved in photosynthesis and other biochemical processes along with 30 tRNA and 4 rRNA genes [3, 4]. In contrast to mitochondrial and nuclear genomes, the plastomes across seed plants are highly conserved with respect to gene content, structure and organization [5, 6]. However, mutations including duplications, rearrangements, and losses have been reported at the genome and gene levels among some angiosperm lineages, including Asteraceae [7], Campanulaceae [8], Onagraceae [9], Fabaceae [10] and Geraniaceae [11].

Fabaceae (legumes) is the third-largest family of angiosperms which shows much extensive structural variation in the plastid genome [12]. Currently accepted classification of the legumes based on plastid gene matK includes six subfamilies: Caesalpinioideae, Cercidoideae, Detarioideae, Dialioideae, Duparquetioideae, and Papilionoideae [13]. Gene content and gene order among plastomes of subfamilies are highly conserved and similar to the ancestral angiosperm genome organization except for Papilionoideae, which exhibits numerous rearrangements and gene/intron losses and has smaller genomes [5]. In this subfamily, a loss of one of the IRs [14], the presence of many repetitive sequences [15] and the presence of a localized hypermutable region [15, 16] have been documented. The Papilionoideae is further divided into seven major clades [the Cladrastis, Genistoids, Dalbergioids, Mirbelioids, Millettioids, Robinioids and the inverted-repeat lacking clade (IRLC)] and several tribes [14]. IRLC is the largest legume lineage which contains over 4000 species in 52 genera and nine tribes [14, 17–20]. Species within the IRLC reveal multiple gene/intron losses [15, 21], several sequence inversions [10], gene transfer to the nucleus [15, 22] and localized hypermutation [15, 16]. The presence of genomic rearrangements along with nucleotide and structural variations in the IRLC plastomes have made it an excellent plant model for genome evolution studies.

Recently, with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology, plastomes of several taxa from different tribes in this clade have been sequenced. The majority of IRLC plastomes sequenced to date were restricted to agricultural/medicinal species (from the tribes Fabeae, Trifolieae, Caraganeae and Galegeae) or the plant model Medicago truncatula [23]. Thus, it is essential to investigate the members from other lineages to better understand plastome evolution within the IRLC, and more broadly within Papilionoideae. The plastid genome of the tribe Hedysareae has not been considered in previous studies. Members of Hedysareae are commonly restricted to Eurasia, N America, and the Horn of Africa with Socotra and are widely used as forage plants due to their high protein content [24–26]. In the tribe Hedysareae [24] with nine genera, the plastomes of some Hedysarum species and only one species of Onobrychis (O. viciifolia within subgenus Onobrychis) have been reported. Onobrychis is the second largest genus after Hedysarum in the tribe Hedysareae. Onobrychis is composed of two subgenera [Onobrychis and Sisyrosema (Bunge ex Boiss.) Sirj.] and has more than 130 species [25]. This genus mainly distributed throughout temperate and subtropical regions of Eurasia, N and NE Africa [26]. In the present study, the complete plastome of Onobrychis gaubae Bornm. was sequenced (GenBank accession number: LC647182). O. gaubae belongs to the subgenus Sisyrosema and is a polymorphic species restricted to the southern slopes of the Alborz mountain range, Iran [25, 27]. The main goal of this study is to assemble the chloroplast genome of O. gaubae, and to annotate the genome and characterize its structure to provide a new genomic resource for this species. We also performed comparative analyses of the genome and phylogenetic reconstruction to evaluate the sequence divergence in the plastomes across the IR-lacking clade.

Results

Characteristics of the chloroplast genome of O. gaubae

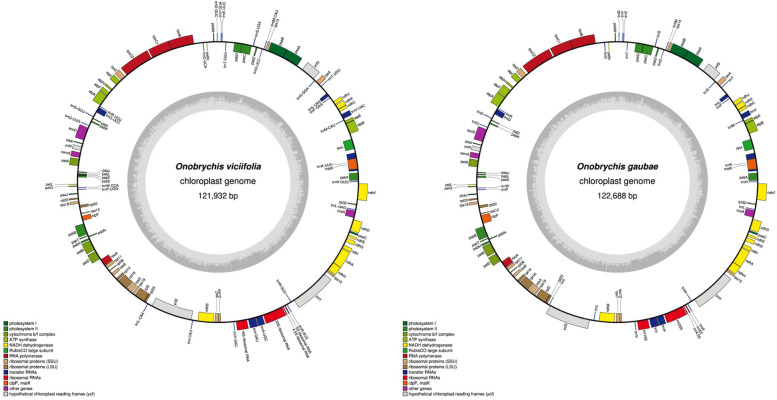

The number of paired-end raw reads obtained by the Illumina HiSeq 2000 system is 43,189,861 for O. gaubae sample. The plastid genome of O. gaubae with 122,688 bp in length and having only one copy of the IR region is similar to those of other IRLC species. In this context, the lack of rps16 and rpl22 genes and intron 1 of clpP in the plastome of O. gaubae are noted; these genes, are absent from the chloroplast genomes of entire IRLC[21, 22, 28]. The assembled chloroplast genome of O. gaubae contained 110 genes, including 76 protein-coding genes, 30 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes and four ribosome RNA (rRNA) genes (Fig. 1, Table 1). The LSC (79,783 bp), SSC (13,805 bp) and IR (29,100 bp) regions along with the locations of 110 genes in the chloroplast genome are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Gene map of two Onobrychis species chloroplast genome [O. viciifolia (MW007721) [29] and O. gaubae (LC647182)]. The genes drawn outside and inside of the circle are transcribed in clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. Genes were colored based on their functional groups. The inner circle shows the structure of the chloroplast: The large single copy (LSC), small single copy (SSC) and inverted repeat (IR) regions. The gray ring marks the GC content with the inner circle marking a 50% threshold. Asterisks mark genes that have introns

Table 1.

Genes predicted in the chloroplast genome of O. gaubae

| Category of genes | Group of genes | Name of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | Large subunit of ribosomal proteins | rpl14, rpl16*, rpl2*, rpl20, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Small subunit of ribosomal proteins | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12*, rps14, rps15, rps18, rps19 | |

| DNA-dependent RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 | |

| Ribosomal RNA genes | rrn16S, rrn23S, rrn 4.5S, rrn 5S | |

| Transfer RNA genes | 30 trn genes (5 contain an intron) | |

| Genes for photosynthesis | Subunits of NADH-dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB*, ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK |

| Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ | |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | |

| Subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| Other genes | Maturase K | matK |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Subunit of Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase | accD | |

| C-type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| Protease | clpP* | |

| Genes of unkown function | Conserved hypothetical chloroplast open reading frames | ycf1, ycf2, ycf4, ycf3** |

The number of asterisks after the gene names indicates the number of introns contained in the genes

A total of 16 genes (each separately) in O. gaubae chloroplast genome have only one intron, whereas ycf3 exhibits two introns (Additional File 1: Table S1). rps12 gene is a trans-splicing gene which does not have introns in the 3’-end. The trnK-UUU has the largest intron encompassing the matK gene, with 2,495 bp, whereas the intron of trnL-UAA is the smallest intron (542 bp). The O. viciifolia plastome with 121,932 bp in length is very similar in gene contents, order and orientation to O. gaubae. The chloroplast genome of O. viciifolia has two major structural differences from O. gaubae: lack of the atpF intron and inversion of ycf2/trnI(CAU)/trnL(CAA) genes.

The length of plastome in the IRLC taxa in this study ranged from 121,020 to 130,561 bp. All plastomes exhibited the typical structure of IR-loss clade composed of LSC region (79,916 to 87,193), SSC region (13,383 to 14,187) and only one inverted repeat region (27,604 to 30,487) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chloroplast genome information from sampled IRLC species and the newly assembled O. gaubae

| Species | Size (bp) | LSC (bp) | GC (%) (LSC) |

SSC (bp) | GC (%) (SSC) |

IR (bp) | GC (%) (IR) |

GC (%) Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astragalus mongholicus | 123,582 | 80,986 | 33.4% | 13,773 | 29.9% | 28,823 | 38.1% | 34.1% |

| Caragana microphylla | 130,029 | 85,436 | 33.3% | 14,106 | 30.4% | 30,487 | 38.8% | 34.3% |

| Carmichaelia australis | 122,805 | 80,588 | 33.5% | 14,074 | 30.2% | 28,143 | 38.6% | 34.3% |

| Cicer arietinum | 125,319 | 82,583 | 33% | 13,820 | 29.9% | 28,916 | 38.3% | 33.9% |

| Galega officinalis | 125,086 | 82,915 | 33.2% | 13,347 | 30.5% | 28,824 | 38.7% | 34.2% |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | 127,943 | 84,714 | 33.1% | 14,187 | 30.1% | 29,042 | 39.6% | 34.2% |

| Hedysarum semenovii | 123,407 | 80,288 | 34.1% | 13,679 | 30.5% | 29,440 | 38.9% | 34.9% |

| Lens culinaris | 122,967 | 81,659 | 33.7% | 13,833 | 30.2% | 27,604 | 38.7% | 34.4% |

| Lessertia frutescens | 122,700 | 80,698 | 33.4% | 13,750 | 29.9% | 28,252 | 38.4% | 34.2% |

| Medicago sativa | 125,330 | 83,756 | 32.9% | 13,383 | 30.2% | 28,191 | 38.6% | 34% |

| Melilotus albus | 127,205 | 84,279 | 32.7% | 13,806 | 29.8% | 29,120 | 38.1% | 33.6% |

| Meristotropis xanthioides | 127,735 | 84,629 | 33.1% | 14,150 | 30.1% | 28,956 | 39.6% | 34.2% |

| Onobrychis gaubae | 122,688 | 79,783 | 33.8% | 13,805 | 30.5% | 29,100 | 38.8% | 34.6% |

| Onobrychis viciifolia | 121,932 | 78,986 | 33.8% | 13,821 | 30.4% | 29,125 | 38.8% | 34.6% |

| Oxytropis bicolor | 122,461 | 80,170 | 33.5% | 14,017 | 30% | 28,274 | 38.3% | 34.2% |

| Tibetia liangshanensis | 123,372 | 79,916 | 33.9% | 13,513 | 30.6% | 29,943 | 38.6% | 34.7% |

| Wisteria floribunda | 130,561 | 87,193 | 33.2% | 14,127 | 30% | 29,628 | 39.4% | 34.4% |

LSC Large Single Copy, SSC Small Single Copy, IR Inverted Repeat

Gene order and gene/intron content in plastomes of all the IRLC taxa are highly conserved. The overall GC content of the O. gaubae chloroplast genome sequence was 34.6%, which is consistent with other IRLC species, whose plastomes have GC-contents ranging from 33.6% to 35.1% (Table 2). Different GC content occurs in the LSC (32.7%—34.1%), SSC (29.8%—30.6%) and IR (38.1%—39.6%) regions (Table 2).

Sequencing, assembly and annotation confirm that the complete plastome of O. gaubae lacks the IRa region. Lack of this region is confirmed by PCR and Sanger sequencing for O. gaubae. PCR amplification is expected from the primers located in the ndhF-psbA region (IR/SSC boundary) and rps19-rpl2 region (LSC/IR boundary) for the species without IRa copy. In the present study, Sanger sequenced PCR amplicons agree with the absence of IRa copy in the plastid genome of O. gaubae.

Codon usage bias

The total coding DNA sequences (CDSs) were 81,121 bp in length and encoded 75 genes including 24,765 codons which belonged to 61 codon types. Codon usage was calculated for the protein-coding genes present in the O. gaubae cp genome. Phenylalanine was the most abundant amino acid, whereas Alanine showed the least abundance in this species (Additional File 1: Table S2). Most protein-coding genes employ the standard ATG as the initiator codon. Among the O. gaubae protein-coding genes, three genes used alternative start codons; ACG for psbL and ndhD, and GTG for rps8. A similar codon usage pattern was exhibited in O. viciifolia (Additional File 1: Table S3).

The chloroplast genomes of the IRLC were analyzed for their codon usage frequency according to sequences of protein-coding genes and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU). RSCU is an important indicator to measure codon usage bias in coding regions. This value is the ratio between the actual observed values of the codon and the theoretical expectations. A codon with an RSCU value higher than 1.0 has a positive codon usage bias, while a value lower than 1.0 has a negative codon usage bias. When the RSCU value is equal to 1.0 it means that this codon is chosen equally and had no bias [30, 31]. The total number of codons among protein-coding genes in the IRLC species varies from 20,381 in Hedysarum taipeicum (as the smallest number) to 24,765 in O. gaubae. The most often used synonymous codon was AUU, encoding isoleucine, and the least used was CGC/CGG, encoding arginine (Additional File 2: Table S4). In the IRLC, the standard AUG codon was usually the start codon for the majority of protein-coding genes and UAA was the most frequent stop codon among three stop codons. Methionine (AUG) and tryptophan (UGG) showed RSCU = 1, indicating no codon bias for these two amino acids. The highest RSCU value was for UUA (~ 2.04) in leucine and the lowest was GGC (~ 0.35) in glycine. Leucine preferred six codon types (UUA, UUG, CUU, CUC, CUA, and CUG) and actually showed A or T (U) bias in all synonymous codons (Additional File 2: Table S4). The result of distributions of codon usage in the IRLC species showed that RSCU > 1 was recorded for most codons that ended with an A or a U, except for UUG codon, resulting in the bias for A/T bases. As well as, more codons with the RSCU value less than one, ended with base C or G. So, there is high A/U preference in the third codon of the IR-loss clade coding regions, which is a common phenomenon in cp genomes of vascular plants [32].

Analysis of repeats

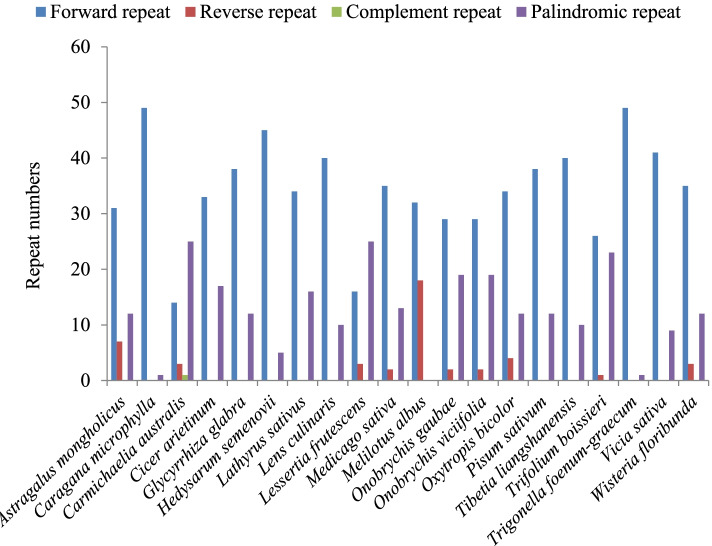

Repeat analysis of O. gaubae plastome identified 50 repeat structures with lengths ranging from 30 to 179 bp. These structures included 29 forward repeats with lengths in the range of 30–179 bp, 19 palindromic repeats of 30–81 bp and two reverse repeats with a length of 31 and 37 bp (Additional File 3: Table S5). Among the 50 repeats, 66% are located in the LSC region, 18% in the IR region and 16% in the SSC region. Also, most of the repeats (42%) were found in coding regions (accD, psaA, psaB, psbC, psbJ, ycf1, ycf2, ycf4, rps12, trnR-UCU, trnK-UUU), 40% were distributed in the intergenic spacer regions (IGS) and 18% were located in the introns (ndhA, rpl16, rps12, petB, ycf3). The pattern of repeat structures (both in frequency and location) in O. gaubae is similar to that of O. viciifolia (Additional File 3: Table S6). In the majority of the studied IRLC species, the most frequently observed repeats were forward, then palindromic, and the least reverse (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of repeated sequences in the IRLC species chloroplast genomes

In the IRLC species, the most abundant dispersed repeats identified were forward with lengths ranging from 30 to 50 bp. The longest repeats were also of the forward type, with the length of 560 bp were detected in the Hedysarum taipeicum, followed by Vicia sativa of 517 bp and Caragana microphylla of 455 bp, which were much longer than other species studied.

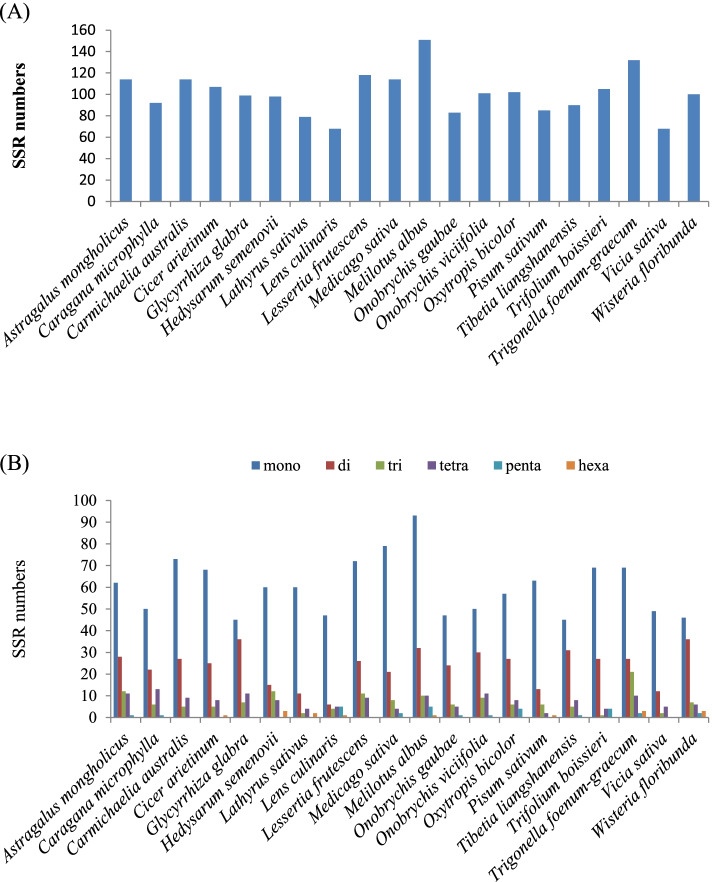

Simple sequence repeats (SSRs), or microsatellites, are a type of tandem repeat sequences that contain 1–6 nucleotide repeat units and have wide distribution throughout the genome [31, 33]. Accordingly, microsatellites play a crucial role in the genome recombination and rearrangement. These nucleotide motifs show a high level of polymorphism that can be widely used for phylogenetic analysis, population genetics and species authentication [31, 34–36]. A total of 83 SSRs were detected in the O. gaubae plastome, which were composed by a length of at least 10 bp. Among them, 47 (56.62%) were mono-repeats, 24 (28.91%) were di-repeats, 6 (7.22%) were tri-repeats, five (6.02%) were tetra-repeats and one were penta-repeats (1.2%). No hexanucleotide SSRs was found in O. gaubae genome (Additional File 3: Table S7). Onobrychis viciifolia with 101 SSRs including 50 mono-repeats (49.5%), 30 (29.7%) di-repeats, nine (8.91%) tri-repeats, 11 (10.89%) tetra-repeats and one penta-repeat (0.99%), exhibited similar SSR distribution pattern in the plastome (Additional File 3: Table S8). The number of SSRs in the IRLC cp genomes (cpSSRs) ranged from 68 (Vicia sativa and Lens culinaris) to 151 (Melilotus albus) across the IRLC species (Fig. 3A). The mononucleotide repeats (P1) were identified at a much higher frequency, which varied from 45 (Tibetia liangshanensis, Glycyrrhiza glabra) to 93 (Melilotus albus) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of perfect simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the IRLC chloroplast genomes. A The number of SSRs detected in the IRLC chloroplast genomes; (B) The number of SSR types detected in the IRLC chloroplast genomes

In the mononucleotide repeats, A/T motifs were the most abundant but no G/C motif was detected in the cp genome. Likewise, the majority of the dinucleotides and trinucleotides were found to be particularly rich in AT sequences.

Sequence divergence analysis

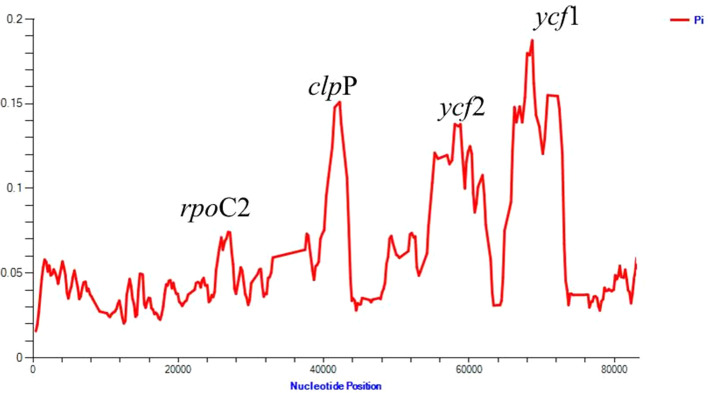

The average nucleotide diversity (Pi) among the protein-coding genes of 23 species of the IRLC was estimated to be 0.05736. Furthermore, comparison of nucleotide diversity in the LSC, SSC and IR regions indicated that the IR region exhibits the highest nucleotide diversity (0.11549) and the SSC region shows the least (0.04132). We detected three hyper-variable regions with Pi values > 0.1 among the IRLC species; ycf1 and ycf2 from IR region and clpP from LSC region (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide variability (%) values among the IRLC species (using for coding regions). Window length: 800 bp; step size: 200 bp. X-axis: Position of the midpoint of a window. Y-axis: Nucleotide diversity of each window

Among these, ycf1 encoding a protein of 1800 amino acids has the highest nucleotide diversity (0.18745). The average nucleotide diversity was also investigated between two Onobrychis plastid genome sequences. The average value of Pi between the Onobrychis species was estimated to be 0.05632 (Additional File 4: Fig. S1). High nucleotide variations were observed for the protein-coding regions ycf1, ycf2, clpP, accD and ycf4 and intergenic regions such as trnL(UAA)-trnT(UGU) and trnT(GGU)-trnE(UUC). Sliding window analysis results revealed the same variable regions in the cp genome of the two Onobrychis species.

Moreover, mVISTA was used to compare whole chloroplast genome sequences of the IRLC species. We found that, similar to other plant species, the gene coding regions were more conserved than the noncoding regions (Additional File 5: Fig. S2). High nucleotide variations were observed across the IRLC for the protein-coding regions ycf1, ycf2 and clpP. Similar results were also obtained from the calculation of nucleotide diversity (Pi).

Selection pressure analysis

In this study, the non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) rate ratio (Ka/Ks) was estimated for 75 protein-coding genes across the 28 IRLC species by using DnaSP v.6.12 [37] (Additional File 6: Table S9). In general, the Ka/Ks values were lower than 0.5 for almost all genes. The ycf4 gene which is involved in regulating the assembly of the photosystem I complex had the highest nonsynonymous rate, 0.165691, while the ycf1 gene with unknown functions had the highest synonymous rate, 0.181067. The Ka/Ks ratio (denoted as ω) is widely used as an estimator of selective pressure for protein-coding genes. ω > 1 indicates that the gene is affected by positive selection, ω < 1 indicates purifying (negative) selection, and ω equal to 1 indicates neutral mutation [38]. In the present study, the Ka/Ks ratio was calculated to be 0 for psbL gene which encodes one of the subunits of photosystem II. The Ka/Ks ratio indicates purifying selection in 73 protein-coding genes. The highest Ka/Ks ratio which indicates positive selection was observed in accD gene which encodes a subunit of the acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) enzyme.

Prediction of RNA editing sites

RNA editing as a post-transcriptional modification process, mainly occurs in chloroplasts and mitochondrial genomes. In higher plants, some chloroplast RNA editing sites which provide a way to create transcript and protein diversity are conserved [31].

RNA editing sites of O. gaubae plastid genes were predicted using Prep-CP prediction tool (Additional File 7: Table S10). In total, 58 editing sites were present in 19 chloroplast protein-coding genes and all of the editing sites were C-to-U conversions (Additional File 7: Table S10). Among them, nine editing sites, the highest number, were found in the region encoding ndhB gene followed by seven editing sites in petB. There were six editing sites detected each in ndhA and rpoB genes. accD, ndhG and petD had three editing sites, and ndhD and ndhF had two editing sites. Two editing sites were also found in ccsA, matK and rpoC1 genes. The remaining seven genes had only one editing site. The results showed that ndh genes exhibited the most abundant editing sites which were nearly 39.6% of the total editing sites. Furthermore, we predicted 65 RNA editing sites out of 22 plastid genes in chloroplast genomes of O. viciifolia. In this species, the highest number of editing sites belongs to the petB, rpoC1 and ndhB genes with 9, 8 and 7 sites, respectively (Additional File 7: Table S11).

Phylogenetic analysis

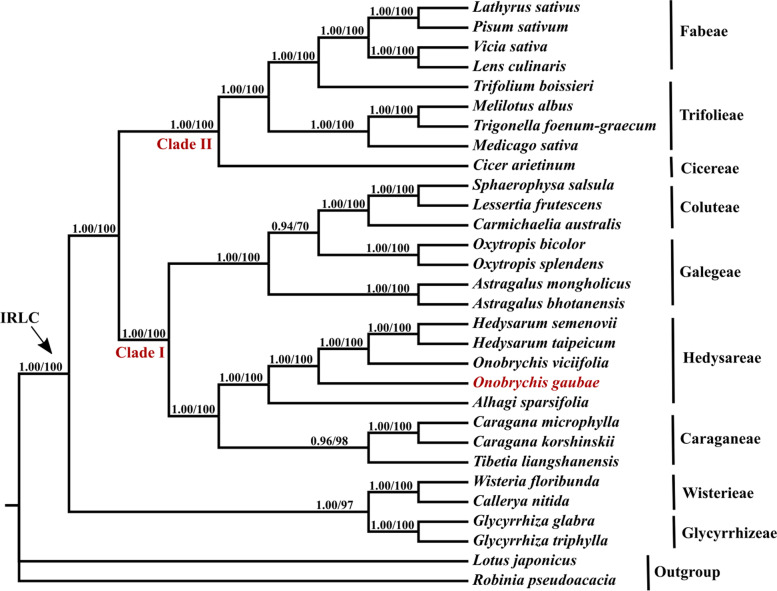

Phylogenetic relationships within the IRLC were reconstructed using the representative taxa (28 species from different tribes) and two species as outgroups based on 75 protein-coding genes of their chloroplast genomes. The total concatenated alignment length from the 75 protein-coding genes was 87,455 bp. The maximum likelihood (ML) analysis resulted in a well-resolved tree and the Bayesian inference yielded a well-resolved topology with high support values (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fifty percent majority rule consensus tree resulting from Bayesian analysis of the 75 plastid genes of IRLC. The position of Onobrychis gaubae is shown in red. Numbers above branches are posterior probability and likelihood values, respectively

The ML and Bayesian trees were largely congruent. The tribe Wisterieae [19] together with tribe Glycyrrhizeae [20], which formed a well-supported clade, were sister to the rest of the IRLC.

Following the basal group, the IRLC divided into two clades: clade I and II (Fig. 5). Clade I comprises tribes Caraganeae [17], Hedysareae [24] and Coluteae [18] as well as genera Oxytropis and Astragalus. Our results confirmed a close relationship among O. gaubae, O. viciifolia and Hedysarum species and showed O. gaubae phylogenetic position in the tribe Hedysareae. Furthermore, our plastid DNA analyses represent that Oxytropis is sister to the tribe Coluteae. Clade II contains tribes Cicereae, Trifolieae and Fabeae.

Discussion

General features of the Onobrychis gaubae plastid genome

In our study, we determined the first complete chloroplast genome sequence of O. gaubae within O. subgenus Sisyrosema using the Illumina platform and deposited in the GenBank (Fig. 1). Our assembly and annotation results showed that the length of the cp genome is 122,688 bp and its structure is similar to those of other IRLC species. Plastomes of O. gaubae and O. viciifolia are highly conserved and are similar with respect to genome organization and gene content. In this regard, one of the structural changes detected in the O. viciifolia cp genome is the loss of the atpF intron; whereas, O. gaubae possesses this intron. The atpF gene of O. gaubae is 1261 bp long with one intron of 702 bp, exon 1 of 144 bp and exon 2 of 415 bp. While the atpF gene of O. viciifolia is 558 bp long. Introns which are generally conserved regions among land plants play an important role in the expression of genes by increasing their transcription. Introns as the mobile genetic elements in the plastome, are mainly classified as either group I and group II. Group I and group II introns are derivatives of self-splicing RNA enzymes (ribozymes). Group I introns are present in rRNA, tRNA and protein-coding regions, while group II introns are found primarily in protein-coding genes [39, 40]. There are 17 to 20 introns classified under group II in the cp genome of land plants [40]. The atpF gene has a conserved group II intron which has been found in the most previously sequenced land plant plastomes [40]. The atpF intron is rarely lost in flowering plants but some intronless chloroplast genomes have been reported, including Manihot (Euphorbiaceae)[40], Passiflora (Passifloraceae) [41] and several taxa across the IRLC (Colutea nepalensis, Lessertia frutescens, Oxytropis bicolor, O. racemosa and Sphaerophysa salsula) [42]. The loss of intron in atpF gene is yet to be determined in other taxa of Papilionoideae and IR-lacking clade. It has been suggested that recombination between an edited mRNA and the atpF gene may be a possible mechanism for the loss of intron [40]. Structural variations such as intron presence/absence can be useful as a molecular marker to provide informative characters at low taxonomic levels in phylogenetic studies [22]. Another structural change in plastome of O. viciifolia is the inversion of ycf2/trnI(CAU)/trnL(CAA) genes. Among angiosperms, most of the plastid genome inversions are found in the LSC region [5], while plastome inversion in the O. viciifolia is located within the IR region. The same inversion has also occurred in the plastomes of two species of Astragalus [43]. Plastome inversions due to the relative rarity and easily determined homology (no homoplasy), are highly valuable and useful in phylogenetic studies [5]. The main cause of inversions is not fully understood, but intramolecular recombination between dispersed short inverted/direct repeats and tRNA genes is an accepted explanation [44, 45].

Numerous plastomes have now been sequenced that contains IRs with different sizes and other taxa that lack one copy of IR entirely such as the Inverted Repeat Lacking Clade (IRLC) in subfamily Papilionoideae of Fabaceae. As mentioned above, Onobrychis as a member of tribe Hedysareae, belongs to the IR-lacking clade. Plastome IRa loss in the IRLC taxa which is considered as a strong phylogenetic signal in the clade, has been confirmed several times in the previous studies [14, 46, 47]. In this study, to verify the lack of IRa region in O. gaubae, two primer pairs were designed. PCR amplification was only successful when using the diagnostic primers pair for the absence of the IRa.

Papilionoideae, in particular the IRLC, displays genomic structural variations which provide informative characters to increase phylogenetic resolution and make the taxon an excellent model for genome evolution studies [5, 22]. The plastomes of several members of the IRLC have regions with significant variations, rearrangements and accelerated mutation rates, including loss of introns from rps12 and clpP genes [21], absence of rps16 gene [28] and transfer/loss of rpl22 to the nucleus [21]. Numerous studies have also shown some other rearrangements in some IRLC taxa, such as loss of accD gene in six species of Trifolium [10, 22], loss of rpl23 and rpl33 genes in some species of Lathyrus, Pisum and Vicia [34] and loss of ycf4 gene in some species of Lathyrus and Pisum [15, 16]. As revealed in other studies, there are several reasons for the occurrence of rearrangements in the plastome, such as the lack of one IR region, size variation of IR region and many tandemly repeated sequences [48]. For example, the loss of the rps16 gene was probably due to the presence of a nuclear rps16 copy, which contributed to the pseudogenization of the plastid copy [48]. Likewise, the lack or expansion of the accD gene was explained by the presence of tandemly repeated sequences [6, 15].

As previously mentioned, the plastomes of Papilionoideae, particularly IR-loss clade, are not conserved in their genomic structure in terms of gene order and gene content and exhibit numerous rearrangements and gene/intron losses [5, 21, 22]. In this context, our results showed that the lengths of the IRLC plastid genomes ranged from 121,020 to 130,561 bp. This suggests that the IRLC cp genomes may have undergone different evolutionary processes such as gene/intron loss, insertion/deletion and IR/LSC/SSC expansion/contraction [49]. The plastomes among the IRLC taxa were similar in GC content but higher GC content was usually detected in the IR region compared to the other regions of cp genome, which is mainly due to the presence of rRNA genes (rrn23, rrn16, rrn5, rrn4.5) with high GC content (50%-56.4%) in IRs [6, 35]. One of the factors that shape codon usage biases in different organisms is the GC content in codon positions. Codon usage bias indicates the importance of molecular evolutionary phenomena. As mentioned above, codon usage patterns are similar between two Onobrychis species and also across the IRLC.

Whole plastid genome alignments can elucidate the level of sequence divergence and easily identify large indels, which are extremely useful for phylogenetic analyses and plant identification. In the present study, our results showed that the sequence divergence was distributed in the LSC and IR regions in the IRLC. Three highly variable regions (clpP, ycf1, ycf2) were observed with higher Pi values and were located in the LSC and IR regions, respectively. The gene ycf1 with the highest nucleotide diversity is more variable than matK and it can be useful for molecular systematics at low taxonomic levels [50, 51]. Furthermore, several divergence hotspots between Onobrychis species were identified, including ycf1, ycf2, clpP, accD, ycf4 (as the protein-coding regions) and trnL(UAA)-trnT(UGU) and trnT(GGU)-trnE(UUC) (as the intergenic regions). Several studies [14, 18, 52] analyzed the phylogenetic reconstructions of the IRLC species at various taxonomic levels based on different plastid genes such as matK, ndhF and rbcL, the nuclear ribosomal ITS and the combined sequences of these genes/spacers. We could use the highly variable regions acquired from this study to develop the potential phylogenetic markers which can be useful for species authentication and reconstruction of phylogeny within different tribes/genera of the IR-lacking clade in further studies.

In this study, we found many repeat regions including forward repeats, palindromic repeats and reverse repeats, which could be important hotspots for genome reconfiguration. Forward types were the most frequent in the IR-loss clade. Furthermore, repeat sequences were mainly distributed in non-coding regions (IGS) across the IRLC. As mentioned above, repeat structures induce indels and substitutions resulting in the mutation hotspot in the reconfiguration of genome [6]; therefore, these repeats can provide valuable information for phylogenetic and population studies [31]. In the IR-loss clade, mononucleotide repeats were highly abundant and were mostly composed of A/T rather than G/C repeats. Strong A/T bias in SSR loci was also observed in other legumes such as Vigna radiate [53], Arachis hypogaea [54] and Stryphnodendron adstringens [35] which, like other plastomes of species, may contribute to the bias in base composition [6]. The results showed that SSR loci of LSC region appeared more frequently than SSC or IR regions, which may be hypothesized that this phenomenon is relevant to the lack of one IR region in the IR-loss clade. In general, cpSSRs show abundant variation and might provide useful information for detecting intra- and interspecific polymorphisms at the population level [33, 36].

Plastid RNA editing prediction and Ka/Ks ratio

RNA editing is one of the post-transcriptional mechanisms which converts cytidine (C) to uridine (U) or U to C at specific sites of RNA molecules and modifies the genetic information from the genome in the plastids and mitochondria of land plants. RNA editing serves as a mechanism to correct missense mutations of genes by inserting, deleting and modifying nucleotides in a transcript [55]. In the present study, the editing sites were mostly observed in ndh genes. In this regard, the highest number of plastid editing sites was found in the ndh group genes in flowering plants [55]. Moreover, the ndh genes encoding a thylakoid Ndh complex, have been lost or pseudogenized in different species of algae, bryophytes, pteridophytes, gymnosperms, monocots, eudicots, magnoliids, and protists [56–58]. The RNA editing is probably important for the NDH protein complex function and may also lead to improved photosynthesis and display positive selection during evolution [55].

Moreover, we estimated the Ka/Ks for each gene in DnaSP v.6.12 [37]. Acceleration of the evolutionary rate was observed only in the accD gene. Some previous studies have investigated whether selective pressure is acting on a particular protein-coding gene in different genera/tribes of IR-loss clade. For instance, positive selection analyses suggested that Lathyrus, Pisum and Vavilovia, all belonging to tribe Fabeae, have undergone adaptive evolution in the ycf4 gene [15, 16]. Legume chloroplast genomes, and in particular IRLC, have regions with high mutation rates, including rps16-accD-psaI-ycf4-cemA region. rps16 gene was lost from cpDNA in the common ancestor of the IR-loss clade [15]. accD was completely absent in the T. subgenus Trifolium and has nuclear copies in Medicago truncatula and Cicer arietinum [22]. Three consecutive genes psaI-ycf4-cemA is situated in a local mutation hotspot and has been lost in some species of Lathyrus [15, 16].

Phylogenetic relationships

With the use of the whole cp genome coding sequence from 28 representative species of the IR-loss clade, a highly consistent topology was recovered by ML and Bayesian analyses (Fig. 5). The monophyly of the IRLC was consistent with all previous studies [5, 14, 22, 42]. As shown in the previous studies, tribe Wisterieae together with tribe Glycyrrhizeae were the first diverging lineage as sister to the remaining taxa [19, 20, 42, 59, 60]. Tribes Caraganeae and Hedysareae were grouped together. Many previous studies showed that Astragalus was sister to the genus Oxytropis but recent study on the chloroplast phylogenomics of Astragalus reported that Astragalus is a monophyletic clade and Oxytropis is sister to the Coluteoid clade [42], which is in agreement with the present study. Cicereae + Trifolieae + Fabeae formed a well-supported clade. The results of the present study suggest that there is no conflict between the phylogeny made by whole cp genome and that inferred by individual gene datasets. Therefore, a phylogenetic reconstruction for IR-loss clade species studied here showed that plastid genome database will be a helpful resource for molecular phylogeny at the higher taxonomic level (generic to tribal rank).

Conclusions

In this study, the complete plastome sequence of O. gaubae (122,688 bp) was determined. The gene contents and gene orientation of O. gaubae plastome are similar to those found in the plastid genome of other IRLC species. Comparison of plastomes across IRLC showed that the coding regions are more conserved than non-coding regions and IR is more conserved than LSC and SSC regions. The present study also analyzed genetic information in the IRLC plastomes including the distribution and location of repeat sequences and SSRs, codon usage, RNA editing prediction, hotspot regions and phylogenomic analysis. Moreover, we identified three hotspot genes (ycf1, ycf2, clpP) which provided sufficient genetic information for species identification and phylogenetic reconstruction of the IRLC species. Seven hypervariable regions including ycf1, ycf2, clpP, accD and ycf4 (as the protein-coding regions) and trnL(UAA)-trnT(UGU) and trnT(GGU)-trnE(UUC) (as the intergenic regions) were also identified between Onobrychis species, which could be used to distinguish species. Finally, the data obtained from this study could provide a useful resource for further research on tribe Hedysareae and also IR-loss clade at the genomic scale.

Methods

Chloroplast DNA extraction and sequencing

The young leaves of O. gaubae were collected from the southern slopes of Alborz mountain range in Tehran, Iran. It was identified by Professor S. Kazempour-Osaloo. This species was preserved in the Tarbiat Modares University Herbarium (TMUH) (voucher code: 2016–1). Permission was not necessary for collecting the samples, which has not been included in the list of national key protected plants. The fresh leaves were immediately dried with silica gel for further DNA extraction. Our experimental research, including the collection of plant materials, are complies with institutional, national or international guidelines. Genomic DNA was extracted from dried leaves using a DNeasy Plant Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality and quantity were tested using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and the resulting DNA was sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq-2000 platform at Iwate Biotechnology Research Center. The paired-end libraries were constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). In total, 43,189,861 paired-end reads each comprising 100-bp sequence were obtained.

Genome assembly and annotation

Using the complete plastid genome of Onobrychis viciifolia (MW007721) as the reference, the paired-end reads of O. gaubae were filtered and assembled in to a complete plastome using Fast-Plast (https://github.com/mrmckain/Fast-Plast) [61]. Furthermore, we compared the chloroplast genome of O. gaubae with the complete chloroplast sequence of other Hedysareae species (Hedysarum and Alhagi species). Gaps in the cpDNA sequences were filled by PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing. The de novo assembled chloroplast genomes were annotated by GeSeq [62]. We used the online tRNAscan-SE service [63] to improve the identification of tRNA genes. To detect the number of matched reads and the depth of coverage, raw reads were remapped to the assembled plastomes with Bowtie2 [64] as implemented in Geneious v.9.0.2. The entire chloroplast genome sequences of O. gaubae was deposited in GenBank (Accession Number: LC647182).

To confirm the lack of IRa in the O. gaubae, it was surveyed by PCR and Sanger sequencing. A PCR strategy using primer pairs diagnostic for the presence or absence of the IRa region was conducted. The primer pairs were designed in either conserved ndhF and psbA, or rps19 and rpl2 protein coding sequences which are flanking the IR region boundaries, to allow the assessment of the presence or absence of the IRa region. The primer pairs used to detect the absence or presence of the IRa were: ndhF-F (5′-TATATGATTGGTCATATAATCG-3′) [65] and psbA-R (5′-GTTATGCATGAACGTAATGCTC-3′) [66]; rps19-F (5′-GTTCTGGACCAAGTTATT-3′) and rpl2-R (5′-ATTTGATTCTTCGTCGAC-3′) (designed in this study). The PCR amplification was carried out in the volume of 20 μl, containing 8 μl deionized water, 10 μl of the 2 × Taq DNA polymerase master mix Red (Amplicon), 0.5 μl of each primer (10 pmol/μl), and 1 μl of template DNA. PCR procedures for both regions were 2 min at 94 °C for predenaturation followed by 38 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C for denaturation, 1 min at 57 °C (when using ndhF-F and psbA-R primers) and 45 s at 56 °C (when using rps19-F and rpl2-R primers) for primer annealing and 50 s at 72 °C for primer extension, followed by a final primer extension of 5 min at 72 °C. PCR fragments were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 1 × TAE (pH = 8) buffer, stained with ethidium bromide and were photographed with a UV gel documentation system (UVItec, Cambridge, UK). PCR products along with the primers used for amplifcation were sent for Sanger sequencing at Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea).

Codon usage

Codon usage was determined for all protein-coding genes. The codon usage analysis was performed in the web server Bioinformatics (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/codon_usage.html). Furthermore, the relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values were determined with MEGA X [67], which was used to reveal the characteristics of the variation in synonymous codon usage.

Characterization of repeat sequences

REPuter [68] was used to identify forward repeats, reverse sequences, complementary and palindromic sequences, with a minimal size of 30 bp, hamming distance of 3 and over 90% identity. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected using the microsatellite identification tool MISA (available online: http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/misa.html). The minimum numbers of the SSR motifs were 10, 5, 4, 3, 3 and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide repeats, respectively.

Divergent hotspots identification and synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rate analysis

To assess the nucleotide diversity (Pi) among the plastid genomes of the representative species of the IRLC, the whole chloroplast genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT [69] on XSEDE v.7.402 in CIPRES Science Gateway [70]. A sliding window analysis was conducted to determine the nucleotide diversity of the chloroplast genome using DnaSP v.6.12 software [37]. The window length was set to 800 bp and the step size was 200 bp. Furthermore, the protein-coding regions of the 28 chloroplast genomes were used to evaluate evolutionary rate variation within the IRLC. Thus, we aligned the 75 protein-coding genes separately using MAFFT and then estimated the synonymous (Ks) and non-synonymous (Ka) substitution rates, as well as their ratio (Ka/Ks) using DnaSP v.6.12 software.

Genome comparison

To investigate divergence in chloroplast genomes, identity across the whole cp genomes was visualized using the mVISTA viewer in the Shuffle-LAGAN mode [71] among the 19 IRLC accessions using Glycyrrhiza glabra as the reference.

Prediction of potential RNA editing sites

Thirty-five protein-coding genes of O. gaubae were used to predict potential RNA editing sites using the Predictive RNA Editor for Plants (PERP)-Cp web server (http://prep.unl.edu) [72] with a cutoff value of 0.8.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

Seventy-five protein-coding genes were recorded from 28 species within IRLC, as well as from two outgroups [Robinia pseudoacacia L. and Lotus japonicus (Regel) K.Larsen]. The complete cp genome of O. gaubae obtained from this study and other 29 cp genomes downloaded from GenBank (Additional File 8: Table S12). The concatenated data were analyzed using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference methodologies. Prior to maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses, a general time reversible and gamma distribution (GTR + G) model was selected using the MrModeltest2.2 [73] under the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC )[74]. Maximum likelihood analyses were performed using the online phylogenetic software W-IQ-TREE [75] available at http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at. Nodes supports were calculated via rapid bootstrap analyses with 5000 replicates. Bayesian inference was performed using MrBayes v.3.2 in the CIPRES [70] with the following settings: Markov chain Monte Carlo simulations for 5,000,000 generations with four incrementally heated chains, starting from random trees and sampling one out of every 1,000 generations. The first 25% of the trees were regarded as burn-ins. The remaining trees were used to construct a 50% majority-rule consensus tree and to estimate posterior probabilities. Posterior probabilities (PP) > 0.95 were considered as significant support for a clade.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Genes with intron in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome, including the exon and intron length. Table S2. Codon usage for O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S3. Codon usage for O. viciifolia chloroplast genome.

Additional file 2: Table S4. Putative preferred codons in the IRLC plastid genomes. RSCU = relative synonymous codon usage.

Additional file 3: Table S5. Forward, Reverse and Palindromic repeat sequences in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S6. Forward, Reverse and Palindromic repeat sequences in the O. viciifolia chloroplast genome. Table S7. Distribution of simple sequence repeat (SSR) in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S8. Distribution of simple sequence repeat (SSR) in the O. viciifolia chloroplast genome.

Additional file 4: Figure S1. Nucleotide variability (%) values between O. gaubae and O. viciifolia species.

Additional file 5: Figure S2. Sequence identity plot comparing the IRLC chloroplast genomes with Glycyrrhiza glabra as a reference.

Additional file 6: Table S9. The Ka, Ks and Ka/Ks ratio of IRLC chloroplast genome for individual genes and region.

Additional file 7: Table S10. Prediction of RNA editing sites in chloroplast genes of O. gaubae. Table S11. Prediction of RNA editing sites in chloroplast genes of O. viciifolia.

Additional file 8: Table S12. Accession number and sampled chloroplast genomes obtained from GenBank.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- SSR

Simple sequence repeat

- cp

Chloroplast

- IRs

Inverted repeats

- LSC

Large single-copy

- SSC

Small single-copy

- IRLC

Inverted repeat lacking clade

- ML

Maximum-likelihood

- Ks

Synonymous substitution rates

- Ka

Nonsynonymous substitution rates

- RSCU

Relative synonymous codon usage

- DnaSP

DNA sequence polymorphism

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology

- Pi

Nucleotide diversity/polymorphism

- GTR

General time reversible

- ITS

Internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA

- rRNA

Ribosomal RNA

- tRNA

Transfer RNA

Authors’ contributions

M. M. and S. K. O. conceived the idea, designed the study and carried out the plant sampling; M. M., A. O. and M. S. extracted chloroplast DNA for next generation sequencing, A. O. and M. S. assembled the genome, M. M. and A. O. performed the manual genome annotation, M. M. performed the phylogenetic and computational analyses, M. M. wrote the paper. R. T. and S. K. O. edited and reviewed the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Kyoto University, Iwate Biotechnology Research Center and Tarbiat Modares University. The funders had no role in the design of the study, analysis of data, decision to publish and in manuscript preparation.

Availability of data and materials

Sequences used in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (see Additional file 8: Table S12). Annotated sequence of plastome of O. gaubae were submitted to GenBank (http://getentry.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) under LC647182 accession number. Sample of O. gaubae is saved at the Tarbiat Modares University Herbarium, Tehran, Iran.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mahtab Moghaddam, Email: mahtabmoghaddam@modares.ac.ir.

Shahrokh Kazempour-Osaloo, Email: skosaloo@modares.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Jansen RK, Ruhlman TA. In Genomics of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. Plastid Genomes of Seed Plants; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK. The plastid genomes of flowering plants. In: Maliga P, editor. Chloroplast biotechnology: methods and protocols. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Springer, Humana Press; 2014. p. 3–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jansen RK, Raubeson LA, Boore JL, dePamphilis CW, Chumley TW, Haberle RC, et al. Methods for obtaining and analyzing whole chloroplast genome sequences. Methods Enzymol. 2005;395:348–384. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)95020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bock R. Structure, function, and inheritance of plastid genomes. In: Bock R, editor. Cell and molecular biology of plastids. Berlin: Springer; 2007. p. 29–63.

- 5.Schwarz EN, Ruhlman TA, Sabir JSM, Hajrah NH, Alharbi NS, Al-Malki AL, et al. Plastid genome sequences of legumes reveal parallel inversions and multiple losses of rps16 in papilionoids. J Syst Evol. 2015;53:458–468. doi: 10.1111/jse.12179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asaf S, Khan AL, Aaqil Khan M, Muhammad Imran Q, Kang S-M, Al-Hosni K, et al. Comparative analysis of complete plastid genomes from wild soybean (Glycine soja) and nine other Glycine species. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182281. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KJ, Choi KS, Jansen RK. Two chloroplast DNA inversions originated simultaneously during the early evolution of the sunflower family (Asteraceae) Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(9):1783–92. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haberle RC, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Tracheliumcaeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes. J Mol Evol. 2008;66(4):350–61. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greiner S, Wang X, Rauwolf U, Silber MV, Mayer K, Meurer J, et al. The complete nucleotide sequences of the five genetically distinct plastid genomes of Oenothera, subsection Oenothera: I. Sequence evaluation and plastome evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(7):2366–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai Z, Guisinger M, Kim H-G, Ruck E, Blazier JC, McMurtry V, et al. Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome of Trifoliumsubterraneum (Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions. J Mol Evol. 2008;67(6):696–704. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guisinger MM, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extreme reconfiguration of plastid genomes in the angiosperm family Geraniaceae: rearrangements, repeats, and codon usage. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(1):583–600. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer JD, Osorio B, Thompson WF. Evolutionary significance of inversions in legume chloroplast DNAs. Curr Genet. 1988;14:65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00405856. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legume Phylogeny Working Group Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny. Taxon. 2017;66:44–77. doi: 10.12705/661.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojciechowski MF, Lavin M, Sanderson MJ. A phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae) based on analysis of the plastid matK gene resolves many well-supported subclades within the family. Am J Bot. 2004;91:1846–1862. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.11.1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magee AM, Aspinall S, Rice DW, Cusack BP, Semon M, Perry AS, et al. Localized hypermutation and associated gene losses in legume chloroplast genomes. Genome Res. 2010;20:1700–1710. doi: 10.1101/gr.111955.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moghaddam M, Kazempour-Osaloo S. Extensive survey of the ycf4 plastid gene throughout the IRLC legumes: Robust evidence of its locus and lineage specific accelerated rate of evolution, pseudogenization and gene loss in the tribe Fabeae. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0229846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan L, Yang X, Liu P, Johnson G, Wen J, Chang Z. A molecular phylogeny of Caraganeae (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) reveals insights in to new generic and infrageneric delimitations. PhytoKeys. 2016;70:111–137. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.70.9641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moghaddam M, Kazempour Osaloo S, Hosseiny H, Azimi F. Phylogeny and divergence times of the Coluteoid clade with special reference to Colutea (Fabaceae) inferred from nrDNA ITS and two cpDNAs, matK and rpl32-trnL(UAG) sequences data. Plant Biosyst. 2017;6:1082–1093. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2016.1244120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Compton JA, Schrire BD, Konyves K, Forest F, Malakasi P, Mattapha S, et al. The Callerya Group redefined and Tribe Wisterieae (Fabaceae) emended based on morphology and data from nuclear and chloroplast DNA sequences. PhytoKeys. 2019;125:1–112. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.125.34877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan L, Han L-N, Sirichamorn Y, Wen J, Compton JA, Deng S-W, et al. Proposal to recognise the tribes Adinobotryeae and Glycyrrhizeae (Leguminosae subfamily Papilionoideae) based on chloroplast phylogenomic evidence. PhytoKeys. 2021;181:65–77. doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.181.71259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen RK, Wojciechowski MF, Sanniyasi E, Lee SB, Daniell H. Complete plastid genome sequence of the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) and the phylogenetic distribution of rps12 and clpP intron losses among legumes (Leguminosae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;48:1204–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabir J, Schwarz E, Ellison N, Zhang J, Baeshen NZ, Mutwakil M, et al. Evolutionary and biotechnology implications of plastid genome variation in the inverted-repeat-lacking clade of legumes. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12:743–754. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurdon C, Maliga P. Two distinct plastid genome configurations and unprecedented intraspecies length variation in the accD coding region in Medicago truncatula. DNA Res. 2014;21(4):417–427. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsu007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amirahmadi A, Kazempour Osaloo S, Moein F, Kaveh A, Maassoumi AA. Molecular systematic of the tribe Hedysareae (Fabaceae) based on nrDNA ITS and plastid trnL-F and matK sequences. Plant Syst Evol. 2014;300:729–747. doi: 10.1007/s00606-013-0916-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rechinger KH. Papilionaceae II, Flora Iranica. In: Rechinger KH, editor. Tribus Hedysareae Graz. Akademische Druckund Verlagsanstalt; 1984. p.387–464.

- 26.Lock JM. Legumes of the World. In: Lewis G, Schrire B, Mackinder B, Lock M, editors. Tribe Hedysarae. Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens; 2005. p.489–495.

- 27.Kaveh A, Kazempour-Osaloo S, Amirahmadi A, Maassoumi A, Schneeweiss G. Systematics of Onobrychis sect. Heliobrychis (Fabaceae): morphology and molecular phylogeny revisited. Plant Syst Evol. 2019;305:33–48. doi: 10.1007/s00606-018-1549-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Palmer JD. Multiple independent losses of two genes and one intron from legume chloroplast genomes. Syst Bot. 1995;20:272–294. doi: 10.2307/2419496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fu X, Ji X, Wang B, Duan L. The complete chloroplast genome of leguminous forage Onobrychis viciifolia. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2021;6:898–899. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1886017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharp PM, Li WH. The codon adaptation index-a measure of directional synonymous codon usage bias, and its potential applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(3):1281–1295. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.3.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.X Li W Tan J Sun J Du C Zheng X Tian et al 2019 Comparison of Four Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Medicinal and Ornamental Meconopsis Species: Genome Organization and Species Discrimination Sci Rep10.1038/s41598-019-47008-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Li CJ, Wang RN, Li DZ. Comparative analysis of plastid genomes within the Campanulaceae and phylogenetic implications. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0233167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Powell W, Morgante M, Mcdevitt R, Vendramin GG, Rafalski JA. Polymorphic Simple Sequence Repeat Regions in Chloroplast Genomes-Applications to the Population-Genetics of Pines. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92(17):7759–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.W Lei D Ni Y Wang J Shao X Wang D Yang et al 2016 Intraspecific and heteroplasmic variations, gene losses and inversions in the chloroplast genome of Astragalus membranaceus Sci Rep10.1038/srep21669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.UJBD Souza R Nunes CP Targueta JAF Diniz-Filho MPD Telles 2019 The complete chloroplast genome of Stryphnodendron adstringens (Leguminosae - Caesalpinioideae): comparative analysis with related Mimosoid species Sci Rep10.1038/s41598-019-50620-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Zong D, Gan P, Zhou A, Li J, Xie Z, Duan A, et al. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of seven Populus species: Insights into alternative female parents of Populustomentosa. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(6):e0218455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Mol Biol Evol. 2017;34:3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Wong WSW, Nielsen R. Bayes empirical bayes inference of aminoacid sites under positive selection. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1107–1118. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saldanha R, Mohr G, Belfort M, Lambowitz AM. Group I and group II introns. FASEB J. 1993;7(1):15–24. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Daniell H, Wurdack KJ, Kanagaraj A, Lee S-B, Saski C, Jansen RK. The complete nucleotide sequence of the cassava (Manihot esculenta) chloroplast genome and the evolution of atpF in Malpighiales: RNA editing and multiple losses of a group II intron. Theor Appl Genet. 2008;116:723–737. doi: 10.1007/s00122-007-0706-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, de Pamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relation-ships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary pat-terns. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:19369–19374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.C Su L Duan P Liu J Liu Z Chang J Wen 2021 Chloroplast phylogenomics and character evolution of eastern Asian Astragalus (Leguminosae): Tackling the phylogenetic structure of the largest genus of flowering plants in Asia Mol Phylogenet Evol10.1016/j.ympev.2020.107025 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Charboneau JLM, Cronn RC, Liston A, Wojciechowski MF, Sanderson MJ. Plastome structural evolution and homoplastic inversions in Neo-Astragalus (Fabaceae) Genome Biol Evol. 2021;13:1–20. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evab215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sloan DB, Triant DA, Forrester NJ, Bergner LM, Wu M, Taylor DR. Arecurring syndrome of accelerated plastid genome evolution in the angiosperm tribe Sileneae (Caryophyllaceae) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2014;72:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang HX, Liu H, Moore MJ, Landrein S, Liu B, Zhu ZX, et al. Plastid phylogenomic insights into the evolution of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. (Dipsacales). Mol Phylogenet. Evol. 2020 10.1016/j.ympev.2019.106641. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Palmer JD, Osorio B, Aldrich J, Thompson WF. Chloroplast DNA evolution among legumes: loss of a large inverted repeat occurred prior to other sequence rearrangements. Curr Genet. 1987;11:275–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00355401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavin M, Doyle JJ, Palmer JD. Evolutionary significance of the loss of the chloroplast–DNA inverted repeat in the Leguminosae subfamily Papilionoideae. Evolution. 1990;44:390–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller J, Rousseau-Gueutin M, Martin GE, Morice J, Boutte J, Coissac E, et al. The evolutionary fate of the chloroplast and nuclear rps16 genes as revealed through the sequencing and comparative analyses off our novel legume chloroplast genomes from Lupinus. DNA Res. 2017;24:343–358. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: Gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76:273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neubig KM, Whitten WM, Carlsward BS, Blanco MA, Endara L, Norris H, et al. Phylogenetic utility of ycf1 in orchids: a plastid gene more variable than matK. Plant Syst Evol. 2009;277:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00606-008-0105-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong W, Xu C, Li C, Sun J, Zuo Y, Shi S, et al. ycf1, the most promising plastid DNA barcode of land plants. Sci Rep. 2015;5:8345. doi: 10.1038/srep08348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaefer H, Hechenleitner P, Santos-Guerra A, Sequeira MMD, Pennington RT, Kenicer G, et al. Systematics, biogeography, and character evolution of the legume tribe Fabeae with special focus on the middle-atlantic island lineages. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.S Tangphatsornruang D Sangsrakru J Chanprasert P Uthaipaisanwong T Yoocha N Jomchai et al 2010 The Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Mungbean (Vigna radiata) Determined by High-throughput Pyrosequencing: Structural Organization and Phylogenetic Relationships DNA Res10.1093/dnares/dsp025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Yin D, Wang Y, Zhang X, Ma X, He X, Zhang J. Development of chloroplast genome resources for peanut (Arachis hypogaea L) and other species of Arachis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11649. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He P, Huang S, Xiao G, Zhang Y, Yu J. Abundant RNA editing sites of chloroplast protein-coding genes in Ginkgo biloba and an evolutionary pattern analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:257. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blazier J, Guisinger MM, Jansen RK. Recent loss of plastid-encoded ndh genes within Erodium (Geraniaceae) Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruhlman TA, Chang W-J, Chen JJW, Huang Y-T, Chan M-T, Zhang J, et al. NDH expression marks major transitions in plant evolution and reveals coordinate intracellular gene loss. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0484-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.MJ Sanderson D Copetti A Burquez E Bustamante JLM Charboneau LE Eguiarte et al 2015 Exceptional reduction of the plastid genome of saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea): Loss of the ndh gene suite and inverted repeat Am J Bot10.3732/ajb.1500184 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Duan L, Harris AJ, Su C, Zhang Z-R, Arslan E, Ertugrul K, et al. Chloroplast Phylogenomics Reveals the Intercontinental Biogeographic History of the Liquorice Genus (Leguminosae: Glycyrrhiza) Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:793. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.M-Q Xia R-Y Liao J-T Zhou H-Y Lin J-H Li P Li et al 2021 Phylogenomics and biogeography of Wisteria: implication on plastome evolution among inverted repeat-lacking clade (IRLC) legumes J Syst Evol10.1111/jse.12733

- 61.McKain MR, Wilson M. mrmckain/Fast-Plast: Fast-Plast v.1.2.8. Version v.1.2.8. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, et al. GeSeq – versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. The tRNA scan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W686–W9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olmstead RG, Sweere JA. Combining data in phylogenetic systematics: An empirical approach using three molecular data sets in the Solanaceae. Syst Biol. 1994;43:467–481. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/43.4.467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sang T, Crawford DJ, Stuessy TF. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae) Am J Bot. 1997;84(9):1120–1136. doi: 10.2307/2446155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Geigerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Sofware Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES science gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. New Orleans: Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mower JP. The PREP suite: Predictive RNA editors for plant mitochondrial genes, chloroplast genes and user-defined alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W253–W259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Uppsala: Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Posada D, Buckley TR. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst Biol. 2004;53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trifinopoulos J, Nguyen LT, Haeseler A, Minh BQ. W-IQ-TREE: a fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W232–W235. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Genes with intron in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome, including the exon and intron length. Table S2. Codon usage for O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S3. Codon usage for O. viciifolia chloroplast genome.

Additional file 2: Table S4. Putative preferred codons in the IRLC plastid genomes. RSCU = relative synonymous codon usage.

Additional file 3: Table S5. Forward, Reverse and Palindromic repeat sequences in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S6. Forward, Reverse and Palindromic repeat sequences in the O. viciifolia chloroplast genome. Table S7. Distribution of simple sequence repeat (SSR) in the O. gaubae chloroplast genome. Table S8. Distribution of simple sequence repeat (SSR) in the O. viciifolia chloroplast genome.

Additional file 4: Figure S1. Nucleotide variability (%) values between O. gaubae and O. viciifolia species.

Additional file 5: Figure S2. Sequence identity plot comparing the IRLC chloroplast genomes with Glycyrrhiza glabra as a reference.

Additional file 6: Table S9. The Ka, Ks and Ka/Ks ratio of IRLC chloroplast genome for individual genes and region.

Additional file 7: Table S10. Prediction of RNA editing sites in chloroplast genes of O. gaubae. Table S11. Prediction of RNA editing sites in chloroplast genes of O. viciifolia.

Additional file 8: Table S12. Accession number and sampled chloroplast genomes obtained from GenBank.

Data Availability Statement

Sequences used in this study are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (see Additional file 8: Table S12). Annotated sequence of plastome of O. gaubae were submitted to GenBank (http://getentry.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/) under LC647182 accession number. Sample of O. gaubae is saved at the Tarbiat Modares University Herbarium, Tehran, Iran.