Abstract

Background:

Many people who report resolving an alcohol or other drug (AOD) problem continue some level of substance use. Little information exists, however, regarding the prevalence of this resolution pathway, or how continued substance use after resolving an AOD problem, relative to abstinence, relates to functioning, quality of life, and happiness (i.e., well-being). Greater knowledge of the prevalence and correlates of non-abstinent AOD problem resolution could inform public health messaging and clinical guidelines, while encouraging substance use goals likely to maximize well-being and reduce risks.

Methods:

We analyzed data from a nationally representative sample of individuals who endorsed having resolved an AOD problem (N = 2,002). Analyses examined: (1) The prevalence of various substance use statuses coded from lowest to highest risk: (a) continuous abstinence from all AOD since problem resolution; (b) current abstinence from all AOD with some use since problem resolution; (c) current use of a substance reported as a secondary substance; (d) current use of the individual’s primary substance only; or, (e) current use of a secondary and primary substance; (2) relationships between substance use status and demographic, clinical, and service use history measures; and (3) the relationship between substance use status and well-being. Weighted, controlled, regression analyses examined the influence of independent variables on substance use status.

Results:

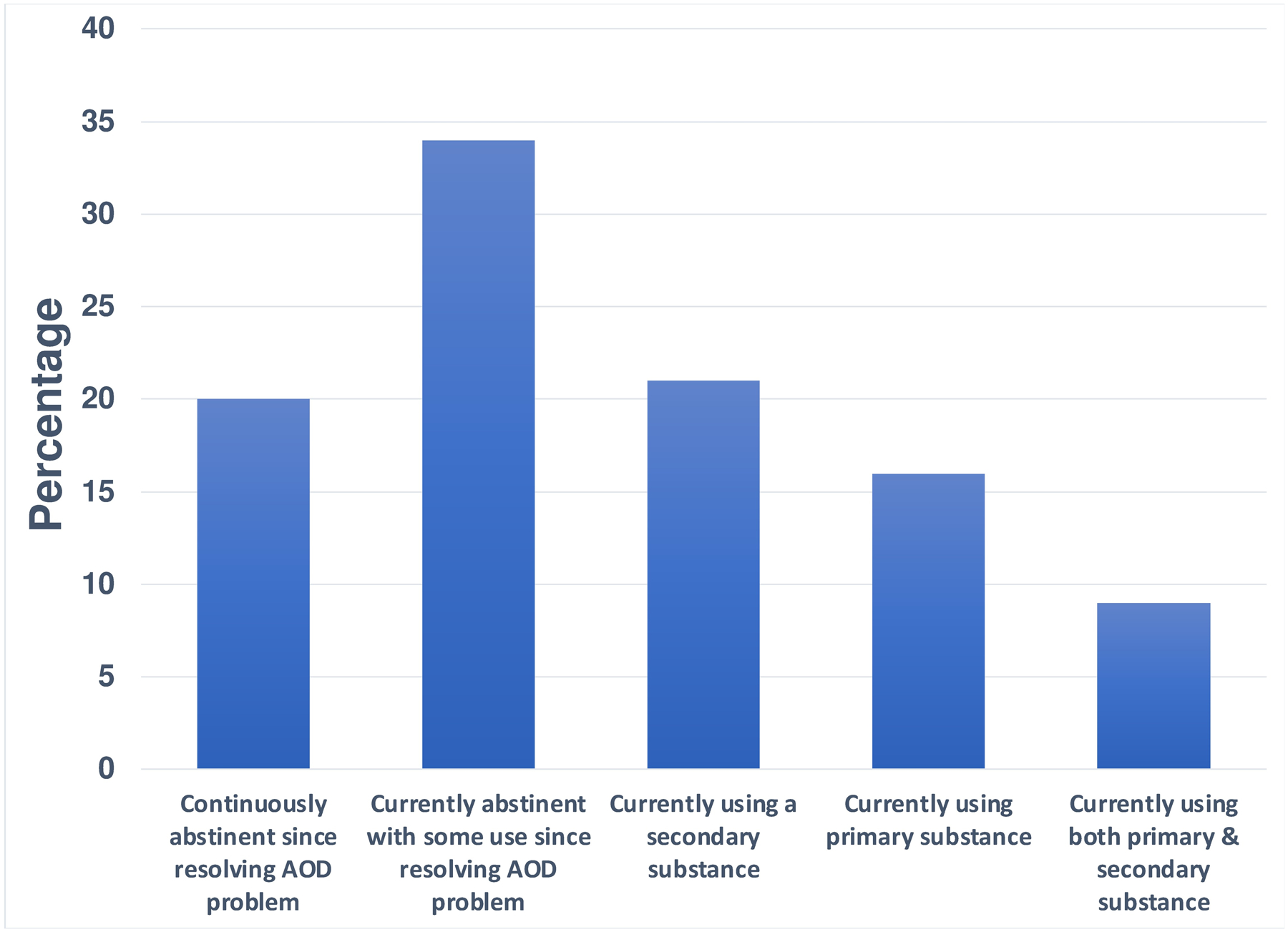

(1) Prevalence: In this sample, 20.3% of participants endorsed continuous abstinence; 33.7% endorsed current abstinence; 21.0% endorsed current use of a secondary substance; 16.2% endorsed current use of a primary substance; and 8.8% endorsed current use of both a secondary and a primary substance. (2) Correlates: Lower-risk substance use status was associated with the initiation of regular substance use at an older age, more years since problem resolution, and fewer lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. (3) Well-Being: Controlling for pertinent confounds, lower-risk substance use status was independently associated with greater self-esteem, happiness, quality of life and functioning, and recovery capital, as well as less psychological distress.

Conclusions:

About half of Americans who self-identify as having resolved an AOD problem continue to use AOD in some form. It appears that although abstinence is, for many, not a requisite for overcoming an AOD problem, it is likely to lead to better functioning and greater well-being. Further, people appear to gravitate toward abstinence/lower risk substance use with greater time since problem resolution.

Keywords: alcohol and other drug problem resolution, abstinence versus continued substance use, primary and secondary substances, well-being, recovery capital

Introduction

Abstinence-based models of addiction recovery dominated the substance use disorder (SUD) treatment landscape for most of the 20th Century and continue to dominate today (SAMHSA, 2013). SUD remission status in diagnostic classification systems, however, has always permitted non-abstinent SUD remission as an outcome, because standard diagnostic systems are focused on the presence or absence of substance-related symptoms and not the presence, or degree of substance use (e.g., substance use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM-5]; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Furthermore, there is evidence that total alcohol and other drug (AOD) abstinence is not a requisite for achieving addiction recovery, defined here as an experience that captures both resolution of substance use problems and the development of a “healthy, productive, and meaningful life” (White, 2007). A subset of individuals—mostly those with lower SUD severity—resolve their substance use problem (Kelly et al., 2017) and experience improved health and well-being despite ongoing substance use (Stea et al., 2015, Witkiewitz and Tucker, 2020). Such ongoing substance use may mean moderating use of a primary problem substance or abstaining from one or more substances while continuing the use of others (e.g., abstaining from opioids while consuming cannabis).

Some clinicians and researchers posit that the field’s current emphasis on abstinence-based recovery may fail to engage many individuals with SUD because of perceptions that a goal of abstinence is required to engage with care. From a broader public health perspective, increasing access to effective SUD interventions and recovery support services is likely to enhance their overall impact (Glasgow et al., 2003). Thus, it is believed that greater adoption of flexible, patient-centered treatment and recovery approaches that support non-abstinence goals and harm reduction are likely to attract and engage more individuals in substance use related health behavior change, in turn benefitting public health.

At the same time, abstinence tends to be associated with better recovery outcomes and more stable remission/recovery (Dawson et al., 2007, White and Kurtz, 2006), and any substance use itself increases risk for harm to physical, emotional, and cognitive health (Eddie et al., 2019, Degenhardt et al., 2018, Patel et al., 2016). Research can inform the content of public health messaging and clinical guidelines that balance the benefit of engaging as much of the SUD population in care as possible, while encouraging substance use goals likely to maximize well-being and reduce risk.

To date, research examining associations among abstinent and non-abstinent substance use status and well-being, has focused primarily on treatment-seeking individuals with alcohol use disorder. For instance, using Project Match data (Project MATCH Research Group, 1998), Witkiewitz et al. (2019) found that three years following alcohol use disorder treatment, those drinking heavily-defined as any instance of 5+ drinks in a day for men and 4+ for women during the most recent follow-up-were faring worst on measures such as depression, tension, concentration, and happiness with relationships, while abstainers and low-risk drinkers were not significantly different from one another on these psychosocial measures, with the exception that abstainers were more unhappy with life compared to low-risk drinkers. Using latent profile analyses, Witkiewitz and colleagues also found that while the greatest proportion of higher functioning individuals were abstinent or low-risk drinkers (51%), a smaller subset were characterized as higher functioning, occasional heavy drinkers (17%), though such individuals reported more drinking consequences on average, than those belonging to the low-risk/abstinent, higher functioning profile. Subsequently, the authors found that abstinence in this sample at three years did not predict better psychological functioning at ten years (Witkiewitz et al., 2020).

Also, the cross-sectional ‘What is Recovery?’ study sought to characterize individuals that self-identify as being ‘in recovery’ (Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014). An analysis of individuals reporting alcohol as their primary substance showed current abstinence was associated with significantly greater quality of life compared with non-abstinence, after controlling for individual characteristics.

These studies, with their emphasis on alcohol use disorder, focused on how alcohol use was associated with psychosocial outcomes. At the same time, many individuals in the Project Match sample endorsed continued cannabis and other drug use over the course of follow-up, which may have influenced outcomes in unknown ways. The What is Recovery study secondary analysis used a binary variable to operationalize substance use status and employed a non-representative sample.

This study sought to extend this previous research using a nationally representative sample capturing the continuum of substance use statuses, incorporating all substances used (i.e., alcohol and/or other drugs), with consideration given to the AOD that individuals indicated as their primary substance. Specifically, we leveraged the data from the National Recovery Study (Kelly et al., 2017) to investigate national prevalence of abstinent versus types of non-abstinent recovery pathways, their correlates, and relationships to indices of quality of life, functioning, and well-being in a nationally representative sample of United States (US) adults who endorse having resolved a problem with a range of substances.

The present study had three primary research questions: 1) What is the prevalence of these different types of substance use statuses among those who report having resolved an AOD problem in the US population? 2) What are the predictors of membership in these substance use status groups? and 3) What is the association between substance use status and current indices of well-being?

Prior research has shown greater overall well-being among those who are abstinent or engaged in less frequent and intense substance use (Witkiewitz et al., 2019, Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014), as well as greater stability among those in abstinence-based alcohol use disorder remission (Dawson et al., 2007). As such, we hypothesized lower risk AOD use status (i.e., no AOD use since AOD problem resolution or no current AOD use) would be independently associated with greater self-esteem, quality of life and functioning, happiness, and recovery capital, as well as less psychological distress, compared to higher risk AOD use status (i.e., use of primary substance, secondary substance, or both), controlling for relevant individual characteristics (e.g., time since AOD problem resolution, number of psychiatric diagnoses etc.).

Materials & Methods

Sample and Procedure

This is a secondary analysis of the National Recovery Study (Kelly et al., 2017), a nationally-representative survey of non-institutionalized individuals in the US aged 18 years and over that answered yes to the screener question about self-identified AOD problem resolution: “Did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” This research was approved by the Mass General Brigham institutional review board. Detailed data collection methods can be found in Kelly et al. (2017).

Data were collected by the survey company GfK, using a probability sampling approach. A representative subset of 39,809 individuals from the GfK KnowledgePanel were sent the screening question via email, to which 25,229 responded (63.4%). This response rate is similar to other nationally representative surveys (Grant et al., 2015, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013). Data were weighted using the method of iterative proportional fitting so as to represent the US civilian population (Battaglia et al., 2009). A total of 2,002 individuals who had resolved an AOD problem were included in the final analyses.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included, 1) sex, and 2) race/ethnicity (White/non-Hispanic; Black/non-Hispanic; Other/non-Hispanic; Hispanic; 2+ races/non-Hispanic).

Substance use characteristics

Participants were asked about their substance use history; specifically, which drugs they used ten times or more times in their lifetime. Substances included, ‘alcohol’, ‘marijuana’, ‘cocaine’, ‘heroin’, ‘narcotics other than heroin’, ‘methadone’, ‘buprenorphine’, ‘amphetamines’, ‘methamphetamine’, ‘benzodiazepines’, ‘barbiturates’, ‘hallucinogens’, ‘synthetic marijuana/synthetic drugs’, ‘inhalants’, ‘steroids’, or ‘other’.

Subsequently, to determine participants’ primary substance, they were also asked the following question, “You said the following substances were a problem for you. Which was your primary substance or drug of choice?”

Because of the relatively small number of participants endorsing some less commonly used drugs as their primary substance used, to ensure we retained necessary statistical power for the present analyses we created four categories of primary substance used: 1) alcohol, 2) cannabis, 3) opioids, and 4) ‘other’ for all other substances.

Age of first and last substance use

For each substance with lifetime use, participants indicated the age at which they first used the substance, age at which they initiated regular use (i.e.., weekly) if applicable, and age of last use for substances they no longer used at the time of survey completion. We defined age of initiation of regular substance use as the age at which participants started regularly using any substance.

Current substance use status

We defined participants’ substance use status with a five-level variable coded ordinally to indicate potential increasing risk as follows: 0= totally abstinent from all AOD since AOD problem resolution; 1= current abstinence from all AOD but with some substance use since resolving an AOD problem, 2= current use of only a substance perceived to be secondary for the individual, 3= current use of only the individual’s primary substance; 4= current use of both a secondary substance and the primary substance for that individual. To differentiate between total abstinence since problem resolution (coded 0) and current abstinence but with some use since problem resolution (coded 1), we compared age of problem resolution and age of last use for all substances participants reported having used. For the former, participants reported last use of all substances at or before their age of problem resolution and for the latter, participants reported last use of at least one substance after age of problem resolution. Of note, individuals with current substance use may have been abstinent at some point since resolving their problem, which is a possibility not captured by this variable.

Years since resolving an alcohol or other drug problem

Participants were asked, “How long has it been since you resolved your problem with alcohol/drugs?” in years and months. For our analyses we coded time since resolving an AOD problem in total years with decimal places.

Number of serious attempts at alcohol or other drug problem resolution

Participants were asked, “Approximately how many serious attempts did you make to resolve your alcohol/drug problem before you overcame it?”

Number of psychiatric diagnoses including substance use disorder

Participants were asked, “Which of the following substance use and/or mental health conditions have you ever been diagnosed with?” Diagnoses included, ‘alcohol use disorder’, ‘other drug use disorder’, ‘agoraphobia’, ‘anorexia’, ‘bipolar disorder (I or II)’, ‘bulimia’, ‘delusional disorder’, ‘dysthymic disorder’, ‘generalized anxiety disorder’, ‘major depressive disorder’, ‘OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder)’, ‘panic disorder’, ‘personality disorder’, ‘PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)’, ‘schizoaffective disorder’, ‘schizophrenia’, ‘social anxiety disorder’, ‘specific phobia’, or ‘other mental health diagnosis’. This question was adapted from the Mental and Emotional Health section of the Global Appraisal of Needs (GAIN) questionnaire which asks, “Has a doctor, nurse or counselor ever told you that you have a mental, emotional or psychological problem, or told you the name of a particular condition you have or had? What did they say?” (Dennis et al., 2008).

A measure of number of psychiatric diagnoses, including alcohol use other substance use disorders, was calculated by summing the total number of affirmative responses.

Treatment and mutual-help measures

Participants were asked to indicate whether they had ever received outpatient or inpatient AOD treatment in their lifetime. Endorsement of either treatment modality was coded as 1= yes, or 0= no for lifetime use of formal treatment. Participants were also also asked to indicate whether they had ever attended 12-step meetings regularly (at least once per week) with responses were coded as 1= yes, 0= no.

Self-esteem and happiness

Participants rated the extent to which they currently felt the statement “I have high self-esteem” is true on a Likert scale from 1= not very true to 5= very true (Robins et al., 2001). They also rated their current happiness from 1= completely unhappy to 5= completely happy (Meyers and Smith, 1995). The traditional 10-point scales for these items were modified to 5-point scales.

Quality of life / Functioning

Quality of life and daily functioning was assessed using the EUROHIS-QOL (Schmidt et al., 2005), an eight-item measure adapted from the World Health Organization Quality of Life - Brief Version. Item-level responses range from 1 to 5 (e.g., “How satisfied are you with your personal relationships?” 1= very dissatisfied to 5= very satisfied) with a total possible score ranging from 8–40. The EUROHIS-QOL is psychometrically sound with good to excellent predictive validity. Its internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α=.90).

Recovery capital

Recovery capital was measured using the 10-item Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10; Vilsaint et al., 2017). Item responses are on a Likert scale from 1 to 6 (e.g., “My living space has helped to drive my recovery journey” 1= strongly disagree to 6=strongly agree) with a total possible score ranging from 10–60. The measure has strong psychometric properties, including acceptable predictive validity, and excellent internal consistency (α= .90).

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was measured using the six-item Kessler 6 (Kessler et al., 2002). Item responses are on a Likert scale from 1= all of the time to 5=none of the time (e.g., “During the past 30 days, about how often did you feel… nervous; hopeless; restless or fidgety; so depressed that nothing could cheer you up; that everything was an effort; worthless?”) with total scores ranging from 6–30. The Kessler 6 is psychometrically sound with very good discriminative validity and excellent internal consistency (α= .89).

Analysis

Survey weights were used throughout the analyses to statistically account for any under-representation in the KnowledgePanel sample, as well as differential responding to the National Recovery Study screening question. As such, these findings can be seen as representing the US population.

Of the full sample of 2,002 participants, 219 did not respond to the question, “You said the following substances were a problem for you. Which was your primary substance or drug of choice?” While it is likely that many of those who did not respond to this question did so because they did not have a substance they felt was primary, it is also possible that some simply missed this question or skipped it because they did not want to answer it. Thus, these participants could be coded as 0 (totally abstinent from all AOD since AOD problem resolution), or 1 (current abstinence from all AOD but with at least some use of a substance since resolving an AOD problem) since these codes did not rely on primary substance. However, these participants could not be coded as 2 (current use of only a substance perceived to be secondary for the individual), 3 (current use of only the individual’s primary substance), or 4 (current use of both a secondary substance and the primary substance for that individual), which did rely on the participant identifying a primary substance. Of the 219 participants who did not endorse a primary substance, n= 118 fell into status categories 0 or 1 (i.e., abstinent) and were included in the analyses, while n= 101 endorsed current substance use and were omitted from the analyses.

Prevalence: To estimate prevalence of the different types of abstinent/substance use statuses, we used the SURVEYFREQ procedure is SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013) to characterize current substance use.

Substance use status and individual characteristics: Associations with current substance use status were explored using the SURVEYREG procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2016), with our ordinal substance use status variable as the dependent variable, and sex, race/ethnicity, primary substance, age of initiation of regular substance use, years since resolving an alcohol or other drug problem, number of serious attempts at resolving their AOD problem, number of psychiatric diagnoses, receipt of formal treatment for an AOD problem, and lifetime regular attendance at 12-step meetings, as explanatory (independent) variables. Age was excluded from all regression models due to high collinearity with years since AOD problem resolution giving rise to statistical anomalies (i.e., Simpson’s paradox; Eddie et al., 2021).

Substance use status and well-being: To investigate the relationship between measures of well-being and substance use status, we ran five separate unadjusted models using the SURVEYREG procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2016) with self-esteem, happiness, quality of life and functioning, recovery capital, psychological distress as dependent variables, and substance use status as the independent variable. The goal here was to understand the raw magnitude of the relationship between our indices of well-being, and substance use status. Finally, we re-ran these models controlling for select demographic variables (e.g., sex, race/ethnicity) and individual factors pertaining to substance use history and clinical severity (e.g., primary substance used, number of years since AOD problem resolution, number of psychiatric diagnoses). The rationale for testing these adjusted models was to help determine whether, independent of these other factors, substance use status remained associated with well-being. When choosing demographic and other individual factors to be included as covariates, only those which shared ≥ 1% of the variance with indices of well-being were selected as covariates. Variance accounted for was used as the cut-point for covariate selection rather than a p-value because the large sample size resulted in small, non-meaningful but statistically significant associations. Variance accounted for was determined using Pearson’s r (continuous measures), and ANOVA (multi-categorical measures; i.e., race/ethnicity, primary substance used), with participants who did not endorse a primary substance and endorsed current substance use (n= 101) omitted.

Based on this, for the fully adjusted models controlling for demographic and individual factors pertaining to substance use history and clinical severity, race/ethnicity, number of years since AOD problem resolution, and number of psychiatric diagnoses were included in all models. Sex was included only in the self-esteem and quality of life/functioning models, and primary substance used was included only in the psychological distress model.

Results

The sample’s characteristics are described in detail in Kelly et al. (2017). In short, the sample’s age distribution is as follows: 7.1% 18–24 yrs (emerging adulthood); 45.2% 25–49 yrs (young adults); 34.7% 50–64 yrs (mid-life stage adults); and 13.0% 65+ yrs (older adults). In terms of sex, 60% of participants identified as male and 40% female. Racially, 61.5% identified as White/non-Hispanic, 13.8% as Black/non-Hispanic, 5.8% as Other/non-Hispanic, 17.3% as Hispanic, and 1.7% as 2+ races/non-Hispanic. On average the sample reported 11.84 (SD= 10.93) years since resolving their AOD problem.

Participants who did not endorse having a primary substance (n= 219) were more likely to be Black (β= 0.82, p= .005; ref= White), have lower substance use risk status (β= −0.70, p< .0001), have fewer psychiatric diagnoses (β= −0.42, p= .006), and were less likely to have regularly attended 12-step groups (β= −0.49, p= .001). They were however not significantly different in terms of sex, age of initiation of regular substance use, years since resolving an AOD problem, number of serious attempts at AOD problem resolution, receipt of formal treatment, self-esteem, happiness, quality of life and functioning, psychological distress, or recovery capital (p> .05).

Weighted associations among substance use status, indices of well-being, and individual characteristics for the full sample (N= 2,002) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients among study variables

| % (n) / Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Substance use status (ordinal 0–4) 0= No AOD use since resolving AOD problem 1= No current AOD use 2= Secondary substance only 3= Primary substance only 4= Primary & secondary substance use |

0= 20.3% (n= 377) 1= 33.7% (n= 627) 2= 21.0% (n= 391) 3= 16.2% (n= 302) 4= 8.8% (n= 164) |

||||||||||||

| 2. Self-esteem | 3.46 (1.23) | −0.13**** | |||||||||||

| 3. Happiness | 3.72 (1.01) | −0.16**** | 0.62**** | ||||||||||

| 4. Quality of life / Functioning | 29.21 (6.61) | −0.14**** | 0.62**** | 0.76**** | |||||||||

| 5. Recovery capital | 46.68 (9.86) | −0.14**** | 0.50**** | 0.48**** | 0.58**** | ||||||||

| 6. Psychological distress | 10.87 (5.36) | 0.20**** | −0.55**** | −0.59**** | −0.61**** | −0.48**** | |||||||

|

7. Sex 0= Female 1= Male |

Female= 40.0% (n= 791) Male= 60.0% (n= 1188) |

0.02 | −0.10**** | −0.02 | −0.10**** | −0.02 | 0.09**** | ||||||

| 8. Age initiation of regular substance use | 20.20 (6.14) | −0.14**** | 0.02 | 0.04* | 0.05* | 0.03 | −0.06** | 0.04 | |||||

| 9. Years since AOD problem resolution | 11.84 (10.93) | −0.15**** | 0.23**** | 0.22**** | 0.22**** | 0.23**** | −0.28**** | −0.07** | −0.02 | ||||

| 10. Number of recovery attempts | 5.27 (13.27) | 0.01 | < −0.01 | < −0.01 | < 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.07** | −0.11**** | −0.09*** | |||

| 11. Psychiatric diagnoses | 0.94 (1.63) | 0.12**** | −0.28**** | −0.26**** | −0.26**** | −0.17**** | 0.40**** | 0.10**** | −0.10**** | −0.10**** | −0.11**** | ||

|

12. Formal treatment 0= No 1= Yes |

No= 75.0% (n= 1488) Yes= 24.8% (n= 491) |

−0.01 | −0.07** | −0.07** | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.25**** | |

|

13. Regular 12-step attendance 0= No 1= Yes |

No= 59.1% (n= 1169) Yes= 40.9% (n= 810) |

−0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.11**** | 0.19**** | 0.47**** |

Notes.

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001,

p< .0001.

AOD= alcohol and other drugs. SD= standard deviation (in parentheses)

1). Prevalence of different types of substance-using statuses among those having resolved an alcohol or other drug problem in the United States population

In terms of weighted substance use status frequencies, 378 participants (20.3%) endorsed being totally abstinent from all AOD since AOD problem resolution, 627 (33.7%) endorsed no current substance use with periods of AOD use since AOD problem resolution, 391 (21.0%) endorsed currently using a secondary substance, 302 (16.2%) endorsed currently using their primary substance, and 164 (8.8%) endorsed currently using both a secondary substance and their primary substance.

2). Associations between substance use status and individual characteristics

Individual factors associated with substance use status group are reported in Table 2. In the unadjusted models, age of initiation of regular substance use was negatively associated with substance use status such that the younger an individual was when initiating regular substance use, the greater the likelihood of them having a higher risk substance use status (i.e., using one’s primary substance or use of one’s primary substance in addition to a secondary substance), with years since AOD problem resolution accounting for 2% of the variance in substance use status.

Table 2.

Predictors of substance use status (dependent variable)

| Substance use status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

| F | R2 | F | R2 | |

| Model | 4.06**** | 0.06 | ||

| Sex | 0.46 | < 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| Female (β) | 0.05 | 0.01 | ||

| Male (β) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | 2.34^ | 0.01 | 1.22 | |

| White/non-Hispanic (β) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Black/non-Hispanic (β) | −0.30* | −0.27* | ||

| Other/non-Hispanic (β) | 0.13 | 0.14 | ||

| Hispanic (β) | 0.02 | −0.07 | ||

| 2+ races/non-Hispanic (β) | 0.18 | < −0.01 | ||

| Primary substance | 2.48^ | 0.01 | 1.34 | |

| Alcohol (β) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Cannabis (β) | 0.28^ | 0.23 | ||

| Opioids (β) | 0.32* | 0.19 | ||

| Other (β) | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||

| Age initiation of regular substance use | 19.09**** | 0.02 | 15.52**** | |

| Age initiation of regular substance use (β) | −0.03**** | −0.03**** | ||

| Years since AOD problem resolution | 25.33**** | 0.03 | 17.03**** | |

| Years since AOD problem resolution (β) | −0.02**** | −0.01**** | ||

| Number of serious attempts | 0.11 | < 0.01 | 0.00 | |

| Number of serious attempts (β) | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | ||

| Number psychiatric diagnoses | 14.48*** | 0.01 | 4.43* | |

| Number psychiatric diagnoses (β) | 0.09*** | 0.05* | ||

| Formal treatment (yes/no) | 0.13 | < 0.01 | 1.06 | |

| Yes (β) | −0.03 | −0.12 | ||

| No (β) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Regular 12-step attendance (yes/no) | 0.31 | < 0.01 | 0.41 | |

| Yes (β) | −0.05 | −0.06 | ||

| No (β) | Ref | Ref | ||

Notes.

p= .05,

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001,

p< .0001.

R2= Percent of variance accounted for. β= Unstandardized beta coefficient. AOD= alcohol and other drugs.

Additionally, number of years since AOD problem resolution was negatively associated with substance use status such that the more years since AOD problem resolution an individual reported, the greater the likelihood of them having a lower risk substance use status (i.e., no AOD use since AOD problem resolution or no current AOD use), with years since AOD problem resolution accounting for 3% of the variance in substance use status.

Finally, number of substance use disorder and other lifetime psychiatric diagnoses was positively associated with substance use status such that greater number of psychiatric diagnoses was associated with greater likelihood of higher risk substance use status, with number diagnoses accounting for 1% of the variance in substance use status.

These results were consistent with the findings for the adjusted models exploring the relationship between individual factors and substance use status (Table 2).

3). Associations between substance use status and current indices of well-being

The relationships between substance use status and indices of well-being are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationships between substance use status (dependent variable) and indices of well-being in unadjusted, and adjusted models

| Self-esteem (range= 0–5) | Happiness (range= 0–5) | Quality of life / Functioning (range= 8–40) | Recovery capital (range= 10–60) | Psychological distress (range= 6–30) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Model F | 17.22 **** | 18.98 **** | 22.65 **** | 18.12 **** | 15.00 **** | 16.31 **** | 16.87 **** | 15.55 **** | 35.23 **** | 20.35 **** |

| Substance use status (R2) | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| Substance use status (F) | 17.22 **** | 3.89 * | 22.65 **** | 9.70 ** | 15.00 **** | 5.20 * | 16.87 **** | 6.33 * | 35.23 **** | 14.46 *** |

| Substance use status (β) | −0.13**** | −0.06* | −0.12**** | −0.08** | −0.74**** | −0.41* | −1.13**** | −0.66* | 0.90**** | 0.54*** |

| Sex (F) | 5.55 * | 6.05 * | ||||||||

| Female (β) | −0.18* | −1.10* | ||||||||

| Male (β) | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity (F) | 6.58 **** | 1.39 | 2.56 * | 1.96 | 1.12 | |||||

| White/non-Hispanic (β) | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Black/non-Hispanic (β) | 0.53**** | 0.07 | 0.07 | 2.21^ | −0.16 | |||||

| Other/non-Hispanic (β) | 0.04 | −0.23 | −2.83* | −3.18 | 1.00 | |||||

| Hispanic (β) | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.72 | −0.73 | 0.80 | |||||

| 2+ races/non-Hispanic (β) | 0.17 | −0.46^ | −2.87* | −0.95 | 1.09 | |||||

| Primary substance (F) | 1.43 | |||||||||

| Alcohol (β) | Ref | |||||||||

| Cannabis (β) | 0.69 | |||||||||

| Opioids (β) | 1.26 | |||||||||

| Other (β) | 0.54 | |||||||||

| Years since AOD problem resolution (F) | 50.21 **** | 40.85 **** | 35.77 **** | 46.27 **** | 54.00 **** | |||||

| Years since AOD problem resolution (β) | 0.02**** | 0.02**** | 0.10**** | 0.17**** | −0.10**** | |||||

| Number psychiatric diagnoses (F) | 27.46 **** | 45.95 **** | 33.76 **** | 15.67 **** | 54.79 **** | |||||

| Number psychiatric diagnoses (β) | −0.16**** | −0.12**** | −0.86**** | −0.78**** | 1.14**** | |||||

Notes. Adjusted models include pertinent demographic variables in addition to substance use and psychiatric diagnosis related variables. Covariates were only included in models if their correlation with the respective index of well-being was r ≥ 0.1 (see Table 1). AOD= alcohol and other drugs. R2= Percent of variance accounted for. β= Unstandardized beta coefficient.

p= .05,

p< .05,

p< .01,

p< .001,

p< .0001

Self-esteem

In the unadjusted model, substance use risk status was negatively associated with self-esteem, such that having a lower risk substance use risk status was associated with greater self-esteem. Each level decrease in substance use risk status (scored 0–5) was associated with a 0.13 point increase in self-esteem (scored 0–5), with substance use risk status accounting for 2% of the variance in self-esteem.

Similarly, in the adjusted model (controlling for demographic factors + individual factors pertaining to substance use history and clinical severity), each level decrease in substance use risk status was associated with a 0.06 point increase in self-esteem, with substance use status accounting for <1% of the variance in self-esteem.

Happiness

In the unadjusted model, substance use status was negatively associated with happiness, such that having a lower risk substance use risk status was associated with greater happiness. Each level decrease in substance use risk status (scored 0–5) was associated with a 0.12 point increase in happiness (scored 0–5), with substance use risk status accounting for 2.50% of the variance in happiness.

Likewise, in the adjusted model, each level decrease in substance use risk status was associated with a 0.08 point increase in happiness, with substance use status accounting for 1% of the variance in the adjusted model.

Quality of life and functioning

In the unadjusted model, substance use status was negatively associated with quality of life and functioning, such that having a lower risk substance use risk status was associated with greater quality of life and functioning. Each level decrease in substance use risk status (scored 8–40) was associated with a 0.74 point increase in quality of life/functioning (scored 0–5), with substance use risk status accounting for 2% of the variance.

The result was similar for the adjusted model, with each level decrease in substance use risk status associated with a 0.41 point increase in quality of life and functioning, with substance use status accounting for 1% of the variance in the adjusted model.

Recovery capital

In the unadjusted model, substance use status was negatively associated with recovery capital, such that having a lower risk substance use risk status was associated with greater recovery capital. Each level decrease in substance use risk status (scored 0–5) was associated with a 1.13 point increase in recovery capital (scored 10–60), with substance use risk status accounting for 2% of the variance in recovery capital.

Similarly, in the adjusted model each level decrease in substance use risk status was associated with a 0.66 point increase in recovery capital, with substance use status accounting for <1% of the variance.

Psychological distress

In the unadjusted model, substance use status was positively associated with psychological distress, such that having a lower risk substance use risk status was associated with less psychological distress. Each level increase in substance use risk status (scored 0–5) was associated with a 0.90 point increase in psychological distress (scored 6–30), with substance use status accounting for 4% of the variance in psychological distress.

Likewise, in the adjusted model, each level increase in substance use risk status was associated with a 0.54 point increase in psychological distress, with substance use status accounting for 1% of the variance.

Sensitivity analysis

Given n= 101 were excluded from the regression analyses because they endorsed current substance use but did not respond to the question identifying participants’ primary substance, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to explore how omitting these participants affected results. All study models were rerun with these participants coded as ‘2’ (current use of a secondary substance). Findings were similar except that in the rerun models, the unadjusted association between substance use status and race was not statistically significant (p= .09), whereas before it was a trend (p= .05).

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of a nationally representative, US sample of individuals who resolved an AOD problem (Kelly et al., 2017), we found that almost half reported currently using either a secondary substance, their primary substance, or both a secondary and primary substance. In addition, consistent with previous findings (Donovan et al., 2005, Frischknecht et al., 2013, Laudet, 2011, Laudet and White, 2008, Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014, Erga et al., 2021), lower substance use risk based on an ordinal variable ranging from total AOD abstinence since problem resolution to current use of both primary and secondary substances was significantly associated with indices of well-being, over and above covariates including demographics, and clinical and other individual characteristics. Based on these findings, it appears that AOD abstinence is, for many, not a requisite for overcoming an AOD problem, however, abstinence is likely to lead to better functioning and well-being. Though this work is cross-sectional, these results speak to the value of harm reduction ‘gradations’ that occur with shifts from higher-, to lower-risk substance use and abstinence.

1). Prevalence of different types of substance-use statuses among those having resolved an alcohol or other drug problem in the United States population

These nationally representative findings indicate that of the 22.35 million American adults who have resolved an AOD problem (Kelly et al., 2017), 4.54 million (20.3%) have been abstinent since resolving their AOD problem, 7.53 million (33.7%) are currently abstinent but with some substance use since resolving their problem, 4.69 million (21.0%) are using a secondary substance, 3.62 million (16.2%) are using their primary substance, and 1.97 million (8.8%) are using both their primary and a secondary substance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graph showing percentage of the 22.35 million American adults who have resolved an alcohol or other drug (AOD) problem who have been abstinent since AOD problem resolution (20.3%), are currently abstinent but endorse some substance use since problem resolution (33.7%), are using a secondary substance (21.0%), are using their primary substance (16.2%), and are using both their primary and a secondary substance (8.8%)

Rates of abstinent recovery in the current study (54.0%) were greater than those among individuals in alcohol use disorder remission from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (54.0% vs. 28.9%; Fan et al., 2019). Of note, the National Recovery Study targeted those who identified as having resolved an AOD problem. Thus, abstinence rates may be higher among individuals with problem recognition versus those who meet criteria for SUD based on a structured clinical interview (e.g., First et al., 2015), but who may not recognize a problem. Indeed, 54.0% in the National Recovery Study also sought lifetime assistance for their substance use problem (Kelly et al., 2017) versus 19.8% among those with alcohol use disorder in the NESARC (Grant et al., 2015). National Recovery Study rates of abstinent recovery were lower, however, relative to the 88.0% with alcohol problems in the What is Recovery Study (Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014). Abstinence rates may be higher in samples where individuals identify as ‘in recovery’ (Kelly et al., 2018) as well as those recruited mostly through treatment-oriented organizations, as was the case in the What is Recovery Study (Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014).

The large proportion of those reporting resolving an AOD problem despite continuing with some degree of AOD use is perhaps surprising given the cultural embeddedness of abstinence as the sine qua non ingredient of successful AOD problem resolution. Like previous findings, results here suggest that some with less prior AOD involvement and related impairment are able—to a large extent—subjectively improve to the point that they perceive their AOD problem to be resolved without abstaining completely, and with a minority of these perhaps even using intensively (i.e., both primary and secondary substances). At the same time, as elaborated on further below, abstinence or low-level use was associated with better functioning and well-being.

2). Correlates of substance use status

The association between greater time since problem resolution and lower risk substance use status possibly reflects an aging out of substance use (Heyman, 2010), or some individuals struggling to moderate their use and eventually gravitating toward abstinence. ‘Ageing out’ itself may consist of substance use becoming less compatible with individuals’ lifestyles and developmental contexts as they grow older. It could also be that chronic use of AOD begins to culminate in greater incidence of medical problems (e.g., through toxicity-related impacts) and continued use may exacerbate these medical issues or interfere with effective treatment for them (Eddie et al., 2019), again, promoting motivation to abstain or reduce use.

The association between more reported lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and higher risk substance use status is consistent with studies showing a lower likelihood of abstinence post treatment and/or during remission among individuals with personality disorders (Dawson et al., 2005), individuals who have a history of attempted suicide, and those with a greater number of prior treatments for mental health problems (Soyka and Schmidt, 2009). It is possible that individuals with comorbidities have more psychosocial stress and challenges, taxing their coping resources, thus increasing the likelihood of ongoing substance use as a strategy to relieve mental health symptoms. While the harms of ongoing substance use for individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorder (Bruce et al., 2005, Bahorik et al., 2017) suggest abstinence may be the most optimal goal, it is clear many individuals with co-occurring disorders continue some form of substance use and are likely to benefit from additional clinical support and substance use harm reduction strategies.

With regards to our measure of number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses, which we used as a proxy of clinical severity, it should be noted that not all psychiatric conditions are equal in their typical severity (e.g., schizophrenia vs. generalized anxiety disorder), and within disorders there can be a great deal of variance in the number of symptoms endorsed and the severity of impairment they cause. Thus, having a single diagnosis may produce as much or more psychiatric distress and impairment as having numerous psychiatric diagnoses together. As a check that number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses was a reasonable measure reflecting clinical severity in our sample, we examined the correlation between number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and Kessler-6 scores capturing psychiatric distress. We found these measures to be positively associated (r= .40; p< .0001), suggesting number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses may be considered a reasonable proxy for clinical severity.

The lack of associations between each of formal treatment and regular mutual-help attendance with substance use status was unexpected. To check if we were perhaps missing an association between formal treatment (yes/no) and substance use status by using a dichotomous variable, we reran these models replacing the binary formal treatment measure with a continuous measure of total number of treatment episodes (calculated as number of detoxes + number inpatient stays + number outpatient treatment episodes), however findings were similar (i.e., still non-significant; p> .05).

Most treatment programs emphasize and link to 12-step mutual-help organizations (e.g., 60–75%; Roman and Johnson, 2004), which encourage an abstinence-based recovery approach. Also, in many empirically supported interventions for alcohol, stimulant, and opioid use disorders, protocols suggest clinicians recommend abstinence, at a minimum, from one’s primary substance (Crits-Christoph et al., 1999, Project MATCH Research Group, 1997, Weiss et al., 2011). Prior longitudinal work shows individuals who attend treatment over 1 year (Weisner et al., 2003), or mutual-help programs, as well as combined treatment plus mutual-help over 8 years (Timko et al., 2000) have greater rates of abstinence and drinking with few or no consequences (i.e., remission) than diagnostically similar comparison groups with no service utilization. In addition to these clinical, longitudinal studies, Subbaraman & Witbrodt (2014) also showed in a community-based sample of those who identified as ‘in recovery’ that histories of formal treatment-seeking and mutual-help attendance were uniquely associated with abstinence (versus current substance use). It is not readily determined from these data why treatment and mutual-help history were unrelated to substance use status in the current study. It is possible that these experiences are unrelated to substance use status in the current study because the nationally representative sample of individuals reporting problem resolution used here captured a broader, more heterogenous set of recovery experiences than more focused clinical and recovery-identified samples. It is also possible that individuals who were more engaged with 12-step mutual-help organizations (e.g., have a sponsor, work steps, socialize with other members, etc.) would have greater rates of abstinence and other low-risk use, though this cannot be determined from the data.

3). Associations between substance use status and current indices of well-being

There were associations found between lower risk substance use and greater self-esteem, happiness, quality of life and functioning, recovery capital, and lower psychological distress in both the unadjusted and adjusted models (Table 3). Of note, in these analyses, greater substance use risk status was associated with greater psychological distress, even when controlling for lifetime psychiatric disorders – a variable itself positively correlated with greater distress. These findings are similar to findings in prior work (Donovan et al., 2005, Frischknecht et al., 2013, Laudet, 2011). For instance, in the What is Recovery Study, AOD abstinence (versus any substance use) was strongly and uniquely related to greater quality of life (Subbaraman and Witbrodt, 2014). Similar correlations have also been observed for recovery capital (Laudet and White, 2008, Sinclair et al., 2021), quality of life (Brezing et al., 2018), and psychological distress (Erga et al., 2021). Our study replicates and extends these findings to the broader population of individuals who have resolved an AOD problem, regardless of treatment seeking status, primary substance used, and recovery duration/identity.

In context of existing research, then, emerging patterns suggest that, 1) some individuals who report resolving an AOD problem may achieve gains in functioning and well-being while continuing some use of AOD (e.g., Witkiewitz and Tucker, 2020), and at the same time, 2) abstinence, on average, is independently associated with greater levels of functioning well-being. To the extent that a perceived requirement to have a goal of complete abstinence is a barrier for some to enter treatment in the first place, a key clinical implication here is that communicating that some (e.g., those with lower AOD involvement and impairment) may be able to resolve an AOD problem without necessarily needing to abstain completely may help such individuals access helpful resources sooner.

Limitations

The study’s findings should be considered in light of the following limitations. 1) This is a cross-sectional study, and as such, causality between associated variables cannot be known. At the same time, the present findings generate some potential avenues for future longitudinal research that could examine moderators and mediators of the relationship between substance use and psychosocial well-being over time. 2) By design, this nationally representative study surveyed individuals self-identifying as having resolved an AOD problem regardless of formal SUD diagnosis. An inherent limitation of this approach is that the specific parameters of what constitutes an AOD problem and overcoming an AOD problem are determined subjectively by the participants. Relatedly, the psychometric properties of the National Recovery Study screening question have not been examined, including validity (e.g., convergence with similar constructs such as remission from DSM-5 substance use disorder) and reliability (e.g., do individuals respond consistently to this screening item). 3) The subjective nature of ‘problem’ and ‘problem resolution’ in the National Recovery Study’s initial survey question, “Did you used to have a problem with drugs or alcohol, but no longer do?” may have influenced estimates in unknown ways but was used in this way for consistency with prior regional-level surveys. 4) The response rate to the initial survey question was 63%. Though this response rate is similar to other nationally representative surveys, the GfK KnowledgePanel represents a subset of individuals who agreed to participate in surveys and acquiring data from non-respondents might have provided different results. At the same time, by using complex samples analyses that integrate survey weights, our results reflect an unbiased estimate of the population of US adults who self-reported having resolved an AOD problem. 5) To assess treatment effects, we asked participants whether they received inpatient or outpatient treatment for their AOD problem, and whether they ever regularly attended 12-step meetings. These measures, however, don’t capture treatment duration and intensity, which will have varied from participant to participant. 6) Number of serious attempts at AOD problem resolution was assessed using the question, “Approximately how many serious attempts did you make to resolve your alcohol/drug problem before you overcame it?” For some, especially those with unassisted AOD problem resolution, resolution may have been a progressive process rather than there being a number of distinct attempts. 7) Number of psychiatric diagnoses was assessed using a question adapted from the widely used GAIN questionnaire. We asked, “Which of the following substance use and/or mental health conditions have you ever been diagnosed with?”. It is likely that some participants were not told their diagnoses by their healthcare providers, and others did not remember the diagnostic label/s. It is also possible that some may have endorsed diagnoses based on their personal experience rather than clinical assessment. Additionally, responses to this item are an artefact of receiving healthcare services. Individuals may have met criteria for a psychiatric disorder, but if they never interacted with a healthcare provider, they would not have been ‘diagnosed’ per se. 8) A portion of the sample (10.9%) did not endorse a primary substance, requiring n= 101 to be omitted from the regression analyses. While the post hoc sensitivity analyses showed that omitting these participants did not have a major impact on the results, this nevertheless may have influenced results in subtle ways. 9) This paper is limited in terms of assessing social influences on recovery pathways among persons who endorse resolving an AOD problem; there is a need for further research in this area.

Conclusions

The present study highlights the prevalence of different substance use patterns, ranging from total AOD abstinence to ongoing use of both primary and secondary substances, and its relationship to indices of functioning and well-being among US adults who endorse having resolved an AOD problem. Approximately half of Americans who endorse having resolved an AOD problem are abstinent from AOD (54%), while the remainder endorse some form of continued substance use. Later age of initiation of regular substance use, greater number of years since AOD problem resolution, and fewer number of lifetime psychiatric diagnoses were found to be independently associated with lower risk current substance use status. Additionally, lower risk substance use status was independently associated with greater self-esteem, happiness, quality of life and functioning, recovery capital, and lower psychological distress after controlling for demographic characteristics as well as substance use history and clinical severity factors. Given the cross-sectional nature of the current study, future prospective studies should examine moderators and mediators of the relationship between substance use and psychosocial well-being over time in order to better understand who is able to successfully sustain these different substance use statuses and the mechanisms through which they may do so.

Funding Sources:

The National Recovery Study was funded by the Massachusetts General Hospital Recovery Research Institute. The authors of this publication were supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awards F32AA025251, K23AA027577-01A1, K23AA025707-04, K24AA022136, L30AA026135, L30AA026135-02, and National Institute on Drug Abuse award F32DA047741.

References

- AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5, Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- BAHORIK AL, LEIBOWITZ A, STERLING SA, TRAVIS A, WEISNER C & SATRE DD 2017. Patterns of marijuana use among psychiatry patients with depression and its impact on recovery. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 168–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BATTAGLIA MP, IZRAEL D, HOAGLIN DC & FRANKEL MR 2009. Practical considerations in raking survey data. Survey Practice, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- BREZING CA, CHOI CJ, PAVLICOVA M, BROOKS D, MAHONY AL, MARIANI JJ & LEVIN FR 2018. Abstinence and reduced frequency of use are associated with improvements in quality of life among treatment-seekers with cannabis use disorder. American Journal of Addiction, 27, 101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUCE SE, YONKERS KA, OTTO MW, EISEN JL, WEISBERG RB, PAGANO M, SHEA MT & KELLER MB 2005. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CENTER FOR BEHAVIORAL HEALTH STATISTICS AND QUALITY 2016. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Methodological Summary and Definitions. Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION. 2013. Unweighted response rates for The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2012. [Online]. Hyattsville, MD: CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/response_rates_cps.htm [Accessed March 25, 2018]. [Google Scholar]

- CRITS-CHRISTOPH P, SIQUELAND L, BLAINE J, FRANK A, LUBORSKY L, ONKEN LS, MUENZ LR, THASE ME, WEISS RD, GASTFRIEND DR, WOODY GE, BARBER JP, BUTLER SF, DALEY D, SALLOUM I, BISHOP S, NAJAVITS LM, LIS J, MERCER D, GRIFFIN ML, MORAS K & BECK AT 1999. Psychosocial treatments for cocaine dependence: National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON DA, GOLDSTEIN RB & GRANT BF 2007. Rates and correlates of relapse among individuals in remission from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: a 3-year follow-up. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 2036–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON DA, GRANT BF, STINSON FS, CHOU PS, HUANG B & RUAN WJ 2005. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002. Addiction, 100, 281–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEGENHARDT L, CHARLSON F, FERRARI A, SANTOMAURO D, ERSKINE H, MANTILLA-HERRARA A, WHITEFORD H, LEUNG J, NAGHAVI M, & GRISWOLD M 2018. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry, 5, 987–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DENNIS DL, WHITE M, TITUS JC & UNSICKER J 2008. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs: Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. Bloomington, IL: Chestnut Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- DONOVAN D, MATTSON ME, CISLER RA, LONGABAUGH R & ZWEBEN A 2005. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement (s15), 119–39; discussion 92–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDDIE D, GREENE MC, WHITE WL & KELLY JF 2019. Medical burden of disease among individuals in recovery from alcohol and drug problems in the United States: Findings from the National Recovery Survey. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 13, 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDDIE D, WHITE WL, VILSAINT CL, BERGMAN BG & KELLY JF 2021. Reasons to be cheerful: Personal, civic, and economic achievements after resolving an alcohol or drug problem in the United States population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 35, 402–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERGA AH, HØNSI A, ANDA-ÅGOTNES LG, NESVÅG S, HESSE M & HAGEN E 2021. Trajectories of psychological distress during recovery from polysubstance use disorder. Addiction Research & Theory, 29, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- FAN AZ, CHOU SP, ZHANG H, JUNG J & GRANT BF 2019. Prevalence and correlates of past-year recovery from DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 43, 2406–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FIRST MB, WILLIAMS JBW, KARG RS & SPITZER RL 2015. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version, Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- FRISCHKNECHT U, SABO T & MANN K 2013. Improved drinking behaviour improves quality of life: a follow-up in alcohol-dependent subjects 7 years after treatment. Alcohol & Alcoholism, 48, 579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLASGOW RE, LICHTENSTEIN E & MARCUS AC 2003. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANT BF, GOLDSTEIN RB, SAHA TD, CHOU SP, JUNG J, ZHANG H, PICKERING RP, RUAN WJ, SMITH SM & HUANG B 2015. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72, 757–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLY JF, ABRY AW, MILLIGAN CM, BERGMAN BG & HOEPPNER BB 2018. On being “in recovery”: A national study of prevalence and correlates of adopting or not adopting a recovery identity among individuals resolving drug and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32, 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLY JF, BERGMAN B, HOEPPNER BB, VILSAINT CL & WHITE WL 2017. Prevalence and pathways of recovery from drug and alcohol problems in the United States population: Implications for practice, research, and policy. Drug & Alcohol Dependence, 181, 162–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KESSLER RC, ANDREWS G, COLPE LJ, HIRIPI E, MROCZEK DK, NORMAND SL, WALTERS EE & ZASLAVSKY AM 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32, 959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUDET AB 2011. The case for considering quality of life in addiction research and clinical practice. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 6, 44–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAUDET AB & WHITE WL 2008. Recovery capital as prospective predictor of sustained recovery, life satisfaction, and stress among former poly-substance users. Substance Use and Misuse, 43, 27–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYERS RJ & SMITH JE 1995. Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The community reinforcement approach, New York, NY, USA, Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- PATEL V, CHISHOLM D, PARIKH R, CHARLSON FJ, DEGENHARDT L, DUA T, FERRARI AJ, HYMAN S, LAXMINARAYAN R, LEVIN C, LUND C, MEDINA MORA ME, PETERSEN I, SCOTT J, SHIDHAYE R, VIJAYAKUMAR L, THORNICROFT G, & WHITEFORD H 2016. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet, 387, 1672–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROJECT MATCH RESEARCH GROUP 1997. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58, 7–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PROJECT MATCH RESEARCH GROUP 1998. Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Treatment main effects and matching effects on drinking during treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 59, 631–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBINS RW, HENDIN HM & TRZESNIEWSKI KH 2001. Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- ROMAN PM & JOHNSON JA 2004. National treatment center study summary report: Private treatment centers. Athens, GA: Institute for Behavioral Research, University of Georgia. [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA 2013. Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- SAS INSTITUTE 2013. SAS/STAT® 13.1 User’s Guide - The SURVEYFREQ Procedure, Cary, NC, SAS institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- SAS INSTITUTE 2016. SAS/STAT® 14.2User’sGuide The SURVEYREG Procedure, Cary, NC, SAS institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- SCHMIDT S, MÜHLAN H & POWER M 2005. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. The European Journal of Public Health, 16, 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINCLAIR DL, SUSSMAN S, DE SCHRYVER M, SAMYN C, ADAMS S, FLORENCE M, SAVAHL S, & VANDERPLASSCHEN W 2021. Substitute Behaviors following Residential Substance Use Treatment in the Western Cape, South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOYKA M & SCHMIDT P 2009. Outpatient alcoholism treatment--24-month outcome and predictors of outcome. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, & Policy, 4, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEA JN, YAKOVENKO I & HODGINS DC 2015. Recovery from cannabis use disorders: Abstinence versus moderation and treatment-assisted recovery versus natural recovery. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 522–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUBBARAMAN MS & WITBRODT J 2014. Differences between abstinent and non-abstinent individuals in recovery from alcohol use disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 1730–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIMKO C, MOOS RH, FINNEY JW & LESAR MD 2000. Long-term outcomes of alcohol use disorders: comparing untreated individuals with those in alcoholics anonymous and formal treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61, 529–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VILSAINT CL, KELLY JF, BERGMAN BG, GROSHKOVA T, BEST D & WHITE WL 2017. Development and validation of a Brief Assessment of Recovery Capital (BARC-10) for alcohol and drug use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISNER C, MATZGER H & KASKUTAS LA 2003. How important is treatment? One-year outcomes of treated and untreated alcohol-dependent individuals. Addiction, 98, 901–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISS RD, POTTER JS, FIELLIN DA, BYRNE M, CONNERY HS, DICKINSON W, GARDIN J, GRIFFIN ML, GOUREVITCH MN, HALLER DL, HASSON AL, HUANG Z, JACOBS P, KOSINSKI AS, LINDBLAD R, MCCANCE-KATZ EF, PROVOST SE, SELZER J, SOMOZA EC, SONNE SC & LING W 2011. Adjunctive counseling during brief and extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for prescription opioid dependence: a 2-phase randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 1238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE WL 2007. Addiction recovery: Its definition and conceptual boundaries. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33, 229–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITE WL & KURTZ E 2006. The varieties of recovery experience. International Journal of Self Help and Self Care, 3, 21–61. [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K & TUCKER JA 2020. Abstinence not required: Expanding the definition of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism, Clinical & Experimental Research, 44, 36–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K, WILSON AD, PEARSON MR, MONTES KS, KIROUAC M, ROOS CR, HALLGREN KA & MAISTO SA 2019. Profiles of recovery from alcohol use disorder at three years following treatment: Can the definition of recovery be extended to include high functioning heavy drinkers? Addiction, 114, 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WITKIEWITZ K, WILSON AD, ROOS CR, SWAN JE, VOTAW VR, STEIN ER, PEARSON MR, EDWARDS KA, TONIGAN JS, HALLGREN KA, MONTES KS, MAISTO SA & TUCKER JA 2020. Can Individuals With Alcohol Use Disorder Sustain Non-abstinent Recovery? Non-abstinent Outcomes 10 Years After Alcohol Use Disorder Treatment. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 15, 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]