Abstract

Background & Aims:

Primary liver tumors contain distinct subtypes. A subset of iCCAs can arise from cell fate reprogramming of mature hepatocytes in mouse models. However, the underpinning of cell fate plasticity during hepatocarcinogenesis is still poorly understood, hampering therapeutic development to treat HCC and iCCA. As YAP activation induces liver tumor formation and cell fate plasticity, we investigated the role of Sox9, a transcription factor downstream of Yap activation and expressed in biliary epithelial cells (BECs), in Yap-induced cell fate plasticity during hepatocarcinogenesis.

Methods:

To evaluate the function of Sox9 in YAP-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo, we performed inducible hepatocyte-specific YAP activation with simultaneous Sox9 removal in several mouse genetic models. Cell fate reprogramming was determined by lineage tracing and immunohistochemistry. The molecular mechanism underlying Yap and Sox9 function in hepatocyte plasticity was investigated by transcription and transcriptomic analyses of mouse and human liver tumors.

Results:

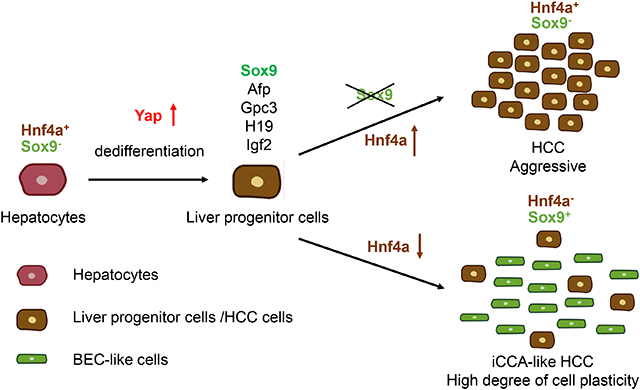

Sox9, a marker of liver progenitor cells (LPCs) and BECs, is differentially required in YAP-induced stepwise hepatocyte programming. While Sox9 has limited function in hepatocyte dedifferentiation to LPCs, it is required for BEC differentiation from LPCs. YAP activation in Sox9-deficient hepatocytes resulted in more aggressive HCC with enhanced Yap activity at the expense of iCCA-like tumors. Furthermore, we showed that 20% of primary human liver tumors were associated with a YAP activation signature, and tumor plasticity is highly correlated with YAP activation and SOX9 expression.

Conclusion:

Our data demonstrated that Yap-Sox9 signaling determines hepatocyte plasticity and tumor heterogeneity in hepatocarcinogenesis in both mouse and human liver tumors. We identified Sox9 as a critical transcription factor required for Yap-induced hepatocyte cell fate reprogramming during hepatocarcinogenesis.

Keywords: Hippo signaling, Yap, Sox9, HCC, iCCA, BEC, LPC, cell fate plasticity, reprogramming

Graphical Abstract

Lay summary

Sox9, a marker of liver progenitor cells and bile duct lining cells, is a downstream target of YAP protein activation. Here we found that YAP activation in hepatocytes leads to a transition from mature hepatocytes to first liver progenitor cells and then the formation of the bile duct lining cells and Sox9 is required in the second step during mouse hepatocarcinogenesis. We also found that human YAP and SOX9 may play similar roles in liver cancers.

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the third common cause of cancer mortalities globally and a significant public health challenge[1]. These tumors contain heterogeneous subtypes, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), combined hepatocellular carcinoma-intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (cHCC-iCCA), and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)[2]. HCC and iCCA are major types of primary liver tumors, considered independent tumors that originate from hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells (BECs), respectively, with distinct cellular, molecular and clinical features. However, recent studies have suggested that a subset of iCCAs can arise directly from cell fate reprogramming of mature hepatocytes[3, 4] and HCC and iCCA share overlapping risk factors and pathways of oncogenesis. Therefore, cell plasticity, a common feature of tumor progression, metastasis, recurrence (reviewed in[5]), contributes to iCCA and HCC formation. Understanding how liver tumor heterogeneity is controlled will provide critical insights into tumor-specific therapies.

Central to the Hippo signaling pathway is a kinase cascade of Mst1/2 and Lats1/2 that turns off the activity of downstream transcription coactivators Yap/Taz by phosphorylating them, causing Yap/Taz cytoplasmic retention and proteasomal degradation (reviewed in[6]). Genetically inactivating Hippo signaling pathway or activating Yap in mouse liver promotes HCC and hepatocyte-derived iCCA-like tumor formation accompanied by a large expansion of Sox9+ BEC-like cells [6-10]. Given the importance of Yap activation in hepatocyte reprogramming and liver tumor formation, it is essential to identify functional targets that act downstream of YAP. Sox9, a marker of BECs and liver progenitor cells (LPCs), is a transcription factor regulated by Yap/Taz in the liver[10]. However, the in vivo function of Sox9 in hepatocyte reprogramming and hepatocarcinogenesis is still unclear. In this study, we investigated the hepatocyte-specific function of Sox9 in YAP-induced hepatocyte cell fate plasticity during mouse hepatocarcinogenesis. Our data show that in both mouse and human liver tumors with high YAP activities, the intrinsic difference in Sox9 expression between hepatocyte-derived iCCA-like tumor and HCC determines their tumor types.

Materials and Methods

Mice:

Animal protocols and procedures were approved by the Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in pathogen-free facility in a 12h light/dark cycle. Both male and female mice were used for experiments. Whenever possible, littermates with negative genotypes were used as controls. Otherwise, C57BL/6J mice were used as control. The Source of mice was in the supplementary CTAT Table.

Statistical Analysis:

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data quantification and analyses were plotted using Prism 8. The number of biological replicates was specified in the figure legends. P-value was determined by two-tailed Student’s t-test in comparison of two sample groups and by 1-way ANOVA with Sidak's test in comparison of more than two sample groups, and presented as follows: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Data Availability:

RNA-seq data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE146589). ATAC-seq data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of NIH (PRJNA 732288).

Other materials and methods are shown in the supplementary methods and supplementary CTAT table.

Result

Hepatocyte plasticity induced by hepatic Yaps127A expression requires Sox9 during hepatocarcinogenesis

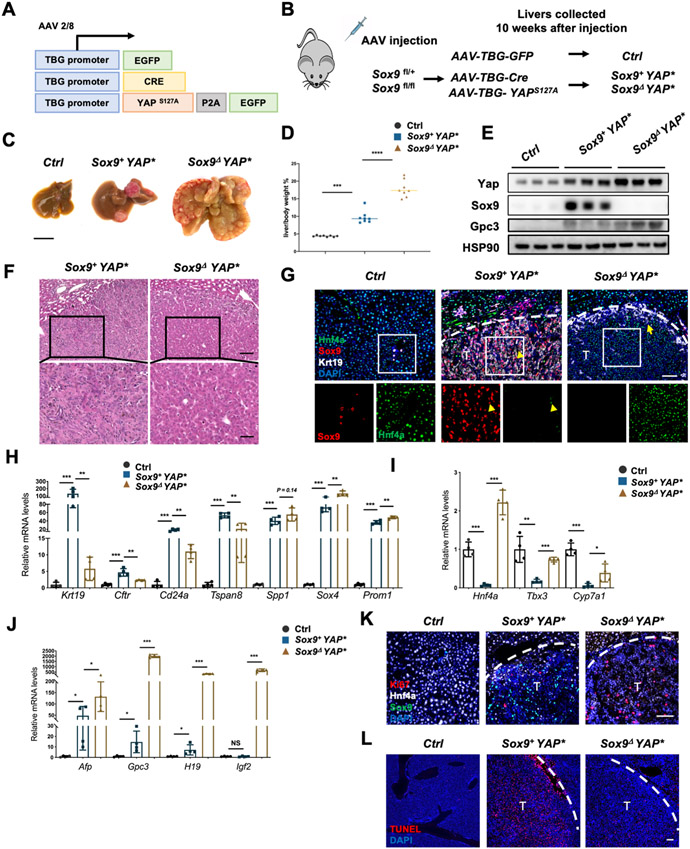

We first asked whether Sox9 is required for Yap-induced oncogenic hepatocyte reprogramming. YAPS127A, a constitutively activated form of YAP[11]was expressed with EGFP under the hepatocyte-specific Thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) promoter[10] via an Adeno-associated virus 8 (AAV8) expression vector (Fig. 1A, B). Hepatocyte-specific Sox9 removal (Sox9Δ) was achieved in the Sox9fl/fl mice by AAV-TBG-Cre injection (Fig. 1B). Severe hepatomegaly and liver tumor nodules were detected 10 weeks after coinjection of AAV-TBG-Cre and AAV-TBG-YAPS127A to the Sox9fl/+ (Sox9+YAP*) and Sox9fl/fl (Sox9ΔYAP*) mice (Fig. 1C, D). Hepatomegaly was obvious 5 weeks after AAV injection, and tumors appeared 7 weeks after AAV injection. Co-injection of the AAVs to the Sox9fl/+or Sox9+/+ mice did not cause any difference in liver size or tumor nodules. We therefore used the Sox9fl/+ and Sox9fl/fl littermates in the experiments. Surprisingly, the Sox9ΔYAP* mice showed more severe hepatomegaly with increased number of tumor nodules compared to the Sox9+YAP* mice (Fig. 1C, D). Efficient YAPS127A overexpression and Sox9 deletion were confirmed by Western blotting and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses of Sox9, YAP, and YAP target gene expression (Fig. 1E, Fig. S1A). Consistent with our previous findings[7, 12], tumors in the Sox9+YAP* mice showed severe fibrous stromal reaction and inflammation, and the tumor cells were pleomorphic, suggesting that these tumors are poorly differentiated carcinoma (Fig. 1F, Fig. S1B). However, the Sox9Δ tumors exhibited a markedly higher nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, which is commonly observed in malignant HCC (Fig. 1F). Most of the Sox9+YAP* tumors were Krt19+Sox9+Hnf4a− (Fig. 1G, Fig. S1C, D), with upregulated expression of BEC lineage genes such as Krt19, Cftr, Cd24a, Tspan8 (Fig. 1 H)[13] and diminished expression of hepatocyte genes such as Hnf4a, Tbx3, Cyp7a1 and glutamine synthetase (Fig. 1I, S1E). However, the Sox9ΔYAPS127A tumors were mostly Krt19− Hnf4a+ with high levels of fetal hepatocyte gene expression (Fig. 1J). Intriguingly, some genes expressed in both BEC and LPC, such as Spp1, Prom1, and Sox4 [13] were not down-regulated by Sox9 deletion(Fig. 1H).

Figure 1. Sox9 determines the cellular composition in the YAP-induced liver tumors.

(A) Schematics of AAV constructs. (B) Schematic diagram of the experimental procedure. (C) Representative liver images in the indicated mice. (D) Liver/body weight ratios of the indicated mice (n=8). (E) Western blotting analysis. (F) Representative images of H&E staining. (G) Representative immunofluorescent images as indicated. Arrowhead: Sox9+Hnf4a+ cells. Arrow: Sox9−, Krt19+ cells. (H-J) qRT-PCR analysis of BEC marker genes (H), hepatocyte marker genes (I) and HCC genes (J) (n=4). (K-L) Representative images of Ki67 (K) and TUNEL (L) staining. Dotted lines demarcate tumor boundary, T: tumor. Scale bars: 1cm (C), upper panel:100μm; lower panel: 50μm (F), 100pm (G, K, L).

In the Sox9+YAP* tumor, most of the proliferative Ki67+ cells were HNF4a+ hepatocytes, not the Sox9+ BEC-like cells (Fig. S1F). In the faster growing Sox9ΔYAP* tumor, cell proliferation was further increased, but cell death (TUNEL assay) was decreased with highly upregulated expression of pro-proliferation genes (Fig. 1K, L, Fig. S1F-I). Moreover, expression of HCC marker genes[14] was upregulated to higher levels in the Sox9ΔYAP*tumor (Fig. 1E, J, Fig. S1E). However, the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were further increased in the Sox9ΔYAP* tumor, likely due to increased cell death in the non-tumor region (Fig. S1 J, K).

Similar phenotypes were observed in another mouse model with endogenous Yap activation. We removed Mst1/2 and Sox9 in hepatocytes by AAV-TBG-Cre (Fig. S2A), and hepatocytes were reprogrammed to BEC-like cells in the MstΔ;Sox9+, not the MstΔ;Sox9Δ liver. Again, the MstΔ;Sox9Δ liver had bigger tumors than the MstΔ;Sox9+ one, with recovered Hnf4a expression (Fig. S2B, C). Hepatomegaly was obvious 4 weeks after AAV injection, but tumors appeared 12 weeks after AAV injection. These data indicate that the Sox9+ and Sox9Δ tumors induced by Yap activation were distinct, and the latter maintained hepatic gene expression, with higher levels of HCC gene expression and more aggressive malignant growth. These results suggest that Sox9 is required for hepatocyte transformation to BEC-like cells during YAP induced hepatocarcinogenesis.

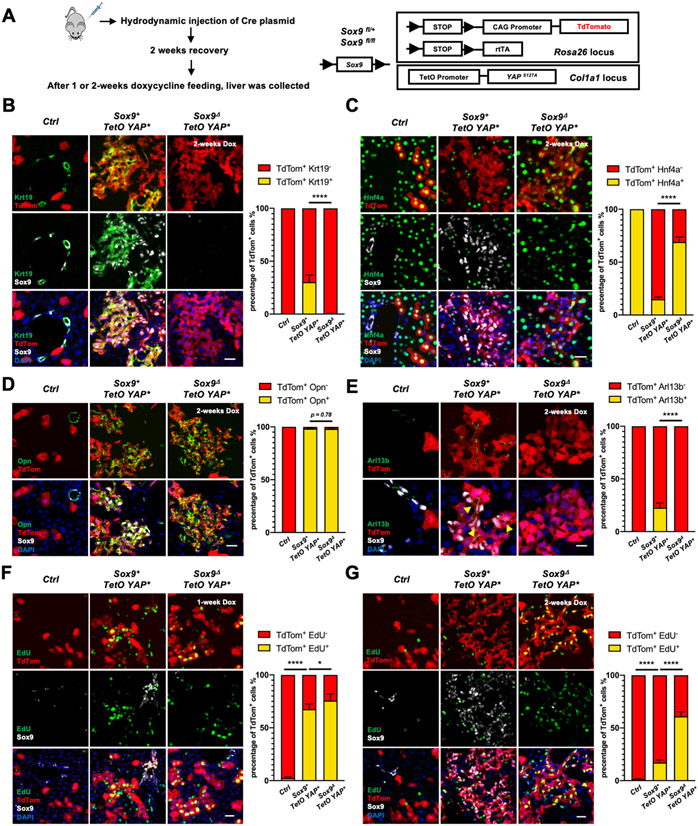

Sox9 is cell-autonomously required for Yap-induced oncogenic hepatocyte reprogramming

To rigorously determine the role of Sox9 in YAPS127A induced tumor cell plasticity during hepatocarcinogenesis, we lineage traced the YAPS127A expressing cells with Cre-induced tdTomato (tdTom) expression (Fig. 2). More tdTom+ cells were found in Sox9− clones than Sox9+ clones as early as one week after Doxycycline (Dox)-induced Cre expression (Fig. S3A, B). As shown previously[10], YAPS127A progressively induced hepatocyte reprogramming to BEC-like cells (Fig. 2B-D, Fig. S3C-F). Loss of Sox9 abolished Epcam and Krt19 expression, while largely maintained Hnf4a expression in the tdTom+ cells (Fig. 2B-D, Fig. S3C-F). Spp1 expression was induced in both Sox9+ and Sox9Δ cells 1-weeks after YAP activation. The ratio of Spp1+ cells in tdTom+ cells was lower in the Sox9Δ, TetO-YAP* liver than the Sox9+; TetO-YAP* liver (Fig. S3G). 2-weeks after YAP activation, however, Spp1 was expressed in almost all tdTom+ cells regardless of Sox9 presence (Fig. 2D), suggesting that Spp1 expression is mainly regulated by Yap, while Sox9 may also promote its expression.

Figure 2. Lineage tracing of YAPS127A expressing hepatocytes.

(A) Schematic diagram of experimental procedures. (B-E) Representative immunofluorescent images as indicated 2-weeks after Dox feeding. (F, G) Representative images of EdU labeling, with Sox9 and tdTom_immunofluorescent staining one-week (F) and 2-weeks (G) after Dox feeding. Quantification is shown on the right side (n=6 in each group). Scale bars: 50μm (B-D, F, G); 25μm (E).

Hepatocytes and BECs have distinct cellular features apart from distinct gene expression. Primary cilia are absent in hepatocytes but present in BEC cells[15]. Indeed, Arl13b, a primary cilium marker[15], was only detected in tdTom+ cells in the Sox9+; TetO-YAP*, but not the Sox9Δ; TetO-YAP* liver (Fig. 2E). As primary cilia form in cells that stopped dividing[15], most Sox9+ cells were indeed not EdU+ after Dox feeding (Fig. 2F, G, Fig. S3H), indicating that Sox9+tdTom+ cells were less proliferative than the Sox9ΔtdTom+ cells. These data indicate that Yap-induced hepatocyte reprogramming involves stepwise changes, in which Sox9 expression is an early event required for later BEC differentiation.

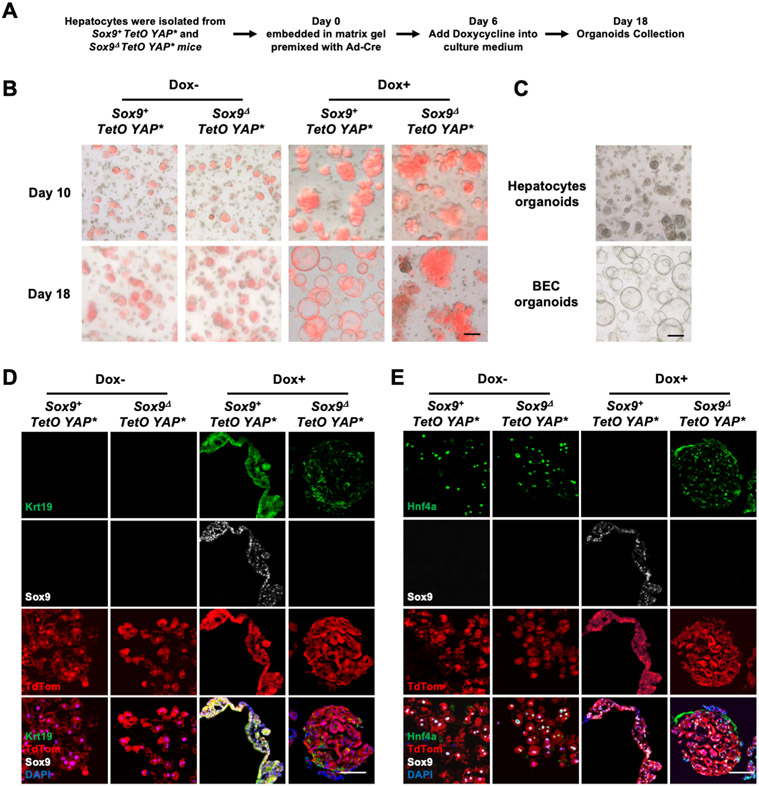

We then investigated the role of Sox9 in Yap induced hepatocyte reprogramming using liver organoids[16]. In the organoids derived from the Sox9+; TetO-YAP* or Sox9Δ; TetO-YAP* hepatocytes, tdTom and rtTA expression, as well as Sox9 deletion, were induced simultaneously by Adenovirus-Cre (Ad-Cre) infection (Fig. 3A). Sox9 deletion did not change the efficiency of organoid formation (Fig. S4A). Compared with BEC organoids, YAP activity was much lower in hepatocyte organoids (Fig. S4B). Without Dox, the Sox9+ and Sox9Δ organoids showed identical morphology of wild-type hepatocyte organoids (Fig. 3B, C)[16]. After Dox-induced YAP activation, the Sox9+ hepatocyte organoids showed typical morphology of BEC organoids[16] (Fig. 3B, C) and expressed BEC markers (Fig.3D, Fig. S4C-E). However, the Sox9Δ organoids retained hepatocyte organoid morphology, expressed hepatocyte markers, and were bigger in size due to YAP activation (Fig. 3E, Fig. S4C-E). Cell fate change in the organoids appears stepwise as the Sox9+ organoids largely retained the morphology of hepatocytes organoids after a short time DOX treatment (Day 10) (Fig. 3B, C). These data further demonstrate that Sox9 is required cell-autonomously for Yap-induced hepatocyte cell fate plasticity.

Figure 3. Sox9 is required for Yap-induced cell fate change.

(A) Schematic diagram of organoid cultures. (B) Merged images of brightfield and tdTom of the hepatocyte-organoids. (C) Brightfield images of wild-type hepatocyte and BEC organoids. (D-E) Representative immunofluorescent images as indicated. Scale bars: 100μm (B and C); 50μm (D and E).

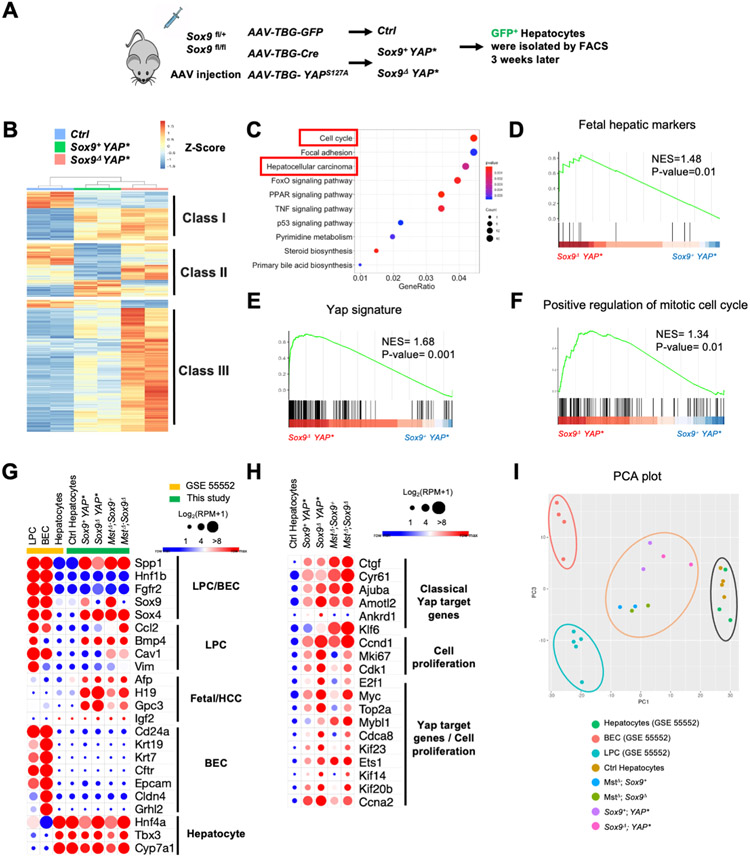

Loss of Sox9 in YAP-induced liver tumors blocked BEC-like differentiation from dedifferentiated hepatocytes

We performed RNA-seq analyses to identify the transcriptomic changes caused by Sox9 deletion in hepatocytes with Yap activation. GFP+ wild type and YAPS127A expressing hepatocytes, and tdTom+ wild type and MstΔ hepatocytes were isolated from the mouse liver by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (Fig. 4A, Fig. S5A, B). Loss of Sox9 resulted in three classes of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by Yap activation (Fig. 4B, Fig. S5C). Class II and III were likely differentially regulated by Sox9 downstream of Yap activation, while Class I may be independent of Sox9 (Fig. 4B, Fig. S5C). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis showed that Class II and III DEGs genes were enriched for cell cycle regulation and HCC formation (Fig. 4C, Fig. S5D). The fetal hepatic signature, Yap signature genes, and genes positively regulating mitotic cell cycle were statistically enriched in the Sox9ΔYAP* hepatocytes (Fig. 4D-F, Fig. S5E-G). Some of these changes were individually shown (Fig. 4G, H). Expression of classical Yap target genes[17] and YAP target genes known to regulate cell proliferation[18] was further increased in the Sox9Δ hepatocytes (Fig. 4H). Early after Yap-activation, strong Sox9 expression was observed with downregulation of hepatocyte signature genes, and BEC signature gene expression had not been induced yet (Fig. 4G, Fig. S5H, I).

Figure 4. Transcriptomic analysis of hepatocytes with Yap activation.

(A) Schematic diagram of experimental procedure. (B) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes. (C) KEGG pathway analysis. (D-F) Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) of indicated genes Sox9ΔYAP* with Sox9+;YAPS127A hepatocytes. (G-H) Heatmap summarizing expression of the indicated signature genes (G), expression of Yap target and cell proliferation genes (H). (I) PCA plot shows clusters of indicated samples.

To further investigate the role of Sox9 in Yap induced stepwise hepatocyte reprogramming, we compared our data with published RNA-seq data from BECs, hepatocytes, and LPCs[13]. In the principal component analysis (PCA) plot, BEC and LPC samples were clustered independently. Our control hepatocytes were co-localized with hepatocyte samples in GSE55552, indicating a good sample normalization (Fig. 4I). Early after Yap activation (3-4 weeks) (Fig. 4A, Fig. S5B), the hepatocytes were distributed around the center of the plot, and the Sox9+ and Sox9T hepatocyte samples were clustered together (Fig. 4I), suggesting that Yap activation induced hybrid features of LPC and BEC. Sox9 may be dispensable for Yap-induced hepatocyte dedifferentiation but promotes later transformation to BEC-like cells.

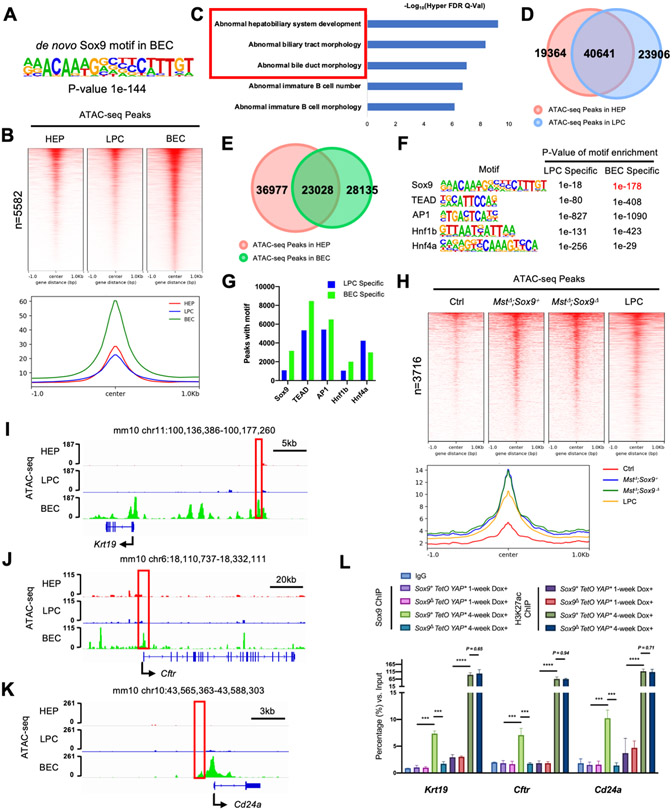

To further understand how Sox9 regulates hepatocyte to BEC-like cell transformation, we analyzed the published Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq) data from BECs, LPCs, and hepatocytes[19] to determine the chromatin accessibility of Sox9 in different cells. As Sox9 dimerization is important for its function[20], we focused on Sox9 dimeric DNA binding motifs and found that they were enriched (5582) in the BEC ATAC peaks (Fig. 5A, B) (Supplementary Table 1). Functional enrichment analysis for these sites suggested that Sox9 plays a more prominent role in BECs (Fig. 5C), and Sox9 is known to regulate biliary development[21]. Indeed, comparison of LPC-and BEC-specific ATAC-peaks containing Sox9 dimeric motifs (Fig. 5D, E) showed that they were enriched in BECs (Fig. 5F, G, S6A). In LPCs, Sox9 may play other roles as the genes with Sox9 dimeric motifs may be involved in inflammation, consistent with severe fibrous stromal reaction in the Sox9+YAP*tumors (Fig. S6B). Similar ATAC-seq analyses were performed with the MstΔ;Sox9+ and MstΔ;Sox9Δ hepatocytes. While the chromatin accessibility in the MstΔ;Sox9+ and MstΔ;Sox9Δ hepatocytes at the putative BEC-specific Sox9 sites was higher than control hepatocytes and LPCs, the peak intensity was the same in these cells (Fig. 5H). Therefore, Sox9 is unlikely to directly regulate chromatin accessibility. Next, we looked into the genes expressed in the BEC lineage that were down-regulated in the Sox9Δ YAP* tumors (Fig. 1 H), and identified potential Sox9 dimeric binding sites in Krt19, Cftr, and Cd24a (Fig. 5I-K, Fig. S6C), which were tested by ChIP-qPCR in the Sox9+; TetO-YAP* and Sox9Δ ; TetO-YAP* liver tissue. 1-week after Dox induction, hepatocytes were dedifferentiating (Fig. S3G), and the genomic regions of the BEC genes were not transcriptionally active. ChIP-qPCR results showed that binding of H3K27ac, which marks active transcription[22], and Sox9 was both weak (Fig. 5L). Consistently, expression of BEC markers Krt19 and Epcam were also weak (Fig. S3C, E). 4-weeks after Dox induction, hepatocytes were already reprogrammed to BEC-like cells[10]. Both H3K27ac and Sox9 chromating binding was much stronger, and H3K27ac binding was Sox9 independent (Fig. 5L), consistent with the ATAC-seq data (Fig. 5H). These data suggest that during BEC lineage specification, Sox9 does not regulate chromatin restructuring, a function that might be fulfilled by Yap activation. Indeed, TEAD DNA binding motifs were also enriched in the BEC-specific ATAC peaks (Fig. 5F), and Yap is required for BEC maintenance[17, 23]. Interestingly, Sox9 binding motifs were located in the vicinity of TEAD binding motifs in the promoter or enhancer regions in some of the Yap or Sox9 target genes (Fig. S7A-B). To determine whether Yap and Sox9 may synergistically regulate gene expression, we cloned genomic DNA fragments containing the TEAD and Sox9 binding sites into a luciferase reporter vector (Supplementary Table 2). Co-expression of SOX9 with YAPs127A in Huh-7 cells partially blocked YAPS127A-induced reporter activities of Ajuba and Ankrd, both are known YAP target genes [18, 24](Fig. S7C, D), which provided an explanation for the enhanced Yap activity by Sox9 deletion (Fig. 4H). However, while Sox9 and YAP both could promote Krt19 and Cftr reporter activities, Sox9’s activity was much stronger (Fig. S7E, F), suggesting that these BEC genes are mainly regulated by Sox9, and at least part of the activities of YAP in BEC may be mediated by Sox9, a YAP target.

Figure 5. ATAC-seq analyses of distinct liver cells.

(A) Sox9 dimeric motifs identified from BEC ATAC-seq peaks. (B) Heatmaps and histogram summarizing the signal intensity of the ATAC-seq peaks contains Sox9 dimeric motifs. (C) GREAT (Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool) analyses for ATAC-seq peaks were shown in (B). (D-E) Venn diagram of ATAC-seq peaks. (F) Motif enrichment analysis for indicated transcription factors in cell-specific ATAC-seq peaks. (G) The number of peaks with indicated DNA binding motifs in cell-specific ATAC-seq peaks. (H) Heatmaps and histogram summarizing the ATAC-seq signal intensity of the peaks contains Sox9 dimeric motifs. (I-K) ATAC-seq signal tracks of indicated gene locus in indicated samples. Box: regions with Sox9 dimeric motifs. (L) ChIP-qPCR analysis of Sox9 binding at the indicated gene locus in the liver tissues.

To further determine the mechanism whereby Sox9 inhibited YAP transcription activities, we generated luciferase reporters containing simplified TEAD and SOX9 binding motifs spatially arranged similarly to those found in Ajuba and Ankrd (Fig. S7A, G) (Supplementary Table 2). Sox9 itself could not change the reporter activity but inhibited YAPs127A – induced transcription activity. Such inhibition was abolished by mutating Sox9 binding motifs (Fig. S7H-K). Furthermore, Co-IP experiments showed that YAP5SA and Sox9 did not bind to each other. However, they formed protein complexes when coexpressed with the reporter vectors containing both TEAD and Sox9 binding sites (Fig. S7L). These results suggest that the Sox9 and YAP interaction depends on their DNA binding, and Sox9 binding may have disrupted concerted interactions of multiple YAP/TEAD binding sites required for strong transcription activation. Such DNA binding–dependent YAP-Sox9 interaction may also explain synergistic activities of Yap and Sox9 in other contexts, for instance, inhibition of Hnf4a expression (Fig. S7M, N).

Sox9 expression is sufficient to promote cell fate plasticity in less differentiated hepatocytes

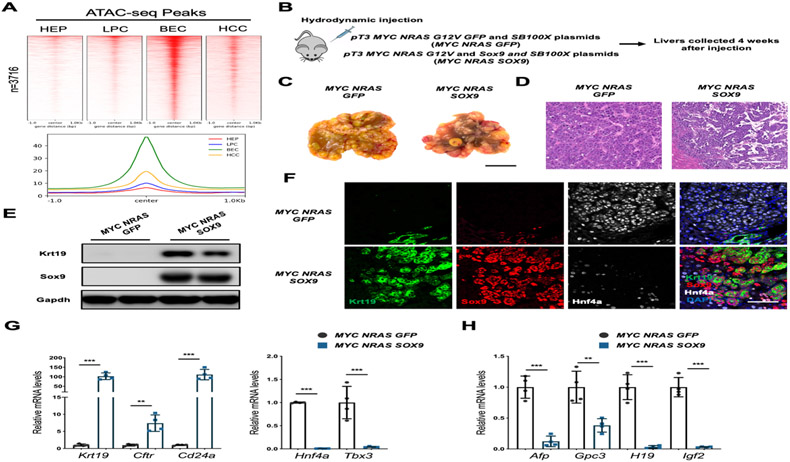

We then tested directly whether Sox9 ectopic expression in hepatocytes is sufficient to induce cell fate reprogramming. As Sox9 binding sites in BEC genes were almost not accessible in hepatocytes (Fig. 5B, H-L), Sox9 overexpression in hepatocytes failed to induce fate transition in vivo (Fig. S8A-D). We therefore decided to alter chromatin accessibility by activating hepatocyte proliferation, which can increase chromatin accessibility[25]. Analyses of published ATAC-seq data from Myc and NrasG12V induced HCC[26] showed that BEC-specific ATAC peaks with Sox9 sites were increased in HCC cells than in normal hepatocytes or LPCs (Fig. 6A). Indeed, overexpressing Sox9 in a mouse HCC model mediated by Myc and NrasG12V overexpression[26] (Fig. 6B, C) was sufficient to induce iCCA-like tumors that expressed BEC genes at the expense of hepatocyte genes (Fig. 6D-G, S8E). Interestingly, Sox9 expression reduced the expression of fetal hepatic/HCC genes (Fig. 6FH), supporting the critical role of Sox9 in BEC differentiation from dedifferentiated hepatocytes. These data show that Sox9 is required for hepatocyte fate plasticity by converting less differentiated hepatocytes to BEC-like cells.

Figure 6. Sox9 promoted BEC fate in less differentiated HCC.

(A) Heatmaps and histogram summarizing the signal intensity of the ATAC-seq peaks contains Sox9 motifs in indicated samples. (B) Schematic diagram of experimental procedure. (C) Representative liver images after the procedure in (B). (D) Representative images of H&E staining. (E) Western blotting analysis. (F) Representative images of immunofluorescent staining, DAPI stains the nucleus. (G-H) qRT-PCR analysis of BEC-and hepatocyte-specific gene expression (G), and HCC gene expression (H) (n=4). Scale bars: 1cm (C), 100μm (D), 50μm (F).

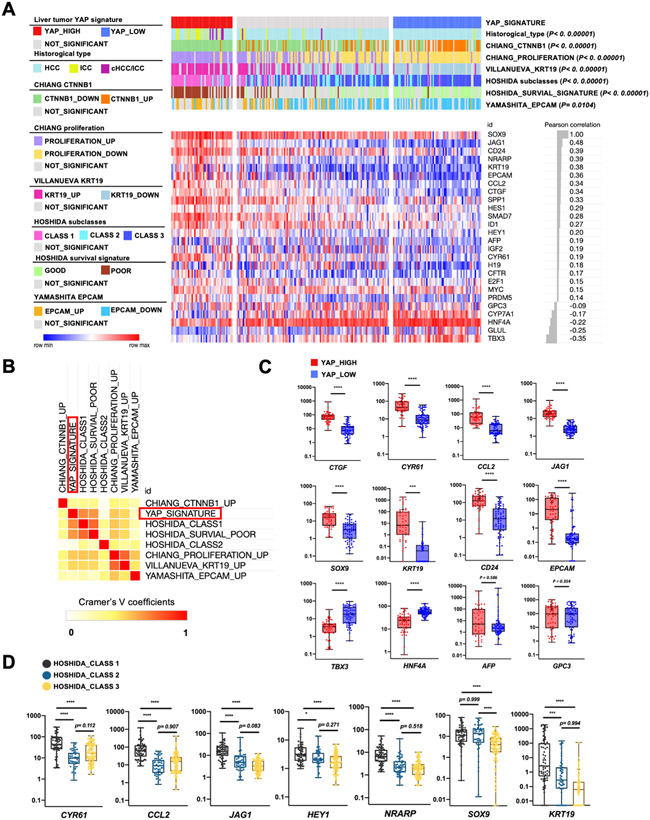

YAP activity and SOX9 expression are strongly correlated with liver tumor plasticity in human patients

We next asked whether the role of Sox9 in Yap-induced hepatocyte fate plasticity is also conserved in human liver tumors. We established a gene set ‘liver tumor YAP signature’ from RNA-seq data of two mouse models (Sox9+ YAP* and MstΔ) for transcriptomic comparison with human patient data (Supplementary Table 3). The LIRI-JP cohort[27], which contains transcriptomic profiling of 236 liver tumor samples of various types, was retrieved from the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) data portal. In these samples, ~20% (n=48) of human primary liver tumors had high YAP activities, whereas ~ 30% (n=69) of the tumors had low YAP activities (Fig. 7A). Notably, iCCA and cHCC-iCCA samples were strongly enriched in the higher YAP activity group (P < 0.00001). To further characterize the tumors with ‘liver tumor YAP signature’, we analyzed the known HCC signatures (Supplementary Table 4). Consistent with the previous finding[28], most tumors with higher YAP activity were also low in β-catenin (CTNNB1) activity. Furthermore, these tumors were highly correlated with previously identified signatures for poorly differentiated HCC or iCCA-like HCC (Fig. 7A). Poor survival signature was also enriched in the higher YAP activity group (Fig. 7A, B). Importantly, SOX9 expression strongly and positively correlated with the expression of not only its target genes CD24 and KRT19, but also the expression of Yap target genes such as CTGF, JAG1 and CCL2, while negatively correlates with the expression of hepatocyte linage genes such as HNF4A, CYP7A1, GLUL, and TBX3 (Fig. 7A, C). A strong correlation of SOX9 and YAP expression was also found at the single-cell level in tumor cells isolated from human HCC and CCA tumor tissues (Fig. S9)[29]. Moreover, SOX9 expression also positively correlated with the expression of Notch signaling target genes NRARP, HEY1 and Tgfβ signaling target genes ID1 and SMAD7(Fig. 7A), which were previously showed to be activated by Hippo/Yap signaling[30-32]. However, there is no statistical difference in the expression of HCC marker genes such as AFP and GPC3 in YAP high and YAP low tumors (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. Analysis of YAP activity and SOX9 expression in human patient cohort.

(A) The prediction for samples with ‘liver tumor YAP signature’ (red in the first row) in LIRI-JP cohort (n = 236). P values determined by Fisher’s exact test. Heatmap shows the expression of listed genes, r values determined by Pearson correlation comparing expression of SOX9 with other genes. (B) Heatmap of Cramer's V coefficiency showing the correlation between the YAP signature and other features. (C) Expression of selected genes in YAP high or low groups in the cohort data. (D) Expression of selected genes in the cohort data grouped by Hoshida HCC signature classes. The y axis indicates log10 transformed normalized counts; lines indicate the median; boxes indicate the first and third quartiles (C, D).

In mouse, hepatocyte plasticity was regulated by Tgfβ signaling and Notch signaling [3, 4, 33]. However, both TGFβ and NOTCH signature genes were activated in Sox9+ and Sox9Δ hepatocytes (Fig. S10A-D), suggesting Sox9 may control hepatocyte programming independently of NOTCH or TGFβ signaling. To test whether both SOX9 and YAP may regulate human tumor plasticity, we clustered the patient samples using Hoshida tumor signatures[14], in which class 1 defined iCCA-like tumors and class 3 defined well-differentiated HCC. While SOX9 expression was high in HOSHIDA class1 and class 2, YAP activity was only high in HOSHIDA class 1 (Fig. 7D), suggesting that both high YAP activity and SOX9 expression are required for iCCA-like tumor formation (Fig. 7D).

Discussion

In this study, we used lineage tracing and multiple genetic models to show that Sox9 plays a critical role in regulating hepatocyte cell fate plasticity, which is important in the formation of HCC and iCCA, two major primary liver tumors that can originate from hepatocytes in mouse models[2]. The in vivo function of Sox9 in primary liver tumors was not clear before the current studies. Previous studies suggest that Yap and Wnt/β–catenin antagonizes each other in liver cell fate determination during hepatocarcinogenesis[12, 28]. Overexpression of YAPS127A together with constitutively activated β-catenin in the liver leads to hepatoblastoma formation but not Sox9+ iCCA-like tumor formation[34], suggesting that activated β-catenin may have inhibited Sox9 expression, a phenomenon observed in chondrocyte differentiation[35]. Constitutive Yap activation in adult hepatocytes led to much higher expression of HCC and fetal hepatocyte markers such as Afp and Gpc3, suggesting that strong Yap activation resulted in hepatocyte dedifferentiation to a fetal like state. In this study, we showed that oncogenic reprogramming of hepatocytes is a stepwise process. While Sox9 has limited function in hepatocyte dedifferentiation, it is both necessary and sufficient for lineage specification of BEC-like cells. Sox9 itself is not enough to break epigenetic barrier between hepatocytes and BECs. Yap/Taz or some other transcription or chromatin remodeling factors regulated by Yap may need to change the epigenetic programming to allow BEC-like lineage specification by Sox9. Increased chromatin accessibility associated with cell proliferation may be an underlying mechanism of oncogenic reprogramming of hepatocytes coupled with chronic injury or oncogenic gene expression. In DDC-induced portal vein injury, in which hepatocyte plasticity is observed, genetic deletion of Arid1a in hepatocytes strongly dampened Sox9 expression with impaired ductal reaction and liver regeneration[19], suggesting Sox9 in hepatocytes may be required to regulate hepatocyte plasticity in the context of injury repair. However, if hepatocyte plasticity is not involved in the case of CCl4-induced liver injury[36] or partial hepatectomy, Sox9 in hepatocytes is known to be dispensable in liver regeneration after CCl4-induced liver injury[36] and likely after partial hepatectomy as well.

Our findings that YAP signature is enriched in Sox9− hepatocytes are surprising and interesting. Sox9 can be a Yap-induced inhibitor of Yap transcription activity. Such negative regulation is quite common in many signaling pathways, possibly as part of negative feedback. Under physiological conditions, Yap activity is higher in Sox9+ BEC cells[10], where Sox9 may be required to keep Yap activity below certain levels to prevent abnormal cell proliferation. Consistent with this notion, Sox9+ ductal/biliary compartment rarely contributes to HCC formation in different mouse models, but these cells contribute to benign lesions and tumor heterogeneity[12, 37, 38]. Loss of Sox9 in hepatocytes strongly promoted tumor growth, and one mechanism is Sox9 inhibition of Yap transcription activity in a DNA-target-dependent manner. In support of this, we previously found that loss of Mst1 and Mst2 only in Sox9+ cells in the liver led to biliary duct hyperplasia without tumor formation[12]. Notch and Tgfβ signaling are activated downstream of Yap/Taz, and they are each sufficient to induce BEC-like differentiation from hepatocytes[3, 4, 33]. Such activities should also require Sox9 as Yap-induced hepatocyte reprogramming to BECs did not occur without Sox9, though Notch and Tgfβ signaling was still activated (Fig. S10). In addition, it has been shown that the SOX9 high iCCA-like cells proliferate much slower than SOX9 low HCC cells[28]. In addition, ICC-like HCC and cHCC-ICC with both SOX9+ and SOX9− cells are correlated with poor tumor prognosis [14, 39]. Although several studies have discussed YAP activity in human liver tumors[28, 40, 41], whether YAP activity predicts tumor prognosis remains controversial, possibly due to the lack of good YAP signature gene set to determine YAP activity reliably. In this study, we identified a ‘YAP liver tumor signature’ gene set and used it to classify with high statistical confidence a subset of human iCCA and cHCC-iCCA samples that were strongly enriched in the high YAP activity group and SOX9 expression, suggesting that the YAP-SOX9 axis may also determine cell fate plasticity in human liver tumors, which contributes to cellular and molecular heterogeneity that impacts liver tumor malignancy and strategies of treatment. Our transcriptome analysis showed that the poor outcome in these patients was highly correlated with higher YAP activity and Yap high but Sox9− or Sox9 low cells in these heterogeneous tumors may have caused poor outcome. Analyses of HCC tumors with high YAP activity but homogenously low Sox9 expression, which are currently very rare in the published datasets, will be more informative to tell whether such tumors show worse prognosis. As more tumor samples are collected and analyzed histologically and molecularly, more insight could be gained in the future.

Supplementary Material

Sox9 is required for Yap-induced hepatocyte plasticity during hepatocarcinogenesis in mice.

Sox9 removal in hepatocytes with Yap activation resulted in more aggressive HCC.

Sox9 expression is sufficient to promote cell fate plasticity in less differentiated hepatocytes in vivo.

YAP activity and SOX9 expression are strongly correlated with liver tumor plasticity in human patients.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the Yang lab for stimulating discussion. This work was supported by the NIH grant 1R01CA222571 to YY. LM and XWW are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute. ZS and XW are funded by federal funds from the National Cancer Institute Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. We thank the Rodent Histopathology Core at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston, MA, supported in part by a NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH 5 P30 CA06516, for consulting service of mouse liver pathology.

Grant support:

The work in the Yang Lab is supported by the NIH grants R01CA222571 to Y. Yang. LM and XWW are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute. ZS and XW are funded by the Intramural Research Program of National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. BG is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Abbreviations:

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- iCCA

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- BEC

biliary epithelial cell

- LPC

liver progenitor cell

- TBG

thyroxine-binding globulin

- AAV8

adeno-associated virus 8

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA Sequencing

- ATAC-seq

Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin using sequencing

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- GSEA

gene set enrichment analysis

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- EdU

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Sequencing Profiling:

RNA-seq: GSE146589, Secure token for reviewers: obwfswuirzehfsn

ATAC-seq: PRJNA732288, Secure link for reviewers: https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/object/PRJNA732288?reviewer=3g51ufvun23odpjaa6m4ricd1k

Data Transparency Statement: Data, analytic methods, and study materials are available to other researchers in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Sequencing data are available in the public databases as indicated above.

References

- [1].Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sia D, Villanueva A, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Liver Cancer Cell of Origin, Molecular Class, and Effects on Patient Prognosis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:745–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fan B, Malato Y, Calvisi DF, Naqvi S, Razumilava N, Ribback S, et al. Cholangiocarcinomas can originate from hepatocytes in mice. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2911–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma can arise from Notch-mediated conversion of hepatocytes. J Clin Invest 2012;122:3914–3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature 2013;501:328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zheng Y, Pan D. The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Dev Cell 2019;50:264–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Song H, Mak KK, Topol L, Yun K, Hu J, Garrett L, et al. Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:1431–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lu L, Li Y, Kim SM, Bossuyt W, Liu P, Qiu Q, et al. Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:1437–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lee KP, Lee JH, Kim TS, Kim TH, Park HD, Byun JS, et al. The Hippo-Salvador pathway restrains hepatic oval cell proliferation, liver size, and liver tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:8248–8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yimlamai D, Christodoulou C, Galli GG, Yanger K, Pepe-Mooney B, Gurung B, et al. Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell 2014;157:1324–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev 2007;21:2747–2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kim W, Khan SK, Gvozdenovic-Jeremic J, Kim Y, Dahlman J, Kim H, et al. Hippo signaling interactions with Wnt/beta-catenin and Notch signaling repress liver tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest 2017;127:137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tarlow BD, Pelz C, Naugler WE, Wakefield L, Wilson EM, Finegold MJ, et al. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell 2014;15:605–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hoshida Y, Nijman SM, Kobayashi M, Chan JA, Brunet JP, Chiang DY, et al. Integrative transcriptome analysis reveals common molecular subclasses of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2009;69:7385–7392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Anvarian Z, Mykytyn K, Mukhopadhyay S, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2019;15:199–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hu H, Gehart H, Artegiani B, C LO-I, Dekkers F, Basak O, et al. Long-Term Expansion of Functional Mouse and Human Hepatocytes as 3D Organoids. Cell 2018;175:1591–1606 e1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pepe-Mooney BJ, Dill MT, Alemany A, Ordovas-Montanes J, Matsushita Y, Rao A, et al. Single-Cell Analysis of the Liver Epithelium Reveals Dynamic Heterogeneity and an Essential Role for YAP in Homeostasis and Regeneration. Cell Stem Cell 2019;25:23–38 e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zanconato F, Forcato M, Battilana G, Azzolin L, Quaranta E, Bodega B, et al. Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat Cell Biol 2015;17:1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li W, Yang L, He Q, Hu C, Zhu L, Ma X, et al. A Homeostatic Arid1a-Dependent Permissive Chromatin State Licenses Hepatocyte Responsiveness to Liver-Injury-Associated YAP Signaling. Cell Stem Cell 2019;25:54–68 e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ohba S, He X, Hojo H, McMahon AP. Distinct Transcriptional Programs Underlie Sox9 Regulation of the Mammalian Chondrocyte. Cell Rep 2015;12:229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Antoniou A, Raynaud P, Cordi S, Zong Y, Tronche F, Stanger BZ, et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology 2009;136:2325–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:21931–21936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Planas-Paz L, Sun T, Pikiolek M, Cochran NR, Bergling S, Orsini V, et al. YAP, but Not RSPO-LGR4/5, Signaling in Biliary Epithelial Cells Promotes a Ductular Reaction in Response to Liver Injury. Cell Stem Cell 2019;25:39–53 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lange AW, Sridharan A, Xu Y, Stripp BR, Perl AK, Whitsett JA. Hippo/Yap signaling controls epithelial progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation in the embryonic and adult lung. J Mol Cell Biol 2015;7:35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ma Y, Kanakousaki K, Buttitta L. How the cell cycle impacts chromatin architecture and influences cell fate. Front Genet 2015;6:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Seehawer M, Heinzmann F, D'Artista L, Harbig J, Roux PF, Hoenicke L, et al. Necroptosis microenvironment directs lineage commitment in liver cancer. Nature 2018;562:69–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fujimoto A, Furuta M, Totoki Y, Tsunoda T, Kato M, Shiraishi Y, et al. Whole-genome mutational landscape and characterization of noncoding and structural mutations in liver cancer. Nat Genet 2016;48:500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fitamant J, Kottakis F, Benhamouche S, Tian HS, Chuvin N, Parachoniak CA, et al. YAP Inhibition Restores Hepatocyte Differentiation in Advanced HCC, Leading to Tumor Regression. Cell Rep 2015;10:1692–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ma L, Hernandez MO, Zhao Y, Mehta M, Tran B, Kelly M, et al. Tumor Cell Biodiversity Drives Microenvironmental Reprogramming in Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell 2019;36:418–430 e416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lee DH, Park JO, Kim TS, Kim SK, Kim TH, Kim MC, et al. LATS-YAP/TAZ controls lineage specification by regulating TGFbeta signaling and Hnf4alpha expression during liver development. Nature communications 2016;7:11961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nishio M, Sugimachi K, Goto H, Wang J, Morikawa T, Miyachi Y, et al. Dysregulated YAP1/TAZ and TGF-beta signaling mediate hepatocarcinogenesis in Mob1a/1b-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113:E71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Patel SH, Camargo FD, Yimlamai D. Hippo Signaling in the Liver Regulates Organ Size, Cell Fate, and Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2017;152:533–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schaub JR, Huppert KA, Kurial SNT, Hsu BY, Cast AE, Donnelly B, et al. De novo formation of the biliary system by TGFbeta-mediated hepatocyte transdifferentiation. Nature 2018;557:247–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tao J, Calvisi DF, Ranganathan S, Cigliano A, Zhou L, Singh S, et al. Activation of beta-catenin and Yap1 in human hepatoblastoma and induction of hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology 2014;147:690–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Day TF, Guo X, Garrett-Beal L, Yang Y. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in mesenchymal progenitors controls osteoblast and chondrocyte differentiation during vertebrate skeletogenesis. Dev Cell 2005;8:739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Athwal VS, Pritchett J, Llewellyn J, Martin K, Camacho E, Raza SM, et al. SOX9 predicts progression toward cirrhosis in patients while its loss protects against liver fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med 2017;9:1696–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jors S, Jeliazkova P, Ringelhan M, Thalhammer J, Durl S, Ferrer J, et al. Lineage fate of ductular reactions in liver injury and carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest 2015;125:2445–2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mu X, Espanol-Suner R, Mederacke I, Affo S, Manco R, Sempoux C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma originates from hepatocytes and not from the progenitor/biliary compartment. J Clin Invest 2015;125:3891–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Xue R, Chen L, Zhang C, Fujita M, Li R, Yan SM, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Profiling of Combined Hepatocellular and Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Reveals Distinct Molecular Subtypes. Cancer Cell 2019;35:932–947 e938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang Y, Xu X, Maglic D, Dill MT, Mojumdar K, Ng PK, et al. Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of the Hippo Signaling Pathway in Cancer. Cell Rep 2018;25:1304–1317 e1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tschaharganeh DF, Chen X, Latzko P, Malz M, Gaida MM, Felix K, et al. Yes-associated protein up-regulates Jagged-1 and activates the Notch pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2013;144:1530–1542 e1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

RNA-seq data were deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GSE146589). ATAC-seq data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) of NIH (PRJNA 732288).

Other materials and methods are shown in the supplementary methods and supplementary CTAT table.