Abstract

We have encountered a previously unrecognized specificity problem when using the small-subunit ribosomal DNA (16S rDNA)-based PCR primers recommended for use in the identification of Ehrlichia equi in clinical samples. These PCR primers annealed to E. platys 16S rDNA in blood samples containing high levels of E. platys organisms. Therefore, we designed and tested new PCR primers for the identification of E. equi.

Since 1996 we have routinely isolated genomic DNA from EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples for subsequent PCR of the small-subunit ribosomal DNA (16S rDNA) from members of the genus Ehrlichia (3, 4). For the identification of Ehrlichia equi, we have used PCR forward primer EE-3 (5′GTCGAACGGATTATTCTTTATAGCTTGC), which, in combination with the Ehrlichia genus-specific reverse primer HE3-R (5′CTTCTATAGGTACCGTCATTATCTTCCCTAT), has been reported to specifically amplify partial 16S rDNA from E. equi, human granulocytic Ehrlichia (HGE), and Ehrlichia phagocytophila, as described earlier (1, 2). Therefore, the specificity of our PCR assay for E. equi relied solely on the specificity of primer EE-3. We tested the EE-3–HE3-R primer combination against the genomic DNAs of E. equi, Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, Ehrlichia risticii, Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, and Rickettsia rickettsii in independent PCR experiments, all of which supported the specificities of the primers. In 1997, after PCR amplification and sequencing of Ehrlichia platys 16S rDNA from the blood of a sick dog (3), we devised PCR primers that would amplify E. platys 16S rDNA. The specificities of these primers (primer E. platys [5′GATTTTTGTCGTAGCTTGCTA] and primer Ehrl3-IP2 [5′TCATCTAATAGCGATAAATC]) were confirmed as described above for the primer combination EE-3–HE3-R by the addition of an EDTA-anticoagulated blood sample from the dog that had previously tested positive for E. platys 16S rDNA by PCR (3).

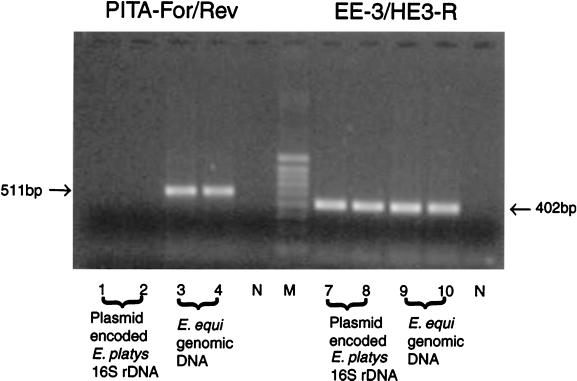

Subsequently, while testing EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples from dogs from Venezuela for the presence of Ehrlichia species, we obtained positive PCR results by both E. equi-specific and E. platys-specific PCRs, indicating that the corresponding dogs were potentially coinfected with both E. equi and E. platys. Since E. equi had never been reported in dogs from Venezuela, it was important to ensure the accuracies of these results. The PCR products (402 bp) from one dog were cloned, and the inserts of five clones were sequenced; the sequences were found to be identical to that of E. platys 16S rDNA. This finding suggested that E. equi-specific primer EE-3, reported previously (1), in combination with primer HE3-R also amplified E. platys 16S rDNA. To further examine our results, we had to design a sample that was free of E. equi 16S rDNA. For this purpose, we transformed Escherichia coli strain JM109 with a plasmid that encoded the E. platys 16S rDNA (1,492 bp) that was originally derived from a dog in which E. platys was visualized as morulae within platelets on a blood smear. Therefore, the resulting E. coli strain contained host-specific 16S rDNA as well as plasmid-encoded partial 16S rDNA for E. platys. In subsequent PCR experiments with primer pair EE-3–HE3-R and the recombinant E. coli strain, we could amplify E. platys 16S rDNA, even under stringent conditions. The annealing temperature for the primers was 55°C in our PCRs, whereas it was previously recommended to be 50°C (1). Again, our findings were confirmed by DNA sequencing. We could reproduce our experimental findings with an additional seven EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples received for diagnostic testing, but only when samples from dogs that had a high level of E. platys ehrlichemia as determined by microscopy were used. We therefore designed primers PITA-Fwd (5′-GTCGAACGGATTATTCTTTA-3′) and PITA-Rev (5′-TTCACCTTTAACTTACCGAA-3′) and tested this primer set against EE-3 and HE3-R using E. equi genomic DNA as well as plasmid DNA encoding E. platys 16S rDNA (Fig. 1). Again, the primer combination EE-3–HE3-R amplified both E. equi and E. platys partial 16S rDNAs. The primers PITA-Fwd and PITA-Rev amplified partial E. equi 16S rDNA, but no amplification products were observed for E. platys. The revised primers did not amplify E. canis, E. chaffeensis, or E. ewingii 16S rDNA (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Comparison of PCRs with primer sets EE-3–HE3-R and PITA-Fwd–PITA-Rev for the identification of E. equi separated on a 1% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Lanes N, negative control; lane M, molecular weight marker. The sizes of the corresponding PCR fragments are indicated in base pairs (bp).

Although clinical diagnostics increasingly rely on the remarkable sensitivity of PCR, insufficient specificity can lead to misleading results. The work by Barlough et al. (1) was one of the keys to the identification of E. equi in horses and Ixodes pacificus ticks by PCR. However, on the basis of the results of our study, primer EE-3 previously described for use for the PCR-based identification of E. equi can cause false-positive results for clinical blood samples containing large numbers of E. platys organisms. Although primer EE-3 was originally used in combination with primer EE-4 in a nested PCR approach to identify E. equi (1), it should be noted that EE-4 is 100% homologous to the corresponding target regions in E. equi and E. platys 16S rDNAs. Barlough et al. (1) designed their PCR primers for the examination of equine blood samples with the software package Amplify (University of Wisconsin, Madison). When using the same software, we were unable to identify the nonspecific annealing of PCR primer EE-3 with E. platys 16S rDNA. However, a later version of the Amplify program does detect the nonspecific annealing event. Since the findings of Barlough et al. (1) allowed many researchers, including us, to streamline their experiments, we can only assume that primers EE-3 and EE-4 are widely used for the identification of E. equi, HGE, and E. phagocytophila (2), which can infect humans, cats, dogs, horses, and numerous wild animal species (5). Primers PITA-Fwd and PITA-Rev, as described in the present study, are suggested for use for the identification of E. equi under the following PCR conditions: 5 min at 95°C, followed by 50 amplification cycles (45 s at 95°C, 45 s at 55°C, 1 min at 72°C), and a final extension step for 5 min at 72°C.

Due to the prolonged incubation period and the substantial difficulties associated with in vitro cell culture of most Ehrlichia species from patient blood samples, rapid PCR-based detection methods are of considerable clinical utility. However, the observations reported here demonstrate that the differentiation of Ehrlichia species by PCR with “species-specific primers” is not always a straightforward approach. When possible, we suggest that the amplified PCR fragments be sequenced to confirm the validity of the PCR results when an attempt is being made to differentiate Ehrlichia species, particularly when PCR is applied to samples derived from animals other than dogs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the State of North Carolina and in part by a grant from Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, Iowa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barlough J E, Madigan J E, DeRock E, Bigornia L. Nested polymerase chain reaction for detection of Ehrlichia equi genomic DNA in horses and ticks (Ixodes pacificus) Vet Parasitol. 1996;63:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlough J E, Madigan J E, Turoff D R, Clover J R, Shelly S M, Dumler J S. An Ehrlichia strain from a llama (Lama glama) and llama-associated tick (Ixodes pacificus) J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1005–1007. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.1005-1007.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Hancock S I. Sequential evaluation of dogs naturally infected with Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia ewingii, or Bartonella vinsonii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2645–2651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2645-2651.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kordick S K, Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Southwick K L, Colitz C M, Hancock S I, Bradley J M, Rumbough R, McPherson J T, MacCormack J N. Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a Walker hound kennel in North Carolina. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2631–2638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2631-2638.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pusterla N, Chang C C, Chomel B B, Chae J S, Foley J E, DeRock E, Kramer V L, Lutz H, Madigan J E. Serologic and molecular evidence of Ehrlichia spp. in coyotes in California. J Wildl Dis. 2000;36:494–499. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-36.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]