Abstract

Background

Cardiac masses include various tumourous and non-tumourous lesions. Primary cardiac tumours are very rare and most commonly benign. Primary cardiac lymphomas (PCL) account for 1–2% of malignant primary cardiac tumours. Only 197 cases of PCL have been reported between 1949 and 2009.

Case summary

We report a case of a 73-year-old patient who presented with atrial flutter. The diagnosis was a tumourous cardiac mass in the right atrium with signs of the infiltration of the tricuspid valve insertion and pericardium. There were no signs of extracardiac disease at the initial presentation. The patient was deemed to be inoperable by cardiac surgeons. Rapid tumour progression caused atrioventricular-block type Mobitz 2 with concomitant obstruction of the tricuspid valve and axillary lymph node metastasizing. Excision of the axillary lymph node revealed a diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. An epicardial right ventricle single lead pacemaker was sited, and chemotherapy was administered, resulting in complete remission.

Discussion

Cardiac masses are rare and challenging cases. Although current imaging procedures deliver extensive information, histological examination is still required in many cases. We encountered a tumourous mass with deep infiltration. After the patient was deemed inoperable, later lymph node invasion allowed histological examination, revealing PCL. Primary cardiac lymphomas are life-threatening tumours with rapid and aggressive growth. Treatment is based on chemotherapy consisting of anthracycline-containing regimens. This case report highlights the curative potential of chemotherapy, as we report a rapid regression of the tumour as well as the disappearance of arrhythmias and conduction disorders after treatment.

Keywords: Cardiac mass, Primary cardiac lymphoma, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Cardiac arrhythmias, Case report

Specialties other than cardiology involved

Radiology, haematology and oncology

Learning points.

Cardiac masses are challenging cases due to their rarity and complexity. The diagnosis relies heavily on the use of multiple imaging techniques. However, histological examination is still required in many cases.

The prognosis of cardiac masses without histological examination can be misleading, even if they are deeply infiltrated.

Primary cardiac lymphomas are rare life-threatening cardiac tumours that primarily affect the right heart chambers, causing dyspnoea, arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, and heart failure. Chemotherapy with anthracycline-containing regimens, such as Rituximab, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisolon could be a curative treatment.

Cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disorders due to tumourous infiltration of the electrical conduction system of the heart can resolve with appropriate chemotherapy targeting the underlying tumour.

Introduction

Cardiac masses include various tumourous and non-tumourous lesions. Primary cardiac tumours are very rare and have a prevalence of only 0.05%, according to surgery and autopsy reports. Secondary cardiac tumours are seen more frequently (1% of all autopsies).1 Malignant tumours comprise 25% of all primary cardiac tumours and are mostly sarcomas.2 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL) accounts for 1–2% of malignant primary cardiac tumours,3 making them one of the rarest cardiac tumours. They are defined as extranodal lymphoma involving only the heart and/or pericardium.4 Between 1949 and 2009, a total of 197 cases of PCL were reported worldwide.4

Here, we report a case of a 73-year-old immunocompetent woman who was diagnosed with PCL and treated successfully with chemotherapy and a pacemaker, after she had been deemed to be inoperable.

Timeline

| Date | Event | Procedure |

|---|---|---|

| January 2020 |

|

|

| February 2020 | Patient referred to two different cardiac surgery centres, one of which specialized in cardiac tumours. Both deemed the patient to be inoperable due to widespread cardiac infiltration | Active surveillance and best supportive therapy |

| March 2020 |

|

|

| April 2020–June 2020 | Continuation of chemotherapy | Five cycles of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone) |

| August 2020–January 2021 | Complete remission with no remaining cardiac mass, extracardiac disease, or AV conduction disorder |

|

Case presentation

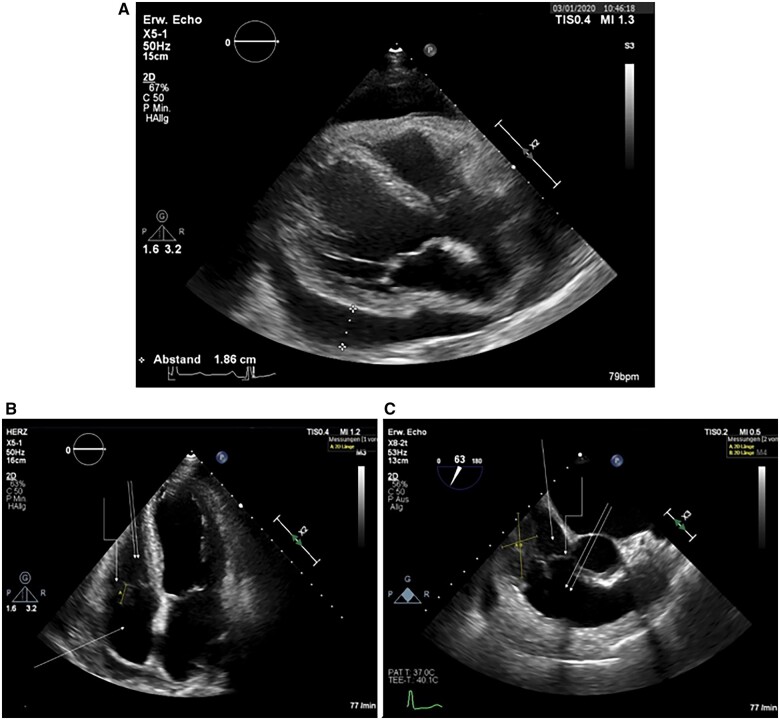

We present the case of a 73-year-old German female patient with a history of axial diaphragma hernia, sigma diverticulosis, and no cardiologic medical history, who was admitted with new-onset atrial flutter. She complained of fatigue, dizziness, and dyspnoea. Physical examination revealed a rapid regular pulse rate of 120–130 beat per minute (b.p.m.), normal lung and heart sounds, and no peripheral oedema. Therapy of atrial flutter with cavotricuspid isthmus ablation was planned. However, transthoracic and transoesophageal echocardiography revealed a large, heterogeneous, isoechoic, immobile mass with lobulated margins attached to the free anterior wall of the right atrium at the base of the tricuspid valve accompanied by circular, hypoechoic pericardial effusion with compression of the right atrium (Figure 1). No haemodynamic impairment was noted clinically. Based on the findings, we performed pericardiocentesis via a subxiphoidal approach. Laboratory and cytology examinations of the pericardial fluid showed cell, protein, and lactate hydrogenase (LDH)-rich fluid (cell count 3100/µL, protein 4.6 g/dL, and LDH 11 399 U/L) with reactively changed cell population, mainly histiocytes and mesothelial cells. Atypical cell populations were even with immunohistochemical staining not seen. Laboratory serum examination was non-specific and showed the following values: haemoglobin 11.9 g/dL (normal range 12–16 g/dL), LDH 322 U/L (normal range 135–250 U/L), C-reactive protein 6.3 mg/dL (normal range <0.5 mg/dL), pro-BNP II 2834 pg/mL (normal range <125 pg/mL), serum protein 5.9 g/dL (normal range 6.4–8.3 g/dL) and normal values of carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen (CA) 125, CA 15-3, CA 19-9, and alpha-fetoprotein.

Figure 1.

Baseline echocardiography of the patient from January 2020.

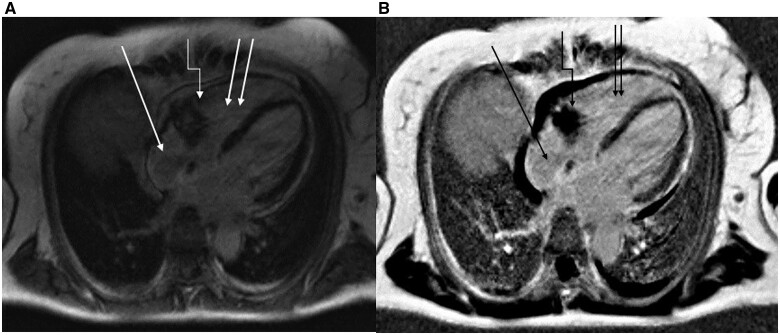

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 51- × 32-mm tumourous myocardial isointense mass in late T1-weighted MRI sequence with diffuse infiltration of the myocardium and extension into the pericardium (Figure 2). Although at this point it was clear that the mass had malignant behaviour, it was unclear if it was primary or secondary. We searched for primary tumours or metastases via computed tomography of the skull, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, along with breast sonography and mammography, dermatologic and gynaecologic screening examinations and endoscopy of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract. No extracardiac disease was noted, and no enlarged lymph nodes were observed in the whole body.

Figure 2.

Baseline cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of the patient from January 2020.

With the hypothesis of cardiac sarcoma, the patient was referred to two different cardiac surgery centres in Germany, one of which specialized in cardiac tumour surgery. Both centres deemed the patient inoperable and recommended active surveillance and best supportive therapy.

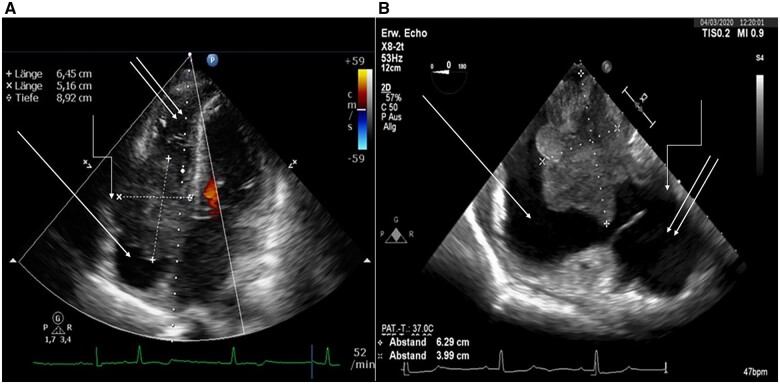

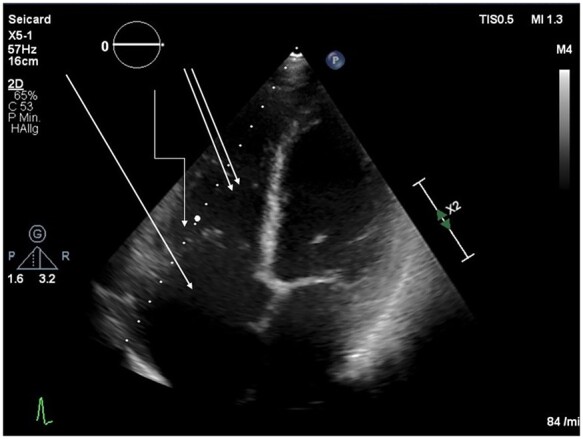

Three weeks later, the patient returned to our emergency centre with fatigue and dizziness. Electrocardiogram revealed atrioventricular (AV) block II type Mobitz 2. Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed a massive progression of the tumour mass (Figure 3A). Transoesophageal echocardiography showed a subtotal obstruction of the tricuspid valve (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Echocardiography of the patient from March 2020.

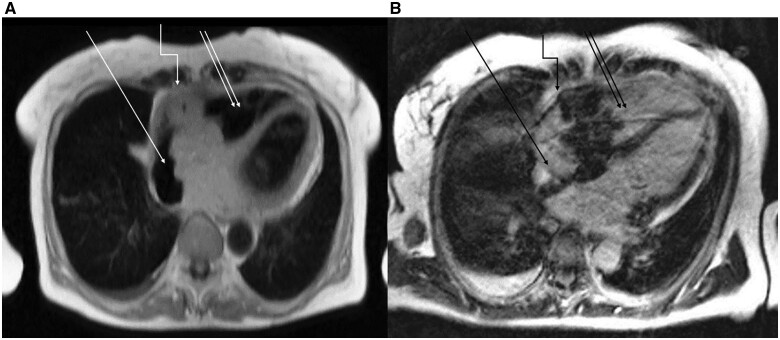

Cardiac MRI documented an infiltration of the cardiac base adjacent to the atrial septum and suspected transpericardial infiltration of the diaphragm. New bilateral axillary lymph nodes with enlargement up to 33 mm in diameter were found, suggesting extracardiac metastases (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging of the patient from March 2020.

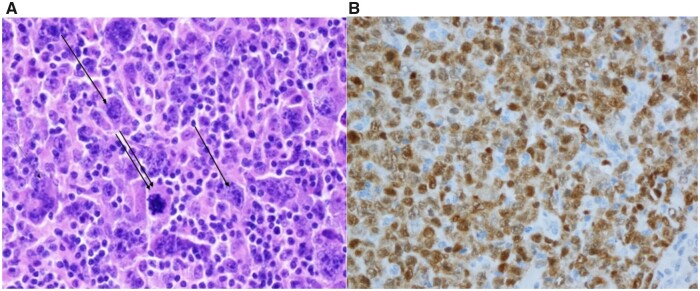

An epicardial right ventricle single lead pacemaker was sited via a subxiphoid approach, as it appeared unlikely to be able to cross the obstruction of the tricuspid valve with the pacemaker lead. Axillary lymph node excision revealed a diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of non-germ-cell type by Hans classification5 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pathohistological examination of the axillary lymph node of the patient from March 2020.

Within 2 days, we initiated a pre-phase treatment with rituximab and prednisolone for one week (rituximab 800 mg one time and prednisolone 100 mg once daily for 7 days), followed by a first course of reduced-dose chemotherapy including rituximab 375 g/m2, cyclophosphamide 400 mg/m2, doxorubicin 25 mg/m2, vincristine 1 mg, and prednisolone 40 mg/m2 [R-mini-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone)]. All five subsequent courses of chemotherapy were administered at full dose including rituximab 375 g/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2, vincristine 2 m, and prednisolone 100 mg/m2 (R-CHOP) under granulocyte colony-stimulating factor prophylaxis with pegfilgrastim. Pre-phase treatment and reduced-dose chemotherapy (R-mini-CHOP) were chosen to reduce the risk of complications due to rapid tumour lysis. In total, the patient received pre-phase treatment with rituximab and prednisolone, one cycle of R-mini-CHOP and five cycles of R-CHOP between 12 March 2020 and 12 June 2020.

Follow-up examinations of the patient, including serial echocardiograms and 18-fluorine-flurodeoxyglucose positron tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT) showed complete remission of the tumour with no remaining cardiac mass or extracardiac disease (Figure 6). The pacemaker showed no stimulation and no arrhythmia burden after remission.

Figure 6.

Echocardiography of the patient after chemotherapy from November 2020.

Discussion

The clinical approach of cardiac masses is very challenging due to their rarity and complexity. The diagnosis relies heavily on the use of multiple imaging techniques. However, in many cases, histological examination is still required.6

Echocardiography is the first-choice procedure in the approach of cardiac masses.6,7 In our case, the tumour mass was discovered on transthoracic echocardiography and confirmed via transoesophageal echocardiography, which revealed further information about its size, contours, and haemodynamic impact. We used cardiac MRI to obtain additional information about the anatomy and invasiveness of the tumour, as its superiority in the detection and diagnosis of cardiac tumours has been shown.8,9

Cardiac MRI showed a tumour mass with malignant behaviour without providing a conclusive diagnosis. Therefore, we performed detailed tumour screening to search for primary tumours or metastases, concluding no extracardiac disease. Moreover, the pericardiac fluid did not provide any further information. With the hypothesis of cardiac sarcoma, the patient was referred to two cardiac surgery centres. However, because complete resection of the mass was impossible and cardiac surgery to obtain a specimen for histological examination was not justified, the patient was deemed to be inoperable, given the extremely high perioperative risk and very poor prognosis.

When the patient presented 3 weeks later with AV block and massive growth of the cardiac mass, she was initially treated with an epicardial right ventricle single lead pacemaker and then re-evaluated. For the first time, an extracardiac manifestation was spotted, allowing histological examination. Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma was revealed, and chemotherapy was initiated. In the context of lymphoma with only cardiac manifestation at first, PCL was diagnosed.

Primary cardiac lymphomas are life-threatening tumours with rapid and aggressive growth if not treated early and properly. The most frequent clinical presentations include dyspnoea, arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, and heart failure. Atrial fibrillation or flutter and AV conduction blocks are the most common arrhythmias.4 They primarily affect the right atrium and right ventricle. Involvement of the intra-atrial septum (41%) and of the superior vena cava (25%) has been described.4 Like other cardiac tumours, the diagnosis relies on a multimodality imaging approach and histologic examination. Echocardiography and cardiac MRI are the most frequently used procedures.10 Classic signs of PCL in cardiac MRI are high signal intensity in T2-weighted images with inversion in T1-weighted images in comparison with myocardium after application of contrast material. Necrotic areas are possible.11 18F-FDG-PET/CT has a promising role in the diagnosis of cardiac masses, as it can add information about the malignancy of cardiac masses and help to detect extracardiac disease.10 However, this technique has not been routinely established in the approach of cardiac masses.

Histological diagnosis is essential for managing malignant cardiac tumours. However, preoperative sampling represents a major challenge, as samples are traditionally obtained through thoracotomy. Currently, less invasive procedures such as transoesophageal echocardiographic-guided biopsy with or without combined fluoroscopy have been reported.12 Primary cardiac lymphomas are usually non-Hodgkin lymphomas, most commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.4 Micro- and macroscopically, the tumours have the same features as the more common extracardiac lymphomas.7

Treatment of PCLs consists mainly of chemotherapy.12,13 Anthracycline-containing regimens, primarily CHOP, are the main reported regimens.4,14 The addition of rituximab was first reported in 2001,4 which improved therapeutic efficacy.14 Tumour lysis syndrome and sepsis contribute to the treatment-related mortality rate for chemotherapy of 10%.4 Death can also occur early under chemotherapy because of massive pulmonary thromboembolism.13 Moreover, there is also a theoretical risk of cardiac wall perforation, ventricular septal rupture, life-threatening arrhythmias, and pericardial effusion in response to chemotherapy.12,15,16 Reports showed that a 50% dose reduction of cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin (as in R-mini-CHOP) in the initial course of chemotherapy decreases the risk of sudden death.

Surgical resection or radiotherapy was used in some reported cases.4 Radiotherapy has been mostly reported as an addition to chemotherapy,4 particularly when PCL grows despite chemotherapy.12 Radiotherapy could allow improvement in survival, as some reports have shown.13 Nevertheless, its application may have been limited because of its risk of pericarditis, cardiomyopathy, diastolic dysfunction, conduction defects, and coronary artery disease.12

Conclusion

Cardiac masses are rare and challenging cases. Although current imaging procedures deliver extensive information, histological examination is still required in many cases. Quick diagnosis allows the manifestation of even rare tumours, which need special treatment, improving the patient’s outcome dramatically. In our case, we diagnosed a PCL and treated it with chemotherapy, achieving complete remission of the tumour. We were particularly surprised by the rapid regression of the tricuspid valve obstruction, reduction of tumour mass and disappearance of arrhythmias, and conduction disorders under therapy.

Lead author biography

I was born on 8 May 1989 in Damascus, Syria. After completing my school education, I began studying human medicine at the Medical Faculty of Damascus University in September 2006 and graduated in September 2012. In February 2013, I got my professional license and started working as an resident doctor in the Clinic for Cardiology, Angiology and Internal Intensive Care Medicine at Klinikum Lippe in Detmold, Germany. On 7th September 2019, I was recognized as a specialist in internal medicine and cardiology. Since June 2021, I work as a junior consultant.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our colleague Prof. Dr med. Torsten Hansen (Institute für Pathologie, Klinikum Lippe GmbH) for his invaluable contribution.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding: None declared.

References

- 1. Basso C, Valente M, Poletti A, Casarotto D, Thiene G.. Surgical pathology of primary cardiac and pericardial tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997;12:730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hoffmeier A, Sindermann JR, Scheld HH, Martens S.. Cardiac tumors-diagnosis and surgical treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lestuzzi C. Primary tumors of the heart. Curr Opin Cardiol 2016;31:593–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H.. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer 2011;117:581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, Gasconye RD, Delabie J, Ott G. et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castrichini M, Albani S, Pinamonti B, Sinagra G.. Atrial thrombi or cardiac tumours? The image-challenge of intracardiac masses: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2020;4:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sarjeant JM, Butany J, Cusimano RJ.. Cancer of the heart: epidemiology and management of primary tumors and metastases. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2003;3:407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taguchi S. Comprehensive review of the epidemiology and treatments for malignant adult cardiac tumors. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;66:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patel R, Lim RP, Saric M, Nayar A, Babb J, Ettel M. et al. Diagnostic performance of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography in evaluation of cardiac and paracardiac masses. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saponara M, Ambrosini V, Nannini M, Gatto L, Astolfi A, Urbini M. et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT imaging in cardiac tumors: illustrative clinical cases and review of the literature. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2018;10:1–9. doi: 10.1177/1758835918793569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kraemer N, Balzer JC, Schoth F, Neizel M, Kuehl H, Günther RW. et al. Vorhoftumoren in der kardialen MRT. [Atrial tumors in cardiac MRI]. RoFo Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Rontgenstrahlen und der Bildgebenden Verfahren 2009;181:1038–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Mahony D, Piekarz RL, Bandettini WP, Arai AE, Wilson WH, Bates SE.. Cardiac involvement with lymphoma: a review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2008;8:249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ceresoli GL, Ferreri AJ, Bucci E, Ripa C, Ponzoni M, Villa E.. Primary cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients. Cancer 1997;80:1497–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Miguel CE, Bestetti RB.. Primary cardiac lymphoma. Int J Cardiol 2011;149:358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shah K, Shemisa K.. A “low and slow” approach to successful medical treatment of primary cardiac lymphoma. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2014;4:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oliveira GH, Al-Kindi SG, Hoimes C, Park SJ.. Characteristics and survival of malignant cardiac tumors. Circulation 2015;132:2395–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.