Abstract

Filial piety involves the Confucian view that children always have a duty to be obedient and to provide care for their parents. Filial piety has been described as both a risk and a protective factor in depression and suicide. This qualitative study aimed to explore the role of filial piety in the suicidal behavior of Chinese women. Qualitative interviews were conducted with Chinese women with a history of suicidal behavior living in the Beijing area (n = 29). Filial piety data were extracted and analyzed in accordance with constructivist grounded theory. The women described five specific family and filial piety factors and how they influenced their ability to fulfill family role obligations, which was described as a nexus connecting these factors to depression, suicidal behavior, and recovery. The five factors were: 1) rigidity of parental filial expectations, 2) perception of family relationships as positive/supportive or negative/harsh, 3) whether filial piety is of high or low personal value in the woman's life, 4) any experiences of rebellion leading to punitive consequences, and 5) how much filial piety she receives from her children. These factors could inform suicide risk assessments in this population. They can be harnessed as part of recovery and protect against future suicidal behavior.

Keywords: Filial piety, Chinese women, suicidal behaviour, qualitative, recovery

Introduction

Historically, China has carried a disproportionately high suicide burden compared to other countries (Phillips & Cheng, 2012). Importantly, suicide in Chinese communities has been construed as predominantly a social rather than psychiatric or psychological problem (Shiang et al., 1998). Gender in particular has been raised as an important factor in suicide deaths in China, with China having a higher proportion of female suicide deaths than most other countries (Law & Liu, 2008). One study of 244 female suicide attempters in China found that 87% of the participants reported interpersonal conflict as the cause (Li et al., 2012). Suicidal behavior in Chinese women has been characterized by high levels of impulsivity, low rates of mental illness, and little effort to isolate themselves before and after ingesting poison (Law & Liu, 2008; Pearson et al., 2002). These factors point to the importance of examining social and cultural factors in understanding differences in suicide patterns and rates.

Cultural meaning in suicide has been considered important in suicide research (Colucci, 2013). While cultural factors are not static and will influence suicidal behavior differently in different contexts and times, cultural considerations can allow for more nuanced understanding of suicide in local contexts relevant to developing and designing effective suicide prevention programs (Joe et al., 2008; Shropshire et al., 2008). “Gambling for qi” is an example of a cultural concept that can be relevant for understanding the meaning of suicide in certain Chinese communities (Fei, 2005). In a rural North China county, Fei (2005) found through fieldwork that “gambling for qi,” the idea of “winning dignity (qi) by behaving in an extreme way without carefully considering the risk” (p. 11), was one of the most popular explanations for suicidal behavior (Fei, 2005). In our qualitative study of Chinese women who immigrated to Canada, the Chinese Confucian value of “ren,” “consisting of harmony, self-discipline and endurance” (p. 44), or “putting up with sustained stress through civility and self-restraint” (p. 51), was found to be a primary coping strategy for emotional distress that led to worsening distress and suicidal behavior in our Chinese-Canadian female participants (Zaheer et al., 2016). Cultural understandings of suicide like the above examples can offer a richness and depth to identifying contributors to suicide, and how they complexly interplay with other factors, and thus provide a more accurate picture of how and why suicidal behavior occurs.

Filial piety is another documented Chinese cultural construct (Hwang, 1999). It is a Confucian concept that is deeply rooted and interwoven in traditional and contemporary Chinese culture (Hwang, 1999; Simon et al., 2014). Filial piety dictates that children are to be obedient, respectful, and responsible for providing sufficient emotional and financial support and care for their parents (Simon et al., 2014).

Several studies have explored the role of filial piety in the mental health of Chinese populations (Dong et al., 2017; Khalaila & Litwin, 2011; Li & Dong, 2018; Li et al., 2015; Ng et al., 2011; Pan et al., 2017; Simon et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2018). A strong belief in the importance of filial piety was associated with reduced depressive symptoms in caregivers (Khalaila & Litwin, 2011; Pan et al., 2017) and survivors of childhood abuse (Ng et al., 2011). However, filial piety can also increase the risk of mental illness and distress, such as in men who have sex with men who were diagnosed with HIV who felt they could no longer fulfill their filial procreative obligations to their parents (Li et al., 2015). For older adults, the perception of receiving more filial piety from their children was associated with a reduction in depressive symptoms (Wu et al., 2018) while lower expectations of receiving filial piety were associated with increased depressive symptoms (Li & Dong, 2018). Those with high expectations but low receipt of filial piety had the highest risk of depressive symptoms (Dong et al., 2017).

Fewer studies have examined the relationship between filial piety and suicidality. In a qualitative study of suicide attempters in Taiwan, participants described filial piety as protecting against recurrent suicidal behavior (Tzeng, 2001). Two studies of older Chinese adults found those who perceived more filial piety from their children had decreased suicidal ideation and attempts (Li et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2014). This finding is consistent with changing suicide patterns in China, where rapid social change and urbanization in China have been linked to increased suicide rates in older adults in rural areas hypothesized to receive less support as their children move to cities (Sha et al., 2017). Filial piety is a multidimensional concept with components that are differentially experienced in varying contexts. While there is some evidence that filial piety plays a role in suicidal behavior, the nature of this relationship is not well studied.

Qualitative research is important in suicide prevention because it can explore the meaning that individuals ascribe to suicidal experiences, leading to intervention targets in suicide prevention (Lakeman & Fitzgerald, 2008). Qualitative research is especially helpful in exploring the complex role of culture in suicide (Joe et al., 2008). The existing literature consists largely of quantitative studies of the association between mental illness and filial piety as a risk or protective factor. Explanatory models to help us understand why those associations exist are lacking.

This is the second qualitative study published in Western literature focusing specifically on women in China with a history of suicidal behavior and the first to use in-depth interpretivist analysis to create a model of suicidal behavior rather than enumerating risk factors (Li et al., 2012). This article is an analysis of the qualitative data focusing on filial piety as a mediator of risk for suicidal behavior in Chinese women.

Methods

Study overview

The findings from this article are part of a larger qualitative study that is a cross-national collaboration between the University of Toronto in Toronto and Tsinghua University in Beijing. The study's primary aim was to explore how Chinese-born women living in China and Canada understand and experience suicidal behavior, and how these conceptions and experiences were influenced by cultural and social constructions of gender (Lam et al., 2020; Zaheer et al., 2016). The Research Ethics Boards at Tsinghua University, St. Michael's Hospital, CAMH, and North York General Hospital approved the study. This article only examines the data from the Chinese component.

The qualitative interviews and analysis in this study were informed by constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Grounded theory is a qualitative research methodology that guides the systematic creation of theory rooted in data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Constructivist grounded theory is based on a relativist approach that recognizes multiple viewpoints and realities, taking a reflexive stance towards situations, participants, and actions (Charmaz, 2006). Constructivist grounded theory guidelines shape the study of social psychological processes, data collection, data analysis, and development of a theoretical explanatory model for the process being studied (Charmaz, 2003). Qualitative interviewing can provide an in-depth understanding of an aspect of life about which the interviewee has substantial experience and can elicit views of the person's subjective world (Charmaz, 2003).

Interviewers

Eight interviewers with training as psychiatrists working at a hospital at Tsinghua University (including co-author XZ) conducted the 29 interviews in Mandarin. Seven interviewers were women, with one man. They were all interested in qualitative and suicide research. The female interviewers expressed a particular interest in this research topic. They were all trained using structured and semi-structured qualitative interviewing skill programs. Seven of the eight trained psychiatrists were not part of the study team and did not receive authorship or any benefit from recruiting participants. It was clear in the protocol that psychiatrists were not to recruit or interview their own patients, or share information about study responses to the treating psychiatrist. The participants were made aware of the goals of the study prior to the interview and provided informed consent verbally and by signing the written consent form in simplified Chinese. It was clearly stated in the consent form that refusal to participate does not impact ongoing care, and this was reiterated verbally.

Participants and data collection

Twenty-nine Chinese-born women with a lifetime history of suicidal behavior receiving psychiatric assessment or ongoing psychiatric care in three hospitals that serve both rural and urban communities in Beijing and the surrounding area participated in this study. Participants were recruited from the Tsinghua University Yuquan Hospital, the Beijing Anding Hospital, and Junan Hospital. Participants were selected through purposive sampling and approached face-to-face and asked whether they would be interested in participating in the study. Two potential participants declined the interview but did not give reasons. Interviews occurred privately in the hospital setting. Inclusion criteria consisted of being born or raised in Mainland China, fluent in Mandarin, and 18 years of age or older. Suicidal behavior was defined as a self-inflicted, potentially injurious behavior for which there is evidence that the person either wished to use the appearance of intending to kill herself to obtain some end or intended to some undetermined or known degree to kill herself (Silverman et al., 2007). Exclusion criteria included active mania or psychosis, active substance intoxication or withdrawal, and significant cognitive impairment. Significant cognitive impairment refers in this study to not being able to understand or appreciate the risks and benefits to study participation. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were judged to be met based on responses from the demographic interview, the ability to demonstrate understanding of the consent process, clinical judgment of the interviewers since they were all psychiatrists, and review of the transcripts.

Each participant completed a semi-structured qualitative interview and a brief structured demographic interview. A semi-structured qualitative interviewing format allowed the interviewer and respondent to engage in a one-on-one informal interview. The interviewers used an interview guide that was informed by life history exploration and sensitizing concepts that related to gender, culture, and suicidal behavior (Zaheer et al., 2016). The interview guide was developed by the research team and had been used in the Canadian component of the study and adapted iteratively through meetings between the Canadian and Chinese study teams (Zaheer et al., 2016). The interviews each lasted between 30 and 90 minutes.

Data analysis

Qualitative interviews in China (n = 29) were audiotaped and occurred in the Mandarin dialect. The interviews were transcribed verbatim in Chinese and then translated into English by a professional translator. This translation was done because the three primary coders were not fluent in Mandarin and the team also wished to publish in English. The translations were reviewed by three Mandarin-speaking research team members to ensure proper interpretation. Complex or unclear transcript sections were reviewed by the research team and discussed regularly at the data analysis team meetings that occurred every two months until consensus was reached. Reference to the original Chinese transcripts by the coders, with support from Mandarin-speaking team members, also occurred regularly to clarify and contextualize unclear or complex transcript sections.

The transcripts were open coded substantively and procedurally. There were three coders (co-authors JL, RE, and JZ) and each transcript was coded by more than one coder. Memos were written immediately after open coding was completed and the coding and memos were reviewed and discussed by the research team. Memos were prepared that detailed the discussions of the research team meetings. Data were also entered into NVivo-9, an electronic text management and analysis software package designed to support a variety of research methods, including grounded theory. As data analysis proceeded, analytic memos were written iteratively to capture the major issues relevant to each code. Each transcript was coded at least two times during the data analysis process to ensure that earlier transcripts were examined for themes that developed through the process of serial memo-writing.

The team met every two months to work on data analyses and to ensure consistency in coding, compare analytic memos, explore emergent themes, and finally to construct larger theories and themes. Saturation was reached and confirmed by the three primary coders, meaning that new codes were not generated in the analysis of the data and the identified themes categorized the phenomena and explained relationships between concepts in a way felt to represent participant experiences. One transcript was excluded from analysis due to the participant having symptoms of active mania as interpreted by all members of the study team, and therefore meeting exclusion criteria, leaving 28 transcripts used in the analysis.

This article is an analysis of the data from the study. One of the codes and themes that emerged consistently was around filial piety and its role in mediating risk for suicidal behavior. All the codes and analytic memos around “filial piety” and “relationship with parents” were used in the analysis for this article. These codes were used for any segment of the transcript with the word “filial” in it, described duty to parents or children's duty to the participant, or described the participant's relationship to her parents. Any discrepancies on whether a code was appropriate were discussed amongst co-authors and resolved. There were multiple discussions of different themes and larger theories around filial piety that are incorporated in this article.

Results

Summary of participant characteristics

The participants had a mean age of 40.1 years (ranging from 19 to 67; standard deviation + /- 15.1 years). Half of the women (52%) were from urban Mainland China but five of the 14 women (36%) originally from rural China migrated to an urban area. Only 10% were married at the time of the interview. Approximately half of the women had children, with 21% having had more than one child. Thirty-one percent had less than high school education. Over a third (35%) were working, and three (10%) were retired and supported by social assistance. The majority (62%) lived in a home that they owned, with the rest of the women living in a parent-owned home (28%) or a college dormitory (10%). See Table 1 for more details.

Table 1.

Participant demographics (n = 29 Chinese participants).

| Number of participants (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Marital status | Married 3 (10) Divorced 11 (38) Single 15 (52) |

| Location of origin | Urban Mainland China 15 (52) Rural Mainland China 14 (48) Migrated from rural to urban 5 (36)a |

| Number of children | More than one child 6 (21) One child 9 (31) No children 14 (48) |

| Highest education level | No education 2 (7) Some school 7 (24) Completed high school 4 (14) Some college/university 5 (17) Completed college 4 (14) Completed university 7 (24) |

| Employment | Unemployed (s.s.) 3 (10) Unemployed (f.s.) 16 (55) Working 10 (35) |

| Housing | Living in own home 18 (62) Living in parent's home 8 (28) Renting college dormitory 3 (10) |

s.s. = social assistance support; f.s. = family support.a Percentage refers to the proportion of women from rural areas who migrated to urban areas in Mainland China.

Most participants had a clinical diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (69%), with 21% having Bipolar Disorder (Table 2). Most (62%) had had only one episode of suicidal behavior in their lifetime, with the majority (79%) having attempted suicide via overdosing or ingesting poison in the last 12 months. Most had 0 (41%) or 1 (41%) mental health hospitalization.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of participants (n = 29 Chinese participants).

| Number of participants (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Major Depressive Disorder | 20 (69) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 6 (21) | |

| Schizophrenia | 1 (3) | |

| Adjustment Disorder | 2 (7) | |

| Episodes of suicidal behavior (lifetime) | 10 + | 0 (0) |

| 5–9 | 2 (7) | |

| 2–4 | 9 (31) | |

| 1 | 18 (62) | |

| Frequency of suicidal behavior, by method (in the last 12 months)a | Overdose or ingesting poison | 23 (79), 25 (73) |

| Cutting or stabbing self | 5 (17), 5 (15) | |

| Asphyxia or smothering self | 2 (7), 2 (6) | |

| Burning self | 0 (0), 0 (0) | |

| Jumping from height | 2 (7), 2 (6) | |

| Number of mental health hospitalizations (lifetime) | 10 + | 1 (3.4) |

| 4 | 1 (3.4) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | |

| 2 | 3 (10) | |

| 1 | 12 (41) | |

| 0 | 12 (41) | |

Reported as the number of women who engaged in the behavior and total number of times behavior was reported.

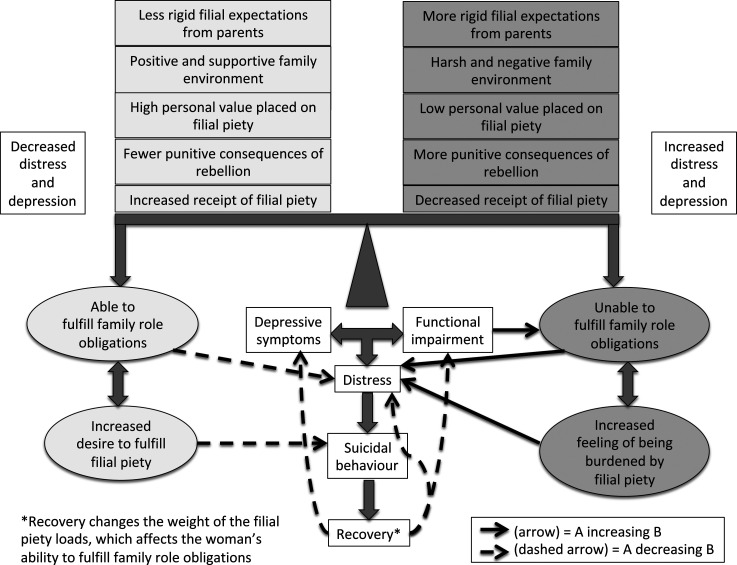

Filial piety data and model

Eight out of 28 coded interviews (29%) in the sample included “filial” or “filial piety” directly in the transcript. Twenty of the 28 transcripts (86%) had “filial piety” or “relationship with parents” data available for analysis, as determined by at least two co-authors for each transcript (JL, RE, JZ). The model of filial piety's role in suicidal behavior for the Chinese women (Figure 1) was created based on the coding data and connections described by the women themselves consistent with a grounded constructivist approach.

Figure 1.

Model of filial piety and family role obligations interacting with suicidal behavior and recovery.

Filial piety's role in suicidal behavior is conceptualized as a balance of factors that either increases or decreases a Chinese woman's ability to fulfill family role obligations as daughter and mother. The factors that affect a Chinese woman's ability to fulfill family role obligations include: 1) rigidity of parental filial expectations, 2) perception of family relationship as positive/supportive or negative/harsh, 3) whether filial piety is of high or low personal value in the woman's life, 4) experiences of rebellion leading to punitive consequences, and 5) how much filial piety she receives from her children. The ability to fulfill family role obligations reduced distress and was protective for suicidal behavior. Depressive symptoms and subsequent functional impairment increased the likelihood of being unable to fulfill family role obligations, which led to feeling more burdened by filial piety. The increased burden of filial piety and inability to fulfill role obligations increased depressive symptoms and created a vicious cycle of distress, ultimately contributing to suicidal behavior.

The time after suicidal behavior involved treatment for the women, and this is labeled as the “recovery” phase, although not every woman described improvement in their symptoms, distress, or function. Treatment reduced depressive symptoms, functional impairment, and distress, which improved the women's perceived ability to fulfill family role obligations. The weighting of filial piety and family factors also changed for the women after the suicidal behavior and shifted the balance of filial piety's role such that the women generally felt more able and willing to fulfill family role obligations, reducing distress and protecting against future suicidal behavior. However, some women described the shifting of the filial and family factors such that they continued to feel unable to fulfill family role obligations, which increased distress and did not protect against suicidal behavior. Each aspect of the model (Figure 1) will be explored below.

Family and filial factors decreasing ability to fulfill family role obligations

The women described family and filial piety factors that increased distress and decreased their ability to fulfill family role obligations. They described: 1) more rigid parental expectations for filial piety, 2) a harsh and negative family environment, 3) more punitive consequences of rebellion, and 4) decreased receipt of filial piety as contributing to their distress and inability to fulfill family role obligations. These factors increased distress, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment, contributing to suicidal behavior.

More rigid parental expectations for filial piety

Several women described how rigid filial expectations increased distress. One woman described a parental expectation of regular calls at exact dates and times: “They set up the date and time to call; you must call at that time, it's always like this.” These expectations increased distress, and her depressive symptoms made it more difficult to fulfill her filial obligations, so they became a burden for her, making her feel like she was failing her obligations:

[My parents] are so restricted and meticulous. Now I simply cannot meet this requirement because I do not have the energy. … They are old, they need to be taken care of by others. … I do not like that they wanted to hear from me. … I had to take care of them. I do not want to listen to these messages. … I did not do my best … as a daughter … also as a mother, I did not fulfill my responsibilities, so I feel like quite a failure.

Another woman described strict expectations of respect, explaining that she was not allowed to express any opinions so she stopped talking with her parents. A third woman's parents used an extreme method to prevent premarital sex: “My dad took me to do ultrasound every month. My dad scared me often. My dad said if you are not a virgin [the ultrasound] can tell. I think that's ridiculous.”

Harsh and negative family environment

Several women described growing up in a harsh and negative family environment, which was often linked to more rigid parental expectations of obedience. One woman described how her parents had seemingly nonsensical expectations of her and would physically abuse her when she did not meet those expectations:

I took my hat off and left it at grandma's home. Just because of that [my parents] beat me. … I think this was very unreasonable. … There was another time I particularly wanted to eat fried rice. I asked my mom to make it for me. She … did not want to make it. I was a kid and … asked again and again. She beat me for that.

Another woman described how her mother refused to talk to her for one entire semester in primary school if she did not rank highly enough in class: “… and she really did not talk to me for one semester. She was very cold.” She directly connected the way her parents treated her to experiencing distress and suicidal thinking.

More punitive consequences of rebellion

Several women described being distressed by the filial responsibility to obey their parents, but rebelling also led to punitive consequences, feelings of guilt, and further distress.

One woman described self-harming in rebellion: “[My mom] does not like my boyfriend. … I said: ‘If you keep nagging me, I’ll cut myself.’ She still nagged. Then I cut myself with a knife.” She later described using amphetamines and felt very guilty in being disobedient, increasing her distress.

One woman described how rebelling would have simply led to her parents being stricter: “The more rebellious you are, the more strict. We are all very traditional in my family.” She described how dating a woman felt like rebelling against her mom, so she ended that relationship:

I liked her a lot, but she is a girl. The reason I broke up [with her] was this. Walking on the street… I suddenly remembered that I still had to support my mom … if she was a boy then I would not be nervous … [but] no way [because] she is a girl …

Decreased receipt of filial piety

Some women described receiving less filial piety from their children as contributing to their distress. One woman described her son as disobedient: “He's not obedient and doesn’t work. He's had three relationships in three years. At last, he [has] no girlfriend.” She linked her worries to depressive symptoms, distress, and functional impairment: “The mood is bothering and bothering. I didn’t feel like cooking, eating, or talking.”

Depression leading to inability to fulfill family role obligations and suicidality

Several women made the connection between depressive symptoms leading to functional impairment and being unable to fulfill familial obligations. As one woman described:

From when I first got sick until now, for nearly a decade, I have brought the family so much pain, and haven’t make any contribution to the family, felt useless. Not any hope for life in the future … then you think of only negative things about yourself, and the future.

Another woman connected her depressive symptoms, the inability to fulfill her obligations, and suicidal ideation: “I feel no strength, [feel] inferior to others … I’m readily feeling tired when I have something to do. I just have the thought to end my life.”

Inability to fulfill family role obligations and feeling burdened by filial piety

As they became unable to fulfill their family obligations, the women described feeling burdened by these obligations. One woman wanted to relieve her children from the burden of having to be filial to her:

First, [if I die by suicide] I am liberated, I think the kids are also freed. The children do not have to miss you … every time when they go out for a few days … every day [they would not] have to call me asking me: “Mom, did you eat? How are you doing?” If you were dead … they would be relieved, why do they have to worry about such an old lady like you? You cannot help them. You make more mess …

Another woman described feeling unable to meet financial obligations for her child as the reason that she attempted suicide:

… the inner pressure was too high. So many years … [I] worked hard to save some money. After a few more years, the child will buy an apartment. I want to save the money … [but] the hope [to save up this money] seems not very big.

Distress leading to suicidal behavior despite family role obligations

Several women described how their distress was so great that filial and family role obligations could not stop their suicidal behavior. Four women described writing suicide notes prior to engaging in suicidal behavior and they all described failing in their filial obligations. One woman described:

When you read this suicide note, I may not be alive in this world. Then [the note was] saying that [I] the good child was not able to be filial, but I hope you will not be [experiencing] too [much] grief about it, [that it] will soon relieve the pain.

Another woman wrote suicide notes to multiple family members, communicating how her pain had reached a level that superseded her fear of causing them pain: “I did not care about the pain of others. I was really too painful.” A third woman left suicide notes to her parents and ex-husband. Her note to her parents explained that her depressive symptoms overcame her filial obligations: “The note for my mom and dad was, [it] just said I feel depressed, [I] do not want to live anymore, then I am sorry [I] could not be filial to you …”

The same woman asked her ex-husband to carry out her filial obligations after her death: “In the note I gave my ex-husband … I say you recognize my parents as your real father and mother. You would be filial for me. You take care of them until the end of their lives.”

Family and filial factors increasing ability to fulfill family role obligations

Many of the women described experiencing family and filial piety factors that decreased distress and increased their ability to fulfill family role obligations. They described having: 1) less rigid parental filial expectations, 2) a positive and supportive family environment, 3) a high personal value placed on filial piety, and 4) receiving more filial piety from their children as factors that reduced distress, increased their ability to fulfill role obligations, and were ultimately protective for suicidal behavior.

Less rigid filial expectations from parents

Several women described having less rigid filial expectations placed on them by their parents. One woman described feeling loved by her parents, who had less rigid filial expectations, providing her “great benefits”:

My mom and my dad both provided great benefits. We didn’t need to do chores at home. We must study hard, educate [ourselves] to develop well. Do not do bad things, go to Internet bar, [or] go to the disco. [They] would not allow us to go. Just grow well, get good education, study hard. No starvation, no suffering from coldness.

Positive and supportive family environment

Several women described experiencing a positive and protective family environment. Experiencing parental love and support was often associated with internalizing filial piety as an important value in their life. One woman described being raised to be “happy and lively” as a child and feeling spoiled by her father who would smile whenever he talked about her with others. This was connected to this woman's belief that her parents are the most important people to her: “… the only credible [people] in this world, the only people who love you, forever loyal to you, are your parents. Others’ commitments are just temporary …”

Another woman described how important her parents were to her. They cared for, comforted, and protected her when she was experiencing abuse from her husband:

I think the most important people to me are my parents. … [when my husband] was drinking that night … indeed he hit me … I was very, very disappointed, and then I … called my mother, saying I want to go home, you come pick me up. … during the two nights I stayed, my mother cooked lots of delicious food for me, making dumplings and other things. … I did feel well internally.

She later impulsively ingested pesticides in the context of her husband's treatment of her. She immediately called her parents to tell them that she was “not filial, would be filial to you in the next life.” It appears that experiencing positive parental care was protective for her chronic marital distress and suicidality only up to a point. It could not prevent an impulsive suicide attempt in the context of ongoing distress and abuse.

High personal value placed on filial piety

Several women incorporated filial piety as an important value in their lives. One woman described filial piety as a central tenet in her life, giving her a daily purpose:

I took care of my mom, because with [an] old mom and dad … [I] just wanted to take care of them when they are alive, so that they would not have regret when they leave. … when my mother was in the hospital, I’d been [there] with her …

Increased receipt of filial piety

Increased receipt of filial piety from children was described by some of the women as reducing distress and increasing desire to fulfill family role obligations. One woman described how her son took care of her at their family business and at home even when she asked him not to. She connects this to her desire to fulfill her role for him as mother and grandmother, which gives her purpose and a future to look forward to:

When my child gets married and gets a baby, needing us to do childcare, we would provide it. … [I have] just one child … [he] came every day these days … I never asked him to do chores at home, only asked him to study. But during the holidays, he started to do [his mother's work tasks]. … There was no person at home; [without him] I would not have time to tidy up, do washing, wipe the glass … If he did not come home, how could I have handled it? The child is very obedient, very honest.

Ability and desire to fulfill family role obligations decreasing distress and suicidal behavior

Several women described how being able to and wanting to fulfill family role and filial obligations was protective against suicidal behavior. One woman said, “… thinking about my mom, thinking about my son … then [I] didn’t do [the suicidal behavior].”

Two women described how thinking about their filial duty ended their suicide attempt after they had already taken the first steps. One woman described how she had hung herself and had marks on her neck but removed the rope because “I thought that I had to be alive to repay my parents.” The second woman talked about standing on the edge of a high-rise building's roof, but then remembered her parents:

At the very beginning I really wanted to die, but then I thought that even if my death reached the desired effect, it might not be compared with the pain of my parents in the rest of their lives. Therefore, I was determined not to die …

Recovery: Family and filial factors increasing the ability to fulfill family role obligations

In the “recovery” phase, not every woman described improvement in their symptoms, distress, or function. Recovery after suicidal behavior changed the role and weighting of the previously described filial piety and family factors in the women's lives (Figure 1). These changes shifted the balance so that the women generally felt more able and willing to fulfill family role obligations after suicidal behavior, which reduced distress and the likelihood of future suicidal behavior. As depressive symptoms were treated, the women described having less functional impairment and a corresponding increase in their ability to fulfill family role obligations.

Experiencing a more positive family environment during recovery

Several women described how experiencing positive family care after suicidal behavior affected their recovery. One woman described a positive shift after her suicidal behavior as her mother quit her job to care for her:

I think a mother should be like this, and should not be the same as before like a desperate hard worker. It turned out that she suddenly came home and began to cook. I felt that finally I have a mom.

Another woman described how her mother's care for her after suicidal behavior made her want to fulfill her filial duty, which reduced suicidality:

… when I woke up … she was just beside me accompanying me. … I felt so bad … I felt sorry for her. I would like to do things in return … since that time I attempted suicide I have never thought about suicide …

Increasing the personal value placed on filial piety in recovery

Immediately after suicidal behavior, some of the women described their parents trying to harness filial piety to reduce their future suicidal behavior. While she was being transported to hospital after ingesting pesticides, one woman remembers: “It seemed that my mom talked to me, saying ‘You don’t do it for anyone else, you just stay alive for your mom. If you pass away, your mom would die’; I heard this.” Several women discussed how suicidal behavior put their life into perspective, leading them to place more personal value on filial piety and family obligations, an important part of recovery for several women. One woman regretted her suicidal behavior, reflecting on her family responsibilities as reasons for living: “Even if I got the relief with suicide and death, still there are the family and child. … I have a lot of responsibility, I cannot just die freely. [I cannot be] so selfish. I have [a] father.” Another woman incorporated filial piety as a central part of her long-term recovery goals:

First [most importantly], [a person should be] kind, secondly filial to parents, and then … enjoy health. … For example … [being] filial to parents, [I] would not let them stay with me in the hospital [because it would be] too [much] suffering. [They would only have] a small bed to sleep in. [I am trying to] get discharged as soon as possible. [I] take every day seriously. Every day is a new day, a new beginning. [I am thinking positively;] all the best, I think like this.

A third woman talked about how her mental illness and suicidal behavior helped shift her priorities to what is truly important for her, centering on filial piety: “Now I want to cherish the current life, and be filial to dad and mom. That's my current state [of mind]. The state is very persistent …”

Fewer punitive consequences of rebellion in recovery

One woman connected recovery after suicidal behavior to a desire to be less rebellious and more filial:

I said: “Aunt, what kind of boyfriend I should look for?” “He should be rich, he should be able to support you.” I think I need to listen to the family, find someone capable. Listening to the words of the family makes sense.

Increased receipt of filial piety during recovery

Several women discussed how perceived receipt of filial piety was a protective factor in recovery after suicidal behavior. One woman linked her experience of filial piety from her children to a decrease in the likelihood of future suicidal behavior:

I just have the thought to end my life. But my children are good to me. Two sons, daughters-in-law, and grandsons all come to see me … they all treat me well. Yes, they will listen to me … as long as I have no cash, they will send some to me. The hospital deposit as well as the cost of living were [paid for by] my daughter. My son was coming here to bring me money.

Recovery reduced depressive symptoms and increased ability to fulfill family role obligations

Treatment of depressive symptoms reduced distress and functional impairment and increased several women's ability to fulfill filial obligations. As one woman explained:

I really regret [the suicide attempt]. I sent my dad a text message before coming to Beijing. I said, “You do not worry. I was unable to control my emotions, but the medicine was very helpful to me.” I have been calm these days.

Another woman described how psychiatric treatment saved her life and allowed her to re-engage with her filial obligations as a reason to continue living: “… thanks to these doctors, I was rescued; otherwise … it was a moment of weakness … my old father will be over 80 years old. I didn’t care about him, I was too selfish to [engage in suicidal behavior].” A third woman described how her increased desire to fulfill family obligations during recovery was protective for future suicidal behavior:

I thought of my dad and my family, and also if I die there are a lot of issues and no one would handle it. I have to continually stay at home, because I have elderly and little ones. So I cannot do it.

Several women described specific family role tasks as important goals of recovery, such as this woman: “I … really do not have a big goal. I just cook for them every day, for dad [and] when the child is back.”

Some participants highlighted the desire to fulfill obligations to children as an important reason for living after suicidal behavior. One woman said:

If I was dead [my son] would surely be worried to death, and he would definitely be sadder with such a mom not living up to expectations. In fact, I especially wish that he will get married and have children. I would do baby-sitting for them.

As another woman described after suicidal behavior, “Because there are children, there is a lot of hope.”

Recovery: Family and filial factors decreasing the ability to fulfill family role obligations

Although the majority of the participants described family and filial factors shifting in a positive direction during recovery, several women discussed how these factors did not improve or even worsened. This led to increased distress and risk for several of the women.

Experiencing a more negative family environment during recovery

One woman described how her family continued to act in a harsh and negative way towards her even after suicidal behavior, which she connected to feeling burdened by filial piety and worsening suicidality:

At first, [my mom] said she is glad to spend money to treat me, but in the end she started to blame my illness for costing her money … I tried to act like normal people and let my family think I am recovered. … They believed I was getting better. Actually, I was just performing that. There is a lot [of] responsibility on me. I must recover since they spent a lot of money. Thinking too much [about this] makes me want to die.

Decreased ability to fulfill family role obligations in recovery

Several women continued to experience distress and suicidality following suicidal behavior. They described ongoing symptoms and functional impairment that made them feel “useless” and unable to fulfill family role obligations.

Several women described their children no longer needing them as causing distress even after suicidal behavior. One woman described how she might reconsider suicide in future when her daughter no longer requires her to fulfill her role as a mother: “Sometimes I think to myself, [my] determination was not big enough [to die by suicide]. After two or three years, I think when my daughter's children are bigger, I will take some medicine quietly and pass away.”

Discussion

This is the first qualitative study specifically examining filial piety and suicidal behavior in Chinese women. The women in the study described family and filial piety factors that increased or decreased their ability and desire to fulfill family role obligations (Figure 1). Depressive symptoms increased functional impairment, which decreased several women's ability to fulfill family role obligations, increasing distress, which eventually led to suicidal behavior. Recovery, including treating depressive symptoms and greater family support after suicidal behavior, often changed the weighting of the factors described above. This generally shifted the balance towards increasing their ability and desire to fulfill family role obligations, reducing distress and suicidal ideation and behavior.

Our findings are consistent with existing literature on the relationship between filial piety and suicidal behavior. A previous qualitative study of male and female Taiwanese suicide attempters similarly found filial duty to parents as protective for suicidal behavior (Tzeng, 2001), although they did not analyze for any gender differences. Our study also confirmed previous findings that perceived receipt of filial piety from children can be protective for suicidality (Li et al., 2016; Simon et al., 2014). Our study uniquely connects how being the recipient of filial piety from children and practicing filial piety with parents can moderate suicidal behavior in the same individual. However, filial piety tended to play different roles in older and younger women's lives in this study. The younger women tended not to have had children at the time of the interview so receiving filial piety and fulfilling the role of mother were more often themes for older women in the study. For the younger women, being filial and fulfilling their roles as daughters were more common themes. The two women for whom the thought of filial duties to their parents ended their suicidal behavior midway were both in their 20s.

While some of these family and filial factors have been described in prior studies on suicidality in Chinese populations (Interian et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2017; Simon et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017), the women in this study described how the factors interact, including their ability to fulfill family role obligations as a nexus connecting these factors to depressive symptoms, suicidal behavior, and recovery.

This study highlights the need for more research on how factors related to filial piety and family support can potentially be harnessed to clinically address distress and suicidal behavior in Chinese women suffering from depression. Studies can perhaps test the validity of incorporating factors related to filial piety and family support as part of the suicide risk assessment. These risk factors for suicide in Chinese women could be added to existing suicide risk assessment tools, such as the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), which identifies a “supportive social network or family” and “responsibility to family” as protective factors and “perceived burden on family” as a risk factor (Interian et al., 2018), but does not identify culturally adapted nuances to these factors. Validity studies can assess the predictive validity of the C-SSRS for suicidal behavior in Chinese women including these factors compared to the scale without (Posner et al., 2011). Chinese women who describe rigid parental expectations of filial piety, a harsh or unsupportive family environment, low personal value placed on filial piety, painful consequences of rebelling against their family, and low perceived receipt of filial piety may have a higher suicide risk than women lacking some of these factors. Conversely, a suicide risk assessment of Chinese women could also include questions around inverse protective factors, some of which have been found to be helpful to foster in recovery in Chinese-Canadian women with suicidal behavior (Zaheer et al., 2019). The majority (86%) of the Chinese women in this study spontaneously discussed family factors and filial piety in their interviews, suggesting that these factors could improve the cultural adaptedness and clinical usefulness of the psychiatric assessment if confirmed in future studies.

The importance of family role obligations for Chinese women, specifically their sense of duty to their parents and children, and whether they feel able to fulfill those obligations, may be worth further examining. Qualitative studies with Chinese populations in different geographic regions in China and those of Chinese descent who live outside of China with a history of suicidal behavior could clarify whether these factors have resonance beyond this study. Future deductive qualitative analyses can focus on clarifying how family role obligations interact with suicidal behavior for Chinese women, particularly assessing for factors that have recently changed. These changes, such as recently feeling that their children no longer require them to fulfill their role as mother or feeling that filial piety is a burden they can no longer bear, seem to have increased the risk of suicidal behavior for the women in this study.

Suicide notes can offer important insights into the state of mind of a person attempting suicide (Furqan et al., 2018). Our study suggests that further research studying suicide notes left by Chinese women may yield important understanding. Qualitative studies of Chinese women's suicide notes can clarify themes that are important to women at increased risk of death by suicide (Furqan et al., 2018). The four women who described leaving suicide notes in our study all described failing in their filial obligations to their parents, describing how their distress and depressive symptoms overcame their desire to fulfill filial piety. Chinese women who leave suicide notes with such content may be at particularly high risk for suicidal behavior.

The women in this study discussed how filial piety and family factors were particularly important after suicidal behavior to foster recovery. They described how the filial and family factors shifted after suicidal behavior, and this can be an important time to target these factors for intervention. A novel psychiatric intervention focusing on harnessing filial piety and family role obligations as reasons for living could be developed and trialed against usual care, with measures of distress, depression, and future suicidal behavior as outcome measures. Treatment could involve the family, specifically having parents and children describe the importance of the participant's role in their family. Communicating one's value in the family was similarly found to be important in the recovery of Chinese-Canadian women with suicidal behavior (Zaheer et al., 2019). Education can be provided to families around how a positive supportive family environment and increased perceived receipt of filial piety can be protective for future suicidal behavior (Liu et al., 2017; Simon et al., 2014), combined with clinical efforts to apply these concepts to the specific family context. This is consistent with previous findings that family involvement in treatment of mental illness can be helpful in Chinese populations with severe mental illness (Chow et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2015) or suicidal behavior (Zaheer et al., 2019). The intervention can involve clinicians asking individuals how they define filial piety so that families can engage in tangible acts of filial piety. Women in this study described specific examples of filial piety that encompassed financial, emotional, and practical support.

The three-dimensional filial piety scale offers a framework and a measurement tool to assess filial piety and family role factors (Shi & Wang, 2019). This filial piety scale differentiates between “true filial piety,” which reflects genuine feelings towards parents, and “false filial piety,” where obedience is performed for secondary gain (Shi & Wang, 2019). The results of our study suggest that false filial piety may be associated with increased distress and suicidal behavior, with some women in this study describing a shift towards true filial piety during the recovery phase after suicidal behavior. This filial piety scale can be used in observational studies with Chinese individuals with suicidal behavior to measure this dimension of filial piety before and after suicidal behavior, and to correlate this measure with clinical outcomes such as likelihood of future suicidal behavior.

Another area of potential future research could be the development of a rating scale or assessment tool with specific items to evaluate an individual's perceived ability to fulfill their desired family role obligations. This measurement tool could be incorporated into existing clinical tools (Greer et al., 2010) and assessed for validity in correlating with depressive symptoms and suicidality. Several participants in our study described functional improvement and practical indicators of their ability to fulfill desired role obligations as reflecting their improvement over the course of their recovery. These factors, if inquired about as part of the individual's overall goals of recovery, could be evaluated regularly after suicidal behavior and be clinically useful in fostering recovery. This is consistent with a dimensional approach to recovery that moves beyond clinical recovery to a focus on recovery that encompasses functional, existential, and social recovery (Zaheer et al., 2019).

Limitations

The Chinese women in this study were living in and around the Beijing area at the time of the study. We would suggest caution in directly applying these findings to women in different regions of China or to Chinese women who have immigrated to other countries. However, several international studies suggest that filial piety is an important and deeply rooted cultural concept for Chinese populations both in different regions of China and who have immigrated outside of China (Chappell & Kusch, 2007; Hwang, 1999; Li & Dong, 2018; Simon et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019). We therefore believe that the findings in this study will have resonance and relevance beyond the specific participants in this study.

Relatedly, there are diverse ethnic groups in China for which it is unclear how factors described in this study might apply differentially. The structured demographic interview did not include specific questions around ethnicity so the sample cannot be described in terms of ethnicity.

Only 10% of the women were married in our sample, so their experiences may not represent married women who may also have had role obligations to parents-in-law and possibly pressures from a spouse to meet filial needs of parents-in-law (Lai et al., 2018). Filial duty to parents-in-law was not a theme that emerged in this study.

The women in this study have engaged in suicidal behavior, been diagnosed with a mental illness, and have come into psychiatric care. It is difficult to know to what extent our clinical sample represents women who would not have come into psychiatric care. However, several of the women in this study described attempting suicide impulsively, sometimes with high lethality methods, and sometimes they did not seek care but were found by family and brought to psychiatric care. This pattern of suicidal behavior seems to be representative of Chinese women who have died by suicide (Law & Liu, 2008) and suggests our sample is at least partly representative of Chinese women with suicidal behavior who would not have presented to care.

This study interviewed Chinese women who had suicidal behavior but did not die from suicide. While this may represent a somewhat different population from Chinese women who die by suicide, there is much evidence to suggest that having a history of suicidal behavior or suicide attempts with mental illness significantly increases the risk of later dying by suicide (Chung et al., 2017), so we believe this study was with a sample of Chinese women at increased risk of death by suicide. The risk and protective factors described by the women in this study therefore offer potential areas for intervention for suicide prevention in this population.

Finally, the interviews were conducted in Mandarin but the data were analyzed in English. This carries the risk of misinterpretation for some of the nuances and complexities that may have been lost in translation. However, this risk was minimized, as three Mandarin-speaking research team members were available to discuss complex or unclear transcript sections in the original Chinese transcripts until consensus was reached regarding interpretation.

Biography

June Sing Hong Lam, MD, FRCPC, is a Staff Psychiatrist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Canada. He is also a Lecturer in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Dr. Lam is currently a PhD student at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation at the University of Toronto. He is using quantitative and qualitative methodology to study access to mental health care for transgender individuals. His published works focus on health services research, transgender health, and cultural psychiatry.

Paul S. Links, MD, MSc, FRCPC, is a Professor with the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioural Neurosciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. When his research was initiated, Dr. Links was the holder of the Arthur Sommer Rotenberg Chair in Suicide Studies at the University of Toronto. This Chair was the first in North America dedicated to suicide research. Dr. Links continues to do research on suicide prevention and developing interventions for persons at high risk for suicide.

Rahel Eynan, PhD, is an Adjunct Research Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry at Western University and a Scientist at Lawson Health Research Institute. Dr. Eynan has quantitative and qualitative research methodological expertise and her current research at Lawson Health Research Institute continues to focus on suicidal behavior and suicide prevention. Dr. Eynan has published over 40 articles in scientific journals and book chapters, and co-edited and co-authored two books. Her published works focus on mental health and behavior disorders, psychosocial and clinical antecedents implicated in suicidal behavior, and evaluation of suicide prevention programs.

Wes Shera, MA, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work at the University of Toronto. He previously held academic positions at the University of Victoria and the University of Hawaii. From 1995 to 2002 he served as Dean of the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Toronto. Dr. Shera earned his master's degree in social welfare from the University of Calgary in 1975 and his doctorate in interdisciplinary social planning from Pennsylvania State University in 1982. His areas of teaching include community organization, social policy, groupwork, management, and social work policy and practice in the field of mental health. Dr. Shera's research focuses on operationalizing and testing concepts of empowerment in working with clients, organizations, and communities.

A. Ka Tat Tsang, PhD, is the Director of the China Project, and Professor at the University of Toronto's Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. His research interests include mental health and cross-cultural issues. He is currently the Principal Investigator for a study funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, “Exploring the Social Service Needs of Muslims in Ontario: A Community Based Partnership Approach,” which focuses on mental health services to women and youth. He is also a Co-Principal Investigator for a study funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, “Linking Hearts – Advancing Mental Health Care of University Students through Interdisciplinary Collaboration: An Implementation Research Project,” at universities in Jinan, Shandong, China. His published work covers a broad range of topics in mental health, human service, and cross-cultural issues.

Samuel Law, MDCM, MPH, FRCPC, is a Staff Psychiatrist and Associate Scientist at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, and Clinical Director of the Mount Sinai Hospital Assertive Community Treatment Team, Toronto. He is an Associate Professor, and Lead of the China Initiative at the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto. Dr. Law works, teaches, and researches on immigrant mental health, cross-cultural psychiatric services and international adaptation, and community-based psychiatric care with severely mentally ill populations.

Wai Lun Alan Fung, MD, MPhil, ScD, FRCPC, is the Medical Director of the Mount Sinai Hospital Wellness Centre at the University of Toronto Temerty Faculty of Medicine, which provides culturally sensitive and language-specific mental health services to Chinese-speaking seniors in Ontario, Canada. He is also a Research Professor at the Tyndale University in Toronto. Dr. Fung's academic interests and published works focus on the following areas: cultural and spiritual/religious dimensions of mental health and care; equity/diversity issues in mental health; neuropsychiatry and genetics; primary care mental health; mental health promotion; knowledge synthesis and mobilization; medical ethics; health professional education; interprofessional collaborations and education. He has served as Principal Investigator, Co-Principal Investigator, and Co-Investigator on numerous research grants spanning these areas.

Xiaoqian Zhang, MD, works at Tsinghua University, is Deputy Director of the Department of Psychiatry and Director of the Medical Division of Yuquan Hospital at Tsinghua University, Member of the Second Youth Committee of the Psychiatric Branch of the Beijing Medical Association, has 12 years of experience as a psychiatrist, and has 7,000 hours of psychotherapy experience in the field of dynamic psychotherapy. Dr. Zhang's main research directions are multi-modal research in suicidal behavior of adolescents and children, and cognitive function research in perioperative brain tumors in children.

Pozi Liu, MD, PhD, is a Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Yuquan Hospital, Tsinghua University in Beijing, China. His published works focus on neuroimaging, genetic, and suicide research related to mental illness in Chinese populations.

Juveria Zaheer, MD, MSc, FRCPC, is the Medical Head of Gerald Sheff and Shanitha Kachan Emergency Department and Clinician Scientist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto. Dr. Zaheer's research focuses on suicide and suicide prevention in diverse communities.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number CCI-109616) – C$84,096 in Canada and 538,000 RMB in China over two years (with two extensions). The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Ethics committee approval: Research ethics board approval for this study was obtained at St. Michael's Hospital (REB # 10-305), North York General Hospital (REB # 11-0155), CAMH (REB # 148-2012), and Tsinghua University (approved May 20, 2011).

ORCID iD: June Sing Hong Lam https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9797-4041

Contributor Information

June Sing Hong Lam,

Paul S. Links,

Rahel Eynan,

Samuel Law,

Wai Lun Alan Fung,

Pozi Liu,

Juveria Zaheer,

References

- Chappell N. L., Kusch K. (2007). The gendered nature of filial piety – A study among Chinese Canadians. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 22(1), 29–45. 10.1007/s10823-006-9011-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2003). Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. In Holstein J., Gubrium J. (Eds.), Inside interviewing: New lenses, New concerns (Chap. 15, pp. 311–330). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chow W., Law S., Andermann L., Yang J., Leszcz M., Wong J., Sadavoy J. (2010). Multi-family psycho-education group for assertive community treatment clients and families of culturally diverse background: A pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal, 46(4), 364–371. 10.1007/s10597-010-9305-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D. T., Ryan C. J., Hadzi-Pavlovic D., Singh S. P., Stanton C., Large M. M. (2017). Suicide rates after discharge from psychiatric facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(7), 694–702. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci E. (2013). Cultural meaning(s) of suicide: A cross-cultural study. In Colucci E., Lester D. (Eds.), Suicide and culture: Understanding the context (pp. 93–196). Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Li M., Hua Y. (2017). The association between filial discrepancy and depressive symptoms: Findings from a community-dwelling Chinese aging population. Journals of Gerontology – Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 72(11), S63–S68. 10.1093/gerona/glx040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei W. (2005). “Gambling for qi”: Suicide and family politics in a rural north China county. China Journal, 54(July), 7–27. 10.2307/20066064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furqan Z., Sinyor M., Schaffer A., Kurdyak P., Zaheer J. (2018). “I can’t crack the code”: What suicide notes teach us about experiences with mental illness and mental health care. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 1–9. 10.1177/0706743718787795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Strauss A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Greer T. L., Kurian B. T., Trivedi M. H. (2010). Defining and measuring functional recovery from depression. CNS Drugs, 24(4), 267–284. 10.2165/11530230-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang K.-K. (1999). Filial piety and loyalty: Two types of social identification in Confucianism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 163–183. 10.1111/1467-839X.00031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A., Chesin M., Kline A., Miller R., St. Hill L., Latorre M, Shcherbakov A., King A., Stanley B., (2018). Use of the Columbia-suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) to classify suicidal behaviors. Archives of Suicide Research, 22(2), 278–294. 10.1080/13811118.2017.1334610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S., Canetto S. S., Romer D. (2008). Advancing prevention research on the role of culture in suicide prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(3), 354–362. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalaila R., Litwin H. (2011). Does filial piety decrease depression among family caregivers? Aging and Mental Health, 15(6), 679–686. 10.1080/13607863.2011.569479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. C., Chen I. H., Miao N. F., Hsiao Y. L., Li H. C. (2018). An interesting phenomenon in immigrant spouses and elderly suicides in Taiwan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 74(January), 128–132. 10.1016/j.archger.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakeman R., Fitzgerald M. (2008). How people live with or get over being suicidal: A review of qualitative studies. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(2), 114–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04773.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam J. S. H., Links P. S., Shera W., Law S., Fung W. L. A., Tsang A. K. T., Eynan R., Zhang X., Liu P., Zaheer J. (2020). Lessons from a Canada-China cross-national qualitative suicide research collaboration. Global Public Health, 15(11), 1730–1739. 10.1080/17441692.2020.1771394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law S., Liu P. (2008). Suicide in China: Unique demographic patterns and relationship to depressive disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 10(1), 80–86. 10.1007/s11920-008-0014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Holroyd E., Lau J., Li X. (2015). Stigma, subsistence, intimacy, face, filial piety, and mental health problems among newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in China. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 26(4), 454–463. 10.1016/j.jana.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Xu L., Chi I. (2016). Factors related to Chinese older adults’ suicidal thoughts and attempts. Aging and Mental Health, 20(7), 752–761. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1037242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Dong X. (2018). The association between filial piety and depressive symptoms among U.S. Chinese older adults. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 4(July), 1–7. 10.1177/2333721418778167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Phillips M. R., Cohen A. (2012). Indepth interviews with 244 female suicide attempters and their associates in northern China: Understanding the process and causes of the attempt. Crisis, 33(2), 66–72. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. C., Chen H., Liu Z. Z., Wang J. Y., Jia C. X. (2017). Prevalence of suicidal behaviour and associated factors in a large sample of Chinese adolescents. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(3), 280–289. 10.1017/S2045796017000488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng R. M. K., Bhugra D., McManus F., Fennell M. (2011). Filial piety as a protective factor for depression in survivors of childhood abuse. International Review of Psychiatry, 23(1), 100–112. 10.3109/09540261.2010.544645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Jones P. S., Winslow B. W. (2017). The relationship between mutuality, filial piety, and depression in family caregivers in China. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 28(5), 455–463. 10.1177/1043659616657877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson V., Phillips M., He F., Ji H. (2002). Attempted suicide among young rural women in the People's Republic of China: Possibilities for prevention. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 32(4), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.32.4.359.22345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. R., Cheng H. G. (2012). The changing global face of suicide. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2318–2319. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60913-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K., Brown G. K., Stanley B., Brent D. A., Yershova K. V., Oquendo M. A., Currier G. W., Melvin G. A., Greenhill L., Shen S., Mann J. J. (2011). The Columbia-suicide severity rating scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha F., Yip P. S. F., Law Y. W. (2017). Decomposing change in China's suicide rate, 1990–2010: Ageing and urbanisation. Injury Prevention, 23(1), 40–45. 10.1136/injuryprev-2016-042006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wang F. (2019). Three-dimensional filial piety scale: Development and validation of filial piety among Chinese working adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–15. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiang J., Barron S., Xiao S., Blinn R., Tam W.-C. (1998). Suicide and gender in the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Chinese in the US. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35(2), 235–251. 10.1177/136346159803500204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shropshire K., Pearson J., Joe S., Romer D., Canetto S. S. (2008). Advancing prevention research on the role of culture in suicide prevention: An introduction. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(3), 321–322. 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman M. M., Berman A. L., Sanddal N. D., O’Carroll P. W., Joiner T. E. (2007). Rebuilding the tower of babel: A revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: suicide-related ideations, communications, and behaviors. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 37(3), 264–277. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. A., Chen R., Chang E. S., Dong X. (2014). The association between filial piety and suicidal ideation: Findings from a community-dwelling Chinese aging population. Journals of Gerontology – Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69(Suppl. 2), S90–S97. 10.1093/gerona/glu142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng W. C. (2001). Being trapped in a circle: Life after a suicide attempt in Taiwan. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 12(4), 302–309. 10.1177/104365960101200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Ho E., Au P., Cheung G. (2018). Late-life suicide in Asian people living in New Zealand: A qualitative study of coronial records. Psychogeriatrics, 18(4), 259–267. 10.1111/psyg.12318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. H., Chang S. M., Chou F. H. (2018). Systematic literature review and meta-analysis of filial piety and depression in older people. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29(4), 369–378. 10.1177/1043659617720266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer J., Shera W., Sing Hong Lam J., Fung W. L. A., Law S., Links P. S. (2019). “I think I am worth it. I can give up committing suicide”: Pathways to recovery for Chinese-Canadian women with a history of suicidal behaviour. Transcultural Psychiatry, 56(2), 305–326. 10.1177/1363461518818276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer J., Shera W., Tat Tsang A. K., Law S., Fung W. L., Eynan R., Lam J., Zheng X., Pozi L., Links P. S. (2016). “I just couldn’t step out of the circle. I was trapped”: Patterns of endurance and distress in Chinese-Canadian women with a history of suicidal behaviour. Social Science and Medicine, 160(July), 43–53. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Yang Y., Sun Y., Wu M., Xie H., Wang K., Zhang J., Jia J., Su Y. (2017). Characteristics of the Chinese rural elderly living in nursing homes who have suicidal ideation: A multiple regression model. Geriatric Nursing, 38(5), 423–430. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Clarke C. L., Rhynas S. J. (2019, Oct-Nov). What is the meaning of filial piety for people with dementia and their family caregivers in China under the current social transitions? An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Dementia (London), 18(7-8), 2620–2634. 10.1177/1471301217753775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Law S., Luo X., Chow W., Zhang J., Zhu Y., Liu S., Ma X., Yao S., Wang X. (2015). First adaptation of a family-based ACT model in mainland China: A pilot project. Psychiatric Services, 66(4), 438–441. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]