Abstract

Background/Objective

The Latin American population living with lupus lacks reliable and culturally competent health education resources. We describe a Spanish and Portuguese online program to educate Latin American people about lupus.

Methods

An extensive network of Latin American stakeholders participated in the program design, implementation, dissemination, and evaluation. Patients and rheumatologists selected core topics. Rheumatologists prepared the content using evidence-based data. Adaptations were conducted to meet the audience's health literacy and cultural values. Social media was used to post audiovisual resources and facilitate users' interactions with peers and educators, and a Web site was created to offer in-depth knowledge.

Results

The most massive outreach was through Facebook, with more than 20 million people reached and 80,000 followers at 3 months, between the Spanish and Portuguese pages. Nearly 90% of followers were from Latin America. A high engagement and positive responses to a satisfaction survey indicate that Facebook users valued these resources. The Spanish and Portuguese Web sites accumulated more than 62,000 page views, and 71.7% of viewers were from Latin American.

Conclusions

The engagement of patients and stakeholders is critical to provide and disseminate reliable lupus education. Social media can be used to educate and facilitate interactions between people affected by lupus and qualified health care professionals. Social media–based health education has extensive and scalable outreach but is more taxing for the professional team than the Web site. However, the Web site is less likely to be used as a primary education source by Latin American people because they value social interactions when seeking lupus information.

Key Words: health education, self-management, social media, systemic lupus erythematosus

Lupus is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by heterogeneous phenotypes with symptoms ranging from mild to life-threatening.1 Hispanics (people born or descendent of those born in Latin America, also called Latinos) have an increased susceptibility for lupus, compared with non-Hispanic whites.2,3 In Latin America, Mestizos (a racial mix between Europeans and Amerindians) with lupus are more likely to be younger at disease onset and have higher risk of lupus nephritis, cardiovascular disease, and more significant disease activity than whites with lupus.4–6 Similarly, Hispanics with lupus living in the United States have more severe disease and worse outcomes than their white counterparts.7–10 Biological, behavioral, and social factors can explain ethnic disparities in lupus outcomes.4,6,11 While delayed diagnosis and barriers to health care access are known factors leading to poor outcomes in lupus,11 a growing body of research suggests that health education also plays a significant role.12–14 Health education is critical to promote effective self-management in people with chronic diseases, including lupus.15–17 Although medical encounters are opportunities to educate patients, clinicians often face competing demands, lacking enough time to meet their patients' information needs. Consequently, the Internet has emerged as a widely used tool to seek information on lupus and exchange patients' experiences and knowledge with others.18,19

Internet and social media have scalable potential to disseminate public health education in Latin America. This large region is populated by more than 642 million people. In 2019, the Internet penetration in Latin America was 70%, and greater than 85% of Internet access was through social media, with Facebook accounting for 321 million users.20 Spanish, the predominant first language in Latin America, is spoken by nearly 60% of the population, Portuguese by nearly 30%,21,22 and the remaining 10% speak other languages. Lupus-specific education in Spanish and Portuguese is scarce, and most trustworthy online contents are direct translations from materials produced for English-speaking patients.23 Consequently, these resources are unlikely relatable to the needs and cultural values of the Latin American population. Moreover, as misleading information is abundant online, rheumatologists often discourage their patients from seeking health information on the Internet.24

To fill the gap of reliable and culturally competent health education for Latin American patients with lupus and their caregivers, we have developed an internet-based program in Spanish and Portuguese. The first phase of the Spanish program, named Hablemos de Lupus (Let Us Talk About Lupus), was launched in May 2017 through social media, followed by a Web site. One year later, the program was replicated in Portuguese, under the name Falando de Lúpus, to reach the Brazilian audience. This report provides an overview of the strategic approach and outreach of the Let Us Talk About Lupus program.

METHODS

Stakeholders

A key strategy of Let Us Talk About Lupus was the engagement of an extensive network of Latin American stakeholders firmly committed to the program's educational goals. Stakeholders and their roles are described below and summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Stakeholders Involved in Let Us Talk About Lupus

| Stakeholder Category | Role |

|---|---|

| GLADEL members (rheumatologists) n = 219 | Selection of topics, preparation of contents, dissemination, live video chats with an expert |

| Scientific associations | Dissemination |

| PANLAR | |

| The Lupus Initiative | |

| Argentinian Society of Rheumatology | |

| Peruvian Society of Rheumatology | |

| Brazilian Society of Rheumatology | |

| Patients and patients' organizations from: | Selection of topics, review of contents, dissemination |

| Argentina | |

| Bolivia | |

| Chile | |

| Colombia | |

| El Salvador | |

| Mexico | |

| Paraguay | |

| Community management team (GLADEL rheumatologists) n = 6a | Educational interaction with social media users, formative evaluation |

| Production team | Production of resources, formative evaluation |

| Communication manager | Monthly newsletter |

aFour members in the Spanish and 2 in the Portuguese teams, respectively.

Latin-American Group for the Study of Lupus

The Latin-American Group for the Study of Lupus (GLADEL) is a consortium of more than 200 rheumatologists from 12 Latin American countries with the mission of advancing lupus research and education in Latin America.4 Members of GLADEL collaborated with the content, community management, and dissemination of this program, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A267.

Scientific Organizations

The program was launched with the support of both ILAR and PANLAR (the International and the Pan American League of Associations of Rheumatology, respectively). These organizations are dedicated to raise awareness about rheumatic diseases and provide teaching and scientific resources to health care professionals and patients in their regions. Moreover, national scientific societies, including the Lupus Initiative, a branch of the American College of Rheumatology, and analogous organizations in Argentina, Brazil, and Peru, contributed to the program dissemination.

Lupus Patients

Individual patients and lupus patients' organizations from Latin American countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico, and Paraguay, participated in the selection of topics, cultural competency, and dissemination of the program. Moreover, an Argentinean lupus patient has served as the administrator of a closed Facebook group named Amigos de Hablemos de Lupus (Let Us Talk About Lupus' Friends), which was developed to respond to the needs of the Spanish-speaking audience.

Community Management Team

A team of junior rheumatologists (Y.F.-S., S.I., C.R.-S., C.E.-F., L.P.C.S., E.T.R.-N.) was recruited from GLADEL and trained to leverage Facebook users' comments as opportunities to educate about lupus without engaging in personalized diagnosis or treatment recommendations. A repository of frequent questions and standard answers was created to address the most common questions and comments quickly and effectively. Moreover, the team regularly monitors audience's comments to eliminate unreliable or malicious information.

Production Team

The program strategy was developed by a social communicator with expertise in social media. A graphic designer is involved in the creation and production of audiovisual resources. The contents created by lupus experts have been edited by a copywriter to ensure a friendly style and suitable health literacy of the Web site contents.

Intended Audience

Research conducted by GLADEL among the Latin American population with SLE suggests that being young, female and of low socioeconomic level are risk factors for active disease, poor quality of life, and short life expectancy.4,11 Therefore, the primary intended audience was defined as Spanish- or Portuguese-speaking women with lupus, aged 18 to 45 years, and educational attainment high school or less.

Core Topics

We conducted a 3-step process to select core topics. First, 2 Latin American rheumatologists (C.D. and B.A.P.-E.) with vast experience in lupus management and patient education created a list of topics. The list was then distributed among 6 patients and caregivers who serve as lupus community leaders in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico, and an PhD educator of a large Hispanic population with lupus in Chicago. Topics were independently ranked by relevance, and additional topics were suggested. Twenty-five topics were selected and classified into 2 categories: (i) learning about lupus (information about the disease) and (ii) living with lupus (coping, self-management challenges, and strategies to overcome those challenges) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Core Topics Selected by Stakeholders

| Learning About Lupus | Living With Lupus |

|---|---|

| What is lupus? | Lupus, emotions, and stress |

| Lupus in diverse populations | Lupus and pain |

| Lupus in men | Lupus and fatigue |

| Flares and remission | Lupus and physical exercise |

| Lupus and skin | Lupus and nutrition |

| Lupus and osteoarticular system | Lupus, family and friends |

| Lupus and respiratory system | Lupus in children and adolescents |

| Lupus and cardiovascular system | Caring for people with lupus |

| Lupus and kidneys | Support groups |

| Lupus and nervous system | Participation in research studies |

| Lupus and pregnancy | |

| Lupus and vaccines | |

| Lupus and infections | |

| Medications frequently used in lupus | |

| New agents to treat lupus |

Content Development

The content of most core topics was written by rheumatologists utilizing evidence-based information and adhering to standard medical best practices. Two topics (caring for people with lupus and support groups) were developed by leaders of lupus patients' organizations. The content was further adapted by a rheumatologist (C.D.) and a communicator to create the scripts for the animated videos and other social media resources. The content was also used to build the Spanish Web site. A copywriter reviewed the content to unify the narrative style and ensure that the health literacy would be appropriate for a lay Latin American person with an educational attainment of high school or less. The Web site content was further translated to Portuguese (Brazil) and reviewed by Brazilian stakeholders (L.P.C.S, E.T.R.-N., E.B., E.I.S.) for language accuracy and cultural suitability.

Social Media Content Strategy

Social media resources were created to accomplish specific educational objectives, as follows:

Educational videos: Animated videos of 3 to 5 minutes length are produced to educate on the core topics by illustrating specific aspects of the disease through relatable characters and scenarios.

Reinforcement albums: Photo albums reinforce the main points of previously posted videos or further explain a complex concept present in videos.

Self-management tips videos: Shorter (1–3 minutes long) animated videos are focused on the challenges of living with lupus and self-management strategies. As these videos are related to the experiences of those living with lupus, they also serve to inspire patients, family members, caregivers, and friends to comment and share their own experiences.

Live video chats with a lupus expert: Monthly live video chats are broadcasted in Spanish via Facebook by qualified professionals. These resources offer the audience the opportunity to ask questions via chat and obtain live answers from the expert. Topics are selected to address the audience's preferences and reinforce previously published topics, offering people an opportunity to clarify doubts. Video chats remain posted for those who are not available for the live stream. Moreover, since November 2020, the live video chats have been streamed via YouTube and archived in a specific public playlist.

Facebook closed group in Spanish: A closed Facebook group was created to address the audience's needs for a safe space where members can share experiences and foster peer support. The group named Amigos de Hablemos de Lupus (Let Us Talk About Lupus Friends) is administered by a patient leader who monitors members' comments ensuring that the group rules are respected.

Social Media Content Quality and Monitoring

In addition to manual monitoring of comments by the community management team, automatic filters were introduced in the Facebook and YouTube settings to prevent the publication of commercial spams and inappropriate comments.

RESULTS

Social Media Outreach and Engagement

Let Us Talk About Lupus has used Facebook as the central platform to offer a continuous stream of information through animated videos and facilitate interactions between the audience and the education team. Users have the opportunity to post comments and questions and receive feedback from educators. The Spanish page (Facebook/Hablemos de Lupus) was launched on May 5, 2017, followed by the Portuguese page (Facebook/Falando de Lúpus) on May 6, 2018. The first video in Spanish, entitled “What is lupus?” was viewed for at least 3 seconds by 4,179,921 unique users within the first 3 months, and 588,956 unique users watched the video at 95% of its length during the same period.

Facebook's outreach indicators throughout the first 90 days from the launch date are depicted in Table 3. The total number of people who saw the posted materials in the first trimester reached 18,511,763 for the Spanish page and 551,077 for the Portuguese page. On the Spanish page, videos posted in the first trimester were viewed 5,604,905 times for at least 3 seconds and 1,254,526 times for at least 95% of its length. Videos posted on the Portuguese page were viewed 161,168 and 25,307 times for at least 3 seconds and 95% of its length, respectively. The cumulative number of followers (people who opted to follow the page to receive updates in their timelines) reached 64,434 and 15,917 for the Spanish and the Portuguese pages, respectively. Despite the Portuguese page's lower outreach, its engagement rates were relatively higher for all indicators, except for the number of shares over the number of video watches at 95% (Table 4). Education and engagement were further fostered through monthly live video chats with lupus experts. From July 4, 2017, throughout November 5, 2020, the Facebook page in Spanish delivered 31 live video chats, achieving an average of 293.8 live viewers and 591.5 live comments per session (Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A266). The single most popular video chat was on the topic COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) and lupus, with 1101 live viewers, 4233 likes, and 1143 comments.

TABLE 3.

First-Trimester Metrics of the Spanish and Portuguese Facebook Pages

| Facebook Metric | FB/Hablemos de Lupus,a n | FB/Falando de Lúpus,b n |

|---|---|---|

| People reacheda | 18,511,763 | 551,077 |

| Total video viewsb | 5,604,905 | 161,168 |

| Video watches at 95%c | 814,181 | 25,307 |

| People engagedd | 1,254,526 | 44,587 |

| Sharese | 243,325 | 6,075 |

| Likesf | 338,336 | 15,891 |

| Commentsg | 25,841 | 2,380 |

| Followersh | 64,434 | 15,917 |

Metrics are estimates provided by Facebook for the first trimester since each page was launched.

aLet Us Talk About Lupus in Spanish, launched on May 5, 2017.

bLet Us Talk About Lupus in Portuguese, launched on May 6, 2018.

cTotal number of times the videos were watched at 95% of its length.

dTotal number of unique users engaged in certain ways with a post (e.g., by commenting on, sharing, or clicking upon particular elements of the post).

eTotal number of times users shared a post with other people.

fTotal number of times users liked a post.

gTotal number of times users commented a post.

hTotal number of unique users who have chosen to “follow” the page to receive updates in their timeline.

FB indicates Facebook.

TABLE 4.

First-Trimester Engagement of the Spanish and Portuguese Facebook Pages

| Engagement Rate | FB/Hablemos de Lupus,a % | FB/Falando de Lúpus,b % |

|---|---|---|

| Video watches at 95%c/total video viewsd | 14.5 | 15.7 |

| People engagede/people reachedf | 6.8 | 8.1 |

| People engagede/total video viewsd | 22.4 | 27.7 |

| Sharesg/video watches at 95%c | 29.9 | 24.0 |

| Likesh/video watches at 95%c | 41.6 | 62.8 |

| Commentsi/video watches at 95%c | 3.2 | 9.4 |

| Followersj/people reached2 | 0.35 | 2.89 |

Engagement rates were calculated for the first trimester since each page has been launched, using metrics provided by Facebook.

aLet Us Talk About Lupus in Spanish, launched on May 5, 2017.

bLet Us Talk About Lupus in Portuguese, launched on May 6, 2018.

cTotal number of times the videos were watched at 95% of its length.

dTotal number of times the videos were viewed for more than 3 seconds.

eTotal number of unique users engaged in certain ways with a post (e.g., by commenting on, sharing, or clicking upon particular elements of the post).

fTotal number of unique users reached through the posts.

gTotal number of times users shared a post with other people.

hTotal number of times users liked a post.

iTotal number of times users commented a post.

jTotal number of unique users who have chosen to “follow” the page to receive updates in their timeline.

FB indicates Facebook.

As of November 5, 2020 (40 months since launched), the Spanish page has gathered 89,627 followers. Of them, 79,575 (88.8%) were from Latin American countries and the rest from the United States (n = 4,928; 5.5%), Spain (n = 3,607; 4.0%), and other countries around the world (1,517; 1.7%). With 30 months online, the page in Portuguese has gathered 16,823 followers, with 15,015 (89.3%) from Brazil, 841 (5.0%) from Portugal, 182 (1.1%) from other Latin American countries, and the remaining 785 (4.6%) from the rest of the world. The majority of followers were females: 89% for the Spanish-language page and 94% for the Portuguese-language page. Followers' ages ranged from 13 to older than 65 years, with 71% and 78% between 25 and 54 years old for the Spanish- and Portuguese-language pages, respectively.

YouTube

Unlike Facebook and Twitter, YouTube does not prioritize “novelty” or engagement. Consequently, YouTube has been used as a hub of information for followers and newcomers alike, allowing the audience to browse and watch specific videos easily. The playlists, grouped in the 2 main categories (“learning about lupus” and “living with lupus”), compile all animated videos published on Facebook. As of November 5, 2020, the YouTube channel in Spanish has gathered 7940 subscribers and 1,631,832 video views, whereas the channel in Portuguese has gathered 1380 subscribers and 73,132 views.

We have used this channel to post new videos and send traffic to our Facebook and YouTube, which are the main channels where the audience can either interact with lupus educators or browse specific content. As of November 5, 2020, the Spanish and Portuguese platform have gathered 5328 and 1371 subscribers, respectively.

Website Overview and Outreach

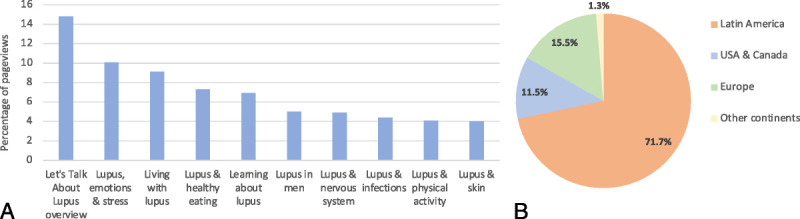

Two Web sites, one in Spanish and another in Portuguese (Brazil), offer a deeper level of information about the core topics listed in Table 2. A friendly navigation design was created to help inexperienced internet users explore 2 major categories of contents (learning about lupus and living with lupus). Texts were enhanced with visual aids and animated videos to facilitate comprehension among low-literacy individuals. Both Web sites were connected to our social media channels, which in turn were used to promote and disseminate the Web sites. The Spanish Web site (www.hablemosdelupus.org), launched in October 2018, reached a total of 36,683 visitors with over 60,500 page views by November 5, 2020. The Portuguese Web site (www.falandodelupus.org), launched on May 8, was visited by 795 individuals and accumulated 1673 page views as of November 5, 2020. The Figure depicts the top 10 topics and visits locations for the Web site in Spanish.

FIGURE.

Spanish Web site (www.hablemosdelupus.org) page views by topic and unique visitors by location between October 2018 and November 2020. A, Bars indicate the percentage of the top 10 page views by topics among a total of 60,500 page views. B, Pie sections indicate the percentage of unique visitors by region (total unique visitors = 36,683). Data provided by the Squarespace analytics.

Dissemination

Stakeholders have contributed substantially to the dissemination of resources posted throughout the online platforms. The American College of Rheumatology has linked animated videos of Let Us Talk About Lupus to its Lupus Initiative Web site. Similarly, Web sites of several scientific and lupus patients' organizations in Latin America have created links to our platforms and streamed our live video chats through their own channels.

Evaluation

We focused our evaluation on Facebook because it is the platform with the most massive outreach, offering us the opportunity to assess thousands of organic comments on users' perspectives and unmet needs concerning the disease and the information provided through our resources. The community management team has met monthly for the first year and then, as needed, to discuss user's comments, select other topics, and better tailor resources to the audience. Additionally, 6 months after the Spanish page was launched, we evaluated users' satisfaction through an online survey. Among 952 respondents, 763 (80.1%) agreed and 162 (17.0%) somewhat agreed with the statement that the program helped them to better understand lupus, whereas 18 (1.9%) were neutral, and the remaining 9 (1%) either disagreed or somewhat disagreed. Participants reported that the most helpful resources were the animated videos (46.1%), followed by the live videos with experts (27.3%), the comments posted by the community management team (15.1%), and the peers' comments (11.5%).

Sustainability

Let Us Talk About Lupus is a low-budget program supported with small grants and built on its stakeholders' in-kind contributions. Social media accounts are free, and we do not incur additional costs to stream the live video chats; thus, most of the budget is assigned to the production of new animated videos. Moreover, our existing video library includes nearly 90 animated videos in 2 languages, which can be updated at a low cost and recirculated. Consequently, the program can be financially sustained by small institutional contributions or donations by partner organizations. The time devoted by the community management team to address users' comments is minimized by using our repository of standard responses or redirecting users to previous videos. Moreover, GLADEL encompasses an extensive network of junior rheumatologists with the potential of training additional community management teams, ensuring the self-sustainability of this component of the program.

DISCUSSION

Let Us Talk About Lupus is a comprehensive online program aiming to educate the Latin American population living with lupus. Facebook has been the primary channel to deliver lupus educational resources in Spanish and Portuguese. The Spanish page achieved an extraordinary organic outreach of over 18 million people in the first trimester, indicating that the Facebook audience was eager to learn more about lupus. Additionally, the level of users' satisfaction was very high at 6 months, suggesting that our program filled a critical information gap in this population.

Facebook followers receive the content as it is posted to progressively build their knowledge. Moreover, as Facebook offers openings for social interaction,25,26 we leveraged audience's comments as opportunities to provide tailored information. Thus, a community management team of rheumatologists has played a critical role in addressing users' questions on a regular basis, offering evidence-based information, and encouraging patients to discuss their concerns with their health care providers. Moreover, we found users' commentaries to be valuable resources to conduct formative evaluation about the education needs that remain unmet and how to adapt the contents to the audience's health literacy.27,28 Additionally, users can interact with lupus experts through the live video chats and each other through a closed group administered by a lupus patient and supervised by the program director (C.D.) within the open page.

The Portuguese page outreach (551,000 people in the first trimester) was lower than the Spanish page, which can be partially explained by the relatively lower Portuguese-speaking population (225 million people) compared with the Spanish-speaking population (470 million people) in Latin America. Moreover, in January 2018, shortly before we launched the Portuguese page, Facebook changed the reach algorithm, prioritizing users' engagement over post views.29 The algorithm change may have had a negative impact on the short-term outreach; however, it may have also contributed to the relatively higher engagement among Portuguese-speaking, compared with Spanish-speaking users of our Facebook pages.

The rate of engagement on reach (likes, comments, clicks, and shares divided by people reached) was very high in both Facebook pages, with a 3-month average of 6.8% and 8.1% for the Spanish and Portuguese pages, respectively. Data from 2810 business Facebook pages reported an average engagement on reach of 0.09% globally.30 Our higher estimates suggest that the Latin American population living with lupus has found in our Facebook pages the opportunity to join a safe community where users can express themselves, ask questions to qualified professionals, and open discussions about lupus with their peers. Unique assets of our program are the live video chats with a lupus expert and the community management by a team of rheumatologists. The monthly live video chats have engaged an average of 293 live participants per session, offering the opportunity for a direct dialogue about specific topics between people located in remote places and an experienced health care professional. These sessions are also leveraged to offer timely interventions, such as the live video chat about COVID-19 and lupus, which was the single most popular one, with more than 4000 likes (Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A266).

Secondary choices on lupus information among Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking people were YouTube and the Web site. YouTube's search functionality is suitable for people looking for specific information, allowing them to find relevant videos without the commitment of interacting with a large community. As YouTube has recently become accessible via a smartphone, the outreach through this channel has been growing consistently. However, the number of subscribers to our YouTube channels is still far below the number of followers amassed on Facebook. Similarly, Web site visitors were relatively low compared with Facebook, despite the attractive audiovisual resources, the friendly navigation tool, and the social media connectivity offered in our Web sites. A recent report indicated that Latin American patients with rheumatoid arthritis preferred the audiovisual format for Web site content.31 Moreover, a US study suggests that social media is the most efficient approach to disseminating information about a Web site center among cancer patients.32 The relatively higher Latin American outreach (nearly 90% followers) via Facebook, compared with the Web site (71.7%), along with the high Facebook engagement, suggests that when Latin Americans select health information tools, they also value interactions with peers and providers, information sharing, and social support.33

A fundamental strategy of our program was the engagement of an extensive and committed network of Latin American stakeholders, including patients, rheumatologists, and other health care providers, patients' organizations, and experts in communication, graphic design, and literacy. Members from the GLADEL group compiled evidence-based information about topics selected by both rheumatologists and lupus patients to create the core content. Audiovisual materials, available in Spanish and Portuguese, were produced to be relatable, easy to understand, and broadly accessible through social media and a Web site. All stakeholders have been fully engaged in disseminating and promoting the contents among the lupus community and the general public.

Our program has limitations. It demands time commitment by the production and community management teams and multiple stakeholders to reach out and engage a broad audience. Moreover, we could not directly measure if our educational resources lead to increased knowledge or behavioral change. We were unable to statistically compare the metrics between the Spanish and Portuguese pages because in 2018 Facebook changed its outreach algorithm substantially,29 and comparative results might be misleading.

In conclusion, leveraged on the worldwide Internet and social media accessibility and the commitment of an extensive network of stakeholders, Let Us Talk About Lupus offers reliable and culturally competent health education to the massive Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking population living with lupus worldwide. Latin American patients with lupus and their allies prefer the combined learning and social interactions offered by social media channels over single learning resources via a Web site.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our social media–based program offers various opportunities for safe community building and health dialogues between patients and health care professionals, serving as an innovative education model for other rheumatic conditions. However, further evaluation is needed to determine whether users have a more active role in their self-management activities, including communication with their providers and shared decision-making. Moreover, further assessment is warranted to determine whether the program reaches socioeconomically disadvantaged populations and inform potential differences between those from urban versus rural areas. Taking advantage of these high-reach, low-cost platforms, we are now conducting quantitative and qualitative research to advance our understanding of patients' beliefs, health care needs, and challenges in managing the disease by sociodemographic characteristics.34–36

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all members of GLADEL and PANLAR, as well as lupus patients' organizations, scientific organizations, health care professionals, and individual patients for their important role in various programmatic activities, including the preparation of contents, participation in the live video chats, and dissemination of educational resources. They also thank María Celeste Eberhardt for her guidance in the strategic approach, María Laura Hita for her work as designer and producer, Marcela Santamaria Long and Mercemari Toyens-Nieves for their voiceover production, Ana Paula Ayanegui for reviewing and editing the Web page content, and Cecilia Barbarita Zegray for her work as the administrator of the closed Facebook group “Amigos de Hablemos de Lupus.” They also acknowledge Teresa Cattoni (from ALUA, the Argentinean Lupus Association), Gonzalo Tobar-Carrizo (from Lupus Chile), and Gina Ochoa (from FUNDARE, a Colombian foundation to support the rheumatic patient) for preparing the content of some of the Web site topics and their participation as expert patients in our live video chat sessions.

Footnotes

The Spanish and Portuguese versions of the Let's Talk About Lupus Program (Hablemos de Lupus and Falando de Lúpus) received financial support from the International League of Associations for Rheumatology, the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology (PANLAR), and Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Role of the Program Sponsors: PANLAR participated in the dissemination of Let's Talk About Lupus. GSK had no role in the program design, implementation, selection of contents, or any other operational aspect of the program. GSK had no role in the preparation or approval of this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jclinrheum.com).

Contributor Information

Yurilis Fuentes-Silva, Email: yurilisfuentes@gmail.com.

Luciana Parente Costa Seguro, Email: lucianapc@gmail.com.

Edgard Torres dos Reis-Neto, Email: edgardtr@hotmail.com.

Soledad Ibañez, Email: leonorsi@yahoo.com.ar.

Claudia Elera-Fitzcarrald, Email: claudiaelerafitz@gmail.com.

Cristina Reategui-Sokolova, Email: cristina.reateguis@gmail.com.

Fernanda Athayde Linhares, Email: fernanda.atcl@hotmail.com.

Witjal Bermúdez, Email: witjalbm@infomed.sld.cu.

Leandro Ferreyra-Garrot, Email: leandro.ferreyra@hospitalitaliano.org.ar.

Carlota Acosta, Email: carlota.acosta@gmail.com.

Carlo V. Caballero-Uribe, Email: carvica@gmail.com.

Emilia Inoue Sato, Email: eisato@unifesp.br.

Eloisa Bonfa, Email: eloisa.bonfa@hc.fm.usp.br.

Bernardo A. Pons-Estel, Email: bponsestel@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wallace DJ, Hahn B, Dubois EL. Dubois' lupus erythematosus. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkin; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dall'Era M Cisternas MG Snipes K, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in San Francisco County, California: the California lupus surveillance project. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:1996–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Izmirly PM Wan I Sahl S, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in New York County (Manhattan), New York: the Manhattan lupus surveillance program. Arthritis Rheum. 2017;69:2006–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pons-Estel GJ Catoggio LJ Cardiel MH, et al. Lupus in Latin-American patients: lessons from the GLADEL cohort. Lupus. 2015;24:536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pons-Estel BA Catoggio LJ Cardiel MH, et al. The GLADEL multinational Latin American prospective inception cohort of 1,214 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: ethnic and disease heterogeneity among “Hispanics”. Medicine. 2004;83:1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seldin MF Qi L Scherbarth HR, et al. Amerindian ancestry in Argentina is associated with increased risk for systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2008;9:389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgos PI McGwin G Jr. Pons-Estel GJ, et al. US patients of Hispanic and African ancestry develop lupus nephritis early in the disease course: data from LUMINA, a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA LXXIV). Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:393–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alarcon GS Bastian HM Beasley TM, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multi-ethnic cohort (LUMINA) XXXII: [corrected] contributions of admixture and socioeconomic status to renal involvement. Lupus. 2006;15:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alarcon GS Calvo-Alen J McGwin G Jr., et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort: LUMINA XXXV. Predictive factors of high disease activity over time. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1168–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcon GS Friedman AW Straaton KV, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups: III. A comparison of characteristics early in the natural history of the LUMINA cohort. LUpus in MInority populations: NAture vs. nurture. Lupus. 1999;8:197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uribe AG McGwin G Jr Reveille JD, et al. What have we learned from a 10-year experience with the LUMINA (lupus in minorities; nature vs. nurture) cohort? Where are we heading? Autoimmun Rev. 2004;3:321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers SA, Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Treatment adherence and clinical outcome in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:895–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drenkard C Dunlop-Thomas C Easley K, et al. Benefits of a self-management program in low-income African-American women with systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a pilot test. Lupus. 2012;21:1586–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. Promoting health literacy research to reduce health disparities. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goeppinger J Armstrong B Schwartz T, et al. Self-management education for persons with arthritis: managing comorbidity and eliminating health disparities. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams KGA, Corrigan JM, editors. Committee on the Crossing the Quality Chasm: Next Steps Toward a New Health Care System 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navarra SV, Zamora LD, Collante MTM. Lupus education for physicians and patients in a resource-limited setting. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ra JH Leung J Baker EA, et al. The patient perspective on using digital resources to address unmet needs in systemic lupus erythematosus [published online August 2, 2020]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020. doi: 10.1002/acr.24399[publishedOnlineFirst:2020/08/03]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callejas-Rubio JL Ríos-Fernández R Barnosi-Marín AC, et al. Health-related internet use by lupus patients in southern Spain. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.InternetWorldStats . Latin American internet usage statistics. 2019. https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats10.htm. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- 21.Fernández Vítores D. El Español: Una Lengua Viva. Informe 2019. Instituto Cervantes. 2019. https://cvc.cervantes.es/lengua/espanol_lengua_viva/pdf/espanol_lengua_viva_2019.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2020.

- 22.Reto L Gulamhussen M Machado F, et al. Potencial Económico da Língua Portuguesa. Texto; Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupus Foundation of America . Centro Nacional de Recursos para el Lupus. https://www.lupus.org/es/resources. Accessed December 17, 2020.

- 24.Ginsberg S. Rheumatologist vs Dr. Google: battling misinformation rheumatology. 2016. Rheumatology Network. https://www.rheumatologynetwork.com/view/rheumatologist-vs-dr-google-battling-misinformation. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 25.McNab C. What social media offers to health professionals and citizens. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamel Boulos MN, Wheeler S. The emerging Web 2.0 Social Software: an enabling suite of sociable technologies in health and health care education. Health Info Libr J. 2007;24:2–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stellefson M Paige SR Chaney BH, et al. Evolving role of social Media in Health Promotion: updated responsibilities for health education specialists [published online February 16, 2020]. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1153. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adams SA. Revisiting the online health information reliability debate in the wake of “Web 2.0”: an inter-disciplinary literature and Website review. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79:391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper P. How the Facebook algorithm works in 2020 and how to make it work for you. Hootsuite. 2020. https://blog.hootsuite.com/facebook-algorithm/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 30.Rabo O. We analyzed 2,810 pages to calculate average Facebook engagement rate. Iconosquare. 2019. https://blog.iconosquare.com/average-facebook-engagement-rate/. Accessed November 11, 2020.

- 31.Massone F Martínez ME Pascual-Ramos V, et al. Educational Website incorporating rheumatoid arthritis patient needs for Latin American and Caribbean countries. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:2789–2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huerta TR, Walker DM, Ford EW. Cancer center Website rankings in the USA: expanding benchmarks and standards for effective public outreach and education. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32:364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moorhead SA Hazlett DE Harrison L, et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDonnell TCR Wincup C Rahman A, et al. Going viral in rheumatology: using social media to show that mechanistic research is relevant to patients with lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2018;2:rky003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crosley E Fuentes Y Pons-Estel BA, et al. Differences in lupus self-management education priorities among Spanish-speaking patients via the “Hablemos de Lupus” Facebook page. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26(Suppl 2):S75. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosley E Elera-Fitzcarrald C Ferreyra-Garrot L, et al. Understanding the relationship between illness perceptions and self-efficacy among Latin Americans with SLE through the Hablemos De Lupus Facebook page. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(Suppl 10): abstract 1980. [Google Scholar]