ABSTRACT

Objective:

The objective of this scoping review was to map and describe the available evidence reporting out-of-pocket expenses related to aging in place for older people with frailty and their caregivers.

Introduction:

As the global population ages, there has been increasing attention on supporting older people to live at home in the community as they experience health and functional changes. Older people with frailty often require a variety of supports and services to live in the community, yet the out-of-pockets costs associated with these resources are often not accounted for in health and social care literature.

Inclusion criteria:

Sources that reported on the financial expenses incurred by older people (60 years or older) with frailty living in the community, or on the expenses incurred by their family and friend caregivers, were eligible for inclusion in the review.

Methods:

We searched for published and unpublished (ie, policy papers, theses, and dissertations) studies written in English or French between 2001 and 2019. The following databases were searched: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Embase, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, and Public Affairs Index. We also searched for gray literature in a selection of websites and digital repositories. JBI scoping review methodology was used, and we consulted with a patient and family advisory group to support the relevance of the review.

Results:

A total of 42 sources were included in the review, including two policy papers and 40 research papers. The majority of the papers were from the United States (n = 18), with others from Canada (n = 6), the United Kingdom (n = 3), Japan (n = 2), and one each from Australia, Brazil, China, Denmark, Israel, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Turkey. The included research studies used various research designs, including cross-sectional (n = 18), qualitative (n = 15), randomized controlled trials (n = 2), longitudinal (n = 2), cost effectiveness (n = 1), quasi-experimental (n = 1), and mixed methods (n = 1). The included sources used the term “frailty” inconsistently and used various methods to demonstrate frailty. Categories of out-of-pocket expenses found in the literature included home care, medication, cleaning and laundry, food, transportation, medical equipment, respite, assistive devices, home modifications, and insurance. Five sources reported on out-of-pocket expenses associated with people who were frail and had dementia, and seven reported on the out-of-pocket expenses for caregivers of people with frailty. While seven articles reported on specific programs, there was very little consistency in how out-of-pocket expenses were used as outcome measures. Several studies used measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses, but there was no standard approach to reporting aggregate out-of-pocket expenses.

Conclusions:

Contextual factors are important to the experiences of out-of-pocket spending for older people with frailty. There is a need to develop a standardized approach to measuring out-of-pocket expenses in order to support further synthesis of the literature. We suggest a measure of out-of-pocket spending as a percentage of family income. The review supports education for health care providers to assess the out-of-pocket spending of community-dwelling older people with frailty and their caregivers. Health care providers should also be aware of the local policies and resources that are available to help older people with frailty address their out-of-pocket spending.

Keywords: aging in place, frailty, older adult, out-of-pocket expenses, scoping review

Introduction

Improving the care of older people experiencing health and functional changes has become a priority for health care systems globally.1 The proportion of the population over 65 years of age is growing; it is estimated that by 2050 there will be 1.5 billion older people in the world, an increase from 703 million in 2019.2 Generally, people are living longer and more often have chronic health conditions than in the past.1,3 With these demographic changes, there has been concern among policy-makers that health care costs will grow.4 Supporting older people to live in the community as they experience health and functional changes has been promoted as a means to avoid preventable hospitalizations incurred due to insufficient support, and to limit health care costs associated with long-term care (LTC).5-8 The increasing interest in supporting older people to live in their homes in the community – often referred to as aging in place – as they experience health and functional changes also aligns with literature reporting on the preferences of older people, which demonstrates that they generally prefer to remain at home for as long as possible.9-11

There has been a growing imperative in health care literature to understanding the unique situation of older people who have multiple chronic conditions that contribute to functional impairment (ie, those considered frail). Frailty is associated with reduced function, a loss of independence, and need for support, as well as continual decline over time.12-14 To support this population to remain living in the community, a range of supports are needed, many of which are associated with out-of-pocket expenses – that is, expenses paid by older people and their caregivers without reimbursement.15 In addition to the health challenges associated with frailty, individuals and their families may experience unanticipated financial burden.16 Financial considerations contribute to decisions to move to LTC for older people.17 The costs to enable an older person to live at home may eventually be comparable to the costs of LTC, or financial concerns combined with other factors, such as safety or caregiver strain, may make living at home impossible.17 While it is essential to consider the sustainability of the health care system as the population ages, it is also important to consider how efforts to support older people in the community contribute to financial burden for them and their family caregivers.18

Frailty

Frailty is increasingly recognized as a physiological condition that impacts the health and quality of life of many older adults.8,13,14 While there is still considerable disagreement in the literature about the operational definition of frailty, it is generally used to refer to people experiencing a loss of capacity to recover after illness, in addition to a higher risk of poor outcomes such as falls, functional decline, mortality, and hospitalization.8,14,19-21 There is a growing body of literature reporting on how people living with frailty use health care services and community supports, which suggests that those who are frail have higher health and social care costs than those who are not frail.15,22,23 Frailty prevalence estimates vary significantly; a systematic review conducted in 2012 found that rates of frailty prevalence ranged from 4% to almost 60% of older people aged 65 years and older.24 Rates varied mainly due to two notable factors: i) the particular characteristics of the population, and ii) the definition of frailty used in the studies. Baseline data from a Canadian longitudinal study found frailty prevalence to be 10.6% in participants over 75 years, with more cases among women and increasing occurrence with age.25 A recent meta-analysis reported frailty prevalence rates in community-dwelling people 65 years or older in China as 5.9% to 17.4%.26 We included studies reporting on people over the age of 60 years experiencing frailty because it is the most inclusive age cut-off used to define older adults in the literature.

Out-of-pocket expenses

For this review, out-of-pocket expenses are defined as financial expenses incurred by older adults or family and friend caregivers to enable frail older people to live well in their homes in the community. Out-of-pocket expenses associated with living well at home include a broad array of services and supports that are related to medical conditions or functional impairment, but are not paid or reimbursed by public health care systems or covered by health insurance. For example, expenses may include assistive devices or over-the-counter medications to address symptoms of health conditions, services such as property maintenance, or essential home modifications to ensure safety when individuals experience functional decline. Literature reporting on the impact of out-of-pocket expenses for people experiencing specific health conditions (eg, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes) also suggests that out-of-pocket spending related to their health conditions impacts their ability to afford basic living expenses such as food and shelter.27-29 For older people with frailty, who have multiple health conditions that affect their functional abilities, medical and non-medical out-of-pocket expenses are a particularly important issue. Older people are often on fixed incomes, and those experiencing frailty may have few opportunities to engage in paid work.1 Significant out-of-pocket expenses combined with limited income can contribute to financial insecurity in older people, which in turn can contribute to medication non-adherence, disrupted access to health care, and inability to leave unsafe living environments.1,27,30

While there has been a concerted effort by many health and social care leaders to support older people with frailty to live in the community to reduce unnecessary costs associated with LTC,1,18 the individual-level expenses required to enable living well at home are often not explicitly addressed. In 2010, Johnson and Mommaerts predicted that out-of-pocket spending by older people in the United States would increase over the subsequent 30 years, contributing to significant financial strain.31

A preliminary search of PROSPERO, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports was conducted and no planned or in-progress systematic or scoping reviews examining the out-of-pocket expenses to support frail older people in the community were identified. While there have been reviews that address the costs associated with supporting older people with frailty in the community, these reviews have approached the subject from the perspective of the health care system and society,32 and have not considered out-of-pocket expenses borne by individuals and caregivers. Looman and colleagues conducted a review of literature reporting on preventive and integrated care for older people with frailty in the community and reported cost effectiveness from societal and health care perspectives.33 Apóstolo and colleagues published a systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to limit the progression of frailty, and included an analysis of health care costs.34 Lastly, a review by Young and colleagues compared the health care costs of functionally dependent older adults in the community with health care costs of providing care to this population in LTC.35 However, none of these studies examined the out-of-pocket costs assumed by individuals with frailty and their caregivers. A fourth review explored the economic costs associated with caregiving, and included findings related to out-of-pocket expenses.16 This scoping review did not discuss the out-of-pocket expenses of caregivers or include information on the out-of-pocket expenses incurred by older people with frailty themselves.16

The objective of this scoping review was to map and describe the available evidence reporting out-of-pocket expenses related to aging in place for older people with frailty and their caregivers. An understanding of this literature is important as further synthesis of the available literature can shape policy and practice to better support older people with frailty to continue living in their homes.

Review question

What is the evidence on out-of-pocket expenses associated with aging in place for older people with frailty, and their family and friend caregivers?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This scoping review considered all research studies and policy papers that included older people experiencing frailty living in community settings, as well as sources that included family and friend caregivers of older people with frailty. Studies that included participants aged 60 years and older, with multiple chronic conditions and functional impairment were included. While our protocol stated we would include studies that employed a measure of frailty, we ultimately decided to broaden our inclusion criteria to studies that described their population as frail or included an older population with multiple chronic conditions and functional impairment,36 because the term “frailty” is not consistently defined or applied in the literature.8

Concept

This review considered studies that reported on the financial, out-of-pocket expenses incurred by older people living with frailty in the community or by their family and friend caregivers. Out-of-pocket expenses are those that are paid by individuals, and do not include expenses paid by public funding or by third parties such as insurance companies. We only included actual expenses, and did not include studies that estimated financial implications, such as lost income due to unpaid caregiving responsibilities.

Context

This review considered studies that focused on older people living in the community and excluded studies reporting on older people living in LTC or assisted living facilities. Studies conducted in all countries were eligible for inclusion.

Types of sources

For this scoping review, we included published and unpublished original research and policy papers that explored issues related to out-of-pocket spending by frail older adults or their caregivers.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews,37 and included input from people with lived experience supporting older people with frailty through two patient and caregiver engagement groups.38,39 The involvement of stakeholders in scoping reviews aims to provide grounding for the study and foster discussion about potential implications. The patient and caregiver advisory groups in this project contributed to developing the research questions and inclusion criteria, identified keyword synonyms to include in the search, supported the identification of gaps in the body of literature, and generated new ideas about implications of the review.

Search strategy

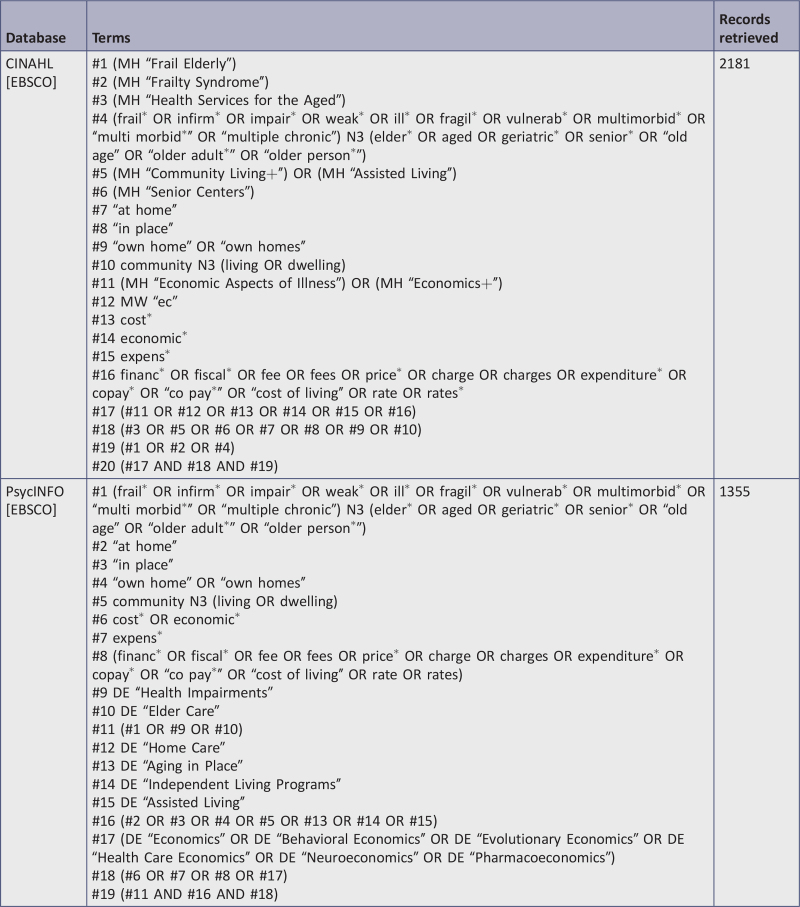

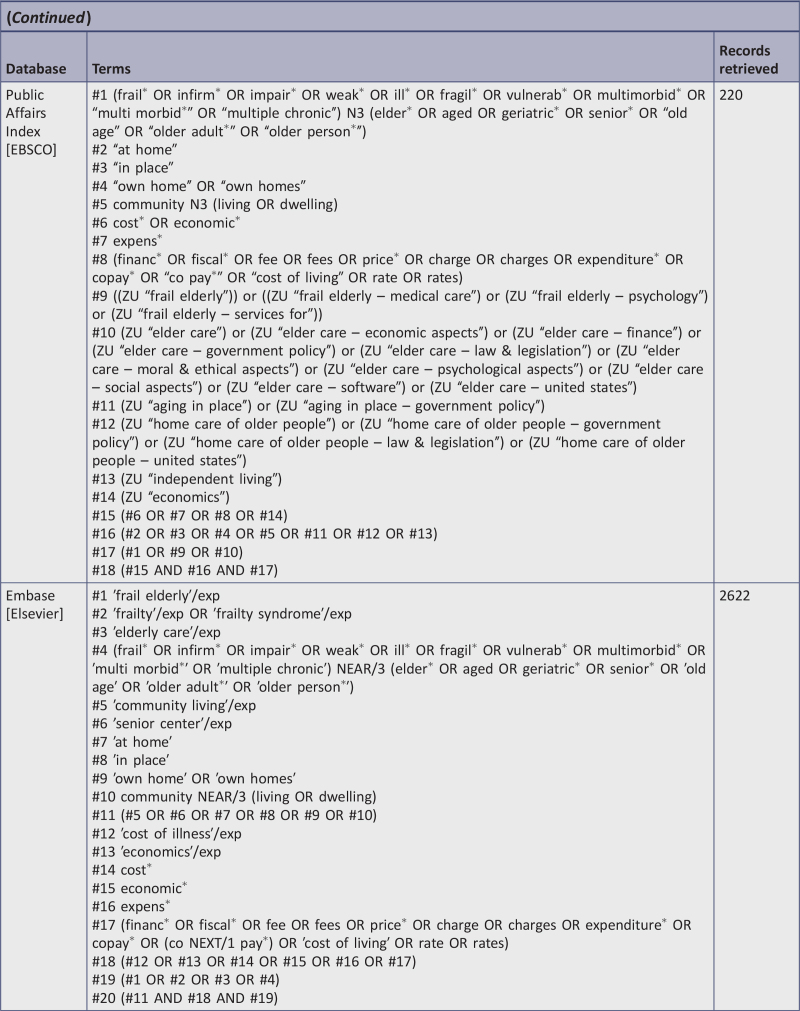

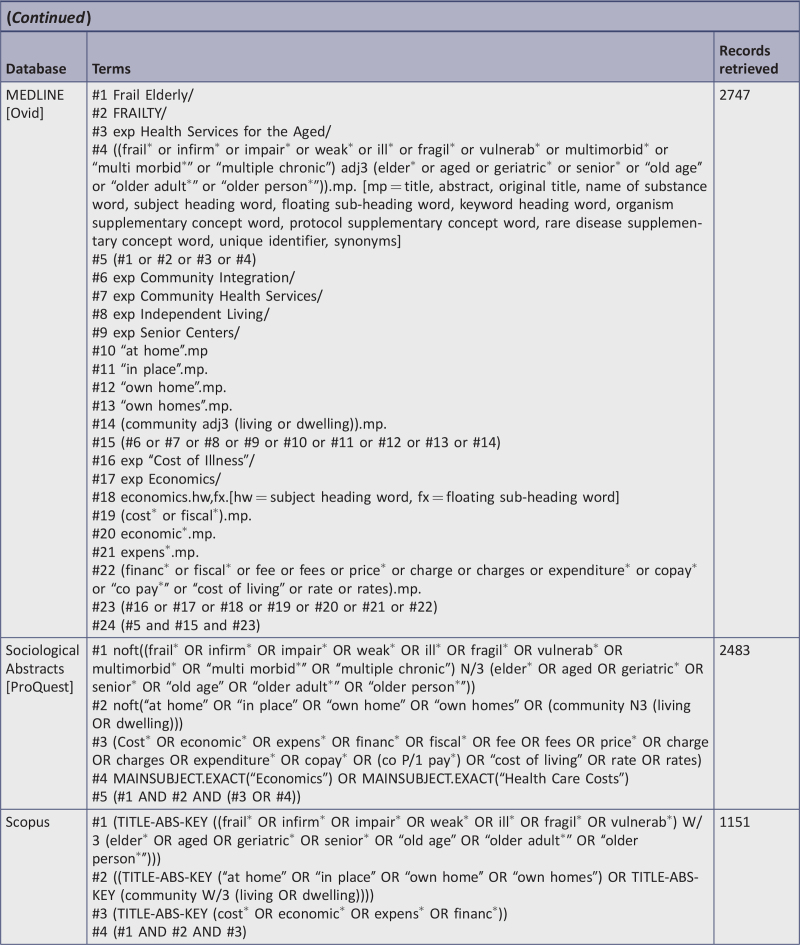

The search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished literature (ie, policy papers, theses, and dissertations). A three-step search strategy was used to identify published literature. An initial limited search of MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), and Embase (Elsevier) was undertaken followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract, and of the index terms used to describe the article. A second systematic search using all identified keywords and index terms was then undertaken across all included published literature databases on September 27, 2019. Third, reference lists of included literature were hand searched for additional relevant studies. The search strategy is included as Appendix I.

The databases searched for published literature include: CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE (Ovid), Scopus, Embase (Elsevier), APA PsycINFO (EBSCO), Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), and Public Affairs Index (EBSCO). MEDLINE (Ovid) replaced PubMed (listed in the protocol) because the final search strategy included two lines that incorporate adjacency searching, which PubMed does not support.

Due to limited resources, only literature published in English or French was considered for inclusion in this review. We restricted our review to studies conducted after 2001 when a seminal definition of frailty was published21; this is a deviation from the protocol.

The search for gray literature was completed on September 27, 2019, and targeted the following websites and digital repositories: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Alzheimer's Association: Alzheimer's Disease and Dementia (US), Alzheimer Society of Canada, Alzheimer's Society (UK), American Nurses Association, Canadian Nurses Association, centers for health evidence, conference proceedings, digital dissertations, DiVA (dissertations and other publications in full text from Nordic Universities), EPPI-Centre, Google Scholar, GrayLIT Network, Gray Literature Bulletin (North West Health Library and Information Services, Liverpool, UK), Gray Literature Report (via New York Academy of Medicine website), Gray Source: a Selection of Web-based Resources in Gray Literature, Index to Theses, Institute for Health and Social Care Research, National Information Center on Health Services Research and Health Care Technology, National Library of Medicine, Netting the Evidence, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations, New York Academy of Medicine Gray Literature Report NLM Gateway, Policy Hub, Primary Care Clinical Practice Guidelines, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Databases, PsycExtra, Public Health Agency of Canada, SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe), and TRIP (Turning Research into Practice).

Study selection

After the search was completed, all citations were uploaded to Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) and duplicates removed. Two reviewers (from among EM, RG, RMM, JP, MM, LEW, EO, and KJ) independently screened the title and abstract of each citation, and selected studies that met the inclusion criteria. The full-text articles were retrieved and uploaded into Covidence. These studies were then assessed independently by two reviewers (from among those listed above) to determine if they met the study inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the two independent reviewers at each review stage were resolved by consensus or with a third reviewer. Quality appraisal of selected studies was not conducted, as the standard procedure and aim of scoping reviews is to provide an overview of the literature.37

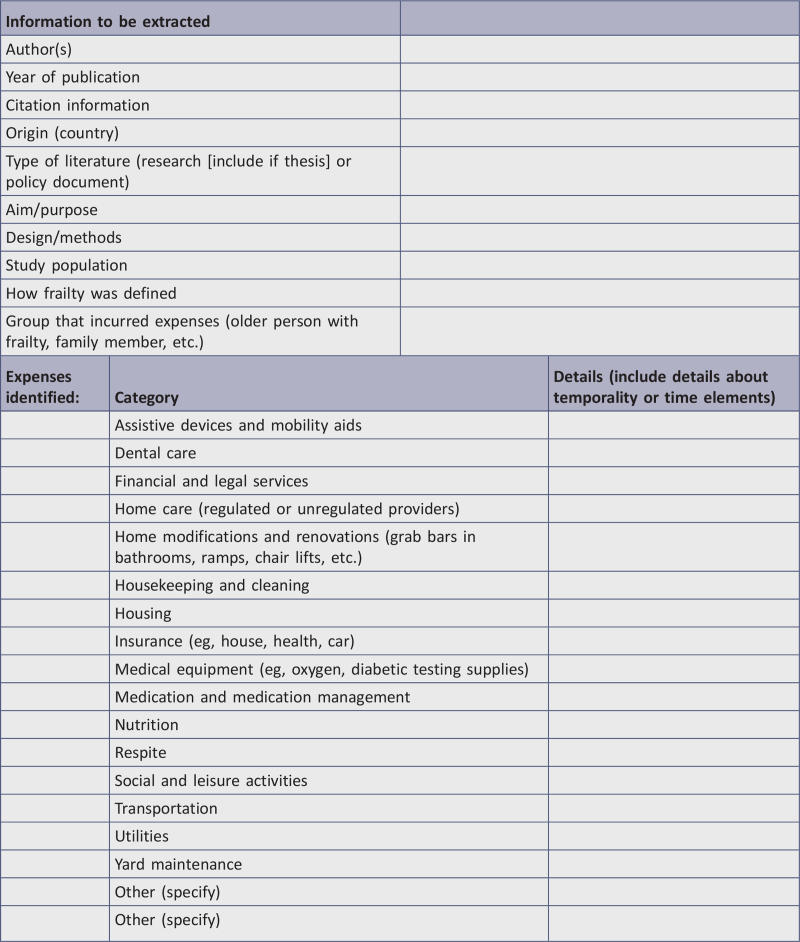

Data extraction

Following the JBI scoping review methodology,37 data were extracted from included papers by two independent reviewers (from among EM, RG, RMM, JP, MM, LEW, EO, and KJ) using a data extraction tool (Appendix II) developed by the reviewers and refined following a piloting with a small number of studies, and subsequently applied to all included studies. Categories of out-of-pocket expenses were refined throughout the data extraction process to ensure all extracted data were accounted for. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer.

Data analysis and presentation

Results are reported graphically with tables when possible. The narrative that accompanies the tables further describes the body of literature. The findings of the review are reported in four sections that were determined once the relevant sources were identified to reflect the objectives of the review. The sections are: i) categories of out-of-pocket expenses, ii) measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses, iii) out-of-pocket expenses for select populations, iv) out-of-pocket expenses as outcomes in the evaluation of policies, programs, and services.

Results

Study inclusion

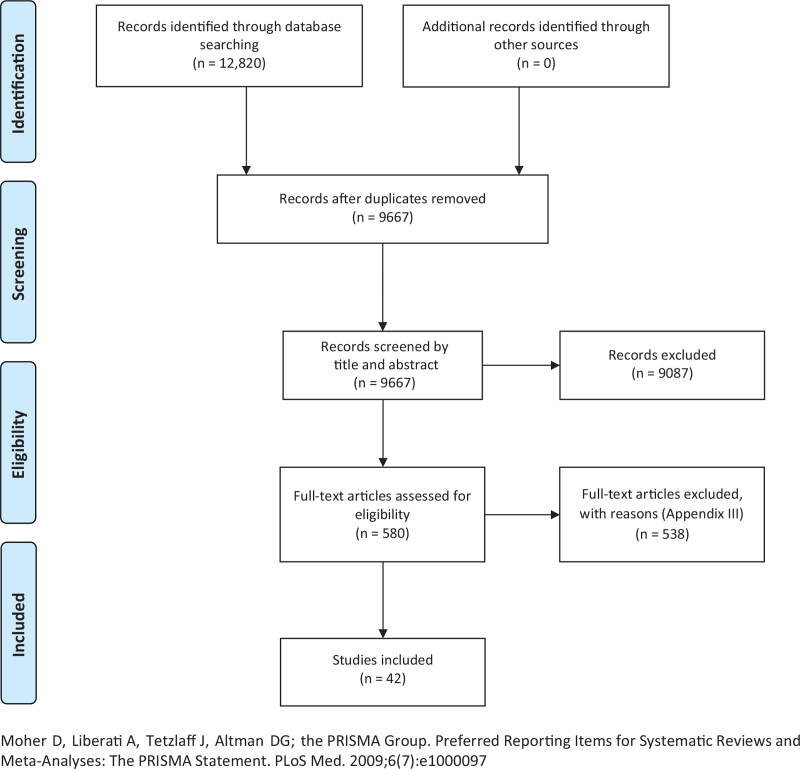

A total of 12,820 titles were identified and uploaded to Covidence for screening. Of these, 3153 were duplicates. At the title and abstract phase, 9667 studies were screened, with 9087 studies found ineligible. There were 580 full-text studies assessed for eligibility through full-text screening, and 538 were excluded (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results and source selection and inclusion process

Reasons for exclusion were as follows: not a research study or policy document (173), not reporting on out-of-pocket expenses (139), not including an older population that was frail (193), written in a language other than English or French (17), and not set in the community (10). Six citations were not available as full text through our libraries or after contacting the authors. Detailed information on the reason for exclusion of each article can be found in Appendix III. The resulting 42 articles were included in the review. An examination of the reference lists of the included papers did not result in any further literature for inclusion.

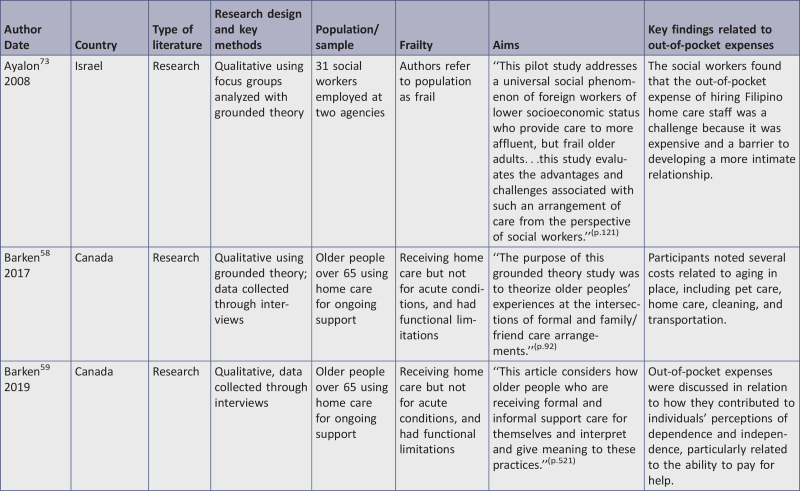

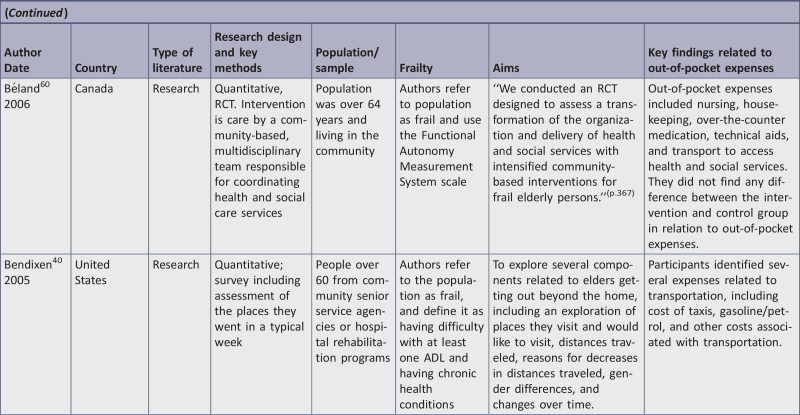

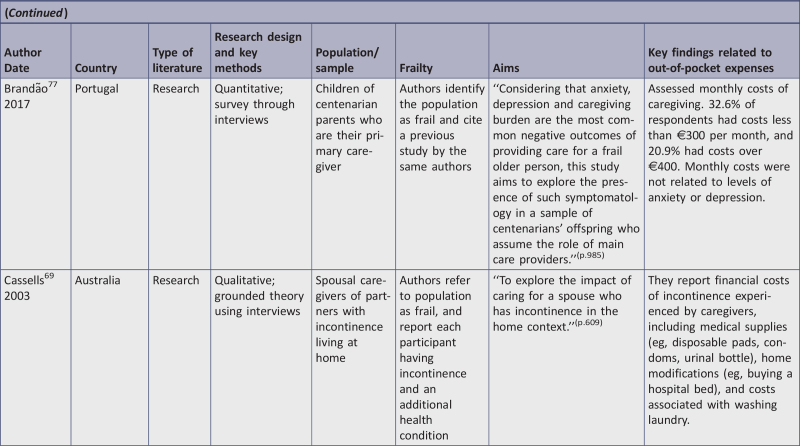

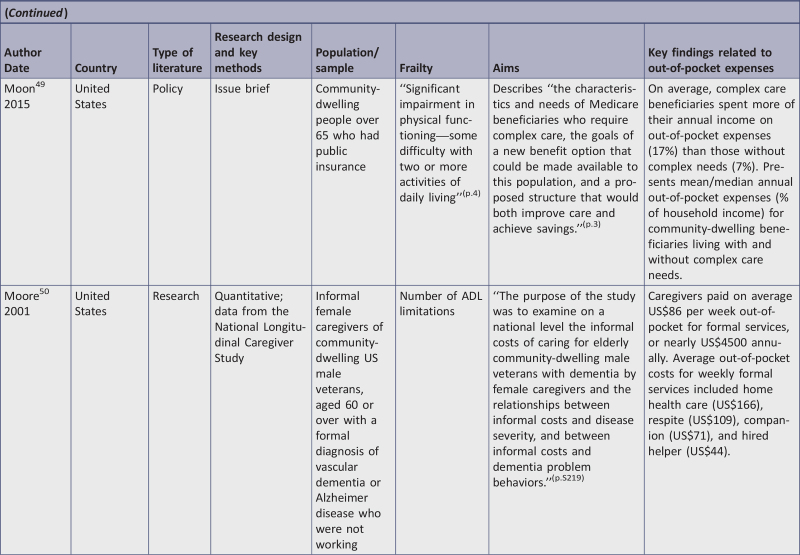

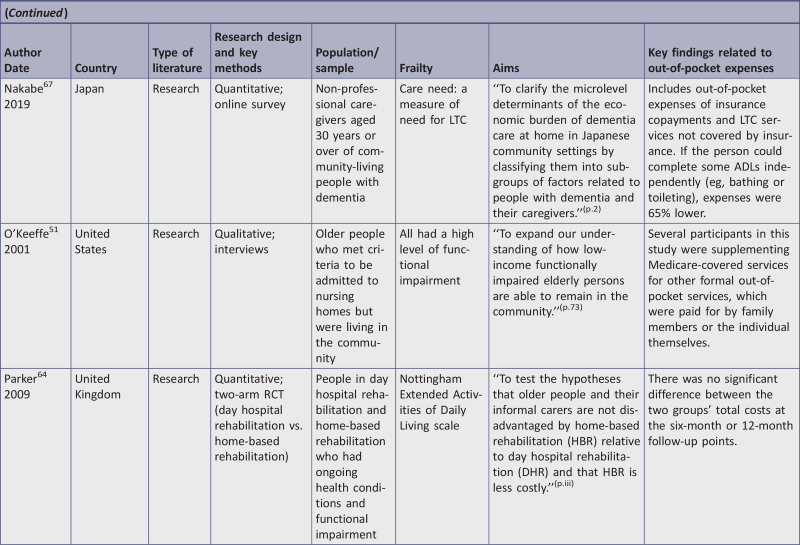

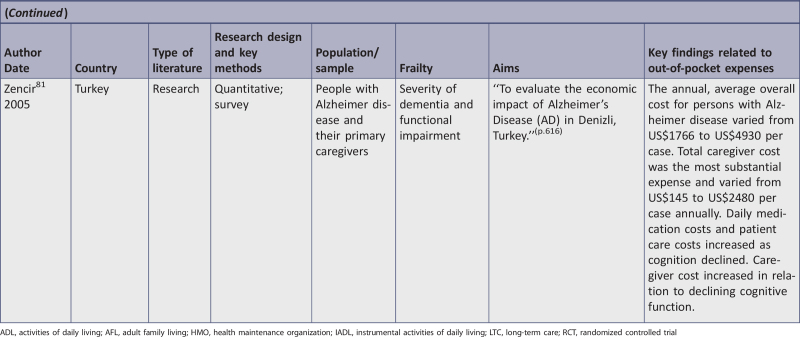

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of the included sources are presented in Appendix IV. The majority of the papers were from the United States (n = 18).40-57 Others were from Canada (n = 6),58-63 the United Kingdom (n = 3),64-66 Japan (n = 2),67,68 and one apiece from Australia,69 Brazil,70 China,71 Denmark,72 Israel,73 Italy,74 The Netherlands,75 Poland,76 Portugal,77 Singapore,78 South Korea,79 Taiwan,80 and Turkey.81 Studies were published across the date range included (2001 to 2019); there did not appear to be any trends in studying this issue over time. Most sources included costs incurred by individuals and their caregivers, but seven reported costs only for caregivers.50,61,67-69,77,78 Forty articles were journal articles reporting research findings and two were policy papers.49,72 The included research studies used various research designs, including cross-sectional (n = 18),40,45,46,48,50,52,54,56,57,66-68,70,71,75,77,79,81 qualitative (n = 15),42,47,51,55,58,59,61-63,69,73,74,76,78,80 randomized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 2),60,64 longitudinal (n = 2),44,53 cost effectiveness (n = 1),65 quasi-experimental (n = 1),43 and mixed methods (n = 1).41

Review findings

The results of this scoping review are discussed under the follow sections: i) categories of out-of-pocket expenses, ii) measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses, iii) out-of-pocket expenses for select populations, and iv) out-of-pocket expenses as outcomes in the evaluation of policies, programs, and services.

Categories of out-of-pocket expenses

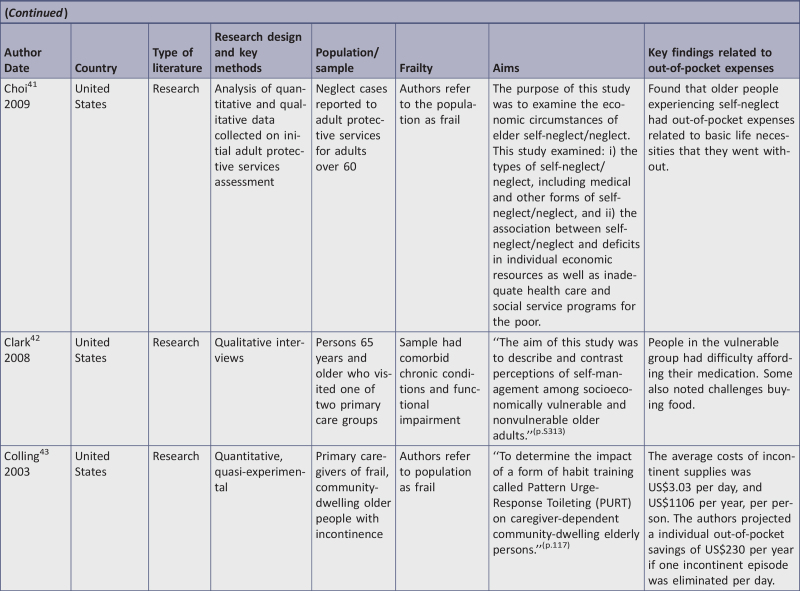

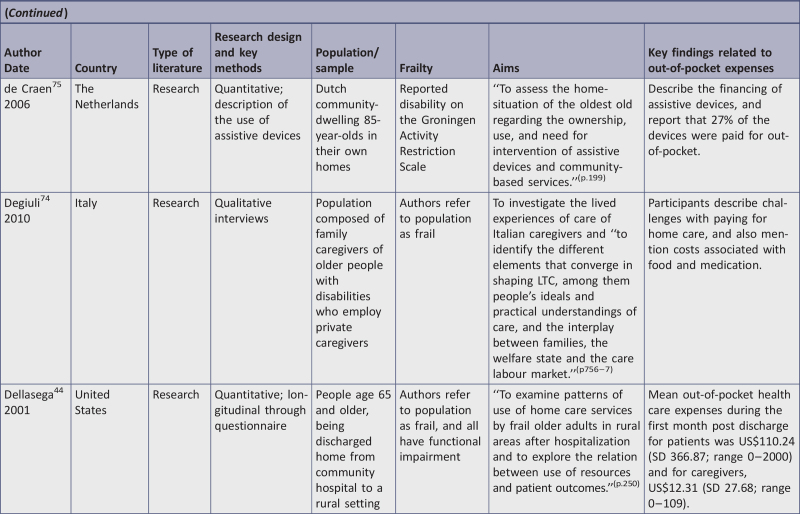

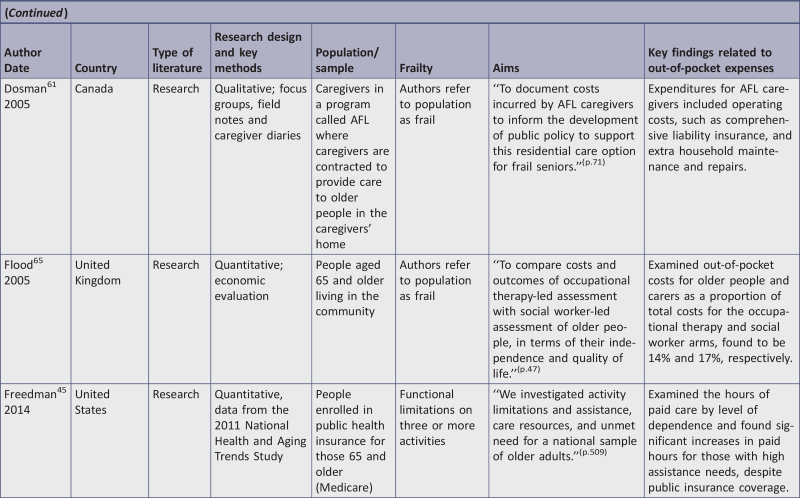

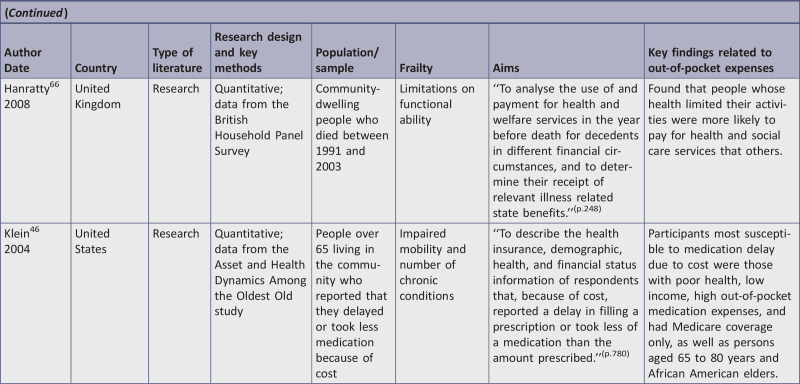

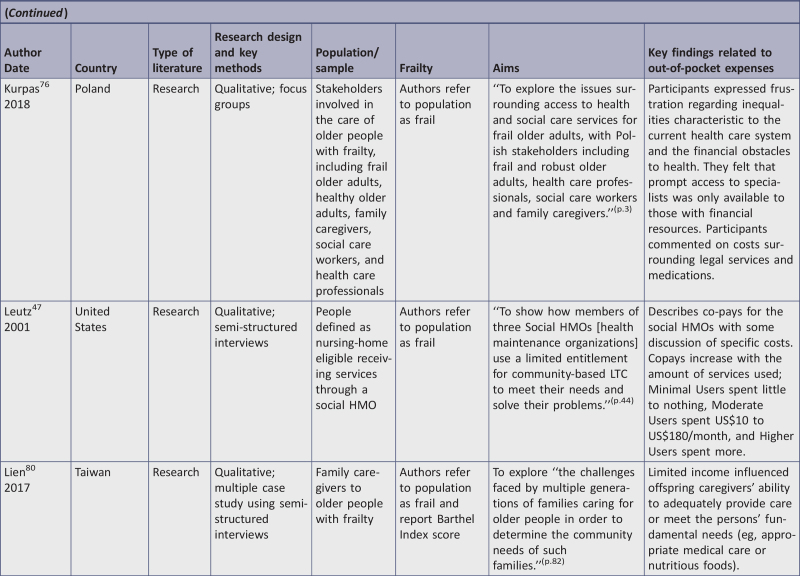

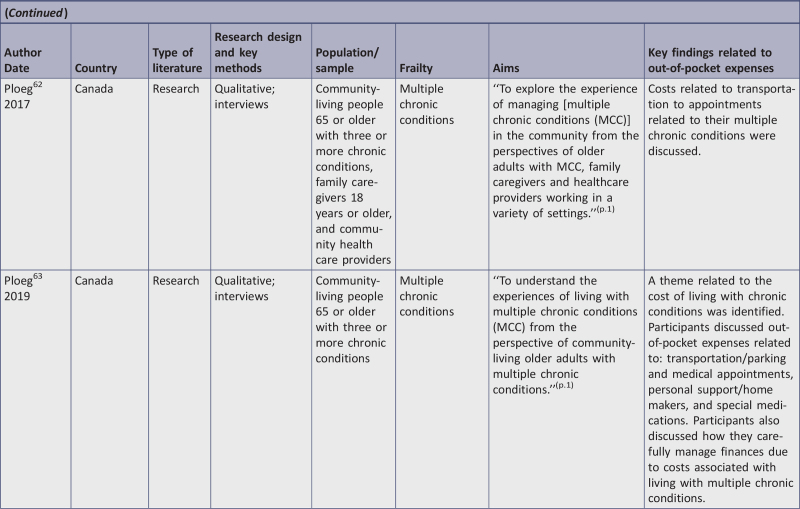

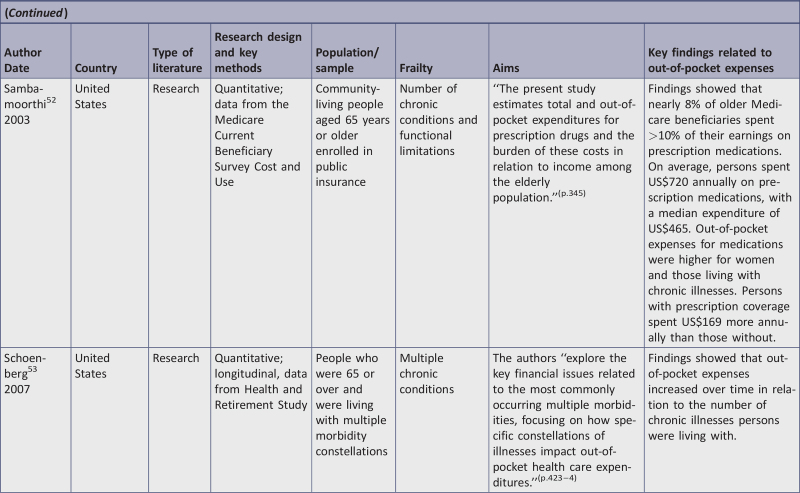

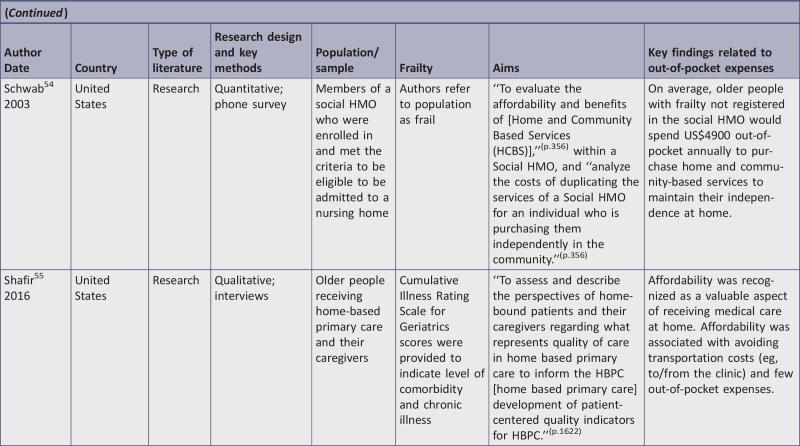

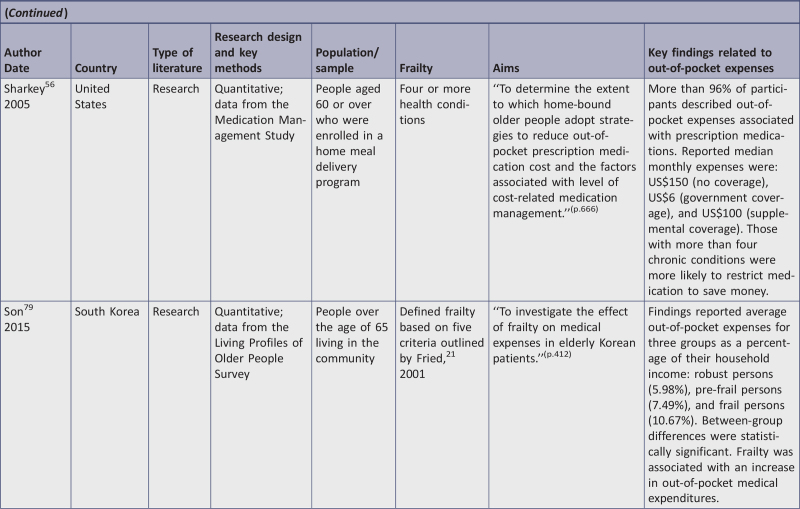

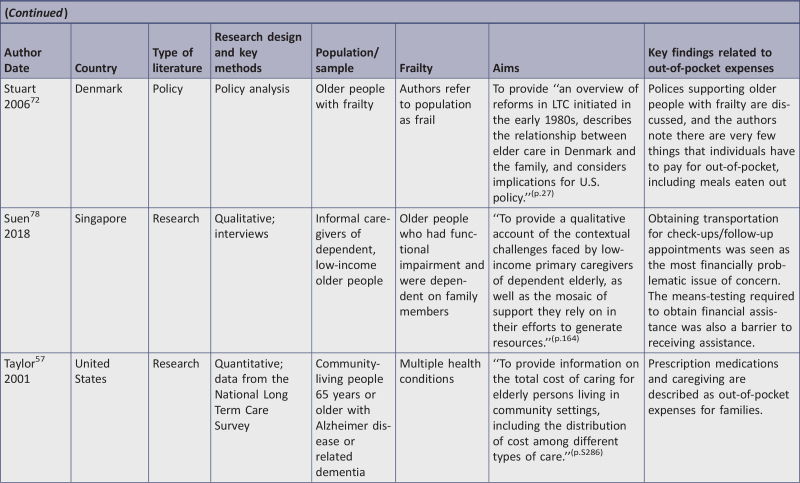

We categorized the expenses that each source identified, and summarized the findings in Table 1. The categories were developed by consensus of the review team. The most common category of out-of-pocket expense discussed was home care provided by regulated or unregulated providers (n = 16), followed by medication and medication management (n = 12), cleaning and laundry (n = 10), food and meal preparation (n = 9), transportation (n = 8), medical equipment and assistive devices (n = 8), respite care (n = 6), home modifications and renovations (n = 5), and insurance (n = 5). Other out-of-pocket expenses that were identified by one or two sources included dental care,53 emergency response systems,47 yard maintenance,47 doctors’ visits,53 financial transfers to family members,71 pet care,58 vacations,74 hair care,50 health care specialists,70 financial and legal services,76 and care planning services.68

Table 1.

Categories of out-of-pocket expenses related to aging in place for frail older people

| Author | Home care | Medication | Cleaning and laundry | Food | Transportation | Medical equipment and assistive devices | Respite | Home modifications | Insurance | Other |

| Ayalon et al. 200873 | X | |||||||||

| Barken 201758 | X | X | X | Pet care | ||||||

| Barken 201959 | X | |||||||||

| Beland et al. 200660 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Bendixen et al. 200540 | X | |||||||||

| Cassells and Watt 200369 | X | X | ||||||||

| Choi et al. 200941 | X | X | X | X | Utilities | |||||

| Clark et al. 200842 | X | X | ||||||||

| Colling et al. 200343 | X | |||||||||

| de Craen et al. 200675 | X | X | ||||||||

| Degiuli 201074 | X | Vacations | ||||||||

| Dosman and Keating 200561 | X | X | X | |||||||

| Flood et al. 200565 | ||||||||||

| Freedman and Spillman 201445 | X | |||||||||

| Hanratty et al. 200866 | X | X | ||||||||

| Klein et al. 200446 | X | |||||||||

| Kurpas et al. 201876 | X | Financial and legal services | ||||||||

| Leutz et al. 200147 | X | X | X | Yard maintenance; emergency response systems | ||||||

| Lien and Huang 201780 | X | X | ||||||||

| Liu et al. 201771 | Financial transfers to children | |||||||||

| Moore et al. 200150 | X | X | X | Hair care | ||||||

| Nakabe et al. 201967 | X | |||||||||

| O’Keefe et al. 200151 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Ploeg et al. 201762 | X | |||||||||

| Ploeg et al. 201963 | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Sambamoorthi et al. 200352 | X | |||||||||

| Schoenberg et al. 200753 | X | X | X | Doctor or dental visits | ||||||

| Schwab et al. 200354 | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Shafir et al. 201655 | X | Physician access | ||||||||

| Sharkey et al. 200556 | X | |||||||||

| Stuart and Hansen 200672 | X | X | ||||||||

| Taylor et al. 200157 | X | |||||||||

| Veras et al. 200870 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | Health care specialists | |

| Washio et al. 201268 | X | X | X | X | X | X | Care plan services | |||

| Zencir et al. 200581 | X | |||||||||

| Total | 16 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Home care

Several studies had an explicit focus on the costs associated with home care for older people with frailty, such as the expenses associated with hiring regulated and unregulated care providers to perform various activities of daily living (ADLs). Two studies discussed the costs associated with hiring unregulated migrant home care workers to provide care for older people.73,74 Both studies indicated that unregulated migrant home care workers were often hired because they cost less than other home care services. However, the expense of their employment impacted the experience of out-of-pocket spending for caregivers forced to balance the costs of care with the desired quality of care. In Israel, Ayalon and colleagues reported from the perspective of social workers who suggested that families found out-of-pocket costs to hire private care providers contributed to the challenges of caring for older people.73 In Italy, Degiuli reported findings from interviews with family caregivers of older people and discussed expenses associated with hiring migrant nurses and unregulated care providers. Some study participants felt they could not afford “good care,”74(p.764) suggesting that good care would require spending more to have care providers come more often.

Freedman and Spillman examined the out-of-pocket costs associated with home care for people receiving public insurance benefits (Medicare and Medicaid) in the United States.45 They examined the average number of home care hours used by people requiring various levels of assistance and found that those with higher assistance needs not only received more home care but also paid higher amounts in out-of-pocket expenses, such as copayments and added services, than those with lower assistance needs.

Two papers by Barken conducted in Canada reported on a qualitative study of 34 older people receiving home care.58,59 One paper focused on how older people receiving home care balanced the expectations of family to be involved in their care with the role of care providers, and found that paying out-of-pocket for services lessened negative feelings associated with being a burden on family caregivers.58 The other paper explored how older people receiving home care experience independence and dependence, and found that paying out-of-pocket for services contributed to feelings of independence.59

Medication

Costs associated with medication and medication management were also a focus of many of the included sources. Sambamoorthi et al. examined the financial burden of prescription drugs for older people who were enrolled in a publicly funded insurance program in the United States (ie, Medicare and Medicaid), including an analysis of both total and out-of-pocket expenses.52 They gathered data on out-of-pocket expenses, including copayments, deductibles, and other charges, and found that higher out-of-pocket costs were related to higher levels of functional impairment, lower levels of self-reported health, more comorbid medical conditions, and female gender.

The out-of-pocket costs of medications and medication management were a particular concern when individuals had limited financial resources.41,42,46,56,76 Drawing from a national database in the United States, Klein and colleagues examined the characteristics of older people who delayed taking a prescribed medication due to cost.46 They found that people who had more medical illnesses, ADL limitations, or higher levels of mobility impairment were more likely to report delaying medication use due to cost. Similarly, Choi and colleagues examined the experiences of older people with frailty who were also experiencing neglect or self-neglect, and found that they sometimes did not purchase important medication and therefore did not follow the prescribed treatment, and noted costs as one of the reasons.41

Sharkey and colleagues also explored issues around individuals restricting medication use due to costs.56 They collected data on strategies undertaken to decrease medication costs from a sample of homebound older people receiving home-delivered meals in one US state (North Carolina), and found that 96% of respondents had out-of-pocket medication expenses, including copayments, co-insurance, and costs not covered by insurance. The authors reported monthly out-of-pocket spending by level of insurance; those with no drug coverage had a median monthly out-of-pocket medication cost of US$150, those with government coverage had costs of US$6, and those with supplemental drug coverage had costs of US$100. They also found that 20% of the total sample restricted medication use due to cost.

Clark and colleagues examined people who were socioeconomically disadvantaged, and found many had high copayments for medication that contributed to difficultly making payments.42 However, few participants in the study reported missing medications due to costs, unlike other research reported here. Ploeg and colleagues also found that the costs of medication affected the ability of older adults with multimorbidity to pay for other essentials, and had to be weighed against spending on other necessities.63 A study by Kurpas and colleagues exploring the experiences of older people with frailty in Poland accessing health care found that the high costs of medication in relation to available resources meant that many older people did not follow their prescribed treatment plan.76

Cleaning and laundry

Housekeeping, laundry, and cleaning were expenses frequently not covered by other programs and services.47,50,51,54,58,60,61,63,69,72 One study conducted in Canada reported that a woman with the financial means to easily pay for such services preferred to pay for them out-of-pocket rather than add to the burden of her family members.58 Other sources noted out-of-pocket costs for laundry services associated with incontinence,69 reported actual costs paid for cleaning,54 and included housekeeping costs in measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses.50,60

Food

Several identified sources noted meal delivery services requiring out-of-pocket costs.51,54,66,68,75 Two studies reported that other costs impacted the ability of people with frailty to pay for food.41,42 A policy paper from Denmark suggested that the costs associated with eating out at restaurants were one of the few out-of-pocket costs borne by people with frailty in that country.72 Only one study included the cost of food in a measure of combined out-of-pocket expenses.70

Transportation

Transportation expenses included the cost of taxis, public transportation, gasoline/petrol and car insurance, ambulance costs, and paying friends or family members to provide transportation. Bendixen and colleagues examined the experiences of older people with frailty getting out of their homes and included an exploration of related out-of-pocket costs.40 The authors drew on data from initial interviews with older people participating in a national longitudinal study in the United States. As part of their analysis, the authors reported the frequency that participants wanted to go somewhere but could not due to financial considerations such as the cost of taxis, gasoline/petrol, or other transportation costs. Seven percent of participants who wanted to go somewhere but could not cited transportation costs as the barrier.

Shafir and colleagues explored the experience of home-based primary care for homebound older people in the United States.55 A key theme that emerged was related to how the program impacted the costs of accessing medical care. Participants suggested that expenses related to transportation to medical appointments could be prohibitive, and that the home-based primary care program, covered by publicly funded insurance, eased the cost burden of accessing health care elsewhere. Ploeg and colleagues explored the experience of managing multiple chronic conditions for older people living in a Canadian community.62 They conducted interviews to gather the perspective of older people, caregivers, and health care providers. Participants noted that older people with multimorbidity, particularly those living in rural areas, had challenges accessing transportation to attend medical appointments. This was in a context where the participants attended frequent appointments due to their multiple health conditions, thus needed transportation often. Expenses related to transportation, along with expenses such as medication, were noted to impact decisions about how to spend limited resources, and impacted health and quality of life.63

Medical equipment and assistive devices

Medical equipment (eg, home oxygen delivery equipment, diabetic testing supplies, incontinence supplies) and assistive devices (eg, mobility aids) were also reported as out-of-pocket expenses. Two studies looked at out-of-pocket expenses related to incontinence specifically and noted the cost of supplies, such as incontinence pads, disposable pads, disposable diapers, disposable bed pads, and disposable gloves.43,69 Choi and colleagues noted that individuals experiencing neglect often went without cost-prohibitive medical supplies.41 Out-of-pocket costs for assistive devices included expenses such as purchasing mobility aids (eg, canes, walkers) and hearing and vision aids. de Craen and colleagues described the use of assistive devices by older people in The Netherlands.75 They found that devices used to support both mobility (43%) and personal care (27%) were often paid for out-of-pocket. Other sources included medical equipment and assistive devices as part of a combined measure of out-of-pocket expenses,60,70 reported actual costs of medical supplies,54 and identified expenses for medical supplies not covered by LTC insurance.68

Respite

Six studies included out-of-pocket expenses for respite care of older people experiencing frailty.50,51,53,54,68,70 Such expenses included adult day centers,51,54,70 short stays in residential care facilities,68,70 and other unspecified respite care.50,53,54

Home modifications

The sources that reported findings related to out-of-pocket expenses for home modifications described renovations or other significant changes to the home that enabled older people with frailty to adapt to changes in function. A study by Lien and Huang asked adult children of older people experiencing frailty in Taiwan about challenges in providing care.80 They found that the costs of adapting a home were often prohibitive and contributed to unsafe living circumstances for frail older people.80 Other studies included out-of-pocket expenses related to home modifications as part of combined measures of out-of-pocket expenses,70 expenses associated with providing an adult family living service,61 and the cost of services not covered by LTC insurance.68 Choi and colleagues noted that costs associated with home repairs (eg, leaking pipes, leaking roofs, broken toilets) sometimes precluded completing the repairs.41

Insurance

Two studies from Japan examined out-of-pocket expenses in the context of a country with a national LTC insurance program. Along with identifying expenses that were not covered by insurance, the studies reported expenses such as insurance copayments.67,68 Washio et al. found that caregivers reported being heavily burdened had higher insurance copayments than those with lower levels of burden.68 Nakabe et al. examined out-of-pocket expenses for caregivers of people with dementia by level of care need and found that copayments were related to care-need level, with caregivers of people with higher needs having higher costs.67 Insurance was also noted as an expense for adult family living programs61 and for people using social health management organizations.47 One study included insurance costs in measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses.70

Intergenerational financial transfer

One study conducted in China focused explicitly on intergenerational financial transfers. Liu and colleagues examined intergenerational informal support and financial transfers between older people and their children.71 Through a national survey, data were collected from almost 1700 older people with frailty.

Measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses

Several of the included sources used combined measures that were total spending amounts related to periods of time or types of expenses. Measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses included monthly out-of-pocket medical expenses,79 monthly caregiving costs,77 out-of-pocket spending on health care,44 privately paid expenses,82 out-of-pocket expenses over two weeks,60 expenses paid by individuals for health and social services in the 12 months preceding death,66 annual personal assistance expenditure,48 annual out-of-pocket spending,49 and out-of-pocket expenses over the past two years.53

Out-of-pocket expenses for select populations

Within the included studies, out-of-pocket expenses for two sub-populations were particularly common: people with dementia who were frail and caregivers of people who were frail.

Out-of-pocket expenses for people with Alzheimer disease and other dementias

Five of the included studies were focused on people with Alzheimer disease or other dementias. Taylor and colleagues reported on the total costs of care for older people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias living in the community, according to a national survey in the United States.57 They included an analysis of the out-of-pocket prescription drug costs for this population and found that while most costs were higher for people with more severe dementia, out-of-pocket prescription costs were not higher for people with more severe dementia. In contrast, Zencir and colleagues examined costs associated with Alzheimer disease through data collected from 42 people with Alzheimer disease and their caregivers in Turkey.81 While their analysis focused on total costs that included both direct and indirect costs, they also noted that out-of-pocket costs for medications increased with the severity of Alzheimer disease.

Nakabe and Huang examined the economic burden of dementia in Japan.67 They specifically collected data about out-of-pocket costs that were not reimbursed by the LTC insurance program. They found that out-of-pocket expenses were related to caregivers’ income, the functional ability of the people with dementia, and the age of the people with dementia. For people with dementia with the highest care needs, the average daily costs of care were estimated to be US$352, compared to US$95 for those at the lowest care-need level. A study by Moore and colleagues examined experiences of female caregivers of male veterans with dementia, and categorized data based on the number of limitations in completing ADLs experienced by the older person with dementia.50 The study found that caregivers of people with more limitations faced higher out-of-pocket expenses. For example, caregivers of people with more than seven limitations reported paying for an average of 19.8 hours of home health care, which resulted in average costs of US$164 per month. Veras and colleagues examined the out-of-pocket expenses of caregivers of people with dementia in Brazil.70 They found that expenditures varied by severity of disease and the number of other chronic diseases present.

Out-of-pocket expenses for caregivers

Seven studies examined out-of-pocket expenses for family and friend caregivers of older people with frailty. Two studies explored perspectives of caregivers and highlighted areas where caregivers spent significant amounts on the care of older people with frailty, and may benefit from further publicly funded support. Suen and Thang explored the experience of low-income caregivers of dependent older people in Singapore.78 They noted that while there were government subsidies that kept medical costs low, there were gaps in resources available to support transportation needs. They also identified administrative costs for caregivers, such as paying fees related to having medical certificates sent to necessary authorities. Veras and colleagues conducted a study in Brazil that examined out-of-pocket costs for family caregivers of older people with dementia.70 The authors found that, on average, caregivers spent 66% of the family's income on costs associated with caring for the person with dementia.

Washio examined factors that contributed to caregiver burden among caregivers of older people receiving regular hemodialysis treatment in Japan.68 While many of the services received were paid for by Japan's LTC insurance program, the study measured out-of-pocket costs, including copayments, of the insurance program.

Lien and Huang described the experiences of caregiving for intergenerational family members of older people in Taiwan.80 They found that some families struggled with the costs of supporting frail older relatives, noting costs associated with nutritious food, medical care, and home care. Similarly, Degiuli explored the experiences of caregivers of frail older people and noted expenses related to groceries, utilities, and home care.74 Moore and colleagues used a national database in the United States to examine the costs incurred by female caregivers of older male veterans with dementia.50 They found that, on average, caregivers paid more for care when the person with dementia had higher care needs.

In their study examining sources of strain and distress among caregivers of people older than 100 years in Portugal, Brandão and colleagues examined the relationship between monthly out-of-pocket costs and burden.77 The study reported monthly costs of caregiving, but did not report details on how the money was spent.

Out-of-pocket expenses as outcomes in the evaluation of policies, programs, and services

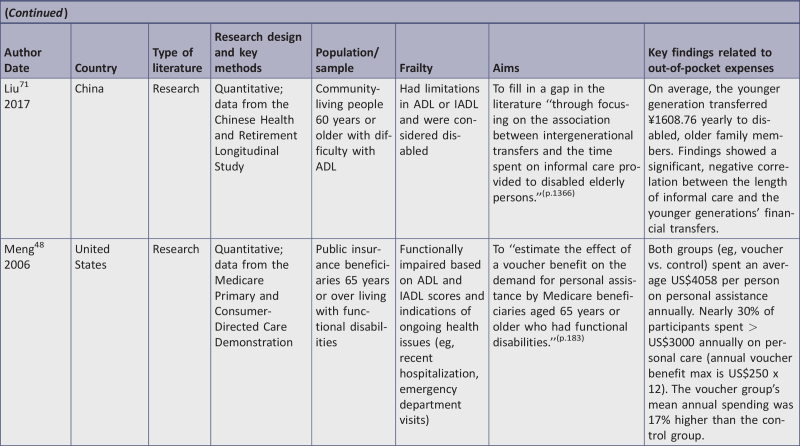

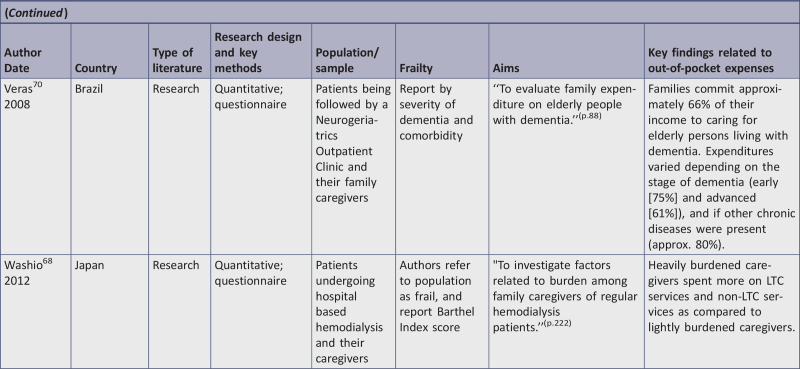

Another key area of the findings was related to the influence of various interventions on out-of-pocket expenses for older people living with frailty in the community. A summary of these sources can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of sources that discussed out-of-pocket expenses as outcomes in evaluating policies, programs, and services related to aging in place for frail older people

| Author Country |

Intervention (program/service/policy) | Brief description | Method of evaluation | Findings related to out-of-pocket expenses |

| Béland et al.60 Canada |

Community-based multidisciplinary teams | Provision of community-based multidisciplinary integrated care | RCT | No difference was found for out-of-pocket expenditures between control and intervention groups |

| Dosman and Keating61 Canada |

Program | Provision of high-level care for individuals in a home-like environment | Focus groups | Costs incurred for caregivers included insurance payments, safety equipment, and maintenance/repair expenses |

| Flood et al.65 UK |

Program | Community assessments provided by social workers and occupational therapists | Cost comparison | Costs for participants assessed by social workers were higher; however, the difference was significant only to caregivers |

| Leutz et al.47 US |

Social HMO program | Provision of community-based care services | Qualitative interviews | Some people were found to have expenses beyond program coverage (eg, home care, yard work) Described additional out-of-pocket payments associated with the program that varied according to need |

| Meng et al.48 US |

Voucher program | Vouchers used to reimburse personal assistance expenditures | Quantitative survey data | Intervention group had higher expenditures, and those with higher functional impairment had higher service usage |

| Moon et al.49 US |

Policy | Description of financial implications of older adults’ complex health needs | Policy analysis | Older people with complex needs have higher out-of-pocket expenses Describes proposed complex care option for Medicare |

| Parker and Hill82 UK |

Program | Home-based and day hospital rehabilitation | RCT | Cost analysis found no significant difference between total costs of intervention and control groups |

| Schwab et al.54 US |

Social HMO program | Provision of community-based care services | Gathering actual costs | Average annual estimated costs of services were found to be US$4900 out-of-pocket No comparison with group who received social HMO |

| Stuart and Hansen72 Denmark |

Policy | Description of care services for older people with frailty in Denmark | Policy analysis | Description of how public services and family caregivers cooperate to provide care Note that some out-of-pocket expenses occurred; however, overall sources provided adequate support |

HMO, health maintenance organization; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

While this review was open to policy papers that described the impact of policies on the out-of-pocket expenses of older people with frailty, we only identified two such sources. They provided information on how policies impact the experiences of people with frailty. Stuart and Hansen provided a description of LTC services for older people with frailty in Denmark.72 They described how public services and family caregivers work together to provide care for older people with frailty to meet their complex health and social needs, and described the various policies that supported this situation. They noted that older people at times paid out-of-pocket for household cleaning and meals (if they ate outside the home) but generally, public and family resources provided adequate support for them.

The second policy paper was an issue brief by Moon and colleagues that addressed the financial implications of complex health needs of older people in the United States, and proposed a benefit option as part of the Medicare public insurance program to cover home and community services associated with living in the community.49 The authors noted that older people with complex needs have higher out-of-pocket expenses than those with less complex needs. The next step, according to the authors, is to examine the financial implications of implementing such a program.

Of the seven research studies that reported on the evaluation of programs and services programs, three were conducted in the United States and included discussion of the costs borne by older people with frailty and their caregivers beyond what was covered by publicly funded insurance (ie, Medicare and Medicaid).47,48,54 Two included studies examined social health maintenance organizations (HMOs), which provided community-based LTC.47,54 Leutz and colleagues described the experiences of older people using such a program, noting that some people had expenses for services above and beyond what were covered by the program, such as home care, transportation, and yard work.47 They also described the out-of-pocket costs associated with being part of the social HMO whereby members of the program paid a monthly premium that varied according to their need, as well as copayments for specific services. Schwab and colleagues examined costs associated with a specific social HMO.54 These authors calculated what it would cost to pay out-of-pocket for each of the services the program offered. The actual costs reported were obtained by surveying service and supply providers in the community, and reflect an average of several responses. They found that the services would cost an average of $4900 out-of-pocket per year, but did not include a comparison to the cost of delivering the service. Also in the United States, Meng and colleagues evaluated the effect of a voucher program on the out-of-pocket expenditures for personal assistance of older people in the community.48 The study reported on an RCT of a voucher program that reimbursed personal assistance expenditures. The study found that the intervention group had higher expenditures, and that persons with more functional impairment had higher service use than those without.

Two research studies from the United Kingdom examined programs provided by health care professionals that supported older people with frailty in the community. Flood and colleagues compared the costs and outcomes of community assessments led by social workers and occupational therapists.65 The authors found that costs for participants being assessed by social workers were higher, although the difference was only significant for costs incurred by caregivers. Parker and colleagues conducted an RCT to determine the effectiveness of home-based rehabilitation compared to day hospital rehabilitation for older people, and included a cost minimization analysis of total costs of care after six and 12 months.64 The cost minimization analysis found no statistically significant differences in the total costs between the intervention and control groups.

In Canada, Béland and colleagues reported on an RCT aimed to determine the effectiveness of an intervention comprised of community-based multidisciplinary teams providing integrated community care to older people with frailty.60 The authors analyzed the effect of the intervention on out-of-pocket expenditures including “nursing, homemaker, over-the-counter medication, technical aids, and transport to access health and social services.”(p.370) They found that there were no differences in out-of-pocket expenditure between the control and intervention groups. Also from a Candian context, Dosman and Keating studied the experience of caregivers in an adult family living program.61 Adult family living programs, also called adult foster care, offer people who are in need of high levels of care a home-like environment in the community where they receive accommodation, food, and other care from a paid caregiver in the caregiver's home. The authors asked people filling the role of caregiver in the program what types of costs they incurred, and found that insurance payments, safety equipment, and maintenance and repair expenses were important to participants.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to map and describe the evidence on out-of-pocket expenses incurred by older people with frailty, and their caregivers, to support aging in place. We categorized the types of expenses that have been studied and identified unique expenses that individuals may face. We found that people with dementia and caregivers were subgroups that were often explored in relation to out-of-pocket spending for aging in place. The body of literature had few studies that could be compared in terms of research design or outcome measures, so there is limited opportunity for further qualitative or quantitative systematic reviews.

Literature reporting on the out-of-pocket expenses associated with living in the community for people with frailty and their caregivers largely focused on support for the functional changes the person was experiencing, such as home care, housekeeping, transportation, and meal preparation. However, there were also various expenses identified that have not been regularly recognized in health and social care literature, such as dental care, yard maintenance, pet care, hair care, and legal services. Such services and supports contribute to the ability of people with frailty to maintain their safety and dignity as they experience health and functional changes. None of the included studies explicitly examined costs associated with maintaining meaningful leisure activities for people with frailty. Activities such as participating in social gatherings or maintaining hobbies may also be associated with out-of-pocket expenses, and are important for ensuring quality of life for people with frailty.83,84

The review revealed that the policy context was particularly important to the experiences of older adults with frailty and their caregivers with out-of-pocket expenses. While we sought to include policy documents in order to better understand how policies impacted out-of-pocket expenses, only two such documents were ultimately included. There were, however, notable differences between countries in how individuals experienced out-of-pocket expenses that were directly related to the policy context of the country. For example, there is an LTC insurance program in Japan that covers some costs for people with frailty in the community, reflecting the high proportion of older people in that country. There were also several studies conducted in the United States that referenced the public insurance programs (ie, Medicare and Medicaid), and this literature often reported on out-of-pocket expenses not covered by the programs.

Few studies used out-of-pocket expenses as outcomes in the evaluation of health care interventions to support older people with frailty. This was surprising as cost effectiveness is an important consideration in the implementation of such programs. This finding may reflect the focus on health care and societal costs in cost-effectiveness studies. The findings suggest that out-of-pocket spending is important to the experiences of many older people experiencing frailty and their caregivers. Individuals balance various types of costs and benefits when considering where to live. Developing a more robust understanding of out-of-pocket costs for aging in place will support the evolution of health and social care systems that are reflective of the population needs. In future intervention research, it will be important to include out-of-pocket expenses in cost analyses.

The review also revealed that there is no consistent measure of out-of-pocket expenses used in the literature on older people with frailty. While there were several measures of combined out-of-pocket expenses, there was very little overlap in these measures. A standardized approach to measurement would support comparisons across studies, populations, and interventions, as well as provide an opportunity for further systematic review and meta-analysis. The UN Sustainable Development Goals have an indicator related to out-of-pocket spending on health care as a proportion of total income.85 It may be useful to report out-of-pocket spending for older people with frailty in a similar manner. In this review, Veras and colleagues reported out-of-pocket expenses as a percentage of the family's monthly income,70 and Moon and colleagues reported yearly out-of-pocket spending by income.49 These may be important methods to consider for a standardized approach to reporting out-of-pocket expenses.

While we expected the review to identify many studies that included established definitions of frailty, this was not the case. We adopted a broad definition of frailty so we could incorporate evidence from diverse disciplinary and methodological perspectives, and could discuss how various definitions were used in literature reporting on out-of-pocket expenses. Of the included studies, two used an established operational definition of frailty; both Son and colleagues79 and Brandão and colleagues77 used the phenotype model.21 However, most studies that used the term “frail” to describe their population did not refer to a published definition of frailty. This review therefore further reinforces the need for clarification of the term “frailty” in the literature.

Conclusions

The literature demonstrates that out-of-pocket expenses are an important consideration for older people with frailty, and affect their ability to stay in their homes and communities. These expenses have implications for their health and well-being. While many sources noted out-of-pocket expenses related to home care, a variety of sources of expenses were ultimately noted, including those specific to health experiences (eg, medical supplies, medication), and those related to the particular living situation of individuals (eg, transportation, yard maintenance). The experience of out-of-pocket spending varied across countries. Caregivers of older people with frailty experience the effects of out-of-pocket expenses, and older people with dementia have unique needs impacting out-of-pocket expenses.

The review was limited by the inclusion of articles only written in English and French due to finite resources and an inability to translate literature. Limiting our search to sources published after 2001, when a seminal definition of frailty was published, may have unnecessarily limited our findings.

Implications for research

More research is needed on the contextual factors that impact the experiences of out-of-pocket costs for older people, notably the micro-, meso- and macro-level policy context. There is also a need for consensus around reliability, and consistently measuring out-of-pocket expenses so that there can be meaningful comparisons across research studies, populations, and contexts.

Implications for practice

This review supports the need for nurses and other health care providers to ask about out-of-pocket expenses when working with older people experiencing frailty. It is important for providers to be aware of the contextual factors that contribute to out-of-pocket spending, such as local policies, and also to stay abreast of resources to support people with frailty and their caregivers with out-of-pocket expenses.

Funding

We received financial support for this review from CIHR SPOR PIHCI Network Knowledge Synthesis Grant, the Government of Nova Scotia, Department of Health and Wellness, and School of Occupational Therapy, Dalhousie University. We are also grateful for support from the Aging, Community and Health Research Unit at McMaster University. The funders did not have any input into the review.

Appendix I: Search strategy

Searches run September 27, 2019

Appendix II: Data extraction instrument

Reviewer: _______________________________________________

Date: ___________________________________________________

Appendix III: Studies ineligible following full-text review

Reason for exclusion: Not a research study or policy document (n = 173)

Anon. Home care may lead to cost-efficient management of frail elderly patients. Dis Manag Advis. 2006;12(10):118–19.

Anon. One million older people face brunt of care with little support from health or social services. J Nurs Manag. 2002;10(1):57–8.

Armentano R, Kun L. Multidisciplinary, holistic and patient specific approach to follow up elderly adults. Health Technol (Berl). 2014;4(2):95–100.

Bauer JM, Sousa-Poza A. Impacts of informal caregiving on caregiver employment, health, and family. J Popul Ageing. 2015;8(3):113–45.

Bell H. In the comfort of home. Minn Med. 2013;96(1):24–9.

Bennett JA, Flaherty-Robb MK. Issues affecting the health of older citizens: meeting the challenge. Online J Issues Nurs. 2003;8(2):9.

Bibgy C. Ageing people with a lifelong disability: challenges for the aged care and disability sectors. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2002;27(4):231–41.

Bjornsdottir K. From the state to the family: reconfiguring the responsibility for long-term nursing care at home. Nurs Inq. 2002;9(1):3–11.

Bloom S, Sulick B, Hansen JC. Picking up the PACE: the affordable care act can grow and expand a proven model of care. Generations. 2011;35(1):53–5.

Boling PA, Leff B. Comprehensive longitudinal health care in the home for high-cost beneficiaries: a critical strategy for population health management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(10):1974–6.

Bossard M, Arbuz G. [Home care, a choice for the elderly and his family?] Soins Gerontol. 2003;(39):18–22. French.

Bottomley JM. Energy assistance programs; keeping older adults housed and warm. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2001;17(1):71–81.

Branca S, Bennati E, Ferlito L, Spallina G, Cardillo E, Malaguarnera M, et al. The health-care in the extreme longevity. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(1):32–4.

Brennan M. Impairment of both vision and hearing among older adults: prevalence and impact on quality of life. Generations. 2003;27(1):52.

Brookman A, Kimbrel D. Families and elder care in the twenty-first century. Future Child. 2011;21(2):117–40.

Buntin MB, Huskamp H. What is known about the economics of end-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries? Gerontologist. 2002;42:40–8.

Cagle JG, Munn JC. Long-distance caregiving: a systematic review of the literature. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2012;55(8):682–707.

Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. A home for life: Edmonton initiative offers a blueprint for houses that work for every stage of life. Canada: CMHC, 2017.

Carey T, Kilkenny E, Shea DO, Lee H, Sinnott K. What price choice-cost of facilitating the preference of frail older people. Where should money be spent? Age Ageing. 2017;46:iii13.

Carpenter BD, Mak W. Caregiving couples. Generations. 2007;31(3):47–53.

Ceci C, Purkis ME. Means without ends: justifying supportive home care for frail older people in Canada, 1990–2010. Soc Health Illn. 2011;33(7):1066–80.

Cheek P, Nikpour L, Nowlin HD. Aging well with smart technology. Nurs Adm Q. 2005;29(4):329–38.

Chien-Wen T, Phillips RL, Green LA, Fryer GE, Dovey SM. What physicians need to know about seniors and limited prescription benefits, and why. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(2):212.

Clegg A, Grout G, Buswell J, Lewis D, Barnes M, Naxarko L, et al. What has been your experience of the impact of the Community Care Act and reimbursement, and how can we ensure that it is applied in ways that meet patients’ needs? Nurs Older People. 2004;16(9):40–1.

Connolly S. Housing tenure and older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2012;22(4):286–92.

Conwell Y, Sirey JA, Snowden M. Aging services network providers: partners in mental health care for seniors. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):S23–4.

Cook L, Wood A, Burns E. Care closer to home: an evidence-based approach for straitened times. Br J Hosp Med. 2018;79(10):546–7.

Counsell SR. Integrating medical and social services with GRACE. Generations. 2011;35(1):56–9.

Criddle RA, Flicker L. Helping older people to remain in their own homes. Med J Aust. 2001;174(6):266–7.

Cudennec T, Rogez E. [Caring for the caregivers, an essential key for home care]. Soins Gerontol. 2006;(59):13. French.

Currie CT. Health and social care of older people: could policy generalise good practice? J Intergr Care. 2010;18(6):19–26.

Dancy Jr J, Ralston PA. Health promotion and black elders: subgroup of greatest need. Res Aging. 2002;24(2):218–42.

Davis K, Willink A, Schoen C. Integrated care organizations: Medicare financing for care at home. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(11):764–8.

Dawson WD, Nash M. Aging with serious mental illness: one state's response. Generations. 2018;42(3):63–70.

De Jonge E, Taler G. Is there a doctor in the house? Caring. 2002;21(8):26–9.

Dilks S, Emblin K, Nash, Jefferies S. Pharmacy at home: Service for frail older patients demonstrates medicines risk reduction and admission avoidance. Clinical Pharmacist. 2016;8(7):2016.

Dix J. Paying for care – the Japanese model. Work Older People. 2005;9(1):24–6.

Dolan TA. Access to care for older Americans. N Y State Dent J. 2010;76(5):34–7.

Doling J, Ronald R. Meeting the income needs of older people in East Asia: using housing equity. Ageing Soc. 2012;32(3):471–90.

Droz JP. Rules allowing the reimbursement of cares of elderly cancer patients in France. Crit Rev Oncog. 2003;48(2):145–9.

Dyer CB, Pickens S, Burnett J. Vulnerable elders: when it is no longer safe to live alone. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298(12):1448–50.

Ebrahim S. New beginning for care for elderly people? Proposals for intermediate care are reinventing workhouse wards. BMJ. 2001;323(7308):337–9.

Economist, The. Till death do us part: a new market for floating hotels [internet]. The Economist. 2004 Oct 30 [cited 2021 Oct 5]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/business/2004/10/28/till-death-us-do-part.

Edwards-Tate L. Clearing up misconceptions and imperceptions of privately paid home care. Caring. 2011;30(4):36–9.

Elon RD. Reforming the care of our elders: reflections on the role of reimbursement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(2):117–20.

Evans M. Home-care demands rise: medicaid key to helping seniors remain in abodes. Mod Healthc. 2006;36(28):17.

Fange AM, Oswald F, Clemson L. Aging in place in late life: theory, methodology and intervention. J Ageing Res. 2012;2012:547562.

Farag I, Sherrington C, Ferreira M, Howard K. A systematic review of the unit costs of allied health and community services used by older people in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(69).

Fazzi R, Harlow L. The incredible future of home care and hospice. Caring. 2007;26(3):36–45.

Feikema M. Housing and social care for the elderly in central Europe. Czech Sociol Rev. 2014;50(6):1012–14.

Firman J, Nathan S, Alwin R. Meeting the needs of economically disadvantaged older adults: a holistic approach to economic casework. Generations. 2009;33(3):74–80.

Fortinsky RH, Robinson JT. Targeting function at home in older adults: how to promote and disseminate promising models of care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(3):433–5.

Francis SA, Barnett N, Denham M. Switching of prescription drugs to over-the-counter status. Is it a good thing for the elderly? Drugs Aging. 2005;22(5):361–70.

Gable M. Communication helps seniors age in place. Teamwork is vital in keeping satisfaction high, cost low. Health Prog. 2009;90(6):29–31.

Garfinkel D. Overview of current and future research and clinical directions for drug discontinuation: psychological, traditional and professional obstacles to deprescribing. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(1):16–20.

Garrett SL, O’Brien JG, Miles TP. Letter to the editor: Quality of care for vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(3):219–20.

Giarchi GG. Older people ‘on the edge’ in the countrysides of Europe. Soc Policy Adm. 2006;40(6):705–21.

Giovannoli L. Home care: changes and concerns. Caring. 2006;31(8):30–3.

Gitlin LN. Conducting research on home environments: lessons learned and new directions. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):628–37.

Gitlin LN, Szanton SL, Hodgson NA. It's complicated-but doable: the right supports can enable elders with complex conditions to successfully age in community. Generations. 2013;37(4):51–61.

Golden AG, Tewary S, Dang S, Roos BA. Care management's challenges and opportunities to reduce the rapid rehospitalization of frail community-dwelling older adults. Gerontologist. 2010;50(4):451–8.

Gonyea JG, Melekis K. Women's housing challenges in later life: the importance of a gender lens. Generations. 2017;41(4):45–53.

Gonzalez L. A focus on the Program of the All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). J Aging Soc Policy. 2017;29(5):475–90.

Goodacre K, McCreadie C, Flanagan S, Lansley P. Enabling older people to stay at home: the costs of substituting and supplementing care with assistive technology. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71(4):130–40.

Gottlieb AS, Caro FG. Extending the effectiveness of home care for elders through low-cost assistive equipment. Policy Brief (Cent Home Care Policy Res). 2001;(6):1–6.

Grundy E. Ageing and vulnerable elderly people: European perspectives. Ageing Soc. 2006;26:105–34.

Guillard G. The elderly person at home and his relation to money. Soins Gerontol. 2003;(39):37–9.

Haas LB. Caring for community-dwelling older adults with diabetes: perspectives from health care providers and caregivers. Diabetes Spectr. 2006;19(4):240–4.

Haggis C, Sims-Gould J, Winters M, Mckay H. I’d rather stay: documentary video for multi-stakeholder discussions on the barriers and facilitators to growing old in your neighborhood [internet]. Canadian Association on Gerontology; 2014 [cited 2021 Oct 5]. Available from https://cagacg.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/CAG2014_Program.pdf.

Halamandaris VJ. Aging with health and dignity. Caring. 2004;23(10):6–27.

Halamandaris VJ. Doing the right thing for our nation's elderly, infirm, and disabled. Caring. 2011;30(4):48.

Hallberg IR, Kristensson J. Preventive home care of frail older people: a review of recent case management studies. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13(6B):112–20.

Hansen JC. Community and in-home models. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):69–72.

Henderson EJ, Caplan GA. Home sweet home? Community care for older people in Australia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9(2):88–94.

Hebert R. Home care: from adequate funding to integration of services. Healthc Pap. 2009;10(1):58–83.

Hernandez M. Assisted living in all of its guises. Generations. 2005;29(4):16–23.

Heumann LF. Assisted living for lower-income and frail older persons from the housing and built environment perspective. J Hous Elderly. 2004;18(3/4):165–78.

Hood FJ. Medicare's home health prospective payment system. South Med J. 2001;94(10):986–9.

Hostetter M, Klein S, McCarthy D. Aging gracefully: the PACE approach to caring for frail elders in the community. New York, NY: Common Wealth Fund, 2016. 12 p.

Hurley D. Accurately attributing reduced hospital admissions to medications optimisation? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27:8.

Iverson RJ. The silent crisis: women and the need for long-term care insurance. Part 2. Caring. 2003;22(11):32–6.

Jaber R, Starr R. “Please help me” – a caregiver's stress. J Am Geratr Soc. 2015;63:S28.

Johnson RW. Housing costs and financial challenges for low-income older adults. Washington, DC; Urban Institute, 2015. p. 16.

Johnson RW, Mommaerts C. Will health care costs bankrupt aging boomers? Washington, DC; Urban Institute, 2010. p. 46.

Kane RL, Kane RA. HCBS: the next thirty years. Generations. 2012;36(1):131–4.

Kang J-M, Yeo BK, Cho S-J, Cho S-E, Yun S, Kim J, et al. Healthcare-seeking behaviors of patients with in Incheon City: a preliminary study. Intr Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:S81–5.

Keefe J, Glendinning C, Fancey P. Financial payments for family carers: policy approaches and debates. In: Martin-Matthews A, Phillips JE, editors. Aging and caring at the intersection of work and home life: blurring the boundaries. New York: Taylor and Francis Group; 2008. p. 185–206.

Keister D, Shvetzoff S. Allowing the elderly to age in place. In Portland, OR, a Catholic-sponsored PACE site provides community-based health care services. Health Prog. 2004;85(6):50–3.

Kim EHW, Cook, PJ. The continuing importance of children in relieving elder poverty: evidence from Korea. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(6):953–76.

Kim KI, Gollamudi SS, Steinhubl S. Digital technology to enable aging in place. Exp Gerontol. 2017;88:25–31.

Kinosian B, Edes T. Home based primary care for frail, homebound veterans as a model for independence at home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:S116.

Kinosian B, Edes T, Davis D, Makineni R, Intrator O. Independence at home (IAH) criteria successfully targets frail, costly veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:S128.

Kinosian B, Meyer S, Yudin J, Danish A, Touzel S. Elder partnership for all-inclusive care (Elder-PAC): 5-year follow-up of integrating care for frail, community elders, linking home based primary care with an area agency on aging (AAA) as an independence at home (IAH) model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:S6.

Knijn T, Verhagen S. Contested professionalism: payments for care and the quality of home care. Adm Soc. 2007;39(4):451–75.

La Martina D. Aging in place home renovations: are they worth the costs? [internet]. 2015 [cited 2021 Sep 15]. Available from: https://www.thinkadvisor.com/2015/05/04/aging-in-place-are-home-renovations-worth-the-costs/.

Lamorthe C. How much does it cost to keep a dependent person at home? Soins Gerontol. 2004;(46):5–7.

LaPorte M. Quality, funding issues hit home care. Provider. 2009;35(8):22–32.

Lecovich E, Doron I. Migrant workers in eldercare in Israel: social and legal aspects. Eur J Soc Work. 2012;15(1):29–44.

Leng Leng T, Wei-Jun, JY. Introduction of special issues of journal of cross cultural gerontology on elder-care issues in Southeast and East Asia. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2018;33(2):137–42.

Libson N. The sad state of affordable housing for older people. Generations. 2005. 29(4):9–15.

Limpawattana P, Chindaprasirt J. Caregiver burden of older adults: a southeast Asia aspect. In: Thurgood A and Schuldt K, editors. Caregivers: challenges, practices and cultural influences. New York, Nova Science Publishers, Inc. 2020. p.195–206.

Lloyd-Sherlock P. Identifying vulnerable older people: insights from Thailand. Ageing Soc. 2006;26:81–103.

Lyn MJ, Johnson FS. Just for us: in-home care for frail elderly and disabled individuals with low incomes. N C Med J. 2011;72(3):205–6.

Mahoney KJ, Simon-Rusinowitz L, Simone K, Zgoda K. Cash and counseling: a promising option for consumer direction of home- and community-based services and supports. Care Manag J. 2006;7(4):199–204.

Marrelli TM. Prospective payment in home care: an overview. Geriatr Nurs. 2001;22(4):217–8.

Mason A, Weatherly H, Spilsbury K, Golder S, Arksey H, Adamson J, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of respite for caregivers of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):290–9.

Mason DJ. Long-term care: investing in models that work. JAMA. 2017;318(16):1529–30.

Masotti P, Fick R, Johnson-Masotti A, MacLeod S. The aging population and natural occurring retirement communities (NORCs); local government, healthy aging, and healthy-NORCs. Alaska Med. 2007;42(2):85–8.

Maxwell C, Rothman R, Simmons S, Wolever R, Given B, Miller R, et al. Development of a frailty-focused communication aid for older adults. Palliat Med. 2018;32(1):155.

McCann P. Explaining about…building to last. Work Older People. 2008;12(2):9–11.

McGuire LC, Anderson LA, Talley RC, Crews JE. Supportive care needs of Americans: a major issue for women as both recipients and providers. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;6:784–9.

Mechkat C, Bouldin B. What sort of architecture should there be for a society weakened by old-age? or older people's spaciality between medico-social establishments and living space for all. Gerontol Soc. 2006;119(4):39–73.

Meucci MR. Home modifications: access, funding and effectiveness. National Institute of Health; 2014.

Meyer MH, Roseamelia C. Emerging issues for older couples: protecting income and assets, right to intimacy, and end-of-life decisions. Generations. 2007;31(3):66–71.

Michel J-P, Robine J-M, Herrmann F. Tomorow, who will take care of the elderly? The oldest old support ratio. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2010;194:793–804.

Ming-Sheng W, Chi-Fang W, Wang MS, Wu CF. Assisting caregivers with frail elderly in alleviating financial hardships. Soc Work Public Health. 2018;33(6):396–406.

Miskelly FG. Assistive technology in elderly care. Age Ageing. 2001;30(6):455–8.

Mithers C. How to plan for your parent's future. Ladies Home J. 2008;25(11):62–6.

Mohammad TS. The elderly and family change in Asia with a focus in Iran: a sociological assessment. J Comp Fam Stud. 2006;37(4):583-XI,610.

Montgomery RJV, Rowe JM, Kosloski K. Chapter 16: Family caregiving. In: Blackburn JA, Dulmus CN, editors. Handbook of gerontology: evidenced-based approaches to theory, practice and policy. Hobeken, NJ:John Wiley and Sons Inc, 2007. p. 426–54.

Moore DJ, Appleby J, Meyer J, Myatt J, Oliver D, Ritchie-Campbell J. Frail older people improve their care. Pave the way for better elderly care. Health Serv J. 2014;124(6400):26–9.

Moraitou M, Pateli A, Fotiou S. Smart health caring home: a systematic review of smart home care for elders and chronic disease patients. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;989:255–64.

Nelson A, Powell-Cope G, Gavin-Dreschnack D, Quigley P, Bulat T, Baptiste AS, et al. Technology to promote safe mobility in the elderly. Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;39(3):649–71.

Nishita CM, Pynoos J. Retrofitting homes and buildings: improving sites for long-term-care delivery. Generations. 2005;29(4):52–7.

Norlander L. The future of advance care planning. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2003;15(2):136–9.

Northridge ME, Levick N. Preventing falls at home: transforming unsafe spaces into healthy places for older people. Generations. 2003;26(4):42–7.

Ohwa M, Chen LM. Balancing long-term care in Japan. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2012;55(7):659–72.

O’Toole RE. Integrating contributory elder-care benefits with voluntary long-term care insurance programs. Empl Benefits J. 2002;27(4):13–6.

Overend L, Gawith J, Carruthers L. ‘Expensive’ ultra-long acting insulin: is it cost effective in elderly patients with brittle diabetes? Diabet Med. 2016;33:187–8.

Pan CX, Chai E, Farber J. Myths of the high medical cost of old age and dying. Int J Health Serv. 2008;38(2):253–75.

Papaioannou ESC, Raiha I, Kivela SL. Self-neglect of the elderly. An overview. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18(3):187–90.

Parikh RB, Montgomery A, Lynn J. The Older Americans Act at 50 – community-based care in a value-driven era. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):399–401.

Park K-S. Consecrating or desecrating filial piety?: Korean elder care and the politics of family support. Dev Soc. 2013;42(2):287–308.

Pedlar D, Lockhart W, Macintosh S. Canada's veterans independence program: a pioneer of “aging at home”. Healthc Pap. 2009;10(1):72–7.

Petter Askheim O. Developments in Direct Payments. Ageing Soc. 2007;27:167–9.

Pierce CA. Home health care. Program of all-inclusive care for the elderly in 2002. Geriatr Nurs. 2002;23(3):173–4.

Pochagina O. The aging of the population in the PRC: sociocultural and sociopsychological aspects. Far East Aff. 2003;31(2):79–95.