Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic is an alarm call to all on the risks of zoonotic diseases and the delicate relationship between nature and human health. In response, China has taken a proactive step by issuing a legal decision to ban consumption of terrestrial wildlife. However, concerns have been raised and opponents of bans argue that well-regulated trade should be promoted instead. By analyzing China’s legal framework and management system regulating wildlife trade, together with state and provincial-level wildlife-trade licenses and wildlife criminal cases, we argue that current wildlife trade regulations do not function as expected. This is due to outdated protected species lists, insufficient cross-sector collaboration, and weak restrictions and law enforcement on farming and trading of species. The lack of quarantine standards for wildlife and increased wildlife farming in recent years pose great risks for food safety and public health. In addition, wildlife consumption is neither required for subsistence nor an essential part of Chinese diets. All these facts make the ban necessary to provoke improvement in wildlife management, such as updating protected species lists, revising laws and changing consumption behaviors. Nonetheless, the ban is not sufficient to address all the problems. To sustain the efficacy of the change, we propose that a long-term mechanism to reduce the demand and improve effective management is needed.

Xiao and colleagues argue that the dysfunctional licensing system and the lack of quarantine standards for wildlife trade make China’s wildlife consumption ban a necessary response to the COVID-19 pandemic and for biodiversity conservation.

Main Text

The connection between COVID-19 and wildlife1, 2, 3 has led to global concern about zoonotic diseases4 and reflection on human–nature relationships5. It has been revealed that the spillover of zoonotic pathogens and biodiversity losses share the same causes6. A cost-effective measure to prevent the next zoonotic pandemic relies on the protection of natural habitats, such as tropical forests, and a curb on wildlife trade7. In order to reduce current and future risks of pandemics, as well as to safeguard ecological security, a legal decision (hereafter ‘the decision’) issued by the Standing Committee of People’s Congress of China in February 2020 called for stopping wildlife consumption and related trade8. The decision aims to reduce the risk to public health and ecological degradation from the excessive consumption of wildlife, including initiating the process of amending relevant laws. It is an emergency measure that provides a legal ground to ban the food consumption and clamp down on illegal wildlife trade with “aggravated punishment” until laws are amended, which is currently in progress. It is not a blanket ban on wildlife trade; rather, it only prohibits the consumption of terrestrial wildlife and farmed populations for food. Neither aquatic wildlife nor non-edible uses such as for medicine or pets are banned. The decision also allows the consumption of certain terrestrial wildlife with mature farming techniques and low health risks. The legal pathway is through the listing in the Catalogue of livestock and poultry genetic resources managed by the Ministry of Agriculture (Supplemental Information).

However, concerns have been expressed9, 10, 11, 12. Here we analyze why a ban is necessary in China and how its efficacy can be sustained in the future and contribute to global wildlife conservation and human health.

Why is the ban an appropriate choice for China?

There have always been heated debates about bans on bushmeat or wildlife trade in the conservation community13, 14, 15, 16, 17. The opponents of bans argue that well-regulated trade could promote sustainable wildlife use, especially for the benefit of local communities, and at the same time alleviate the pressure on wild populations13 , 15. Effective management is crucial for the success of this mechanism16. However, the Chinese legal wildlife trade management system does not function as expected because of outdated protected species lists, insufficient cross-sector collaboration and the inability to distinguish legal and illegal wildlife in the market18. Besides, the lack of quarantine standards for wildlife and increasing wildlife farms in recent years raise concerns over food safety and public health. In addition, wildlife consumption is neither needed for subsistence of local communities nor essential for Chinese diets. Thus, in these contexts, the ban, with proper compensations to the wildlife farming industry, could be a cost-effective measure to prevent future outbreaks of zoonotic diseases considering the current dysfunctional management system.

The dysfunctional licensing system for legal wildlife trade

Sustainable use depends on frequent and accurate assessments of population status19. However, scientific knowledge does not feed in a timely way into the Wildlife Protection Law in China, which only protects 60% of Chinese species20. The List of wildlife under special state protection and the List of terrestrial wildlife with beneficial or of important ecological, scientific and social values define the scope of the species to be protected by the law. Unfortunately, neither has been updated since 2003, regardless of significant population changes and new findings in species taxonomy. About one-fourth of the threatened species are not properly protected and need to be up-listed with a higher level of legal protection. Besides, these two lists miss out nearly 200 threatened terrestrial species identified by the IUCN Red List20.

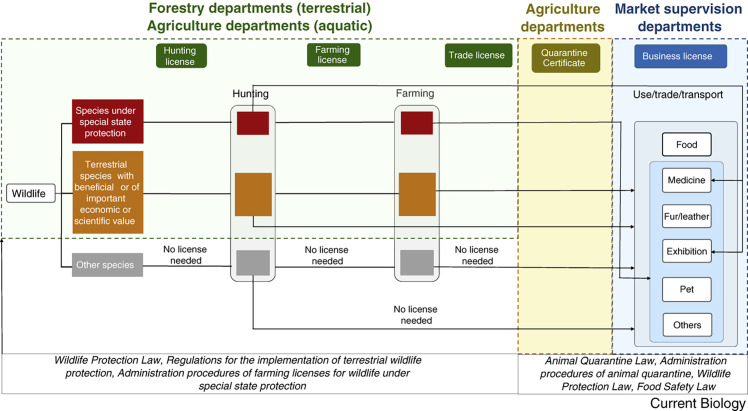

China’s Wildlife Protection Law, issued in 1987 and revised in 2016, adopts a supply-side approach through legalizing and regulating wildlife trade21 with a complex license system (Figure 1 ). With a license, all species could be farmed and then utilized or traded. There were no science-based restrictions and standards on which species can be farmed that considered the impact on wild populations and health risks. The only exception is the food consumption of Species under special state protection, unless they are included in the List of farmed species under special state protection. There were many loopholes in the licensing system: “for species under special state protection, only farmed individuals that were captive-bred for at least two generations could be traded. For other species, wildlife utilization should concentrate on farmed individuals and should benefit wild populations.” These statements in wildlife law and the licensing system established an ambiguous situation. As long as one claims or tags the animals as farmed, trade becomes legal because there are very limited ways to differentiate between wild-sourced and farmed individuals. The farming license has no expiration date or limitations on the quantity of farmed individuals. This means that with a license, illegally caught wildlife could be easily sold in the market. Due to the judicial difficulties to distinguish legally and illegally sourced wildlife, punishment for laundering activities is normally just an administrative penalty, not the withdrawal of licenses or criminal punishment. The license system fails as farming and trade licenses usually act as the disguise for frequent wildlife laundering activities22 , 23, which harms lawful farmers as well.

Figure 1.

Legal pathways for wildlife trade under the Wildlife Protection Law before the ban.

China’s Wildlife Protection Law adopts a supply-side approach through legalizing and regulating wildlife trade with a complex license system. The current system is distributed across different departments related to wildlife management, quarantine, food safety and market supervision. ‘Other species’ in the grey box are not regulated by any laws for hunting or farming.

The insufficient cross-sector collaboration has weakened market supervision, judicial forensics and law enforcement. The current management and license systems related to wildlife management, quarantine, food safety and market supervision are distributed across different departments (Figure 1). Deprived of expertise, inspectors from the Market Supervision Department cannot differentiate wildlife species, leading to a lack of oversight of wildlife trade. Department of Agriculture has insufficient wildlife veterinarians to carry out quarantines, leaving the door open for uninspected animals to be traded. Furthermore, the lack of understanding of the linkage between wildlife and human health once impeded these departments to actively engage with wildlife trade management, which hugely reduces the effectiveness and coverage of these regulations.

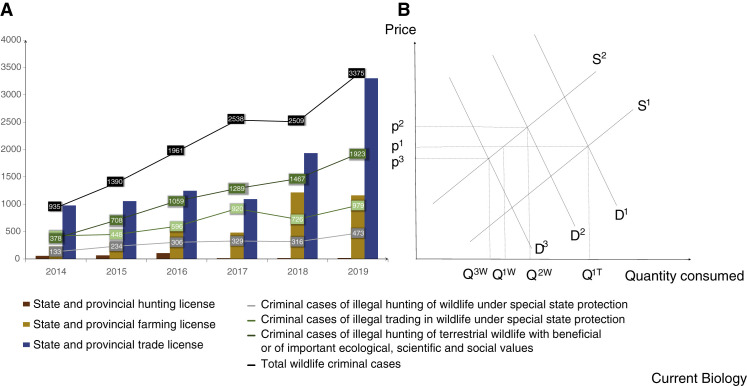

Wildlife farming was expected to assist in reaching the goal of poverty alleviation24. Current laws encourage wildlife utilization21. The government supports the development of wildlife farming industries, which was reflected by petty loan policies and widely broadcasted China Central TV programs on successful wildlife farmers and training courses to attract rural people joining the industry. It has stimulated a boom in wildlife farming with or without licenses. Although more new farming and trade licenses are issued each year, we observe an increase in poaching and illegal wildlife trade cases, suggesting a potential failure of “wildlife utilization should concentrate on farmed individuals and should benefit wild populations” stated in the law (Figure 2 A).

Figure 2.

Wildlife licenses, wildlife crime and potential impact of a wildlife ban.

(A) The number of wildlife licenses and wildlife criminal cases in 2014–2019. Although more new farming and trade licenses are issued each year, poaching and illegal wildlife trade cases are still increasing, suggesting a potential failure of the current supply-side approach. (Data source: websites of national level and all provincial level Forestry Bureaus of China, China judgements online). (B) The current wildlife trade ban will cut the extra supply from farms (S1−>S2) and in the meantime suppress demand from D1 to D2 or D3 by adding stigma effect and raising the cost of consuming the species. If the demand was only suppressed to D2, the price will increase from p1 to p2 and the quantity consumed from the wild will increase from Q1W to Q2W. If the demand was further suppressed to D3, the price will decrease from p1 to p3 and the quantity consumed from the wild will decrease from Q1W to Q3W.

Lack of quarantine protocols

From the 13121 trade licenses released by state (n = 6463, 2001–2020) and provincial level Forestry Bureaus (n = 6658, 2007–2020), there are 254 species traded for different commercial purposes. By comparing the species list with the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) World Animal Health Information System (WAHIS)-Wild interface database (2008–2019), 69 species have been identified as possible hosts or vectors for at least one zoonotic disease (Supplemental Information).

Quarantine safeguards food safety and public health. However, huge gaps exist in the wildlife trade system. All wildlife is required to be quarantined before entering markets, yet there is no quarantine protocol specifically designed for wildlife in China due to insufficient research on wildlife pathogens and diseases. Wildlife in similar groups as domestic species could refer to the existing 13 production place quarantine protocols for livestock and poultry, which applies to wild canids, felids, ruminants, equids, fowls and wild boars. But the rest, such as bamboo rats, palm civets, or porcupines, lack standards for farming. No slaughter quarantine protocols are in place for any wildlife species. The lack of quarantine protocols poses uncontrollable public health risks. In response to COVID-19, the decision clarifies the requirement to meet quarantine standards for any uses of wildlife and draws a clearer line between legal and illegal uses.

Wildlife is not an indispensable part of the Chinese diet

A key concern is whether the ban will impact rural populations who depend on wildlife for subsistence protein intake and thus food security9, 10, 11, 12. Subsistence hunting for bushmeat is no longer taking place in China. Wildlife is consumed more as a delicacy to show status and hospitality25, as well as to pursue health benefits, which are not always scientifically proven. The demand for luxury food and supplements drives the price much higher than that of livestock. The price of muntjacs, palm civets and bamboo rats is about twice to five times the price of pork, and a much higher price applies for more threatened and rarer species. The shift of wildlife consumers from the poor to the upper-middle class is a serious concern. The strong demand from populations with increasing wealth and power indicates a market that may not be easily terminated, especially when large profit margins are involved (e.g. ivory and pangolin trade).

Curtailing demand through the ban

Another concern is that the ban might drive the wildlife trade underground and further increase the poaching pressure on wild populations, if the demand persists or even increases as China’s GDP grows11. It is true that reducing demand would be key. The effect of the ban depends on how demand is suppressed compared to the reduced supply. The price of wildlife will drop only when the demand is effectively suppressed by better law enforcement and continuous education, which could further reduce the quantity illegally traded (Figure 2B). Many wildlife consumers in China are driven by curiosity and not aware of the illegal conduct in this process. Now the ban, followed by amended laws, sends a clear signal to illegalize the consumption; together with the strong communications on the risk of zoonotic diseases, the demand for wildlife consumption by the general public has shown a sharp drop, as indicated in a survey26.

The attention span of the government and the public can be short. In May 2003, when Himalayan palm civets in Guangdong were found to carry SCoV-like viruses after the SARS outbreak27, the State Administration of Industry and Commerce and the State Forestry Bureau announced a temporary ban on wildlife hunting and trading. However, the List of 54 terrestrial species to be commercially traded, used and farmed, including palm civets was released after repeated appeals from wildlife farmers and provincial Forestry Bureaus, to which WHO showed concerns. Although the list was abolished in 2012, it actually lifted the restriction on farming and trading of species without special state protection. The lesson from SARS indicates that the promotion of policy change especially related to wildlife management is time-sensitive. Thus, the decision with an extended effective period beyond the pandemic signals a permanent change, which is unprecedented and encouraging.

A hard lesson learned

When the decision was announced by the People’s Congress, the wildlife farming and trading industry raised strong opposition. The livelihood of some rural populations engaged in wildlife farming is heavily impacted by the decision, although many of them did not have licenses. To minimize such an impact, both central and provincial governments offered financial aid to compensate farmers’ economic losses. For example, Guangxi and Jiangxi, two of the largest wildlife farming provinces, have paid 1.1 billion and 720 million CNY to compensate 20,000 and 2,344 farms, respectively (Supplemental Information). Farmers are encouraged to shift their livelihoods, but it is not so easy even with the compensation. A hard lesson learned from this turmoil is that, as farming wildlife was subsidized and encouraged for many years with insufficient management measures (i.e. quarantine), future guidance related to livelihoods and rural development should be more science-based and strictly abide by the laws and policies to avoid economic risks.

A long-term mechanism to sustain the efficacy of the ban

The purpose of the decision and ongoing law amendments is to curtail wildlife trade, especially to permanently ban food consumption of wildlife in China. However, to sustain the efficacy of the change, a long-term mechanism and efforts to reduce demand and improve management are needed.

A new paradigm for effective management

Sustainable use of wildlife is promoted through different international agendas including CITES and CBD (Convention on biological diversity). However, with the hard-hitting lesson of COVID-19, health risks should be considered throughout this process. Although food consumption has drawn most attention, emphasis should be shifted to the whole wildlife trade sector. In China, food consumption only accounts for about 24% of the output value of the wildlife farming industry28. The rest consists of fur, medicine, exhibition, pets and experiments, which are not banned. The health risks from direct contact with wildlife could arise at any stage of the supply chain of such trades. Effective trade regulation requires collaboration and management input from various institutions, which include departments overseeing food safety, animal health and public health, apart from the current wildlife management and conservation departments. It requires a holistic approach to manage wildlife trade, such as the One Health framework29, which was officially adopted as a wildlife management framework by CBD in 2014 to promote biodiversity conservation and human health30.

The decision has provoked rapid changes in the current system. The revised List of wildlife under special state protection was released for public comments in August 2020, for the first time after its release 30 years ago. The Catalogue of livestock and poultry genetic resources has been finalized in May 2020, which only allows 33 species to be farmed. The revision of the Animal Epidemic Prevention Law was released in September 2020 and the new Biosafety Law was issued in October 2020. The draft revision of Wildlife Protection Law was released for public suggestions in October 2020, which officially incorporated the decision into law and further restricted hunting, transportation and trade of other unprotected terrestrial species with an emphasis on public health. The improvement of the legal system could facilitate changes in institutional management and collaborations. Ministry of Ecology and Environment has announced that they will include illegal wildlife activities into their central environmental inspection program31, which is particularly effective in supervising environmental problems (e.g. pollution) as each reported problem will be included into the performance evaluation of responsible officials. This will strengthen the governance and law enforcement on wildlife protection as a whole.

Law amendments and future policies should internalize the externality of public health risks into the wildlife management. Strict quarantine standards for both wildlife and traditional domestic animals should be in place for any type of utilization. The traceable supply chain of wildlife should be required to differentiate legally sourced wildlife and their products from illegal ones. These requirements, together with reduction or cancelation of subsidies, can raise the bar of entering wildlife trade and phase out less competitive players.

Education campaigns to reduce demand

Wildlife conservation should be prioritized to serve as the safety buffer against spillovers of possible zoonosis diseases from wildlife to humans. The ultimate way to reduce the potential risk to human health is to reduce the demand for wildlife consumption32. Social norms and a more sustainable culture have been proven to be more effective than legal tools in many conservation interventions. As a recent survey showed, over 90% of the public are not interested in consuming wildlife and support a ban on consumption or all wildlife trade in China. It is especially noticeable that over 90% of wildlife consumers indicated a willingness to stop eating wildlife26. Although the survey was done via the internet and biased towards an urban and more educated population, it indicates a possible demand-side change with continuous education campaigns. For example, many restaurants, wet markets, shopping malls and other public venues have set up signs to warn of the health risks of wildlife consumption, raising the awareness of both consumers and suppliers. Though the effectiveness of this action needs to be monitored, it is the first time most Chinese receive continuous signals that eating wildlife can be illegal and threaten public health.

International collaboration and law enforcement to reduce spillover of demand

As spillover of demand to other countries has happened for timber, pangolins, ivory and others, we caution about similar consequences from this “ban”, especially for countries with weak regulations. As many of the consumed wildlife species are not listed in CITES, such as palm civets, or protected in other countries, such species might be increasingly traded to meet the domestic demand. The high demand may also drive more illegal wildlife trade domestically and internationally through online and physical markets. Before the demand drops to a reasonable level, international collaboration should be on the agenda to tackle associated risks. As China is holding the next COP meeting of CBD, we believe China will and should take the step forward to initiate stronger collaboration in this area.

China sends out a clear signal that wildlife conservation is a public safety issue, which could be a turning point for biodiversity conservation with stronger legal and social support. The political will of leaders of China sets a solid foundation for such a change. The ban on food consumption could be a starting point for a more effective trade management system including other uses of wildlife. As one of the major destinations of wildlife trade in the world, the emphasis on public health in China might cause ripple effects and promote similar paradigm shifts in other countries.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information containing species lists can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.036.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Cohen J. Mining coronavirus genomes for clues to the outbreak’s origins. Science. 2020;241:abb1256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam T.T.-Y., Shum M.H.-H., Zhu H.-C., Tong Y.-G., Ni X.-B., Liao Y.-S., Wei W., Cheung W.Y.-M., Li W.-J., Li L.-F., et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature. 2020;583:282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Balbin-Ramon G.J., Rabaan A.A., Sah R., Paniz-Mondolfi A., Pagliano P., Esposito S. History is repeating itself: Probable zoonotic spillover as the cause of the 2019 novel coronavirus epidemic. Infez. Med. 2020;28:3–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booth H. On COVID-19, and rebalancing our relationship with nature. Interdiscip. Cent. Conserv. Sci. 2020 https://www.iccs.org.uk/blog/covid-19-and-rebalancing-our-relationship-nature [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daszak P., das Neves C., Amuasi J., Hayman D., Kuiken T., Roche B., Zambrana-Torrelio C., Buss P., Dundarova H., Feferholtz Y., et al. 2020. Workshop Report on Biodiversity and Pandemics of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobson A.P., Pimm S.L., Hannah L., Kaufman L., Ahumada J.A., Ando A.W., Bernstein A., Busch J., Daszak P., Engelmann J., et al. Ecology and economics for pandemic prevention. Science. 2020;369:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China . 2020. The decision to thoroughly ban the illegal trading of wildlife and eliminate the consumption of wild animals to safeguard people’s lives and health. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brittain S. The covid-19 response and wild meat: a call for local context. Interdiscip. Cent. Conserv. Sci. 2020 https://www.iccs.org.uk/blog/covid-19-response-and-wild-meat-call-local-context [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynteris C., Fearnley L. 2020. Why shutting down Chinese “wet markets” could be a terrible mistake.https://theconversation.com/why-shutting-down-chinese-wet-markets-could-be-a-terrible-mistake-130625 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro J., Bingre P., Strubbe D., Reino L. Coronavirus: why a permanent ban on wildlife trade might not work in China. Nature. 2020;578:217. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sas-Rolfes M. ‘t, Hinsley A., Challender D., Verissimo D. 2020. Coronavirus: why a blanket ban on wildlife trade would not be the right response.https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/blog/coronavirus-why-a-blanket-ban-on-wildlife-trade-would-not-be-the-right-response/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooney R., Jepson P. The international wild bird trade: what’s wrong with blanket bans? Oryx. 2006;40:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivalan P., Delmas V., Angulo E., Bull L.S., Hall R.J., Courchamp F., Rosser A.M., Leader-Williams N. Can bans stimulate wildlife trade? Nature. 2007;447:529–530. doi: 10.1038/447529a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Challender D.W.S., MacMillan D.C. Poaching is more than an enforcement problem. Conserv. Lett. 2014;7:484–494. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tensen L. Under what circumstances can wildlife farming benefit species conservation? Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016;6:286–298. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Challender D.W., Hinsley A., Milner-Gulland E. Inadequacies in establishing CITES trade bans. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019;17:199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ege G., Schloenhardt A., Schwarzenegger C. Carl Grossmann Verlag; 2020. Wildlife Trafficking: The Illicit Trade in Wildlife, Animal Parts, and Derivatives. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stem C., Margoluis R., Salafsky N., Brown M. Monitoring and evaluation in conservation: a review of trends and approaches. Conserv. Biol. 2005;19:295–309. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conservation Center Shanshui. 2020. Wild animal protection list, a ruler with blurred numbers.http://www.shanshui.org/information/1906/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W., Yang L., Wronski T., Chen S., Hu Y., Huang S. Captive breeding of wildlife resources—China’s revised supply-side approach to conservation. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2019;43:425–435. doi: 10.1002/wsb.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi H., Parham J.F., Lau M., Chen T.-H. Farming endangered turtles to extinction in China. Conserv. Biol. 2007;21:5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00622_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham A.A., Turvey S.T., Zhou F., Meredith H.M.R., Guan W., Liu X., Sun C., Wang Z., Wu M. Development of the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) farming industry in Shaanxi Province, China: conservation threats and opportunities. Oryx. 2016;50:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Agriculture and Rural affairs of the People’s Republic of China . 2018. Central File No.1 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan J., Lu Y., Cao X., Cui H. Regulating wildlife conservation and food safety to prevent human exposure to novel virus. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020;6:1741325. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi X., Zhang X., Xiao L., Li B.V., Liu J., Yang F., Zhao X., Cheng C., Lü Z. Public perception of wildlife consumption and trade during the COVID-19 outbreak. Biodiv. Sci. 2020;28:630–643. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guan Y. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to the SARS coronavirus from animals in southern China. Science. 2003;302:276–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1087139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chinese Academy of Engineering . 2017. The strategic research report on the sustainable development of wildlife farming in China. [Google Scholar]

- 29.FAO. OIE. WHO, UN System Influenza Coordination, and UNICEF and WORLD BANK . 2008. Contributing to One World, One Health: a strategic framework for reducing risks of infectious diseases at the animal-human-ecosystems interface.http://www.fao.org/3/aj137e/aj137e00.htm [Google Scholar]

- 30.Convention on Biodiversity COP XII (CBD) 2014. Decision XII/21 Biodiversity and human health.https://www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/?m=cop-12 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu X. 2020. Wildlife conservation will be included into central environmental inspection program. The red line must not be crossed! Beijing Dly. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . World Health Organization and Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 2015. Connecting Global Priorities: Biodiversity and Human Health. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.